12—

The Golden Skein:

California's Gold-Rush Transportation Network

A. C. W. Bethel

To Americans at the beginning of the Gold Rush, California seemed—and was—remote and isolated. In 1849, Rufus Porter, the editor of Scientific American , formed a joint-stock company to construct an eight-hundred-foot steam-powered dirigible intended to carry fifty to one hundred passengers "safely and pleasantly" from New York to California in three days.[1] It wouldn't have worked, but his proposal shows the spirit of the times: mid-nineteenth-century Americans were people in a hurry, and they sought to move faster using steam, iron, and electricity.[2]

But before the Gold Rush, transportation in thinly settled, cash-poor, pastoral California was limited. The roads that connected the small settlements near the coast were pack trails, improved locally for two-wheeled oxcarts. A few launches propelled by oars or sails carried passengers and freight on San Francisco Bay and the lower reaches of the Sacramento-San Joaquin river system. What manufactured goods Californians enjoyed were bartered for cattle hides and tallow from foreign-flag ships trading along the coast.[3]

Thus, adequate transport had to be improvised for an influx of gold seekers and merchants who multiplied California's population tenfold. Moreover, because most gold-rush emigrants didn't plan to stay in California, they sought only high-yield, short-term investments, and those who did plan to stay sought advantage for their own city's commerce, often at another city's loss. Fortunately the flood of new gold-rush wealth created economic incentives for fast transportation, and enterprising individuals quickly created an up-to-date transportation system, including an infrastructure of roads, wharves, bridges, ferries, express offices, shipyards, foundries and factories. Innovative shipbuilders soon devised new types of scows, schooners, and steamboats suited to California conditions.

Except for mail subsidies, development was driven by perceived demand. Large

A lithograph published in New York in 1849 by Nathaniel Currier caricatures the desperate attempts

of Americans to transport themselves as speedily as possible to the gold fields of California. The

steam-powered dirigible, upper left , was inspired by the published design of Rufus Porter, editor

of Scientific American , who early in the year offered Argonauts passage overland, at $200 each,

in his "Aerial Transport," which he anticipated placing in operation by April. California Historica

l Society .

companies, often near-monopolies, later consolidated services begun by individuals who happened to own a horse or a boat, but the efficiency gained through economies of scale rarely raised barriers to entry enough to prevent competition, and fares and freight rates declined throughout the Gold Rush.

But at the beginning of the Gold Rush, none of this was in place.

The Panama Route

The fastest way to get to California from the East was to take a steamer to Panama, cross the narrow isthmus to the Pacific, then take another steamer to San Francisco. At first the sixty-mile Panama crossing utilized large dugout canoes, called bungos, to reach the head of navigation on the Chagres River, then followed a mule trail over the divide to Panama City. Shallow-draft steamers soon replaced the bungos; the mule trail was improved; and in 1855 a railroad shortened the total transit time across the isthmus to a few hours.[4]

At Panama City, gold seekers impatiently awaited passage north; until steamer

schedules were better coordinated, they sometimes waited for months. Meanwhile they fretted in the unhealthy climate, unimpressed by their picturesque surroundings and intolerant of the local Hispanic culture.[5] The three steamships that the Pacific Mail steamship company had built to satisfy its 1847 mail contract were inadequate for the unanticipated gold-rush traffic. California , built to carry 250 passengers at most, inaugurated service by steaming into San Francisco in 1849 with 365 crowded on board. Larger and faster steamers were quickly added: Pacific Mail had fourteen ships by 1851 and twenty-three by 1869.[6]

Panama steamers were wooden-hulled side-wheelers driven by massive single-cylinder steam engines. Low boiler pressures required engines with bores and strokes measured in feet to yield a few hundred horsepower. Because these big engines turned slowly, higher speeds required paddlewheels larger in diameter, up to thirty feet or so, and the big paddlewheel boxes gave the black-hulled ships a look of massive power. All the Panama steamers had masts and occasionally supplemented steam power with sails.[7]

Pacific Mail first- and second-class passengers slept in well-ventilated, carpeted staterooms and had access to elegantly furnished public rooms; amenities sometimes included a barber shop and a bath. Steerage passengers slept on canvas bunks stretched over pole frames and stacked three high. Later, space was made for dining tables, and separate dormitories were provided for men and women. Food on the early voyages was monotonous, but Pacific Mail's management made strenuous efforts to improve it, and the line had earned a generally good reputation by 1852. By contrast, passengers traveling on rival lines protested poor food, insolent service, overcrowding, and lack of clean linens.[8]

The usual running time from Panama to San Francisco was eighteen to twenty-one days at first, later reduced to thirteen or fourteen days. Once the Pacific and Atlantic steamer schedules were coordinated, the whole trip could be made in thirty-five days; faster ships and the Panama railroad eventually shortened this to twenty-one. The frequency of sailings from San Francisco was increased from monthly to twice monthly in 1850, and to every ten days in 1860. At San Francisco the departure of a mail steamer—"steamer day"—was the frantic occasion for businessmen to settle accounts and prepare correspondence for the States.[9]

Pacific Mail's operating costs were high. The steamers' inefficient boilers consumed huge quantities of expensive, imported coal, and because there were no repair facilities on the West Coast, Pacific Mail had to build its own docks, ironworks, and machine shops at Benicia, on the Carquinez Strait. They were closed in 1861, when California's industrial base had grown enough to provide alternative repair services.[10]

Despite high expenses, Pacific Mail generally paid substantial dividends, and these profits attracted competition throughout the gold-rush period. In 1851, Cornelius Vanderbilt began developing a crossing at Nicaragua, which short-hauled

A train of the Panama Railroad pulls into the terminus of the line in December 1854. Completed

just a month later, after five years of construction, the road greatly reduced the time and cost

of crossing the isthmus. Whereas the Forty-niners paid the better part of $100 for a difficult

and dangerous five-day trip by dugout canoe and muleback, later travelers could ride coast to

coast in three or four hours for $25, enjoying splendid views of wild tropical jungles from the

relative comfort of their cars. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

Panama by four hundred miles. Reputedly a healthier place than Panama, Nicaragua offered an easier passage by small steamers up the San Juan River and across Lake Nicaragua, then by stagecoach to the Pacific. Between 1853 and 1855, the Nicaragua route drew nearly as many passengers as the Panama crossing. Completion of the Panama railroad and political instability in Nicaragua combined to make the Nicaragua route unattractive after 1856, though it was operated sporadically by Vanderbilt's successors until 1868. Pacific Mail had bought out Vanderbilt in 1859 with a substantial block of company stock that tied his fortunes to theirs.[11] Pacific Mail ships were generally well-managed and safe, despite some spectacular wrecks. Pacific Mail's rivals were less meticulous, however. Survivors ascribed the loss of the Independent Line's Union to a drunken crew; and when the Opposition Independent Line's Yankee Blade went aground, unsupervised crewmen beat and robbed passengers left on board, the captain having already put himself ashore.[12]

Between 1848 and 1869, about 600,000 passengers used the Panama route, more than 46,000 traveling in 1859, the peak year. By contrast, a total of about 156,000 went via Nicaragua. Because freight rates were high—never less than forty cents per pound—only very high priority freight went westbound via Panama: express way-bills mention clothing, liquor, medicine, books, and firearms. But more than three-quarters of a billion dollars in coined gold was transported across the isthmus eastbound, nearly $48 million in 1864, the peak year. The importance of the Panama route declined with the opening of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869; the Pacific Mail then concentrated on its transpacific steamship routes, which it operated into the 1920s.[13]

Gold-Rush Maritime Trade

Pastoral California's rudimentary economy could not begin to supply the sudden influx of gold seekers. Until the mid-1850s, even food supplies had to be imported. Provisions came from China, Australia, Chile, and the eastern United States, but they were all three to six months sailing time to California. Hawaii was only three to five weeks away, and had already developed commercial agriculture to provision whaling ships, which had concentrated in the Pacific by the 1840s. In 1850, 469 ships arrived at San Francisco from Hawaii, their trade valued at $380,000. But after 1851, Oregon supplied California's agricultural imports; Oregon was less than half the sailing time away, and its products were cheaper and better China continued to send foods preferred by Chinese emigrants, Hawaii shifted to tropical products, especially sugar, and the Pacific Northwest later became an important supplier of lumber and coal.[14]

By 1856 San Francisco had become a well-built and settled city of fireproof masonry commercial buildings, extensive piers, planked streets, and handsome residential blocks. For lack of local supply, bricks had been imported from New Zealand and Tasmania and granite from Hong Kong, and prefabricated corrugated iron buildings had come from Britain, Asia, and Australia. The demand for lumber quickly outran the capacity of existing California sawmills, and lumber was imported from the East Coast until 1855—eighty million board feet in 1852.[15]

San Francisco builders valued coastal redwood for its long, straight grain and resistance to fire. Stands of redwood in the Oakland hills and in the Santa Cruz Mountains had been exploited since Hispanic times, but the largest stands of redwoods occupied a four-hundred-mile coastal belt about thirty miles deep stretching from the north shore of San Francisco Bay to the Oregon border By 1852, sawmills were turning out lumber at Humboldt Bay and along the Mendocino coast. Much of this cut went to San Francisco, but there were foreign exports as well: by 1854, Humboldt Bay was shipping lumber to Australia, and later to China, Hawaii, Chile, and Tahiti.[16]

Navigation along the redwood coast was hazardous. Humboldt Bay offered a protected anchorage, but heavy seas broke over a shallow sandbar at the entrance. Along the eighty-five-mile Mendocino coast, lumber mills were sited on steep bluffs above narrow estuaries, where often the only practical way to deliver lumber to a moored ship was by skidding it down a wooden chute slung from cables. Surging tides, fogs, and submerged rocks made navigation into these "dog-hole" ports dangerous. Steam power, which gave captains better control, would not be fitted to coastal lumber schooners until the 1880s.[17]

To meet the special demands of the traffic, shipyards along the West Coast began delivering handy, flat-bottomed, broad-beamed, single-decked sailing schooners of one hundred tons or so beginning in the 1850s. These craft had oversize hatches for quick loading, and could carry as much lumber above deck as below. Deck loads were chained down to prevent dangerous shifting during the voyage. Broad-beamed hulls made the schooners stable even when empty so that they could return northward safely without cargoes.[18]

Forty-niners emigrating by way of Cape Horn cleared eastern ports of old ships, and the fast clipper designs that had evolved by the early 1840s now dominated a burst of new construction that briefly eclipsed steam and made America's merchant marine a rival to that of Great Britain. The new clippers had narrow hulls and long, concave bows that cut easily through the sea. Above water, their long, black, flush-decked hulls, often accented by a narrow stripe of white or color, had a sleek, racy look. Clippers spread very large sail areas, and their captains were willing to risk sprung masts and snapped yards in gale-force winds in order to gain a fast passage. The clippers' sailing rigs required large crews; poorly paid, the men were hard to manage, and their officers frequently enforced orders physically. Until well into 1851 it was hard to keep a crew from deserting to the mines at San Francisco, and shipping agents recruited men by offering high wages, or by shanghaiing them.[19]

The clippers' impressive performances were aided by the publication of Matthew Maury's charts of ocean winds and currents, which showed that the fastest course under sail was not always the shortest in miles. By following Maury's directions, captains reduced their sailing times to California by forty days or so, whether their ships were clippers or not.[20]

The clippers' hollow lines and vee-shaped bottoms limited their cargo capacity to perhaps half that of a fuller-bodied ship, and their operating expenses were high. In 1850—51, when high-priority freight rates to California were as much as sixty dollars a ton, or one dollar per cubic foot, a single voyage could repay more than the clipper had cost; but freight rates slipped to thirty dollars a ton by 1853, and to $7.50 a ton by 1858, half of the rate that clippers needed to break even. After the Civil War, America's wooden-hulled merchant marine entered a long decline, and British iron-hulled sailing ships dominated California's growing wheat trade with Liverpool.[21]

The Flying Cloud , probably the most famous of all clipper ships, prepares for her maiden

voyage, from East Boston to San Francisco, in a wood engraving that appeared in Gleason's

Pictorial Drawing Room Companion in May 1851. Built for speed, clippers carried less

freight and fewer passengers than slower vessels, but Forty-niners willingly paid premium

prices—as much as $1,000—for passage on one of these glorious vessels. Young Josiah

Creesy, who first captained the Flying Cloud , drove her around Cape Horn in midwinter and

passed through the Golden Gate in a record eighty-nine days, some two or three months faster

than broader-beamed ships. California Historical Society, FN-30960 .

Bay and River Traffic

San Francisco became gold-rush California's entrepôt because its location just inside the Golden Gate was convenient for arriving ships, and it gave easy access to the Sacramento-San Joaquin river system, which became a supply highway to the mines. River towns—Stockton, Sacramento, Marysville, Colusa, and Red Bluff—grew as centers where goods brought from San Francisco by riverboat could be forwarded by pack train or wagon to the mining towns. Sacramento, the busiest of the river ports, received at least 165,000 tons of freight in 1852, of which perhaps 10 percent was used locally and 15 percent was forwarded upriver, and the rest sent on to the mines,

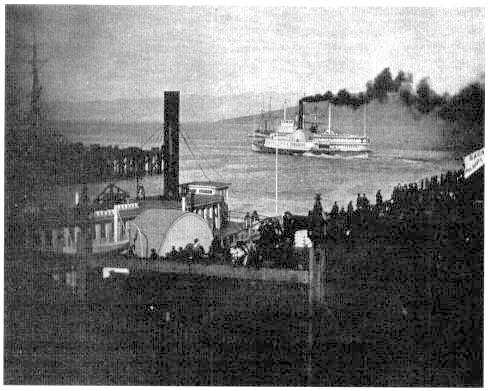

The side-wheeler Yosemite departs for Sacramento from the Broadway wharf of the California

Steam Navigation Company, about 1865. Steamboats not only provided a swift and reliable

mode of transportation for passengers and freight, but also offered an agreeable way of seeing

the California countryside. After an excursion from San Francisco to the state capital in the

spring of 1859, the publisher of Hutchings' California Magazine declared he "could not

recommend a tour which can be made with so much ease, and is so generally calculated to

please every variety of tastes, as a trip on the bay and river." Courtesy Society of California

Pioneers .

three hundred to four hundred tons a day at the height of the season.[22] At first the trip upriver from San Francisco to Sacramento or Stockton usually took about a week. Labyrinthine sloughs could easily disorient navigation, and riverbank foliage sometimes screened off the wind so that the boats had to be rowed or hauled from shore. Clouds of voracious mosquitoes added to the passengers' discomforts.[23]

To expedite bay and river freight, local boatyards developed a distinctive, blunt-ended, flat-bottomed scow schooner in the early 1850s. These surprisingly fast and handy boats carried bulk cargoes, such as hay and potatoes, stacked so high on their decks that the helmsman steered from a raised "pulpit" in order to see ahead.[24] The first steamboats were serving bay and river ports by late 1849; there were about fifty

in service a year later. Competition for fast passages soon led to spirited racing, in which steamboat pilots tried to push rival boats ashore or zigzagged to keep them from passing. Passengers wagered on the outcome and sometimes fired pistols at the competition's boat. Deadly boiler explosions resulted from excess steam and deferred maintenance, snags and collisions sank boats, and shifting sandbars in poorly charted rivers stranded them.[25] Racing was ended and tariffs were stabilized by the 1854 merger of several competing steamer lines into the California Steam Navigation Company. Because it was fairly easy to finance a steamboat, the merger never achieved a total monopoly, and there were still occasional rate wars, but increased demand generated enough business for these additional boats, which were often eventually absorbed into the merger.[26]

Fast, elegantly furnished side-wheel steamers provided daily service connecting San Francisco with Sacramento and Stockton in nine or ten hours, though the Sacramento trip was once made in less than six. Smaller stern-wheel steamboats that drew as little as two feet of water served points on the shallow, tortuous stretches of the upper rivers. Because shallow hulls lacked internal stiffness, the smaller, upriver steamers had to be strengthened externally with a cat's cradle of cables attached to a vertical post, called a "hog post," that extended above the superstructure. The little steamers could tow barges by means of a cable attached to a swivel mounted on the hog post, an arrangement that kept the towing cable clear of the stern-wheel and gave the boat's rudders good leverage against the resistance of the barge.[27]

Initially there was only a little downriver freight, mostly in hay and cordwood, but tonnages grew with the development of California's bonanza grain-based agriculture, and downriver freight equaled upriver freight by 1861. Throughout the river system, hundreds of landings, some improvised from brush and planks, became shipping points for otherwise isolated farms, where steamboats would stop for a flag or a lantern signal. Red Bluff was the head of navigation on the Sacramento after snags were cleared above Colusa in 1852. At first, upriver boats regularly reached Marysville on the Feather River, but water diversion and silting impeded navigation after 1855. During the high-water season, from January until July, small, shallow-draft boats steamed south almost to Fresno on the San Joaquin.[28]

Packing to the Mines

In the absence of roads, supplies at first reached the mining camps by pack mules. The mules were managed by experienced Mexican muleteers, or arrieros . Their Mexican pack saddles rested the load on a straw-stuffed leather bag, called an aparejo , instead of on wooden crossbucks. The aparejo was heavier, but it was easier on the animals' backs, and the Army later also adopted it. A mule could pack from 200 to 350 pounds of freight twenty-five to thirty-five miles a day, depending on ter-

rain. Mule loads included flour, beans, whiskey, chairs, tables, plows, pianos, and iron safes.[29]

Because each miner consumed at least a pound of supplies daily, packing to the mines required large numbers of mules: 2,500 mules carried freight from Marysville to Downieville, for example, providing employment for perhaps four hundred men. One thousand pack mules left Marysville in one day, carrying one hundred tons of freight, the equivalent of two steamboat loads. Packing was a seasonal business, but sometimes pack trains operated in the Sierra winter, carrying barley along with the freight because there was no forage for the animals. Sometimes animals and muleteers froze to death. Other mules perished in falls caused by shifting packs or unstable ground, and robbers and hostile Indians sometimes attacked the trains.[30]

Wagon Roads, Bridges, and Ferries

Wagon freighting had natural advantages over packing: a mule could draw about two thousand pounds, many times the load that it could pack, and wagons did not have to be unloaded every night. But because wagons could not follow a contour line, wagon roads first had to be graded into the Sierra foothills from the river ports. Some roads were built and maintained by joint-stock toll road companies—there were sixty-four of them in California by 1858—but merchants and civic boosters often subscribed for road improvements without charging tolls, and counties built some roads with public funds. Many gold-rush road improvements were just enough to get the wagons through, with hairpin turns and grades as steep as fourteen degrees, but other construction was substantial. Cuts were blasted with black powder and then cleared with picks and shovels.

Bridges—117 by 1856—crossed ravines, and rock cribbing supported fills. Culverts and diversion ditches sometimes drained roadbeds, though heavy rains still left them so muddy that wagons mired to the hubs. In the winter, scrapers and the tramping of animal hooves cleared some snow, though many mountain roads could be operated only during warmer and drier seasons. These roads were often only a foot or so wider than the wagons that used them. Frequent turnouts allowed wagons to pass, and loaded wagons going uphill had the right of way. Iron tires crashing over uneven, rocky ground announced their coming, as did jangling brass bells, tuned to a chord—usually C, E, G, C—and fastened to flattened hoops above the collars of the lead span.[31]

Swift-flowing rivers dissect the Sierra foothills, so ferries and bridges became nodal points in the road system. The first ferries were skiffs—wagon boxes were floated across—but skiffs were soon replaced by flat-bottomed barges large enough to carry a wagon and team. Some early bridges that replaced ferries were plank roadways floated on pontoons, but wooden truss bridges were introduced in 1850. The trusses were often housed over to protect their structural members from the el-

A pack train makes its way through a snow storm in a wood engraving after a design by

Charles Nahl, 1856. Packers and their mules encountered a variety of dangers in carrying

supplies to mining camps, but winter trips were especially hazardous. When a tremendous

storm caught one train between Grass Valley and Onion Valley, all but three of forty-five

mules perished before the snows lifted. California Historical Society, FN-30968 .

ements, though floods swept away ferries and bridges alike. Wire rope, widely used in mining, was adopted for suspension bridge construction by 1854.[32]

Freight Wagon Technology

California freight wagon boxes were flat-floored and long—sixteen to twenty feet—but only three or four feet wide. Their sides were often overtopped by bulky loads stacked as high as fifteen feet. For oversized loads, such as boilers, the box was removed and the load was secured directly to the running gear. Six-foot-high rear wheels and iron fires up to four inches wide reduced the pulling effort required of the

animals. Wagon builders selected different hardwoods for different structural functions, then seasoned the wood for three to five years to prevent shrinkage. Rugged freight wagons could weigh nearly two tons empty, and loads of six to eight tons were common. With a trailer, or "back-action," the load could be roughly equal to one of today's long-haul trucks.

The number of mules used depended on the load and the terrain; sometimes there were twelve to twenty or more mules, all controlled by a single rein, called a jerk line, that ran forward to the bit of the left leader. The mules were trained to act as a coordinated team, and when the wagon rounded a turn, some of the mules would jump over the chain that harnessed them to the wagon tongue and pull tangent to the curve, because a force at an angle to the wagon tongue would only tend to pull the wagon off the road. Teamsters were famous for their foul vocabulary, and they encouraged their teams with whip-crackings and tossed pebbles, but most of them treated their animals humanely for reasons of both prudence and affection. Still, the work was hard, and on steep grades the animals could sometimes pull only forty or fifty feet before needing a rest.[33]

The Trans-Sierra Roads

Covered-wagon emigrants opened the first roads across the Sierra. At first some of these roads were so steep and rugged that wagons had to be disassembled and packed piecemeal over the rougher stretches. California communities that hoped to gain the emigrants' commerce improved these roads with some bridging and grading. By 1852, half a dozen of them were in passable condition, and the emigrant's choice of route depended on his or her destination. The Carson route, which went from Nevada south of Lake Tahoe to Placerville, attracted the most traffic in spite of its double summit; the Donner Pass route had only a single summit, but it fell out of favor because of repeated, difficult fords in the Truckee River canyon.[34]

California's isolation furnished another motive for trans-Sierra roadbuilding. Popular enthusiasm expressed in organized meetings and petitions resulted in state legislation in 1854 to build a trans-Sierra highway, despite steamship company opposition. Although state courts invalidated this legislation on constitutional grounds—Article VIII required that large expenditures be submitted directly to the voters—Sacramento, Placer, and Yolo counties subscribed $50,000 for an improved Placerville-Lake Tahoe road, to be graded twelve feet wide and cleared of all brush and rocks. It opened in 1858. The discovery of the Comstock silver lode in 1859 made the Placerville road a major freight and stagecoaching highway, supplying a Nevada population of up to 40,000 people. In 1863, 30,000 tons of freight and 56,500 people passed over the road. Traffic was so dense that it was difficult for a wagon to re-enter the traffic stream from a turnout, and delays limited a day's

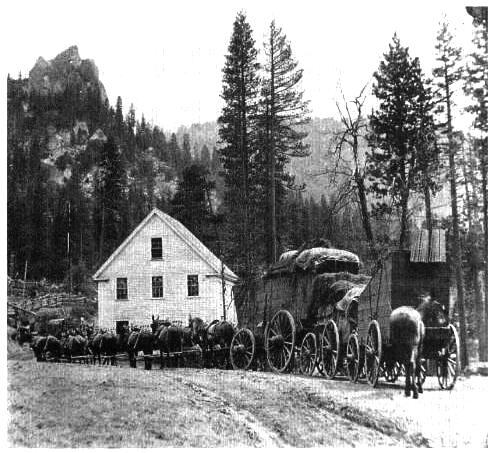

A huge freight schooner pulled by a six-span team of mules pauses at Webster's Station, in

the shadow of Sugar Loaf Mountain on the Placerville Road, about 1865. Built along stretches

of the old Johnson's Cutoff, an alternative to the Carson Emigrant Trail, the road opened in

1858, and until the decline of the Comstock Lode in the mid-1860s, it was the great artery of

travel over the Sierra Nevada. In addition to the tons of freight that rumbled over the road,

thousands of overland travelers passed this way, including Horace Greeley and Mark Twain.

Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

progress to eight miles or so. Toll toad companies financed extensive improvements that cost up to $5,000 per mile, and maintenance costs were $2,000 to $3,000 per mile yearly, but freight alone brought in at least $3 million in tolls in 1862.[35]

Then in 1862, the Central Pacific Railroad began construction east from Sacramento, with the goal of laying track along a continuous ridge rising from Auburn to Donner Pass, down the Truckee River canyon, and from there east across Nevada. The Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862 and 1864 authorized loans of federal government bonds to subsidize this construction, but the bonds were slow to arrive and did not

remotely cover construction costs. To generate badly needed revenue, the railroad graded the Dutch Flat toll road parallel to the planned rail line, in order to provide a connection to the Comstock from the end of the advancing track. Completed in 1864, it cost the chronically cash-poor railroad $350,000, but teamsters soon preferred it to the Placerville road, and it yielded a million dollars in revenue yearly. The road proved to be the most important trans-Sierra highway until the railroad was completed to Nevada in 1868.[36]

The Expresses

For lack of resources, there was no government mail service to California's mining camps at first, and the wait at the San Francisco post office could be hours long. By late 1849, enterprising private-sector expressmen filled the gap, charging miners in the mountains a dollar for asking after their mail, and an ounce of gold for each letter that they brought back from San Francisco. Expressmen soon added other services, such as carrying gold dust to San Francisco and bringing back newspapers. Express was packed on mules or, in winter, by the expressmen themselves, using snowshoes or skis; the latter were introduced into California by Norwegian-born ex-pressman John Thompson.[37]

By the 1850s, over sixty express companies served the mining camps. Most of these companies were one-man operations, with a service area defined by steep ravines and ridges. Consolidation began in 1849, when Adams & Company, which had been in the express business in the east since 184o, opened a California branch and contracted with small California express companies to carry parcels east by ship. By 1853, Adams was an important California business house, though one with a reputation for sharp and shady dealing.

Wells Fargo, organized in 1851 by some of the founders of American Express to do business in California, purchased smaller expresses and quickly developed a statewide network of branch offices, operating 56 of them by October 1856, and 147 by 1860. These branch offices accepted banking deposits, bought gold dust, provided secure, fireproof storage, and accepted and distributed express. Wells Fargo carried first-class mail until 1895 federal legislation prohibited it; patrons willingly paid express charges on top of U.S. postage. The business panic of 1855, which ruined Adams & Company in California, distracted Wells Fargo only briefly, a reflection of the firm's sound management and reputation for business integrity.[38]

Stagecoaching

Stagecoach routes soon radiated from the river ports to the foothill mining towns. Other routes crossed the valley floor to link Stockton, Sacramento, and Marysville,

Marysville with Colusa, and Stockton with Oakland via Livermore Pass. Stages covered the 188-mile route from Sacramento to Shasta in about thirty hours, and competed successfully with upriver steamboats. Visalia, about 15o miles south of Mariposa, became a staging center for the Kern River mines in 1862; these mines could also be reached by stage from Los Angeles over Tejon Pass by 1865. By 1853 a dozen different stagecoaching companies operated from Sacramento—the busiest staging center—employing three to twelve coaches and from 35 to 150 horses. Large-scale operation offered the advantages of lower costs, convenient connections for longer journeys, and better equipment. In 1854, as happened with river steamers, about five-sixths of California staging was consolidated into the California Stage Company, capitalized at a million dollars. Despite consolidation, competition remained vigorous. Some Stockton lines and all the southern California lines remained independent, some lines were later returned to their original owners, and independent operators continually added new routes.[39]

Stagecoaching across the Sierra over the Placerville-Lake Tahoe road began in 1857, and by 1864 Louis McLane's Pioneer Line was running four coaches each way daily. After the completion of the Sacramento Valley Railroad from Sacramento to Folsom in 1856, coordinated steamboat, rail, and stage schedules reduced the San Francisco-Virginia City trip to twenty-four hours. Wells Fargo acquired the Pioneer Line in 1864 and the California Stage Company's Dutch Flat route the next year, though this was not generally known until their grand consolidation of most staging operations west of the Missouri River in 1866.[40]

Continuing complaints of dilatory steamship mail service led Californians to agitate for overland mail delivery. The first such service was the heavily subsidized but underutilized San Diego-San Antonio mail of 1857; the next year, John Butterfield's Overland Mail began running on a twice-weekly, twenty-five-day schedule between San Francisco and the railheads for Memphis and St. Louis. The roundabout route by way of Yuma allowed year-round operation but probably also reflected the post-master-general's southern sectional orientation. The well-managed line operated regularly, often ahead of schedule, and by 1860 the stages were carrying more mail than the steamers did. Stages ran day and night, and passengers slept on board despite the rough ride. The coaches required eighty hours to cover the route between San Francisco and Los Angeles, via Pacheco Pass, Visalia, and San Fernando Pass, so the average speed was only about five miles an hour.[41]

In 1861 the Overland Mail was briefly rerouted along the coast via Santa Susana Pass, Santa Barbara, Gaviota Pass, and San Luis Obispo. This route later passed through a series of owners who offered indifferent service until a competent superintendent took charge in 1868, a year in which the coast line began providing daily departures using 272 horses and 23 stages. San Diego stagecoaches made connections

with the overland and coast lines at Los Angeles, and also offered direct service to San Bernardino via Temecula and, in 1868, to Yuma.[42]

A federally subsidized monthly mail had used the Placerville-Salt Lake route since 1851; in 1861, the Overland Mail was shifted to this route, receiving a million-dollar subsidy to operate a daily mail and a semi-weekly pony express that moved the mail faster, but for very high charges. The Pony Express, begun by the Central Overland and California Pike's Peak Express the previous year without a subsidy, ran only until the completion of the overland telegraph in October 1861, unable, as they then said, to compete with lightning.[43]

Stagecoach Travel and Technology

At first, staging was by spring wagons drawn by mustangs or mules, but soon experienced stage operators imported better livestock and Concord coaches. The Concord's curved ash body rested on long leather thoroughbraces that divided the 2,500-pound weight of the coach into two parts, reducing the shock of a rough road and making it easier for the team to start the coach. Nine to twelve passengers rode inside, and up to a dozen more on the flat roof. On difficult roads, stage operators substituted thoroughbraced "mud wagons" that were canvas-roofed, lighter, and lower-slung than the Concords.[44]

Because they served passengers, stagecoach drivers (or reinsmen) generally had more social graces than wagon freighters, had much higher social status, and were usually better educated. Reinsmen were popularly called "jehus," after the furious charioteer of 2 Kings 9: 20. The subtle hand movements by which they tightened or slipped the reins to control each pair of animals separately were scarcely noticeable even to passengers sitting beside them, who sometimes mistakenly attributed the driver's skill to the native intelligence of the team. The horses were hitched loosely, so that jolts to the wheels that jerked the wagon tongue were not transmitted to the animals. Drivers usually made no effort to avoid potholes or rocks, allowing the horses to find their own way so that they would be reliable in darkness or bad weather. Although there was some racing between rival stage lines, the horses were usually driven only at the walk or trot.[45]

Passengers had mixed opinions about stage travel. Journalists sometimes wrote derisive verse about their discomforts and inconveniences, but passengers who found the jarring, shaking ride excruciating nevertheless enjoyed the scenery, found the rapid pace exhilarating, and admired the drivers' skill. Some passengers objected to their fellow passengers' constant spitting and foul language, and complained of clouds of choking dust. To make uphill grades easier on the animals, passengers were expected to get out and walk, and the men were expected to push. Accidents

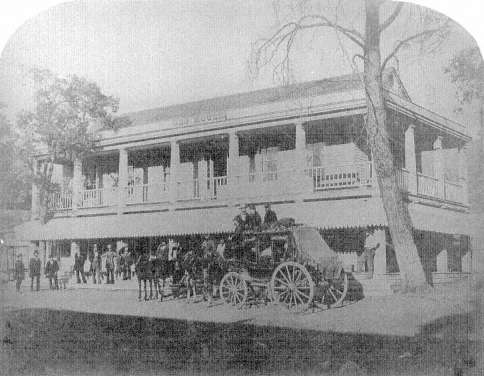

A Concord coach prepares to get under way from a stop at the Oso House in a photograph

taken in 1859 by Carleton Watkins. Despite the graceful lines of the celebrated coach,

staging was invariably an ordeal of rough roads, bad company, long days, and clouds

of dust. California Historical Society, FN-24569 .

were accepted as unavoidable hazards of travel. Top-heavy coaches overturned and tumbled down ravines, and rough roads sometimes threw drivers from their boxes, but despite broken bones, they were often able to regain control of their teams. Passengers were advised to stay aboard a runaway coach; when coaches overturned, injuries were often limited to bruises and scratches. In wet weather, deeply rutted, muddy roads, washouts, and rain-swollen fords slowed travel or stopped it altogether. When high water swept coaches downstream, passengers had to swim or drown.[46]

Southern California Gold-Rush Transportation

Isolated from the mining regions by the steep and rugged Transverse Ranges, southern California developed as a freighting and stagecoaching center for Arizona and Utah.[47] Commercial freighting between Los Angeles and the rude harbor at San Pe-

dro began before the Gold Rush, and by 1853 rival stagecoach operators were racing each other over the rough twenty-mile road. A year later, the transportation partnership of Phineas Banning, an energetic freighter and stage driver, and David Alexander used five hundred mules, thirty or forty horses, forty wagons, and fifteen stages.

In 1857, Banning began dredging the marshy back bay behind Rattlesnake (now Terminal) Island to create a channel six to ten feet deep leading to a protected wharf for shallow-draft coastal vessels and for lighters—barges that Banning used to unload cargo from larger ships that had to anchor in deeper water. In 1858 and 1859, Banning's wharf—he named the place Wilmington, after his Delaware hometown—imported 7,000 tons of merchandise and more than 1.5 million board feet of lumber. Exports were agricultural products, especially grapes and, after the Owens Valley mines began production, silver bullion. In 1869, southern California's first railroad connected Los Angeles with Wilmington.[48]

Beginning in 1847, Mormons had pioneered a freighting corridor from Salt Lake City south and west through Provo, Cedar City, Las Vegas, and Cajon Pass to their satellite settlement at San Bernardino. In 1855, Banning and Alexander and others began hauling freight to Salt Lake City over the all-year road. When winter closed the Sierra passes, freight from northern California was shipped to Los Angeles to be forwarded over the corridor to Utah; some freight was shipped as far as Idaho and Montana. Sometimes a hundred tons of freight were warehoused in Los Angeles awaiting shipment. The road was challenging: Cajon Pass had grades as steep as 30 percent until 1861, and one stretch of fifty-five miles had no source of water; the federal government allocated an inadequate $25,000 for improvements in 1854.[49]

Although the Mormon colony left in 1858, San Bernardino developed as a lumbering and agricultural center and generated freight in its own right. During the Civil War, Los Angeles-based freighters supplied military posts at Yuma and Tucson in Arizona from the quartermaster depot at Wilmington. Gold discoveries on the Arizona bank of the Colorado River in 1862 generated traffic over the Bradshaw road east from San Gorgonio Pass to Ehrenberg and La Paz. Finally, freight traffic to and from the Owens Valley mines grew from the mid-1860s.[50]

From 1857 to 1861, twenty-eight of the Army's camels were based at Fort Tejon, in the Transverse Ranges north of Los Angeles. The camels had been imported in response to dramatic increases in military transportation costs after victory in the Mexican-American War led the United States to annex large tracts of desert. Camels could pack seven hundred pounds easily, though their swaying gait required special packing techniques. The Civil War ended the experiment, however, and the unloved animals were sold. Civilian freighters used camels across the Sierra and in Nevada, but the beasts so frightened horses that public opinion restricted their use. Most were eventually turned loose to fend for themselves.[51]

The Beginnings of East Bay Commuting

Since 1851, a ferry had run from San Francisco across the bay to the foot of Broadway, on the estuary separating Oakland from Alameda, but the shallow sand bar at the estuary mouth limited the size of the boats and made navigation slow and tricky. A shorter, more direct route from San Francisco to Oakland Point opened in 1862, connecting with a commuter train that steamed along Seventh Street to downtown Oakland. Demand soon justified six round trips daily. A similar rail and ferry system was introduced across the estuary at Alameda, and in 1866 this line introduced the double-ended, beam-engined, side-wheel ferryboat that soon came to typify San Francisco commuting. This technology functioned alongside much newer types of propulsion until well into the twentieth century, when automobiles and bridges made the ferry system redundant.[52]

At the beginning of the Gold Rush, the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay had been important only as a route to the mines, but by the early 1860s, helped by a sunnier climate than San Francisco's, Oakland and Alameda were growing as commuter suburbs. These communities attracted people who wanted churches, schools, and shaded, spacious neighborhoods, and who thought that San Francisco catered to vice and corruption. By the end of the decade, a settled metropolitan area was emerging around San Francisco Bay from the confusion of the Gold Rush.

Conclusion

During the Gold Rush, Californians extemporized a modern, statewide transportation network of ocean and river navigation, wagon roads, telegraph lines, and the beginnings of a railroad network. The railroads would soon transform California yet again, making shipping and traveling faster, cheaper, and easier, making the trans-Sierra roads irrelevant, and with the development of agriculture and the decline of mining, reorienting the axis of travel away from the foothills to the length of the Central Valley. Some stagecoaching and wagon freighting would continue into the early twentieth century, but only as feeders to the railroads. Then motor vehicles running on a new system of hard-surfaced roads would make them redundant, along with much of the state's railroad mileage. River traffic would continue well into the first half of the twentieth century, sometimes prospering. So would coastal steamers, though the convex contour of California's coastline lengthened their routes compared to the more direct rail lines. The Panama route would not be important again until the opening of the canal in 1914. Thus it is tempting to look at gold-rush transportation as a twenty-year preliminary to the very different transportation pattern that evolved later. In any case, it was a marvel of improvisation and ingenuity.