Preferred Citation: Rousseau, G.S., editor The Languages of Psyche: Mind and Body in Enlightenment Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft638nb3db/

| The Languages of PsycheMind and Body in Enlightenment Thought |

For Norman Thrower,

Director of the Clark Library 1981-1987,

who can read this book,

and

the late Donald G. O'Malley,

who cannot.

Preferred Citation: Rousseau, G.S., editor The Languages of Psyche: Mind and Body in Enlightenment Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft638nb3db/

For Norman Thrower,

Director of the Clark Library 1981-1987,

who can read this book,

and

the late Donald G. O'Malley,

who cannot.

Preface

When Norman Thrower, then the Director of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA, invited me to serve as the Clark Library Professor for 1985-86, I immediately realized that the subject to be privileged should be the mind/body relation viewed within broad cultural and scientific contexts, and against the complexities of Enlightenment theory and practice. Here was a topic that had not been worked over by specialists, or generalists, in the field; a topic, moreover, of terrific contemporary impact, as men and women from diverse walks of life wonder how their minds and bodies—surely parts of one, indivisible, holistic unit—ever came to be separated.

My own research interests in the relations of science and medicine to the imaginative art forms generated during the Enlightenment were so interdisciplinary that I began to envision ways in which these subjects could be transformed into a useful annual series. The mind/body relation inevitably straddles the interstices of the sciences and the humanities: that no-man's-land lying between Scylla and Charybdis—territories still deemed worthy of special study to us today and which we have come to take for granted, yet a relation that was coming into its own during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

More locally in southern California, medicine had been omitted from the Clark Library's programs from the inception of the Clark Professor Series, yet not by design. The late Donald G. O'Malley, a distinguished professor of the history of medicine at UCLA and the author of an important biography of Vesalius, the pioneering Renaissance anatomist, had died in 1969, while in the midst of planning just such a series at the

Clark Library. Dr. O'Malley would have executed his task with the characteristic dedication and thoroughness for which he was known during his lifetime. Had he lived long enough to prepare a volume similar to this one, I know it would have made a significant contribution to the frontiers of knowledge, and although he cannot read this book, I feel certain that he would have encouraged its conception and execution in every possible way. To both these able scholar-administrators—Norman Thrower and D. C. O'Malley—this volume is dedicated.

Yet ultimately the measure of this book's success will be determined by its diverse readership and by the nine contributors, all of whom were willing to take time from their own work and academic-administrative obligations at their home institutions to pursue the common theme of this volume: mind and body during the European Enlightenment. The team itself was vigilantly selected with regard to disciplinary affinity, national origin, geographical location, and even generational point of view, gender, and methodology: all these to provide balance and variety to an area—the complex relations of mind and body in an epoch of intense intellectual ferment—in which new paths prove hard to find. If, then, a common theoretical underpinning is perceived to be missing from the ten essays, or if it is adjudged that here less attention is paid to methodology than some readers would like, this derives, in part, as a direct consequence of the death of the first participant—the late Michel Foucault—and as the result of the liberty given to all the participants ensuring that they could follow their own researches.

Foucault had agreed to provide a theoretical framework of just the type for which he was deservedly renowned—specifically, to illuminate the semiotics and signposts of mind and body during the Enlightenment. Had he lived to participate in this volume, he would no doubt have performed his task with characteristic brilliance and bravura. I was therefore relieved when Roy Porter consented to replace him. Porter had already agreed to participate in the series, but not in the opening slot, and I continue to remain in his debt for assisting me at a time when assistance was direly needed. As if this kindness were insufficient, Porter also collaborated with me in composing the opening essay which, we hope, will tie together the threads of this complex subject.

Chapters 2 through 10 were originally delivered as public lectures in Los Angeles from October 1985 to June 1986, each describing an aspect of the representation of mind and body during the Enlightenment. The introduction was not delivered in the series, but aims to contextualize the topic and introduce the various approaches—not by listing or comparing them in any systematic way but by locating them within a con-

tinuum of discourses and critiques suggestive of the immense complexity of the problem. The introduction—"Toward a Natural History of Mind and Body"—also aims to describe the tangled web and vast historiography of the subject.

Even so, our collective approach in the volume remains eclectic, especially with reference to national cultures, and none of the contributors seeks to provide an exhaustive, let alone complete, view of his or her topic in any sense in which completeness can be construed. The approaches, coming from the domains of social history and the history of religions, the history of science and the history of medicine, literary criticism and literary theory, and—of course—philosophy, themselves serve as diversified commentaries on the endurance of the mind/body problem in our time and its resonance over three centuries. That mind and body should continue to serve as vital metaphors for these disciplines—in literary criticism, for example—attests, as well, to the resonance of the concept into our own era. Still, nowhere do the authors (again individually or collectively) suggest that the mind/body split is in any scientific or objective sense valid, or endorse it as a philosophically defensible doctrine in any of its dualistic, or neodualistic, versions. Our intention has not been to take sides and decide these matters once and for all, but to trace origins and chart continuities—to tease out the metaphors and tropes that continue to haunt late-twentieth-century civilized discourse. Indeed, the problematization of the notion of validity for the mind/body relation is precisely what we have identified as our subject. And we consider it our collective task to assess the status of the split in Europe during the period of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (in this book commonly referred to for convenience as the Enlightenment).

Always, our task was eased by the Clark's Librarian, Dr. Thomas Wright, and his deputy, Dr. John Bidwell, and was also facilitated by the staff of the institution, who accord their guests so many acts of kindness. The volume, more specifically its editor, incurred a number of debts during the annual series that must be acknowledged, even if briefly. Susan Green assisted us even before the series opened by meticulous supervision of every aspect of its daily operations; and Carol Briggs, now resident in London but then very much a member of the Clark's staff, proved most useful on those leisurely Friday afternoons when the scholars gathered with the public, delivered their talks, and engaged in lively and sometimes heated debate about these controversial subjects. Dr. Franklin D. Murphy, the former Chancellor of UCLA, supported the series on mind and body with a grant given by the Ahmanson Foundation. Sandra Guideman transformed the long and complex initial man-

uscript into the final manuscript, which Nicholas Goodhue copyedited for the press. My chair at UCLA, Professor Daniel A. Calder, released me from various duties in the Department of English so that I could focus my attention in 1986-87 on the book, during the year after the series was delivered. Dr. Gerald Kissler, our Vice-Provost at UCLA, supported the series in a number of ways during the actual year, and Provost Raymond Orbach provided us with funding that ensured the publication of this volume. Professor Herbert Morris, our Dean of Humanities in the College of Letters and Science at UCLA, aided us under two hats: in his administrative capacity and, as crucially, as a philosopher who came to some of our meetings and asked hard questions. Most tangibly, Scott Mahler, our editor at the University of California Press, performed a multiplicity of kindnesses and services too numerous to be itemized here.

To all these friends of The Languages of Psyche, and to the others whose names do not appear because the Preface would have swelled to Brobdingnagian proportions if the full roll call had been produced, we express our deep gratitude and thanks.

G. S. Rousseau

University of California, Los Angeles

Contributors

Carol Houlihan Flynn is Professor of English at Tufts University.

Philippa Foot, regarded by her colleagues as one of the most influential moral philosophers of her generation, holds the Gloria and Paul Griffin Chair in Philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles, and is Senior Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford University, Oxford.

Robert G. Frank, Jr. is Associate Professor of Anatomy and History at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Antonie M. Luyendijk-Elshout is Emeritus Professor of the History of Medicine at the University of Leiden, Holland, and a Trustee of the National Boerhaave Museum.

David B. Morris, formerly Professor of English at the University of Iowa, is a free-lance writer who lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Richard H. Popkin is Adjunct Professor of History and Philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the doyen of historians of skepticism. He served as Clark Library Professor at UCLA in 1981-82.

Roy Porter is Lecturer in the Social History of Medicine at the Well-come Institute for the History of Medicine, London, and served as Clark Library Professor at UCLA in 1988-89.

G. S. Rousseau served as Clark Library Professor at UCLA in 1985-86, where he is Professor of English and Eighteenth-Century Studies.

Simon Schaffer is Lecturer in the History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge University, and a Fellow of Darwin College.

Dora B. Weiner is Professor of Medical Humanities at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Epigraphs

I know that a Triangle is not a Square, and that Body is not Mind, as the Child knows that Nurse that feeds it is neither the Cat it plays with, nor the Blackmoor it is afraid of, and the Child and I come by our Knowledge after the same Manner.

—Mary Astell, The Christian Religion, As Profess'd by a Daughter of the Church of England (London, 1705), 95.

For mark the Order of things, according to their [the metaphysicians'] account of them. First comes that huge Body, the sensible World. Then this and its Attributes beget sensible ideas. Then out of sensible Ideas, by a kind of lopping and pruning, are made ideas intelligible, whether specific or general. Thus, should they admit that MIND was coeval with BODY, yet till BODY gave its Ideas, and awakened its dormant Powers, it could at best have been nothing more, than a sort of dead Capacity: for INNATE IDEAS it could not possibly have any.

—James Harris, Hermes; or, A Philosophical Inquiry concerning Language (London, 1756), 392-393.

I find my spirits and my health affect each other reciprocally—that is to say, everything that discomposes my mind, produces a correspondent disorder in my body; and my bodily complaints are remarkably mitigated by those considerations that dissipate the clouds of mental chagrin.

—Tobias Smollett, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (London, 1771), Mathew Bramble to Doctor Lewis, June 26.

Descartes appeared to have fallen rather out of love with geometry and physics, and liked to imagine (for this apostle of reason was singularly prone to imagining) the workings of the living organism. Indeed, in spite of his efforts to separate Psyche from the body and from extension, he went to great lengths to find her a cerebral habitation and to demonstrate that this location was indispensable for the purpose of feeling.

—Paul Valéry, Masters and Friends (Princeton, 1968), 64-65; originally published in French in 1918.

How is it, that the visual picture proceeds—if that is the right word—from an electrical disturbance in the brain?

—Sir Charles Sherrington, Man on His Nature (Cambridge, 1946), 125.

The compulsive urge to cruelty and destruction springs from the organic displacement of the relationship between the mind and body.

—Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (New York, 1972), 233; originally published in German in 1944.

Curiously, for a society that believes in a mind superior to the body, we extol behavior in which the mind is said to be absorbed in the body, in contrast to a sexual act in which the mind may be detached from the body.... The mind/body dichotomy itself can be seen as an extension of the body, expressing symbolically the separate functions of the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

—John Blacking, The Anthropology of the Body (London and New York, 1977), 20.

At one time many people adhered to what the philosopher Gilbert Ryle called the 'official view' of the relationship between mind and body (or brain), which can be traced back at least to Descartes. According to this view, mind (or soul) is a type of substance, a special type of ephemeral, intangible substance, different from, but coupled to, the very tangible sort of stuff of which our bodies are made. Mind, then, is a thing which can have states—mental states—that can be altered (by receiving sense data) as a result of its coupling to the brain. But this is not all. The link which couples brain and mind works both ways, enabling us to impress our will upon our brains, hence bodies.

Today, however, these dualistic ideas have fallen out of favor with many scientists, who prefer to regard the brain as a highly complex, but otherwise unmysterious electrochemical machine, subject to the laws of physics in the same way as any other machine.

—P. C. W. Davies et al., The Ghost in the Atom: A Discussion of the Mysteries of Quantum Physics (Cambridge, 1986), 32.

Progress lies in the direction of disengagement from the social and medical sciences, and through greater cooperation between historians and literary scholars. The old boundaries between fact and fiction, the real and the imagined, subject and object have been breached. Now comes the task of reconnecting mind and body.

—John R. Gillis, Annals of Scholarship 5, 4 (1988): 523.

There is a straight ladder from the atom to the grain of sand, and the only real mystery in physics is the missing rung. Below it, particle physics; above it, classical physics; but in between, metaphysics. All the mystery in life turns out to be this same mystery, the join between things which are distinct and yet continuous, body and mind.

—Tom Stoppard, Hapgood (London, 1988), 49-50.

Part One

Theories of Mind and Body

One

Introduction:

Toward a Natural History of Mind and Body

G. S. Rousseau and Roy Porter

I

The mind/body problem has long taxed Western thought. This book is not, however, another contribution to the philosophical argument about mind/body relations per se.[1] Rather, the common endeavor uniting these essays amounts to something different, the desire to explore the problem of the mind/body problem. In their different ways, all the authors investigate why it has been the case (and still is) that conceptualizing consciousness, the human body, and the interactions between the two has proved so confusing, contentious, and inconclusive—or, as we might put it, has acted as the grit in the oyster that has produced pearls of thought. Furthermore, the volume as a whole has the wider purpose of taking that mind/body dichotomy which has been such a familiar feature of the great philosophies and locating it within its wider contexts—contexts of rhetoric, fiction, and ideology, of imagination and symbolism, science and religion, contexts of groups and gender, power and politics. To

[1] Rigorous study of the mind/body relationship construed in the philosophical sense begins as a subset of the philosophy of mind in the nineteenth century, and a case can be made that there are traces of it evident in eighteenth-century rational thought. By the time the journal Mind: A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy was launched in England in 1876, the mind/body relationship was a widely discussed philosophical topic and a valid field of serious inquiry, as is evident, for example, in books written by diverse types of authors. See, for example, the philosopher George Moore's The Use of the Body in Relation to the Mind (London: Longman, 1847), Benjamin Collins Brodie's Mind and Matter (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1857), and the famous British psychiatrist Henry Maudsley's medico-philosophical study of Body and Mind (London, 1873).

By the turn of the twentieth century, discussions of mind/body continued to flourish in the major European and American schools of philosophy, as can be seen in the tradition from Wittgenstein to Gilbert Ryle and A. J. Ayer, and in such works as the well-known philosopher C. D. Broad's The Mind and Its Place in Nature (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1925). More recently, see R. W. Rieber, ed., Body and Mind: Past, Present and Future (New York: Academic Press, 1980); Nell Bruce Lubow, The Mind-Body Identity Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974); Michael E. Levin, Metaphysics and the Mind-Body Problem (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); and Norman Malcolm, Problems of Mind: Descartes to Wittgenstein (New York: Harper and Row, 1971)—authors writing on the relationship from different perspectives and for different diachronic periods. The literature is vast and continues to produce scholarship, as can be surmised from the entry on "Mind and Body" in the recently published Oxford Companion to the Mind, ed. R. L. Gregory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 204.

speak of the mind/body problem as if it were a timeless abstraction, a topos for unlimited discussion by countless symposia down the ages, would be to perpetuate mystifications. It must itself be problematized—theorized—in relation to history, language, and culture. And here, the first thing to notice—a bizarre fact—is the paucity of synthetic historical writing upon this profound issue.[2]

[2] The historiography of the mind/body relationship extends, of course, as far back as the Greeks and demonstrates a long tradition of speculation, so abundant that it would be foolish to attempt to provide any sense of its breadth in the space of a note. But we want to comment on the main curves of the heritage of mind and body, especially by noticing the supremacy of mind over body throughout the Christian tradition, and the reinforcement of this hierarchy in the aftermath of Cartesian dualism. Both mind and body received a great deal of attention in the Enlightenment, and it is one of the purposes of this book to annotate this relationship in a variety of discourses, more fully than the matter has been studied before. There is also a large literature, scientific and mystical, secular and religious, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, that treats of the mind's control over the body or the converse: see, for instance, the Paracelsian physician F. M. van Helmont: The Spirit of Diseases; or, Diseases from the Spirit...wherein is shewed how much the Mind Influenceth the Body in Causing and Curing of Diseases (London, 1694). Other works attempted to demarcate the boundaries of mind and body, such as John Petvin's Letters concerning Mind (London: J. and J. Rivington, 1750); John Richardson's (of Newtent) Thoughts upon Thinking; or, A new theory of the human mind: wherein a physical rationale of the formation of our ideas, the passions, dreaming and every faculty of the soul is attempted upon principles entirely new (London: J. Dodsley, 1755); and John Rotherham's On the Distinction between the Soul and the Body (London: J. Robson, [1760]), a philosophical treatise aiming to differentiate the realm of mind from that of soul. Still other discourses, often medical dissertations written with an eye on Hobbes's De Corpore (1655), actually aimed to anatomize the soul as distinct from the brain in strictly mechanical terms; see, for example, Johann Ambrosius Hillig, Anatomie der Seelen (Leipzig, 1737). In all these diverse discourses, the dualism of mind and body was so firmly ingrained by the mid eighteenth century that compendiums such as the following continued to be issued: Anonymous, A View of Human Nature; or, Select Histories, Giving an account of persons who have been most eminently distinguish'd by their virtues or vices, their perfections or defects, either of body or mind...the whole collected from the best authors in various languages ...(London: S. Birt, 1750).

More recently, in the Romantic period, there was realignment of the dualism often in favor of the body, as J. H. Hagstrum has noted in The Romantic Body: Love and Sexuality in Keats, Wordsworth and Blake (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985). In our century, the discussion has proliferated in a number of directions. On the one hand, there is a vast psychoanalytic and psychohistorical literature that we do not specifically engage in this volume but whose tenets can be grasped, if controversially, in Norman O. Brown's Life against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1957), a classic expression of the Freudian viewpoint; and in Leo Bersani's The Freudian Body: Psychoanalysis and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985). On the other, the philosophy of mind within the academic study of philosophy has continued to privilege mind over body. But there is now also a tradition of revaluation that (at least nominally) attempts to view the mind/body relationship neutrally, giving each component allegedly equal treatment no matter which diachronic period is being studied, and still other critiques that view body in relation to society, as, for instance, in A. W. H. Adkins, From the Many to the One: A Study of Personality and Views of Human Nature in the Context of Ancient Greek Society, Values and Beliefs (London: Constable, 1970), and in Bryan Turner's The Body and Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984). Francis Barker's The Tremulous Private Body: Essays on Subjection (New York: Methuen, 1984), represents the reconstruction of the body according to the lines of modern literary theory.

Other, more diverse, studies pursuing literary, artistic, political, and even semiotic relationships include: David Armstrong, Political Anatomy of the Body (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Leonard Barkan, Nature's Work of Art: The Human Body as Image of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975); Body, Mind and Death, readings selected, edited and furnished with an introductory essay by Anthony Flew (New York: Macmillan, 1964); J. D. Bernal, The World, the Flesh and the Devil: An Inquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul (London: Cape, 1970); Robert E. French, The Geometry of Vision and the Mind-Body Problem (New York: P. Lang, 1972); Jonathan Miller, The Body in Question (London: Cape, 1978); Gabriel Josipovici, Writing and the Body (Brighton: Harvester, 1982); for a literary interpretation, see M. S. Kearns, Metaphors of Mind in Fiction and Psychology (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1987). Rebecca Goldstein, the British novelist, has written a novel about the dualism entitled The Mind-Body Problem (London, 1985).

During this decade there has been a proliferation of studies of the body in respect of gender, as in: Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979); idem, No Man's Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988); Susan Rubin Suleiman, ed., The Female Body in Western Culture: Contemporary Perspectives (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985); Catherine Gallagher and Thomas Laqueur, eds., The Making of the Modern Body (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1986); Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984). The full range of studies of the body in our time will become apparent when Dr. Ivan Illich's comprehensive bibliography of "The Body in the Twentieth Century" appears.

If we acknowledge a certain plausibility to Alfred North Whitehead's celebrated dictum that all subsequent philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato, we might be especially disposed to the view that the mind/body

problem is amongst the most ancient and thorny—yet fundamental and inescapable—in the Western intellectual tradition. For the predication of such differences was one of Plato's prime strategies. In attempting to demonstrate against sophists and skeptics that humans could achieve a true understanding of the world, Plato developed rhetorical ploys that postulated dichotomies between (on the one hand) what are deemed merely fleeting appearances or shadows and (on the other) what are to be discovered as eternal, immutable realities. Such binary opposites are respectively construed in terms of the contrast between the merely mundane and the truly immaterial; and these in turn are shown to find their essential expressions on the one side in corporeality and on the other in consciousness. The construction of such a programmatically dualistic ontology provides the framework for epistemology, since for Plato, the only authentic knowledge—not to be confused with subjective "belief" or "opinion"/is that which transcends the senses, those deceptive windows to the world of appearances. But it is equally the basis for a moral theory, as dozens of philosophers have shown: knowing the good is the necessary and sufficient condition for choosing it, and right conduct constitutes the reign of reason over the tumult of blind bodily appetites.

The Homeric writings are innocent of any such clear-cut abstract division between a unitary incorporeal principle called mind or soul, and the body as such. So too the majority of the pre-Socratic philosophers. But "Enter Plato," as Gouldner put it, and the terms were set for philosophy.[3] And, as Whitehead intimated, the formulations of post-Platonic philosophies can be represented as repeatedly ringing the changes upon such foundational propositions. Admittedly, as early as Aristotle, there was dissent from Plato's postulation of Ideas, or ideal forms, as the eternal verities indexed in the empyrean; yet in practice the Aristotelian corpus affirmed the equally comprehensive sovereignty of mind over matter in the natural order of things, which found expression—ethical, sexual, social, and political—in his images of the good man (the gender is significant) and his superior status within the hierarchies of the family, economy, polity, and cosmos. And in their varied ways, most other influential philosophies of antiquity corroborated the elemental Platonic interpretation of the order of existence as organized through hierarchi-

[3] Alvin Gouldner, Enter Plato: Classical Greece and the Origins of Social Theory (New York: Basic Books, 1965) emphasizes how Plato makes a break with earlier thought traditions. A good introduction to Plato's strategies is offered by G. M. A. Grube, Plato's Thought (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980). Popper's attack upon Plato is worth remembering in this context: Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies (London, 1945). See also Bennett Simon, Mind and Madness in Ancient Greece (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1978).

cal dochotomies that dignified the immaterial over the physical, and, specifically, mind over the flesh that was so patently the seedbed of mutability and the harbinger of death. Through its aspirations to "apathy"—and, if necessary, in the final analysis, suicide—Stoicism aimed to reduce the body to its proper insignificance, thereby liberating the mind for its nobler offices. Neoplatonists in the Renaissance and later, with their doctrines of love for higher, celestial beings, likewise envisaged the soul soaring upward, in an affirmation of what we might almost call the incredible lightness of being.

Moreover, the rational expression of the Christian gospel, drawing freely upon Platonic formulas, was to recuperate the radical ontological duality between mind and gross matter in its assertion that "in the beginning was the Word." (Here, of course, are the origins of the logocentrism that proves so problematic to our contemporaries.) Various sects of early Christians, from Gnostics to Manichaeans, took the dualistic disposition to extremes, by mapping the categories of good and evil precisely onto mind and body respectively, and urging modes of living—for example, asceticism or antinomianism—designed to deny the demands of the body in ways yet more drastic than ever the Stoics credited.[4]

II

There is no need in this Introduction to provide a detailed route-map through the history of Western thought, charting the course taken by such dualistic ontologies of mind over matter, mind over body, ever since antiquity gave it its philosophical, and Christianity its theological, expression, and Thomist Scholasticism synthesized the two. Nevertheless, something substantial must be said about the natural history of mind and body. Otherwise, the stunning essays in this volume will appear to be less integrated than they are, and the chapters by Foot and Popkin may appear to fall outside the book's stated scope. In fact, Foot's chapter demonstrates that the accounts of motivation in both Locke and Hume depend upon an antecedent theory of mind and body: as motives belong to the realm of the mind, the emphasis on pleasure and pain in the thought of Locke is not readily understood without taking account of his well-developed mind/body relation. Popkin's claim, in contrast, is

[4] F. Bottomley, Attitudes to the Body in Western Christendom (London: Lepus Books, 1979); Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988).

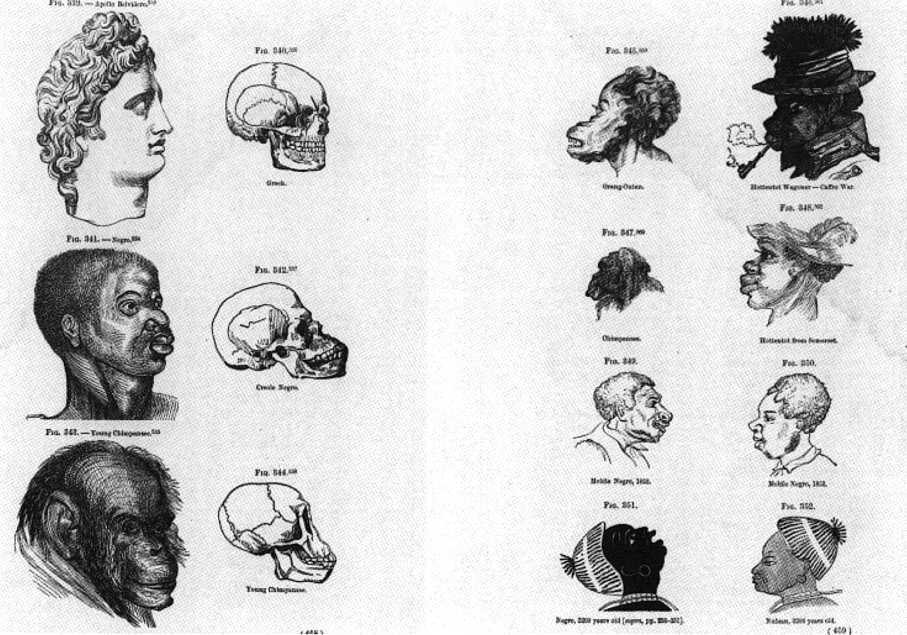

that racism always depends to a certain extent on the anthropological and biological assumptions of its proponents, and although he assumes rather than adumbrates the point, the biology of an era necessarily reflects a substratum of philosophical ideas concerning empiricism and magic, mechanism and vitalism, materialism and immaterialism, reason and unreason—in short, all those constellations that converged into "mind-body" during the Enlightenment. These ideas, sometimes coherent, sometimes not, fed into the ocean of Enlightenment thought we are calling "mind and body," and although The Languages of Psyche does not undertake to compile any proper history or route-map of the conjunction, we (the collective authors) believe that the mind/body relation possesses a rather intricate natural history that must be articulated here if the essays that follow are to be appreciated.

Influential Renaissance teachings on the nature of man and his place in nature—in particular, those of Ficino and Pico—articulated Christian versions of Neoplatonic idealism;[5] Christian Stoicism was soon to have its day. And Descartes's celebrated "proof" of the mind/body polarity—under God, all creation was gross res extensa with the sole exception of the human cogito —confirmed the priority and superiority of mind with a logical éclat unmatched since Anselm, while providing a vindication of dualism both deriving from, and, simultaneously, legitimating, the "new science" of matter in motion governed by the laws of mechanics. Furthermore—and crucially for the future—Descartes contended that it was upon such championship of the autonomy, independence, immateriality, and freedom of res cogitans, the human consciousness, that all other tenets fundamental to the well-being of that thinking subject depended: man's guarantees of the existence and attributes of God, the reality of cosmic order and justice, the regularities and fitnesses of Creation.

Micro- and macrocosmic thinking, ingrained as part of the medieval habit of mind, found itself reinvigorated by the Cartesian dualism. Whether this was owing primarily to religious or secular developments, or again to the challenge given to the "old philosophy" by the "new science," continues to be the subject of fierce controversy among a wide variety of historians on many continents. But the progress of micro-macrocosmic analogies itself is unassailable. For the Malebranchians and Leibnizians, Wolffians and Scottish Common Sense philosophers who

[5] Valuable here are Paul Kristeller, Renaissance Thought (New York: Harper, 1961); Charles Schmitt and Quentin Skinner, eds., The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

manned the arts faculties of eighteenth-century universities, instructing youth in right thinking, the analogy of nature underlined the affinities between the divine mind and the human, each unthinkable except as reflecting the complementary Other. From the latter half of the seventeenth century, it is true, rationalist and positivist currents in the European temper grew increasingly skeptical as to the existence of an array of nonmaterial entities: fairies, goblins, and ghosts; devils and wood demons; the powers of astrology, witchcraft, and magic; the hermetic "world soul," and perhaps even Satan and Hell themselves—all as part of that demystifying tide which Max Weber felicitously dubbed the "disenchantment of the world."[6] Yet subtle arguments were advanced to prove that such a salutary liquidation of false animism and anthropomorphism served but to corroborate nonmaterial reality where it truly existed: in the divine mind and the human. For many eighteenth-century natural philosophers and natural theologians, the more the physical universe was drained by the "mechanicization of the world picture" of any intrinsic will, activity, and teleology, the more patent were the proofs of a mind outside, which had created, sustained, and continued to see that all was good.[7]

It would be a gross mistake, however, to imply that Christian casuistries alone perpetuated canonical restatements of the mastery of mind over body. The very soul of the epistemology and poetics of a Romanticism in revolt against the allegedly materialistic attitudes and aesthetics of the eighteenth century was the championship of mental powers, most commonly finding expression through the idea of the holiness of imagination and the transcendency of genius. Genius and imagination, no matter how designated, had been among the commonest themes of the rational Enlightenment: the basis of its developing discourse of aesthetics; the salt of its political theory, as Locke and Burke showed; even the ideological underpinning of its "scientific manifestoes."[8] Later on,

[6] See the argument in R. D. Stock, The Holy and the Daemonic from Sir Thomas Browne to William Blake (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982).

[7] For the relations of God and Nature see Amos Funkenstein, Theology and the Scientific Imagination from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

[8] Illuminating on the philosophy of imaginative genius are J. Engell, The Creative Imagination (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981); P. A. Cantor, Creature and Creator: Myth-making and English Romanticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984); and, more generally, G. S. Rousseau, "Science and the Discovery of the Imagination in Enlightenment England," Eighteenth-Century Studies 3 (1969): 108-135, and E. Tuveson, The Imagination as a Means of Grace (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1960).

contemporary philosophical Idealism in the form of Hegel-on-horse-back likewise interpreted the dynamics of world history as the process whereby Geist, or spirit, realized itself in the world, spiraling dialectically upward to achieve ever higher planes of self-consciousness. And we must never minimize the Idealist thrust of the developmental philosophies so popular in the nineteenth-century fin-de-siècle era—from Bosanquet and Balfour to Bergson, and influenced by Hegelianism no less than by the Origin of Species —which represented the destiny of the cosmos and of its noblest expression, man, as the progressive evolution of higher forms of being out of lower, and in particular the ascent of man from protoplasmic slime to the Victorian mind.[9]

Given this philosophical paean down the millennia affirming the majesty of mind, it is little wonder that so many of the issues which modern philosophy inherited hinged upon mapping out the relationships between thinking and being, mind and brain, will and desire, or (on the one hand) inner motive, intention, and impulse, and (on the other) physical action. In one sense at least, Whitehead was a true child of his time. Twentieth-century philosophers such as G. E. Moore still puzzled over the same sorts of questions Socrates posed, wondering what the shadows flickering on the cave walls really represented, and pondering whether moral truths exist within the realm of the objectively knowable. Not only that, but the kinds of words, categories, and exempla in circulation to resolve such issues have continued—for better or worse—to be ones familiarized by Plato, Locke, or Dewey.[10]

To its credit, recent philosophy—as Philippa Foot energetically argues below—has urged the folly of expecting to find solutions to these ancestral problems through honing yet more sophisticated variants upon the formulas traded by post-Cartesian rationalism or Anglo-Saxon empiricism. A few more refinements to utilitarianism or the latest model in associationism will not get us any further than will laboratory experiments in search of the true successor to the pineal gland. And when Richard Rorty pronounces the death of philosophy in his latest tour de force,[11] one wonders to what degree the age-old dualism has conspired to cause it. Rorty, like Foot, suggests that philosophers had just as well throw up their hands—perhaps even do better by denying the dualism

[9] See Peter Bowler, The Eclipse of Darwinism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

[10] See J. Passmore, A Hundred Years of Philosophy (New York: Basic Books, 1966).

[11] Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980).

of mind and body altogether. It may be, as Rorty maintains, that, philosophically speaking, "there is no mind-body problem,"[12] and that as a consequence Rorty is entitled, as a professional philosopher, to cast aspersions on, even to crack grammatical jokes about, all those who believe there is. For this reason, Rorty believes that "we are not entitled to begin talking about the mind and body problem, or about the possible identity or necessary non-identity of mental and physical states, without first asking what we mean by 'mental.'"[13] And as a direct consequence of his aim to shatter Cartesian dualism and the philosophies that built on its further dualisms all the way up to Kant, Rorty can announce his own aim in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature as being "to undermine the reader's confidence in the 'mind' as something about which one should have a 'philosophical' view, in 'knowledge' as something about which there ought to be a 'theory' and which has 'foundations,' and in 'philosophy' as it has been conceived since Kant."[14]

Above all, new bearings in philosophy—especially the way Wittgenstein proved a seminal impulse for many, phenomenology for others—have reoriented attention away from the traditional envisaging of emotions, desires, intentions, states of mind, acts of will, and so on, as "things," as inner natural objects with a place within some conceptual

[12] Ibid., 7. Rorty's fervor to smash dualism is everywhere apparent. For example, in this same introductory section entitled "Invention of the Mind," Rorty writes: "at this point we might want to say that we have dissolved the mind-body problem" (32), and a few sentences later, on the same page, "the mind-body problem, we can now say, was merely a result of Locke's unfortunate mistake about how words get meaning, combined with his and Plato's muddled attempt to talk about adjectives as if they were nouns."

[13] Ibid., 32. Rorty continues this passage by derogating the grand aims of contemporary professional philosophy: "I would hope further to have incited the suspicion that our so-called intuition about what is mental may be merely our readiness to fall in with a specifically philosophical language game." Here Rorty's polemical pronoun ("our") shrewdly hovers between professional philosophers on the one hand and interested amateurs who have thought about the dualism of mind/body on the other.

[14] Ibid., 7. The implication would seem to be equally true for the "body." But historically speaking, there have been three species of books about body, all of which have produced a large number of metacritiques in the last century: (1) those written by philosophers of mind with an interest in keeping the dualism (Rorty would say "philosophical language game") alive by diminishing the importance of body when considered in its physiological, or neurophysiological, state; (2) those by scientists (anatomists, physiologists, neurophysiologists, and other empirical laboratory experimenters) often concerned to demonstrate that the dilemmas called linguistic by the philosophers are actually as yet unexplored neurophysiological mysteries related to the workings of the central nervous system; and (3) those by a broad range of historians and other cultural commentators interested in the social dimensions of the mind/body problem when considered with respect to individuals or societies viewed collectively.

geography of the self, the causal connections between which it is our duty to discover by introspection and thought experiments. Such a reified view of being, thinking, and acting—a Marxist critic might say it is no more than is to be expected within commodity capitalism—has sustained devastating attack, and modern crosscurrents in philosophy have been claiming that we should rather attend to the meanings of our moral languages understood as systems of public utterance. Thereby we might escape from the sterilities of a figural mechanics of the mind which, as Alasdair MacIntyre has emphasized, and as Rorty has now demonstrated, threatened to drag moral philosophy down into a morass, and address ourselves afresh to more urgent questions of value and choice.[15]

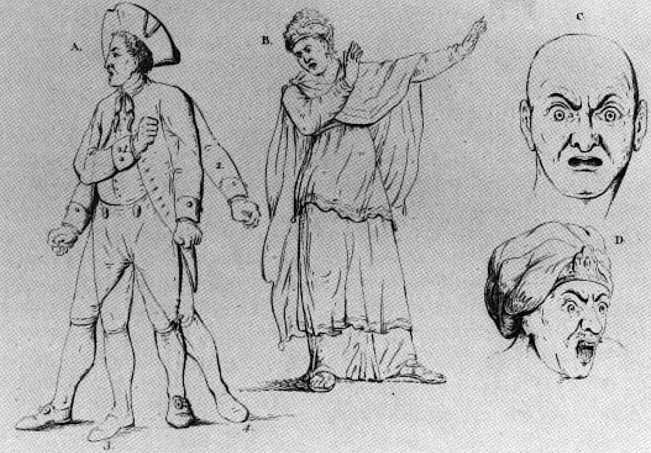

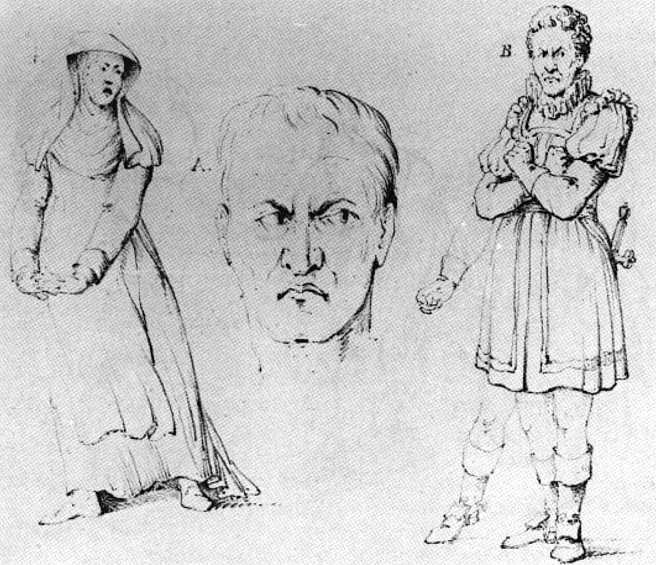

Comparable processes of revaluation have also transformed literary theory. In England, Victorian criticism (itself sometimes proudly hitched to the wagon of associationist psychophysiology) commonly believed its mission was to judge novelists and playwrights for psychological realism: were their dramatis personae credible doubles of real people? Somewhat later, various schools of criticism, enthused by Freudian dogmas, went one stage further, and took characters out of fiction and set them on the couch, attempting to probe into their psyches (how well was their unconscious motivation grasped?) and into the unconscious of their authors (how were their fictions projections of their neuroses?). Today's criticism has discredited such preoccupations with the physical presence and the psychic potential of characters as banal, as but another form of literal-minded reification. For many theorists today, especially the feminists, the task of dissecting the body of the text is coeval with that of the body of women, while the traditional notion of the authorial mind as creator—a notion reaching its apogee in Romanticism—has yielded to a fascination with genre, rhetoric, and langauge as the informing structures.[16]

[15] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984).

[16] In the process, the human body is abandoned, and discourses consulting the human form rather than "the body as text" or "the body as trope" become increasingly rare. Amongst them see John Blacking, The Anthropology of the Body (London: Academic Press, 1977); Julia L. Epstein, "Writing the Unspeakable: Fanny Burney's Mastectomy and the Fictive Body," Representations, Fall 1986, 131—166; Robert N. Essick, "How Blake's Body Means," in Unnam'd Forms: Blake and Textuality, ed. Nelson Hilton and Thomas A. Vogler (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1986). The more usual approach applies the paradigm "read the body—read the text," as if to equate the two through a metonymy, and as discovered in so many (often excellent) works of contemporary feminism (see those mentioned in n. 2 above). But these trends appear to be absent, or at least minimal, in contemporary philosophy; see, for example, Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination and Reason (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987). Further reasons for this recent development, viewed within the context of literary theory, are provided in H. Aram Veeser, ed., The New Historicism (London: Routledge, 1989).

We may applaud the transcendence—in philosophy, in criticism, and elsewhere—of crude mechanical models of the operations of thinking and feeling, willing and acting. This is not, however, to imply that the interplay of consciousness and society, of nerves and human nature, has somehow lost its meaning or relevance. Far from it, for it is important, now more than ever, to be able to think decisively about the ramifications of mind and body, their respective resonances, and their intersections, because the practical implications are so critical.

For ours is a material culture that is rapidly replacing the received metaphors that help us understand—or, arguably, mystify—the workings of minds and bodies. Deploying such models is nothing new. To conceptualize the mind, suggested Plato, think of the state; the understanding begins as a blank sheet of paper, argued Locke (for Tristram Shandy, by contrast, its objective correlative was a stick of sealing wax). Above all, during the last few centuries, the proliferation of machinery—watches, steam engines, and the like—has provided models for the functions of corporeal bodies and the processes of the understanding; the image of thinking as a mill, grinding out truths, was especially powerful.

Indeed, as Otto Mayr has remarked, particular forms of technology may even determine—or, at least, shape distinctive ways of viewing the mind itself.[17] Clockwork mechanisms as found in watches yield images of man, individual and social, as uniformly and predictably obeying the pulse of centrally driven systems. Such a behaviorist image of man-the-machine, Mayr suggests, was particularly prominent in the propaganda of ancien régime absolutism (and we may add, in images of factory discipline in the philosophy of manufactures). In Britain, the more complex regulatory equipment of the steam engine, with its flywheels and contrapuntal rhythms, perhaps offered a rather different metaphor of man: that of checks and balances, counterpoised within a more decentralized and self-regulating whole, suggestive perhaps of a kind of individuality in tune with the English ideology. And, more recently, in the aftermath of late-nineteenth-century positivism, neurobiology and neurophysiology have become persuaded that mind is brain, and that

[17] O. Mayr, Authored, Liberty and Automatic Machines in Early Modern Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986); L. Mumford, The Condition of Man (London, 1944); idem, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1963).

the brain is an entirely mechanical, machine-like instrument whose operations are barely understood because of the vastness of its complexity.[18] In this sense, the human brain is more complex than the largest computer.[19] This radical mechanism, shunning any traces of vestigial vitalism (of the old Bergsonian or Drieschian varieties), forms the unarticulated basis of practically all laboratory biology and physiology today, yet its roots, vis-à-vis mind and body, extend at least as far back as the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. In a sense, then, mechanism, at least viewed within its mind/body context, has come full circle back to its Cartesian, and somewhat post-Cartesian, model.[20]

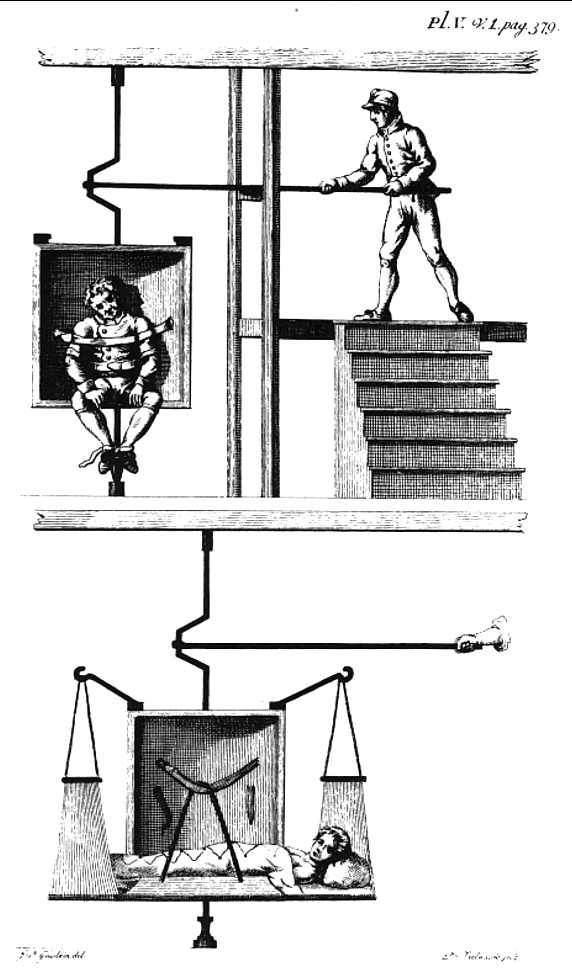

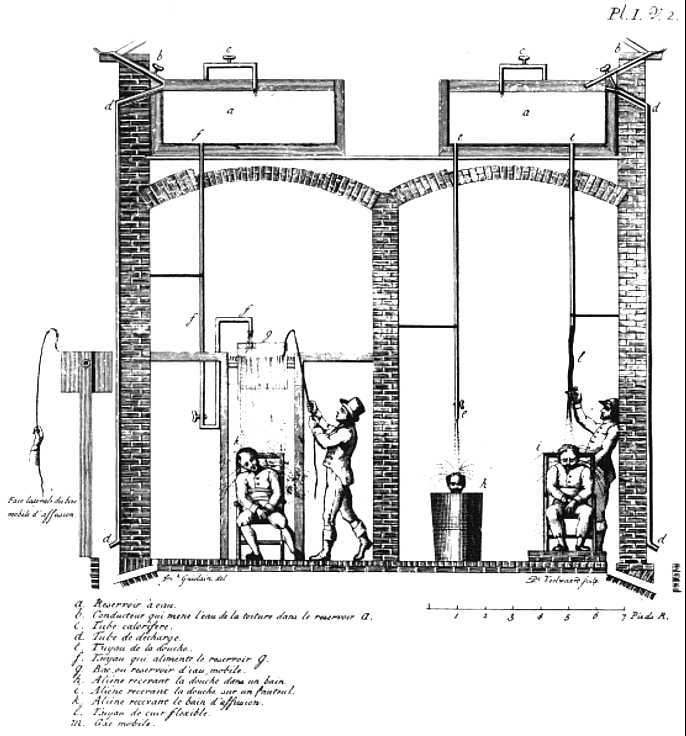

Mechanical models—realized in Vaucansonian automata—were obviously integral to Cartesian formulations of man as an intricate piece of

[18] For the reciprocity of mind and brain, see Patricia S. Churchland, Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind/Brain (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1986); John Eccles, The Neurophysiological Basis of Mind (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953); idem, Brain and Human Behavior (New York: Springer Verlag, 1972); idem, The Understanding of the Brain (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973); Marc Jeannerod, The Brain Machine: The Development of Neurophysiological Thought (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985); Morton F. Reiser, Mind, Brain, Body: Toward a Convergence of Psychoanalysis and Neurobiology (New York: Basic Books, 1984); Fred A. Wolf, The Body Quantum: The Physics of the Human Body (London: Heinemann, 1987). Arguing against the radical mechanism of these positions is Herbert Weiner, M.D., "Some Comments on the Transduction of Experience by the Brain: Implications for Our Understanding of the Relationship of Mind to Body," Psychiatric Medicine 34 (1972): 355-380. For the shrewd input of a Nobel laureate in physics on the question of material reciprocity, see E. P. Wigner, Emeritus Professor of Physics at Princeton University, "Remarks on the Mind-Body Question," in The Scientist Speculates: An Anthology of Partly Baked Ideas, ed. I. J. Good (New York: Basic Books, 1962), 284-302.

[19] Victor Weisskopf, Knowledge and Wonder: The Natural World as Man Knows It (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1979), 244.

[20] The endurance of these Cartesian models, from Descartes to the present, in regard to the mind/body dualism, as well as in such disparate academic territories as linguistics, medicine, and psychology, is discussed in William Barrett, Death of the Soul: From Descartes to the Computer (New York: Doubleday, 1986); Richard B. Carter, Descartes' Medical Philosophy: The Organic Solution to the Mind-Body Problem (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983); Harry M. Bracken, ed., Mind and Language: Essays on Descartes and Chomsky (Dordrecht and Cinnaminson, N.J.: Foris Publications, 1984); Marjorie Grene, Interpretations of Life and Mind: Essays around the Problem of Reduction (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971); idem, Descartes (Brighton: Harvester, 1985); Kenneth Dewhurst and Nigel Reeves, eds. Friedrich Schiller: Medicine, Psychology and Literature (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1978); E. H. Lenneberg, Biological Foundations of Language (New York: Wiley, 1967); Amélie Oksenburg Rorty, Essays on Descartes' Meditations (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1986); Margaret D. Wilson, Descartes (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978); Albert G. A. Balz, Descartes and the Modern Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1952). Some of these topics are anticipated in René Descartes, Lettres de Mr Descartes, où sont traittés les plus belles questions de la morale, physique, médicine, & les mathématiques (Paris: C. Angot, 1666-1667).

mechanism yoked, however mysteriously, to an undetermined mind—the whole amounting to the notorious "ghost in the machine."[21] Such Cartesian mechanical metaphors—widely condemned by Romantics old and new for their supposedly disembodying and alienating implications[22] —were commonly drawn upon, with rather conservative intent, to reinforce the age-old belief that homo rationalis was destined, from above, to govern those below.

But there are also significant differences between these old Romantic views of our world of artificial intelligence and cognition theory. The material analogues in vogue today, by contrast, are arguably far more challenging and less flattering to entrenched human senses of self. Ever since Norbert Wiener and Alan Turing, cybernetics, systems analysis, and the computer revolution have been changing our understanding of the transformative potentialities of machines. If the Babbagian computer was merely a device to be intelligently programmed "from above," the computers of today and tomorrow have intelligence programmed into them, and they possess the capacity to learn, modify their behavior, and "think" creatively—in a sense, to evolve. The more the notion of "machines that think" becomes realized, the more urgent will be the task of clarifying in precisely which ways we believe their feedback circuits differ from ours; or perhaps we will have to say, the ways in which those alien, artificial intelligences believe our calculating operations differ from theirs ! Human/robot interactions, once the amusing speculations of science fiction, may ironically become the facet of the mind/body problem most critical to that twenty-first century which is but a decade away. What is it, if anything, that gives us a "self," a personality, entitling us to rights and duties in a society denying these to artificial intelligence? Today, as in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the philosophers, especially philosophers of mind, speak out on these vital subjects. John Searle and many others regard "free will"—the traditional predicate of autonomous mind—as an unsatisfactory and obsolete answer.[23] And it is one of the strengths of Philippa Foot's chapter that she demonstrates the eighteenth-century legacy of this continuing problem.

[21] For this Cartesian legacy, see Aram Vartanian, Diderot and Descartes: A Study of Scientific Naturalism in the Enlightenment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953); and see, of course, Arthur Koestler, The Ghost in the Machine (London: Hutchinson, 1976).

[22] For modern critics of the supposedly dire consequences of Cartesian dualism, see F. Capra, The Turning Point: Science, Society and the Rising Culture (New York, 1982); M. Berman, The Re-enchantment of the World (London, 1982).

[23] John Searle, Minds, Brains and Science (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984). Modem neurosurgeons have made useful contributions to this subject, especially within the contexts of the complex ways in which the brain processes language in relation to a perceived external reality and to the role of the will within this reality, a subject of immense concern to poststructuralist theory, especially Derridean and post-Derridean deconstructionism. Among these Fred Plum, M.D., has been especially eloquent; see, for example, F. Plum, ed., Language, Communication and the Brain (New York: Raven Press, 1988); G. Globus, ed., Consciousness and the Brain (New York: Plenum, 1976).

III

If airing such issues may still seem frivolous or futuristic, it can hardly be fanciful to focus attention upon the transformations that living bodies and personalities are nowadays undergoing. Spare-part surgery became a fait accompli long before philosophers had solved its moral and legal dilemmas. Surgeons have implanted the kidneys, hearts, lungs of other humans, and even other primates. Surely such developments (it might have been thought) must have caused intense anxiety for identity in a culture that still speaks—if metaphorically—of the heart as the hub of passion and integrity, and the brain as the seat of reason and control. But it hardly seems to have proved so. Should we conclude that we are all Cartesians or Platonists—or maybe even Christians—enough to regard the bits and pieces of the body as no more than necessary but contingent appendages to whatever we decide it is that does define our unique essence? One wonders (skeptically) whether we would feel as nonchalant about brain transplants. Are we sufficiently confident in our dualism to believe that acquiring another's brain would not make us another person, or, indeed, a centaur-like monster? Contemporary philosophers such as Thomas Nagel think not,[24] and Professor Foot reminds us to what degree Enlightenment philosophers such as Locke and Hume pondered these matters, albeit in a different key.

And more perplexing perhaps, because more imminent, what of the implantation of fragments of brains, or elements of the central nervous system? Would these involve dislocations of identity?—the equivalent perhaps to the caricaturists' macabre vision of the Day of Judgment when the bodies of those dissected by anatomists and dismembered in war arise, yet with their parts grotesquely muddled and misassembled. Here we seem to be on terrain already laid bare by current practices within psychological medicine. In the psychiatric hospital, advances in neuropsychiatry enable us, through drugs and surgery alike, radically to transform the behavior and moods of the disturbed, so that we colloquially say that they have turned into "another"—indeed, a "new"—person. Can somatic interventions thus make a whole new self? Because the patients involved are "psychopathological" cases, to which regular

[24] Thomas Nagel, Mortal Questions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979); idem, The View from Nowhere (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

public legal constraints may not apply—or because, to put it crudly, such developments have been largely pioneered in the back wards, out of sight and out of mind—the dystopian implications of such medically induced personality transformations do not always receive full attention.[25]

Yet our dramatically increased capacity to wreak such changes, to make "new men" of old, is obviously a matter of great moment for the natural history of the somatic/psychic interface. The ethical and legal ramifications are obviously epochal—although law courts in their own fashion currently tend to handle such issues on an ad hoc, case-by-case basis, often hearing the authority of biology in the distant background. The widening horizons of genetic engineering, reproductive technology, and gender-change operations raise parallel issues as to wherein the unique—and permanent?—human personality should be deemed to reside: is it in genetic material that is essentially somatic, in particular organs, or in an experiential je ne sais quoi such as memory? (It may be one thing for the law, another for morality, and something different for the people themselves.)

Finally, though certainly not least, all these issues have been sharpened by our new technologies for managing death. Until quite recently, death was defined by some palpable and natural organic termination: the heart stopped beating, the breath of life expired. Even among the more superstitious and mystical, the "will to live" (Life Force?) was translated into organic dysfunction or disease. Medical technology, however, has marched on, from iron lungs to resuscitators and respirators. The implicit Cartesian in us can happily accept that a person remains alive even after the cessation of spontaneous body activity such as the heartbeat. But does that not leave us without a certain index of death at all?—or, indeed, signs of life? (Are some people simply more dead, or more alive, than others?) Medical attention has, of course, switched to the concept of "brain death"—which itself implicitly trades upon the humanist assumption that what finally defines mortal man is consciousness, while also embodying the more specifically modern faith that, while mind may still be more than brain, the needles registering presence of electrical impulses in the cortex betoken that the mind is still "alive." The paradoxical outcome of this eminently "humane" chain of reasoning is that we nowadays aggresively keep "alive" those in whom none of the indices of consciousness recognizable to the "naked eye" survive.[26]

[25] For criticism of invasions of the rights of mental patients, see T. Szasz, The Myth of Mental Illness (New York: Paladin, 1961). See also idem, Pain and Pleasure: A Study of Bodily Feelings (London: Tavistock Publications, 1957).

[26] On the modern medicalization of death see R. Lamerton, The Care of the Dying (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980).

IV

The argument so far has accentuated two points (the second developed below). First, the question about how we envisage the two-way traffic between mind and body is of fundamental concern for us today as well as for diverse cultural historians concerned with the diachronic past. It determines matters of grave import—ethical, legal, social, political, personal, sexual. The intricacies of exchange between consciousness and its embodiments are not gymnastic exercises designed to tone up mental athletes for the philosophers' Olympics, but are integral to everyone's intimate sense of what being human is and ought to be. Mental and physical interaction is a subject extending far beyond the historian's workshop or the philosopher's purview.[27] Idiomatic expressions—being somebody or nobody, or a nobody, being in or out of one's mind—prove the point beyond a shadow of doubt.

Thus our understanding, private and public, of mind and body has always been deeply important—for the law of slavery no less than for the salvation of souls. Yet it is crucial that we avoid the trap of hypostatizing "the mind/body problem" as if it were timeless and changeless, one of the "perennial questions" of the master philosophers—indeed, itself a veritable Platonic form, immemorially inscribed in the "aether." Toward this goal, amongst others, The Languages of Psyche: Mind and Body in Enlightenment Thought is largely dedicated: especially to the contextual dimensions and social implications of the two-way traffic. The terrain is so vast that we (the collective authors) have been able to cover only a few facets of this broad contextualism and historicism, and many volumes would be required to fill in the canvas more adequately. Even in specific terrains, history—social and political, religious and economic—has taken its toll. For one thing, as already suggested, the dilemmas involving disputed readings of psyche/soma relations, and the terms in which discussion has been conducted, have been radically transformed over the centuries.[28]

[27] Despite the unassailability of the crucial function they play there. For example, the late American philosopher Susanne Langer devoted her entire professional career to the interaction of mental and physical phenomena in an attempt to generate an aesthetics based on the link. See her Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art (New York: Scribner. 1953) and Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, 3 vols. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967-1982).

[28] Cf. W. I. Matson, "Why Isn't the Mind-Body Problem Ancient?" in Mind, Matter, and Method, ed. P. K. Feyerabend and G. Maxwell (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1966). This matter of origins viewed within the context of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century debates is discussed by Douglas Odegard in "Locke and Mind-Body Dualism," Philosophy 45 (1970): 87-105, and Hilary Putnam in "How Old la the Mind?" in Exploring the Concept of Mind, ed. Richard Caplan (Iowa City: Universky of Iowa Press, 1986).

At one time, to take an example, proof of the existence of a consciousness seemingly independent of this mortal coil counted because it seemed confirmation of a soul destined, as was hoped, for a glorious immortality; nowadays, by contrast, many defend autonomy of the mind against scientistic reductionisms predsely because no such heavenly bliss after death can be expected. Early-eighteenth-century thinkers were not confronted with organ transplants as problems for practical ethics. They did, however, puzzle themselves, at least mock-seriously, about the status of Siamese twins: one body, two heads—but how many souls did such creatures have?[29] Other philosophers and projectors of the time asked what a "soul" was anyway? Did all moving creatures possess one? When was soul acquired? Did it make any sense to ponder a cat's soul or a cow's? Could a black African be said to have the same soul as a white? (Blake's "little black boy" in Innocence was born "in the southern wild" and is black: "but oh," he pleads, "my soul is white.") These and other similar questions were asked under as many agendas as there were philosophers. The notion of multiple "personality," of course, came much later, once the techniques of hypnotism and dynamic psychiatry had revealed the disturbing presence of a plurality of apparently hermetically-sealed chambers of the consciousness (cogito ergo sumus, as it were).[30] In other words, concepts such as "soul" and "personality" must be handled with care, paying due respect to their resonances in context over time.

Second—and this is the key contention which forms the rationale for this volume—it would be a mistake to speak of the mind/body problem as if it were a conundrum that has always existed. Rather mind/body relations became pressing in the guise of the mind/body problem only rather recently, and in response to specific cultural configurations. Above all, it was the eighteenth century (to deploy that diachronic expression somewhat elastically) and the intellectual movement we term the Enlightenment, which problematized this feature of the human condition. How was this so? This is the question—construed in its broadest contexts—which we (the collective authors in this book) aim to address, fully aware that we want to continue dialogue about the matter, rather than to suggest any ultimate explanations or final words.

[29] See C. Kerby-Miller, ed., Memoirs of the Extraordinary Life, Works and Discoveries of Martinus Scriblerus (New York, 1966), for the sad story of Indamira and Lindamora.

[30] See S. P. Fullinwider, Technologies of the Finite (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982).

As indicated above, mainline philosophical currents from the Greeks onward adumbrated a mythic conceptual geography which, in its value hierarchy, elevated the ideal above the material, the changeless over the mutable, the perfect over the processual, the mental over the physical, the free over the determined, and superimposed each pair upon the others. Demonstrating such an order of things could not, it is true, be achieved without some ingenuity and acumen. After all, the existence of the eternal form of a table and the survival of the soul beyond the body, are neither of them immediate objects of sense experience.

Nor could such a metaphysic be established without intellectual aplomb. Aristotle's polished conceptualization of nature, for instance, is a far cry from the messy chaos of contrary motions and kaleidoscopic multiplicity of shapes which greets the innocent eye.[31] Christian apologetics in particular had to overcome what prima facie appear to be profound internal tensions, not to say contradictions, in its theology. The Christian faith, zealous in its denigration of the (original) sinfulness of the flesh, set particular value upon the immortal destiny of a unique, personal soul (an element absent, in different ways and for distinct reasons, from both Neoplatonism and Judaism). Yet at the same time, and no less uniquely, the Scriptures revealed that embodied man was made in God's image, that God's own Son was made flesh, and that His incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection were typologically prophetic of a universal resurrection of the flesh at the impending Last Judgment. Few creeds made too much of the otherworldly, but none so honored the flesh. This particular tension lay at the root of Augustine's ambivalence, forming the substratum of his ethics and epistemology, as well as his troubled view of mind in relation to body.[32] And those Christian exegetes and scholiasts who followed in Augustine's steps commented upon the paradox of flesh and fleshless within a single credo.

Thus the articulation of orthodox Christian theology might well be read as a heroic holding operation, attempting to harmonize the most unlikely partners. Through the Middle Ages and into early modern times, churchmen battled against the flesh, extolling asceticism, mortification, and spirituality, while believers were almost ghoulishly fascinated by the seemingly incorruptible tissues, freshly spurting blood,

[31] Michael V. Wedlin, Mind and the Imagination in Aristotle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989).

[32] For Augustine on mind and body see F. Bottomley, Attitudes to the Body in Western Christendom (London: Lepus Books, 1979), and Jean H. Hagstrum, The Romantic Body (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985), chap. 2.

and weeping tears of long-dead saints, yet simultaneously awaiting the resurrection of the body in expectation of a very palpable orgy of bliss in heaven.[33] The endlessly controversial status of the Eucharist—did the sacrament truly mean consuming the blood and body of the Savior? or was it essentially an intellectual aide-mémoire of Christ's passion and atonement?—perfectly captures the essential tension between the spirit and incarnation within Christianity.

Nor was the triumph of the "mind over body" metaphysic achieved without opposition. After all, antiquity itself had its atomists and materialists—Democritus, Diogenes, Epicurus, Leucippus, Lucretius—who in their distinct ways discarded the radical dualism of matter and spirit, denied the primacy of spirit, and proposed versions of monistic materialism which reduced the so-called nobler attributes to particles in motion and to the promptings of the flesh under what Bentham much later called the "sovereign masters, of pleasure and pain." The history of orthodox theology from Aquinas onward amounted to a war of words: a logomachy waged on behalf of what Ralph Cudworth, the late-seventeenth-century Platonist, was tellingly to call the True Intellectual System of the Universe, against advancing armies of alleged atomists, eternalists, mortalists, materialists, naturalists, atheists, and all their tribe of Machiavellian, Hobbist, and Spinozist fellow travelers, who were all supposedly engaged in hierarchy-collapsing subversion, intellectual, religious, political, and moral.[34]

Many have doubted whether these leveling metaphysical marauders were in fact real (or at least, numerous)—or were rather, as might be said, ideal, or ideal types—demonic bogeymen invented to shore up orthodoxy. They have doubted with good reason. Research is uncovering a larger presence of sturdy grass-roots materialism—as exemplified by Menocchio the Friulian Miller, with his cosmology of cheese and worms—than once was suspected.[35]

[33] Such paradoxes are brilliantly illuminated in P. Camporesi, The Incorruptible Flesh: Bodily Mutation and Mortification in Religion and Folklore (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); see also idem, Bread of Dreams: Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990); idem, The Body in the Cosmos: Natural Symbols in Medieval and Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989).

[34] See Amos Funkenstein, Theology and the Scientific Imagination from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

[35] E. Le Roy Ladurie, Montaillou (New York: Vintage, 1979); Carlo Ginzburg, The Cheese and the Worms (New York: Penguin, 1982). For the culture of "plebeian" materialism, see M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky (Cambridge, Mass., 1968); Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Polities and Poetics of Transgression (London: Methuen, 1986).

Yet, after every qualification, it is clear that the overarching hierarchical philosophy of the mind/body duo became definitive for official ideologies in a European sociopolitical order which was itself massively and systematically hierarchical.[36] Often articulated through correspondences between the bodies terraqueous, politic, and natural, the mind/body pairing was congruent with, and supported by, comprehensive theories of cosmic order which attributed to every last entity of Creation its own unique niche on that scale of beings stretching from the lowest manifestation of inanimate nature up to nature's God. On this great chain, the material was set beneath the ideal, and man was "the great amphibian," pivotal between the two.[37]

This bonding of mind and body was, moreover, all of a piece—as hinted above—with a divine universe presided over by a numinous celestial wisdom. Were mind not lord over matter—were the relations between man's soul, consciousness, and will on the one side, and his guts and tissues on the other truly baffling and ambiguous, would that not have been a scandal in a cosmos created and ruled by a Transcendent Mind, pure Being? As Simon Schaffer argues below in regard to Joseph Priestley, only what one might call perversely heterodox believers, with theologicopolitical fish of their own to fry, would contend that the doctrines of immaterial minds and souls so cardinal to Christian orthodoxy were downright heresies. Lies, moreover, even inimical to the gospel, and, by contrast, promoting a deterministic philosophical materialism as their pristine faith, were problematical in another way.

There was, of course, abundant scope within Christian belief for heresy, and much of that was radical. Yet most rebel creeds involved attacks upon the banausic "knife-and-fork" materialism of paunchy prelates and the espousal, from Luther through the New Light and the Church of Christ, Scientist, of more intensely spiritual outlooks that established churches with their feet on the ground of Rome or Canterbury allowed. Many of the most exciting, modernizing philosophical movements in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries aimed to slough off what were seen as the excessively materialist Aristotelian components of Scholasticism, replacing them with the more idealistic doctrinces of Neoplatonism and Neo-Pythagoreanism and dozens of grass-roots varieties of the two. Reijer Hooykaas, the contemporary Dutch historian of

[36] L. Barkan, Nature's Work of Art: The Human Body as Image of the Worm (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975).

[37] A. O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1936) remains the classic discussion of the meanings of hierarchical metaphysics.

science, has suggestively drawn attention to the congruence between the Protestant God and the transdendental voluntarism of the "new philosophy."[38] It is a similitude—or at least a convergence—that needs to be weighted in all our discussion of the mind/body relationship in modern times.

Hence the first comprehensive and sustained questioning of mind/body dualism, and the wider cosmology of which it was emblem and authorization, came with the Enlightenment.[39] The relationship was eventually analyzed, explored, questioned, contested, and radically re-formulated—a great intellectual wave sweeping over western Europe from the middle of the seventeenth century onward. The terms of the debate were fierce and the stakes (in the cases of scientists and divines) could be high. Indeed, some even rejected root-and-branch its very terms. There was no single line of attack, and certainly no uniform outcome. It was a dialogical undertaking—in Bakhtin's sense—whose grandness could only be gleaned in the architectural magnificence of its details; in the case at hand, in the ramifications and implications of the debate that seemed to touch on every single subject under the sun. But in a multitude of ways, as the contributions to this volume reveal, what hitherto had been taken as a fact of life—albeit not without its difficulties and unrelenting tensions—became deeply problematic to many and repugnant to some.

In certain respects the fabric came apart at the seams not because of ideological animus or ulterior political motives, but because inquiry inevitably uncovered loose threads begging to be pulled. Essentially internal investigations in science and scholarship, new discoveries and technical advances, all served inevitably—though not uncontroversially—to modify the mental map. As Robert Frank shows below, anatomy was one of these fields. Ever since the Renaissance endeavors of Vesalius, Fallopius and others, the forging of more sophisticated techniques of postmortem dissection as part of the rise of anatomy teaching stimulated

[38] R. Hooykaas, Religion and the Rise of Modern Science (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1972). Illuminating also are I. Couliano, Eros et magic à la Renaissance (Paris: Flammarion, 1984), and W. Leiss, The Domination of Nature (New York, 1972); and, for the long-term retreat of the "animist" worldview, E. B. Tylor's anthropological classic, Primitive Culture (1871).

[39] Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment (Boston: Beacon, 1964) remains the most penetrating account of the metaphysics of the Enlightenment. S. C. Brown, ed., Philosophers of the Enlightenment (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1979) contains valuable discussions of philosophes from Locke to Kant.

intense curiosity about the relationship between structure and function, normalcy and pathology, the living body and the corpse on the slab.