Plates

Plate 1.

Asureshvar. Danda[*] Jatra. Devotee as Hanumana.

Plate 2.

Puri. Sahi Jatra. Risyasringa[*] and four princes.

Plate 3.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (courtesy Jubel Library, Baripada, dated

1833). Tadaki[*] and Rama.

Plate 4.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (Baripada, 1833). Rama hunts the magic

deer (detail of Figure 93).

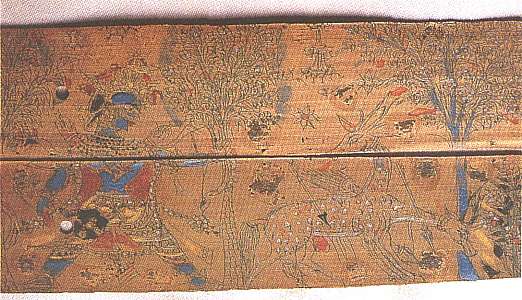

Plate 5.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (Baripada, 1833). Sita in fire, kidnap of

Maya Sita.

Plate 6.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (Baripada, 1833).

Rainy season on Mount Malyavan.

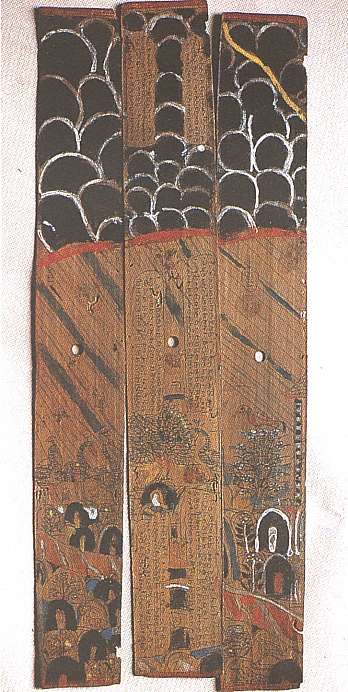

Plate 7.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (Baripada, 1833). Battle scene.

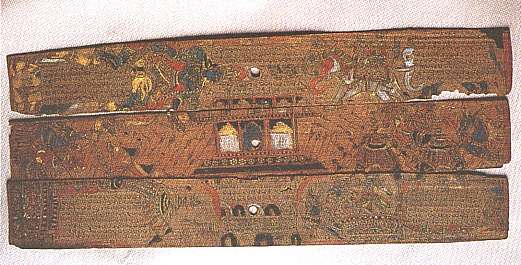

Plate 8.

Satrughna, Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] (Baripada, 1833). Ravana[*] and his wives.

Plate 9.

Dispersed Lavanyavati[*] (Jean and Francis Marshall Collection, San

Francisco). Bharata's visit.

Plate 10.

Lavanyavati[*] illustrated by Balabhadra Pathy (courtesy National

Museum of Indian Art, New Delhi). Rainy season on Mount Malyavan, f. 173.

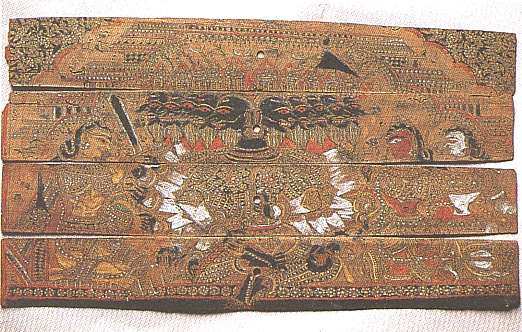

Plate 11.

Buguda, Virañchi Narayana[*] Temple, wall F.

Laksmana[*] straightening his arrow.

Plate 12.

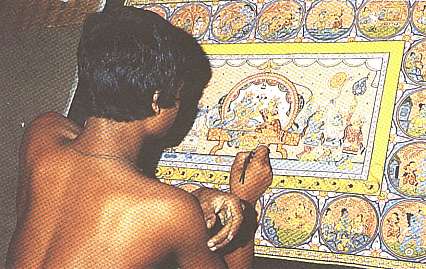

Apprentice at work on Ramayana[*] pata[*] in Jagannath Mahapatra's

house, Raghurajpur (cf. Figure 289A).

There is no reason to think that Michha Patajoshi knew the work of Satrughna, produced seventy years earlier, yet his copious and literal illustrations of this section include similar themes, along with an amusing whimsy Ravana's[*] bath, taken to win over Maricha, is scrupulously shown in all three major manuscripts of this artist (Figure 108). Michha Patajoshi's deer is our most winsome version of this subject, disporting itself playfully in the forest (Figure 116). Maya Sita is again appropriately indicated by the presence of the true Sita in a fire while the illusory one is kidnapped (Figure 109). Jatayu[*] , a somewhat comic bird, swallows and then spits out Ravana's[*] chariot, which incidentally has the same form, with a giant head below, as that of Buguda (Figure 117).[43] The swallowing is depicted in the contemporary, conceivably influential pats , or pictorial scrolls, that were carried around south Bengal by itinerant storytellers; but their composition consistently differs from Michha Patajoshi's.[44] ç I would therefore conclude that what may have been known in Orissa was the theme but not the Bengali images. Two scenes of the cowherds in each manuscript become an occasion for rural details. Thus the brothers chug their milk with gusto in Figure 129, and the Sabari offers them a mango with wide-eyed enthusiasm in Figure 118.[45] ç

In the brief account of the Lavanyavati[*] , Raghunath Prusti's prolongation of these events is striking. Illustration of the last couplet of verse 24 occupies folios 77v and 78r (Figures 186, 187), a space generally devoted to two or three couplets. Thus Prusti seems as charmed as Sita was by the frolicking deer, which he depicts twice with animation and accuracy, neatly graduating the size of spots on its extremities. Folio 78r places the main event in the center (Laksmana's[*] departure, leaving Sita to Ravana[*] ) and the two simultaneous offshoots on either side. The same three episodes occur side by side at Buguda but in the order in which most texts describe them—first on the right the hut, then the brothers with the deer, then Jatayu's[*] battle with Ravana[*] (Figure 202). Prusti seems to have deliberately rearranged them according to the logic of place (movement in relation to the hut) rather than a logic of time. His version of the brothers emphasizes the deer, and Sita stands more starkly alone in his depiction of the hut as an elegant cage. The telling device of the empty hut in the next scene seems to be Prusti's own invention,[46] effectively balancing Sita's sorrow in the crowded asoka grove with Rama's stark loneliness (Figure 188). The single missing leaf that follows must have illustrated a total of four couplets, whose more succinctly depicted events might have set off this emphatic sequence.

By contrast, the careful artist of the Round Lavanyavati[*] tells his story with the regularity of clockwork, each line occupying one-quarter or one-third of the space in every frame (Figures 17-20). In the case of the Sabari's gift of a mango, her extended arm serves to emphasize the difference in status between her and Rama (Figure 23) but lacks the simple sense of devotion found in Michha Patajoshi's version (Figure 118).

In the case of the Dispersed Lavanyavati[*] , a missing folio makes it impossible to assess this sequence as a whole. On the next folio that does survive, it is clear that this artist once again took great liberties with the plot sequence (Figure 149). Either this page must be read from right to left (an order virtually unknown in palm-leaf manuscripts, whose writing runs from left to right), or the order of the kidnap and the Sabari's gift has been reversed. This lady has little of the tribal

about her, and the impact of both scenes, with their delicate tracery of leaves, is courtly and elegant. Here prolepsis may underscore the parallel between feminine generosity in the two cases, establishing for the viewer that Sita did no wrong in giving alms to this stranger.

Balabhadra Pathy's Lavanyavati[*] is no more expansive for this portion than for the Ramayana[*] in general. Some scenes are particularly vivid, such as the denosing of the scampering, bug-eyed Surpanakha[*] (Figure 162). The fact that Ravana's[*] discussion with Maricha takes place by the ocean suggests that Pathy had in mind the Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] , where bathing is part of enlisting assistance. The illusory deer, a fanciful creature, more like an antelope than those of other versions, is shown repeatedly—cavorting in a narrow clearing, bounding through a thicket with magical ease while Rama struggles after it, and looking ruefully at the arrow shot through its neck with horizontal insistency (Figures 164, 165).[47] The ten-headed Ravana[*] and the cowherd's cows (Figures 166, 167) produce variety within the often mannered tracery of Pathy's work.

This manuscript is the only one I know in which the deer has a single head, although that is the case in about 40 percent of the recent pata[*] paintings. Certainly the two-headed type prevailed in Orissa in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although it was never mandatory; witness a pata[*] from before 1814, now in the British Museum.[48] Neither chronology nor region seems to explain its adoption. In fact, while the two-headed form of the illusory deer is more common in Orissa than elsewhere, it does occur with some frequency in western India from the fifteenth century on.[49] ç

I know of no three-headed version of the deer in this particular episode, although India is rife with multiheaded animals and the two-headed motif is part of that broad spectrum. One example of a three-headed deer occurs in an Orissan palm-leaf manuscript of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] as an unexplained space-filler at a later point when the surrounding text concerns Rama's adventures in Kiskindha[*] (Figure 79)[50]

If we search for a textual explanation for the two-headed form, none of the works explicitly illustrated in Orissa describes this detail. Yet it is mentioned in at least two other texts, one the prestigious early fifteenth-century Mahabharata of Sarala Dasa.[51] The second is one of numerous Ramalila[*] texts, that of Vaisya Sadasiva, composed in the eighteenth century.[52] ç These may represent, not a conclusive source for the motif, but rather indications that this image was widespread, particularly in the context of popular theater. In the Ramalilas[*] still performed in central Orissa, the deer is frequently represented by a two-headed wooden model pulled on wheels (Figure 44, Frontispiece).[53] ç Neither performance nor images suggest unanimity about the form of the deer, but the two-headed version was widely accepted in both theater and art. Popular performance might at least have reinforced the artists' tradition or choice.

The question remains, what do the two heads mean? In Gujarat, a straightforward explanation has been adduced: the deer moved fleetingly, one moment grazing, the next looking back.[54] This is to understand the motif as an extreme example of simultaneous narration, exceptional both in western India and in Orissa. I asked repeatedly about the meaning in Orissa and never received that answer, which is not to rule out the possibility that the image may also at times suggest

darting movement. Yet two-headed form is neither necessary nor sufficient for that interpretation. On the one hand, Pathy's slender single-headed deer creates a similar effect, demonstrating that this motif is not required to create a sense of motion. On the other hand, the dead body of the deer regularly retains two heads whenever it is shown, and in that situation motion is surely not intended (Figures 20, 88, 187, 215—the skin on which Rama sits—and 265).

In fact, both the chitrakaras and the public were generally stumped at first for an explanation. One might conclude that the real meaning has been lost. Given the variety of forms, I wonder if there ever was a single real meaning. The eminent Oriya scholar S. N. Rajguru supplied a precise and elegant interpretation, that the two heads correspond to the two sides of Maricha's nature, both good and bad. Others, however, concluded that it was simply the essence of illusion: the deer should be odd. Whether we opt for the specific, intellectual allegory or for the more generalized, popular interpretation may have more to do with our own ideological proclivities than with reasoned argument. Both rest on a respect for illusion, for ambiguity, for double entendre, and for divine power at work in confusion that is central to several texts we have been considering. This entire sequence of action becomes significant less as simple crux of plot than as the epitome of illusion. When Maya Sita confronts the Maya Mriga[*] and is kidnapped by Maya-Ravana[*] , the entire story rises to a level of complex relativism that dizzies even the postmodernist. I would like to argue that the very open-endedness of the symbolism of the two-headed deer best explains its tenacity in Orissa.