Stepin Fetchit Talks Back

Joseph McBride

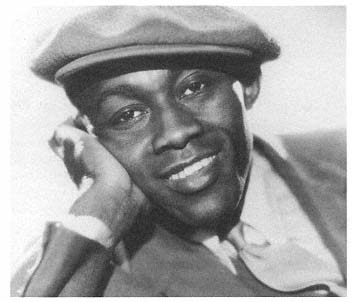

Stepin Fetchit (sometime in the 1930s).

Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Vol. 24, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 20–26.

To militant first sight, Stepin Fetchit's routines—all cringe and excessive devotion—seem racially self-destructive in the rankest way, and his very name can be a term of abuse. And yet, in looking at his performances (for instance as the white judge's sidekick and looking-glass in Ford's The Sun Shines Bright) cooler second sight must admit that Stepin Fetchit was an artist, and that his art consisted precisely in mocking and caricaturing the white man's vision of the black: his sly contortions, his surly and exaggerated subservience, can now be seen as a secret weapon in the long racial struggle. But whatever one makes of Stepin Fetchit's work, he was one of the few nonwhites to achieve status in American films, and he deserves to be remembered .

Like all American institutions, Stepin Fetchit is having a hard time these days. The legendary black comedian, now 79 years old but looking decades younger, has found himself a target of ridicule from the very people he once represented, almost alone, on the movie screen. A revolution has erupted around him, and he has been cast not in the role of liberator (as he sees himself), but as a guard in the palace of racism. The man behind the vacant-eyed, foot-shuffling image is Lincoln Perry, a proud man embittered by scorn and condescension.

Once a millionaire five times over, he now lives modestly in Chicago and takes an occasional night club gig. He hasn't acted in a movie since John Ford's The Sun Shines Bright in 1953, though he appeared in William Klein's documentary about heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali, Cassius le Grand , while acting as Ali's "secret strategist" during the Liston fights. Perry once served in a similar capacity for Jack Johnson, and Ali's gesture of kinship has given a massive boost to the comedian's self-esteem.

I encountered him in a garish bottomless joint in Madison, Wisconsin, on the night of Ali's fight with Oscar Bonavena. Before we talked, I sat down to watch his 20-minute routine, which was sandwiched on the program between Miss Heaven Lee and Miss Akiko O'Toole. Audiences at these Midwestern

nudie revues behave like hyenas in heat, but there is one very beautiful thing about a place like this, and I mean it: nowhere else in America today will you find such a truly democratic atmosphere. Class distinctions vanish as hippie and businessman, hard-hat and professor, white and black and Indian and Oriental unite in a common impulse of animal lust. Women's liberationists would object, of course, but not if they could observe the audience at close range—Heaven Lee had us enslaved.

When Step appeared, in skimmer and coonskin coat, there was a wave of uneasy tittering, and his first number, an incomprehensible boogie-woogie, stunned the audience into silence. What's this museum piece doing out there? Better he should be stored away where we can't think about him. But as he launched into his routine, a strange thing happened. Slowly, gradually, people began to dig him. Stepin Fetchit is, first and last, a funny, funky man. It isn't that his jokes are so great (a lot of them were tired-out gags about LBJ, of all people), it's the hip way he plays them. What made Step and Hattie McDaniel outclass all the other black character actors of bygone Hollywood was their subtle communication of superiority to the whole rotten game of racism. They played the game—it was the only game in town—but they were, somehow, above it: Step with his otherworldly eccentricities and Hattie McDaniel with her air of bossy hauteur . A tableful of young blacks began to parry back and forth with Step as he talked about the South. "You know how we travel in the South?" "No, how we travel in the South?" "Keep quiet an' I tell you." "That's cool. That's cool." And Step drawled: "Fast. At night. Through the woods . On top of the trees ." The irony may have been a shade too complex for the rest of the audience, but everybody understood when he laconically gave his Vietnam position—"Flat on the ground"—and explained the situation of the black voter: "Negroes vote 20 or 25 times in Chicago. They don't try to cheat or nothin' like that. They just tryin' to make up for the time they couldn't vote down in Mississippi. When you in Mississippi you have to pass a test. Nuclear physics. In Russian. And if you pass it, they say, 'Boy, you speak Russian. You must be a Communist. You can't vote.'"

Out flounced Akiko, and we went downstairs to a dusty storage area which had been hurriedly transformed into a dressing room. Stepin Fetchit may be funny, but Lincoln Perry isn't. "Strip shows are taking over everything," he lamented. "You're either at the top or you're nothing." The stage he was using, a rectangular runway, forced him to turn his back on half of the audience, and he was trying to improvise a new means of attack. (It was sad and strangely appropriate that the lighting was so bad he had to carry his own spotlight around with him.) His heart, moreover, was with Ali. "That's where I should be, with that boy," he said. Jabbing his finger and circling me like a bantamweight boxer, Perry quickly turned the interview into a monologue.

Under a single swaying light bulb, the sequins on his purple tuxedo flashing, he moved in and out of the shadows like a restless ghost. I began to get the eerie feeling that I was serving as judge and jury, hearing the self-defense of a man accused of a cultural crime. This is what the man said:

I was the first Negro militant. But I was a militant for God and country, and not controlled by foreign interests. I was the first black man to have a universal audience. When people saw me and Will Rogers together like brothers, that said something to them. I elevated the Negro. I was the first Negro to gain full American citizenship. Abraham Lincoln said that all men are created equal, but Jack Johnson and myself proved it. You understand me? I defied white supremacy and proved in defying it that I could be associated with. There was no white man's ideas of making a Negro Hollywood motion picture star, a millionaire Negro entertainer. Savvy? I was a 100% black accomplishment. Now get this—when all the Negroes was goin' around straightening their hair and bleaching theirself trying to be white, and thought improvement was white, in them days I was provin' to the world that black was beautiful. Me . I opened so many things for Negroes—I'm so proud today of the things that the Negroes is enjoying because I personally did 'em myself.

People don't understand any more what I was doing then, least of all the young generation of Negroes. They've made the character part of Stepin Fetchit stand for being lazy and stupid and being a white man's fool. I never did that, but they're all so prejudiced now that they just can't understand. Maybe because they don't really know what it was like then. Hollywood was more segregated than Georgia under the skin. A Negro couldn't do anything straight, only comedy. I did more acting as a comedian than Sidney Poitier does as an actor. I made the Negro as innocent and acceptable as the most innocent white child, but this acting had to come from the soul . They brought Willie Best out there to make him an understudy for me. And he wasn't an actor, he wasn't an entertainer or nothin' like that. I didn't need no understudy, because I had a thing going that I had built my own. And the worst thing you'll hear about Stepin Fetchit is when somebody tries to imitate what I do, the first thing they're gonna say is "Yassuh, yassuh, boss." I was way away from that.

Do I sound like an ignorant man to you? You made an image in your mind that I was lazy, good-for-nothing, from a character that you seen me doin' when I was doin' a high-class job of entertainment. Man, what I was doin' was hard work! Do you think I made a fool of myself? Maybe you might want me to. Like I can't be confined to use the word black. For a comedian, that takes the rhythm out of a lot of jokes and things. So when I use the words colored and Negro I'm not trying to be obstinate. That's what I'm going around for—to show the kids there are a lot of people that's doin' things to confuse them.

I'm just trying to get the kids today to have the diplomacy that I had to when I was doing it, and I think they'll come out first in everything. I didn't fight my way in—I eased in.

Humor is only my alibi for bein' here. Show business is a mission for me. All my breaks came from God. You see, I made God my agent. Like it's a coincidence that I'm here talking to you now. They bring a lot of people here, they pay 'em to talk to these students. They teachin' these students to go against law and order, they teachin' 'em to go against God, against their country, and they're payin ' 'em. They wouldn't pay me to come to town to talk to the students. Are you one of these college boys? No? That's good. All these college boys, the first word they think of when they write about me is Uncle Tom. I was lookin' for the word to come up but it didn't. Uncle Tom! Now there's a word that the Negro should try to wipe out and not use. Uncle Tom was a fictional character in a story that was wrote by Harriet Beecher Stowe. And Abraham Lincoln said that this thing was one of the propaganda that put one American brother against his other.

Kids is eccentric. They think they want to hear all these eccentric things. Like I see beautiful kids—I went to a place near where I'm working called the Shuffle and the reason they're using all this long hair and these whiskers, looking like apostles, that's because they're leanin' towards God, instinctively. Good kids, and a lot of old men is foolin' 'em. I want to let 'em know how I as a kid, a small Negro kid that was a Catholic too—so I had eleven strikes against me in them days—became a millionaire entertainer. Now these kids, they think that I'm unskilled and I'm uneducated, you know, and I don't have no diplomas or anything like that. But they must remember that they're listening to 79 years of experience.

I was an artist. A technician. I went in and competed among the greatest artists in the country. When I was about to make a movie with Will Rogers, Lionel Barrymore went to him and said, "This Stepin Fetchit will steal every scene from you. He'll steal a scene from anything—animal, bird, or human being." That was Lionel Barrymore , of the Barrymore family!

John Ford, the director, is one of the greatest men who ever lived. We was at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1929 making a picture called Salute , using the University of Southern California football team to do us a football sequence between the Army and the Navy. John Wayne was one of their football players. And in order to be seen by the director at all times, because Ford wanted to make him an actor, John Wayne taken the part of a prop man. That director made him a star. And on that picture, John Wayne was my dresser! John Ford, he was staying in the commandant's house during that picture, and he had me stay in the guest house. At Annapolis!

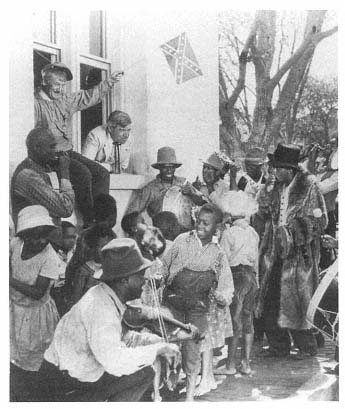

I was in Judge Priest , that Ford did with Will Rogers in 1934. Did you see that? Well, remember that line Will Rogers says to me, "I saved you from one

Stepin Fetchit (on right, with coonskin coat) as Jeff Poindexter in

John Ford's Judge Priest (1934).

Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

lynching already"? We had a lynching scene in there, where I, as an innocent Negro, got saved by Will Rogers. They cut it out because we were ahead of the time. In 1953 we did a remake of that picture, called The Sun Shines Bright . And John Ford, he did the lynching scene again. This time the Negro that gets saved was played by a young boy—I was older then. But they kept it in. That was my last picture.

I filed a $3 million lawsuit against something that Bill Cosby said about me in a show called Of Black Americans . But I didn't make Cosby a defendant. Know the reason why? Because that's not the source of where the wrong come. It's CBS, Twentieth Century–Fox, and the Xerox Corporation, the men that sponsored it, that's responsible for distortin' my image. Cosby was just a soldier. He was not a general. I know all the black comedians. Bill was the onliest one I hadn't met. I met him for the first time in Atlanta at the Cassius Clay–Jerry Quarry fight. Cassius called me and say, "Hey, Step, I want you to meet Bill." I just said hello, because I was busy, and then he said, "Bill Cosby! " I went back and I say, "Well, Cosby, I hope that you help to put a happy ending to my damages that has been

done." He says to me, "Yeah, I told my wife, I hope that you win this suit, because it was taken out of context." Cosby's a great comedian, but for the educated classes. Savvy? A few years ago he wouldn't have been able to be where he is—I was the one who made it possible for him. The worst thing in America today is not racism. It's the way the skilled classes is against the unskilled classes. You understand me?

Now, if we don't get this country straight, your next president is going to be George Wallace. They figure everybody is being turned idiot and they gonna all agree it's gonna be a man like George Wallace to help our problems if we don't straighten them out ourselves.

Ain't but two things in the world today. That's good and bad, right and wrong. Now if we follow everything down to them two things, and we are either on one of them sides, it ain't no white, no colored, no Black Panthers, no Ku Klux . . . we either for good or for bad! We ought to have a National Association for the Advancement of Cre ated People and not think about each nationality that represents 50 percent of America. When God made Adam, he didn't make all these different nationalities. Man did it. There is no mules in heaven. Now let me explain this to you. Mules are man-made, made from crossing a jackass with a horse. So when man got mixed up, it wasn't the work of God, it was the work of man. Racism? Remember when there wasn't but four people on earth, Cain killed his brother Abel and started unbrotherly love. God didn't have nothin' to do with unbrotherly love.

To show you how fate works—Cassius Clay, none of these great liberals would touch him and give him a chance to fight again. And who do you think give him a chance to fight again? Senator Leroy Johnson of Georgia, a man that is associated with Lester Maddox . Without Lester Maddox, Cassius Clay wouldn't have fought today, although the image they gave to you was that Lester Maddox was against it. You get the idea? You understand me? The greatest example of Americanism was shown to Cassius Clay by a proxy, through Lester Maddox! That's the way the world is running. So let's face these things right, not like we pitchin' things, or like we want it to go. God's gonna work in a mysterious way! We have had men supposed to be great all down the line—Alexander, Moses—and we still found the world all messed up. Ain't nobody in good shape. Ain't nobody got no sense or nothin'.

It was Satchel Paige that opened the major leagues to the Negro ball players. Not Jackie Robinson. No suh! Satchel Paige did the dirty work. He used to go and play in counties where they didn't allow a Negro in the county. He did the good work—what I did—made good will and good relations. Jackie Robinson was the politician, you understand me, the skilled one that walked in and got the benefits. Satchel Paige broke down the whole deal and hasn't got credit for it yet, just because he was unskilled labor. He was 100 years ahead of his time, like I am, like Johnson was.

The reason why Cassius sent for me was because he found out that I was the last close intimate of Jack Johnson. Jack told me a lot of things. Cassius always said they wasn't but one fighter that was greater than him, and that was Jack Johnson. And so he wanted to know everything about him. He got me in and he would ask me all the different things that Jack would tell me about. I taught him the Anchor Punch that he beat Liston with—that was a punch that Jack improvised. Cassius dug up some pictures of Johnson and I told him about this out-of-sight punch that Jack Johnson said he had. He said he could use it any time he wanted on Willard. See, Willard did not knock Johnson out. Johnson sold the heavyweight champion of the world for $50,000. Johnson accepted $15,000 in Europe and told them to give his wife $35,000 at ringside. He wanted the heavyweight champion title to belong to America. They had ran Jack into a lot of things, you get the idea . . . be too long to talk about.

They promised him with the $15,000 they would wipe off this year that he's supposed to serve. But they didn't do that, so he came back and served the year himself. You get the idea? I saw that play, The Great White Hope . I think it's terrible as far as telling the truth about Jack Johnson. It's not about Jack. Jack Johnson had noble ideas. They had him beating this girl—Jack never did a thing like that. And they showed where he was defeated and knocked out, but they didn't show that he sold out the heavyweight champion and that he wanted the championship to belong to America.

We were going to do this picture of his life story, called The Fighting Stevedore . You know—from Galveston, Texas, where he used to be a stevedore. While we was waiting to write the story—we was making it just for colored theaters, in them days things weren't integrated and the big companies wouldn't want to buy it because everything had thumbs down on Jack Johnson like things tried to be with Cassius, although I'm sure Cassius is coming out of it—while we was waiting to write this thing, we sent Jack down to lead the grand parade of Negro rodeos in Texas. That was the trip he got killed on. I booked him on it.

I always call Cassius "Champ" because I used to call Jack Johnson "Champ." The way Jack and me met, we was both celebrities, and I used to sit in his corner when we was fighting. We became friends especially when he found out that the same priest had taught both of us. His name was Father J. A. St. Laurent. He taught also the Negro student that became the first Negro Catholic priest in America. Here's a picture of me preachin' to Martin Luther King. I was telling him that I was in Montgomery, Alabama, before he was born playing with white women. This priest was the head of the school I went to, St. Joseph's College. It was a Catholic boys' school. And this priest used to have the nurses come from St. Margaret's Hospital to play with us—that's where Mrs. George Wallace was a patient before she died. They had picnics, spent a

whole day on our campus with these colored boys, playing ball with us, eating in our dining room, and things like that. This priest he taught us a technical education—Tuskegee used to teach manual labor—and so he left those boys with something. We had no inferiority complex. Jack always wanted to show that all men were created equal, so he goes into Newport News society and married a white woman out of the social register, a blue-blood!

My father named me Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry. Told me he named me after four presidents—he think I'm gonna be a great man. But I can't see how in the world he named me after Theodore Roos evelt. He wasn't even president yet! I was born in 1892—here's my birth certificate—in Key West, Florida, the last city in the United States. I'm a descendant of the West Indies. My mother was born in Nassau, my father was born in Jamaica. I had talent all my life—my father used to sing. He was a cigar maker. I got in show business in 1913 or '14. The people who had adopted me and sent me off to this school, something happened to them, and so this priest told me I could work my way through school. In summertime he let me go to St. Margaret's Hospital to work. When time to go back to school, there was a carnival that used to winter in Montgomery. Turned out to be the Royal American Shows. So I joined it, joined the "plantation show." The plantation shows started to call themselves minstels, but minstrels was white men made up. Plantation shows was black men made up.

I got my name Stepin Fetchit from a race horse. The plantation show minstrels, we went down in Texas and there was a certain horse we used to go and see at the fair. We knew these races because they went to the same fairs as we did. There was a horse that we knew would never lose, so we would go out and give the field and the odds. Well, people thought we was crazy—he would always win. But one day they entered a big bay horse on us, and he won. We went and grabbed the program, looked, and it was Stepin Fetchit, horse from Baltimore. And so I goes back to show business in Memphis, and hear "Stepin Fetchit! Stepin Fetchit!" from everyone. I wrote a dance song of it called "The Stepin Fetchit, Stepin Fetchit, Turn Around, Stop and Catch It, Chicken Scratch It to the Ground, Etc."

Me and my partner was introducing this new dance. We were Skeeter and Rastus, The Two Dancing Crows from Dixie. Jennifer Jones's father booked us in a white theater in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was unusual. And in place of putting our names Skeeter and Rastus, he put Step and Fetchit and he made that our names. When my partner, he wouldn't show up, I would tell the manager, "No, it's not two of us, it's just one of us, the Step and Fetchit." And then I'd go out and do just as good as the two of us. I fired him, since I had wrote the song, see, and in place of The Two Dancing Crows from Dixie, I was the Stepin Fetchit. I got the lazy idea from my partner. He was so lazy, he used to call a cab to get across the street.

I was in Ripley's "Believe It or Not" as the onliest man who ever made a million dollars doing nothing. Anything money could buy, I had. I had 14 Chinese servants and all different kinds of cars. This one, a pink Rolls Royce, it had my name on the sides in neon lights. My suits cost $1,000 each. I got some of them from Rudolph Valentino's valet after he died. I showed people that just because I had a million dollars, the world wouldn't come to an end. But then I had to file a $5 million bankruptcy and didn't have but $146 assets. No, I wasn't held up by no robbers, and I wasn't in any swindling gambling games. It was all "honest" business people I trusted who took the money, all good, upstanding people. I was too busy makin' it to think about savin' it. I started with nothin' and I got nothin' left, so I've come full circle. But I'm rich. I'm a millionaire. Know the reason why? Because I go to Mass every morning. I have been a daily communicant for the last 50 years. Everything I've accomplished I've accomplished in believin' that seek ye first the kingdom of heaven and all things will be given to thee. Consider the lilies of the field . . .