Georgetown, Washington, D.C.:

The Catalytic Reaction Does Not Damage Its Context

In addition to preserving and enhancing elements of value in a project area, urban catalysts treat their contexts with care—in striking contrast both to bulldozer techniques that clear entire areas and to unmoderated changes. Instead, selective demolition and renovation knit new developments into the existing urban fabric. Figure 38 shows how new and renovated buildings have been interwoven.

60.

Historical character of Georgetown.

61.

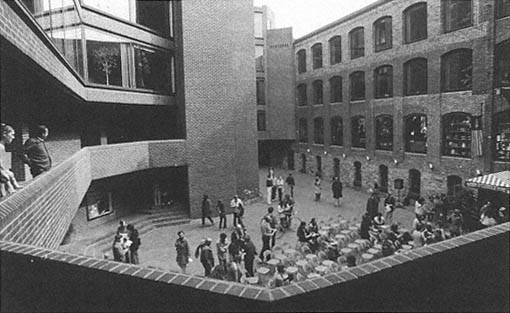

Canal Square, Georgetown, Arthur Cotton Moore / Associates, architects, 1971. This complex

set a standard for subsequent design. It retained the character and scale of street frontages

while inserting a respectable modern building within the block. The development makes

connections to the C&O canal with a restaurant deck, to historic Georgetown in the

selection of materials, and to the pedestrian web with a "town square."

Georgetown was a port that blossomed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For years it remained a backwater, its residences principally Georgian, its other structures industrial or Victorian. By the twentieth century its waterfront had declined though its residential areas were gradually being reclaimed and refurbished. A Georgetown address began to carry status for residences, though along the Potomac River and Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad canal an industrial slum developed.

Until the early 1970s the few new structures built in Georgetown emulated Colonial styles: brick boxes with regularly spaced double-hung windows, shutters, and occasional ornamental porches. Beginning in the 1970s the potential of the industrial area became evident, and for the most part the approach of architects and developers and those who review their designs has been to build sympathetically but without historicizing pastiche. The pedestrian experience and the pedestrian scale have been important considerations in revitalizing Georgetown.

Canal Square

The first significant deviation from this pattern of mock-Georgian building in Georgetown was Canal Square. While decidedly un-Colonial, it paid sufficient attention to its context to establish a precedent for contemporary architecture in Georgetown. It connected

62.

Canal Square in its context and some of the subsequent context it engendered.

© Arthur Cotton Moore / Associates.

with an existing stone warehouse, demonstrating the value of reusing existing industrial buildings in new ways. It retained the scale of Georgetown and used materials sympathetic to Georgetown's character. Canal Square established a new precedent for the locale in site planning as well in creating a semipublic space at the interior of a block. Its program was mixed: specialty-retail and office uses.

Although Canal Square generated controversy for deviating from Georgetown traditions, its sympathetic design response to the context was recognized by local authorities, who gave the necessary approvals. It became an architectural catalyst as well as a precedent-setting economic development, demonstrating that office and retail developments were marketable in the area between M Street and the Potomac River. Equally important, it demonstrated that new development need not damage this fragile historical context. Canal Square set a standard and offered suggestions for other architects and developers who might follow, suggestions for a controlled yet still profitable response to context.

The Foundry

Taking cues from Canal Square, the Foundry features an existing industrial building, dating from 1856, reclaimed and tied to a new office and retail structure, using similar materials but in a contemporary style. The tone of the new structure is conditioned by the existing foundry and its Georgetown context, yet it is crisp, efficient, and modern. Together the structures create a semipublic space associated with the C&O Canal. Respectful restraint is evident throughout the complex. The new structure steps up gradually from the two-storey historic foundry, ultimately reaching six storeys. The diagonal wall of the office wing helps to define the plaza and permits sunlight to reach it. Fenestration patterns are adjusted to context, with large glass openings facing the interior of the site and smaller window modules, based on historical townhouse traditions, facing neighboring streets. The glazed mansard roof (on the street side of the building, not visible in Figure 63), is a familiar local form. With this strategy the architects and the developer hoped to prove "that excellent architectural design and careful consideration of the environment are basic to a fair return." Even within a few months they were satisfied that the building, "with all that has been going on around it and in it, looks like it has already been in Georgetown quite a while. I would say that is a very fair return, for everyone."[6]

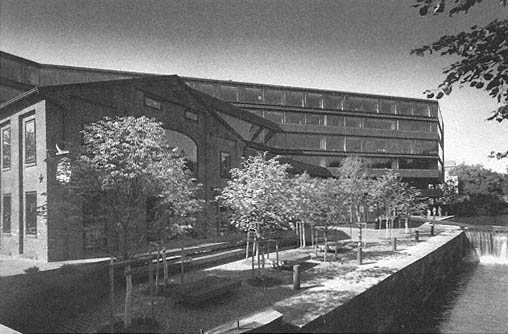

63.

1055 Thomas Jefferson (the Foundry), Georgetown, by Arthur Cotton Moore / Associates

and ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects, 1977.

Photograph by Ronald Thomas.

Critical reaction was appreciative of the effort to defer to the setting: "The new neighbor on Thomas Jefferson Street has not only accommodated the history of Georgetown, it is making some . . . people realize that new construction, stirring new uses in among what already exists, can reveal the scale, texture, and character of a community in a telling, enjoyable manner."[7]

These two projects set off south of M Street a controlled chain reaction of commercial and residential building that was even more dramatic than in Milwaukee and Kalamazoo, a reaction that has both transformed and renewed an area that might well have been neglected or obliterated in other cities. The whole history of revitalization in Georgetown offers several lessons:

1. "Controlled reaction" does not mean that the architect is bound by narrow stylistic constraints. The Georgetown context offers at least three building traditions that architects have been able to reshape to more contemporary taste: Georgian, Victorian, and industrial vernacular. SOM's Four Seasons Hotel and Jefferson Court office building refer to different traditions (Georgian and Victorian) yet are rendered in a similarly straightforward way.

2. Although one might hope that all architects would understand a district's inherent chemistry, this is unlikely, so external controls in the form of design review are needed. In the case of Georgetown, several review bodies must approve designs. Whereas design review is often con-

64.

Georgetown, showing the addition of new structures within the grain of the town. Size, scale, and

preserving the sense of a pedestrian web are key qualities in sympathetic additions to Georgetown's

traditional fabric.

65.

Four Seasons Hotel, Georgetown, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects, c. 1980.

66.

Jefferson Court, Georgetown, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects, 1985.

servative, in Georgetown the Federal Fine Arts Commission has recognized that because waterfront buildings tend to be large, it would be a mistake to insist upon the strict historical styling associated with small structures and far better to seek designs that harmonize with, rather than imitate, the setting.

3. Contemporary needs and preferences can be accommodated even within the limits of a particular architectural or urban design setting. For example, the desire for informal semipublic spaces both indoors and outdoors has been satisfied even though the local Georgian tradition emphasized the street as a public realm. Similarly, larger windows, provision for parking, and other contemporary preferences have been included in new structures that nonetheless retain an overall sense of architectural and urban coherence.

The Georgetown case demonstrates that seminal developments like Canal Square and the Foundry can release and guide a chain reaction (rule 1), that existing buildings need not be destroyed (rule 2), and that the reaction need not be harmful to the context as a whole but can be contained while still allowing room for imagination and change (rule 3).