III—

Speculum Manuscripts in Translation

Sometime in 1448, Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, a passionate lover of beautiful books like his great-uncles, Jean, Duke of Berry, and Charles V of France, commissioned Jean Miélot to translate the Speculum humanæ salvationis from Latin into French. During his reign (1419–1467) the library of the ducal court increased to the extent that its collection of manuscripts rivalled those of Pope Nicholas Vat Rome, of Cosimo de' Medici at Florence, and of Cardinal Bessarion at Venice.[1] He had inherited about two hundred and fifty manuscripts from his father, Jean the Fearless, according to an inventory dated 1420.[2] At the time of his own death, in 1467, he left to his son, Charles the Bold, some nine hundred manuscripts, as documented in another inventory.[3]

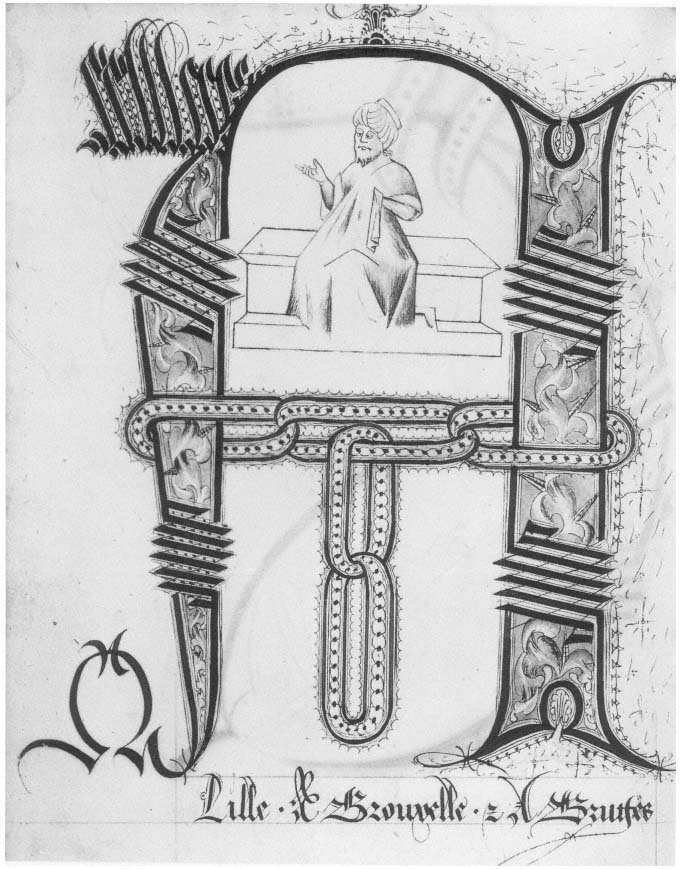

At his court he maintained scholars to compile books, scribes to copy them, translators, illuminators, and miniaturists. Among the scribes and translators the most prolific was Jean Miélot. To fulfill the order for translating the Speculum , Miélot prepared a dummy, or model book, on paper in folio size, written in his fine Gothic or Burgundian Bâtarde hand, and with sketches for most of the miniatures. He included fantastic decorated letters almost full-page size at the beginning and end of the manuscript, and illuminated capitals throughout the text.

This type of draft on paper, prepared to be presented and read aloud at court for the Duke's approval,[4] was called a minute , or model for a de luxe manuscript. If it was accepted, it would then be inscribed on vellum or parchment and illuminated with miniatures by professional artists. A number of minutes for fifteenth-century codices have survived and in the Bibliothèque Royale Albert I, in Brussels, is found Miélot's minute , entitled Le Miroir de la salvation humaine .

[1] La Librairie de Philippe le Bon , catalogue edited by Georges Dogaer and Marguerite Debae (Brussels, 1967), p. 3.

[2] Georges Doutrepont, Inventaire de la "Librairie" de Philippe le Bon, 1420 (Brussels, 1906).

[3] Joseph Barrois, Bibliothèque Prototypographique (Paris, 1830), p. 129.

[4] Anthony Hobson, Great Libraries (London and New York, 1970), p. 95.

Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 9249–50

The minute contains 112 leaves, 41 × 28.5 cm., with a text block of 29 × 19 cm., of twenty-two lines, on a fine sturdy paper.[5] It is handsomely encased in a modern binding of burgundy red leather, quarter-bound, with oak boards, and clasps in heavy brass.

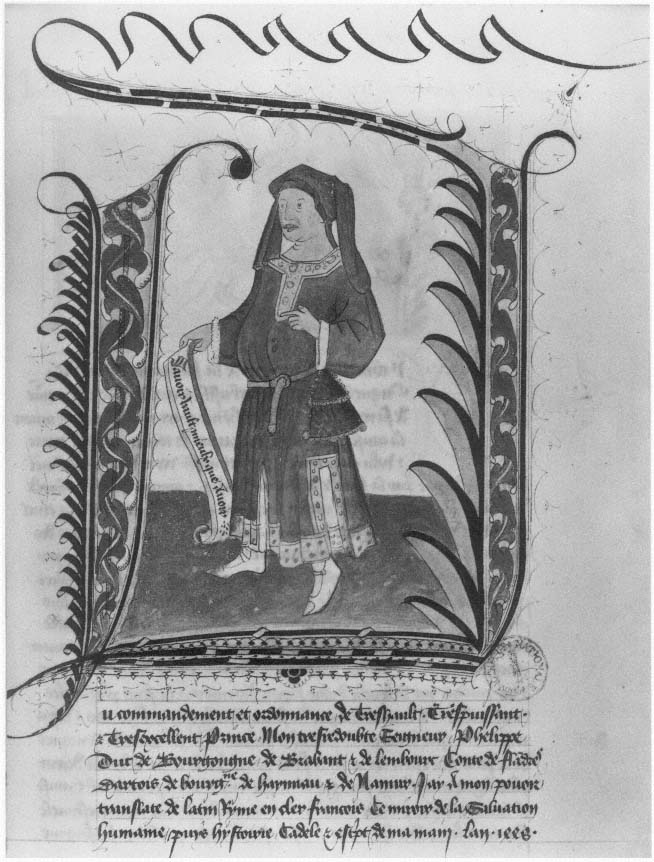

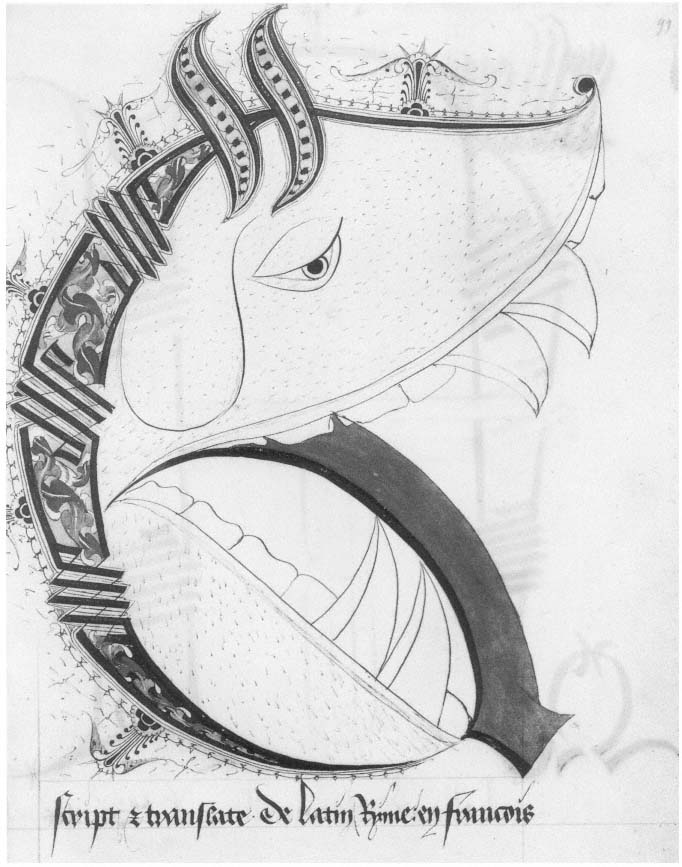

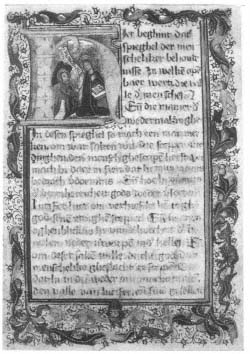

The first page displays a giant decorated M with a face on both sides, suggesting a mirror, over the letters I N U T E, each in a different style of capital (Plate III-3). The title page, on the verso (Plate III-4), is a full-page illuminated letter with a winged dragon forming an initial S above the calligraphed "Ensieut le miroir de la saluation humaine" (Here follows the mirror of human salvation). On the next recto Miélot describes the commission (fig. III-1). A large D encloses a modest self-portrait of the pot-bellied translator in a bejewelled robe. Miélot holds a banderole inscribed with the motto "Savoir Vault mieulx que Avoir" (To know is worth more than to have). Beneath is his text, translated as follows:

At the command and order of the very high, very powerful, very excellent prince, my most honorable lord Philip, Duke of Burgundy, of Brabant and of Limburg, Count of Flanders, of Artois, of Burgundy, of Hainaut and of Namur, I have to the best of my ability translated from rhymed Latin into clear French The Mirror of Human Salvation , then pictured, ornamented, decorated and written it in my hand. The year 1448.

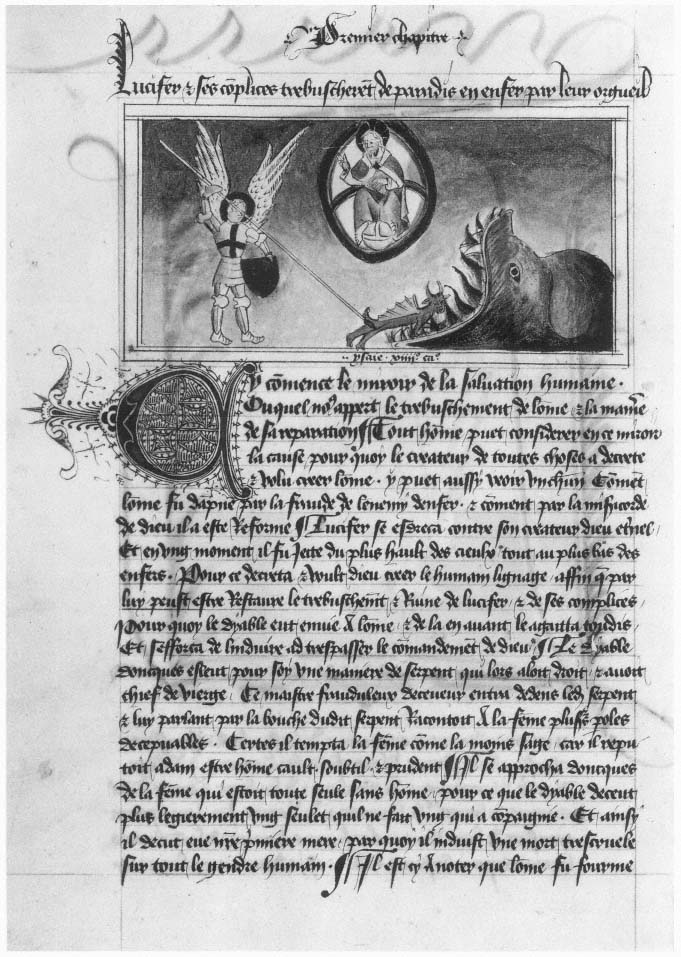

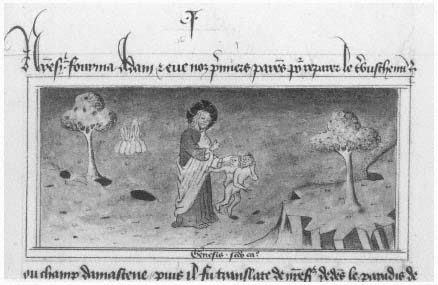

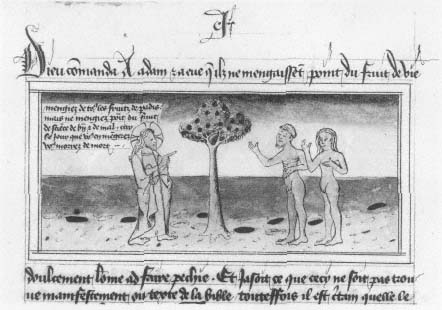

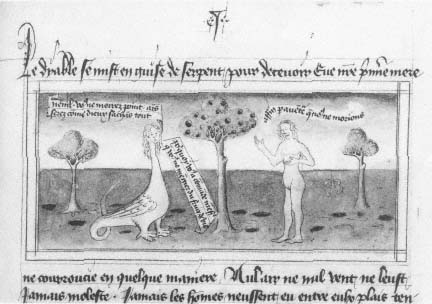

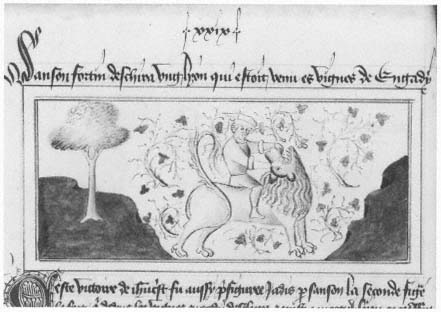

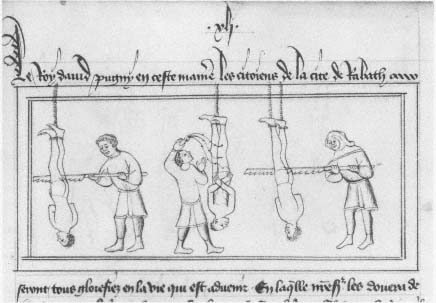

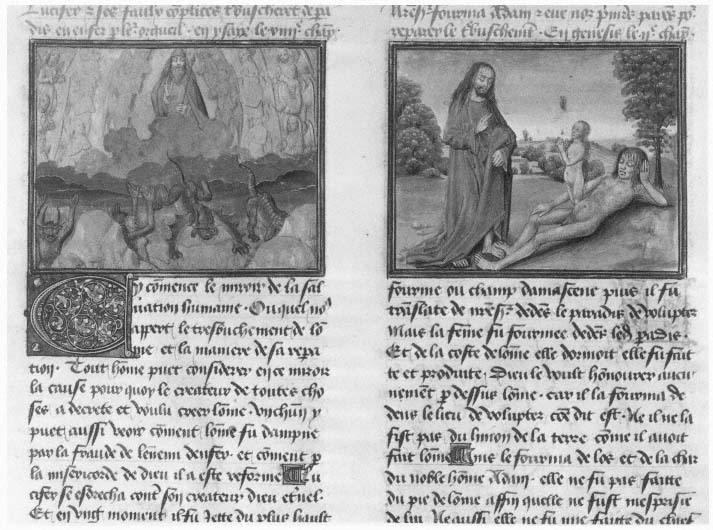

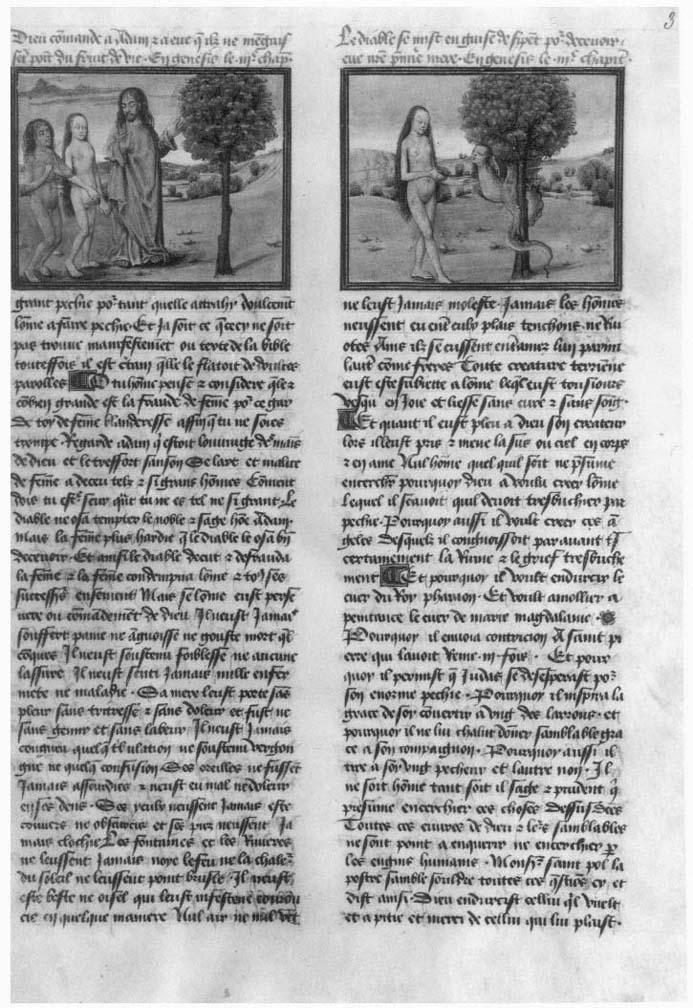

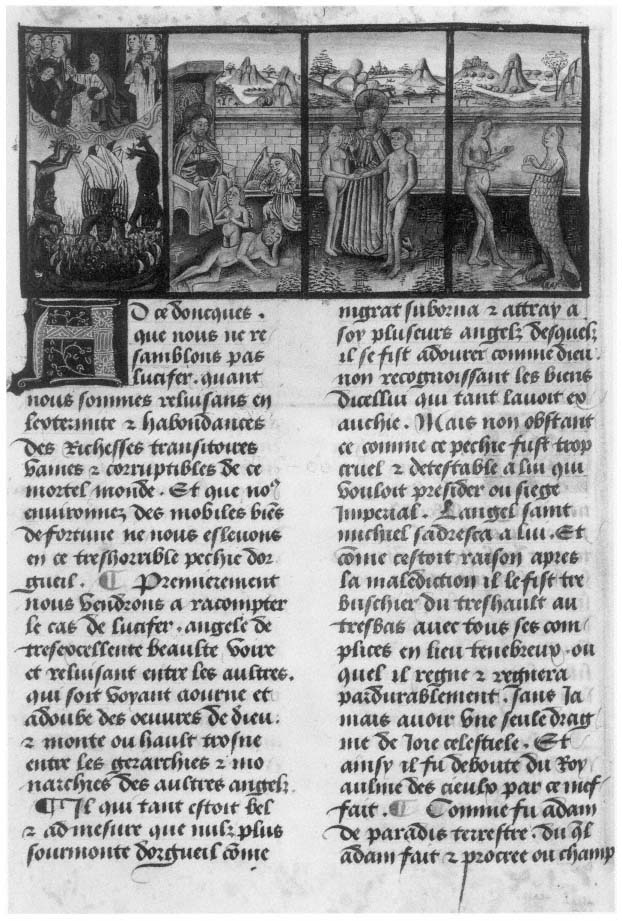

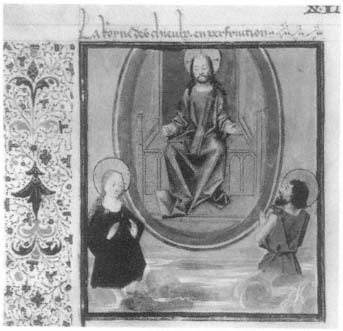

The text of the Speculum translation begins on folio 2 verso, below a miniature, and is written across the page in a single column (fig. III-2). The caption above the miniature explains the subject, the fall of Lucifer and his accomplices from Paradise into Hell because of their pride. The picture appears to be finished. Lucifer's accomplices are not depicted, God is seated in a mandorla in the heavens, and Lucifer is shown as a winged bull being prodded into the mouth of Hell by an armored angel. This miniature was probably not made by Miélot although he might have copied it from the Latin manuscript he was translating. The illustrations near the beginning have the base coat of paint (figs. III-3-a, b, c, and 4-a) but are unfinished. Later in the minute they are line drawings (figs. III-4-b and c). Beneath the first two are written the chapter and verse of the Bible to which the text and illustration refer, but this is not continued beyond Chapter I. Miélot was a good decorator, translator, and scribe, but he was not a miniaturist and if these sketches are his, they were intended to show the subjects to the artist.

[5] C. M. Briquet, Les Filigranes , edited by Allan Stevenson (Amsterdam, 1968), watermark 3544.

III-1.

Illuminated D with commission and date, 1448.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 2 recto.

III-2.

The Fall of Lucifer.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 2 verso.

III-3.

a. The Creation of Eve, fol. 3 recto.

b. The Admonition, fol. 3 verso.

c. The Temptation, fol. 4 recto.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50.

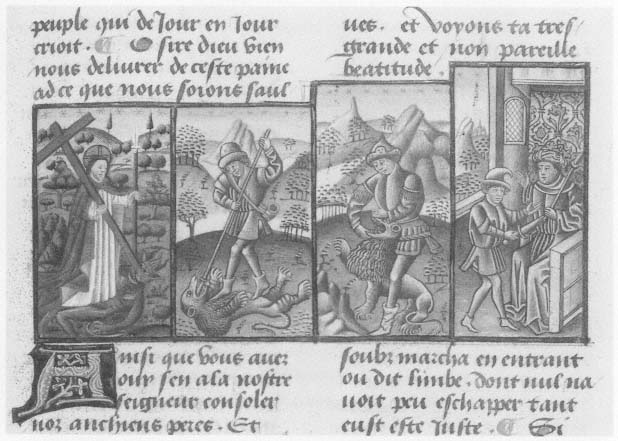

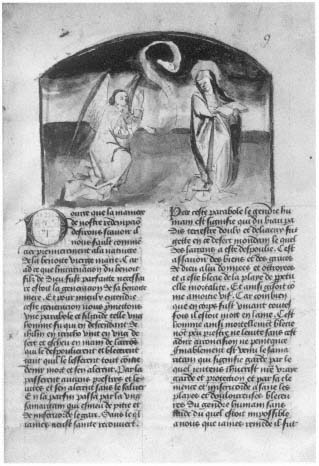

III-4.

a. Samson Rends the Lion Asunder, Chapter XXIX, fol. 59 verso.

b. The Sufferings of the Damned in Hell, Chapter XLI, fol. 82 verso.

c. How King David Punished his Enemies, Chapter XLI, fol. 83 recto.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50.

The end of the text of the translation is followed by three full-page decorated, colored and gilded initials, like those at the beginning. Folio 98 verso is a large decorated C enclosing another self-portrait of Miélot above the lettering "y fine le Miroir de la salvation humaine" (fig. III-5). In Middle French the word for "here" was "cy," not "ici." Facing the initial is a letter E in the form of a toothed dragon or sea monster, similar to the one shown as the mouth of Hell (figs. III-2 and 6 ) above the letters "script & translate de Latin Ryme en francois" on 99 recto.

On the verso is an A (for "at") with a crossbar and two hanging links of decorative chain over the words "Lille à Brouxelle et à Bruges" (fig. III-7). The Duke of Burgundy had courts in the three cities, and Miélot must have worked on his translation in the three places. Seated in the letter A, on a coffer, is a robed and turbaned man; possibly the chains refer to the capture of Christians by Moslems in the Holy Land, as Philip's father, Jean the Fearless, had been in the crusade of 1396. Philip is known to have planned a crusade and, in fact, it is recorded that, as a boy, he dressed in Turkish costume and wandered in the grounds of the ducal palace, perhaps plotting the future campaign.[6]

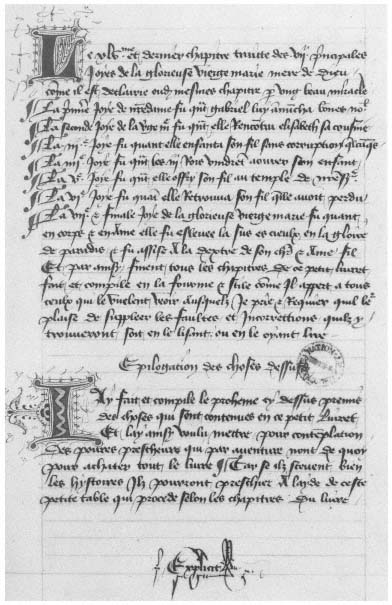

The manuscript ends with a Prohemium (fig. III-8) in which each of the forty-five chapters is summarized, followed by an Explicit entitled Epilogation des choses dessus (Epilogue of the matters above) which states, translated from the French:

I made and compiled the prohemium here above, explaining the things which are contained in this little booklet (ce petit livret). I have wished to do it for the contemplation of poor preachers who by chance do not have the means to buy the complete book. Because the stories are well-presented they will be able to preach with the aid of this little index which proceeds according to the chapters of the book.

Miélot finished his minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine in 1449 and it was in April of that year, probably as a result of the Duke of Burgundy's approval of it, that Miélot was attached to the Ducal court with regular wages. The archives show that the Duke reimbursed him rectroactively for the eighteen months he had worked on Ducal commissions before this, presumably including the preparation of the minute .[7]

In his manuscript of the Debat de noblesse , Miélot refers to himself as "indigne chanoine de St. Pierre de Lille et le moindre des secretaires dicelluy seigneur et prince" (humble canon of St. Pierre of Lille and the least of the secretaries of this lord and prince), but, in fact, he was one of the most educated, talented, and accomplished men in the service of the court, at once copyist, illuminator, historiographer, and translator.[8]

[6] Johanna Hintzen, De Kruistochtplannen van Philip den Goede (Rotterdam, 1918). See also Charles de Terlinden, "Les Origines religieuses et politiques de la Toison d'or," in Publications du Centre Européen d'Etudes Burgondo-Médianes, V (1963), pp. 35–46.

[7] Alexandre de Laborde, Histoire des Ducs de Bourgogne , I (Paris, 1849), p. 400.

[8] J. W. Bradley, A Dictionary of Miniaturists, Illuminators, Calligraphers and Copyists (New York, 1958), p. 324.

III-5.

The first page of Miélot's three-page colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 98 verso.

III-6.

The second page of Miélot's colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 99 recto.

III-7.

The final page of Miélot's illuminated colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 99 verso.

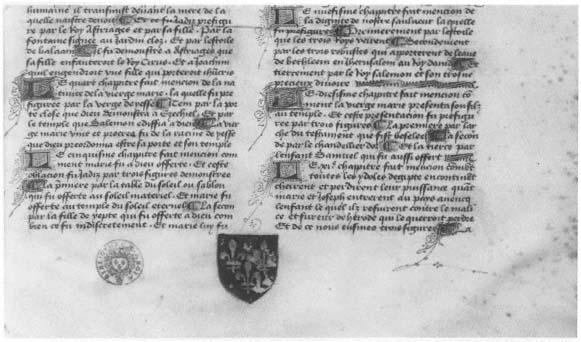

III-8.

The Explicit of the Prohemium.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels,

Ms. 9249–50, fol. 112 recto.

We find from the Explicit of the Traité de vieillesse et de jeunesse which he wrote at Lille in 1468, dedicated to Louis of Luxembourg, that he was born in a village in the bishopric of Amiens.[9] Nothing is known of his early life, but his education, both secular and religious, must have been thorough, for, in the archives of the church of St. Pierre at Lille, Miélot was entered as a Canon from 1453 to 1472. He was probably not required to remain in residence, but he exercised his canonical functions properly.[10] He was concurrently in the service of Philip the Good until the latter's death in 1467. Records show that he worked afterward for Louis of Luxembourg, Count of St. Pol, as well as for Charles the Bold, Philip's son and successor.[11]

[9] Lutz and Perdrizet, Speculum Humanæ Salvationis (Leipzig, 1907) Vol. I, p. 107.

[10] Ibid. , p. 108.

[11] Bradley, op.cit. , p. 325.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 6275

According to the 1967 exhibition catalogue, La Librairie de Philippe le Bon , the de luxe copy for which the minute was prepared has not been preserved, as noted above.[12] But in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 6275, a codex essentially ignored by scholars of Flemish illumination, there is an exact copy of the minute text. It is on vellum, 41×28.5 cm., (the same dimensions as the minute ), richly illuminated and with fine miniatures. The text, not in Miélot's hand, is inscribed in the format of the Latin manuscripts, two columns on each page with a miniature at the head of each, the facing pages containing a full chapter. On folio 2 recto appears "translate en prose par jo Miélot, l'an de grace mil CCCCXLIX," the same year that the minute was completed, which may indicate only that it was copied verbatim and possibly this copy was made much later, although it is also dedicated to Philip the Good.

Strangely, it is not one of the three French Speculum translations listed in the 1467 inventory, nor is the minute .[13] However, the 1967 exhibition catalogue states in the Introduction " . . . l'inventaire dressé après la mort de Philippe le Bon est imparfait: plusieurs manuscrits sont cités deux fois, d'autres ne le sont pas du tout" ( . . . the inventory drawn up after the death of Philip the Good is imperfect: several manuscripts are cited twice, others are not listed at all).[14]

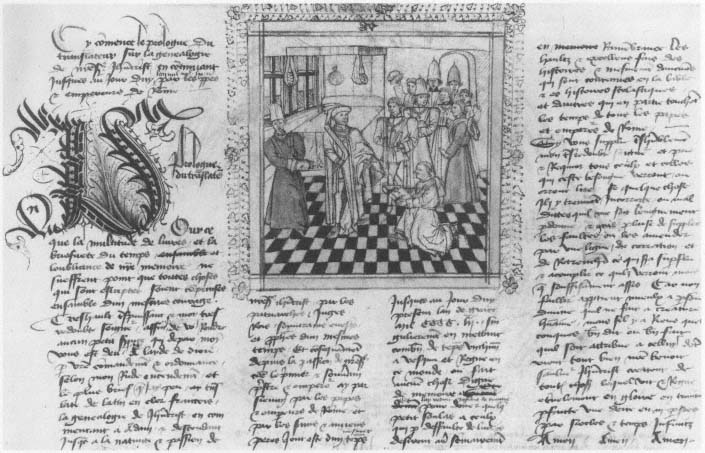

On folio 2 verso (Plate III-5) the text begins "Cy comence le prologue du Miroir de la saluation humaine translate de latin en cler francois." After a Latin sentence, a preface in French follows, but without a dedication to the patron. Above the text is a splendid miniature, the left half showing a Dominican friar seated at a lectern writing on a large sheet,[15] in a typical Flemish study within an architectural arch. Miélot mistakenly attributed the original manuscript to Vincent of Beauvais (1190–1264) and this is presumably meant to be a portrait of him. On the right side is a landscape with distant castles, a river, and trees, above which, in a great cloud, is a representation of God the Father holding in one hand three arrows and in the other a letter or contract with three seals appended.[16] Below at the left is a dark male figure representing Death. This miniature is presumably by a follower of Jean Le Tavernier in whose atelier the rest of the illustrations appear to have been made some years after the date in the text.

[12] La Librairie de Philippe le Bon, op. cit. , p. 14, Item 8.

[13] Barrois, op. cit. , p. 129.

[14] La Librairie de Philippe le Bon, op. cit. , p. 3.

[15] See Pieter F. J. Obbema, "Writing on Uncut Sheets," in Quaerendo, VIII, 4 (1978), pp. 337 ff.

[16] Perdrizet in his Etude describes this figure as the "Ancient of Days," crowned like the Vicar of Christ holding the very sharp arrows of the three scourges: war, pestilence, and famine. The parchment is a proper legal form by which God permits Death to decimate mankind by using the three arrows. There is a paragraph and a seal for each one.

On folio 1 verso and 2 recto there are two miniatures, one showing a group of men felling a tree (Christianity) from which each takes the part that fulfills his need: the swineherd takes the acorns, the carpenter the straight trunk, the fisher the curved branches for boat building, the writer gathers galls to make ink, etc. The other illustration shows five men with three documents with red seals appended. The Prologue states that Holy Scripture is like soft wax which takes the impress of any device, be it lion or eagle, and so one occurrence, in one connection, may prefigure Christ, and in another, the Devil.[17]

The final paragraph of the Prologue, on 2 recto, states:

Ci fine le prologue du miroir de beauvais de l'ordre des precheurs et maitre en theologie, jadis confesseur du roy de France monseigneur saint loys, fait et compila en latin rime par doublettes, leques a este depuis translate en prose par Jo Mielot, l'an de grace mil CCCCXLIX, en la fourme et stile qui s'ensui.

Here ends the prologue of the Mirror of Beauvais of the order of preachers and master in theology, formerly confessor to the King of France our sovereign Saint Louis, made and compiled in Latin rhymed couplets, which has since been translated into prose by Jo Miélot, the year of grace 1449, in the form and style which follows.

This Prologue is not to be confused with the Prohemium which, as in the minute , follows Chapter XLV. On folio 90 verso, preceding the Prohemium, is a miniature showing Miélot in his study copying the translation in two columns with the Latin two-column model held in his left hand. On a lectern and its bench are opened single-column books, perhaps his minute (fig. I-1). Below this is the statement erroneously crediting Vincent of Beauvais with the authorship of the original manuscript.

The miniatures throughout the manuscript, while not as exquisitely finished as those of the Prologue, are well composed, with strongly drawn figures, expressive faces, and fine landscape and architectural details. On the basis of the costumes and the relationship between the miniature of the Adoration of the Magi on folio 16v with the Adoration of Hugo van der Goes in Berlin, the miniatures were made sometime between 1485 and 1495.[18] The text corresponds throughout with that of the minute . See, for example, fig. III-2 compared with fig. III-9.

[17] M. R. James and Bernard Berenson, Speculum humanæ salvationis , p. 7, translation of the Prologue.

[18] These dates were suggested by Anne H. van Buren, Fine Arts Department, Tufts University, Boston.

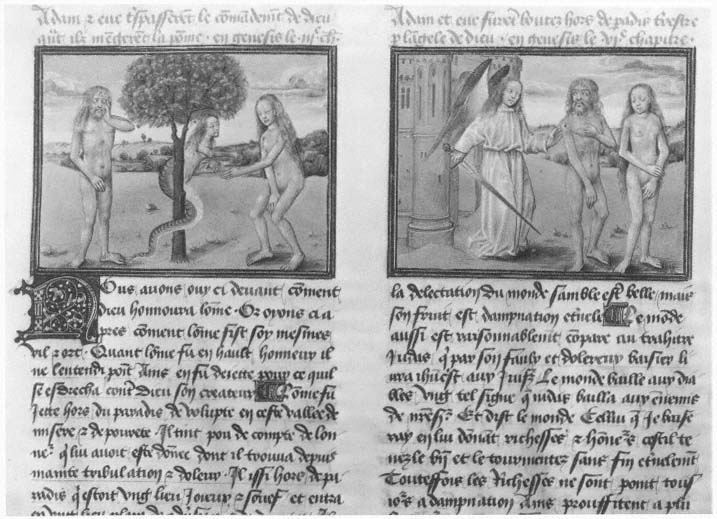

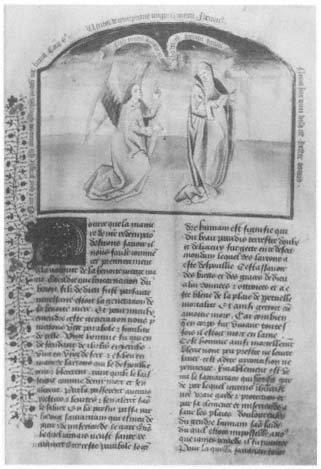

III-9.

a. The Fall of Lucifer.

b. The Creation of Eve.

Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 6275, fol. 2 verso.

III-10.

c. The Admonition.

d. The Temptation.

Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 6275, fol. 3 recto.

III-11.

a. The Fall of Adam and Eve.

b. The Expulsion from the Garden.

Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter II.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 6275, fol. 3 verso.

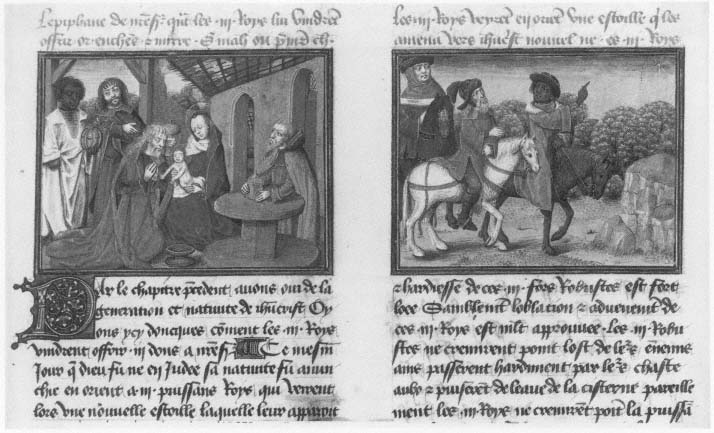

III-12.

a. The Adoration of the Magi.

b. The Magi See the Star.

Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter IX.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 6275, fol. 16 verso.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 17001

Miélot left a number of minutes for other translated texts, trial pages of his large illuminated initials, and verses and texts of his own composition which are bound together in Ms. fr. 17001. It is a folio volume of 116 pages on paper, 41 × 28.5 cm., a section of which has the same watermark as the minute of the Speculum .[19] Entirely in Miélot's hand, the drafts are from various dates up to 1470. Three major translations are included: L'Epistre de Cicéron à son frère Quintus; Briève compilation des histoires de toute la Bible ; and Histoire du mors de la pomme .[20]

The manuscript opens with a table of contents added by a later owner which omits many of the texts included in the volume. Folio 2 recto relates the legend, widely accepted in the Middle Ages, concerning the naming of Adam, which had an oriental origin as indicated by the Greek names of the four stars involved. Miélot relates that God sent the four archangels to the four corners of the earth, and they returned in succession with the initial letters of the stars they found there: Anatole, Disis, Arthos, Messembrios. Folio 2 verso is devoted to a large labyrinth or maze in which the letters M I E L O T may be found. A labyrinth of this sort appears in the pavement of the cathedral of Amiens, in which bishopric Miélot was born, and evidently provided inspiration for him. These elaborate paving mazes exist in the floors of many medieval churches and sometimes contain the name of the master designer.

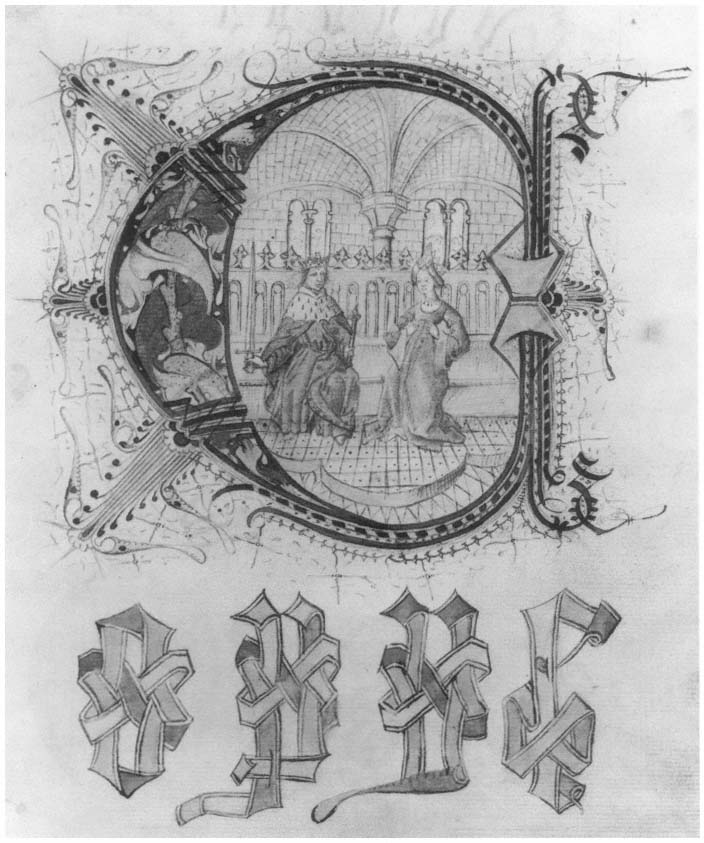

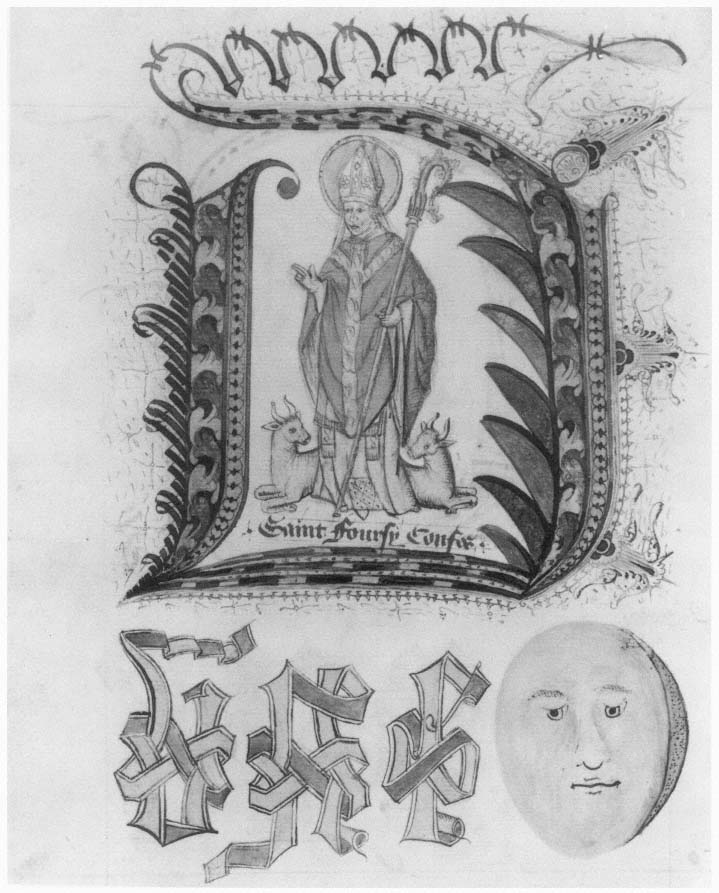

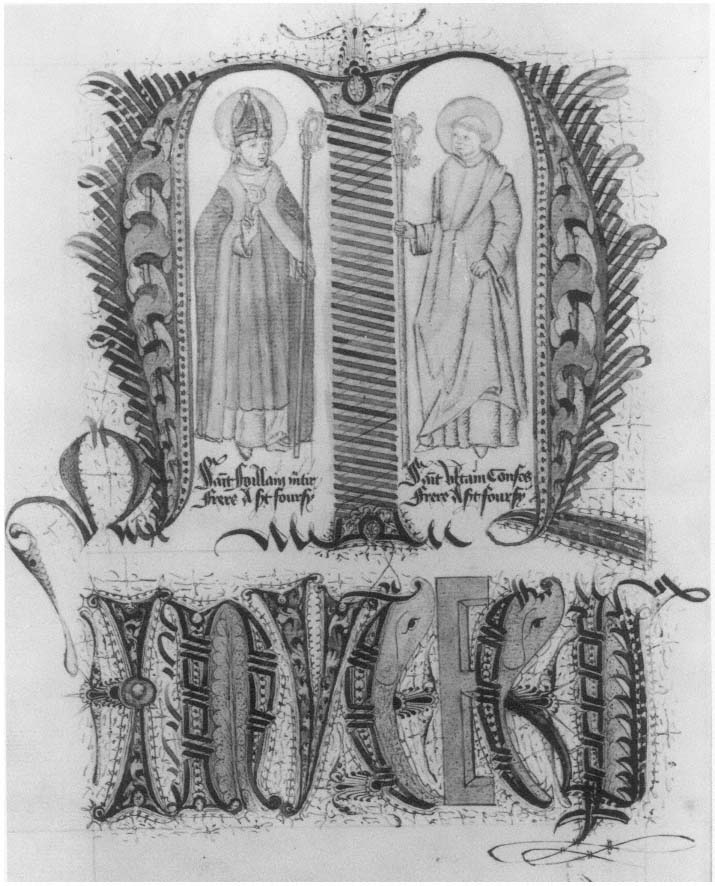

Folio 3 recto carries a large illuminated C (fig. III-13) enclosing a drawing of a lavishly robed king and a lady, in a vaulted room. Below are the letters O P Y E composed of strapwork bands, to spell "COPYE." On the verso (fig. III-14) is an equally elaborate large D framing a portrait of a bishop, inscribed at the base "Saint Foursy Confes." Below the illuminated D are the strapwork bands of the letters U N E, to spell "D'UNE" beside a plain moon face in the position of a following letter, the significance of which is mysterious.

There is a large illuminated M on 4 verso (fig. III-15) like that in the minute for the Miroir , decorated with spiral acanthus leaves. "Saint Foillain m(ar)tir, Frère a St. Foursy" appears in the left arch of the letter and "Saint Ultain, Confes., Frère a St. Foursy," in the right. Below are the illuminated letters I N U T E. The three pages together, with their fantastic graphic elaboration, simply spell "Copye d'une Minute." The last word ends with another illuminated E and a P, separated with fish motifs, which may have been done only to fill out the line.

[19] Briquet, op.cit. , watermark 3544; also found in B.N. Ms. fr. 17001 are watermarks 1739 and 1740.

[20] Robert Bossuat, "Jean Miélot, traducteur de Cicéron," in Bibliothèque de l'Ecole des Chartes, XCIX (1938).

III-13.

Historiated initial and strapwork letters for "COPYE."

Jean Miélot workbook.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 17001, fol. 3 recto.

III-14.

Historiated initial for "D'UNE."

Jean Miélot workbook.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 17001, fol. 3 verso.

III-15

Historiated initial for "MINUTE."

Jean Miélot workbook.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 17001, fol. 4 recto.

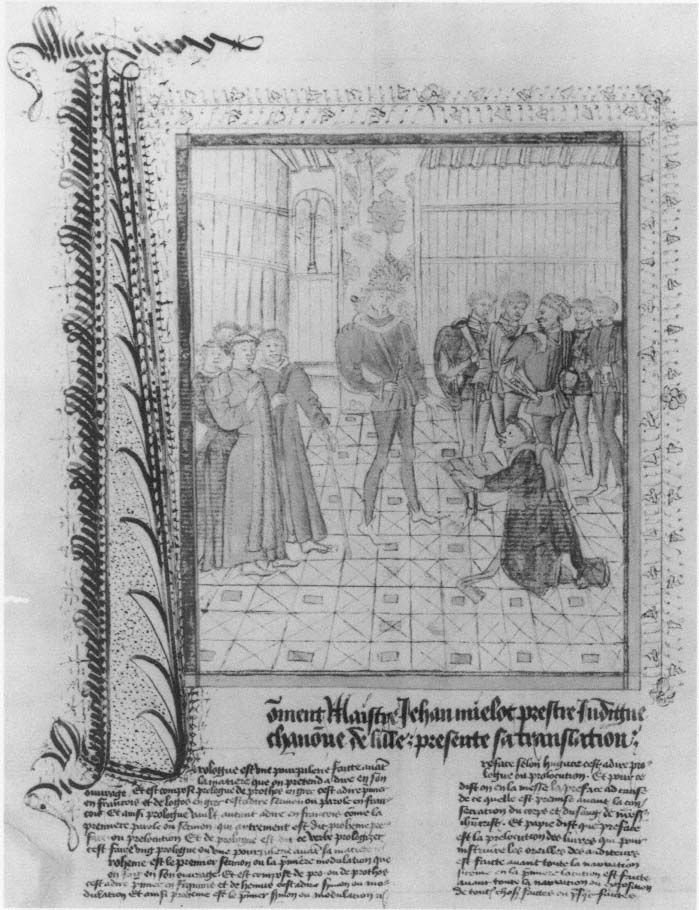

The sketch for an illustration on 5 verso (fig. III-16) shows an interior scene captioned "(C)oment Maistre Jehan mielot prestre Indigne chano(i)ne de lille: presente sa translation." The giant P at the left leads into the text which explains the functions of a prologue, a prohemium, and a preface, possibly a trial page for a de luxe manuscript.

The translation of the letter of Cicero to his brother Quintus follows on folios 8 to 25 and ends with "dans l'an mil CCCC, soixante huyt" (1468). A copy of this translation is preserved also in the Royal Library at Copenhagen.[21] On folio 26 recto is inscribed "Fait a Lille," on 26 verso "Par Moy" in illuminated capitals and letters, and on 27 recto appears another maze in a different form but again with the letters of Miélot's name inserted.

The workbook also contains a draft for the translation of the Briève compilation des histoires de toute la Bible from the Latin text of Jean d'Udine, which appears, as another minute on paper, in the Brussels Library, Ms. II 239 (fig. III-17). In both cases the text and the drawings are inscribed side-turned. The preliminary sketch for a schematic map follows, showing the division of the earth after the Deluge into the three continental sections for the sons of Noah. A more finished form is found in the same Brussels Ms. II 239, which also contains a Miélot drawing of a presentation, showing the Duke receiving the book in his bedchamber with clerics and courtiers in attendance and, on 54 verso, a genealogy of the Miélot family.

The last text in Ms. fr. 17001 is the Histoire du mors de la pomme , a sequence of dialogues in verse, possibly one of Miélot's rare attempts at authorship, with each page illustrated with crude line drawings. His listed works are almost entirely devoted to translations, edited versions, and transcriptions of the works of others.[22]

Two miniatures of a much later date appear on the last two pages of the volume. The first shows St. Luke at an easel, with his symbol, the ox, lying beside it and an angel behind him mixing ink or paint on a stone. At the left the Virgin Mary is posing for her portrait with book in hand. The pictures of the Virgin that St. Luke was said to have painted in the first century are all works of a much later date.[23] The second image is of St. Matthew writing in an open, bound book, while a kneeling angel, his symbol, holds out the pot of ink. Miélot may have copied these from admired models (fig. III-18).

A very revealing study could be made of the relationship of this manuscript to Brussels Ms. II 239 and the Copenhagen copy of the Cicero letter. In any case, Ms. fr. 17001 is of great interest in the study of the preparation and production of codices. It is a remarkable example of the workbook of a scribe, illuminator, and translator of the prolific Burgundian court.

[21] N. C. L. Abrahams, Description des manuscrits français du moyen âge de la Bibliothèque Royale de Copenhague (Copenhagen, 1844), p. 33.

[22] Lutz and Perdrizet, op.cit. , pp. 108–111; F. A. F. T. Reiffenberg, Bulletin du Bibliophile Belge , II (Brussels, 1867), p. 381.

[23] Donald Attwater, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (Harmondsworth, 1965), p. 223.

III-16.

Jean Miélot presents his translation to Philip the Good. Trial page.

Jean Miélot workbook.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 17001, fol. 5 verso.

III-17.

Briève compilation des histoires de toute la Bible .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. II 239, fol. 1 recto.

III-18.

The last two sketches in Miélot's workbook.

a. St. Luke painting a portrait of the Virgin Mary.

b. St. Matthew writing the Gospel.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 17001, fols. 115 verso and 116 recto.

The Hunterian Museum Library, University of Glasgow, Ms. 60

This de luxe manuscript is a French translation of the Speculum , entitled Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation . It was acquired by William Hunter's agent at the Gaignat sale held in Paris in 1769.[24] The Explicit states that it was written at Bruges in 1455. There are sixty-three folios of an original sixty-four, written on vellum, 30.3 × 21.6 cm. in two columns of thirty-seven lines, in a Burgundian Bâtarde. The text is continuous, but at the beginning of each of the forty-two chapters, wherever they fall on the page, there are four narrow adjoining miniatures, the one at the left in color and the other three in grisaille with touches of gold. The skies are deep blue, often with gold stars. All of the four images together are the width of the two columns but occasionally, although they have the same base line, the individual miniatures are made taller to fill in the blank space of the previous chapter ending. The chapter ending text is often carried from the left to the right column to provide a rectilinear area for the miniatures. These do not have captions or titles as do those of the Latin manuscripts and the other French translations. Each chapter text begins with a decorated initial.

On folio 1 (Plate III-1) is a page-width miniature of the scribe kneeling to present the volume to his patron, possibly Philip the Good. Beneath this is a Prologue with decorated margins above and below. Curiously, this text does not contain a dedication to the patron nor does it identify the translator as is so carefully done in the books of Miélot. In the miniature, the Duke is seated on a marble throne within a vaulted and columned structure open on all four sides. The proffered volume is richly bound in blue with gold clasps and bosses. At the left are two standing female figures. The nearest, representing the Synagogue, in accord with medieval symbolism, is blindfolded and has a crown toppling from her head. In her left hand she holds a broken standard with a pennant, and in her right, the Tables of the Law. Beside her a white-coifed nun representing the Church holds a standard bearing a cross, and in her other hand a golden Chalice and Host.[25] This miniature has been attributed to Willem Vrelant, and the remaining forty-two panels to his atelier.[26] We know from the list of guild members in Bruges[27] that in 1454 Vrelant was working there; according to some scholars he and his assistants produced more than all the other miniaturists of Bruges put together,[28] but currently there is some doubt about the very large oeuvre attributed to his atelier.

[24] Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of the Hunterian Museum in the University of Glasgow , edited by John Young and P. H. Aitken (Glasgow, 1908), p. 68.

[25] Ibid. , p. 69.

[26] For this information we are indebted to Jack Baldwin, Keeper of Special Collections, The Library, University of Glasgow.

[27] W. H. James Weale, "Documents inédits sur les enlumineurs de Bruges" in Le Beffroi, IV (1872–73), pp. 238 ff.

[28] L. M. J. Delaissé, A Century of Dutch Manuscript Illumination (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968), pp. 74, 77.

In the Hunterian Catalogue the translation is attributed to Jean Miélot, but it does not correspond to the wording of either Miélot's minute or to B.N. Ms. fr. 6275. Following the Prologue the text begins on folio 1 verso "Ad ce donques que nous ne resamblons pas Lucifer." This copy omits the last three chapters and the Prohemium of the Latin manuscripts. Chapter 42 ends on folio 61 verso with "le pere et le fils et le saint esperit amen," immediately followed by the Explicit (fig. III-19).

Et ainsi fine ce present proces du myroir de lumaine saluation fait & translate de latin en franchois a bruges lan de grace mil iiij & cinquante cincq.

And thus ends this present account of the mirror of human salvation, made and translated from Latin into French at Bruges, the year of grace 1455.

III-19.

The Explicit with the place and date.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation .

The Hunterian Museum Library, Glasgow, Ms. 60, fol. 61 verso.

III-20.

a. The Fall of Lucifer.

b. The Creation of Eve.

c. The Admonition.

d. The Temptation.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter I.

The Hunterian Museum Library, Glasgow, Ms. 60, fol. 1 verso.

III-21.

a. Christ Conquers the Devil.

b. Bananias Kills the Lion.

c. Samson Rends Asunder the Lion.

d. Ehud Pierces Eglon.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter XXIX.

The Hunterian Museum Library, Glasgow, Ms. 60, fol. 42 recto.

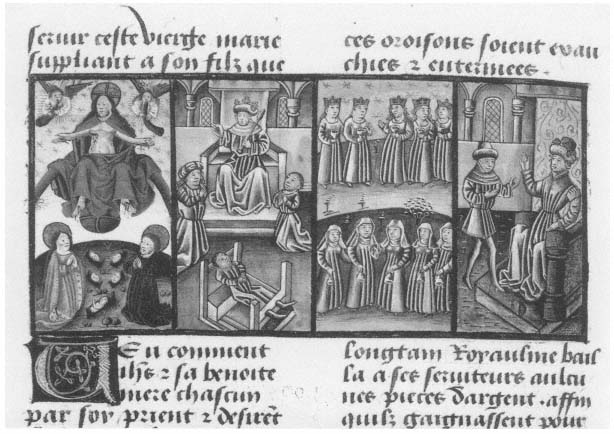

III-22.

a. The Last Judgment.

b. The Parable of the Ten Talents.

c. The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins.

d. Mene, Mene, Tekel Upharsin.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter XLII.

The Hunterian Museum Library, Glasgow, Ms. 60, fol. 57 verso.

The Newberry Library, Ms. 40

This French translation of the Speculum humanæ salvationis was written in a Bâtarde on forty-three parchment leaves, 38.2 × 28.3 cm., with text in two columns. It contains forty-two chapters and 168 miniatures. The Prologue, the Prohemium, and the last three chapters of the complete Latin manuscripts are not included.[29] It is entitled Miroir de l'humaine salvation and is not listed in Seymour de Ricci's census,[30] nor in the French translations described by Lutz and Perdrizet,[31] but it appeared in later supplements and catalogues, and its provenance is described in detail by Kessler.[32]

The text is not the translation of the Miélot minute , but it is identical in wording with the Glasgow copy, after the Prologue of the latter. The text begins on folio 1 verso "Ad ce donques que nous ne resamblons pas Lucifer" as in the Glasgow manuscript and ends on folio 43 recto "le pere et le fils et le saint esperit amen." There is no Explicit to furnish us with a date or place of its execution, but a comparison of the two texts through photographs and diapositives (fig. III-20, Plate III-9) shows them to be the same translation.

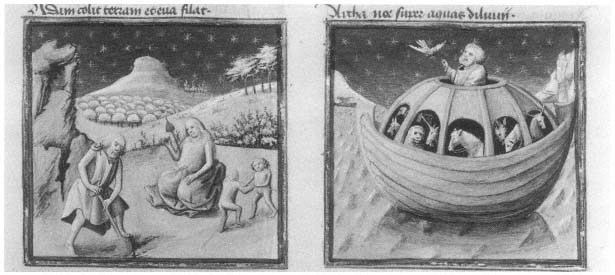

The miniatures are arranged on facing pages as in the Latin manuscripts, one at the head of each column of text, four to each chapter, and with their Latin captions or titles. The New Testament picture is in color but the three prefigurations which follow are mostly in pastel tints with grisaille figures rendered in a pale sculptural manner. The skies are a strong blue with gold stars, giving a sense of an eerie nocturnal world to the Old Testament scenes. In the Chapter I-c scene, God is admonishing a rather elderly Adam against eating the fruit of the tree, and in the background Adam is relating the message to Eve. In Chapter II-d, the Ark of Noah, with its domed super-structure, appears to be the prefiguration of a space capsule, with the animals peering out of arched windows and a circular aperture at the top for sending forth the raven and the dove (fig. III-23).

There were apparently at least three miniaturists in the Newberry manuscript.[33] According to Kessler the first 144 miniatures recall the style of a Dutch artist who contributed miniatures to the Queen Mary Hours (an English commission), to the Hours of Mary van Vronensteyn, and to the Dutch Bible of Evert van Soudenbalch. But it is now thought that all of the miniatures are by Flemish masters, not Dutch.[34]

[29] Herbert L. Kessler, "The Chantilly Miroir de l'humaine salvation and Its Models," in Studies in Honor of Millard Meiss , edited by Irving Lavin and John Plummer (New York, 1977), I, p. 276.

[30] Seymour de Ricci, Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada , 3 Vols. (1935–40; reprint New York, 1961).

[31] Lutz and Perdrizet, op. cit. , pp. 104–105.

[32] Kessler, op. cit. , pp. 276–277, fn. 14.

[33] Ibid. , p. 277.

[34] Correspondence with James Marrow, Department of Art History, University of California, Berkeley, and with Anne H. van Buren, Fine Arts Department, Tufts University, Boston, supports the assumption that no Dutch artist is involved in Newberry Ms. 40.

III-23.

c. Adam Toils and Eve Spins.

d. The Ark of Noah.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter II.

Newberry Library, Chicago, Ms. 40, fol. 3 recto.

Three French translations of the Speculum are listed in the inventory of the library of Philip the Good at the time of his death in 1467, as follows:[35]

757. Ung autre livre en papier couvert de parchemin blanc, intitulé au dehors: Le Miroir de humaine Salvacion; comançant au second feuillet Par ordonnance de Dieu , et au dernier, par tout leur desir .

759. Ung autre livre en pappier covert d'ais noirs, intitulé Le Miroir de la Salvacion humaine, comançant au second feuillet, Notre Seigneur forma Adam , et au dernier, le XLVème .

760. Ung autre livre en parchemin couvert d'ais rouges intitulé au dehors: Le Miroir de humaine Salvacion; comançant au second feuillet, Preceptum datur , et au dernier, commun regis Assueri .

Another inventory of the Burgundian ducal library was made in Ghent in 1485, some years after the death of Philip and of his son, Charles the Bold. The following French translation of the Speculum is listed:

1620. Item, ung livre en parchement de lettre bastarde couvert de cuyr rouge et de clous et de cloans de léton, intitule: Le Miroir de l'umaine salvacion, ou il y a en chacun feuillet trois hystoires de viel testament et un du novel; commenchement au second feuillet, lieu n'estoit pas garni d'un arbre ne de deux , et finissant, le Pere et le filz et le Saint-Esperit. Amen .

A third inventory was drawn up in Brussels in 1487 which included the following entry:

1760. Ung grant volume en papier couvert de cuir noir, à tout deux cloans de léton et cinq boutons sur chacun coté, historié et intitulé, Le Miroir de la salvacion humaine; en commanchant ou second feuillet, Nostre Seigneur forma Adam , et finissant au dernier, qui procède selon les chapitres du livre .

[35] Barrois, op. cit. , p. 129.

This last manuscript, on paper, is clearly the same volume as item 759 of the 1467 inventory, and it ends with the Prohemium which indicates that it contained all forty-five chapters.

The manuscript listed in 1467 as item 760 and in 1485 as item 1620 must be the one now at the Newberry Library, for, although the text quotations are the same in the Glasgow copy, the opening phrase, Preceptum datur , is the caption of the third miniature. There are no titles or captions in the Glasgow manuscript. The text beneath, in both copies, is "lieu n'estoit pas garni d'un arbre ne de deux" as in the inventory, and at the end of the forty-second chapter, each has "le Pere et le fils et le saint-esperit. Amen." The phrase in the inventory item 760 "commun regis Assueri" appears as the caption over the last miniature of the Newberry manuscript. In the Glasgow copy this phrase is lacking.

The two manuscripts were probably copied from an anterior translation, for the difference in format would preclude the assumption that either was copied from the other. Many of the volumes in the Burgundian library were acquired by purchase or gift, and the lack of a dedication to an illustrious patron, which was very much in the tradition of the Valois house and the court of Burgundy, might indicate that these manuscripts were produced by independent ateliers. In the presentation miniature of the Glasgow copy, the costume of the scribe or translator who offers the book is apparently not that of a canon or monastic. He is wearing a blue-sleeved robe lined with brown fur and a fold of red and gold thrown over his left shoulder and falling down in back.

The Newberry manuscript follows a traditional Latin one in its format and miniature captions. As indicated by the inventories it remained in the Burgundian library until after 1577, when it was still listed in the Viglius catalogue of the Royal Library.[36]

The preparation of the translation used in these two manuscripts presents some interesting questions. The Miélot minute and the de luxe copy, B.N. Ms. fr. 6275, were dated 1449, and even if the Paris manuscript was actually made later but copying the date of the minute , they must have been known to those connected with the court of Philip the Good. He had often commissioned more than one translation of the same text. Although there was already a translation into French of the Historia destructionis Troiæ of Guido delle Colonne in his library, he ordered two more versions made.

It is clear from the inventories that the Newberry translation was in the Duke's library, and it is clear from its Explicit that the Glasgow copy was made in Bruges in 1455. If we accept the inventories as evidence although they do not list the two dedicated and identified Miélot copies, it seems likely that the Glasgow copy was never part of the Burgundian library.

[36] F. Frocheur, "Inventoire de Viglius," in Catalogue des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Royale des Ducs de Bourgogne (Brussels-Leipzig, 1842), cclx.

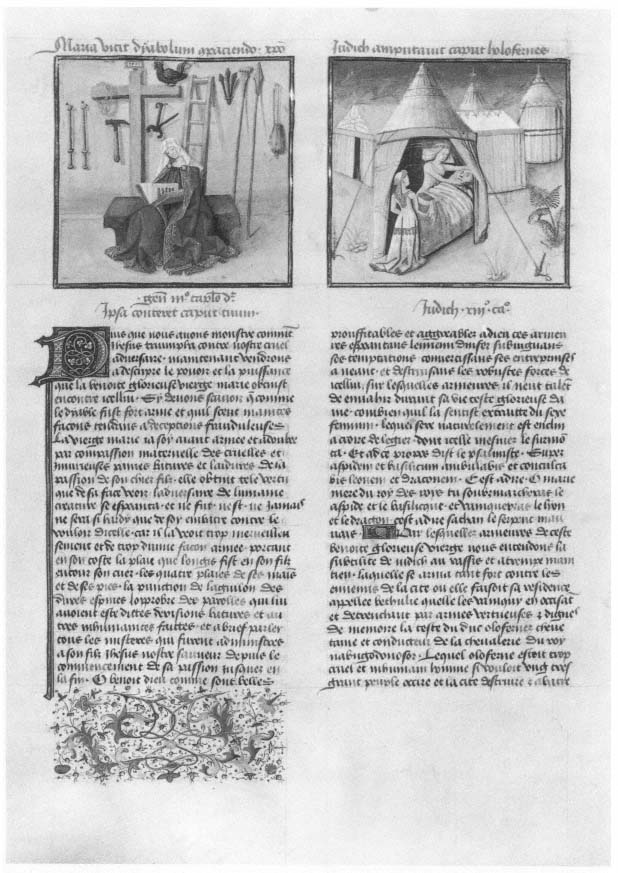

III-24.

a. Mary Conquers the Devil.

b. Judith Decapitates Holofernes.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter XXX.

Newberry Library, Chicago, Ms. 40, fol. 30 verso.

Musée Condé, Chantilly, Ms. fr. 139

This splendid manuscript, entitled Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , came to the Musée Condé through the Bruyère-Chalabre sale of 1841. It has forty-three vellum leaves, 39.5 × 30 cm., written in two columns of twenty-eight lines with 168 miniatures and initials in gold and colors. Arms are painted on two detached leaves at the beginning and end of the text. It contains forty-two chapters.[37]

The Chantilly manuscript is based partially on the one now in the Newberry Library, Ms. 40, in its text and most of its illustrations, and for others, on the blockbooks. For many years this codex was considered to be the copy in the library of Philip the Good which is described in the inventory of 1467. That description fitted the book exactly. However, the inventory made of the Ducal library in Ghent in 1485, including the Miroir , listed the exact wording of the beginning of 2 recto, "Lieu n'estoit pas garni d'un arbre ne de deux," which appears on 2 recto of the Newberry and the Glasgow manuscripts. This text appears on folio 4 of the Chantilly Miroir which, therefore, cannot be the volume described in the inventory.

Further evidence is provided by the two inserted leaves of the Chantilly manuscript which bear the coats of arms of its early owners. The first is the arms of the Flemish family Le Fèvre. The second leaf shows an angel carrying, in one hand, the Le Fèvre arms and in the other those of the Dutch family Van Heemstede. Archives show that Roelant Le Fèvre married Hadewij van Heemstede in the second half of the fifteenth century.[38] Whether Le Fèvre commissioned the Chantilly manuscript is not known.

Even more significant is the style of the Chantilly miniatures, which are characteristic of Ghent-Bruges art about the year 1500 and are much more sophisticated than those of Newberry 40, although they often follow its subjects and compositions. The miniatures of the latter were used as models for 123 of the 168 pictures by the Chantilly illuminator, who refined the figures and clothed them in the costumes of the later period. There are significant compositional modifications in more than forty of these miniatures. The artist also copied twenty-five complete compositions and incorporated details from twenty-four others from the woodcuts of the blockbook Speculum .[39]

[37] J. Merguey, Les Principaux manuscrits à peinture du Musée Condé à Chantilly (Paris, 1930), Notice 67.

[38] S. van Leeuwen, Batavia Illustrata (The Hague, 1685), I, p. 980.

[39] Kessler, op.cit. , pp. 277 ff.

III-25.

c. Lamech Harassed by His Two Wives.

d. Job Whipped by the Devil while His Wife Watches.

Le Miroir de l'humaine Salvation , Chapter XX.

Musée Condé, Chantilly, Ms. fr. 139.

III-26.

Opening page. Detail.

Le miroir de lumaine sauluation .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 188.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 188

A French translation titled Le miroir de lumaine sauluation , written sometime after 1460, was commissioned by Louis of Bruges for his fine library at Gruthuyse. It included, according to a reconstruction of the library made in the nineteenth century, fifty-three vellum leaves in-folio, written in two columns of forty lines, with a fine miniature at the head of each, 192 miniatures in all. The Prohemium and forty-five chapters were included, the last three with eight miniatures each, and finally a genealogy of the kings of France.[40] It came into the collection of Louis XI and eventually into the Royal Library in Paris, but it had already been divided about 1500, for the section on the French kings is not bound in with the Miroir .

On folio 1 recto of the Gruthuyse manuscript there is a shield composed of a blue ground with three fleurs de lis . There are no captions or titles for the miniatures but they contain lettered banderoles, the first of which states, "coment es tombe du ciel Lucifer." The initials are elaborately colored and gilded throughout.

The catalogue by Van Praet of the Gruthuyse library credits Miélot with the translation, and even cites the minute conserved in Brussels, but the wording is given for the beginnings of the Prohemium and the text, which do not correspond to the Miélot translation or to that of the Newberry-Glasgow-Chantilly manuscript. It would seem that Philip the Good and Louis of Bruges were competing for French translations of the Speculum in splendid manuscripts to grace their great libraries.

[40] J. B. B. Van Praet, "Bibliothèque de Louis de la Gruthuyse" in Recherches sur Louis de Bruges , VI (Paris, 1831), pp. 104–105. See also Claudine Lemaire, "De bibliotheek van Lodewijk van Gruuthuse," in Vlaamse Kunst op Perkament (Bruges, 1981), p. 224.

III-27a.

The Annunciation.

Le Mirouer d'humaine salvacion , Chapter VII.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 460, fol. 9.

III-27b.

The Annunciation.

Le Miroir de humaine salvation .

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Ludwig Ms. XI 9.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 460 and J. Paul Getty Museum, Ludwig Ms. XI 9

These two closely related manuscripts in French were probably copied from a single model. Each is on 95 parchment leaves, with miniatures which are about the same width but the Latin captions around the arched gold frames are missing in Ms. fr. 460. In that codex also the scribe's lines are ruled throughout but many pages lack the text. However, on the second leaf, the wording commences, "Par ordonnance de Dieu," and on the last page ends, "par tout leur desir," which corresponds to the wording of Item 757 in the 1467 inventory of the Burgundian library.[41]

The handsome Getty copy, with one miniature on each page above the two text columns, was acquired in the spring of 1983 through the purchase of the Ludwig collection of manuscripts.

[41] Paulin Paris, Les manuscrits français de la Bibliothèque Royale de Paris (Paris, 1836–1848), IV, p. 200. See also Anton von Euw, Die Handschriften der Sammlung Ludwig , Vol. III (Cologne, 1982), pp. 89–94.

III-28.

The Kingdom of Heaven.

Speculum Humanæ Salvationis , Chapter XLII.

Bibliothèque Municipale, Saint-Omer, Ms. 184, fol. 25.

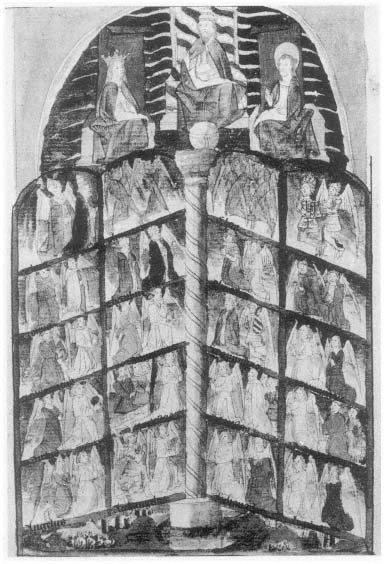

Bibliothèque Municipale, Saint-Omer, Ms. 184

Originally in the Abbey of Saint-Bertin in Saint-Omer, this manuscript, 29 × 21 cm., on paper, contains drawings and verses in French octosyllables inspired by a set of tapestries with scenes from the Speculum , which were commissioned by the Abbot sometime before 1461. The most extraordinary of the illustrations is on folio 25, a full-page drawing of The Kingdom of Heaven with archaic Parisian and later Flemish elements which place it artistically in the second half of the fifteenth century. No similar representation of Heaven exists in any other Speculum manuscript. In the same volume are found descriptions of other treasures of the Abbey.[42] There are three other Speculum manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Municipale: one which is also from Saint-Bertin, Ms. 182, is in Latin on vellum without miniatures; Ms. 183, which came from the Abbey of Clairmarais near Saint-Omer, has the best miniatures, with a Latin text and the French octosyllabic verses; and Ms. 236, copied from the Clairmarais one, which came from the Chapter library of Notre Dame at Saint-Omer and has very mediocre miniatures.

[42] Bert Cardon, "Een uitzonderlijke hemelvoorstelling in een Speculum Humanae Salvationis-handschrift uit de voormalige abdij van Saint-Bertin te Saint-Omer," in Archivum Artis Lovaniense. Bijdragen tot de Geschiedenis van de Kunst der Nederlanden opgedragen aan Prof. Dr. J. K. Steppe , edited by M. Smeyers (Louvain, 1981), pp. 53–66.

III-29.

a. The Kingdom of Heaven.

b. The Queen of Sheba and King Solomon.

Miroir du salut humain , Chapter XLII.

Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Ms. 403.

Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. 403

A unique translation of the Speculum into French verse is entitled Miroir du salut humain . It is on 54 leaves, 34.5 × 29 cm. with 192 colorful miniatures with red titles, each one at the head of a column of 26 lines which contain alternate blue and red initials. It was written on parchment in a French hand but not the Burgundian Bâtarde of Jean Miélot. Delaissé dates its execution as about 1455 and attributes it to Miélot but that clearly identified translation in the minute is in prose.[43]

The margin beside the miniature at the opening of each chapter has a leafy panel of decoration which Delaissé related to the atelier of Jean Mansel. Friedrich Winkler saw the influence of Simon Marmion in the miniatures. In German catalogue descriptions of the manuscript its date varies from 1465 to 1480.[44]

[43] L. M. J. Delaissé, La Miniature Flamande (Brussels, 1959), Item 239.

[44] Friedrich Winkler, Die Flämische Buchmalerei des XV u. XVI Jahrhunderts (Leipzig, 1925), p. 160; U. Finke, Katalog der mittelalterlichen Handschriften und Einzelblätter in der Kunstbibliothek (Berlin, 1966), p. 116; Zimelien, Abendländische Handschriften des Mittelalters aus den Sammlungen der Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz Berlin (Wiesbaden, 1975), p. 193.

III-30.

a. The Descent from the Cross.

b. Jacob Laments the Death of Joseph.

De spieghel der menscheliker behoudenisse , Chapter XXV.

British Library, Add. Ms. 11.575, lxviiii.

British Library, Add. Ms. 11.575

A translation of the Speculum into Flemish verse, De spieghel der menscheliker behoudenisse , was made in the beginning of the fourteenth century. This copy of that translation, dating from the early fifteenth century, is on parchment, 26.6 × 19.3 cm., in two columns of forty-four lines on each page, and was written in a single hand in a Littera Cursiva Formata . The manuscript contains only 97 leaves of the original 122, and 155 pen and wash drawings of which 100 are erased or badly damaged. It was in the library of G. Kloss, a Frankfurt historian and collector, until it was acquired by the British Museum in 1840.[45]

[45] L. M. Fr. Daniels, De Spieghel der menscheliker behoudenesse , Studien en tekstuitgaven van Ons Geestelijk erf, IX (1949). See also J. Deschamps, Catalogus, Middelnederlandse handschriften uit Europese en Amerikaanse bibliotheeken (Leiden, 1972), pp. 120–121.

III-31.

a. Opening page with illuminated initial.

b. Text page.

Spieghel onser behoudenisse .

Haarlem Stadsbibliotheek, Ms. II 17, fol. 1 recto.

Haarlem Stadsbibliotheek Ms. II 17

A manuscript entitled Spieghel onser behoudenisse is on deposit at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem. It is the only translation of the Speculum into Dutch prose, or the North Netherlandish language, and the text, abbreviated, is printed in the two Dutch blockbook editions. The manuscript is complete, 15.4 × 10.5 cm., on vellum in 231 leaves, forty-five chapters, in an excellent, clean condition, written as a private prayerbook without drawings or miniatures, except for a decorated initial at the beginning of the text, after the Prohemium. It shows no signs of having been used as printer's copy for the blockbooks so there was probably an antecedent manuscript, now lost, from which both were copied.

At the end there are two inscriptions as follows (in translation):

I. This book belongs to Cayman Janss van Zierichzee, living with the Carthusians outside Utrecht. The Lord be praised now and forever. Amen.

II. This book is finished anno domini 1464 on the 16 of July. An Ave Maria for the scribe.

It would appear to have been written for the important Karthuizenklooster Nieuwlicht which had a script that influenced the typefaces of the earliest Utrecht printers.[46]

[46] Supplementum Codices Manuscripti Membranei (Haarlem, 1852): see also Fr. B. Kruitwagen, O.F.M., Laat-Middeleeuwse Paleografica, Paleotypica, Liturgica, Kalendalia, Grammaticalia (The Hague, 1942).