Looking at the Looking, Even

The mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.

—Oscar Wilde

The spectator makes the picture.

—Marcel Duchamp

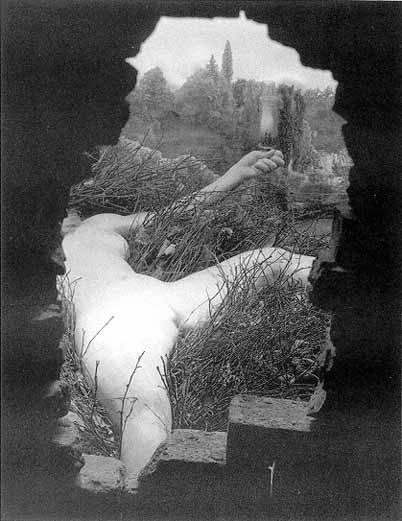

Once we are on the threshold of the door to Given , an unusual sight confronts us (fig. 71). Looking through two small holes at eye level, we find ourselves in front of a display akin to both window displays and to a rudimentary peep show. Golding summarizes this "extraordinary" sight as follows:

On a plane parallel to the door and some few feet beyond is a brick wall with a large uneven opening punched through it. Beyond and bathed in an almost blinding light is the figure of a recumbent woman modelled with great delicacy and veracity but also slightly troubling because the illusion of three dimensionality is strong but not totally convincing (the figure is in fact in about three-quarter relief). She lies on a couch of twigs and branches and she opens her legs out towards the spectator with no false prurience or sense of shame.[15]

Fig. 71.

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1) The Waterfall, 2) The Illuminating Gas (Etant Donnés:

1) La Chute D'eau, 2) Le Gaz d'Éclairage), 1946–66. Interior view.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of the Cassandra Foundation.

Before examining this scene, it is important to consider the voyeuristic context in which it takes place—the way in which the gaze of the viewer is set up. The problem with the scene is its "hyperreality," its excessive realism, which stages eroticism as a "too" obvious spectacle.[16] The dioramalike character of the scene is further emphasized by the presence of an almost blinding light, an excess of illumination. The enigma that Given presents to the viewer is like no other. What mystifies the viewer is exactly

the overdetermined "explicitness" of Given : its hypervisibility and emphatic sexuality. The excessive clarity of the scene makes us question the unquestionable: "What then is less clear than light?"[17] This scene problematizes one of the major givens of the Western pictorial and philosophical tradition: the equation of reason and light, since light here functions as the sign of doubt. The excessive illumination of the scene makes us uncomfortable, breaking up the structure of voyeurism, its raison d'être—as the equation of sight and pleasure.[18]

The perspective of the viewer is fragmented by the hyperreality of the image, by its overdetermined character. The illumination of the scene illuminates our gaze, effectively disrupting the coincidence of vision and the reality of sex. Thus, the verisimilitude of the scene, the reduction of the body to reality, is derealized, since vision itself is refracted by being staged through the peephole apparatus. The scene presented to the spectator can be neither anticipated nor participated in. The traditional structure of spectatorship is dislocated, since the viewer cannot simply identify him- or herself through looking, and thus take pleasure in "making" or appropriating the picture by inscribing his or her own desire. This image "unmakes" its viewer. The authority and the legitimacy that Western "retinal" painting confers on its spectator are here undone, since the blatant sexuality of the image challenges the act of looking. The coincidence of the eye and the "I," represented in the notion of perspective as a point of view, is irrevocably disrupted.[19] This is why, despite its explicit sexual content and its peephole character, Given cannot be equated with the objectification of the female body through voyeurism. While feminist and film studies have elucidated the ideological underpinnings of the male gaze through an analysis of the role of the camera and structures of spectatorship, Given challenges such a reduction by objectifying the very presuppositions that govern the visible"[20]

A tableau vivant that travesties itself as a "nature morte," Given restages the issues that Duchamp elaborated in sculpture-morte (fig. 57, p. 150), or more explicitly, in TORTURE-MORTE (fig. 56, p. 148). Contemporary to Given, these assemblages stage the dead-end character of visual illusion, as it attempts to replicate the real. The excessive realism of these assemblages reveals that they, like Given , are false doorways to the "real." They problematize the indexical nature of vision, its ability to

refer or point, since their simulated reality cannot be resumed either in the order of demonstration or designation. Rather than taking for granted the referential relation of vision and sexuality (as art historians have done), or by reducing vision to the ideology of the gaze (as feminist critics have suggested), this essay will resituate the notion of sexual difference by questioning how vision determines its "modes of appearance" (to use Duchamp's terms) in Given . At issue, therefore, is the phenomenality of vision, its construction, and its effects.[21] In order to explore how the visible is constructed in Given through the displacement of indexical relations, it is vital to examine two of its major "hinges," the body and the landscape, which are both traditional sites in the history of art for the mimetic creation of "reality."

To begin with, the androgynous nature of this nude figure (the "last nude," to echo Lyotard) is ambiguous, with passively and/or aggressively bared genitals that are echoed in the pointed gesture of the raised and disproportionately enlarged arm that is assertively clasping a gas lamp. Recalling Gustave Courbet's Woman with a Parrot (1866), the nude's upraised arm holds a gas lamp, instead of the vividly colored parrot. The painterliness of the parrot, whose range of colors recalls the painter's palette, may be an allusion to Courbet's own fascination with pictoriality.[22] Replacing the parrot, the "phallic" upturn of the gas lamp illuminates Duchamp's invitation to the spectator to renew his or her "gaze," by literally casting painting in a new light. While drawing on the conventions of painting, Duchamp's installation of the plaster cast nude also announces its imminent demise. The androgynous character of the nude, manifest in the deictical gesture of the raised arm with the gas lamp, activates the nude as a potential agent or subject, rather than as a mere object of display. Although more can be said about the androgyny of the nude, little has been said about its "dead" or "mechanical" character. The sexual ambiguity of the nude is compounded by a more profound ambiguity: that of the reality of its "life." Before examining some of Duchamp's explicit references to nudes in a series of lithographs based on Courbet, it is helpful to consider his allusions to René Magritte's (1898–1967) painting The Threatened Assassin (L'Assassin menacé ; 1926) (fig. 72).[23]

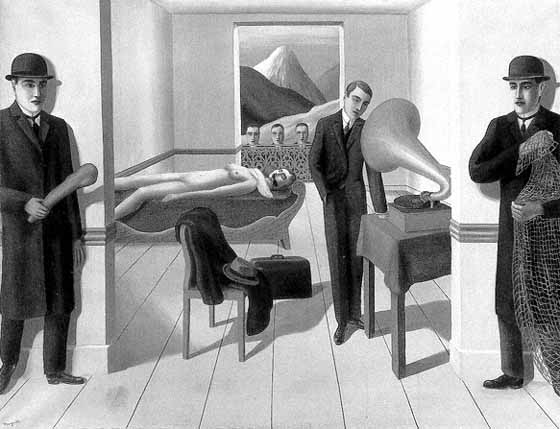

In addition to presenting a mannequin (a "dead nude"), Magritte's The Threatened Assassin , like Given , stages the structure of voyeurism as a

Fig. 72

René Magritte, The Threatened Assassin (L'Assassin Menacé), 1926.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

gendered gaze, since the ambiguous "assassin" and/or "policeman" in the foreground is conflated with the gaze of the viewer. This painting represents the fragmentation of pictorial perspective or point of view through the multiplication of figures of assassins, policemen, and/or witnesses within its frame. The two "assassins/ policemen" in the foreground are conflated in the figure of the man listening to the gramophone, as witnessed by three men in the background, surveying the scene from behind the balcony. These three figures look at the viewer looking. The painting sets into motion a delirium of vision, a variety of male spectators—potential assassins and policemen, organized around the spread-eagled nude. Magritte's painting, like Duchamp's Given , stages both the transgressive (assassin) and the rationalizing (policing) dimensions of the spectator's gaze. The victim at the center of the scene, the nude as both text and pretext of representation, embodies the "deadening" or even "murderous" character of the male gaze, as it objectifies (and thus "kills") the body offered for viewing. The body of the nude thus emerges merely as residue, the dead torture (torture morte ) of the male gaze that has immortalized it in the history of painting. The violence of the gaze, however, paradoxically killed a mannequin, a figure embodying ready-made conventions.

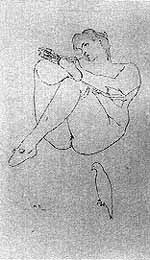

Duchamp's allusions to Courbet's paintings make explicit the structures of spectatorship and voyeurism implicit in his works. The lithograph Selected Details After Courbet (Morceaux choisis d'après Courbet ; March 1968) (fig. 73) reproduces Courbet's famous painting in the Barnes's Collection Woman with White Stockings (fig. 74), with one remarkable difference. At the bottom of Duchamp's lithograph is the additional figure of a falcon (faucon , in French, a pun on faux con ) who disrupts our perspective of the visual field, since the falcon in the foreground is disproportionately smaller—although it is closer to our field of vision. Presented as a peeping torn, the falcon embodies visual prurience since his name is a pun on faux con (false sex, in French). This verbal pun on false sex (faux con ) competes with and displaces our attention from the visual referent, the "true sex" (vrai con ) of the nude's bared genitals.[24] Embodying the voyeuristic desires of the spectator, the falcon makes explicit the representational conventions that define the construction of sexuality as visual referent. The supposed reality of sex as visual fact is reframed by the verbal puns that play the falcon off against the facticity of sex.

Fig. 73.

Marcel Duchamp, Selected Details

after Courbet (Morceaux Choisis

d'après Courbet), second state, 1968.

Etching pulled on japan vellum, 19 7/8 x

12 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

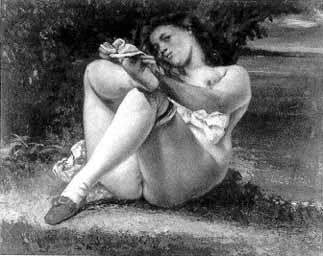

Fig. 74.

Gustave Courbet, Woman with White Stockings

(Femme Aux Bas Blances), 1861.

Courtesy of The Barnes Foundation, Merion Station, Pennsylvania.

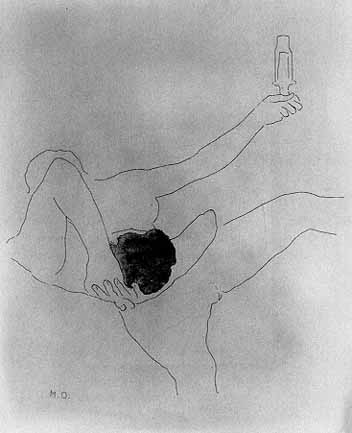

The punning reference to the genitals of the nude can also be seen in another lithograph from the same series as Selected Details After Courbet , entitled The Bec Auer (January 1968) (fig. 75). Superimposed in this lithograph depicting a nude who is clasping a gas lamp like the one in Given is the figure of a male companion whose hairy head decenters our gaze from the woman's genitalia, thus resituating the sexual referent of the image. The viewer's gaze of the woman's head is physically blocked by the man's elbow and internalized within the image through his gaze back at her. The spectator's voyeurism is illuminated, as it were, by the man's privileged visual access to this scene. The title of this lithograph. The Bec Auer , which refers to the brand name of an electric bulb, reinforces this suggestion. Duchamp thus illuminates the spectator's gaze in a manner that recalls the falcon (faux con ) in Selected Details After Courbet (Morceaux choisis d'après Courbet ), which is a pun on the viewer's gaze as visual delectation. As the figure of desire, the gaze is equated with the falcon's beak pecking at favorite morsels, "morceaux choisis ." This interplay of visual and verbal puns suggests that the "illuminating gas" in the title of Given may refer to and illuminate the "gaze" as well. These lithographs illuminate the conventions of spectatorship by documenting the failure of the male gaze to penetrate or objectify the notion of sexuality.

Fig. 75.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bec Auer, Second State, 1968. Etching pulled on

Japan vellum, 19 7/8 x 12 13/16 in. Courtesy of The Philadelphia

Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

For the display of nudity in these works makes visible the dead-end character of painting understood as a peep show

Duchamp's allusions to sexuality in Given parody its "reality" through his punning reproductions of Courbet. The "sexuality" of the nude is depicted as it is being "reproduced," assembled and taken apart, realized and derealized, simultaneously. Thus, the pictorial representation of sexuality emerges as a mere decoy, an object simulating the illusion of life by acting mechanically as lifelike. The nude in Given derives her eroticism from her mannequin-like character: her lifelike semblance stages life hyperrealistically—more successfully than life itself. The discourse of eroticism in Given is thus revealed transitively, not as an attribute of

appearance but as a movement, the declension of an apparition (recalling Duchamp's famous Nude Descending a Staircase , No. 2) (fig. 7, p. 27). Rather than merely revealing the naked sex, the absence of pubic hair on the sex of the nude also alludes to the pictorial tradition throughout which the female sex had been dissimulated, and thus outlined, even more emphatically. Duchamp's allusion in his notes to the veiled sex, the "Abominable abdominal furs" (Notes , 232) becomes a pun on fur (fourrure ) as mad laughter (fou rire) (Notes , 272). This pun stages the ambiguous meaning of genitalia in Given . It designates the recognition that sexual organs may be only the "indirect" index of gender, and consequently, no more reliable than a joke, like the false mustache and beard added to Leonardo's Mona Lisa in Duchamp's rectified ready-made L.H.O.O.Q. (fig. 53, p. 140). Instead of veiling the female sex in Given by covering it up with "abdominal furs," Duchamp bares it, or rather, shaves it like L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (fig. 55, p. 146). The field of twigs (shavings) surrounding the nude marks this displacement. Sexuality is thus presented as a movement, the imperceptible visual and linguistic slip (the fake striptease), enacting through the anamorphosis of a pun the transitional character of eroticism.

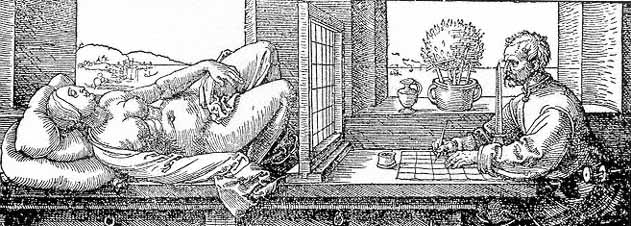

This construction of eroticism as a movement can also be seen in Duchamp's implicit reference in Given to Albrecht Dürer's Draftsman Doing Perspective Drawings of a Woman from De Symmetria Humanorum Corpum (Nuremberg, 1532) (fig. 76). In this print a stylus is interposed between the eye of the spectator and the view point (which corresponds to the sex of the woman). The stylus is an archaic instrument, a machine for the organization of perspective, at whose edge or point the viewer adjusts his or her eye. At some distance, there is a small gate through which the visual rays of the body are projected. Jean Clair, in "Marcel Duchamp et la tradition des perspecteurs," describes the scene in similar terms, without dwelling, however, on its meaning.[25] The figure of the body viewed through the stylus elucidates the nature of eroticism in Duchamp as a rhetorical operation .[26] In the Dürer etching the stylus , which is normally a writing utensil, doubles as a visual instrument for the construction of the body, designating sexuality as the site (sight) of coincidence, constituted through both writing and vision. By analogy to Dürer's etching, sexuality thus emerges in Duchamp's Given

Fig. 76.

Albrecht Dürer, Draftsman Doing Perspective Drawings of a Woman,

from De Symmetria Humanorum Corpum (Nuremberg, 1532).

as an artificial construct, like the construction of the body in the history of perspective. Rather than merely representing an anatomical destiny or the embodiment of a gendered gaze, as Dürer does, eroticism in Given emerges as the figure of passage. Its transitional nature as the movement of style marks it simultaneously as the site of composition and decomposition, of life and death—Eros and Thanatos. The transitive nature of this movement cannot be embodied and figured through the body as either an object or image. Instead the body becomes the "hinge," a frame of reference for sexuality understood as the figure of style . For Duchamp, "the logic of appearance" is expressed by the "style" (Notes , 69), indicating his recognition that form is merely "conditional" (Notes , 71). This is why the transgressive aspects of voyeurism in Given are short-circuited. Eroticism cannot be reduced to a gaze that isolates sexual difference from its metonymic position, its circuit of signification. Since sexual difference in Duchamp's works is conditional , it can also be assimilated to indifference. Femininity and masculinity are set not in opposition to each other, but in conjunction. Their strategic coincidence marks a repetition, whose difference emerges not as a set term, ontologically grounded, but as the declension, the descending nude outlying the trace of the figurative movement of style.