Community Landscapes

In 1946–47 Ain and Eckbo also designed Park Planned Homes, only a part of which was realized [figure 121]. The subdivision was originally planned to span four square blocks of Altadena, but of its projected sixty units only twenty-eight were ever built—along a single street. To increase economy, Ain resorted to semi-prefabrication. Savings were ultimately minimal, however, with building crews demanding higher wages for less labor. These practices confirmed Ain's prejudice

121

Park Planned Homes. Site plan. Altadena, 1946–47.

Gregory Ain, architect.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

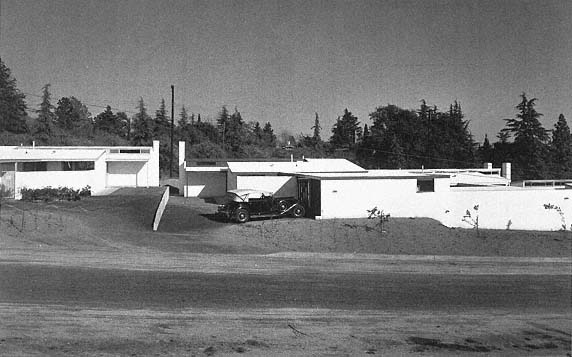

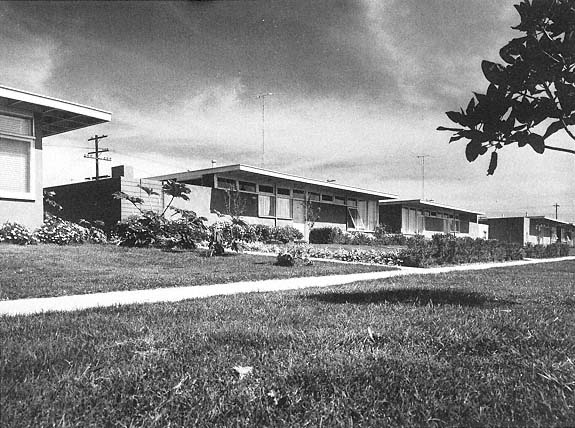

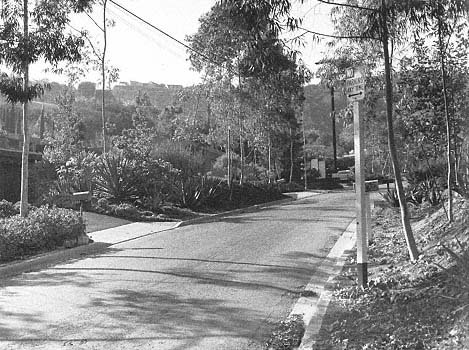

122

Park Planned Homes. Altadena, 1947.

Gregory Ain, architect.

[Julius Shulman ]

against standardization, which most contemporary architects seemed to consider an aim in itself, and an "incidental means to mass production of good dwellings."[77]

The 1,600 square-foot houses, oriented east-west, were placed on quarter-acre lots stepping down the incline of Highview Avenue [figure 122]. Of reasonable size, with three bedrooms and two baths, a patio-garden in the back and a play area/service yard in the front, large expanses of glazing and a clerestory for light and ventilation, the buildings offered openness and transparency without undermining privacy. The garages—paired and sharing a driveway—sheltered the service yard and children's play area from the street. Although both the site and floor plans show Eckbo's varied designs for individual gardens, the streetscape received his closest attention.

With the houses and garages set back from traffic, ninety-six-foot long planting strips provided a green transition between street and house. These islands of brilliantly colored flower beds were intended to combine with the varyingly painted street facades to relieve monotony. The planting schemes for Community Homes used trees to form linear spines or allées through the residential neighborhood and even to subvert its order. For a distinct identity, Eckbo usually keyed species to a block, a street, or at least a cluster of houses. The vegetation of Park Planned Homes was far more variegated within a smaller range [figure 123]. Here, he alternated heights and textures with each pair of garages and, coupled with the staggered driveways across the street, achieved a shifted allée of fragments. From the quincunxed planting strips sprang Lombardy poplar, olive, dwarf eucalyptus, and Mexican palm, to name only a few elements of the complex vegetal palette. Nearer the front door, the plantings became more regular—with Chinese pistachio marking the entrance to houses—culminating in the green frame of the hedges that outlined the rear gardens. With this variety of street trees, Eckbo established a play between street landscape and service yard, as private canopies emerged from behind enclosures and merged with the public landscape, making the latter part of the private realm while magnifying the streetscape of Highview Avenue.

Today, the image of Park Planned Homes is hardly that of an idyllic community, with collections of cars in various states of disrepair clut-

123

Park Planned Homes. Planting plan (27 February 1947). Altadena.

Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

tering some driveways. The elegant balance of solid and voids has been distorted over the years, as additions were built and courtyards filled. A glance at the model of the original scheme affirms the idiosyncratic entente between Ain and Eckbo, whose interest in the social planning of housing communities outweighed that of designing luxurious individual houses and their gardens.

The two designers would renew their collaboration in Mar Vista, a planned development east of Venice [figure 124]. Completed in 1948—if only partially, with only 52 of the intended 100 houses constructed—Mar Vista probably remains the most compelling evidence of a model joint venture among architect, landscape architect, and developer that would provide an alternative to the sterile productions of the "banker-builder-realtor trinity."[78]Arts and Architecture reported that to the Advanced Development Company, the project's developer, a house was not a mere commodity as it is for the typical builder—that is, an object to be bought and sold. Instead, it exemplified the "broader and more human definition of the word commodity ," that is to be convenient and provide amenity and accommodation.[79]

Modernique Homes (as the project was advertised)—of roughly 1,050 square feet on 75 x 104-foot lots—featured a basic unit type, with eight possible relations of house to garage and house to street [figure 125].[80] Intended to appeal to the average veteran, the house was situated on an average lot and intended to answer average needs. Modern planning fostered "full use of necessarily limited area; removal of living room from the main line of traffic through the house; direct connection of the living room with garden area away form the street; ease of maintenance, etc."[81] Sliding partitions provided flexibility within and increased a sense of openness and functionality. This description—equally applicable to the houses of Park Planned Homes and even Ladera—fit Ain's overall approach to low-cost housing, which he had already announced while judging the 1943 design competition for postwar living:

A few plans, compact and well-studied, were eliminated early . . . as architectural clichés. They were well organized, had good interrelation of rooms and gardens, and adaptability to restricted sites, and especially showed intelligent regard for the "Amenities of Living" (a cliché incidentally). They were reminiscent of some -

124

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Aerial perspective. Los Angeles, 1948. Gregory Ain, architect.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

125

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, circa 1949. Gregory Ain, architect.

Meier Street around time of completion.

[Julius Shulman ]

thing that had already been done, but something that could well become a respected tradition. But it must not be forgotten that some clichés are so apt and forceful that they eventually became valuable additions to a vocabulary .[82]

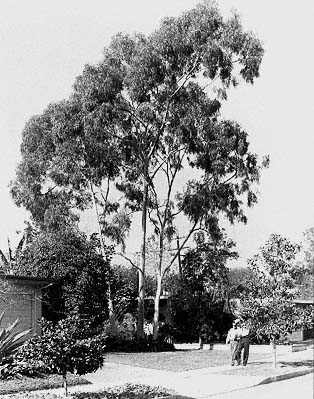

Similarly, Eckbo would refine his own clichés, or "valuable additions to a vocabulary" of landscape design and planning: neighborhood identity, relation of the individual to the group, manipulation of ground plane, spatial definition of overhead, and enclosure. He fully understood Ain's modest yet persevering attitude, later writing: "In all . . . Ain projects, the houses had a repetitive clarity with subtle variations. They challenged me to exploit variations in garden design for smaller spaces, and variations in street front treatment within overall unity" [figure 126].[83] Mar Vista was no exception, as Eckbo blurred once again the division between public and private domains, treating the buffer gardens as an expansion of the common green, and pulling the sidewalk away from traffic. He lined the streets with wide lawn strips and allées of magnolia on Meier, melaleuca on Moore, and ficus along one side of Beethoven. The character of each of these blocks varied greatly [figure 127]. With the allée of magnolia—a slow-growing species—the space is read as continuous from house to house, with the street causing a mere interruption to the texture of the predominantly linear green expanse. Dominating the houses on Moore Street, on the other hand, the vigorous melaleuca form a green nave resting on white trunks that divides the space as pedestrian-car-pedestrian [figure 128]. Finally, Beethoven Street stands as a case study of "before and after" or "if you don't do this, you'll get that" [see plate III]. Although ficus and magnolia are quite similar in their bearing and appropriateness as street trees, Meier and Beethoven streets lie worlds apart. Size, of course, is one issue, as the ficus firmly anchor the edge of the Modernique development. Ain's houses and Eckbo's plantings line only one side of Beethoven Street, with the other half displaying in full sun the hodgepodge of styles and yards that characterize most unplanned developments. Thus Mar Vista clearly demonstrated the superiority of intelligent planning as a vehicle for neighborhood amenity and identity.

The urban or suburban context dominated the equation among architecture, city, and landscape in the designs for Community Homes, Park Planned Homes, and Mar Vista. In contrast, landscape

126

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, 1948.

Gregory Ain, architect. Moore Street seen through an

entrance atrium.

[Julius Shulman ]

127

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles,

1948. Gregory Ain, architect. Meier Street, showing existing

mature eucalyptus as well as newly planted magnolia.

[Documents Collection ]

128

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, 1948.

Gregory Ain, architect. Moore Street today.

[Marc Treib, 1996 ]

weighed the balance in the site planning of Crestwood Hills and Wonderland Park, as if on such hilly terrain, the human hand, or its design, was to bow against nature.

After the collapse of the Community Homes project, several of its members joined the Mutual Housing Association. This group grew to include 500 families by the time construction on Crestwood Hills began in 1949 [figure 129]. Eckbo collaborated with architects Whitney Smith and Quincy Jones, and engineer Edgardo Contini to produce the site plan. The topography of the 835-acre tract, situated in Kenter Canyon in western Los Angeles, ranged from flat to 30 percent slopes. The plan grouped houses along the two major ridges, with community facilities spread over the sycamore-covered valley floor. The aim of the design was to preserve views and limit grading along the ridges, maintaining a "natural profile." In contrast, the lower parts of the site—dissected by canyons—required massive grading, thereby resulting in a constructed landscape of stepped terraces. The house plans, sited on quarter-acre lots, offered variations in the basic structure of rigid wood frame with either concrete footings, piers, or steel beams dependent on terrain conditions.

Between the lines of the account Eckbo published in Landscape for Living , we can read the landscape architect's distance from the project's underlying philosophy. Crestwood Hills stood as the concrete manifestation of his ever-present argument that natural need not be the antithesis of formal . The site merged a "rough primeval" character with the "well-to-do residential neighborhood" below.[84] To Eckbo, a sophisticated vegetation plan provided the link between these two poles of human intervention; it also articulated topographic units while minimizing the perception of steep declivities [figure 130]. To achieve such a balance, low broad species would be planted atop the hills, moving toward taller columnar species as the elevation receded. Olive trees dominated the ridges, with some pockets of palms acting as buttresses; avocado spread along the intermediate elevation, followed by a mix of cypress, cedar, and pine, and further down, eucalyptus; poplar complemented the existing sycamores on the valley floor and completed the palette. As in Mar Vista and Community Homes, trees held the key to neighborhood identity. But in Crestwood Hills, they added a caption to the reading of the site's revised topography.

129

Crestwood Hills (Mutual Housing Association). Perspective sketch of overall site.

Kenter Canyon, Los Angeles, 1947–51. Whitney Smith and Quincy Jones, architects;

Edgardo Contini, engineer; Garrett Eckbo, landscape architect.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

130

Crestwood Hills (Mutual Housing Association). Tree planting diagram.

Kenter Canyon, Los Angeles, circa 1948. The height and verticality of

species increase in inverse proportion to the elevation: from olive along

the ridges, to avocado, cedar, and eucalyptus, and to palm tree below.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

The elaborate planting scheme was judged by Eckbo's clients as too variegated, too exotic, and thus "unnatural." Having always held that the role of design was "to improve the relationship between people and the landscape around them," the designer found the rejection of his thoughtful, recognizable plan a major disappointment.[85] In denouncing the favoring of "mechanical pepper-and-salt naturalism" over the "development of unprecedented spatial relations and humanized landscapes," he brought into focus the problematic and sempiternal quest for reproducing the image of nature, as opposed to shaping nature. The eighteenth-century legacy of the English "picturesque" haunted, and still haunts, the landscape architecture profession and the public's perception of what is "natural." As Eckbo pointed out, "it has been said that 'nature has no pattern,' therefore we should have none."[86] Thus, detractors argued, the visible imprint of human beings on Kenter Canyon needed to be minimized—as if to redeem the manipulation of five hundred thousand cubic yards of earth from its primeval state.

Eckbo also designed typical garden plans for Crestwood Hills [figure 131]. These he labeled also as "unnatural," given their "hav[ing] form;" they recalled the plays in boundaries and spatial manipulation initiated in Contempoville. The various configurations of hedges and tree enclosures defined functional areas within the garden and established a formal dialogue with the house. While partially outlining the edges of the site, these vegetal screens and anchors also dissolved the lot lines through fragmentation, as they distorted the boundaries' angled planes. One of the gardens was not only formal—with irregular checkerboards of lawn, gravel, rough deep grass—but it showed, once again, how vegetation was made to override geometry with its texture, color, and shape [figure 132]. He displayed orange persimmon against gravel; juxtaposed contrasting patterns of dark and light foliage; chose gray-green spindly melaleuca to form one allée and classical, dark-glossy-leaved magnolia for another; and considered floral and foliage color as well as fruit-bearing capability.[87]

Eckbo's tree master plan was never implemented, and the landscape of Crestwood Hills became "a collection of private designs."[88] He later compared this project with Community Homes in terms of client spirit. To him, the liberal and communitarian spirit of the Cartoonist and Screenwriters' Guild members not only provided a

131

Crestwood Hills (Mutual Housing Association).

Typical garden plans. Kenter Canyon,

Los Angeles, circa 1948.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

132

Crestwood Hills (Mutual Housing Association).

Garden axonometric drawing.

Kenter Canyon, Los Angeles, 1947.

[ from The Californian]

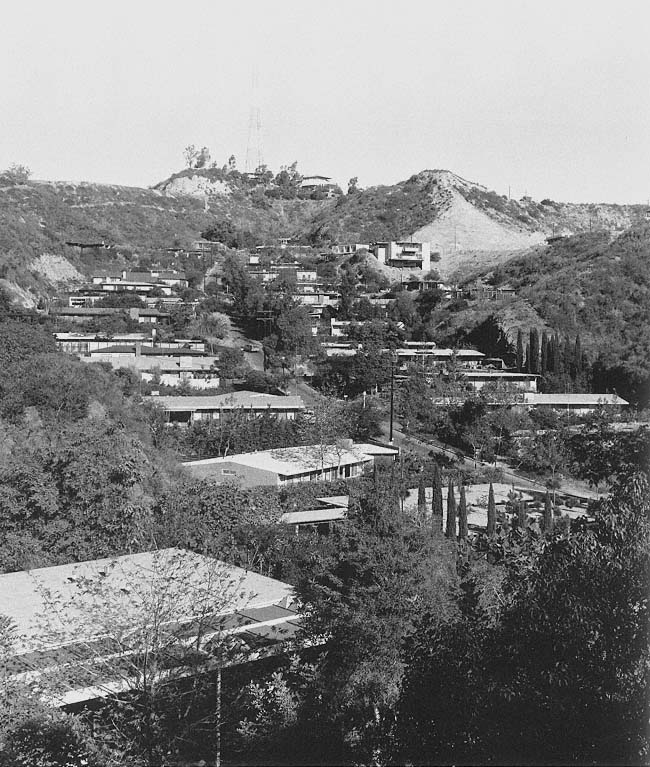

133

Wonderland Park. Overall view. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, mid-1950s.

[Documents Collection ]

driving force for the design process of Community Homes but also guaranteed—or as it happens, prevented—its realization as a whole and as an expression of the social foundations of housing. The clientele of Mutual Housing, in contrast, came from a varied professional horizon, to the point that the member list was described in a publication as resembling a "vocational guidance bulletin."[89] Eckbo saw its common goal as the pursuit of economic advantages rather than the idealism of better housing communities through an expression of grassroots democracy.[90]

Approximately thirty-five other alumni of the Community Homes venture joined forces again to create Wonderland Park in Laurel Canyon [figure 133]. The tract, already subdivided—that is with its lines and infrastructure engraved in legal stone—would be developed for sixty-seven homes. For an economy of time and finances, the land was regraded to form a series of terraces; to counter the adverse conditions that compacted fill presented for gardening, brush was buried as soil amendment. Eckbo designed about half of the gardens for the Wonderland cooperative—including his own—and the arboreal master-plan for the valley [figure 134]. His overall scheme recalled that for Crestwood Hills; foresting the lower third of the site with tall, upright Canary Island pine, Italian cypress, and lemon gum [figure 135]. Ascending the hill, the vegetation gradually softened toward the broader canopies of camphor, olive, and oak. Again Eckbo mitigated the drastic rise in topography with an inverse progression in the scale of trees.

Late in the 1950s Eckbo reformed his own backyard at Wonderland Park into the ALCOA Forecast Garden [see figures 79–82; plates XIII, XIV]. He extended the modules of architecture into the garden, with roof overhangs, pergolas, and trellises of aluminum mesh, thus effacing the distinction between the interior and exterior rooms. Eckbo treated aluminum—an atypical material for garden structures, yet one with a very contemporary presence—as he would plants. As he had manipulated the space with lines of evergreen and deciduous trees, partitions of hedges, heterogeneous orchards, and zigzagging flower beds, he would exploit aluminum for enclosure, texture, shadow, light diffusion, transparency, and color. It was perhaps the very nature of aluminum that made the ALCOA Forecast Garden modern at the time of its creation and almost passé within very few years.

134

Wonderland Park. Tree planting diagram.

Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, circa 1950.

[Documents Collection ]

135

Wonderland Park. Street view. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, mid-1950s.

[Documents Collection ]

The landscape design for Wonderland Park thus illustrated the two sides of Garrett Eckbo: Eckbo, the collective persona, for whom the landscape was a testing ground for the group against—as well as for—the individual; and Eckbo, experimenting in pure sculptural forms—the garden as a haven, yet a vital unit of the neighborhood landscape.

In time, Wonderland Park also signaled the decline of the public's interest in social formation and better community housing. And if Eckbo's career as a garden designer continued to expand, his involvement with the greater landscape shifted toward ecological planning to the detriment of aesthetics and design. This was a turn he seemed to regret in the early 1980s as he pondered that "it remain[ed] to be seen whether the environmental movement [would] widen [the gap] or make it possible to reunite people and nature."[91] His message is still read today in the theoretical impact exerted by seminal texts such as Landscape for Living , the concrete remnants of plantings for the migrant camps in the Central Valley, or the structures of gardens. But perhaps his greatest contribution remains the understanding of people in the forming of rural and urban community landscapes. Insisting that "people are the focal points, the terminal features, the final vitality of any spatial enclosure we may create," he would deem necessary to consider what he termed "the open center" a principle of design.[92] As the so-called New Urbanists argue for suburban developments sufficiently dense to warrant the addition of shops, schools, and facilities for commerce or recreation within walking distance—all of them ingredients that Eckbo advocated as essential to a successful postwar community—we must ask why we turn to the distant past for solutions to the problems of today.[93] Instead, Garrett Eckbo would direct us to learn from society and the site—with faith in our ability to create our own landscapes appropriate to our own situation and times.