Preferred Citation: te Brake, Wayne. Shaping History: Ordinary People in European Politics, 1500-1700. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006j4/

| Shaping HistoryOrdinary People in European PoliticsWayne te BrakeUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1998 The Regents of the University of California |

For Nelva, Martin, Maria, and Nicholas

Preferred Citation: te Brake, Wayne. Shaping History: Ordinary People in European Politics, 1500-1700. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006j4/

For Nelva, Martin, Maria, and Nicholas

Preface

This work has been longer in the making than I imagined, and I would like to think that it is much the better for that fact. This apparent tardiness, I should add immediately, is not entirely my fault, as an impressively large number of people and institutions have emboldened and enabled me to write this small book about this enormous topic. The enormity of the topic is what I originally underestimated, and as a consequence the scope of my ambitions has changed dramatically even though my purpose has, I think, remained constant: to describe and account for the variety of ways in which ordinary people have shaped their own political histories. Thus I am especially pleased to acknowledge the generosity of those who have continued to support my work when it might have seemed that I had lost my bearings.

Indirectly, this book has its origins in my graduate work at the University of Michigan where a very special cohort of students and faculty introduced me to the interdisciplinary challenges of social history, contentious politics, and historical comparison. But more directly, it originated in a memorable conversation, over lunch at a favorite haunt in Greenwich Village, with two friends whose academic lives have intersected with mine in countless ways both before and since. In the summer of 1990, as I anticipated a whole year of research and writing at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS), Michael Hanagan and Charles Tilly urged me to spend at least some portion of that year sketching out what I imagined to be the larger comparative context in which a dynamic, social, and internally comparative history of popular politics in the Dutch Republic, which I had proposed to write, would be as salient to our understanding of the course of European history as I claimed it would be. I readily agreed, but I have been wrestling with the implications of that agreement ever since. Now, if all the wrestling has been fruitful, I imagine Mike and Chuck deserve some of the credit; if not, I’ll take all the blame.

One of the genuine privileges of a year at NIAS is that with the support of its excellent staff and the encouragement of one’s colleagues, one can indeed wrestle with the implications of an apparently simple commitment to explore the larger comparative dimensions of an otherwise parochial research project. To be sure, I continued to lecture, write, and organize a conference on the history of contentious politics in the Dutch Republic, but by the end of that year, it was clear that I was merely at the beginning of a much larger project that has taken me far beyond the familiar boundaries of the Dutch confederation and back in time, not to the middle of the seventeenth century, but to the beginning of the sixteenth.

Since then, a number of institutions have helped to keep this project going and to bring it to its conclusion. In the summer of 1992, the Maison des Science de l’Homme, under the direction of Maurice Aymard, generously supported six weeks of very productive work in Paris, and in the summer of 1993, Professor Harry S. Stout, Master of Berkeley College at Yale University, provided both a place to work and access to the wonderful resources of the Sterling Memorial Library. Though a bicycling accident interrupted my work in the summer and fall of 1993, I was able to make up for some of the lost time during a sabbatical leave from Purchase College in the fall of 1994, during which time the Maryknoll School of Theology in Ossining provided a haven for work away from home. Then, in the winter of 1995, the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation awarded me a very generous two-year research grant that promised initially to interrupt my work on the social history of popular politics by focusing my attention on the “cultural politics” of religious war in early modern Europe. Much to my delight, however, this new research proved to be a substantial enrichment of my by then “old” research, and in the end gave a mighty stimulus to the completion of this work. For all of this tangible faith in the promise of my work, I am deeply grateful.

Various versions of the chapters that follow have benefited from the critical suggestions of a number of colleagues as well as numerous seminar and lecture audiences in both Europe and North America. On several occasions over many years, the Center for Studies of Social Change at the New School for Social Research, and especially the proseminar on state formation and collective action, provided a stimulating context for the discussion and development of my work. I would also like to thank especially Anton Blok, Jeff Goodwin, Lise Grande, Michael Hanagan, Marjolein ’t Hart, Dan Kryder, Kelly Moore, Olaf Mörke, Henk van Nierop, Maarten Prak, Michelle Stoddard, John Theibault, David Underdown and Dale Van Kley, all of whom read and commented on at least one piece of the manuscript without seeing the whole. Risto Alapuro, Robert M. Stein, and Charles Tilly gave me the great benefit of careful and very constructive readings of the entire manuscript. As always, Bill te Brake helped me think it all through from the very beginning.

At the University of California Press, Stanley Holwitz gave me invaluable support and encouragement from a very early date, and I am very grateful for his constancy throughout this long project. Meanwhile, my students in European history courses at Purchase College were the first audience for most of the ideas contained in this work; to those who were subjected to the half-baked versions, I offer my apologies. My graduate students at Yale University in the spring of 1997 encouraged me to do one last revision of several of the figures, and their influence should be readily visible to them. Finally, at the very last moment, Fausta Navardo and Eric Nicholson very generously helped me to acquire the cover illustration.

In more ways than they will ever know, my family—Nelva, Martin, Maria, and Nicholas—has helped me keep both my bearings and my sense of humor. They are always willing to celebrate the good times, but in this case they literally had to nurse me through the bad. This work is dedicated to them; I hope it is a worthy offering.

Ossining, New York

April 1997

1. Breaking and Entering

[In the pre-industrial era,] those engaging in popular disturbances are sometimes peasants.…but more often a mixed population of what in England were termed “lower orders” and in France menu peuple. . . ; they appear frequently in itinerant bands, “captained” or “generaled” by men whose personality, style of dress or speech, and momentary assumption of authority mark them out as leaders; they are fired as much by memories of customary rights or a nostalgia for past utopias as by present grievances or hopes of material improvement; they dispense a rough-and-ready kind of “natural justice” by breaking windows, wrecking machinery, storming markets, burning their enemies of the moment in effigy, firing hayricks, and “pulling down” their houses, farms, fences, mills or pubs, but rarely by taking lives.

Thus, in sixteenth-century France, we have seen crowds taking on the role of priest, pastor, or magistrate to defend doctrine or purify the religious community—either to maintain its Catholic boundaries and structure, or to re-form relations within it. We have seen that popular religious violence could receive legitimation from different features of political and religious life, as well as from the group identity of the people in the crowds. The targets and character of crowd violence differed somewhat between Catholics and Protestants, depending on their sense of the source of the danger and on their religious sensibility. But in both cases, religious violence had a connection in time, place, and form with the life of worship, and the violent actions themselves were drawn from a store of punitive or purificatory traditions.…Even in the extreme case of religious violence, crowds do not act in a mindless way.

All of these [seventeenth-century French] risings involved significant numbers of peasants, or at least of rural people. Their frequency, and the relative unimportance of land and landlords as direct objects of contention within them, require some rethinking of peasant rebellion. The universal orientation of these rebellions to agents of the state, and their nearly universal inception with reaction to the efforts of authorities to assemble the means of warmaking, underscore the impact of statemaking on the interests of peasants.…In the seventeenth century the dominant influences driving French peasants into revolt were the efforts of authorities to seize peasant labor, commodities, and capital.

One of the most significant developments in European historical studies in the last four decades has been the explosion of research that allows us to take ordinary people seriously as political actors long before the creation of stable parliamentary democracies. Inspired variously by such well-known examples as George Rudé’s project of identifying the “faces in the crowd,” Natalie Zemon Davis’s careful elucidation of the “meaning” of riots and popular protests, and Charles Tilly’s account of the changing patterns of “popular collective action,” literally hundreds of scholars have set off to the archives to discover the particulars of what we might label the history of popular politics. Over the years their research has not only enriched our sense of the variety of actors but also revealed the diversity of their political messages and the range of their actions. Never before have ordinary people—which is to say, those who were excluded from the realm of officialdom; subjects as opposed to rulers—seemed so active and noisy, so eminently capable of shaping their own history.

So what kind of history did these ordinary Europeans make? In what concrete ways did ordinary people influence and shape their political destinies? To what extent can ordinary Europeans be said to have created their own political futures rather than being condemned merely to suffer the impositions of their more powerful superiors? Given the richness and diversity of the accumulated research, it may be somewhat surprising that there have been very few attempts to synthesize the results, but on the face of it, most historians will find questions like these to be hopelessly broad and impractical. To date, those authors who have sought to reassemble the myriad pieces of popular microhistory into larger packages have either limited their work to a certain category of events—such as urban riots or peasant rebellions—or focused on a relatively bounded territory—typically the domain, or some subunit, of a modern national state. Given the large and linguistically diverse literature, such limiting strategies are obviously practical, but the history of popular politics surely transcends the territorial boundaries of provinces, national states, and linguistic groups and defies the categorical limits that separate “riots” from “rebellions,” “revolts” from “revolutions,” and the whole lot of such events from merely nonviolent action. Indeed, unless we intentionally ask questions that transcend the categorical limits and the territorial boundaries of the current literature, we will never find the answers and thus squander the excellent opportunity we now have to replace the old elite-centered histories of European politics with something significantly new.

Building on the accumulated studies of popular collective action, then, this book attempts to synthesize what might usefully be called the social history of European politics during the particularly tumultuous era that began with the Protestant Reformation and ended with the so-called Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. If social history is concerned with how ordinary people actively “lived the big changes” in history (Tilly 1985: 11), then the “early modern” period is an especially valuable laboratory, not only because of the voluminous literature on popular political behavior, but because it is replete with “big changes.” Besides the disintegration of the Roman Catholic church and the consequent reshaping of the European cultural and political landscape, this period also witnessed both the rise of a European world economy and a military revolution that inaugurated the era of European domination on a global scale (see Wallerstein 1974, 1980; Parker 1988). In highlighting the political action of ordinary people in relation to the transformation of the cultural and political landscape of Europe, this study naturally takes issue with a number of scholarly interpretations of these big changes. It explicitly undermines elite-centered accounts of both the Reformation and the consolidation of a peculiarly European system of states, but it also questions more implicitly the direct correlation of capitalist development and changes in warfare with the emergent patterns of state formation in early modern Europe. In a far more constructive sense, however, my primary goal is to describe and account for the variety of ways in which ordinary people, by breaking their rulers’ exclusive claims to political and cultural sovereignty and boldly entering political arenas that were legally closed to them, helped to shape the cultural and political landscape of modern Europe.

| • | • | • |

Toward a Social History of European Politics

Before we set off on this synthetic quest, it is important to recognize just how far we have already come and to clarify some of the concepts that are essential to the book’s argument. Let us begin in the realm of political history by underscoring how far we are now removed from the days when historians were primarily concerned with recording or glorifying the deeds of (monarchical) rulers and their principal (military) agents. Even when elite patronage of historical writing gave way in the nineteenth century to professionalization in university departments, (political) historians still focused on war making, diplomacy, and courtly intrigue during eras characterized by “feudalism,” the “new monarchies,” or “absolutism”; they magisterially assigned praise or blame to the leading actors depending on their apparent success or failure in the story being told. More recently, however, historians who are directly concerned with politics have, on the whole, become much more critical of the “official story” embedded in the archives and annals of those who claimed authority over the lives of ordinary people. Focusing on the routine practice as opposed to the theoretical claims of early modern government, we now realize, for example, just how indirect and limited the authority of even “absolute” monarchs actually was; indeed, one very thoughtful analysis has recently described the “myth of absolutism” as the now-moribund product of sixteenth-century anti-French propaganda filtered through the distorting lens of nineteenth-century nationalism (Henshall 1992; see also Collins 1995). At the same time, closer attention to the differences among European states has undermined the notion of a singular, normative path of European political development and yielded instead to a more broadly comparative understanding of divergent paths of early modern state consolidation in relation both to the economic geography of preindustrial Europe and the changing fortunes and technology of war (see Rokkan 1975; Blockmans 1989; Tilly 1990; Downing 1992; Ertman 1997).

The research agendas of social historians have also changed dramatically. George Trevelyan, combating the hegemony of political history, asserted for better or worse that social history was history with the politics left out; in a similar vein the French Annales school defiantly distinguished between the longue durée of social, economic, and even geological processes and the mere events of political history. Not surprisingly, the social history that first gained a toehold within history curricula often emphasized the enduring social and demographic structures of premodern societies and the conservatism or even the immutability of “traditional” cultures. Still, a few pioneers like Natalie Davis, George Rudé, and Edward Thompson doggedly explored the interfaces between social and political history, identifying the faces of individual actors within riotous “crowds” and interpreting the often symbolic meaning of politically contentious action by ordinary people. Others, such as Barrington Moore, put macrohistorical questions on the research agenda—questions that linked the political actions or alignments of ordinary people with macrohistorical processes like state formation and the rise of capitalism. Still others, such as Charles Tilly and Yves-Marie Bercé, proposed that violent conflict and rebellion provided especially valuable clues to popular political aspirations and capacities because authorities usually documented them with care. Each of these strands proved to be valuable in itself, yet a healthy eclecticism and cross-fertilization have served to retard the growth of mutually antagonistic schools or camps. Gradually, then, the study of “collective action” or “collective violence” in general and “crowds,” “riots,” and “popular protest” in particular became quite respectable as a specialized field of inquiry within social history.

The problem is that in explicating collective behavior or reconstructing the microhistory of particular events—that is, by focusing on ordinary people as intentional actors—the current social-historical literature separates popular politics from the main line of political history. Indeed, the political actions of ordinary people are typically the explicandum—that which needs to be explained by independent variables outside the realm of popular politics—rather than a part of the explanation of large-scale historical change. The unfortunate result is that popular political actors are more often than not portrayed as the noble, if largely ineffectual, victims of larger historical processes far beyond their control. The challenge for the next generation of research is, as I see it, to move beyond the study of intentional action to the exploration of consequential action—to link the more fragmented histories of popular political action with the newer accounts of varied political development within Europe in ways that allow us to see the extent to which ordinary people were fully fledged political actors, capable of shaping their own history. In other words, the specific task of the social historian of European politics is to explore the ways in which ordinary people were directly implicated in larger causal sequences that can be said to account for the different paths of political-historical change.

To envision this kind of comparative social history of politics, it is essential to define “politics” in sufficiently broad and inclusive terms—in terms that diminish the salience of such hoary questions as whether ordinary people were political or when they finally became political and highlight instead the variety of ways in which they actually were political prior to or outside the institutionalization of some form of popular sovereignty. To this end, it is useful to regard politics as an ongoing bargaining process between those who claim governmental authority in a given territory (rulers) and those over whom that authority is said to extend (subjects).[1] As unconventionally vague as it may seem at first blush, this is a relatively restrictive conception of politics in the sense that it singles out the interactions between rulers and their subjects or citizens.[2] It is thus not concerned with relations of power as such; nor does it focus directly on the “politics” of the bedroom or the “politics” of the workplace. This is nevertheless an expansive notion of politics in the sense that it includes within the scope of the political bargaining process, for example, popular protests that fall short of demands for the direct exercise of political authority and political movements that develop outside the realm of electoral or directly representational political systems. What makes “ordinary” people ordinary in this strictly political sense is their status as political subjects. Thus in situations in which power is concentrated in a very few hands, it is quite possible that people who in a social, economic, or cultural sense could hardly be described as ordinary are nevertheless usefully seen as “ordinary” political subjects. By extension, what makes “popular” politics popular is its position relative to the domain of rulers and the politics of the official “elite.”

To see politics as an interactive bargaining process, however, is also to insist that variations and changes in the realm of popular politics cannot be treated in isolation from variations and changes in the structures of political power or, broadly speaking, the history of state formation. This means that a history of popular politics in early modern Europe, in particular, must take into account not only the long-term consolidation (or disintegration) of power within specific polities but also the gradual elaboration of an interactive system of states within Europe as a whole. But how are we to conceive of the relationship between the history of popular politics, often enacted at the local level, and the history of state formation on a much grander scale? A volume of essays on the relations between cities and states in Europe suggests a useful point of departure that allows us to build on the most recent literature: “In Europe before 1800 or so, most important changes in state structure stemmed from rulers’ efforts to acquire the requisites of war, from resistance to those efforts, and from bargains that ended—or at least mitigated—that resistance” (Tilly and Blockmans 1994: 10). In this way, the ongoing bargaining process between subjects and rulers, which includes, for example, the pattern of tax revolts and conscription riots that punctuated the political history of Europe from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, necessarily becomes a central concern within any convincing account of European state formation. But even more important, such a focus on political interaction takes us beyond the motives and intentions of political actors and highlights instead the often unintended consequences of the political bargaining process. This is not to say, of course, that motives and intentions are irrelevant; rather, in the absence of reliable or unequivocal evidence in this regard, as is often the case, we can nevertheless treat popular political action as an integral part of the political process.

It is fundamentally mistaken, however, to assume that the history of popular politics is for the most part the tragic story of an essentially reactionary and futile resistance to the inexorable rise of a system of national states. First, we know that not all resistance to the claims of European governments was or is futile. Indeed, as we shall see in the account that follows, in the most obviously successful cases of resistance to Habsburg dynasticism, popular political action helped to precipitate and fashion entirely new polities like the Swiss Confederation and the Dutch Republic (Brady 1985; Parker 1985; Duke 1990). In other less spectacular cases, like the widespread and predictable resistance to increasing taxation, popular action could bend and shape public policy in significant ways even though resistance was not always expressed in open revolt and most tax revolts did not result in revolutionary transformations of power (see Dekker 1982; Schulze 1984; Scott 1987; Briggs 1989; Robisheaux 1989). Second, it is obvious that the claims that European rulers made on their subjects varied significantly in time and place. In the realm of taxation alone, both the character and the extent of the state’s fiscal exactions separated the more agrarian regions of Europe from their more commercialized neighbors, creating disparities not only between states but also within them (see ’t Hart 1989; Tilly 1990; Collins 1995). Likewise, the patterns of military recruitment and judicial authority in Europe offered quite variable challenges and opportunities to rustics and city folk, to the inhabitants of Europe’s urban, commercialized core and its more rural, agrarian periphery. But in this period it was frequently the forceful claims of a variety of rulers to an unprecedented degree of cultural sovereignty—that is, final decision-making authority in matters of religious ritual and belief for whole polities—that were met variously with resistance or approval among their subject populations. It is precisely the relationship between the resistance or cooperation of subjects and the variably enforceable demands of rulers that we need to explore through broadly conceived and systematic comparison. Finally, and perhaps most important, it is clear that not all popular political action was simply reactive; indeed, as I shall argue below, when it was directed toward the reformation of religious ritual and belief, the political action of ordinary people could serve to legitimate or extend the authority of their rulers in surprising ways. For all these reasons, then, it is important to replace the easily romanticized concept of popular “resistance” with the less colorful but more flexible and inclusive concept of “popular political practice.”

| • | • | • |

The Spatial and Cultural Dimensions of Political Interaction

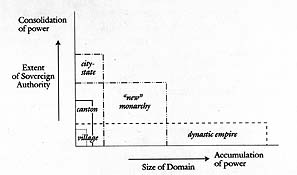

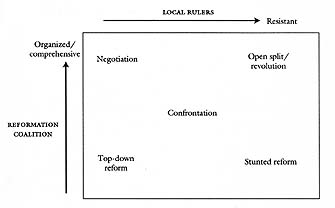

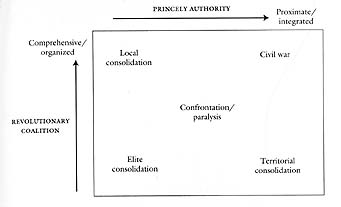

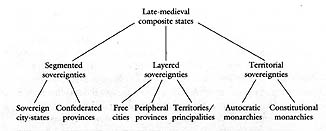

To reconstruct the social history of politics, then, we need not only to examine the variable forms of popular political practice but also to situate them within the different political contexts in which popular political action takes place. Traditional accounts of European state formation, highlighting selected aspects of the experience of a few relatively centralized and autocratic monarchies, suggested a fairly direct, linear development from feudal monarchies to national states in the period between, say, 1200 and 1850 (cf. Strayer 1970). In fact, however, Europeans lived in a wide variety of political contexts at the end of the Middle Ages and, having started in different circumstances, experienced the process of state formation along widely divergent paths. To look simultaneously and comparatively at political interactions in these diverse and changing contexts, then, it is useful to think of the interactive bargaining process of politics in spatial terms. A “political space” can be defined as an arena, bounded in terms of both authority and territory, within which political bargaining can occur. The dimensions of such a political space vary, on the one hand, according to the extent to which those who rule within it exercise sovereign authority—that is, they can make independent, enforceable decisions with regard to issues of importance to their subjects—and, on the other, according to size of the domain—the physical territory and the population—over which that sovereign authority extends. Figure 1 suggests how we might visualize the dimensions of different kinds of political space.

Fig. 1. Variable dimensions of political space

Using this formulation of the concept of political space, it is possible to highlight graphically the differences among polities in a particular era. Around 1500, for example, city-states like Venice, with a broad range of authority concentrated in its ruling oligarchy, would stretch toward the upper left of the diagram. Dynastic empires like the expansive Habsburg imperium, by contrast, would extend toward the lower right. Village communes, with authority to make critical decisions over communal property, for example, would show up in the lower left whereas a small canton like Luzern within the Swiss Confederation concentrated an impressive degree of sovereignty, short of making war, in the hands of its magistrates. The so-called new monarchies, like the France of Francis I, would extend closer to the middle of the diagram with the proviso that the sovereign reaches of their royal governments typically exceeded their grasps.

This concept of political space also allows us to distinguish more fundamentally between two important dimensions of historical change that are frequently conflated in the notion of state formation, which in most iterations bespeaks the teleology of the modern “national” or “consolidated territorial” state (cf. Ertman 1997). In the early modern period especially—the period in which the European system of states first took shape—one must distinguish between the accumulation of power that typically resulted from a dynastic policy of adding new pieces of territory to an existing domain through skillful marriage alliances, inheritance, and conquest and the consolidation of power that was entailed in the extension of governmental authority over matters of consumption, welfare, and religion. Such distinctions obviously reflect, at bottom, the pretensions or claims of putative state makers because it is these claims that frame the extended conversations that constitute the political processes we are considering here. But the political bargaining process does not follow the directional schemes and tendencies of rulers alone. From the point of view of their political subjects, of course, movement toward the upper right along the diagonal of figure 1—that is, essentially the old, idealized linear development from feudal principalities to national states—undoubtedly seemed less desirable or inevitable than it did from the perspective of those who sought to augment and consolidate claims to sovereignty within territorial states. The point is, however, that neither the state maker’s nor the state resister’s perspective is sufficient. On the contrary, the actual trajectories of political development in Europe must be seen as the product of the interacting claims and counterclaims of rulers and subjects in changing times and variable spaces. To be sure, the pretensions of Europe’s many rulers conditioned and channeled the political choices available to ordinary people, but choices there always were.

Since a political space can only be entered or filled by actors who are able to mobilize or deploy resources appropriate to it, the mobilization or deployment of resources within a political space can be usefully seen as both a political and a cultural process.[3] Among the existing opportunities for meaningful action afforded by specific social and political circumstances, all actors—both rulers and subjects—make choices that are bounded and mediated by cultural experience. As circumstances change, however, these actors learn to express new kinds of claims and to invent new forms of claim making.[4] Indeed, to describe and account for the choosing, the learning, and the inventing that ordinary people do in the course of filling the political spaces available to them may be considered one of the central analytical problems of the social history of politics. For it is precisely in the realm of choosing, learning, and inventing that ordinary people can be said to be making their own political history—to be shaping and enforcing essential, if often informal, bargains with their rulers.

Looking at the history of popular politics from a cultural perspective entails several different kinds of analysis. At the microhistorical level of particular communities and specific events, it is important to try to discern the political significance of often symbolically expressive collective action; for within the larger comparative history of popular politics, it is important to think of expressive actions like demonstrations and riots as an integral part of an interactive political process—as statements within an ongoing conversation. Since political bargaining requires communication, the various signs and symbols of popular collective action afford us invaluable glimpses of the range of social and cultural resources that ordinary people draw on in entering and filling the political spaces available to them. But given that repression or reprisal is a constant threat in most forms of political domination, much of the political action of subordinate populations “requires interpretation precisely because it is intended to be cryptic and opaque” (Scott 1990: 137). Though it is fraught with epistemological uncertainties, the careful description and explication of various forms of popular collective action is a well-established problem in microhistorical research; indeed, it continues to be one of the most inventive and inspiring developments within the realm of “history from below.” [5]

On a rather different plane, it is important to analyze and account for the cultural dynamics and consequences of multiple political interactions within particular polities, those that occur in concentrated clusters in revolutionary situations as well as more attenuated series of challenges and responses.[6] In his general accounts of the changing “repertoires” of contention in France and Great Britain, Charles Tilly (1986, 1995) explicitly uses the metaphor of jazz improvisation to suggest the cultural dimensions of the long-term history of popular political action. In his work on social movements, Sidney Tarrow (1989, 1994) also suggests more generally how we might link cycles of protest (as distinct from revolutionary situations) to cycles of reform, stressing in particular how these cycles produce and replicate innovations in the language and techniques of popular collective action. What is especially important about such relatively rare events as revolutions and widespread cycles of protest is that they usually reveal the hidden dimensions of a particular political culture.[7] But it is equally important to be attentive to subtler and less spectacular yet equally direct challenges that are often allowed within the rules of established regimes (cf. Beik 1997). Taken together, the generally accepted rules of political behavior—that is, the culturally specific “legitimacy” of political action undertaken by both subjects and rulers in specific historical settings—as well as the overall dimensions of what James C. Scott (1990) calls the “official transcript” may be said to constitute the dominant political culture of any given political space.

This last point brings us to the critical question of cultural innovation and, in particular, the role of ordinary people in the process of political-cultural change. This problem especially requires both a long-term and an internationally comparative perspective; for, as it happens, the most profound changes in political culture often emerge only gradually over long stretches of time, and they are often confirmed and maintained as a function of conflict and change within the larger system of states.[8] Meanwhile more or less routinized oppositions within a particular polity sometimes belie fundamental agreements in the realm of political discourse that are only evident when they are compared to other more or less routinized oppositions (cf. Schulze 1984; Prak 1991; Underdown 1996). The gradual rise and ongoing mutation of a militarily competitive system of variously sovereign states and within those states the gradual assertion and legitimation of a variety of forms of political sovereignty are but the most obvious and perennially intriguing political-cultural transformations in modern European history. The central argument of this book is that none of these innovations can be said to be the product of a specific era or of a particular polity; neither can they be said to be the work of rulers alone.

| • | • | • |

Ordinary People in European Politics (ca. 1500)

To understand more clearly the history and significance of popular political practice, we must come to a fuller appreciation of both the variety of political opportunities that political subjects enjoyed and the larger consequences of the choices that popular political actors made. The analysts of modern social movements often speak of political opportunity structures outside the “normal” channels of electoral politics; stripped of its present-minded assumptions about electoral politics, this idea of geographically and temporally variable structures of political opportunity can be especially useful in the study of “informal politics” in other times and places, especially in those circumstances in which most people are excluded from formal political participation altogether.[9] In the first instance, of course, political opportunities are framed by the specific institutional structures through which rulers exercise their authority, and in this regard the relative openness of formal political structures to popular political bargaining is conditioned by the historically specific limits of governmental coercion or repression. But beyond that we can identify a number of significant variables: the relative stability of political alignments within the polity; the availability to popular political movements of influential allies; and the degree of political division among established political elites. But what is especially important (if also complicated and confusing) for understanding popular politics in the early modern period is to disentangle the multiple and overlapping structures of political opportunity that were obviously inherent within composite states.

At the beginning of the early modern period, around 1500, most Europeans lived within composite states that had been variously cobbled together from preexisting political units by a variety of aggressive “princes” employing a standard repertoire of techniques including marriage alliances, dynastic inheritance, and direct conquest. Some composites, like the Kingdom of England and Wales or the complex mosaic of pays d’élections and pays d’états in France, were composed of largely contiguous territories; others, like the Spanish Habsburg monarchy (created by the dynastic union of Castile and Aragon, each in itself a composite) or the Habsburg imperium more generally under Charles V, were separated by other states or by stretches of sea (Koenigsberger 1986; Greengrass 1991; Elliott 1992). Since the dynastic “prince” promised to respect the political customs and guaranteed the chartered privileges of these constituent political units, ordinary political subjects within composite states acted in the context of overlapping, intersecting, and changing political spaces defined by often competitive claimants to sovereign authority over them.[10] To the extent that they were oriented to a variety of political spaces defined by a variety of rulers, ordinary people could choose not only when and how to challenge the authority of their rulers but also where. As we shall see below, it was often in the interstices and on the margins of these composite early modern state formations that ordinary people enjoyed their greatest political opportunities.[11] By choosing to oppose the claims of some putative sovereigns, ordinary Europeans were often deliberately reinforcing the claims of constitutionally alternative or competitive rulers who were willing, at least temporarily, to meet their demands or to discuss their grievances and thereby to legitimate their political actions. In composite states especially, political opposition usually entails political alignment as well.

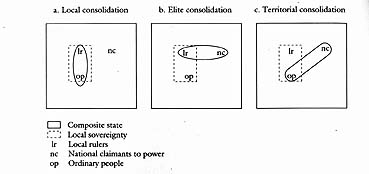

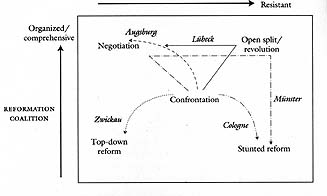

But what practical difference might the choices of popular political actors make? At the very least, a composite state involves three sets of actors: local rulers, national claimants to power, and ordinary political subjects. Figure 2 not only illustrates the obvious political alignments possible within such a state, it specifies the consequences that these different choices/alignments imply. In the first of these alternatives, ordinary political subjects align themselves with local rulers who are willing to champion their perceived interests vis-à-vis a more distant overlord and thereby help to consolidate local self-regulation and decision-making authority. In the second, local rulers align themselves with national claimants vis-à-vis their mutual subjects, thereby reinforcing their political interdependence in what I have called elite consolidation. In the third case, ordinary people align themselves with a more distant overlord who is willing to champion their interests vis-à-vis less responsive or more demanding rulers at home, thereby underwriting the consolidation of a broader territorial sovereignty at the expense of local self-determination.

Fig. 2. Alignment of political actors within composite states

By its very nature, this kind of complex political arrangement may be said to be particularly volatile because an alignment between any two of the actors promises to exclude the third; at the same time, the continued existence of the third represents the potential for two alternative alignments that implicitly threaten the status quo. Figure 2 nevertheless underestimates the complexity of politics within composite states in at least two important ways. As we shall see below, the constitutional layering of authority can entail more levels than “local” and “national,” with district and regional or territorial rulers frequently claiming a piece of the existing “sovereignty.” [12] At the same time, each of the principal actors is as often as not subdivided by internal rivalries and competing interests/objectives, producing situations in which all of these competing alignments appear at once; such situations might then be considered “revolutionary” if and when the alternative alignments make and attempt to enforce exclusive political claims that, if accepted, would eliminate their rivals.[13] For our purposes, what is especially instructive about even the stylized alternatives represented in figure 2 is the way in which ordinary people remain salient and potentially decisive actors even under political conditions that appear to guarantee the long-term survival of elite consolidation.[14]

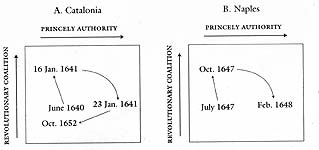

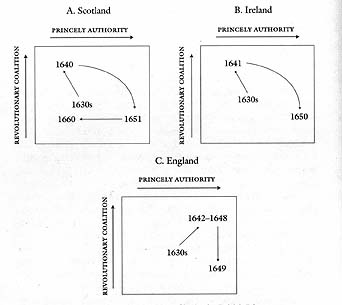

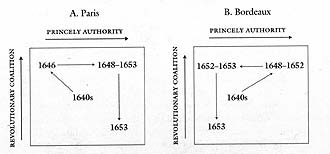

Emphasizing the spatial and cultural perspectives on popular political practice within late medieval composite states, then, the chapters that follow explore the variety of ways in which ordinary people actively lived the “big changes” in European political history during the early modern period. Chapter 2 begins the story in the first half of the sixteenth century and focuses on the political process of religious reformation in the fragmented political context of the German-Roman Empire; it nevertheless locates the popular reformations of Germany and Switzerland within a larger comparative analysis of the role of popular political action in the Comunero Revolt in Castile and the “princely” reformations of Scandinavia and England. Chapter 3 examines the political dimensions of the “Second Reformation” in France and the Low Countries where the initial repression of religious dissent yielded to decades of civil war and revolution in the second half of the sixteenth century; again the emphasis is on the character and significance of popular engagement within these complex struggles over political and religious sovereignty that by the end of the sixteenth century produced three very different paths of political development. Chapter 4 analyzes the political dimensions of the Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, focusing in turn on distinct clusters of revolutionary struggles in Iberia and southern Italy, the British Isles, and France; against the backdrop of the sixteenth-century reformations, this chapter explores the significance of popular political action in accounting for the varied outcomes of large-scale revolutionary challenges to the rulers of composite states.

Each of these chapters—which together constitute a sort of dramatic development in three chronologically sequential acts—takes us from one region to another investigating the variant patterns of interaction among national powerholders, local rulers, and ordinary people; each chapter also develops a framework for understanding the particular interactions and historically specific range of variation evident in the cluster of conflicts in question.

Chapter 5 takes stock of the larger historical patterns brought out in the previous chapters; it assesses the cumulative outcome of some one hundred fifty years of political and religious conflict in specific polities, not in terms of an essentially static ancien régime, but as a set of variant trajectories of political development in which the interactions of subjects and rulers, in one time and place, limit and channel the next round of interaction but do not strictly determine the outcome. In conclusion, then, this book argues that the political engagement of ordinary political subjects needs to be taken systematically into account in any explanation of the political features of the “new regime” that gradually came into focus across the European continent in the second half of the seventeenth century.[15]

This, I hasten to add, is not an exclusive argument. It does not suggest, for example, that ordinary people were either the principal architects or the primary beneficiaries of the new structures of European politics or the new system of European states that rose from the ashes of “religious war.” On the contrary, this work seeks to improve on previous accounts of the varieties of European state formation by tempering essentially ruler-centered or structurally determined models with the perspective of popular political practice and to augment the generally teleological research on the unitary sovereignties of territorial states with a specific concern for the consolidation of fragmented and layered sovereignties. Nor does this argument eclipse or undermine the value of more focused analyses of the modes of political action within specific polities or of detailed local research on particular events. Rather, it seeks to develop an analytic vocabulary and articulate a comparative framework through which it will be possible to ask sharper and more discriminating questions about the efficacy of popular politics in specific instances.

To accomplish all this in the course of a small book, my aim has been illustrative rather than comprehensive, and treatment of any given polity or region within the European political landscape is episodic at best. To some extent, this is simply reflective of the existing literature, which tends to be localized, discontinuous, and geographically uneven. To the extent that my choices of illustrative material were not merely dictated by the literature (or my limited access to it), however, I have generally placed more emphasis on exploring the broadest range of variation in each of these eras than on providing uniform or continuous coverage of any or all polities. Thus, while I have drawn a disproportional share of my examples from those parts of Europe north of the Pyrenees and Alps and west of the Oder, I am reasonably certain that I have encompassed the broad range of political variations evident within all of Europe’s composite states. In any case, it was by no means my intention, in my choice of examples, to marginalize southern or eastern Europe or to privilege the politics of Latin Christendom.

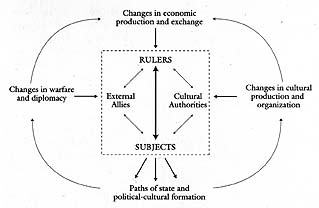

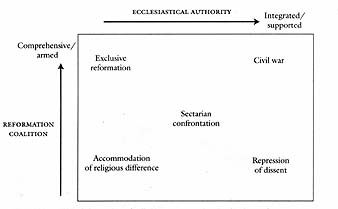

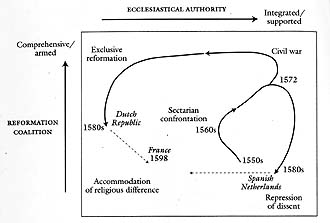

Before setting out on this broadly comparative and essentially episodic exploration, however, it is important to ask how we might conceive of the more continuous dynamics of political development in any specific polity in the longue durée. Since our basic problem is to describe and account for the specific histories of state and political-cultural change that were embedded in the European system of states as it emerged in this period, figure 3 represents an axial model of the general argument that popular political actors were an integral part of these large-scale historical processes of political development in European history. As the diagram suggests, the heart of the story is the interaction or bargaining between governmental authorities (rulers) and popular political actors (subjects) which can be said to account for the path of state and political-cultural formation within specific political domains. Yet, as the figure also suggests, the interactions of rulers and subjects are channeled and limited in a variety of ways. In the early modern period especially, it is important to recognize two analytically distinct sorts of secondary actors who were implicated in politics at all levels. On the one hand, those who claimed cultural authority—often by virtue of their positions within more or less formal institutions like churches, schools, learned academies, religious communities, and voluntary associations—were deeply implicated in the competitions and conflicts between rulers and subjects, variously reinforcing or undercutting the claims of the principal political actors, not just in the explicitly religious conflicts of the Protestant Reformation but across the Continent and throughout the entire period. On the other hand, external allies often intervened directly in “domestic” conflicts, not only in revolutionary situations, but more routinely in constitutionally layered articulations of fragmented sovereignty within composite states.

Fig. 3. Historical dynamics of political interaction

As the newer accounts of path-specific state formation have shown, both the fortunes of war and diplomacy within the state system and the cyclical development and geographic differentiation of emergent capitalism have important implications for the organization and exercise of power. My account insists, however, on their variable impact on subjects and rulers alike, especially in the way that wars and economic change altered the distribution of politically important resources to all political actors. To this standard list of environmental conditions—that is, large-scale changes that transcended the boundaries of particular polities—I have added changes in the organization and production of culture. Especially during this period the spread of new printing techniques, the disintegration of the Roman Catholic church, and the rise of mass literacy helped to reconfigure the choices and channel the cultural resources available to all political actors within any given space. Altogether, then, the environmental conditions and the specific dimensions of the political domain can be said to structure the political opportunities but not to determine the choices of rulers as well as subjects. On the outcome side of the diagram, the closely linked trajectories of state and political-cultural formation can be seen as the institutional and cultural residue of historically specific interactions between rulers and subjects, which, in turn, influenced the environmental conditions and channeled the next round of political interaction.

A comprehensive or authoritative account of the big changes in European politics during this tumultuous period might well treat the environmental conditions and the political interactions in equal measure. This work focuses, however, on political interaction within historically specific political spaces and, by comparison, generally takes the changing environmental conditions for granted. While I want clearly to acknowledge the importance of these changing conditions, I want equally clearly to undermine the assumption that one can reason directly from structural conditions to political outcomes. On the contrary, what this work aims to demonstrate is that by starting in the middle—by focusing on political interaction as the heart of the story—we will finally be able to move beyond both elite-centered and structurally determined accounts of European state formation to describe and account for the various ways in which ordinary people were active and creative participants in the formation of the modern political landscape.

Notes

1. Cf. Reddy 1977: 89, who notes the shortcomings of bargaining theories of popular politics; he argues, in particular, that “the idea of political bargaining short circuits the question of political legitimacy.” Here the idea of an ongoing political bargaining process will not be taken to exclude popular challenges to claims of political legitimacy made by or on behalf of their rulers. My argument is simply that such challenges are not different in kind from more routine political interactions where the legitimacy of established or putative rulers is not immediately or overtly at stake; indeed, all forms of extralegal or extraconstitutional political action can be said to strain at the boundaries of political legitimacy. See also Tilly 1978; Scott 1987;Tarrow 1989.

2. It is important to note, of course, that not all people who by this definition will be considered political subjects would choose this as an acceptable self-description. This applies equally to the early modern “burgher” and the modern “citizen.” Still, the individual liberties or collective sovereignties typically claimed by burghers and citizens notwithstanding, the basic fact of political life is that the “many” are always governed by the “few.” See Morgan 1988 for a particularly searching historical account of the “opinions” or “fictions” that can be said to sustain this fact in modern America.

3. For useful summaries of the considerable literature on resource mobilization, see especially Tilly 1978 and Tarrow 1989.

4. For a penetrating analysis of this kind of transformation at a fairly early date in England’s history, see Justice 1994.

5. Excellent examples of this kind of microhistorical examination of particular events abound, but the work of historical anthropologists emphasizing the need for “thick description” is certainly the most sophisticated. For practical examples of historical-anthropological analysis as well as important discussions of theoretical orientation, see especially Isaac 1982 and Burke 1987. For the continuing inspiration of the work of E. P. Thompson and Natalie Davis, in particular, see the article by Suzanne Desan in Hunt 1989. James C. Scott’s work (1990: esp. chap. 6) seems indispensable, however, in that it draws on the historical research on popular collective action in Europe but challenges us to go beyond the narrow definitions of political behavior that are often embedded in that literature. For examples of the distinctive genre of microhistory in Italian studies, see Levi 1988; Muir and Ruggiero 1991; Muir 1993.

6. Aya 1990 argues that in order to “bring the people back in” to the study of revolution, we must try above all to understand the rationality of the multiple, complex, and often difficult political choices that ordinary people have to make in such conflicted and anxious circumstances. To that end, he not only invokes the example and critical methods of cultural anthropologists but also insists on distinguishing in particular revolutionary situations between the intentions, the capabilities, and the opportunities of collective actors. Much of this comports well with what I am arguing for popular politics more generally, except that instead of “intentions” I have spoken of the “claims” of popular political actors. While I agree that ordinary people must be considered intentional actors, I am not so sure that we can with very great certainty infer their intentions from the claims they make on their rulers in the course of political negotiations.

7. This seems to be true not only because established authorities (and contemporary observers) document them with special care but also because political subordinates are often emboldened to express, in such exceptional circumstances, opinions and political claims they might normally keep hidden (see Scott 1990).

8. The assertion of monarchical absolutism and the consolidation of territorial states was characteristically a gradual, long-term process in both eastern and western Europe (e.g., Prussia, Austria, France, and Spain), whereas the confirmation of new revolutionary regimes typically involved both international conflict and multiparty treaty agreements recognizing their independence (e.g., the Swiss Confederation and the Dutch and American republics).

9. I am especially indebted here to the excellent summation and theoretical extension of this literature in Tarrow 1989. See also Tilly 1978, 1986.

10. The generic “prince,” in the sense of a political force accumulating territory, need not be a singular or a dynastic actor. In the case of the republic of Venice, for example, it was a closely knit oligarchy that added territory to its domain during the conquest of the terra firma; typically the newly conquered territories were guaranteed local “privileges” in return for their submission. See Finlay 1980; Guarini 1995.

11. James Scott’s work (1987, 1990) is exemplary in the way that it explores the enormous ingenuity that ordinary people display in “working the system to their minimum disadvantage.” In contrast to my approach here, however, Scott’s descriptions of the relations of domination and (everyday) resistance tend to be neatly singular and linear, focusing on one set of relations at a time. It is critically important to apply a wide-angle lens to the analysis of the variable dimensions of domination and to the plurality of power in early modern Europe.

12. For the most part, this discussion treats the domain of the local ruler as its basic unit of analysis, but it is clearly evident that within even the local domain a variety of institutions, such as guilds, monasteries, brotherhoods, and families, might claim a significant degree of “private” self-determination.

13. On the nature and significance of exclusive or revolutionary claims, see Tilly 1978.

14. Obviously, these broad principles of alignment and opposition do not apply exclusively to early modern composite state formations. Unfortunately, the teleological myopia of most of the literature on European state formation obscures this element of “modern” state formations like the United States or the European Union.

15. The prevalence of the term “ancien régime” to describe Europe between, say, 1660 and 1780 is doubly unfortunate in that (1) it embodies a retrospective anachronism in which the era of the French Revolution stands as the frame of reference through which we view the preceding period; and (2) it obscures the novelty of the political and religious arrangements that emerged after the religious wars, suggesting instead that these were, at bottom, holdovers from the distant past.

2. Revolt and Religious Reformation in the World of Charles V

First of all, the gospel does not cause rebellions and uproars, because it tells of Christ, the promised Messiah, whose words and life teach nothing but love, peace, patience, and unity. And all who believe in this Christ become loving, peaceful, patient, and one in spirit. This is the basis of all the articles of the peasants.…to hear the gospel and to live accordingly.…

Second, it surely follows that the peasants, whose articles demand this gospel as their doctrine and rule of life, cannot be called “disobedient” or “rebellious.” For if God deigns to hear the peasants’ earnest plea that they may be permitted to live according to his word, who will dare deny his will?

You are robbing the government of its power and even of its authority—yea everything it has, for what sustains the government once it has lost its power?

In the midst of what was surely one of the most dramatic popular political challenges of the sixteenth century, the representatives of three large peasant armies assembled at the town of Memmingen and drew up “The Twelve Articles of the Peasantry of Swabia” in late February or early March 1525. The articles not only listed specific grievances and demands that reflected a profound crisis of agrarian society and religious authority but also expressed a set of principles that were at once revolutionary and capable of encompassing the hopes and aspirations of a broad coalition of political subjects throughout southern Germany. Thus, the third article joined an attack on serfdom with an alternative vision of the political and social future: “It has until now been the custom for the lords to own us as their property. This is deplorable, for Christ redeemed and bought us all with his precious blood, the lowliest shepherd as well as the greatest lord, with no exceptions. Thus the Bible proves that we are free and want to be free” (Blickle 1981: 197). In this sense, Martin Luther, whose theological challenge to the established Church had inspired and emboldened the peasant leaders, was surely right in arguing that the peasants’ demands threatened the established political order. The peasants’ protestations to the contrary notwithstanding—“Not that we want to be utterly free and subject to no authority at all,” the third article continued—this most famous of the manifestos associated with the Revolution of 1525 promised to transform Swabian society according to the lofty principles of “godly law.”

At the time the peasant leaders were assembled in Memmingen, they can be said to have enjoyed a brief military advantage over their opponents; for the armies of the imperial Swabian League were temporarily distracted by other, more traditional military challenges. Once they turned their attention to the massive insurrections, not only in Swabia but in Franconia and Thuringia as well, the established rulers and their more practiced and professional armies easily defeated the popular challengers, sometimes even without a fight. By the end of the year, virtually all of the peasant insurrections had been subdued and a massive repression had begun throughout the area. Indeed, never again would this region be rocked by popular insurrection on such a massive scale.

Because of the well-deserved fame of the Revolution of 1525, not to mention the explosion of revolutionary religious enthusiasm at the city of Münster ten years later, it is tempting to identify popular religion with popular rebellion in the early years of the sixteenth century. As it happened, however, popular movements for the reformation of religious belief and practice took a variety of forms short of open rebellion—from the submission of humble petitions to the formation of secret “conventicles.” Moreover, “successful” reformations were as often magisterial as popular in origin. Thus the political dynamics of the English and Scandinavian reformations, where rulers actively aligned themselves with religious reform movements, were strikingly different in the 1530s and beyond. In England, for example, in the absence of massive popular demands for religious change, the king took the initiative to separate the Church from Rome and to introduce modest changes in the ritual life and dogma of the Church of which he now claimed to be the head. The most obvious popular response in 1536 was an abortive rebellion in Lincolnshire and what has come to be known as the Pilgrimage of Grace.

The leaders of these English movements, like the leaders of the German revolution, put together broad but immensely fragile coalitions that could not withstand the counterchallenges of the king and his allies. Also like their German predecessors, they articulated an eclectic set of grievances and published specific demands regarding the regulation of public affairs and social relations in an agrarian society. But in the English case, instead of demanding reform or liturgical innovation, the leaders of a broadly based popular mobilization were emphatically demanding the restoration of the established Roman church and the religious practices associated with it. Meeting at Pontefract in December 1536, for example, they demanded vigorous actions against “the heresies of Luther,” among others, and insisted that “the privlages and rights of the church…be confirmed by acte of parliament, and prestes not suffre by sourde onless he be disgrecid” (Fletcher 1983: 111–112). In response, a publicist for the king asked rhetorically,

Despite their obviously different demands with regard to the reformation of religious practice and belief, then, the rebels in both Germany and England were seen by contemporaries to threaten the foundations of established authority and to promise a fundamental reorientation of the essential relationships between rulers and their subjects.When every man wyll rule, who shall obeye?…No, no, take welthe by the hande, and say farewell welth, where lust is lyked, and lawe refused, where uppe is sette downe, and downe sette uppe: An order, and order muste be hadde, and a waye founde that they rule that beste can, they be ruled, that mooste it becommeth so to be. (Ibid., 112)

Such was the nature of the Reformation era in Europe: though dissenting theologians like Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and Jean Calvin may not have intended it, their direct challenges to the authority of the established Church intersected with and had profound implications for the interactions of subjects and rulers more generally. As Euan Cameron sums up the process in his recent survey,

Consequently, the sixteenth-century Reformation was a unique transition in the history of Western Christendom in the sense that it laid the foundations for divergent paths of closely linked religious and political development that endured throughout the early modern period.Politically active laymen, not (at first) political rulers with axes to grind, but rather ordinary, moderately prosperous householders, took up the reformers’ protests, identified them (perhaps mistakenly) as their own, and pressed them upon their governors. This blending and coalition—of reformers’ protests and laymen’s political ambitions—is the essence of the Reformation. It turned the reformers’ movement into a new form of religious dissent.…[I]t promoted a new pattern of worship and belief, publicly preached and acknowledged, which also formed the basis of new religious institutions for all of society, within the whole community, region, or nation concerned. (1991: 2; emphasis in original)

This chapter focuses on popular political action during the first act of the European Reformation, especially within the composite domain of Charles V of Habsburg. The consummate late medieval dynastic prince, Charles combined a collection of patrimonial lordships in the prosperous commercial centers of the Low Countries with a composite kingship in Iberia, created just half a century earlier by the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon with Isabella of Castile, and the emperorship of the vast German-Roman Empire in central Europe. It was within or on the fringes of Charles’s imperial domain, to which he was elected in 1519, that popular enthusiasm for religious reform was first concentrated in the 1520s; and as I will argue, popular engagement in the essentially political process of religious reformation took a variety of forms in Germany—including, of course, the Revolution of 1525—which precipitated, by midcentury, a political and religious settlement that extinguished Charles’s unambiguous claim to cultural or religious sovereignty over the whole of his empire. To underscore the significance of these political and religious conflicts for the subsequent history of central Europe, this chapter also sets the German Reformation in the larger comparative context of the Scandinavian and English reformations where, by contrast, popular engagement in the reformation process helped to consolidate princely claims to cultural sovereignty. I begin, however, with a brief examination of the first major challenge to Charles’s sovereignty—the Comunero Revolt of 1520–1521 in Castile, at the heart of his Iberian domain—for two principal reasons: on the one hand, the Comunero Revolt did not directly invoke the question of religious authority and thus reminds us that not all sixteenth-century conflict was associated with or inspired by the challenges of Protestant theology; on the other hand, the Comunero Revolt involved all the important political actors within a composite state—local rulers and ordinary political subjects as well as national claimants to power—and thus illustrates clearly the long-term significance of the alternative alignments among them.

| • | • | • |

Communes and Comuneros in Castile

On May 30, 1520, just ten days after Charles I of Castile had left Spain to assume his new role as Charles V in the German-Roman Empire, an unruly collection of artisans, mainly textile workers in the woolen industry, invaded the city hall of Segovia and seized Rodrigo de Tordesillas, one of the city’s official delegates to the recent meeting of the Cortes that had been summoned by the king at Santiago. Incensed by the apparently boundless fiscal demands of their young monarch—demands that seemed to support little more than Charles’s dynastic ambitions in Germany—the crowd brought their defenseless victim, who was condemned for having betrayed local interests, first to the city jail and eventually to the place of public executions where they hanged him. Stephen Haliczer describes the aftermath:

In the next four months, delegates of the city of Segovia joined delegates from no less than eighteen other revolutionary cities in Castile to constitute the Sacred League (Sancta Junta), which claimed power as the sole legitimate government of Castile in place of Charles’s regency government, which had quickly collapsed in the face of this powerful wave of urban insurrection.Tordesilla’s murder was the signal for a wholesale attack on the representatives of royal government in the city of Segovia. The corregidor (royal official of the town), his lieutenants, and police officials were stripped of their offices and forced to flee. New officials were appointed by a revolutionary committee composed of members of the city council, delegates from the cathedral chapter, and parish representatives. The Comunero revolution had begun. (1981: 3)

In many respects, the revolution of the Sacred League, also known as the Comunero Revolt, represented a classic form of local resistance to an aggressive dynast (see Blockmans 1988). The Sacred League was a coalition of many, though not all, of the leading cities of the Kingdom of Castile, whose sovereignty Charles had seized from his own apparently insane mother in 1516. Collectively, the members of the league, whose efforts were welcomed by the deposed and psychologically unstable Queen Juana, sought to abolish the alcabala (a general tax on commerce), to reduce the power of the king, and to transform the Cortes, in which they were represented, into the primary institution of the state (cf. Bonney 1991; Lynch 1991). The political demands of the Comuneros may thus be considered fundamentally revolutionary in the sense that they were exclusive of the claims to political sovereignty that Charles was making as king; to accept the rebels’ claims, indeed, would be to transform fundamentally the structure of political authority in Castile.

As the events in Segovia suggest, however, the Comuneros’ opposition to the royal government involved as well a political realignment within the local community as officials appointed by and oriented to the royal administration were replaced by others who were more responsive to local demands and who were selected by, among others, the representatives of popular parish assemblies. And once they joined the Sacred League, the leaders of the rebellious communes of Castile deepened their political orientation toward ordinary political actors within the urban community by building the league’s defenses on the basis of urban militias mobilized and recruited locally. There is certainly more than a little historical irony in the fact that the Comunero Revolution adopted the defensive form of a sacred league because less than fifty years earlier, in 1476, Queen Isabella had encouraged the chartered cities in her Castilian domain to act as a sacred league—the Sancta Hermandad—and to raise urban militias to maintain public order and support her in her efforts to tame the powerful Castilian nobility. Though the league of cities had been disbanded in 1498, when the Crown once again shifted its dynastic policy toward dependence on the rural nobility, the lessons of this earlier political process had clearly not been lost on the municipalities involved. To deploy the civic militia in opposition to the new king, however, was to create a new kind of internal political dynamic that also entailed the creation of independent municipal councils, or “communes” (hence the name “Comunero”). For the duration of the revolt, at least, the local rulers of the rebellious cities were to be fundamentally dependent on the approval and support of their subjects (see fig. 2a).

In the late summer of 1520, the political situation in Castile became even more volatile and threatening to the established political order when political disturbances in the countryside began to threaten noble landlords as well as the king. In the village of Dueñas, not far from the capital of Valladolid, for example, rebellious peasants, spurred on by a group of radical monks, rejected the lordship of the local count of Buendía and replaced the count’s officials with others chosen by a popular assembly. The rebels then proceeded to encourage rebellion in other parts of the count’s local domain, and they seized nearby fortresses belonging to the count (Haliczer 1981: 185). In October, there were also a number of antiseigneurial revolts in Tierra de Campos, where eventually some twenty-seven localities sent representatives to a rebel league that met at Palencia. In principle, the peasant revolts might have offered the urban Comuneros potentially important allies in their fight against the king and the powerful nobility with which he was allied, but in the end the Comuneros’ failure to take advantage or ally themselves with the rising tide of rural discontent exposed the limits of this sort of urban resistance to aggressive dynasts. The fact is that the political bargains by which dynastic princes typically constructed their composite states created local privileges that distinguished one piece of the composite from another. Indeed, the extent to which municipal charters privileged urban communes over their rural hinterlands militated against urban-rural alliances vis-à-vis a common enemy like an aggressive dynast or his noble allies; and in this case, the extent to which the Comuneros’ militias indiscriminately exploited defenseless country folk in the course of their military campaigns made such alliances extremely unlikely.

Thus the rebellious cities’ political isolation in an essentially rural environment underscored the fragility of their revolutionary coalition. At first, the urban militias were able to hold their own against the royal government’s feeble counteroffensive, but inasmuch as the rural rebellions served as a serious warning to the nobility of the obvious dangers of a general disintegration of royal authority to preserve peace and guarantee their privileges in the countryside, the king’s regent was soon to be bailed out by the combined forces of the nobility’s private armies. The first serious blow to the Comuneros came in December 1520 when a royalist army sacked their lightly defended capital at the town of Tordesillas and captured thirteen league delegates. The league was quickly reconstituted at Valladolid, though it was pared down to eleven cities, and briefly rallied by capturing all of Tierra de Campos. But in the spring of 1521, the military struggle finally turned in favor of the king’s forces, and in a decisive battle at Villalar, the viceroy’s infantry defeated the Comuneros’ exhausted soldiers. On April 24, 1521, the three principal Comunero military leaders were condemned to death, and although the city of Toledo held out until February 1522, the revolution of the Sacred League had come to an end.

Though the Comuneros were thus defeated militarily, their resistance to the aggressive dynasticism of Charles of Habsburg was not without result. Indeed, Haliczer describes the postrevolutionary political situation in Castile as follows: “Charles did not return to a cowed and subdued Castile ready for unquestioning obedience; instead, it was a subdued king who came back [from Germany] to a restive and hostile kingdom in 1522 to face the task of rebuilding support for the monarchy” (1981: 207). From this perspective it is not surprising that the cities of Castile gained some important concessions from the king following their defeat: a system of tax collection more favorable to the cities; a reorganization of the central government along lines favored by the cities; and a Cortes decidedly more receptive to the special grievances of the cities. Even the government’s repression may be considered light because many of those who had been excluded from a general pardon in 1522 were eventually pardoned; in the end, only twenty-three persons were executed for their resistance to the monarchy.

Still, in the long run, the most important political development from the point of view of the ordinary citizens of the Castilian towns is that the Crown began channeling its considerable patronage to municipal representatives in the Cortes. In short, a political alignment of ordinary people with their local rulers—which underwrote a local consolidation of power vis-à-vis the king for the duration of the revolt (see fig. 2a)—was replaced by an alignment, lubricated by royal patronage, between local magistrates and the king—which consolidated the power of the elites vis-à-vis their local subjects (see fig. 2b). For the king, the not inconsiderable result was that the municipal representatives to the Cortes would henceforth be more likely to grant him his fiscal demands, but this kind of favorable treatment also helped to create a privileged set of urban oligarchs who were clearly more alienated from their political subjects than their predecessors had been during their defense of the local community in the face of monarchical consolidation. Indeed, effective municipal resistance to monarchical consolidation inevitably depended on coalitions of a variety of sorts: between municipal rulers and their subject populations; among cities with often disparate economic and political interests; or between rebels on opposite sides of the legal, social, cultural, and sometimes even physical barriers that differentiated cities from their rural hinterlands. In the aftermath of the Comunero Revolt, then, it can be said that to the extent that royal policies privileged cities over their hinterlands and oligarchs over their urban subjects, they helped to ensure that an urban revolt of this magnitude would not be repeated in Castile.

| • | • | • |