Chapter Two

Legislative Imagery Under Napoleon

France emerged from a decade of revolutionary strife hungering for order. Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès's support of Napoleon's coup d'état is a telling indication of this political climate. The theorist who in a more innocent phase of the Revolution had been a leading advocate of the nation's constituent power and of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was willing to take drastic measures to end the lawlessness of directorial France. In the aftermath of the coup Sieyès compiled notes for a constitution, in which he wrote that "authority must come from above and confidence from below" and that a constitution should be "short and obscure."[1]

Following the forcible dispersion of the Council of Five Hundred, Sieyès collaborated with Napoleon—who now bore the title of first consul—in drafting a new constitution. To his dismay and that of his collaborators, Napoleon, whom they had envisioned as a mere instrument to effect constitutional change, was unwilling to share the power seized by force. With this uncompromising attitude and the backing of his loyal army Napoleon could not be resisted. He altered Sieyès's complex project, molding the Constitution of Year VIII (December 13, 1799) to concentrate power in his own hands.

The dictator was at once a child of the Revolution and a grandson of the Old Regime. Though he continued the Revolution's war against the European monarchies and realized the dream of a rationally ordered and centralized France regulated by a single code of civil law, Napoleon returned the nation to Catholicism and had himself crowned as emperor. In Napoleonic France, moreover, the

revolutionary cult of the law was transformed. The ambivalence toward the revolutionary heritage that would characterize Napoleonic France was expressed succinctly when, following the coup d'état of 18-19 Brumaire, the three consuls of the provisional government, Napoleon, Sieyès, and Pierre-Roger Ducos, presented the new authoritarian Constitution of Year VIII to the nation for approval. "Citizens," the consuls declared, "the Revolution is fixed in the principles by which it began: it is finished."[2]

The revolutionary legislators were too busy making and destroying constitutions to fulfill the intention, stated in the Constitution of 1791, that the nation be provided with a "code of civil laws, common to all the kingdom." Under Napoleon, the focus of legislative activity shifted from the public to the private domain, that is, from constitutional to civil law.[3] And a vast campaign of legal codification was undertaken: the famous Code Napoléon (Civil Code) of 1804 was followed by codes of civil procedure (1806), commerce (1807), and criminal procedure (1808) and by a penal code (1810). Although some great jurists of the Old Regime had attempted to unify the nation's welter of customary law (followed in the northern half of France), written Roman law (followed in the Midi), and royal ordinances,[4] the task required the centralized administrative vigor of Napoleonic France.

In 1812 Jacques-Louis David depicted Napoleon as a tireless legislator in a portrait commissioned by Alexander Douglas, a Scottish nobleman, art collector, and admirer of Bonaparte (Plate 4). It is almost 4:15 A.M. , and the candle burns low. Napoleon, the artist explained, had spent the night absorbed in his work on the code; having ceased his labor, he stands alert, ready to buckle on his sword and review his troops.[5] Such fortitude and industry, made all the more impressive by David's insistence on the corporeality of the man, are echoed by the fiercely erect feline leg of the work table and by the Napoleonic bees decorating the massive regal chair. On the chair and table a sword and the rolled code symbolize Napoleon's accomplishments as warrior and lawmaker, which Louis de Fontanes, the president of the imperial Legislative Body, was fond of invoking.[6] Appropriately, a volume of Plutarch lies near his feet to recall for David's contemporaries the legendary legislative prowess of a Lycurgus or a Numa.

Napoleon presided over more than half of the 102 sessions in which the work of the Civil Code commission was discussed before the Council of State. Notwithstanding his lack of legal sophistication, he contributed to the code's emphasis on paternal authority and the protection of property. Although he sup-

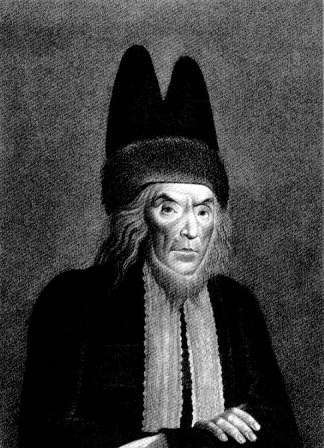

Fig. 17.

C. Gautherot, J.-E.-M. Portalis , 1806.

Musée National du Château de Versailles.

posedly complimented David for truthfully revealing how "at night I work for my subjects' happiness,"[7] he was hardly the author of the durable and internationally influential body of law that bears his name. Such is the persuasive power of David's stately arrangement of scrupulously rendered symbolic details that the genesis of the Code Napoléon is veiled behind the charismatic person of the great leader.

The Code Napoléon was drafted by a commission of jurists appointed in 1800 and headed by Jean-Etienne-Marie Portalis (1746-1807).[8] A lawyer in the parlement of Aix under the Old Regime, Portalis had served as president of the Council of Ancients and was exiled as a result of the anti-royalist coup of 18 Fructidor (September 4, 1797). Appointed minister of religion in 1804, he had been deeply involved in directing French religious affairs since the signing of the Concordat with the Vatican in 1801. It was appropriate that this pious jurist was both minister of religion and chief drafter of the Civil Code, for Napoleonic France inherited from the revolutionary legislators a quasi-religious attitude toward the law. Although Napoleon's legal expert was nearly as blind as Justice (he squints weakly in his official regalia in Claude Gautherot's portrait, Fig. 17), he had a prodigious memory.[9]

Portalis and his associates wanted a code that, like Roman law, would be a universally valid expression of "written reason." Surely the code commission was flattered when the tribune Louis-François-Alexandre Goupil de Préfelne told the Legislative Body that the code "will merit the title written reason of our century ."[10] But the middle-aged jurists of the commission were pragmatists who, moreover, perceived reason in the traditions they knew. Accordingly, they avoided innovation and attempted to strike a compromise between Roman law, custom, royal ordinances, and revolutionary legislation.[11]

Although Napoleon regarded the code as one of his principal achievements, he was disturbed by its dryness, which confirmed his belief that the "vice of our modern legislators is an inability to speak to the imagination."[12] Convinced that the stability of his regime depended on its power to "dazzle and astonish,"[13] Napoleon wanted his code to inspire awe. Official demonstrations of amazement and gratitude were in order.

With the promulgation of the Code Napoléon (under the title Civil Code of the French People) on March 21, 1804, France resounded with hyperbolic praise of the first consul's legislative prowess. In gratitude for the Civil Code, the Legislative Body decreed that a bust of Bonaparte be placed in the midst of their assembly hall in the Palais-Bourbon. The project was amplified to a life-sized sculpture, The First Consul Offering the Civil Code to the French People , with the inscription: TO BONAPARTE FROM THE LEGISLATIVE BODY . On the advice of Vivant Denon, Napoleon's chief artistic director, the commission was given to Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763-1810).[14] The original design that called for civilian dress was modified so that Napoleon would be draped like a caesar. As an engraving of Chaudet's lost statue indicates, this work gave the "restorer of laws" an appropriately august bearing (Fig. 18).[15]

No less grandiose in evoking the legislative stature of the emperor was a relief ensemble by Jean-Guillaume Moitte (1746-1810) on the west wall of the Cour Carré of the Louvre, History Inscribing upon Her Tablet the Names of Napoleon the Great and the Legislators Moses, Numa, and Lycurgus (Fig. 19).[16] The elegantly mannered poses and richly linear drapery of Moitte's group were intended to be in stylistic accord with the existing sixteenth-century reliefs by Jean Goujon.[17] History, flanked by busts of Herodotus and Thucydides, inscribes the name of France's great legislator in the presence of four representatives of the sacred mysteries of law. Numa—the legendary second king of Rome, whose laws were

Fig. 18.

J.-N. Laugier after Bourdon, engraving of A.-D.

Chaudet, The First Consul Offering the Civil

Code to the French People (1805), c. 1820.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 19.

J.-G. Moitte, History Inscribing upon Her Tablet the Names of Napoleon

the Great and the Legislators Moses , Numa, and Lycurgus, c. 1805-7.

Cour Carré, Louvre, Paris.

Fig. 20.

J.-S. Barthélemy, The Passage of the Isthmus of Suez and His Majesty Visiting the Wells of Moses ,

Salon of 1808. Musée National du Château de Versailles.

inspired by the nymph Egeria—holds attributes of priesthood and prophecy, the wand of augury and a vestal flame;[18] Moses points to the celestial source of his inspiration.[19] The pose of this Moses derives from conventional representations of Saint John the Baptist, suggesting, further, that the Hebrew legislator is a prophet of Napoleonic legal genius. The Egyptian god Isis and the mythic demigod Manco-Capac, who brought civilization to the Incas, are peculiar iconographic elements, not included in a preserved bronze-cast sketch. These figures were apparently added as arcane references to the divine nature of legislative genius.[20] Such imagery fit the Napoleonic practice of referring to lawyers by the Roman title "priests of the laws."[21]

A painting commissioned by Vivant Denon in 1806 from Moitte's friend the Old Regime history painter Jean-Simon Barthélemy (1743-1811) also implied that Napoleon was following in the tracks of Moses.[22] The flattering biblical resonance of The Passage of the Isthmus of Suez and His Majesty Visiting the Wells of Moses (Fig. 20) was subtly accented in the official guide to the Salon of 1808, which noted that before visiting the fountains of Moses, Napoleon had crossed the Red Sea at a ford accessible only at low tide.[23] Although Salon critics were not enthusiastic about the work, the emperor personally offered his compliments to the painter, who spoiled the occasion with his speechlessness.[24]

The aggrandizement of Napoleon's personal stature as lawgiver in Chaudet's statue and Moitte's relief group represented a departure from the revolutionary tradition of honoring the law. Even though the legislature exercised a dictatorship until the fall of Robespierre, the revolutionary notion that law was the expression of the general will theoretically divested legislators of individual political authority; they were but vehicles through which the general will of the nation was realized.[25] Although Napoleon maintained this revolutionary doctrine his regime associated the general will not with the legislature but with the charismatic dictator.

Between the Tennis Court Oath and the Directory, revolutionary politics had been dominated by the legislature. But Napoleon—who seized power through an act of anti-parliamentary violence—almost obliterated the power and autonomy of the legislature and reinstated pre-revolutionary executive power with a vengeance. In 1804 he bluntly characterized his position: "I am the constituent power."[26] "Legislation incarnate" was an epithet supposedly applied to him by Second Consul Cambacérès.[27] Such uncompromising personalization of the law

recalls the Old Regime concept of the monarch as supreme legislator. "This was the first time since the Revolution," Madame de Staël noted, "that you heard a proper name in everyone's mouth." Previously, "one said the Constituent Assembly had done such and such, the people, the Convention; now one only spoke of the man fated to take the place of all others and render the human species anonymous by monopolizing celebrity."[28]

The Napoleonic practice of inscribing Bonaparte's name in the constitution reflected this personalization of the law. Whereas the revolutionary constitutions had upheld Rousseau's insistence that law remain unsullied by particulars, the Constitution of Year VIII cited the three consuls by name, and the imperial Constitution of Year XII (May 18, 1804) specified the positions of Napoleon's heirs in the line of succession to the throne.

On September 3, 1807, the new Civil Code was renamed Code Napoléon.[29] This change of title, which consolidated the fiction of Napoleon's authorship, occurred within days of the huge state funeral (August 29) of Portalis, the venerable jurist who had headed the Civil Code commission. The tribune Georges-Antoine Chabot (known as Chabot de l'Allier) announced the new title to the Legislative Body, justifying the official use of what had long been used "spontaneously" by pointing out how the emperor, with his "triumphant hands," had established France's civil laws:

He was constantly seen participating in the discussion [of the code] . . . directing it with profound ideas and with forceful reasoning. He consistently displayed knowledge that astonished the most consummate jurists and established all [of the code's] fundamental principles through the comprehensive workings of a creative genius to which nothing seems foreign.

In a contention alien to the depersonalized notion of the law embraced by the legislators of the Revolution, l'Allier insisted that Napoleon's greatness would guarantee the durability of the code: "A great name, that is the best safeguard of the laws, and the surest means to convey their authority."[30]

In 1802, when the nation was voting to make Napoleon consul for life, an enthusiastic admirer denounced, in verse, the "timid laws" that would limit the duration of Bonaparte's rule.[31] "A constitution must not interfere with the process of government or be written in a way that would force the government to violate

it," the first consul said before the Council of State in Year X (1801-1802). "Every day brings the necessity to violate constitutional laws; it is the only way, otherwise progress would be impossible."[32] Napoleon's willingness to sacrifice constitutional integrity to political expediency was consistent with his contempt for representative institutions.

Even under the Directory, Napoleon had nursed ominous plans for the nation's legislators. In 1797 he told his future foreign minister Talleyrand that the ideal legislature would be "without rank in the Republic, impassive, without eyes and without ears," that it would "no longer swamp us with a thousand circumstantial laws that annul themselves by their absurdity and constitute us a nation with three hundred volumes-in-folio of laws."[33]

Napoleon first unleashed his hostility toward the revolutionary legislative tradition in his authoritarian Constitution of Year VIII, which divided the process of legislation—introduction, deliberation, and voting—among three bodies: the Council of State, the Tribunate, and the Legislative Body. The Senate chose members for each of the three and served as a tribunal for constitutional questions. Legislation was initiated by the "government"—that is, the first consul with the advice of his administrative court, the Council of State. The Tribunate—purged in 1802 after resisting the first project of the Civil Code commission—discussed the proposed laws but could not vote on them. The Legislative Body voted on measures presented to it by the Tribunate but was barred from deliberation, under pain of discipline. The mute and generally docile Legislative Body, composed largely of obscure but now affluent former revolutionaries, was thus a mere shadow of the great revolutionary legislative assemblies.

The dictatorship initiated by the Constitution of Year VIII was strengthened by amendments that make up two additional constitutions. According to the Constitution of Year X (measures enacted August 2 and 4, 1802) Napoleon, named consul for life, was empowered to legislate and to interpret and define the constitution through edicts issued through the Senate (senatus consulta).[34] Rich rewards of land and residences guaranteed the Senate's allegiance. The Legislative Body would henceforth be convoked and dissolved at the will of the government. With the Constitution of Year XII (May 8, 1804) Napoleon was elevated to the imperial throne.

The difficult task of bringing luster to the captive legislature was handled with aplomb by Louis de Fontanes,[35] who during his remarkable career rode the changing

winds of French politics with an agility that earned him a large entry in the satirical Dictionnaire des girouettes (Dictionary of weathercocks; 1815).[36] A moderate during the early years of the Revolution, Fontanes, like Portalis, was forced to emigrate by the anti-royalist coup of 18 Fructidor (September 4, 1797). Following a year of exile in England, Fontanes returned to France, where in 1804 he became president of the Legislative Body. While he quietly insisted on the autonomy and dignity of this assembly, his official speeches were such masterpieces of obsequiousness that a satirical pamphlet published under the Restoration ridiculed him by simply quoting from his Napoleonic addresses.[37] "The man before whom the universe is silent is also the man in whom the universe has confidence," Fontanes declared of Napoleon on March 5, 1806. If the universe was not silent before the emperor, the Legislative Body generally was. "He is both the terror and the hope of peoples. . .. As soon as the wise saw him . . . they recognized in him all the signs of domination."[38] This was appropriate praise of a ruler who had reduced the legislature to an assembly of mutes.

Even as the Legislative Body was wholly subordinate to him, Napoleon was concerned to clothe this living symbol of his supremacy as lawgiver in appropriate dignity.[39] To this end some modifications of the building in which the Legislative Body assembled were carried out under official command. Bernard Poyet (1742-1824) designed a majestic flight of steps and an imperial portico for the Seine facade of the Palais-Bourbon (Fig. 21), which served as Napoleon's "Temple of Laws."[40] The emperor, however, was displeased with the result.[41] Jean-Baptiste Regnault's fiercely revolutionary painting Liberty or Death (Salon of 1795), which had been on view since 1799 in the assembly hall of the Council of Five Hundred in the Palais-Bourbon, was removed. It was replaced by The Signature of the Preliminaries of Leoben , by Guillaume Guillon (called Lethière), representing an early manifestation of Napoleon's dictatorial resolve.[42] In addition to Chaudet's First Consul Presenting the Civil Code to the French People , portraits of Napoleon and Josephine in imperial costume were purchased from Ingres and Lethière.[43]

Although the cold glamour of Ingres's Napoleon on His Imperial Throne has proved irresistible to late twentieth-century eyes familiar with Pop Art and Photo-Realism, the artist was deeply pained to learn that this strangely hieratic and airless portrait (Fig. 22) had failed at the Salon of 1806, where the likeness was faulted as well as the resemblance to the fifteenth-century art of Jan van Eyck. Modern commentators, noting among the sources for the portrait the God the

Fig. 21.

B. Poyet, Seine facade of Palais-Bourbon , 1806-8. Paris.

Fig. 22.

J.-A.-D. Ingres, Napoleon on His Imperial

Throne , 1806. Musée de l'Armée, Paris.

Father panel from Jan van Eyck's Ghent altarpiece, plundered for display in Paris, have delighted in Ingres's forceful archaism, in which compositional rigidity is startlingly combined with minute detail. The stylistic archaism reinforces references to Charlemagne—the sword and hand of justice supposedly borne by the medieval emperor and restored, or perhaps manufactured anew, for Napoleon's coronation.[44] Such references, common in Napoleonic propaganda before the 1806 Salon, could have been additional irritants to contemporary critics.[45]

Although Ingres's imperial portrait, purchased by the Legislative Body prior to the 1806 Salon, was apparently not an official commission, it was an appropriate one. It offers an unblushing expression of the emperor's domination over the Legislative Body.[46] At the time of its purchase, it was intended for the chambers of President Fontanes, but it was relegated (along with Lethière's portrait of the empress) to the office of the quaestors, who, as treasurers of the Legislative Body, had purchased the works.

That Ingres's portrait was sent to this undistinguished location is not surprising given the critics' response to it. Before the Salon, however, this portrait would have seemed a fitting ornament for the chambers of Fontanes. Ingres's presentation of the emperor as a new Charlemagne, timelessly enthroned with the props Fontanes had recommended for the imperial coronation,[47] struck a common chord with the pious nostalgia for the Middle Ages professed by the president of the Legislative Body. Shortly after the imperial coronation, Fontanes joyfully observed:

Ten centuries have passed since the epoch when France saw a similar spectacle. A monarchy of fourteen hundred years that seemed buried beneath so many ruins has suddenly reappeared with its ancient splendors, and almost all the diadems that the family of the Martels [i.e., the family of Charlemagne] had lost are again reunited on the same head.

This singular event, explained Fontanes, had been made possible by the restoration of Catholicism in France: only religion "explains and consecrates the greatest mystery, that of power and obedience."[48]

The construction by Chaudet, Moitte, and Ingres of a Napoleon whose legislative authority was both timeless and superhuman was consonant with the emperor's decision to convoke the Grand Sanhedrin—the ancient Jewish govern-

ing body that had not met since the destruction of the Second Temple by Titus in A.D. 70. This meeting, February 9-March 13, 1807, was a legal pageant intended to guarantee that the religious and cultural traditions of Napoleon's Jewish subjects would not interfere with their civic duty.[49] Moreover, it publicized Napoleon's Mosaic role of legislating to the Jews.[50]

The compatibility between Jewish custom and French law had been discussed by the Assembly of Jewish Notables, convoked by Napoleon on March 7, 1806. This assembly argued that only the Grand Sanhedrin could rule on matters of Jewish polity. His imagination stirred, the emperor wrote to Minister of the Interior Jean-Baptiste de Nompère de Champagny on August 23, 1806, ordering the convocation of the Grand Sanhedrin. Its deliberations, the emperor wrote, would have "the force of ecclesiastical and religious law" and would "stand as a second legislation of the Jews." The authority of the Sanhedrin's acts would ensure their placement "next to the Talmud as articles of faith and principles of religious legislation."[51] To solemnize the meeting, it was held in the former Chapel of Saint Jean, adjoining the Hôtel de Ville (site of the Assembly of Jewish Notables), which was fitted with a temporary decor. David Sintzheim, chief rabbi of Strasbourg, presided over the proceedings. A portrait by Michel-François Demane-Demartrais shows the bicorned hat that Sintzheim was required to wear in his official capacity (Fig. 23). This fanciful headdress, reminiscent of the ancient Levitical miter and the horns of Moses, was not part of contemporary rabbinical regalia. It was apparently designed to reinforce the spirit of pseudo-religious solemnity in which the Sanhedrin's deliberations were clothed.[52]

A commemorative medal by Duprès (pseudonym for Nicolas-Guy-Antoine Brenet, 1770-1846), after a design by Vivant Denon (Fig. 24), baldly represented Napoleon superseding Moses.[53] Here, the emperor presents the roundheaded tablets of the law to Moses, who kneels in supplication. The law, Sintzheim declared in his closing discourse,

returned to its original purity, is going to regain its ancient splendor; and the miraculous bush of our divine legislator is going to burn with a new flame without ever being consumed. . .. And you, Napoleon, . . . you the idol of France and Italy, you the terror of the haughty, the consoler of the human race . . . the elect of the Lord, Israel raises a temple to you in its heart.[54]

Such unblushing flattery was de rigueur at the proceedings.

Fig. 23.

M.-F. Demane-Demartrais, M. David Sintzheim ,

c. 1807. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The official line that the meeting of the Grand Sanhedrin was an act of imperial clemency was as fictive as the notion that the Code Napoleon was born of Bonaparte's legislative genius. The Grand Sanhedrin was an instrument of coercion rather than liberation, and the proceedings were followed by the promulgation of the "décret infame," March 17, 1808, which introduced a series of brutal anti-usury reforms at the expense of the Jews of eastern France.[55]

Another Napoleonic project, the Imperial Catechism published in 1806,[56] ostensibly introduced uniformity into Catholic worship; actually, it taught obedience to the state in the guise of religious instruction. The work was largely copied from the Catechism of the Diocese of Meaux (1687), by the great seventeenth-century

Fig. 24.

N.-G.-A. Brenet after V. Denon,

medal commemorating the Grand Sanhedrin,

c. 1807. Musée de la Monnaie, Paris.

defender of Catholic orthodoxy and divine right absolutism, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet. Napoleon, however, insisted on drafting one section of the text, whose importance was indicated by an asterisk. The lesson on the Fourth Commandment, "Honor thy father and mother," thus explained that love, respect, and obedience were due Napoleon "because God, who creates empires and distributes them according to his will, in lavishing gifts on our emperor . . . has established him as our sovereign, has rendered him minister of his might and his image on Earth. To honor and serve our emperor is thus to honor and serve God Himself."[57]

Such politicizing of the catechism went far beyond Bossuet's interpretation of this commandment as prohibiting disobedience toward pastors, kings, and magistrates.[58] Many political catechisms, teaching republican dogma in a liturgical format, were published during the Revolution.[59] In such publications could be found, for example, "The Ten Commandments of the French Republic," which directed the young to pursue all tyrants (even if they were "further than Hindustan"), to be willing to shed their blood in the defense of law and virtue, and to honor August 10—the date of the monarchy's downfall.[60] Bonaparte's reintegration of this genre

of secular indoctrination into a Catholic context was typical of his synthesis of Old Regime and revolutionary tradition.

Beyond the element of personal aggrandizement (for which Napoleon had an insatiable appetite), references to divine legislation in imperial propaganda suggest that the emperor subscribed to the notion—articulated in Rousseau's chapter on the legislator in The Social Contract —that laws, to be durable, needed a divine pedigree. This attachment to the divine basis of law also reflects Napoleon's conviction that religion was integral to the social order, a conviction affirmed in the Concordat, the treaty with Pope Pius VII signed in 1801 and proclaimed the following year, which recognized Catholicism as the religion of the majority of the French people in return for the Vatican's official recognition of the French republic.

With Catholicism officially reinstated, free rein could be given to the piety that during the Revolution had inflamed the rebels of the Vendée region in the west of France and had consoled the aristocracy in exile. The resurgent vigor of post-revolutionary Catholicism was encouraged by the irresistible lyricism of Chateaubriand's Génie du christianisme (The genius of Christianity; subtitled, The beauties of the Christian religion), released four days before the Concordat was proclaimed in what was later characterized by Sainte-Beuve as a "coup de théâtre et d'autel."[61] This book was the fruit of Chateaubriand's exile in England, shared with Fontanes, who would serve as the president of Napoleon's Legislative Body.

Between the winter of 1797 and the summer of 1798, Chateaubriand tearfully rediscovered Christianity under the influence of his mother's death and the opinions of Fontanes. This change of heart was aesthetic as well as religious: Chateaubriand realized the unparalleled fecundity of Christianity, which had inspired magnificent literature, virtuous institutions, and the tender—and distinctly modern—emotion of melancholy. With such timely thoughts, the Génie du christianisme was marvelously attuned to the sense of loss and the need for submission to authority that were felt so acutely in post-revolutionary France. In the Bible, Chateaubriand found poetry unsurpassed in primitive vigor and moral purity—decisively superior to Homer.

Although the narratives of the Old Testament were a fundamental part of Christian tradition, Chateaubriand's focus on the literary merits of Hebrew Scripture had an exotic appeal in France at the turn of the nineteenth century, when most readers' knowledge of Moses and the Hebrews was limited to the

abridged accounts of histoire sainte provided, with commentary, in the Catholic catechism and in popular religious digests.[62] And even though the Catholic hierarchy had traditionally viewed the laity's unguided reading of the Bible with suspicion, Bossuet, Abbé Claude Fleury, and the English bishop Robert Lowth had defended the literary excellence of Scripture in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Old Testament had inspired Racine's Athalie and Esther , and lesser figures, such as Jacques-Charles-Louis de Malfilâtre and Jean-Baptiste Rousseau, had translated and paraphrased the Psalms.[63] Chateaubriand's revival of this pious Old Regime tradition appealed to readers at once nostalgic for pre-revolutionary faith and fascinated by primitive literature.[64]

To reestablish Christian monarchic society on the ruins of the Old Regime and the Revolution, Chateaubriand located its foundation in the primeval authority of Moses, the prophets, and the patriarchs. This political orientation also informs his praise of Mosaic law. Chateaubriand offered poets the subject of Moses descending from Mount Sinai, his brow "adorned with two rays of fire, his face resplendent with the glories of the Lord." And Chateaubriand marveled at the miraculous durability of the commandments entrusted to Moses: "Laws of God, how little you resemble those of men!"[65] France's Catholic tradition offered an antidote to the legislative failures of the previous decade.[66] Fontanes, whose review praising the Génie du christianisme was published in the Mercure de France and reprinted in the official Moniteur , condemned the revolutionaries who "boasted of annihilating by their laws the religious beliefs that nature and habit have so profoundly engraved in the heart."[67]

Chateaubriand's counter-revolutionary perspective on Moses and the Ten Commandments was forcefully articulated in Louis de Bonald's Législation primitive (1802). On returning from exile, Bonald socialized with Chateaubriand, Fontanes, and Joubert in the reactionary Consulate salons of Napoleon's brother Lucien and sister Elisa Bacciocchi and of Chateaubriand's lover, Pauline de Beaumont. In the Mercure de France Chateaubriand was pleased to point out that the work of this "new legislator" confirmed "the literary and religious principles we have enunciated in the Génie du christianisme. "[68] Written during deliberations on the Code Napoléon, Bonald's dense treatise, like his earlier Théorie du pouvoir , denounced the heresies of the revolutionary legislative heritage.

Bonald argued that the proposed Civil Code, while necessary, must be understood as secondary to the natural, moral, and divine law that had served as the

foundation of French legislation before the Revolution. Bonald identified this fundamental law with the Ten Commandments, which can be found "on the first page of every civil and criminal code of Christian peoples, just as it forms the first instruction of all men."[69] Following the example of Bossuet, whose name is reverently invoked in Législation primitive , Bonald traced all authority—political as well as religious—to Scripture. He maintained that the law revealed to Moses—"this primitive and general law, this natural, perfect, divine law"—was the only true constitution. Before it, the laws of the Revolution crumbled like those of ancient societies ignorant of the teachings of Moses and Christ and deceived by their leaders into believing that their false and absurd laws were inspired by the gods. But "a reasonable people wants to see, shining on the brow of the legislator who descends from the holy mountain with the tablets of the law, the mysterious authority that guarantees his communion with divinity."[70]

Although Bonald posed as a new Bossuet, denouncing the heresies of modern France, his preoccupation with fundamental principles of law reveals his debt to revolutionary thought.[71] He criticized the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen as an incomplete imitation of the Ten Commandments. The legislators of the Revolution had foolishly erred, he argued, in not using the Ten Commandments themselves as their principle of law.

Napoleon shared Bonald's conviction that society takes precedence over the individual and that France needed, above all, obedience and uniformity. But for Napoleon religion was only a means to secure his authority. Bonald, Chateaubriand, and Fontanes would have to wait until the Bourbon Restoration for the fulfillment of the counter-revolutionary aspirations nursed under the Consulate and Empire.

Less than a decade after the divinity of Napoleonic authority was inscribed in the Imperial Catechism , the empire was crushed by its monarchic enemies. A French caricature from the spring of 1814 shows Napoleon marching into exile with a bundle of imperial ordinances hanging from a broken scepter and a copy of the great code under his arm (Fig. 25).[72]

When Napoleon returned from exile one year later for the final brief adventure that ended at Waterloo, he was bereft of the authority represented by Chaudet and Ingres in the effigies purchased by the Legislative Body. The restored emperor convinced his liberal opponent Benjamin Constant to draft an amendment to the imperial constitutions to introduce a measure of liberty he was no longer in a

Fig. 25.

Arrival of Napoleon on the Island of Elba , 1814. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 26.

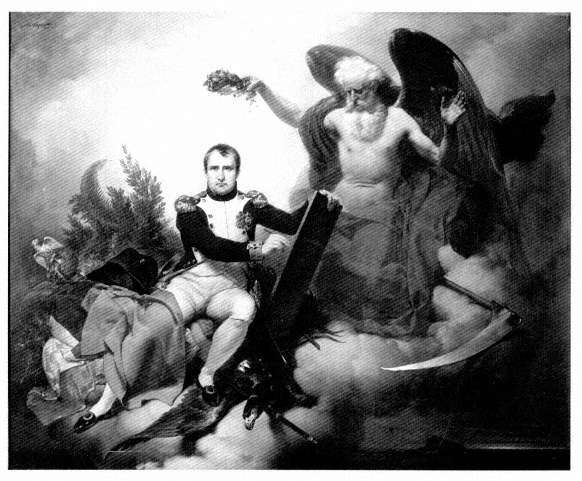

J.-B. Mauzaisse, Allegory of Napoleon Writing the Code ,

Salon of 1833. Musée National du Château de Malmaison.

position to deny. The Additional Act of April 22, 1815, called the Benjamine after its author, modified the balance of governmental power at the expense of the executive. As in the constitutional charter recently granted by the restored Louis XVIII, legislative power was to be shared with a bicameral legislature of peers and deputies. The preamble states that Napoleon had postponed establishing liberal institutions solely to maximize the extent and stability of a great European federation: "Our goal is henceforth only the growth of French prosperity and the solidification of public liberty."[73]

Although this hasty constitutional reform was no more durable than the regime of One Hundred Days, the myth of Napoleon's legislative genius survived. In a painting exhibited in the Salon of 1833 by Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse (1784-1844), Napoleon sits on a cloud far above the somber island of Saint Helena, to which he was exiled after Waterloo (Fig. 26). A conflation of Zeus and Saint John the Evangelist in his crisply detailed uniform, he inscribes his code on a tablet while a reverent figure of Time crowns him.[74] Such hyperbole is characteristic of the cult of Napoleon that flourished during the July Monarchy, when the nation waxed nostalgic over the lost glories of the empire and the cult of the law entered its twilight.