Preferred Citation: Haas, Ernst B. When Knowledge is Power: Three Models of Change in International Organizations. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6489p0mp/

| When Knowledge Is PowerThree Models of Change in International OrganizationsErnst B. HaasUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Haas, Ernst B. When Knowledge is Power: Three Models of Change in International Organizations. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6489p0mp/

Acknowledgments

This little book is the result of several unsatisfactory previous attempts to grapple with the relationship between the behavior of states in multilateral encounters and the use by states of changing knowledge about nature and human affairs. It is also the result of previous efforts to ruminate about the record and fate of major international organizations. I hope I have improved on previous conceptualizations and successes in integrating the two themes.

The main stimulus for doing so was the experience of teaching a graduate seminar on international organization which, each time it was offered, left me somewhat dissatisfied. I greatly appreciate the forbearance of the participating students and value their enthusiastic and generous work in testing and improving my suggestions. I want to single out Edward Alden, Khalid Al-Ohaly, Thomas Bickford, Kenneth Conca, James Fearon, Jason McDonald, Stevens Tucker, and Takahiro Yamada as especially helpful.

Another major source of inspiration was the Berkeley Colloquium on Global Stability, a faculty group funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, devoted to the discussion of continuities and discontinuities between ecological and social theory as they pertain to international affairs. I thank my colleagues Paul Craig, John Harte, Todd Laporte, Philippe Martin, Richard Norgaard, Gene Rochlin, and Melvin Webber for more help than they realize they have given me.

Robert O. Keohane, apparently intrigued if not persuaded by these ideas, was kind enough to invite me in 1985, 1986, and 1988 to address the colloquium on international political economy he chairs at the Harvard University Center for International Affairs. In addition,

he went far beyond the call of duty in giving me a powerful critique of two drafts; he ought to be gratified by the additional work he made me do. David Collier was kind enough to let me test these ideas in his seminar on methodology of comparative studies in Berkeley.

Thanks are due to the Ford Foundation, whose grant funding a Pacific Coast colloquium on international collaboration and institutions permitted the holding of a conference in December of 1987 devoted to a discussion of the first draft.

Further constructive comments on the first draft were received from Emanuel Adler, Peter Cowhey, Jeffrey Hart, Edward Miles, John Gerard Ruggie, and Wayne Sandholtz. I thank them for the many good suggestions on which I acted and ask their forbearance for the ones I ignored. I owe a big and continuing debt to Hildegarde Haas for sometimes reminding me that it is unlikely that any single scholar will ever achieve closure.

1

Multilateralism, Knowledge, and Power

Imagine historians in the twenty-third century busily interpreting the events and documents of international relations in the second half of the twentieth century. They would note, of course, that the world was organized into separate sovereign states and that their number had tripled over the previous half-century. But they would note another curious phenomenon: even though the people who ruled these states seemed to treasure their mutual independence as much as ever, they also built an imposing network of organizations that had the task of managing problems that these states experienced in common. Sometimes these international organizations had the task of transferring wealth from the richer to the poorer states. At other times they were asked to make and monitor rules by which all the states had agreed to live. At still other times the task of these organizations was the prevention of conflict among states. In short, rulers seemed to concede that without institutionalized cooperation among their states, life would be more difficult, dreary, and dangerous. Proof lies in the number and kind of such organizations, which increased at a stupendous rate after 1945.

Our historians would also note a second phenomenon, which gathered force around 1980. Everybody seemed to be disappointed with these organizations. Some of the most powerful states sought to disengage from them. Others demanded more benefits but received fewer. The very idea of moderating the logic of the cohabitation of 160 sovereign units on the same planet with institutionalized cooperation lost its appeal. Did international organizations disappear to give rise to alternative modes of collaboration? Did states examine the reasons for their disappointment and reform the network of international organizations? Did rulers question the very principle of a world order based on sovereign and competing states? Our historians know the eventual outcome. We do not. We can only speculate about the future of international cooperation and wonder whether it will make use of international organizations. I wish to construct concepts that might advance the enterprise of systematic speculation.

The Argument Summarized

Since the speculation is to be systematic, my underlying assumptions require specification. They are as follows: All international organizations are deliberately designed by their founders to "solve problems" that require collaborative action for a solution. No collaboration is conceivable except on the basis of explicit articulated interests. What are the interests? Contrary to lay usage, interests are not the opposite of ideals or values. An actor's sense of self-interest includes the desire to hedge against uncertainty, to minimize risk. One cannot have a notion of risk without some experience with choices that turned out to be less than optimal; one's interests are shaped by one's experiences. But one's satisfaction with an experience is a function of what is ideally desired, a function of one's values. Interests cannot be articulated without values. Far from (ideal) values being pitted against (material) interests, interests are unintelligible without a sense of values-to-be-realized. The interests to be realized by collaborative action are an expression of the actors' values.

My speculations concern the future of international organizations, but my assumptions force me to consider the future as a function of the history of collaboration as that history is experienced in the minds

of collective actors: national and international bureaucracies. That history is the way "the problem to be solved" was seen at various times by the actors. What this book seeks to explain, then, is the change in the definition of the problem to be solved by a given organization . Let us take an example. In 1945 the problem the World Bank was to solve was how most speedily to rebuild war-ravaged Europe. By 1955 the problem the bank was to solve was how most effectively to spur industrial growth in the developing countries. By 1975 the problem to be solved had become the elimination of poverty in the Third World. The task of my book is to explain the change in problem definition, to make clear whether and how the implicit theories held by actors changed.

I shall argue that problems are redefined through one of two complicated processes that I call "adaptation" and "learning." These processes differ in their dependence on new knowledge that may be introduced into decision making:

|

I return to the example of the World Bank. Suppose the bank had been asked to solve problems by simply adding new tasks to old ones,

without seeking to justify industrialization as a means toward the eradication of poverty, without explaining infrastructure development projects as a means toward industrial growth, which in turn was eventually seen as a means for eliminating poverty. There was no new theory of economic development, and no cohesive group of experts that "sold" that theory to the bank's management. I call this sequence "change by adaptation." If, conversely, these successive new purposes came about as the result of a systematic pattern of subsuming new means under new ends, legitimated by a new theory of economic development advocated by an epistemic community, then the pattern conforms to what I call "learning."

I argue that adaptation can take place in two different settings, each a distinct model of organizational development. One, labeled "incremental growth," features the successive augmentation of an organization's program as actors add new tasks to older ones without any change in the organization's decision-making dynamics or mode of choosing. The other, labeled "turbulent nongrowth," involves major changes in organizational decision making: ends no longer cohere; internal consensus on both ends and means disintegrates. In contrast, learning is associated with a model of organizational change I call "managed interdependence," in which the reexamination of purposes is brought about by knowledge-mediated decision-making dynamics.

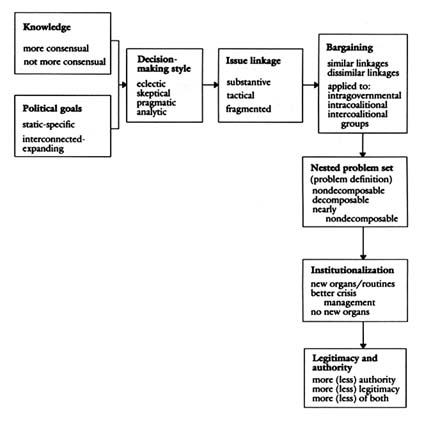

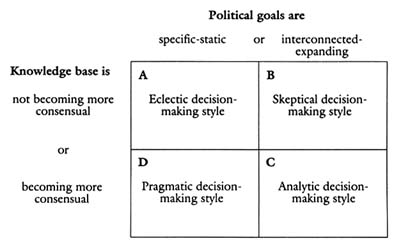

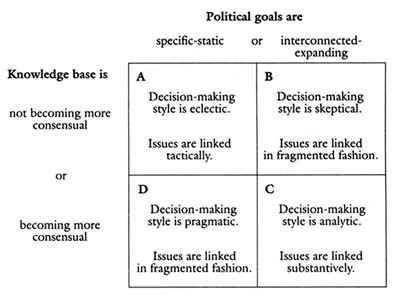

The point of the book is to suggest when and where each model prevails, how a given organization can change from resembling one model to resembling one of the others, and how adaptation can give way to learning and learning to adaptation. Therefore, a set of descriptive variables is introduced to make possible the delineation of key conditions and attributes that vary from model to model. These descriptive variables include the setting in which international organizations operate, the power they have at their disposal, and the modes of behavior typical in their operations.

Description, however, is not enough to permit us to make the judgments we seek. A second set of variables is provided to make possible an evaluation of the variation disclosed by studying the descriptive variables. These evaluative concepts stress the types of knowledge used by the actors in making choices, their political objectives, and the manner in which issues being negotiated are linked into packages.

Further evaluations are made about the type of bargaining produced by issue linkage, whether these bargains result in agreement on new ways of conceptualizing the problems to be solved, and whether new problem sets imply institutional changes leading to gains (or losses) in the legitimacy and authority enjoyed by the organization.

I foreshadow some conclusions that will be demonstrated in greater detail later. The World Bank began life in conformity with the incremental-growth model and later developed into the managed-interdependence model. The United Nations' (U.N.) collective-security practices degenerated from incremental growth into the turbulent nongrowth pattern; the U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) always functioned in conformity with the turbulent nongrowth model. In the World Bank no decline in organizational power occurred. In fact, the president's autonomous ability to lead has increased over the years; merit remains the principle for selecting staff; outside consultants always serve in their personal capacity. Over the years, issue linkage was increasingly informed by technical knowledge and by political objectives of a progressively more complex and interconnected type. As new and more elaborate institutional practices developed, these also became more authoritative in the eyes of the membership, even if they did not become more legitimate as well. The innovations summarized as "peacekeeping" and associated with the special crisis management leadership style of Dag Hammarskjöld suggest that in 1956 U.N. activity relating to collective security conformed to the incremental-growth model, too. But unlike the bank, the United Nations thirty years later has become the victim of turbulent nongrowth. Earlier institutionalization and increases in authority were dissipated, no improvements in technical knowledge informed decision making, political goals became simpler and more immediacy oriented, and the leadership of the secretary-general was all but invisible. Possibly, however, the successes scored by Javier Pérez de Cuéllar in 1988 will reverse this trend. UNESCO, finally, never enjoyed a coherent program informed by consensual knowledge and agreed political objectives; it suffered no decline in institutionalization and power because it had very little of these in the first place. Both authority and legitimacy declined to a nadir in 1986 after decades of internal controversy over the organization's basic mission.

So what? How does the mapping of movement from one model to another help us with the future of international organizations? I want to answer a question that not only incorporates my own uncertainty about that future but also seeks to generalize from the uncertainties against which political actors try to protect themselves. We assume that their attempts are informed by interests that are shaped by implicit theories. States acting on their perceived interests, not scholars writing books, are the architects that will design the international organizations of the future. These interests are informed by the values political leaders seek to defend, not by the ideals of observers. Actors carry in their heads the values that shape the issues contained in their briefing papers. My effort to conceptualize the process of coping with uncertainty is based on this given. Scholarly concern with the question of how we might approach the international organizations of the future relies on understanding how self-conscious actors can learn to design organizations that will give them more satisfaction than the generation of international organizations with which we are familiar. If my demonstration in this book is persuasive, it will give us the tools for saying, "If an organization of type A regularly produces certain outcomes, then this type will (or will not) serve the perceived needs of its members; therefore they will seek to design an organization of type B if they are dissatisfied or will retain type A if they are happy."

Only idealists would presume to prescribe for the future by using their personal values as the definer of suggestions. I am not an idealist. The suggestions for a particular type of organizational learning developed in the final chapter are consistent with the nonidealistic line of analysis pursued in the body of the book even though they also project my views as to what ought to be learned.

A Typology Is Not a Theory

To avoid even the appearance of inflated claims, I maintain that the typological argument I offer falls short of constituting a theory. The demonstrations just made about the World Bank, UNESCO, and the United Nations are not full explanations of what happened to these organizations; nor do they display all the causes for these events. No pretense is made that these partial post hoc explanations provide all

the ingredients needed for an informed prediction. Why then offer a typology of models of change?

I want to inquire into only one aspect of organizational life: why and how actors change their explicit or implicit views about what they see as a problem requiring collaborative measures for a solution. The "problem" can be any item on the international agenda. My dependent variable is change in the explicit or implicit view of actors in international organizations about the nature of a "problem." My inquiry, however, depends on my being able (1) to specify the interests and values held by actors and (2) to show how actors redefine interests and perhaps values in response to earlier disappointments. Moreover, I want to determine whether the processes that take place inside international organizations can be credited with the redefinition of interests and values. The idealist takes for granted that such redefining is likely to occur; scholars who stress the predominance of bureaucracies and political forces at the national capitals place the locus of change elsewhere. Granting that important changes in perception are unlikely to occur primarily in Geneva and New York, we must nevertheless hold open the possibility that some of the influences experienced there have a role in the national decision-making process that produces the changes we seek to explore. If that is true, then it also makes sense to observe international organizations in their possible role as innovators. And if international organizations can innovate, then we can inquire whether and when governments look to them as mechanisms for delivering newly desired goods and services. If governments think of international organizations as innovators, finally, we are entitled to ask how they go about redesigning international organizations to improve the solution of a newly redefined set of problems.

In what follows, then, I shall not be testing a theory. I merely experiment with the explanatory power of ideal types of organizations that reflect my conviction that the knowledge actors carry in their heads and project in their international encounters significantly shapes their behavior and expectations. My perspective is more permissive of the workings of volition, of a kind of free will, than is allowed by many popular theories of international politics. If my stance is not "idealistic," it is not "structural" either.

The structuralist argues that international collaboration of the multilateral

kind is intended to provide a collective good for the parties that bilateral relations could not provide. The provision of that good, in turn, may result in a more harmonious world—though the harmony is likely to be confined to expectations related solely to the good in question. It probably cannot be generalized into the utopia associated with idealism. As for international organizations, they are important in this causal chain only if they are necessary for providing the collective good. International organizations, therefore, are not given a privileged place in the causal chain of the structuralist.

I disagree with this stance because it tends to overstate the constraints on choice and to understate decision makers' continuing enmeshment in past experiences with collaboration mediated by international organizations. Structuralism seeks to discover various deep-seated constraints on the freedom of actors to choose. Although organizations, like any other institutions, can act as constraints, I want to look at them as fora for choosing innovations. Structural constraints may be implicit in the logic of situations, such as the condition of strategic interdependence in anarchic international systems. Belief in the power of such constraints depends on the assumption that actors respond only to present incentives and disincentives, that they never try to "climb out" of the system to reshape opportunities for gain. Strategic interdependence as a permanent constraint is compelling only as long as there is no evidence that somebody works actively toward changing the rules of the game. Modern international life is replete with such efforts. However, it is equally true that the kinds of constraints on choice that structuralists stress provide the most telling explanation as to why new international organizations are created in the first place. But if we stop our inquiry with this explanation, we never proceed to ask the questions that interest me, questions about the role of changing knowledge in the redefinition of interests.[1]

I call attention to the discovery on the part of Snyder and Diesing that even the situations of crisis they investigated under structuralist assumptions showed a wide variety of actual features with too much variation in behavior and outcome to permit the positing of a small number of structural constraints as determinants. See Glenn Snyder and Paul Diesing, Conflict Among Nations (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977), chap. 7. Robert O. Keohane, in After Hegemony (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984), concludes that even under microeconomic-structural assumptions the behavior of states in regimes is highly variable and not reliably determined by structuralist assumptions. The case for institutional constraints on behavior is explored and duly qualified by James G. March and Johan P. Olsen in "The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life," American Political Science Review 78 (1984): 734-49. My nonstructural epistemological stance is spelled out in greater detail in "Why Collaborate?" World Politics 32 (April 1980), and "Words Can Hurt You," International Organization 36 (Spring 1982). The present essay is an effort to extend and apply this view to the future of international organizations.

Theorists and metatheorists customarily differ on how a given writer is to be classified in a field of contending approaches. Even though I reject the labels "idealist" and "liberal" for my theoretical position because of the characteristics I associate with the schools of thought properly so described, I am quite comfortable with being called a "neoidealist," if we follow the description of that stance offered by Charles W. Kegley, Jr., in "Neo-Idealism," Ethics and International Affairs 2 (1988): 173-98, although I would be most uncomfortable being identified as a "neoliberal" as defined by Joseph S. Nye, Jr., in "Neorealism and Neoliberalism," World Politics 40 (January 1988): 235-51. I am most content, however, to be classed with the nonrationalistic (as he defines them) "reflective" writers elaborated in Robert O. Keohane, "International Institutions: Two Approaches," International Studies Quarterly 32 (December 1988).

Unlike structuralists, neorealists, game theorists, and theorists of regimes, I am not offering a theory; at best I am offering a probe that might lead to a theory. I am not testing my approach against rival explanations because other approaches are not rivals. Game theory or structural explanations do not "fit better" than explanations of change derived from the interplay of knowledge and political objectives, from cognitive and perceptual observations; they "fit differently." Nor is it

my purpose to subsume or colonize other theories, or to assert my hegemony over them. Other explanations, given the questions other scholars raise, may be as valid as mine. My effort should be understood as complementary to theirs, not as an approach with unique power. Cognitive explanations coexist, epistemologically speaking, with other approaches to the study of international organizations; they do not supplant them. If I persuade the reader that the history of an organization can be viewed in the context of cognitive variables, then the reader will interpret that history in a novel form, without rendering all other interpretations obsolete. But the success of my claim to novelty still falls short of a real theory.[2]

A complete theory would have to offer an explanation of what occurred in an international organization even if the emphasis on changes in the mixture of knowledge and political objective fails. An explanation that stresses changes in available knowledge ought to be able to offer an account of the origin of that knowledge. A claim that issue linkages and bargains that represent different mixtures of knowledge and political goals explain different modes of organizational development ought to be able to specify the kinds of knowledge and goals most prominent in that history. I am able to specify only that a certain mixture was or was not present, not why it was present. I am in a position to show only that knowledge was or was not available, not how or why the actors required it.

Nor do the three models around which my interpretations are built constitute a true theory. They remain Weberian ideal types; together they constitute a typology for conceptualizing organizational change, for summing up whether and how adaptation or learning occurs. Yet the models are not just heuristic; they are intended to be "real," albeit not exhaustive, representations of what took place. They seek to abstract selectively (but not arbitrarily) from a historical series of events. The crucial point is this: the notion of causation implicit in these models is as elusive and as nonlinear as in all of Weber's typologies. My approach differs sharply from the more direct ideas of causation embedded in behavioral and in rational-choice approaches to the phenomena studied here because it rejects simple notions of causality.

Basically, I anchor my approach on this bet: the knowledge available about "the problem" at issue influences the way decision makers define the interest at stake in the solution to the problem; political objectives and technical knowledge are combined to arrive at the conception of what constitutes one's interest. But since decision makers are sentient and self-reflective beings, the conceptualization cannot stop here because decision makers take available knowledge into account, including the memory of past efforts to define and solve "the problem." They know that their knowledge is approximate and incomplete. Being aware of the limits of one's knowledge also influences one's choices. Being critical about one's knowledge implies a readiness to reconsider the finality of what one knows and therefore to be willing to redefine the problem.

This point distinguishes my approach from that of theorists of rational

choice who are inspired by microeconomics. In the logic of game theory, for instance, what matters is not the history of a perceived preference or the way a utility (interest?) came into being, but the mere fact that at the crucial "choice points," interests are what they are because preferences are as they are stipulated in game theory. It makes sense to speak of shared interests if, at the choice point, the separate interests of the bargainers happen to be sufficiently similar to permit an agreement. In my approach the decision makers are thought to be concerned with causation, with the reasons why a particular definition of their interests matter, as compared with other possible definitions. My analysis must be concerned, therefore, with the question of why particular demands are linked into packages, why problems are conceived in relatively simple or in very complex ways. Implicit or explicit theories of causation in the actors' minds imply degrees of knowledge, not merely momentarily shared interests. My theory of causation must reflect and accommodate the notions of causation assumed to be in the minds of the decision makers, notions that are true to the insight that there is always another turn of the cognitive screw to be considered.

I reiterate: the typologies that result from this mode of analysis are not truly representative of all of reality. They capture types of behavior, clusters of traits, bundles of results from antecedent regularities in bureaucratic perception that are logically possible, but not necessarily encountered frequently. Many of Weber's typologies, although exhaustive in the sociological and cultural dimensions he wished to represent, nevertheless produced sparsely populated cells. We will find that the managed-interdependence model is rarely encountered in the real world and that learning is far less common than adaptation. But then so is charismatic leadership and the routinization of charisma into bureaucratic practice.

Therefore, we will not follow the mode of demonstration preferred by those who work in the behavioral tradition. We will not seek to cull from our large list of descriptive variables those clusters of traits that most frequently "predict" (or are associated with) either successful adaptation or successful learning. Many of the descriptive variables will be shown to be weakly associated with any pattern, any regularities; some will not vary from type to type. Nevertheless, such variables will

not be permitted to "drop out" even though they explain nothing behavioral. They are real because they describe international organizations. They matter in pinpointing what is unique about international organizations, and they may turn up as more powerful in some later analysis or some new set of historical circumstances. Remaining true to a typological commitment demands that the traditional canons of causal theorizing be sacrificed to a less economical procedure that forgoes the search for clusters or straight paths as unique explanations. I am, after all, using systematic speculation and historical reconstruction to anticipate events that have yet to occur.

Knowledge, Power, and Interest

My typological approach is anchored on an additional bet, similar to the first one but less moderate: change in human aspirations and human institutions over long periods is caused mostly by the way knowledge about nature and about society is married to political interests and objectives. I am not merely asserting that changes in scientific understanding trigger technological innovations, which are then seized upon by political actors, though this much is certainly true. I am also asserting that as scientific knowledge becomes common knowledge and as technological innovation is linked to institutional tinkering, the very mode of scientific inquiry infects the way political actors think. Science, in short, influences the way politics is done. Science becomes a component of politics because the scientific way of grasping reality is used to define the interests that political actors articulate and defend. The doings of actors can then be described by observers as an exercise of defining and realizing interests informed by changing scientific knowledge about man and nature.

Therefore, it is as unnecessary as it is misleading to juxtapose as rival explanations the following: science to politics, knowledge to power or interest, consensual knowledge to common interests. We do ourselves no good by pretending that scientists have the key for giving us peace and plenty; but we do no better in holding that politicians and capitalists, in defending their immediate interests with superior power, stop creative innovation dead in its tracks. We overestimate the resistance to innovation on the part of politicians and the commitment

to change on the part of the purveyors of knowledge if we associate science and knowledge with good, with reform, with disinterested behavior, while saddling political actors with the defense of vested interests. When knowledge becomes consensual, we ought to expect politicians to use it in helping them to define their interests; we should not suppose that knowledge is opposed to interest. Once this juxtaposition is abandoned, it becomes clear that a desire to defend some interests by invoking superior power by no means prevents the defense of others by means of institutional innovations. Superior power is even used to force innovations legitimated by new knowledge, while knowledge-legitimated interest can equally well be used to argue against innovation.

Economists prefer to explain events by stressing the interests that motivate actors: coalitions of actors are thought capable of action only if they succeed in defining their common interests . Political scientists like to explain events in terms of the power to impose preferences on allies and antagonists. Sociologists tend to put the emphasis on structured or institutionalized norms and to find the origin of such norms in the hegemonial power of some group or class. My claim is that these formulations are consistent with the use of knowledge in decision making. My argument is that we need not pit these divergent formulations against each other as explanations of human choice. We are entitled to hold that interests can be (but need not be) informed by available knowledge, and that power is normally used to translate knowledge-informed interests into policy and programs. My concern is to analyze those situations in which interests are so informed and the exercise of power is so motivated, not to deal with all instances of interests, norms, and power as triggers of choice.

I return to the case of the World Bank to illustrate the possible convergence of explanations combining knowledge with interest and power. In the late 1960s the bank changed its basic philosophy of development lending from supporting infrastructure projects that were relatively remote from the direct experiences of poor people—hence the reliance on the theory of trickle-down—to the policy of supporting the advancement of basic human needs, with its implication of much more direct and intrusive intervention in the borrowers' domestic affairs in order to gain access to their poor citizens. Was new knowledge

used in motivating the shift? The shift occurred because economists and other development specialists had serious doubts about the adequacy of trickle-down policies and claimed that new techniques were becoming available to help the poor more directly. Was this knowledge generally accepted? This knowledge was generally accepted only by the coalition of donors that dominates the bank; the borrowers frequently opposed the shift and argued that the basic-human-needs approach was not in their interest. Was the shift consistent with the interests of the dominant coalition? Indeed it was, because the coalition's common interest in supporting economic development appeared to be implemented more effectively by virtue of the new knowledge.

My account shows how interest informed by knowledge reinforces the explanation of what occurred. What about power? Let us keep in mind that there are at least three different ways of thinking about power in these situations. If the hegemonial power of the capitalist class—as expressed in the instructions issued to the delegates of the donor countries—is considered, then the decision of the bank is an expression of the persuasiveness and influence of that class in foisting a realistic conception of the common interest on the dominant coalition, even though it may also be an instance of false consciousness. Suppose we ignore Gramsci and think of power as the straightforward imposition of the view of the strongest. Even though the United States is the single most powerful member of the bank, its position is not strong enough to enable it to dictate bank policy (in part because the U.S. presidents of the bank often entertained views at variance with opinions within the U.S. government). Power as direct imposition does not explain anything.[3]

The same lesson emerges from another episode in the history of the World Bank. During the 1980s the U.S. Congress sought to link the authorization of the United States' financial contribution to instructions that no loans should be made to governments that violated a number of congressional preferences in the field of economic policy and the status of human rights. U.S. representatives duly voted against such loans, but in most instances the bank's decision was made in disregard of congressional directives and U.S. votes because the other members of the bank's dominant coalition disagreed with the U.S. definition of interests; the United States' preference did not become the common interest of the coalition. Moreover, the European countries and Japan disputed the U.S. effort to "politicize" the bank's lending policy, arguing that a knowledge of economic development needs makes such efforts illegitimate. The United States' efforts to change the knowledge-informed interests failed.

That leaves a conception of power as the ability of a stable coalition to impose its will simply by virtue of its superior voting strength or as a result of its Gramscian ability to socialize and persuade its opponents into the position the coalition prefers. The new policy, then, is the common interest of the coalition, arrived at by negotiations utilizing knowledge and imposed by threat or verbal guile on the unwilling borrowers. Far from being a rival explanation of what occurred to explanations that rely on interest informed by knowledge, power simply enables us to give a more complete account without having to offer sacrifices at the jealous conceptual altars of any single social science profession.Why International Organizations Are Important as Innovators

I am arguing that some, not all, innovations in international life result from the experience of decision makers in international organizations. I am suggesting that we study multilateral processes as agents of change, not that they are the only, or even the most important, such agents. Multilateral processes provide one avenue for the transideological sharing of meanings in human discourse, not the only one. Much more may be going on in bilateral encounters and in informal contacts outside the organizational forum. But since my task is the study of international organizations, I need to stress the role of these entities in mounting innovations without denying the importance of other channels.

Experiences such as the World Bank's permit us to use the history of key international organizations as diagnostic devices for testing when and where knowledge infects multilateral decision making. I want to explore whether international organizations can provide, or have provided, a boundedly rational forum for the mounting of innovations, not a forum for furnishing a collective good determined on the basis of optimization. If we identify the manner of attaining the collective good with pure rational choice, we forget that the choice to be made is not "pure" because it is constrained by what the choosers have already experienced.[4]

James G. March, one of the theorists of decisions in organizations on whom I rely heavily, clearly explained why this approach is not considered to be in the tradition of pure rational-choice theories. Such theories "portray decision-making as intentional, consequential, and optimizing. That is, they assume that decisions are based on preferences (e.g., wants, needs, values, goals, interests, subjective utilities) and expectations about outcomes associated with different alternative actions. And they assume that the best possible alternative (in terms of its consequences for a decision maker's preferences) is chosen" (James G. March, Decisions and Organizations [London: Basil Blackwell, 1981], 1-2). The decision-making theory of direct concern to me is that which covers decision making "under ambiguity," the opposite of the conditions associated with rational-choice theories derived from microeconomics. The "correctness" of such decisions is always a matter of debate and can never be ascertained in the absence of considerable historical distance from the events. For a telling illustration of the kind of social rationality associated with decisions made in and by organizations, see Ronald Dore's discussion of "relational contracting" in "Goodwill and the Spirit of Market Capitalism," British Journal of Sociology 34 (December 1983): 459-82.

The game, for them, started some time ago. They are still enmeshed in its consequences and may seek to change the rules if they are unhappy with them. The fact is that the disappointments were, for the most part, associated with policies that were filtered through, and derived much of their legitimacy from, their place on a multilateral agenda. This is true even though such policies usually originated in the politics, the bureaucracies, and the think tanks of the member states. International organizations are part of everybody's experience because they are mediators of policies. They are a part of the international repertory of fora that talk about and authorize innovation. Hence we can study them as agents of innovation.We can do more. We can also make observations about relative effectiveness in the performance of these organizations and offer suggestions on how to improve effectiveness. In other words, we can contribute

to effective innovation on the basis of critical typological study, a task I undertake in chapter 9.

My treatment takes for granted that the goals valued by the states that set up organizations are the single most important determinant of later events. Nevertheless, such things as the task environment in which the organization must operate, its choice of core technology to carry out its tasks, and the institutional structure imposed on the staff must influence and probably constrain the attainment of these goals. A concern with institutional innovation must therefore consider environment, structure, and technology along with changing or constant goals.[5]

Gayl D. Ness and Steven Brechin, "Bridging the Gap: International Organizations as Organizations," International Organization 42 (Winter 1988), offer a detailed list of suggestions along these lines, on which my treatment draws.

It is useful to think about the theoretical literature on organizations as being concerned primarily either with decision making or with seeking to explain the persistence of structural forms. The literature on which I rely is essentially the literature on decision making constrained by organizational forms and practices. I am only incidentally interested in the persistence of organizational forms and make no consistent use of the literature in that area, though this theme will make a rather prominent appearance in the final chapter.

Must organizations remain the tools their creators have in mind when they set them up—means toward the attainment of some end valued by the creators? Or, alternatively, can international organizations become ends in their own right, become valued as institutions quite apart from the services they were initially expected to perform? If so, what kinds of innovations can or should be designed to bring about such a transition? One might also ask whether effectiveness is good for the survival and prospects of the organization as opposed to the welfare of the world in general; the two outcomes need not be mutually supportive. If they turn out to be contradictory, we might then think of design suggestions to mitigate the contradiction.

Some organizations are hierarchically structured; others are flat. Possibly, each form is optimal for the performance of some task, but not all tasks. Possibly, structure and effective performance are not well matched. If so, our comparative typological study may enable us to offer suggestions on how to adapt structure to effective performance. All organizations select a "core technology" to do their job, and the character of that technology interacts with institutional structure and task environment. It is possible, however, that the technology is not optimal for good performance, or not well integrated with the task environment or the structure. Innovations in design made apparent by historical study may then become appropriate. So can rearrangements in institutional structure, especially when it becomes apparent that better performance requires a different coordinate arrangement among several organizations active in the field. Our first step, then, is the application of organization theory to our study.

2

International Organizations: Adapters or Learners?

I wish to discover whether those who act on behalf of states believe that international organizations have been used effectively for collective problem solving or whether they ought to be used differently, more effectively. Collective problem solving among 160-odd states of widely different cultural commitments and with divergent historical memories would seem to depend on the ability to transcend cultural and historical boundaries, to establish transcultural and transideological shared meanings. Far from being a one-time event, the sharing of meanings is a continuous activity, partly mediated through the work of international organizations. These entities change the way they attempt to solve problems as their members debate effectiveness; they change by either adapting or learning. In this chapter I explore the difference between the two modes of change. International organizations are "satisficers," not optimizers. Changing them toward greater effectiveness involves the analysts' judgments about the ability of political institutions to act as innovators; this chapter explores that ability. Innovation, adaptation,

and learning, in turn, depend on the knowledge available to those who worry about the effectiveness of international organizations. Therefore, the first task of this chapter must be the exploration of the notion of consensual knowledge.

International Organizations as Problem Solvers

Designing an international organization is a political activity; it does not resemble problem solving in architecture. International organizations are coalitions of coalitions. They are animated by coalitions of states acting out their interests; these international coalitions often are expressions of coalitions of interests at the national level, both bureaucratic and societal. Domestic and international coalitions interact.[1]

Robert Gilpin coined the term "coalition of coalitions" to describe decision making by a state; the application to international organizations is mine. See Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 18-19. Robert Putnam uses the same term to develop a theory of national-cum-international bargaining that is very similar to my application. See his "Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games," International Organization 42 (Summer 1988): 427-60.

Design is a function of how the members of such coalitions think about their interests and values, what compromises they can strike, how they can come to reconsider and revalue their interests. Hence I shall draw on "political" organization theory to develop concepts about adaptation and learning, not on psychological, managerial, or other extant types.[2]Argyris and Schon distinguished "political" organization theory from five other types: organizations as group, agent, structure, system, and culture. Although the types are not mutually exclusive, the authors describe a political emphasis thus:)

Organizations are primarily understandable as interest groups for the control of resources and territory. Organizations are themselves made up of contending parties, and in order to understand the behavior of organizations one must understand the nature of internal and external conflicts, the distribution of power among contending groups, and the processes by which conflicts of powers result in dominance, submission, compromise or stalemate. (Chris Argyris and Donald A. Schon, Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective [Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1978], 328)

Learning, in a political perspective—they argue—can be studied in two ways: first, as a game of strategy, in which the analyst puts himself into the minds of the actors; and, second, as a way by which the actors achieve "collective awareness of the processes of contention in which they are engaged, gaining thereby the possibility of converting contention into cooperation" (ibid., 329).)

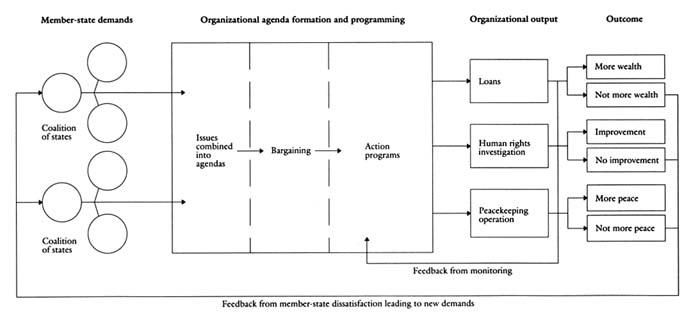

Let us suppose that after an initial period of satisfaction with the performance of an international organization, certain member states have become disillusioned with the ability of the organization to solve problems. I wish to discover whether member-state dissatisfaction has enabled the organizations to learn how to solve problems collectively so as once more to give greater satisfaction. We therefore have to be concerned with a sequence. First come demands formulated by members. Demands are then filtered through an organization. The formulation of a program of action in and by the organization follows. The immediate results of the program take the form of outputs: loans made, human rights violations inspected, desertification projects launched, or a peacekeeping force deployed. Outputs lead to the longer-range consequences of these steps, experienced as satisfaction or dissatisfaction on the part of the members. The core stages are (1) demands, (2) organizational agenda formation, (3) organizational program, (4) organizational output, and (5) experience with the results of the output, or outcome (Figure 1).

Strictly speaking, only the second and third steps in the sequence

Figure 1. The core stages of organizational action

take place in the organization. But obviously it is not possible to conceptualize changes of organizational form unless the consequences of organizational action or inaction as experienced by the members are made part of the analysis: the nature of the feedback from dissatisfaction with outcome to the formulation of a new set of demands is a crucial issue.[3]

My argument throughout this study will be based on how organizations process dissatisfaction; I will not address situations in which all member states are satisfied with outcomes. My reason for this choice is as follows. Organizations entrusted with a certain mission may certainly discharge their tasks in such a way that everybody is generally satisfied. Although this happy state of affairs is extremely rare in the lives of international organizations, very likely the Universal Postal Union and the World Meteorological Organization are entities whose work engenders minimal dissatisfaction. Therefore, they are not under pressure to change their ways—to adapt or to learn. Since my task is to inquire into processes of adaptation and learning (and the absence of dissatisfaction means that the stimulus to adapt or learn is lacking), the experience of such successful organizations is uninteresting to me.

So is the feedback from output to programming because it captures the administrative experiences of the organization's staff when it monitors its own work. If learning takes place at all, it must occur as a result of these feedback processes. Therefore, although our concern is with the shape of the organization as such, we cannot explain changes in shape without paying attention to every step in the sequence. Still, our concern is not with the moral quality of the outcomes. Their character is irrelevant to the exploration. What matters is whether member states, not the observers, are satisfied or unhappy with the outcomes. A final step in the sequence might be an evaluation (moral or not) of whether the international system as a whole, or some regime within it, also changed as a result of the preceding activity. Such an evaluation, however, is the province of the observer passing judgment on history; it is not my concern at this time. True to my commitment to the logical priority of knowledge over interest and power, I begin the exploration of the consequences of dissatisfaction with organizational performance with a discussion of consensual knowledge.Consensual Knowledge

Our concern is this: How does knowledge about nature and society make the trip from lecture halls, think tanks, libraries, and documents to the minds of political actors? How does knowledge, by its nature debatable and debated, become sufficiently accepted to enter the decision-making process? In order to give an account of this process, it is not necessary that we also explain how the relevant information and theories came into existence. We need not and do not deny that many terms and ideas that enter the process remain contentious and contested. Nor do we deny that the political interests experienced by actors are one determinant of which kind of knowledge will be preferred as a basis for decision. I make no claim that consensual knowledge is absolutely different from political ideology; on the contrary,

the line between the two is often barely visible. Some will say that consensual knowledge is merely science-derived transideological and transcultural ideology. I would contest such a claim with only a mild amendment, not challenge it fundamentally, and yet make a case that political choice infused with consensual knowledge is different from, and more pervasive than, choice informed exclusively by immediate calculations of material interest or by the availability of superior power.

By consensual knowledge I mean generally accepted understandings about cause-and-effect linkages about any set of phenomena considered important by society, provided only that the finality of the accepted chain of causation is subject to continuous testing and examination through adversary procedures. Cause-effect chains are derived from information, scientific and nonscientific, available about a given subject and considered authoritative by the interested parties—though the authoritativeness is always temporary. Consensual knowledge is socially constructed and therefore inseparable from the vagaries of human communication. It is not true or perfect or complete knowledge.

We lack a totally consensual criterion for determining truth, perfection, and completeness. It may even be true that what is claimed as consensual knowledge by a bureaucracy is known to be flawed. Yet even this guilty knowledge may be presented to the public as valid merely to protect the mission and the integrity of the organization. In so doing, the nonknowledge interests of the parties concerned are also being protected. Knowledge is not in principle opposed to interest; it is, in the extreme case, the handmaiden of interest.

Consensual knowledge may originate as an ideology. It differs from ideologies only in that it is constantly challenged from within and without and must justify itself by submitting its claims to truth tests considered generally acceptable. Unless such testing takes place, it is impossible to speak of any kind of error correction because the criteria for determining acceptable and undesired outcomes would differ according to the actor concerned. Consensual knowledge differs from ideology-derived interests because it must constantly prove itself against rival formulas claiming to solve problems better. The acceptability, the very quality, of consensus that makes the kind of knowledge of concern to us different from other claims "to know" is the fact that consensus must survive the process of social selection by demonstrating its ability to excel in solving problems.

I hold that such a process describes generally how governments and public organizations have learned to deal with most of the problems their constituents have imposed on them in the twentieth century, with the exception of changed behavior owing entirely to the success of a political revolution, which simply gets rid of competing notions of cause and effect. Our conceptions of what constitutes a problem to be solved by way of public policy have been irretrievably infected by the results of scientific knowledge about nature and society that have gained widespread acceptance.

In what ways can scientific knowledge become a shaper of political decisions? The different ways coexist in time and in space; far from being mutually exclusive, they illustrate four different routes through which scientific information can become politically relevant, even though such information is socially constructed and therefore loses whatever claim to autonomous truth it may have been able to defend.

We can think of knowledge as social epistemology, as a shaper of world views and of notions of causation whereby the intellectual commitments of the seventeenth-century scientists and mathematicians penetrated the way political economists and their disciples in governments began to see the world. That process still continues, even though the informing metaphors today come from cybernetics rather than from mechanics. Science plays a major role in giving us the concepts we use in defining and seeking to solve problems, even though the substantive character of the problem and its human dimension usually are not really elucidated by the scientific metaphor.

Scientific models show up more directly in those fields of public policy in which scientific participation is continuous alongside the work of nonscientific decision makers, such as public health, environmental protection, transportation, telecommunications, and defense production. Here the models used by scientists seriously guide the way problems are defined and solutions devised; economic, political, and legal information that constrains the use of scientific models at the margin, however, also enters the process. Models of this type tend to have universal appeal because decision makers are able to subscribe to many (but not all) of them, irrespective of cultural, religious, and ideological differences. The acceptability of such models does not depend on their being advocated by a hegemonic group or class or nation.

Still other knowledge-infused modes of choice, however, are dependent on extrascientific factors. Theories of macroeconomics, of psychology and criminology, of education, and of social reform can be heavily informed by the results of scientific thinking and research. Nevertheless, the scope of theories is constrained by the fact that a dominant social group, nation, or profession advocates and uses the knowledge in question. Without such "hegemony" it is doubtful that the persuasiveness of the theory would be sufficient to allow us to call it consensual knowledge. Hegemony-aided models of knowledge nevertheless remain subject to the normal truth test.

At a still lower level of abstraction we can identify operational forms of organizing information that result in consensual cause-effect chains, even though this is done without recourse to overarching theory and is heavily influenced by immediate political interests. Newly discovered facts and newly invented models of organizing facts can certainly stimulate the evolution of such operational models. One example is given by the conjunction of information about nuclear energy technology, demand for energy in the context of industrial development, and nuclear proliferation as a military threat. This atheoretical conjunction served to define "the problem" of nuclear proliferation. The field of economic development offers similar examples. Operational models would not exist at all if the main parties did not entertain specific nonscientific objectives. Without political values and interests there would be no incentive to draw on scientific knowledge at all.

Consensual knowledge, then, can be made politically relevant by way of several paths, all available simultaneously in time and space; it is socially constructed and not given by nature; and it is often dependent on political factors for becoming truly consensual. That admitted, we must ask how new cause-effect chains, taking the place of chains accepted at an earlier time but found wanting, can achieve acceptance.

Learning

By "learning" I mean the process by which consensual knowledge is used to specify causal relationships in new ways so that the result affects the content of public policy. Learning in and by an international

organization implies that the organization's members are induced to question earlier beliefs about the appropriateness of ends of action and to think about the selection of new ones, to "revalue" themselves. As this happens, international institutions are being used to cope with problems never before experienced.[4]

I owe this definition of learning to a personal communication from Robert Keohane, who tried valiantly and (I hope) successfully to improve on my earlier definitional attempts. I stress that this definition is intended to be different from the earlier one I offered in chapter 2 of Beyond the Nation-State (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1964).

And as the members of the organization go through the learning process, it is likely that they will arrive at a common understanding of what causes the particular problems of concern. A common understanding of causes is likely to trigger a shared understanding of solutions, and the new chain implies a set of larger meanings about life and nature not previously held in common by the participating members. Put succinctly, learning implies the sharing of larger meanings among those who learn.Learning may involve the elaboration of new cause-effect chains more (or less) elaborate than the ones being questioned and replaced. The resulting conceptualization of the world may be more (or less) holistic than the earlier one. It may imply progress or regress, depending on the normative commitment of the observer or the preferred reading of history. At the moment, the definition of learning I offer is intended to favor no epistemological or ideological preference; I intend to cover any organizational behavior involving self-reflection leading to change. In the final chapter, however, the idea of direction and of progress is reintroduced as I emphasize my own normative stance.

Questioning an established cause-effect schema involves the disaggregation of a problem as it had been initially conceived. The problem first has to be "taken apart"; its parts have to be identified and sorted into patterns different from the ones that had been featured in an earlier round. That done, the problem has to be reaggregated into a different nested set, either more complex and comprehensive than the original one or less so. I develop an example from Karl Deutsch's work to illustrate the process as it involves shifts to greater complexity.[5]

Karl W. Deutsch, The Nerves of Government (New York: Free Press, 1963), chaps. 5, 6. The idea of disaggregating and then reaggregating the parts of a schema underlying public policy is described in Paul Diesing, Reason in Society (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962). A similar idea underlies the empirical investigations of Philip Tetlock in his cognitive studies of foreign policy decision making. See "Integrative Complexity in American and Soviet Foreign Policy Rhetoric," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49, no. 6 (1985). My conception of the socially constructed basis of the knowledge that enters policy making comes from Burkhart Holzner and John Marx, Knowledge Application (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1979), chap. 4.

We have here a normative element. By what right can one describe learning as tending toward the recognition of a "higher" order of purpose? I imply that a higher order of purpose is also a better purpose, that seeing the world as a more complexly, more tightly coupled system is a more appropriate approach to problem solving in this context. My main justification for this stance comes from my reading of modern history and especially from the growing importance of systemic information in the design of public policy, a justification reserved for chapter 9.

The example from Deutsch involves ascending orders of purposes, beginning with the mechanics of warfare and ending with social transformation. The story begins with an automated antimissile battery programmed to defend the country. The purpose is to achieve immediate satisfaction. In order to make sure that this system works properly, however, a second purpose must be superimposed on it—namely,

self-preservation. In order to make the battery work so as to avoid an unwanted war, it may be necessary to subject it to a higher intelligence, a model of crisis escalation that would tell not only the battery but also the entire country about the steps necessary to avoid accidental war. If this turns out to be too difficult a task, however, a third purpose must be superimposed on self-preservation—namely, the preservation of humankind. Our crisis prevention model would then be subordinated to a more general model aimed at preventing war altogether. But then suppose it is realized that the prevention of all war is not possible without having a more comprehensive understanding of human conflict and cooperation in general. Once that is realized, a fourth purpose is superimposed on the previous three—namely, the preservation of a process. The name of the game now becomes learning all one can about all kinds of links and connections among trends and events that may illuminate human conflict. Learning, in Deutsch's sense, then means the ability to shift from lower to higher orders of purposes. Organizations that subject their causal beliefs to such a process are perpetual learners.

My definition of learning differs from one often encountered in the literature on international organizations. Functionalists make two interconnected arguments about learning.[6]

See Robert E. Riggs and I. Jostein Mykletun, Beyond Functionalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1979), 166-76, for a full statement of the relationship between functionalist thought and learning.

One could claim that any change in behavior due to one's experience in international organizations constitutes learning, but functionalists reformulate the argument to claim that learning consists of changing one's attitude and behavior as a result of association with a successful functional (i.e., "nonpolitical") organization. Evidence of such learning is the demand that additional functional organizations, designed on the model of the first one, be set up, and that those who participated in the work of these organizations developed positive attitudes toward them.[7]Riggs and Mykletun point out that the "demonstration effect" aspect of learning can be substantiated from historical experience, but that the "positive affect" aspect of learning must be qualified so heavily on the basis of extant empirical studies as to be descriptively almost worthless. Nevertheless, and despite the shortcomings of the functionalist explanations they present, not all aspects of the functionalist argument are shown to be wrong. See ibid., 177ff.

These formulations are less than fully helpful because they do not tell us what has to be learned or how cognitive processes have to be reorganized. Most important, they fail to spell out the institutional and political blocks to the development of positive attitudes; nor do they even ask which forms of organizational design are likely to overcome such blockages. To argue that form follows function and that function follows participation and positive experience flies in the face of experience with disappointment and unintended consequences.Nor do organizations learn as do individuals, even though they are made up of individuals. Institutional routines interfere with learning: lessons learned by one bureaucrat do not necessarily become the collective wisdom of his or her unit. Lessons learned are informed by the interests professed by the learner. We do not assume that the interests will change only because a given routine used in their implementation has failed. Such approaches equate learning with error correction by individuals. But the observer then has to specify what the "correct" perception ought to be, and the "correct" perception inevitably turns out to be the one preferred by the observer.[8]

One author defines individual learning as "changes in intelligence and effectiveness" and the operationalization of the growth of intelligence as "(1) growth of realism, recognizing the different elements and processes actually operating in the world; (2) growth of intellectual integration in which these different elements and processes are integrated with one another in thought; (3) growth of reflective perspective about the conduct of the first two processes, the conception of the problem, and the results which the decision maker desires to achieve" (Lloyd S. Etheridge, Can Governments Learn? [New York: Pergamon, 1985], 66, emphasis in original).

Etheridge's book and his "Government Learning" (in Handbook of Political Behavior, ed. Samuel Long [New York: Plenum, 1981]) are among the first systematic efforts to conceptualize learning by public organizations, even if the lessons learned turn out to be the things the author preferred. The therapeutic component of the theory lies in the emphasis on internal communication, openness, heterodoxy, competition among ideas, personal creativeness, and its rewards. Etheridge explicitly equates government learning with lessons learned by single policy makers. The character of the routines suggested is thought to generalize learning to other decision makers. Abraham Maslow rides high in this approach.

If intelligence is not a useful guidepost for understanding organizational learning, neither is effectiveness. Any judgment regarding the effectiveness of one's performance pertains to technical rationality, not value rationality. Effectiveness is useful in explaining how adaptation occurs, but not how learning as I defined it takes place. Technical criteria for evaluating the performance of international organizations, although no doubt essential for monitoring staff performance, do not speak to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of the clients, who may value such abstract aims as equity, quality of life, or the enjoyment of individual rights even if the organization falls short of mundane, technically effective performance.[9]

Argyris and Schon recognize as much in their distinction between "single loop" learning (which fits our notion of adaptive behavior) and "double loop" learning (Organizational Learning, chaps. 1, 2). Double-loop learning corresponds to my notion of organizational learning. Argyris and Schon differ from my approach in their emphasis on therapeutic techniques to induce double-loop learning. They identify this kind of innovative behavior with the perfection of internal communications and the relaxation of internal hierarchy—with participation. It requires an openness to criticism and the willingness to forgo stability in favor of unending change. The suggestions for designs that facilitate double-loop learning do not deal with the kinds of demands clients make, or with the outcomes of prior organizational action that have engendered disappointment with respect to values that were to be served.

If notions of affect, imitation, intelligence, effectiveness, and therapy are to be banished from our discussion of learning, who is the redefiner of cause-effect understandings? Who engages in a process that can lead to large shared meanings? Who is supposed to learn?

"An international organization learns" is a shorthand way to say that the actors representing states and members of the secretariat, working together in the organization in the search for solutions to problems on the agenda, have agreed on a new way of conceptualizing the problem. That is, it is not individuals, entire governments, blocs of governments, or entire organizations that learn; it is clusters of bureaucratic units within governments and organizations. That, of course, suggests that there can be varying rates of learning and quite different incentives to learn, depending on context, professional ethos, type of problem, type of region. The unit that learns is a particular kind of collective actor defined by its place in the organization, in world politics, in a professional and knowledge culture.

What of the presumed beneficiaries of the organization's output? Don't they matter? Organizations are supposed to contribute to the happiness and welfare of peasants, refugees, sufferers from communicable diseases, victims of malnourishment, slumdwellers, industrial workers seeking to form trade unions, and users of telecommunications networks. The demands, satisfaction, and dissatisfaction of these people do not matter in my identification of the learner because we cannot be sure whether and to what extent the demands of the potential beneficiaries actually influence the choices made by bureaucratic units. On the whole, the role of the grassroots is very remote in shaping decisions of governments and of international organizations in Third World settings. We can be certain that the disappointment of decision makers influences choice; we can be certain only of the suffering of the presumed beneficiaries, not of their power to be heard.

The stimuli that lead to learning come mostly from the external environment in which the organization is placed, not from inside the organization. As will be shown below, international organizations are hyperdependent on their environments; they can hardly be distinguished from their environments. Therefore, the main impulses that may lead to learning or adaptation are far more likely to come from the environment than from such endogenous concerns as the coordination of units, sources of revenue, staff-line relations, or internal monitoring. My investigation is therefore biased in favor of exogenous sources of change. That admitted, it still makes good sense to worry about improved organizational design because the forces emanating from the environment are far from uniform, and they push in quite different directions. It still makes sense to worry about making internal design more hospitable than it now is to learning impulses.

Can we say something about the environmental conditions most likely to lead to learning? Are there plausible predictors of learning? None is obvious; several are possible. I review them without settling the issue: the desirability of finding new cause-effect chains, the possibility of finding them, and the urgency for finding them.

Desirability refers to the incentives motivating the bureaucratic units to engage in some soul-searching. We hypothesize that actors' career goals and political opportunities to prosper are heavily identified with pleasing a certain constituency, with helping that constituency

to solve its problems. Issues that can be approached with the proper conjunction of incentives on the part of decision makers are more likely to be dealt with than issues that do not offer the same opportunities. From the vantage point of desirability, it makes more sense to reexamine one's ends and values with respect, for example, to fighting epidemics than to mount campaigns in favor of human rights.

The existence of political incentives may not be enough to trigger learning. The possibility of redefining ends along new causal chains must also exist. This possibility, of course, is a function of the state of scientific knowledge, the degree of consensus it enjoys, and the availability of epistemic communities for spreading the word, a point to which we return below. The possibility of learning refers to the availability of new means that entitle actors to consider new ends not previously accessible to them.

One would think that the urgency of the problem involved has something to do with the rate of learning. Is there a crisis that calls out for immediate action, such as a famine, the imminent bankruptcy of a large country and its creditors, or an AIDS epidemic? If the requisite knowledge exists (or can rapidly be found) and if political incentives are aligned with crisis management, we would expect rapid learning to occur. We would also expect that a crisis combined with the special salience of certain issues would increase the urgency. Is health the most salient, or is malnutrition? Is either issue more salient than economic development or debt relief? Are programs and problems involving money for economic development the most salient? It is impossible to say without comparing the learning patterns of the organizations that correspond to these issues. At this point I speculate that learning is triggered in situations showing high desirability, reasonable possibility, and the conjunction of high issue salience and a crisis.

International Organizations as Satisficers

Learners are bureaucratic entities. These are normally studied and described in the idiom of organization theory. But not all aspects of organization theory are germane to our quest. A number of assumptions commonly made by all organization theorists, who derive their ideas from studying business firms and public bureaucracies, must be modified.

One is the notion of organizations seeking autonomy from and control over their environment; another is about the dominance of technically rational decision making.

Environment Dominates Organizations

Standard organization theory assumes that the entity under study seeks a maximum of control over its environment. Organizations are envisaged as systems seeking to get the better over external elements and actors that might reduce the entity's autonomy. Boundary maintenance is therefore crucial, whether the environment is envisaged as being made up of customers, suppliers, competitors, political clients, or other bureaucracies. Although it is understood that the organization must satisfy those environmental forces on which the organization depends, maximum attainable control over them is seen as the best way to achieve autonomy. Autonomy, in turn, is valued because it guarantees the survival of the organization in a competitive setting.

The core concept in the struggle for survival is the idea of adaptation. Adaptation implies that the organization must consistently review its operations in order to make sure that boundaries are maintained in such a fashion as to favor survival. Review implies that past errors in decision making have been identified and corrected. To adapt, then, means to so alter operations in the face of a changing environment as to be more certain of surviving and prospering. If the prevalence of competition among organizations is the challenge to survival, then principles of wise management are the techniques to assure that natural selection favors you rather than your competitor. Successful adaptation implies using the techniques of management and design found to be theoretically and practically appropriate.

Wise administration implies rational decision making. The kind of decision theorists have in mind here is the type Max Weber called "technically rational"—an "efficiency-seeking" decision. The overall purpose of the decision is to improve whatever the organization's main mission is: to make a profit in producing refrigerators, to provide software services, or to grow soybeans. In the case of public organizations the mission may be helping the handicapped, improving agricultural productivity in Mali, or perfecting a defense against missile

attack. The purpose is not questioned; the means for achieving it are constantly reviewed. It bears repeating that the exercise of technical rationality presumes an agreed, known, and stable ordering of preferences among the decision makers.