Preferred Citation: Weiner, James F. The Heart of the Pearl Shell: The Mythological Dimension of Foi Sociality. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1988 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7w10087d/

| The Heart of the Pearl ShellThe Mythological Dimension of Foi SocialityJames F. WeinerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1988 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Weiner, James F. The Heart of the Pearl Shell: The Mythological Dimension of Foi Sociality. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1988 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7w10087d/

Foreword

Social scientists often write the signature of their age in the unstated assumptions they make about the nature and reality of their subject. For anthropologists of the colonial era, the reality of society corresponded to a native "administration"—official conventions for the adjudication of person and property. The more recent regime of political independence overlaid by economic colonialism has favored the realities of obligation, circulation, and reciprocity. Although it is intriguing to speculate as to what tokens of solidity and credibility a future anthropology might develop, the more pressing issue is that of the unstated assumptions themselves. Where is the "reality" of society, and what ought we make of the idea? What guarantees the credibility of social exchange and relationship?

The Foi people of the Mubi River say that "the heart of the pearl shell" is nowhere, that its reality is, as their myth paraphrases Catullus, "written on the wind, and inscribed in running water." Among the finest achievements of Dr. Weiner's supple and powerful argument is its fidelity to this penetrating indigenous insight. Dr. Weiner does not seek to "cash in" the heart of the pearl shell for a wealth-equivalent in economic exchange, to invest it in a sociology of invidious rights and interests, or to materialize it as putative groups or systems.

A telling and successful study of the meanings of a sociality implies more than the acceptance of local insights, however; it requires the analytical penetration of a world of unfamiliar significances. It may be tempting enough for those with no patience or no head for theory

to take the myths, the practices, the art objects of another people at face value. Idealism of this sort has much to offer; it salves the ethical conscience and it monumentalizes the "data." But insofar as a viable anthropology is concerned it is the kiss of death. For projection is the inevitable consequence of unstated assumptions: when it is assumed that the meanings of another culture are self-evident, the only meanings that are evident at all are one's own!

Dr. Weiner has made his grasp and understanding of Foi meanings the cornerstone of this book. A fluent speaker of the Foi language, he is in every respect a superb fieldworker, and the high standards he has brought to the collection and translation of the myths are evident on every page. Those who are familiar with his personal circumstances, and who know something of the difficulties encountered in his field situation, will also know him as one of the most courageous anthropologists to have worked in Papua New Guinea. He is no stranger to the notion of obviation, and I remain very much indebted to him for the advice and insights he offered when I was working through the concept with a corpus of Daribi myths. Before I comment on his own subtle application of the idea, a few words are in order on its epistemological scope and implications.

If meaning were a self-evident property of things, a "given" of the world around us, then we would scarcely need an anthropology. We could make do well enough with museums, art objects, documentaries, and lavishly illustrated coffeetable books. But meaning is instead something that human beings learn—after the fashion of their cultures—to perceive in the happenings around them. It is a specialized form of perception, as is binocular vision, and it may even be related to the capacity for binocular vision. The forms in which this perception is elicited and encoded, trope in all of its identifiable varieties of metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, iconicity, might be said to project the "third dimension" of language and cultural convention, a dimension that is invisible to those who espouse the "flat" perspectives of systematic "rule" and process alone.

The problem is not so much that anthropology has been indifferent to meaning as that it has not known what to do with an allegedly static, subjective effect. And this is largely because trope itself, as the elicitor of meaning, has been understood as something detached and incidental—a by-blow of the businesslike logics that structuralism and semiotics use to model culture. But what if trope were, instead, a dynamic process, a constitutive principle that elicited not only the meanings but their sequence and organization as well? What obviation mod-

els is just such a processual form of trope, a sequence of contagious tropes that expand into the composite trope of a larger cultural frame—a myth or ritual.

As perception, of course, meaning remains as purely subjective and personal as the sense you or I make individually of a certain color or sound. What we can share of such an intimate experience (and what makes of such sharing a cultural phenomenon) is its conventional means of elicitation. Because it is the means by which personal perceptions can be shared and expanded into larger cultural forms, obviation is also a means of rendering the integral unity of cultural meanings accessible to us. Melanesians have always insisted on the central significance of certain myths and rituals for their way of life but, without a way of "reading" this significance in its totality, its indigenous sense could scarcely be grasped. Thus an approach to Foi sociality through myth becomes a privileged entrée to the meaning of Foi social life in its own terms, through the indigenous meanings rather than through the application of typological glosses.

Obviation is not a methodology, nor is it a recipe for myths. It comes into its own rift as a free form of interpretation, but precisely because of the constraints it places on interpretation. Diagrammatically it images the limits a myth places on the range of its possible interpretations. Add to this the conventions of a particular culture—those of exchange, the "fastening" of a woman, affinal protocols, the abia relationship, and the other usages that Dr. Weiner has learned so well—and the interpretive possibilities are further constrained by Foi culture. Using this coordinate set of constraints as a positive advantage, Dr. Weiner has managed, with suave dexterity, to elicit an indigenous commentary on social structure from Foi oral literature. What if pigs were substituted for affines, a man's bow or his fishing spear for his masculinity? What of the remarkable Foi practice whereby a man "adopts" his daughters' husbands by fostering their bridewealth payments? The implications of these "as ifs," in what Victor Turner called the cultural subjunctive, spell out an amazing Foi discourse on topics such as gender, relationship, mortality, destiny, autonomy, and personhood.

The cultural person contains implicitly the relationships that contain it; where else but in the mirroring dimension of myth can this reflexivity be articulated? And if it were not so articulated, then sociality could not enter the world of personal meaning, and would represent a merely imposed arbitrage.

What are pearl shells without people, without the person? The mag-

nificent Foi myth tells us that the heart of the pearl shell is blowing in the wind, streaming beneath running water. It is motion without substance, just as life would be if people did not imbue this motion with their lives, their wishes, their own thoughts. Pearl shells carries human life and human destiny on its wings because it has a place in human thoughts, human meanings and emotions, and in the person.

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA

ROY WAGNER

Acknowledgments

This book is a revised version of my doctoral dissertation, completed while a Research Scholar in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. My fieldwork among the Foi took place between July 1979 and May 1981, December 1982 and February 1983, and November 1984 and January 1985. It was funded primarily by an Australian National University Research Scholarship. My third field trip was partially subsidized by a small grant from the Southern Highlands Province Department of Education.

There are many people whose instruction, encouragement, and friendship made my work possible. My debt to Dr. Roy Wagner is profound and needs no special elaboration since his theoretical influence is evident throughout this book. He supervised my Master's work during my first year of graduate study at Northwestern University in 1973-1974. During that year, following Dr. Wagner's timely advice, my interest shifted away from economic anthropology and West Africa to kinship and social structure in interior New Guinea. At the end of that year, Dr. Wagner suggested that I enter the doctoral program at the University of Chicago, and I joined the anthropology department there the following year.

Over the next five years I was fortunate enough to continue my studies at Chicago under the supervision of Marshall Sahlins and the other members of my academic committee, David Schneider, Nancy Munn, and Valerio Valeri. Along with Dr. Wagner and Dr. Raymond

C. Kelly, these people are responsible for the theoretical background of this thesis. For their training and experience I would like to express my deepest gratitude.

Because of difficulties in obtaining financial support for my proposed fieldwork, I left the University of Chicago to accept a research scholarship in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University in 1979. With the advice of my supervisors, Michael Young, Marie Reay, and James Fox, I went to the Southern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea to live among the Foi-speakers of the Lake Kutubu area.

While in the Southern Highlands I was greatly assisted by Dr. Lyn Clarke, who was then chairperson of the Provincial Research Committee and expedited my entry into the field. To those friends who occasionally saw me in Mendi, the provincial capital—Bruce French, Dinah Gibbs, John Millar, Eileen Sowerby, and Robert Crittendon—and to Gregory Tuma and Simon Kowi who were members of the government staff at Pimaga Patrol Post from where the Foi were administered, I offer my thanks for their hospitality and continuing interest in my work.

After I settled in Hegeso Village in a comfortable house on the bank of the Faya'a Creek, I began what proved to be over two years of a most intense and satisfying personal involvement with that community. Most of my data during the first year and a half of fieldwork were obtained in formal interview situations. I would spend most of the days visiting men and women in their homes and gardens and sago stands. Other time was spent with the several young men who undertook to teach me the Foi language. I accomplished this task primarily through transcribing and translating myths and other narrated speech. In the last twelve months of my fieldwork, however, I was able to follow conversations the Foi people held amongst themselves, and most of my material on observed social interactions was obtained during this phase of my time in Hegeso.

But whether it was sitting at a desk, on a tree stump in a garden, in the back of a canoe, or in people's houses and bush camps, Foi people with very little self-consciousness undertook to present their selves to me, which demanded a corresponding willingness on my part to fabricate for them an image of the Westerner and of my own self. In a very short time I realized that this process was continually at work no matter what the ostensible social context.

In one way or another, each of the 266 souls of Hegeso helped to

make my stay there a rewarding one, both emotionally and intellectually. I would like to single out, however, the following individuals: Viya Iritoro, who has grown from boyhood to married adulthood since I first arrived in Hegeso; Fo'awi Ku~ hu~ , who, sonless, adopted me during what proved to be the last years of his life, and who instructed me in the secret lore of the Usi cult and his own personal magic; Dabura Guni and his brother Horehabo, who both offered their complete personal loyalty and enthusiasm for my inquiries and who spent long hours with me in myth-telling and in the description of the healing cults; Kora Midibaru and Egadoba Yabokigi who acted as my translators, interpreters, and linguistic instructors until I learned the Foi language myself; Memene Abeabo, for his personal friendship and his precise knowledge of Hegeso genealogies which he shared with me; the women Gebo Tamani, Kunuhuaka Deya of Barutage, and Ibume Tari; Yaroge Kigiri, Iritoro Boyo, Dosabo Gu'uru of Fiwaga, Tirifa Tari, Midibaru Hamabo, Haganobo Wano of Barutage, and Fahaisabo Ya'uware and his brother Mabiba of Barutage who both excelled as myth-tellers. To these people and the entire village of Hegeso, I acknowledge an immense debt for their patience, friendship and support—a debt I can never repay adequately and which binds me yet to the dark forest and quiet rivers of the Upper Mubi Valley. I would also like to thank Murray Rule and Hector Hicks of the Asia Pacific Christian Mission for their hospitality and interest in my research.

During the writing of the original doctoral thesis I was aided greatly by the supervision of Dr. Michael Young, who was then working on his own manuscript on the social and personal uses of myth on Good-enough Island (his work appeared in 1983 as Magicians of Manumanua ). Dr. Young's careful attention and insightful criticism as well as our many conversations on mythic interpretation were crucial to the presentation of the argument in this book.

Although I had read Dr. Wagner's book Lethal Speech before I arrived in Australia in 1979, I did not think about the application of the concept of symbolic obviation to my own data on the Foi until well after I had returned to Canberra. While working through my notes on Foi bridewealth and mortuary exchanges, it occurred to me that obviation, as a central property of metaphor itself, could be applied to a wide range of semiotically based social processes apart from myth. The implication that myth and social process could thus be tied together within a unified theory of symbolization thus constituted the

framework within which I analyzed the relationship between the myths, spells, and poems and the social structural data which were the main subjects of my inquiries. Certain other properties of the six-staged obviational triad, including what Wagner calls axial encompassment, became apparent to me at the same time that Wagner was describing them in more detail in his recent book Symbols that Stand for Themselves . Without the many discussions we had concerning the mechanics of analogic transformation and the properties of obviational sequences themselves, this book could not have been written.

In addition to Dr. Young and Dr. Wagner, I would like to thank Dr. Marie Reay for her careful reading of and commentary on every chapter and her insistence upon a high level of stylistic performance. Dr. Andrew Strathern also followed the writing of the original thesis at every stage and is responsible for a great deal of my understanding of Foi society and my subsequent interpretations.

To my closest friends Wayne Warry and Leanne Greenwood, and to Mark Francillon, I offer my love and gratitude for their unquestioning devotion and for all the moments of joy and hardship, all equally precious, that we shared. To Martha Macintyre and Jadran Mimica, my deepest admiration for their professional competence and enthusiasm and my thanks for their friendship. To Charles Langlas, who worked among the Foi fourteen years before I arrived in Hegeso, my gratitude for his guidance, friendship, and hospitality.

Ann Buller and Ria Vandezandt looked after my needs while in the field, smoothed out many of the bumps of fieldwork and thesis writing, and finally typed both the original thesis and the manuscript of this book. To both of them go my great thanks for their loyalty and professional diligence. Marc Weiner, my brother, created the cover design and never flagged in his enthusiasm for my work.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this book to my parents, David and Barbara Weiner, for their complete faith in my work and their devotion to me during what has proven to be a long absence from home.

Orthography

The Foi language was first analyzed by the linguist-missionary Murray Rule. Along with his wife Joan Rule, he produced an unpublished grammar and dictionary of Foi during their stay at the Asia Pacific Christian Mission station at Inu, Lake Kutubu. I thus employ Rule's orthography (1977:8-10).

Consonants | ||||||

/b/ | [p] | WI<1> | /f/ | [f] | WI and WM | |

[b] | WM<2> | /v/ | [v] | WI and WM | ||

/t/ | [th ] | WI and WM | /s/ | [s[*] ] | before /a/ and /e/ | |

/d/ | [t] | WI | [s]<3> | before /i/, /o/, | ||

[d] | WM | /u/, WI, and WM | ||||

/k/ | [kx] | WI and WM | /h/ | [h] | WI and WM | |

/g/ | [k] | WI | / | [m] | WI and WM | |

m/ | ||||||

[g] | WM | |||||

/n/ | [n] | WI and WM | ||||

/r/ | [r] | WM only | ||||

/ | [w] | WI and WM | ||||

w/ | ||||||

/'/ | [?] | WM only | ||||

Vowels | ||||||

/a/ | [a] | before /a/, /e/, /o/ | /e~ / | [e~ ] | AP | |

syllable | /i/ | [i] | AP | |||

[L ^ ] | before /i/ and /u/, AP<4> | /i~ / | [i~ ] | AP | ||

/o/ | [o] | AP | ||||

/a~ / | [a~ ] | or [L ~^ ] as for /a/ above | /o~ / | /o~ / | AP | |

/e/ | [e] | AP | /u~ / | [u] | AP | |

/u~ / | [u~ ] | AP | ||||

In addition, there are two tonemes, high and low, that affect only a small number of word pairs, for example: hae~ , "egg, seed, fruit," and hae~, [high tone], "dog."

All Foi words in this book are italicized except for frequently used proper names such as Usane Habora and Usi (see chapters 3 and 4). Literal translations of Foi words and phrases appear within quotation marks (for example, gabe , "axe"). Where Foi concepts or discourse have received a more interpretive or analytical translation on my part, this is clearly indicated in the text.

Notes

1. WI = Word Initial

2. WM = Word Medial

3. Tongue slightly retroflex

4. AP = All Positions

Chapter I

Introduction

The best way I have found to define ethnographic interpretation is the classic analogy of three blind men attempting to describe an elephant by touch—one holding its trunk, one its tail, and the other its tusk. Different ethnographers see things different ways, and the contrasting subjective viewpoints of each fieldworker determine the nature of the resulting ethnographic portrait. We, as much as the people who are our subject matter, create the reality of social and cultural phenomena, for we too are acting "culturally" by doing anthropology.

While as outside observers we know this to be too self-evident to warrant extended argument, I feel at times that we lose sight of the fact that it is also true of the individuals who are our subjects. Perhaps it is because we do not appreciate them as individuals until well into our field stays that we tend to assume that their knowledge and information about their culture is more uniform than ours. And if such is not the case, as in societies with graded ritual knowledge, certainly it is assumed that their interpretive perspective, their general structural vantage point, is covalent. This is a function of our belief that cultures, particularly those of small-scale societies, can be typified by a single set of structured propositions.

But even if we grant that our subjects can have conflicting theories of their society—even, in other words, if we admit this second degree of interpretive relativity—few of us identify a third level of subjectivity, that of differentially constituted domains within a single culture. We may, it is true, scrupulously note that such-and-such an element

is given conflicting associations, names, values, meanings, or what have you, in different contexts. But having reached that point, many ethnographers feel compelled to identify one meaning, one value as the "real" one, while the others are "extensions," "figures of speech," or "inversions" or "transformations," as if the last two were necessary characteristics of culture and meaning itself.

The problem is most acute in the study of myth and its relationship to the rest of social and linguistic discourse. The examination of this relationship has been dominated for the last twenty years by structuralist approaches, in which oppositions pertaining to assumed objective phenomena—up versus down, male versus female, and so on—are inverted or transformed and then resynthesized. Myth therefore emerges as a "looking-glass" of reality, a reflection of real life, a derivative semantic form; in brief, an extension of primary cultural meanings.

It is no surprise that the analysis of myth has been most commonly and closely associated with that of ritual for, like the former, ritual too is often interpreted as a topsy-turvy world of inversion, an inside-out morality. And yet, enthographers always seek in myth and ritual the semantic equations that are the missing links in completing the structures of secular institutions. Must we then conclude, paradoxically, that it is only by subverting the semiotic and symbolic foundations of secular life that their integrity and moral force are maintained?

This dilemma can be sidestepped, however, by a symbolic anthropology that takes the distinction between the "factual" and the "representational" as itself a symbolic construction, one whose parameters must be determined by observation and analysis in each society, rather than assumed as self-evident. My aim in this book is to constitute the dimensions of Foi sociality out of the images presented in their myths and their secular institutions, to demonstrate the role of each in the elaboration of the central Foi tenets of intersexual and affinal mediation, and to express the force of these principles in terms of how the opposed functions of conventional and innovative symbolization are given shape in Foi thought.

How, first, do I define sociality ? Rather than approach separately the phenomena that many anthropologists have distinctly defined as, for example, "culture" and "social structure," I wish to begin with the notion of a single domain of socially apprehended reality which

is simultaneously conceptual and phenomenal. Roy Wagner in his book The Invention of Culture thus defines as convention

the range of . . . contexts . . . centered around a generalized image of man and human interpersonal relationships. . . . These contexts define and create a meaning for human existence . . . by providing a collective relational base. (1975:40)

Clifford Geertz (1973), in speculating on the origin of the Balinese person, similarly notes that "human thought is consummately social" in its origin, functions, forms, and applications. These interpretations ultimately owe their inspiration to the father of social anthropology, Émile Durkheim, who first defined this set of shared concepts which simultaneously embodies ethos, world view, and collective solidarity as the field of morality (1966:398). Morality for Durkheim was the set of collective representations that pertained to the cohesiveness of social units. I therefore define sociality as those symbolic domains that constitute the collective image of human interaction in any society. These domains provide the conceptual parameters for the definition of individual and social units and their interrelationship (see also Schneider 1965).

Many social anthropologists, however, begin with the notion of the irreducibility of the biogenetic facts of human reproduction. The functional relationship between such facts and the institutionalized means of ordering and expressing them—rules of marriage, recruitment, and descent for example—is, by similar reasoning, assumed to be universal in all human societies. Radcliffe-Brown, who was social anthropology's most important interpreter of Durkheim, started with this premise in distinguishing social structure from other cultural institutions (Radcliffe-Brown 1952). It is implicit in Lévi-Strauss' model of the "atom of kinship" (1967:29-53), which formed the basis of alliance theory, and in Fortes' ideas, which are the most representative of descent theory, even though these two schools of thought can be considered to represent diametrically opposed views of social structure (see Schneider 1965).

The point I wish to make, however, is that kinship and social-organizational rules are first and foremost a system of symbolically constituted meanings and that their relationship to genealogical parameters is problematic. The dimensions of social interaction and organization are therefore "contiguous with other realms of conceptualization" (Wagner 1977:627). I therefore use the word sociality to mean the culturally defined and symbolically ordered nature of social

phenomena. The meaningful attributes of sociality reside not only in the normative system of social rules but also in every other cultural domain; the manner in which the Foi and other peoples order and define their interpersonal and intergroup relationships must be related to the way they order their microcosm and macrocosm at the most inclusive level. The relationship of humans, for example, to the animals species, the spirits of the dead, and the cardinal and geographic orientations of their social space—these too partake of a similar symbolic constitution.

In much the same manner that Marcel Mauss in his classic essay The Gift described reciprocity as a "total social fact" in many archaic and non-Western societies (1954), I describe the domains of intersexual mediation (that is, pertaining to the relation between male and female) and affinal mediation as the most pervasive conceptual foundations of Foi sociality. The central role of gender differentiation "as a cultural system"—in Geertz's (1973) sense—in Melanesian societies has already been well documented (see chapter 3 below). However, in this book I have avoided the use of word gender with its implicit emphasis on sex roles in favor of a term that stresses the fact that for the Foi sexuality is a relationship, and that this relationship encompasses much more than the differentiation of men and women. Marilyn Strathern speaking from her experience among the Melpa people of the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea has in a similar vein argued that "the logic inherent in the way such notions [of male-ness and female-ness] are set up must be understood in relation to general values in the society" (1978:173). Thus, the relationship between male and female and between affines, though comprising distinct normative ideologies for the Foi, encompass one another at the conceptual level with which I am analytically concerned. As domains of extreme importance to the Foi, they inform a wide range of relationships and analogies within the Foi cosmos. It is through their myths that the Foi make explicit the relationship between these analogies.

But there is an important methodological distinction to be made at the outset. On the one hand, there is the normative relationship between the institution of myth-telling and other institutions of social discourse. On the other hand, there is the relationship between myth as a context for symbolic transformation and the symbolic operations in other social processes. I have restricted the focus of this book chiefly to the second of these analytical viewpoints.

Thus, although I preface my analysis of Foi mythology with a de-

scription of Foi social organization, the images emerging from myth analysis do not formally correspond to those that emerge from statistical or normative statements about social structure, since the two represent distinct analytical views.

In chapter 5, for example, I present an image of Foi social structure that explicates the relationship between contrasting properties of asymmetrical and symmetrical exchange in the bridewealth system. This analysis stems from the comparison of different kinds of data, primarily statistical and normative, and represents one view of Foi social process. But there is no a priori reason to expect myth to reflect the intersection of these principles in the same way. It is true that several Foi myths comment on the implications of direct exchange and others on the implications of affinal asymmetry, but it is only in the interests of a functionalist methodology that one would conclude that those myths are related to one another in some exclusive way.

But it is also true that it is one of the aims of this book to establish both how myths are related to each other and how they are related to social process. And so I now turn to a description of the kind of model I feel can answer these questions, a model pertaining to the symbolic foundations of sociality.

Anthropology has at its core a commitment to making the social component of human life visible and, in this interest, the whole idea of human sociality, since the time of Durkheim, has been taken for granted. But the necessity of sociality, and all the functions attributed to it, are themselves aspects of a complex metaphor by which we assimilate the different practices of our ethnographic subjects to our own model of society.

In this book I employ a model of symbolic analysis devised by Roy Wagner, depicted most clearly in his sequence of publications Habu (1972), The Invention of Culture (1975), "Analogic Kinship: A Daribi Example" (1977), and Lethal Speech (1978). It is one of my purposes in this introduction to explicate the relationship between the stages in a unified symbolic theory that these works represent, and to introduce how I have employed them in my description and analysis of Foi society.

Social anthropology is about relationships, although up until fairly recently, most anthropologists preferred to restrict the content of relationship in this context to that between persons. But I prefer to begin with a more basic and encompassing definition of relationship,

grounded in a semiotic approach to the conceptualization of the world, and so I start with the "atom" of relationship, the metaphor.

Although any linguistic phenomenon depends ultimately on the establishment of arbitrary relationships between signifiers and signifieds, I will defer discussion of such sign relationship for the moment and merely note that signs themselves are the building blocks of metaphors, or tropes, in Paul Ricouer's phrasing. Regardless of the taxonomic differences some authors specify for metaphor—metonymy, synecdoche, iconicity, rhetoric, and others—the crucial characteristic of a trope is that it is a relationship between two elements that are simultaneously similar and dissimilar. A symbolic operation that focuses on the similarity between elements in a tropic ("trope-ic") equation can be termed collectivizing symbolization, in Wagner's scheme, while the converse operation that takes the differences as the focus of intent can be labeled as differentiating symbolization.

Because the two properties of metaphor are in direct opposition, identity as against difference, they cannot simultaneously embody the context of human intention; they cannot at the same time manifest themselves in the act of metaphorization itself, lest the intent of the symbolic construction be compromised.

I now assume that the nature of any particular metaphorical relationship depends upon the relative emphasis of either its collectivizing or differentiating function at the expense of the other, and that this relative emphasis corresponds to the conventionally defined mode of human intention itself. As an example, let us consider the Foi metaphor of clan identity. Each Foi clan has an associated group of bird, animal, and vegetable species which ``stands for it" in a manner that anthropologists characteristically define as totemic. A member of the Momahu'u clan is thus for example represented by the Raggianna bird of paradise, the sena'a species of sugarcane, the Black Palm tree, and others. In fact, each Foi clan has "standing for it" an element or species in the garden vegetable, tree, fish, bird, marsupial, and wild vegetable domains, and perhaps others that I am unaware of—in other words, in every domain that the Foi see as comprising their cosmos, in all the spheres that together make up the Foi universe. A human differentiation—that between clans—differentiates species. To the extent that the distinction between the domains themselves is backgrounded , their congruent assimilation to one clan collectivizes this distinction: the difference between items in different domains (say, the Raggianna bird of paradise and Black Palm tree, both of which stand for the Mo-

mahu'u clan) is not as significant as the difference between elements within a domain (such as the Raggianna and the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, which stands for the So'onedobo clan). The relationship between the domains themselves represents a series of homologous distinctions-that between Foi clans—and in this sense every generic domain the Foi recognize "functions" to distinguish clans from each other. To the extent thus that the domains themselves stand in homologic relationship, in contrast to the analogous distinctions within each domain, then every Foi clan has an unlimited number of totems, every generic domain the Foi recognize can serve as a field of totemic differentiation .

Analogy is the background against which the Foi articulate the distinctions that are the focus of their social life, just as difference is the background against which Westerners impose the collectivities of family and kinspeople. The corresponding emphasis on differentiating and collectivizing symbolization respectively comprises the domain of convention for the Foi and for Westerners, and such a contrast deserves more detailed scrutiny.

In an analytic framework that takes social relationships themselves as the result of tropic construction, convention can only be defined in terms of its complementary aspect, innovation or invention. Let me return to the distinction between culture and social structure with which I began earlier, with the rules that many anthropologists elicit and which form the framework for their eventual description of the content of a particular culture. What is the ontological status, as it were, of these rules? Most, if not all, are direct results of the anthropologist's questioning. But how do these anthropologists conceive of the whole notion of "a rule" itself? Is it not a product of their own cultural milieu, Western society, which posits an external and artificially constructed social contract opposed to the individual? In such a milieu, rules are the focus of conscious human articulation, since they are designed to regulate and systematize an inherently chaotic and differentiated cosmos. Our view of social artifice basically derives from such early social philosophers as Thomas Locke: society is the systematic application of constraints upon the inherent willfulness of the self-contained individual. The meaning of all social and cultural forms—including myth—is thus above all else referrable to their function in maintaining societal order.

Convention in this worldview thus emerges as a result of progressive acts of collectivizing symbolization, focusing on the artificially imposed

similarities among elements and statuses to arrive at the occupational, educational, and geographic specializations (to name a few) that comprise our social categories and the system of laws, written and unwritten, that govern their relationship to each other. In such a system, the differences that are also a part of the metaphor of social identity are seen as innate or inherent; and indeed, the morality of convention lies in the fact that it is seen to accommodate and control such difference.

Any person assuming a social role—as husband, wife, employee, citizen, and so forth—metaphorizes that role to the extent that his idiosyncratic personality is seen as hampering or promoting his performance of that role. There are punctual employees, domineering bosses, neurotic housewives, "bad" children, and not even the most punctilious diplomat is a perfect follower of protocol. The dissonance we feel when our individual motivations clash with the expectations of our social roles is what we perceive as the resistance to artificially imposed behavioral strictures, but the resistance itself is a function of the relative weighting of collectivizing and differentiating symbolization in our cultural tradition.

It is thus evident that a social convention only achieves its force and reality through individuals who recognize that convention as playing some determinate role in their action and intention. The relationship between the individual and the social, then, is also a metaphor, for each individual approximates more or less the image of a social form or action. Thus Wagner writes:

Since . . . convention can only be sustained and carried forward by acts of invention, and since invention can only result in effective and meaningful expression when subject to the orientation of convention, neither can be regarded as a determinant. Both are equally involved in, and equally products of, the successive acts of combining and distinguishing cultural contexts that constitute man's social and individual life. (1975:78)

Let us now suppose an inverse situation. Let us imagine a world-view that takes human sociality, its "rules," as "given" or "innate," in the same way that we take the individual's idiosyncratic personality as given for the purposes of social analysis. In this worldview, the energies and forces maintaining that sociality are not distinct from those that "animate" the universe in general: the cycle of birth, growth, and decay; the similarity between animal and vegetable species; the giving of food and ceremonial gifts or prestations; the proliferation of household groups; in general, all the characteristics of the

kind of non-Western society that early anthropologists labeled as "animistic." It is not, however, humanity that is projected onto an inanimate nature—the people we are speaking of do not make that distinction—but rather the self-evident continuity of cosmic forces that is seen as also encompassing the force of human action.

The Foi live in such a world of immanent continuity and transcendent human intention. The resemblances between—indeed, the essential unity of—all the different human, animal, vegetable, meteorological, and other vitalities is for them "given" or part of the innate nature of things. The moral foundation of human action, that contrastive realm that they view in opposition to this given cosmic flow, is to halt, channel, or make distinctions in it for socially important purposes.

In this type of society, what the anthropologist perceives as social process, the flow of events, can perhaps best be rendered in terms of the replacement or substitution of tropes by other tropes. Because metaphor is self-signifying—because it encompasses its symbol and referent within a single construction—this succession of tropic differentiations creates its own context, "precipitating" convention (and making it visible to the anthropologist) by means of successive differentiations against it. To put it another way, convention becomes apprehendable as a felt resistance to the improvisatory and particularistic actions of individuals that are opposed to it. Thus, in chapter 5, I discuss the various affinal and maternal payments that devolve upon wife-takers subsequent to a betrothal. To the extent that betrothal payments, bridewealth, maternal payments, and the special exchanges between cross-cousins succeed each other, they serve to shift the focus of the initial affinal differentiation across generations. What emerges from—what is "precipitated" by—these exchanges is the conservation of male as against female lineality. I thus argue that intersexual and affinal mediation emerge as the chief modes of social differentiation for the Foi. They model the successive acts of differentiation from which result the categories of Foi social structure, and to characterize the content of Foi society, perhaps nothing more need be said than that it is the constant re-creation of male and female (re)productivity out of affinity and vice versa.

However, let us now recall that a metaphor, unlike a sign, is not an arbitrary relationship between elements. Because each element in a trope can equally serve as the context for the other's articulation, it follows that the relation between the collectivizing and differentiating functions of metaphor is relative —it is not fixed, as is the relation

between a sound image and its conceptual referent in a sign relationship. To return to my example of Foi totemic usages, people are divided into groups that are represented by various "natural" species. The relationship between person and totem is a metaphor that serves to both differentiate people from each other and to collectivize species from different series, depending upon one's point of view. If it is thus true that any metaphor encompasses this contrast between similarity and difference in a relative and not fixed manner, then the possibility exists of focusing on differentiation in a collectivizing tradition, or of focusing on collectivizing in a differentiating one in certain contexts .

In Wagner's terms, any symbolic operation that exposes the simultaneously differentiating and collectivizing modes of a tropic equation can be defined as obviation . In a tradition such as ours, which focuses on bringing individual variations in personality and temperament into conformity with a collectively defined social role, any act or role that is consciously articulated in contradistinction to these conventions obviates them. Artists, writers, musicians, and any other adherents of a contrastive "counterculture" innovate upon these conventions by locating the creative impetus of their identity in opposition to them. To the extent that they render apparent the symbolic operation that maintains the moral force of these conventions—the collectivizing operation that makes itself felt as morality—such differentiating acts extend their associations and attributes. Thus, for example, idioms used by black Americans, Hollywood scriptwriters, and so on, gradually achieve a widespread conventional meaning.

But in a tradition such as that of the Foi, where differentiation is convention, where the drawing of contrasts accounts for the shape of social action, then innovation results when such contrasts are collapsed, when the distinction between elements in a tropic construction is backgrounded to their similarity. This is the force of those nonconventional acts such as magic, oratory, naming, and cult activity, all of which I will discuss in ensuing chapters.

Obviation can be alternatively defined as the manner in which the realm of the innate and that of human responsibility come to stand for each other. In the collectivizing tradition of the West that I have been broadly characterizing, it emerges as a result of deliberate focus on differentiation. The emergence of women's political consciousness in recent times is a good example of this. The dilemma of the role of women in a traditionally male-dominated society was the effect of the disparity between their collectively defined status as free citizens in an

individualistic democracy and the subordination they were forced to contend with by virtue of a perceived "n??tural" or "innate" inferiority of women as opposed to men. Feminism is the attempt to make coherent the definition of femininity by opposing or differentiating women categorically against the rest of society, in the same manner as ethnic minorities have always done. The feminist movement thus attempts to phrase the individual relations between men and women in collective terms and, by thus supplanting an innate particularization with a conventionally imposed collectivization, they obviate the innateness of men's domination.

For the Foi, however, differentiation is the conventional mode of male-female relationship. Contrast and complementarity are the substance of a husband's and wife's relationship, the normative effect of which is to commute all of their interaction to the stylized exchange of male and female foodstuffs and the "work" of sexual intercourse and procreation (see chapter 3). But in the course of a marriage, as a young man perhaps attains high status, if his wife is successful in caring for pigs and gardens, if she provides generously for her husband's visitors and trade partners and in general supports her husband's efforts, she is said to become a "head-woman," like a male "head-man." Thus, the individual and particular characteristics of that marital union, normally backgrounded to the conventional contrast between men and women in general, achieves symbolic force, working to individuate that marriage against other unions.

Since I have chosen to phrase the content of social articulation in semiotic terms, it should be clear that the tropic basis of this articulation stands in an inverse relation to the other more widely accepted process of symbolic analysis, structuralism. But it should now be clear that structuralism is the other side of the coin of obviation. Without semantic reference, there could be no metaphor, but without the assimilation of context and referent that metaphor represents, structuralism could not establish its semantic equations between different domains.

Structural analysis is an excellent vehicle for elaborating collective symbolization; it is "imperialistic" in that it always incorporates equivalences into an expanding transcendent relationship. But it fails to deal with the converse, the manner in which metaphor "seals" itself, cuts itself off from further equivalence. It cannot, in other words, explain how the different elements that comprise its basic analogies became differentiated in the first place, preferring to see difference itself as

"self-evident." But I am interested in the way that metaphor creates, rather than merely reflects, reality.

The structural interrelatedness of cultural meanings I take for granted and not as something to be didactically construed in the course of analysis. Structural analysis is primarily concerned with demonstrating homologous relationships between various conceptual oppositions. As the French anthropologist Dan Sperber notes (1975:52), in this type of analysis the symbolic signifier is analytically detached from the signified element. The signifier does not in and of itself receive a symbolic interpretation, "but only in so far as it is opposed to at least one other element" (1975:52). It is the resulting oppositions that are interpreted, and moreover, in terms of a set of extracultural or universal "codes" as Lévi-Strauss calls them (1966:90-91 et passim): for example, the distinction between nature and culture, up and down, raw and cooked, and so on. In this manner it becomes possible to speak of a single set of codes that are variably and differentially expressed by particular oppositions from one society to another (see Leach 1974: chapters 3 and 4).

In chapters 5 and 6 of this book I take issue with this interpretation. What Lévi-Strauss offers is a theory about information: how different conceptual oppositions can serve as vehicles for the expression of universal codes whose meaning is self-evident. But information is not the same as meaning. The latter is purely relative, not absolute, and cannot be measured for knowledge content (see Wagner 1972b). Meaning, as I argue, results when the elements of conventional syntagmatic orders are inserted into nonconventional contexts. The resulting figurative or metaphoric expressions define at once both the particularizing nature of metaphor and its dependence upon conventional semantic or syntagmatic references for its innovative impact.

In Mythologiques , Lévi-Strauss traces the inversions and transformations in various "elementary" oppositions of the mythology of cultures throughout North and South America. His methodology is deliberately cross-cultural, being concerned with codes and information rather than meaning. Hence the structures that result from such comparison have no implications for describing any one particular society as a conceptual or symbolic totality. My approach stands in opposition to that of Lévi-Strauss: to see not only each society's mythology as a self-contained corpus, but each myth itself as a pristine and complete figurative construction in its own right, not comparable except at a purely formal level to myths of other societies. The structural inter-

relationships of inversion between Foi myths that I trace represent not the encoding of invariant oppositions but the figurative relationship of elements in a single metaphoric structure that encompasses a meaning only for that particular culture. Structure is thus the residuum of metaphor, for the myths must stand in some determinate relationship to conventional syntagmatic orders.

The relation between myths and their associated magic spells is a good example of the relative distinction between collectivizing and differentiating modes of symbolization, and hence between semantic (structural) and tropic (obviational) analysis. In fact, this relationship depicts most dearly the dialectical creation of individual and social identity for the Foi. At first, the relationship between myth as a context for metaphoric transformation and the same process in nonmythical discourse was elusive. It was only after months of fieldwork that I learned of the relationship between myth and the corpus of magical formula that the Foi call kusa . At least in theory, so Foi men told me, every magic spell has a myth associated with it. But because the spells themselves were jealously guarded personal property, their relationship to mythology only emerged intermittently.

While both rest on the force of tropic construction for their effectiveness, myth and magic occupy opposed discursive contexts. Myths are above all else for public narration; the longhouse is the most common and perhaps only socially approved setting for their telling. A magic spell, on the other hand, is individual property, and spoken to no other person, except in the act of its transfer for payment, like any other valuable.

The magic spell focuses on the deliberate articulation of a similarity; it is a collectivizing trope, stressing the resemblances between the two elements that form the point of transfer of a specific capacity or power. One might say that magic is the Foi's own form of structural analysis, drawing similarities between putatively distinct domains, articulating metaphor in its collectivizing mode and, in addition, having the function of transferring or focusing power between those domains. The myth, by contrast, achieves its moral force by differentiating a sequence of tropes from a conventional image of ordinary social discourse, revealing the conventional nature of this image itself, indeed, recreating it by a particular innovation or individual perspective on convention.

It only remains to introduce what I perceive as the particular con-

tent of the relation between semantic and tropic symbolization for the Foi. It represents itself as a distinction between secret and public knowledge, which is also the relationship between individual and collective identities.

Why is it that the notion of secrecy and secret knowledge seems to pervade non-Western societies? Like "magic" and "ritual" themselves, secrecy is an integral part of our received image of non-Western institutions and is characteristically reported to be a definitive aspect of magic and ritual themselves. Secrecy is often invoked as the means by which one segment of a society maintains a dominance over another: men over women; elder men over younger men; ritual and cult savants over uninitiated men, to take some examples. In such cases, the restrictive effects of secrecy are taken for granted, and secrecy's implications for characterizing tropic manipulation are subordinated to its function in maintaining societal integration.

But for the Foi, the notion of secrecy itself reveals the fundamental manner in which culture is articulated. For Foi men, the metaphoric equations that underlie the power of magic, cult, sorcery, and oratory are not consciously created , they are discovered . The equations exist by virtue of an undifferentiated cosmos that admits of the free transfer of qualities between domains. These equations only assume a role in maintaining personal power when they are hoarded or guarded by individual men, when their transcendent reality is harnessed to the maintenance of individual power and identity.

Like the flow of wealth objects and procreative potential which is an aspect of it, secrecy is the result of the interdicted flow of analogy or metaphor itself—indeed, the constraint and secrecy that accompanies betrothal and marriage arrangements among the Foi is rendered more intelligible in this light. They are part and parcel of a cultural tradition that takes differentiation and restriction as the domain of human intention and action.

Myth, then, becomes public precisely because its insights and equations are elusive, not baldly and syntagmatically stated as in a magic spell. Whereas a magic spell is hidden because of what it reveals, myths are revealed precisely because of what they hide: the creation of morality and human convention out of the particular actions and dilemmas of archetypal characters. It is up to the listener, Foi and anthropologist alike, to assimilate myth's intricate plots into a transcendent insight into the most important secret of all—the mystery of human sociality.

The sequence of chapters in this book reflects what I see as the progression of Wagner's ideas concerning metaphor and symbolic anthropology. Chapters 3 and 4 thus begin with metaphors themselves, the equations between space, time, and sexuality, and between people and wealth objects, which represent the idioms through which the Foi articulate their social distinctions. I locate the theoretical impetus for these chapters in Wagner's Habu (1972). Chapter 5 details these social distinctions and how they recreate the analogies between intersexual and affinal mediation, as well as that between the living and the dead. This analysis is informed by the analogic approach to kinship described in Wagner's 1977 article. That article can be seen to represent his earliest ideas on the subject of symbolic obviation, and I explain this in more detail using the Foi data in chapter 7.

Chapter 6 also takes Habu as its starting point. Whereas chapters 3 and 4 detail the nature of Foi metaphors themselves, chapter 6 concerns itself with how metaphors are substituted for each other in the structure of various forms of Foi discourse. Chapter 7 then begins with the idea that Wagner presents in Lethal Speech , that a myth is a single metaphor in the same way as a more specific equation such as "women are marsupials" is a metaphor, and that the successive substitution of tropes by other tropes results in the obviation sequences—large-scale metaphors—that myths represent. Chapters 8 through 11 present my own analysis of Foi mythology in terms of this process.

In the first half of this book, then, I thus describe Foi sociality in terms of a set of conventional idioms pertaining to intersexual and affinal mediation. For the Foi, the most important feature of their shared apperception is what I describe as a flow of vital energies, forces, and relationships. Their sociality is but one facet of a world-view that posits a sui generis moral force to such phenomena as, for example, the motion of water and celestial bodies, the growth and death of human beings, the separation of the living and the dead, and the distinct sexual properties of men and women. Individuals, by contrast, attempt to redirect, channel, and halt these continuous cosmological and social energies for moral purposes. Thus, for example, they manipulate wealth items so that the female procreative flow of life can be harnessed to the creation of male descent units; they engage in funeral ritual so that an artificial separation can be maintained between the living and the dead.

There is a parallel between the manner in which many social anthropologists analytically separate genealogical reference from the cul-

tural context of kinship and social relationships, and the manner in which structuralists such as Lévi-Strauss separate universal binary codes from mythopoeic metaphorization. In both cases the cultural meaning of social and mythical idioms is preempted in favor of one or another functional theory of signification.[1] The intent of this book is to take both the idioms of sociality and of myth as mutually defining—they metaphorize each other even as their respective conventional components are at the same time demarcated and contrasted.

Another way of putting this is to suggest that the many images of Foi domestic, social, and ceremonial activities depicted in myth are no less accurate a rendering of Foi "everyday life" than an observer's verbal narration of daily activity. Pictures, whether verbal or graphic, must be transmuted and shaped by interpretation and analysis for them to have meaning for us. In unfolding the images that the Foi use to narrate their myths, they present their own pictures of life, and the analysis I add to them only focuses attention on the moral import of the succession of these images.

The fact that social meanings are created as a result of a structured series of tropic substitutions does not preclude the possibility of contradiction or paradox between them; in fact, such contradiction is a necessary characteristic of any cultural system, as I suggested at the beginning of this chapter. An example of this, discussed in detail in chapter 3, concerns the paradox of what Foi men perceive as the extremely limited role they play in procreation and their necessity to maintain continuity in descent through males. Another example pertains to the simultaneously life-giving and lethal properties of female sexual and procreative substances. Still another centers upon the intersection of the opposed principles of consanguinity and affinity within the Foi cross-cousin relationship. In the second half of this book I attempt to describe Foi mythology as the poetic or aesthetic revelation of these and other fundamental paradoxes. If these contradictions were made visible in everyday social process, the intention of Foi actors would be irreparably compromised. It is necessary, for example, for Foi men to mask the fact that women are dangerous to them (in order that they may engage in normal sexual activity); or for cross-cousins to ignore the fact that they are consanguines (so that they may engage in certain affinal exchanges). Culture must remain "open" so that people may live in it; myth and story provide the "closures"—cosmologically and morally—that ordinary life does not permit. Myth provides a transient, fleeting, and incomplete structure

for those people whose reality it encompasses. The anthropologist is obliged by the constraints of interpretation to freeze this temporary insight into a systematic model of thought and culture.

Chapter II

The Ethnographic Setting

The People of the Above

The Foi number approximately 4500[1] and inhabit the broad valley of the Mubi River and the area to the east of Lake Kutubu, near the border of the Southern Highlands and Gulf Provinces of Papua New Guinea. The Mubi originates in the high-altitude country south of Mt. Kerewa, approximately twenty-five kilometers north of Lake Kutubu, and flows from northwest to southeast into the Kikori River (which the Foi call the Giko). Near Harabuyu village, east of Orokana mission station, it merges with the Wage River which flows into it from the north. The Mubi is also fed by the Soro River which empties from the north end of Lake Kutubu and flows southeast past the lake, parallel to the Mubi and merging with it about nineteen kilometers south of Orokana.

The altitude of the Mubi Valley ranges between 750 and 800 meters in its upper portion and drops to less than 100 meters at the point where it flows into the Kikori. The Valley is abruptly separated from the Wage River valley to the north by a range of mountains between 1400 and 1600 meters high, the Tida and Masina Ranges, and is similarly separated by a parallel ridge of lower hills to the south—the Kube Kabe and Harutami Ranges—from the interior lowlands of the Kikori basin. The entire region between the Wage and Kikori Rivers represents a series of parallel synclinal valleys and anticlinal ridges of

karstified limestone (see Brown and Robinson 1977:4) which is covered by montane rainforest in the higher altitude and by mixed sago—pandanus—Campnosperma lowland rainforest in the Mubi and Kikori Valleys (see Paijmans 1976: part 2).

The Foi are separated from their closest neighbors on all sides by large tracts of uninhabited bush. All Foi villages are located on the Mubi River or around the shores of Lake Kutubu, and the area to the north of the Mubi is used only for hunting expeditions. To the east, the Mubi is separated from the westernmost reaches of the Erave River (a tributary of the Purari) by the Go'oma River valley. Up until approximately twenty years ago, this area was inhabited by several small longhouses of Kewa-speakers from the east who had fled their homes after defeat in warfare. They were given land and political asylum by the Foi men of Kaffa and eventually left the Go'oma River entirely and settled in the southern Foi area and later with the men of Harabuyu and Yomaisi villages (Patrol Report No. 2 1955-1956; Patrol Report No. 2 1961-1962).

The Foi view themselves as comprising three main subdivisions (see Map 1). Those inhabitants of the four Lake Kutubu villages are known as the Gurubumena, "Kutubu people," or Ibumena, "lake people." Those Foi living along the Upper Mubi River are called the Awamena, "above people" or "northern people." Those Foi of the southern Mubi are the true Foi people, the Foimena. All three populations refer to their language as Foime , "Foi speech," despite minor dialectical differences. Murray and Joan Rule, the linguists who initially described and analysed the language, used the term Foi to refer to all people speaking this language, and their designation has been adopted by the Foi themselves.

The Mubi Valley occupies an intermediate position between the Highlands and Lowlands in every sense of the term—ecologically, geographically, and culturally. Along the Upper Mubi, the Awamena maintain intimate trading relations with the Kewa- and Wola-speaking groups of the Nembi River region, the Sugu Valley, and as far as Kagua and Nipa stations. The Foi collectively designate all Highlanders by the term Weyamo or Fahai . The Southern or Lower Foi by contrast maintain trading links with those groups living south of the Kikori River, now known as Kasere or Some (see Franklin and Voorhoeve 1973) and who the Foi themselves call Kewa.

The pronounced ecological and ethnic differences between the Mubi Valley and the Highlands region north of the Tida and Masina Ranges

Map 1.

The Foi and Neighboring Peoples

are translated by the Foi and Wola-Kewa respectively as a set of cultural and environmental stereotypes each group has of the other. The Foi point out the Highlanders' hirsuteness, their distinctive woven pubic sporrans, grass-roofed houses built right on the ground, their countryside consisting of much secondary grassland and casuarina groves, their skills at hunting, and their aggressive, argumentative personality as the defining features of that cultural region. The Highlanders in turn peer down into the mist-shrouded Mubi Valley and see it as a place of unremitting sickness and frightening monsters, and the Foi themselves as uncanny sorcerers and cannibals. These stereotypes seem to typify interethnic relationships between Highlanders and Lowlanders all along the interface of the southern edge of the Highlands cordillera. The Hull of the Tari region fear the sorcery and cannibalism of the Etoro further south, with whom they trade (Kelly 1977:15-16). The Chimbu-speakers of central Simbu Province for precisely the same reason fear the Mikaruan-speaking Daribi of the low-lying Karimui Plateau to the south (R. Hide, personal communication).

Southwest of Lake Kutubu in the area between the Lake and the upper portions of the Kikori River (called the Hegigio at this point) is the territory of the Namu Po people who are known as the Fasu. They are the most closely related people to the Foi culturally and linguistically. Across the Hegigio on the west bank are located the groups of the Mount Bosavi area with whom the Foi of Lake Kutubu have regular but infrequent contact and whom they collectively term the Kasua. Southeast of the Foi in the vicinity of Mount Murray live the Samberigi, speakers of the Sau language (see Franklin and Voorhoeve 1973). The Lower Foi traditionally had contact with these people and called the area Foraba. The Upper Mubi people consider the Foraba region as the source of their most important traditional healing cults, primarily Usi, as well as the direction from which the Campnosperma brevipetiolata (Foi: kara'o ) oil tree was originally introduced to the Foi by the two mythical ancestresses, Verome and Sosame.

Linguistically, the Foi language has been classified by Franklin and Voorhoeve (1973) as belonging to the East Kutubuan Family of the Kutubuan Language Stock (located within the Central and South New Guinea—Kutubuan Super-Stock of the Trans—New Guinea Phylum [Wurm 1978]). The West Kutubuan Family includes Fasu, Some (Kasere), and Namumi. Linguistically and culturally, the Fasu have as many affinities with the groups of the Mount Bosavi area as they do with the Foi, and they can be considered middlemen in the borrowing

of cultural traits from Mount Bosavi. The Foi of the Lake Kutubu villages, the Gurubumena, obtained from the Fasu the costume associated with the gisaro ceremony which Schieffelin (1976) describes as general to the Mount Bosavi area, and which the Foi and Fasu call kawari . They also performed the gisaro themselves and called the 'burning of the dancers' siri kebora ("resin burning; scar-making burning") after the tree-sap torches used. The siri kebora did not pass further east to the Awamena, although men of the Mubi villages occasionally participated in it as visitors to the Lake villagers' ceremonies. The Gurubumena also traditionally accepted Fasu immigrants into their villages and intermarried with Fasu. Two clans of Hegeso in fact trace their ultimate origin to Fasu territory, though their more immediate ancestors arrived at Hegeso from Yo'obo Village at Lake Kutubu where, in 1938, seven out of the eleven clans represented were of recent Fasu origin (Williams 1977:208).

Other cultural traits from the Mount Bosavi area were also adopted by the Gurubumena, including cannibalism and boys' initiation. The former was restricted to enemies slain in battle (cf. Kelly 1977:15). The practice of boys' initiation did not involve homosexual insemination as it did for the Mount Bosavi groups, although the Fasu traditionally practiced a modified form of it (in which the semen of older men was rubbed into the navels of immature initiates).

To the south, the Lower Foi maintain trade links with interior Gulf peoples such as the Kasere, from whom they obtain cowrie shell, and the Samberigi, from whom they traditionally obtained stone axes in addition to cowrie (Patrol Report No. 2 1939-1940). The most important trade links, however, are undoubtedly between the Foi and the much larger populations of the north. The Foi have always been producers of the oily sap of the kara'o tree, used by many Highlands peoples for decorative purposes. In return, the Foi receive shoats, pearl shells, and in pre-steel times stone axe blades and salt. As is the case with other groups with whom they have traditionally traded, the Foi have imported several cults and ceremonies from the Highlanders. Although it is no longer practiced, I suspect that the Ma'ame Gai~ cult was in fact the Timp Stone cult[2] of the Mendi and Nipa region (see Ryan 1961: chap. 9; Langlas, personal communication). In more recent times, the Foi have adopted the Mendi—Nipa Sa or Ya pork exchange, which they call Dawa . Unlike their own traditional Usane Habora pig-feast that was linked to the performance of certain healing rituals (see chapter 4), the Dawa is a purely "secular" ceremony for

the Foi. Its primary characteristic is the establishment of long-term rotating debts and credits in pork and shell valuables.

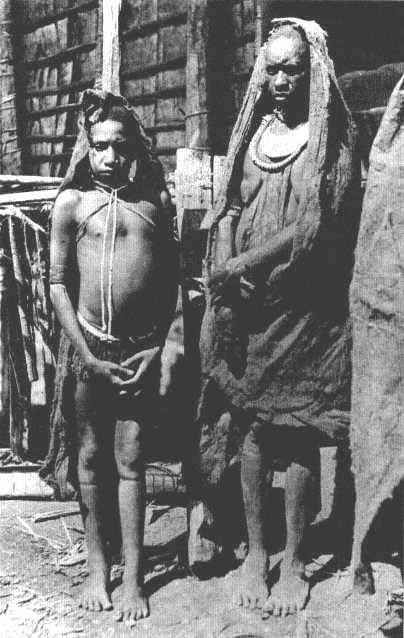

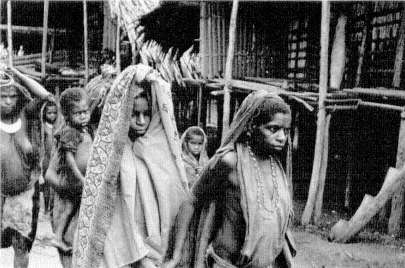

The residential unit of Foi society is the longhouse community (a hua , literally "house mother"). This consists of a central communal men's dwelling flanked by smaller individual women's houses on each side. The smallest such community was Kokiabo longhouse, inhabited by twelve adult men and their wives and children. The largest long-house was Damayu village with a total population of 306 in 1980. This seems to represent the upper limit of longhouse community population. Two communities—Wasemi and Barutage—divided in the recent past with one portion of each village building a new longhouse shortly after passing that limit. Hegeso had a population of 266 in 1980. At several times during my stay, men discussed the possibility of building a second longhouse that would have been used by men whose land was then at some distance from the existing longhouse.

The Hegeso men's house contains twenty-two fireplaces, eleven on each side of a central corridor, and each one nominally used by two men. The longhouse is 54.25 meters long and 7 meters wide. It is built 1.5 meters off the ground, and the peak of the roof is 4.5 meters from the floor. The women's houses (a kania ) are each approximately 8.5 meters long and 6.5 meters wide, and the height of the roof peak is a bit over 3 meters. Each longhouse has a cleared area in front and back called a wamo . The front of longhouse is that end which faces the Mubi River, conventionally designated the "upstream" (kore ) end. The back of the longhouse is "downstream" (ta'o ) and faces the bush (see figure 1).

In traditional times men built their longhouses on the tops of ridges or spurs for defensive purposes, preferably on a ridge at the river's edge so that only one end needed to be palisaded against attack. This remains the pattern today. The cleared area in which the houses are built is bordered by dense stands of multicolored cordyline shrubs and crotons (as are all dwellings) as well as pandanus, banana, hagenamo (Gnetum gnemon ), and other tree crops, and nowadays including orange, lemon, and tangerine. Each longhouse has its own canoe harbor (merabe ) along the Mubi or one of its tributaries.

Each men's house is associated politically and spatially with between two and four others which together form a distinct unit. F. E. Williams, the first anthropologist to work among Foi speakers in 1938-1939 called these units tribes (1977:171). Charles Langlas, who carried out anthropological fieldwork in Herebo Village in 1965 and

Figure 1.

Diagram of Longhouse and Women's House

1968 referred to them as regions. I have chosen to label them "extended communities." The Foi themselves lack a term to refer to these units generically but usually call each extended community by the name of one of its constituent longhouses. For example, Hegeso, Herebo, Barutage, and Baru longhouses are known as Herebo by outsiders. The four villages of Lake Kutubu are known simply as Gurubu by the eastern Foi. There are four other extended communities in the east and south.

Foi men say that these communities formed units in warfare in earlier times. While homicide and sorcery were not uncommon between coresidential men, formal warfare did not take place between longhouses of the same extended community. Likewise, these allied longhouses also comprise units in competitive feasting and exchange, and their constituent adult men consider themselves collectively responsible for amassing stocks of shell wealth and pigs for such ceremonial occasions (see also Weiner 1982b ). Foi men also recognize that each group of allied longhouses comprises an inmarrying community: Roughly half of all marriages take place between clan segments of the same longhouse, but less than 10 percent of all individuals, male and female, from an extended community marry outside of it.

History and Contact

The Australians first entered the Mubi Valley along its southernmost stretch. In 1910, M. Staniforth Smith led a patrol from Goaribari Island up the Kikori River.[3] The patrol reached Mount Murray by foot and crossed into Samberigi territory. It then continued along the Samberigi Creek in a northwesterly direction over several more arduous limestone ridges of the Murray Range. On the twenty-fourth of December, after a descent of 1200 feet, they arrived at a large river that "ran in a fierce rapid through converging mountains, forming a gorge 1200 feet deep. . .. The only conclusion we could come to was that this was the Strickland River." (Annual Report for 1911 :166). Smith later realized that he must have been in error and finally concluded that it was the Upper Kikori.

Smith and the expedition disappeared somewhere in the interior Gulf District along the Kikori, but Wilfred Beaver, who attempted to retrace Smith's journey the following year in the hopes of finding him, noted that it was in fact the lower Mubi River to which Smith had descended. On the twentieth of March, 1911, Beaver's party reached

Smith's No. Thirty-six camp, the last one they encountered. Beaver concluded that Smith had attempted his descent of the Kikori near that point, and he himself decided to descend the Mubi River, thinking it would flow into the Turama (Annual Report for 1911 :184). After encountering the same fierce rapids that Smith described, the patrol was forced to return to their Mubi camp on April 2 and return the way they had come. Beaver later became convinced that Smith and his party perished in an attack by "natives of the Kiko and others of the up-river tribes [presumably including the Foi]" (1911:178) somewhere along the river. However, on April 12 Beaver and his party learned from an officer who had come to meet them with fresh supplies that Smith and his group had arrived down the Kikori at Beaver's base camp (1911:185). In describing the rugged limestone country of the Lower Mubi and Upper Kikori, Beaver passionately wrote, "I can safely say, after an extensive experience of the roughest country throughout the Territory, that the portion traversed is the worst" (1911:186).

In 1923, Woodward and Saunders reached the Mubi in the course of their patrol through the Samberigi Valley (see Hope 1979: chap. 5). However, the Foi were not contacted again by the Australian administration until October 1926. In that month, a Kasere man arrived at Kikori station and reported that some Foi men under the leadership of one Poi-i-Mabu had crossed the Kikori River and raided the village of Sosogo, killing all of its inhabitants save for one adolescent boy. A punitive expedition was led by Sydney Chance, the assistant resident magistrate. He was, incidentally, the first white man to bring back a description of the waterfall that lies several miles above the confluence of the Mubi and Kikori, apparently the largest in Papua New Guinea (nearly 400 feet). Chance named it Beaver Falls after its discoverer (Annual Report for 1926-1927 :8).

The patrol followed Poi-i-Mabu and his associates who fled by canoe. For the next eight days the explorers traveled along the river and footpaths, confiscating canoes and eventually taking five prisoners at a village called Udukarua before returning to Kikori station. Chance also reported that most of the Foi men were in possession of steel axes that they obtained in trade from the Ikobi and Dikima (that is, Kasere) peoples south of the Kikori River.

This was the extent of European contact with the Foi for the next ten years. In early 1936, Ivan Champion made four reconnaissance flights over the area between latitude 5 degrees 50 minutes and 6 de-

grees 60 minutes and longitude 142 degrees and 144 degrees, the area between Mount Bosavi and Mount Giluwe, in the middle of which he viewed Lake Kutubu and the surrounding Upper Mubi River valley. Later that year, he and C. T. J. Adamson ascended the Bamu River and walked from Mount Bosavi to Lake Kutubu. They visited all five of the villages that existed at Lake Kutubu at the time but did not reach any of the Mubi River villages (Champion 1940). After crossing the lake, the party proceeded northeast across the Mubi and were shown a track leading across the Augu River and into the territory of Wola or Augu speakers.

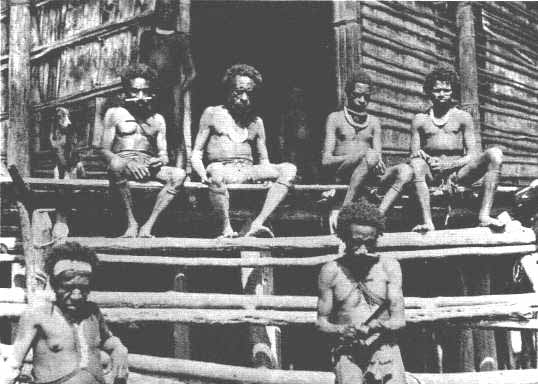

The next year, Champion and Adamson established a police camp at Lake Kutubu. Champion made a number of patrols over the next two years, primarily for the purposes of suppressing warfare. In July of 1939, the men of Ku~ hu~ , Era'ahu'u, Harabuyu, and Pu'uhu'u (that is, Tunuhu'u) villages raided Ifigi village, burning eight dwellings and destroying twenty-two canoes and twenty pigs (Patrol Report No. 2 1939-1940:1). A head-man of Ifigi named Baiga reported the attack and enlisted the aid of men from Hegeso, Barutage, Herebo, Harabuyu, Yomaisi, and Yomagi to retaliate against Ku~ hu~ . Fighting continued and twenty men from the Herebo extended community were wounded. Champion finally led an armed party to Harabuyu where there had been more killings the night before. The Harabuyu men were armed and their village barricaded. One of the constables fired his rifle and the Harabuyu men responded with arrows. Champion finally arrested the culprits and brought the prisoners back to Kutubu station.