Industries, Status Hierarchies, and Alliances: Cross-Cutting Spheres of Japanese Business

The names of Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo are well known as the remnants of the prewar zaibatsu groupings operating under family-controlled holding companies. But these represent only a fraction of the vast complex of elaborate alliances that make up the Japanese economy and bring firms into complex and often overlapping networks of vertical, horizontal, and diversified relationships. There exists in Japan no single, universally accepted system for classifying these relationships. Nevertheless, we can differentiate four broad categories of alliance that are typical in Japan, which are referred to here as (1) the intermarket keiretsu, (2) the vertical keiretsu, (3) small-business groups, and (4) strategic alliances, including joint ventures and project consortia.

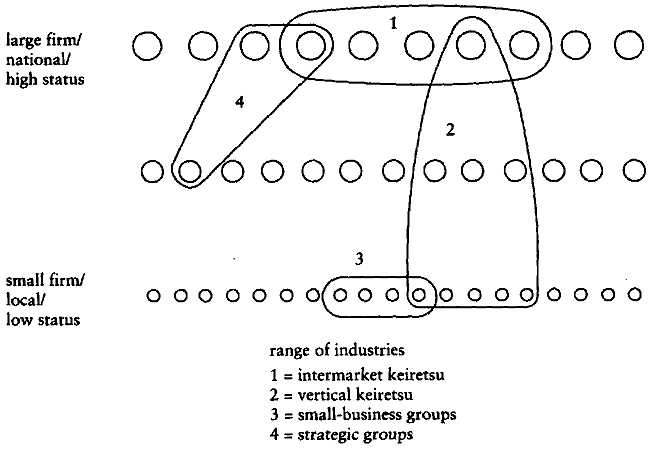

Figure 3.1 depicts these relationships schematically, showing their representation in different market sectors and their location in the business community. The horizontal axis reflects the diversity of market sectors in which the group is involved, with a wide span indicating broad industrial representation. The vertical axis indicates firms' positions within the structure of firm stratification. The "traditional" sector at the bottom reflects the central role of local social networks of family, friendship, and community ties, while the "modern" sector at the top reflects embeddedness in a national network of business elites (the zaikai )-the Japanese social economy is acutely sensitive to company size, and security, status, wealth, and power accrue to the largest.

The Intermarket Keiretsu Groupings of large firms based around a major commercial ("city") bank are referred to variously as keiretsu, kigyo shudan or kigyo gurupu (enterprise group). As noted earlier, I have adopted the keiretsu terminology and have added the qualifiers "intermarket" and "vertical" to characterize two quite different forms of group structure. This form of alliance, discussed in considerably greater detail below, represents loosely structured associations of large relatively equally sized firms in diverse industries, including banking, commerce, and manufacturing. The social communities of business that they represent are the elite in Japan-economically, politically, and socially.

Fig. 3.1. Cross-Cutting Social Spheres: Industrial Diversity, Status Position, and Alliance Form.

The Vertical Keiretsu In contrast to the highly diversified character of the intermarket keiretsu, the vertical keiretsu are tight, hierarchical associations centered on a single, large parent firm and containing multiple smaller satellite companies within related industries. While focused in their business activities, they span the status breadth of the business community, with the parent firm part of Japan's large-firm economic core and its satellites, particularly at lower levels, small operations that are often family-run. Most firms in intermarket keiretsu maintain their own vertical keiretsu, leading to an intersection of these two forms, as seen here.

The vertical keiretsu can be divided into three main categories. The first are the sangyo keiretsu, or production keiretsu, which are elaborate hierarchies of primary, secondary, and tertiary-level subcontractors that supply, through a series of stages, parent firms. The second are the ryutsu keiretsu, or distribution keiretsu. These are linear systems of distributors that operate under the name of a large-scale manufacturer, or sometimes a wholesaler. They have much in common with the vertical marketing systems that some large U.S. manufacturers have introduced to orga-

nize their interfirm distribution channels (Stem and El-Ansary, 1977). A third-the shihon keiretsu, or capital keiretsu-are groupings based not on the flow of product materials and goods but on the flow of capital from a parent firm, and are sometimes referred to in Japanese academic writings by the German term Konzern. The leading contemporary examples are the railroad groups of Tokyu and Seibu, which have diversified from train lines into real estate, hotels, department stores and distribution, and travel and recreation businesses.

Small-Business Groups Firms of fewer than a thousand employees account for over half of all sales and assets in the Japanese economy but are often overlooked in favor of the more conspicuous large firms. One of the ways that small firms have tried competing with the more efficient large-firm sector is through collaboration. The result is a rich panoply of producers and purchaser cooperatives, traditional and high-technology industrial estates (the last are sometimes known as "technopolises"), and neighborhood associations. I have labeled these collectively as "small-business groups."

Small-business groups involve a considerably greater diversity in 'the type of interfirm organization represented than do the intermarket or vertical keiretsu. They are sometimes focused on a single industry but also frequently bring together firms across multiple industries, positioned horizontally and organized within a common geographical nexus. Small-business groups trade largely in social currency and are closely tied to the local communities of which they are a part.

Strategic Alliances Strategic alliances include a wide range of inter-firm organizations based on relatively focused instrumental needs. They are sometimes called "functional" groups (kino-teki shudan ) though "ad hoc" is probably closer; they include joint ventures, project consortia, and various other forms of cooperation (in Japanese, the popular word teikei ) that move firms outside their traditional keiretsu groupings into new alliances that bridge industries and utilize new technologies. Strategic groupings cut across all sectors of industry and society, often in diagonal relationships that span diverse market sectors and social positions. Strategic alliances have increased dramatically in frequency in Japan in the 1980s, as they have in the United States. Large firms in Japan, for example, are now establishing relationships with small, high technology firms in an attempt to expand beyond their traditional industries (see, for example, Imai, 1984).