The Big City

Urbanscape

15. New York, 1849. Half a million people crammed into a jumble of small buildings, with single-family houses, boardinghouses, warehouses, factories, slaughterhouses, and churches—a typical early industrial hive. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

16. Boston, 1855. Four- and four-and-a-half-story shops and houses of the West End, masts of ships in the harbor behind Brattle Square church. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937

17. San Francisco, 1850-51. A regional trading city begins as a country town. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937

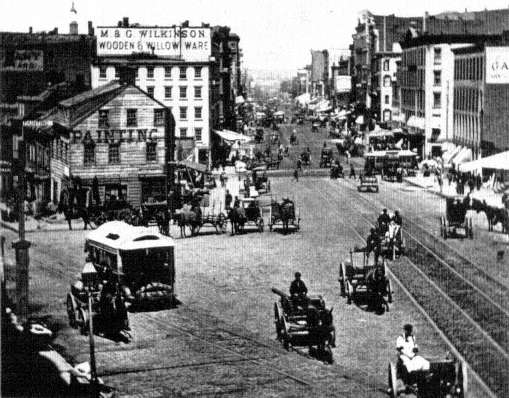

18. Broadway, New York, 1834. Unpaved street, with horse-drawn omnibusses, wagons, and carriages which passed busy sidewalks edged with storefronts, awning poles, and frames of streetside peddlers. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

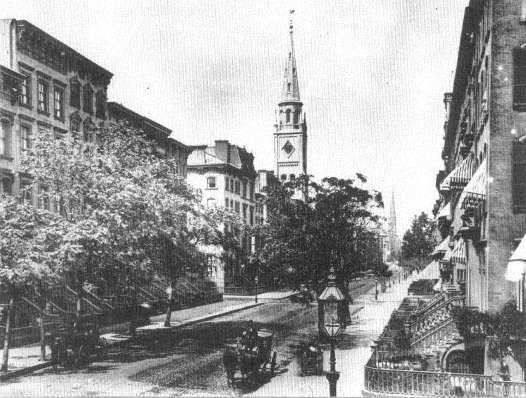

19. Broadway, New York, 1870s. Public amenities of cobblestone pavement and gas lights have been added, and buildings have grown to five and six stories since 1834, but the traditional urban framework of full sun-lit streets with horse-drawn traffic and busy pedestrian sidewalks still contain the intense clustering of commerce and manufactures. New-York Historical Society

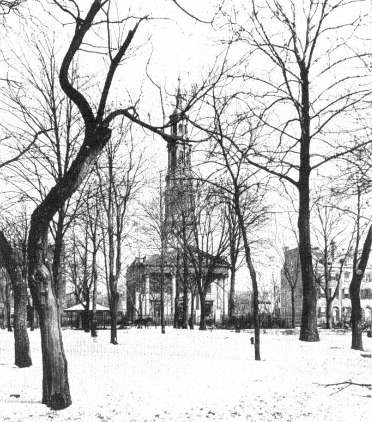

20. Hudson Square, New York, 1866-67. Relentless moneymaking left few open spaces in big cities of the early industrial era. Here, St. John's Church and houses for the wealthy of the Federal days provide a rare interval of urbane relief. New-York Historical Society

21. Fifth Avenue from 28th Street, New York, 1865. Ultimate amenities of big-city residential life: clean, paved streets and sidewalks, cabs at the curb, gas lights, cast-iron fences, basement kitchens, servants in the attic, modern plumbing, and an unbroken strip of brick and brownstone row house propriety, with a few young trees. New-York Historical Society

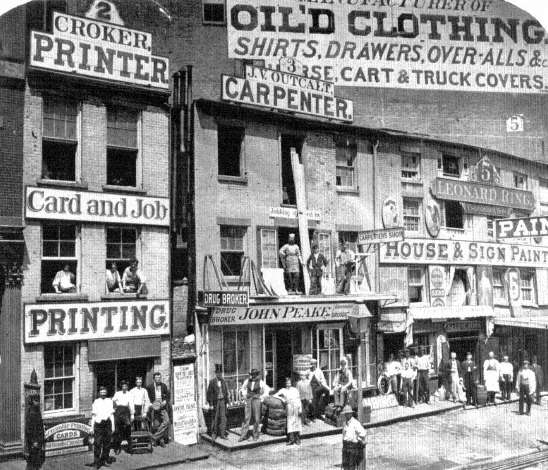

22. Working-Class New York, Canal and Mott Streets, ca. 1870. The workingman's big city, with factories, craftsmen's rooms, cheap retail stores, slum housing, in varied buildings—from old wooden houses and well-propor-

tioned Federal blocks to the new tall, narrow, heavy-corniced tenements of contemporary fashion. New-York Historical Society

23. West Washington Market, New York, 1880s. As the city's population grew, markets expanded from old neighborhood stalls, where housewives shopped daily, to specialized farmers' and grocers' wholesale distributing centers. Here, a market built in 1858. New-York Historical Society

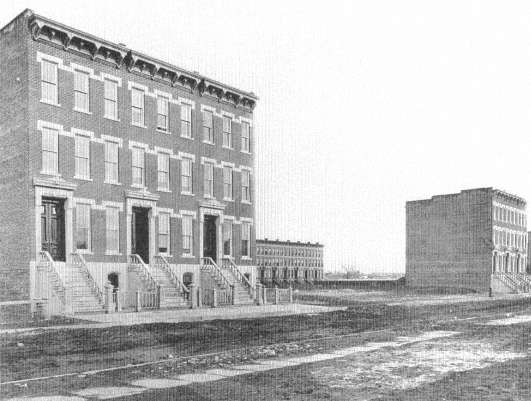

24. West 133rd Street, New York, ca. 1877. Like today's suburban fringes, speculators' housing took up broken parcels of land at the city's growing outer edge. New-York Historical Society

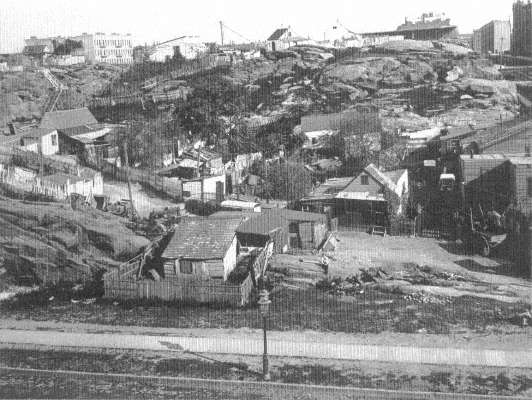

25. Fifth Avenue, 116th and 117th Streets, New York, 1893. The fringe shanties of the poor. New-York Historical Society

Business

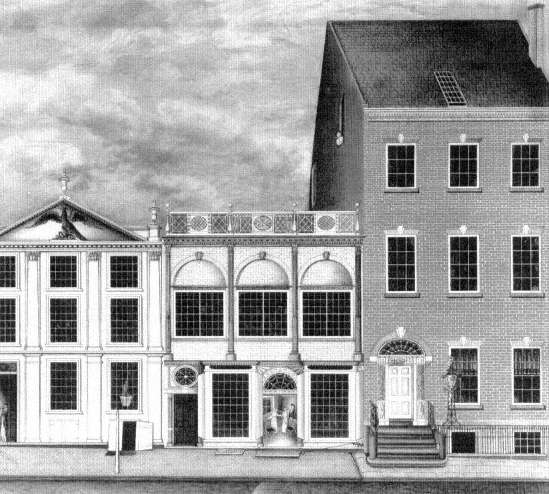

26. 168-172 Fulton Street, New York, ca. 1820. The shop and warehouse of the famous furniture maker Duncan Phyfe. Typical small-scale enterprise of the first era of industrialization. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1922

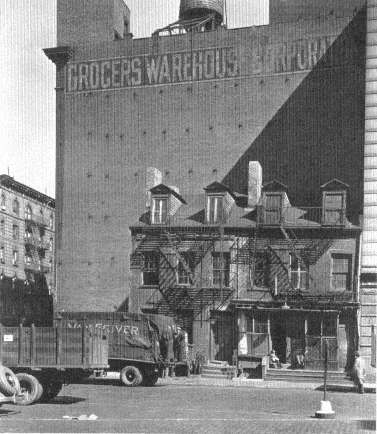

27. 512-514 Broome Street, New York, 1935. The photographer Berenice Abbott in her Changing New York recorded extremes of the big-city era; two old houses towered over by a six-story warehouse, the limit of construction before the steel-frame skyscraper of the industrial metropolis. Museum of the City of New York

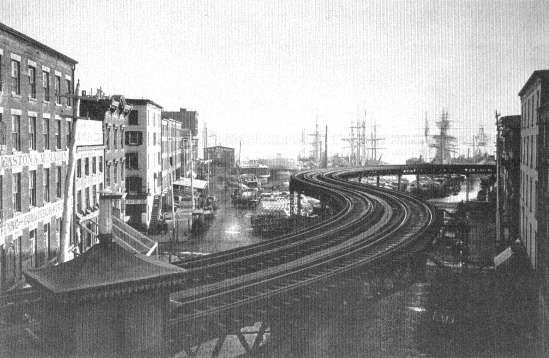

28. Coenties Slip, New York, ca. 1879. Three-to-four-story merchant warehouses and docks overshadowed by new elevated railway, whose high volume of traffic raised downtown land values until the traditional urban framework could no longer accommodate the enlarged scale of business enterprise. New-York Historical Society

29. Hudson Street, New York, ca. 1865. The big-city hive of small shops. New-York Historical Society

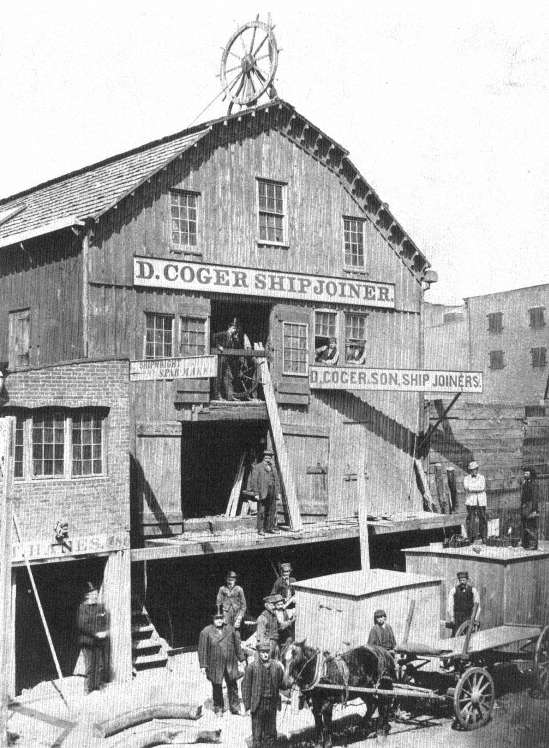

30. 480 Water Street, New York, ca. 1863. In the preindustrial era, barns and churches were the commonplace large structures. Here, a typical barnlike building serves as factory for a ship joiner making deckhouses. New-York Historical Society

31. Wall Street, New York, ca. 1878. A Sunday, presumably, at the heart of American finance, the small scale of early capitalist concentration. New-York Historical Society

Transportation

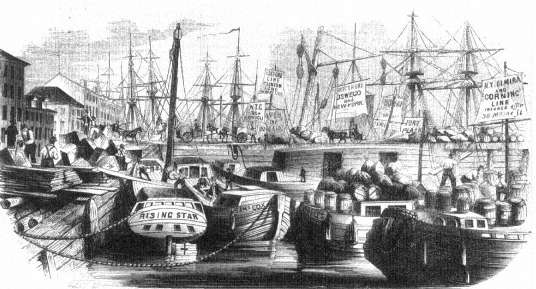

32. Coffee-House Slip, New York, 1830. Packet Lines offering abundant regulary scheduled sailings from New York to European and East Coast ports were a key to the city's mercantile supremacy. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

33. Canal Boats, New York, 1852. Before the organization of wholesale lumber districts and grain elevators, shippers and canal boats carried small lots of farm and forest products to regional trading centers for manufacture and processing. New-York Historical Society

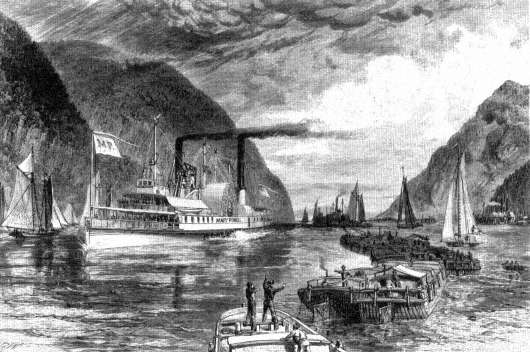

34. Highlands of the Hudson River, 1874. River artery of early industrial economy: sloops, schooners, canal boats under tow, the Albany-New York dayliner Mary Powell on the first New York thruway. New-York Historical Society

35. South Street, New York, 1880s. Square-riggers and small merchant warehouses, Atlantic links of the nation's first big city. New-York Historical Society

36. Grand Central Station at 42nd Street, New York, 1875. A deceptively small and elegant Paris-style hotel façade conceals the overarching power of the intercity railroad network. This new transportation system remade New York's economy into a national industrial metropolis, adding manufacturing to its established functions of finance and commerce. New-York Historical Society

37. Interior of Grand Central Station, New York, 1885. Such passenger train sheds were seen by contemporaries as symbols of the force of a new era. "What forces, what fates, slept in these bulks (great night trains lying on the tracks) which would soon be hurling themselves . . . through the night!" William Dean Howells, A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890). The French Impressionist Claude Monet painted seven scenes in and around Gare Saint-Lazare (1876-77), manifesting the same spirit. New-York Historical Society

38. General Motors Plant, Linden, New Jersey, 1967. Early nineteenth-century canal and railroad alignments permanently laid down the basic industrial skeleton of today's Northeastern megalopolis. Here, an auto assembly plant, fifteen miles from Manhattan along the old New York-Philadelphia transportation axis, U.S. Highway No. 1 (left) and Penn Central Railroad tracks (right). Regional Plan Association, Louis B. Schlivek

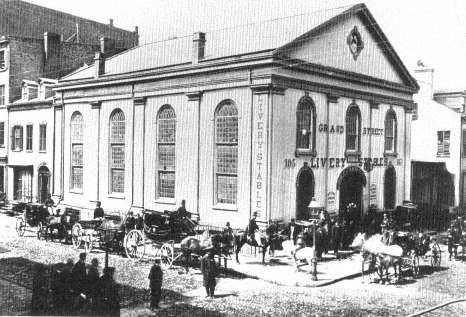

39. Grand Street Livery Stables, New York, 1865. The livery stable was the back-up transportation equivalent of today's truck and auto rental chains.

Their flies, manure, and smell were the bane of every neighborhood. New-York Historical Society

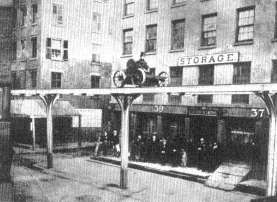

40. Greenwich Street Elevated, New York, 1867. Inventor of a cable-drawn engine, Charles T. Harvey, tries it out on the city's first el. New-York Historical Society

41. Greenwich Street Elevated at Ninth Avenue, New York, 1876. Typical American failure to adapt transportation innovations to the city's inherited framework. Here, old West Side working-class and industrial quarter is attacked by the new transit system. New-York Historical Society

15.

New York, 1849

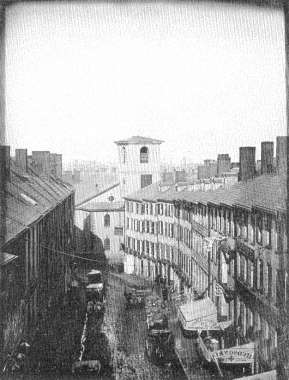

16.

Boston, 1855

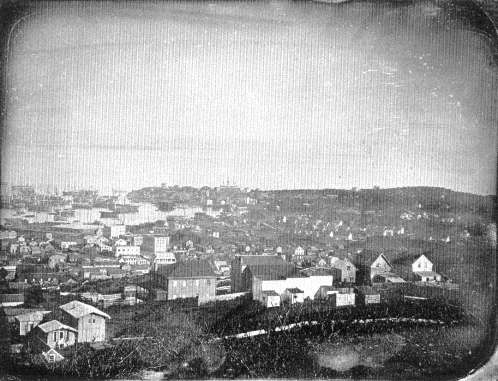

17.

San Francisco, 1850-51

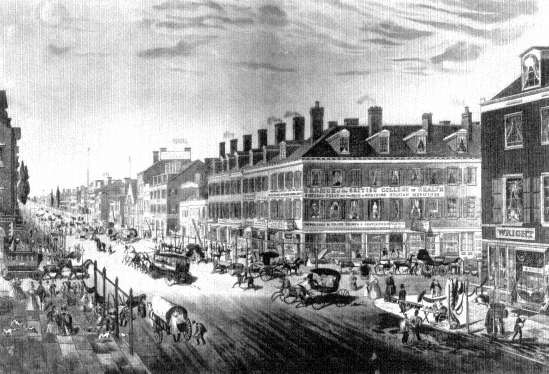

18.

Broadway, New York, 1834

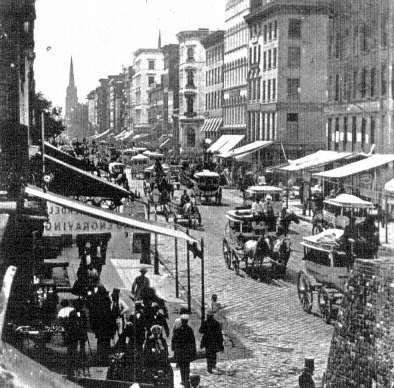

19.

Broadway, New York, 1870s

20.

Hudson Square, New York, 1866-67

21.

Fifth Avenue from 28th Street, New York, 1865

22.

Working-Class New York, Canal and Mott Streets, ca. 1870

23.

West Washington Market, New York, 1880s

24.

West 133rd Street, New York, ca. 1877

25.

Fifth Avenue, 116th and 117th Streets, New York, 1893

26.

168-172 Fulton Street, New York, ca. 1820

27.

512-514 Broome Street, New York, 1935

28.

Coenties Slip, New York, ca. 1879

29.

Hudson Street, New York, ca. 1865

30.

480 Water Street, New York, ca. 1863

31.

Wall Street, New York, ca. 1878

32.

Coffee-House Slip, New York, 1830

33.

Canal Boats, New York, 1852

34.

Highlands of the Hudson River, 1874

35.

South Street, New York, 1880s

36.

Grand Central Station, New York, 1875

37.

Interior of Grand Central Station, New York, 1885

38.

General Motors Plant, Linden, New Jersey, 1967

39.

Grand Street Livery Stables, New York. 1865

40.

Greenwich Street Elevated, New York, 1867

41.

Greenwich Street Elevated at Ninth Avenue, New York, 1876

none, he has friends in the village, and ere a year, Bill, Jo and Jim have been seduced off to New York.[21]

Unlike European countries of the time, the United States was an undeveloped land of bounteous resources which sustained a severe shortage of skilled labor. It offered high rewards to men who practiced a craft, and foreign-born artisans became leaders in many of the crafts in America. German immigrants predominated in New York in such diverse trades as sugar refining, the making of pianos and guns, and in lithography. Watchcase makers came from France and Switzerland, glass cutters from Ireland; ship riggers were Swedish, machinists British.

Urban production for a widening market also implied dependence upon a national and an international economy in a way that earlier artisans had never known. There were boom times, but there were also busts, panics, and depressions that caught all America and its London bankers short of orders, money, and credit. At such times wages might plummet 30 and 40 percent in a year's time. It has been estimated that a third of New York City's work force became unemployed in the panic of 1837. The depression in the winter of 1854-55 caused such widespread misery that a relief group claimed 195,000 men, women, and children were in want.[22] With every decade the cities burgeoned and intertwined more tightly with the rest of the United States and the world, so that each swing of depression meant longer breadlines, more evictions, more pervasive suffering.

The increase in the scale of production and the reach of markets started a long process of division into two classes within the urban labor force. The new discipline of urban work harassed and enticed Americans into a permanent acceptance of a social division between hand workers and pen wielders, operatives and clerks, the blue collar and the white. The pace of market growth was so fantastic that it impelled the enlargement of family shops and those with four or five employees to establishments with a dozen, fifty, even hundreds of workers. A number of results could be seen at once: the introduction of strict discipline and the systematic exploitation of women and children, the breakdown of

[21] . Walter Barrett (pseud. Joseph A. Scoville), The Old Merchants of New York City , New York, 1865, pp. 57-58. Note that this same spirit of youthful energy for moneymaking and success also characterizes the Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus in Upton Sinclair's anticapitalist novel The Jungle (New York, 1906).

[22] . Ernst, Immigrant Life , pp. 73-83.

complex craft skills into simple repetitive tasks, the drive for quantity by cutting piecework rates and by the introduction of machinery. Simultaneously a whole new class appeared—the well-to-do class of owners and partners who always enjoyed prosperity far beyond their employees and sometimes attained the undreamed-of wealth of a John Jacob Astor, a Peter Cooper, or a Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The widening gulf between classes by no means went unnoticed by contemporaries. From the first, workingmen of the largest cities protested the loss of control over their working lives, and to combat it they formed unions. In the 1820s and 1830s, early in the process of differentiation between boss and worker, some unions included masters and shopowners who sympathized with the men or were themselves oppressed by wholesale competition. The great Ten-Hour movement of the thirties appeared as a wave of enthusiastic strikes and parades and swept the Eastern coast cities. It sought relief from the unbroken sun-rise-to-sunset hours that had once been only seasonal or rush practices and asked for reduction in hours without reduction in pay.

It was the depression of 1837-39 that broke the power of the workingman and his new organizations. Subsequent hard times and panics, as well as the counterorganization of employers, attacked later revivals of unionism. Only a few highly skilled unions seemed able to establish themselves permanently, groups like the printers, cigar makers, iron molders, and the members of some of the building trades. Though the union movement as a countervailing force to business reorganization remained endemic throughout the nineteenth century, everything worked against it: the steady erosion of craft skills and the consequent weakening of the bargaining power of the men, the growing influx of foreign labor and the ceaseless coming and going of all working groups in a restless search for decent wages and better conditions, the competitive and exploitative use of women and children and untrained immigrants, and the expansion of business that put more and more wealth and political influence into the hands of employers in labor disputes. The same factors worked against the men's attempts to set up producers' cooperatives and other social experiments, while the working-class political parties were destroyed by competition with another social outgrowth of this era, the urban political machine. The machine could successfully undercut the labor parties by delivering jobs and opportunities to its faithful party workers at the same time that it was giving

verbal support to workers' platforms.[23] Indeed, it has long been one of the major functions of American politics to blur class conflicts in order to appeal to the broadest possible coalition of voters.[24]

The very fact that the early nineteenth-century trend toward widening social distinctions between working class and middle class was a reversal of former preindustrial tendencies made the process all the more painful. During and after the Revolution, the urban artisan had gained a growing measure of political participation and power. Jacksonian democracy rose on the momentum of these years, only to collapse as social conditions in factories, cities, and farms undermined its dependence on a vanishing social reality of independent artisans, shopkeepers, and farmers.

In the period between 1776 and 1820, America seemed to be moving toward a growing egalitarianism. In the old commercial cities of the time, cities of small shopkeepers and merchants, the lines between worker and owner were blurred despite an obvious coexistence of rich and poor and the prominence of families of long-standing privilege and influence. Then beginning in the 1820s, as business quickened and harsh methods spread, the benign trends reversed themselves and the inexorable advance of blue-collar-white-collar distinctions commenced. Despite the unions, parades, strikes, and political parties that centered on the workingman, the hand worker lost ground. He lost status, he lost assurance of employment, and he lost personal control over his work. Ensuing waves of frustration and anger broke over the city. All the big cities suffered epidemics of violence; there were labor riots, race riots, native-foreign riots, Catholic-Protestant riots, rich-poor riots.[25] New York City alone underwent a succession of riots, eight major and at least ten minor, between 1834 and 1871. The climax came in 1863 as a mixed class and race riot, begun in protest against the draft, exploded among the city's workingmen and poor Irish.

[23] . Commons, History of Labour , I, pp. 169-84; Norman Ware, The Industrial Worker 1840-1860 , Boston, 1924, pp. 18-70.

[24] . For example, the industrialist Peter Cooper, like many Americans of his time, mixed Jacksonian antibanker, popular democratic ideas with strong anti-foreign, anti-Catholic and staunch probusiness politics. See Robert P. Sharkey, Money. Class and Power, An Economic Study of Civil War and Reconstruction , Baltimore, 1959, pp. 276-84; and Edward C. Mack, Peter Cooper , New York, 1949, pp. 357-72.

[25] . Hugh B. Graham and Ted R. Gurr, Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives , New York, 1969, pp. 53-55.

Early in the morning men began to assemble here [on the West Side] m separate groups, as if in accordance with a previous arrangement, and at last moved quietly north along the various avenues. Women, also, like camp followers, took the same direction in crowds. . . . The factories and workshops were visited, and the men compelled to knock off work and join them, while the proprietors were threatened with the destruction of their property, if they made any opposition.

A ragged, coatless, heterogeneously weaponed army, it heaved tumultuously along Third Avenue. Tearing down the telegraph poles as it crossed the Harlem & New Haven Railroad track, it surged angrily up around the building where the drafting was going on. The small squad of police stationed there to repress disorder looked on bewildered, feeling they were powerless in the presence of such a host. Soon a stone went crashing through the window, which was a signal for a general assault on the doors. These giving way before the immense pressure, the foremost rushed in, followed by shouts and yells from those behind, and began to break up the furniture. The drafting officers, in an adjoining room, alarmed, fled precipitously through the rear of the building. The mob seized the wheel in which were the names, and what books, papers, and lists were left, and tore them up, and scattered them in every direction. A safe stood on one side, which was supposed to contain important papers, and on this they fell with clubs and stones, but in vain. Enraged at being thwarted, they set fire to the building, and hurried out of it. As the smoke began to ascend, the onlooking multitude without sent up a loud cheer.

The scene in Third Avenue at this time was fearful and appalling. It was now noon, but the hot July sun was obscured by heavy clouds, that hung in ominous shadows over the city, while from near Cooper Institute to Forty-sixth Street, or about thirty blocks, the avenue was black with human beings,—sidewalks, house-tops, windows, and stoops all filled with rioters or spectators. Dividing it like a stream, horse-cars arrested in their course lay strung along as far as the eye could reach. As the glance ran along this mighty mass of men and women north, it rested at length on huge columns of smoke rolling heavenward from burning buildings, giving a still more fearful aspect to the scene. Many estimated the number at this time in the street at fifty thousand.[26]

For four days mobs of workingmen and lower-class citizens broke into the stores and homes of the rich, beat and killed policemen, and fought pitched battles against the companies of police and militia. They broke into the armories, felled telegraph poles, and closed off streets by means of cobblestone barricades. The city police and the troops who were rushed back from Gettysburg quelled the riot but only after the city

[26] . Joel T. Headley, The Great Riots of New York: 1712-1873 , New York, 1873, reprint, Indianapolis, 1970, pp. 160-61, 164.

had suffered casualties estimated as high as two thousand killed and eight thousand injured. If the estimates are accurate, they would make the casualties of the New York Draft Riots equivalent to the losses at Shiloh or Bull Run.[27]

Unquestionably these riots, likened by contemporaries to the uprising in Europe in 1848 and later to the Paris Commune of 1871, frightened generations of wealthy Americans. The idea of a class war between worker and capitalist, though never widely adopted despite energetic Marxist indoctrination, became an indelible part of the thinking of the wealthy at least until the Second World War. But there was a more immediate and progressive consequence of the riots: the undertaking of a systematic investigation into urban living conditions.

What were these early big cities of America like?

They were a crowded jumble of small buildings organized as yet by only the most primitive specialization of land use. Imagine a city of half a million or even a million inhabitants in which church steeples stood out on the skyline and the masts and spars of ships at the wharves could be seen above the roofs of warehouses and factories. As yet there were no giant manufacturing lofts or skyscrapers to house offices and stores, partly because the techniques for erecting such structures had not been perfected but also because there was as yet no pressing need for them. The downtown office of the mid-nineteenth century consisted of one to three partners and a few clerks. The unique downtown institutions of this era were not skyscraper banks or corporate office towers but the Merchants' Exchange and the Stock Exchange, the settings for periodic gatherings of businessmen who met each day to transact their business together. A big daily newspaper office and plant, like Horace Greeley's Tribune , fitted on a downtown street in a modest five-story building, one of several in a row that made up the block. The factories in which the new discipline and new machines were being introduced were for the most part small affairs. They might be housed in a floor or two of an ancient narrow building belonging to a merchant, in a basement, in a rear-yard structure of one or two stories that resembled a barn, or perhaps, in some trades like the making of cigars or clothing, in the tenement room of the worker himself.

Capacious factories and shipyards did stand at the edge of the city, but the modest spatial demand of most business enterprises meant that

[27] . Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York, An Informal History of the Underworld , London, 1928, pp. 169-70.

they could be served by one or a few building lots. Accordingly, every part of the city contained shops and small factories. Let us look at New York's fashionable Washington Square as examined in detail after the Draft Riots. Doctor F. A. Burrell of 22 West Eleventh Street, who conducted the inspection, reported a population of 27,587 in the area (the Fifteenth Ward), occupying almost three thousand buildings: "The style of living of the population presents every variety from luxury to poverty, and almost every branch of industry is represented." There were in fact forty-eight factories, which turned out such products as pianos, cabinet furniture, trunks, sewing machines, chocolate, carriages, photographic materials, and hoopskirts, and there was one slaughterhouse and one soap and candle factory. The survey also identified 542 "stores" of all kinds and 234 "dram shops" (which we would now call bars), 23 "lager bier saloons," 17 gambling saloons, 7 concert saloons, 76 brothels, and 22 policy shops.[28] Hardly the modern bourgeois residential style.

For all its conglomeration of little buildings, the early big city was not a disorganized hodgepodge. It had an internal structure that held within the limitations of its day the potential for future elaboration. Those businesses which handled a considerable volume of goods, whether of trade or manufacture, huddled together next to the wharves because intracity freight transport was so arduous and expensive. Once the railroads, lake and coastwise schooners, river steamers, or canalboats had been loaded, they could take their freight cheaply from one city to the next, but within the city their cargoes had to move from warehouse to warehouse by handcarts or horse-drawn wagons. A special flavor pervaded the mixed downtown areas of the period. They were districts densely settled by unprepossessing offices and stores and factories of all kinds, and even by sugar refineries and slaughterhouses, side by side with the more genteel firms that dealt in banking, law, insurance, or cloth. In St. Louis, Philadelphia, or New York, commerce encircled the port and stood on the banks of the Mississippi, the Delaware, or the East and Hudson rivers.[29]

Surrounding this characteristically mixed downtown section were two types of neighborhood, the slums and the streets of fashion. As

[28] . Citizens' Association of New York, Report of the Council of Hygiene and Public Health upon the Sanitary Condition of the City , New York, 1865, pp. 132-45.

[29] . Leon Moses and Harold F. Williamson, "The Location of Economic Activities in Cities," American Economic Review , 57 (May 1967), 211-22.

housing aged and commercial uses made living in old core sections unpleasant, landlords converted private homes into rookeries for the poor, who crowded into the tiny new rooms or into attics and cellars to be near downtown jobs. In some cases a local neighborhood served as an industrial quarter on its own, given over to shoemaking or the garment trade. These were not the huge slums of later times; they were accommodations of a lower sort than ever existed again, but they were limited in extent. Most of the poor mingled instead with middle-class families by renting rooms and apartments all over the city. Even by 1870 the characteristic residential form of the American city was not yet that of a core of poverty and an outer rim of affluence.[30]

Just beyond downtown, a street or two would be filled with the homes of the wealthy. These were the merchants, manufacturers, doctors, and lawyers who could afford valuable land and who wished to enjoy the prominence and convenience of a central address. Beacon Hill in Boston, Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, and Washington Square in New York remain as reminders of the housing habits of the rich. These early sections also marked the axes of fashion for their cities, so that when later growth and a movement to the suburbs drove the wealthy and their followers uptown and beyond the city, their new homes advanced in the same general direction that had been plotted by their inner-city streets.[31]

Outside the slum streets and fashionable blocks stretched acre upon acre sheltering mingled commercial, industrial, and residential neighborhoods that have no counterpart in our own day. Boardinghouses stood beside prosperous homes, mill workers crowded around a suburban establishment like Peter Cooper's glueworks, while the owner's home stood alone across a field from the group. Another row of houses for downtown workers might stand a block away, and back lots were universally crammed with stables and blacksmith shops and lumber yards.

[30] . The mixed character of the city in this era is confirmed by the journey-to-work estimates of Pred, Spatial Dynamics , pp. 197-213, and by comparison of activities in a slum like the Sixth Ward to an upper East Side new district like Sanitary District 22, in Citizens' Association, Report of the Council of Hygiene , pp. 77-80, 275-77.

[31] . For a systematic confirmation of earlier studies of the clustering and migration of upper-income city dwellers, see Peter G. Goheen, Victorian Toronto, 1850-1900: Pattern and Process of Growth , Chicago, 1970, pp. 123, 146-47; also Walter Firey, Land Use in Central Boston , Cambridge, 1947, pp. 74-86; and E. Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen, The Making of a National Upper Class , Glencoe, 1958, pp. 174-77.

Baldwin's locomotive works in Philadelphia, a leading enterprise of the city, was a definition point for a fine mixed white-collar and blue-collar residential section.

If the criterion of urbanity is the mixture of classes and ethnic groups, in some cases including a mixture of blacks and whites, along with dense living and crowded streets and the omnipresence of all manner of business near the homes in every quarter, then the cities of the United States in the years between 1820 and 1870 marked the zenith of our national urbanity.