Three—

Living with Music:

Isabella Stewart Gardner

Ralph P. Locke

"I know the key to your heart is music."

THE SWEDISH PAINTER ANDERS ZORN TO ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER

In 1860 the twenty-year old Isabella Stewart, daughter of a wealthy New York importer and iron manufacturer and his modest, genteel wife (herself daughter of tavern keepers), married John Lowell Gardner of Boston, heir to a fortune made in the East India trade. They soon established themselves in a splendid new townhouse in Boston's fashionable Back Bay; thus might have begun the career of a Proper Bostonian lady.

But Belle Gardner simply could not be held down. Over the next sixty-four years her playful extravagances, her romantic liaisons (real and purported), and her paradoxical fondness for both public display and intense privacy made her a living legend in Boston.[1] She was seen driving around the city in a carriage with two lion cubs,[2] she was painted in décolleté by John Singer Sargent against a sixteenth-century brocade that seemed to surround her head with halos, and she showed up at parties swathed in layers of gauze as an Egyptian "nautch girl," or wearing in her hair two large diamonds (12 and 27 carats), attached to bobbing gold antennas (fig. 5).[3] Although snubbed at first by the local gentry, in part for the sometimes scandalous cut of her clothes, in part simply for being from New York, she succeeded in making herself a figure of admiration and envy, capable of keeping the city in "a state of social excitement" (as the society magazine Town Topics put it).[4] Even today, the legend that was Isabella Stewart Gardner is alive, sustained by the renown of the astonishing art museum that she built as a home for herself and for her treasures after her husband's death in 1898 and that has been open to the public since soon after her own death in 1924. (She herself had opened it to the public on certain days, but the strain became too great, and in her last years she admitted only select individuals.)[5]

The Gardner Museum today speaks eloquently of its founder's passion for painting, yet she was also drawn to other, more ephemeral arts, such as theater, dance, and music. Unfortunately, musical and other performances that took place

This essay is part of my ongoing study of musical materials in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. A draft version of my catalogue of the museum's musical manuscripts, letters of musicians, signed photos, and the like has been deposited in the museum. I would like to thank the following for help and information of various kinds: Cyrilla Barr, Wilma Reid Cipolla, Mary Wallace Davidson, Dena P. Epstein, Philip Gossett, Anne Higonnet, Ellen Knight, Vivian Perlis, Sharon Saunders, the late Nicholas Slonimsky (who shared some enriching recollections of Gebhard and Loeffler), Ruth A. Solie, Rose R. Subotnik, Gretchen Wheelock, the staffs of the Harvard University libraries and the Library of Congress (notably Gillian B. Anderson, James W. Pruett, Wayne D. Shirley, and Robert Saladini), and numerous helpful staff members (present and past) of the Gardner Museum, especially Anne Hawley, Rollin van N. Hadley, Karen E. Haas, Patrick MacMahon, Susan Sinclair—and especially Paula Kozol, who got me started on it all.

All unpublished letters cited here, by Gardner (cited as ISG) and her correspondents, are in the Gardner Museum, unless otherwise stated; for the letters from Loeffler, I follow the numerical order in which they appear in the microfilms of the Archives of American Art. (Gardner's letters to Loeffler are in the Charles Martin Tornov Loeffler Collection, in the Music Division of the Library of Congress.) For most of the letters, especially when quoting specific words, I have consulted the original document or a microfilm version, although I have occasionally used typed transcriptions in the possession of the Gardner Museum. My own transcriptions preserve in nearly all cases the writer's punctuation (eccentric but expressive in Higginson's case) and spelling. Many musicians' letters to ISG are on rotating display in the museum's Yellow Room (where she herself displayed them all, in a crowded and overlapping fashion that maximized the number of famous signatures on view); also belonging to the Yellow Room are various of ISG's musical memorabilia (e.g., portraits of musicians by Sargent, composers' manuscripts, a Beethoven life mask, a cast of Loeffler's hand) and cabinet photos of renowned performers.

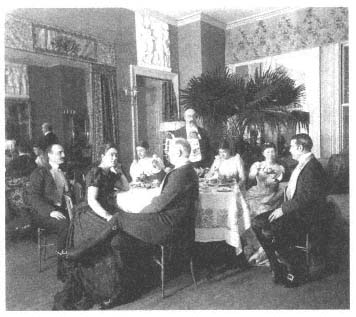

Fig. 5.

Dinner in the Music Room at 150–152 Beacon Street before the

Myopia Hunt Club Ball, 1891. Casts of friezes of angels making

music (from the workshop of Andrea della Robbia and based

on Andrea's tabernacle in the Duomo, Florence) can be glimpsed

above the doors (directly and in a mirror). Isabella looks into

the camera, two large diamonds glowing in her hair. Jack Gardner

stands. The other guests seem to be mostly or all unmarried: the

women are identified as "Miss" in the Museum's records. The full

roster includes (front of table, center) Alice Forbes Perkins,

Francis Peabody; (around the table, from left) Frank Seabury,

Augustus Gardner (not visible, behind Alice Perkins's head), Ellen

T. Bullard, John L. Gardner, Anna D. Anderson, Isabella Stewart

Gardner, R. M. Appleton. The Gardners' piano, draped, is visible

to the right. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Archives, Boston.

in well-to-do homes around the turn of the century were inadequately recorded in newspapers and music journals, precisely because they were not "commercial" in the usual sense—that is, not open to the public.[6] In the present case, however, much revelatory correspondence survives, at the Gardner Museum and occasionally elsewhere (and the correspondence with the Berensons, at least, is available in a recent, exemplary edition); when supplemented by information in Gardner's account books and other documents, and in two valuable but (in different ways) inadequate published biographies, these letters enable us to restore her love of instrumental music, song, and opera to the position it deserves in her biography, as well as to touch repeatedly on some issues of more general import: the process by which musical taste was formed around 1900, the problematic nature of private patronage in a democratic society, and the special role that wealthy women have

played in America's artistic life. Gardner's involvement in music, not surprisingly, proves to be typical for a woman of her class and means, yet also extraordinary. We must be careful not to underestimate the historical significance of the extraordinary. Gardner's case, precisely in its unique aspects, reminds us how much could, in America's era of merchant princes, be accomplished and be personally, sometimes idiosyncratically, shaped by an individual devoted to music and endowed with the financial means, energy, imagination, and stubborn selfishness that can put that devotion to work.

"The Key to Her Heart":

Music in a Life

The arts always held a proud place in the life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. As a girl and young woman in New York City, she was privately educated (attending the Miss Okill School) and acquired fair skill at sketching and watercolor. Her biographer Louise Hall Tharp informs us, although without documenting the claim, that young Isabella also learned to read music well. Presumably, this means "well" by nonmusician standards—that is, she may have been able to follow a score, more or less, and play simple pieces, or at least pick out melodies and chords, at the piano. (As a grown woman, Gardner rarely drew, however, and never played an instrument.) Clearly, her appreciation of the arts was keen and her exposure to first-rate practitioners extensive, both in New York—not least at her family's church, Grace Episcopal Cathedral (the English composer George Loder was the distinguished organist and music director)—and in France and Italy, where at seventeen she was taken by her parents for more than a year of travel and additional schooling. If, as Tharp concludes, this exposure only made the young Isabella Stewart feel unsatisfied with her own amateur accomplishments, she was not alone: upper-class American women in the later nineteenth century were generally growing impatient with the traditional female role of providing modest entertainment at the keyboard for family and guests.[7]

Whatever the motivation, Gardner's musical passion found its primary outlet in concertgoing. After settling in Boston, she faithfully attended the concerts of the Harvard Musical Association (an important predecessor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra); whenever she returned to New York for a visit, she took in great quantities of music and theater.[8] In addition, the Gardners' passion for world travel brought them into contact with some distinctive musical experiences, which Isabella vividly reported in letters and diaries. Thailand: a priest, overheard chanting by moonlight. Java: a court reception at which "a large orchestra [i.e., gamelan] in the shadow . . . played most strange music and with a strange fascination. The whole thing under one's breath, and as if something were going to happen." Egypt: a muezzin; dervishes dancing to a darabukka drum; music of shepherd pipes coming "to us from all the hillsides"; and—at an American Mission School—boys singing a familiar Protestant hymn in Arabic, which, Gardner noted, "startled and affected me." Venice: music in a Hungarian-style café, and a moonlight ride through the lagoon in Guillermo's "music boat" to the sounds of "a delightful ser-

enade" (as Jack described it to a friend). Vienna: waltzes conducted by Eduard Strauss in the Volksgarten. Berlin: the Joachim Quartet. Paris: Jules Massenet, who played his new opera La Navarraise to Isabella at the piano.[9]

By the 1880s Isabella and Jack had become pilgrims to the Wagner Festival at Bayreuth (they went together four times, and she went one other time without Jack), were spending every other summer in Venice, were hobnobbing with the rich and famous (e.g., Princess Metternich), and were beginning to collect paintings, rare books, and manuscripts, as well as signed photos of notable opera singers and other musicians.[10] Both at home and abroad, they were also attracting talented friends who were to remain faithful to them for life; among these were a number of major writers, artists, and scholars (Henry James, John Singer Sargent, Bernard Berenson), and musicians as well (including the composer-pianist Clayton Johns and Wilhelm Gericke, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra). In 1880 the Gardners acquired a house that adjoined their Beacon Street home and, by knocking down several walls, created a first-floor music room big enough for concerts by chamber ensembles or even a medium-sized orchestra, although the space was by no means as big or high-ceilinged as the Music Room in the future Fenway Court.[11]

How much Jack Gardner himself cared for music is a bit of a mystery. Tharp states that he was "well educated in music and sufficiently fond of it," but she claims repeatedly, and with a touch of ridicule, that he was less interested in music than his wife and that, in particular, he disliked Wagner. A careful examination of the evidence, though, reveals that Tharp has exaggerated the difference between the spouses in musical matters; in particular, Jack's supposed dislike of Wagner's music derives from Tharp's skewed reading of a single remark in a letter to Isabella from Gericke.[12]

But even allowing for errors and overstatements, Tharp's basic point remains perfectly plausible and even likely—namely, that Jack was less obsessively enamored of music and art than was La Donna Isabella (as friends called her). Indeed, one would be astonished had it been otherwise, given the extraordinary intensity of Gardner's artistic passions and the fact that the cultivation of the arts was at the time widely considered part of a society lady's domain and even responsibility, while her husband tended to business and financial matters.[13]

The more relevant question is not whether Jack always shared his wife's taste in music (or in paintings, poetry, or diamonds), but whether he encouraged, supported, and "indulged" his wife's tastes (as her first biographer, Morris Carter, who knew her well, put it).[14] The answer seems from the evidence to be an over-whelming "yes," even if, as has been suggested, he swallowed hard at some of her most extravagant purchases. His support, one suspects, derived in part from self-interest: the lavish parties, with splendid music, that Isabella organized surely helped confirm Jack's status among his peers, no less than did the $100,000 Titian (The Rape of Europa ) that hung in the drawing room of 152 Beacon Street.[15]

But Jack's support of her schemes and projects derived primarily from something deeper—namely, his devotion to her. He seems to have enjoyed the splash

and unpredictability—the sense of fun—that she brought into his predominantly practical and duty-bound life,[16] and he also seems to have understood her emotional needs. For one thing, her rejection by the Bostonian matrons during their first married years must have hurt Jack and certainly seems to have brought them closer together. Far worse, their adored child Jackie (John L. Gardner, Jr.) died in 1865 at the age of 20 months, and Isabella was subsequently informed that she could never again risk becoming pregnant.[17] Isabella plunged into a deep depression until Jack helped her find her bearings again by taking her to Europe (she was carried up the gangway on a mattress) for several revivifying months of touring, museums, and concerts in Scandinavia and Russia, Vienna, and Paris.[18]

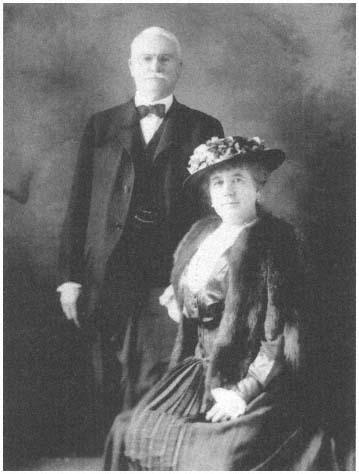

From that point on—and they had three decades more together—Jack seems rarely to have flinched at the expense of time, effort, or cash that Isabella poured into the arts, nor indeed objected to her welcoming various handsome young male artists and musicians into her entourage (see, e.g., fig. 6). Whatever limits were imposed on their collecting and other artistic activities seem to have come from a mutual awareness that their financial resources were substantially slimmer than, say, those of Andrew Carnegie or the Vanderbilts.[19] Henry Lee Higginson, the founder of the Boston Symphony and one of Jack's closest friends, summed the situation up fairly in a letter to Mrs. Gardner years after Jack's death: "You conceived nobly and have lived beyond your conception—of beauty and duty. Clearly it was your dream, and Jack helped you as he could [my emphasis]. To our country full of life and enterprise what dream could have accomplished more?"[20]

The constraints on the Gardners' collecting habits were lifted a good bit in 1891, when Mrs. Gardner's father died, leaving her $1,600,000.[21] Some of the major works in the Gardner Museum were purchased in the next few years, including, significantly, a scene of domestic music-making: Vermeer's The Concert . During the mid 1890s, the Gardners also developed the idea of building a spacious new house-cum -museum. When Jack died in December 1898, Isabella—although 58 years old—carried out the plan, thanks in part to Jack's estate of $2,300,000 (his will trustingly permitted her to tap the principal).[22] She did her part as well, instituting economies in such areas as food and servants, even bragging at times about having to darn her own stockings.[23]

"Fenway Court," as she called the new structure, is a four-story palazzo (address: 2 Palace Road) but turned outside-in, as befits a northern climate: the outer walls have few windows; instead, carved stone balconies from a mansion in Venice, where they faced outward to the canals, open onto a central courtyard that was and still is filled with flowering plants year-round (fig. 7), thanks to a protective glass roof. The building was unveiled on New Year's Day 1903, in a memorable evening that included a concert—in the large "Music Room"—by fifty members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Gericke.

In the years that followed, Fenway Court, like Isabella's previous home, served as a meeting place for local musicians and a stopping point for visiting Europeans (e.g., Pablo Casals, Ferruccio Busoni, Vincent d'Indy).[24] Gardner had now become

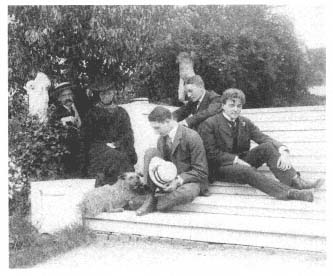

Fig. 6.

In the gardens at "Green Hill," the Gardners' country home in

Brookline, Massachusetts, June 1903. From left: Richard Fisher,

Isabella Stewart Gardner, two unidentified young men,

and the tousle-headed pianist (and future New England

Conservatory professor) George Proctor. Isabella Stewart

Gardner Museum Archives, Boston.

a tantalizing, often veiled eminence (fig. 8). She opened the galleries and Music Room on selected occasions, including by-invitation-only social events and fundraising performances for charities but also a small number of serious concerts open to the general public; these latter included two full seasons of Kneisel Quartet concerts, 1908–10 (including the premiere of Arthur Foote's Second Piano Trio, Op. 65, with the composer at the keyboard), several seasons of concerts arranged by Julia Terry, a 1908 Walter Damrosch lecture on Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande (coordinated with the performances at the Boston Opera Company under André Caplet), and an early performance (by the Flonzaley Quartet) of the Schoenberg String Quartet No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 7.[25]

By 1914 Gardner, aged seventy-four, was losing interest in mammoth social gatherings and feeling the need for ever more wall space to display paintings and tapestries. The Music Room was therefore split horizontally to create new and separate upstairs and downstairs areas.[26] Solo recitals and chamber music thenceforth took place in the newly created second-floor Tapestry Room. (The tradition continues: recitals are given twice a week in the Gardner Museum today, in the same room.) Beginning in late 1919, when Gardner was partially paralyzed by a stroke, she particularly appreciated the musical ministrations of the violinist Charles Martin Loeffler, the pianist Heinrich Gebhard, and others (see Vignette D), and the piano recitals by students of her former "musical protégé" (as she her-

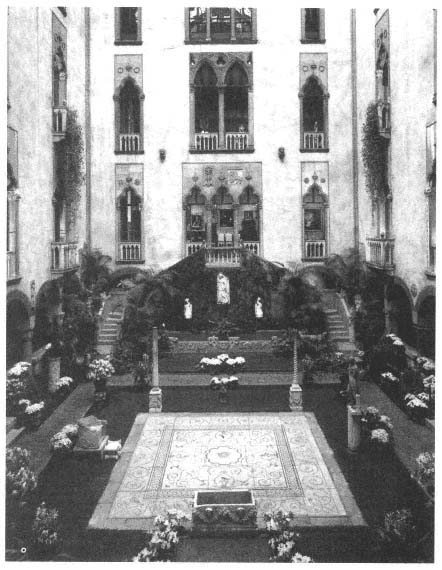

Fig. 7.

The glass-roofed courtyard at Fenway Court (built 1899–1902), including at

rear the stairs from which Dame Nellie Melba sang.

Photograph by Greg Heins, 1981; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Archives, Boston.

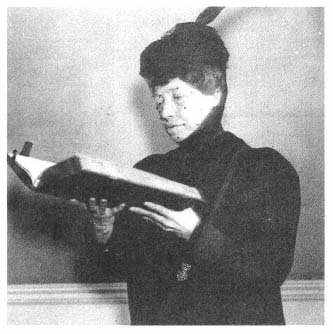

Fig. 8.

Isabella Stewart Gardner, lover of things old and rare, in 1907.

Photograph by O. Rosenheim, London, taken at the home

of Henry Yates Thompson; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Archives, Boston.

self once put it), the New England Conservatory professor George Proctor.[27] At eighty-two, two years before her death, the bedridden Gardner reported to a correspondent: "I think my mind is all right and I live on it. . . . I really lead an interesting life. I have music, and both young and old friends. The appropriately old are too old—they seem to have given up the world. Not so I, and I even shove some of the young ones rather close."[28]

Music at Home

Of the three major aspects of Gardner's musical activities to be discussed here—music at home, patronage of individual musicians, and sponsorship of Boston's musical institutions—the most basic was the first. She believed deeply that for art and music to thrive, they must be integrated into the fabric of daily existence. This conviction led her to incorporate things of beauty into her own surroundings, at times mixing—in a single room—paintings, drawings, tapestries, religious vestments, and other decorative objects, and often juxtaposing items from different periods and countries.[29] Music, similarly, added beauty to life. When the courtside windows were open, the sounds of music (Gregorian chant, for example) could

float in and out of the various spaces, enhancing the mood of a social occasion—especially at night, as visitors strolled through galleries lighted by fireplaces, candles, Chinese lanterns.[30]

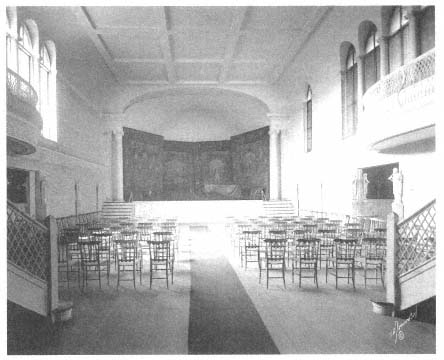

Gardner also knew how to do the reverse: to place decor and mood at the service of music. This is seen particularly in the frequent formal concerts and recitals that she held in her great Music Room in Fenway Court. The Boston music critic William Foster Apthorp wrote nostalgically to Gardner in 1908 while on a trip in far-off Egypt: "I hear little birds every now and then sing of Fenway Court and its wonders. . . . Your music-room is the one place of the sort where you are not reminded of 'music in the parlour' (which I abominate) nor of a 'concert' (which I enjoy merely professionally). You ought to give a course of lectures . . . on Artistic Atmosphere."[31] Apthorp particularly appreciated the Music Room's white plaster walls, bare wood floors, and simple straw-bottomed chairs (fig. 9), writing, in a concert review, that he knew of "nothing at once more inspiring and more restful. It encourages music without interfering with it."[32] Moreover, the hall had splendid acoustics, as Busoni and other visitors were astonished to discover.[33] The alert among them may also have noticed, after leaving the Music Room to wander through the galleries, that certain of the art works continued the musical theme in one or another way, such as Vermeer's The Concert , Gerard Terborch's A Lesson on the Lute , and pieces by Whistler entitled Harmony, Nocturne , and even Symphony in White .[34]

Both during her married years and afterward, Gardner must have prided herself on maintaining high aesthetic standards in her music, just as she did in the various paintings that lined her walls, and her friends must have known it. In 1892, when she was in Venice, her young admirer Thomas Russell Sullivan felt free to write mockingly to her of Boston's social life, clearly aware that she would share his disdain for people who gave "band-concerts and things on their lawns in the moonlight."[35] Gardner's way of breaking with this kind of mundane atmosphere—in which music often served as an innocuous, conventional background hum to the real business of eating, drinking, and socializing—was to insist on presenting first-rate music, some of it fairly unusual. Indeed, the very fact that she often held formal concerts, with printed tickets for her guests and with no refreshments until after the music, already set her apart from most hostesses of her day.[36]

Gardner, although unusual, was not unique in maintaining high musical standards in her home. In his memoirs, Clayton Johns mentions hearing visiting artists such as Paderewski, Pol Plançon, Lilli Lehmann, and Melba, either in formal or impromptu performance, at the homes of Mr. and Mrs. Dixey and of Mr. and Mrs. J. Montgomery Sears; the Searses had a music room that, like the Gardners', could and at times did present the Boston Symphony Orchestra to a substantial audience.[37] The noted pianist Heinrich Gebhard later recalled playing recitals, some solo, some with Loeffler or other musicians, at various homes: particularly notable are, at Fanny Mason's house, a performance of some songs of Loeffler's with the visiting soprano Maggie Teyte (renowned as Mélisande in Debussy's opera), and, at the home of the wealthy poet Amy Lowell, some highly gratifying,

Fig. 9.

The Music Room at Fenway Court (eventually demolished in 1914–15).

Photograph, ca. 1910, by Thomas E. Marr and Son; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Archives, Boston.

rather Bloomsburyesque evenings in which a hand-chosen seven or eight guests, including Gebhard, partook of a "luscious" dinner, engaged in "intense conversation" about modern poetry ("I said very little but listened enthralled"), and at ten moved to the music room for Gebhard's performances, which (at Lowell's insistence) were interspersed with long pauses for silent reflection or pensive discussion of the piece just played.[38] Nevertheless, these serious recitals were surely the exception to the rule, which might be better represented by another affair at Fanny Mason's: there was not enough space for all the guests in the music room, a fact that allowed a good deal of talking to go on just outside the door. (Such chatter was, Paderewski reports, a standard, "humiliating" feature in concerts at private homes nearly everywhere he traveled.)[39] Loeffler—a guest in this case—reported the scene to Gardner, knowing that she would share his sentiments: "I will say this of the French singer Mme Goucher and her to me unknown pianist, that neither drowned our conversation in the other rooms!"[40] This may seem disrespectful, coming from a musician who surely appreciated that Gardner, like Amy Lowell, insisted on a decorous silence.[41] But the remark also suggests that the two per-

formers in question were not very captivating; Gardner, in contrast, always made sure that the music was worthy of her guests' attention.

In one respect, at least, the mystery-loving Mrs. Gardner probably went further than Lowell or any other concert-giving hostess in Boston or perhaps anywhere: she refused to reveal in advance who the performers would be, no matter how starry their names. The printed invitations for the opening of Fenway Court did not mention that there would be music at all, never mind that it would consist of a concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In March 1905 the surprise entertainment was the great Australian soprano Nellie Melba, who not only sang "a long programme . . . in superb voice" (as Elise Fay wrote to Loeffler, who was sojourning in Europe), but—after dinner, as the guests wandered through the candlelit galleries—sang again from the landing above the courtyard fountain.[42]

The invitations to the first of two Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts chez Gardner in 1888–89 did include the understated word "Music" but gave no further details. This was the concert that, Carter reports, "ended the outward hostility of society to Mrs. Gardner; thereafter it seemed unwise to decline her invitations—it was impossible to foresee what one might be missing."[43] Mrs. Gardner's own behavior at such events must have added a further thrill of anticipation: one never knew whether on a given occasion she would stand modestly at the entrance handing out the printed programs[44] or, as at the Boston Symphony concert that inaugurated Fenway Court in 1903, station herself commandingly on the balcony in the Music Room, at the top of the twin curved staircases, thereby forcing Boston's most distinguished gentlefolk to huff and puff their way up one set of stairs to greet her and then down the other to take their seats.[45]

The program of that night's concert included works from the three categories most often represented in concerts at her various homes: established "classics" from the eighteenth century (in this case a Bach chorale, unspecified, sung by a small chorus, and Mozart's Overture to The Magic Flute ), early-or mid-nineteenth-century German works (Schumann's Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52), and products of the newer French school (Ernest Chausson's symphonic poem Viviane ).[46] Perhaps for lack of rehearsal time, the concert did not feature any music by young composers such as Gardner liked to encourage. She soon made up for that lack with an elaborate chamber and choral concert dedicated solely to the music of Loeffler, including the world premiere of A Pagan Poem , in a version for two pianos and three trumpets (the latter located out of sight, for dramatic effect).[47]

Mrs. Gardner's taste for modern French music—in which category one might reasonably include the Paris-trained and deeply French-influenced Loeffler—was somewhat advanced for its time, even in Boston, an early center of interest in modern French music.[48] (The repertoire lists for the nation's orchestras around the turn of the century were dominated to a striking degree by music of the Austro-German masters, from Haydn to Brahms and Wagner.)

The all-Loeffler concert is also notable for its mixing of works requiring quite different performing forces: a lengthy piece (as mentioned) for two pianos and

three offstage trumpets, some songs for soprano with piano accompaniment, and a work for women's chorus, solo soprano, viola d'amore obbligato, and piano. Such diversity, impractical in normal concert life, must have felt quite natural in Fenway Court. Gardner's love of juxtapositions may also be seen in the program of a concert given at her country home, "Green Hill," on 10 May 1900 by Loeffler, Proctor (playing piano but also harpsichord, an early instance of this instrument's revival), the Boston Symphony Orchestra cellist Alex Blaess, and the soprano Julia Heinrich:

Rameau. Trios for harpsichord, violin & cello.

Loeffler. Four songs with piano to French texts by Gustave Kahn.

C. P. E. Bach. Solfeggietto, for harpsichord.

Mattheson. Sarabande [presumably for harpsichord].

Martini. [The song] "Plaisir d'amour," arranged for viola d'amore, with harpsichord.

The hostess added further elegance and variety—and perhaps stimulated thoughts about the relationship between traditional Oriental art and recent French trends in art, literature, and music (the latter two represented by the ripely Symbolist and Fauréan Loeffler songs)—by writing the programs out in her characteristically large and assertive handwriting on a number of original Japanese prints; six of these still survive in the Gardner Museum.[49] Mary and Bernard Berenson were appreciative guests at this or another such parties, for Mary wrote from Florence in 1904, "I wonder if you ever have any more of that old, old music that delighted us so at your Tea."[50] Gardner probably made a point of inviting the Berensons—or perhaps cooked up this early-music tea for the Berensons and a few others—because she knew that he, in particular, was fascinated with the possibility of hearing the music of an earlier age whose visual art he knew well.[51]

Many of the performers who played for Gardner and her guests at Fenway Court or occasionally elsewhere were major artists, such as the fabled flamenco dancer Carmencita (in 1890, accompanied by two guitars), Busoni (in 1894—two recitals, one with Loeffler), and the great opera singers Jean and Édouard de Reszke (apparently in late 1891 or 1892).[52] In 1892 Paderewski was being run ragged by a grueling series of public appearances throughout the country at fees of $200–300, far lower than he deserved; he was also getting fed up with being put on display in private homes as a "stunt . . . by ladies in search of celebrities."[53] Perhaps aware of both factors, Gardner paid him $1,000 to perform a meaty program for herself and her husband alone (Beethoven's "Appassionata," Chopin's "Funeral March" Sonata, Schumann Fantasy, plus short pieces). She did, however, hide Clayton Johns behind some tapestries, Polonius-style; after the music, Johns revealed himself and dined with the pianist and the Gardners. Paderewski also agreed to perform a recital, again at the Gardners' expense, in Bumstead Hall in the Music Hall building; Isabella Gardner "sent all the tickets to the musicians of Boston."[54]

Of the musicians who performed at one or another of the Gardners' residences, most were not as well known as Paderewski, but most were likewise highly regarded in professional circles—almost musician's musicians (the archetype perhaps being Loeffler, who was also a personal favorite of Higginson's). A complete list of the performances that they and others gave chez Gardner would probably be impossible to reconstruct: music making seems often to have arisen spontaneously and in more or less private circumstances; indeed, certain of the recitals discussed thus far—even some of the more formal ones, before substantial audiences—are known to us only from a single offhand reference in a letter or memoir. A few further examples, though, will suggest the extent and variety of musical events in Gardner's homes:

1. Clayton Johns gave talks about the music of the upcoming Boston Symphony concerts in the Beacon Street music room (and, in rotation, in other Boston homes), illustrating his points with examples arranged for piano four-hands (the fifteen-year-old George Proctor assisting).[55]

2. A "burlesque orchestra" (presumably in the sense of a "toy symphony") featuring prominent string players from the Boston Symphony playing such instruments as the ocarina (concertmaster Franz Kneisel), autoharp (Loeffler), and trumpet (Timoteusz Adamowski) performed at Isabella Gardner's birthday party in 1898.[56]

3. During Gardner's several months of seclusion after her husband's death, the mezzo-soprano Lena Little arranged for the newly organized Brahms Quartet—apparently an all-female group—to play to her at 152 Beacon Street—with no guests.[57]

4. That summer, Tharp notes, Gardner's house guests in Venice included Little and the young pianist Proctor; "she wrote her friends in Venice that she would give no parties but that they must just come in to hear Miss Little sing."[58]

5. Two years earlier, also in Venice, Gardner rented a largish barca and had a piano put on it so that her house guests Clayton Johns and the British baritone Theodore Byard could perform upon the water (the Gardners' palazzo fronted on the Grand Canal).[59]

6. In 1904, Gardner gave a Christmas dinner for various, as she put it, "waifs and strays" (presumably including herself in that category) at Fenway Court, which ended with music by two of the guests, George Proctor and Lena Little. She drew a diagram of the seating plan in a letter to the Berensons and added: "Principally Art Museum with the two musicians. I had put magnificent little gifts on their plates, and made a rule that all conversation was to be general. So we really talked. Then we had music; Beethoven, Bach, Scarlatti, Chopin, Miss Little sang [Schubert's] 'Who is Sylvia' [based on a song from Shakespeare's Cymbeline ]. Then we made procession and

wandered through the house, the moon pouring down into the court. I think everyone was pleased. If you two had only been here."[60]

Certain of these lesser-than-Paderewski musicians were probably favored by Gardner for their personal graces as well as for their artistry. Adamowski was an outstanding Boston Symphony violinist (frequent soloist with the orchestra and leader of the respected Adamowski Quartet) but also someone who knew how to oil his way with the wealthy: a gossip columnist called him "society's favorite musician" and told of his throwing "a silver smile" from his seat in the orchestra's first violin section "to the happy place where Mrs. Jack Gardner sat."[61] Indeed, a number of musicians were at various times guests plain and simple: George Proctor stayed for a weekend at the Gardners' summer place in Beverly after returning from Vienna; Foote composed his Piano Quartet, Op. 23, and symphonic prologue Francesca da Rimini there during the summers of 1890 and 1891; in 1898, Gericke and his new wife Paula were the season's first visitors at "Green Hill," the Gardners' country home and farm in Brookline; and several musicians (including Little, Proctor, and Melba) were among those privileged to view Fenway Court in 1902, a year before it was officially opened to Boston society.[62]

Related to this emphasis on sociability, and particularly noticeable during the years of the Gardners' marriage, is a fondness for music a shade or two less weighty than the pieces performed on the 1903 Fenway Court concert, although still no lighter than what tended to be performed on the second half of many regular symphony concerts. When Gericke conducted members of the Boston Symphony in two concerts at the Gardners' Beacon Street home in November 1888 and March 1889, the programs included, among other things, Wagner's Siegfried Idyll , three movements apiece from Mozart's "Haffner" Serenade and Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, a Romanze for violin and orchestra by Gericke himself, plus a number of brief orchestral dances, scherzi, and character pieces by Bach (the Pastorale from the Christmas Oratorio), Gluck, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Wagner (the Meistersinger act 3 Prelude and Dances), the Viennese conductor Johann Herbeck, and Brahms (on one program, the Waltzes Op. 39, orchestrated for the occasion by Gericke; on the other, some of the Hungarian Dances).[63] Two of Gardner's closest musical friends during the 1880s and 1890s were composers of rather lightweight, though finely crafted, salon songs: Clayton Johns and the Venetian Pier Adolfo Tirindelli.[64] Gardner occasionally showed enthusiasm for musical numbers of simple, touching quality, such as Martini's song "Plaisir d'amour" or Percy Grainger's arrangement of the "Londonderry Air" (the tune soon to become renowned as "Danny Boy").[65]

Clearly her taste in music, as in everything, was eclectic, and free of simple snobbishness. Gardner was even attracted to certain aspects of popular or "low-brow" culture—boxing matches, magic shows, Red Sox games—and so enjoyed what Carter calls the "honest, red-blooded vulgarity" of the African-American

performer-songwriters Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson. "Mrs. Gardner admired not only their sincerity, but particularly the way they put their feet down. She went many times to see them and recommended [their 1909–10 show] 'The Red Moon' to all of her friends whom she considered up to it." She could even enjoy what Carter calls "such hearty, robust humor as May Irwin's"—referring to the famous white performer of "coon songs" in supposed African-American dialect.[66] But she never went so far as to invite these performers to play at her home.

And, whether outside her home or in it, she could not abide what we might call polite, sentimental "middlebrow" entertainment.[67] In a letter to Loeffler, Gardner snorted at the latest operetta ("What can it mean when people prefer [Oscar Straus's] The Chocolate Soldier [and do not support real opera]?"). Similarly, a letter from Arthur Foote to her indicates that she generally disliked the pretentious, often mawkish songs—the composer in question is the British-born hack who worked under the pseudonym Anton Strelezki—that passed for high art in many American and European drawing rooms.[68]

Patron in a Modern Age

The high quality of the musical works performed in Gardner's home extended as well to the playing and singing, as one may infer from the names (some already mentioned) of the performers of whom she was a patron. But what do we mean by "patronage"? Some of the musicians, we know, were paid directly for their services; for example, the men in the Boston Symphony each received $10 for the 1889 concert (including one rehearsal).[69] It would seem more accurate to say that in such a case Mrs. Gardner was for a few hours the players' "employer." The $1,000 Paderewski recital falls in a middle category between employment and patronage. Clearest are the cases of those musicians whom Mrs. Gardner knew well and who played at her request for her guests.

Patronage relationships, at least in modern times, risk becoming awkward and even volatile. The chief problem—how to reward musicians for services without seeming thereby to reduce them to servant status—was handled by Gardner in a variety of ways. The checkbooks of 1890–96 show that Loeffler and Johns were paid $75 apiece for each of several recitals of sonatas for violin and piano that they gave at Beacon Street to a select audience of about twenty-five;[70] Lena Little and Johns received $244 each for a concert (substantially more, although it is hard to know why).[71] In contrast, when Loeffler played to Gardner and a single guest (John Singer Sargent), the musician graciously but firmly declined—"as an hommage [sic ] to you and Mr. Sargent"—to accept the remuneration she offered.[72] And in later years, especially between Gardner's stroke in 1919 and her death in 1924, Loeffler and the pianist Gebhard repeatedly came—out of pure friendship—to play music to her alone (several of Loeffler's letters offer her Bach, Mozart, Brahms, Franck, Fauré, and d'Indy); by then, she surely knew they would be insulted by any offer of payment.[73]

Gardner nonetheless found appropriate ways of expressing her thanks to her

closest musician friends. She lent her Stradivarius to Adamowski and, later, to Loeffler.[74] In earlier years she and Jack paid the full expenses for a piano recital in Copley Hall by Gebhard; this included hiring sixty-five members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra so that he could play the Schumann Concerto.[75] And the Gardners supported a young pianist, the aforementioned George Proctor, during several years of study in Vienna with the great Theodor Leschetizky.[76]

Musicians, in turn, often did favors for the lady, beyond performing. Some gave her manuscripts and letters of famous composers (as did some friends who were not musicians). Some dedicated one or more works to her, as Busoni did to express appreciation for a $1,000 "loan."[77] And some took her, when in Europe, to visit renowned figures such as Cosima Wagner and (at the resort town of Ischl) Leschetizky, Johannes Brahms, and Johann Strauss, Jr.[78]

In such encounters, the question of who was doing a favor for whom seems to dissolve into something more complex, with both Gardner and her musician friend (e.g., Gericke, who instigated the visit to Brahms, and who interpreted) considering themselves the lucky beneficiaries. Clayton Johns, whom Gericke also brought along, captured in his memoirs the voyeuristic mood of the visit: "I don't remember what anybody said, but we saw Brahms in his little roadside house, the simplest little house you ever saw, and that was the main thing."[79] A similar complex of motivations and interests may have been at work in Loeffler's attempts to arrange for important European musicians (d'Indy, Cortot, Ysaÿe) to tour Fenway Court when concert tours brought them to Boston.[80]

But favor usually traveled a simpler course than this—namely, from the lady to the musicians, and, in Mrs. Gardner's imaginative hands, it could take a wide range of forms particularly suited to the individuals in question. Certain composers, for example, got that most precious of things: "the opportunity to be heard and appreciated by an intelligent audience" (as the composer Clara Kathleen Rogers put it).[81] In Fenway Court, Gardner opened her big Music Room, and her purse, for the all-Loeffler concert mentioned previously, for the 1907 premiere of the final version (for one piano, with orchestra—the Boston Symphony, of course) of Loeffler's Pagan Poem , and, in 1906, for a performance of a one-act opera by Amherst Webber, an English-born pianist and vocal coach (accompanist to Jean de Reszke).[82] She acted as an unpaid agent for Loeffler's music, offering it to publishers in France and the United States,[83] and she penned an article for the London Times in support of an opera by Tirindelli that, she had learned, would not otherwise be reviewed.[84] Even more characteristically, she encouraged and welcomed the interaction of artists in different areas, urging Loeffler to sit for a portrait by the painter Denis Bunker (Bunker died too soon, but Sargent's Loeffler is one of the glories of the Gardner Museum) and securing for Loeffler the right to make a musical setting of the poetic drama The White Fox by her friend (and a noted authority on Japanese art) Okakura Kakuzo, although Loeffler never brought the project to completion. Loeffler, in turn, encouraged her interest in Verlaine, the Goncourt brothers, and Jules Laforgue; indeed, the fact that Loeffler

and Tirindelli both set two of the same Verlaine texts and that all four songs are preserved in manuscript in the museum (along with other songs on French texts by the two) suggests a definite connection to one woman's literary preferences.

Money and expensive gifts were clearly not Gardner's preferred way of expressing appreciation and admiration. Nonetheless, toward the end of her life, she did distribute some of her wealth and possessions to musician friends in a fairly direct manner. As thank-you notes attest, she gave Melba her much-prized yellow diamond, Gebhard her Érard piano, the composer Margaret Ruthven Lang her harpsichord (in remembrance of Lang's father, the noted organist and conductor B.J. Lang), and Clayton Johns $10,000—an even more astonishing sum then than now.[85]

Gardner's generosity and supportiveness were apparently enough for Busoni, Johns, Little, Proctor, and most of the others. But Loeffler, a more sensitive, indeed prickly individual, seems to have wanted something more from her: respect and acceptance. True, from early on they enjoyed each other's company, shared interests musical and literary, and exchanged items that they knew the other would appreciate: for example, he gave her two books by Verlaine—in 1898 and 1919, each time with a Verlaine autograph "stuck in"—as well as a copy of Moby Dick and two major treatises by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson,[86] and she, only months after purchasing her Stradivarius violin in 1894, lent it to him for performances of his big Divertimento for violin and orchestra with the Boston Symphony. He also solicited her interest in his works, arranging for her to hear them in advance or discussing their literary sources with her.[87] Nonetheless, for many years Loeffler seems not to have been entirely sure how Gardner felt toward him. Even after she gave him the Strad on indefinite loan in 1898, and after he had dedicated the Divertimento to her,[88] something prevented him from being completely at ease with her (to the extent that he could ever be at ease with anyone: he was engaged to Elise Fay for twenty-four years before agreeing to marry her). Certainly, it rankled that, as he put it in a letter to Gardner, "I know you often wish me different on many points." Around 1904 he began to express resentment about playing for her guests, some of whom, he claimed, had been rude about his playing and his compositions ("I also have feelings!"). He even offered to return the Strad; his use of it presumably made him feel beholden to her, or feel obligated to play when he might prefer not to. When she told him in 1918 that he could keep the instrument forever as a gift, he felt that the air had now been cleared between them and expressed his relief in a heartfelt letter: "One of the pleasures in playing the beautiful Stradivarius was, that it belonged to you and that you intrusted [sic ] it to me. . . . I hardly know now, how to express to you how deeply I am moved." From that point on, their mutual affection flowed undisturbed, she thanking him for being "so constantly kind," he calling her "one of the best friends that ever was."[89]

Loeffler was, by all accounts, a rare and unclassifiable creature: witty and melancholy (by turns, or at the same time), conservative and experimental, European and American, adoring Gregorian chant, Bach, and Fauré but also Duke

Ellington's trumpeters and Broadway shows.[90] There were plenty of reasons why Gardner should have been particularly attracted to him and intrigued by his compositional work. Still, one wonders whether certain other prominent Boston composers—John Knowles Paine, Amy Beach, George Whitefield Chadwick, the young Daniel Gregory Mason—received at least a moderated version of Gardner's special nod, and if not, why not. Perhaps the documents in question simply do not survive (Gardner destroyed part of her archive in her last years).[91] But we must also remember that Gardner had strong likes and dislikes, both in the music she wished to hear and in the kind of people she wished to have around her, and that, in any case, she felt no obligation to support every creative artist in Boston; such are, after all, the privileges (and arguably one of the strengths) of private patronage. She identified proudly, it is true, with Boston and its cultural institutions, but she remained first and foremost a cosmopolitan servant of Art and a defender of absolute aesthetic standards, to be determined by herself. Her motto she inscribed on the front of the Gardner Museum: "C'est mon plaisir."[92]

In the case of Beach, we may also wonder whether Gardner was particularly uncomfortable with the idea of a woman composer or, more generally, a woman "creator." That she purchased no work by women painters proves little, for neither did most other collectors and museum curators. But it does seem relevant that she preferred to surround herself with men—not women—of accomplishment, or else, as the composer Clara Kathleen Rogers put it later, "admiring youths—eager and proud to hold her wrap." (These well-turned young men functioned, it has often been suggested, as surrogate sons, but a flirtatious narcissism was clearly also involved.)[93]

To the extent that she let herself become close to women from outside her family and social set, a few were serious writers and none were composers or painters. (Melba and Lena Little were performing musicians and thus, according to the prevailing ideology, not true creators.) Admittedly, two women composers—Rogers and Lang—had some of their works performed at 152 Beacon Street,[94] but Gardner may have had no say in choosing the selections (the concerts, entirely of music by living Americans—some male, some female were organized by the Manuscript Club), and in any case she seems not to have become particular friendly with either woman. (Rogers recalls in her memoirs that she "never felt drawn to [Gardner]," although also that she defended Gardner against the accusations of the self-righteous.)[95] Gardner did display a signed photograph of Ethel Smyth in the Yellow Room of Fenway Court, but there is no evidence that she pursued a friendship with the British composer or took a special interest in her music. In contrast, Gardner did become close to several wives (or future wives) of men involved in the arts, including Mary Berenson, Corinna Putnam Smith, and Elise Fay Loeffler.[96]

Perhaps the problem was that certain creative women regarded Gardner as inadequate or unaccomplished.[97] Despite her skill at making herself the center of attention, she, as it may have appeared to them, had little concretely original to offer except as an appreciator and arranger of other people's—mostly men's—art,

music, and ideas: the composer Rogers's memoirs speak flatly of Gardner as "an echo rather than a voice."[98] Such a dismissive attitude, which the finely tuned Gardner may well have sensed in Rogers and others, would likely have offended her. In addition, Gardner, ever eager for social approval—for consorting with winners—may have preferred to take some distance from women who were still fighting for recognition from the men in their own field; among the most embattled were, precisely, composers and painters (as opposed to writers, whose ambitions were considered somewhat more acceptably ladylike under the gender code of the day).[99]

Building a City's Music

Our final topic, patronage of institutions, can only be discussed here in a preliminary way; more detail will no doubt be forthcoming as scholars learn more about the origins and economic structure of Boston's many important musical organizations. Gardner was for twelve years (1899–1911) a vice president of the Orchestral Club of Boston—an amateur orchestra—and was a guarantor of the Boston Musical Association, established in 1919 by Georges Longy to perform contemporary works. Both involved female musicians—many of them Loeffler's students—as well as male ones.[100] As a longtime friend of B.J. Lang's,[101] she quite possibly was also a regular sponsor of his several choral societies; she may also have taken some interest in the South End Music School, a settlement-house institution of which her friend Arthur Foote was president for ten years (his daughter Katharine, who was Gardner's goddaughter, taught there).[102] Gardner may have helped to establish the Boston Opera Company in 1909 (she was present when the cornerstone was laid), was "devoted" (says Carter) to certain of the singers (Alice Nielsen, Maria Gay, Giovanni Zenatello, Vanni Marcoux), and served as its link to the exigent Nellie Melba.[103]

Of course, there were limits to the number of different institutions she could support in a major way, and she knew it. When the Opera Company fell on hard times in its second season (it folded five years later), Loeffler as a member of the board, tried to persuade Gardner to help save it. She replied with regret: "If I had not already yoked my chosen heavy load [i.e., the museum] to my shoulders, it would be a joyful thing to be the one to carry this one."[104]

But of all Boston's institutions, in whatever field, it was the Boston Symphony Orchestra that claimed her allegiance most fully. She frequently attended concerts of the Boston Symphony, including its "Pops" series.[105] (When she broke her ankle, she had her servants carry her up to her balcony seat in a hammock.)[106] And in 1916, in the midst of getting the Music Room rebuilt into four separate galleries in time for the announced "public days" at which visitors could tour her collection, she could not stay away from concerts: "The Russian ballet is delightful—and our orchestra a wonder—I am afraid music has a pull!"[107] She was on friendly terms with a number of its players, including the clarinetist Léon Pourtau (who was also an amateur painter), and, to varying degrees, with at least five of its first

eight musical directors: George Henschel, Gericke, Karl Muck, Henri Rabaud, and Pierre Monteux. (But not, as far as the surviving letters reveal, with Emil Paur, Max Fiedler, or Arthur Nikisch; she actively disliked the latter's highly individual Beethoven interpretations.)[108] She was particularly close to Muck and his wife Anita and was one of the few Bostonians to remain loyal to them during World War I, when the aged and ailing German-born conductor was interned in Georgia as an enemy alien and irresponsibly assailed in the press.[109]

Her closest link to the orchestra, though, was through its founder, Henry Lee Higginson. Jack Gardner and Higginson had been business associates as well as friends, and Henry's wife Ida (daughter of the scientist Louis Agassiz) had been a dear friend of Isabella's since their schooldays in Italy. During the early years after Jack's death, Higginson helped manage Isabella's ample finances; letters of Higginson's in the museum show him trying to explain or defend his caution in investing her funds ("I know you like quick stocks").[110] He also did not hesitate to give her advice about how to spread her money around among various worthy musical causes. On one occasion, for example, he urged her not to accede to a request for money from a well-known singer;[111] on another, he told her bluntly that he expected her to do rather more for the Opera Company than, it seems, she had planned:

You've been to the opera this week, & have been more or less edified.

You know the value to us of an opera on a solid & healthy basis. . . .

Give these folks a chance and some timely help, & we may get an excellent article.Give them cold water & we shall help to break down an experiment, which will not be repeated in a hurry—The laborers are earnest & able—Spare the criticisms for the minute s.v.p.—Pray go to that meeting tomorrow at 3 o'ck & help in your own way . There are more ways than one, & no quick-witted party (woman) needs hints from a dull-witted party (man) as to the methods.

Bear a hand, Lady.[112]

Higginson could make such a demand of her because he knew that she shared his own goals for musical life in Boston. In particular, he knew of her devotion to the Boston Symphony. To some extent this devotion was expressed financially. Gardner paid at a fund-raising auction $1,120—nearly fifty times more than the combined box-office value of $24—for a pair of the best subscription seats in the new house (Symphony Hall), a fact reported with astonishment in the Boston Transcript .[113]

It would probably be wrong, though, to overemphasize the Gardners' purely financial contributions to the orchestra."[114] Carter astutely notes that "the rôle of godmother" (rather than parent) to a performing organization "particularly suited her; it did not entail the expense of maintaining the child nor the responsibility for its behavior, but entitled her to take a lively interest in its training."[115] The institution in question is the Boston Opera Company, but the point is surely even more valid for the Boston Symphony, which was from the outset funded by Higginson himself rather than by a consortium of donors. There were countless ways in which a "godmother" or "godfather" might encourage the growth of an orches-

tra; or, as Higginson put it regarding the Boston Opera, there are "more ways than one" to "bear a hand." One might attend concerts regularly, praise the orchestra to one's wealthy and trend-setting friends, hire players for private concerts, welcome visiting conductors and soloists into one's tastefully resplendent home. All of these things, the evidence shows, Gardner did.[116] Most important, she must have helped Higginson feel that the whole project was worthwhile, even during times of crisis and near-despair (such as Muck's internment). In a letter of 1900, Higginson specifically expressed his gratitude that Gardner and her late husband stood by him "throughout my experiments" with the orchestra: "No success is won by one alone. Thank you & the dear old fellow for many, many kind words & kinder deeds."[117] The precise words and deeds that Higginson found so supportive will probably never be known, but the few surviving letters from Higginson leave little doubt that he considered Jack and "Mrs. Gardner" (as he seems always to have called her) his comrades-in-arms in the fight to establish a first-rate symphony orchestra in Boston.[118]

The Path and the Blessing

By way of conclusion, one last pungent letter from Higginson deserves to be quoted here. The immediate impetus behind it is unclear, but Carter reasonably suspects that it refers to the museum. (Gardner had lost a recent skirmish in her long battle over its tax status.)

Boston, June 1, 1905

My dear Mrs. Gardner,

If you think that you are to have a peaceful life, die at once! So soon as a person has shown his capacity to help his fellow creatures and his will to do so, he will be asked again and again—

It is a price and a joy of life—I am glad that you (for your own sake & for Jack's—the kindest man on earth—) have fallen into that class—You chose the path and are a blessing to many men & women.

Very truly,

H. L. Higginson[119]

These words may be justly applied to almost every aspect of Gardner's artistic endeavors and not least to her varied and intensive involvement with music. The pianist Gebhard later recalled the years from 1900 to 1918 as "the 'Golden Age of Music' in Boston,"[120] which, almost by definition, makes it also one of the most distinguished episodes in the history of art music in America. Many music historians would agree with the assessment: during these years major local and visiting interpreters (including the conductors Muck, Nikisch, and Monteux) brought the best of Europe's art music, including the newest masterworks by Debussy and Strauss, to the city; they also promoted the work of the best American composers

of art music (with the notable exception of that puzzling and prickly modernist Charles Ives), including members of what is now called the Second New England School": Loeffler, Arthur Foote, Amy Beach, and George Whitefield Chadwick. Bernard Berenson, writing from Florence, could rightly envy his Boston friend: "How I wish I had been there to hear Loeffler's Pagan Poem! You are in luck to have all that music. Here we are senza ."[121] For helping to foster this musical Golden Age, Berenson's correspondent herself should be given a great deal of credit. Like others in her position, but with a special intensity and flair, and with a true connoisseur's taste, she "chose the path" of fostering beauty in a merchant city. Although not a Bostonian by birth, her irrepressible presence there for over half a century was—in music as in visual art—"a blessing to many men and women."[122]

None of this should imply, though, that Gardner was some kind of saint, or selfless giver; quite the contrary, she could be imperious (as the reminiscence of the violinist Harrison Keller attests—see Vignette D) and artfully attention-getting. But at a time when government and corporate support for the arts was minimal (a condition to which we are, it seems, gradually returning in the waning years of this century), art music could ill afford to rely entirely on saints: nearly as good was a collection of activist supporters who, for whatever reasons of status and ego-gratification, chose to divert some of their wealth away from caviar and silks and toward the masterpieces of the past, the risk-taking composers of the present, and the accomplished singers and instrumentalists who enable musical art and its valued traditions to survive for the enrichment of the future.

Music, it is true, suffered from the whims and prejudices of these moneyed individuals; recent studies have rightly drawn attention to the ways in which concert life in America was framed as something high-toned, socially exclusive, even intimidating, and so lost the chance to develop support among the bulk of the citizenry.[123] Private patronage perhaps inevitably results in what sociologists call a "tension of mission": universities more easily find donors to put up a splendid new building that will bear their name than to repair the roof of an existing one, keep a lid on tuition, or pay a living wage to the graduate students and adjunct faculty who do much of the teaching. But, like a university education, art music would scarcely exist in America—or at least would not be available in sufficient quantity, in worthy performances, and at a price within the means of the average music lover—without those sometimes willful patrons.

Furthermore, and thanks often to their very willfulness, the best of the patrons stamp our musical life with what can fairly be called their own organizational and aesthetic genius. Such a one, in music as well as visual art, was Isabella Stewart Gardner. Her various musical projects—her support of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Opera Company, the Kneisel Quartet, the composer Charles Martin Loeffler, the singer Lena Little, and various young musicians of talent, but also her intriguing, sometimes idiosyncratic, experiments in bringing music new and old out of the concert hall (or out of the dust of the library) and back into the living environment of the home—all deserve the thoughtful atten-

tion of music and social historians and of those who ponder how art music might today become (or become again) a vital part of American society.

Vignette D—

Playing for Mrs. Gardner Alone:

The Violinist Harrison Keller Reminisces

Annotated by Ralph P. Locke

Harrison Keller (1888–1979) was an active young professional violinist when he played for the aging but still imperious Isabella Stewart Gardner with the pianist Heinrich Gebhard, who was one of her devoted musician friends (and later piano teacher to Leonard Bernstein and Lukas Foss).

Keller, who was born in Delphos, Kansas, had settled in Boston, after returning from several years of study in Germany and Russia (finishing up in 1914 with the great Leopold Auer) and then serving for a time in the U.S. Army. He was particularly active in chamber music, eventually founding and leading the Boston String Quartet (1925–47). In 1922, a few years after the rather eventful concert for Gardner that his letter describes, Keller was named head of the string department at the New England Conservatory; from 1947 to 1952 he was that institution's sixth director and thereafter served as president of the board.

The letter printed below was written to Rollin van N. Hadley, director of the Gardner Museum, apparently in response to a request for some reminiscences about the museum's founder.[1] Keller, at eight-three, re-calls with some vividness how he and Gebhard played to Gardner, with no other listeners present, on a certain Christmas Day (year not stated), just before she was felled by a debilitating illness. This sudden illness must be the stroke that she suffered on 26 December 1919, which left her partly paralyzed (although not as continuously bedridden as Keller implies) for five years until her death in 1924.[2] Keller's tone mingles bemusement, professional pride, and lingering admiration for this sometimes puzzling patron of artists and musicians.

Harrison Keller

25 Garden Road

Wellesley Hills, Mass. 02181

December 14th, 1973

Dear Mr. Hadley

I have your letter of the 12th and I am, of course, glad to give you a brief account of one interesting occasion requested by Mrs. Gardner for whom we had often performed works she admired: Franck, Fauré, d'Indy sonatas for violin and piano, etc.

This request or "command performance" was for Christmas Day [1919] at 12 noon for Heinrich Gebhard and myself to play for her a new work which we had introduced both here and in New York. Triptych by Carl Engel [,] a good friend of Mrs. Gardner.

We understood she was ill and would have no guests.

We were ushered into the music room [i.e., the Tapestry Room] and found Mrs. Gardner seated in the window looking into the court[yard], which was a blaze of [floral] color.

She was dressed as though going for a drive, which she so often did—she carried gloves, her bag—and as usual had a slip of paper on which she had noted questions she wished me to answer and waste no time on meaningless conversation.

We proceeded to play the Engel work, then [the] Brahms D-minor Sonata which she had requested. Also—she seemed puzzled by the Engel and delighted with the Brahms—after which she expressed the wish "I would just love to hear the Franck; do you have the music?" I told her no but Mr. G. and I knew it from memory and would gladly play it.—As we started for the piano she called me back with a worried look on her face.—"O, dear no, I just can't bear to have anything happen to it."

She [had] suddenly lost confidence in our memories!!

We were told that immediately after we left she was carried to her room and put to bed, which she never left again.

It was characteristic of her to have us feel that she was her usual self and was willing to be presented as in other days.

Courage of which she possessed beyond most.

Sincerely yours,

Harrison Keller

Vignette E—

Premieres of Sibelius and Others in the Connecticut Hills:

Carl and Ellen Battell Stoeckel's Norfolk Music Festivals

Pamela J. Perry

Some tales of patronage treat a decade or two; some feature a woman, or a man, or a group of women or men. The story of the Norfolk Music Festivals and the Norfolk Music School covers nearly two centuries and features generation after generation of men and women from two very different families, joined by a marriage, a love of music, and a willingness to use privilege and inherited money for the public good.

Joseph Battell was a successful merchant in the Norfolk area of Connecticut. Several of his children gave generously of their inherited wealth to Yale University, notably Irene Battell Larned (1811–77), who made the first endowment in the field of music at Yale, and Joseph Battell, Jr. (1806–74), who provided funds for the construction of the university's Battell Chapel and established a fund for instruction in sacred music that was later enlarged by other members of the family. (Irene's husband William was a Yale professor of history.) The seventh of the nine children was Robbins Battell (1819–94), active in business and state politics, and manager of the family investments after his brother Joseph's death. Robbins was an expert flutist, sang in the choir of Norfolk Congregational Church for forty years, and gave sets of chimes to several colleges (and was frequently called upon to repair and tune them). Several hymns of his composition were published in hymnals. He helped establish courses in music at Yale, where he proposed that Gustave Stoeckel (1819–1907), a German émigré, be hired as professor, and secured the needed $20,000 for this venture from one of his sisters. (Stoeckel soon became a major force in America's musical life, not least by establishing the tradition of the college male glee club; he also organized the New Haven Philharmonic and composed six operas.)[1] Robbins's biggest contribution to music, though, was his establishing of the Litchfield County Musical Association, which gave concerts, including excerpts from oratorios, in various towns throughout the rolling hills of northern Connecticut.

Robbins's wife, the former Ellen Ryerson Mills, had died at the birth of their only child. This daughter, also named Ellen (1851–1939), was early trained in piano and voice and fre-

Vignette E is based on a more detailed chapter on the Battells and the Stoeckels in Pamela J. Perry, "The Role of Women as Patrons of Music in Connecticut during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries" (D.M.A. diss., University of Hartford, 1986). On patterns of women's patronage in Connecticut and the outlook for the future, see Pamela J. Perry, "Women as Patrons of Music: The Example of Connecticut, 1890–1990," Journal of the International League of Women Composers , June 1992, pp. 9–11.

quently performed in church and community musical events; moreover, she clearly took it upon herself to continue her father's mission and did so in imaginative and principled ways. Several months after Robbins's death in 1895 (she had lived with him for years after being herself early widowed), Ellen married Carl Stoeckel. Seven years her junior, Carl was son of the aforementioned Yale music professor, had been educated under private tutors in America and Europe, and in recent years had been employed by Ellen's father as personal secretary. Most crucial, he shared his father's, and the Battells', love of music. The couple's life together can largely be told as a series of projects to enhance the cultural life of their region, and, through Yale University, of the nation and the larger musical world. Both Ellen and Carl were so modest that much of what they did for others will never be known. Ellen was most definitely the source of funds for these projects (being the sole heir of the Battell family's wealth), although this fact has rarely been mentioned; Carl tended to receive more public credit than Ellen, because he served as the primary manager and administrator, but even he kept a relatively low profile.

In 1897 Ellen began to sponsor informal evenings of English glee-singing in their home, the Whitehouse. The following year, she founded the Norfolk Glee Club and conducted it in its first concert in the house's large library. The organization grew large enough to venture a performance of a British oratorio, Alfred R. Gaul's The Holy City , in Norfolk Congregational Church. By this point, a male conductor, N. H. Allen of Hartford, had been brought in to conduct. "The organization had become too large to be directed by a woman," Carl Stoeckel dryly noted.[2]

In 1899 the couple founded the Litchfield County Choral Union, whose every concert program contained an announcement of its aims: "to honor the memory of Robbins Battell, and with the object of presenting to the people of Litchfield County choral and orchestral music in the highest forms. . . . No tickets are sold[,] . . . the sole object being to honor the composer and his work, under the most elevated conditions."[3] From 1900 until 1922, the Norfolk Music Festival, as it came to be known, presented some of America's and Europe's finest performers and musical works: solo pianists, violinists, and singers, such as Sergei Rachmaninoff, Fanny Bloomfield-Zeisler, Maud Allan, Fritz Kreisler, Alma Gluck, and Louise Homer; pieces for chorus and an orchestra of close to a hundred, brought in by special train from New York (largely Philharmonic and Metropolitan Opera players); and numerous compositions for orchestra alone. The Choral Union itself grew, through the creation of local choruses in various towns, which then joined forces for an annual festival. By the third season, the Winsted Armory was already becoming too small for the concerts. The sixth and later seasons were held in a wooden "Music Shed," expressly built for the purpose on the Battell estate; its excellent acoustics are still appreciated today.

The most striking feature about the festivals is the Stoeckels' commissioning of numerous new musical works—usually with chorus, sometimes for orchestra alone—by renowned composers. Word of their generosity spread, and, for the 1915 festival alone, forty-two ap-

plications for commissions were received, unsolicited, from composers in the United States and Europe. The Stoeckels always ignored such appeals and instead went straight to the composers who most interested them. The festival saw the premieres of American works by such composers as Victor Herbert, Henry Hadley, Charles Martin Loeffler, Horatio T. Parker, Frederick Stock (better known as conductor of the Chicago Symphony), Henry F. Gilbert, David Stanley Smith, John Powell, and Victor Kolar. The honored composer generally conducted his new work, or even the entire concert.

Foreign composers, too, accepted the Stoeckels' offers, and were pleased, even startled, at the high quality of the performances. In 1910 Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a prominent English composer of African descent, came to Norfolk for the premiere of his composition The Bamboula: Rhapsodic Dance . The local newspaper conveyed his enthusiasm:

The composer, Coleridge-Taylor said that yesterday was the happiest day of his life. He pronounced last evening's concert the best performance of his music he had ever heard. . . . He never liked America before this visit. He was astonished at the playing of American orchestras and considers them way ahead of anything in Europe. With only one rehearsal, he considers the rendition of the Bamboula rhapsodie most remarkable. . . .

Among the guests of honor at the concert was the composer of last year's [commissioned] work, "Noel" [later incorporated into his Symphonic Sketches ], George W. Chadwick. . . . He was delighted beyond measure with the concert. He has been commissioned by Mr. and Mrs. Stoeckel to write another composition, probably orchestral.

Horatio Parker of Yale, with his wife and daughter, were also guests of honor. He also has been commissioned. . . .

The artists were all entertained at supper by Mr. and Mrs. Stoeckel after the concert and later they gathered in the library and treated Coleridge-Taylor, the guest of honor, to a lot of American airs, spending a very informal and happy time. Coleridge-Taylor was called upon for a speech. . . . He said that . . . he was going home with a new idea entirely of American musical progress. At every festival he attended hereafter he was going to give an account of what was being done at Norfolk.[4]

The unfailingly original Australian-born composer and pianist Percy Grainger composed a new orchestral suite for the 1916 festival (In a Nutshell ) and, as if that were not enough, also played Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto. But perhaps the height of the Stoeckels' commissioning project was Jan Sibelius's The Oceanides , Op. 73 (after an episode from the Kalevala ), which received its premiere at the 1914 festival, under the composer's baton. Sibelius had declined numerous American invitations but could not resist the flattering offer and the tone of Carl Stoeckel's letter, which showed the latter to be a "distinguished personality with a knowledge of music."[5] After one rehearsal with the festival orchestra, Sibelius exclaimed in a letter: "The orchestra is wonderful!! Surpasses anything we have in Europe. The woodwind blend is of such an order that you have to put your

hand to your ear to hear them in ppp even if the cor anglais and bass clarinet are there. And even the double-basses sing."[6] Years later, he still recalled the "high-class audience, representative of the best that America possessed among lovers of music, trained musicians, and critics. The most inspired setting for the appearance of an artist."[7] The Stoeckels introduced Sibelius to former President Taft and to many important figures in American musical life: to Maud Powell, for example, who had helped popularize his Violin Concerto, and (at a banquet that the Stoeckels sponsored in his honor in Boston) to "most of the American composers"—as Sibelius proudly, if naively, put it in a letter to his brother—including Chadwick, Hadley, Loeffler and Frederick S. Converse.[8] Sibelius was impressed by the variety of the Connecticut landscape, by the racial and religious diversity of the people he met—"Negroes and whites, Methodists, Quakers, and Lutherans!"—and by seemingly everything about his "enormously wealthy and well educated hosts.[9] When he expressed a desire to see Niagara Falls, the Stoeckels rented a train and off they all went; the meals aboard the train were catered by Delmonico's Restaurant of New York.

Not surprisingly, the festivals were said to have cost the Stoeckels $25,000 a year (a sum equal to ten times that amount or more today).[10] The Stoeckels never spared expense, hiring the conductor, the soloists renting unusual instruments and the like when needed, and providing rented trains for all the various assisting choruses; furthermore, there was no offsetting income: tickets were always given away without cost, two per chorister, and requests poured in from as far away as California. The festivals ceased in 1922: perhaps Carl Stoeckel had become ill or weak, for he died three years later. But Ellen Battell Stoeckel reestablished community hymn sings in 1927 in the Music Shed, with a fifty-piece orchestra from New York and no audience but the singers themselves.[11]