Volunteering for the Cause

While women patrons generally stood discreetly behind the scenes, Claire Raphael Reis (1888–1978), perhaps the single most indispensable woman to modernist musicians, was much more visible, as executive director first of the International Composers' Guild and later of the League of Composers. Her "luminous,

nourishing energy," as the writer Waldo Frank once characterized it, became legendary.[39]

Diverse ideologies converged to inspire Reis. Ironically, given modern music's small, elite audience, she approached her task with the tools and ideals of the settlement-house volunteer. If Gertrude Whitney embodied the high-society ambivalence of an Edith Wharton character, Claire Reis felt the social mission of a Jane Addams or Lillian Wald. A consummate organizer, she had deep roots in important feminized spheres—social service and the woman's club—and she embraced the goals of social feminism: to promote reform through vigorous action. While some of her female contemporaries labored for the rights of children, new immigrants, and the poor, Reis took on another of society's underdogs, the composer. Her activism and progressive roots closely paralleled those of Katherine Dreier, one of the founders and driving forces behind New York's Société Anonyme, an organization begun in 1920 to exhibit contemporary art.[40] Reis's career also reveals much about early musical modernism in New York—especially the years between 1910 and 1920, a decade that remains almost completely overlooked by music historians.

Like Blanche Walton, Claire Reis was a gifted pianist inhibited from becoming a professional by the conventions of her time and class. While Reis later claimed that her teachers had encouraged a concert career, "playing for charity was my mother's idea of bringing up a musical daughter."[41] And musical charity became her principal pursuit. But she also happened upon modernism while both she and it were young, especially through piano studies with Bertha Fiering Tapper at the New York Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School).[42] Tapper held Saturday-afternoon musicales at her home, and it was there that she presented Leo Ornstein, another of her students, whose career she helped promote. Reis later recalled bringing both the writer Waldo Frank and another of her good friends, the future critic Paul Rosenfeld, to hear Ornstein at one of Tapper's Saturday-afternoon concerts.[43] For all three, as well as for others, these musicales gave a valuable introduction to music that was just beginning to reach America. Frank vividly recounted one of Tapper's afternoons, which probably took place in 1914:

The long room [in Tapper's home on Riverside Drive] with a façade of windows giving on the Hudson was astir like a convention of birds with the elegant gentlemen and ladies perched on their camp stools. . . . [After Ornstein played some Debussy, Ravel, and Albéniz], Mrs. Tapper stood up and announced to her guests that Leo would now play some of his own music. Leo responded with a voluminous, cacophonous broadside of chords that seemed about to blow the instrument in the air and break the windows. Chaos spoke.[44]

For Reis, encountering Ornstein "was really the beginning, the ear opening, if not the eye opener for me."[45] In the spring of 1916, eight months after Tapper's death, Reis took up her teacher's mission, presenting Ornstein in a series of "Four Informal Recitals" at her home on Madison Avenue.[46] Those events were an important harbinger of developments in art music in the 1920s. The critic Paul

Fig. 26.

Bertha Fiering Tapper and students, ca. 1908. Mrs. Tapper is at the

center. To her left are Leo Ornstein and Claire Raphael. To her right

are Kay Swift and Pauline Mallet-Provost (who later married Ornstein).

Photograph in the collection of Vivian Perlis.

Rosenfeld had proposed the concerts in letters to Reis, and as he wrote, a portent of her future unfolded: "The point is, that in the back of my mind there is a desire to help organize a modern music club, . . . and I wonder whether an audience gotten together for Leo's recital couldn't help form a nucleus for such a society? There's really a crying need for such an organization to make headway against the sluggish conservatism in musical circles."[47] Although no such organization materialized immediately, Rosenfeld's letter shows that the idea for the International Composers' Guild and the League of Composers was germinating in the mid 1910s, long before either organization became a reality.

At the same time as Reis was aiding the career of a rising modernist, she was also helping the poor. In 1911, she had fulfilled her mother's vision of musical charity by establishing the People's Music League, an organization that presented some two hundred free concerts for newly arrived immigrants each year in New York schools.[48] It was an extension of the settlement house—of places such as Henry Street Settlement House in New York or Hull House in Chicago, where education and social services were provided for struggling newcomers to America. Reis later described it as her "first satisfying experience combining music and social service in a civic project. . . . [It] stirred great sympathy [for] people poor and hungry for music."[49] For the tenth anniversary of the People's Music League in 1922, Reis staged a concert of contemporary music, which included works of Rebecca Clarke, Louis Gruenberg, Frederick Jacobi, A. Walter Kramer, Lazare

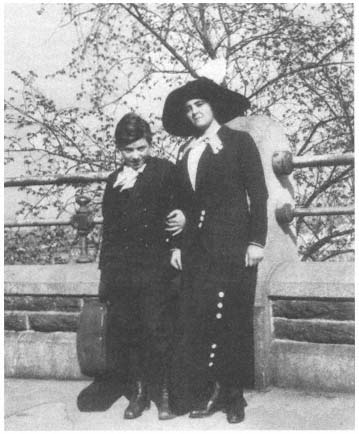

Fig. 27.

Claire Raphael Reis and the violinist Max Rosen, whom she

accompanied in New York during the early 1910s.

Photograph in the collection of Hilda Reis Bijur.

Saminsky, and Deems Taylor, almost all of whom would become major figures in the League of Composers.[50] For Reis, it was a pivotal event, as she later recalled, "My reputation with the Cooper Union Composers' concert led me into the next phase of music—this time with a feeling of service to composers . . . . My sympathy for the masses and for music seemed to begin a new chapter; sympathy for the composers ."[51]

That fall, after the People's Music League ended, Reis became executive director of the International Composers' Guild. It was a productive but unhappy appointment. She moved the concerts uptown to the Klaw Theater, which she obtained from a family friend at low rent; she put Alma Wertheim and the art dealer Stephan Bourgeois on the board; and she brought the guild out of debt. Yet. according to Louise Varèse, her husband felt Reis had "[taken] over" the guild, and

he disdained her after-concert receptions as "those delicatessen parties."[52] In giving her side of the story, Reis recalled "great disorder" at board meetings of the guild and puzzlement at the organization's pride in obscurity: "People like Ruggles would loudly voice their opinions. His was: If more than a dozen people [were] in [the] hall they were catering to the public."[53]

Yet Reis worked vigorously for the guild, even turning to journalism as a means of promoting it. In a 1923 article titled "Contemporary Music and 'the Man on the Street'" and published in the guild's unofficial journal, Eolian Review , Reis made an unusual suggestion: that the audience for new music might develop, not from the "so-called musically educated class," as she put it, but from those less acquainted with the European classics. She went on: "'The man on the street,' as signified by the average person without esthetic standards which belong to the past, this man can hear, can see, can sense an art belonging to his age because it is part of his life, because he has not been educated to accept definite laws based upon tradition ."[54]

This hope that the newest art would find an accepting audience with the most unsophisticated listener might seem naive, if not downright condescending. Yet it grew out of Reis's experience working with the poor, and its intent was genuine. She was applying social feminism to contemporary male composers. Not surprisingly, then, Reis's article was greeted with charges hurled at other social feminists of the day. Jerome Hart, a conservative freelance music critic, wrote that her theory gave evidence of the depths to which modernism had plunged: "Of course, this is but a phase of present-day unrest and revolutionism, which finds its extreme expression in Bolshevism, under which anarchists are elevated into prime ministers, incendiaries and criminals into judges, and all the rules of decent and orderly living are thrown into the discard. It is a passing phase, in which ugliness, both moral and physical, boldly asserts itself."[55]

Hart published this not long after the Red Scare of 1919–20, when the epithet "Bolshevist" had been hurled at many espousing new ideas. It hit social feminists especially hard. The pioneering Sheppard-Towner Maternity- and Infancy-Protection Act of 1921, for which women had campaigned vigorously, was dubbed "Bolshevist" by its opponents, and four years later such name-calling defeated a child-labor initiative in Congress. Hart, then, applied the language used against women as social reformers to Reis as a reformer in music. In viewing as subversive both the music she supported and the audience she anticipated, Hart also echoed contemporaneous indictments brought by his colleague Daniel Gregory Mason against modernism and jazz and foreshadowed the charges that composers, especially those involved in any way with folksong, would face decades later during the McCarthy hearings.

Another crucial element in Reis's background was her early membership in the Women's City Club of New York, which was begun in 1916 by a group of suffragists.[56] Just as her work for composers reflected social-feminist concerns, it likewise drew upon the organizing methods of the women's club. Women's music clubs (with

which Reis seems to have had no association) played a major role from the 1870s on in educating and elevating taste. But the women's club movement as a whole provided the principal means for women to become active outside the home.[57]

Reis's work in social service and the women's club thus prepared her for activism in new music. As leader of the group that seceded from the International Composers' Guild in 1923 to form the League of Composers, she became executive director of the new organization, which was also a successor in name as well as spirit to the People's Music League.[58] It became a major forum in New York for the presentation of both European and American new music, and unlike the guild, which disbanded in 1927, the league remains active today. Reis conceived the organization in a democratic spirit, similar to other leagues that were being founded in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Some, such as the National League of Women Voters and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, were the inspiration of women activists. Another, the League of Nations, had a broader base.

From the outset, Reis mobilized the composers' league. She organized its concerts, staged publicity campaigns, negotiated with conductors and performers, hosted social functions, raised money, provided office space in her home, and made her car and chauffeur available for league business. Directing the league became the equivalent of a full-time job—a job for which she was not paid but volunteered. Aaron Copland later characterized her as "a pro. Her day was as highly organized as that of any modern career woman," and his words provide an important clue to the context in which she should be viewed.[59] By no means a radical feminist, Reis belonged to a particular breed of "modern" woman. Proud to have marched with the suffragists—or so her daughter, Hilda Bijur, recalls—she embraced a feminist ideal that combined activism with a Victorian sense of womanly duty.[60] The historian Dorothy Brown has observed that social feminists campaigned for suffrage not to advance themselves but rather "to win the power to clean up America. Social feminism was serviceable and safe."[61] Reis later acknowledged her model to be one of social feminism's great architects, Jane Addams, who advocated combining home and family with public service. Addams also supported volunteerism for women, and Reis later articulated the same philosophy: "In those days if a girl did not need to earn money [she did not work]. Neither Jane Addams nor Lillian Wald—both very modern, liberal women—[did. They] were adamant that girls should not work for money."[62] To Reis and others of her generation, social service was modern, and volunteering provided an acceptable way of accomplishing it.

Also striking, in light of Reis's connection to women's clubs, was one of her methods for raising money. To finance the league's special staged productions, such as those of Igor Stravinsky's L'Histoire du soldat in 1928, his Les Noces in 1929, and Schoenberg's Die glückliche Hand in 1930, Reis formed an auxiliary board, probably modeled on a parallel appendage of the New York Philharmonic.[63] The league's auxiliary board seems to have been established in 1927 and had a slightly

fluctuating membership of around thirty-five, most of whom were women. Each gave a small gift of approximately $100 to $200 for individual stage presentations.

Yet while the auxiliary board made it possible for the league to produce these special events, most of which were American stage premieres, it also faced some scorn, both for the gender and social pretensions of its members. This was partly true because the auxilliary's contributions focused so singularly on splashy productions, many of which took place in the Metropolitan Opera House. But it also reflected a prevailing attitude about the network of "ladies" that supported America's cultural institutions. Louise Vàrese, for example, recalled somewhat disparagingly that Vàrese's New Symphony Orchestra had a "large Ladies' Committee" that did "whatever ladies' committees do."[64] The league's "ladies' committee" sponsored stage productions featuring major conductors such as Pierre Monteux, Leopold Stokowski, and Tullio Serafin. It chiefly funded performances of works by European modernists, however, not by young Americans. When Reis tried to persuade the auxiliary board to raise money for a composers' fund that would commission new American works, she found that its members' aesthetic boundaries were firmly set: "We were keenly disappointed when not a single response came from any of the hundred-odd 'pillars of art,' although they had gladly spent $250 for a box from which to see and be seen for one evening. . . . They seemed little aware of the composer as a fellow human being."[65]

Among Reis's many other achievements, a final item deserves attention: her publication in 1930 of American Composers of Today , the first catalogue of music by American modernists. Although today the compilation of bibliographies and work lists has become almost commonplace, in 1930, for these composers, such a source was unique. It served as an invaluable and highly practical means of giving conductors, performers, publishers, and critics a sense of existing contemporary literature, and it made access to these works possible. Two years later Reis produced a revision of the catalogue with two and a half times as many entries (expanding from 55 names to 135). Subsequent editions appeared in 1938 and 1947.[66]