Preferred Citation: Ruderman, David B., editor Preachers of the Italian Ghetto. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft829008np/

| Preachers of the Italian GhettoEdited by David RudermanUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1992 The Regents of the University of California |

For Tali

With Great Affection

Preferred Citation: Ruderman, David B., editor Preachers of the Italian Ghetto. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft829008np/

For Tali

With Great Affection

Illustrations

- Figure 1. First page from Jacob Ẓahalon’s Or ha-Darshanim (A Manual for preachers) (London, 1717).

- Figure 2. Title page from Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen’s Shneim-Asar Derashot (Venice, 1594).

- Figure 3. Title page from Judah Moscato’s Sefer Nefuẓot Yehudah (Venice, 1589).

- Figure 4. Title page from Judah Assael Del Bene’s Kissot le-Veit David (Verona, 1646).

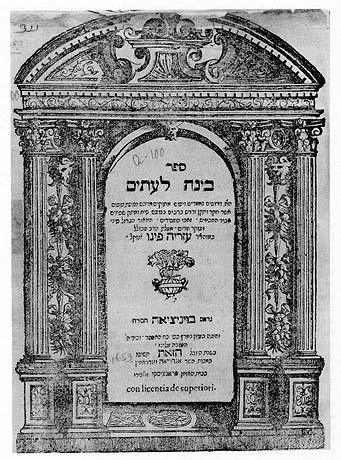

- Figure 5. Title page from Azariah Figo’s Binah le-Ittim (Venice, 1653).

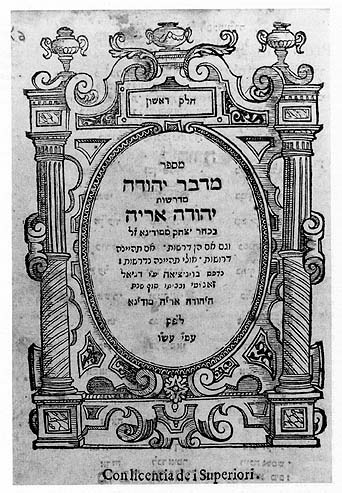

- Figure 6. Title page from Leon Modena’s Midbar Yehudah (Venice, 1602).

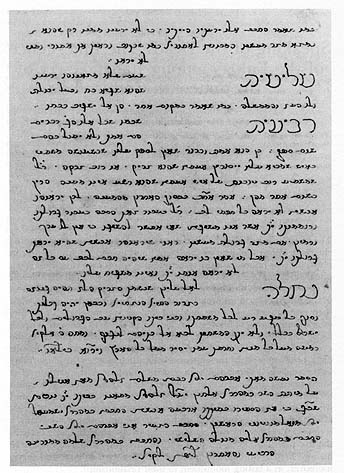

- Figure 7. Manuscript page from a collection of funeral sermons of Abraham of Sant’Angelo.

1. Introduction

David B. Ruderman

When in 1581 the English cleric Gregory Martin published his personal reflections on Rome, he singled out the Italian preachers whose activity he had observed:

And to heare the maner of the Italian preacher, with what a spirit he toucheth the hart, and moveth to compunction, (for to that end they employ their talke and not in disputinge matters of controversie which, god be thanked, there needeth not) that is a singular joy and a merveilous edifying to a good Christian man.[1]

Father Martin’s panegyric on the pleasure of listening to a moving sermon was surely not an atypical response to the phenomenon of preaching in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As Hilary Smith remarks, the same scenario was reported all over Europe: “large congregations sitting (or standing) spellbound at the feet of a preacher who, by the sheer power of his eloquence and personal magnetism, was able to hold their attention for an hour or possibly longer.”[2] Of course, the good friar meant Christian preachers and their sermons, those he seemed to encounter wherever he wandered in Rome: in the major churches, in the hospitals and convents, and even in the piazzas. There is no doubt that he also noticed a community of Jewish residents in the city of the popes during these meanderings. He acknowledges hearing “the voices of the holy preachers” in their regular weekly meetings with the Jews, exhorting them to convert to Christianity.[3]

One wonders if Father Martin could have also known that, besides that painful obligatory hour of Christian proselytizing to which the Jews of the Roman ghetto were subjected, they, too, willingly flocked to their own predicatori on Sabbaths and on special occasions. It was not uncommon for some curious Christians to be present in ghetto synagogues during the delivery of the sermon. The Jews, like the Jesuits Martin described, might have expounded in their own manner, of course, on “some good matter of edification, agreable to their audience, with ful streame of the plainest scriptures, and piked sentences of auncient fathers, and notable examples of former time, most sweetly exhorting to good life, and most terribly dehorting from al sinne and wickedness, often setting before them the paines of hel, and the joyes of Heaven.”[4] Most probably, such a scenario was invisible to the pious Christian gentleman who, like many of his contemporaries, had little reason to intermingle with Jews in their own houses of worship, and who could not deem them worthy of his attention except as potential candidates for the baptismal font.

First page from Jacob Ẓahalon’s Or ha-Darshanim (A Manual for preachers) (Lon don, 1717). Ms. 1646:33. Courtesy of the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

In reality, however, the period of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was not only an age of the sermon for Catholics and Protestants but for Jews as well. Just as Christian preachers were increasingly committing their most effective homilies to print for an enthusiastic reading public, so their Jewish counterparts were similarly inclined to polish their oral vernacular sermons, to translate them into elegant Hebrew prose, and thus to satisfy the equally voracious appetite of their Hebrew reading public. In Italy, in Amsterdam, in the Ottoman empire, and in Eastern Europe, the Jewish preacher assumed a status unparalleled in any previous age, and the interest of a Jewish laity in hearing and reading sermons reached unprecedented heights.[5] This new role of the darshan, the Jewish counterpart to the “sacred orator,” as mediator between Jewish elite and popular culture, effected through the edifying delivery and eventual diffusion of his printed sermons, undoubtedly closely approximates similar cultural patterns emerging throughout early modern Europe. Yet Jewish preachers and their sermons, particularly those emerging in the Italian ghetto, also reflect a cultural ambiance unique to Jews, emanating from the special characteristics of their cultural heritage and the specific circumstances of their social and political status in Italy.[6]

A book exclusively devoted to Jewish preachers and their sermons delivered in the Italian ghetto is surely a novelty even in our present day, one of dramatic proliferation of books on Jewish studies in Israel, the United States, and Europe. Indeed, with few exceptions, the historical study of Jewish homiletical literature in all periods, despite its centrality and pervasiveness within Jewish culture, is still in its infancy. Surely this deficiency follows the general pattern: the history of Catholic and Protestant preaching in early modern Europe still remains a relatively underdeveloped field. Whether the state of research on Jewish preaching is the same or worse is a matter of conjecture. What is clear, however, as Marc Saperstein amply relates in his essay below, is that even the major Jewish sermon collections in print have not been adequately studied. Thousands of sermons still in manuscript, primarily in Hebrew but also in Italian, have been almost completely neglected, and historians have only infrequently utilized this material in reconstructing the social and intellectual world of Italian Jewry in this period.

This modest volume does not purport to correct these deficiencies. It considers only a handful of well-known Italian preachers, and only a small sampling of their prodigious literary corpus. But as a beginning, it highlights several salient features of Jewish preaching within the context of the Italian ghetto in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and it attempts to extrapolate from this context something more about the nature of the Jewish cultural ambiance in general. Before introducing the larger social and cultural context of Jewish life in the ghetto period, and before highlighting some of the major themes discussed in the essays below, a few words of explanation about the genesis of this project are in order.

The idea of this book grew out of an invitation I extended to three scholars in the field of Renaissance and Baroque Italian Jewish intellectual and social history to join me at Yale in a faculty seminar during the spring of 1990 on the subject of Jewish preachers of the Italian ghetto. Moshe Idel, Robert Bonfil, and Joanna Weinberg graciously accepted my invitation. Each of us decided to select a distinguished preacher of the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century and to explore the larger Jewish cultural landscape of his age from the vantage point of his sermons. We had all written considerably on this period but had rarely approached our subject exclusively from the perspective of sermons and their cultural setting, and we had never worked in concert. We agreed not to impose on our sessions any defined agenda; each researcher would decide independently which features of the sermons to stress, whether their content or form, or both; their connection to larger cultural issues, to Jewish-Christian relations, to popular culture, to the diffusion of kabbalah, and so on. Each of us presented an original paper in the seminar and engaged in a most stimulating and fruitful discussion with the others and with other invited Jewish historians and colleagues at Yale. In addition, I invited Marc Saperstein, the author of a recent volume on Jewish preaching, to offer a general overview of our subject from the comparative perspective of preaching in other Jewish communities. Finally, I asked Elliott Horowitz, another Jewish historian of early modern Italy, who had visited Yale during the previous year, to contribute a chapter on funeral sermons, a subject related to his own research. The results of this collective effort are now before the reader.

| • | • | • |

The world inhabited by Jewish preachers and their congregations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was a fundamentally different one from that of their immediate predecessors of the medieval and Renaissance periods. A new oppressive policy instituted by Pope Paul IV and his successors in the middle of the sixteenth century caused a marked deterioration in the legal status and physical state of the Jewish communities of the papal states and in the rest of Italy as well. Jews living in the various city-states of Italy suddenly faced a major offensive against their community and its religious heritage, culminating in the public incineration of the Talmud in 1553 and in restrictive legislation leading to increased impoverishment, ghettoization, and even expulsion. Jews previously had been expelled from the areas under the jurisdiction of Naples in 1541. In 1569, they were removed from most of the papal states, with the exception of the cities of Ancona and Rome. Those who sought refuge in Tuscany, Venice, or Milan faced oppressive conditions as well. The only relatively tolerable havens were in the territories controlled by the Gonzaga of Mantua and the Estensi of Ferrara.

The situation was further aggravated by increasing conversionary pressures, including compulsory appearances at Christian preaching in synagogues and the establishment of transition houses for new converts which were designed to facilitate large-scale conversion to Christianity. Whether motivated primarily by the need to fortify Catholic hegemony against all dissidence, Christian and non-Christian alike, or by a renewed zeal for immediate and mass conversion, spurred in part by apocalyptic frenzy, the papacy acted resolutely to undermine the status of these small Jewish communities in the heart of western Christendom.[7]

These measures stood in contrast to the relatively benign treatment of Jews by the Church and by secular authorities in Italy throughout previous centuries. Jewish loan bankers had initially been attracted to northern and central Italy because of the generous privileges offered them by local governments eager to attract adequate sources of credit for local businesses and, in particular, for small loans to the poor. As a result of the granting of such privileges to individual Jews in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, miniscule Jewish communities grew up throughout the region, consisting of Jews who had migrated from the southern regions of Italy and of other immigants from Provence, from Germany and eventually from Spain. The backbone of these communities was the entrenchment of successful loan bankers who had negotiated legal charters (condotte) for themselves and those dependent upon them, and who also carried the primary burden of paying taxes to the authorities. By the sixteenth century, Jewish merchants and artisans joined these communities, until eventually the moneylenders were no longer in the majority.[8]

In the relatively tolerant conditions of Jewish political and economic life until the mid-sixteenth century, the cultural habits and intellectual tastes of some Italian Jews were stimulated by their proximity to centers of Italian Renaissance culture. A limited but conspicuous number of Jewish intellectuals established close liaisons with their Christian counterparts to a degree unparalleled in earlier centuries. The most significant example of such Jewish-Christian encounter in the Renaissance took place outside of Florence in the home of the Neoplatonic philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. Out of a mutually stimulating interaction between Pico and his Jewish associates and a prolonged study of Jewish books emerged one of the most unusual and exotic currents in the intellectual history of the Renaissance, the Christian kabbalah. In an unprecedented manner a select but influential group of Christian scholars actively sought to understand the Jewish religion and its sacred texts in order to penetrate their own spiritual roots more deeply. Such a major reevaluation of contemporary Jewish culture by Christians would leave a noticeable mark on both Christian and Jewish self-understanding in this and later periods.[9]

The new cultural intimacy of intellectuals from communities of both faiths could not, however, dissipate the recurrent animosities between Jews and Christians even in the heyday of the Renaissance. In the fifteenth century, Franciscan preachers such as Bernardino da Siena and Antonino da Firenze openly attacked the Jewish loan bankers and their supposedly cancerous effect upon the local populace. Others, like Bernardino da Feltre, launched the drive to establish monti di pietà, public free-lending associations with the avowed purpose of eliminating Jewish usury in Italy altogether. Such campaigns often led to painful consequences for Jewish victims: riots, physical harassment, even loss of life, as in the case of Bernardino’s most notorious incitement, his charge of Jewish ritual murder in the city of Trent in 1475. If there was a shelter from such disasters, it was the fragmented political nature of the Italian city-states along with the highly diffused and sparsely populated Jewish settlements throughout the region. Aggressive acts against Jews were usually localized and relatively circumscribed; the Jewish victims of persecution often found refuge in neighboring communities and even found ways to return to their original neighborhoods when the hostilities had subsided.[10]

By the middle of the sixteenth century, the new legislative measures affecting the conditions of Jewish life on Italian soil effectively altered this social and cultural climate to which Jews had grown accustomed. The most conspicuous transformation was the erection of the ghettos themselves, those compulsory Jewish quarters in which all Jews were required to live and in which no Christians were allowed to live. The word was probably first used to describe an area in Venice, supposedly because it had once been the site of a foundry (getto-casting), selected as early as 1515 as the compulsory residential quarter for Jews. With the passage of Pope Paul IV’s infamous bill Cum nimis absurdum in 1555, the ghetto of Rome came into being, and similar quarters gradually spread to most Italian cities throughout the next century.[11]

The notion of the ghetto fit well into the overall policy of the new Counter-Reformation papacy. Through enclosure and segregation, the Catholic community would now be shielded from Jewish “contamination.” Since Jews could more easily be identified and controlled within a restricted neighborhood, the mass conversionary program of the papacy could prove to be more effective, and the canon law could be more rigidly applied. The conversionary sermons to which Friar Martin had listened were an obvious manifestation of this new reality of concentrating larger numbers of Jews in cramped and restricted neighborhoods and of constantly harassing them materially and spiritually. Another was the severe economic pressure placed upon many Jewish petty merchants and artisans obliging them to compete fiercely for the diminished revenue available to them within their newly restrictive neighborhoods. Jewish loan banking activities also collapsed, with capital more readily available to Christians from other sources. While pockets of Jewish wealth and power were surely entrenched in ghetto society, a newly emerging class of impoverished Jews was conspicuously present, and a growing polarization of rich and poor became an inevitable consequence of the crowded, urbanized, and intense social settings of the new Jewish settlements.

Yet the ghetto also constituted a kind of paradox in redefining the political, economic, and social status of Jews within Christian society. No doubt Jews confined to a heavily congested area surrounded by a wall shutting them off from the rest of the city, except for entrances bolted at night, were subjected to considerably more misery, impoverishment, and humiliation than before. And clearly the result of ghettoization was the erosion of ongoing liaisons between the two communities, including intellectual ones. Nevertheless, as Benjamin Ravid has pointed out in describing the Venetian ghetto, “the establishment of ghettos did not…lead to the breaking of Jewish contacts with the outside world on all levels from the highest to the lowest, to the consternation of church and state alike.”[12] Moreover, the ghetto provided Jews with a clearly defined place within Christian society. In other words, despite the obvious negative implications of ghetto sequestrations, there was a positive side: the Jews were provided a natural residence within the economy of Christian space. The difference between being expelled and being ghettoized is the difference between having no right to live in Christian society and that of becoming an organic part of that society. In this sense, the ghetto, with all its negative connotations, could also connote a change for the better, an official acknowledgment by Christian society that Jews did belong in some way to their extended community.

The notion of paradox is critical to Robert Bonfil’s understanding of the ghetto experience in his recent writing on the subject.[13] For him, paradox, the mediating element between two opposites, represents a distinct characteristic of transitional periods in history, “a part of the structural transformation instrumental in inverting the medieval world and in creating modern views.”[14] Most paradoxical of all is Bonfil’s contention that the kabbalah, an object of Christian fascination in the Renaissance, became in this later period the most effective mediator between Jewish medievalism and modernity. It became “an anchor in the stormy seas aroused by the collapse of medieval systems of thought” and, simultaneously, “an agent of modernity.”[15] In “conquering” the public sermon, in encouraging revisions in Jewish liturgy, in proposing alternative times and places for Jewish prayer and study, and in stimulating the proliferation of pious confraternities and their extra-synagogal activities, the kabbalah deeply affected the way Italian Jews related to both the religious and secular spheres of their lives. In fact, the growing demarcation of the two spheres, a clear mark of the modern era, constituted the most profound change engendered by the new spirituality.[16]

Along with religious changes went economic and social ones. The concentration and economic impoverishment of the ghetto that engendered an enhanced polarization between rich and poor appeared to facilitate a cultural polarization as well. For the poor, knowledge of Hebrew and traditional sources conspicuously deteriorated. For the rich, elitist cultural activities were paradoxically enhanced. They produced Hebrew essays, sermons, dramas, and poetry using standard baroque literary conventions.[17] They performed polyphonic music reminiscent of that of the Church,[18] entertained themselves with mannerist rhyming riddles at weddings and other public occasions,[19] and lavishly decorated their marriage certificates with baroque allegorical symbols.[20] The seemingly “other-worldly” kabbalist Moses Zacuto was capable of producing “this-worldly” Hebrew drama replete with Christian metaphors, as Bonfil mentions.[21] And ironically, despite the insufferable ghetto, some Jews, undoubtedly the most comfortable and most privileged, seemed to prefer their present status.[22]

In describing the ghetto era in such a manner, Bonfil strongly urges a reconsideration of the importance of the Renaissance era for Jewish cultural history. He claims that the beginning of incipient modernism was not the Renaissance, as earlier historians have thought, but the ghetto age, as late as the end of the sixteenth and throughout the seventeenth century. Moreover, Bonfil urges that one should view this later period not as a continuation of the Renaissance, “a mere blossoming [of Renaissance] trends after a long period of germination,” but as a distinct era in itself, that of the baroque, and that this latter term, used primarily in a literary or artistic context, is also a relevant category in periodizing a unique and repercussive era in the Jewish experience.[23]

The full implications of Bonfil’s revisionist position for the study of Jewish history have yet to be explored. Few historians have employed the term “baroque” in describing Jewish culture during the period from the end of the sixteenth century, and most of the contributors below are reticent to use it in this volume as well. Few are yet prepared (as is this writer) to deny any significance altogether to the Renaissance in shaping a novel and even modern Jewish cultural experience. In fact, Bonfil’s emphasis on the sharp rupture and discontinuity engendered by the ghetto might be tempered by a greater emphasis of the lines of continutiy between the Renaissance and the post-Renaissance eras.[24] Be that as it may, Bonfil’s novel emphasis opens the possibility for a fresh assessment of the ghetto experience with respect to Jewish-Christian relations, Jewish cultural developments, and the ultimate emergence of a modern and secularized temperment, with all its complexities, within the Jewish communities of early modern Europe.

| • | • | • |

Bonfil’s bold interpretation of the cultural experience of the Italian ghetto might serve as a useful backdrop for discussing some of the major themes presented in the essays below. Whether or not the conclusions of each, written from the perspective of one individual preacher and his pulpit, fully conform to Bonfil’s synthesis, the latter at least offers us a theoretical framework in which to compare and assess the particular portraits sketched below, and to attempt to abstract from them some tentative conclusions about the Jewish preaching situation and its relationship to the larger cultural world from which it emerged.

Most of the questions posed by Marc Saperstein in his preliminary overview of Jewish preaching relate directly to the issues raised by Bonfil.[25] He asks whether the study of sermons might shed some light on the vitality or impotency of philosophical modes of thought among Italian Jews, on the degree of popularization of the kabbalah, or on the influence of Christian or classical modes of thought. He is interested in exploring the relationship between the content and style of Jewish and Christian preaching, and between Jewish preaching in Italy and in other Jewish communities. His agenda for further research includes a more thorough study of the education of preachers, the politics of preaching, and the function of the preacher as a social critic and social observer.

Many, if not all, of these questions are addressed in the subsequent essays. We first turn to the portrait of Judah Moscato (Mantua, c. 1530–c. 1593) offered by Moshe Idel, since Moscato’s public career as preacher and rabbi preceded the other major figures included in this volume by several decades, certainly long before the official erection of the ghetto in Mantua in 1612, and even before the public atmosphere for Jews had severely worsened in this relatively tolerant center of Jewish life.[26] No doubt Moscato’s extraordinary use of classical pagan and Christian sources and motifs in his sermons, utterly different from any other Jewish preacher whose sermons are known to us, including Figo, del Bene, or Modena, accounts for Idel’s understanding of the preacher’s achievement. Idel’s acknowledgment of the impact of Renaissance culture on Jewish intellectual life, particularly that part nourished by kabbalistic thought, helps to explain his distinctive approach to Moscato as well.[27]

Idel begins his essay by surveying the history of the kabbalah on Italian soil with particular attention to Mantua. While pointing out the difficulty of establishing a consistent pattern of development within the cultural ambiance of Mantua during the sixteenth century, Idel defines two chief characteristics of the form this study took in this city and throughout Italy from the late fifteenth century through Moscato’s lifetime and even beyond. First, kabbalah was no longer studied within the framework of schools and teachers as had been the case in Spain, but rather autodidactically through books, especially after the first printing of the Zohar in 1558–1560. Second, it was usually interpreted figuratively by both Jews and Christians, as classical pagan literature was received and interpreted during the Renaissance. It was thus correlated within the context of prevailing philosophical and humanist concerns.

According to Idel, Moscato was deeply affected by the syncretistic culture of the Renaissance and he interpreted kabbalistic sources to conform to contemporary non-Jewish patterns. In fact, his published collection of sermons is so replete with diverse quotations from Jewish and non-Jewish literature and so theologically complex that it is hard to imagine that its contents bear much resemblance to oral sermons delivered before an ordinary congregation of worshipers. Accordingly, Idel rules out the possibility of understanding Moscato’s printed essays as actual sermons and considers them instead as “part of the literary legacy of Italian Jews,” a legacy appreciated only by those with specialized knowledge in Jewish and Renaissance culture. In other words, Moscato’s book of sermons offers no evidence of how he functioned as a preacher, as a mediator between high and low cultures, and it cannot be understood as a collection of real oral encounters in the same way as those of del Bene, Figo, or Modena.

Treating Moscato exclusively as an esoteric thinker, Idel provides two telling examples from his writing to illustrate how he attempted to discover a phenomenological affinity between Jewish and Hermetic sources, and how he even misinterpreted a kabbalistic source to conform to a view external to Judaism. Because of its “hermeneutical pliability,” as Idel calls it, the kabbalah was divorced from its organic relationship with Jewish observance, treated as another form of speculative philosophy, and subsequently became for Moscato and others “the main avenue of intellectual acculturation into the outside world.”[28] The hold of general culture was so powerful over this Jewish thinker that the kabbalah was reduced by him to a mere intellectual tile in the complex mosaic of late Renaissance thought.

Given Moscato’s intellectual proclivities, Idel calls him a Renaissance, not a baroque, thinker, despite the fact that he lived in the second half of the sixteenth century. If there was any difference between his “Renaissance” style and that of a thinker like Yohanan Alemanno, the Jewish associate of Pico della Mirandola, who was active almost a century earlier, it was that by his day Moscato had become overwhelmed by the Renaissance. Unlike Alemanno, who had contributed independently to shaping Pico’s thought, Moscato was strictly a consumer, albeit an enthusiastically creative one. In his case, the gravitational center of his thinking had shifted so that the Renaissance and not Judaism became the standard for evaluating truth. His compulsion to harmonize Jewish revelation with other disparate sources was markedly different from the later efforts of del Bene and Figo to separate Judaism from alien philosophies, to demarcate the secular from the sacred, and subsequently, to reassert the uniqueness of the Jewish revelation.

Robert Bonfil’s contribution to this volume deals with the fascinating but generally neglected Judah del Bene, who flourished years after Moscato’s death (Ferrara, 1615?–1678).[29] Bonfil undertakes the formidable task of comparing del Bene’s scholarly essays in his published book Kissot le-Veit David with a sampling of his sermons still in manuscript. In comparing the way a profound thinker might address a wider public audience as opposed to intellectuals alone, Bonfil proposes to underscore the mediating function of the preacher, one who undertakes a negotiation at once between elite and popular culture, between his own desires and those of his audience, between conservation and innovation, between his imagination and reality, and between the Jewish and the non-Jewish world.

Bonfil illustrates how the style of del Bene’s sermons skillfully obscures but nevertheless conveys the explicit messages of his scholarly tome. Although this preacher obstensibly stressed continuity and traditionalism, the discerning observer of his baroque use of metaphor might occasionally disclose a rupture or discontinuity with the past. Del Bene’s use of the metaphor of a snake in one of his sermons, conveying both the evil and the positive attribute of discretion, might suggest his sensitivity to linguistic polyvalence as well as some conceptual affinity to Christian symbolism. More significantly, his seemingly conventional assault on “Greek science” in his sermons should not be taken at face value as the dogmatic pronouncement of an archtraditionalist. When such utterances are examined in the light of his statements in Kissot le-Veit David, del Bene emerges not as an opponent of all rational pursuits but as a staunch anti-Aristotelian. Like his hero Socrates, he strove to liberate his community from its servitude to false gods, meaning for him Scholastic metaphysics. By differentiating the illicit and arrogant claims of philosophy from the hypothetical but useful insights of natural science, del Bene reconsidered the whole structure of knowledge, as Bonfil puts it, realigning “Greek science” with divine revelation rather than rejecting the former altogether. Although he might sound superficially like a medieval preacher, in Bonfil’s eyes he was manifestly modern. And by introducing the new through the mask of the old, he was functioning as a good preacher should, mediating between the one and the other. In adopting such a creative stance in his sermons, Bonfil further suggests, del Bene shared a common front with Jesuit clerics by defending traditional values while embracing the new opportunities offered by the sciences now deemed devoid of metaphysical certainty.

My essay on Azariah Figo (Pisa, Venice, 1579–1637) focuses on an epistemological realignment in the thought of this preacher which closely parallels that of Judah del Bene.[30] I argue here and elsewhere that science was a crucial element in the ghetto ambiance.[31] In an age of revolutionary advances in understanding the natural world, the ghetto walls could not and did not filter out the new scientific discourse just as they could not filter out so much else. When the gates of their locked neighborhood opened at the crack of dawn, young Jewish students were on their way to the great medical schools of Italy: Bologna, Ferrara, and especially Padua. For Jews, the medical schools were exciting intellectual centers offering them new vistas of knowledge, new languages, new associations, and, above all, new values. The communities which sent them to study were energized by their return. More than ever before, Jewish communities were led by men who could creatively fuse their medical and rabbinic expertise. Medicine had always been a venerated profession among Jews, but with greater exposure to a flood of printed scientific and medical texts in Hebrew and other languages as well as to the university classroom, Jews of the ghetto were even more sensitized to the importance of these subjects.

Although not known to be a doctor, Figo had more than a casual interest in medicine, as his sermons amply testify. Like his teacher Leon Modena, he seems to have had serious reservations about the kabbalah, for it played no apparent role in his homiletic presentation of Judaism. What is striking about his espousal of traditional values is his assumption that his listeners were enthusiastic about nature, and that their positive response should be fully tapped in teaching religious values. Precisely like del Bene, Figo was not an antirationalist but an anti-Aristotelian. From his perspective, physics was to be divorced from metaphysics, and subsequently Jews could comfortably dabble in the wonders of the natural world without feeling that such involvements threatened their allegiance to Judaism. The newly emerging alliance between religion and science in the mind of the rabbi meant that science dealt only with contingent facts while religion was empowered with the absolute authority to determine ultimate values.

Displaying the image of man as creator empowered to replicate nature, employing medical and natural analogies to preach ethics, and evoking the language of empiricism to underscore the veracity of the theophany at Sinai, Figo well grasped the mentality of his listeners and sought to translate his Jewish message into a language that they would fully understand and appreciate. In so doing, he revealed a remarkable kinship with those same Jesuit clerics, enthusiasts of science in their own right, who were proclaiming the majesty of God’s creation before their own congregations not far beyond the ghetto gates.

Having considered three preachers up to now, the reader will surely be struck by the apparent contrast between the profile of Moscato on the one hand and those of del Bene and Figo on the other. Perhaps one way of understanding the mind-set of Moscato in relation to that of his younger contemporaries is to view them as representing two chronological stages in the structural development of Jewish thought in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Still enamored of the web of Renaissance correlations and harmonies, to recall the language of Foucault’s well-known description of Renaissance thinking,[32] Moscato had surely tread this path to its very limits. His was truly a revolt against the metaphysical certainty of the Aristotelian world view comparable to that of del Bene and Figo. He consistently sought meaning from a vast array of alternative sources: Plato, Pythagoras, other ancients, and even Church fathers. In so doing, he opened the flood gates to metaphysical uncertainty and lack of faith. Even the hallowed truths of Judaism were in doubt when juxtaposed with a bewildering assortment of other perceived truths and sources. Whether or not Moscato actually produced a single harmony in his own mind, it seems clear that such a message was unattainable to even the most persistent reader of his recondite prose. Such epistemological confusion could not easily be reduced to a mere sermon, to public teaching.

Del Bene’s and Figo’s negative or, at least, cool response to speculative kabbalah, their firm repudiation of the attempt to harmonize Judaism with alien thought, their separation of metaphysics from physics, and their desire to reclaim the priority and uniqueness of the Jewish faith surely represent a negative reaction to the kind of excesses associated with Moscato’s intellectual enterprise (Idel would label them “Counter-Renaissance” types, borrowing Hiram Haydn’s label[33]). Theirs was a novel attempt to redefine the Jewish faith from the perspective of the post-Renaissance world they now inhabited. And having rescued their religious legacy from such subordination to Renaissance culture as that exemplified by Moscato, they were anxious to restate its message clearly and unambiguously to their constituents. They could become effective preachers in a way Moscato could never be.

And what of Leon Modena (Venice, 1571–1648), perhaps the most illustrious Jewish preacher of his generation? Joanna Weinberg’s essay returns us completely to the preaching situation, to the way Modena conceptualized the role of the preacher within Jewish society.[34] Weinberg eschews the temptation to label Modena’s intellectual style—whether medieval, Renaissance, or baroque—and rather concentrates primarily on his homiletical art. Modena had actually defined his own style as a kind of compromise between the rhetorical extremes of Judah Moscato and the simpler language of Ashkenazic or Levantine rabbis, as Weinberg mentions. Even more telling is his “blending of the Christian sermon with the traditional Jewish homily,” a fusion he engendered according to the model of one of the best-known Christian preachers of the Counter-Reformation, Francesco Panigarola.[35] Modena had acquired a copy of Panigarola’s manual for preachers and apparently absorbed many of its prescriptions, as his own sermons fully testify. Panigarola’s work attempted to define the relation of classical oratory and ecclesiastical preaching in mediating between the demands of the secular and the sacred. Modena saw himself in an analogous role within Jewish society. Like the Catholic preacher, he considered the sermon as epideictic oratory; he avoided excessive citations in favor of a refined and polished humanist style; and, as Weinberg’s close analysis of his tenth published sermon illustrates, he closely followed the structural guidelines of Panigarola in presenting traditional rabbinic texts to his Jewish congregation. As Weinberg concludes, the preacher of the Counter-Reformation saw his sermons as an effective means of expressing views of the Church establishment. While Modena’s function in the Jewish community was less formally defined, his preaching role bears a striking affinity to that of his Christian counterpart: “His consciousness of the responsibility of the preacher derived in no small measure from what he learned from his Christian neighbors.”[36]

While Weinberg focuses more on Modena’s preaching style than on the substance of his thought, her conclusions suggest clear analogies with the aforementioned portraits of del Bene and Figo. Whether or not his thoughts betrayed a Renaissance or a post-Renaissance consciousness, his self-image as a preacher was surely shaped along the lines of the Catholic model of the Counter-Reformation era. Like the two other Jews, he was teaching Judaism in a manner not so different from that of the Jesuit preachers only a short canal ride from the Venetian ghetto.

It is interesting to recall in this context that in an earlier essay Moshe Idel labeled Modena “a Counter-Renaissance” figure because of his attempt to disassociate Jewish faith from the kind of Renaissance interpretations of the kabbalah so characteristic of Moscato’s thought.[37] Could Modena’s attempt to distance himself from Moscato’s homiletical style be more broadly understood as a critique of the latter’s entire intellectual approach? Whatever the case, Modena adopted a fideistic position advocating a direct return to the sacred texts of Judaism; his critique of the kabbalah, which he defined as a Platonistic forgery, was “a natural consequence of this endeavor,” as Idel put it.[38] Like del Bene and like Modena’s own student Figo, he approved of the divorce of Aristotelian metaphysics from Judaism, and like them, he openly encouraged the Jewish study of the physical world and medicine.[39] Although Weinberg mentions and does not discount this interpretation, she prefers to focus here on Modena’s mode of preaching. One wonders, however, whether Modena’s preaching style might still be considered along with his ideals as a religious thinker and spokesman of Judaism. John O’Malley’s pioneering study of the sacred orators of the papal court during the Renaissance is suggestive in this regard. His work reveals how the medium of the sacred orators and the papal messages were organically linked.[40] Similarly, Modena’s preaching style, which Weinberg has so ably identified, might be integrated successfully with the emerging intellectual agenda common to the other preachers of the ghetto we have previously considered; that is, their attempt to break with the past and to steer Jewish faith on a new course, restructuring the relationship between the sacred and profane in a manner not unlike that of their Catholic colleagues.

Elliott Horowitz’s treatment of Jewish funeral sermons breaks new ground in directions quite different from the other essays in this volume.[41] His study of the eulogies penned by the rabbis Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen (Padua, 1521–1597), Abraham of Sant’Angelo (Bologna, 1530?–1584?) and Isaac de Lattes (Mantua, Venice, etc., d. c. 1570) attempts to explain the origins of the phenomenon of Jewish funeral sermons in Italy. He also concerns himself with two other “dominant themes in Italian Jewish life”: the interaction between Ashkenazic, Sephardic, and native Italian Jewish religious traditions, on the one hand, and the debate over the proper use of the kabbalah in Jewish society, on the other.[42] Horowitz tentatively argues that the eulogy emerged from a confluence of two primary forces: the limited and belated impact of “the humanist revolution in funerary oratory inaugurated by Pier Paolo Vergerio in 1393,” and the more substantial connection with Hispanic-Jewish traditions brought to Italy by Jewish immigrants from Provence or Spain.[43] The eulogy became a common phenomenon in the Italian Jewish community by the late sixteenth century among all Jews, including the Ashkenazic, and many were frequently published in sermon collections.

From close readings of several sermons delivered by the three rabbis, Horowitz considers the place of the eulogy in the social organization of the death ritual, the particular circumstances in which the sermons were delivered, and how the preacher shaped his words of the dead to fit the needs of his living audience, hoping to ingratiate himself through his well-chosen phrases. Horowitz also shows how citations from kabbalistic literature, including the recently published Zohar, were increasingly introduced into the public eulogy. As he indicates, after the controversial publication of the latter work in 1558–1560, the kabbalah lost much of its esoterism so that even intellectually conservative preachers like Katzenellenbogen had little hesitation in employing its language in their public sermons.[44]

Horowitz’s preliminary conclusions regarding a subject hardly studied at all are difficult to link with the previous essays. Horowitz does confirm the observations of Bonfil and Saperstein about the kabbalah gradually “conquering” the public sermon by the late sixteenth century.[45] His concluding suggestion regarding the “mannerist” character of Modena’s eulogy of Katzenellenbogen, so different from Katzenellenbogen’s earlier one on Moses Isserles, might be meaningfully integrated with Weinberg’s portrait of Modena as well as the other portraits in this volume, and might even suggest the possibility of a real shift in the style and substance of Jewish eulogies by the end of the sixteenth century. The subject obviously requires more investigation. This is also the case regarding the question of the origin of the Jewish eulogy in Italy. Although Horowitz minimizes the impact of the humanist model, one might ask whether the frequent use of the eulogy by such Catholic clergy as the aforementioned Panigarola during the Counter-Reformation has any bearing on the development of its Italian-Jewish counterpart in the same era.[46] It would be interesting to compare, for example, the structure of Panigarola’s eulogy for Carlo Borromeo, published in 1585 in Rome, with those discussed by Horowitz.[47] To what extent do eulogies in the two faith communities “create” heroes, models of genuine Christian or Jewish living, and to what extent do these heroic images compare with each other? Funeral orations for popes and rabbis project ideal types to be appreciated and emulated by their listeners. A comparison of the two might reveal how the ideals of each community converge and diverge.

Finally, Horowitz mentions on several occasions that the eulogy was delivered within the setting of a Jewish pious confraternity.[48] To what extent was this practice common within the Christian community? How important were the confraternities in promoting the laudatio funebris as a part of the ritual organization of death? Horowitz has shown elsewhere how Jewish confraternities assumed the prerogative of managing the rituals of dying and mourning in a fashion similar to the Christian associations.[49] Could the diffusion of the eulogy be linked with this wider phenomenon? Horowitz’s initial exploration of the Jewish eulogy invites future researchers to examine these and other questions further.

Not only this last essay but, to a great extent, all the others included in this volume merely scratch the surface of a largely untapped field. They do, however, suggest some of the possibilities for using the sermon as a means of penetrating the larger social and cultural setting of any religious community in general, and specifically of Jewish life in the ghetto age. They attempt to explore the spiritual ideals and pedagogic goals of religious leaders aspiring to uplift and educate their constituencies through their homiletic skills and strategies. They illuminate from varying perspectives the transformation of Italian Jewish culture in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the adjustment of a beleaguered but proud minority to its ghetto segregation, the openness of Jews and their surprising appropriations of the regnant cultural tastes of the surrounding society, as well as the restructuring of thought processes, ritual practice, and social organization engendered by the new urban neighborhoods. Whether intended or not, the preachers of the Italian ghetto have left behind a richly textured panorama of some of the many faces of their dynamic and creative cultural universe. In the chapters that follow we hope to provide a partial but absorbing glimpse of that universe.[50]

Notes

1. Gregory Martin, Roma Sancta (1581), ed. George B. Parks (Rome, 1969), pp. 70–71, quoted by Frederick J. McGinness in “Preaching Ideals and Practice in Counter-Reformation Rome,” Sixteenth Century Journal 11 (1980): 124.

2. Hillary D. Smith, Preaching in the Spanish Golden Age (Oxford, 1978), p. 5. She also quotes on the same page, note 1, the evocative description of Benedetto Croce in his I predicatori italiani del Seicento e il gusto spagnuolo (Naples, 1899), p. 9: “chi puo ripensare al Seicento senza rivedere in fantasia la figura del Predicatore, nerovestito come un gesuita, o biancovestito come un domenicano o col rozzo saio cappuccino, gesticolante in una chiesa barocca, innanzi a un uditorio dia fastosi abbigliamenti.” For a recent bibliography on Catholic preaching in early modern Europe, see the essay by Peter Bayley in Catholicism in Early Modern Europe: A Guide to Research, ed. John O’Malley, vol. 2 of Reformation Guides to Research (St. Louis, 1988), pp. 299–314.

3. See McGinness, p. 109. On the importance of obligatory sermons in fostering conversion to Christianity during this period, see Kenneth Stow, Catholic Thought and Papal Jewry Policy 1555–1593 (New York, 1977), chap. 10, and the earlier works he cites, especially those of Browe and Hoffmann.

4. Roma Sancta, pp. 71–72, quoted by McGinness, p. 109.

5. There exists no comprehensive treatment of this phenomenon in recent scholarly literature. The best overview of Jewish preaching in general with ample references to the early modern period is Marc Saperstein, Jewish Preaching 1200–1800: An Anthology (New Haven and London, 1989). On Jewish preaching in Eastern Europe, see Jacob Elbaum, Petiḥut ve-Histagrut: Ha-Yeẓirah ha-Ruḥanit be-Folin u-ve-Arẓot Ashkenaz be-Shalhe ha-Me’ah ha-16 (Jerusalem, 1990), pp. 223–247. On the Sephardic preacher, see Joseph Hacker, “The Sephardic Sermon in the Sixteenth Century” [Hebrew], Pe’amim 26 (1986): 108–127.

6. The scholarly literature on Italian Jewish preaching is also limited. See Robert Bonfil, Rabbis and Jewish Communities in Renaissance Italy, trans. from the Hebrew by Jonathan Chipman (Oxford, 1990), pp. 298–315; Joseph Dan, “An Inquiry into the Hebrew Homiletical Literature During the Period of the Italian Renaissance” [Hebrew], Proceedings of the Sixth World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem, 1967), division 3, pp. 105–110. Additional references are provided in the essays below.

7. See especially Stow, Catholic Thought and Papal Jewry Policy; idem, “The Burning of the Talmud in 1553 in the Light of Sixteenth-Century Catholic Attitudes Toward the Talmud,” Bibliothèque d’humanisme et Renaissance 34 (1972): 435–459; Daniel Carpi, “The Expulsion of the Jews from the Papal States during the Time of Pope Pius V and the Inquisitional Trials against the Jews of Bologna” [Hebrew], in Scritti in memoria di Enzo Sereni, ed. Daniel Carpi and Renato Spiegel (Jerusalem, 1970), pp. 145–165 (reprinted with additions in Daniel Carpi, Be-Tarbut ha-Renasans u-vein Ḥomot ha-Geto [Tel Aviv, 1989], pp. 148–167); and David Ruderman, “A Jewish Apologetic Treatise from Sixteenth-Century Bologna,” Hebrew Union College Annual 50 (1979): 253–276.

8. On Jewish life in Renaissance Italy, see the standard surveys of Cecil Roth, The Jews in the Renaissance (Philadelphia, 1959); Moses A. Shulvass, Jews in the World of the Renaissance (Leiden and Chicago, 1973); and Attilio Milano, Storia degli ebrei in Italia (Turin, 1963). See also Robert Bonfil, Rabbis and Jewish Communities; David B. Ruderman, The World of a Renaissance Jew (Cincinnati, 1981).

9. For a survey and interpretation of Jewish intellectual life in the Renaissance with extensive bibliographical citations, see David B. Ruderman, “The Italian Renaissance and Jewish Thought,” in Renaissance Humanism: Foundations and Forms, 3 vols., ed. Albert Rabil, Jr. (Philadelphia, 1988), vol. 1, pp. 382–433.

10. In addition to the references cited in note 8 above, see, for example, Léon Poliakov, Jewish Bankers and the Holy See, trans. M. L. Kochan (London, Henley, and Boston, 1977); Shlomo Simonsohn, History of the Jews in the Duchy of Mantua (Jerusalem, 1977); Umberto Cassuto, Gli ebrei a Firenze nell’età del Rinascimento (Florence, 1918; 1965); and Gaetano Cozzi, ed., Gli ebrei e Venezia secoli XIV–XVIII (Milan, 1987).

11. See Benjamin Ravid, “The Venetian Ghetto in Historical Perspective,” in The Autobiography of a Seventeenth-Century Venetian Rabbi, ed. and trans. Mark Cohen (Princeton, 1988), pp. 279–283, and also his “The Religious, Economic, and Social Background of the Establishment of the Ghetti in Venice,” in Cozzi, Gli ebrei e Venezia, pp. 211–259; Attilio Milano, Il Ghetto di Roma (Rome, 1964).

12. Ravid, “The Venetian Ghetto,” p. 283.

13. Robert Bonfil, “Change in the Cultural Patterns of a Jewish Society in Crisis,” Jewish History 3 (1988): 11–33. (Reprinted in David B. Ruderman, ed., Essential Papers on Jewish Culture in Renaissance and Baroque Italy [New York, 1992].) See also his “Cultura e mistica a Venezia nel Cinquecento,” in Cozzi, Gli ebrei e Venezia, pp. 496–506.

14. Bonfil, “Change in Cultural Patterns,” p. 13.

15. Ibid., p. 12.

16. Ibid., and in general, the entire essay.

17. See Bonfil’s essay and Jefim Schirmann, “Theater and Music in Italian Jewish Quarters XVI–XVIII Centuries” [Hebrew], Zion 29 (1964): 61–111; and his “The Hebrew Drama in the XVIIIth Century” [Hebrew], Moznayim 4 (1938): 624–635. Both reprinted in Schirmann, Studies in the History of Hebrew Poetry and Drama, 2 vols. (Jerusalem, 1977), vol. 1, pp. 25–38; 44–94.

18. See Dan Harrán, “Tradition and Innovation in Jewish Music of the Later Renaissance,” The Journal of Musicology 7 (1989): 107–130, reprinted in Ruderman, Essential Papers; Israel Adler, “The Rise of Art Music in the Italian Ghetto,” in Jewish Medieval and Renaissance Studies, ed. Alexander Altmann (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), pp. 321–364.

19. See Dan Pagis, “Baroque Trends in Italian Hebrew Poetry as Reflected in an Unknown Genre,” Italia Judaica (Rome, 1986), vol. 2, pp. 263–277 (reprinted in Ruderman, Essential Papers); and Pagis, Al Sod Ḥatum (Jerusalem, 1986).

20. Shalom Sabar, “The Use and Meaning of Christian Motifs in Illustrations of Jewish Marriage Contracts in Italy,” Journal of Jewish Art 10 (1984): 46–63.

21. See Bonfil, p. 21, and Yosef Melkman, “Moses Zacuto’s Play Yesod Olam” [Hebrew], Sefunot 10 (1966): 299–333.

22. Bonfil, pp. 16–18.

23. Ibid., p. 18 and throughout. For a discussion of the meaning of the Renaissance when applied to Jewish culture, see Ruderman, “The Italian Renaissance,” cited in note 9 above. On previous uses of the term “baroque” in characterizing Jewish cultural history of the ghetto era, see Giuseppe Sermonetta, “Aspetti del pensiero moderno nell’ebraismo tra Rinascimento e età barocca,” in Italia Judaica, vol. 2, pp. 17–35; David B. Ruderman, A Valley of Vision: The Heavenly Journey of Abraham ben Hananiah Yagel (Philadelphia, 1990), pp. 65–68. On the notion of “Baroque” in general, see, for example, Frank J. Warnke, Versions of Baroque: European Literature in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven and London, 1963), and the additional references cited in Ruderman, p. 65, n. 192.

The participants in this volume, as the reader will notice, employ the terms “Renaissance,” “post-Renaissance,” “Counter-Renaissance,” and “baroque” in describing Jewish cultural development in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in less than uniform ways. While I have attempted to clarify (and even to reconcile tentatively) their usages in this introduction, I am well aware that a lack of uniformity still remains. This situation seems unavoidable, however, given the present state of research and the differences in approach among the contributors and other scholars of this era. For further clarification of this issue of periodizing the “Renaissance” and “baroque” with respect to Jewish culture, see Ruderman, Essential Papers, especially the introduction, and compare Hava Tirosh-Rothschild, “Jewish Culture in Renaissance Italy: A Methodological Survey,” Italia 9 (1990): 63–96

24. In this regard, consider Moshe Idel’s essay in this volume.

25. See below, pp. 22–40.

26. This situation is fully discussed in Simonsohn, Mantua. Idel’s essay is found below, pp. 41–66. In designating Moscato the oldest of the preachers discussed below, I exclude those discussed collectively by Horowitz in his essay on eulogies. Given its special subject matter, I have treated this essay separately from the rest.

27. See, for example, his “The Magical and Neoplatonic Interpretations of the Kabbalah in the Renaissance,” in Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, ed. Bernard Cooperman (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), pp. 186–242, and his “Major Currents in Italian Kabbalah Between 1560–1660,” Italia Judaica, vol. 2, pp. 143–162. Both essays have been reprinted in Ruderman, Essential Papers.

28. See below, p. 57.

29. See below, pp. 67–88.

30. See below, pp. 89–104.

31. For additional references, see Ruderman below, pp. 101–102, n. 1.

32. See Michel Foucault, “The Prose of the World,” in The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences (New York, 1970), pp. 17–50, first published as Les mots et les choses (Paris, 1966). This type of thinking characterized that of Moscato’s Jewish contemporary, Abraham Yagel. On him, see David B. Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science: The Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth-Century Jewish Physician (Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1988), especially chap. 4.

33. See Hiram Haydn, The Counter-Renaissance (New York, 1950), and compare Moshe Idel, “Differing Conceptions of Kabbalah in the Early 17th Century,” in Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century, ed. Isadore Twersky and Bernard Septimus (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1987), pp. 137–200, especially p. 174.

34. See below, pp. 105–128. For additional references to Modena’s life and thought, see the references in Weinberg’s essay below, especially the work of Howard Adelman.

35. See below, p. 110.

36. See below, p. 122.

37. See the reference to his essay in note 34 above.

38. Ibid.

39. On this, see Ruderman, “The Language of Science as the Language of Faith,” listed in my essay below, pp. 101–102, n. 1.

40. John W. O’Malley, Praise and Blame in Renaissance Rome: Rhetoric, Doctrine, and Reform in the Sacred Orators of the Papal Court c. 1450–1521 (Durham, N.C., 1979).

41. See below, pp. 129–162.

42. See below, p. 131.

43. See below, pp. 131–135.

44. See below, p. 137.

45. See Bonfil, “Change in the Cultural Patterns,” p. 12, and in his book, Rabbis and Jewish Communities, and see Saperstein below, p. 26.

46. On the Catholic eulogy during the Counter-Reformation, see McGinness, “Preaching Ideals and Practice,” p. 125, and the bibliography cited there, especially Verdun L. Saulnier, “L’oraison funèbre au XVIe siècle,” Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 10 (1948): 124–157.

47. See Oratione Del. R. P. Francesco Panigarola…In morte, e sopra il corpo Dell’ Ill. mo Carlo Borromeo (Rome, 1585).

48. See below, pp. 135–137, 138, 141, 144.

49. Elliott Horowitz, “Jewish Confraternities in Seventeenth-Century Verona: A Study in the Social History of Piety,” Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1982, chap. 3.

50. My thanks to Benjamin Ravid and Marc Saperstein for reading a draft of this introduction and offering me their thoughtful comments.

2. Italian Jewish Preaching: An Overview

Marc Saperstein

On a day between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, probably in the year 1593, Rabbi Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen of Padua delivered a eulogy for Judah Moscato. As befits the time of year, he began with a discussion of repentance, proceeding to argue that one of the primary functions of the eulogy was to inspire the listeners to repent. He went on to discuss the qualities of a great scholar: perfection of intellect and behavior and the capacity to communicate wisdom to others, both by capturing the listeners’ attention with appealing homiletical material and by teaching them the laws they must observe, which are essential for the true felicity of the soul, even though most contemporary congregations do not enjoy listening to the dry halakhic content. At this point the printed text of his sermon reads, “Here I began to recount the praises of the deceased, and to show how these four qualities were present in him to perfection, the conclusion being that we should become inspired by his eulogy and allow the tears to flow for him, look into our deeds, and return to the Lord.”[1]

This passage encapsulates for me something of the challenge and frustration of studying Italian Jewish preaching, and to some extent Jewish preaching in general. Here is a leading Italian rabbi eulogizing per- haps the best-known Jewish preacher of his century. We are given some important statements about the function of the eulogy, the proper content and structure of the sermon, the expectations and taste of the average listener. Then we come to the climactic point, where the preacher turns to Moscato himself. We expect an encomium of the scholarship and piety of Moscato and, what is more important for our purposes, a characterization of his preaching, an indication of his contemporary reputation, an evaluation from a colleague who apparently had a rather different homiletical style. None of this is forthcoming. This climactic section of the eulogy is deemed unworthy of being recorded, presumably because of its specificity and ephemeral character. What for us (and perhaps for at least some of the listeners) is the most important content has been lost forever.

Title page from Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen’s Shneim-Asar Derashot (Venice, 1594). Courtesy of the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

In Kabbalah: New Perspectives, Moshe Idel argues that even after the life work of Gershom Scholem and two generations of his disciples, the literature of Jewish mysticism is by no means fully charted: important schools may never have committed their doctrines to writing, significant works have been lost, certain texts may have arbitrarily been given undue emphasis at the expense of others no less important, and there is as yet no comprehensive bibliographic survey of the literature that does exist.[2] How much more is this true for Jewish sermon literature, which has had no Gershom Scholem to chart the way. The history of Jewish preaching in general, and that of Italy in particular, may best be envisioned as a vast jigsaw puzzle from which ninety percent of the pieces are missing and seventy-five percent of those that remain lie in a heap on the floor—and for which we have no model picture to tell us what the design should look like. Generalizations about trends or characteristics of the homiletical tradition are like speculations about the design of the puzzle based on individual pieces or small clusters that happen to fit together. And without a clear map of the conventions and continuities of the tradition, all assertions about the novelty or even the significance of a particular preacher or sermon are likely to be precarious and unfounded.

The magnitude of what we lack is astonishing. Leon Modena’s Autobiography informs us that he preached at three or four places each Sabbath over a period of more than twenty years, and that he had in his possession more than four hundred sermons. Yet only twenty-one from the early part of his career were published, and the rest have apparently been lost.[3] When we think of the pinnacle of Italian Jewish preaching, Moscato is probably the name that comes first to mind. Yet a contemporary of Moscato’s nominated David Provençal, the author of the famous appeal for the founding of a Jewish university, as “the greatest of the Italian preachers in our time.” Like most of his other works, Provençal’s sermons (if written at all) are no longer extant, leaving us no basis for evaluating the claim.[4] It does, however, give us pause to consider that our standard canon of important Italian Jewish preachers may be highly arbitrary.

The record before the sixteenth century is almost entirely blank: one manuscript by a mid-fifteenth-century preacher, Moses ben Joab of Florence, described and published in part by Umberto Cassuto more than eighty years ago.[5] We have no known extant sermon reacting to the popular anti-Jewish preaching of such Franciscan friars as Bernardino da Siena, John Capistrano, and Bernardino da Feltre; or to the notorious ritual murder charge surrounding Simon of Trent; or to the arrival on Italian soil of refugees from the Iberian peninsula; or to the exploits in Italy of the charismatic David Reubeni, including an audience with Pope Clement VII; or to the burning of the magnificently printed volumes of the Talmud in Rome and Venice; or to the arrest, trial and execution of former Portuguese New Christians who had returned to Judaism in Ancona and the attempted boycott of that port; or to the papal bull Cum nimis absurdum and the establishment of the Ghetto in Rome.

There can be little question that Jewish preachers alluded to, discussed, and interpreted these events in their sermons. Nor can it be doubted that the records of these discussions would provide us with precious insight into the strategies of contemporary Jews for accommodating major historical upheavals to their tradition and, conversely, for reinterpreting their tradition in the light of contemporary events. But it apparently did not occur to these preachers that readers removed in space and time from their own congregations would be interested in learning about events in the past, and they therefore had little motivation to write what they said in a permanent form.[6]

Much of the material that exists has yet to be studied. Isaac Ḥayyim Cantarini of Padua does not appear in any of the lists of great Italian preachers known to me. Yet he may belong in such a list; no one has ever taken a serious look at his homiletical legacy. He left behind what appears to be the largest corpus of Italian Jewish sermons in existence. The Sefer Zikkaron of Padua gives the number as “more than a thousand,” and a substantial percentage of these are to be found in six large volumes of the Kaufmann manuscript collection in Budapest (Hebrew MSS 314–319), each one of them devoted to the sermons for a complete year between 1673 and 1682; there may be more such volumes as well. In many cases there are two sermons for each parashah, one delivered in the morning, the other at the Minḥah service. The sermons are written in Italian, in Latin letters, with Hebrew quotations interspersed.[7]

I once thought of looking through the volume containing the sermons for 1676–1677 to see if I could find any reaction to the news of the death of Shabbetai Ẓevi, but I soon realized the enormity of the task: that volume alone runs to 477 pages, and there is no guarantee that the preacher would have referred to the event explicitly as soon as the news reached his community. Needless to say, for someone interested in intellectual or social history during this period, not to mention the history of Jewish preaching or the biography of a many-talented man, these manuscripts may well repay careful study with rich dividends.

The first desideratum is therefore bibliographical: to compile a complete list of all known manuscripts of Italian sermons—let us say through the seventeenth century—to complement the printed works identified by Leopold Zunz and others. Then we need a data base that would include a separate entry for each sermon, including the place and approximate date of delivery, the genre (Sabbath or holiday sermon, eulogy, occasional, etc.), the main biblical verses and rabbinic statements discussed, the central subject or thesis, and any historical connection with an individual or an event. This would at least spread out all the known pieces of the puzzle on the table before us and facilitate the process of putting them together.

In addition to actual sermons, related genres need to be considered. Rabbi Henry Sosland has given us a fine edition of Jacob Ẓahalon’s Or ha-Darshanim, a manual for preachers from the third quarter of the seventeenth century.[8] But the “Tena’ei ha-Darshan,” written by Moses ben Samuel ibn Basa of Blanes, is no less worthy of detailed analysis.[9] Nor should the various preaching aids be overlooked: works intended to make the preacher’s task easier by collecting quotations on various topics, alphabetically arranged, analogous to a host of such works written by Christian contemporaries.[10]

Once the material has been charted, we can define the questions that need to be addressed. Perhaps the most obvious deal with the sermons as a reflection of Italian Jewish culture, as documents in Jewish intellectual history. To what extent can we find in the sermons evidence for the continued vitality of philosophical modes of thought, for the popularization of kabbalistic doctrines, for the influence of classical motifs or contemporary Christian writings? As these are the questions that will be addressed most thoroughly in the following presentations, I will not pursue the theme further here.

What can we say about the native Italian homiletical tradition, and the impact of the Spanish tradition in the wake of the Sephardic immigration? We can outline the broad contours of the Spanish homiletical tradition as it crystallized in the late fifteenth century, and trace its continuity within the Ottoman Empire.[11] The manuscript sermons of Joseph ben Ḥayyim of Benevento, dating from 1515 until the 1530s, provide an example of preaching on Italian soil very much in the Spanish mold: a verse from the parashah and a passage of aggadah (often from the Zohar) as the basic building blocks, an introduction including a stylized asking of permission (reshut) from God, the Torah, and the congregation, followed by a structured investigation of a conceptual problem, sometimes accompanied by an identification of difficulties (sefekot) in the parashah.[12] But the paucity of Italian material from the fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth century makes it very difficult to delineate the process by which Spanish-Jewish preaching influenced home-grown models.

What is the relationship between Jewish and Christian preaching in Italy? I am referring not to a rehashing of the debate about the influence of Renaissance rhetorical theory,[13] but to an assessment of the more immediate impact of published Christian sermons and actual Christian preachers. Did the notorious conversionist sermons influence Jewish preaching style? Did conversionist preachers learn from Jewish practitioners the most effective ways to move their audiences?[14] Nor should we forget that Italian Jews did not always need to be coerced to listen to Christian preachers, as we learn from a passing reference to “educated Jews” (Judei periti) at a sermon delivered by Egidio da Viterbo in Siena on November 11, 1511.[15]

That Christians attended the sermons of Leon Modena is known to every reader of his Autobiography;[16] not as widely known is the passage in which he refers to his own attendance at the sermon of a Christian preacher,[17] and the fact that he owned at least one volume of Savonarola’s sermons and an Italian treatise on “The Way to Compose a Sermon.”[18] His letter to Samuel Archivolti describes the sermons in Midbar Yehudah as a blending of Christian and Jewish homiletics, and he uses the Italian terms prologhino and epiloghino to characterize the first and last sections of his discourses.[19] All of this bespeaks an openness to what was happening in the pulpits of nearby churches. Extremely important work has been done during the past two decades on various aspects of the history of Italian Christian preaching;[20] the task of integrating this with the Jewish material remains to be accomplished.

Another aspect of this subject relates to the use of Italian literature by Jewish preachers. Extravagant claims have been made; an Encyclopaedia Judaica article asserts that “Like Petrarch, Dante was widely quoted by Italian rabbis of the Renaissance in their sermons.”[21] I do not know what evidence could support such a statement. The written texts contain few examples of Jewish preachers using contemporary Italian literature, and there is no reason to assume that such references would be eliminated in the writing, or that those who quoted Italian authors would be predisposed not to write their sermons. Nevertheless, those examples which do exist are instructive. Joseph Dan has discussed Moscato’s citation of Pico della Mirandola which, though incidental to the preacher’s main point, shows that there was apparently nothing extraordinary about using even a Christological interpretation for one’s own homiletical purpose.[22]

More impressive are stories used by Leon Modena. The allegory he incorporates into a sermon on repentance, in which Good and Evil exchange garments so that everyone now honors Evil and spurns Good, is presented as one he “heard,” probably from a Christian or from a Jew conversant with Christian literature. Another story, used in the eulogy for a well-known rabbinic scholar, tells of a young man who tours the world to discover whether he is truly alive or dead. The answer he receives from a monk is confirmed in a dramatic dialogue with the spirit of a corpse in the cemetery. Modena attributes this story explicitly to a “non-Jewish book.” While I have still not succeeded in identifying the direct source of the story, it certainly reflects the late medieval and Renaissance preoccupation with death and dying that produced not only the various expressions of the danse macabre motif but a host of treatises on good living and good dying, including dialogues involving a non-threatening personification of Death.[23]

What do we know about the training of preachers? For no other country is there such ample evidence for the cultivation of homiletics as an honorable discipline in the paideia as there is for Italian Jewry. The kinds of evidence range from the exemplary sermon of Abraham Farissol dating from the early sixteenth century to the letters of Elijah ben Solomon ha-Levi de Veali almost three hundred years later.[24] There seems to have been a special emphasis on students accompanying their teacher to listen to sermons delivered during religious services, especially on major preaching occasions. In addition, preaching was actually taught in the schools.[25] Public speaking and the delivery of sermons was to be part of the curriculum in David Provençal’s proposed Jewish college in Mantua.[26] The preaching exercises in which Modena participated when he was no older than ten do not seem to have been unusual.[27] The delivery of a sermon by a precocious child may well have had the effect that the playing of a concerto by a young prodigy would have had in the age of Mozart. But the actual mechanism for instruction—whether printed collections of sermons were studied and sermons by noted preachers were critiqued, what written guidelines for the preparation of sermons were used in the schools—remains to be fully investigated.

A work like Medabber Tahapukhot by Leon Modena’s grandson Isaac provides dramatic evidence of the tumultuous politics of the pulpit. Indeed, the ways in which the selection of preachers for various occasions could reveal a hierarchy of prestige, unleashing bitter quarrels, is one of the central subjects of the book.[28] Conflicts over the limits of acceptable public discourse—what content could and could not properly be addressed from the pulpit—were part of the same cultural milieu that produced the battles over the printing of the Zohar and the publication of de’ Rossi’s Me’or Einayim.[29] Sometimes these issues were directed to legal authorities who issued formal responsa, but in addition to evoking decisions from the scholarly elite, they reflect problems in the sensibilities and tastes of the listeners in the pews. A full range of such nonsermonic texts is necessary for an adequate reconstruction of the historical dynamic of Italian Jewish preaching.

A final set of questions relates to the writing and printing of sermon collections. Although sermons were undoubtedly delivered in the vernacular throughout the Middle Ages, Italy seems to have produced the first texts of Jewish sermons actually written in a European vernacular language.[30] Why did some Jewish preachers begin to write in Italian in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries? What does the transition from Hebrew to Italian in Hebrew characters (Dato) to Italian in Latin characters (Cantarini) reveal about contemporary Jewish culture? Despite the new linguistic variety in the manuscripts, however, printed collections remained in Hebrew. The number of such books published in Venice between 1585 and 1615, by both Italian and Ottoman preachers, is an astounding indication of public demand for this kind of literature. Modena decided to prepare a selection of his sermons for print in the hope that the proceeds would help ease his financial pressures, although in this, as in so many other pecuniary matters, he was apparently disappointed.[31]

In addition to the economics of sermon publishing, the format seems worthy of attention. While most collections of Spanish and Ottoman sermons are arranged in accordance with the weekly parashah, most Italian collections are not. We have relatively few ordinary Sabbath sermons, particularly in print; most of them are for special Sabbaths, holidays, occasions in the life cycle or the life of the community. Yet there is abundant evidence that weekly preaching on the parashah was the norm throughout Italy. Could there have been a conscious avoidance of the Sephardic format in these published collections? We have no answer as yet.

I turn now to a more detailed discussion of certain aspects of Italian preaching. Among other roles, the preacher appears as a guardian of moral and religious standards, and therefore as a critic of the failings of his listeners. Frequently this was just the kind of material the preacher would omit when writing his words for publication, assuming that readers in distant cities would have little interest in the local issues he had addressed.[32] But some of this social criticism has been preserved. If we are careful to distinguish generalized complaints, the commonplaces of the genre of rebuke that recur in almost every generation, from attacks that target a specific, concrete abuse, we may find clues to the stress lines within Jewish society, clues that become more persuasive when the sermon material is integrated with the contemporary responsa literature.[33]

The proper assessment of the sermonic rebuke is not always obvious. I am not quite certain what to make of the accusation, made by both Samuel Katzenellenbogen and Jacob di Alba, that among those who leave the synagogue after the Tefillah and who therefore miss the sermon are congregants who hurry to return to their business affairs.[34] Can they be talking about Jews who engage in work on the Sabbath after attending only part of the Saturday morning service? This would be a violation so serious that one wonders why any rabbi would focus on the much more trivial offense of missing the sermon or insulting the preacher.

Is this particular rebuke then merely a rhetorical device used to discredit those who walk out early by suggesting to the remaining congregation that the exiters might be going to work? If so it could not be used to prove that serious Sabbath violation was actually occurring, but only that the possibility of such violation was plausible enough for the listeners not to dismiss the suggestion as absurd. Or could the entire passage be referring not to the Sabbath but to the weekday morning service? If this is the case, it would be evidence of a very different dynamic: the cultivation of the practice of a daily “devar Torah,” and the resistance on the part of Jews who were committed enough to attend the service, but resented the homiletical accoutrement as an imposition on their time. As with the Moscato eulogy, Katzenellenbogen leads us to the brink of something rather important but fails to give us quite enough to use it with confidence.