Chapter Five

The Swansong of Legislation: the Palais-Bourbon Library

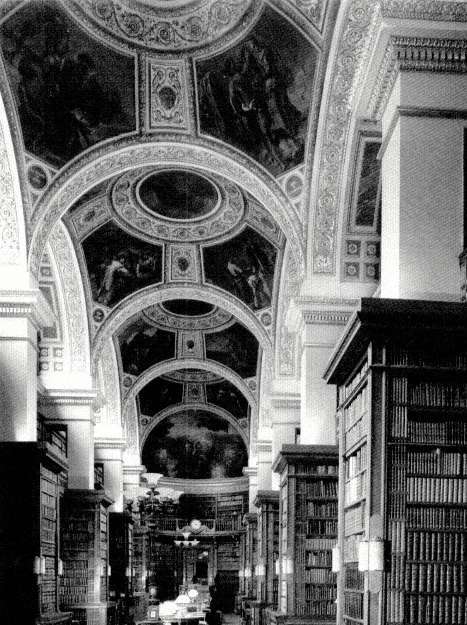

The embellishment of the Palais-Bourbon that included Delacroix's paintings in the Salon du Roi and Triqueti's Law reliefs in the Salle Louis-Philippe culminated in the new library.[1] Like the paintings for the Bourbon Council of State suite in the Louvre and the artist's earlier decoration of the Salon du Roi, the Palais-Bourbon library cycle was intended for an elite and cultured audience. Delacroix created a lavish working environment for the legislators for whom the impressive collection of manuscripts, maps, medals, and some fifty-four thousand volumes was reserved.[2] From 1838 to 1847 the artist and his assistants worked on two large murals, painted on the curved hemicycles at either end of the room, and twenty pendentive scenes, in groups of four, in five domed cupolas (Fig. 57; M in Fig. 40). Set into gilded moldings, the twenty-two paintings crown the room, with its monumental Dutch oak bookcases and ranges of old leather bindings, with Delacroix's resonant reds and blue-greens.

The library paintings, one of the most ambitious decorative undertakings of the nineteenth century, offer a panorama of considerable iconographic complexity. A description of the work by the sympathetic critic Théophile Thoré, based on notes provided by the artist, indicates that the twenty pendentive paintings correspond roughly to the fields of study by which libraries were then classified.[3]

The principal entrance to the forty-two-meter room is at its center, beneath a cupola decorated with subjects pertaining to legislation and eloquence. The cupolas to the left are those of theology and poetry; those to the right are devoted to history and philosophy, followed by science.[4] With their subjects drawn from

Fig. 57.

E. Delacroix, Palais-Bourbon library paintings, 1838-47. Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Scripture and the classical tradition, the paintings reflect the civilization whose origin is represented in the right hemicycle by Orpheus Comes to Civilize the Say-age Greeks and to Teach Them the Arts of Peace (Fig. 58). At the other end of the room, Attila, Followed by His Barbarian Hordes, Tramples Italy and the Arts dramatically closes the era initiated by Orpheus (Plate 7).

Even before the government decided to commission Delacroix to decorate the Palais-Bourbon library, on August 30, 1838, the artist had considered possible subjects, apparently with the aid of his learned friend Frédéric Villot. Enough documentation has survived to indicate that the program was determined only after the project was well under way.[5] Even before the ensemble was completely unveiled, the critic Louis de Ronchaud, who had written sympathetically of Delacroix's decoration of the Palais-Bourbon's Salon du Roi, admitted that he could not clearly comprehend "the mysterious correlation that must exist between these diverse subjects."[6] Similarly, Louis Clément de Ris, enthusiastic over parts of the cycle, nonetheless criticized the disunity of themes in the hemicycle and pendentive paintings.[7]

In 1968 George L. Hersey, attempting to dispel this confusion, proposed that the Palais-Bourbon library paintings have a comprehensive program based on the Neapolitan philosopher Giambattista Vico's Scienza nuova seconda (1744). To accommodate subjects that Delacroix could not have found there, however, Hersey was compelled to extrapolate from Vico's text. The elaborate and esoteric program presented by Hersey, moreover, has no counterpart in Delacroix's oeuvre .[8]

With the publication of Lee Johnson's catalogue and Anita Hopmans's analysis of the working method followed in the library commission, we can view this complex monument with greater clarity. Both commentators dispute Hersey's interpretation and accept, as basic to the work, the lack of strict organizational logic that troubled Ronchaud and C1ément de Ris. For Johnson the program is a diverse collection of scenes of great men and events, appropriate to a library for politicians, that defies any consistent principle of organization. Hopmans is more emphatic in denying the programmatic consistency of the cycle. She convincingly demonstrates its improvisation. An initial plan to follow Jacques-Charles Brunet's system of library classification was only partially implemented.[9] Hopmans concludes that "the decorations in the Palais Bourbon became a mishmash of different plans and unplanned inspirations"; that no iconographic link exists between the hemicycles and the twenty pendentive paintings; and that only a taste for the

Fig. 58.

E. Delacroix, Orpheus Comes to Civilize the Savage Greeks

and to Teach Them the Arts of Peace . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

dramatic and the exemplary can account for the choice of subjects.[10] Although the cycle does lack a consistent program, it has elements of thematic coherence, not noted in the art-historical literature, that reflect the artist's concern to address the needs of the legislators who read and conversed beneath his paintings.

From the outset Delacroix planned to refer to great authors and bibliographic subjects—in accord with both the traditions of library decoration and the architect's general plans for the embellishment of the room.[11] The concern to link the paintings and the legislative institution itself apparently evolved in the course of the work. As late as November 1842, with the science and philosophy-history paintings almost ready to be installed, the remaining subjects of the decoration were not final. In the following year the artist was planning to place paintings pertaining to theology in the center cupola.[12] Delacroix's belated decision to devote

Fig. 59.

E. Delacroix, Lycurgus Consults the Pythian Sibyl . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

the central cupola to legislation and eloquence gave these themes a salience reinforced by the placing of the ideal point of view for the entire ensemble beneath this central cupola.[13]

Johnson aptly observes that this symmetrical configuration is reinforced by illusionistic cornices crowning the fictive oculus of each cupola. Whereas the cornice of the central dome is depicted with radial symmetry, the cornices of the four other cupolas are increasingly foreshortened in proportion to their distance from the central bay.[14] The placement of the cupola with Lycurgus, Numa, Demosthenes, and Cicero in this privileged position was analogous to the library's acquisition policy, which had changed in the early 1830s. Since the establishment of the collection during the Revolution, the librarians had sought rare and beautiful books and manuscripts in all fields. Under Louis-Philippe, this policy yielded to the pursuit of materials on legislation.[15]

The central cupola, the visual and the thematic fulcrum of the decorative cycle, includes representations of two familiar lawgivers. Lycurgus, bearing a laurel branch and gesturing toward a sacrificial goat, asks the Pythian Sibyl about the durability of Sparta's laws (Fig. 59). In the adjacent pendentive, Numa reclines gracefully in a clearing, conversing with his legislative muse, the nymph Egeria (Plate 8), who sits like a relaxed monarch, with leaves for a crown and a stem for a scepter. A deer grazes nearby. Lycurgus's consultation of the sibyl and Numa's woodland conversation suggest the authority and calm intimacy the great library offered readers.

We have seen how the divine inspiration of these legendary legislators was repeatedly invoked in the chambers of the Council of State to forge a noble pedigree for the Charter of 1814 and to glorify the Bourbon monarchy. A sheet of studies for the legislation paintings in the Palais-Bourbon library suggests derivation from the Council of State suite, for which Delacroix had painted Justinian Drafting His Laws .[16] This sheet, with the notations "Muhammad and his angel," "Numa and the nymph," "Charlemagne and a Christian angel," "Moses and God," and "the people receiving the law" (among others) also bears two sketches, which, like the Council of State Justinian , show an authoritative figure accompanied by an inspirational genius (cf. Fig. 60 and Plate 6).[17] That the artist had this Bourbon decorative cycle in mind when elaborating legislation subjects for the library is further suggested by notes on this sheet linking the "emancipation of the serfs" and "Fields of May" to "progress in civilization and the legislation

Fig. 60.

E. Delacroix, studies for legislation cupola of Palais-Bourbon library. Cabinet des Dessins, Louvre, Paris.

of peoples." The emancipation of the serfs and the Fields of May (general assemblies in which Charlemagne met with notables of the empire) were both examples of medieval monarchic reform dear to the Bourbon Restoration. Blondel's decoration of the main assembly room of the Council of State (1827) included a fictive bronze relief, The Emancipation of the Serfs by Louis VI , as a historical example of the enlightened royal legislative prerogative that had culminated in the constitutional Charter of 1814. And the preamble of that Bourbon Charter refers to the Fields of May as one of the Old Regime institutions that, having so often given proof of "zeal for the interests of the people, of fidelity to and respect for the authority of kings," was being replaced by the Chamber of Deputies.

Although in the Palais-Bourbon library Delacroix drew on the iconographic tradition, practiced under Napoleon and during the Restoration, that associates the legislator with divinity, the Lycurgus and Numa pendentives, like his Justinian for the Council of State, have an expressive vitality that sets them apart from earlier representations of ancient legislators, which were stock accessories to narrowly didactic programs. Delacroix's pendentives are narrative vignettes, the Lycurgus charged with dramatic expectation, the Numa infused with pastoral calm.

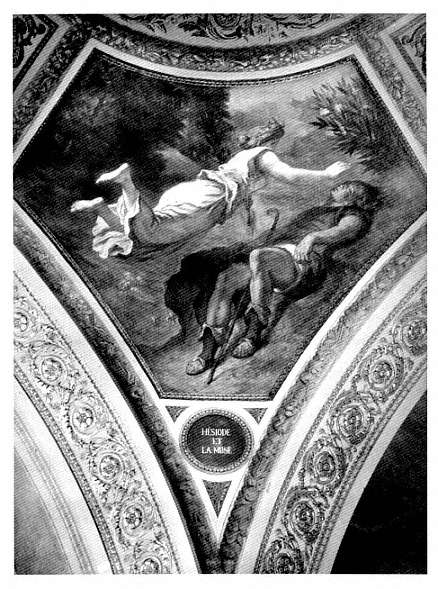

The theme of divine inspiration treated in the Lycurgus and Numa pendentives is echoed elsewhere in the library. In the poetry cupola, the sleeping Hesiod is inspired by a levitating muse in a serene floral setting like that in which Numa converses with the nymph Egeria (cf. Fig. 61 and Plate 8). Socrates, in the philosophy-history cupola, is accompanied, in the artist's words, by his "genius or familiar, who was perhaps only solitude itself or meditation, in which the true sages have always reinvigorated their souls and have drawn profound inspiration."[18] The philosopher, set apart by his red clothing from the somber, solitary grove, seems as dependent on the conventions of evangelical portraiture as the compositional sketches on the sheet of studies for the legislation and eloquence cupola (cf. Figs. 60 and 62).

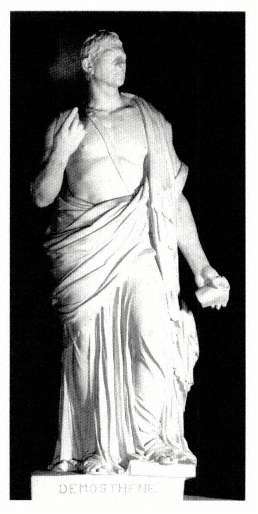

Eloquence was a subject germane to the Chamber of Deputies. The French legislature had, since its revolutionary beginning, cultivated artful oration, a practice silenced by Napoleon but resumed under the Restoration and July Monarchy. The deliberations of the Chamber, spread daily before the newspaper-reading public, were conducted in the great tradition of parliamentary debate that the architect Joly invoked proudly in his publication of the Palais-Bourbon renovations.[19] Eloquence is represented in the central cupola by two famous orators of Greece and Rome who had long had a home in the Palais-Bourbon. The pose and physique of Demosthenes, who addresses the waves to accustom himself to the tumult of the Athenian assemblies, recall those of a bare-chested statue of him by Antoine-Léonard Dupasquier commissioned under the Directory for the assembly hall of the Council of Five Hundred and moved to the new library's entry hall in the course of Joly's remodeling of the legislative palace (cf. Figs. 63 and 64). Along with the representation of Demosthenes in the central cupola is one of Cicero, who vigorously points to the ill-gotten treasure of the wicked magistrate Verres (Fig. 65). François Masson's sculpture of the Roman orator was moved, with Dupasquier's Demosthenes , from the old Salle des Séances to the new library's entry hall.[20]

Fig. 61.

E. Delacroix, Hesiod and the Muse . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 62.

E. Delacroix, Socrates and His Familiar . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 63.

E. Delacroix, Demosthenes Harangues the Waves of the Sea . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 64.

A.-L. Dupasquier, Demosthenes ,

1796-98. Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

The two great hemicycles representing the birth and death of classical civilization and counterpointing the themes of peace and war also pay homage to the unity of law and civilization. Under the auspices of Athena and Ceres, Orpheus introduces an untamed company of old and young to the civilization that would eventually produce the humanistic studies represented in the pendentive paintings (Fig. 58). Orpheus, traditionally identified as the first lawgiver, is referred to as the "poetic legislator" in a review of the paintings.[21] The order and calm brought by Orpheus are reflected in the blue-green sweep of mountains enclosing a stable, if rather conventional, pyramidal composition.

At the opposite end of the library, Attila tramples civilization, which collapses in anarchy before his marauding host (Plate 7). The somber emotional tone of this scene reverberates in the clash of red and blue-green, in the diagonal thrust of limbs, and in the broad handling of Attila's charger, which occupies center stage beneath a dark cloud. A winged putto flees before the invader with a lyre and scroll, representing music and literature,[22] attributes that also refer to Orpheus, who holds a scroll. Beside this putto, near a crowned and fallen allegory of Italy, the art of eloquence is represented by a tearful woman fleeing with a caduceus and laurel leaves.[23]

Hopmans has dated the conception of the Orpheus and Attila hemicycles as subsequent to the publication of two articles in the Revue des deux mondes , January 1 and 15, 1843, passages of which Delacroix copied on sheets bearing studies for the library hemicycles. The first passage refers to James Barry's painting Orpheus Instructing a Savage People in Theology and the Arts of Social Life (1777-84) in the Royal Society of Arts building, London. The second compares Napoleon's destruction of Moscow to the ravages of Attila.[24] Although this discovery demonstrates that the hemicycle subjects were determined surprisingly late, Orpheus the civilizing legislator was nonetheless, like Attila and the barbarian invasion, a familiar point of reference in Delacroix's France. The familiarity of these motifs, moreover, made them all the more appropriate for use in a state commission.

According to classical tradition, Orpheus was the initiator of law and civilization. The treatment of this theme by Horace in the Ars Poetica was imitated by Boileau in his Poetic Art (1674), that canonical monument of French classicism.[25] Boileau emphasized the civilizing force of the first laws associated with Orpheus:

Before reason, borne by speech,

Had instructed humankind and brought it laws,

People knew only base instinct.

Dispersed in the woods, they ran off to feed.

Force usurped right and equity;

Murder went unpunished.

But finally the harmonious skill of discourse

Tempered the rudeness of these savage customs;

Assembled the people scattered in the forests;

Enclosed cities with walls and ramparts;

Frightened insolence with the threat of punishment;

And placed Feeble innocence under the laws protection.

This order, they say, sprang From the first verses.

From those have arisen the rumors heard by all,

That tigers were tamed by the tones of Orpheus's voice

As it resounded among the mountains of Thrace.[26]

More recently, the Lyonnais mystic Pierre-Simon Ballanche had treated the theme at length in his philosophical novel Orphée (1829).[27] Delacroix's placement of the slaughter of a deer and the cultivation of the soil at either side of the central group of Orpheus and his rustic pupils recalls a lesson of this odd but ambitious book that so delighted Delacroix's friend George Sand.[28] Orpheus, revealing "the foundations of the laws on which human institutions rest," teaches that "the first way to civilize men is to teach them to sow wheat." People will remain in a savage state, Ballanche maintains, as long as they continue to live from day to day, hunting animals and eating roots and wild fruit.[29]

Delacroix was not the first to associate Orpheus with the national legislature. The reverse of the identification medals by Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux, distributed under the Directory to the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients, bears an emblematic panoply that includes an Orphic lyre (Fig. 66; see obverse, Fig. 8). With ingenious economy, Gatteaux concealed the strings of the instrument behind the rods of a fasces topped by a Phrygian cap and flanked by boughs of laurel and oak. The arms of the instrument serve as the ends of two cornucopias. This design was repeated in medals for the legislature in successive years; examples are in the collection of the Palais-Bourbon library.

Attila and his barbarian hordes were as familiar as Orpheus to literate citizens under the July Monarchy. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the barbarian invasion had been a common point of reference for French authors. The motif was often employed—sometimes pejoratively, sometimes not—in the treatment of such large historical themes as the condition of France since the Revolution and the progress of democracy.[30] A distinguished example occurs in Lamartine's poem "Les Révolutions," written in early December 1831 under the influence of the insurrection in Lyon and published in 1832:

Levez-vous, Gaule et Germanie,

L'heure de la vengeance est là!

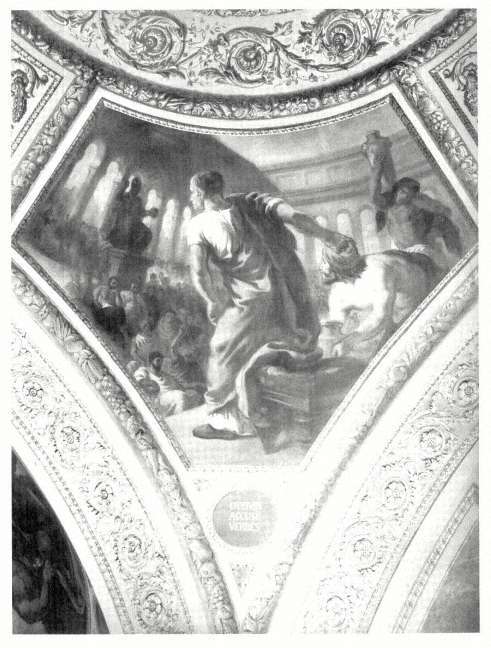

Fig. 65.

E. Delacroix, Cicero Accuses Verres . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 66.

N.-M. Gatteaux, membership medal for Council of

Ancients (reverse), 1797. Musée de la Monnaie, Paris.

Des ruines, c'est le génie

Qui prend les rênes d'Attila!

Lois, forum, dieux, faisceaux, tout croule;

Dans l'ornière de sang tout roule,

Tout s'éteint, tout fume. Il fait nuit,

Il fait nuit, pour que l'ombre encore

Fasse mieux éclater l'aurore

Du jour[*] où son doigt vous conduit![31]

Rise, Gaul and Germany,

The hour of vengeance has come!

The spirit of ruin

Drives Attila on!

Laws, forum, gods, fasces, all crumble;

[*] Christianity [Lamartine's note].

Fig. 67.

A. Vinchon and N. Gosse, The Barbarians Destroying the Monuments of Greece , 1827. Louvre, Paris.

All tumble onto the bloody, rutted earth,

All are snuffed out, all smoke. Night has fallen,

Night has fallen so that against the darkness

The [Christian] dawn into which you are led

Will shine all the more brightly!

Although it is unlikely that Delacroix identified with Lamartine's Christian piety (later he said some unkind things about the poet),[32] the vanitas theme in this poem resembles that of Delacroix's pessimistic Journal .

Three images of barbarian invasion offer further examples of the theme. In the year following the commissioning of Delacroix's Council of State Justinian , Auguste Vinchon and Nicolas Gosse painted illusionistic reliefs in grisaille for the Louvre's Musée Charles X, including an Orpheus Singing as well as The Barbarians Destroying the Monuments of Greece (Salon of 1827).[33] In the latter, a slain Greek lies with a lyre pinned to his back by the shaft of a weapon (Fig. 67). Delacroix could have known, in reproduction, a grandiose Battle of the Huns by the Munich court painter Wilhelm yon Kaulbach (1805-1874) in which barbarism and Christianity are locked in airborne combat (Fig. 68).[34] Although Delacroix would not have been impressed by the dry linearity and turgid melodrama of this

Fig. 68.

J. Thaeter after W. von Kaulbach, Battle of the Huns ,

1837. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

German image, both he and Kaulbach address the theme allegorically. The motif of barbarian invasion also appeared in the popular satirical press. The October 13, 1831, issue of La Caricature included Denis-Auguste-Marie Raffet's pessimistic "Barbarism and Cholera Morbus Enter Europe," which denounced the impotence of France and the other European powers in the face of Russia's tyranny over rebellious Poland (Fig. 69). The caricaturist links political oppression with the looming specter of a cholera epidemic.[35]

Fig. 69.

D.-A.-M. Raffet, "Barbarism and Cholera

Morbus Enter Europe." La Caricature , October 13, 1831.

Whereas these images suggest that in the Attila hemicycle Delacroix employed a familiar motif, a more concrete analogy can be drawn between his representation of Italy, defenseless and bare-breasted, under the hoofs of the Hun's steed and that of a mother trampled in the foreground of The Destruction of Jerusalem (Fig. 70) by François-Joseph Heim (1787-1865).[36] In this vast Restoration machine , Heim portrayed an invasion as terrible as that of Attila, "the scourge of God," and, like it, providentially ordained. The destruction of Jerusalem by Titus was traditionally viewed as divine punishment of the Jews for their rejection of Christ.[37]

Delacroix was not the first to pair an Orphic legislator with Attila. In Attila et le troubadour , a play staged once in 1824, the invader is subdued by the patriotic French troubadour Roger, who accompanies himself on his lyre as he sings of his vocation: "He is the legislator of burgeoning nations. . .. He cultivates those he

Fig. 70.

F.-J. Heim, The Destruction of Jerusalem , Salon of 1824. Louvre, Paris.

assembles. His art masters hearts and minds. His voice brings harvests and cities, commerce and laws to the sterile plains. And in his poor sanctuary, he is richer, more tranquil, and greater than Attila."[38]

Even if Orpheus, Attila, and the barbarian invasion were familiar motifs, Delacroix's choice of them for the Palais-Bourbon library was as bold as the style in which he painted Attila . Like the Orpheus and Attila paintings, Triqueti's monumental Protecting Law and Avenging Law reliefs—whose position in the nearby Salle Louis-Philippe parallels that of the library hemicycles—represent the dependence of civilization upon law. Whereas Triqueti gives this theme conventional, if elegant, allegorical form, Delacroix's hemicycles are imbued with a mythic amplitude that sets them apart from most official allegory of the period. Delacroix, moreover, offers a pathos-ridden contrast between the calm dawn of civilization

Fig. 71.

T. Chassériau, study for Peace for Cour des Comptes , 1844-48. Cabinet des Dessins, Louvre, Paris.

and its violent end, whereas Triqueti idealistically glorifies the law. In their setting, Triqueti's reliefs constitute an abstract allegorical component of a program that celebrates French constitutional law (its principal ornament was Jacquot's colossal statue Louis-Philippe Swearing Loyalty to the Charter ). Delacroix's decoration of the library, in contrast, operates on the plane of legend rather than historical specificity.

Allegory in the library hemicycles shows none of the narrow didacticism found elsewhere in the Palais-Bourbon; Delacroix's breadth of reference recalls the epic polarity of Ingres's Age of Gold and Age of Iron murals at the Château of

Dampierre (begun in 1843 and left unfinished in 1850). The murals War and Peace (now mostly destroyed) that Delacroix's young admirer Théodore Chassériau painted in the ill-fated Palais d'Orsay for the Court of Accounts (1844-48) reveal a similar thematic breadth; I reproduce a study for Peace (Fig. 71).[39] In a general way, Delacroix's counterpoint of Orpheus and Attila reflects a fascination with universal history and providential design that was widespread under the July Monarchy. But Delacroix gives no hint of the dogmatic optimism of contemporary utopian theorists vis-à-vis human history and destiny. The skeptical artist had little patience with would-be saviors of humanity.[40]

The central cupola, both honoring and setting a high example for the Chamber of Deputies with references to the legendary orators and lawgivers of antiquity, stands equidistant from the hemicycle paintings representing civilization's birth and collapse. Delacroix alluded to the Chamber of Deputies in the library paintings in other ways as well.

All twenty pendentives refer to the disciplines represented in the library collection. This loosely defined program could have accommodated an almost limitless variety of subjects; such openness led to an ongoing revision of the themes projected for inclusion. Although any attempt to link the remaining sixteen pendentives to the legislative function of the library would misconstrue the irregular development of the cycle, some of the subjects seem to have been selected for their thematic relevance to the function of the Palais-Bourbon.

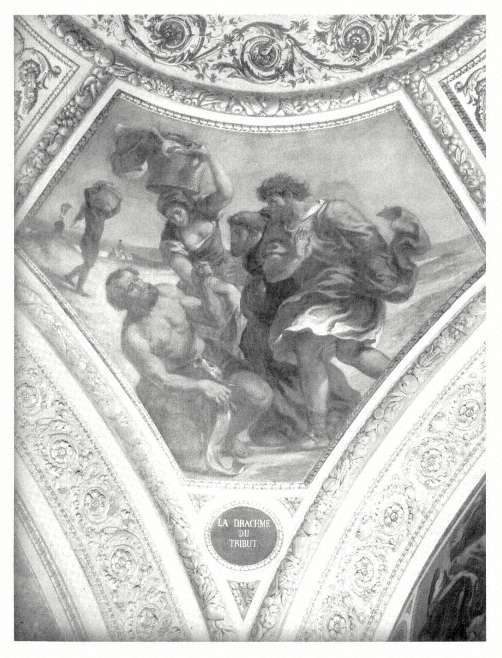

For example, The Drachma of Tribute (Fig. 72), an uncommon subject in the theology cupola that especially puzzled one commentator,[41] illustrates the fulfillment of Christ's prediction that money to pay a tax would be found in a fish (Matthew 17:24). It is one of the most complex compositions in the library. The astonishment of Peter and the other witnesses to the miracle is accented by great flourishes of windswept cloth that cut irregular silhouettes against the seaside sky. Like the decision to grant pride of place to the legislation-eloquence paintings, the choice of this story of how the payment of a tax received divine sanction was particularly appropriate to the institutional setting of the library. For tax legislation was not only one of the principal responsibilities of the Chamber of Deputies but also the sole domain in which the charter granted the deputies hegemony in the legislative process.[42]

Delacroix's concern to address the library's function could account for his curious idea of devoting a pendentive to the theme of education. As Hopmans has

Fig. 72.

E. Delacroix, The Drachma of Tribute . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

pointed out, he departed from Brunet's system of book classification and included The Education of Achilles in the poetry cupola, despite its apparent thematic inconsistency with the three companion pendentives.[43]The Education of Achilles provides a buoyant and muscular counterpart to the adjacent scene of Hesiod and his floating muse (cf. Figs. 61 and 73). This was clearly a sympathetic subject for the exalted imagination of the artist. But two considerations should be added to the "subject's special charm," which Hopmans sees as the principal reason for its inclusion. Clearly, The Education of Achilles refers to the function of the library. But its theme seems all the more appropriate in light of the notion, inherited from the Enlightenment, that the legislator was a moral tutor, responsible for educating the citizenry in virtue and civic patriotism.[44]

Before receiving the library commission, Delacroix had proposed an aggressively nationalistic program for the ceiling of the Salle des Pas Perdus (grand foyer) of the Palais-Bourbon, a surface eventually covered, to his disgust, by Horace Vernet.[45] Delacroix's unrealized project, illustrating historical examples of France's military and cultural hegemony, is echoed by two pendentives with broader historical reference and greater subtlety that offer models of patriotic conduct to the Chamber of Deputies. In the science cupola, the incorruptible Hippocrates refuses to treat the Persian enemy despite their offer of treasure. The adjacent Death of Pliny the Elder (Fig. 74) also offers an example of patriotic resolve. "Pliny studied nature to better admire Italy; he boasted of his country as the most beautiful"—thus sang the heroine of Madame de Staël's popular novel Corinne, or Italy (1807) at Cape Miseno, in an episode made all the more famous when François Gérard (1770-1837) painted it (Fig. 75).[46] "In pursuit of scientific knowledge . . . he left this very promontory to observe Vesuvius through the flames, and these consumed him."[47] With a rhetoric of terribilità that recalls Gérard's Corinne , Delacroix's Pliny dictates to his scribe as he sacrifices himself to science and the glory of Italy.[48] This inspired dictation is derived from that of the Council of State Justinian .

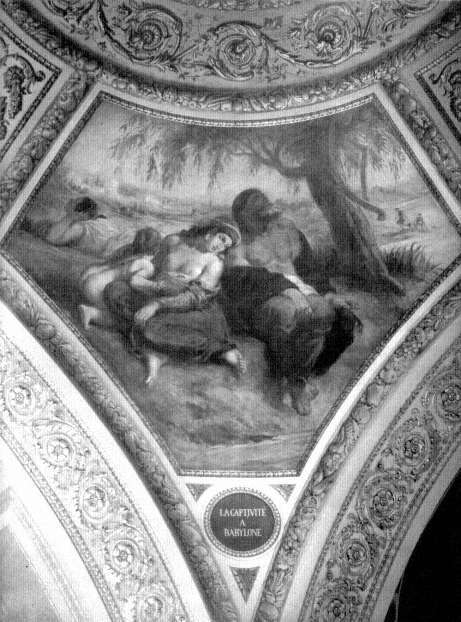

The theme of devotion to the homeland is echoed by three subjects that evoke the pain of exile, each a mournful counterpart to the patriotism of Hippocrates and Pliny: the Babylonian captivity, the expulsion of Adam and Eve, and Ovid in exile. The surprising inclusion of these subjects in the theology and poetry cupolas stems from an attraction to a theme that was an integral part of modern French history, from the flight of the aristocracy during the Revolution to the

Fig. 73.

E. Delacroix, The Education of Achilles . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 74.

E. Delacroix, The Death of Pliny the Elder . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 75

F Gérard, Corinne at Cape Miseno , 1822. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon.

confinement of Napoleon on the island of Saint Helena. "Everywhere . . . the exile elicits a generous interest," according to the contemporary Encyclopédie des gens du monde ; "one is moved by the sight of him, and one feels then how piteous is he who must drag out his existence on foreign soil, far from the tender mother who carried him in her womb and nourished him with her milk, far from a white-haired father who . . . fears to die without seeing his son!"[49] Such feelings were fanned by the plight of Poland following the failed insurrection of 1831, when such Poles as Delacroix's dear friend Chopin found sanctuary in Paris.[50]

In Delacroix's Babylonian Captivity , "a weeping family, seated at the edge of a river, sadly contemplates the waves while thinking of home."[51] The subject comes from Psalm 137 in which the Hebrews, driven from their homeland following the fall of Jerusalem, vow never to sing their national songs before their captors (Fig. 76). Long admired by French authors, this psalm was one of the most

Fig. 76.

E. Delacroix, The Babylonian Captivity . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

Fig. 77.

R. Cazes, The Babylonian Captivity , Salon of 1837. Musée Ingres, Montauban.

frequently translated and paraphrased passages of the Bible during the eighteenth century.[52] Racine imitated it in the chorus for Esther ; Lord Byron paraphrased it in A Selection of Hebrew Melodies (1815; translated into French, 1821);[53] and the hero of Casimir Delavigne's "Jeune diacre, ou La Grèce chrétienne" (1822) invoked it. Delavigne's poem, written to elicit sympathy for the cause of Greek independence, provided Delacroix with the subject for a sketch.[54]

Before Delacroix painted it in the theology cupola of the library, the Babylonian captivity theme had appeared in Salon paintings (Figs. 77, 78) by Romain Cazes (1810-1881) and Angel Joyard (1809-?).[55] Louis de Planet (1814-1875), a close friend of Cazes's and one of Delacroix's principal assistants on the library commission, also treated the subject in a painting that may have inspired the library pendentive (Fig. 79).[56] With neither Planer's overblown gesticulation nor Cazes's and Joyard's ingratiating details of costume and setting, the Delacroix pendentive has a poignant breadth and economy that are even more pronounced in a related

Fig. 78.

A. Joyard, "The Babylonian Captivity." L'Artiste , 2d series, VIII, 1841.

Thomas J. Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fig. 79.

Mouilleron after L. de Planet,

"The Babylonian Captivity,"

1842-43, Bulletin de l'ami des arts .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 80.

E. Delacroix, The Babylonian Captivity . Cabinet des Dessins, Louvre, Paris.

watercolor from the artist's hand (Fig. 80).[57] At the same time, the library pendentive, like other paintings on the theme, is charged with a torpor that recalls the sense of national bereavement in France under Louis-Philippe, one expressed in the fascination with Napoleon that Delacroix shared with so many of his fellow citizens.

Two years after receiving the commission for the Palais-Bourbon library, Delacroix was chosen by the government to decorate the library of France's other legislative body, the Chamber of Peers, in the Palais du Luxembourg. Delacroix's decoration here provides an instructive comparison with his more elaborate work at the Palais-Bourbon. His distinct treatment of each commission, moreover, indicates his concern to tailor his work to the institution.

Fig. 81.

E. Delacroix, dome of the Palais du Luxembourg library (detail),

1840-46. Palais du Luxembourg, Paris.

In the domical cupola at the center of the Luxembourg library Delacroix portrayed four groups of great philosophers, poets, legislators, and heroes, an assembly loosely based on the description of limbo in canto iv of Dante's Inferno (Fig. 81).[58] In the principal group Virgil introduces Dante to Homer, who is accompanied by the poets Ovid, Statius, and Horace. To one side of this group are such illustrious Greeks as Achilles, Socrates, Plato, and Demosthenes; to the other side are famous Romans, including Cato of Utica, Marcus Aurelius, Trajan, and Cicero. Opposite the Homer group, Orpheus sings before Sappho and Hesiod. "In brief," Delacroix wrote to the critic Gustave Planche, "one sees there [in the Luxembourg dome] as many great men as possible, walking and sitting at their pleasure."[59] This serene gathering, crowned by inscriptions from Dante borne

aloft by an eagle and two winged putti, is complemented by the pendentive paintings Eloquence, Poetry, Theology (Saint Jerome ), and Philosophy and by the fan-shaped mural Alexander Ordering That the Poems of Homer Be Placed in a Golden Casket in a hemicycle below. The last work, whose subject was also featured in the poetry cupola of the Palais-Bourbon library, showed how a mighty ruler respected works of genius.[60]

Commentators on the two library commissions have failed to remark that the contrast between the luminous apotheosis Delacroix placed above the peers and the dynamic, often violent, imagery of the Palais-Bourbon library mirrors the distinction between the two legislative assemblies. Whereas the Chamber of Deputies was a controversial forum, an elective body answerable to approximately 250,000 adult French males with property taxes sufficient to qualify as voters, the Chamber of Peers, whose members were appointed by the king, was a deliberative, conservative assembly. Significantly, the artist discarded an early project for the Palais-Bourbon library with hemicycles depicting a coronation of Petrarch and Socrates and his pupils discussing the immortality of the soul.[61] This project apparently would have paid homage to the iconographic tradition established by Raphael's frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura and continued by Ingres's Apotheosis of Homer . Close in spirit to the sedate work Delacroix painted in the dome of the Chamber of Peers' library, this proposal was superseded by the dynamic counterpoint of Orpheus and Attila.

Although it is not certain that Delacroix entered into a conscious dialogue with the visual and literary prototypes I discuss, my examples comprise only those he could have known. The evidence, moreover, suggests that the subjects Delacroix chose and the thematic relations I detect had currency in France under Louis-Philippe. Delacroix was concerned to choose subjects that would be familiar as well as appropriate.

The internal coherence of the Palais-Bourbon library paintings and their suitability to their setting, elements clear enough in retrospect, do not alter the bewilderment that even sympathetic contemporaries felt before the cycle. Delacroix, recognizing the program's potential for misinterpretation, provided his supporter Thoré with a description of the work for publication.[62] The opacity of the program merits further consideration.

At the outset Delacroix wrote his learned friend Frédéric Villot that what was needed was "a fertile idea, neither too real nor too allegorical, that has, finally,

something for every taste."[63] Such concern to accommodate his audience, we have seen, guided the artist's choice of familiar subjects that at once glorified the humanistic studies represented in the library's collection and cited the inspiration, authority, and patriotism of ancient luminaries whom contemporaries could have considered "legislators" in their own right. For in this period the word legislator could mean "one who establishes the principles of an art, [or] of a science."[64] Delacroix's effort to link reality and allegory is also evident in his use of complex, expressive narratives in a context that conventionally called for something more static and emblematic. Such an approach had been successful in his earlier Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826) and Liberty Leading the People (1830), to which full-blooded corporeality gave a sense of immediacy and actuality. But in decorating, as the artist noted in his journal, "one is compelled to subordinate many parts" (July 1, 1847).[65] Delacroix was unable to do this in the Palais-Bourbon library, where diverse, emotionally charged narrative overpowers the program's larger themes.

Delacroix gave the ensemble a measure of unity by linking disparate motifs under large thematic categories. The Hippocrates and Pliny pendentives can be associated with the theme of patriotism; The Babylonian Captivity, Adam and Eve , and Ovid in Exile all pertain to exile; the theme of divine inspiration, represented by Lycurgus, Numa, Hesiod , and Socrates , is echoed in the Pliny pendentive. This decorative cycle thus shows the consistency of theme and expressive tenor that link diverse subjects Delacroix treated in his career. For example, he repeatedly used the storm-tossed boat motif—in the Barque of Dante (Salon of 1822), The Shipwreck of Don Juan (Salon of 1841), and the versions of Christ on the Sea of Galilee (1853-54).[66] But the storm-tossed boat paintings have a private, autobiographical meaning at odds with the public character of an official decorative cycle. Delacroix's subordination of subject to theme—his willingness to offer multiple variations of related subjects to satisfy the expressive needs of a larger obsessive theme—does not lend itself to the discursive clarity critics hoped to find in his paintings for the Palais-Bourbon library.

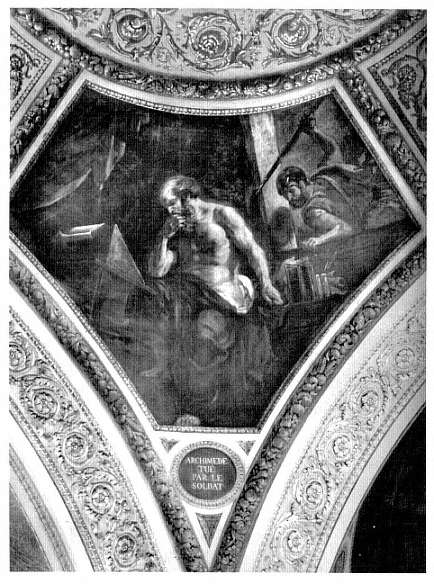

Although the Chamber of Deputies' library is untroubled by Delacroix's calm Orpheus, Numa and Egeria , and Hesiod and the Muse , the artist gave free rein there to the proclivity for the tragic evident since his Barque of Dante, Massacre of Chios , and Death of Sardanapalus had brought damnation, blood, and flame to the Salons of the Restoration. "My tragic inclinations always dominate me," he confessed,

"and the Graces rarely smile on me."[67] The severed head of John the Baptist, the stoical suicide of Seneca, the bitterness of exile, and the murder of Archimedes as he sits engrossed in study (Fig. 82)—the last a chilling example of studious absorption for the library clientele—cast a pall over the didactic idealism of the ensemble.[68]

Of the twenty-two paintings in the library, the Attila hemicycle is the most impressive. It evokes the pessimism of the artist's journal. "The most extreme civilization," he wrote on a sheet enclosed in a notebook of 1847, "cannot banish from our cities the most atrocious crimes, which seem to belong to peoples blinded by barbarism."[69] "Sickness, death, poverty, the torments of the soul, all are eternal, and will torture humanity under every kind of government; the form, democratic or monarchical, has nothing to do with the case."[70]

Such pessimism was only confirmed by the vicissitudes of mid-century French politics. In the year following the collapse of the July Monarchy, the artist wrote in his journal:

From knowledge which has been growing inescapable for a year, I believe one can affirm that all progress must necessarily carry with it not a still greater progress, but finally the negation of progress, a return to the point from which we set out. The history of the human race is there to prove it. . . . Is it not evident that progress, toward good or toward evil, has today brought society to the edge of an abyss into which it may very well fall, to make way for a state of complete barbarism?[71]

And the following year brought no relief:

Man himself, when he gives way to the savage instinct which is the very basis of his nature, does he not conspire with the elements to destroy the works of beauty? Does not barbarism, like the Fury who watches Sisyphus rolling his stone to the top of the mountain, return almost periodically to overthrow and confound, to bring forth night after a too brilliant day? . . . Almost all the great men have had a life more thwarted, more miserable than that of other men.[72]

The tragic vision of the Palais-Bourbon library paintings competes with their ostensible function as embellishments of the legislative palace. This dichotomy

Fig. 82.

E. Delacroix, Archimedes Killed by the Soldier. Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

distinguishes the work from the earlier, less extensive, commission to decorate the Salon du Roi. It is likely that Delacroix's work there—it was his first major decorative commission—received official guidance and approval from Thiers, the sympathetic minister in charge of the project. Notwithstanding the stylistic innovation of these paintings, they conform to the functional requirement, to glorify the monarch who was the focus of attention when the Salon du Roi was in ceremonial use. In the library, where Delacroix had a more elaborate interior space at his disposal and was apparently free to determine his own program, he produced a decorative cycle that, if more evocative, bears a less apparent connection to the institution it adorns.

Together with his contemporary work for the Chamber of Peers, Delacroix's decoration of the Palais-Bourbon library represents one of the final triumphs of a tradition of heroic allegorical decoration largely moribund since the century of Tiepolo and Le Moyne. Unlike the works commissioned under the Restoration for the Council of State, for example, the paintings in the Palais-Bourbon library are integrated with their architectural setting even as they escape the narrow didacticism of most contemporary official art. But Delacroix's success in revitalizing this languishing heritage was tempered by the idiosyncrasy of the program. Although Delacroix confidently employed the lofty rhetoric of baroque allegory, with its goddesses, personifications, and muses, his cycle lacks the serene faith in divine Providence that informs the earlier tradition.

This problematic embrace of tradition recalls Delacroix's frustrated ambition to be accepted by the official art establishment, a goal he finally accomplished in 1857, six years before his death, with his admission to the Institut de France after seven failures in twenty years. And in the artist's erratic and ambitious search for noble subjects to glorify Western civilization there is an element of comic pathos that foreshadows the ridiculous foray into universal knowledge undertaken by Flaubert's Bouvard and Pécuchet.

Although Delacroix's decoration of the Palais-Bourbon and Luxembourg libraries has a sense of conviction rare among the many public decorative commissions of the July Monarchy, his exalted imagery is anachronistic. With the fall of the July Monarchy—the regime that had been so generous in awarding decorative commissions to Delacroix—the brilliant aura that had surrounded law and the legislator since 1789 was dimmed.

When, to Delacroix's dismay, the revolutionaries of February 1848 attempted to establish an egalitarian republic, the cult of law that had arisen in France's first legislative assemblies had been blunted by more than half a century of banal parliamentary government and nine constitutions. Lamartine's election to the Chamber of Deputies in 1833 might have seemed to vindicate the Romantic notion of the poet-legislator; the prosaic legislative work pursued in the Palais-Bourbon, however, justified the satiric question asked as Lamartine began his legislative career: "Giant, why does he come to struggle against dwarfs?"[73]

For such dwarfs Delacroix provided the exalted imagery of the libraries of the Bourbon and Luxembourg palaces. Alexis de Tocqueville—one of the most distinguished members of the Chamber of Deputies under Louis-Philippe—witnessed the legislature's decline in prestige that is so painfully evident in Daumier's Legislative Belly . Looking back on the regime that fell in February of 1848 he wrote:

I do not know whether any parliament . . . has ever comprised more varied and brilliant talents than ours during the last years of the monarchy of July. I can affirm, however, that these great orators detested listening to each other, and, all the worse, the entire nation was bored hearing them. The nation inadvertently became accustomed to seeing in the struggles of the Chambers exercises of wit rather than serious discussions and, in all that divided the different political parties, . . . domestic quarrels between children . . . trying to cheat each other in the distribution of the family inheritance.[74]

The peers enjoyed no more prestige than the quarrelsome children of the Palais-Bourbon. Although the Chamber of Peers was described in article 20 of the 1830 charter as "an essential part of the legislative power," under Louis-Philippe the Luxembourg Palace was, in the words of one historian, "a house of rest" under whose roof could be found mostly "men fatigued by age."[75] Unencumbered by Delacroix's obligation to dignify the legislature, Heinrich Heine summed up the relation between the peers and deputies: "The few grey-headed old men who sit in the Luxembourg murmur more and more softly, or half lost in sleep nod their assent to the decisions of the younger Chamber."[76]

The peers' sleep was troubled during the period when their Chamber served as a high court of justice in the trial of 121 defendants arrested after insurrections

Fig. 83.

H. Daumier, "You Have the Floor, Explain Yourself, You Are Free!"

La Caricature , May 14, 1835. Boston Public Library.

that began in Lyon in April 1834 and spread to Paris, site of the Rue Transnonain Massacre. In the May 14, 1835, issue of La Caricature , Daumier summarized the proceedings of what became known as the procès monstre (monster trial) in a manner that the censorship laws, enacted the following September, would have prohibited. His defense torn at his feet, a forcibly restrained defendant is told: "You have the floor, explain yourself, you are free!" Before a somnolent audience of peers, another hapless victim of injustice is prepared for execution (Fig. 83).[77] Like Daumier's Legislative Belly , this travesty of the peers exercising their most solemn duty keenly insulted a regime founded on legal integrity.

With the discrediting of the legislature, how could Delacroix's glorification of the civilizing force of law, his representation of the lawgiver's divine inspiration, and his invocation of the patriotism expected of the nation's representatives continue to speak to visitors to the Palais-Bourbon library? Delacroix himself, recalling a tiresome evening at the home of the former prime minister, revealed that he regarded legislative affairs with the very indifference Tocqueville found so lamentably widespread. "Dined at the house of M. Thiers," he recorded on January 26, 1847. "I don't know what to say to the people that I meet at his house, and they don't know what to say to me. From time to time, noticing the deep boredom produced in me by those conversations of politicians about the Chamber, etc., they talk painting with me."[78] Such impatience could only have compounded Delacroix's difficulties in providing a lofty and cohesive ensemble for the Palais-Bourbon library in the twilight of the cult of law.