Preferred Citation: Christian, William A., Jr. Visionaries: The Spanish Republic and the Reign of Christ. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5q2nb3sn/

| VisionariesThe Spanish Republic and the Reign of ChristWilliam A. Christian Jr.UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Christian, William A., Jr. Visionaries: The Spanish Republic and the Reign of Christ. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5q2nb3sn/

CHRONOLOGY

|

|

|

|

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

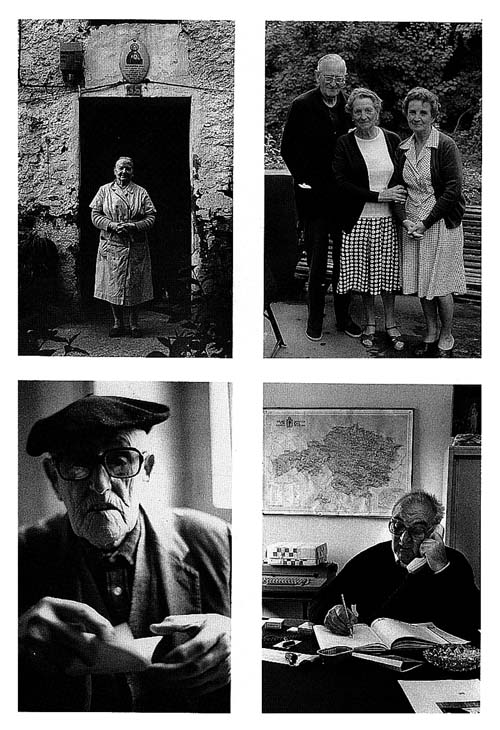

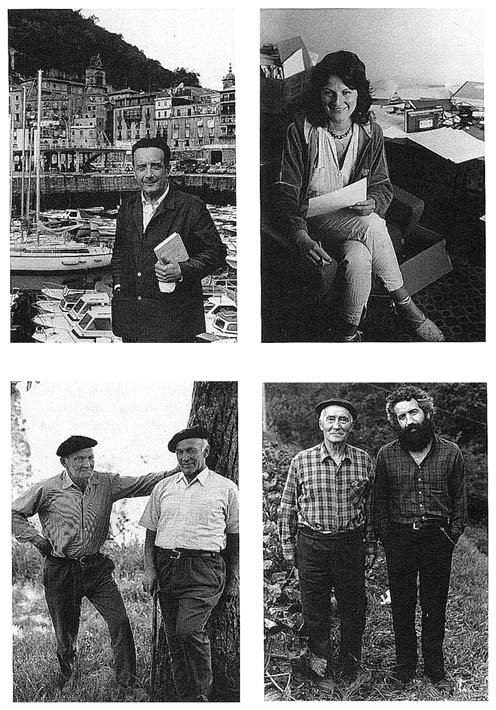

When I started this work in earnest, in 1982, the visions at Ezkioga were within the range of useful memory. Some of those I thank below have died; others who talked to me have now forgotten not only what they knew but who I am. Eyes once bright are now weak. Every citation in the notes is a heartfelt thanks. I thank the following persons who helped me gain access to sources: Francisca Aguirre, Txemi Apaolaza, Gurutzi Arregi, Asier Astigarraga, Matilde Ayerbe, José Miguel de Barandiarán, Iñaki Bastarrika, Jesús Beraza, Josefa Bereciartu, Peter Brown, José María Busca Isusi, William A. Christian, Sr., Salvador Cardús (grandson) and Oriol Cardús Grau, Julio Caro Baroja, Leonor Castillo, Juan Celaya, Simone Duro, Jon Elorriaga, Francisco Ezcurdia, Cristina García Rodero, Angel de la Hoz, Luis Irurzun, Temma Kaplan, Rhys Isaac, William James, Marivi and Lorenzo Jayo, Lynzee Klingman, Manuel Lecuona, Ander Manterola, Andrés de Mañaricua, Andrea Marcos, José Martínez Julià, Francisco Mendiueta, Pío and Angeles Montoya, Antonio Navarro, Santiago Onaindia, Dionisio Oñatibia, Ignacio

Oñatibia, Jabier Otermin, Richard Pearce, Joan Prat, the widow of Fernand Remisch, Lourdes Rodes, Salvador Rodríguez Becerra, Josefina Romà, Antoni Sospedra Buyé, José Ignacio Tellechea Idigoras, Ignasi Terradas, Gail Ullman, and Laurence Wylie. Others requested anonymity but know who they are.

Libraries and archives: Archivo diocesano de Vitoria, A. González de Langarica; Archivo diocesano de San Sebastián, Andoni Eizaguirre; Archivo diocesano de Pamplona, J. Salas Tirapu; Seminario de Vitoria, Ignacio Oñatibia; Jesuit Province of Loyola, J. R. Eguillor; Hemeroteca Municipal de San Sebastián, Arantxa Arzamendi; Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid; Biblioteca de la Provincia de Castilla, PP. Capuchinos, Madrid; Hemeroteca Municipal de Barcelona; all the staff of Instituto Labayru, Derio, who were extraordinarily attentive; Euzkalzaindia; Bibliotecas Municipales de Bilbao, Terrassa, Sabadell, and Reus; Editorial Auñamendi, especially Idoia Estornés Zubizarreta; Archivo Histórico de Navarra; Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid; Centro Nacional de Microfilm, Encarnación Ochoa; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Bibliothèque Royale, Bruxelles; Library of Congress, especially Dolores Martin and Georgette Magassy Dorn; Wilson Center Library, especially Zed David; Getty Center Library, especially Lois White and Chris Jahnke; and the Basque Studies Center at the University of Nevada, Reno.

During much of this project I had the support of fellowships. My deepest gratitude to the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the U.S.-Spanish Cultural Committee, the Woodrow Wilson Center, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities.

The following readers commented on the entire manuscript: L.W. Bonbrake, Harvey Cox, Henk Driessen, James Lang, Kathryn Sklar, Richard Trexler, and two anonymous readers. Henk Driessen, James Lang, and particularly Richard Minear made especially careful readings. Others read particular chapters: Jodi Bilinkoff, William Callahan, Oriol and Josep Cardús, Eric Foner, Lynn Garafola, Judith Herman, Michael Holly, Willy Jansen, Gábor Klaniczáy, Aviad Kleinberg, Ander Manterola, Gaspar Martínez, Lourdes Rodes, and Tom Yager. Joseba Zulaika supported this project with head and heart from start to finish. Biotz-biotzen lagun .

My expert copy editor, Amanda Clark Frost, devoted considerable time and energy to making this book clear and coherent. Michelle Bonnice oversaw the book's production and helped with the hard choices among photographs. Randall Goodall designed the book and the jacket. In 1972 Stanley Holwitz saw to the publication of Person and God in a Spanish Valley, the engine in this long train of thought, and I am grateful for his support and advice in the final stages of this work. Josefa Martínez Berriel, Fatima Martínez Berriel, Josefa Berriel Jordán, and the rest of the clan cheerfully did my chores when I was away from home. This work is for Pepa and Palma with all my love. Just as the visions were a collective enterprise, so was this book. Thank you one and all.

PROLOGUE

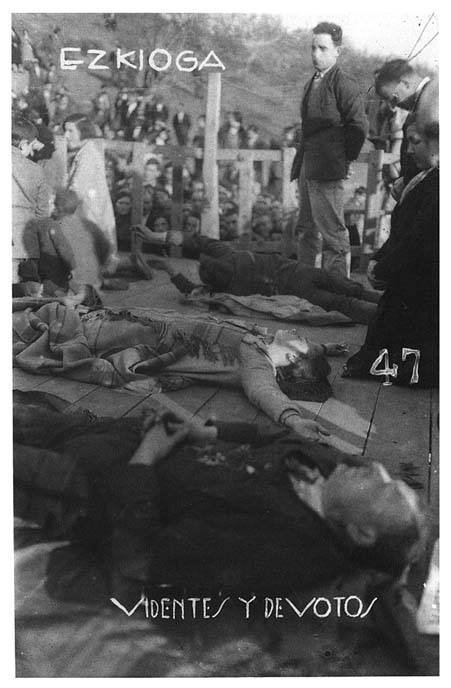

On 29 June 1931 two young children in the Basque Country of northern Spain said they saw the Virgin Mary. That initial vision led to many others. Indeed, for many months visions took place on a nightly basis. In 1931 alone, about one million persons went to the apparitions on a hillside at Ezkioga and people began having visions in a score of other towns. The hundreds of seers at Ezkioga attracted the most observers for any visions in the Catholic world until the teenagers of Medjugorje in the 1980s.

This book is about two kinds of visionaries and their interrelations: the seers (videntes in Spanish, ikusleak in Basque) who had visions of Mary and the saints and the believers and promoters who had a vision for the future which they hoped Mary and the saints would confirm. Almost all are now dead, but they left behind words on paper, images in photographs, and memories in people who believed them. The protagonists included nuns, friars and priests, writers and photographers, military officers and civil servants, housemaids and aristocrats, farmers and textile manufacturers, and

many, many children. Starting in 1931, they made a long, concerted attempt to convince a skeptical world that heavenly beings were appearing on the Iberian peninsula.

I have immersed myself in their lives, retraced their steps, hunted down their papers, attempted to reconstitute their world. When I began to write, the pleasure of telling their story mingled with regret that my time with them would soon be over. I am not one of them, as I never failed to tell their present-day survivors and successors. But while their efforts to arouse the world failed, the efforts of others like them in the past did not fail and most certainly have affected our world. How visions occur and who believes in them is everybody's business.

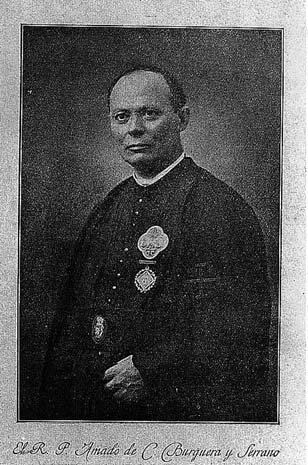

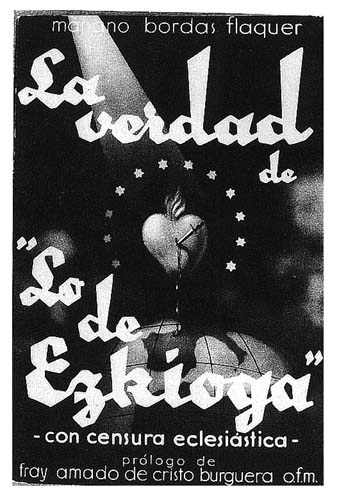

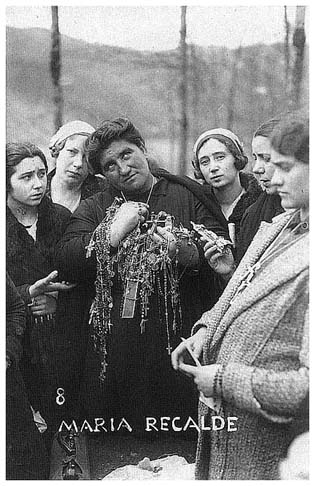

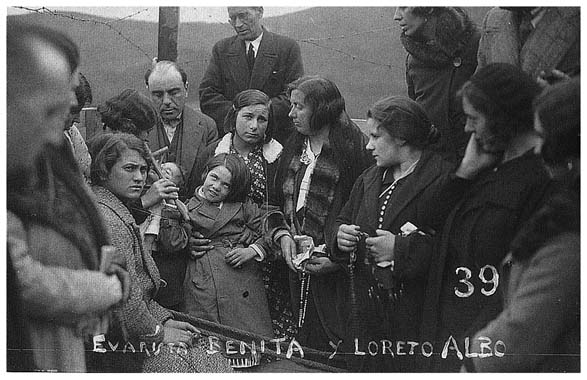

At this moment I am watching from my window exotic birds called hoopoes, sandy with black and white stripes, their crests flaring as they clash and play in the red-brown field of young, blue-green cabbages. They swerve, chatter in the air around each other, then separate to bob and feed in the shallow furrows. I have told stories of lives that begin before the visions, loop into them, intersect, and then loop out, each to a separate destination. In the first half of the book I tell the tales separately, building the picture of events layer on layer from the perspective of the different protagonists. For the people would not let me go. Through my immersion in this unusual world, their story has also become mine. This is not earthshaking history. It is small, intense, poignant, sometimes fierce, often funny. Its lasting lessons, I think, are about human nature itself. Like a novel, this book has a cast of characters, here listed as a separate index of persons at the end of the book. Unlike a novel, the story is a true one—at least as true as I can make it. For me, as I entered the story, Benita Aguirre, Padre Burguera, María Recalde, Mateo Múgica, and their contemporaries became quite familiar, a little larger than life. I hope readers too will get to know and enjoy them.

Readers seeking a narrative of the events can turn to four chapters: "Mary, the Republic, and the Basques," "Suppression by Church and State," "The Proliferation of Visions," and "Aftermath." Three other chapters about promoters and seers cover the events at Ezkioga through the lives of the principals.

The second part of the book uses the visions to detail the often secret ways that seers and clergy connected, the landscape seers imagined and constructed, and the trancelike states seers entered. The visions linked women with priests, the rural poor with the industrial wealthy, and the living with the dead. The events at Ezkioga show how much people welcome the chance to go beyond the world around them, see what the gods see, and know what only the gods can know.

José Donoso suggested that I stick with a few key characters and tell the events through them. But by then I knew too much about too many people. I had to tell

what I knew to resolve my story as well as theirs. I regretted starting to write, but I have no regrets at coming to the end. The hoopoes have gone. Men are outside sending shafts of water curling down the furrows of cabbages, shouting instructions, opening and closing passages of dirt.

TAFIRA BAJA, GRAN CANARIA

1 SEPTEMBER 1994

1.

INTRODUCTION

VISIONS OF THE divine are as old as humanity. They have continued in the postindustrial age. You may read about them in tomorrow's newspaper. The visions at Ezkioga in 1931 reflect a phase in the history of Western society and in the place of Catholic divinities in that society. Their story is also universal and perennial: it is the story of people who claim to speak with the gods and try to tell what they heard and saw and it is the story of other people who try to stop them.

Spanish Catholics used to deal with the divine not only as individuals but also as members of groups. Legally, citizens owed devotion to the town's patron saints. Members of guilds or professions had additional obligations to other saints. Typically, the Virgin Mary in a specific local avatar was the protector of a community for general problems, and some of her shrines, like Guadalupe and Montserrat, drew devotion from vast areas. Other saints were specialists for particular problems. People understood apparitions as one of the many ways that Mary and other saints bestowed protection and requested devotion.

In fifteenth-century Spain the visionaries that people believed tended to be men and children. The divine beings they saw generally offered ways for towns to avoid epidemic disease and often called on towns to revive older, dormant chapels in the countryside. Some of the visions harked back to stereotypic scenarios of "miraculous" discoveries of relics and to legends of similar discoveries of images. Two centuries earlier, theologians had condemned as pagan some of the motifs in the visions—Mary clothed in white light on a tree, a nocturnal procession of a woman accompanied by the dead. By the second decade of the sixteenth century the Inquisition had stifled these visions in central Spain. Local and devotional, the visions were no threat to doctrine, but both the church and the monarchy were afraid of heretics and freelance prophets.[1]

Christian, "Santos a María" and Apparitions; Niccoli, Prophecy.

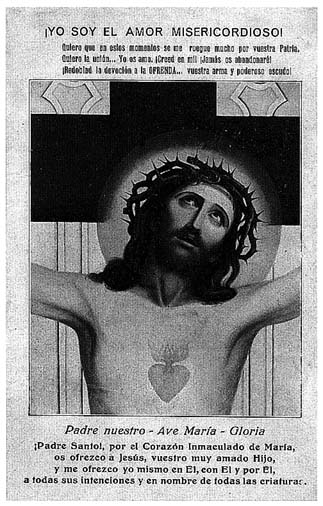

The Counter-Reformation served to focus devotion on Mary in the parish church rather than on specialist saints in dispersed chapels. A new set of lifelike images of Christ joined those of Mary as sources of help. In this period, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Spanish Catholics found alternate miraculous events that did not threaten the church's control of revelation. In particular, towns turned to an ancient tradition of bleeding and sweating images. In these miracles without messages, everyone was a seer and the clergy controlled the meaning. Most of the three dozen or so Spanish cases of images that "came alive" in the Early Modern period were of Christ in some phase of the Passion. These events occurred particularly in years of crisis.[2]

Christian, Religiosidad local, 234-241, and "Francisco Martínez."

At the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century bishops discouraged this kind of religiosity as superstitious.Religious orders had their own images whose power was independent of place, like Our Lady of Mount Carmel. One such image, which the Jesuits in particular propagated, was the Sacred Heart of Jesus, based on the visions of the nun Marguerite-Marie Alacoque (1647–1690) in Paray-le-Monial, northwest of Lyon. She said that Jesus, with his heart exposed, promised that he would reign throughout the world. Devotions like Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the Sacred Heart came to have standardized images and the pope rewarded prayers to these devotions with indulgences. Communities often domesticated these general figures for local use, and some of these standard images became the focus of shrines in their own right, like Our Lady of Mount Carmel of Jerez and Paray-le-Monial itself. There was a constant tension between the Roman church, allied with religious orders, which stimulated devotions and holy figures that were inclusive and universal, and the local church, identified with nation, town, or village, which tended to fix a devotion and make it exclusive and local.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, however, when Catholicism was on the defensive, the Vatican came to realize that the church should play to its strength. In southern Europe that strength lay in localized religion. By "crowning" Marian shrine images, the papacy associated them with the universal church. Rome also endorsed a new series of proclamations of Marian images as patrons

of dioceses or provinces. And it regarded with increasing sympathy visions of Mary that led to the establishment of new shrines. For by the nineteenth century virtually every adult in the Western world knew that there were profoundly different ways to organize society and imagine what happened after death. The industrialization of Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had separated large numbers of rural folk from local authority and belief and many migrants to cities had found alternatives to established religion in deism, spiritism, science, or the idea of progress.[3]

Cholvy and Hilaire, Histoire religieuse, 2:19-64, 347-349.

The continued strength of Catholicism in nineteenth-century France was an incentive for intellectuals to challenge the idea of the supernatural radically and intensively. As a result, French Catholics needed all the divine help they could get. Throughout the century they sought and received innumerable signs that God and, in particular, the Virgin Mary were with them. An efficient railway system and press ensured that regional devotions could reach national audiences. Secularization was a global problem, and the Vatican developed a global response to centralize and standardize devotion. France and Italy served as laboratories for devotional vaccines against moral diseases. Religious orders distributed these vaccines. Indeed, Our Lady of Lourdes became a new kind of general devotion, one with its origin in the laity. Replicas of the image entered parish churches worldwide.[4]

Taves, Household of Faith, 89-111; Larkin, "Devotional Revolution"; Lynch, "Church in Latin America."

Visions took place throughout the nineteenth century in France.[5]

For examples of visions see Delpal, Entre paroisse et commune; Commission, N-D de Dimanche; and Heigel, "Les Apparitions." See also Hamon, N-D de France, for Domjevin (Nancy) 1799-1803 (6:59), Scey (Besançon) 1803 (6:273-275), Saint-Cyprien (Périgueux) 1813 (4:137), Lescouët (St. Brieuc) 1821 (4:545), and Montoussé (Tarbes) 1848 (3: 450).

Three particular French visions set important precedents for the events that are the subject of this book: those of Catherine Labouré in Paris in 1830, those of Mélanie Calvat and Maximin Giraud at La Salette in 1846, and those of Bernadette Soubirous at Lourdes in 1858. The people of Spain knew about these episodes from pious accounts.According to these accounts, the Daughters of Charity delayed admitting Catherine Labouré, age twenty-four, until she learned to read and write. She had numerous visions, but the first in the series that made her famous occurred in July 1830, after she had been a novice three months. A spirit boy about five years old woke her and led her to the main altar of the novitiate, where she found the Virgin Mary seated. Mary wept violently, told of great disasters that would befall France and all of Europe, and said that Catherine, the Daughters of Charity, and the Vincentian Fathers would have grace in abundance. This was only days before the revolution of 1830, during which crowds attacked many churches and religious houses. Four months later, in November, Catherine saw Mary emerge resplendent from a dark cloud in the church. The Virgin bore a halo of words: "O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who come to you for help!" She held a small globe in her hands and lifted it up to heaven, where it disappeared. The Virgin then held out her hands and suddenly on each finger there were three rings covered with precious jewels giving off bright rays. Catherine saw the image revolve. On its back there was an M with a cross on top and below it the Sacred

Hearts of Jesus and Mary. She heard a voice say, "It is necessary to strike a medal that looks like this. All who wear it … will receive many favors, above all if they wear it around the neck." Mary insisted on the medals in successive appearances until finally Catherine's confessor, Jean Marie Aladel, ordered them made.

Labouré's visions were like those of other religious who received privileges for their orders. In this the Miraculous Medal was like the scapular of the Carmelites and the rosary of the Dominicans. The timing of Labouré's visions and the iconography—the Virgin had her foot on a serpent—pointed to the medal's assignment as a response to the devil and his works. Aladel emphasized the medal's efficacy for nonbelievers and Protestants as well as Catholics. The church publicized widely how the medal converted a Jew in Strasbourg in 1842. It worked apparently even if someone merely slipped it under a pillow. By 1842 people had bought 130,000 copies of Aladel's description of the visions and well over one hundred million medals.[6]

Aladel-Nieto, Sor Catalina, 62-63, 70-71, 93.

The pious accounts of the visions of La Salette were as follows: in 1846 in the French Alps near Grenoble, Mélanie and Maximin, fifteen and eleven years old, respectively, saw a lady in white. She warned of an imminent famine as a punishment from Christ and called for people not to work on Sundays and not to swear or eat meat on fast days. She also gave the children secrets. The waters there soon produced cures. And a military officer found a likeness of the face of Christ on a fragment of the rock on which the Virgin had sat. People began to go to the site in numbers. In 1851 the bishop of Grenoble decreed the visions worthy of belief and forbade any criticism of them. Subsequently, Mélanie released versions of her secret, which resembled medieval apocalyptic prophecies. The La Salette apparition was private. No one saw the children seeing the Virgin. And the seers did not claim to enter a trance state. In these ways too the La Salette visions were similar to medieval visions.[7]

Zimdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary, 43.

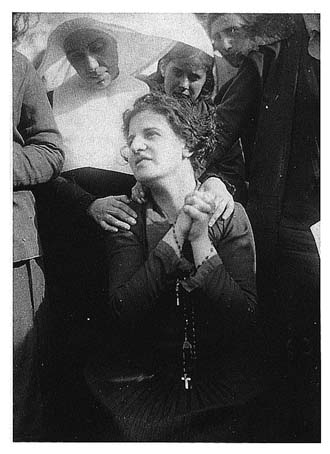

The visions of fourteen-year-old Bernadette Soubirous of Lourdes marked a change. In 1858 Bernadette saw the Virgin about three dozen times over five months in the presence of crowds that reached thousands in number. She went with a lighted candle and prayed the rosary in public. The Virgin told her, she said, to return for fifteen days. Eventually over fifty persons had visions in and around the same cave. Bernadette's abstracted state while having visions convinced a skeptical doctor and through him other town worthies.

Prior to these nineteenth-century French cases, visions by rural laypersons had addressed broader geopolitical issues only occasionally.[8]

Niccoli, Prophecy, 61-88.

Many people understood the visions at La Salette and Lourdes simply as signs to establish new shrines. But the secrets that Mélanie divulged addressed the division between Catholics and rationalists. And at Lourdes the Virgin reaffirmed the authority of the pope by confirming the dogma of the Immaculate Conception.Although many churchmen were reluctant to accept children as carriers of messages from God, the French visions put these doubts by and large to rest. The

crowds that converged on Lourdes by rail eventually made it one of the most popular shrines in Christendom. By the turn of the century the cures there became the great new argument not only for Bernadette's visions but for the Catholic religion and the supernatural in general. When in the First World War the bishop of Tarbes called on the Virgin to help France against Germany, even the Third Republic made peace with Lourdes.

How did these visions affect Iberia? In the nineteenth century Catholics in Spain, their church shorn and starved, needed a lift as much as those in France. Urban radicals and poor people afraid of cholera went on a rampage in the summer of 1835, killing seventy-eight male religious in Madrid and sacking religious houses throughout much of Spain. Liberal governments suppressed virtually all male religious orders and gradually sold off most church property. Spanish clerics began to look to the papacy for help and moral support. When the orders filtered back into Spain—first the female service orders, then the male ones—they brought new devotions from France and revived older general ones like the Sacred Heart of Jesus.[9]

Callahan, Church, Politics, 128-158, 161, 194, 212, 232-237; see esp. p. 235: "Scruples that led some eighteenth-century bishops to restrain cults were set aside in favor of an effort to spread them like seeds thrown upon the fields."

The Daughters of Charity entered Spain in increasing numbers after 1850. Vincentians published Jean Marie Aladel's book on Catherine Labouré in Spanish in 1885. By 1922 there were twelve thousand members of the Association of the Miraculous Medal in Spain, mainly children in schools run by the Daughters of Charity. In May 1930 the primate of Spain, Cardinal Pedro Segura, held a national conference in Madrid celebrating the centenary of the visions. Five bishops led a procession including three floats of Labouré seeing the Virgin.[10]

Pérez, Historia Mariana, 5:115.

Less than a year after the La Salette vision, people in Barcelona could buy pamphlets about it in Spanish and Catalan, and by 1860 they could buy manuals in Spanish for pilgrims. In 1883 Catholic militants in Barcelona formed the association of Our Lady of La Salette to combat both blasphemy and work on Sunday. They held dawn rosaries in the city streets. They eventually had to desist when crowds gathered to harass them and sing the Marseillaise. Spaniards who worried about the apocalypse knew Mélanie's prophecy. Eventually it intruded on the vision messages of Ezkioga.[11]

Pérez, Historia Mariana, 4:221-222, cites La Voz de María Santísima de la Saleta. For cult in Spain, see Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 10, 160 n. 5.

Lourdes became the spiritual touchstone of the times. There is no facet of the Ezkioga visions—the liturgy, the prayers, the new shrine, the chief promoters—that Lourdes did not influence. Lourdes was just across the Pyrenees. Devotion was intense in the Basque Country, Navarra, and Catalonia, all areas critical to this story. Prior to the Spanish Civil War in 1936 the Basque Country and Catalonia each provided over 30 percent of Spain's pilgrims to Lourdes. There had always been close ties across the mountains, and Basque, Navarrese, and Catalan cultural zones straddled the frontier. Basques considered Bernadette one of theirs, and Basque nationalists held pilgrimages with a political slant.

Spanish pilgrims saw that Lourdes was revitalizing Catholicism in France and began to hope for a Lourdes in Spain.[12]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 6-16, 149-151.

In the first two decades of the twentiethcentury Spanish visions that reached the press occurred mainly in the zone of devotion to Lourdes. In them people saw images of Christ move or agonize. This trend came to a climax at Limpias, a small town in Cantabria close to the Basque Country, precisely when World War I prevented travel to the shrine of Lourdes. In the period 1919–1926 the Christ in Agony at Limpias attracted over a quarter of a million pilgrims. The diocese of Santander modeled the Limpias pilgrimages on those of Lourdes. We can document at least forty-five pilgrimages and tens of thousands of pilgrims from the Basque Country and Navarra. About one in ten of the pilgrims saw the image move. The visions occurred in a period of high inflation, general strikes, and political turmoil. Some of those in power understood the visions as divine signs in favor of the nation. As at Limpias a year earlier, children and adults of a village in Navarra saw their crucifix move in 1920. These visions at Piedramillera lasted for more than a year, but the diocese took care to limit newspaper reports and people gradually stopped going there.

The visions at Limpias and Piedramillera were hybrids. Like the baroque miracles of the Early Modern period, they involved preexisting statues of Christ nd did not include explicit messages. But like the medieval visions and those of Catherine Labouré and the children of La Salette and Lourdes, they were subjective experiences. That is, the cruxifixes had no liquid on them and only some people saw them move. Spaniards appeared to be inching toward the full-fledged talking apparitions of the medieval past, which the French had already revived. The visions at Limpias and Piedramillera were important precedents for those of Ezkioga.[13]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes.

By July 1931 Spaniards, and Basques in particular, had just begun to hear about the visions at Fatima in Portugal. Led by Lucia Dos Santos, born in 1907, children in a hamlet to the north of Lisbon had several visions from 1916 on; the most famous were those on the thirteenth day of six successive months in 1917. The Fatima visions took place during an anticlerical republican regime and they became a reaffirmation of Catholicism. In 1927 a Dominican magazine in the Basque Country began to publish accounts of cures at Fatima, which the author considered "a permanent challenge to materialist and rationalist criticism." In 1930 the magazine described the visions after the bishop of Leire in Portugal declared them worthy of credit. But Fatima did not gain popularity in Spain until the 1940s, after Lucia revealed messages that gave the apparitions an explicitly anticommunist slant.[14]

Mateos, "Ntra. Sra. del Rosario de Fátima," 711. For Fatima, ten articles, most by Mateos or Vélez, in El Santísimo Rosario (Bergara), 1927-1931; Mensajero de Corazón de Jesús (Bilbao), 1928, pp. 181-183, and 1929, pp. 374-375; Jáuregi, Jaungoiko-zale, 1929 and 1931; and Rosas y Espinas, 15 April 1931. Stimulated by Ezkioga, there was a new spate of interest in Fatima in July 1931: see Efrén, GN, 15 July, and PV, 17 July; Aldabe, LC, 25 July; Arribiribiltzu, A, 26 July; and ED, 28 July.

The visions at Ezkioga were the first large-scale apparitions of the old talking but invisible type in Spain since the sixteenth century. But they included the innovations of Lourdes: there were many seers, the seers had their visions in public view, and most of the seers entered some kind of altered state. We will see how the social and political situation of Spain and the Basque Country encouraged Catholics to believe the seers.

The reader should know something about nationalism in Spain, the Basque Country, and Catalonia. The less authoritarian and more democratic the central government, the less Spain coheres. At present, in the new freedom after the long dictatorship of Francisco Franco, in the Basque Country and Catalonia in particular, many people are careful to refer to Spain only as a state, not as a nation. When the majority of male voters brought in the Second Republic in April 1931, Spain was a mosaic of cultures that hundreds of years of royal rule had done little to homogenize. The regions with the strongest nationalist movements were those with the most international contacts: the Basques lived on both sides of the border with France and had a major trading partner in Great Britain; Catalonia, also on the border, traded with the Mediterranean countries and the Caribbean. These external contacts meant that some regional elites did not depend entirely on Madrid and resented its taxes, bureaucracy, and language. Eight years of centralized rule by General Miguel Primo de Rivera in the twenties had exacerbated these resentments. Even in regions with virtually no separatist sentiment in 1931, people had a strong sense that they were different culturally. The Navarrese, for instance, had a past that helped them maintain an identity distinct from that as Spaniards. Navarra was once an independent kingdom that spanned the Pyrenees. Those Navarrese who lived in a strip running across the north of the province spoke Basque, and in the distant past most of the region's inhabitants had been Basque-speaking. Most still had Basque family names and lived in towns with names of Basque origin.

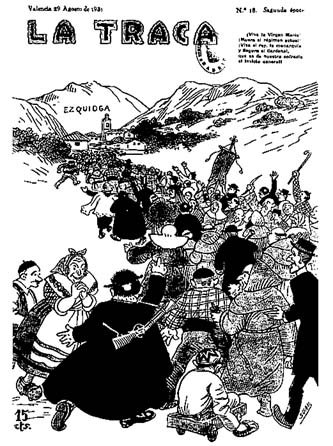

As a mass phenomenon the apparitions at Ezkioga were a kind of dialogue between divinities and the anticlerical left—anarchists and socialists in the Basque coastal cities, socialist farmworkers in Navarra, republican railway officials and schoolteachers in rural areas, anticlerical poor in cities throughout Spain, and socialist and communist movements worldwide. In this aspect Ezkioga was similar to other modern apparitions. As over the years the enemy changed from Freemasons and liberals to communists, the messages seers conveyed changed to maintain the dialogue. But any analysis that reads the last two centuries of Marian visions as a clerical plot to thwart social progress is impoverished, as we shall see.[15]

I refer especially to Perry and Echeverría, Heel of Mary, despite its pleasing scope and detail, and de Sède, Fatima.

To be sure, visions are easy to manipulate for political purposes. But at Ezkioga people of all classes immediately put the seers to work for other practical and spiritual ends. Apparitions spark little interest without people's general hunger for access to the divine.To ascribe visions to particular psychological needs—sexual drive, for example, or the search for parental affection—constitutes another kind of reduction. Of necessity observers base such theories on a very small and very skewed sample; the visionaries who become famous. It might well be that a given psychological profile simply makes seers more believable or more likely to persist in their visions. There will be visions as long as people believe in them, so to

understand visions we must study the believers. Thus one set of lessons we can draw from the visions at Ezkioga has to do with context.

Other lessons are less bound to time and place. In religions people interact with the gods and with one another. This study is in part a window on how new religious worlds come to be. All innovation has to struggle against an established order that attempts to absorb or suppress it. Visions are intrinsically subversive; they go over the head of human to divine superiors. In this sense Ezkioga is a microcosm of the excitement and crosscurrents of every schism and heresy.

Another larger theme is the way people formulate their hopes. At Ezkioga people did so in various ways. One was a collective process of trial and error by which local elites, the press, and the general public selected and rewarded certain vision messages. Here it almost seems appropriate to speak of a collective consciousness. Particular groups also induced messages with a desired content by their questions. These processes illustrate the wider question that underlies this work: how society structures perception.

I wrote this book with the advantage of the work of others. And when I had completed the manuscript I read the book by David Blackbourn about the visions that started in Marpingen in the Saarland in 1876 and the books by Paolo Apolito about the visions that started in 1985 at Oliveto Citra in Campania. The visions at Marpingen, like those at Ezkioga, took place in a hostile state and in a diocese without a bishop. The visions at Oliveto Citra have had even more seers than those of Ezkioga. Apolito was present almost from the start and was able to observe many of the processes that I reconstruct from interviews and documents.

Church sympathy for visions has waxed and waned. It waxed in the mid to late nineteenth century (the model was La Salette and then Lourdes), the mid-1930s (the model was Lourdes), the late 1940s (the models were Fatima and Lourdes), and the 1970s and 1980s (the models were Fatima and Medjugorje). The needs of the church periodically overcome its suspicion of lay revelation, and particular popes have been more sympathetic than others. But there also exists a cyclical dynamic of discouragement that emerges when visions threaten church authority or become commonplace.

Since I began this study, most of the official place-names in the Basque Country and Catalonia have changed. I use the official place-names as of mid-1994. Many of these for Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, and northern Navarra are different, usually only slightly, from the official names in 1931, but they were already in use among Basque speakers and in Basque-language publications at that time. I have respected the old spellings in direct quotations. In part 5 of the appendix I list the Basque places in this book whose names have changed. For the sake of simplicity I have left Vitoria (instead of Vitoria-Gasteiz), Mondragón (Arrasate-Mondragón),

and San Sebastián (Donostia-San Sebastián) in their Spanish forms.

I do not address the question essential for many believers: were the apparitions "true"? As I told my friends among the Ezkioga believers and in the diocese, I must stick to human history. By upbringing and nationality I am an outsider ill-equipped to tell Basques, Spaniards, and Catholics what is sacred and what is profane. In any case, I am quite unwilling to try.

EVENTS

2.

Mary, the Republic, and the Basques

During July and August 1931 at Ezkioga in northern Spain, scores of Basque seers had increasingly elaborate and explicit visions of the Virgin. The visions offered a way to mobilize the Basque community and focus their hopes. Watching Basque society define and tap this new power is like watching a kind of social x-ray or scanner. In the case of the Ezkioga visions, the scan highlights a struggle between competing views of the world. At a turning point in Basque and Spanish history, local leaders, the press, and the audience helped the visionaries to articulate general concerns.

The Republic and the Catholic North

From 1874 to 1923 Spain was a constitutional monarchy in which the Liberal and Conservative oligarchic parties alternated in power. During this period parts of Catalonia and the Basque Country rapidly industrialized. As in much of Western Europe and North America, the labor movement in Spain reached a peak of strength at the conclusion of World War I. In the face

of labor unrest and regionalist movements, General Miguel Primo de Rivera installed a military dictatorship, still under royal legitimacy, which lasted from 1923 to 1930. After the general stepped down, the municipal elections of April 1931 became a referendum on the monarchy itself. Republicans won in most major cities and proclaimed the Second Republic. King Alfonso XIII went into exile.

The fall of the monarchy jarred an entire order in which for centuries the relation of king to subjects had been the model for relations of God to persons. By extension it even shook the belief in God. It opened the door to changes in relations between women and men, workers and employers, laity and priests, and children and parents. Human relations are by nature imitative. The change to a republic led to changes in the ways people treated one another. Of course, the fall of the monarchy was effect as well as cause—the effect of gradual shifts in a whole host of social relations, particularly as a result of militant labor movements. Visions of Mary throughout Spain in the spring and summer of 1931 were short-term consequences of the change in the regime, but they also reflected more long-term changes.

On 23 April 1931, nine days after the advent of the Republic, children playing outside the church of Torralba de Aragón (Huesca) saw what they thought was the figure of the Virgin Mary pacing inside, and one girl heard the Virgin say, "Do not mistreat my son." Citizens took this to be a reference to a crucifix in the town hall which the anarchist minority had taken down and broken up. Catholic newspapers reported this vision throughout Spain.[1]

The original story about the Torralba visions was in La Voz de Aragón (Lacasa, 26 April 1931). Newspapers mostly copied the version in El Debate, 29 April 1931 (ED and LC, 30 April 1931), which reached many children directly in Orzanco, "Las apariciones." The child seers of Ezkioga allegedly read the Basque version in Argia, 5 May 1931 (Masmelene, EZ, 15 July 1931). In 1975 I spoke to one of the Torralba seers, by then somewhat tentative and sheepish, in Zaragoza.

Two weeks later, from May 11 to 13, anticlerical vandals set fire to dozens of religious houses in Madrid and Andalusia. Banner headlines and photographs of gutted buildings and headless images left Spain's Catholics with little doubt about the will of the new republic to defend church property. In mid-May seminary professors in Vitoria, seat of the Basque diocese, concluded that they had no way to affect the policies of the government in Madrid and that instead they should concentrate on preserving the faith in the Basque Country. A priest who attended the gathering told me, "It was a fortress mentality … the attitude of us versus them." Further evidence of government hostility came with the expulsion from Spain of Bishop Mateo Múgica of Vitoria for agitating on his pastoral visits (May 17) and of Cardinal Pedro Segura, archbishop of Toledo and primate of Spain (June 16).[2]

Elderly priest present at Vitoria meeting, 10 September 1983, p. 5; on expulsion of Bishop Múgica see Rodríguez de Coro, Catolicismo vasco, 51-55; Buonaiuti, Spagna 1931, 82; and Arbeloa, "La expulsión."

In the Basque Country the superiors of urban religious communities asked for police protection. Their fears increased after a fire of suspicious origin at the Benedictine monastery of Lazkao on May 20. Strikes heightened the tension. In a general strike on May 26 and 27 fishermen, workers, women, and children from Pasaia marched on San Sebastían. Police gunfire killed six and wounded scores.

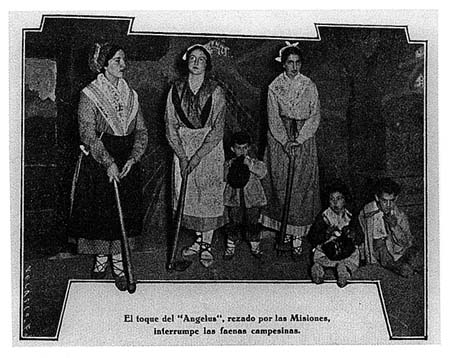

In June this tension found an outlet in religious visions in Mendigorría, a town of 1,300 inhabitants thirty kilometers southwest of Pamplona in the Spanish-speaking

part of Navarra. In 1920 in the adjacent town of Mañeru children had had visions of a crucifix moving. Mendigorría, like Mañeru, was a devout town that produced many religious vocations. On 31 May 1931 the Daughters of Mary attended a mass with a general Communion and a sermon by a Capuchin from Sangüesa. In the afternoon, accompanied by the town band, they carried an image of the Virgin through Mendiogorría.[3]

DN, 9 June 1931, p. 7. What follows is a best-guess composite of printed reports and oral testimony of villagers of Mendigorría, including one of the seers, on 9 April 1983 and 31 July 1988.

On the evening of Thursday, June 4, the feast of Corpus Christi, the village priests were in confessionals preparing children for the Communions of the first Friday and the town band was playing in the square. The month of June was dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and this image was on a table in the church. A girl went in and saw an unearthly woman in mourning clothes kneeling on a prayer stool before the Sacred Heart. Frightened, the girl told her friends outside. A group went in, saw the woman, and went to tell others. More girls, including younger ones, then went in, saw nothing, and started to pray the rosary. According to one of the children, the schoolmistress told them they should pray for Spain, because it was in a bad way. When the prayer leader reached the phrase in the Litany "Master Amabilis," she said she saw the figure, and then many of the others girls cried out, "Look at her!" Some saw first a bright light on the little door of the tabernacle. Others saw only a brightness. Others, including the adults present, saw nothing. One adult told the girls to ask the Virgin what she wanted, but all they could get out was, "Madre mía." One girl fell over a chair when, she said, the Virgin called to her. And she saw the Virgin run onto a shelf between two altars. A seer, then nine years old, told me in 1988 that she saw the Sacred Heart tremble, then "a brightness; it seemed to us to be the Virgin of the Sorrows." At the time she felt a strong, sad feeling in her heart. She still thinks the vision was real, but she does not want me to use her name, lest her family think her loony.Men in the church alerted the priests and rang the bells. After questioning the girls, the parish priest reported to the assembled town what they had said, assured them that he would inform the bishop, and led cheers for the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Catholic religion, the Virgin, and the Jesuits. The church stayed open until midnight, a vortex of emotions.[4]

All 1931: PN, 6 June, p. 7; DN, 7 June, p. 7; VG, 7 June, p. 5.

Two days later El Pensamiento Navarro of Pamplona broke the story with a letter from a villager to a relative in the city. Subsequently, the newspaper carried a more cautious version, which the clergy clearly influenced if not composed, leaving open the possibility of an "obsession" on the part of the girls. One seer told me a priest had offered them candy and told them to say that it was a lie, that otherwise they would have to go to jail; but the girls refused and swore they were telling the truth.[5]

PN, 9 June 1931, p. 3.

In addition to at least twelve girls roughly nine to fourteen years old, there was a boy seer as well. Lucio, thirteen years old, was an "outsider" who had recently arrived in town. His mother was originally from Mendigorría and his father came from a village near Madrid. The boy worked as a cowherd and

said—whether before or after June 4 is unclear—that the Virgin had also appeared to him in the countryside. On June 4 he was standing in line for confession and he too saw the Virgin as a mourning lady.

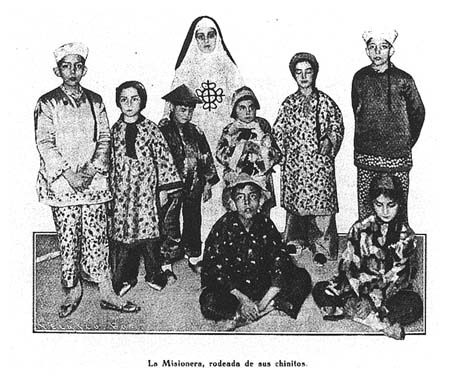

The next day the Vincentian Hilario Orzanco, director of the juvenile magazine La Milagrosa y los Niños, visited the house in Mendigorría of the Daughters of Charity. In his magazine he described the visions as a reward from the Virgin to the girls who had left the music in the square to pray for Spain before the altar of Mary. He pointed to their seeing the Virgin herself in sorrowful prayer before the Sacred Heart and the Eucharist as evidence that she was interceding for Spain and he held up her prayer as an example for his child readers, intimating that they too would have visions if they were good.

To Her, then, we must address ourselves in these days of trial with a heart contrite for the sacrilege and horrible profanation of the Holy Eucharist and its churches. The profound sorrow of the Virgin, as seen in her mourning clothes and her weeping face, should make us turn inward and sweetly oblige us to atone through her for so many sins. You above all, boys and girls, subscribers to this magazine, you must dearly love the Miraculous Virgin. See how the Virgin answers the prayers of good children.[6]

Orzanco, "Las apariciones," 123.

Some of the Mendigorría children were subscribers to the magazine and would have read articles of a similar nature in earlier issues. As with the visions at Torralba a month earlier, those at Mendigorría did not draw many persons and had few consequences for the villagers or the seers, aside from heightening their piety and excitement.[7]

On July 18, at the height of the Ezkioga visions, someone from Pamplona paid for a bus to take the Mendigorría girls to Ezkioga. The woman I talked to said, "They lined us up in a row to see if we saw anything. But we saw nothing." She dismissed the Ezkioga visions as "a lie to make money."

Incidents during the electoral campaign for the Constituent Cortes kept up a generalized fear in June 1931. On June 14 republicans at stations from Marcilla to Castejón assaulted a trainload of Catholic activists returning to Zaragoza from a demonstration in Pamplona. And in Mendigorría itself on the eighteenth, two weeks after the visions, villagers ambushed a busload of republicans with stones and staves. Police had to rescue two republicans marooned on a rooftop, and six others had to go to hospitals in Pamplona for treatment.[8]

All 1931: for train, VG and El Debate, 16 June; for Mendigorría, PN, 19-23 June, DN, 20-25 June, and VG, 20 June; also Martínez Sarrasa, Barcelona, 17 February 1985.

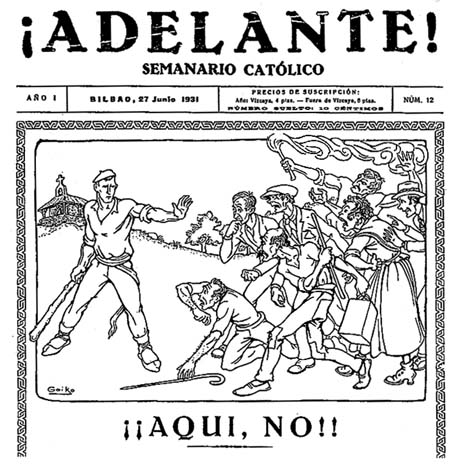

An example of the way Catholics in the Basque Country reacted to all these disturbances was a cartoon on the front page of a Bilbao weekly the day before the election. The drawing shows a single Basque country youth with a club holding off a group of ill-clad urban riffraff carrying burning torches and heading for a rural chapel. The caption read "Not Here!!" An intemperate article railed against immigrant and local leftists.

Here where little by little they have dirtied our land, where little by little they have invaded our home, where little by little they have undermined our tradition, our holy past, our mission, our honor, here, no! Those people, the accusers, the desecrators, the anarchists, cannot live together with us, because we are honorable people.

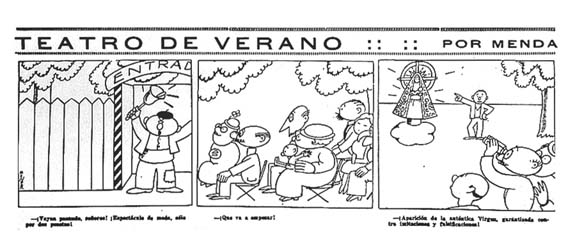

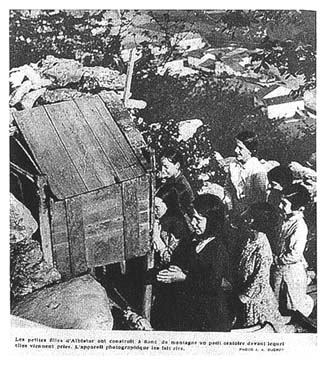

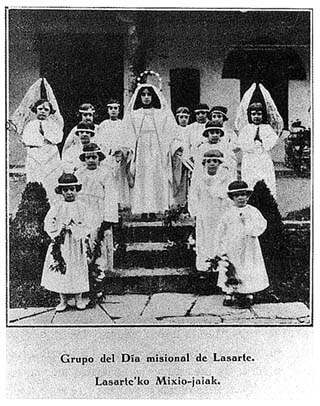

"Not Here!!" Electoral cartoon by Goiko. From Adelante (Bilbao), 27

June 1931. Photo by García Muñoz from a copy in Euskaltzaindia, Bilbao

In the elections rightist coalitions won handily in Gipuzkoa and Navarra. On that day in Bergara, fifteen kilometers from Ezkioga, electoral violence left several injured and one worker dead.[9]

R, "¡¡Aquí No!!" Adelante (Bilbao), 27 June 1931; ED, 30 June 1931.

It is no surprise that under these conditions on 29 June 1931, the day after the elections, a woman who had to stop her car because of a crowd on the highway near Ezkioga thought that some kind of political incident, or explosion, or assassination had taken place. But the crowd had gathered because a brother and a sister, ages seven and eleven, claimed to have seen the Virgin. The immediate and sustained interest in the Ezkioga visions showed that this was the right time and the right place for heaven to intervene in a big way.[10]

María Angeles Montoya, 11 September 1983. A priest from Zaldibia corroborated her; if they are correct, the Ezkioga visions began on 29 June 1931. At Mendigorría the authorities used the presence of children who saw nothing as an argument against the visions (PN, 9 June 1931, p. 3). At Ezkioga it was a measure of the eagerness with which people received the visions that a child who saw nothing was totally left out of the story (Felipa Aramburu, Zumarraga, 7 February 1986).

Ezkioga is a rural township of dispersed farms in the Goiherri, the uplands of the province of Gipuzkoa. In 1931 it had about 550 inhabitants. Almost all

lived on farms and spoke Basque. The town hall, the parish church of Saint Michael, and a government school were in a cluster of houses up the hill from the highway linking Madrid and San Sebastián. Down on the road there were two other small groups of houses, together known as Santa Lucía. The western group, nearer the town of Zumarraga, included a church and a school. The father of the original seers operated a store-tavern in the eastern cluster, and many pilgrims stayed in the Ezpeleta fonda there. The visions occurred on the hillside above these buildings.

How had the Second Republic affected the people of Ezkioga? One of the changes that most pained believers was the removal of crucifixes from schools and government offices. From April 1931 until the end of 1932 the government removed the crucifixes gradually throughout Spain. Manuela Lasa Múgica was the interim schoolteacher in the Santa Lucía barrio of Ezkioga from 1929 to early 1931. She came from the village to the east, Ormaiztegi, and shared the beliefs of her pupils and their families. And so, like her predecessors, she opened the day with a prayer, led the rosary on Saturdays, and celebrated the month of May with flowers and prayers. She kept a statue of Mary and a crucifix in the classroom. But in early 1931 she had to make way for the official teacher, an outsider who did not speak Basque. The community received the woman coldly, and she needed Manuela's help to find lodging. The government instructed the teacher to remove religious images from the classroom, she obeyed, and Manuela remembers people commenting that it was a shame that the children could not celebrate the month of Mary. The Republic thus represented a change for the children of the Santa Lucía, including the two future seers, just as it did for the entire region. Perhaps more so, for the schoolchildren were virtually illiterate in Spanish. Manuela Lasa taught mostly in Basque to students who would leave school at an early age.[11]

Norms in Gaceta, 22 May 1931, and El Debate, 23 May 1931, p. 2. In June, July, and August 1931 there was a rash of articles in Catholic newspapers on schools without crucifixes. In early 1932 women rebelled in Murchante, Estella, Lezaun, Viana, and Salinas de Oro in Navarra and Yécora in Alava (LC, 2, 7, and 9 February; PN, 20 April; CC, 27 April; Francisco Argandoña, Lezaun, February 1991); also towns in Palencia, Pontevedra, Almería, and Cuenca (El Debate, 23 March and 13 April; LC, 30 April). Women and children wore crucifixes that year after the Carta Circular of the exiled Bishop Múgica of March 12. See Heraldo Alavés, 21 April, p. 1; LC, 27 April, p. 8 (Zumarraga); LC, 29 April, p. 5. For Ezkioga, Manuela Lasa Múgica, 10 September 1983.

In the Basque Country and much of the north of Spain priests and religious were an integral part of the rural and small town population. Many of them came from the more prosperous farms. They shared a common outlook with peasants and those who worked in the factories of the company towns. And all higher education was then still religious education. The universities of the region were its seminaries and novitiates in Vitoria, Pamplona, and Loyola.

This devout rural culture bore one hundred years of suspicion toward the violent anticlericalism of Spain's cities and Spain's progressive governments. The antagonism dated at least from the first Carlist War and its aftermath. In 1833 the deceased king's brother, Don Carlos, rebelled against the liberal monarchy. Carlos promised to restore local liberties and the power of the church and to rule Spain as a consensual monarch of a loose confederation of regions. The stronghold of the Carlists was Navarra and the Basque Country. Enough priests and religious threw in their lot with him that liberals identified religious in general as subversives. This was one reason for the killing of religious in

Madrid in 1835. The governments that sold off church property also sold off the peasants' common lands. In the Basque Country Carlist peasantry and the rural clergy repeatedly clashed with the commercial and working people of the cities.

The last of the three Carlist wars ended in 1876, but the party lived on, a utopian, agrarian anomaly in a Spain that was rapidly modernizing. In 1888 a branch of Carlists broke away. They called themselves Integrists and they stood for a patriarchal society in which right-wing Catholicism, rather than the Carlist dynasty, was the guiding force. More papist than the pope, their strength was in the small town gentry and clergy of Navarra and the Basque Country. Their special symbol was the Sacred Heart of Jesus, but this symbol was shared with other militant Catholics.

The Carlists in their two branches cared about Spain as a whole. Basque Carlists were allies of others in Catalonia, Valencia, Castile, and Andalusia. The literature of the time often refers to them as Traditionalists. After 1920 their chief competitors for the votes of the peasantry were Nationalists. Basque Nationalism originated in the devout commercial class of Bilbao and gradually spread to the countryside and Gipuzkoa. The men of Ezkioga generally voted for Carlists or Integrists until 1919, when almost half voted for a Nationalist candidate. During the Republic the Nationalists gained new force.[12]

"Ezquioga," Enciclopedia general ilustrado del país vasco, 12:581-585.

Before the creation of the Second Republic the deputies representing the rural, Basque-speaking laity in the Cortes allied themselves with the monarchy; the governments of the monarchy by and large left the Basques and their traditions alone. But the Republic was different, and in the new parliament most Basque representatives were part of a small minority, which the Madrid press ridiculed as "cavemen" and "wild boars." The total lack of access to a government that rural Basques considered alien compounded their apprehension after the anticlerical violence in the rest of Spain.

Furthermore, this devout society lived cheek by jowl with another enemy—enclaves of Spanish-speaking, largely immigrant republicans, socialists, and anarcho-syndicalists in the company towns, river cities, and coastal capitals. Factories near Ezkioga in Beasain, Zumarraga, Legazpi, and Tolosa offered evidence of the shift in the economic base of the region from the agriculture of dispersed farmhouses to industry. Parish priests took on the difficult task of combating new ideas and morality with religious sodalities, sermons, and revival missions. They saw the new republic tipping the scales in favor of the long-term, ongoing encroachment of modernism.

Some of the new factories were paper mills. The tenant farm of Ezkioga where the two children had gone for milk on the night of the first visions belonged to an entrepreneur who later refused to rebuild his tenants' house when it burned down; instead he planted pine trees for his paper mill in Legorreta. Farm families were under siege, not only from the new republic and its schoolteachers but also

from industrial development. It can be no coincidence that the majority of the people who eventually had visions at Ezkioga were from the farms, not the towns or cities, of the Basque Country.[13]

Micaela Aramburu, Legazpi, 18 August 1982. For the industrial development see Castells, Modernización, and Greenwood, Unrewarding Wealth.

The appearances of the Virgin seemed to provide a solution to the great crisis. The first words she uttered (not to the original seers from Ezkioga but to a seven-year-old girl from Ormaiztegi and a twenty-four-year-old carpenter from Ataun) were in Basque, asking them, "Errosarioa errezatzea egunero [Pray the rosary daily]."[14]

LC, 9 and 10 July 1931; ED, 9, 11, and 15 July 1931.

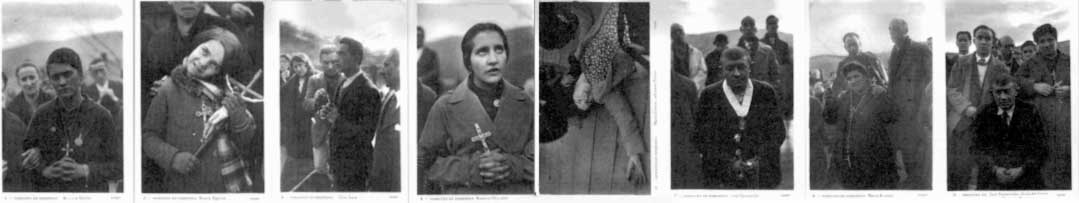

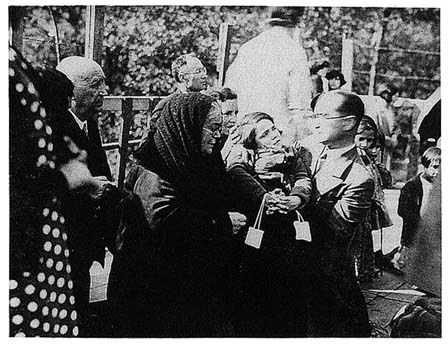

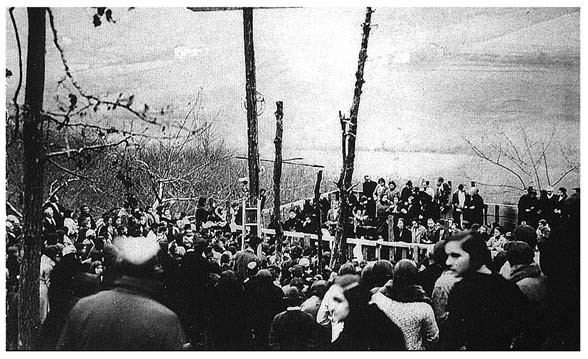

And pray the rosary people did, at night, on a hillside, often in the rain, on their knees, with arms outstretched during the Litany, while the seers waited for the visions to occur. First hundreds prayed, then within a week thousands. On the nights of July 12, 16, and 18 and October 16, up to eighty thousand persons turned out expecting miracles. In the first month there were over a hundred seers, and the visions continued in public, outdoor form until the fall of 1933. Seers at Ezkioga came especially from Gipuzkoa and within Gipuzkoa from the upland Goiherri; others came from the Basque-speaking villages of Navarra, and a few from Bizkaia, Castille, Catalonia, and the French Basque region. The visions soon spread out from Ezkioga, carried home by these pilgrims who had become seers and imitated by persons who read of the visions in the national press. Few Basques over seventy-five today did not go to Ezkioga then. It is possible that more persons gathered on that hillside on July 18 and October 16 than had ever gathered in one place in the Basque Country before.Tapping and Defining New Power: The Press and Local Leaders

The atmosphere of rural Gipuzkoa and Navarra in June 1931 was like a cloud chamber with air so saturated that even slight radioactive emissions become visible to the naked eye. Two children whose own father did not believe them when they said they had seen the Virgin immediately attracted two to three hundred observers. In the following days, weeks, and months, in this atmosphere, other visions by other children and by adults, visions we would not normally hear about, left their marks. The impressions on these seers' minds held immense potential importance for the Catholics of the Basque Country, Spain, and Western Europe of 1931. These strong impressions are still available sixty years later in the form of memories and printed accounts.

The visions offered Catholics a source of new power or energy—power to know the future and to know the other world of heaven, hell, and purgatory, power that could heal, convert, and mobilize the faithful. The crowds that converged on Ezkioga even before the news came out in newspapers showed how much people wanted this knowledge and this intervention. Calling this power new implicitly accepts the local definition of what was happening, the

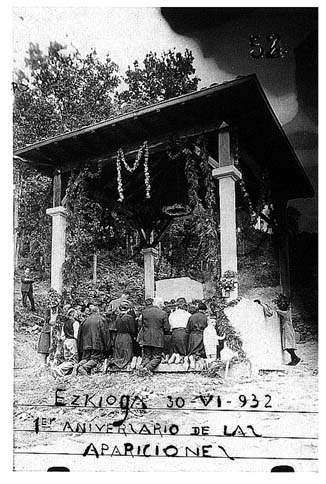

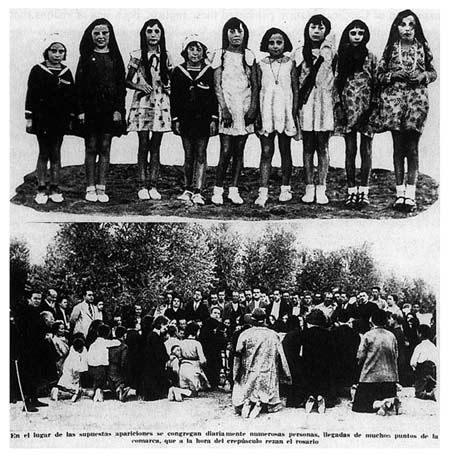

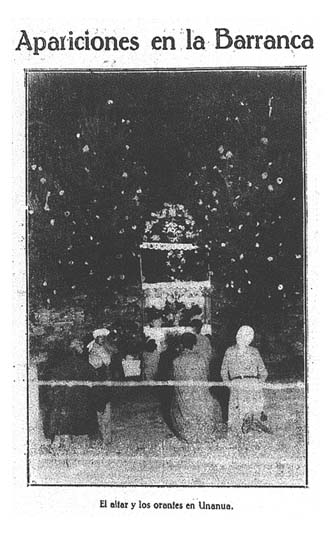

"The site of the apparitions." Crowd gathers on hillside, July 1931. Postcard sold by Vidal Castillo

truth of the divine appearances. But even believers would probably quality the idea that the power was new, because for them it would be a new version of a power very old indeed, the everyday power of God among them.

At Ezkioga this power was manifest in an unusual but hardly unique way. The Ezkioga parish church had bas-reliefs of Saint Michael appearing at Monte Gargano. Many Basque shrines had legends of apparitions. Lourdes was nearby, and well over a hundred thousand Basques had gone there and experienced firsthand the spiritual fruits of Bernadette's visions. The vision sites of Limpias (about a hundred kilometers northwest) and Piedramillera (about fifty kilometers south) were even closer. And Basque children knew about the apparitions of Fatima. The Ezkioga visions occurred during a period of enthusiasm within Catholicism in which the devout, in the face of rationalism, had come to believe that the old power was closer at hand, certifiable miracles were fully possible, and the supernaturals were easier to see.[15]

For apparition legends see Lizarralde, Andra Mari de Guipúzcoa and Andra Mari Vizcaya; Arregi, Ermitas de Bizkaia; López de Guereñu, Andra Mari en Alava; Peña Santiago, Fiestas; and Facultad de Teología, Santuarios. For Lourdes see Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 150, factoring in those who did not go on organized pilgrimages.

This kind of power came from the conversion of potential to kinetic energy. The potential energy lay in the Basques daily devotions, their normal attention

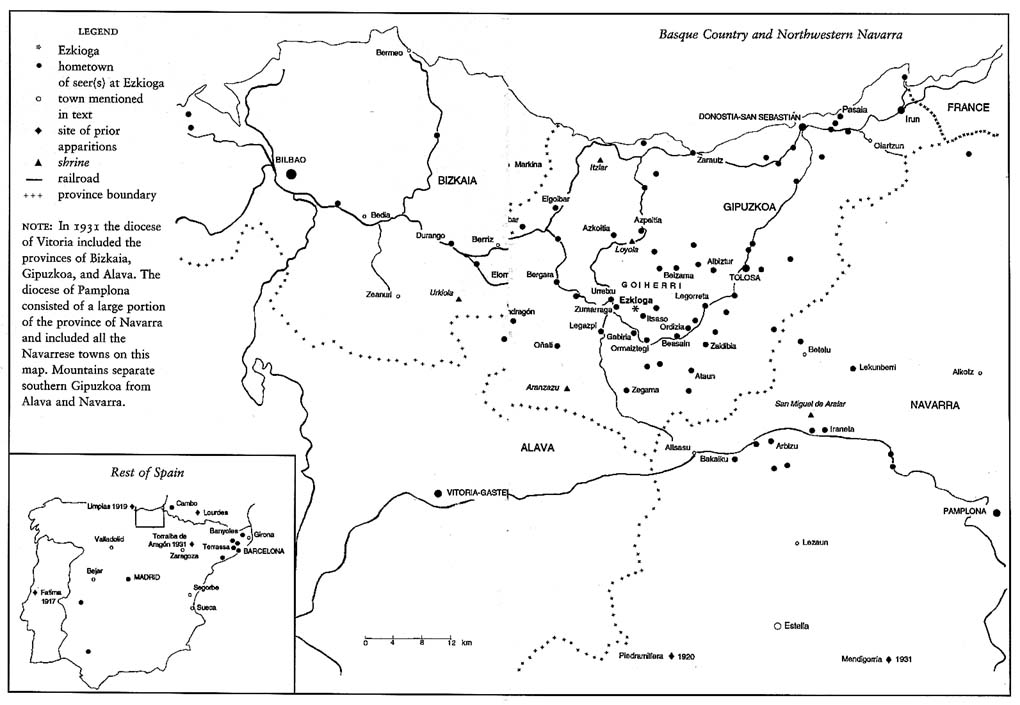

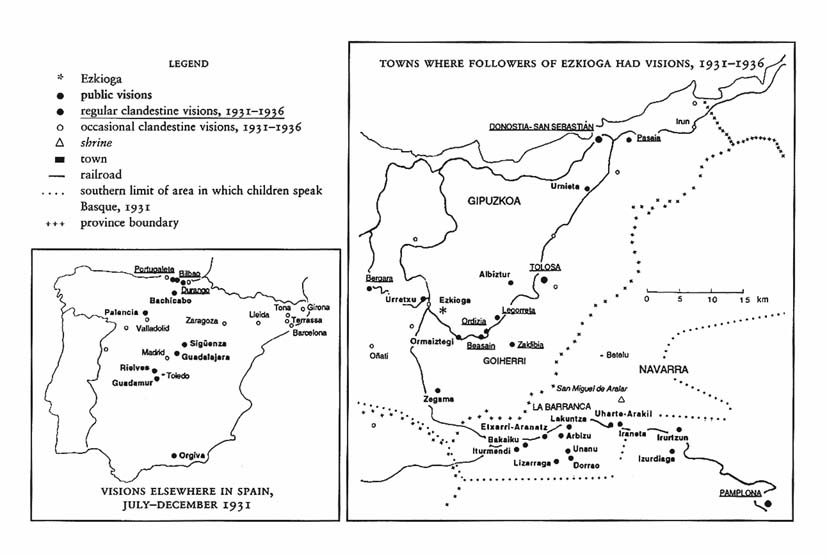

HOMETOWNS OF SEERS OF EZKIOGA AND TOWNS WHERE THERE WERE PUBLIC VISIONS

FROM 1900 UNTIL THE VISION AT EZKIOGA BEGAN ON 29 JUNE 1931

(map is on previous page)

to local, regional, and international saints. They deposited and invested this energy in daily rosaries, novenas, masses, prayers, and promises. They banked it through churches, shrines, monasteries, and convents. The church in its many representatives husbanded and administered it. The threat of the secular republic mobilized this accumulated devotional energy in the people of the north.

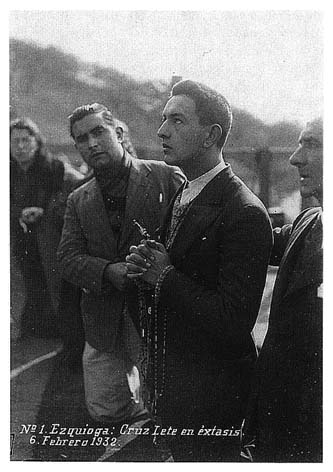

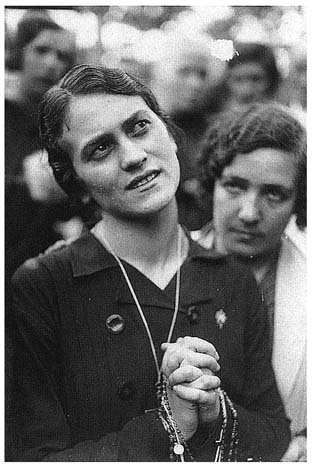

Tens of thousands of persons focused this power intensely on the seers. The seers were the protagonists, their stories and photographs in newspapers. Many of them seemed to feel in their bodies a tremendous force. Walter Starkie, an Irish Hispanist who wandered into Ezkioga and became for a few days in late July 1931 its one precious dispassionate witness, described a girl in vision as he held her:

I could feel the strain reacting upon her: every now and then a powerful shock seemed to pass quivering through her and galvanize her into energy, and she would toss in my arms and try to jump forwards. At last she sank back limp and when I looked down at her white face moist with tears I saw that she was unconscious.[16]

S 145.

As we will see, time and again beginning seers described blinding light and fell into apparent unconsciousness. The metaphor of great power was one that they themselves used. When they lost their senses, wept uncontrollably, or were blissful, they demonstrated this energy to observers.

How was this power tapped? Which visions made it into print and which are available only in memories? Who by controlling the distribution of news of the visions helped define their content? How did what the seers saw and heard come to address what their audience wanted to know?

The Basques and the Navarrese were more literate than most Spaniards. In 1931, 85 percent of Basques and Navarrese aged ten or older could read and write; the percentage was about the same for women as for men. The national average was 67 percent. Parents took elementary school seriously and teachers were important members of the community. This high rate of literacy ensured many avid readers for news of the Ezkioga visions.[17]

Ferrer Muñoz, Elecciones y partidos, 55.

For most Spaniards the news came largely from the reporters of the rightist newspapers of San Sebastián and Pamplona. In addition, the small-town stringers of these papers occasionally went to Ezkioga with busloads of pilgrims. Only on two occasions in July did writers for the more skeptical El Liberal of Bilbao go to Ezkioga, and there were no such eyewitness reports in the republican La Voz de Guipúzcoa .

The Basque newspapers covering the visions were those who had supported the winning coalition of candidates for Gipuzkoa in the Constituent Cortes, the parliament in Madrid that would draw up a constitution. La Constancia was the newspaper of the Carlists and Integrists; its deputy was Julio Urquijo. Two priests had recently founded El Día , the newspaper that reported the visions in greatest

detail. The Catholic press reprinted El Día 's stories throughout Spain. The newspaper was discreetly pro-Nationalist, with emphasis on news of the province of Gipuzkoa, and its deputy was the canon of Vitoria Antonio Pildain. The coalition candidates were selected in its offices. Euzkadi was the official organ of the Basque Nationalist Party, whose deputy was Jesús María de Leizaola. El Pueblo Vasco catered to the more worldly gentry of San Sebastián, and its deputy was its founder and owner, Rafael Picavea. The weekly Argia, which tended toward nationalism, went out to rural, Basque-speaking Gipuzkoa; it carried many reports on Ezkioga in 1931. News of the visions reached the public in these newspapers and their points of view affected the reporting. Even leftist newspapers depended on these sources.

While the newspapers reporting the visions were Catholic and broadly to the right, they did have some differences. The editor of La Constancia, Juan de Olazábal, was the national leader of the Integrists. In 1931 and 1932 this faction was in the process of rejoining the main Carlist party. The Integrists, "few but vociferous," had another organ in San Sebastián, the weekly La Cruz . The two factions were most powerful in Navarra, where they had two newspapers, the Carlist La Tradición Navarra and the Integrist El Pensamiento Navarro . In contrast to the readers of the Carlist and Integrist newspapers, the readers of Euzkadi, El Día , and Argia wanted an autonomous government that responded to the traditions, culture, and "race" of the Basques. For them the form of the Madrid government was immaterial, and they eventually allied themselves with the Republic and fought against the Carlists in the civil war of 1936–1939. But in 1931 the Basque Nationalist Party and the Carlists, the two main forces in the agricultural townships of the Goiherri and among the clergy of the diocese, stood together against the Republic. El Pueblo Vasco, whose Catholicism and Basque nationalism was somewhat more liberal, provided its readers with a more skeptical slant on the Ezkioga visions. While always respectful, its reporter occasionally pointed out inconsistencies and doubts. But in July 1931 its articles, some quite extensive, were largely factual.[18]

For the press see Cillán, Sociología electoral, 147-153, and Saiz, Triunfo; for Carlists and Integrists see Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis, 11 (quote), 46-67; for El Día especially interview with Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 11 September 1983.

In July and early August 1931 the three San Sebastián Catholic daily newspapers each had an average of two articles daily on the visions, usually naming visionaries and describing what they had seen and heard. They also carried background articles on trances, levitation, and stigmata and on the German stigmatic Thérèse Neumann, the Italian stigmatic Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, and the visions at Lourdes, Fatima, and La Salette. Ezkioga was a big story; only the campaign for a Basque statute of autonomy surpassed it in column inches. These newspapers served as a filter. Some news passed, some did not.

Between the reporters and the seers there was another filter, that of an ad hoc commission of the two Ezkioga priests, Sinforoso Ibarguren and Juan Casares; a doctor from adjacent Zumarraga, Sabel Aranzadi; the Ezkioga health aide and the mayor and town secretary. The doctor examined those seers who came

forward, and the priests asked questions that they eventually made into a printed form. By the end of July 1931 the commission had listened to well over a hundred persons, and because many persons had visions on more than one night, the total number of visions they heard about in that month was somewhere between three and five hundred. They sometimes allowed reporters to hear the seers and copy the transcripts. The doctor guided them toward the most convincing cases. The members of the commission encouraged some visionaries to return after future visions but dismissed others. The press and the commission tended to ignore adult women seers and heed adult men, comely adolescents, and those children who expressed themselves well (see questionnaire in appendix).

The seers themselves also participated in the filtering; some of them reserved what they saw for themselves or their families and did not declare their visions. This self-censorship particularly applied to the content of the visions. Seers were especially unlikely to declare unorthodox visions. For instance, one woman told others privately of seeing something like a witch in the sky. And a man from Zumarraga told me he saw a headless figure. He added, "Don't write that down; we all saw things there."[19]

Teresa Michelena, Oiartzun, 29 March 1983, said another woman spoke to her about the witch in the sky.

Similarly, two girls about seven years old had visions of an irregular sort in Ormaiztegi in late August and early September 1931. The father of one of the girls, a furniture maker, wrote down what they saw. On August 31 the girls said that they saw a monkey by the stream near the workshop and that two days before in the same place they had seen a very ugly woman. They then saw the monkey turn into the same woman, whom they called a witch; the witch said she understood only Basque. Directed by the father, who saw nothing, they asked the witch in their imperfect Spanish why she had come and from where. She replied, in Basque syntax and Spanish vocabulary, that she had come from the seashore to kill them. Later she supposedly ran up to the workshop and tried to attack the religious images the father was restoring.

On September 1 the two children saw the witch in the stream with a girl in a low-cut dress, short skirt, painted face, and peroxided hair who said she was "Marichu, from San Sebastián, from La Concha [the central beach]." The father made the sign of the cross and the girl disappeared, leaving the old lady, who made a rough cross in response. Later, both appeared again, coming out of the water together. The next day the Virgin appeared to the children together with figures representing the devil and temptation. The girls also saw a procession of coffins of the village dead.

These visions are a mix of Basque folklore and contemporary religious motifs, with a dash of summer sin. "Marichu" was a kind of modern woman counter-image to the Daughters of Mary. The newspapers might never have reported the Ormaiztegi visions if the church had approved the apparitions of Ezkioga. The reporter did not reveal this unorthodox vision sequence until after the tide had turned against the apparitions in general.[20]

Easo, 17 October 1931; PV and LC, 18 October 1931; Rodríguez Ramos, Yo sé, 16-22.

Such journalistic suppression seems to have been common in July, when the visions had great public respectability. Starkie provides an example from the village of Ataun of the kind of vision the newspapers did not report:

I met a visionary of a more sinister kind who assured me with a wealth of detail that he had seen the Devil appear on the hill of Ezquioga … "I saw him appear above the trees—tall he was, with red hair, dressed in black, and he had long teeth like a wolf. I wanted to cry out with terror, but I made the sign of the Cross and the figure faded away slowly."[21]

S 129.

Even mere spectators were aware that what others were seeing might not be holy but instead devilry or witchcraft. The word they used, sorginkeriak , literally "witch-stuff," reflected the ambiguous attitude toward the ancient subject, for it also had a looser meaning of "stuff and nonsense." Many priests preached that women should be retirado (indoors) after 9 P.M. ; thus, the woman who appeared at night on the hill was de mal retiro and going against the priests, something the Virgin would not do. This widespread opinion, more common among men, was also an indirect criticism of the women who stayed out late praying on the hillside. As long as the visions were respectable in the summer of 1931, the press rarely put such criticism into print.[22]

Miguel Zulaika, Itziar, 18 August 1982; J. M. de Barandiarán, Ataun, 9 September 1983; and P. Dositeo Alday, Urretxu, 15 August 1982: all reported the argument in 1931 against the visions. Masmelene, EZ, 15 July 1931, and Larraitz, ED, 28 July 1931, made it in print. Masmelene was a student of Barandiarán, and Larraitz one of the founders of the pro-republican Acción Nacionalista Vasca.

A third kind of distortion or molding affected the orthodox visions when certain messages were emphasized over others. The allocation of attention was the business of every person who when to, talked about, or read about the visions. In a gradual collective selective process, the Catholics of the north focused on the messages they wanted to hear. We can follow this process day-to-day through the press.

The first visions of the first seers were of the Virgin (they had no doubt who it was) dressed as the Sorrowing Mother, the Dolorosa. The image appeared slightly above ground level, and the visions were at night. Sometimes the Virgin was happy, sometimes sad, but her emotions were the "content" of the visions. On July 4 others began having visions, and during the rest of July newspapers described over two hundred of the visions in which the Virgin's wishes became more explicit. Some visionaries told how the Virgin reacted to her surroundings, to the audience, or to the prayers. Some saw the Virgin as part of allegorical tableaux. Others saw her move her lips. And starting on July 7 still others heard her speak. Visions involving acts, such as cures or divine wounds, developed only in later months.[23]

LC, 7 July 1931; PV, 10 July 1931.

The rosary, a fixture of the gatherings, began on the third day of the visions. During and after the rosary the audience engaged in a kind of collective blind dialogue with the holy figure through the seers: on the one hand, the prayers and Basque hymns; on the other, the seers communicating the Virgin's emotions and attitudes. The Virgin was alternately sad, weeping, sad then happy when she heard the prayers, and happy. She sometimes participated in the prayers and

hymns, said good-bye, and even threw invisible flowers. Mute glances, reproachful looks, sweating, and an occasional smile had been the main—indeed the only—content of the miraculous movements of the crucifixes of Limpias and Piedramillera.

People also deduced Mary's emotions and mission from her dress, which was mainly that of a Dolorosa with a white robe and black cape (the commission took care to establish her apparel and how many stars there were in her crown), but sometimes she came as the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of Aranzazu, Our Lady of the Rosary, or other avatars. Some seers saw one Mary after another in rapid succession.

The communication between the Virgin and the congregation was the central drama of the Ezkioga visions in the first month, but there were other vision motifs. Visions predicting a divine proof of the apparitions earned particular attention. From July 10 there were reports of an imminent miracle. Seers' predictions overlapped, so when one miracle did not occur, people's hopes shifted to another. A rumor circulated that a very holy nun—some said from Bilbao, others said from Pamplona—had predicted on her deathbed that in a corner of Gipuzkoa prodigious events would take place on July 12. On the day before that date the carpenter Francisco "Patxi" Goicoechea of Ataun had a vision in which the Virgin said that time would be up after seven days. People understood this statement variously to mean that the miracle would take place on the sixteenth or the eighteenth. On July 12 an article appeared in El Día drawing parallels between Ezkioga and Lourdes and raised hopes for a miracle in the form of a spectacular cure. On the fourteenth Patxi again referred to a time span (un turno ) elapsing, and an eleven-year-old boy from Urretxu heard the Virgin say that she would say what she wanted on the eighteenth. On the twelfth and sixteenth of July there were massive audiences of hopeful pilgrims. The newspapers reported hundreds of seers on the twelfth, but on neither day was there a miracle of any kind. On the seventeenth the Zumarraga parish priest told a reporter he would rather talk the next day: "Let us see if tomorrow, Saturday, the Virgin wants to work a miracle; perhaps something startling and supernatural, as at Lourdes, will be a revelation for us all. Maybe a spring will suddenly appear, or a great snowfall."[24]

All 1931: for nuns, La Tarde, ELB, and PV, 11 July; "Ormáiztegui," PV, 17 July; priest in PV, 18 July.

The Zumarraga priest's hopes in print set the stage for a day of record attendance on July 18, which the press estimated at eighty thousand persons. But the day before, Ramona Olazábal, age sixteen, was already setting up new expectations because the Virgin had told her that she would appear on the following days. No miracle occurred on the eighteenth. But Patxi heard the Virgin say she would work them in the future, and a girl heard her say that she would not show herself to everyone because people were bad; so hope for a miracle continued. On July 23 Ramona heard the Virgin affirm that she would work

miracles in the future; on the next day there was a story that another nun, this one living, had announced great events in 1931; and on the following day a servant girl from Ormaiztegi announced that the Virgin "wanted to do miracles."[25]

All 1931: seer, aged 16, ED, 18 July; predictions on the eighteenth, ED and PV, 19 July; Ramona, PV, 24 July; nun, LC, 24 July; servant, ED, 26 July.

When Starkie was in Ezkioga, around July 28, he found local people and outsiders in a kind of suspense, waiting for a sign. On July 30 the Virgin, ratifying what most persons had already concluded, declared through Ramona that "miracles were not appropriate yet."[26]

ED, 31 July 1931.

By then the seers had worn out their audience, which declined to a few thousand persons and on some days to a few hundred, until Ramona herself became the miracle in mid-October.Visions Relating to the Collective Religious and Political Predicament

The political-religious problems of 1931, which seem to have determined the immediate positive response to the visions, were not only pressing but also collective in nature, so help from the Virgin had to be collective as well. The Elgoibar correspondent in El Día of July 18 called for a message addressed to the Basques: "Let the Mother of Heaven make her decisions manifest, for we her sons in Gipuzkoa are prepared to carry them out." Already a month and a half before the visions began, La Constancia had laid out the collective plight:

Difficult times, times of trial, sorrowful omens; disquieting doubts, bitter disillusions, anguished fright, ears and eyes that open to reality, at last.

What is happening? What is going to happen?

And in this disarray, with spirits cowed, the mind goes blank, confusion grows, and the already general malaise spreads.

The writer also proposed a solution: "We must turn our eyes to God and to our conscience and begin a crusade of prayer, fervent persevering prayer; and a crusade of penance and atonement." Three weeks before the visions started the Bergara correspondent of the same newspaper made a similar analysis:

The simple and plain folk have understood that we are in the midst of a sea of dangers, that the hurricane wind tells us that we are two steps away from the most terrible storm, from which we will hardly be able to emerge without divine help; and in sacrifice they have gone to the feet of the Virgin to pray for Spain, the Basque Country, and for the town.

At Ezkioga the Basque people "turned their eyes to God" and went "to the feet of the Virgin" to pray for collective help in a way perhaps more literal than these writers expected but in a way they and others had already marked.[27]

Junípero, "Oración y penitencia," LC, 15 May 1931; LC, 5 June 1931, p. 8.

The first hint that the visions would address this need came in the Bilbao republican paper El Liberal on July 10. The correspondent from Elgoibar reported: