1

The Mask as the God

God is day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, satiety and want. But he undergoes transformations, just as [a neutral base], when it is mixed with a fragrance, is named according to the particular savor [introduced].

—Heraclitus[1]

God, for Heraclitus, was the name for the spiritual force undergirding reality and disclosing itself in the wide variety of earthly states that were nothing more than its fleeting manifestations. The peoples of Mesoamerica held a similar view; for them, the vitality of the natural world had its source in the world of the spirit, the domain of the mysterious life-force. This force was the ground of being, the animating and ordering principle that explained every aspect of earthly life. Originating in the shamanistic heritage of Mesoamerican religion, this basic belief led to a consistent emphasis on inner/outer, spirit/matter dichotomies as a means of explaining the order apparent in nature, and for that reason, Mesoamerican spiritual thought betrays a fascination with "inner" things: the heart of man symbolized the life-force within him and was sacrificially offered to the gods, the "heart" of the earth reached through caves and through the temples that were artificial caves, and the "heart" of the heavens reached by ascending mountains or man-made pyramids. This fundamental inner/outer paradigm, then, placed "god," or the creative life-force, at the core of the cosmos and saw the natural world as its "mask."

But in the most profound sense, the mask reveals rather than disguises; through "reading" the symbolic features of the "mask" of nature, man could perceive the relationship of those features to the creative life-force at the heart of the cosmos. And nowhere was this metaphorical function of the mask more significant than in the construction of the multiplicity of symbolic supernatural entities, each carefully identified by a characteristic mask and costume, which the conquering Spaniards called gods. These were not, however, independent deities as the Spaniards thought but rather the symbolic "names" for momentary manifestations of that underlying spiritual force showing itself in terms of a particular life process, and they existed in the same way as the forces and states they represented. Rain, for example, exists eternally only in the sense that it is a recurring part of the process through which life continues; in another sense, however, rain does not exist when it is not raining. Thus, the "gods"' moments of existence would recur periodically as the eternal spiritual force regularly "unfolded" itself into the contingent world of nature according to the laws of the cycles that had their source in the mysterious order of the creative life-force. Metaphorically, then, the life-force functioned by putting on and taking off the various "masks" through which it worked in the world of nature. The "gods" were direct expressions of the spiritual force clothed in finery drawn from the world of nature and thus could be seen as mediating between the worlds of spirit and matter.

Edmund Leach has designed a structural model, which he does not apply to Mesoamerica, that explains such mediation:

Religious belief is everywhere tied in with the discrimination between living and dead. Logically, life is simply the binary antithesis of death;the two concepts are the opposite sides of the same penny; we cannot have either without the other. But religion always tries to separate the two. To do this it creates a hypothetical "other world" which is the antithesis of "this world. " In this world life and death are inseparable; in the other world they are separate. This

world is inhabited by imperfect mortal men; the other world is inhabited by immortal non-men (gods). The category god is thus constructed as the binary antithesis of man. But this is inconvenient. A remote god in another world may be logically sensible, but it is emotionally unsatisfying. To be useful, gods must be near at hand, so religion sets about reconstructing a continuum between this world and the other world. But note how it is done. The gap between the two logically distinct categories, this world/other world, is filled in with tabooed ambiguity. The gap is bridged by supernatural beings of a highly ambiguous kind—incarnate deities, virgin mothers, supernatural monsters which are half man/half beast. These marginal, ambiguous creatures are specifically credited with the power of mediating between gods and men. They are the objects of the most intense taboos, more sacred than the gods themselves. In an objective sense, as distinct from theoretical theology, it is the Virgin Mary, human mother of God, who is the principal object of devotion in the Catholic church .[2]

Suggesting all of the elements contained so economically in the metaphor of the mask, this model describes the Mesoamerican method of mediation marvelously, especially since it focuses on the binary discrimination between life and death, an opposition at the heart of Mesoamerican spiritual thought. For Mesoamerica, the world of the spirit, mysterious and inaccessible, was synonymous with the life-force, while the world of nature was inextricably involved with death. Permanence was found in the other world; this world offered only change culminating in death, which permitted entrance to the other, an entrance characterized as deification in the case of great leaders and culture heroes. This fundamental distinction between life and death, spirit and matter, permanence and flux threads its way through Mesoamerican thought from the earliest times to the time of the Conquest: at the beginning of the development of Mesoamerican spirituality, that distinction was basic to shamanism with the shaman as the mediator between the worlds, and in the last phase of autonomous indigenous thought, that same distinction was at the heart of a religious and philosophical genre of Aztec poetry. One Aztec poet addressing this theme wrote,

Let us consider things as lent to us, O friends;

only in passing are we here on earth;

tomorrow or the day after,

as Your heart desires, Giver of Life,

we shall go, my friends, to His home.

The conclusion was inescapable that "beyond is the place where one lives."[3] Permanence was to be found in the world of the spirit; this world offered flux ending in death.

But as Leach points out, the gap between the two worlds must be bridged to explain the existence of life and spirit, even though transitory, in this one and to enable man to participate in a ritual relationship with the source of the spirit that animates him. These two points of contact are made in theological thought and in ritual; in both cases, the mode of contact between the two in Mesoamerica is aptly characterized in Leach's analysis, and in both cases, the mask was of central importance to this mediation. Theologically, Mesoamerican thought posited a creator god devoid of characteristics except that of creativity itself located in the "center" of that other, spiritual world. This god, Ometeotl among the Aztecs and Hunab Ku among the Maya, for example, was "a remote god in another world," rarely represented in figural form and playing little part in ritual.

The characteristic Mesoamerican metaphor of "unfolding" through which the creative force put on a variety of "masks" denoting the specific roles it played in the world resulted in the elaborate system of "gods" who could mediate between the creativity of an Ometeotl or Hunab Ku and the created world of man. That transformational unfolding allowed the original creative force to produce "gods" in sets of four, each associated with a particular relationship between nature and spirit, and each of these often further unfolded into a series of aspects. In the terms of Aztec religion, the variant of Mesoamerican religious thought about which we have the most specific information, those four gods, each an aspect of the quadripartite Tezcatlipoca, were the red Tezcatlipoca who was Xipe or Camaxtli-Mixcóatl, the black Tezcatlipoca commonly known simply as Tezcatlipoca, the blue Tezcatlipoca who was identified as Huitzilopochtli, and Quetzalcóatl who was probably a white Tezcatlipoca. Each was characterized by facial painting and costume that served as a "mask" covering and giving a specific identity to the underlying creative force of Ometeotl. Because Xipe and the Tezcatlipoca/Quetzalcóatl duality are far too complex to consider here, we will use Huitzilopochtli and his related manifestations to illustrate briefly the use of the "mask" of costume to define spiritual entities in the process of reconstructing "a continuum between this world and the other world."

Huitzilopochtli (literally, Hummingbird on the Left) is an especially good symbol of mediation since he had particularly strong ties to each of these two worlds. Both as one of the four Tezcatlipocas and as the one associated with the blue sky of the day and thus with the sun, which throughout Mesoamerican history was consistently seen as the source of and metaphor for life, he had a strong link to the creative power of Ometeotl. However, he was very much involved in earthly affairs. As the tutelary god of the Aztecs, he led them on the

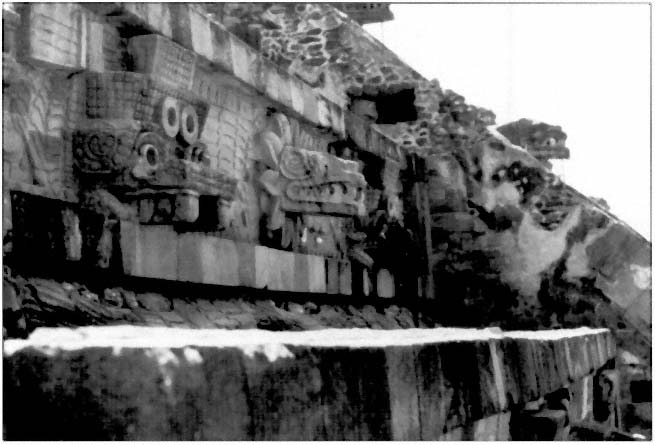

mythical journey from their humble beginnings in Aztlán to the heights of imperial splendor at Tenochtitlán. Like the other gods, Huitzilopochtli was always depicted in the codices (pl. 1) and described in the chronicles in terms of his "mask," his characteristic facial painting, costume, and accoutrements. These identifying items were not selected arbitrarily; they symbolized his roles in Aztec myth, thought, and society by pointing clearly to his links with Ometeotl, on the one hand, and the Aztec state, on the other.

The most obvious features of his costume are those that identified him with his namesake the hummingbird, such as, in the codices, a device worn on his back or, according to Diego Durán,

a rich headdress in the shape of a bird's beak. . . . The beak which supported the headdress of the god was of brilliant gold wrought in imitation of the [hummingbird]. . . . The feathers of the headdress came from green birds. [The idol] wore a green mantle and over this mantle, hanging from the neck, an apron or covering made of rich green feathers, adorned with gold .[4]

Durán relates these visual references to rebirth and the seasonal cycle paralleling the emphasis in the mythic account of Huitzilopochtli's birth and defense of his mother, Coatlicue, from the assault of Coyolxauhqui and her followers, which also suggested the cyclical nature of the sun's daily rebirth, its creating the "life" of day after the "death" of night. This emphasis on rebirth fit well with the Mexican belief, recorded by Bernardino de Sahagún, that the hummingbird, Huitzilopochtli's nahualli, the animal into which he could transform himself and who shared his identity, "died in the dry season, attached itself by its bill to the bark of a tree, where it hung until the beginning of the rainy season when it came to life once more."[5]

The concept of rebirth, of course, relates directly to the creativity of Ometeotl, and the association with Ometeotl represented in myth by Huitzilopochtli's unfolding from the creator god as one of the four Tezcatlipocas was suggested visually by facial painting; the ultimate unity of the four Tezcatlipocas can be seen in the fact that the face of each of them is striped with horizontal bands. In the case of Huitzilopochtli, the bands are alternately blue and yellow, representing the daytime sky and the light of the sun, thereby suggesting again the creativity of Ometeotl. According to the sixteenth-century Relación de Texcoco, this facial painting was represented in sculpture, none of which survives, by precious turquoise and gold mosaic, after the fashion, no doubt, of the extant mosaic masks. This sky/sun association was also suggested by his blue sandals and gold bracelets as well as by his being "seated in a blue bower or adorned with blue cotinga-feather earplugs."[6]

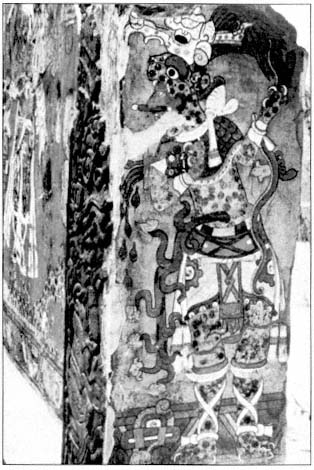

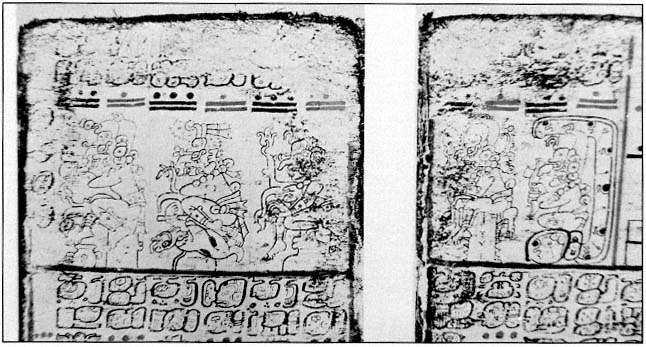

Pl. 1.

Huitzilopochtli, from the Codex Borbonicus (reproduced with the

permission of Siglo Veintiuno Editores, S.A., México).

But these links to Ometeotl and the creative power of the life-force relate only to one side of the dichotomy bridged by Huitzilopochtli. His blue staff was central to the imagery delineating his symbolic function as war god and leader of the Aztec state, for that staff represented the fire serpent, xiuhcóatl , with which he "pierced Coyolxauhqui, and then quickly struck off her head" in the myth of his birth. "His shield [named] teueuelli , and his darts, and his dart thrower, all blue, named xiuatlatl ,"[7] derived from the same myth and suggested again his association with war. His shield was adorned with a quincunx composed of five tufts of eagle feathers. From it "hung yellow feathers as a sort of border; from the top of the shield, a golden banner. Extending from the handle were four arrows. These were the insignia sent from heaven to the Mexicas, and it was through these symbols that these valorous people won great victories in their ancient wars."[8] Thus the items he carried suggested his function as deified leader of the Aztec state, his "preeminently warlike associations [that] were conveyed by such metaphors as 'the eagle' or 'the bird of darts."'

And these associations, in turn, are related to his identity as the hummingbird through which he is linked to various other birds, "the blue Heron bird, the lucid Macaw, and the precious Heron"[9] but primarily the high-flying, powerful eagle, the bird most closely related to the sun and to warriors, Huitzilopochtli's dual role in the myth of his birth. And his identification as an eagle also suggested the other myth in which he figured prominently, the myth of the birth of the Aztec state. That myth recorded his telling the wandering Aztecs,

In truth I will lead thee to the place to which thou art to go; I will appear in the guise of a white eagle . . . go then, watching me only, and when I arrive there, I will alight . . . so presently make my temple, my home, my bed of

grass, there where I was lifted up to fly, and there the people shall make their home.[10]

The myth was of great importance in symbolically characterizing the Aztec state. In following the eagle, the Aztecs were following the sun, which gave their history the aura of a divine mission; they were not only the people who followed the eagle but the People of the Sun. In their wandering movement from north to south, they were not invading new territory to which they had no claim but returning to Huitzilopochtli's home, where he "was lifted up to fly." He was, after all, Hummingbird on the Left, and Left meant South to a people who determined directions by facing in the direction of the path of the sun. Thus, they were returning to the birthplace of Huitzilopochtli in something akin both to a seasonal (and thus cyclical) migration and a return to their ancestral lands. In following the sun, they were following the eagle, and the eagle symbolized the warrior aspect of Huitzilopochtli shown in his fearlessly routing his sister and her followers in their assault on Coatlicue, their mother. As the myth leads one to suspect, there is some evidence that Huitzilopochtli was not only linked to the eagle and the sun but was intimately connected with an early or legendary leader of the Aztecs, a leader deified at his death in the time-honored Mesoamerican fashion. Such a leader might well have been associated with Huitzilopochtli since, as Sahagún suggests, the souls of dead warriors are "metamorphosed into various kinds of birds of rich plumage and brilliant color which go about drawing the sweet from the flowers of the sky, as do the hummingbirds upon earth."[11] For all these reasons, expressed in myth but functioning to support the practices of the Aztec state, Huitzilopochtli was "the divine embodiment of the ideal Mexica warrior-leader: young, valiant, all-triumphant,"[12] an "embodiment" symbolized by his "mask" of facial painting, costume, and accoutrements.

Thus, for Aztec Mexico, Huitzilopochtli simultaneously symbolized the creative power of the world of the spirit and the imperial power of the Aztec state. For that reason, he was seen as a manifestation of Ometeotl, as "the greatest divinity of all, . . . the only one called Lord of Created Things and The Almighty."[13] That exalted status, celebrated by the details of his costume signifying the link between the creative life-force and the Aztec state, was also revealed by the sacrificial ritual performed periodically in the temple of Huitzilopochtli atop the pyramid of the Templo Mayor in the Aztec capital. In mythic terms, such a sacrifice of the hearts and blood of men was necessary to provide the nourishment necessary to ensure the daily rebirth of the sun. The mythic equation suggested that the sun's creating life for man must be reciprocated by man's providing life for the sun. "Human sacrifice was an alchemy by which life was made out of death,"[14] and as the People of the Sun, the Aztecs had a divinely imposed responsibility to perform that alchemy. As modern scholars have pointed out, however, that duty coincided nicely with the militaristic nature of the Aztec state; warfare could be seen as providing captives for the divinely required sacrifices while it also extended the dominions under Aztec sway and reinforced Aztec power. Human sacrifice took on its all-important role in Aztec society precisely because it met both mythic and political needs. That Huitzilopochtli was the primary focus of this sacrificial ritual demonstrates his importance to the Aztecs in the symbolic mediation between the worlds of spirit and matter; he was for them a particular way of understanding natural facts in spiritual terms and is thus a good example for us of the specific way in which Mesoamerican spiritual thought bridged the gap between spirit and nature.

Huitzilopochtli demonstrates, just as Leach suggests, that "the gap between the two logically distinct categories, this world/other world," is bridged by beings who have, so to speak, one foot in each of the worlds. In their Mesoamerican incarnations they are composite beings who, on examination, generally turn out to be human beings wearing masks and costumes comprised of the features of a variety of natural beings combined in unnatural, that is, "monstrous," ways. Thus are created the "supernatural monsters" to which Leach refers. This disguise or "mask" is the visual representation of the logical construct by which the particular continuum between the two worlds, which is what each god becomes, is reconstructed. Significantly, this "reconstruction" takes elements of living beings from the created world of nature and uses those elements in a mythic process of creation that imitates the original work of the creator god. These elements are combined to form the mask, costume, and ornamentation of the god, then placed on a human being who thus represents the life-force underlying and expressing itself in the set of specific items that form its identity. The god is always identified by a mask or characteristic facial painting, a specific costume, and the objects he carries. The visual image created by combining these things is essentially a myth.

Just as what is commonly called a myth—a narrative recounting the symbolic actions of a god—is made up of specific items—actions and events—arranged in a particular order and meant to be understood symbolically as an expression of the identity and function of the god, so the Mesoamerican visual statement uses specific items—features, masks, attire—combined in a plastic rather than narrative fashion to similarly specify that identity and function. Seen in this light, those particular items function in the same way as the natural items appearing in mythic narratives. As Claude Lévi-Strauss says of the use of characteristics of

particular birds in the myths of the Iban of South Borneo,

It is obvious that the same characteristics could have been given a different meaning and that different characteristics of the same birds could have been chosen instead. . . . Arbitrary as it seems when only its individual terms are considered, the system becomes coherent when it is seen as a whole set. . . . When one takes account of the wealth and diversity of the raw material, only a few of the innumerable possible elements of which are made use of in the system, there can be no doubt that a considerable number of other systems of the same type would have been equally coherent and that no one of them is predestined to be chosen by all societies and all civilizations. The terms never have any intrinsic significance. Their meaning is one of "position "—a function of the history and cultural context on the one hand and of the structural system in which they are called upon to appear on the other.[15]

By "reading" the visual myth that each god's appearance represents historically and structurally, we can understand the nature and function both of that particular god and of the creative process underlying the creation of all of the gods making up the Mesoamerican mythic system, for it is surely true, as Fray Durán commented, that "each of these ornaments had its significance and connection with pagan beliefs."[16]

Thus, Huitzilopochtli, as represented in Aztec art, must be seen as a visual myth designed to be "read" so that his image might communicate specific information about the world of the spirit to those who understood it and impress with its grandeur those who did not understand the more sophisticated levels of metaphoric meaning. It was designed to mediate for those "readers" between their world and the otherwise inaccessible world of the spirit. The figure of Huitzilopochtli is, in that sense, a typical product of the dialectical process by which Mesoamerican man created the continuum whereby he could transcend mundane reality and commune with the gods.

But it is important to emphasize that the set of symbols used to designate a particular god was not fixed; a good deal of variation was possible. Huitzilopochtli could "wear" his hummingbird nahualli as a headdress, as a back device, or not at all. His shield could be decorated with a quincunx of feathers or remain plain.[17] These are but two of the many possible variations of the basic symbols suggesting the fluidity of the concept of the god. Rather than being a fixed, static entity in the minds of those who manipulated the symbol system, each god was clearly a set of traits, each to be "used" as it was needed. This use of various traits is illustrated by the characteristic manipulation of a deity's image during the feast of Izcalli. Twice

they took out of the temple an image of the deity to whom it was consecrated: once adorned with a turquoise mask and with quetzal feathers, and once with a mask of red coral and black obsidian, and with macaw feathers. . . . Seler explains that this double adornment "symbolized the sprouting and maturing of the maize."[18]

Furthermore, the gods were also fluid in the sense that their identities often merged, overlapped, and folded into one another. As we saw above, the facial painting of each of the aspects of the quadripartite Tezcatlipoca indicated both their unity, in that they shared the same design, and their individual identities, in that each wore the design in colors appropriate to his particular function. While linked in this way to the other Tezcatlipocas, Huitzilopochtli was also linked to a series of gods who seemed to unfold from him and who shared his particular symbols. Paynal, for example, wore "the hummingbird disguise"[19] and represented Huitzilopochtli in ritual. Tlacahuepan and Teicauhtzin, among others, "seem merely to express aspects of his supernatural personality."[20] And as Alfonso Caso points out, Huitzilopochtli was also "an incarnation of the sun" and in that sense an aspect of Tonatiuh, the sun god, but his important symbolic use of the fire serpent, xiuhc6atl, suggested a relationship with Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire.[21]

In addition to these mythic connections with other gods, there is the connection with Tlaloc, the old god of rain and lightning, suggested by their placement side by side in the twin temples atop the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán, the symbolic center of the universe "from which the heavenly or upper plane and the plane of the Underworld begin and the four directions of the universe originate."[22] This placement suggests the dialectical method by which the Aztecs symbolically dealt with natural and spiritual forces. In one sense, Tlaloc was an agricultural force while Huitzilopochtli was concerned with the human forces of war. However, both rain (Tlaloc) and sun (Huitzilopochtli) were necessary for the growth of the crops and the maintenance of life. Similarly, Tlaloc as the old god who had existed from time immemorial in the Valley of Mexico could be seen as opposed to Huitzilopochtli, the young god who came to the Valley of Mexico with the Aztecs. But their placement together would suggest that they both served as patron gods of the Aztecs, comprising a unity transcending the opposed realities for which they stood individually. That larger unity, according to Pasztory, defined the Aztec self-image:

The migration manuscripts emphasize that the Aztecs were outsiders of humble origin who

prevailed because of their god, their perseverance, and their military powers. . . . These manuscripts answer the question "who are we, " with "we are the descendants of nomads led by Huitzilopochtli." The sculptures and architecture in Teotihuacán and Toltec style represent the Aztecs as upholders of ancient traditions. They answer the question "who are we" by saying "we are the legitimate successors of the Toltecs and their god Tlaloc. "[ 23]

Significantly, a similar set of relationships of opposition and concurrence could be worked out with all of the other major gods of the Aztecs.

From all of this we must conclude that the Mesoamerican system of "gods" is to be seen as a totality. Each of the individual gods is, in essence, a set of symbols, and these individual symbol sets merge to form what is typically, if misleadingly, referred to as a "pantheon." The term is misleading because it suggests a group of fixed individual deities, such as those of the Greeks or Romans from whom the concept is derived, each with an existence independent of the pantheon. The nature of the Aztec gods specifically and those of Mesoamerica generally, however, is different. They exist only as part of the relatively fluid set of relationships of spiritual "facts" which results from the Mesoamerican process of creation, which we have characterized as "unfolding," through which the life-force radiates outward from its source in the world of the spirit. The symbols that make up each of the "gods" is, in that very specific sense, a mask that specifies the particular aspect of the life-force, the particular "line of radiation," being addressed.

Although he does not apply his insight to Mesoamerica, Lévi-Strauss suggests the essence of the process involved in the construction and elaboration of this system of mediating entities throughout the long history of Mesoamerican spiritual thought. Speaking of the natural source of the images man combines to make the supernatural meaningful and accessible, he says, "even when raised to that human level which alone can make them intelligible, man's relations with his natural environment remain objects of thought: man never perceives them passively; having reduced them to concepts, he compounds them in order to arrive at a system." In other words, man analyzes his environment, isolates its component parts, and rearranges them in logical, but nonnatural, combinations. Thus, it is a mistake "to think that natural phenomena are what myths seek to explain when they are rather the medium through which myths try to explain facts which are themselves not of a natural but logical order."[24] If myth is defined to include "images, rites, ceremonies, and symbols" that demonstrate "the inner meaning of the universe and of human life,"[25] the "supernatural monsters" of Mesoamerican spiritual thought reveal themselves as logically constructed compounds of natural facts; each masked "god" is actually a "system" designed to explain a "fact" of the world of spirit.

Taken together, these masked and costumed figures comprise a complete system of mediation, logically constructed and ordered, that renders the essential reality of the world of the spirit comprehensible in the terms of the contingent reality man experiences in the world of nature. Another insight of Lévi-Strauss clarifies the process of construction.

The dialectic of superstructure, like that of language, consists in setting up constitutive units(which, for this purpose, have to be defined unequivocally, that is, by contrasting them in pairs) so as to be able by means of them to elaborate a system which plays the part of a synthesizing operator between ideas and facts, thereby turning the latter into signs . The mind thus passes from empirical diversity to conceptual simplicity and then from conceptual simplicity to meaningful synthesis.[26]

Each of the mask and costume elements must be seen as a constitutive unit in this sense, becoming a sign of something else in the simplification of nature's diversity by the order-making mind of man through the construction of a new, nonnatural order revealing the supernatural order at the heart of the world of nature. Thus, while each of the elements comprising the mask is a constitutive unit, one can also see each masked figure as a unit in the whole of the system that mediates between nature and spirit.

As our analysis of Huitzilopochtli makes clear, an understanding of the nature of any of the myriad Mesoamerican "gods" must come from a reading of the visual myth each presents. Each "constitutive unit" of the myth must be related to its sources in Mesoamerican spiritual thought, and the resulting combination of spiritual ideas will then "define" the god in question. Such a reading of the visual myth of Huitzilopochtli is relatively easy because the items that make up the "mask" he wears were provided by the Aztecs about whose thought we are relatively well informed. While the interpretive process becomes somewhat more difficult when we turn to those "gods" whose existence can be traced at least to the Preclassic, the method remains the same because the process of the "gods"' creation was demonstrably the same. To understand any of the Mesoamerican gods, we must read the constitutive units of which they are comprised; in this sense, the gods are the masks, and the masks are the gods.

The Mask As Metaphor

The Olmec Were-Jaguar

From the standpoint of Aztec civilization, Huitzilopochtli is of major importance, but from a

broader perspective encompassing all of Mesoamerica and adding the temporal dimension that allows a view ranging back as far as archaeology permits us to see, Huitzilopochtli pales into insignificance; he was only a god of the Aztecs. But the figure with whom he shared the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán suffers no such fate. Tlaloc, the god of rain, associated always with storms and lightning, has his roots deep in the Mesoamerican past. To understand the complex of symbols comprising his characteristic mask is to understand something fundamental about Mesoamerican spiritual thought, because that mask has its readily identifiable counterpart in every civilization that played a role in Mesoamerican culture and because, like Tlaloc, the figure identified by the rain god mask is in every case involved not only with the provision of the life-sustaining rain but also with divinely ordained rulership and several other equally fundamental themes of Mesoamerican spirituality. Thus, the mask of the rain god provides a particularly good example of the way Mesoamerica as a whole constructed metaphorical masks to delineate its gods.

Tlaloc, the Aztec incarnation of the complex of symbols associated with rain, is the rain god we know most about because, as with Huitzilopochtli, we have the evidence of the codices and the chronicles to supplement and clarify the information we can glean from the remains of art and architecture. The earlier civilizations of the Classic and Preclassic periods left us no such explanatory material. But although there has been some dispute about whether it is possible to use the information regarding Aztec culture to explain symbolic visual images from earlier cultures,[27] our analysis of rain god imagery that follows suggests that this particular complex of images can be traced from its origins in the relatively dim past to the time of the Conquest. It is undeniable[28] that certain symbolic visual traits occur in combinations consistently connected with rain. At times, it is possible to "read" the meanings of particular symbols even from very early times, and when it is possible, these meanings coincide remarkably well with those suggested by working backward from later times. Mesoamerica, after all, was one culture, however complex, with one mythological tradition. The complexity of cultural development over a large geographic area and a time span of three thousand years will necessarily cause difficulties for our full comprehension of its fundamental unifying themes, but the unity is always tantalizingly present; we must attempt to find it amid the artifacts archaeology provides for us.

What is easiest to demonstrate about the continuity of Mesoamerican spirituality from the earliest times is that the characteristic Mesoamerican way of constructing "gods," or masks, by combining a variety of natural items, that is, constitutive units, in unnatural ways begins very early and that certain combinations recur from those early times until the Conquest. The mask associated with the complex process of the provision of water by the gods, a process involving caves, underground springs, and cenotes as well as rain with its accompanying thunder and lightning is a case in point; the remarkable similarities in imagery in the features of the masks of the rain gods, a term we will use to denote this whole complex of associated meanings, created by each of the cultures of the Classic period in Mesoamerica certainly suggest the existence of a shared prototype in earlier, Preclassic times.[29]

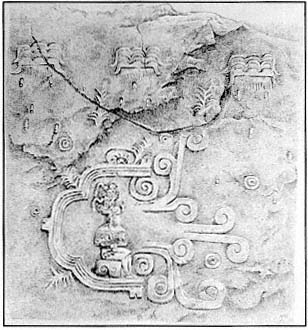

That prototype can be found in the first high civilization in Mesoamerica—that of the Olmecs. This argument was made clearly and forcefully as early as 1946 by Miguel Covarrubias, who constructed a chart (pl. 2) showing "the 'Olmec' influence in the evolution of the jaguar mask into the various rain gods—the Maya Chaac, the Tajin of Veracruz, the Tlaloc of the Mexican Plateau, and the Cosijo of Oaxaca."[30] But the tremendous number of archaeological discoveries and the equally large body of scholarly thought devoted to the Mesoamerican material since Covarrubias advanced this idea have revealed levels of complexity neither he nor anyone else imagined at that time. It is therefore doubly remarkable and a tribute to his deep intuitive understanding of the spiritual art of Mesoamerica that the Covarrubias hypothesis has held up quite well. That hypothesis, however, must now be understood in the light of more recent developments, which necessitates an explanation of recent thought regarding Olmec spirituality in general which, however, has clear implications concerning the fundamental nature of Mesoamerican spiritual art of all periods. That done, we can return more meaningfully to the features of the Olmec mask associated with rain.

Covarrubias, in addition to seeing the jaguar as involved with rain, believed that the jaguar "dominated" the art of the Olmecs and that "this jaguar fixation must have had a religious motivation."[31] As his chart suggests, however, it is not the jaguar himself who dominates Olmec art but rather the composite being who has come to be known as the were-jaguar, a creature combining human and jaguar traits. As Ignacio Bernal notes, "when one attempts to classify human Olmec figures, without realizing it one passes to jaguar figures. Human countenances gradually acquire feline features. Then they become half and half, and finally they turn into jaguars. . . . What is important is the intimate connection between the man and the animal."[32]

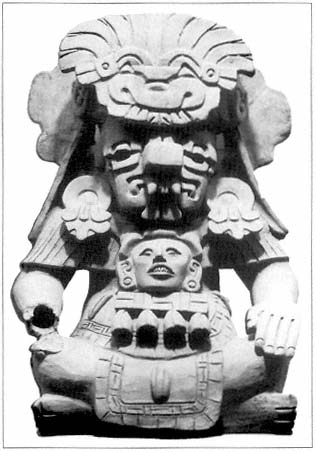

The contentions of both Covarrubias and Bernal must be further qualified by acknowledging the hypothesis of Coe and Joralemon regarding the Olmec gods, a hypothesis based on a recently dis-

Pl. 2.

Covarrubias' graphic representation of the evolution of the mask of the Rain God

from an Olmec source, which we designate Rain God C, through the Oaxacan Cocijo, in the

left-hand column, the Tlaloc of central Mexico in the next column, followed by the

Gulf coast rain gods and finally, those of the Maya in the right-hand column.

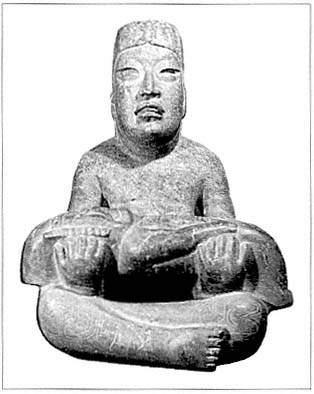

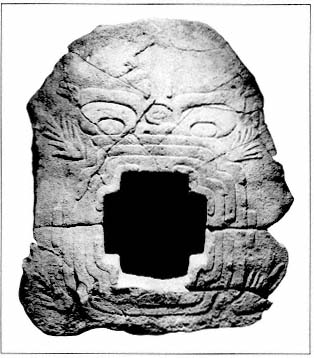

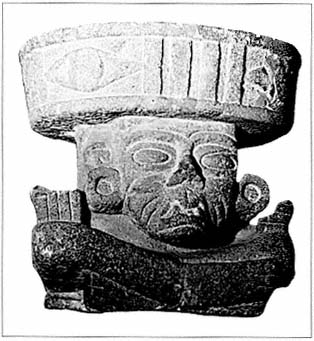

covered Olmec sculpture, the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3). As Coe noted, the knees and shoulders of the seated figure are incised with "line drawings," in typical Olmec style, of masked faces. Joralemon later discovered another mask incised on the figure's face which, with the mask "worn" by the infant, brought the total of distinctly different masked faces to six. After a great deal of analysis of the corpus of Olmec art by Joralemon, he and Coe have argued "that the Las Limas figure depicts the Olmec prototypes of gods worshiped in Postclassic Mexico" and that "Olmec religion was principally based on the worship of the six gods whose images are carved on the Las Limas Figure." Furthermore, Joralemon concluded that

the primary concern of Olmec religious art is the representation of creatures that are biologically impossible. Such mythological beings exist in the mind of man, not in the world of nature. Natural creatures were used as sources of characteristics that could be disassociated from their biological contexts and recombined into non-natural, composite forms. A survey of iconographic compositions indicates that Olmec religious symbolism is derived from a wide variety of animal species.[33]

Thus, Coe and Joralemon would probably not agree with Covarrubias's contention that the jaguar dominated Olmec religious art, but they continue to believe, as Covarrubias did, that there is a demonstrable continuity linking Olmec and Aztec gods.

Predictably, their theory caused tremendous controversy. Some objected to the argument from the analogy with Aztec and even more recent spiritual traditions; Beatriz de la Fuente, for example, objected to Coe's identifications on the grounds that they were

based on a comparison of the Aztec with the Olmec, the cultures having between them a span of some 2000 to 2500 years. They seek explanations for ancient forms in activities or beliefs of present-day peoples, whose societies have, furthermore, suffered the inevitable effects that result from the clash of native and western cultures .[34]

Another form of objection concerned the equation of certain traits with certain fixed and specifically defined gods. Contending that Joralemon had artificially isolated and emphasized certain visual features at the expense of others and neglected to pay sufficient attention to the complexity and fluidity of the combinations of features, Anatole Po-

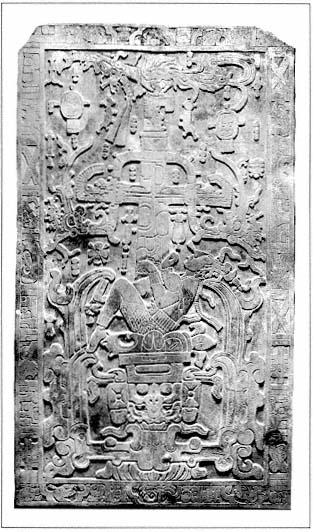

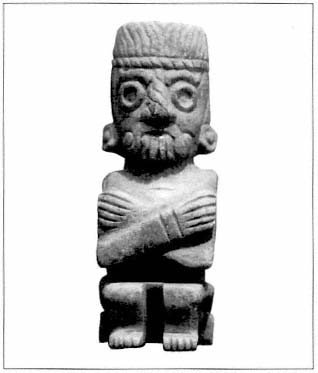

Pl. 3.

The "Lord of Las Limas," Olmec sculpture from Las Limas,

Veracruz; dimly discernible in this photograph are the masked

faces incised on the figure's face, shoulders, and knees; the

face of the child held by the figure is an excellent example

of our Rain God CJ (Museo de Antropologia de Xalapa).

horilenko maintained that "there are no Olmec compositions which consistently depict recurring combinations of the same referential signs. . . . For instance, a four-pointed flaming eyebrow is not exclusively and consistently used with a jaguar mouth showing slit fangs and an egg-tooth. "[ 35] Thus, both de la Fuente and Pohorilenko suggest, in rather different ways, that the Coe-Joralemon hypothesis is too rigid, too specific in its identification of the gods of the Olmecs.

Accepting these objections, however, neither invalidates nor trivializes the fundamental insight at the heart of the argument advanced by Coe and Joralemon: Olmec religious art, rather than betraying a fixation on the jaguar, presents a variety of composite beings, each delineated in a characteristic mask and each a symbolic construct derived from a variety of natural creatures. Furthermore, these varied figures must be seen as the component parts of an all-inclusive system that mediated between man and the powerful forces originating in the world of the spirit. While it is possible to feel that the identification of specific Olmec figures with specific Aztec gods is unwarranted, it seems unarguable that, as Coe and Joralemon have allowed us to see, the Olmecs created a mediating system of gods to establish a relationship between man and the world of the spirit in precisely the same manner as did the Aztecs, their distant Mesoamerican heirs. There is, then, a demonstrable continuity linking Olmec and Aztec spiritual thought. In fact, the Olmecs are the likely originators of this characteristic Mesoamerican practice of creating a spiritual system composed of a large number of interrelated "gods," each of which is represented by a mask and costume made up of symbolic features. The seemingly endless parade of Mesoamerican gods tricked out in their fantastic regalia probably begins at La Venta.

These gods can be seen in Olmec religious art, but when one looks closely at the way they are depicted, the identification of particular clusters of features as specific, recurring deities does not seem as simple as the Coe-Joralemon hypothesis suggests. Two sorts of complexity must be reckoned with. First, three distinct categories of figures exist in Olmec art despite the fact that some figures straddle the boundary between two categories. Only one of these categories is made up of figures that stand as metaphors for the supernatural, that is, the Olmec "gods." Second, even within that category, there are, as Pohorilenko points out, a very large number of combinations of the basic repertory of symbolic features.

The first of these levels of complexity is easiest to deal with. Although all Olmec art is essentially religious,[36] that religiosity expresses itself in three different ways, sharing only a fascination with natural forms, especially the form of the human body. The first category glories in the presentation of the human form and countenance in all its ideal beauty. Perhaps the best example of this is the sculpture from San Antonio Plaza, Veracruz, which is often called The Wrestler. Its sensitively realized dynamic pose and clearly but delicately delineated physical features reveal the Olmec artist's desire and ability to idealize the human body as a purely natural form of beauty almost spiritual in its compelling vitality. And that elusive spirituality is also hinted at by the slightly downturned mouth suggestive, of course, of the symbolic were-jaguar. The well-known colossal heads and the characteristic jade and jadeite masks, both realistic enough to suggest portraits,[37] often evoke the ideal beauty of the human countenance and similarly hint at man's basically spiritual nature.

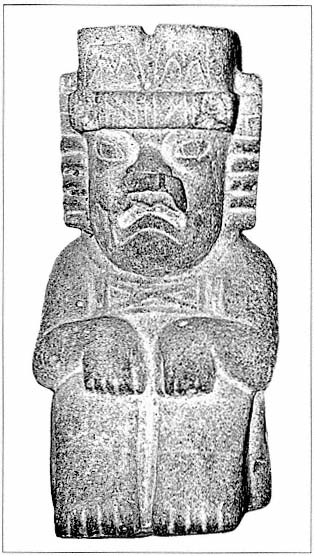

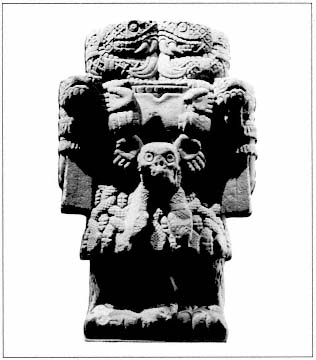

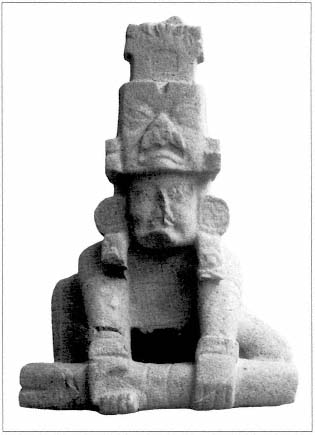

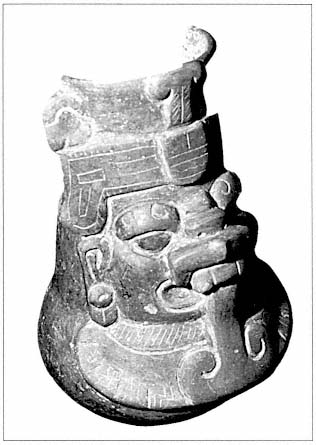

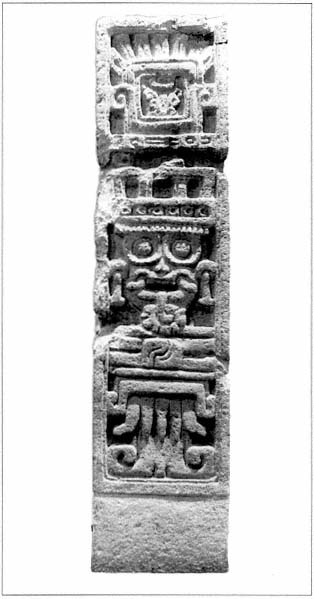

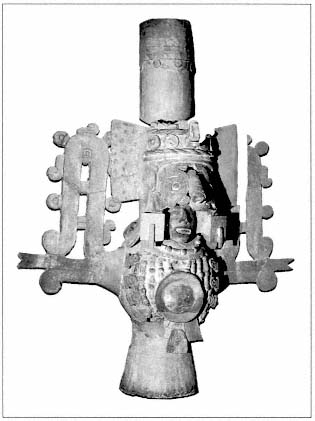

Opposed to these realistic depictions of human features, a second category of Olmec art depicts fantastic composite beings whose faces are masks comprised of natural features combined in strikingly nonnatural ways, denizens of the world of the spirit rather than the world of nature. Though the human body provides the basic form for the sculptures, they are clearly not human. San Lorenzo Monument 52 (pl. 4), which is analyzed in detail below, serves as an excellent example of the type. Everything about it—its combination of fa-

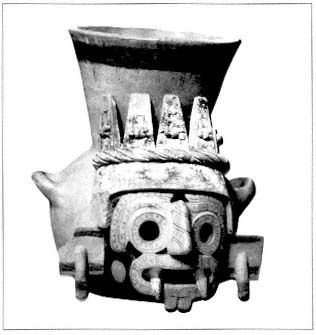

Pl. 4.

Monument 52, San Lorenzo, our "Rain God CJ"

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

cial features, its human body with nonhuman hands and feet, and its stylized form and unnatural proportions—proclaims it a mythological creature rather than a natural one. As anyone even slightly familiar with Olmec art is aware, such composite beings, once thought to be primarily were-jaguars, are so frequently depicted as to be practically characteristic of that art. These composite beings are, collectively, the Olmec metaphor for the domain of the spirit, a domain that could be conceptualized only by departing from the order inherent in the natural world. No doubt the Olmecs, like their Mesoamerican heirs, saw a creator god, their prototype of an Ometeotl, in this spiritual realm, a creator who was not depicted, a force so essentially spiritual that it could not be encompassed and ordered by human thought. The mythological creatures who populate Olmec art are the "unfoldings" of this spiritual essence.[38]

Significantly, there is a third category of Olmec artistic representation that mediates between the first two diametrically opposed categories. It depicts realistic human beings, as does the first type of Olmec art, but they are masked and costumed to resemble the mythological creatures of the second type. Mural I of Oxtotitlán, Guerrero (pl. 5), provides the clearest representation of such a figure. The seated man is depicted x-ray fashion, as the Maya were to do later,[39] disclosing the realistically rendered human being within the fantastic birdlike disguise. These are ritual figures, and we will explore their symbolic dimensions in the later discussion of the mask in ritual.

These three categories of Olmec figural representation—human, mythological, and ritual—reveal an Olmec conception of the universe basically the same as, and thus the logical prototype of those of, the later cultures of Mesoamerica delineated in the second part of this study. For the Olmecs, the world of nature, symbolized in art by the realistically rendered human figure, was imagined as the binary opposite of the world of the spirit, symbolized by the composite beings. The masked ritual figures show man's way of mediating between those two opposed realms. Though her analysis of Olmec art is quite different from ours, de la Fuente grasps the essential nature of that art: "The human figure, the gravitational center of almost all the forms of Olmec art, appears in this art with different metaphysical definitions which, at their extreme, seem to repeat . . the entire order of the universe."[40] Thus, this symbolic art allowed the Olmecs to represent their conception of the cosmic

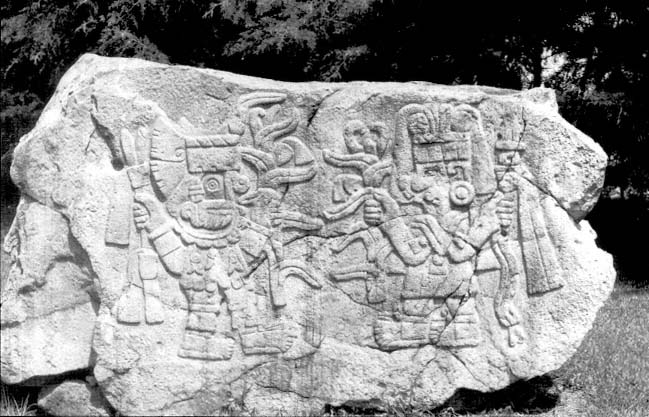

Pl. 5.

Mural I, Oxtotitlán, Guerrero displaying the x-ray convention

which allows the simultaneous depiction of the features of the wearer

of the ritual mask and of the features of the mask itself

(drawing by David Grove, reproduced by permission).

structure in visual form by symbolically reordering the materials of nature.

Distinguishing carefully between the three different categories of the art through which the O1mecs represented the tripartite cosmic structure allows our discussion of the gods to focus on those works of art representing the fantastic composite beings who symbolized the forces of the world of the spirit. But there is another form of complexity that must also be acknowledged: as Pohorilenko pointed out, the features of these composite beings are not characterized by a limited number of combinations of the same symbolic features. On the contrary, though the total number of features is not great, they are combined in what often seems to the would-be iconographer an endless series of combinations. In view of the limited state of our present knowledge of Olmec spiritual thought—Jacques Soustelle says, "We are overawed by the immense depths of our ignorance"[41] —we believe it would be impossible to determine which of those combinations, if any, the Olmec priesthood identified as named deities. When we think of how little we know of Olmec thought in comparison to the relative wealth of information we have about Aztec spirituality and then realize that even with the knowledge of Aztec spiritual thought provided by the codices and chronicles, there is still a great deal of uncertainty involved in the identification of many Aztec gods represented in art,[42] our difficulties become clear. Fortunately, what we do know of Aztec art can help us to understand their distant forebears.

Our brief analysis of Huitzilopochtli revealed that not all of the symbols associated with him by the Aztec priesthood need be present in any particular depiction of him and, furthermore, that it was possible within the Aztec symbol system to create figures combining the features usually associated with particular gods. We term these combinations "secondary masks" and will discuss them in the conclusion to our consideration of the mask as metaphor for the gods. The Aztec system was an extremely complex one built up—like the calendrical systems of Mesoamerica—through the permutation of a limited set of symbolic features through the range of their possible combinations. If the Olmec system was similarly constructed, and the evidence suggests overwhelmingly that it was, it seems unlikely that, lacking codices and chronicles or other explanatory material, we will ever be able to reconstruct the system as it would have been understood by the Olmec priest.

This is not to say, however, that we cannot "read" particular symbolic features and understand the general ritual or mythological function they probably served. This then enables us to understand the more complex meaning that a cluster of individual symbolic features could carry, but the more complex the configuration, the more general our understanding is likely to be. Thus, a number of such clusters can be shown to refer generally to rain and lightning, vegetation and fertility, and divinely ordained leadership. It is no doubt true that each of the configurations conveyed a particular shade of meaning to the Olmec priest, and it is certainly possible that each of them was a particular "god." It is equally possible, however, that many of them were aspects of one basic spiritual essence, particular manifestations of a single "god." And it is also possible that none of them was thought of as a god at all but rather as a collection of spiritual "facts" joined together temporarily to make a mythological or ritual statement. It is therefore difficult to talk about the gods of the Olmec but not nearly so difficult to discuss the ways the 01mecs symbolized the forces they identified with the world of the spirit. Through an analysis of the individual features that occur on the symbolic masks, we can begin to understand at least this much about Olmec spiritual thought.

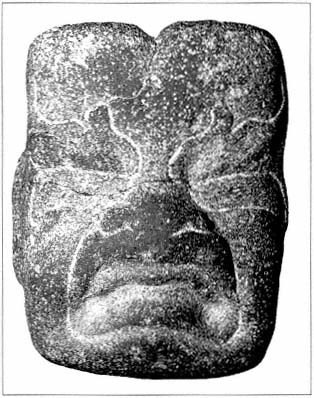

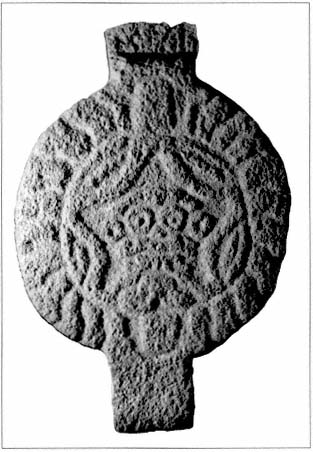

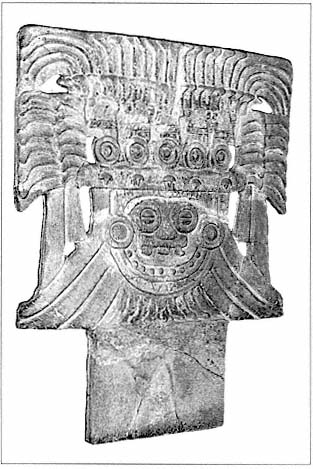

Thus, to return finally to our discussion of the mask representing the rain god, we can concur with Covarrubias, Bernal, and Coe and Joralemon that a mask combining particular features drawn from nature was associated by the Olmecs with the provision of the life-maintaining rain from the world of the spirit. We, and most other scholars who have studied Olmec art, would further agree that the particular "god" associated with rain is a were-jaguar,[43] that is, a mask dominated by the characteristically feline mouth with downturned corners beneath a pug nose. But this general agreement comes to an end when specific masks are discussed. The particular were-jaguar depicted at the bottom of Covarrubias's chart as the archetypical rain god, a stone mask or face panel now in the American Museum of Natural History in New York (pl. 6), differs in several symbolic features from the were-jaguar identified as the Rain God by Coe and Joralemon, a composite figure typified by the were-jaguar child held by the Las Limas figure (pl. 3) and seen clearly on San Lorenzo Monument 52 (pl. 4). Those differences account for Joralemon's seeing the Covarrubias mask (which we will call Rain God C) as representing his God I,[44] "the Olmec Dragon," rather than the Rain God he and Coe have designated as God IV (which we will call Rain God CJ).

These differences should not, however, obscure some fundamental similarities. Both Rain God C and Rain God CJ have generally rectangular faces with cleft heads, pug noses, heavy upper lips, and downturned mouths showing toothless gums. They differ in their ears or ear coverings—C's are long, narrow, and plain while CJ's are long, narrow, and wavy; in their eyebrows—C's are the so-called flame eyebrows while CJ's are nonexistent, replaced by a headband with markings which is part of a headdress; and in their eyes—C's are trough

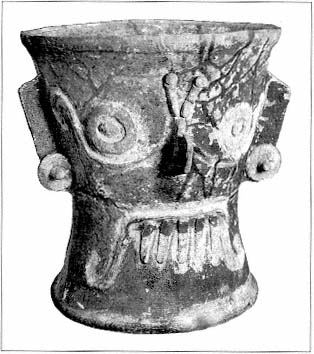

Pl. 6.

Olmec stone mask, probably architectural, our "Rain God C"

(American Museum of Natural History, New York).

shaped and turned downward at the sides while CJ's are almond shaped and turned upward; CJ wears the typical Olmec St. Andrew's cross as a pectoral while C, being only a mask, of course has no pectoral. Perhaps significantly, the tops of the heads of the two are similar as are the bottoms, that is, the mouth areas. The differences occur in the middle zone of the faces. And it seems even more significant that, to a casual glance, the similarities are far more apparent than the differences; the two faces seem clearly to be variations on a single theme, perhaps the variations that would identify the aspects of a quadripartite god. We believe that an analysis of their symbolic features will demonstrate that a casual glance does in fact reveal an essential truth and that the symbolic features all refer to fertility connected with rain.

Beginning at the top, the first symbol is the cleft head, which Coe and Joralemon evidently do not see as diagnostic since each of their six gods is sometimes depicted with a cleft head and sometimes without. The presence or absence of the cleft, in the light of our earlier analysis of the four Tezcatlipocas whose faces are fundamentally similar with minor variations to indicate their distinct identities, is a tantalizing suggestion that these symbolic faces might also be manifestations of a quadripartite god. Whether this is true or not, however, when one examines the occurrence of the cleft head in Olmec art,[45] several significant facts emerge. First, cleft heads seem to occur only on masks that contain other clearly symbolic features and not on the relatively naturalistic masks and sculpture. This, incidentally, is not true of the symbolic were-jaguar mouth. Second, the cleft appears in two opposed forms, either empty or with vegetation appearing to emerge or grow from it. Third, the empty cleft seems to be found in certain contexts, the vegetal cleft in others. Votive axes were often carved with their upper halves as were-jaguars with cleft heads, but the clefts are always empty.[46] Celts, however, are often decorated with incised masks; when those masks are cleft-headed, the clefts are vegetal. Thus, the appearance of the cleft seems to follow a pattern. These facts would indicate that the presence or absence of the cleft and the form it takes have sufficient symbolic importance to be governed by rules and that it makes a significant contribution to the overall meaning of the symbolic cluster in which it appears.

That the cleft has symbolic importance is further suggested by the fact that it appears only on masks containing other clearly symbolic features and not on the more naturalistic ones. But to understand its function, we must first decipher its symbolic meaning.[47] The fact that the cleft is often depicted with vegetation, probably corn, sprouting from it suggests fertility, and the associations of the other symbolic features on the masks on which it is found with water surely support that connection. As the source of the growing corn plant, it suggests the "opening" in the earth from which life emerges, the symbolic point at which the corn, the plant from which man was originally formed and which was given by the gods as the proper food for man and thus a symbol of life and fertility, can emerge from the world of the spirit to sustain mankind on the earthly plane.

That symbolic connection is reinforced by the fact that the V-shaped cleft, or inverted triangle, has been since paleolithic times a specifically female symbol representing, in human terms, the point of origin of life. Peter Furst discusses the occurrence of this motif in the much later Mixtec codices as a means of identifying these Olmec clefts with "a kind of cosmic vaginal passage through which plants or ancestors emerge from the underworld" and laments the "enormous span of time dividing them" as possibly calling into question the validity of reading Olmec symbols with this Mixtec "language."[48] However, Carlo Gay's discussion of the highly symbolic designs found in pictographic form in shallow caves associated with the Olmec fertility shrine at Chalcatzingo would seem to lay that objection to rest, if indeed these pictographs are contemporary with the Olmec art found at that site.[49] He records the occurrence of "triangle and slit signs [that] are among the most graphic of vulval representations"

among the many sexually related symbols in those pictographs found at a site obviously dedicated to fertility,[50] signs that are identical in shape to the cleft in the were-jaguar head.

That a sexual symbol would occur on the head of a composite being generally seen as remarkably childlike or sexless is perhaps not so strange. The spiritual thought of Mesoamerica is, in a sense, fundamentally sexual in nature. Its ideas regarding the transformative nature of creation through unfolding, which we will delineate in our consideration of the entrance of the life-force into the world of nature (Part II), surely parallel the natural, sexual process of regeneration. Its persistent emphasis on duality—opposites coming together to form a unity—has one of its most obvious examples in the sexual act. Its emphasis on caves as places of origin must surely be connected with the emergence of the child from the womb as the final result of the sexual act.[51] And its common conception of the fertile earth as female clearly has a sexual origin. But the conventions governing Mesoamerican spiritual art did not allow direct expression of this sexual metaphor. Generally speaking, though there are notable exceptions, throughout the development of Mesoamerican art and thought any depiction of sexual organs or the sexual act was taboo. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that sexual symbols should appear in disguised ways. Although not overtly sexual, the cleft head carries the sexual meaning: it symbolizes creation, especially as that creation takes the form of agricultural fertility, but by extension it can refer to any related instance of life entering the world in the cycle of life and death. Perhaps the vegetal cleft refers directly to agricultural fertility and the empty cleft to the concept of birth and rebirth in a more general sense, especially as it relates to such state-related matters as rulership and sacrifice.

The fertility theme is also the focus of the other symbol the two rain god masks share, the characteristic were-jaguar mouth. The mouth is, of course, far more striking than the cleft, so striking that it has come to be seen as characteristic of Olmec art generally. But before discussing the complex set of symbolic associations it makes, it might be well to clarify what it is since there have been numerous suggestions that it is not a jaguar mouth or even feline. Peter Furst and Alison Kennedy claim that what is represented is the toothless mouth of a toad, the fitting representative of the earth. Terry Stucker and others and David Grove see the mouth as sometimes crocodilian, and Karl Luckert, who sees the facial configuration as that of a serpent, goes even further by claiming that not only is this mouth not that of a jaguar but, aside from three figures, there are no jaguar representations at all in Olmec art.[52] In our view, however, and that of most other Mesoamericanists, the typical were-jaguar mouth is just that, the mouth of a jaguar with some features exaggerated for symbolic reasons and some modified to fit the human facial configuration. The heavy pug nose that is an integral part of the configuration and the general frontal flatness of the mouth segment are typically feline and not at all serpentlike. Furthermore, when the body of the figure on which the mouth is generally found is taken into account, both the posture and numerous anatomical details suggest the jaguar. In addition, the jaguar is indisputably represented with reasonable frequency in Olmec art,[53] and it is an important symbolic creature in every Mesoamerican culture that succeeded the Olmecs and was used by each of them as a source of attributes for its gods. And there are several Olmec sculptures that clearly combine the features of the feline with those of man and that depict the characteristic mask.

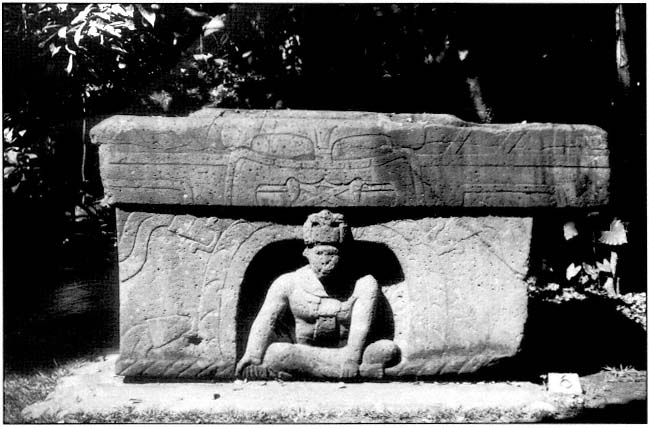

But it is important to recognize that while the jaguar is the most likely source of the nose/mouth configuration, that facial feature is a highly multivocal symbol that has meanings other than those related to the creature from whom it was taken. Two of those other meanings can be seen in Monument I (pl. 7) from the Olmec fertility shrine of Chalcatzingo which depicts a figure holding a ceremonial bar signifying rulership seated within a stylized cave mouth that lies under three stylized clouds from which raindrops are falling. The clouds themselves bear a striking resemblance to the heavy upper lip of the were-jaguar mouth, and the cave is that very mouth represented in profile, as is made clear by the appearance above it of an eye bearing the Olmec St. Andrew's cross on its eye-

Pl. 7.

Monument I, "El Rey," Chalcatzingo, Morelos (drawing by Frances Pratt,

reproduced by permission of Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria).

ball, the same cross found on the pectoral of Rain God CJ and occasionally found on one or both eyes of were-jaguar masks. A further indication that this cave is to be seen as a mouth are the "speech scrolls" issuing from it in typical Mesoamerican fashion.

The identification of the cavity as a mouth is strengthened by another bit of evidence external to the relief itself. A freestanding monument found at Chalcatzingo, Monument 9 (pl. 8), is a frontal view of the were-jaguar mouth/cave represented in profile in Monument I. It has the same eyes and the same ridged mouth with vegetation sprouting from its "clefts" in a fashion reminiscent of the cleft heads, and further suggesting the close relationship between the two symbolic works is the apparent use of Monument 9. According to Grove, the carved slab, when erected for ritual use on the most important platform mound at Chalcatzingo, was designed to be entered: "The interior of the mouth is an actual cruciform opening which passes completely through the rock slab. Interestingly, the base of this opening is slightly worn down, as if people or objects had passed through the mouth as parts of rituals associated with the monument."[54] It replicated the natural cave and allowed the ritual "cave" to be entered through the mouth of the composite being representing the world of the spirit, which the ritual enabled man to contact. The seated figure depicted in Monument I has entered that same liminal zone from which issues the "speech" of the supernatural. Thus, the relief designated Monument I relates the cave to the rain cloud by visually associating both of them with the were-jaguar mouth.

Such an association of caves and clouds seems as strange to us as it did to Evon Vogt when he encountered it in his work with the present-day Maya of Zinacantan. But he learned that in the context of the Mesoamerican environment, it is not so strange.

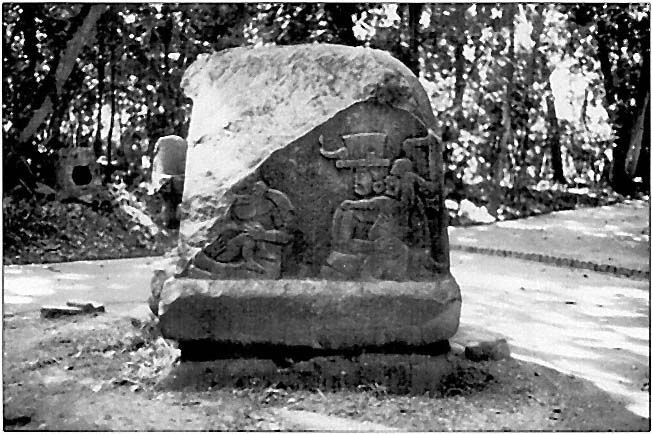

Pl. 8.

Monument 9, Chalcatzingo, Morelos (MunsonWilliams-Proctor Institute,

Utica, New York; photograph courtesy of that institution).

I have had a number of interesting conversations in which I have attempted to convince Zinacantecos that lightning does not come out of caves and go up into the sky and that clouds form in the air. One of these arguments took place in Paste [ * ]as I stood on the rim with an informant, and we watched the clouds and lightning in a storm in the lowlands some thousands of feet below us. I finally had to concede that, given the empirical evidence available to Zinacantecos living in their highland Chiapas terrain, their explanation does make sense. For, as the clouds formed rapidly in the air and then poured up and over the highland ridges . . . they did give the appearance of coming up from caves on the slopes of the Chiapas highlands. Furthermore, since we were standing some thousands of feet above a tropical storm that developed in the late afternoon, I had to concede that it was difficult to tell whether the lightning was triggered off in the air and then struck downward to the ground, or was coming from the ground and going up into the air as the Zinacantecos believe.[55]

The Olmec connection between caves and clouds apparent on Monument I indicates that today's Zinacantecos have a belief system rooted deep in the past. And that Olmec connection between caves and clouds and the were-jaguar mouth clearly worked in reverse as well; the shape of the mouth called to the Olmec mind caves and rain clouds as well as jaguars.

The connection at Chalcatzingo between these elements is supported by the existence there of numerous miniature, artificial "cavities" linked by a system of miniature carved drain channels[56] evidently designed for the symbolic movement of water in the ritual reenactment at this fertility shrine of the provision of water by the gods. There is also a curious relief carving, Monument 4, that depicts a feline creature, perhaps devouring a man, associated with a branched design that might represent "the pattern of watercourses of the valley north of Chalcatzingo"[57] which would thus flow symbolically from the mouth of the "jaguar." This concern with systems through which water flows is not an isolated phenomenon; the Olmec cave-shrine at Juxtlahuaca, Guerrero, exhibits a comparable, though different, system. These symbolic structures, and others no doubt yet to be found in

the caves of Guerrero, were perhaps the first instances of the jaguar mouth/cave/drain combination that finds its most celebrated example in the carved drain running the length of the cave under the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán.

Even more significant for our discussion of the Olmec rain god is the fact that the symbolic use of a system of drains also occurs at all four of the major sites in the Olmec heartland on the Gulf coast, though not in association, so far as we know, with caves. "The complex of artificial lagoons or water tanks on the plateau top and the drain systems associated with them form one of the most unusual aspects of San Lorenzo architecture," according to Richard Diehl, and from an archaeological point of view

the association of Monuments 9 and 52, both of which depict water-related symbolism, with the drain system, the geometric shapes of some of the lagoons, and the fact that the scarce and expensive basalt was used for the drain system instead of wood, all suggest that the system had more than a strictly utilitarian meaning to the Olmec.[58]

All of this, of course, suggests ritual use in the reenactment of the gods' provision of water. Although there are no caves associated with this man-made system of drains and lagoons at San Lorenzo, the fact that the drain channels were carefully covered and that they emptied into the lagoons suggests they may have been used symbolically to recreate the emergence of water from the "heart" of the earth in the fashion of an underground spring feeding a pool of water. One thinks in this connection of the cenotes held sacred by the Maya of the Yucatán.

It is quite significant that the were-jaguar mouth is also linked to this symbol of the gods' provision of water since Monument 52 (pl. 4), one of the primary images bearing the mask of Rain God CJ, "was discovered at the head of the principal drainage system."[59] Further suggesting its relationship to the drain system, the back of the sculpture is fashioned in exactly the same U-shaped form as the basalt stones of which the drain system was constructed. Symbolically, both the drain and the god are "conduits" for the movement of water, the fluid needed to maintain life, from the world of the spirit to the world of man. Whether as the cave mouth or the point at which an underground spring bubbled to the surface, the were-jaguar mouth was surely seen by the Olmecs as the liminal point of mediation between the source of spiritual nourishment located within the essentially female earth and the world of man that existed on the earth's surface. And that mouth was a primary feature of many of the symbolic masks constructed by the Olmecs, masks that, in what was to become the time-honored Mesoamerican fashion, designated the point of contact between the world of nature and the world of spirit, the interface between man and the gods.

But why connect the jaguar with rain? The connection might seem an unlikely one to the modern scholar who probably has never encountered a jaguar outside a book, movie, or zoo and surely hopes never to do so. Similarly, the scholar has been sheltered to some extent by the conveniences of modern urban life from the terrible reality of brutal storms and floods, on the one hand, and drought, on the other. In this respect, the inhabitants of the jungles and forests of Preclassic Mesoamerica knew far more than we do about both jaguars and rain from personal experience as well as from the shared experiences of their group, knowledge that no doubt suggested numerous possible connections between the two. They would have known that the jaguar truly was the lord of the Mesoamerican jungle: it is the largest cat in the western hemisphere, weighing as much as 300 pounds and measuring up to 9 feet in length and almost 3 feet in height at the shoulder[60] and because of its size and power, has no natural enemies. Two other creatures used symbolically by the Olmecs, the crocodilian and the snake, might kill young jaguars, "but adult jaguars regularly hunt full-grown caimans as food" and hunt and eat the giant anaconda.[61] The Olmecs might have had an even stronger reason to respect the jaguar than the fact that it preyed on the most powerful creatures in its habitat. According to a modern guide to game animals,

the jaguar is the only cat in the Western Hemisphere that may turn into an habitual man-eater. There are two reasons for this. One is the jaguar's large size and superior strength. . . . The second reason is that most jaguars live in areas where the natives do not possess firearms. Although the jaguar often has been killed with spears and bows and arrows, it takes an expert hunter to do it."[62]

The formidable power of the jaguar, then, was impressive enough to have served as the basis of a symbolism that continued to exist until the Conquest and to some extent continues even today. As Eduard Seler points out, "the jaguar was to the Mexicans first of all the strong, the brave beast, the companion of the eagle; quauhtli-océlotl 'eagle and jaguar' is the conventional designation for the brave warriors."[63]

The jaguar must also have seemed almost supernatural in its typically feline ability to move almost noiselessly despite its great size and in its surprising ability to move equally well on land, in water, and in the air.

The jaguar is the most arboreal of the larger cats. It climbs easily and well. . . . At those times of the year when its jungle home turns into a huge flooded land, the jaguar takes to the trees and may actually travel long dis-

tances hunting for food without descending. Water holds no fear for the jaguar, and it swims well and fast, frequently crossing very wide rivers. On the ground, jaguars walk, trot, bound and leap. Their speed is great for a short, dashing attack.[64]

These qualities explain why, as Covarrubias discovered, "even today the Indians regard the jaguar with superstitious awe; subconsciously they refer to it as The Jaguar, not as one of a species, but as a sort of supernatural, fearsome spirit."[65]

The storms that lash the Gulf coast—the nortes during the winter months which can bring winds up to 150 kilometers per hour, making coastal navigation impossible, and the hurricanes of late summer and fall with wind velocities over 180 kilometers per hour and tremendous amounts of rain producing destructive floods[66] —make it possible to appreciate the range of possible connections between rain and the jaguar. Rain for the Olmecs was not April showers. In the Veracruz heartland it fell throughout the year and was often accompanied by tremendously destructive storms. Even without the storms, the quantity of rainfall could cause disastrous flooding.[67] In the central highlands, the other area in which a substantial amount of symbolic Olmec art depicting the were-jaguar is found, the more common Mexican rainfall pattern prevails; there are distinct dry and rainy seasons. In that area, a lack of rain at the right time can cause the death of the corn by which man survives. The destruction caused by drought, though different from that wrought by a hurricane and flooding, is just as devastating. The problem for man in these environments is not to "bring rain" as many people think. Rather, man must attempt to bring the elemental forces represented by rain and storm under human control, reduce them to an order that will make the orderly life of culture possible. This, for early man, could only be accomplished through ritual that would enable him to interact with the source of all order, the underlying, otherwise unreachable realm of the spirit.

The ritual control of the rain-related forces probably involved the jaguar because it was the animal equivalent of the storm, equally powerful, equally sudden in its attack, equally destructive of human life and order. Furthermore, the jaguar was at home both in water and in the trees from which it was able to fall, like the storm, on its prey. Like the storm, it was a force that revealed itself in the natural world outside man's control, a force that could be seen as symbolically at the apex of the "unordered," wild forces of nature. By creating the were-jaguar mask, the Olmecs combined the creature who epitomized the forces of nature with man, the epitome of the force of culture. In typical Lévi-Straussian fashion, they created the were-jaguar mask as the dialectical resolution of the binary opposition between the untamed forces of nature and the controlled force of man. While the jaguar hunts with natural weapons (teeth and claws), lives entirely from hunting, and eats his prey raw, man hunts with artificial weapons for food that is a supplement to his staple diet derived from cultivation and eats his food cooked. The jaguar, though generally remaining in the same area, seldom has a den, "usually curling up to sleep in some dense tangle or blowdown,"[68] while man constructs a dwelling and returns to it each night. The jaguar acts instinctively while man can act rationally. In a sense, then, man and jaguar are equal opposites, and the were-jaguar by virtue of combining the force of man with the forces of nature brings together both aspects of the life-force in a being who can thus mediate between man and the origin of that force. By donning the mask in ritual to become that being, man could bring the otherwise destructive elemental forces under control so that they might aid in the maintenance of life by providing the rain in moderation so that the corn would grow and his own life would be maintained.

Thus, the were-jaguar mouth makes symbolic sense, but a glance at that mouth on Rain Gods C (pl. 6) and CJ (pl. 4) reveals a remarkable difference between image and reality; these were-jaguar mouths are toothless. The significance of this is made more apparent by the fact that although there are a great number of fanged were-jaguar mouths in Olmec art, Covarrubias and Coe and Joralemon have selected toothless images to represent the rain god. That this selection is correct is suggested, at least in the case of Rain God CJ, by the water associations of Monument 52. The lack of fangs might suggest visually the association with caves that would be somewhat more difficult to see were the mouths fanged, but the toothless mouth also carries other connotations linked in Mesoamerican thought to rain. The were-jaguar mask is often called a baby-faced mask, the reason for which can be seen in the more naturalistic faces that bear the same toothless were-jaguar mouth that we see here. In the context of the puffy cheeks and chubby facial configuration of those faces, the mouth looks like that of a pouting infant. When the face is found on a body with infantile features, as it often is, the designation seems even more apt. The child held by the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3) is just such a figure and is, significantly, another primary image of Rain God CJ.

The association of infant and were-jaguar mouth inevitably brings to mind the ritual sacrifice of children to the rain god by both the Postclassic Maya and the peoples of central Mexico, a characteristic form of sacrifice that may well have a prototype in Olmec thought and ritual, as the seemingly lifeless body of the infant held by the Las Limas figure suggests. Most commentators explain this form of sacrifice in the terms suggested by Sahagún, as a form of sympathetic magic where-

by the tears of the children cause the rain, that is, "tears" of the gods, to fall.[69] And Thompson suggests that the rain gods "liked all things small";[70] their "helpers," the tlaloques or chacs , like today's chaneques , were thought of as dwarfs, though not children.[71] In addition to these connections between small children and rain, however, one might also see in this ritual the return of a child to the womb of the earth from which he has only recently emerged. Such an interpretation would accord with one of the means of sacrificial death—drowning in such a manner that the bodies never again rose to the surface—as well as the burial rather than cremation of the bodies of victims sacrificed in other ways to Tlaloc. The common Mesoamerican conception of the sacrificial victim as the bearer of a message to the gods would seem to support this interpretation, as would the symbolic identification of caves as both the womb of the earth and the source of rain and lightning. The lifeless body of the were-jaguar child held by the Las Limas figure whose infantile features are often found on Olmec figures would thus symbolically unite these diverse ideas.