Chapter Four

"Social Work:"

Visiting and the Creation of Community

Farmer John Plummer Foster made a special trip from North Andover, Massachusetts, on Monday, December 21, 1857: "I went down to Boxford, and called at Edward Foster's, Caroline Batchelder's, Charles Spofford's, and Aaron Spofford's." After his morning sewing in April, 1845, Brigham Nims made a round of visits: "started for the P.O. about 9 o'clock. Called at Mr. Adams', Asa & Joshua, Lawrence's, Dr. Buckministr's, then to Win. Nims'. Visited Laura . . . then I called at Uncle Rosewell's & Wright's, then home." The sheer volume of visitors filtering in and out of everyday routines astounds the twentieth-century reader. Looking at a diary can feel like reading a telephone book, calling roll for the community. For example, on that bustling Saturday in January, 1853, quoted at length in Chapter 1, Martha Barrett chronicled the visitors to her household: Pease Page, Cousin Hannah Grant, Sophia Roberts and little Mary, Parker Pillsbury, Lucy A. C., Uncle Thomas and Aunt Hetty Haskell, and James Wilkins. Nine people "dropped by" over the course of the day, and Martha went to visit three others. Occasionally, even diarists themselves perceived the volume as excessive. Such was the case for Sarah Root, a woman married to a forkmaker/blacksmith in Belchertown, Massachusetts, who took in boarders to make ends meet. One cold February day in 1862, she recorded in her diary: "Mr. Mrs. [A.] Owen. Suson Owen and company. Mary Smith company. All company, nothing but company. Who ever see so much company?" Visits—purposeful and systematic but informal and unplanned—pro-

vided occasions to exchange comfort, companionship, information, and moral evaluations, in addition to labor.[1]

Visits involved an individual or group going to another household. While there, visitors talked, occasionally worked, and sometimes ate food or drank tea. The many types of visiting ranged from pure socializing to communal labor; visitors took afternoon tea, made informal Sunday visits, attended maple sugar parties and cider tastings, stayed for extended visits, offered assistance in giving birth, paid their respects to the family of the deceased, participated in quilting parties, and raised houses and barns. Visits lasted from a brief stopover, or a "call," to a leisurely afternoon, to a month-long stay. Visitors frequently stayed overnight. The difficulty of travel—particularly in winter, by foot, horse, stage, wagon, or train—created barriers to visiting but did not deter visitors who highly valued their contact with neighbors and kin. It was through visiting, in fact, that they created their communities.[2]

Visiting, as part of an elaborate system of exchange, reaffirmed group membership and incurred an expectation of reciprocity. It expanded the contacts of the private sphere, broadening and deepening the networks of social intercourse. Visiting maintained community life through a system of social and labor exchange. This interactive process—engaged in by both men and women—depended upon a premise of reciprocity which created demands and obligations amongst neighbors and kin. Unlike charitable or "friendly" visits, it assumed that visitor and host generally shared an equality of circumstance. The act of visiting honored the individuals visited as well as confirmed their inclusion in the community.[3]

Like the division of labor and friend relationships, the practice of visiting challenged the idea of separate spheres because both men and women visited, often in gender-integrated settings. Both men and women brought interests and skills to the social sphere, lavishing energy and time in performing its labors and partaking of its rewards.

Late-twentieth-century culture views visiting as a leisure activity. Antebellum New England culture did not separate leisure and work in the same way. As well-expressed in Reminiscences of a New Hampshire Town , neighborhood gatherings "had to be predicated upon a good honest excuse, since just gathering for pleasure would be a waste of time." While subjects visited as a form of entertainment, they also used visiting as an occasion for work. Work often intermeshed with leisure, and vice versa. During visits, subjects exchanged labor, critical services, and entertainment.[4]

The massive shifts in the market economy over the course of the nineteenth century transformed activity in the social realm. Industrial capitalism reorganized social life through the constraints it placed upon opportunities to visit and in the way it fundamentally reordered economic production. The production of textiles in particular was dramatically transformed from 1820 to 1865. In 1820, mothers and daughters still busily spun thread and wove cloth in the household. By 1865, the domestic economy rarely incorporated these activities. Also, as caretaking became professionalized in the expanding service sector over the course of the century, men and women performed fewer tasks such as attending births and caring for sick neighbors and friends. This transfer of activities diminished the place of labor in visiting exchanges, rendering them largely social in nature. In addition, the progressive specialization of production separated it from leisure, rendering the sociability of exchanged labor largely a relic of the nineteenth century.

How do these observations about visiting challenge the public/private framework? The dichotomy implies stark differences between the two realms and exaggerates their distance. The powerful images evoked by the terms public and private overshadow nuances that existed in practice. Visiting took place in the church, at schools, stores, town meetings, virtually everywhere people congregated. At the same time, a majority of visiting, at least that recorded in diaries, letters, and autobiographies, occurred in the home (either that of the diarist or that of the person named), in the "private sphere." But given the interactive dynamism of the visiting enterprise, to describe a visit as "private" simply because it often occurred in a household would distort the activity, its meaning, and its consequences.

Let us take the logic one step further. The use of the public/private dichotomy implies that private also means not public : not outside the household, not beyond the family, not involved in politics, not related to government. It suggests a turning inward, a self-absorption. But visiting, as this chapter will demonstrate, was not limited in any of these ways. Restructuring the dichotomy to include the social does not simply mean relabeling activities—it requires that we reconceptualize them. The boundaries between spheres were not absolute; they overlapped, constantly shifted, and were renegotiated by historical actors. Thus visiting must be understood as integral to alternative economies, as a welfare system executed without the state, as a conduit for exchanging ideas and opinions, and as a network for emotional and psychological support that linked individuals to one another.

Subjects engaged in a community network felt obligated to others and expected that good deeds and favors would be returned. Through the practice of visiting, Martha Barrett became part of the anti-slavery movement and the Reverend Noah Davis built a congregation for his church. Citizens did not act, think, or vote in a vacuum; they did so within the context of a dialogue, gauging reactions of neighbors and kin, rethinking their own activities and positions. Visiting was a composite of these activities. People discussed politics, religion, the weather, their neighbors' crops, and the evils of slavery. In the process, they circulated news, ideas, opinions. To characterize this ferment as "private" obscures the reality it plays in the process of crafting a community.

Visiting as Social Exchange

Diarists in this study rarely recorded the content of their interactions, but they religiously documented their visits and visitors, indicating their importance as events. Leonard Stockwell visited neighboring villages in western Massachusetts, telling stories and jokes. Talk focused on events and people, and as Horatio Chandler recorded, "upon religion." Eliza Adams wrote from Lowell, Massachusetts, of her Christmas celebration: "We are all out at the house in a most noisy mood; some talking, others sewing, all most busy in the enjoyments of the day. We have been very much excited on small pox, mad dogs, & reduction of wages."[5]

While visitors made routine stops, others practiced ritualized visiting for occasions such as greeting a newborn infant or paying respects to the family of a deceased. For example, seamstress Louisa Chapman logged the visitors during the sorrowful days in March, 1849, following her mother's death. Most diarists vigilantly recorded deaths; and some, taking their role as family or community historian quite seriously, also recorded causes of death. But unless the deceased was a close family member (and sometimes even then), diarists were most likely to record the social dimension (versus the personal/emotional one) of the death and its aftermath. For example, in keeping with the social focus, a female domestic servant commented on the size of the funeral she attended but not on her feelings about the deceased:

Today is for the funerall. Arad is burrled at eleven o'clock is to be burried with massonic honors had a retry large funerall. There was a great many of the friends here to supper.

Deaths were routine and frequent; funerals were events.[6]

Larger community gatherings—dances, parties, church services, town meetings, and fairs—stirred conversation and visiting. Communities planned events in advance (in contrast to routine visits) that included a wider range and larger number of people. The events varied seasonally, many scheduled in the evening (singing school, lyceum lectures, parties, and prayer meetings) and on weekends (church meetings, fairs). Although winter brought snow, simultaneously an impediment to travel and the means for sleighing, it also brought relief from long intense hours of farm work, freeing people to socialize. Singing school convened almost exclusively in December, January, and February. Neighborhood gatherings provided common ways of escaping farm chores and learning the latest gossip. The maple run in the spring provided the occasion for sugar parties. If one could find the time, one could go "berrying" with a group of friends in the summer or "chestnutting" in the autumn. And after the harvest, neighbors shucked corn at bees, peeled apples, and tasted cider.[7]

In antebellum New England, although women visited more than men, visiting was not an exclusively female enterprise. Both men and women called upon family members, neighbors and friends, often in genderintegrated environments. One hundred percent of the women and 86 percent of the men in this study recorded visiting activities in their diaries. Both men and women interrupted their day's labors to visit someone or to provide refreshment for an unexpected caller. Both traveled great distances to help raise a barn or quilt a bedcover or provide company for a lonely friend.[8]

However, the qualities of visiting differed for men and women. Female diarists recorded having guests over for tea dramatically more often than male diarists (54 percent as compared to 4 percent). Women mentioned receiving visitors in their own homes only slightly less often than they called on others (93 percent versus 100 percent), while the discrepancy between hosting and visiting was much greater for men (46 percent mentioned hosting, while 86 percent mentioned visiting). As these figures make clear, men acted as hosts significantly less often than women, or at least they reported hosting less frequently than women. It is important not to overstate this case, however, because men played active roles as both guests and hosts. Leonard Stockwell took great pride in hosting visitors: "He was decidedly a home man and liked to have everything comfortable and make those welcome who came to visit him."[9]

Obligation and Reciprocity

Visiting, as part of a system of exchange built on the principle of mutual obligations, bound neighbors and kin. Visiting incurred reciprocal obligations, not simply to individuals but also to the group. The community logged individual visits into a kind of community trust to be used as a resource in times of need. Participation in the system offered group membership and the status and honor it bestowed, aid in times of need, companionship (at least occasionally), and access to the news circuit. People sustained their community life through the practice of visiting. Community studies identify institutions, such as the church, the school, labor unions, and volunteer associations, as pillars of community life. While these are unquestionably structures that connect individuals to a larger society, I examine community practices at a more intimate level. Individual work, active engagement, and reaffirmation of ties with other individuals are required to set these larger institutions in motion. Human action made an organization an entity, a church a congregation, and abstinence from alcohol a movement.[10]

Between neighbors and kin, visiting obligations acted as a powerful motivating force. Mary Adams wrote home to her family from the textile mills in Nashua, New Hampshire, in 1835, reminding her sister of promised visits: "Saw Mrs. Dole last week. She wants you to come over very much to alter that cap & bonnet for a dish of tea, you recollect . Mrs. H. says she is almost out of patience waiting for your company to go over there for the tea." Relatives and friends felt the imperative to visit when they traveled in the vicinity of someone they knew. Not acting on this obligation potentially slighted someone. Textile worker Sarah Metcalf expressed this fear to her mother in 1844: "Uncle . . . wants James and I to make them a visit before I go home. What would he say if he knew we had been to Middleboro, and not come to see them?"[11]

Parna Gilbert, a seamstress and caretaker of the sick, used the language of obligation in her diary entry for September 19, 1852: "Coming home from meetting we called to Cousin M.'s. Their child is verry sick, but I hope its life may be spared. Cousin is alone now. I suppose I must go there tomorrow and stay a few days." In fact, she stayed a week, leaving the baby and mother "more comfortable." Addie Brown wrote to Rebecca Primus about her brother in New York City, who had requested that she come to visit him during his ill health. She ultimately declined because of her need to work for money. Addie regretfully reported her brother's admonition for not complying: "My

Brother don't write any more to me. I suppose he don't like it I did not come. I wish I had of gone as I was not to work." She gambled insecure paid labor in lieu of observing an obligation within her kin network, and she suffered disappointment in both realms.[12]

Although subjects did not plan most visits, they did arrange some in advance, especially those that involved arduous travel. And then, when a plan fell through, they felt dejected. Domestic worker Lizzie Goodenough's morale relied on sabbath visits in particular, perhaps because it was her only day off. She complained of loneliness when no one showed up to visit. "It is realy a long lonesome forenoon, only four of us here." Sarah Trask felt disappointed when her visiting plans were thwarted: "called at the shop to see M.E.R. She told me that she would come up and pass the evening with, but she did not come. I suppose she could not come. I was very much disapointed." Although Brigham Nims did not label his feelings, his declaration of the absence of visitors documented a melancholy holiday: "Thanksgiving. Staid at home. Had the headache. No one visited."[13]

At an extreme, failed visits brought anger, disappointment, and in the case of school teacher Ann Dixon, a joking threat of retribution:

Friend Ann,

I beg to know why you have not called on me? Didn't you know it was very "imparlite" not to call on your new neighbors? Here I've been prink't up for most tu weeks in my light caliker gown spectin callers every day and not a soul has made their pearance . . . I hope Ann you haint tuk a miff at nothin as some o the foulk I could name hav . . . I donne whut this ere warld is cummin tu or the habitants in it. There's no pendance to be placed on um. Why you jest part with sum on um the best freends in the warld at nite and when you meet um in the mornin they'll be jest your beeterest inemis. Now I've no simputhe with sich freendshups. I go in for the genwine creetur itself give me the freend that'ill stik tu you thru thik an thin and not be oggled about by every mischieffs maker that crosses there path—that's my doctrin.

Why Ann du you spose that I shud bleve one word if forty slandurus, tattlers an mischiffmakers shud cum and tell me that An Dixen was not the freend she peered, that she was wun thing to my face and anuther tu my bak? . . . but I'm ruther gettin off my trak my objec was in writin jist now—tu find out why yu hadn't called on me. I can't think its cuse your mad or any sich thing gess it mus be as how you hav'nt heered that your freend Luna had moved intu your neighburhud.

Presumably, Ann's good friend Erlunia adopted the pen name of "Luna." In her exceedingly illiterate letter, "Luna" conveyed her affront at Ann's

neglect. Under the veneer of humor, she attempted to manipulate Ann's sense of obligation as a neighbor and as a friend. For whatever reasons, Erlunia had not seen Ann for a while and held her responsible. The letter was funny precisely because it exaggerated the ethics of social exchange, although it did not distort them. "Luna" thought herself entitled to a respectful welcome; it was incumbent upon Ann to welcome her properly. Visiting identified those visited as part of a community circle; conversely, those not visited remained outside. For example, in recording the festivities surrounding a surprise party for Abba, a male friend, Mary Mudge revealed the weight of the message conveyed by visiting as opposed to not visiting: "Martha Jane lives in the house with Abba and did not come in because the girls do not visit her ."[14]

Customs dictated not only whether or not to make a visit, but also how one behaved once there. If a host did not observe the local rules regarding hospitality, a visitor might feel insulted. William J. Brown, a freeborn black man who lived his entire life in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote about visiting expectations in a waterfront neighborhood:

If a person went out to make a call or spend the evening and was not treated to something to drink, they would feel insulted. You might as well tell a man in plain words not to come again, for he surely would go off and spread it, how mean they were treated—not even so much as to ask them to have something to drink; and you would not again be troubled with their company.

Subjects also evaluated the duration of a visit in assessing whether the mutual obligations had been sufficiently met. Was the visit long enough? If not, as in the case of Sarah Carter (in the estimation of Sarah Holmes), the host could rebuke the visitor:

You only complain however of being alone. Indeed I will not sympathize with you in word or though[t]. I will rejoice if possible over your feelings of loneliness for you should not have left Foxcroft so soon. So short was your visit here that I was not sure that you had been here at all this spring.

Three years later, Sarah Holmes (who by 1854 had become Sarah Holmes Clark) discussed the impact of obligation on how she spent her day.

I was interupted by company yesterday. I had visitors all day, nearly, & this morning I devoted to visiting. I felt obliged to go as I am much indebted, owing to my long illness, and I fear that people will think me very unsociable if I do not i[m]prove the first opportunity.

Company interrupted her labors, but she owed it to her community to repay the attention she received while ill. Her neighbors successfully communicated a message to her: to be unsociable repudiated community commitments. Such behavior was unacceptable. Sarah observed the culture of Madison, Georgia, with the eye of an untrained but perceptive anthropologist. Teaching at a school where her husband was schoolmaster, she noted that Madison folks visited more than those in Foxcroft, Maine, where she grew up. And the southern, purely "ceremonious" calls, she found taxing:

As I have said before, the ladies here visit as much as in a city & dress the same. When I am in school, my friends, particular friends, those with whom I visit sociably, come to see me at night & consequently we are seldom alone at night. & other call at 12 & 1 o'clock. You may be assured that I do not care to see or receive fashionable & ceremonious people at noon when I have been in school all the morning.

Clearly, Sarah Holmes Clark thought the women of Madison, Georgia, extreme. The cultural differences between North and South irritated her, although she did her best to accommodate the new visiting expectations.[15]

In spite of Sarah Holmes Clark's observation of regional differences, white working women in New England described their routines as bustling with social activity. Susan Brown Forbes acknowledged an unusual day in her schedule, "I staid at home for a wonder." A few subjects indicated it was possible to visit too much. Mary Mudge, a very active visitor, wrote, "Have been a good girl this week and not been away evenings." She also wrote that her boyfriend, Phillip, "don't approve of making calls 'till the work is done." Sarah Trask acknowledged that her mother similarly prioritized work over visiting: "My shoes are not done yet, I begin to think that I am lazy, and yet I try to do all I can. . . . Mother tells me that I run about too much to do anny work. I can't think so, but suppose I shall have to." These slight admonitions suggest that beyond an undefined but mutually agreed upon limit, women (men did not appear to share the same constraint) became gadabouts. Margaret, Mary, and Hannah Adams wrote to their parents in 1841 about their cousin: "We like our Cousin Eliza very much. She has a good deal of Adams' blood in her, very industrious, prudent & steady, not given to gad." However, while female diarists kept an ear to the message, the threat of sanctions did little to keep them at home.[16]

Emotional Sustenance

Visits could provide essential emotional support to those who needed it. Sarah Trask described her mood change when visitors arrived:

This day, t am not so cross. I have been at home today. Ironing and shoes have been my work, Lizzy came over and pass the afternoon. William came to tea. S. Trask came over from Danvers, came to go down to the Sons meeting with Joshua, so came up to tea. I was glad that he did, for I am always glad to see my friends. M.E.R. and L.A.B. called in the evening.

The companionship of her friends helped lift her out of the dark gloom in which she stewed while brooding about Luther, her boyfriend at sea. A visitor could help combat the occasionally oppressive loneliness of rural life. Soon after she married Stephen Parker and moved to North Andover, Massachusetts, from New Hampshire, Anne Parker wrote to her sister-in-law about being lonely. She had few friends and no nearby kin, except in-laws. Her husband, a farmer and shopkeeper, worked long hours at the store.

One in a store has not much spare time for sisters, or wives either. At least I find it so. I cannot even get an half hour, these long lonesome evenings. You may be sure I do not fail to beg for it, and receive the encourageing reply, "l'll come up if I can," which always means "I can't come." I have a little kitten for company, but then she does not talk even as much as you do. And as to the matter of reading, I verily believe she is as ignorant of it, as the man in the moon.

Elizabeth Metcalf wrote to her mother-in-law about the importance of visiting her aunt, uncle, and cousin Edward after the death of their young daughter/sister:

They are lonely, O, how lonely they must be without her. For in her and Eddard all their plans in life were connected. Aunt says that Edward appears like a man that has lost his wife. His health is quite poor, his limbs trouble him much. Aunt said she wished that I would spend the winter with her for she did not feel as if she could be alone so much as uncle and E. are at home but little except nights. I told her that I would spend some weeks with [them] this winter.[17]

Individuals recognized social contact as restorative and acted when possible to dispel isolation and loneliness. Pregnancy in the context of frequent moves kept Paulina Bascorn Williams out of the social loop. Paulina, who described herself as "Evangela," was a missionary married

to a poor itinerant minister. Between 1830 and 1833, her husband's ill health and search for a good job repeatedly disrupted her social world, as they moved from Parma, New York, to Orwell, West Haven, and then Tinmouth, Vermont. Compounding the situation, her status as mother-to-be in 1831 confined her to the household, kept her out of church, and provided little opportunity for her to meet people in each locale. Paulina found the West Haven community particularly reserved and unwelcoming and looked forward to the next move as something of a relief: "I have been confined at home & by that means am immeasurably unacquainted so that I have no favourite friends to leave & the loneliness of the place forbids local attachment."[18]

For some, a visit for its own sake was not satisfactory. Martha Barrett revealed that in order to combat her deep loneliness, she needed companionship based on mutual interests:

Read awhile. Then closed my book and sat by the window. I was lonely, felt a strong yearning for society. How very few associates I have. Suppose it is my own fault, because I make such a recluse of myself, stay so much at home, but I find few girls who have the same thoughts as I have, or feel interested in the same subjects.

This example serves as a reminder that loneliness and isolation penetrated people's lives on many levels. At other times, Martha Barrett's life bustled with activity and swarms of people. Neighbors and casual acquaintances did not quell her desire for deeper, more intimate friendships.[19]

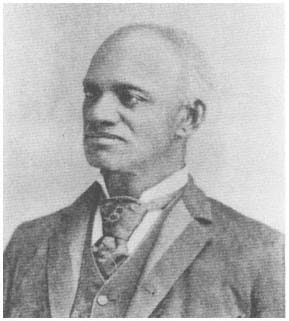

The Work of Visiting

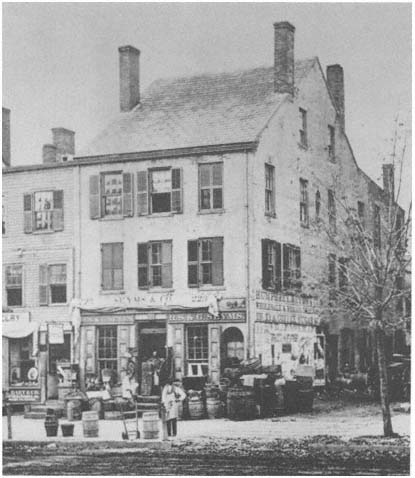

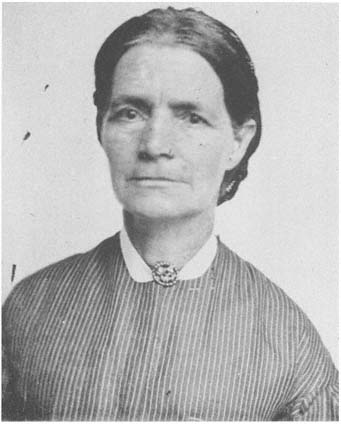

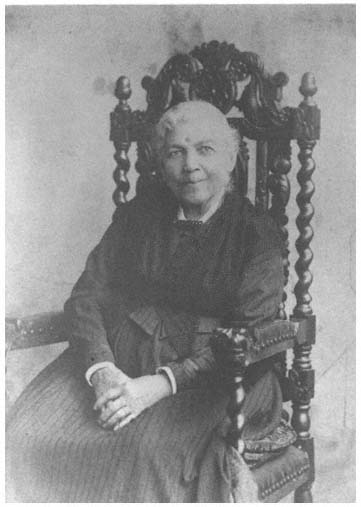

Despite their rewards and satisfactions, New England working people sometimes perceived visiting obligations as demanding labor. After leaving her New Hampshire schoolteaching job to become a farm wife in Connecticut, Mary Coult Jones (see Figure 15) recorded her struggle to make a place for herself in the new community: "Saturday have called on the neighbouring populace. Had a fine time and feel as if it was hard work." In his autobiography, the Reverend Noah Davis, a former slave who purchased his own freedom, wrote about a similar phenomenon in the South. He visited as part of his strategy to build the Saratoga Street African Baptist Church he founded in Baltimore, Maryland. "During this time we succeeded in getting a better place for the Sabbath school, and there was a larger attendance upon my preaching, which demanded

reading and study, and also visiting , and increased my daily labors." Sarah Holmes Clark observed that "The ladies of Madison visit a 'great deal.' I sometimes wish that they would not come to see me quite as often as they do for if I pretend to pay all my visits in 'due season ,' I can find time to do nothing else. Besides I consider it a task to make ceremoneous calls." Parna Gilbert, a seamstress, caregiver to the sick, and no stranger to work, recorded her exhausting week in September, 1851:

Mother was absent until Wednesday. I washed Monday and had 8 men to dinner & three folks to supper and the same the next day. & Wednesday Mr. B. brought M. home & was here to dinner. & Thursday Phebe visitted here & yesterday we had eight to dinner and supper. & today Mr. Tower & wife have visitted here & thus the week has finily ended. My health has become much impaired by this week's labour.

With her mother/coworker away, Parna managed the responsibility of preparing meals for boarders in addition to visitors. Cooking required enormous amounts of time and energy, physically exhausting Parna by the week's end.[20]

In analyzing twentieth-century Italian American communities, anthropologist Micaela di Leonardo has introduced the concept of kin work to refer to "the conception, maintenance, and ritual celebration of cross-household kin ties, including visits, letters, telephone calls, presents, and cards to kin; the organization of holiday gatherings; the creation and maintenance of quasi-kin relations;" and many other activities. This concept of social activities as "work" can be usefully expanded to include visiting activities within a community, not solely those within a family. Community-building activities also required time, intention, and skill; they were a kind of "social work," or work in the social sphere. Social work included planning, visiting, maintaining connections and ties, caring for sick neighbors and extended family members, sponsoring functions in the church, monitoring the behavior of wayward individuals, and for the recently converted, bringing others to Christianity.[21]

Di Leonardo found kin work to be largely women's work. In her study, Italian American women exclusively constructed ethnicity (through food preparation and holiday celebrations) and maintained extended family connections. Their centrality to these endeavors brought them greater power and familial authority. The evidence in this chapter suggests that as in di Leonardo's ethnic communities in the twentieth

century, New England women in the antebellum period were at the nucleus of a system of exchange. But men were not excluded from this world; they too engaged in the intricate construction of community life by participating in the social sphere.

Family ties had to be sustained by kin work, as did community ties. Biological relationships became kin networks only through dynamic deeds. In a letter to his younger sister Rhoda in 1841, Stephen Parker lamented his lack of contact with her during the years of their separation. While it is not clear what prompted his remorse, Stephen attempted to renew ties and regular visits that to him symbolized being a family:

I have been expecting for a long-time to find time to give you a call, for I want to see you very much . It does seem a great while since I have seen you. And in fact it is a great while . And I hope, and intend it shall never be so long again. While we live so near each other—I have been thinking of it lately and really it is too bad we live in about one hours ride each other and yet do not see, or meet together oftener than once or twice in a year . This is certainly not right—and what is almost as bad we do not write each other once , every year hardly—in fact we hardly seem to be "brothers & sisters." Let us my dear sister be more like "children of one family," let us see each other as often as is posible.

To him, brothers and sisters became a family through visiting. While Stephen's subsequent visiting may not have been as constant as he planned, thereafter he sustained a regular correspondence with Rhoda.[22]

Parallel Projects and Shared Work

Work entered into the visiting scene in another way, through parallel projects. Many female diarists tried to arrange to do their work in a social context. In the example earlier in the chapter, Sarah Holmes Clark experienced visits that affirmed friendship or that incorporated work differently from those which she characterized as "ceremoneous." When visitors brought their work, she could work too. "There are many ladies who take their work, for southern ladies are very industirous, and spend a whole morning or evening with me. These are the visits that I prize." Visiting did not interrupt the work in her life, and work did not distract from visiting. She happily combined the activities. For some occupations, such as shoebinding or sewing, arranging to work with someone else alleviated the isolation endemic to domestic piecework. Sarah Trask customarily worked on shoes in a group of sister shoebinders: "At home today. Mrs. Claxton came in this afternoon with her work. Lizzy and

L.A.B. pass the afternoon with us." And on another day, "A.A.B. came in with her work and we had a grand time." Again, the social dimension transformed the work into an enjoyable activity. Seamstresses and shoebinders shared her practice. Mary Holbrook took shoes and sewing to other households on a regular basis. For example, "I went up to Mrs. Hines & bound shoes." "I went up to Uncte's & sewed." Marion Hopkins, a leather pieceworker, stitched wallets with her mother, her sister-in-law Phoebe, and her friend Sarah: "Mother & P. stitched wallets, p.m. Sarah came down to stitch & staid all night."[23]

Subjects relieved the isolation of their work through parallel projects. Domestic worker Lizzie Goodenough of Vermont recorded her shared project with fellow worker Mary Lynch: "we had two hundred & seventeen pieces in all to iron." While nothing could transform the task of ironing 217 items into joyful leisure, working with at least one other person lightened the psychological as well as the physical burden. The work became social rather than solitary. Given women's objections to the oppressive isolation of domestic labor, paid and unpaid, over the last two centuries, this transformation should not be underestimated. Subjects also shared other domestic chores, particularly the weekly laundry. A division of labor was facilitated in households with large staffs of domestic servants, such as in the household of Francis Cabot Lowell II where Lorenza Berbineau worked (see Figure 16).[24]

It was not uncommon on a farm for an employer to work alongside the hired help. Lizzie Goodenough wrote about knitting, washing, and baking with her employer, Mrs. Howe:

This is another dull morning as we have not got much to do this forenoon except get boiled dinner. Have been knitting nearly all the time since I got the work done. We have had quite a knitting scircle this afternoon. Mrs. Howe. Celia. Sarah. Mellissa & myself have all been knitting.

The morning work passed dully, but the afternoon work in a "knitting scircle" of five became a pleasurable occasion.[25]

For male diarists, whose work was different, the sociability dimension is more difficult to analyze. Farm work often necessitated the participation of more than one person. This resulted in farmers having large families, neighbors helping each other, and/or farmers hiring extra hands. Farmers' daily diary entries enumerate endless lists of people. For example, John Plummer Foster wrote about a typical workday in 1852 that involved many people:

We were weighing out hay for Dane Foster, diging up trees for Isaac Stevens, and Wm Wood, picking over apples for Mr. Balch, grafting trees for Joseph Carleton and myself, trading cows with Daniel Abbot, and hay with Mr. Howard &c, &c, &c.

How much of this resulted from a conscious attempt to make the labor social as opposed to efforts to lighten the physical burden is often impossible to tell. But either way, the diaries reveal that farmers consistently performed work in a social context.[26]

Visiting and the Exchange of Labor

The emerging market economy and industrial organization of work transformed visiting as an exchange of labor as well as visiting as social exchange. Throughout the late nineteenth century, social activities became increasingly differentiated from economic ones. In the antebellum period, as in colonial New England, leisure and work were often intertwined. Today, we often think of them as mutually exclusive. This separation has been shaped by the evolution of a capitalist economy and an industrial organization of work. Urbanization also increased the need for interacting with strangers as opposed to acquaintances, friends, or relatives. In the early nineteenth century, many activities still combined economic and social dimensions. Examples below illustrate the exchange of labor through the diarists' accounts of caring for the sick, attending births, and participating in communal labor.[27]

Caring for the Sick

Friends, relatives, and neighbors exchanged at least one essential service in the social realm: caring for the sick. Illnesses routinely shortened longevity and heightened infant mortality in the nineteenth century. Medicine remained more an experimental rather than a scientific practice. Illnesses such as cholera and scarlet fever periodically infested communities, took many lives, and spread rapidly, their causes unknown and their contagion misunderstood. Medicine often ineffectually treated patients, and disease frequently brought death. Becoming ill always foretold economic hardship in the form of lost wages or unattended farm chores.[28]

Regardless of the conditions, the sick needed to be tended and

"watched." Subjects used the means available—home remedies, herbs, bleeding, water treatments, prayers, doctor visits if the illness was severe—to try to cure their patients. Sometimes nothing could be done, leaving bedside company and hot tea the only comforts. In this context, visiting became central to the treatment of the sick person.

Propriety dictated that at a minimum, neighbors and family must visit the sick to cheer them up. Addie Brown recorded: "Miss H. Freeman fell. Very bad. I must go and see her." In this instance, the obligation to visit resembled visiting in general, but the need intensified because of the immediacy of the injury. Few diarists recount their conversations with the ill; exactly what transpired during these visits we can only speculate. In one rare exception, Parna Gilbert offered a glimpse of a conversation, revealing her forthright but tactless bedside manner. She went to call on the neighboring Brown family (not that of Addie Brown) and found Mrs. Brown in bed with typhus:

She said, "I am very sick." I told her I was sorry she was so sick. She replyed, "It is distressing." I asked how long she had been so. She said she was taken down very suddenly about a fortnight ago with Typhus fever. I said, "I am afraid you will never get up again." She said she thought it dreadful. I said, "I suppose you can look forward to a more blissful abode." She replied, "I wish I might."

Mrs. Brown asked Parna to pray for her and Parna found herself feeling "a peculiar sympathy" for the Brown children.[29]

Diarists did not consistently distinguish watchers from visitors in their diaries, although in practice, watchers, in contrast to the more limited role of visitors, performed any task that provided comfort for the patient. Watchers waited on the person, administered medicine, tried to make him or her comfortable, and as their job title implied, watched him or her. They watched to monitor the patient's breathing. They watched for a change in the patient's condition. Zeloda Barrett reported such an alert the night before her sister Samantha died: "The watcher awakened me & told me there was some alteration."[30]

Some women made caring for sick people, or nursing, their occupation. For example, Pollie Cathcart, who remained unmarried at fiftyone, cared for her mother as she grew old and approached death. After her mother died, Pollie became a community nurse rather than a family one. She cared for ill people and assisted in households with new babies, staying anywhere from one night to four months. In addition to the few female diarists who made nursing and watching their primary trade,

numerous others were called upon to watch with the sick when circumstances necessitated it.[31]

The need to care for seriously ill patients demonstrated the particular importance of community responsibility for the sick. When patients had to be watched around the clock, community members rotated responsibility for watching them. In one extreme example, Samantha Barrett, a farmer, recorded the visitors and watchers at her side for the last twenty-one days of her life. Seventeen neighbors, friends, and kin watched her (in addition to a doctor) during that final three-week period.[32]

Clearly, caring for the sick was essential to individual households as well as the community. However, the degree to which that service was honored and valued by community and family members is a matter of debate. Susan Reverby finds this contradiction a central dilemma in American nursing. She claims that women have been ordered to care "in a society that refuses to value caring." As Reverby found in her research, extended families in this study routinely called single women away from their paid employment to care for the sick. Mary Parker wrote to her sister-in-law Rhoda:

Beloved Sister . . . if your health will permit and Mrs. Lovjoy can spare you, we should like to have you come and see Lydia and stay a week or fortnight to set in the rooms to wate on her. You could bring sewing or any other work that would be conveniant to cary abroad. If you can come Stephen will go after you.

Pulling women from paid employment evidenced the importance of their skills to the family. Mary Giddings Coult said, "dismissed my school to go & take care of Cousin Lydia C." Similarly, schoolteacher Louisa Chapman wrote in 1849 that "owing to the sickness of my mother my school closes to-day." Another schoolteacher, Pamela Brown, wrote, "About eight o'clock this morning Cephus Wheeler called at Mr. Hall's and let us know that Mrs. Taylor's babe was dead. He wanted to go to help them today. As Mrs. Hall was gone I told him I would go and did not keep school today." Such a practice was common among millgirls as well as teachers; Mary Hall left her job as a weaver and returned to New Hampshire in response to one of her many calls to familial duty: "Heard from home to-day. Brother I. and sister J. sick and grandfather not able to walk or step. And father and mother wish me to come home." Harriet Severance refused to return to her domestic work for her Uncle Calvin because "I could not leave home till Meroa is better."[33]

Reverby declares that nursing was "a woman's duty, not her job,"

and that "no form of women's labor, paid or unpaid, protected her from [the] demand" of caring for sick relatives. However, evidence from diaries and letters of working women contradict that assertion. As alluded to above in Mary Parker's letter to Rhoda, when one occupational calling conflicted with another, paid work could supersede nursing obligations. Rhoda made a living as a combmaker's apprentice, and leaving her job could jeopardize it, if Mrs. Lovejoy, her employer, did not consent to a temporary absence. A similar conflict existed for Addie Brown, who decided, as did Rhoda, not to go take care of her sick brother. She needed her job, and she needed the money it would bring. Parna Gilbert placed the ultimate decision in the hands of the Almighty. "l went to assist Mr. Reed's people. Mr. R. being sick expected to stay until tomorrow, but a tailor came last night wishing me to go & work for him to day. I am expecting to go if it is the will of my heavenly father." In Parna's case, both occupations paid her. Yet in this instance, under the sanction of her "heavenly father," she went with the tailor. An important difference existed between those women who left their jobs to care for the sick and those who did not. Those who stayed with their paying jobs supported themselves; they could not rely on their families, even when they were embedded in an active kin network. They had deep attachments to their families and vice versa, but they had to earn their way in the world. Whatever altruism or obligation they may have felt was counterbalanced by the need to make a living.[34]

The need to work for pay was not the only way to excuse oneself from the duty to nurse. A farm woman, for example, had a job besides caretaking, even though it did not pay a salary, with responsibilities at home that could conflict with traveling elsewhere to care for someone else. Martha Ballard's turn-of-the-nineteenth-century midwifery business could flourish only when she had adult daughters to tend to household chores such as weaving, baking, and cleaning. In antebellum New England, obligations to the nuclear family could also override obligations to others. Mary Parker Hall wrote to her sister Rhoda Parker, who had taken ill, "I thought after I came home if I could only washbake-and-brew, and then fly back to you, I should have been glad. But am pleased to know that you have been well provided with help." Her commitment to "wash-bake-and-brew" for her nuclear family necessitated that she stay at home. Similarly, Abigail Baldwin steadily traipsed back and forth to the household of her sick mother; she returned home frequently to bake and tend to chores.[35]

Despite having limited resources, the married women in this study

found themselves more financially secure than the single women, and their nuclear family obligations bound them more tightly. Even with these demands, women could and did negotiate their visiting and caretaking responsibilities. The Parker family demonstrated the premium placed on the caretaking enterprise; when Winthrop Parker requested that his sister Rhoda come to New York to take care of him and his wife and son, he offered her a salary commensurate with her current one as a domestic/combmaker's apprentice. Stephen Parker wrote to Rhoda about his conversation with Winthrop:

Lucy to had nearly made herself sick in attending him & baby but was better. Baby quite well. They think of going to keeping house. & W. says, (to me), "cannot I presuade Rhoda to come & live with me?" "I will give her as much as she can make at West Newbury" &c. Wanted me to mention it to you & tell him what you thought of it. When you come up at Thanksgiving we will talk it all over.

Winthrop did not simply appeal to Rhoda's obligations as a family member. He respected her right to make her own decision about where to go. In this instance, Rhoda did not accept his offer. He also recognized her role as a wage earner and the monetary value of her caretaking services, and he offered to pay her accordingly. In another example, Harriet Severance's Uncle Calvin paid her $42 for her six-and-one-halfmonth care of his terminally ill wife and household. Harriet kept a careful account of Uncle Calvin's installment payments.[36]

The evidence suggests that families weighed the value of a woman's paycheck against the services she could provide as a family nurse. Women's wages, consistently less than half that of men, could not always match the value of the services. In the case of Rhoda, the Winthrop Parkers recognized that she depended on the wage for her well-being, and they offered to replace it. If a family or a single woman struggled to eke out an existence, giving up the wage was not an option. If the woman maintained her own livelihood, even though part of an active kin network, she could and often did opt to stay with her paid employment. However, in situations where kin networks shared economic resources, the women often left their paid employment to care for family members.

In light of her parents' recent death, Mary Giddings Coult exercised supreme sensitivity to the issues of family obligation as well as her need to support herself. Her Uncle L. Colby came to get her to stay with her aunt and Hatty. "I must try to do all I can for them. If I do perhaps

when I am sick, some one will take pitty on a poor lone orphan and be as a Mother to me." Her fear of potential ill health and eventual death (whenever it might come—she contemplated it at least monthly) overrode her concerns about supporting herself. She determined that service to family members, a form of social insurance, better suited her needs in the long run. This decision did not trade autonomy for simple dependence; it enabled Mary to navigate the unpredictable seas faced by a young single woman with no parents to help her.[37]

It was not unusual to bring a sick individual to live with a family, although it was less common than sending a nurse elsewhere. Millworker Mary Metcalf discussed caring for her married sister: "I went out to Sarah's during my v[a]cation. Took care of her a while and brought her home with me. She has been sick but is gaining rapidly now. We shall try to keep her till after Chirstmas but William is lonesome now and wants his wife at home as soon as she is able to come." Schoolteacher Louisa Chapman recounted the deliberations that brought her grandmother to live with her and her brother in 1849, a few months after her widowed mother died:

9 May—At home. Mr. Merriam from Middleton called to see if we will take Grandmother. Her children will not have her. And we think we will not.

May 10—At home. Concluded to take Grandmother.

May 14—At home. Grandmother came to our house. She is feeble and partly helpless and will need a great deal of care and attention.

As Louisa's equivocation indicates, not everyone eagerly took on such a responsibility because the work demanded time, patience, and adequate resources. Like Louisa Chapman, Adelaide Crossman, a farm woman and seamstress, took in her ill grandmother for whom everyone else in the family refused responsibility. She found dealing with the elderly woman frustrating: "Got home. Found Uncle Milton's folks here. Grandmother mad. I am out of patience." Parna Gilbert and her parents used their home as a sick house, a hospice of sorts. They faithfully took in the infirm and cared for them. Parna recorded the ordeal of Mrs. Packard's arrival: "Oh what a change hath been wrought in one short week. Little did I think last Sabath that she who is now here was to be brought here, in all probibility no more to go away until carried to her grave. But God only knows what trials we have yet to endure." Obviously not an easy patient, Mrs. Packard led to caretaking responsibilities that physically taxed Parna and her mother: "Mother is already nearly worn

out from the fatigue of the past week having had the whole care of Mrs. P. which has been a dreadful task."[38]

More obviously than with pure socializing, caring for the sick could be physically difficult and emotionally trying. Every nurse and watcher risked catching contagious diseases. And one's social sphere typically contracted to a minute circle when an individual had primary caretaking responsibilities. Sarah Trask managed the loneliness of caring for the sick by bringing a companion with her to visit a friend who "had the cramp": "L.A.B. and I took our work and went down to set with her a little while, for I think it is rather lonley to set alone when anny one is sick." In addition to the isolation, women consistently complained about the difficulty of the work and its fatiguing qualities.[39]

The advice literature of the antebellum period described nursing as a consummate female task, helping women to fulfill their destiny. Motz finds it a female responsibility in middle-class families. While the historical literature identifies nursing as a woman's duty, evidence from my research shows that men cared for the sick as well. With their higher wages and greater political power, men who were teachers or factory workers were not called away to care for the sick. However, male farmers and artisans who had greater flexibility in work routines took time from work and cared for sick relatives and friends.[40]

The gender differences in caretaking activities began with the patient. Men's nursing focused almost exclusively on other men and boys—their fathers, male friends, and sons. J. Foster Beal, a box factory worker, chided Brigham Nims for not writing: "I guess you have forgot all about you being at Boston last Sept. when you was so sick, and I took care of you, doctored you up, even tooke you in the bed with myself." Farmer John Plummet Foster nursed his father, who lived and worked with him:

Friday. Fair and cold. I was half sick with a cold, did nothing but the chores, Father was taken in the evening with a slight shock of the palsy.

Saturday. Fair and cold. I helped take care of Father.

Each day thereafter John gave an account of the weather and the condition of his father's health. The prominence of his father's health in the diary provides a clear sense of its centrality to John's life. Occasionally his distress baldly erupted through his rote entries. "It is enough to make one's heart ache to be with him, and see him, when he has his spasms." Gradually, John began working again, but he remained deeply concerned about his father's care. His father died five months later.

Despite John's immeasurable emotional involvement, he characterized his attendance to his father's needs as "helping." He saw himself as an assistant rather than a primary care provider. John also mentioned staying home to care for his sick son.' "Friday. Cloudy. I staid in the house most of the day, and took care of Horace, he was sick." Horatio Chandler, another farmer and a store clerk in New Hampshire also took care of his son: "Wednesday . . . stayd at home a.m. to take care sick little Geo—that my wife might finish working. Geo [no better.]" Ivory Hill, shoemaker, took care of his sick friend, Moses, and had responsibility as a liaison with Moses' family:

Moses [T] sick taken last night. Threatned with fever.

. . . Set up with Moses [T] last night

. . . Moses very sick don't have much hopes of him. Been over to Deerfield twice to his father's.

It is not clear why his family did not send someone to help care for him or even to visit. The next day Moses died. The number of men caring for other men makes clear that nursing was not exclusively a female vocation.[41]

The widespread conformity to same-sex caregiving for men reflects a deep-rooted taboo about gender-appropriate touching and bodily modesty. The healing arts had long been a primarily female enterprise, and renewed nineteenth-century concerns about female chastity placed malefemale physical intimacy in a particularly delicate situation. Conversely, women did care for non-kin men, but much less frequently than women cared for women.[42]

Married men cared for their ill wives, exercising their responsibility as married persons, the primary exception to same-sex nursing. Sarah Holmes Clark wrote to her friend about the fine nursing skills of her husband. Given her current state of health, she insisted she could not possibly venture to New England and leave his healing hands:

Gilman has spoiled me since I have been sick so much. And I can not do without him for a nurse when my health is so poor. I depend on his as a child relies on its mother. I believe that no one could nurse me so well as he does, because no one loves me as well as he does. Gilman is the best husband in the world; if you do not believe it come & live with us & judge for yourself.

Sarah, in this instance, equated nursing skill with love, an equation that others did not make. However, in using the mother/child metaphor to

describe her reliance on Gilman's care, she evokes the centrality of kin in caretaking obligations.[43]

In a second notable exception to the above gender rule of nursing, two former slaves, James Mars and William Grimes, wrote in their respective autobiographies of their employment and skill in taking care of the sick. James Mars wrote about the adult daughter of his former owner, Miss Munger, calling him to her bedside:

As I had been accustomed to take care of the sick, she asked me to stop with her that night. I did so, and went to my work in the morning . . . She asked what I thought of her; l told her I feared she would never be any better. She then asked me to stay with her if she did not get any better, while she lived. I told her I would. A cousin of hers, a young lady, was there, and we took the care of her for four weeks.

James had a long-term acquaintance with this young woman, and she valued the skills and comfort he brought to her bedside. His skin color combined with his familiarity mitigated the taboo of male nurse to a female patient. In essence, race overrode gender concerns. Had James not been black, it is highly unlikely that he would have been asked or allowed to care for this sick woman. However, because of his status as a black man—once slave, now free but still not a full citizen—James did not pose a sexual threat. A job as a subordinate male did not challenge the status quo of gender relations and actually reinforced existing racial stratification.[44]

The gender of patients was not the only consideration that figured into the caretaking division of labor. As a rule, men stayed in their own households (most of the time), and women acted as a mobile caretaking force, sometimes traveling long distances to care for sick relatives and friends, often staying with them. That said, men had the onus of going to get the doctor, nurse, neighbor woman, or midwife. In the diaries, men frequently gave accounts of their role as messengers or procurers of a nurse. A cabinetmaker's apprentice, Edward Carpenter, recorded his search for a care provider in 1844 in central Massachusetts:

When I went home to supper tonight Mrs. Wells, Mrs. Miles' mother, who has been staying there a few days, was in what they called a cramp fit. I went as quick as I could for Dr. Stone & found that he was not at home. I then came back & went up after Dr. Deane, he came down & gave her some laudnum which quited her. The fit was caused by a Cancer on her breast, which will probably break out in a few days & kill her.[45]

Birthing

The birth of a newborn infant launched a round of ritual visiting as well as a renewed exchange of essential services. Birthing practices transformed over the nineteenth century. In the sweep from the colonial period to the end of the nineteenth century two major changes transpired: (1) medicine professionalized, prompting, in particular, the replacement of female midwives by male doctors; and (2) birth transformed from an open affair that included many female friends and kin, a "social childbirth," to a restricted, private event, monitored by a male doctor, that included few if any women. In colonial America, birth was a woman-centered event, a ritual central to female culture. It was not unusual for women to have as many as ten friends attending the birth, assisting the midwife or simply cheering on the laboring woman. At eighty percent of the births recorded by Martha Ballard, between two and four women were listed as attending the birth. Nearby neighbors acted as birth attendants more often than kin. After the birth, the household sponsored a celebratory supper, with all the attendants participating. Relatively soon after the baby was born, the midwife left, and a nurse (sometimes called a "monthly" nurse) took over to help the mother, child, and household for approximately one week to one month while the mother recuperated. The new mother would gradually resume her regular responsibilities.[46]

By the late nineteenth century, a doctor typically presided over the lying-in of urban middle-class women, secluding the occasion and incorporating few, if any, female attendants. For working-class and rural women, birth practices continued to rely on women's networks. Male doctors did not dominate until hospitals became the site of birthings in the 1920s. According to Judith Walzer Leavitt, in her history of childbearing in America, women in the nineteenth century "went to considerable sacrifice to help their birthing relatives and friends; they interrupted their lives to travel long distances and frequently stayed months before and after delivery to do the household chores."[47]

Women in this study fall into the category Leavitt labels the "traditionalists"—those who had limited access to modern, urban medical "advances" and continued to rely on female-centered home birth, as in the colonial period. None of the subjects gave birth in a hospital. Leavitt maintains that traditionalists relied primarily on midwives. While this is plausible, no diarist or correspondent labeled her birth attendant a "midwife." Nonetheless, subjects assumed certain women had a birth

ing-related competency and skill, making their services actively sought. While virtually all the women who gave birth called on neighboring women, several called for a doctor and in one instance a nurse. When diarists recorded details of a birth they invariably mentioned other women. Some of the women could have been midwives, but the diaries did not designate them as such.[48]

Diarists, correspondents, and autobiographers rarely recorded information about birth practices. They did not reveal what women did, how they felt, the pain they endured, the joy they felt, the despair that must have overwhelmed them at times. Mary Coult Jones detailed the only elaborate account of the birth room. In 1856 she gave birth to an eight-and-one-half pound boy, named Edwin after her husband. "I am in my room. Friends are around me while from the adjoining room I hear a low & mournfull wail." Her mother-in-law came the day after the birth and stayed for eleven days. Her brother came for one month, beginning when the baby was two weeks old. (She had no sisters, and her parents were dead.) In addition, when the baby was five days old, Lydia Cowdery came to stay with the family, presumably to care for them and the baby. Numerous visitors filed in and out of the house.[49]

Women helped each other with postpartum care, and friends, neighbors, and relations came and welcomed the newborn. As with death, those who mentioned births discussed the social dimension—visiting—rather than personal emotions or physical details. Farmer and seasonal store clerk Horatio Chandler recorded the bustle that surrounded his household the day after his wife gave birth:

Saturday. Fine day. Mrs. Partridge staid with my wife to day. I drove my cow to Farwell's . . . went after Lydia Cheney—got her to take care my wife. She is a good hand. Mrs. Hopkins, Scott and Mrs. Leonard been here this P.M.

One woman in Minnesota wrote to her sister in 1856, "Every day there were different helpers about. The ladies in the neighborhood took turns caring for me."[50]

Visiting that welcomed the child's arrival began almost as soon as the birth took place. For example, textile worker Mary Hall wrote on 14 May 1829: "Home. This morning Mrs. Cassen brought a little Son. O that it may be trained up in the ways of virtue. Called in to see her." She visited Mrs. Cassen on the very day she gave birth. She wanted to welcome the new child into the world and probably congratulate Mrs. Cassen for her hard work.

The gendered division of labor in the birth event was clear. As in the

colonial period, women were the sole birth attendants unless they called a doctor. Visitors and nurses, virtually indistinguishable from each other in the diaries, included a mix of married and unmarried women. Women managed all activities inside the birthing room, and men executed those outside. The male doctor proved the exception to this rule. Men recorded births, and men who were closely associated with the mother served as messengers, purveyors of news, and seekers of help. Obtaining assistance for the pregnant woman was often routine, although, like birth itself, tinged with adventure. Store clerk Francis Bennett, Jr., of Gloucester, Massachusetts (see Figure 17), wrote about getting help for his mother when his seaman father was away at sea:

About 2 o'clock this morning Mrs. Hadley waked me up and told me to go over to Uncle John's and tell him to go over after the doctor and up after Mrs. Larvey, as she was not very well. I went over and got Uncle John out and we went together. I got home to Uncle John's again about 3 o'clock and staid there for the rest of the night. About 11 o'clock this forenoon we had an addition to the family of a little girl. It weighed 6 1/2 lbs. This afternoon l hired a horse and buggy and went down after Mrs. Rust, the nurse.

It is interesting that Mrs. Hadley, who was the one giving instructions, called for a doctor and Mrs. Larvey, probably a midwife. John Plummer Foster wrote that he simply "went after the doctor for the baby, and rode round after help." At times, finding someone to help required tenacity, as is evident in Horatio Chandler's account of his wife's labor:

My wife grew worse & by 11 O'clk found it necessary to send for a physician. l sent Marshall for Dunbar. He arrived about 1 O'clk and at 1/4 past 2 my wife was safely delivered of a fine boy, weighed 8 [lb.] At 6 I went to Mr. Fields to get a girl to take care my wife. She could not come. Then went to Mr. Luts for Mrs. [Coble] did not succeed. At 10 O'clk went for Mrs. Albee. She come for the night.

After the baby was born, Horatio Chandler needed the help of a female assistant. When his first effort to hire "a girl" failed, he persisted until he found someone to come and stay with his wife.[51]

Again, we see both men and women involved in what has been perceived to be solely a female activity. Men fetched women to attend the birth and provide postpartum care. Such services, while at the periphery of birthing, were nonetheless crucial to the well-being of the mother and baby. Men in this case became the intermediaries bringing women to assist other women in the most physically dangerous of female rites of passage.

Diarists' accounts of births varied in the amount of detail elaborated. They ranged from a resounding silence (failure even to record the birth of their own child) to an enthusiastic announcement extolling the virtues of the new little family member, particularly for male infants. But most diarists minimally acknowledged births. Samuel Shepard James's accounts of his children's births reflected the typical understated style of recording births: "Cold with snow, squally. Abby A. James born. p.m. Peeling bark," or "Orrin M. James' birth day." Diarists often did not record the weight or health of the baby. In this vein, Joseph Kimball wrote: "Wife put to bed with daughter." Although if something had gone dramatically wrong with the mother, diarists surely would have recorded it, Joseph did not bother noting details when his sister's child was stillborn: "Sophia confined, child dead."[52]

Subjects' celebration of male babies greatly exceeded that of female infants. Stephen Parker, the most ebullient father of a newborn son, wrote a letter conveying his joy: "Now don't you want to hear something about our little red head . Well he is just the prettiest little fellow you ever saw . Grows finely. Is, upon the whole a very good baby ." He then discussed the condition of his wife. Seven years later he expressed his jubilation over the birth of another son in a letter to his sister and her husband:

Dear Brother & Sister, I have the pleasure to inform you that our third Son was born Oct 29th, 1852 at 10 1/2 o'clock in the evening. He is a good looking little Lad, weighs nine pounds , and appears healthy. His mother is, I hope, doing well. He is just beginning to nurse a little. We should be happy to have you make his acquaintance. He has said nothing about his unkles & aunts yet, but will, probably soon be enquiring for them, as near as I could understand him, he wishes to be remembered to his little cousin in W. Newbury. He does not speak our language very fluently. But is quite a linguist. He is an out & out "Free Soiler ," and an "independent Democrat." We think he has all the characterestics of a Great Man .

John Plummer Foster more subtly revealed his gender preferences. Several times he wrote, "Ann presented me a son," as if he had won a prize. When his fifth son (his seventh child) was born, he underlined the passage—highlighting the event in a way he treated no other, as if he could not believe his good fortune. In contrast, the day his daughter Sarah was born, he wrote: "I was choring round, carried mother Peabody home and brought her back again in the afternoon." He failed to mention the birth itself. The baby daughter arrived a nonentity. If behavior reflects values, then diarists expressed preferences for boys. Viviana

Zeliger explains the phenomenon in the nineteenth-century United States: because "the useful child" contributed to the domestic economy (through farm labor, piece work, factory wages, or scavenging and the like), families considered children economic assets. The prized child, the adoptable one in the nineteenth century, was an adolescent boy, who presumably could make the greatest contribution to the household economy. In the context of a sex/gender system that privileged men in countless ways, this preference becomes understandable, even if unacceptable.[53]

Communal Labor

Communities purposely organized work activities, referred to as "bees," in advance and treated them as special events. Quilting parties joined the list of bees to pare apples, haul wood, shuck corn, and perform other chores that required many hands. Osterud finds that in rural upstate New York both men and women attended quilting parties (see Figure 18): "It was the presence of men that made a 'quiltin' into a social event rather than an occasion of shared labor." In character with other types of antebellum visiting, in this study, both women and men attended bees, which were shaped by both work and leisure. Typically around the time of a wedding, subjects organized an explosion of quilting activity as well as other tasks in preparing the household for a new member. Elizabeth Metcalf casually wrote her mother-in-law about the gender-mixed quilting group that busily prepared for an upcoming marriage:

Well I went with Carrie that afternoon to help Lissie quilt , all of the young folks in the neighborhood were present. We had a very social time, Lissie thinks that they shall be married some time this winter.

References to quilting are sprinkled through the diaries.[54]

Women did not guard a quilting as their exclusive province, and therefore it did not function solely as a women's ritual. In 1845, Brigham Nims organized a gathering of quilters:

29—Sharped the stone tools. Then went to the stone lot by Seth Towns. Asked his wife & Mrs. Nye & [Mis.] Daniel Towns to quilt. Come home. Brot [Mis.] Towns home at noon. p.m. asked the young ladies to quilt to morrow. Carried Mrs. Clark home at night, then to [Mr.] Newcombs &c.

30—Work about home. Helped put in a quilt and worked it. P.M.E. & E Buckminister, M. Stebbins, A. & M. Davis, E. & A. & L. Towns quilted. Filled the leach with ashes &c.

In 1829, Vestus Haley Parks, onetime gunpowder-mill worker and later an itinerant peddler of tin and rags, organized entertainment for a quilting:

Sunday. Went to Freman Powerses to get him to come to play on his violin at the widow Phoebe Tuttles on Wednesday evening. Then went to meeting . . . went to Freman Powerses again to have him come Tuesday evening on account of the qwilting being one day sooner than I expected . . . Went to Dan Sperry's and had quite a dance. The girls went there from the widow Tuttle's after quilting.

Mary Holbrook, seamstress and shoebinder, wrote, "Lewis carried Maria & me down to sewing society at Benjamin Nichols. There was several present. The bed quilt was put up in a lottery at 12 1/2 cts a ticket. Harriet Nichols drew it." At a later date she told of thirty people who attended Mr. Bidwell's sewing society. Arthur Bennett, who worked at a Vermont sawmill, went to a quilting and had such a good time that afterward he remorsefully pledged to redeem himself:

Work some till 4 o'clock then went to Mr. [?] King to a quilting party. Quite a large company. Ate sugar, sung, and talked nonsense till 10 o'clock. Came home with a determination not to go into a party of pleasure for three months to come.

Despite the festive details, the specific division of labor at the quilting parties remains obscured. The diaries and letters revealed that both men and women attended, but surviving documents do not say exactly who did what. Men organized quiltings, but how much did they sew? Regardless, the fact that men even attended these events challenges the notion that women's culture grew out of a separate female sphere where women did "women's work" to the exclusion of men. Men involved themselves in domestic activities, in a world that organized a division of labor by gender but did not religiously observe boundaries segregating men and women.[55]

A system of mutual aid and shared work existed for women on a scale more modest than that of the bees. As in the parallel projects described above, small groups of women would gather, teaching each other skills and helping with the demanding work load. One anonymous farm woman in Essex County taught her neighbor to knit. Zeloda Barrett wrote, "My friend Harriet basted me a frock." Mary Mudge and her friends devotedly helped one another with household chores, child care, and sewing. For example, "This eve we were all going up to

Rebecca's to sew for her but when we got there she wanted to go to the concert, so we (Marth & I) went into Sarah's. I should not have cared much about it had I not wanted to go to the concert so much myself. I worked for Sarah on a collar and Marth tended the baby." Betsey Babb helped Susan Brown pare apples. Several women mentioned others assisting them with making carpets and rugs. Adelaide Crossman's friend helped her sew rags. Pamela Brown's friend Marcia drew patterns for her; Mrs. Holcomb made herself the regular partner of her neighbor, Samantha Barrett, for many arduous as well as pleasurable tasks including salting their cows, making carpets, and husking corn. This was true for quilting also. Mary Holbrook recorded two weeks of regular visits by her friends Phebe and Maria, who helped her with her star bed quilt.[56]

Two types of organized work bees tended to be male-centered: raising barns or houses and slaughtering animals. The bees organized the community to share skills and labor power when performing laborintensive jobs. Although it is not clear whether they attended, women recorded the raisings as did men. After a vicious storm demolished the new home of Abigail and Thomas Baldwin, neighbors gathered to raise another. "Ten or a dozen kind neighbors come to assist about the house." As with quilting, the division of labor was not made explicit. It is possible that women prepared food for those doing the carpentry. The fact that women recorded these events in their diaries (as they did other male-only events, such as town meetings—25 percent of the women logged town meetings in their diaries, as opposed to 57 percent of the men), makes it clear that they registered in the minds of both men and women.[57]

Participation in a barn- or house-raising incurred an obligation, as did routine visits. The contributor expected work-in-kind, or at a minimum, acknowledgment or appreciation. Cabinetmaker's apprentice Edward Carpenter expressed resentment for not being thanked after helping build a barn: "I went up to H. W. Clapp's this afternoon to the raising of a barn. & worked considerable hard & didn't get as much as 'thank you sir' for it." Parallel to visiting as social exchange, the exchange of labor built upon the expectation of reciprocity. The moral imperative behind the reciprocity of both kinds of visiting insured that communitybuilding would be complex and multidimensional.[58]

Communal labor served two important purposes during the antebellum period: (1) the need for helping hands in the face of a labor-intensive project; and (2) the need for sociability. Work was intertwined with

leisure. Occasions for work were simultaneously opportunities for visiting, talking, sharing news, catching up on family gossip, and reinforcing ties—in essence, reaffirming the interdependency of the community.

The Changing Structure of Work

The structure of work fundamentally shaped visiting patterns. Cott suggests that the structure of work explains gender differences in social life. She relies on E.P. Thompson's distinction between preindustrial task-orientation and industrial time-discipline. By the mid-nineteenth century, factory schedules ordered men's work, while married women's work in the home remained task-oriented, observing the rhythms of everyday life. Cott claims that the organization of women's lives in the industrializing nineteenth century resembled the "premodern" work of both men and women in the eighteenth century: "unsystematized, inefficient, nonurgent." Separate spheres for men and women emerged, according to Cott, not simply because women did their work at home and men went elsewhere, but because women's work in the household, unlike men's work in the labor market, "seemed to elude rationalization and the cash nexus, and to integrate labor with life."[59]

Because of their work environments, farmers and artisans continued a task-orientation in the mid-nineteenth century more than factory workers did. A substantial percentage of diarists in this study worked in factories (21 percent) at some point during their diary-keeping. Some had to keep strict hours as clerks or apprentices under someone else's direction (12 percent). The other diarists worked in positions that were seasonal (e.g., teaching—29 percent), paid by the piece (e.g., shoebinding, leather pieceworking, itinerant sewing—21 percent), or self-employed (crafts—23 percent—and farming—39 percent). Because farmers, pieceworkers, and artisans worked autonomously, their working lives had a task-orientation, analogous to the work of women who were not employed for wages. Their time was not measured by an hourly wage and could be interrupted; they executed their work in a context where social activities integrated with economic ones. The industrial organization of work largely separated social and economic activities and reduced the amount of time available for visiting.[60]

Although factory schedules interfered with visiting, they did not prevent visiting altogether. Before the speed-up in the textile mills in the 1840s, workers commonly gabbed, read aloud to coworkers, and received calls on the shop floor from out-of-town visitors. Whenever the

mills were shut down due to unstable demand for textiles or weather impediments (e.g., a frozen river meant no source of energy to run the factory), factory workers shifted instantaneously into a visiting mode. In addition, they regularly spent their evening hours fraternizing with coworkers and friends and attending community events.[61]