Ergotism, Illness of the Poor

The interplay of medical motivations and botanical research at the Academy is apparent in Dodart's study, published in 1676, of how ergot injured the health when ingested in bread. His research also clarifies how the Academy served as the focus for a network of physicians interested in the medical problems of the poor.[27]

Ergot grains grow on rye as the result of an infestation of the plant with Claviceps purpurea . The effect of this infection is to replace developing grain with ergot, a fungus that "contains several toxic principles," including the alkaloid lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD.[28] When eaten after being ground with rye into flour, the fungus causes the deadly illness then known as Saint Anthony's fire and now called ergotism, which takes either a gangrenous or a hallucinogenic form.

Both ergot and the malady it causes were well known before Dodart wrote, although the connection between them was not. Descriptions of the symptoms and course of ergot poisoning were published by German authors in the 1590s and the first decade of the seventeenth century. Some writers confused ergotism with other illnesses, and some pointed out that bad food caused the attacks, but no one linked ergot grains to the illness they caused. Although some sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literature on ergot described its obstetrical uses or associated ergotism with the "honey-dew" stage of the fungus, Dodart was the first to publish the view that ergot grains caused Saint Anthony's fire and to explain why he thought so.[29]

Dodart's article and the Academy's research on ergot were stimulated by correspondence from physicians who already understood the causal relationship between ergot and Saint Anthony's fire. Four physicians — the Montpellier-trained N. Bellay, Paul Dubé, and a man named Tuillier and his

son — plus the surgeon Chatton sent the Academy their observations and samples of infected rye. All of them came from the rye-growing region of France that included the Sologne, Blois, and Montargis.[30] The correspondence began when the practitioners from Blois and Montargis wrote to Perrault and Bourdelin of their suspicions that spurred rye caused gangrene; they knew no warning signs of the illness and had found medication and surgery ineffective in treating patients. In 1674, after having received several communications, the Company instructed Dodart to investigate.[31]

The Academy's informants described the sufferings of patients afflicted with Saint Anthony's fire. The illness brought on "malignant fevers accompanied by drowsiness and dreams"; this was perhaps a reference to hallucination. It dried the milk of nursing mothers and "caused gangrene in the arms, and especially in the legs, which it usually struck first." Gangrene of the limbs was preceded by "a certain numbness in the legs," and as the illness continued its painful progress, physicians observed that there was

some swelling without inflammation, and the skin becomes cold and pallid. The gangrene begins in the center of the limb and appears in the skin only after a long time, so that it is often necessary to open the skin in order to find the gangrene inside.

Sometimes surgeons amputated the infected limb in the hope of halting the spread of the gangrene. If a limb was not amputated, it became "dry and thin, as if the skin were glued to the bones, and of a dreadful blackness, without rotting." Nonsurgical treatment included ardent spirits, volatile spirits, "orvietan," and a tisane of lupines.[32] If physicians could not agree on the course of the illness or the efficacy of various treatments, that was, according to Dodart, because the illness varied "according to time and place," which made it necessary to examine spurred rye from different areas in France.[33]

Ergotted rye had been found "nearly everywhere," but especially in "Sologne, Berry, the country around Blois," and in the Gâtinais. It was most likely to appear where the soil was light and sandy, and it was common "during wet years," and "especially when excessive heat followed a rainy spring."[34] Given these conjunctions, air, rain, and soil were the principal suspected causes of ergot. Based in Paris, the Academy could not test provincial air and rain, but Marchant grew rye in sandy soils brought to Paris from areas where ergot was common, and Bourdelin tested soils and grains.[35]

Dodart studied ergot grains and compared spurred rye with other cereals.[36] The fungus, called "ergot" in Sologne and "bled-cornu" in the

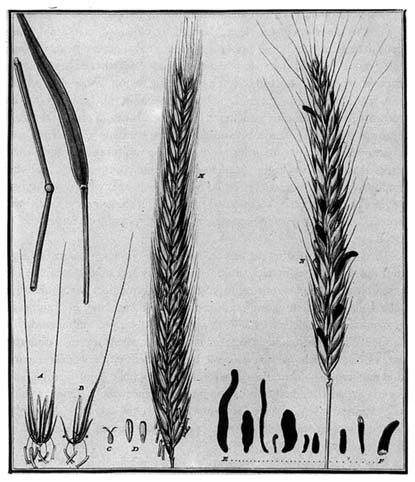

Gâtinais, appeared "black on the outside" and "rather white inside." When dried, it was harder and denser than rye grains, and Dodart found its taste not unpleasant. At the base of some ergot grains, he noticed "a substance with the taste and consistency of honey." This was the mucus, called "honey dew," which was the second or conidial stage in the development of ergot and which caused the growth of the sclerotium, or the ergot grain itself. "Infected grains" grew longer than normal grains, and Dodart observed that some were as large as thirteen or fourteen lignes long and two lignes wide. On a single blade there might be seven or eight spurs (plate 4).[37] Academicians and their contemporaries were uncertain whether ergot was the rye itself, distorted in shape and wholesomeness, or rather "foreign bodies produced among several grains of rye." Adherents of the former, incorrect view cited the resemblance of ergot to rye and the similar taste of breads made from ergot and from rye.[38]

Although it was widely doubted that the rotten rye caused the gangrenous sickness, Dodart believed that the absence of that malady except in persons who ate only rye bread, and the correlation between the appearance of ergot and the prevalence of the illness, argued in favor of ergot's being the cause. To verify this hypothesis, the Academy, like the elder Tuillier, ordered that bread made of ergot and rye be fed to animals.[39]

Dodart and his colleagues recognized that ergotism respected class lines. It was a malady of the country poor because rye bread was so important in their diet.[40] Seventeenth-century medical treatises routinely blamed mediocre food for illness among the poor.[41] Modern research has revealed just how bad that food was. In the Beauvaisis, a wheat-producing area, 75 percent of the peasants were "condemned to suffer hunger" in good years and "to starve to death" when the harvests were bad. The diet of peasants was not nutritious: it rarely included meat, milk, cheese, or fruit of good quality. Bread, gruel, and legumes formed the basis of a diet that was "both heavy and lacking in nutrition, insufficient during winter and increasingly so as spring approached."[42] The conditions in Beauvaisis resembled those in other areas of seventeenth-century France.[43]

Even during good years the peasants were chronically ill, and when times were bad, starvation and death were common. Thus, if the poor consumed rye they had grown themselves, hunger and ignorance prevented them from discarding spurred rye; sometimes hungry persons begged to be given the ergot already separated from rye, in order to make their flour go further.[44] Heavy demand for cereals, exacerbated by the army, large cities, and famine, tempted the unscrupulous to sell the ergot with rye.[45] Ignorance and circumstance led peasants to use rye infested with ergot.

Plate 4. Ergotted Rye. (Plate 111 of Bulliard, Histoire des plantes vénéneuses et

suspectes de la France . Paris: A. J. Dugour et Durand, [1798]; photograph

courtesy of Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Pittsburgh.)

When poor harvests threatened starvation, the populace traditionally looked to government for relief, demanding official intervention against private hoarding and high prices. Local and royal governments accumulated stores of grain for sale when there was a dearth and attempted to prevent export of foodstuffs from a producing region whose own population required them for survival.[46] Operating within this tradition, Dodart recommended legislation and hoped local officials would prevent the use of ergot as food. The Academy would assist by studying spurred rye from every region in France, in order to correlate the variations in ergotism with differences in rye and ergot. Academicians would continue to publish their findings so that magistrates could warn the people about the danger, require that all grain be sorted, and forbid millers to grind rye mixed with ergot, "which is so easy to recognize that it is impossible to mistake it" for good rye.[47]

Dodart was probably the first to publish the connection between ergot and the gangrenous malady, and academicians and others continued his research in the eighteenth century.[48] But many medical practitioners rejected the claim that eating ergot caused Saint Anthony's fire, and ergot poisoning was neglected even in treatises that discussed malnutrition and famine.[49] Because maladies were defined in terms of symptoms rather than causes, Saint Anthony's fire was usually conflated with erysipelas, scurvy, and gangrene as a skin disease. Even Dubé explained Saint Anthony's fire simply as "a Mixture of bileous and pituitous Humours" without mentioning ingestion of ergot.[50] Dodart's important article, therefore, had only a limited effect on magistrates, medical practitioners, or the principal victims of the malady.

The Academy's medical interests and Dodart's awareness of the social discrimination of certain illnesses may suggest that the Academy was sensitive to the needs of Louis's most numerous but least privileged subjects. But academicians were isolated by birth and training from most of the populace. They were academicians because they were known personally or by reputation to those in power, and indeed many of the medical practitioners admitted to the Company had served the royal family in some capacity. Academicians analyzed meat, fish, vegetables, and fruits, but these foods mostly represented the diet of only a quarter of the population of France. The Academy's notion of social responsibility was mainly irrelevant to the needs of the poor.

The Jansenist Dodart was more interested than his colleagues in such problems: he studied medicine for the poor,[51] treated the poor free of charge, and died as a result of an illness contracted from one of his indigent

patients.[52] But his sympathies did not prevent him from approving the use of prisoners as guinea pigs. Attitudes molded by social class shaped academicians' concepts of their social responsibilities. Dodart's work on ergotism represents only a modest effort by the early Academy to develop knowledge and legislation in the interests of the poor. Academicians, like their contemporaries, sought to improve the lot of the poor through ad hoc measures and took the social order as given. Thus, the Academy's posture is consistent with the entire pattern of old-regime reform, which conceived change always within the context of contemporary social and political structures.[53]