PATTERNS

8.

Religious Professionals

Selective memory is no doubt essential to the human condition. The only way we can see ourselves as coherent is to revise history continually. Some clerical historians reorder the past by silencing the role of clergy in movements they judge unorthodox. In recent times this tendency has coincided with the search by lay historians of religion for truly nonclerical, "popular," or even "pagan" traditions. But except when the clergy is of a different caste or race, we are unlikely to find sharp divergence between their thinking and that of the laity. This is particularly so in Catholic areas like the rural north of Spain which produced their own clergy and even exported them. It is not surprising that some priests and religious abetted the seers of Ezkioga.

Vocations

In 1931 there were about 2,050 diocesan priests born in the diocese of Vitoria and by my estimate about 2,700 other male religious and 5,550 female religious born there. Some Basque families regularly produced

clergy and religious for generations. Consider, for instance, the family of David Esnal, a priest living in San Sebastián who in 1932 and 1933 was in guarded contact with Patxi Goicoechea. Esnal's brother was a Franciscan and his sister was a Franciscan Conceptionist in a convent in Villasana de Mena (Burgos). His brother Roque had married a woman who had a cousin who was a Franciscan Conceptionist in the same convent. Of Roque's eight children, two sons were diocesan priests and one a Franciscan and a daughter was a Franciscan Conceptionist known for her holiness. In two generations, Esnal's and the next, seven out of twelve persons became diocesan priests, nuns, and male religious.[1]

I extrapolated the number of religious vocations from the number of diocesan priest vocations using the ratio of 4 to 1 that holds for Ataun, Zeanuri, and Navarra as a whole. For the Franciscan Conceptionist: Urquizu, "Sor María Paz." Esnal (b. 1888) wrote Patxi from San Sebastián on 31 December 1932 to pray for him and come to see him but not to tell anyone (private collection).

Families with many vocations were at least moderately well-off, for prior to the end of the nineteenth century the regular orders required dowries and it could be expensive to educate a secular priest. Laypersons in these clans—the nieces and nephews, brothers and sisters, or mothers and fathers of priests or religious—came to have an easy familiarity with the profession. Such persons were less easily cowed by their parish priest or bishop. They knew the inside gossip, the politics of appointments at the diocesan, national, and Vatican levels, and the currents of opinion within the church. They took full advantage of the alternatives in liturgy and moral theology which different priests and religious orders had to offer. Individuals like Carmen Medina, José María Boada, and Pilar Arratia who had the resources and the inclination to found orders and restore church buildings had direct social access to archbishops, cardinals, nuncios, and the Roman Curia.

Not only clans but entire towns became famous as nurseries for the clergy. Some places specialized in male or female religious of a given order, others were more diversified; some specialized in diocesan clergy. In 1935 Zeanuri, a mountain town in Bizkaia with 2,500 inhabitants, was proud to be the birthplace of 53 living priests and seminarians, 106 male religious, and 109 female religious.[2]

Zeanuri'ko abade (Priests from Zeanuri). I thank Ander Manterola for this reference. For 1923 see Gorostiaga, AEF, 1924, p. 124. For the specialization of Dima in Trinitarians see Irukoistar, Dima.

A survey of clergy in the diocese of Vitoria in 1960 (by then essentially the province of Alava) showed that some towns producing many religious did so irregularly. These vocations seem to have corresponded to the efforts of particular priests or recruiters. Members of religious orders have described to me friars who came to their village, gave talks at the school, and convinced whole sets of friends to join the order. The route to a vocation could also be through a parish preceptoría . This was a school, generally free, that often prepared children for the orders or seminaries favored by the particular priest who ran that school. From 1902 until his death in 1961 Bruno Lezaun of Abárzuza (Navarra) stimulated through his schools around a thousand vocations.[3]

Duocastella, Sociología y pastoral, chap. 6; Ricart, "Bruno Lezaun"; Cipriano Lezaun, Don Bruno; Pazos, Clero navarro.

But other towns, presumably those like Zeanuri in which vocations became a family matter, maintained their role over several generations. If we compare vocations by size of town of origin, the diocesan priests of Vitoria in 1931 came far less from the industrial areas around Bilbao, San Sebastián, Eibar, and Irun and the fishing towns along the coast and more from the agricultural and pastoral uplands.

When we look at the towns within the immediate zone of the Ezkioga visions which for their size produced the most priests, we find those towns that stayed faithful to the Virgin of Ezkioga the longest: Zegama (23 priests from a population of 2,119), Albiztur (8 priests from a population of 805), and Ataun as well as Itsaso, Ormaiztegi, Legorreta, and Ordizia.[4]

Controlling for size of town, the most vocations came from the adjoining Duranguesado and Villarreal sectors of Bizkaia and Alava, the mountainous band of Gipuzkoa from Zegama to Oiartzun, the southeastern corner of Alava, and the Campezo area of Alava. In the 1931 directory of the diocese of Vitoria I counted the diocesan priests born in each town, then calculated the number of inhabitants per priest for those towns that were the birthplaces of five or more priests. Conversely, for towns of six hundred inhabitants or more, I made a list of those towns producing the fewest diocesan priests. Since I measure vocations by all priests living in 1931, to some extent the results reflect population distributions prior to that year.

Ataun, the home of two prominent Ezkioga seers, had 2,424 inhabitants in 1931. Thanks to a careful count of its vocations we know that in that year it was the birthplace of 26 living diocesan priests, 60 nuns, and 37 male religious, that is, about four times as many male and female religious as secular priests. In 1931 Ataun had approximately four hundred households. About one in six had a living member who was a priest or religious, as follows:[5]

Derived from Arín, Clero de Atáun. For Zeanuri in 1935 the equivalent figures are 136 houses with one vocation, 23 houses with 2 (total = 46), 9 houses with 3 (27), 4 houses with 4 (16), 7 houses with 5 (35), and 1 house with 7 (7) (from Zeanuri'ko abade, 19).

|

Vocations in Ataun often occurred in family clusters. One in three individuals with a vocation had a sibling with a vocation. About one in five had an uncle or aunt or niece or nephew on their father's side with a vocation. We do not know how many had relatives through mothers, but there were probably as many as through fathers. This would mean that a majority of Ataun's religious or clergy had a close family relative in religion.[6]

Out of 123 Ataun vocations in 1931, 47 had sibling clerics, 25 had near relatives on the father's side, and 20 had both kinds. Figures for the 13,000 vocations in Navarra in 1980 show similar proportions. Slightly more than one-third had siblings as religious or priests; see Imízcoz, Una Emigración particular, 462, citing figures from J. A. Marcellán Eigorri, Cierzo y bochorno: Fenómeno vocacional de la Iglesia en Navarra (1936 y 1986) (Pamplona: Ed. Verbo Divino, 1988). For vocations of secular priests see Pazos, Clero navarro.

The houses with the most vocations were on the whole the more prosperous farms. Several of their families, like Arín and Tellería, had produced religious and priests regularly in previous centuries. The rise of active orders and the endowment of scholarships at seminaries at the end of the nineteenth century opened up clerical careers to more people, and it was from the 1890s that the boom in vocations in Ataun occurred. The great revolution came not in the secular clergy but in the religious orders. Prior to this period, the religious from Ataun were concentrated more in contemplative orders, particularly Benedictine monks and Cistercian Bernarda nuns. As more orders returned to Spain at the end of the century, entrance became easier and vocations of religious jumped to a high level in 1890–1909 and increased 50 percent more in 1910–1929.[7]

Houses with most vocations: Larrazea, Lauspelz, Orlaza-aundia, Telleri-aundia, Arin-aundia, Arratibel-azpikoa, Geaziñe-zarra, and Itzate-berri.

There was now room in the secular and regular clergy for the wealthy and the humble, the intellectual and the worker. In 1931 Ataun natives were seminary professors, pastors of large and prosperous parishes, directors of schools, and mother superiors. Others were coadjutants, a Jesuit tailor, a Passionist convent cook, and Benedictine, Capuchin, and Franciscan lay brothers. Among the nuns there were teachers and nurses but also cooks, ironers, cleaning women, and other lifelong menials. The orders people chose were generally

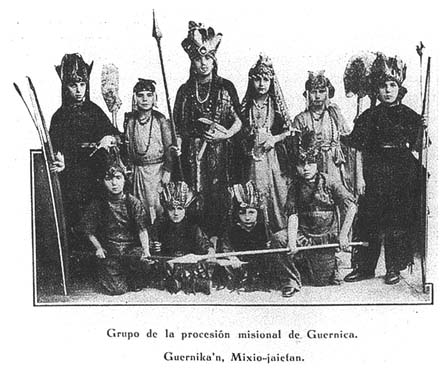

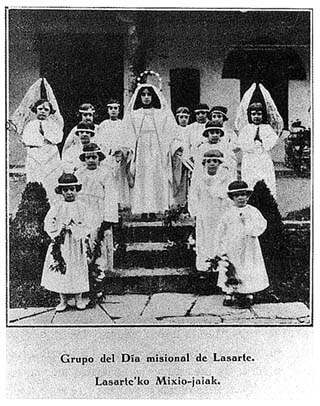

Children of Gernika dressed as Native Americans for mission procession, 1930.

From Nuestro Misionero, January 1930. Courtesy Instituto Labayru, Derio

those with houses closest to Ataun. Youths often entered the same order as their aunts, uncles, or siblings (five brothers from Orlaza-aundia became Benedictines, four sisters from Lauspelz became Daughters of Charity and their brother joined the Vincentians), and there were families whose tradition was to provide secular priests.

The religious orders did not keep the youths of Ataun close to home. First, they sent them to a novitiate, the most distant of which were in Paris and Madrid. Then they assigned them according to their particular calling and the order's needs. In 1931 only those who had become secular priests or contemplative nuns or monks were likely to return to the diocese. The active male religious were often found working abroad, particularly in Latin America, and the active nuns mainly elsewhere in Spain. In all, half of Ataun's vocations were posted out of the diocese; one out of five was out of Spain.

If these figures hold for the diocese as a whole, they should give us pause. The period 1918–1930 was a golden age of missionary propaganda, particularly in the north. The heartland of conservative Catholic Spain was not a closed, ingrown society but one with intimate family links throughout the world. In

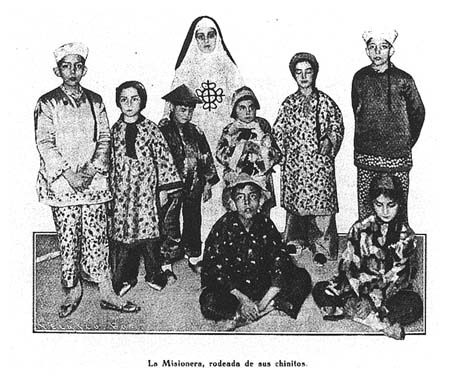

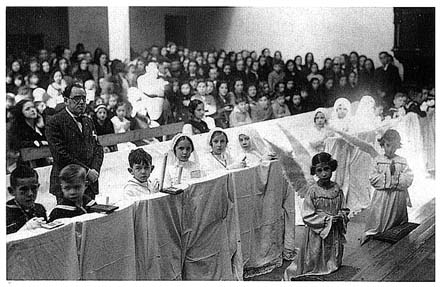

Children dressed as Chinese for mission pageant in Vitoria, 1932. From

Iluminare, 20 February 1932, p. 56. Courtesy Instituto Labayru, Derio

1931 there were natives of Ataun in China, Jerusalem, the United States, many countries in Latin America, and France in an ecclesiastical version of the great worldwide diaspora of European peasants at the opening of the century. Through letters and rare visits these religious kept in touch with their relatives at home.[8]

Imízcoz, Una Emigración particular, 470. For Durango's missionaries see Anitua, Nuestro misionero 1932. Perea, El Modelo, 2:881-1142, describes the organization of the mission effort.

We have seen that interest in missions extended even to children, who participated in the conversion of heathens through monthly magazines and dressed in elaborate costumes for annual mission pageants. In some of her visions Benita Aguirre heard the Virgin ask her to pray for the conversion of the Chinese. Some of the same families contributing alms and promises to the Ezkioga vision network had brothers, sisters, uncles, and aunts who were missionaries.[9]

See Benita's vision of 23 October 1932, in SC D 118. On the previous day she heard the Virgin ask for prayers for the Jews.

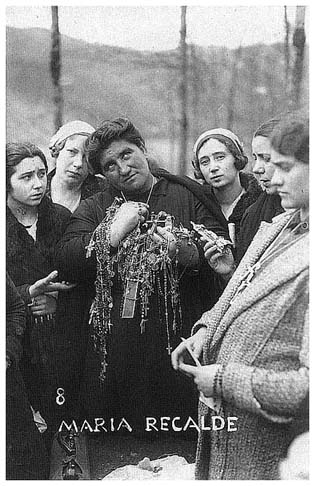

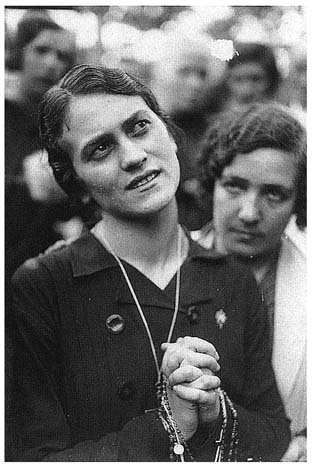

For women especially missionary work offered the possibility of holy adventure in wild contrast to life on the farm or in an urban apartment. Teresa de Avila dreamed as a child of becoming a missionary. From around 1910 Basque and Navarrese women could fulfill these age-old fantasies. María Recalde was from Berriz, where a new missionary order of nuns had been founded in her lifetime; the founder, Margarita María López de Maturana (d. 1934), was a

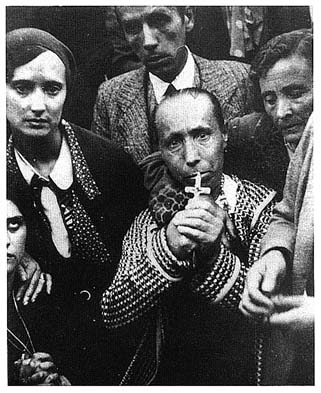

Women missionaries: masthead of magazine from Mercedarians

of Berriz, 1932. Courtesy Instituto Labayru, Derio

candidate for beatification. Some of the Mercedarian Sisters of Charity trained in Zumarraga went overseas, and there was a new house for female missionaries in Astigarraga as well. These orders depended on alms and new vocations to keep up their mission work, so they kept the Basque public well informed of their activities. The result was a region in which not just families—Esnals or Ayerbes—but entire towns had a proprietary interest in the church.[10]

Imízcoz, Una Emigración particular, 493-495; Ruíz de Gauna, Catálogo, includes fourteen different mission magazines published in Gipuzkoa, Bizkaia, Alava, and Navarra in the 1931-1936 period; other magazines, like La Milagrosa y Los Niños (Vincentians, Madrid) and El Siglo de las Misiones (Jesuits, Burgos), circulated in the area.

The importance of locally born clergy becomes obvious in towns that produced many religious. There virtually everyone was either related to or neighbor to the family of a priest or other religious. Resistance to diocesan policy on Ezkioga was strongest in towns like Zegama, Ataun, Itsaso, and Ormaiztegi precisely because in such an intensely devout rural society only priests or religious, or those who enjoyed their support, could resist the hierarchy. In the townships that produced many vocations, a kind of kin-based ecclesiastical culture was strong enough to allow some people to make up their own minds.

Sometimes more important than the village parish priest were the sons or daughters of the village who were priests or religious elsewhere but who returned to the village for visits to their families. Among both kinds of priests, those most friendly and open had the most influence in public opinion about the visions. José Domingo Campos, the pastor of Ormaiztegi, was a native of the village but never let on how he felt. "Nunca se supo [We never knew]," some of his most assiduous parishioners told me. When parishes were deeply divided, such priests found it

prudent not to express personal opinions or give sermons on the subject; they often limited themselves to reading diocesan decrees. Priests or religious who came from the village but practiced elsewhere might be less hesitant to speak their minds.

The Parish Clergy

I know of no diocesan priest who had visions at Ezkioga, but in the first months of the summer of 1931 many priests expressed pride in their seers, accompanied them to the vision site, stood with them as they saw what they saw, and debriefed them afterward. There were also those who held back from the start. Consider the six priests in Zumarraga. Two did not let their sympathies show. Antonio Amundarain and Andrés Olaechea were enthusiastic organizers and participants. Juan Bautista Otaegui sometimes led the rosary at the vision site in July 1931 and until the fiasco in October believed his cousin Ramona Olazábal. Miguel Lasa, the most approachable and best loved curate in Zumarraga, openly opposed the visions. He was the son of a charcoal-maker in Ataun, and it was to him that the Ezkioga milkmaid had taken the first girl seer. He spoke out against Patxi's theatrical trances: "The Virgin does not come to scare people." He warned at once that Ramona's wounds could have been faked. And in 1932 he instructed parishioners not to participate in the stations of the cross at Ezkioga.[11]

Based on extensive testimony 1982-1984 from Zumarraga residents, fellow priests, and religious. For Otaegui, ED and EZ, 11 July 1931; for Lasa quote, Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 11 September 1983.

In March 1932 Juan Casares, the curate of Ezkioga in charge of Santa Lucía, sent a letter to Justo de Echeguren, the vicar general, who at that time was actively planning with Padre Laburu the talks that would discredit the visions. The letter is evidence of division among local priests. It seems that the curate of nearby Itsaso had been boasting that the vicar general had called him in and approved of his stance (in Casares's words a stance "of credulity and encouragement") toward the seers. In the Itsaso annex of Alegia down the road from Ezkioga seers and believers could be sure of a friendly ear in confession. Obviously peeved, Casares asked if the Ezkioga priests should change their policy:

Pray let us know if we ought to favor and promote these apparitions, in which case we will avoid the animosity of the people who, emboldened by this priest and a few others, have got to the point of making our lives almost impossible and our ministry unfruitful, and we will avoid as well letters complaining about us being sent to you, although in any case if my conduct has not been as it should be, you may shift me somewhere else, in which case you could count of course on my obedience.

Perhaps the vicar general was using the Itsaso priest as an unwitting informant or perhaps he was trying to provide some kind of church outlet for the pilgrims. In any case, his task as the head of a deeply divided and at times strong-headed

clergy was complicated, and one can understand why he let Laburu do the convincing.[12]

Casares to Echeguren, Santa Lucía, 18 March 1932, ADV, Ezkioga. The Itsaso priest claimed that Echeguren gave him "the express command to inform him of what was going on in this matter."

To understand fully how the clergy made up their minds about Ezkioga, we need to know about their internal, informal groupings. The clergy and seminarians were divided, largely along linguistic lines, between those who cultivated a Basque identity and those who cultivated a Spanish identity. Many of the more cultured younger priests with Basque leanings, inside and outside the seminary, looked to the teachers José Miguel de Barandiarán and Manuel Lecuona as their leaders. One of these younger priests was Sinforoso de Ibarguren, the pastor of Ezkioga, who participated in the Eusko-Folklore Society. From the vert start Barandiarán and Lecuona, as they told me separately, felt that despite their curiosity about the visions as a human phenomenon they as priests should not encourage or validate them by going to the site. In all the years of visions, they never did. A young member of their group did go and wrote one of the only negative articles published about the visions in the summer of 1931. Yet other priests with Basque Nationalist sympathies were swept up by the same hope for a divine sign in favor of the race which moved the Nationalist writer Engracio de Aranzadi and the newspapers Euzkadi, Argia , and El Día .[13]

Masmelene, EZ, 15 July 1931; José Miguel de Barandiarán, Ataun, 9 September 1983; Manuel Lecuona, Oiartzun, 29 March 1983; cf. for an enthusiastic Nationalist, Apezbat [a priest], Amayur, 24 July 1931.

But even in July Basque Nationalist clergymen were not the key actors. The organizers of the prayers seem to have been José Ramón Echezarreta, the brother of the owner of the field, who had been in Latin America, and above all, the Zumarraga parish priest Antonio Amundarain and the local directors of the Aliadas. Particularly enthusiastic in this respect was the assistant priest of Zumaia, Julián Azpiroz. But when the bishop forbade priests to go to the site, Amundarain and his group obeyed, regardless of their private sympathies. After Echeguren's verdict against Ramona, most of the Basque Nationalist clergy turned against the visions. Those who stuck with the seers were Carlists, especially Integrist Carlists. By 1934, except for one group of believers in Zaldibia, the Ezkioga visions, to the extent that they were politically defined, were an affair of the pro-Spanish right.[14]

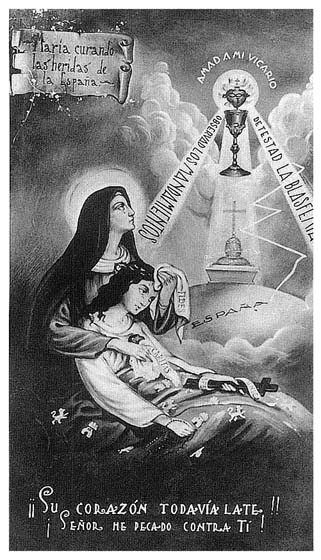

In 1934 the Basque archbishop of Valladolid launched a drive to raise money to build the church of the Great Promise. The promise of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to the Jesuit Bernardo de Hoyos—that Christ would reign in Spain with more devotion than in other nations—naturally raised the hackles of Basque Nationalists, who did not consider Spain their country. La Constancia collected contributions, and the printed lists of contributors were a way for the Carlists and Integrists to stand up and be counted on an issue that bore the approval of Bishop Mateo Múgica of Vitoria himself. Juan Bautista Ayerbe was one of the first contributors, and Conchita Mateos, Tomás Imaz, Juana Usabiaga, and several priests who had been or continued to be sympathetic to the Ezkioga cause proclaimed their Spanishness in this way.

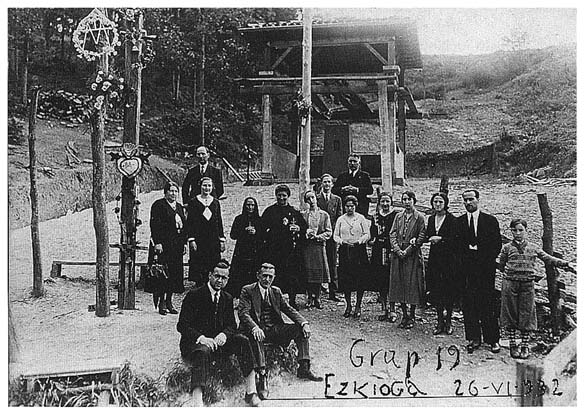

Zegama in particular was a stronghold of clerical sympathy for the visions. Of the twenty-three priests in the diocese native to Zegama, at least seven were at some point enthusiastic supporters. Foremost among them was the parish priest, José Andrés Oyarbide Berástegui (b. 1868), who worked with Padre Burguera, took down the Zegama vision messages, and forbade the seers there to tell the Ezkioga priest what they saw. His sister Romana often accompanied the child seer Martín Ayerbe to Ezkioga. In Zegama Oyarbide was assisted by a brother, and another curate was also a believer.[15]

On Oyarbide and sister, Rigné to Olaizola, Ormáiztegui, 4 September 1932; R 59; and B 624-628. The other curate was José Cruz Beldarrain (b. 1889, Oiartzun), Oiartzun, 29 March 1983.

From the same generation was José Antonio Larrea Ormazábal (b. 1869), Benita Aguirre's parish priest in Legazpi. At first he accompanied her to Ezkioga and took her statements; later he turned sharply against the visions. Francisco Aguirre Aguirre (b. 1873) was a curate in Irun. Like Juan Bautista Ayerbe, he

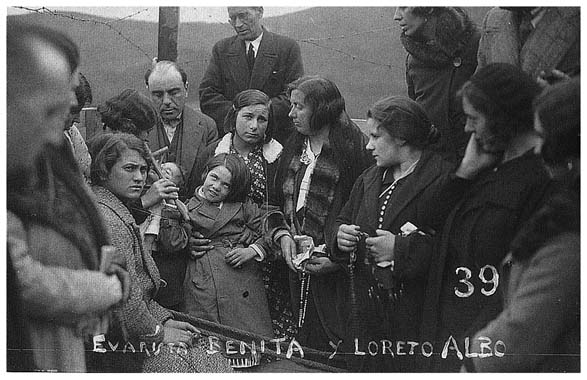

provided a link to the earlier visions at Limpias. He had been on a pilgrimage there in June 1919, and after his return to Irun he recovered from a chronic limp after praying to the Christ and putting its picture to his leg. In the summer of 1931 he and his sister went several times to Ezkioga from Irun by train. On 8 September 1931 while he was saying mass, the Virgin told him to tell the vicar general that it was she who was appearing at Ezkioga, that she wanted a church built there, and that a miracle would take place soon. Aguirre went to Vitoria the next day but was unable to see the vicar general. In May 1933 Evarista Galdós had visions in Aguirre's house which convinced him to take down her messages for Padre Burguera.[16]

On 3 August 1919 Francisco Aguirre led another pilgrimage to Limpias. Diario Montañés, 5 August 1919 and 11 October 1919; see also Leopoldo Trenor, ¿Qué Pasa en Limpias? (Valencia: Tipografía Moderna, 1920), 293-295; for Evarista, B 308-312, 726, 739-740.

Gregorio Aracama Aguirre (b. 1884), the pastor of Albiztur, was Francisco Aguirre's cousin. At the start of the visions Aracama's nephew, Juan José Aracama Ozcoidi (b. 1909), was a seminarian. In 1933 he became curate of Urrestilla, where he believed in and assisted the seer Rosario Gurruchaga. Two other believing priests from Zegama, Doroteo Irízar Garralda (b. 1875), director of the Ave María School in Bilbao, and Isidro Ormazábal Lasa (b. 1889), parish priest of Orendain, saw and were convinced by Ramona's bloodletting.[17]

J. J. Aracama spent a month with his uncle at the height of the Albiztur visions in the summer of 1932; A, 31 July 1932, p. 3. For Irízar: B 316; R 19, 74-75; Echeguren to Laburu, Vitoria, 20 January 1932; and López de Lerena to Echeguren, 21 December 1932, private collection. For Ormazábal: B 316; R 18, 71; Echeguren to Rigné, 22 December 1932, private collection.

Soledad de la Torre and the Priest-Children

Several of these priests from Zegama were prestigious older rectors. Some had had experience with a local mystic prior to the events at Ezkioga. For in the mountains bordering Navarra and Gipuzkoa an extraordinary woman held influence over diocesan priests. She was Soledad de la Torre Ricaurte (1885–1933), the founder in Betelu (Navarra) of the Missionary Sisters of the Holy Eucharist and its ancillary movement, La Obra de los Sacerdotes Niños, the Society of Priests as Children. Like the visions at Ezkioga, La Madre Soledad has been expunged from history. Much like Magdalena Aulina, she encroached on male territory, extending the time-honored role of conventual mystic consultant to include overt tutelage of priests.

My first clue to her role was a Basque-baiting pamphlet by the priest Juan Tusquets. In February 1937, soon after San Sebastián had been taken by Franco's troops and Ezkioga believers imprisoned there, Tusquets delivered a lecture entitled "Freemasonry and Separatism." In his talk he referred in passing to "meetings of a spiritist nature in order to mislead and discredit the Catholic faith, like those of Ezquioga and Betelu, organized by the Basque Nationalists and visited by groups of Catalans." To him such meetings were part of a general decline in moral order, manifest as well in the Masons, the Rotary Club, and Jehovah's Witnesses.[18]

Tusquets, Masonería, 65-66 (thirty thousand copies were printed).

In Betelu and Pamplona I learned about Madre Soledad and why some clergy would have thought her subversive. Born in Colombia into a well-to-do family, at age thirty Soledad was moved to go to Spain, where she arrived in 1915 a kind

of missionary in reverse, from New World to Old and from women to men. She had been encouraged by her Jesuit confessor, and through him other Jesuits arranged for her to use a large house in Betelu. Betelu was a prosperous Navarrese village that like Ormaiztegi and Banyoles was a genteel summer resort. She eventually obtained permission from the Augustinian bishop of Pamplona, José López y Mendoza, to found her missionary order; the bishop in turn obtained Benedict XV's oral permission.[19]

See Soledad del Santísimo Sacramento [Soledad de la Torre], "Respuesta al Cuestionario [del Obispo de Pamplona]" (hereafter Cuestionario), Betelu, 15 December 1928, 8 pages, handwritten, ADP, Betelu. Antonio Matute of Durango ceded the house to her in 1922 on the condition that her order be canonically approved. For the papal permission see Presbítero, LC, 27 December 1933.

Madre Soledad brought two women from Bogotá and found others locally to be missionaries. She recruited other women as lay auxiliaries. Her aims were "to restore an evangelical life, glorify the humanity of Christ, and popularize the Eucharist that the Lord wants for the sanctification of souls" (in the house in Betelu the Eucharist was always exposed), but in particular she sought "to sanctify priests." Several associations to sanctify clergy had been founded from 1850 on, and in 1908 Pius X had specifically called for more such associations. Madre Soledad's innovation was to work toward this goal through an order of women.[20]

Torre, Constituciones, 3 (in ADP, Betelu); A. Brou, "Associations pour la sanctification du clergé," DS 1 (1937), cols. 1038-1045.

In Betelu she set up a school for the children of the rural elite and she offered adult literacy classes on Sundays for servants and country folk. According to women who attended her school, she was quick, good-hearted, and holy. "She had something special, a gift; she solved your problem as if she was a confessor." Betelu is in a Basque-speaking area, and although all the teaching was in Spanish, she diligently acquired Basque. Villagers remembered that she subsisted on fruit and milk.[21]

Lidia Salomé, María Salomé, and Juanita Lazcano, Betelu, 7 June 1984.

Madre Soledad gathered around her a number of priests who supported her order, and she created for them an association based on the concept of childlike innocence. She published its rules in 1920. At its head was an "Older Brother" and a governing council named by the bishop. The diocesan examiners who approved the rules remarked on the novelty of her idea, noting that the priests who joined would lead a kind of monastic life while in the world.[22]

Examination by Dr. Bienvenido Solabre and Lic. Nestor Zubeldia, Pamplona, 11 May 1920, in Torre, Constituciones, 46.

According to her manual, El Libro de las Casitas (The Book of the Playhouses, or Dollhouses), printed in 1921, the Sacerdotes Niños were supposed to be as open and as generous as very young boys. In the manual she uses diminutives in speaking to the priests and refers to supernatural beings or sentiments as if they were characters in children's books, like Da. Pánfaga (Mrs. Bread-eater). The Niños had to flagellate themselves six days a week and do other simple exercises:Stay five minutes in a little corner of your room, very still, without moving, and as if you have in your arms the baby Jesus, and kiss it five times….

Imagine that the Virgin arrives, takes the little boy by the hand, and takes him to a garden; there he enjoys seeing the most beautiful flowers (the virtues of the Virgin). Noticing that he wants them, she picks him some, makes him a bouquet, and gives them to him. Do this for five minutes.

For special penances she prescribed praying with arms outstretched, lying prostrate on the floor, eating only half a dessert and offering the rest to the child Jesus, contemplating the stations of the cross, writing the Lord a letter about one's dominant passion and then burning it, "speaking for three minutes with the Virgin in child talk," offering a bouquet of "posies" to Jesus, or visiting for five minutes the Lord in his playhouse and speaking to him in child talk.[23]

Torre, Libro de las casitas, 274-276.

In all Madre Soledad's work she applied the spirituality of female contemplatives to adult males living in the world. But implicit in this program was the priests' personal belief in her spirituality, since in the role of little boys they accepted her as a kind of mother. A prerequisite for joining the association was "to destroy oneself, renouncing in a certain way one's own personality and abandoning oneself totally in the hands of God." A discipline of puerility may have been particularly attractive for rural Basque and Navarrese clergy as a kind of relief from their inordinate social and political power. We glimpse this power in the rare republican newspaper reports from these villages, which refer obliquely to the excessive influence of the jauntxos (literally señoritos, but figuratively "honchos") in all aspects of daily life. Humility in Madre Soledad's association balanced a heavy diet of daily authority.[24]

Torre, Constituciones, 6; for priest-sons and spiritual mothers, Ciammitti, "One Saint Less"; for jauntxos, "Lecumberri" in VG 1932 on 15 and 31 January, 11 February, 23 and 31 March, 15 April, 19 July, and 17 November; see also complaints about Betelu's priest, Fermín Lasarte, answered in "Desde Betelu," PV, 1 July 1933, p. 8.

What bishop approved such a constitution? At the end of a long career, at the age of seventy-two López y Mendoza was just then firmly suppressing all public reference to the miraculous Christ of Piedramillera. But by the same token he very much had a mind of his own. Like other bishops of his time, he took refuge in convents when he needed a break, in particular with the Augustinian nuns of Aldaz, ten kilometers from Betelu. He was also interested in the theme of holy childhood. In 1919 he exhorted each parish to take up collections and enroll children in the missionary club, Obra de la Santa Infancia. Madre Soledad's school and literacy program would have appealed to his sympathies for Catholic social action as well.[25]

Rodríguez de Prada, Visiones; BOEP, 1919, pp. 68-71. For the Obra in the diocese of Vitoria: Perea, El Modelo, 2:1005-1008.

From the diocese of Navarra Madre Soledad's most important recruits were two cathedral canons, Bienvenido Solabre and Nestor Zubeldia; they served as the diocesan examiners for the rules. From 1922 to 1924 Zubeldia was rector of the diocesan seminary. There he hung maxims of Madre Soledad on the walls, exposing entire cohorts of priests to the Niño idea. Other adherents included priests in the neighboring villages of Almándoz, Errazkin, Betelu, and Gaintza and a few from as far away as Tudela, Granada, and La Coruña.[26]

For Zubeldia: Pazos, Clero navarro, 314 n. 40; Goñi, DHEE, 4:2813-2814, and Z. M., Don Nestor Zubeldia.

Betelu is just five kilometers from the border of Gipuzkoa, and some Gipuzkoan priests became Niños. They included Gregorio Aracama of Albiztur, possibly some priests from Zegama, and Juan Sesé of Tolosa. Manuel Aranzabe y Ormachea, a wealthy priest from Lizartza, was a strong supporter; the nuns cared for his sister, who was mentally ill.

The priest-children considered that Madre Soledad had the gift of reading their consciences, and she gave them sermonlike lectures. In the mid-1920s, when

the Gipuzkoan priest Pío Montoya was a seminarian, Juan Sesé took him, his sister, and their father to see her. They were favorably impressed and remember her as a small woman, very modest, who spoke much and brilliantly and referred to human pride as "Señora Chatarra [Mrs. Junk]." The townspeople of Betelu understood that Francis Xavier appeared to her in ecstasy and recall that the village was sometimes crowded with visitors.[27]

Pío and Angeles Montoya, San Sebastín, 9 February 1986; Salomé et al., Betelu, see n. 21 above.

By 1919 her fame as a "saint" had spread widely, for several bishops had inquired about her to the nuncio, and he wrote López y Mendoza. It may have been then that she and the bishop of Pamplona decided that the wisest course was to institute her order for nuns and her association for priests as diocesan congregations. This the bishop did on 5 March 1920, pending Vatican approval. López y Mendoza protected her until he died in 1923. His successor in Pamplona, Mateo Múgica, did not like what he heard. The unusual submission of male priests to a female had led to unfounded rumors of sexual license.[28]

Torre, Constituciones, 45, 48; Carlos Juaristi, Pamplona, 17 June 1984.

The same rumors later circulated about the group of Magdalena Aulina, which also associated males and females.The Holy Office condemned the Book of the Playhouses and the rules of the institute and dissolved the association of priests as children altogether. On 23 February 1925, following the orders of the Vatican Congregation of Religious, Múgica severely restricted the freedom and power of the women in Betelu. The erstwhile Misionarias were to be strictly contemplative Adoratrices who renewed their vows annually. They could found no more houses. Their goals could have nothing to do with clergy, "only the sanctification of souls in general," and the Niños could visit them no longer. The auxiliary laywomen could continue provisionally, but only if they had no contact with the priests and were not members of the convent.[29]

Mateo Múgica y Urrestarazu, "Nos el Dr....cumpliendo rendida y literalmente ...," Pamplona, 23 February 1925, 3 pages, handwritten, ADP, Betelu. The decree of the Congregation of Religious seems to have been on 4 February 1923. BOEP, 13 June 1925, p. 328, carries condemnation of the movement by the Holy Office dated 20 February 1924 in a letter sent by Card. Merry del Val to Múgica, 1 June 1925; see Pazos, Clero navarro, 314.

Madre Soledad immediately went to Rome. There, accompanied by the superior general of the Augustinian order, Eustasio Esteban, she appealed to Cardinal Laurenti, the prefect of the Congregation of Religious. She protested that "if the Holy Church does not permit us to have as our object the greater sanctification of priests, we humbly request our secularization." She told him she would appeal to the pope if necessary to avoid being cloistered. According to her, Cardinal Laurenti allowed her to continue "the practices of the past"—I assume she meant her contact with priests—as long as the rules nowhere mentioned the sanctification of clergy.

Not surprisingly, when Madre Soledad returned to Navarra Mateo Múgica rejected this Mediterranean solution of doing one thing and saying another, so the entire community petitioned the Congregation of Religious to return to secular life. By 1928, when Múgica was transferred to Vitoria, Rome had not replied and the community remained in a kind of limbo. In her explanation of the situation to the new bishop, Tomás Muniz y Pablos, Madre Soledad listed nine professed nuns, two novices, and a postulant.[30]

Cuestionario, 4-6. Postulant: Felicitas Aranzabe y Ormaechea, age 30, Lizartza (Gipuzkoa).

Novices who had professed in private: Juana Arocena y Iturralde, age 29, Almándoz (Navarra); Juana María Ezcurdia Marticorena, 36, Errazkin (Navarra).

Professed nuns: María Solabre y Lazcano, age 27, Los Arcos (Navarra); Rosa Arrizubieta y Otamendi, 32, Uztegi (Navarra); Lorenza Pellejero y Goicoechea, 33, Gaintza (Navarra); Juana Balda y Ezcurdia, 35, Gaintza (Navarra); Beatriz Celaya y Gurruchaga, 38, Zarautz (Gipuzkoa); Juana Agorreta y Ibarrola, 40, Zilbeti (Navarra); María Luisa Cediel y Angulo, 42, Bogotá; Angelina Rozo y Alarcón, 60, Bogotá; Soledad de la Torre y Ricaurte, 43, Bogotá.

Gaintza, Errazkin, and Uztegi are small villages next to Betelu and Lizartza is the first town in Gipuzkoa on the road from Betelu. Almándoz is also in the same zone. The other places are within a sixty-kilometer radius.

In spite of Muniz y Pablos's visit in 1929, neither he nor the Vatican acted; the nuns remained contemplative. Theoretically at least, their priest followers could not maintain any contact with them, although the auxiliaries continued to operate the school. In fact, given Cardinal Laurenti's verbal consent to Soledad's mission, she continued to have contact, direct or indirect, with the priests. Women who lived near the convent and who attended the school remembered that even after the nuns were cloistered, Soledad de la Torre addressed the priests from behind bars on Thursdays. We may assume that contact with laywomen was even easier.[31]

Madre Soledad did not convey her enthusiasm for the Ezkioga visions to the villagers. The Betelu women I spoke to had been to Ezkioga only once, when a woman from Pamplona, a summer resident, hired two buses for the townspeople: Lidia Salomé, María Salomé, and Juanita Lazcano, Betelu, p. 4. I know of no visions around Betelu.

In July 1931 Madre Soledad and the nuns were living under this ambiguous, provisional regime. Gregorio Aracama of Albiztur sent two of his sisters to ask if he should go to Ezkioga. Her response was, "Go to Ezkioga and pray a lot." This attitude confirmed his interest, that of his parishioners, and, we may presume, that of other Niños with whom he was in contact. And the fervor and mystical enthusiasm of the first years of her movement must have made other people in the area receptive to the Ezkioga visions.[32]

Juan Celaya, Albiztur, 6 June 1984, pp. 29, 43. Some Navarrese followers took an interest in the visions in the Barranca. The Iraneta group learned about Madre Soledad from her last confessor, Fermín Lasarte, whose brother and sister-in-law often went to watch Luis Irurzun. Other priests who had been followers of Madre Soledad also took an interest in Luis (Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, pp. 3-4).

Soledad de la Torre died on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December 1933. Her believers considered the date a portent, but thereafter the convent gradually disintegrated.[33]

I verified the date of death in the parish register as December 8, for some villagers claimed that she died on Good Friday at 3 P.M. Some nuns chose to leave the convent, for in November 1935 only five were left, two of them infirm (letter from Sor María Luisa de la Cruz, Beatriz de Jesús María y José, and Rosa de Santa Ana to the bishop of Pamplona, Betelu, 24 November 1935, typewritten, 2 pages, ADP, Betelu).

La Constancia published a front-page obituary signed "A Priest," and three weeks after Madre Soledad died, two women from Segura presented the article to Conchita Mateos in vision. Conchita murmured, "Now you are better off, but your daughters must be sad," and said she saw the nun with a white habit and a crown of stars next to the Virgin.[34]Presbítero, LC, 27 December 1933; J. B. Ayerbe, "Visión de Conchita Mateos, en su casa de Beasain, el 30 de Dicbre, 1933," 3 pages, typewritten, signed by Conchita Mateos and J. B. Ayerbe, AC 302.

Similarly, Esperanza Aranda claimed that when she held up a picture of Madre Soledad during a vision in 1949, Our Lady said the nun was then a saint in the choir of virgins. Esperanza had experienced more than her share of ostracism and ridicule and asked the Virgin how Madre Soledad could have been so slandered in her lifetime. Aranda said the Virgin replied, "Do not place your trust in men; they are like a hollow reed that even the wind can break." Juan Bautista Ayerbe, who recorded the vision, noted that Soledad de la Torre's "marvelous writings have now been collected to be sent to Rome."[35]J. B. Ayerbe, "Interesantes revelaciones sobre varias almas, 8 Abril 1949, Festividad de los Dolores," 2 pages, typewritten, AC 74.

Female Religious

Madre Soledad's attempt to assume formal authority over parish priests was daring and ultimately fatal for her order, but the authority itself was ancient. Priestly consulting with female mystics has a long history in Mediterranean Catholicism, and indeed in pre-Christian times, as at Delphi and Dodona.[36]

For Catholic examples, Selke, El Santo Oficio; Kagan, Lucrecia's Dreams; Zarri, Finzione; Zarri, Le Sante Vive, 103; and Bilinkoff, "Confessors and Penitents."

When the Ezkioga visions began, it was natural to compare what the lay seers were saying with what the "professional" nun seers like Madre Soledad said, for convents were by design platforms for contact with God.It was easy to pin divine rumors on anonymous nuns, like the one who on her deathbed predicted prodigious events for 12 July 1931. On July 24 La Constancia cited another unnamed nun in support of Ezkioga:

An illustrious religious who occupies a high post in his order told us that a nun who leads an extraordinary life whom he knows and talks to has announced for this year great appearances of María Santísima. Would she be referring to Ezquioga?

A mimeographed letter that circulated among believers in 1933 referred to a nun "directed by one of the highest eminences of the church" as "a very holy soul with a very elevated spiritual life" and "a fervent devotee of the Holy Christ of Limpias and his prodigies; she is very old and burdened with crosses." In spite of the verdict against Ezkioga by the bishop of Vitoria she counseled patience and happiness, saying, "All God's works need persecution; otherwise they would not be true, and by it they gain strength."[37]

Egurza, LC, 24 July 1931; Salvador Cardús to Ayerbe, 11 October 1933; letter from nun to Cardús, 21 September 1933.

In many convents there were nuns thought to be especially spiritual. One nun in Zarautz was thought to predict deaths accurately; she was also called in when houses were bewitched. In Aldaz there was a visionary Augustinian nun who could see a picture of the Christ of Limpias respond to her prayers or feelings.[38]

For Zarautz, Petra de la Maza, 14 December 1983; for Aldaz, Rodríguez de Prada, Visiones, 27-29, 81-82, 104-106, about María de los Dolores de Jesús y Urquía, who began to record her visions in May 1932 and likely had them previously; she died 26 February 1934. See also Vergel Augustinano, October 1934 and 1935, p. 478.

In female orders male religious already had mystical guides when they needed them. The tradition of consulting holy people governed the response of male and female religious to the visions at Ezkioga. They did not question whether such visions were possible but rather how well the visions fit the criteria with which they judged their own mystics.The census of December 1930 found 5,450 female and 2,251 male religious in the Basque Country, about half of them in Gipuzkoa. The number in the province had increased greatly when religious took refuge there after the separation of church and state in France in 1905. The number of nuns continued to increase between 1910 and 1930. Since the beginning of the century Gipuzkoa, Alava, and Navarra had been first, second, and third among Spanish provinces in the number of religious as a percentage of total inhabitants.[39]

From Anuario estadístico de España, 1933, p. 664. Religious living in the Basque Country on 31 December 1930:

|

Total religious per 10,000 inhabitants and nationwide rank:

|

About one in four houses of female religious in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia were contemplative. This proportion declined as the active orders, particularly in San Sebastián and Bilbao, took on more tasks in hospitals, social services, and schools.[40]

Anuario estadístico de España, 1933, p. 667; Guía diocesana, 1931; and Anuario eclesiastico, 1919.

Male and female religious helped to ease the dislocation caused by an economy that was shifting from agriculture to industry. Since many of the active orders were French, they kept the Basques abreast of the latest developments in French piety, including the great apparitions.Religious orders establish a rule, a way of life, and a set of devotions that make each order an extended family different from other orders. Some orders, like the Capuchins, regularly transferred members from house to house, creating a certain homogeneity within the order in each province. Cloistered religious

might spend all their adult lives in the same small group; these houses, rather than the orders they belonged to, were the group that determined belief or disbelief in the visions. Orders varied widely in the source of their members, whether rural or urban, wealthy or peasant; these factors could predispose them in favor of or against the messages of the largely peasant seers. All of the orders in July 1931 were uneasy in a nation that had turned against its religious.

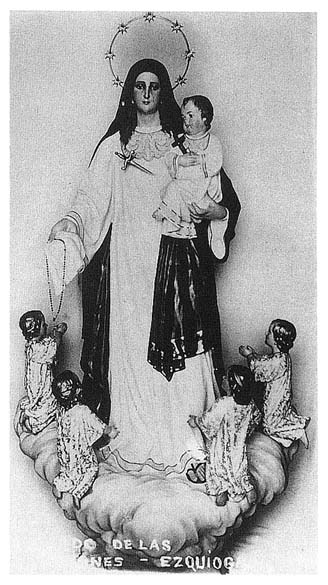

The orders most active in the vicinity of Ezkioga had propagated many of the devotions that showed up in the apparitions, thereby laying the groundwork for the public's acceptance of the messages. Ezkioga seers saw religious in their visions and attempted to win over religious houses to the cause. The laity watched closely for the reactions of the religious to the apparitions.

Cloistered religious were a major, long-term constituency for the visionaries, especially the female seers. In 1930 there were at least thirty convents of contemplative nuns in the Basque Country, particularly of Franciscans of various types, Augustinians, and Carmelites. And Basque women entered convents in the rest of Spain as well. These little societies developed their own criteria on matters supernatural; at times they felt little bound by the church hierarchy. Nuns might be enclosed, but they could write the seers with questions and requests for the divine. Convents of believers transmitted news of Ezkioga to their clerical and lay friends and benefactors. Some houses in Pamplona were intensely interested; Tomás Imaz, the San Sebastián broker, took seers to the Cistercian convent at Narvaja in Alava for visions, and in Oñati "those inside the convent knew more about the visions than those outside."[41]

For Oñati: Petra de la Maza, Zarautz, 14 December 1983, p. 1.

Maria Maddalena Marcucci

Passionist nuns shared the key devotions of the visions. According to their rule, the Sorrowing Mother was the heavenly superior of all their convents. At Ezkioga the Passion as experienced by the Virgin was the dominant visual metaphor.

The most prominent Passionist nun in Spain was the Italian Maria Giuseppina Teresa Marcucci, in religion known as Maria Maddalena de Gesú Sacramentato. From 1928 to 1935 she was superior of the house in Bilbao-Deusto. She had known Gemma Galgani of Lucca by sight, as she herself was from a village near Lucca. Many thought Maria Maddalena was a holy woman, and she herself had revelations and visions. Starting in 1928 her writings were published by her director, Juan González Arintero, the Dominican expert on spirituality, and his successors in the magazines Vida Sobrenatural . In her letters and autobiography we see a woman in close, obedient contact with Dominican guides.

In a letter dated 15 October 1931 Maria Maddalena referred to the visions at Ezkioga: "The apparitions of the Most Holy Virgin of the Sorrows seem intended to show us the sufferings and anguish of the Heart of Jesus. Some souls

believe they have seen him as the Nazarene, carrying the cross." Marcucci attributed Christ's anguish to Spain's rejection of him and worried about what she could do to protect her community.[42]

Marcucci (1888-1960), En la cima, 186.

Marcucci met Evarista Galdós in early 1932 and afterward wrote her from Deusto with requests to the Virgin to intensify the Passionist vocations of the community, to cure a sick nun, and to take Marcucci herself directly to heaven when she died. Her initial contact with Evarista may have come through male Passionists in Gabiria or Irun. But it could also have come by way of Magdalena Aulina. In February of 1933 Salvador Cardús understood that Aulina was directing Marcucci spiritually. Marcucci came from the same pious environment as Gemma Galgani and knew about the surprising supernatural events that Gemma described. It was fitting that she should believe both the visions of Ezkioga and Magdalena Aulina.[43]

Marcucci to Evarista Galdós, Bilbao-Deusto, 20 March 1932, private collection (text in appendix). For Cardús, SC E 534. Aulina told Cardús on 6 February 1933 that Marcucci was a saint who had had a vision of Gabriele dell'Addolorata in which the saint introduced her to Gemma Galgani.

This independent abbess was accustomed to receiving spiritual help from other women as well as from male guides, just as she gave such help to women in her convents and readers of her writings. In her letters Marcucci refers to holy women in the different convents in which she lives and others in her order whose inspirations, revelations, or visions guided her and others in the order. Women and men who felt as she did that they received particular communications from the divine formed a community of mutual support. A permanent, hidden, conventual mystical network thus underlay the more spectacular lay visions known as apparitions.[44]

See, for instance, Marcucci, En la cima, 288, 335, 348.

The Franciscan nuns of Santa Isabel in Mondragón were firm believers in Ezkioga. Magdalena Aulina was said to have served as spiritual director to their superior, who had in the house a saintly lay sister. The priest Baudilio Sedano de la Peña encouraged belief in the visions among the same nuns in Valladolid and brought Cruz Lete to speak to them. One nun had visions of her own, and the house was divided for decades between those who believed in her and Ezkioga and those who did not. She warned the latter that they would go to hell.[45]

For Mondragón, SC E 534 (6 February 1933). Aulina visited the Mondragón convent 15 October 1932, SC E 481/22; in December 1933 the nuns still believed, ARB 177-178. For Valladolid: Sedano de la Peña, Barcelona, 5 August 1969, p. 15.

The seers Pilar Ciordia, Gloria Viñals, and others attempted to sway houses by having visions inside them, a kind of home delivery of grace. One young woman reported that the Virgin told her, "I want you to be the tutelary angels of the religious communities. Get them to pray, because many, not all, need it." But it was not always easy to convince those whose chaplains or spiritual guides did not believe. Evarista Galdós is said to have converted one convent when she discovered in a vision that one of the sisters had a bad foot. And Benita Aguirre said she had private messages from the Virgin for certain cloistered religious.

about internal practices that made them marvel, such as that [the Virgin] was very happy with a rosary that they prayed secretly as it is prayed at Ezkioga, or that they should not stop praying the three Hail Marys before

the Litany, or that, as in former times, they leave the keys with an image of the Virgin, for she would protect them.

In Pamplona a girl from Izurdiaga saw the Virgin threaten a community of nuns for not believing. When the tide turned against the visions, clergy made every effort to "deconvert" believing houses. Padre Burguera complained of "instances of communities where a Father cast the spiritual exercises he was leading so that when he finished, the religious ended up not believing anything [about Ezkioga]."[46]

For tutelary angels, the servant María Nieves Mayoral, 13 October 1932, in J. B. Ayerbe, "Mensajes divinos," n.p., dittoed, ca. 1935, 14 pages, p. 9, AC 6; for Evarista, 21 October 1932, but order, convent, and place are unidentified in B 721; for Viñals, R 50-51; for Benita, J. B. Ayerbe, "Maravillosas apariciones," AC 1, p. 2; Izurdiaga girl, 11 September 1932, in a private house, B 167-168; for deconversion, B 479.

Several Ezkioga seers eventually became cloistered nuns. One of the small dramas in the vision dialogues was whether and when the seers, including the girl from Ataun, Ramona Olazábal, and Benita Aguirre, would enter convents. In January 1942 Conchita Mateos claimed she received her vocation after seeing a nun who had recently died in a Franciscan convent in a town of Castile. The spirit nun dictated a letter for Conchita to send to the mother superior saying that Conchita had her same playful nature and would take her place. This unusual reference letter was successful, and Conchita and twelve other girls from five families of believers entered the convent, where she continued to have visions.[47]

For Conchita see J. B. Ayerbe, "18 Enero, 1942, Aparición de la gloriosa religiosa María Angeles, muerta en octubre de 1941 en el convento de ...," half-page, typewritten, AC 353; believers were there from Urnieta, Bergara, Anoeta, and Azkoitia (ARB 171). Of the 9 girls who were seers in Mendigorría in 1931, 4 became nuns—2 of them Daughters of Charity, 1 a Dominican, and 1 a Redemptorist Oblate. María Recalde wanted to be a Carmelite nun when she was nineteen (B 598 and L. Jayo). The Izurdiaga girls wanted to be nuns and the boy a priest. Of the 21 girls and 21 boys in the Santa Lucía school in 1932, 1 girl became a Mercedarian, 1 boy a Franciscan and another a parish priest, an overall rate of 1 in 14, not unusual for the Goiherri and lower than for parts of Navarra. Given such rates, 8 of the 120 children and youths who were seers would have taken vows in any case.

The order of active female religious with the most communities in the diocese, over sixty houses in 1930, was the first female active institute, the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. Its members, who took temporary vows renewed every three years, were in charge of the old-age home and the parish schools in Urretxu as well as hospitals in Tolosa and Beasain. In the province of Gipuzkoa alone they staffed at least thirty institutions.[48]

The first woman from Ataun joined the Daughters of Charity in 1852. In 1931 seventeen from the town were in the order, but only one joined after 1915: Arín, Clero de Atáun, 226-237. Their associated male order, the Vincentians, had no houses in Gipuzkoa or Bizkaia. Mercedarian Sisters of Charity attracted to their novitiate in Zumarraga the kind of girls who had earlier joined the Daughters of Charity. The Mercedarian Sisters had eight houses in Gipuzkoa, but despite their close relation with Antonio Amundarain I do not know of any involvement in the Ezkioga visions. Amundarain, Vida congregación mercedarias, 187-199, 317-332; Arín, Clero de Atáun, 238-243.

Given the large number of active women religious in the region, they seem remarkably little involved in the visions. Their activity and freedom to circulate, however, gave them access to moments and places where the supernatural and the "world" coincided. In the fall of 1931 a Daughter of Charity who was a nurse in the Tolosa hospital was present when doctors diagnosed Marcelina Eraso's sister as having an incurable cancer. The nurse asked Marcelina to ask the Virgin to intercede and later signed a document describing the cure. One seer, Esperanza Aranda, worked in San Sebastián in La Gota de Leche, an establishment run by the Daughters of Charity which provided milk for babies and pregnant mothers. Aranda held some of her visions with nuns present and once pointed out in a vision a Daughter of Charity who had just died in Urretxu.[49]

Photos in Degrelle, Soirées, 21 September 1933; cure dated Tolosa, 22 July 1933, signed by, among others, María Recalde's sister-in-law, Victoria Jayo (B 736-737), who was at Ezkioga with another nun in May 1932 (ARB 143). Aranda vision, B 710, apparently 8 December 1932. A children's magazine distributed by the institute printed the fullest report of the visions in Mendigorría: Orzanco, "Nuevas apariciones." And in May 1932 these Sisters of Charity in Madrid were among the first to witness what seemed to be a bleeding statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The news reached Ezkioga believers through the letters of a "Sor Benigna." See J. B. Ayerbe's circular "Cartas de las H. H. de la Caridad del paseo del Cisne en Madrid" (AC 402), which includes letters sent in May and June 1932 about an image in the house of Mercedes Ruíz that the sisters went to see in pairs; see also Rivera, "Sagrado Corazón."

The women in the Daughters of Charity led lives of a certain independence. An example is Sor Antonia Garayalde Mendizábal, who died at age seventy-eight in Beasain in 1932. Born in nearby Altzo, she entered the order in 1849 and worked in a home for abandoned children in Córdoba before going to Beasain in 1896 to head the clinic. Garayalde visited the sick in their homes and cared single-handed for the ill of the nearby village of Garín when it was struck with typhoid fever in 1896. She also set up a nursery school, which at one point

had three hundred children, promoted the cult of souls in purgatory, took care of the cemetery, and prepared the corpse of virtually every person who died in Beasain. Sisters like Garayalde took on the work formerly done by women for their extended kin; these sisters were especially needed in factory towns like Beasain where immigrants had left their grandmothers, aunts, and sisters behind.[50]

Alumnos, "Desde Beasain," PV, 26 March 1932.

In Elorrio the mother superior of the community at the old-age home and clinic was a faith healer. When the doctor's guild complained to the bishop and he passed the complaint on to the Spanish headquarters of the order in Madrid, the order tried to transfer the nun, but the people of Elorrio protested so much that the order backed down. The hands-on miracles of this nun, however, were quite different from the holiness of the saint-as-victim, like Gemma Galgani, which the seers of Ezkioga came to embrace. Sor Antonia Garayalde touched the bodies of the living and the dead in Beasain; the Ezkioga seers were intermediaries with the spirits in the other world.[51]

Dossier in ADV Denuncias with letters to Bishop Múgica from the president of the Colegio de Médicos de Vizcaya, Bilbao, 15 August and 13 September 1935, and Sor Sofía Pulpillo, Asistenta, Madrid, 25 August 1935.

We can see the contrast in contemplative and active stances as reflected in religious devotions. In the first years of the century the Daughters of Charity began to circulate little images of the Miraculous Mary. Groups of thirty households, known as "choirs," pooled money to buy them and passed these boxed images of a powerful Mary daily from one house to another. The people would always light a candle or oil lamp before the image, and the boxes had a slot for alms for masses for deceased members, the costs of the Association of the Miraculous Medal, or the local poor. Images like these of different devotions circulated (and still do) throughout Catholic Europe. The Passionists circulated ones of their saints, as did the Carmelites the Infant Jesus of Prague, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, and Thérèse de Lisieux. Some orders supplied printed prayers with the image. In this period the Miraculous Mary was fresh and exciting. In Beasain Sor Antonia established no less than twenty-four coros covering 720 families. In some places the devotion took on a life of its own.[52]

This devotion spread to Oiartzun in 1920 from Rentería and Irun without the involvement of religious. Within three years the images linked 480 families in Oiartzun: Lecuona, AEF, 1924, pp. 21-22.

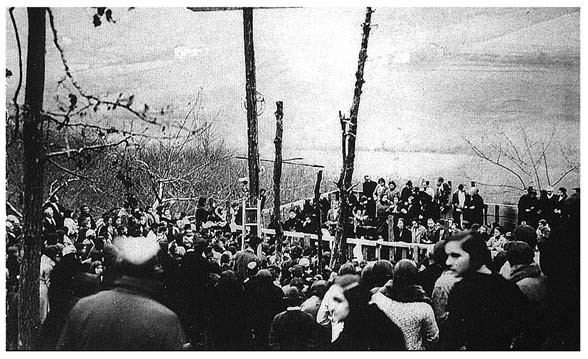

Not surprisingly, from the start at Ezkioga this Mary was in a sort of competition with La Dolorosa as the preeminent divine figure. The Beasain chauffeur Ignacio Aguado saw the Miraculous Mary on July 8, and for a while others saw her as well. A Daughter of Charity was present when the Bilbao engraver Jesús Elcoro saw La Milagrosa on July 30.

[Elcoro] tries to explain the stance that the Virgin took in her appearance, and begins to hold out his arms the way the image of the Miraculous Mary does. The crowded conditions do not permit this, and a Sister of Charity says, with extraordinary excitement, "The Miraculous Mary! It's the Miraculous Mary! Isn't it true? Make room, let him put his arms the way he has seen the sweet Virgin."

And as if conjured by the outburst of faith of the little nun, the youth has an apparition again. The nun says to him, "Tell the Virgin that we

Cover of home visit manual of the Miraculous

Mary, published by Vincentians in Madrid, ca. 1926

love her a lot, and that we come to make up for the many offenses against her in Spain."[53]

Txibirisko, PV, 10 July 1931; "De Ormaíztegui," PV, 17 July 1931, p. 8; PV, 25 July 1931, p. 2. The girls of Albiztur especially tended to see La Milagrosa, LC, 28 July 1931, p. 5, and A, 23 August 1931, p. 2. Quote from Pepe Miguel, PV, 31 July 1931, p. 4.

Eventually La Dolorosa emerged as the dominant symbol of the visions, a symbol oriented more toward contrition and penance. It was more suited to contemplative and Passion-oriented orders, like the Passionists, Capuchins, Carmelites, and Reparadoras. La Milagrosa, like Our Lady of Lourdes and the Sacred Heart of Jesus, was a more active, optimistic image appropriate for orders involved in good works or healing.

Male Religious

Nuns might be believers or disbelievers, supplicants or sister seers of the visionaries. Male religious could also be spiritual directors to the seers or expert examiners of visions. Some clergymen, like Padre Burguera himself, thus had a professional as well as a personal interest in the apparitions.

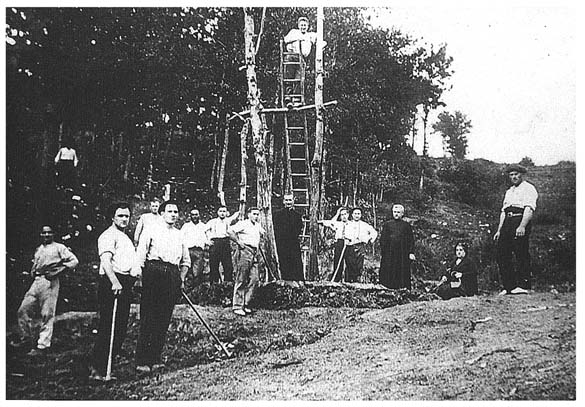

From their junior seminary just over the hill in Gabiria, Passionist professors and students could hear the hymn singing and prayers at Ezkioga and they were inevitably embroiled. The Passionist order, founded in Italy in the eighteenth century, had established its first house in Spain in Bilbao in 1880. In 1931 the north was still its stronghold. In the first weeks of general excitement at Ezkioga the Passionists were "almost all in favor." Some individuals converted at Ezkioga went to confess at the Passionist seminary. On 1 August 1931 two fathers were said to have seen one of Patxi's "levitations." The seers tapped into Passionist interests with visions of the Passionist Gabriele dell'Addolorata and the would-be Passionist, Gemma Galgani. The Ezkioga farmer Ignacio Galdós had a vision of a Passionist preaching to more than four thousand people; in the vision a star fell from the sky until it was by the side of the preacher, who distributed parts among the crowd. Two-thirds of the people disappeared into the darkness, while the remainder, brilliantly lit, fell to their knees; the Passionist blessed them with his cross.[54]

For Gabiria, Antonio M. Artola with Joseba Zulaika, Bilbao-Deusto, September 1982, p. 4. For life at the school, Ecos de San Felicísmo, 1932, pp. 197-199, 230-233, and Artola, Martín Elorza, 16-31. Initial Passionist enthusiasm: Basilio Iraola Zabala (b. 1908), Irun, 17 August 1982, p. 1, who said his first mass in Gabiria in 1931, and Dositeo Alday, Ramón Oyarzabal, and Rafael Beloqui, Urretxu, 15 August 1982; confessions, B 51; for Patxi's "levitations," Elías, CC, 21 August 1931; for Gabriele dell'Addolorata, ARB 33-34; for I. Galdós, B 755.

The initial enthusiasm of the Passionists is understandable given their devotional aesthetic. Passionists had accompanied their sodalities to the visions of the Christ in Anguish at Limpias, a kind of throwback to the Baroque devotions of Holy Week that declined in the north in the nineteenth century. This kind of devotion has revived in part because of parish missions. In their missions the Passionists set up outdoor stages. A parish priest in Navarra commented on their "special method":

preaching from a stage or platform in an appropriate place and giving a brief talk on one aspect of the Passion of Our Saviour after the principal sermons; they did the apparition or entrance of the Most Holy Virgin, the descent from the Cross, and the procession of the holy burial.

The visions at Ezkioga also had as their central metaphor the Passions of Christ and the Virgin, and Patxi's similar stages at Ezkioga served the same purpose, the provocation of remorse by a kind of sacred theater. The order's magazine, El Pasionario , carried almost no news of the apparitions, but issues published before the visions started included depictions of the Passion in poses much like those later struck by the Ezkioga seers and descriptions of the mystic life of the German stigmatic Thérèse Neumann. The magazine was read in the villages and towns around Ezkioga.[55]

For mission, Venancio Jáuregui, "En Goizueta," BOEP, 1916, p. 154. Basilio de San Pablo, "Manifestaciones de la Pasión." Luistar was the distributor of El Pasionario in Albiztur. Another Passionist magazine, Ecos de San Felicísimo, printed a report on the visions on 1 September 1931.

After the exposé of Ramona's miracle, most of the Passionists turned against the visions. Indeed, some, like Basilio Iraola, a friend of the Ezkioga pastor, were opposed from the start. But a few remained firm in their belief. I spoke in 1982 to Brother Rafael Beloqui, who said he had been to the visions thirty-nine times, primarily because he enjoyed the praying so much. In June 1933 a certain Padre Marcelino, based in Villanañe (Alava) and Deusto, was thrown from a horse when returning from a remote village where he had celebrated mass. A rural doctor told him he was in critical condition, and after his condition worsened he said he saw the Virgin who told him he would recover. He attributed the cure to the Virgin of Ezkioga. Rumors like this and one that a Passionist had seen Gemma and San Gabriele at the site gave the believers hope that the order would be on their side.[56]

B 739-740. After the war a few Passionists still believed in the visions; see Beaga, "O locos o endemoniados."

In the first flush of enthusiasm in the summer of 1931 Franciscans, Capuchins, Claretians, and Dominicans went to the vision site and published their impressions, which varied from noncommittal to guardedly enthusiastic. And as with the Passionists, so with the other orders: after early enthusiasm for the visions they eventually followed the diocese into opposition. Only a few individuals persisted.

The Franciscans carried the most weight in Gipuzkoa, with houses in Zarautz, Oñati, and Aranzazu. The believers and friars I talked to agreed that the Franciscans came to oppose the visions strongly; believers attributed this to a fear of competition. A man in Tolosa claimed Aranzazu was the place Bishop Múgica met to plot against the visions. Another rumor had it that a Franciscan outspoken in his opposition to the visions had fallen to his death while directing the construction of the church of Our Lady of Lourdes in San Sebastián.[57]

B 301 mentions a Franciscan missionary assigned to India who was cured of gout at the shrine. For the plot see Lucas Elizalde, Tolosa, 6 June 1984, p. 2, and for the rumor see Ducrot, VU, 23 August 1933, p. 1331.

The Franciscans were from the same kinds of families as the seers and believers, so their opposition was especially hard to bear. Indeed, of all the religious I visited, it was among Franciscans at Aranzazu that I found most sympathy—not for the seers, but for the believers. When the seer Martín Ayerbe of Zegama became a religious, he joined this community.In the 1920s about thirty thousand pilgrims went to Aranzazu each year. This was a relatively small number for that period, especially compared to the crowds at Ezkioga. But Aranzazu was the major Marian shrine in the province and one to which many of the believers in Ezkioga were devoted. They recognized the apparition of the Virgin in Aranzazu as a local precedent, and when the Ezkioga site was declared out-of-bounds, some believers went to Aranzazu to meet and pray.[58]

M. Ayerbe died before becoming a friar. A seer from Zaldibia was a novice in 1952. Figures from José A. de Lizarralde, in Guridi, AEF, 1924, pp. 97-100.

In 1919 Capuchin preaching had sparked the visions in Limpias. The Capuchins had six houses in the wider vision region but none close to Ezkioga. Some of the friars involved with Limpias took an initial interest in Ezkioga, but many became convinced that the visions at Ezkioga were a plot to embarrass Catholics.

Pedro Balda, the town secretary of Iraneta, told me that he and Luis Irurzun went to Pamplona in an attempt to leave the notebooks of Luis's messages with Balda's uncle, a Capuchin. Luis went into a vision, with Balda's uncle in prayer alongside him, but as he came out of it the superior arrived and gave him a kick. Balda and Luis decamped with the notebooks and Capuchin alms-gatherers spread the word that Luis had been booted out of the house.[59]

Damaso de Gradafes at Basurto, who had taken his youth group to Limpias, took the members to Ezkioga as well, and Andrés de Palazuelo, who wrote in favor of Limpias, published an article on Ezkioga in El Mensajero Seráfico, 16 September 1931. For Ezkioga as plot Enrique de Ventosa, Salamanca, 5 May 1989, and Francisco de Bilbao, Madrid, 6 May 1989. Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, p. 16; he and Luis had first tried to leave Luis's notebooks at the Jesuit house in France, La Rochefer, but they failed. A sympathetic Capuchin, P. Bernabé, occasionally preached in the Goiherri. The Claretians had been sympathetic to the Limpias visions and printed favorable articles about Ezkioga in their national magazine, Iris de Paz. But I know of no Basque Claretian involvement.

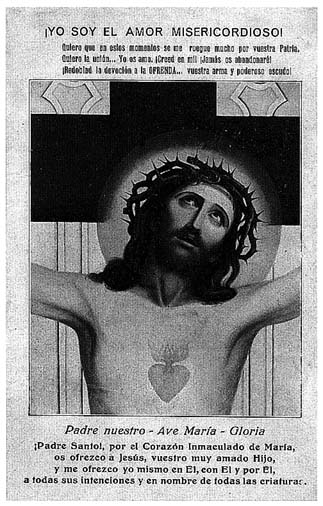

Dominicans went to Ezkioga from Montesclaros in Cantabria and nearby Bergara and reported for El Santísimo Rosario , the magazine that first publicized Fatima in Spain. But not all Dominicans were receptive. Luis Urbano, the man who single-handedly discredited the visions at Limpias and Piedramillera in 1919 and 1920, published in his magazine Rosas y Espinas the first negative article about Ezkioga written by a religious. In this period Dominicans in Salamanca, Madrid, and Pamplona had a kind of rival to Ezkioga: the divine messages relating to Amor Misericordioso, Jesus of Merciful Love, received by Marie-Thérèse Desandais (1877–1943). The abbess of a convent of Dreux-Vouvant in the Vendée, Desandais published her revelations under the pseudonym P. M. Sulamitis. González Arintero, the Dominican who published Maria Maddalena Marcucci, first came across Desandais's writings in 1922. He dedicated much of the last seven years of his life and the pages of his journal to spreading them. In the late 1920s a wealthy laywoman in Madrid, Juana Moreno de Lacasa, financed the publication of the messages in pamphlet form by the hundreds of thousands. In San Sebastián the count of Villafranca de Gaytán de Ayala persuaded a number of bishops to allow leaflets to be inserted in diocesan bulletins. And Dominicans spread the devotion with lectures and a special magazine and by installing paintings of the Merciful Christ in their house in Madrid in 1926 and in Pamplona in 1932. The Ezkioga seer Jesús Elcoro, given to seeing nuns, claimed to see Sulamitis with the Virgin.[60]

For Arintero and Merciful Love see Fariñas, "Apostol"; Suárez, Arintero, 275-309; and Staehlin, Padre Rubio, 247-251. See Gaytán de Ayala obituary in VS 40, no. 361 (January-February 1959), pp. 69-70; he gave a speech about the devotion in the Vitoria seminary in February 1932, Gymnasium, 1932, p. 124; the Sulamitis leaflets received the nihil obstat in Vitoria by March 1929. P. M. Sulamitis, España'ko Katolikoai (To Spanish Catholics), was published in Bergara with the imprimatur of Justo de Echeguren and Manuel Lecuona in 1932. For paintings, see Fariñas Windel, "Apostol," 114, and "Un Cuadro de Ciga," La Tradición Navarra, 29 December 1931, pp. 1-2. The Dominicans of Atocha in Madrid published the magazine Amor Misericordioso. For Jesús Elcoro, R 8.

The messages of Merciful Love posed fewer problems for the church than those of Ezkioga. Very little of their content was bound by time and place. They were the product of a single visionary who could be silenced at any time; they came through a respectable journalf and enjoyed ecclesiastical permission. They were not propositions to the hierarchy from the lay public, much less from poor rural children, housemaids, farmers, and workers. Inspired females could be heard only if cloistered and directed. It helped to disguise their identity. Most readers did not know that J. Pastor (Marcucci) and P. M. Sulamitis (Desandais) were women. The Merciful Love messages too were quite different from those of Ezkioga, emphasizing the mercy of God as good father, not the anger and chastisement of God offended. In 1931, when events seemed to be going against Catholics and Catholicism in Spain, the idea of a chastisement was perhaps more in line with contemporary developments. Merciful Love had less appeal to the Basque public than darker calls for penance, atonement, and sacrifice.

"I am Merciful Love!" holy card, ca. 1932

Two orders with influence in the area, the Benedictines and the Jesuits, kept their distance from the visions. At the Benedictine monastery of Lazkao, eight kilometers from Ezkioga, most monks strongly opposed the visions and told their confessants not to go.[61]

J. B. Ayerbe claimed to García Cascón, 22 March 1934, 3 pages, typewritten (AC 416), that Conchita Mateos convinced her confessor at Lazkao, Padre Leandro. A seer from Zaldibia entered a Benedictine convent in Oñati: Rigné, Ciel ouvert, p. D.

The Jesuits did not report the visions in their magazines even in the first months. The elite male order in Spain, they educated Spain's elite. They were largely an urban order and were less likely to be related to the seers at Ezkioga. I know of few direct Jesuit links even to believers.But even before Laburu got involved, the Jesuits could hardly ignore what was happening. Their great shrine at Loyola was only twenty kilometers away, and the confessionals periodically filled with people from the vision sessions. Pilgrims

to Ezkioga from other parts of the country and abroad made detours to see Loyola and inevitably commented to the fathers about the visions. Nonetheless, in the summer and fall of 1931 the Jesuits were keeping a low profile. In May Jesuit houses had been burned down in Madrid and elsewhere, and they knew most republicans thought the order should be dissolved. Antonio de la Villa accused them in the Cortes of promoting the Ezkioga visions, the accusations itself a cause for prudence.[62]

B 51-52, 751-752. See the Azpeitia correspondent's passionate reply to de la Villa in A, 23 August 1931, p. 2.

Examples of Jesuits speaking even guardedly in favor of Ezkioga were thus rare. A Jesuit at Loyola told two French visitors from Tarbes that the purpose of the visions at Ezkioga and Guadamur was not to set up a shrine like Lourdes but to warn of impending persecution and to revive the faith of Spaniards. Salvador Cardús of Terrassa corresponded with a Jesuit in India who was interested in Ezkioga and Madre Rafols, but even this distant friend requested great discretion lest "someone else, with indiscreet zeal, might later go around saying to people, 'A Jesuit said this,' and many times it turns out that what was said with the best of intentions is not interpreted in the same way."[63]

French visitors at Loyola at end of August, "Les Apparitions d'Ezquioga," La Croix, Paris, 15 October 1931, p. 3, from Le Semeur, Tarbes. Pere Pou i Montfort S.J. to Cardús, Sacred Heart College, Shembaganur, Madura District, 18 August 1932.

Believers resented the Franciscans but held no grudge against the Jesuits, despite Laburu's hand in their defeat. A Jesuit from Betelu was the key person distributing the prophecies of Madre Rafols. And the ex-Jesuit Francisco Vallet had prepared the followers of Magdalena Aulina. Male seers went to the Jesuits for spiritual exercises. Even the Ezkioga souvenir shops of Vidal Castillo had a Jesuit connection: they were owned by the Irazu family, who ran the stands at Loyola and Limpias. So however much the Jesuits tried to keep their distance from Ezkioga, they formed in fact a part of the context that nurtured the visions.

Hence we find visions in which the seers protest the expulsion of the Jesuits, settle into stances that seem to replicate those of Ignacio de Loyola in paintings or in the wax statue at Loyola, and report seeing Loyola himself giving Communion. And, as in the case of the Benedictines, believers occasionally came across a Jesuit they considered sympathetic. Nuns from Bilbao persuaded one Jesuit to go see Gloria Viñals when he was in Pamplona, and López de Lerena alleged that he subsequently had a vision of his own in the cathedral. After the war the Jesuit confessor of a seer from Azkoitia introduced him to another Jesuit in a high position in the Vatican. But the believers I talked to knew of no member of the order who worked actively or spoke out publicly for their cause, and the documents I have read mention no Jesuit other than Laburu who actually went to Ezkioga.[64]