5. Robert-Houdin and the Vogue of the Automaton-Builders

| • | • | • |

§ 1. Predecessors of Robert-Houdin: Vaucanson, Jaquet-Droz, Kempelen, Maelzel

The vogue of the automaton-builders, that period when the public showed its greatest interest in automata and mechanicians built the most elaborate models, began with a contemporary of Philidor and ended with a contemporary of Liszt. The chronology of this chapter, therefore, retraces the chronology of the preceding four chapters, running from the middle of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. Like each of the preceding chapters, this chapter treats a new field of activity, but as it retraces the familiar chronology, familiar names reappear.

An automatic machine is a machine that “acts by itself,” that is, a machine that has its own engine as part of its machinery. If it also looks like an animal or a human being and acts like one, it is called an automaton. The more skilled the activity an automaton imitates, the more skilled must be the automaton-builder. In the preceding chapters, particularly in the immediately preceding one, we observed the prodigious progress of the cultivation of technical skill. We also heard complaints from critics of the cultivation of technical skill that its ultimate goal seemed to be to turn people into machines. When automaton-builders began to make mechanical imitations of skilled human beings, they were simultaneously demonstrating their own supreme technical skill as mechanicians and parodying the technical skill of those professionals whom their machines imitated. Thus, these automaton-builders pushed the cultivation of technical skill to the sublime and to the ridiculous at the same time, in a trick of deception.

The three automata built by Vaucanson. Courtesy of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress. Photograph by the Library of Congress Photoduplication Service.

[Full Size]

Automaton-builders began to make imitations of skilled human beings only late in the history of automata, during the period of their vogue that preceded their decline into near extinction, and it is no accident that this was the same period when magic shows, which often featured automata, also had their vogue. Automaton-building goes back to ancient times and down through the centuries has generally been associated with clockmaking. Ctesibius of second century B.C. Alexandria constructed water clocks and also water-powered automata. Water entering a sealed compartment beneath a carved figure of a bird, for example, forced the air in the compartment up through a tube inside the figure and across a sound hole to produce in the bird’s mouth something like a whistle. Sometime around the fourteenth century medieval craftsmen started to install weight-powered clocks on church towers. Shortly thereafter they added jaquemarts or “jacks-of-the-clock” or simply “jacks,” hammer-wielding human figures that pivoted to strike a large bell, marking the hour, and driven by the same weight that drove the clock. The Renaissance contributed spring-powered clocks and watches that gave the impulse to wind-up toy automata originating in the seventeenth century. Around 1730 one of the many clockmakers of the Black Forest in southwestern Germany, perhaps Franz-Anton Ketterer, had the idea of marking time’s progress with a mechanical cuckoo, in which he was much imitated. In fact, toward the middle of the eighteenth century the creative spirit began to reveal itself in makers of automata with increasing frequency. They constructed more complex works, which in appearance and action more closely resembled animals and humans, and which more and more often were independent of timekeeping. Some of the new artisans were no longer or had never been clockmakers. And some of their masterpieces were such as to entitle us to call the period from the middle of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century the “sixth day” in the Genesis of automata.[1]

| • | • | • |

The transcendent moment in the life of the mechanician Jacques Vaucanson (1709–1782) came in 1738 when he amazed the savants and the curious of Paris with a display of his three mechanical marvels, the Flûteur (Flute Player), the Canard (Duck), and the Tambourinaire (Drummer). The Flûteur, in its outward appearance, duplicated in wood an Antoine Coysevox marble sculpture, well known at the time, prominently displayed in the Tuileries Gardens, and representing a life-size faun sitting on a rock and playin-g a transverse flute. This kind of flute, similar to our present-day concert instrument, was something of a novelty in the first half of the eighteenth century, when what we call a recorder was still the standard concert flute. What was inside Vaucanson’s Flûteur was even more novel: a complicated arrangement of axles, cords, pulleys, levers, chains, bellows, pipes, and valves. When activated by his creator, the faun’s mechanical musculature caused his fingers to move up or down, uncovering or covering the airholes of the flute; his mouth to emit a stream of air, blowing with greater or lesser force across the mouth of the flute; his tongue to go up or down, interrupting the stream of air or allowing it to continue; and his lips to open or close or push out or pull back, forming different embouchures. The mechanician had perfectly harmonized all of these movements so that the Flûteur played the notes exactly as a human or faun flautist would. Because the transverse flute was still relatively unknown, little had been written concerning its technique, requiring Vaucanson, who was not a musician, to discover it for himself, for his satyric creation, and for future generations of flute teachers. The Flûteur played not just individual notes, of course, but whole pieces of music. “Indeed,” reported the Mercure de France,

In order to produce the successive notes of a piece, Vaucanson employed a rotating cylinder studded with pegs, each of which triggered a particular movement of the automaton’s anatomy. Such cylinders, on a larger scale, had been used in carillons and mechanical organs since the fifteenth century and, on a smaller scale, were to be used in music boxes from the late eighteenth century onward. The whole apparatus was driven by a weight, as clocks had been driven since the fourteenth century.[2]One has the pleasure of being able to listen to this mechanical figure for more than a quarter of an hour, as it performs like a master fourteen airs, each of them different in character, in range of notes, and in tempo.

Variations, so attractive on this instrument, have not been omitted, and everything, including crescendi, diminuendi, and even sustained notes, is executed with the most perfect good taste.

Vaucanson’s Canard, likewise life-size, raised itself up on its legs, flapped its feathered wings, moved its head from side to side, extended its neck, and quacked. It also dabbled realistically with its bill in water, drank, and took seed out of one’s hand. The mechanical viscera inside this automaton, however, heralded an advance in naturalism over that in the Flûteur. It produced an imitation not just of outward bodily movements but also of the processes of digestion. Shortly after swallowing food and water, the Canard expelled its waste with an authenticity that could only have been admired by the visitors to the exhibition hall.[3]

The third figure, the Tambourinaire, represented a shepherd of Provence playing two instruments indigenous to that region of southern France. With one hand, the shepherd beat a tambourin, or small drum, while with the other he held to his mouth a galoubet, a kind of small recorder, or old-style flute. In the exhibition prospectus, Vaucanson justified his construction and presentation of this second mechanical flute player:

At first glance one would imagine that the difficulties to overcome were less than in the Flûteur; but, without wanting to overrate the one at the expense of the other, I would ask the reader to recall that the instrument in question is among the most intractable and the most inherently out of tune; that it was necessary to give expression to a flute with only three holes, in which the holes are sometimes half-covered, and in which everything depends on the force of the air passing through them; that it was thus necessary to produce a variety of windspeeds, in such rapid succession that the ear can barely follow them, and to give tongue articulation to every note, even sixteenth-notes, without which this instrument has no appeal.[4]

Vaucanson’s automata struck a major chord with the public. After he had exhibited them in a rented hall in the Hôtel de Longueville, one long block south of the Café de la Régence, and perhaps at the annual Saint-Germain Fair on the Left Bank, he took them on a tour of France and Italy. A few years later, in 1743, he sold them to some entrepreneurs from Lyon, who toured with them for nearly a decade, showing them throughout Europe. Admission was always charged at these exhibitions and the automata appear to have brought in considerable revenue.[5]

They also brought recognition to Vaucanson from the scientific community. The Académie Royale des Sciences sent an official delegation to the exhibition hall and following the delegation’s report voted to award him a certificate of commendation. The Académie was not only a prestigious group of scientists but also a quasi-governmental body. Its coveted commendations frequently led to an official position or pension, as happened in Vaucanson’s case. To crown his success, King Louis XV also saw and admired his masterpieces.[6]

Thus, in 1740 Vaucanson was appointed inspector general of silk works, the silk industry being a logical place for him to put his mechanical talents to good use. Even though textile production in the eighteenth century was still labor-intensive, differences in technology already contributed significantly to differences in quality and efficiency, and because of its inferior machinery the French silk industry had fallen behind its English and Piedmontese rivals. Vaucanson spent the next forty years striving valiantly, but for the most part vainly, to help it catch up. He fulfilled his early promise of genius, inventing the first automatic loom (later perfected by Jacquard), the first automatic mechanism for weaving patterns, a new type of silk reeler and a new silk thrower (two machines involved in spinning silk thread), and a new calender (a kind of mangle to smooth finished cloth). But he lacked an attendant power of persuasion, and for a while the only thing he succeeded in conveying to either masters or workers in the French silk industry was that his machines threatened their livelihoods. The radically conservative canuts of Lyon, the industry’s capital, chased him out of their city in 1744 and probably would have killed him if they had been able to catch him. On the whole, the attempt he made to reform the silk industry proceeded very slowly and remained incomplete.[7]

But Vaucanson’s fame and fortune survived the vicissitudes of his career as inspector general. Voltaire praised him in his long poem Discours en vers sur l’homme (Discourse in Verse on Man, 1738):

Tandis que, d’une main stérilement vantée,La Mettrie also compared him to Prometheus in his landmark of materialist philosophy, L’Homme machine (Man a Machine, 1748). The Académie Royale des Sciences inducted him into its ranks in 1746 and frequently called upon him to pass judgment on the inventions of others. Jean-François Marmontel asked him to construct a mechanical asp for his play Cléopâtre (1750). The play was not a success, but the automaton was: Its hiss prompted a member of the audience to remark approvingly, “I agree with the asp.” [8]

Le hardi Vaucanson, rival de Prométhée,

Semblait, de la nature imitant les ressorts,

Prendre le feu des cieux pour animer les corps.

With a hand on which all praise falls sterile,

Vaucanson the bold, Prometheus’ rival,

Took, while imitating nature’s projects,

Heaven’s fire to animate cold objects.

The marquis de Condorcet’s official eulogy of Vaucanson to the Académie predicts that his name “will be famous for a long time.” At the time of his death in 1782, and for many years previous, his home had been the opulent Hôtel Mortagne on the outskirts of Paris, where he also had a large workshop. As Condorcet explained, “He believed that works useful to the nation should be paid for by it, and he used to say this frankly; if someone raised the objection that he already had a respectable fortune, he responded that others who did nothing useful were much better paid.” He bequeathed to the government the contents of his workshop: his inventions, including many unrelated to silk production; his drawings, such as one set representing the gearing for a differential; and his tools, some of which themselves were inventions. This collection was one of three gathered together during the Revolution to furnish the new Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers (Arts and Crafts Conservatory), still in existence today.[9]

In his ascent, Vaucanson never got entirely beyond the reach of the three automata he had constructed in his twenties. Condorcet’s prediction that his name “will be famous for a long time” concluded: “among the vulgar, for the ingenious productions that were his youthful amusements; among the enlightened, for the useful works that were his lifelong occupation.” And a friend, whose letter to the editor the Journal de Paris published as an obituary notice of Vaucanson, complained on behalf of his memory: “I was surprised to read, Messieurs, in a periodical dated 23 November, the strange and laconic eulogy of the late M. de Vaucanson. The editor had reduced it to this: ‘He immortalized himself through his automata.’ When one knows nothing else about a man so famous, one should limit oneself to giving the date of his death, and pass over the rest in silence.” It is clear that Vaucanson’s contemporaries regarded his automata as masterpieces, but whether they were early or mature masterpieces, and whether masterpieces of imagination or of craftsmanship or of learning, was debatable. In its report on their exhibition the Mercure de France referred equivocally to “this curious branch of mathematics.” [10] How did Vaucanson himself regard them?

There is evidence to suggest that when he began working on them he had something a little different in mind from what he eventually produced. While still a child in Grenoble he had constructed a clock, and, according to Condorcet, “some automaton-priests that duplicated a few of the ecclesiastical offices,” but his parents steered him toward more intellectual pursuits, sending him first to Lyon to study theology, then to Paris to study medicine. It was probably as a medical student that he discovered and became interested in anatomies mouvantes. “Moving anatomies” were working models of parts of the human body whose use many seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century physicians advocated for purposes of instruction and research. Some physiologists believed that if one constructed an accurate working model of a bodily organ, one could learn things about how the organ functioned in a living being by experimenting on the model. In the early 1730s, before he exhibited his soon-to-be-famous automata in Paris, Vaucanson showed one or two of them in the towns of Brittany and Normandy, together with “a machine containing several automata in which the natural functions of several animals are simulated through the action of fire, air, and water.” This oracular description appears in a contemporary contract and lacks further elaboration. In 1741, the year Vaucanson became involved with the silk industry, the Académie des Beaux-Arts of Lyon recorded in its minutes that “M. Vaucanson…informed the Académie of a project that he had conceived, to construct an automaton figure that simulated in its movements the animal functions, the circulation of the blood, respiration, digestion, the operation of muscles, tendons, nerves, etc.” In 1762, he began to work on the more modest project of a machine that would simulate just the circulation of the blood, using rubber tubes for veins. But this project, too, remained unrealized, because of inadequacies in contemporary rubber technology.[11]

Thus, Vaucanson may have originally conceived his celebrated automata as anatomies mouvantes. He borrowed heavily to fund his work on them. Persistent financial difficulties may have led him eventually to alter his course away from the purely scientific and toward something with greater popular appeal. The finished automata certainly had popular appeal, but their builder, in his exhibition prospectus, emphasized the science. The twenty-three-page prospectus began with five pages describing the physics of sound generation in the transverse flute. Apropos of the Provençal flute, the galoubet, he boasted, “I have also made discoveries that one would never have suspected.” For example: “The muscles of one’s chest make an effort equivalent to fifty-six pounds of pressure, since I had to produce this same force of air, that is, a stream of air pushed by this force or this pressure, in order to generate a high B, which is the highest note this instrument can reach.” Joining a debate among contemporary physiologists, Vaucanson explained of his Canard that “the food is digested there as it is in real animals, by means of dissolution and not by trituration, as some doctors claim.” [12] But as we have seen, for example in the remarks of Condorcet and in the attitude of the periodical press, Vaucanson’s own claim that his automata represented a contribution to science was only partly digestible.

| • | • | • |

The purpose of Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz (1752–1791) in constructing and exhibiting his three famous automata of the 1770s was frankly commercial.

His father, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, had already gained a small measure of fame as a master clockmaker in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, on the French border, where clockmaking, including watchmaking, had grown in the course of the eighteenth century to become the major industry. It was practiced throughout the canton but was concentrated particularly in the two principal towns, after the town of Neuchâtel itself, of Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds, where the elder Jaquet-Droz lived. Although in the third quarter of the century those two towns still contained only a few thousand inhabitants apiece, more than three hundred of them in Locle and more than four hundred in La Chaux-de-Fonds were clockmakers, and uncounted hundreds more were metalsmiths, jewelers, gilders, enamelers, engravers, cabinetmakers, and workers at other crafts tributary to the principal industry. Johann Bernoulli, astronomer at the Academy of King Frederick the Great of Prussia and a relative of the famous Bernoulli mathematicians who lived in Switzerland, visited Neuchâtel and reported that “every year in Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds combined, approximately 40,000 gold and silver watches are prepared for export, not counting a large quantity of plain and fancy clocks.” [13]

King Frederick was also prince of Neuchâtel, for Neuchâtel was under Prussian suzerainty from the early eighteenth century through the first half of the nineteenth. Frederick practiced the cosmopolitanism preached by the Enlightenment philosophes: He welcomed Philidor and his blindfold chess to Berlin; he invited Vaucanson, who declined, however, to join the many other foreigners at his academy; and he appointed an eccentric Scotsman governor of Neuchâtel in 1754. The Scotsman, likewise cosmopolitan, had been employed previously by the king of Spain, and he encouraged the elder Jaquet-Droz, furnishing him with letters of introduction and recommendation, to go to Madrid to offer some of his luxury clocks to Ferdinand VI, whose tastes we have already become acquainted with in the context of his patronage of the castrato Farinelli. Jaquet-Droz made the trip in 1758 and returned to Neuchâtel a year later with a small fortune and the beginnings of a continental, and eventually worldwide, reputation.[14]

The most elaborate clock bought by the Spanish king was described in detail by Bernoulli, who undoubtedly received the description from Jaquet-Droz himself when he visited the latter’s workshop; the piece is generally referred to as the Berger (Shepherd), because of the figure that surmounts it.

It should be explained that there were two windows in the housing of the clock below the dial: In one stood the mechanical lady holding a book of music in her hand; in the other was the canary, perched on the fist of a cupid. The largest figure, the shepherd, sat on top of the clock housing next to a tree; he actually played his recorder, his mouth blowing air into it, his fingers covering and uncovering the sound holes. At the feet of the shepherd two cupids oscillated on a small see-saw; and next to the shepherd, for good measure, sat a lamb that bleated and a dog that barked.[15] Style Louis XV.It indicates hours, minutes, and seconds, sounds the hours and quarter-hours, and will also rehearse as desired the hours and quarter-hours. In the middle of the clock face one sees these equivalent time measurements: the day of the year and month (taking into account the different lengths of the months); the phase of the moon; the sign of the zodiac, which appears at the time when the sun begins to traverse it; the season of the year; and an artificial sundial with an apparent shadow, that indicates the hours with the same irregularity as other sundials. Above this one sees the vault of the heavens, where the stars appear and disappear at the same time that they do in the sky.…A set of bells plays nine pieces…while a lady moves to the rhythm of the pieces.…After the bells play an artificial canary sings eight pieces…after which a shepherd plays various pieces on the flute.

Encouraged by this success, the elder Jaquet-Droz began to conceive more ambitious projects in which he would apply his mastery of clockwork to other purposes. We see from the description of the Berger that some of his luxury clocks were already sprouting mechanical figures and mechanical music devices. His new idea was to evolve these offshoots into autonomous entities. In 1769 Pierre Jaquet-Droz was joined by his seventeen-year-old son, Henri-Louis, just returned from two years’ study of mathematics and physics at Nancy. By 1773 they had constructed three androids—automata representing human beings, often in life size, and du-plicating one or more human functions—the Écrivain (Writer), the Dessinateur (Sketcher), and the Musicienne (Musician), as well as a piece four feet square called La Grotte (The Grotto), which contained a multitude of small mechanical figures, celestial, human, and animal. The exhibition prospectus credited the Écrivain to the father and the other three pieces to the son, but it seems likely that they were all to some degree creations of both of them.[16]

Here is how the prospectus described the Écrivain:

First Piece

A figure representing a child of two years, seated on a stool and writing at a desk.

This automaton moistens his pen himself [in an inkwell], shakes off the excess, and writes distinctly and correctly everything one cares to dictate to him, without anyone touching him either directly or indirectly. He places the capitals appropriately and leaves a suitable space between the words he writes. When he has completed one line, he moves on to the next, maintaining an appropriate distance between the lines. While he is writing, his eyes are fixed on his work; but as soon as he has finished a letter or a word, he glances at a writing primer, as if he wanted to imitate the model.

One could “program” the Écrivain ahead of time to write any message composed of up to forty letters and spaces. Or, more impressively, one could “dictate” to him messages of any length, selecting the letters for him to write one at a time. Programming the Écrivain necessitated opening up his body; dictation could be conducted from outside, apparently by means of a hidden wire or wires. The second piece, the Dessinateur, was quite similar to the Écrivain, likewise representing a two-year-old, but wielding a pencil instead of a pen, and producing only a very limited number of drawings in contrast to the limitless possibilities of the writer, who benefited from being able to combine at will the twenty-six letters of the alphabet.

It should be added that all the figures were carved, painted, dressed, and wigged so as to resemble human beings as closely as possible. Their machinery was hidden inside their bodies and could be accessed through a door built into their backs.[17]Third Piece

The third figure represents a girl of ten to twelve years, seated on a stool and playing a harpsichord.

This automaton, whose body, head, eyes, arms, hands, and fingers make various natural movements, performs on her harpsichord, by herself, various pieces of music in two or three parts, with considerable precision. Since her head has complete mobility, as do her eyes, she glances equally at her hands, at her music, and at her spectators; her flexible body bends forward from time to time in order to look more closely at her music; her breast alternately swells and falls, in order to show her breathing.

It is not clear whether or not the Jaquet-Drozes had planned initially to exhibit their androids. Quite possibly they had intended to follow the course the father had taken fifteen years earlier, that is, to offer their creations as luxury items to one or another of the crowned heads of Europe, preferably one with a taste for unique works of artifice and a treasury to match. But as word spread of their mechanical offspring, a steadily mounting stream of visitors arrived at their door asking to see them. This despite the fact that they lived in out-of-the-way La Chaux-de-Fonds, ten miles from Neuchâtel, not exactly a metropolis itself, in mountains of the Jura, and not on the road to any other capital. The governor of Neuchâtel, who happened to be in Berlin in the summer of 1774, received this account in a letter:

If it had not been before, the commercial potential of an exhibition was now obvious. Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz shepherded his young charges to Paris. Vaucanson saw the automata there and was extremely impressed, although he declined the offer of an explanation of how they worked; the venerable academician did not want to be lectured to by a twenty-two-year-old. Jaquet-Droz was invited to court, where his Dessinateur sketched the portraits of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. Later that same year, 1775, the automata traveled to London, whence they embarked on a tour of Europe, revisiting Paris many times and finally returning to Switzerland about a decade after their departure. In 1789 they were sold to some French speculators.[18]People came from everywhere, as though on a pilgrimage. Every day the yard and the road were filled with carriages; the rains deterred very few of them. It began at six o’clock in the morning and lasted until eight in the evening. The Jaquet-Drozes, aided by two of their workers, took turns presenting the automata. Among those parading through were the nobility of the surrounding lands and the bailiffs of the cantons with their families; the ambassador of France himself went there incognito.

The fortunes of the Jaquet-Droz family imitated the fortunes of the mechanical family. Requests for products came to the creators after requests for demonstrations came to the world’s most sophisticated creatures; the renown of the progenitors followed on the heels of the renown of the progeny; the gains of the artisans reflected the gains of the little artists. The Jaquet-Drozes established ateliers in Geneva and London to supplement the output of their original workshop in La Chaux-de-Fonds. The son revolved regularly from one to the next. He also communicated directly with agents scattered around the globe eager to participate in his family’s business, and sent things to them in Paris, Madrid, Constantinople, and Canton.[19]

The Jaquet-Drozes designed, constructed, and sold luxury goods. Commercially, they were to the late eighteenth century what Benvenuto Cellini had been to the sixteenth century and what Carl Fabergé was to be to the turn of the twentieth century; artistically, they were perhaps a notch below those two master craftsmen. They produced “admirable watches, snuff-boxes, toiletry boxes, and decanters, leaved with gold, ornamented with precious gems and pearls, and concealing in their interiors small automata with incredibly tiny mechanisms; wonderful birds which even today spring up out of their boxes and sing their sweet melodies; richly decorated clocks with the most unexpected complexities, astronomical timepieces of real scientific value.” [20]

Among their products, then, some were essentially frivolous, some combined the ornamental with the practical, and some, such as artificial limbs, had great utility. Probably the most celebrated of these were the hands fabricated for Grimod de La Reynière, the gastronome whose Jury Dégustateur awarded certificates of commendation for culinary concoctions in imitation of the certificates awarded by the Académie Royale des Sciences for inventions. Grimod had been born with deformed hands that were almost totally dysfunctional, but fortunately his family was wealthy. The artificial hands designed by the younger Jaquet-Droz while he was in Paris in 1775, and then constructed by his craftsmen, allowed Grimod to lead a normal life. Vaucanson saw this new mechanical masterpiece of the Swiss artisan and reportedly said to him, “Young man, you start where I would like to finish.” [21]

It does not appear that the Jaquet-Drozes ever mounted another exhibition or took any of their creations on tour again. Even on that unique tour, the younger Jaquet-Droz only accompanied the androids as far as Paris and London, at that point leaving them in the hands of several of the family’s employees for the rest of their long journey. But the Jaquet-Drozes did construct at least four more androids in the 1780s when their fortunes were climbing toward the heavens. They made two replicas of the Musicienne, one of which played sixteen or eighteen pieces instead of just five as the first one had. And they made two combination Écrivains-Dessinateurs, that is, two androids each of which both wrote and sketched. His Celestial Majesty the Emperor of China bought one of them and perhaps one of the Musicienne replicas as well.[22]

The construction of androids must have presented a challenge to the skill and ingenuity of the Jaquet-Drozes, and it brought them a renown that did not seem to be unwelcome. But it was above all a commercial venture. It wound up their family business to spirited activity in the 1770s and 1780s, with orders for their expensive luxuries coming in from courts all over Europe and beyond, driving an expansion of their operations. In 1789, however, around the time they sold their last android, the mechanisms of commerce came unsprung. They had advanced too much credit to their agents and associates and were forced to liquidate a large portion of their holdings to cover their debts. Pierre Jaquet-Droz died a year later; his son Henri-Louis, the following year at the age of thirty-nine.[23]

| • | • | • |

Vaucanson and the Jaquet-Drozes inspired many imitations of their imitations of animals and humans engaged in characteristic activities. That is, the success of their exhibitions of their automata encouraged others to build and exhibit similar automata. While neither Vaucanson nor the Jaquet-Drozes were in the first instance showmen, many of their imitators were.

In 1746 a mechanician named Defrance exhibited at the Tuileries several automaton flute players and mechanical birds of his making, the latter of which, he announced in the Affiches de Paris (Paris Advertiser), “sang several airs with a marvelous delicacy.” A sculptor-physicist named Lagrelet acquired them subsequently and presented them in 1750 at the Saint-Germain Fair on the Left Bank, advertising with a more detailed description,

Among the entertainments offered by the Palais Magique in 1748 were three automata: a peasant woman with a pigeon on her head that rendered red or white wine as desired through its beak into a glass presented by the woman; a grocer seated at his counter who got up to fetch merchandise requested of him; and a Moor who played a tune by striking a bell with a hammer. It was probably in the 1750s that the inventor Abbé Mical, who two decades later was to exhibit to much acclaim a pair of mechanical talking heads, constructed two mechanical flute players he called Annette and Lubin. He was reported to have followed this up with “an entire orchestra in which the figures, large as life, played music from morning till evening; and those who have seen it attest to the superiority of this work over everything else of the sort that has appeared. It would, by virtue of its size, the beauty of its sculptured figures, and the perfection of its highly varied execution, grace the largest hall.” Friedrich von Knauss, working in Vienna in the 1750s, built a mechanical musician that played the flageolet, a kind of recorder, and, before the Jaquet-Drozes built their Écrivain, a series of four automaton writers. The latter, however, were much smaller than life-size and did not attempt to imitate the motions of a human being in the act of writing, aspiring only to produce a good script, which they did. Knauss had a prestigious post as K.-K. Hofmechaniker (Imperial and Royal Court Mechanician) and does not seem to have presented any of his works to the public. Returning to Paris, we find that another ensemble of automaton musicians was exhibited around 1770 by Robert Richard, whose Concert Mécanique consisted of a harpsichord player, a violinist, and a cellist. At the turn of the nineteenth century François Pelletier had a small science museum containing an automaton that played the galoubet and the tambourin.[24]two life-size figures representing a shepherd and a shepherdess playing thirteen different airs in two parts on the transverse flute. The shepherd beats time with his feet; both figures move their lips, through which passes the variable-strength wind that they blow into their flutes, producing the notes; they provide articulation and rhythm by using their tongues and by altering the positions of their fingers on the flute, just as living persons do; they are accompanied by several birds that add their chirping to the little concert.

The foregoing all seem to have been more or less, directly or indirectly, inspired by Vaucanson. Others, beginning in the 1780s, clearly followed the example of the Jaquet-Drozes. Like the latter, the Maillardets were a family of talented clockmakers, and for a while they also worked in La Chaux-de-Fonds. In fact, the two families worked together on some projects, and the atelier that the Jaquet-Drozes established in London in 1774 became in 1783 the atelier Jacquet-Droz-Maillardet. This atelier, under the direction of Henri Maillardet, completed the two Jaquet-Droz Écrivain-Dessinateurs (Writer-Sketchers) and at least one of the two replica Musiciennes, projects that had been started in Switzerland. It is possible that Henri Maillardet also made a third Écrivain-Dessinateur and another Musicienne, for two such pieces ascribed to him alone formed part of an exhibition of automata that he and an impresario mounted in London at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The exhibition had in addition a small automaton rope-dancer and a small automaton magician that displayed the appropriate answer to a question chosen by a spectator from among a prepared set. The group passed through the hands of one impresario after another and continued to be shown intermittently until at least 1833. In the 1840s in La Chaux-de-Fonds, two later Maillardets presented some of the automata made by members of their family; they had no Écrivain-Dessinateurs or Musiciennes but they did have one of the magicians, for there were several of these too. Meanwhile, in China, a French missionary constructed for the emperor a replica of the Jaquet-Droz Écrivain-Dessinateur that had been sent there. Both could write Chinese.[25]

Another mechanical masterpiece made in the 1780s was the Joueuse de Tympanon (Dulcimer Player) of David Roentgen and Pierre Kintzing. The mechanism in this two-foot-high musician who actually played the dulcimer, striking its strings with hammers she held in her hands, was similar to that in the Jaquet-Droz Musiciennes, whose fingers really depressed the keys of their instruments. And she too moved her head and eyes in a lifelike manner. The Joueuse de Tympanon had a repertoire of eight tunes. Her creators were craftsmen whose secluded atelier lay in a tiny principality on the lower Rhine, but they were well known in the world at large. In fact, Roentgen held the title of Ébeniste-Mécanicien de la Reine de France (Cabinetmaker-Mechanician to the queen of France). Perhaps Marie-Antoinette thought of commissioning the Joueuse de Tym-panon from him after seeing the original Jaquet-Droz Musicienne in 1775. In any case, the commission was executed and when the queen had enjoyed the piece sufficiently she offered her to the Académie Royale des Sciences for examination and inclusion in its collection. After the Revolution, together with much of the rest of the Académie’s collection and the contents of Vaucanson’s workshop, the piece ended up in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers.[26]

One did not have to be quite a queen to own canaries in France in the eighteenth century, but they were luxury items. They had to be imported, as their name suggests, from the Canary Islands. Among the birds’ attractions was their ability to learn new songs. It could be taxing for an owner, however, to play a tune over and over on a flageolet—the usual mode of teaching—until a canary learned it. This led to the invention of the flageolet organisé, or organ-ized flageolet, an instrument with a keyboard and bellows that one could play, and before that, learn to play, more easily than the ordinary flageolet. To teach one how to teach one’s pet, J.-C. Hervieux de Chanteloup wrote his Nouveau traité des serins de Canarie (New Treatise on Canaries from the Canaries), which first appeared in 1705 and went through more than a dozen editions before the end of the century.[27]

Around mid-century there appeared a new labor-saving device for canary owners called the serinette (little canary). The serinette was a small table-top machine with a crank that one had only to turn to play popular melodies for the songbird to imitate. This saved its owner from having to learn anything, if not quite from having to do anything. The early serinettes were relatively simple even in eighteenth-century terms, relying on miniature organ pipes or small whistles to produce the notes.

Mechanicians, therefore, did not find them very interesting to make. Furthermore, the focus of attention in the whole affair remained the canary; the performance was given by the canary; the artist was the canary. But this subhuman competitor might be eliminated by applying a little ingenuity to the new invention. After all, Black Forest craftsmen had been building cuckoo clocks since the 1730s. Any reasonable clockmaker could replace the serinette’s crank with a wind-up mechanism. Any reasonable sculptor could duplicate the appearance of a canary or other avian species, and certain mechanicians could duplicate the natural staccato movements of a bird’s head, beak, wings, and tail. For the song, one could use instead of a set of pipes a single pipe with a sliding piston and a valve, which occupied less space, produced just as wide a range of notes, and in addition reproduced the roulades, trills, and tremolos that made birdsong particularly attractive. One could do this, all this, and put it into production, if one were named Jaquet-Droz.

Beginning in the late 1770s or early 1780s, the Jaquet-Droz ateliers constructed hundreds of wobbling warblers, popping up out of clocks, snuffboxes, and decanters, and, most spectacularly, hopping from perch to perch inside of proverbial, but absolutely literal, gilded cages. Birds of a feather, the Maillardets flew after them into this branch of the trade as well, and continued to produce such luxury pieces until they fell out of fashion, around 1840. So did quite a few other master craftsmen, for there were many more imitators of the Jaquet-Drozes’ line of singing and dancing canaries, nightingales, finches, and hummingbirds than of their line of androids.[28]

Of course, the one was much easier to duplicate than the other. In the avian pieces, the mechanical singing bird did not actually contain the singing mechanism. This was located elsewhere in the piece, in a compartment in the snuffbox or decanter or clock separate from the compartment out of which the bird sprang. The body of the bird contained the mechanism that effected its movements but not its song. Furthermore, the singing mechanism only imitated the sounds of a bird singing, not the bird’s own manner of producing these sounds. By contrast, the Jaquet-Droz Musiciennes, like the Flûteur and the Tambourinaire of Vaucanson and the Joueuse de Tympanon of Roentgen and Kintzing, produced music by actually playing an instrument in the manner of a human being. Thus, the Jaquet-Droz singing birds were only quasi-automaton musicians, while their keyboard-playing androids were true automaton musicians, requiring greater mechanical skill to produce. Similarly, the writing automata of Knauss, which produced a fine script but did not reproduce the motions of a human being in the act of writing, were quasi-automaton writers, while the Jaquet-Droz Écrivain, which did both of these things, was a true automaton writer.[29]

Many of the pieces exhibited in the eighteenth century as automaton musicians should be categorized as quasi-automaton musicians rather than true automaton musicians. That is, they consisted of a representational sculpture that gestured automatically and a music machine that played automatically, but there was no organic connection between the two. We can be reasonably certain that Richard’s Concert Mécanique was of this sort: The right arms of his violinist and his cellist may have drawn real bows, but it is unlikely that their real bows drew real music from the strings of real instruments. The same might have been the case for Abbé Mical’s mechanical orchestra, although one source indicates that it was an ensemble of flutes rather than an orchestra, in which case he might “simply” have made many copies of Vaucanson’s mechanism or one of his own and thereby produced a true automaton concert.[30]

And many of the pieces exhibited in the eighteenth century as automaton writers or sketchers should not be counted as automata at all. They were articulated sculptures of human beings whose hands grasped a pen or pencil and traced words or drawings, but they were activated and guided by a human being. That human being, the real writer, hid behind the wall or beneath the floor against which rested the pseudo-automaton. The wood-and-wire figure wrote exactly what his flesh-and-blood counterpart did, their two pens being connected by a simple mechanical contrivance called a pantograph, the levers of which were concealed in the body of the sculpture.[31]

It was logical that some of the imitations of the imitation animals and humans of Vaucanson and the Jaquet-Drozes would turn out to be fake imitations. For the makers of these pseudo-automata were not endeavoring to imitate the actions of living beings with machinery, as Vaucanson and the Jaquet-Drozes had done, but rather to imitate in turn the machinery that imitated the actions of living beings. Given what this machinery did, the natural short cut for those endeavoring to imitate it was to employ living beings. The makers of pseudo-automata were more exhibitors than builders, since their purpose in making imitations was not to demonstrate their expertise in science or technology, expertise they often did not have, but merely to put on a good show.

| • | • | • |

Many late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Europeans knew of Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734–1804) as a mechanician employed at the Court of the Holy Roman Empire in Vienna. He was this in fact and perhaps also in spirit, but not in name or in substance. For he did not hold the title of K.-K. Hofmechaniker—Knauss had that—but the title of K.-K. Hofrat (Imperial and Royal Court Councillor) and his principal occupation consisted of helping to administer the Hungarian portion of the polyglot Hapsburg empire. Equally polyglot himself, Kempelen spoke Latin, German, Magyar, French, Italian, English, Romanian, and one or more Slavic languages. His official duties included such things as translating Empress Maria Theresa’s legal code from Latin into German, supervising the operation of the Hungarian salt mines, directing the construction of a royal palace in Ofen (now Budapest), and organizing a campaign against brigandage in Hungary. When he was not engaged in state business he was likely to be writing drama or poetry or painting landscapes. In his spare time he was a mechanician.[32]

Nevertheless, despite Kempelen’s status as a senior official in the Hungarian government, despite the production of his plays at the Hoftheater (Court Theater), and despite his membership in the Akademie Bildender Künstler (Academy of Pictorial Artists), the substantial fame that descended upon him in the 1780s and what little of it that has survived came to him through his mechanical inventions.

His potentially very useful printing press for the blind gained him little attention. The eighteenth century saw the beginnings of mass literacy in Western Europe, but the blind were left behind. Touched in particular by the plight of a sightless musician of his acquaintance who had already devised a system of musical notation for herself, Kempelen designed a press that printed German Fraktur type in relief and had it built for her.[33] Louis Braille did not develop his more efficient system of patterns of raised dots until 1829.

Kempelen’s civil engineering projects contributed more to the advancement of his career than to making his name known in the wider world. Ever since the Renaissance, European princes great and small had adorned their palace grounds with fountains, engaging in a low-pressure competition in which each sought to dampen the splendor of his rivals by making his own jets and cascades more impressive than theirs. Kempelen stepped into a waterfall project on the grounds of the palace at Schönbrunn (pretty spring), the Austrian monarchy’s response to Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles, and devised a recycling apparatus for it. The falling water turned a wheel, which drove pumps that returned the fallen water back to the top of the falls. A contemporary praised the system to the skies, calling it “one of the most important and extraordinary inventions of this century” and describing it as if it were a kind of perpetual motion machine.

Kempelen also tinkered with the new steam engine, known to his compatriots as the englische Feuermaschine (English fire machine). He constructed one that was used successfully to help dig canals in Hungary. He constructed another, it was reported, that he “started up, and it did what K. intended it to do, but only for a few minutes, and then broke down or exploded, which sounds a bit like a fairy tale.”

In 1769 there appeared in Vienna a Frenchman named Pelletier, probably the same Pelletier who later in Paris operated a small museum of scientific curiosities containing an automaton galoubet player. He performed before the Imperial and Royal Court some tricks that depended on magnetism, which seem to have impressed Empress Maria Theresa but not Kempelen, who was also present. Kempelen boasted to the empress that he could create something far more impressive, and she encouraged him to do so. Six months later he produced his Chess Player.[34]

The Chess Player was a life-size sculpture of a man dressed as a Turk, or at least as the Western stereotype of a Turk, complete with turban, drooping moustache, and flowing robe, and holding in his left hand a two-foot-long pipe. He sat in permanence behind a cabinet approximately four feet wide, two and a half feet deep, and three feet high, which rested on four casters and had a chessboard fixed to the top. The side of the cabinet facing the spectators had built into it at the bottom a shallow drawer that was almost as wide as the cabinet itself, and above the drawer two doors of equal height but of unequal width, corresponding to a larger compartment on the right and a smaller one on the left; on the opposite, that is the Turk’s, side of the cabinet, there were two more doors, one to his right and one to his left. Kempelen developed a ritual of presentation: He wheeled the Turk-and-cabinet into the room; opened and closed the doors of the cabinet in turn, showing that the smaller compartment contained a mass of machinery while the larger compartment contained much less of it; pulled out the drawer, extracted a set of chessmen and a cushion, and pushed it in again; wheeled the cabinet around, lifted the robe of the Turk to reveal the machinery in his incompletely enclosed body and wheeled the cabinet back again; removed the pipe from the Turk’s playing hand, placed the cushion under that hand’s arm, and set up the chessmen.[35]

Like a spring-driven clock, the Chess Player’s mechanism had to be periodically wound up, after which it functioned by itself. The Turk raised his arm, extended it over the board, grasped a piece with his hand, and moved it to a new square. He waited for his opponent to move before moving again, nodded his head twice to indicate a check to his opponent’s queen, three times for a check to the king, and shook his head when his opponent made an illegal move. He always played first and usually won. Sometimes when he closed his hand while reaching for a piece he failed to grasp it, if it was not precisely in the middle of the square, but he moved his arm anyway as if he held it, opening his hand again over the destination square. In such cases the Turk’s intention was clear and Kempelen intervened to move the piece. Otherwise the creator kept himself stationed several paces away, standing at a little side table and looking secretively into a small box placed there, except when he had to rewind the machinery.

The empress congratulated him on making good on his boast, and the entire court expressed its admiration. Kempelen first began to show the Chess Player in Vienna and then at his home in Pressburg (now Bratislava), attracting a certain amount of attention, in 1769. Several newspapers, including the Mercure de France, ran reports, and several speculators wanted to buy the piece. Kempelen judged his own creation as “not without merit as regards the mechanism, the effects of which, however, appear so marvelous only because of the boldness of the conception and because of the fortuitous choice of means that are used to create the illusion.” [36] His interest in it gradually declined, and after a few years of increasingly infrequent exhibitions he partially disassembled it and put it into storage.

The piece that he considered his masterpiece, or at least his greatest contribution to knowledge, was his speaking machine. Curiously, three mechanicians working independently constructed speaking machines almost simultaneously: Kempelen in 1778, a Kratzenstein of Copenhagen in 1780, and Abbé Mical in 1778. Mical, the same Parisian who had previously built automaton flute players, gave his two speaking machines human form, or, to be exact, heads. These talking heads alternately spoke several sentences flattering to the king in clearly comprehensible French. The royalist journalist Antoine Rivarol heaped praise on them. He argued that the proliferation of such heads would preserve the perfect spoken French of the eighteenth century for all time and prevent its degradation by epigones. When Kempelen brought his speaking machine to Paris in 1783, Rivarol reported, “M. Kempelen also had a box from which a few words escaped, it is said; but this worthy traveler paid true homage to M. the Abbé Mical: As soon as he learned of the talking heads, he withdrew.” Another Paris observer, however, judged the talking heads inferior: “Their pronunciation is not by some distance as clear, as distinct, as that of M. de Kempelen’s machine.” Kempelen, too, had planned to bestow a head on his speaking machine, but it seems always to have remained a bare assembly of wires, hinges, tubes, reeds, funnels, and bellows, sometimes covered with a cloth. He was able to make it say several hundred individual words and a few whole sentences. Kempelen’s anatomie mouvante formed a part of his linguistic researches, the results of which he published in a book entitled Wolfgangs von Kempelen Mechanismus der menschlichen Sprache nebst der Beschreibung seiner sprechenden Maschine (Wolfgang von Kempelen’s Mechanism of Human Speech Together with a Description of His Speaking Machine, 1791). His twofold aim was to identify the phonemes of the European languages and to determine how human beings produce those sounds, by specifying the contributions of the lungs, windpipe, vocal cords, glottis, nose, tongue, teeth, lips, etc.[37]

In 1782, while still occupied with his speaking machine, at least in the intervals between his official responsibilities and his artistic relaxations, Kempelen was induced by Emperor Joseph II to resuscitate his Chess Player. The absolute monarch of Austria was expecting a visit from the next absolute monarch of Russia and his wife and wanted to prevent their boredom from becoming absolute. The Turk enchanted the foreign dignitaries to such a degree that they insisted his maker take him on a tour of Europe and prevailed upon Emperor Joseph to decree a leave of absence. The obedient Kempelen accompanied both Chess Player and speaking machine to Paris.

A pamphlet first published in German in 1783 heralded the start of the Turk’s tour that same year; French, English, and Dutch editions of 1783, 1784, and 1785, respectively, marked his triumphal progress. Written by a friend of Kempelen, the pamphlet described what the Turk did, how Kempelen came to create him, and gave a sketch of his life. Thus spurted the first few drops of what was to become a recycling fountain of ink, lasting well into the nineteenth century and staining a multitude of private and public letters, newspaper and magazine articles, and opuscules of every sort, all devoted to explaining the secret of the Turk’s abilities, a secret known to almost none of the authors.[38]

Hence when the Turk arrived in Paris, his first destination, the literate public was already well informed about him. As for the Turk, he knew enough to find his way to the Café de la Régence. The attorney Bernard, who was to become Philidor’s successor as champion and already a leading player, defeated the Turk after a long and difficult game. Bernard rated his skill equal to that of the marquis de Ximenès, at which the latter took offense, not liking to be compared to a literal blockhead. Philidor also defeated the Turk, at an exhibition in front of the Académie Royale des Sciences. Kempelen is reported to have approached the champion beforehand in private to ask him to let the Turk win, so as not to jeopardize the success of the tour. Philidor agreed in principle but told Kempelen that it was in both their interests that he maintain a certain level of play; otherwise, suspicions would be aroused. The consensus of the spectators was that Philidor won in spite of playing below his usual level. He often said afterward that this game had fatigued him more than any other.[39]

The Turk enjoyed Paris in the spring of 1783 and then crossed to London in the late summer or fall. The recent revelation that he was not a player of the top rank did not seem to affect his reputation or his ability to attract attention. Returning to the continent in 1784, he gave exhibitions in Leipzig, Dresden, several towns in southern Germany, Amsterdam, and probably many other places. He retired to Pressburg in 1785, while the letters, articles, and pamphlets continued to gush forth unabated.[40]

After having extended a leave of six months into two years, Kempelen returned to government service and worked until 1798, when he too retired. But he did not cease to set up his easel in the countryside and paint landscapes, since he continued to be able to see perfectly without glasses. He died in 1804 at the age of seventy without having let the world see the secret of his Chess Player.

The purposes behind Kempelen’s mechanical inventions seem to have been almost as various as the inventions themselves. Simple benevolence undoubtedly motivated in large part his invention of type for the blind. The speaking machine grew out of his interest in linguistics, and he intended it to be a contribution to science. The personal satisfaction of meeting challenges to his ingenuity probably also encouraged him in both projects. His adaptation of the steam engine was done for the utilitarian, even mundane purpose of digging canals. His purpose in this case was the government’s, or the monarchy’s, which was appropriate to him as a royal servant. The recycling waterfall of Schönbrunn he likewise conceived in his role as servant of the monarchy. The Chess Player as well he invented to impress his sovereign, and its accomplishment of that aim was what brought about its tour of Europe, its fame, and his.

| • | • | • |

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (1772–1838) spent his life inventing and reproducing and acquiring machines that facilitated or imitated or simulated great human skill, and exhibiting his machines.[41]

Maelzel was born and grew up in Regensburg, the imperial city on the Danube where the Holy Roman Emperors were elected. His father taught him how to build organs, read music, and play the piano. By the age of fourteen he had gained a reputation as the best pianist in town. After giving piano lessons for a few years there, he headed downriver to Vienna, the imperial city where the Holy Roman Emperors resided, but for unknown reasons turned his attention back from making music to making music-makers. In 1805 he completed a gigantic organ-like instrument of his own invention that he called a Panharmonicon. This machine incorporated a large variety of orchestral instruments, woodwinds, brass, percussion, but no strings, simulating an ensemble of forty-odd musicians, which a system of levers animated and into which a system of bellows breathed life. Each individual instrument could play only a single note, so that in order to be able to play a whole trumpet passage, for example, the machine contained eight trumpets. The Panharmonicon played at all dynamic levels, from a primal explosion to a dying breeze, and reproduced much of the symphonic universe. Its creator programmed it in advance rather than actively manipulating it while it played. For this purpose, he equipped it with the same sort of rotating pegged cylinder that carillons and music boxes had.[42]

Maelzel set out on tour with his recently built Panharmonicon and his recently bought Chess Player, which he acquired from Kempelen’s son soon after the latter had inherited it. In 1807 he arrived in Paris for an extended sojourn. There the expatriate Italian composer Cherubini received the Panharmonicon more sympathetically than he was to receive young Franz Liszt a few years later, going so far as to write expressly for the machine a piece of music, “The Echo.” Maelzel sold his creation for the large sum of sixty thousand francs so that he could immediately begin work on a new, improved model, which he quickly completed. He also constructed at about the same time a life-size automaton trumpeter, perhaps the first true automaton musician to play this instrument, with moving lips and tongue and a variable volume of wind. He presented his Trompeter to Napoleon’s Société d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale, the organization that had staged the Expositions des Produits de l’Industrie in 1802 and 1806; unfortunately for Maelzel and his chances for a medal, the next exposition was not to take place until 1819.[43]

He left Paris in 1808 for another tour, taking with him the Chess Player, the second Panharmonicon, and the Trompeter. Another automaton trumpeter was constructed independently and almost simultaneously by a Saxon inventor named Kaufmann, to high praise from the composer Carl Maria von Weber. Kaufmann had already built a Belloneon, a mechanical drum and bugle corps for which he had used real drums and possibly real trumpet bells but no humanoids, just bare machinery. Legend has it that one night when Napoleon was occupying the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin after the Battle of Jena (1806), one of his staff officers switched it on, setting off a loud performance of a Prussian cavalry march and throwing the French general staff into confusion. Legend also has it that when Napoleon was occupying Vienna (1809), he sat down to a game with the Chess Player, and it does seem that Maelzel was there around that time. Napoleon supposedly insisted on making illegal moves, eventually provoking the Turk to sweep the men off the checkered battlefield. Another story, more plausible, is that Maelzel’s Trompeter blew a chronogram in honor of Napoleon’s marriage to the Austrian Archduchess Maria Luisa (1810).[44] During one of Maelzel’s frequent but brief stops in the Austrian capital, he received the title of K.-K. Hofmechaniker in recognition of his ingenuity. Passing through Milan in 1809 or 1810, he sold the Chess Player to Napoleon’s stepson, Prince Eugène, who could not bear to allow it to leave without learning its secret. In Amsterdam in 1812 he met a mechanician named Diederich Winkel and joined him in his work on a pendulum chronometer for musicians.

Back in Vienna the following year he became friends with Beethoven. He constructed a series of ear trumpets for the composer, who used the last model for a decade until his hearing gave out altogether. For his part, Beethoven agreed to write a piece for the Panharmonicon in honor of Napoleon’s defeat in Spain. It is a little-known fact that the famous battle symphony entitled Wellington’s Victory was originally written for this equally little-known mechanical instrument. What is more, Beethoven composed the piece around Maelzel’s musical ideas. According to Ignaz Moscheles, a pianist, composer, music teacher, and music chronicler then resident in Vienna:

Maelzel then urged Beethoven to reconstruct his symphony for human musicians, while he himself welded together an orchestra out of the best such individuals available. He also placarded Vienna. The promised concert consisted of the premiere of Beethoven’s seventh symphony, two marches for automaton trumpeter with orchestral accompaniment, and the premiere of Wellington’s Victory. The audience and the press went into raptures and the composer’s already lofty reputation ascended into the next heaven. He returned the favor by lending divine authority to the inventor’s crusade to convert European musicians to the use of his new pendulum chronometer.[45]I witnessed the origin and progress of this work, and remember that not only did Maelzel decidedly induce Beethoven to write it, but even laid before him the whole design of it; himself wrote all the drum-marches and the trumpet-flourishes of the French and English armies; gave the composer some hints, how he should herald the English army by the tune of “Rule Britannia”; how he should introduce “Malbrook” in a dismal strain; how he should depict the horrors of the battle, and arrange “God save the King” with effects representing the hurrahs of a multitude.

Maelzel’s new chronometer? To Winkel’s original invention of a double pendulum—a vertical metal bar, with a fixed weight at the bottom end, a sliding weight more or less near the top end, and a pivot in the middle attached to a spring-driven oscillating mechanism—Maelzel had added a scale of values, the name “metronome,” patents in four countries, and workshops in Paris, Vienna, and London to reproduce it. He successfully solicited endorsements from dozens of the most esteemed musicians in Europe so that within a few short years the machine was in widespread use. Winkel protested vociferously, and committees of scientists and editors of music journals pronounced in his favor; meanwhile Maelzel minted money. Winkel made one last grasp at success. Integrating some of the features of organs with some from looms, he contrived a machine that, given a theme, could compose variations on it ad infinitum—well, 14,513,461,557,741,527,824 variations anyway. He exhibited his Componium in Paris, where the Académie des Sciences reported favorably on it, but he received no awards, no pensions, no offers. Winkel died destitute at the age of forty-six, forgotten. Maelzel died a millionaire at sixty-six, known to posterity as the inventor of the metronome.[46]

Maelzel did not acquire all that money by assembling craftsmen and salesmen to produce and distribute his metronome. In fact, the Chess Player had always been his most productive worker, so he bought it back in 1818 for the same thirty thousand francs he had received for it from Prince Eugène, the latter’s fortune having fallen as it had risen, as an arm of the fortune of the nepotic Napoleon. Again he arrayed his mechanical men and set out to reconquer the imagination of Europe.

And again he punctuated his travels with extended sojourns in Paris, where he made new humanoids. In 1818 he added an automaton slack-rope acrobat:

So wrote a contemporary authority in a treatise on organ building and builders, a person by no means inexperienced in mechanics. He also described in detail Maelzel’s invention of talking dolls, mentioning en passant that the Chess Player “pronounced very distinctly the word ‘check.’” Maelzel exhibited the dolls, whose vocabularies were limited to “papa” and “mama,” at the 1823 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie. It does not seem that he won a medal.[47]The most surprising thing about this little masterpiece of mechanics is the impossibility of figuring out how all of its various movements can be produced, because the automaton suspends itself now by one hand, now by the other, now by its knees, now by its toes, then it straddles the rope and twirls its body around it, thus abandoning one by one all of its points of contact with the rope, through which must necessarily pass whatever communicates movement to it.

From 1818 to 1821 Maelzel showed the Chess Player, second Panharmonicon, automaton trumpeter, and automaton acrobat in London and throughout Great Britain. He spent most of the period from 1821 to 1825 in Paris, dividing his time between the exhibition hall and the workshop. He occasionally forayed abroad with his inverse mime troupe, which made a great deal of noise mimicking human beings. Late in 1825, Maelzel sailed away from the Old World.

No sooner did he arrive in the New World than he sold his Panharmonicon for the stupendous sum of four hundred thousand dollars. He kept the other showpieces he had brought over with him, however, and these may have included, in addition to his own trumpeter and two acrobats and Kempelen’s Chess Player, a Jaquet-Droz writer-sketcher. One such, at least, was discovered at the Franklin Museum in Philadelphia in the mid-twentieth century with an ascription to Maelzel. Over the next dozen years the curious European automata saw New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, Washington, Pittsburg, Cincin-nati, Louisville, New Orleans, and doubtless many other American cities before embarking for Havana. They may also have traveled in Canada. In Boston, the twenty-five-year-old P. T. Barnum “had frequent interviews and long conversations with Mr. Maelzel. I looked upon him as the great father of caterers for public amusement, and was pleased with his assurance that I would certainly make a successful showman.” [48]

The Chess Player continued to be Maelzel’s main attraction. But a year or so after his arrival in America a couple of enterprising Yankees began to exhibit an imitation of the imitation chess player. And they refused his offer of a thousand dollars and employment to surrender this compounded copy. For some reason, even though both chess players continued to perform in public, the original imitation prevailed. Later another enterprising American produced another imitation chess player, but this time the game ended with money changing hands, the latest imitator converting his imitation chess player into an imitation whist player, and both imitator and imitation joining Maelzel’s entourage.[49]

The Chess Player, built by Kempelen. Courtesy of the John G. White Collection, Special Collections, Cleveland Public Library. Photograph by the Cleveland Public Library Photoduplication Service.

[Full Size]

The increasing diffusion of the knowledge of the Chess Player’s secret had probably determined Maelzel to depart the Old World when he did. Various observers had divined various aspects of the deception almost from the beginning, and the most skeptical observers had immediately penetrated the most important aspect: A human being was hidden inside the cabinet.[50] But many people wanted to believe, and within the multitude who stood between skepticism and faith the enlightenment proceeded slowly.

The movements of the Turk were governed by a modified pantograph, such that he simply duplicated on the outside of the cabinet the movements made by his guiding spirit on the inside. Who directed the Turk in his early years remains a mystery. After he passed from Kempelen to Maelzel the latter employed a series of Café de la Régence masters: Alexandre, Boncourt, and Weyle for short spells in Paris, Jacques-François Mouret for most of the British tour, and Wilhelm Schlumberger for most of the American tour. Thus during the periods when the Turk had Maelzel for his prophet he played first-rate chess, which undoubtedly contributed a great deal to his continuing success. In 1834 Le Magasin pittoresque and in 1836 Labourdonnais’s periodical Le Palamède published the secret, which had been revealed by Mouret, the great-nephew of the great Philidor.[51]

Maelzel himself had talent in the art of chess as well as in the art of music, but he was a better artisan than artist, and a better artificer than artisan. Maelzel died on board ship between Havana and Philadelphia in 1838; the Turk perished in Philadelphia’s Chinese Museum when it burned in 1854.[52] But as an automaton is only the shell of a human being, and the Chess Player only the shell of an automaton, what was destroyed was only the shell of the Chess Player. Its spirit survived into future generations; indeed, it proliferated.

| • | • | • |

§ 2. The Mechanician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805–1871)

The automaton-builders who made imitations of skilled human beings had a variety of purposes. Vaucanson probably conceived his automata, at least originally, as scientific projects. The Jaquet-Drozes conceived theirs as lux-ury products. Kempelen conceived his to impress his sovereign. But gradually the conception of automata as exhibition pieces, Maelzel’s conception, prevailed over all others. And gradually the show prevailed over the machinery, so that many builders exhibited quasi-automata and pseudoautomata in place of true automata. Although the pseudo-automaton seems degenerate, a soulless copy of the true automaton, it retained two of the most attractive charms of the true automaton: imitation and deception. The pseudo-automaton, just like the true automaton, imitated something else and in doing so deceived people into believing it could do what that something else did. Automata were a kind of magic trick, and they and magic shows had their vogue together.

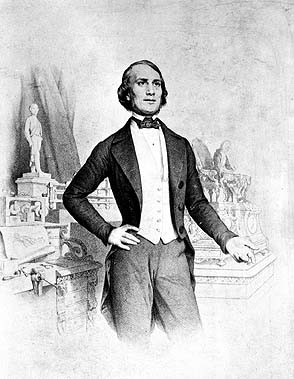

Portrait of Robert-Houdin. Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Photograph by the Library of Congress Photoduplication Service.

[Full Size]

If the name Robert-Houdin is familiar at all to Americans, it is because America’s most famous magician, Harry Houdini, born Ehrich Weiss, renamed himself after this most famous magician of France, born Jean-Eugène Robert. “When it became necessary for me to take a stage-name, and a fellow-player, possessing a veneer of culture, told me that if I would add the letter ‘i’ to Houdin’s name, it would mean, in the French language, ‘like Houdin,’ I adopted the suggestion with enthusiasm.” From the very beginning of his career Houdini strove to imitate Robert-Houdin: “My interest in conjuring and magic and my enthusiasm for Robert-Houdin came into existence simultaneously. From the moment that I began to study the art, he became my text-book and my gospel.” As of the late nineteenth century, when Houdini was growing up, not many first-class magicians had written books about conjuring techniques, as Robert-Houdin had; fewer still had written an autobiography describing their experiences, as Robert-Houdin had; and none of their lives had been as fascinating as Robert-Houdin’s had been. Houdini in turn wrote books about conjuring techniques, one of which he called The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin: “In the course of his ‘Memoirs,’ Robert-Houdin, over his own signature, claimed credit for the invention of many tricks and automata which may be said to have marked the golden age in magic. My investigations disproved each claim in order.” [53] But Robert-Houdin’s claims were no more exaggerated than those of the other stage magicians discussed by Houdini, whose inventiveness generally consisted of reworking or reclothing old tricks. Houdini eventually came to realize that the real deceptions in his book were his, not his model’s, although he could only bring himself to acknowledge one: “The only mistake I did make was to call it the name I did when it ought to have been ‘The History of Magic.’” [54] Everything having to do with stage magic, even writing about it, comes down to imitation and deception.

Robert-Houdin remains today one of the revered masters of the “tricks and automata which may be said to have marked the golden age in magic,” to use Houdini’s phrase, which reflects the consensus of historians of magic on the advanced state of that art in the early and mid-nineteenth century.[55] So was the Frenchman essentially a magician and only incidentally a mechanician? Houdini’s phrase implies the answer: Legerdemain and automaton-building were considered two branches of the same tree of magical knowledge. From the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, most conjurers worth their saltpeter presented mechanical humans or animals in their shows. After all, both sleight-of-hand tricks and mechanical marvels demonstrated manual dexterity. And both legerdemain and automata featured deception: The power of the former depended on the implication that something supernatural was happening; the power of the latter on the implication that a machine could do what a human being or an animal can do. Watching a feat of legerdemain, the spectator’s mind was not persuaded of the presence of something supernatural, but the spectator’s senses were baffled. Watching an automaton, the spectator’s senses were not persuaded of the presence of a living being, but the spectator’s mind was perplexed by the thought that a living being might be no more than a very complicated machine. In neither case was the implication demonstrated, but in both cases it seemed to have been. As for Robert-Houdin, he built machines of one sort or another throughout his life and gave magic shows for only around a decade.

Jean-Eugène Robert was born in 1805 in the small town of Blois, which lies on the Loire River about a hundred miles south-southwest of Paris. His father, Prosper Robert, who had his own business, practiced clockmaking and related arts: “an excellent engraver, a jeweler of taste, he could even if need be sculpt an arm or a leg for a mutilated statue.” So boasted the son, anyway, who as a child wanted nothing more than to imitate his father. “I am tempted to believe that I came into the world with a file, a compass, or a hammer in my hand, because from my earliest childhood, these instruments were my toys, my playthings.” His early inclinations notwithstanding, his father sent him to Orléans, a large town nearby, to attend its collège, a secondary school designed to prepare its students for either higher education or direct entry into a professional career. Prosper Robert had the normal ambition to push his child at least one rung further up the social ladder from his own position. Jean-Eugène studied diligently if unenthusiastically and returned to Blois a graduate at the age of eighteen. His father, pleased by this success, allowed him to idle away a few months doing whatever he wanted, during which time he saw a sleight-of-hand artist perform on the street. “It was the first time I ever attended such a spectacle: I was amazed, stupefied, dumbfounded.” Finally Prosper asked his son to choose a profession and found that Jean-Eugène stubbornly clung to his desire to become a clockmaker.[56]

The equally stubborn father placed his son in a notary’s office. A notary in nineteenth-century France was a kind of second-class attorney, handling a lot of routine legal documents; the occupation was low in the ranks of the professions, but it was a profession. “I leave the reader to imagine how this automaton’s labor suited my nature and my mind: pens, ink, nothing was less appropriate to the execution of the inventions for which I ceaselessly generated ideas.” Jean-Eugène suffered a notary copyist’s boredom for three years, spending much of his free time and some of his work time building mechanical gadgets. Finally, whether because his son had bowed to his wishes for so long, because his son’s stubbornness had proven superior to his own, or because he had ceded all further resistance in ceding his business to his nephew—Jean-Eugène’s cousin—the retired clockmaker agreed to allow his son to apprentice in his old shop under the supervision of its new owner.[57]

Jean-Eugène Robert had found his way to half of his vocation. The other half, at least according to his autobiography, Confidences et révélations, found its way to him. Going out to a bookstore one day to buy a book on clockmaking, he returned with a book on conjuring that the bookseller had wrapped up for him by mistake. This “wrong book” enchanted him, so he set out to learn legerdemain.