Preferred Citation: Judovitz, Dalia. Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3w1005ft/

| Unpacking DuchampArt in TransitDalia JudovitzUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1995 The Regents of the University of California |

to Hamish M. Caldwell,

Eros, c'est la vie

Preferred Citation: Judovitz, Dalia. Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3w1005ft/

to Hamish M. Caldwell,

Eros, c'est la vie

Acknowledgments

This project has in its background the writings of Jean-François Lyotard, Octavio Paz, Arturo Schwarz, Thierry de Duve, Jean Clair, and Rosalind Krauss. I am especially grateful for the research opportunities offered by a sabbatical year fellowship and grant awarded by Emory University, which enabled me to successfully complete this project. My special thanks go to Marjorie Perloff and Naomi Sawelson-Gorse for their generous comments and suggestions, and to my friends and colleagues of The International Association for Philosophy and Literature. I owe a great deal to Edward Dimendberg for his enthusiastic editorial support, as well as to Michelle Nordon, the production editor, and to Michelle Ghaffari, the copy editor. I am particularly indebted to Patrick Wheeler for his assistance with the book's bibliographic materials, copy editing, illustration, and general production. My greatest debt is to the person who inspired this volume and sustained it with unfailing love and undying humor, my husband Hamish Caldwell.

The following articles served as points of departure, providing initial approaches to the questions elaborated in this volume:

"Art and Economics: Duchamp's Postmodern Returns," Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts 135, no. 2 (Spring 1993): 193–218.

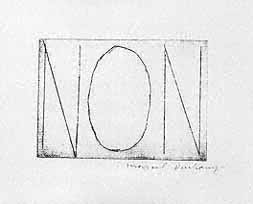

"(Non)sense and (non)art in Duchamp," Art & Text, Nonsense (special supplement in conjunction with the Whitney Museum of American Art), no. 37 (September 1990): 80–86.

"Rendez-vous with Marcel Duchamp: Given, " Dada & Surrealism, no. 16 (1987): 184–202. Reprinted in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. Rudolf E. Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989).

Author's Note

The most frequently quoted references to Duchamp's writings and interviews are to the following volumes: Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Da Capo Press, 1987), which will henceforth be abbreviated as DMD, page number; Paul Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Boston: J. K. Hall & Co., 1983), which will henceforth be abbreviated as Notes, page number; and Michel Sanouillet and E. Peterson, eds., Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), which will henceforth be abbreviated as WMD, page number.

Copyright for all the Marcel Duchamp illustrations is held by Artists Rights Society © 1993 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris; the Man Ray illustration is © 1993 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP and The Man Ray Trust, Paris. Reproduced here by permission.

Introduction:

Unpacking Duchamp

Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase.

—Marcel Duchamp

New York, March 1952

The Marcel Duchamp retrospective at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (Summer 1993) reminds us once again of the seminal role played by Duchamp in the history of modern art. Rather than functioning retrospectively, however, this exhibition brings to the fore the centrality of Marcel Duchamp's work not merely to the history of Modernism but its living legacy to the current debates regarding postmodernism. At issue is less the question of canonizing Duchamp for posterity, than the fact of coming to terms with his works in a manner that addresses their complex, poetic, logical, and also humorous, urgency. The most troubling aspect of Duchamp's works is that they are not merely visual artifacts but rather works that embody thought processes, logical and poetic displacements that resist facile categorization or containment. While there is no unifying style that defines his work, no single thread or hidden message, Duchamp's works compel the spectator to question the traditional categories that have defined the notion of the art object, the creative act, and the position of the artist. The spectator completes, as it were, the creative process not as a passive consumer but as an active interpreter. It is this postponement of artistic intent and its manifest realizations that explains Duchamp's persistent influence on the history of Modernism and his impact on its fate, whether that future is today labeled as postmodernism, and tomorrow, as something yet unnamed.

How, then, is the spectator to understand Duchamp's works? What

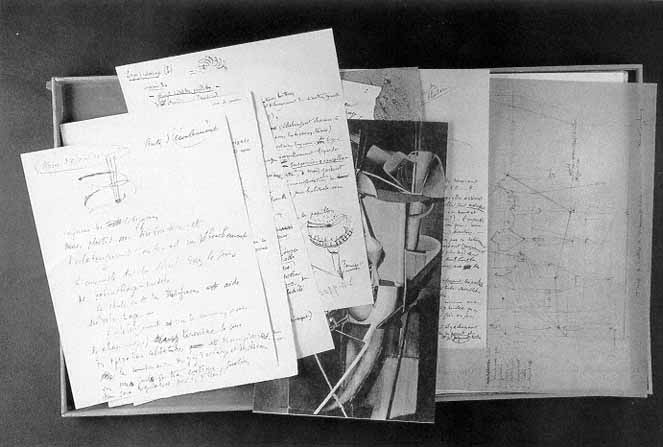

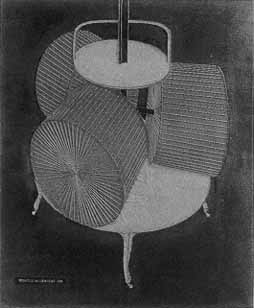

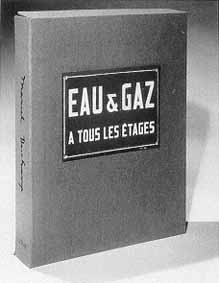

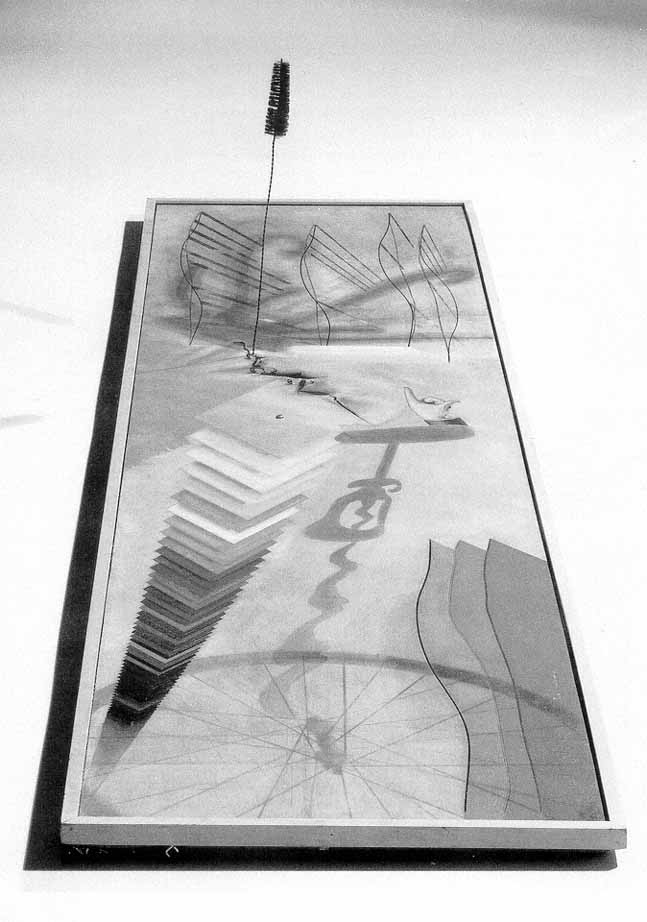

forms of initiation are available to provide an interpretative access to his works? The critical scholarship on Duchamp constitutes an immense corpus ranging from the scientific to the theoretical and the esoteric. Given the privileged position of the spectator in Duchamp's works, every critical approach and scholarly movement has added significant insights to his oeuvre. So where does one begin, given that Duchamp's pictorial origins herald an ending of sorts—that of the abandonment of painting, followed by the renunciation of conventional art forms. One way is to begin with what initially appears to be a provisional ending, Duchamp's commemorative work The Box in a Valise (first published in 1941 through 1949), a "portable museum" in miniature containing reproductions of his principal works. This work is both a compilation of his previous works, as well as a multiple, since it is merely the first copy in a series of twenty. Due to its derivative and reproductive character, this work can easily be dismissed as the least creative of Duchamp's works, reinforcing the contention that Duchamp had simply run out of new ideas. Yet, a closer scrutiny of The Box in a Valise suggests that this work may provide fundamental clues toward an understanding of his works. Notably, this work draws our attention to Duchamp's interest in the notion of reproduction and the multiple as a way of redefining art, not as an imitation of reality but as a system of production that takes itself to task. It is a reminder that the notion of artistic production should be reexamined as a function of reproduction; that is, as a deliberate restaging and reappropriation of his previous works and the artistic conventions that define them. Moreover, The Box in a Valise makes manifest the interpretative challenge that it extends to the spectator through its deliberate invitation to be unpacked. What does it mean to conceive the work of art as a box or valise? Furthermore, can the notion of unpacking Duchampprovide us with significant new insights into his transitive redefinition of the art object, artist, and art?

In light of Marcel Duchamp's summation of his artistic corpus in a box, which is also a portable valise, his incidental comment "Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase" takes on a certain gravity. For some, Marcel Duchamp's contention epitomizes his particular contribution to the history of art: he is an artist whose real baggage consists not of the objects produced but of the ideas and artistic con-

ventions in question. For others, Duchamp's statement is merely a factual endorsement of his relatively small artistic production, a confirmation of his preference for chess or even inactivity espoused in such pronouncements as: "I like breathing rather than working." Unpacking Duchamp's works, however, turns out to be at once a more difficult and a less onerous task than we are led to believe. As John Cage observes, the challenge that Duchamp extends to posterity is precisely that of refusing to be boxed in, packed away, and conveniently labeled as an artist: "The danger remains that he'll get out of the valise we put him in. So long as he remains locked up."[1]

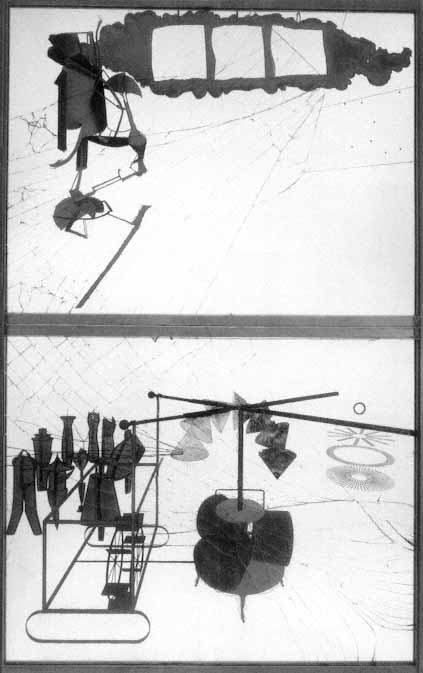

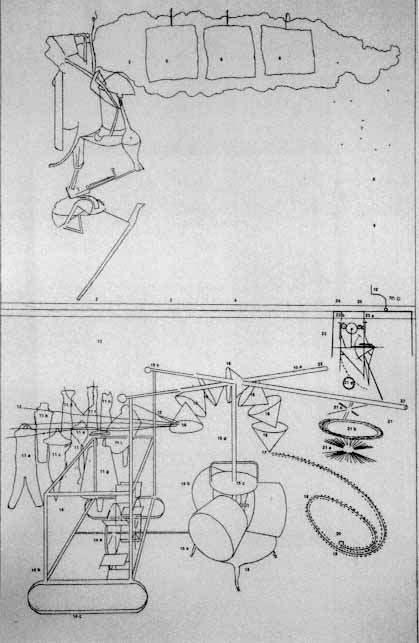

A rapid survey of Duchamp's career, which stretches over a period of fifty-nine years (1909–1968), reveals that Duchamp abandons painting in 1918, and that by 1923, he has ceased to produce conventional art altogether. Having revolutionized painting with his landmark Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, (Nu descendant un escalier, no. 2; 1912), a work that is part of a series and subject to multiple reproductions, he leaves traditional art behind with The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même, or The Large Glass; 1915–23), which reassembles and reproduces some of his previous pictorial works on glass. During this period, he shocks the art world with the discovery and exhibition of the ready-mades, mass-produced objects that Duchamp relabels and displays as art. While the Large Glass entails elaborate technical and mechanical handiwork, the ready-mades require no manual work at all. Following his compilation of technical/poetic instructions to The Large Glass in The Green Box (1934), Duchamp began to compile his previous works in miniaturized facsimile by assembling them in a box, a folding exhibition space entitled The Box in a Valise (1941–49). Although speedy reproduction techniques were already available, Duchamp opted for technically obsolete and time-consuming methods: collotype printing and hand coloring using stencils. As Ecke Bonk points out: "By using highly time-consuming techniques, he blurred the boundaries between the unique art object and the multiple, between the original and its mechanical reproducibility, and created a number of transitional stages that were hard to define or to distinguish."[2] Duchamp's deliberate choice to invest more labor in reproducing his own works rather than producing new ones attests to his consistent effort to

challenge the notion of artistic creativity by questioning the distinctions that separate an original from its reproduction and a unique work from its multiple copies. Did Duchamp begin reproducing and collecting his own work because he had stopped making art, or did he discover through The Box in a Valise a new way of thinking about artistic activity?

Before pursuing further this rapid survey of Marcel Duchamp's artistic career, it is necessary to examine the paradigmatic nature of The Box in a Valise toward an understanding of his works. As a literal compilation of his artistic corpus in miniature reproduction, The Box in a Valise follows Duchamp's previous, although more limited, efforts at reproduction and assemblage in The Large Glass. The Box in a Valise makes manifest Duchamp's efforts to redefine the notion of an art object, as well as the modes of artistic production. To unpack The Box in a Valise is to come to terms with how artistic representation functions as an assemblage, a system of framing and labeling. It suggests that artistic production is a system that reproduces and reassembles the conventions that frame and label various works as art objects. Duchamp's The Box in a Valise challenges as a compilation of multiples the priority and uniqueness of original works. This work restages the viewer's experience of Duchamp's works, no longer as singular or autonomous objects isolated in the museum but as an organic corpus. This portable museum of works in miniaturized facsimile suggests that the meaning of represented objects can only be addressed as a context of embedded gestures. By packing his most significant works in a suitcase, Duchamp withdraws the artwork from the confines of the museum. In doing so he reveals its embedded nature in the institutional frameworks that determine its meaning as art.

The invitation to unpack The Box in a Valise involves both a physical and a conceptual intervention. The physical process of unpacking these miniaturized replicas coincides with the intellectual discovery of their remarkable affinities and resonances. The process of unfolding creates a new way of experiencing these works, as a system where reference or meaning is generated through cross-reference. The significance and value of these works are revealed by their relationships to each other; their position in the box generates transparencies, overlaps, or zones of opacity. The autonomy of these works as individual objects is undermined, since their meaning and value is determined not by some inherent quality but

instead through their position in relation to each other. The Box in a Valise opens up a new way of approaching Duchamp's work, as a chess game or a language where meaning is transitional, generated through the interplay and strategic positioning of the constitutive elements. The meaning of individual works is not guaranteed either by the artist's intention or by history, it is there to be created anew each time, by the spectator, as a context generated through the interplay of specific works. The plasticity of Duchamp's intervention thus lies not in the objects but in their strategic syntax and poetic associations. Completed during World War II, the portability of The Box in a Valise stands as a testament to fragility and transition, not as a way of stepping out of history but as a way of reaffirming the vulnerability of art in the face of catastrophic historical change. This work underlines the significance of reproduction in Duchamp's works, not merely as means of perpetuating his works through facsimile but as a means of redefining artistic production by reassembling its constitutive elements.

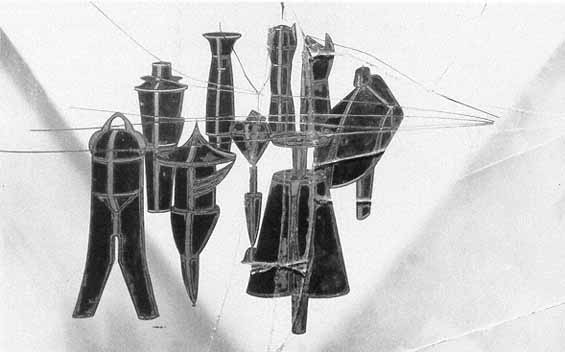

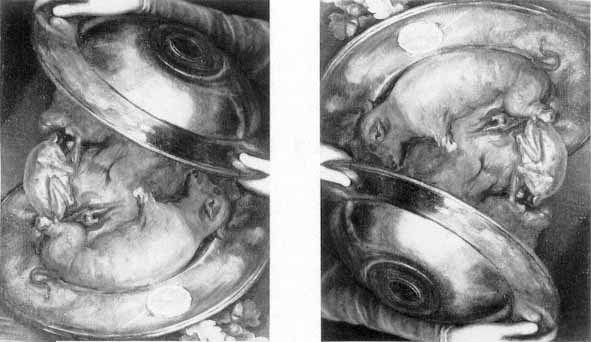

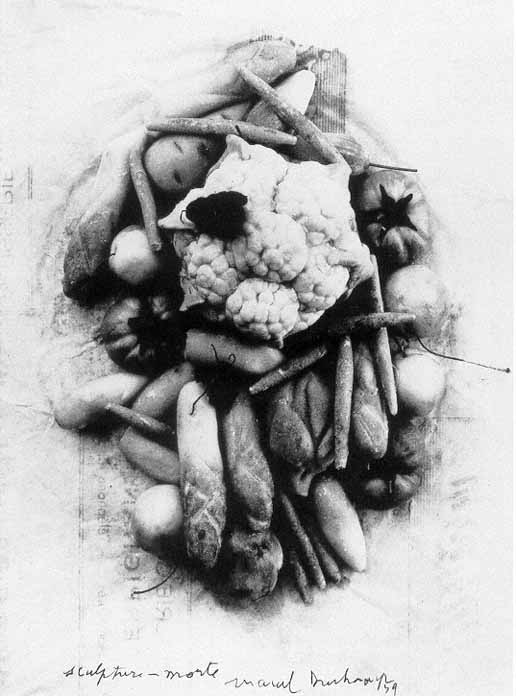

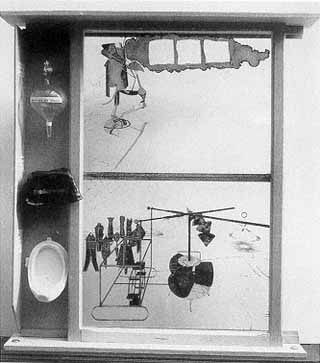

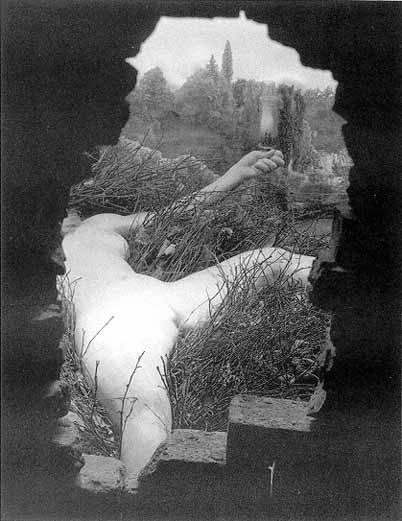

Resuming the survey of Duchamp's artistic career, despite his suggestion that he had given up art in favor of chess, Duchamp did not stop making new works. Starting in the late 1940s he begins to produce artworks in which exaggerated realism and deliberate artificiality stand in contrast with the literal simplicity and technological character of the ready-mades. While appearing to return to figurative conventions, Duchamp redefines the notion of artistic production by using artistic conventions, rather than objects, as ready-mades. These works are assemblages that parody the conventions of pictorial naturalism in order to demonstrate visibly their demise as literal death. These three-dimensional works, such as Female Fig Leaf (Feuille de vigne femelle; 1950, a plaster cast of female genitalia), and Dart-Object (Objet-Dard; 1951, a riblike phallus in galvanized plaster) are puns on the use of artistic conventions to represent gender. Following Duchamp's earlier exploration of the nude as a pictorial genre, these "realistic" plaster casts playfully reveal the artifices employed in both painting and sculpture to represent issues of sexual difference. They are followed by sculptural puns on the function of art as a medium for reproduction, notably, the pictorial still life (nature-morte ) TORTURE-MORTE (1959) and sculpture-morte (1959). During this period, unknown to his public and critics alike, Duchamp was also working on

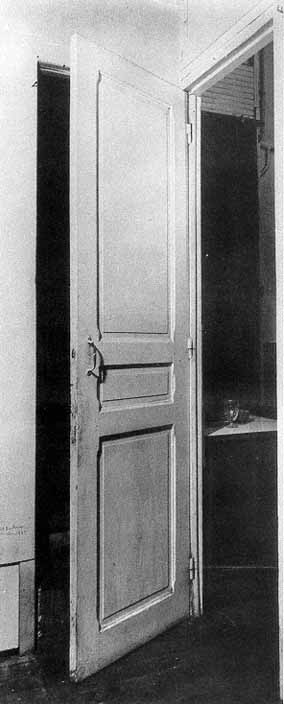

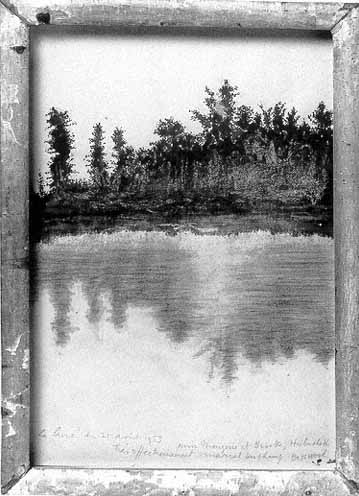

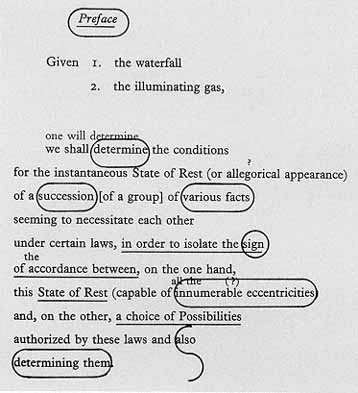

his testamentary installation, Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas (Etant Donnés: 1) la chute d'eau, 2) le gaz d'éclairage; 1946–66), a work exhibited posthumously with the directive that it may not be photographically reproduced for fifteen years. Devoid of modernist abstract tendencies, this work stunned the critics by its contrived naturalism, a tableau-vivant of a mock nude that displays herself in a dioramalike landscape. Painstakingly assembled during a period of twenty years, this work shocked the public because Duchamp seemed to be returning to pictorial conventions and a concept of art that he had supposedly abandoned long before. Duchamp appeared to be coming back full circle to the nude, no longer as an abstract representation but as a grossly literal one.

Duchamp's rapid abandonment not just of painting but of conventional art, and his subsequent return to works that mimic art but are not readily classifiable as such, raise significant questions regarding his paradoxical renunciation of and consistent dependence on pictorial and artistic conventions. How is it possible to abandon both painting and traditional art, while continuing to evoke and strategically draw upon them? Duchamp's deliberate focus on reproduction, on the literal transposition or translation of a previously defined corpus, represents a literal pun on the task of painting to reproduce nature. To the extent that Duchamp's work relies on conventional painting, it displaces its priority by undermining it through reproduction. As Duchamp suggests, reproduction dispenses with the originality of painting, substituting for it the playful verisimilitude of the facsimile: "Instead of painting something it was—use a reproduction of those paintings that I loved so much, into a small reducedform, in a small shape, and—how to do it—I thought of a book which I didn't like so— I thought of the idea of a box."[3] Duchamp draws on the idea of painting only to reinterpret its mimetic impulse literally as mechanical reproduction. This literal play on painting generates a new kind of artwork, whose meaning as a facsimile undermines the logic of originality. Duchamp challenges the dependence of copies on originals by demonstrating that originals are multiples of sorts, to the extent that they embody an assemblage of already determined gestures and conventions. Displacing the priority of both the artwork and the intervention of the hand with the facsimile, whose reproduction is associated with laborious, time-consuming techniques, Duchamp redefines art by questioning its conditions of production.

Even when it seems that Duchamp is returning to a more conventional understanding of reproduction, works such as Given, by their hyperrealistic and contrived character, parody the notion of artistic reference. Thus, while appearing to return to legitimate works of art, Duchamp succeeds in questioning the legitimacy of art as a mimetic medium.

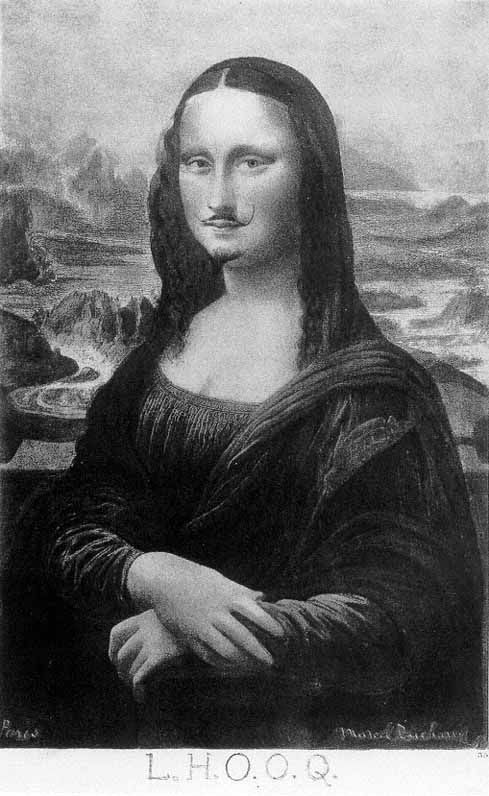

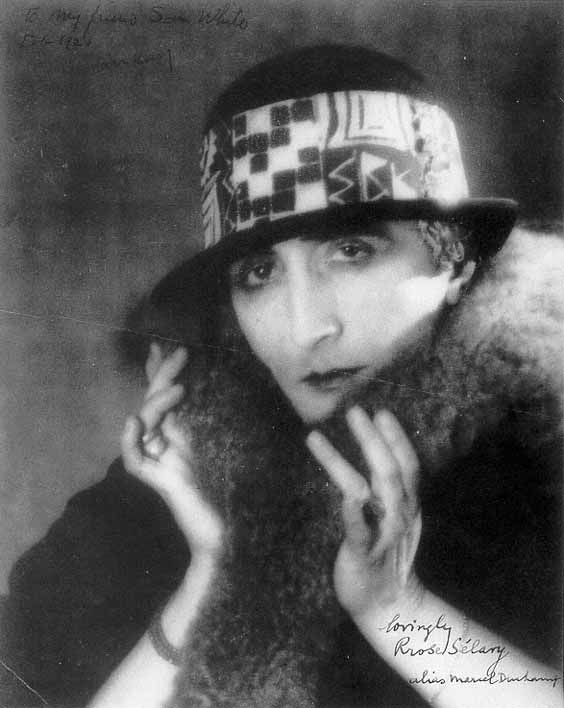

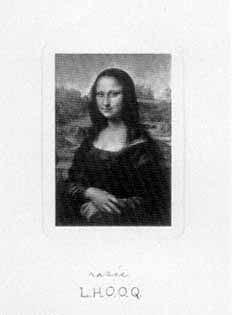

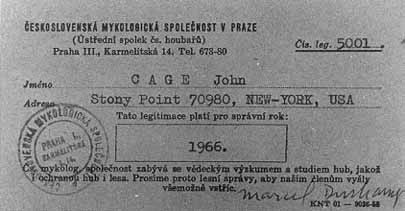

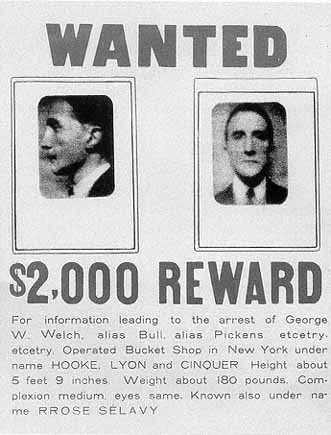

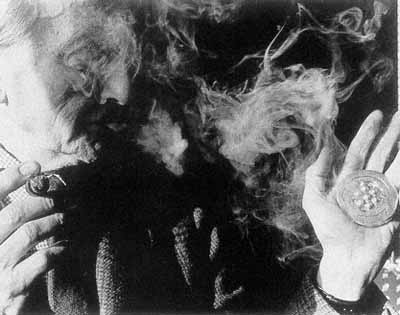

Rather than accepting the traditional labels of art and the artist, Duchamp proceeds to systematically challenge these definitions. Reacting against Romantic ideology that isolates the artist from the social and economic sphere and singles out art as a unique form of expression, Duchamp redefines the artist as a maker, rather than a creator. This is not because Duchamp denies the powers of either inspiration or creativity but because he recognizes that any creative act is embedded in a set of conventions and expectations that predetermine its outcome. If Duchamp appropriates the notion of mechanical reproduction in order to redefine artistic creativity, this is neither for lack of inspiration nor for having run out of ideas for making new works. Rather, as I suggested earlier, mechanical reproduction becomes the paradigm for a new way of thinking about artistic production, one that recognizes that creativity operates in a field of givens, of ready-made rules. By understanding the creative act in context, Duchamp redefines its meaning as a strategic intervention that derives its significance from its plasticity, its ability to generate new meanings by drawing upon already given terms. For the spectator completes the picture, as it were, interpretatively unpacking the work through the interplay of visual and verbal puns. From this perspective, originality emerges as a multiple gesture, one that generates, in turn, the illusion of multiple authorship. Is it then surprising to discover Duchamp's playful use of multiple signatures and personas, as well as his reliance on the spectator as authorizing agency of his work? His evocation of Rrose Sélavy, his artistic alter ego, de-essentializes the creative act through a plurality of personas that undermines the notion of authorship. Just as the notion of artistic production is redefined through reproduction, so does authorship reproduce and proliferate according to a generative model that disrupts both the identity of the artist and the artist's proprietary relations to his/her works.

Duchamp, however, is not content to revolutionize the notion of artistic identity or the identity of the artwork. His efforts to question the

generic distinctions that separate various artistic domains coincide with his attempts to question gender. The attempt to explore issues of genre coincides with the effort to rethink the notion of gender by destabilizing it referentially and de-essentializing it. Throughout his career, starting with Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1 (Nu descendant un escalier, no. 1; 1911) and culminating in Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas, Duchamp keeps returning to the nude in order to question its premises as a pictorial and artistic genre. Rather than perpetuating traditional representations of nudity by automatically associating it with femininity and the removal of garments, he begins to treat the nude as a symptom of the problems embodied in pictorial representation in general. At issue is the reliance of pictorial representation on its visual, rather than intellectual, impact; hence the emphasis on spectatorship as voyeurism, on visual fascination and seduction. Duchamp, however, is concerned with exploring the conceptual aspects of pictorial representation, with its conditions of possibility not merely as a visual medium but as a philosophical and institutional construct. Given the erosion of the traditional mimetic role of painting by mechanical reproduction and the emergence of new media, such as photography and cinema, which incorporate technological developments, it is not surprising to note Duchamp's desire to rethink the function and the representational modes that define painting and sculpture, and by extension, art in general. While other modernist movements such as Cubism and Futurism turn to abstraction as a way of responding to social and technological changes, Duchamp turns to a conceptual investigation of the meaning and function of art. The technical precision and methodical nature of his interventions stand in contrast to contemporary Dadaist and Surrealist efforts to radicalize art through chance operations. Chance in Duchamp's work is grounded in a field of preestablished determinations, so that its plasticity emerges from its strategic deployment and recontextualization.

Following the trajectory of the lines of inquiry outlined above, on the one hand, this book unpacks Duchamp's works by focusing on the persistence of the nude as a pictorial genre as it passes from figuration to abstraction, through its generic decomposition and transposition in The Large Glass and its belated figurative reassemblage in Given. On the other hand, it underlines the fact that Duchamp's representations of gen-

der invariably involve a generic crossover into different artistic media. It is important to note that from its inception in Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1, the representation of the nude is staged in the context of a series, indicating the incipient redefinition of notions of artistic production through the logic of the multiple. Before stumbling on the discovery of the ready-mades, Duchamp elaborates the nude as a transitive genre whose logic is in the order of reproducibility. Having begun to strip not the nude but the pictorial conventions that define it, in The Large Glass Duchamp goes on to strip art bare. He does not do so by leaving art behind but rather he draws upon it, restaging it in a manner that postpones its pictorial becoming. Playing on mimesis, a definition of art as a copy of nature, Duchamp generates copies of art that through reproduction undermine notions of artistic intent. Despite the seemingly disparate nature of such works as The Large Glass, the ready-mades, The Box in a Valise, and Given, they all represent Duchamp's strategic interpretation of art as an assemblage whose productive logic is reproductive. These works are staged compendia of generic conventions that enable Duchamp to test the boundaries of art by exceeding and, therefore, postponing its artistic intent. Thus, the structure of this book unfolds like a box, around the above-mentioned works as its organizing hinges. Whereas The Large Glass and the ready-mades hold up a mirror to painting and sculpture by de-realizing their artistic import, The Box in a Valise and Given by their mirrorical return to figurality unhinge art by reproducing and objectifying its generic conventions.

In chapter 1, the focus is on Duchamp's ostensible abandonment of painting and his challenge of its generic and conceptual limits. I argue that instead of relying on the notion of pictorial image and the conventions of painting, Duchamp redefines them both by rethinking them through other media, such as engraving and cartooning. As a mode of mechanical reproduction, engraving enables Duchamp to conceive the visual image in new terms—not as a unique entity but as a series of imprints whose temporal structure acts to delay the retinal impact of the image. The technology of engraving and printing as media of mechanical reproduction becomes the source for intellectual insights that Duchamp deploys to redefine the identity and immediacy of the visual image. As a graphic and linguistic medium, cartooning enables Duchamp to redefine

the visual image in conceptual terms as the interplay of visual and verbal puns. If titles are significant in Duchamp's works, this is because they no longer function as mere captions or labels but instead as devices that reframe the retinal impact of images in terms of poetic or punning associations. The visual opacity of the Large Glass attests to Duchamp's successful displacement of meaning away from the retinal and toward its active interplay with linguistic and poetic frames of reference. A reassemblage that reproduces his previous pictorial works on glass, the Large Glass makes manifest the recognition of the ready-made character of pictorial representation.

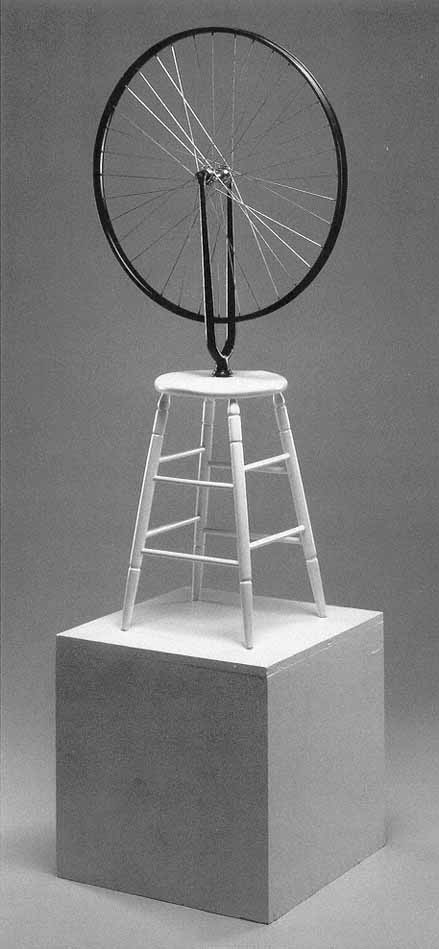

In chapters 2 and 3, Duchamp's work speaks eloquently and decisively about art as an institution, as a system for packaging and framing various objects and gestures. Exhibiting mass-produced objects as art objects, Duchamp exposes the conditions of possibility of art through the readymades. Rather than postulating art as an expression of the object, of its formal and material qualities, Duchamp uncovers the fact that art inheres less in an object than in the institutional context that frames it and makes it legible. The ready-mades make visible the provisional and transitional status of art as they switch back and forth, undecidably, between art and nonart. By documenting this transition, Duchamp demystifies the art object at the same time that he reactivates the position of the spectator, as critical to both the reception and production of works of art.

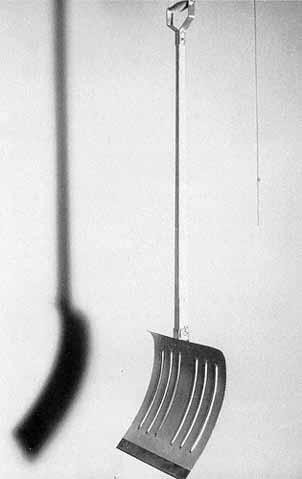

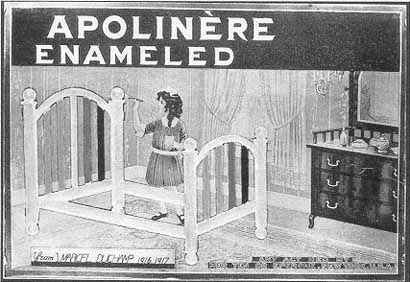

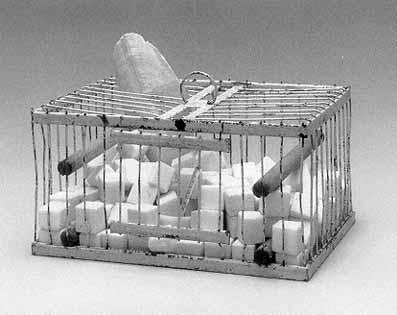

Rather than being restricted to the ready-mades as objects or gestures, this study seeks to inquire into their nominal properties. While certain ready-mades are named according to the object they ostensibly represent (the bicycle wheel, for instance), other objects bear titles that appear to be totally unrelated to them (the snow shovel is entitled In Advance of the Broken Arm [En avance du bras cassé; 1915]). I argue that the legibility of the ready-mades relies not merely on their visual appearance but on their nominal properties, since their titles pack in networks of puns and poetic associations. As literal reproductions of objects, the ready-mades become legible as puns, as relays of signification, as switches that enable the spectator to discover mechanically the creative potential of language. Just as mechanical reproduction ensures the production of commercial prototypes, so do linguistic and social conventions ensure the production and circulation of puns. Culturally generated and reproduced, puns func-

tion as vehicles of individual expression only insofar as they embody shared forms of common or poetic usage. Duchamp's ready-mades make us stumble on the surprising discovery that linguistic puns are also ready-mades; that is, they are mechanisms whose venues for generating meaning are technically spelled out in the dictionary. The legibility of Duchamp's puns thus depends less on the spectator's imagination than on his or her ability to reactivate the puns by becoming aware and engaging with their potential meanings. In this context the dictionary becomes a technical manual of sorts that makes visible the conceptual subtext that underlies the visual and nominal appearance of the ready-mades. Unfolding Duchamp's ready-mades as three-dimensional puns requires concerted attention to the interplay of language and image, as each system of reference intervenes to generate or undermine the production of meaning. Unpacking Duchamp's ready-mades, therefore, refers less to the handling of objects proper than to theunderstanding of the way they function as utterances in context. As bearers of speech or cultural mouthpieces, the ready-mades capture the dilemma of an art that postpones its pictorial becoming and thus the finality of its attainment to become art.

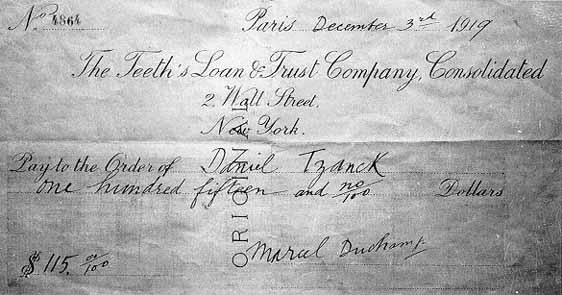

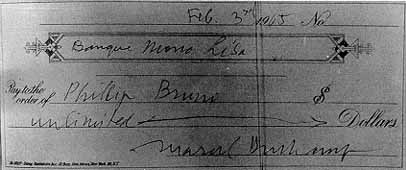

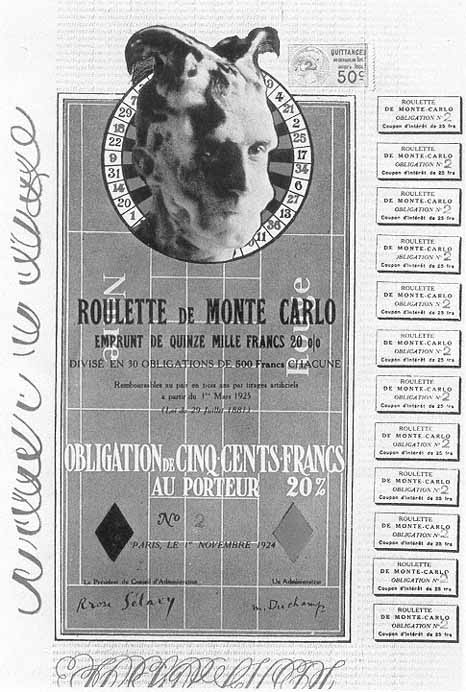

As the "plastic equivalent of a pun" (to use Octavio Paz's terms), the ready-made stages the gratuitous conversion of an ordinary object into a work of art, while undermining through this very gesture the notion of an art object. Chapter 4 is an examination of how the ready-made functions as a critique of classical notions of value. Instead of assuming the autonomy of art from the social and economic sphere, the focus is on how Duchamp rethinks the question of artistic value by redefining it as a function of its economic and social currency. Instead of condemning Duchamp's forays into commercial ventures in art, I argue that Duchamp is redefining art according to a speculative model, whose conceptual implications liberally draw upon and expend classical economics. Ranging from checks and bonds to numismatic coins, Duchamp's artworks mimic economic currency and exchange only to undermine the notion of both artistic and monetary standards. These works redefine artistic and economic forms of production byexploiting the speculative potential of reproduction.

This study concludes with an examination of Duchamp's posthumously exhibited work Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas, a work

that, like his earlier The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even and The Box in a Valise, is a compilation of his previous works. Described as "startlingly gross and amateurish," Given "startles" by mirroring back the spectator's look.[4] The violence of this work appears to lie less in its deliberate exhibitionism and voyeurism than in the fact that the spectator is put face-to-face with his or her desire to look, to be fascinated, and to consume sexuality as an image. In the context of the museum where everything is on display, however, the display of sexuality takes on an ironic tone. Having questioned the logic of the visible, does Duchamp's Given represent a continued challenge or a return to conventional modes of representation? I argue that despite this work's oven sexual display, or rather, because of its exaggeration as display, the equation of sexuality and vision is sundered. Duchamp undermines the logic of voyeurism by questioning the coincidence of sight with visual pleasure. In doing so he moves away from equating sexuality with anatomical destiny, toward redefining it as a rhetorical operation. However, this effort to de-essentialize gender can be understood only in the framework of his attempts to experiment with genre. Just as Given fails to provide the spectator with a stable representation of sexuality, so does it also resist any generic classification. Given is an installation, an assemblage of works that mimic artistic media such as painting, sculpture, and photography, without being reducible to a specific genre. The generic identity of this work, like the status of gender, remains transitive, resisting both fixity and closure.

If Duchamp's works resist canonization, this is not simply because of their complexity or enigmatic character but rather because his works are by definition transitive. They are like hinges, straddling the gap between vision and language, art and nonart, forms of artistic production and reproduction. Resembling Duchamp's elusive presence as an artist, his works are packages whose meaning continues to unfold in new and surprising ways. In the postscript is a brief assessment of Duchamp's impact on the history of Modernism. His redefinition of artistic modes of production through reproduction opens up the scope of Modernism to a notion of artistic production that is speculative, insofar as it reinvests rather than liquidates the legacy of tradition. In doing so, Duchamp discovers within the experimental scope of Modernism a conceptual potential that becomes the terrain for the emergence of postmodernism. Having done away with

the classical categories that define the artist, the creative act, and the artwork, Duchamp opens up the horizons of Modernism to speculative explorations, to forms of appropriation that postpone the fate of Modernism, its exhaustion through novelty. Just as Duchamp draws upon pictorial conventions to redefine the meaning of art, so does the legacy of his work open itself to appropriation by others. Is it then surprising to see artists such as J. S. G. Boggs issuing bogus bills on Duchamp's pseudoartistic/financial transactions? Boggs's postmodern appropriation realizes a potential inscribed in Duchamp's postponed legacy of Modernism. If Duchamp's artistic life and his works are on credit, this credit can continue to be reinvested or spent. The possibilities are unlimited, since, as Duchamp reminds us, "Posterity is a form of the spectator" (DMD, 76).

1—

Painting at a Dead End

The rest of them were artists. Duchamp collects dust.

—John Cage

Among Marcel Duchamp's gestures and artistic interventions, few have created as much controversy or been as puzzling as his putative abandonment of painting.[1] Duchamp begins painting at fifteen, producing a series of competent, if not particularly distinguished, landscapes and portraits, which he qualifies as "pseudo-Impressionist" or "misdirected Impressionism" (DMD, 22). Although Duchamp starts to exhibit his work publicly in 1909, the earliest works of his that are considered significant date to 1910. At the age of twenty-three, his enriched pictorial and compositional vocabulary is deployed in a figurative context, where nudes and group scenes dominate. Reflecting the influence of Paul Cézanne and the Fauvists, the emphatic use of color and design in these works represents a decisive turn toward abstraction. Robert Lebel compares their "acid stridence to that of Van Dongen, and also, German Expressionism" (DMD , 23). By 1911, Duchamp's use of abstraction demonstrates shared affinities with Cubism, insofar as it brings into question the figurative identity of the body through its spatial fragmentation and its serial deployment. At this time he also begins to expand the meaning of the pictorial image by trying to find new ways of illuminating it, either through experiments with gaslight or by exploring how the title may have an impact on the nominal expectations of painting.

At the end of 1911 and culminating in 1912, Duchamp irrevocably establishes his authority as a painter through his signatory work, Nude

Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which is first rejected by the Salon des Indépendants in March, only to be exhibited in Barcelona in May. In late 1912, this work is chosen by Walter Pach to be included in the upcoming International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York (the Armory Show of 1913). It is during this same period that Duchamp begins to incorporate machine imagery and morphology in his paintings, leading to his mechanomorphic paintings. This three-year trajectory that establishes Duchamp's creative identity and credibility as a painter renders his abandonment in 1913 of conventional painting and drawing all the more surprising, if not altogether shocking. At issue is neither Duchamp's failure nor, ironically, his success as a painter but rather his challenge of the limits of pictorial practice.[2] The fact that in 1916 a New York art dealer named Knoedler, after seeing Nude Descending a Staircase, offered Duchamp $10,000 a year for his "entire production" (DMD , 106), alerts us to Duchamp's painterly reputation and financial worth in the nascent New York art world.[3] Duchamp's refusal of this offer at a time when his financial means were limited all the more decisively underscores his choice to move beyond painting in order to challenge the social and institutional conventions that define both pictorial production and the painter.

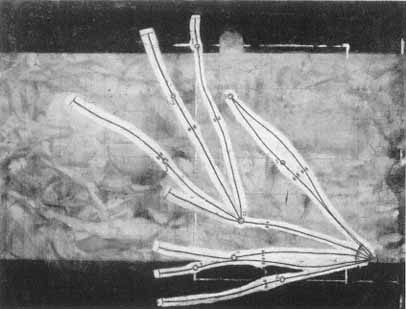

Thus within this three-year span (1910–13), Duchamp establishes himself as an internationally renowned painter, one who moves decisively from figuration to abstraction, only to begin to question painting altogether. In 1913 Duchamp practically gives up conventional forms of painting, but this does not mean that he stops working. Instead, he begins to experiment with chance as a way of getting away from the traditional methods of expression generally associated with art. He lets pieces of string fall and records the shapes they generate; when his work on glass cracks he accepts the cracks as part of the work.[4] These chance-generated works challenge the position of the artist as autonomous producer and the determinism that defines art as a creative medium. During this period, Duchamp experiments with mechanical drawings, painted renderings, and notations that serve as studies for his seminal work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even.

By 1923, the idea that Duchamp did not just give up painting but art altogether comes into currency. As Joseph Masheck explains: "Duchamp never discouraged it and seems to have enjoyed the mysterious notoriety

that it gave him as well as the silent isolation to carry on his activities out of the limelight. Duchamp was said to have taken up a decided antiart position, abandoning art in favor of playing chess."[5] Thus, from Duchamp's supposed abandonment of painting we arrive (through The Large Glass, which, as I argue, is also a looking glass) at the far more radical conclusion that Duchamp has reneged on art altogether, that he has abandoned art in favor of chess. How do we explain these radical transitions, from figuration to abstraction leading to the abandonment of painting, and ultimately art, given the speed at which these gestures succeed one another? Can these transitions be illuminated by particular events in Duchamp's life, and more specifically, how are they manifest when considering works from this period?[6] Are there conditions or strategies evidenced in these works that dictate a radical revaluation of painting both as artistic practice and as profession?

A small number of biographical details may prove to be significant to our discussion of Duchamp's pictorial origins. Born in a solid French bourgeois family on 28 July 1887 and following in the footsteps of his two brothers Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon and his sister Suzanne, Duchamp also became interested in art.[7] It should be noted, however, that the initial disapproval expressed by his father regarding an artist's career for his sons led his elder brothers to change their names by assuming a pseudonym (Villon, after the renowned medieval French poet François Villon [1431-after 1463]) or partial pseudonym (Duchamp-Villon).[8] Despite the paternal reluctance to endorse the professional choices of his sons and despite the age differences among the siblings, the entire family was deeply steeped in their shared interests in music, art, and literature.[9] It is important to recall, however, that Duchamp's formal art training was limited to one year of studies at the Académie Julien, from 1904 to 1905. Far more significant in his professional formation was his apprenticeship as a printer in Rouen in 1905, in lieu of doing military service. As an "art worker" he received exemption from military service after one year, having passed a juried exam based on the reprints of his grandfather's engravings. From 1905 to 1910, following the example of his brother Jacques Villon, he executed cartoons for two newspapers, the Courier Français and Le Rire. Thus, in addition to his early exposure and family background in art, both engraving and cartooning

were formative media to his development as painter.

The influence of Duchamp's exposure to engraving and cartooning impacted on his efforts to discover alternative ways of conceiving painting and art. Unlike his siblings, Duchamp is not content to simply become a painter, for he will rapidly abandon painting in favor of activities that challenge the very meaning and definition of art. When one considers attentively Duchamp's early works, one is invariably struck by his efforts to put into question the notion of pictorial image, by examining its relation to other frames of reference, the title, or the nominal expectations of the public. Moreover, his early explorations of serial works, or multiples, attest to his efforts to challenge the uniqueness and autonomy of the pictorial image. Engraving and cartooning thus enabled Duchamp to conceive the plastic image in new terms, whose technical and intellectual content opened up the possibility of redefining the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production based on reproduction. Duchamp did not becomean engraver nor a cartoonist. He did, however, draw on the intellectual and speculative potential of these two media, in order to redefine not only painting as a medium but also art itself. The fact that Duchamp began his artistic career as an "art worker" is significant, insofar as it enabled Duchamp to question the creative function of the artist and the meaning of art as a form of making:

I don't believe in the creative function of the artist. He's a man like any other. It's his job to do certain things, but the businessman does certain things also, you understand? On the other hand the word "art" interests me very much. If it comes from the Sanskrit, as I've heard, it signifies "making." Now everyone makes something, and those who make things on a canvas, with a frame, they're called artists. Formerly, they were called craftsmen, a term I prefer. We're all craftsmen, in civilian or military life. (DMD, 16).

In the pages that follow, Duchamp's effort to question the meaning of art as pictorial practice, as an institution, and as a profession will be at issue. The notion of art as "making" enlarges the meaning of artistic activity to forms of production that include not only artisanal efforts but also conceptual insights.

Painting Stripped Bare

I have been a little like Gertrude Stein

—Marcel Duchamp

In his interview with Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Cabanne asks him to explain the key event of his life: his abandonment of painting. Duchamp's response identifies Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 as the turning point. While serving to establish his reputation, the initial rejection of the work alerts him to the norms and strictures that define not just conventional art but also contemporary art movements, such as Cubism:

There was an incident, in 1912, which "gave me a turn," so to speak; when I brought the "Nude Descending a Staircase" to the Indépendants, and they asked me to withdraw it before the opening. In the most advanced group of the period, certain people had extraordinary qualms, a sort of fear! People like Gleizes, who were, nevertheless, extremely intelligent, found this "Nude" wasn't in the line that they had predicted. Cubism had lasted two or three years, and they already had an absolutely clear, dogmatic line on it, foreseeing everything that might happen. (DMD , 17)

Duchamp is less concerned with the rejection of the painting than the fact it embodies a doctrinal gesture—one where a work of art is defined by living up to its nominal expectations. By failing to fall into line, that is to conform to a set of pregiven rules, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was perceived as a challenge to Cubism, whose precepts had already been laid out by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. For Duchamp, the turning point that the Nude represents is not merely its challenge to the public but also to his peers, whose artistic and intellectual expectations define the work's conditions of possibility. For Duchamp this incident was symptomatic of the dogmatic, programmatic character of art, and led him to abandon both painting and the artistic milieus he frequented, in favor of a job as a librarian at Sainte-Geneviève Library in Paris.

Was Duchamp's dramatic gesture an expression of his "distrust of systematization," of his inability to contain himself to "accept established formulas" (DMD , 26)? Duchamp rejects Cubism not just as an artistic movement but as a discipline with a set aesthetic program: "Now, we have a lot of little Cubists, monkeys following the motion of a leader

without comprehension of their significance. Their favorite word is discipline. It means everything to them and nothing."[10] Duchamp deliberately distances himself from the aesthetic agendas of Cubism, since his aim is to "detheorize Cubism in order to give it a freer interpretation" (DMD , 28).[11] If this is true, then one must examine in what sense Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 challenges preestablished Cubist pictorial and generic formulas. Coming in the wake of a series of representational nudes in 1910, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 marks Duchamp's decisive turn from figuration to abstraction. As this study will demonstrate, however, Duchamp's passage through abstraction involves the speculative goal of getting away from "the physical aspect of painting" by putting "painting once again to the service of the mind."[12] As Arturo Schwarz observes, Duchamp's aim was to liberate the notion of painting from its aesthetic function to please the eye, in order to reassess its intellectual potential.[13] Duchamp's efforts to expand the horizons of painting, by exploring the literal and nominal expectations that define it, led to his subsequent abandonment of the medium.

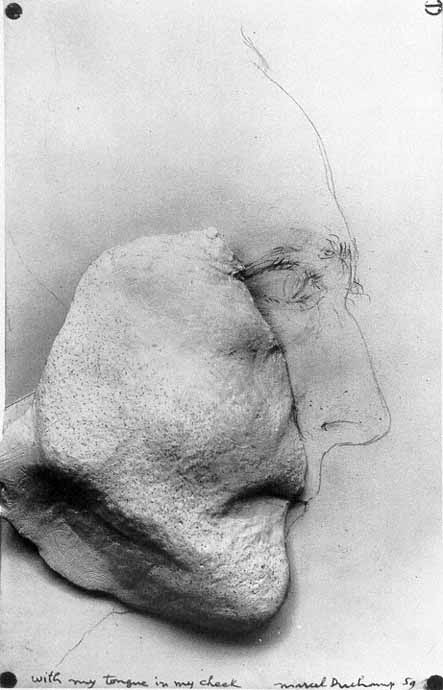

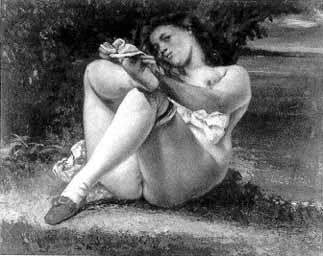

Duchamp's adoption of the nude as pictorial genre did not have entirely auspicious beginnings. It is also interesting to recall that he failed the Ecole des Beaux-Arts competition over a test that involved doing a nude in charcoal (DMD , 21). In 1910, when Duchamp turns to the genre of the nude

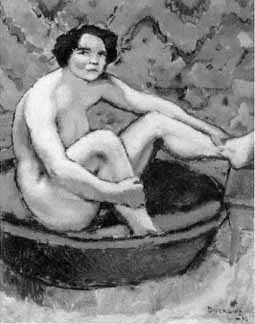

Fig. 1.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Seated in a Bathtub (Nu

Assis Dans Une Bagnoire), 1910. Oil on canvas,

36 1/4 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

after extensive work in landscape and portraiture, his explorations of this subject matter reveal an acute awareness of pictorial traditions and contemporary artistic movements and styles. Schwarz notes that in Nude with Black Stockings (Nu aux bas noirs; 1910), the "use of heavy black lines—characteristic of the Fauves' reaction to the Impressionists' careful avoidance of black—is freely adopted."[14] Duchamp's deliberate deployment of one of the signatory gestures of Fauvism, which is itself a reaction to the aesthetic ideology of Impressionism, suggests his recognition of the plastic and strategic character of artistic conventions. It reflects an understanding of the extent to which an artistic movement may be defined by its strategic response to the aesthetic tenets of a previous, or even contemporary, movement. Duchamp's use of heavy black lines to outline the body, as in Nude Seated in a Bathtub (Nu assis dans une bagnoire; 1910) (fig. 1), Nude withBlack Stockings (fig. 2), and Red Nude (Nu rouge; 1910) (fig. 3), establishes a tension between the rhetoric of drawing and that of color. The black lines emphatically reframe the successive color shadings, thus

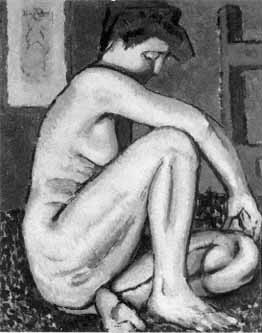

Fig. 2.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude with Black Stockings (Nu

Aux Bas Noirs), 1910. Oil on canvas, 45 3/4 x 35 1/8 in.

Galleria Schwarz, Milan. Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

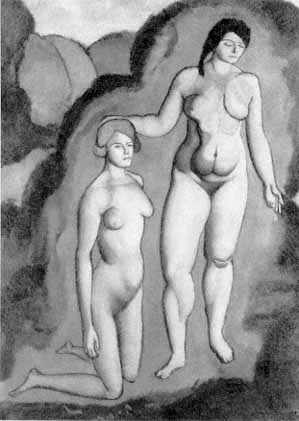

Fig. 3.

Marcel Duchamp, Red Nude (Nu Rouge), 1910. Oil

on canvas, 36 1/4 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

inscribing a graphic dimension into the painterly impact of these works. In the Red Nude, color as one of the constitutive elements of painting is deployed in a manner that reveals its affinity to engraving. The red shadings and black lines compete as color templates that redefine the pictorial appearance of the nude as a successive set of impressions or imprints.

If these nudes are graphic, it is in their treatment of painting and not in their ostensible subject matter. When comparing Duchamp's Nude with Black Stockings with Gustave Courbet's Woman with White Stockings (Femme aux bas blancs; 1861), one is struck by its unerotic demeanor that resists voyeuristic appropriation as an image. Rather than emphasizing and framing genitality, as the white stockings do in Courbet's painting, the black stockings dismember the body by erasing it from the

Fig. 4.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bush (Le Buisson), 1910. Oil on

canvas, 50 x 36 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and

Walter Arensberg Collection.

knees down. Duchamp's cropping of the nude body displaces the viewer's attention from the frontality of sex to the pictorial frame that cuts the body off—a feature shared by other works, such as Two Nudes (Deux Nus; 1910), and Red Nude. The effort to draw the spectator's attention to framing devices is deliberately underlined in Red Nude , where the profile of the crouching red nude breaking out of the frame of the painting also cuts into the frame of another painting. Located in the upper lefthand corner of the image, this painting is further disfigured by the painter's signature cutting across the head of a female figure. The authorial signature is displaced into a position where its nominal content interferes with the visual content and consumption of the image. Rather than merely stripping the nude, Duchamp begins to strip away the visual conventions that define the nude as a pictorial genre.

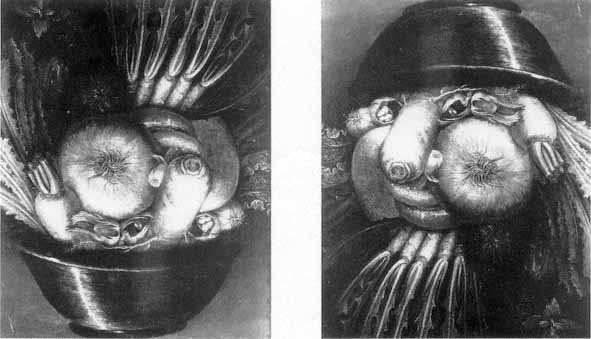

By 1910, Duchamp's exploration of the nude enters a new phase, one where issues of pictorial abstraction are reframed by their interplay with nominal expectations triggered by the title. Loosely identified as his "Symbolist" phase because of its visual affinities to the works of Paul Gauguin and Pierre Girieud, Duchamp's works betray the Symbolist conceit of combining word and image.[15] Duchamp challenges notions of visual and verbal reference by playing them against each other through puns. The doubling of female nudes in The Bush (Le Buisson ; 1910) (fig. 4) and in Baptism (1911) is underlined by framing of the figures by a shrublike halo, an aura that conflates their physical outline with the landscape that surrounds them. For Lawrence Steefel, The Bush "seems to point towards the ultimate goal of turning the world inside out."[16] This doubling and melding of background and bodily composition can be seen as a pun on the painting's title, The Bush , which nominally makes available the sexual referent that is traditionally dissimulated or visually veiled in the representation of nudity. Duchamp trivializes the visual referent by his puns on the title "bush," thereby defying the nominal expectations of the spectator as voyeur. In Paradise (Le Paradis; 1910) (fig. 5) the abject representation of the male and female nudes challenges the promissory tone of the title. There is no illumination nor spiritual "Ascension" here. The title Paradise contradicts the viewer's expectations, unless it is interpreted literally, as a pun on the French word paradis, which means no radiance, to be struck out, canceled, or just broken. The lack of radiance in Paradise

Fig. 5.

Marcel Duchamp, Paradise (Le Paradis), 1910. Oil on

canvas, 45 1/8 x 50 1/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

may reflect the fact that Symbolism as a pictorial style, rather than the painting's subject matter, has reached exhaustion.

While Duchamp admits in his interview with Cabanne: "I don't know where I had been to pick up on this hieratic business" (DMD , 23), this statement should not discourage us from considering this question. This halo effect or aura can be found in another work of this period entitled Portrait of Dr. R. Dumouchel (Portrait du Dr. R. Dumouchel; 1910) (fig. 6), where a nimbus surrounds the upper torso of the figure and, especially, the hands. Referring to this painting, Duchamp wrote in a letter to his patrons Louise and Walter Arensberg: "The portrait is very colorful (red and green) and has a note of humor which indicated my future direction to abandon mere retinal painting."[17] The note of humor that Duchamp evokes here may be a reference to the painting's caption "à propos de ta 'figure' mon cher Dumouchel" (loosely translated as, "by way of your 'appearance' my dear Dumouchel"). The word figure means figure, shape, or form, but its use by Duchamp suggests that it refers to Dumouchel's appearance: it is a reflection on the way he looks, his "air," or "aura." The colorful nature of this painting, its red and green colors, is a pun on color blindness. This pun on color blindness in the context of painting foreshadows, as it were, Duchamp's denunciation and subsequent aban-

donment of retinal painting. For Duchamp, the hieratic aura associated with Symbolist painting becomes the locus of investigation of the interplay of word and image, not under the guise of symbols but as puns.

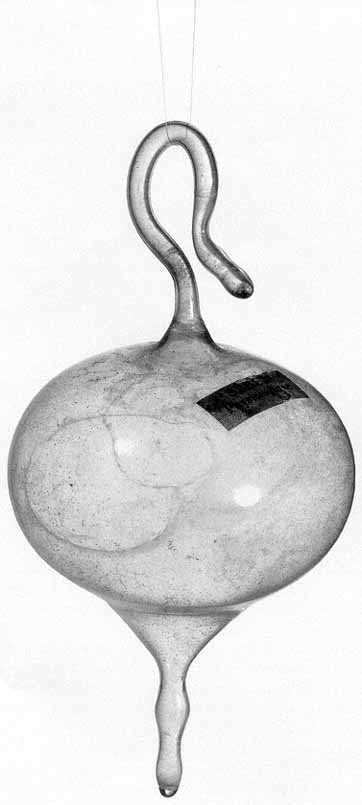

This "halo" effect or aura continues to reappear throughout Duchamp's works, either as an analogy to smell (in such works as Fountain [1917] and Beautiful Breath, Veil Water [Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette; 1921]), or as an analogy for electricity (in Bec Auer [a gas lamp circa 1902]; The Large Glass [1915–23]; Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas (1946–66); and in a set of prints entitled The Bec Auer [1968]).[18] The word "aura" (in Greek, breeze or breath) signifies an influence or emanation issuing from the human body, although invisible to ordinary eyes and surrounding it as an atmosphere.[19] In Duchamp's later works the "aura" is deployed as a critique of painting as a visual event, in

Fig. 6.

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Dr. R. Dumouchel (Portrait Du

Dr. R. Dumouchel), 1910. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 25 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

order to recover its intellectual potential. Considered from this perspective, Duchamp's early experiments with the hieratic can be understood as an allusion to the history of painting. This was at a time when the appearance of the nude, like painting itself, attained value by virtue of its religious, philosophical, and moral function, and was thus in excess of visual semblance. If painting exuded an "aura," this is because its significance was originally defined by its social rather than cultural function. The loss of painting's "aura" in the age of mechanical reproduction heralds the end of painting as a purely manual and visual event and its conceptual rebirth as a practice stripped of the hallowed echoes of visual semblance.[20] Duchamp's antiretinal stance reflects his effort to expand the meaning of painting by returning to a historical understanding of painting that takes into account its functional role. As Duchamp explains to Cabanne:

Since Courbet, it's been believed that painting is addressed to the retina. That was everyone's error. The retinal shudder! Before, painting had other functions: it could be religious, philosophical, moral. If I had the chance to take an antiretinal attitude, it unfortunately hasn't changed much; our whole century is completely retinal, except for the Surrealists, who tried to go outside it somewhat. And still, they didn't go so far! (DMD , 43)

In this context, painting is redefined: it is considered no longer merely visual/erotic stimulation but also conceptual intervention.

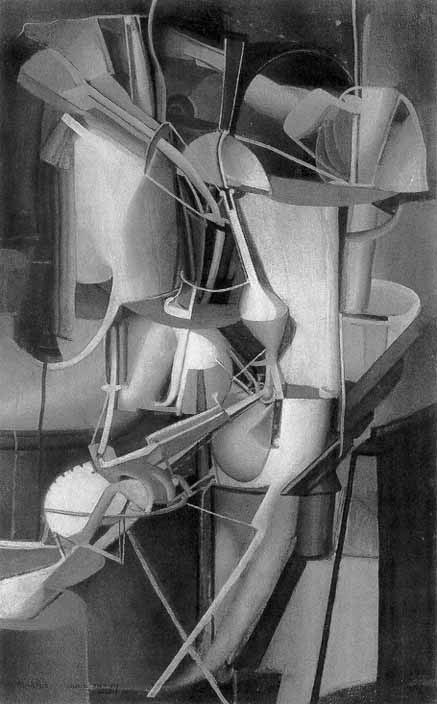

If Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (fig. 7) scandalized both the critics and the public alike, this is because it challenged the nominal expectations of the viewer more than any of Duchamp's previous works. Its rejection by the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, and the public furor occasioned by its exhibition at the New York Armory Show in 1913, are a barometer of the painting's transgressive character. Described as an "explosion in a shingle factory," Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was further humored by a cartoon depiction entitled Rude Descending a Staircase. The word rude appropriately captures the impact of the Nude, its deliberate disregard for the artistic conventions of the genre. This work scandalized not only the general public but also the avant-garde circles of the time. Duchamp withdrew his work from the Salon des Indépendants

Fig. 7.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Nu Descendant Un Escalier,

No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 35 1/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

by refusing to comply with Metzinger's and Gleizes's request to change the title because it was too "literary," in a caricatural sense. As Duchamp explains, the title plays a significant role in explaining the particular interest and impact of this work:

What contributed to the interest provoked by the canvas was its title. One just doesn't do a nude woman coming down the stairs, that's ridiculous. It doesn't seem ridiculous now, because it's been talked about so much, but when it was new, it seemed scandalous. A nude should be respected . (DMD, 44; emphasis added)

Duchamp's comments indicate that the reception of this painting was being filtered through a set of expectations, whose nominal character was staged by the title. The abstract nature of this work and thus its failure to provide a visual referent for the title only increased the public's disappointment. Nude. . . No. 2 presents a clash of nominal and visual expectations that are the expression of the history and conventions of painting. Instead of reclining passively, Duchamp's fractured nude is actively descending a staircase. The scandal surrounding the exhibition of Nude. . . No. 2 thus reflects the destruction of the nude as traditional subject matter of painting. In his book The Nude, Kenneth Clark maintains that the nude is not the starting point of a painting but a way of seeing that the painting achieves.[21] The nude embodies a set of representational strategies that imply a particular relation between the spectator and the spectacle of the body reduced toan image on display. Constructed as the subject of desire from the Renaissance to the late nineteenth century, the nude as a pictorial genre involves a structure of spectatorship that relies upon the objectification of the female body. This interplay of visual and nominal expectations staged by the nude as a pictorial genre was put into question by painters such as Edouard Manet, who in Olympia (1863) and Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe (1862–63) challenged the inscription of the desiring look of the spectator.[22] Moving away from figuration into abstraction, Duchamp's Nude. . . No. 2 further challenges this congruence of visual, nominal, and generic expectations.

The Nude. . . No. 2 reduces the anatomical nude to a series of successively fractured volumes: "Painted, as it is, in severe wood colors, the

anatomical nude does not exist, or at least cannot be seen, since I discarded completely the naturalistic appearance of a nude, keeping only the abstract lines of some twenty different static positions in the successive action of descending."[23] The renunciation of the naturalistic appearance of the nude in favor of its twenty positions in the successive act of descent reflects Duchamp's radical critique of painting through chronophotographic freeze-frame techniques.[24] What is at issue here is a challenge of the pictorial medium through sequential photography: a critique of vision as a cognitive medium that conflates spectatorship and pleasure. The splintering of vision into a series of frames that fragment and abstract both the identity of the nude and the process of movement inscribe into the painting an interval, a temporal dimension. Functioning neither descriptively nor prescriptively, the title Nude Descending a Staircase inscribes a temporal delay that interferes with the visual consumption of the image. This strategy of delay also redefines and defers notions of visual reference that are traditionally associated with photography. While appealing to techniques of mechanical reproduction, such as photography, to redefine the pictorial medium and its subject matter, Duchamp succeeds in redefining painting itself as a process whose plasticity includes temporal considerations.

Asked by Cabanne how did the painting originate, Duchamp responded:

In the nude itself. To do a nude different from the classic reclining or standing nude, and to put it into motion. There was something funny there, but it wasn't funny when I did it. Movement appeared like an argument that made me decide to do it.

In the "Nude Descending a Staircase," I wanted to create a static image of movement: movement is an abstraction, a deduction articulated within the painting, without our knowing if a real person is or isn't descending an equally real staircase. Fundamentally, movement is in the eye of the spectator, who incorporates it into the painting. (DMD, 30)

The picture presents the viewer with a "vertigo of delay," to use Paz's term, rather than one of acceleration.[25] Duchamp's interest in kinetics here is conceptual: the movement in the painting is produced through the

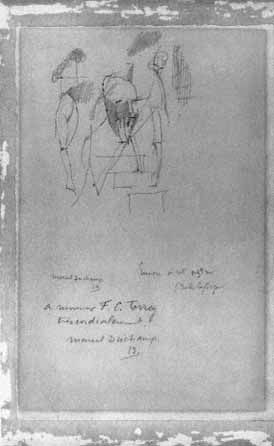

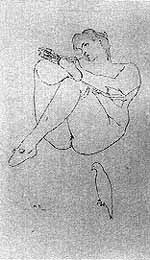

Fig. 8.

Marcel Duchamp, Once More to this Star (Encore

À Cet Astre), 1911. Pencil, 9 3/4 x 6 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

decomposition of the graphic elements. The staggered motion of the "nude" demonstrates an analysis of movement rather than the Futurist seduction with the dynamics of movement.[26] The kinetic character of the nude is not merely the thematization of movement as a pictorial fact but rather the discovery that the retinal is not an essential given but a rhetorical condition.

But why is the nude descending? This question is all the more interesting, since in its preliminary sketch Once More to This Star (Encore à cet astre; 1911) (fig. 8), based on the title of Jules Laforgue's poem, the primary figure is ascending a staircase. A network of visual puns connects Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 to Once More to This Star: instead

of ascending to a star, the star becomes a staircase for the obverse movement of descent. Duchamp explained his interest in Laforgue's poetry, particularly his prose poems Moralités Légendaires, in terms of their humor and poetic quality, as such: "It was like an exit from Symbolism" (DMD, 30). Just as Laforgue's poem denounces the idealist aspirations of Symbolist poetry by pointing out that the stellar image of the sun is undermined by its ordinary and pockmarked appearance, so does Duchamp transform the idealism that underlies pictorial praxis into a mere stair, a pun on the notion of descent understood both literally and figuratively.[27] The fact that the nude may be descending from its pedestal should be of no surprise, given that its ascension into a "genre" is ungendered by being at once sexually and pictorially redefined.

The ambiguous title of the Nude (nu, in French) gives no particular indication as to the referent's gender, although critics have identified it generically as female, de rigueur. Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 thus emerges as a critique of pictorial representation to the extent that it challenges the ideological underpinnings of the nude as a genre that is invariably femininely gendered. Unable to incarnate the nominal expectations of the spectator, the nude visually fractures the spectator's gaze by setting it into a spiraling motion. In doing so Duchamp points both to the title and to the spectator's gaze as the sites on which hinges the facticity of gender. This resistance to the equation of spectatorship with visual consumption and delectation is explicitly thematized in Duchamp's later works. In Selected Details After Courbet (Morceaux choisis d'après Courbet; 1968), for instance, the spectator's gaze is conflated with the falcon (faucon, inFrench: a pun on the facticity of sex) in the foreground, thereby revealing the role of language in the constitution of gender as sexual referent. The Nude 's descent thus functions as an index of Duchamp's strategic displacement and rethematization of the nude as a pictorial genre and its declension from the spectator's nominal expectations.

As a descendant from the lineage of painterly traditions, Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 stages both its genealogical derivation, as well as its own deviation from this ancestry. The descent of the Nude is not merely the mark of a genealogical decline but also the legal index of the passage of an estate through inheritance.[28] The Nude's

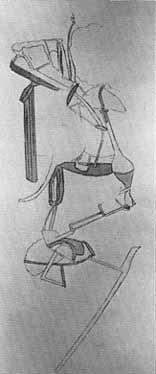

descent illuminates Duchamp's own inheritance of previous pictorial traditions and his efforts to literally draw on this heritage by reproducing it in new ways. Is it surprising then that Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the first of Duchamp's serial works, having been preceded by Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1 (Nu descendant un escalier, no. 1; 1911) (fig. 9), only to be followed by Duchamp's full-sized photographic and hand-colored facsimile entitled Nude Descending a Staircase, No.3 (Nu descendant un escalier, no.3; 1916). As Joseph Masheck notes: "Typical of Duchamp is this work's self-illustrative and self-reproductive function, as well as the fact that as an actual photograph it returns to one of the technical sources of the 'original' painting."[29] The self-illustrative and self-reproductive aspects of Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase demonstrate his efforts to redefine the notion of pictorial production, as a genealogical intervention based on reproduction.

However, this reproductive industry did not stop short with the fullsized versions of the Nude. This work was further reproduced as a miniature pencil-and-ink drawing Nude . . . No. 4 (1918) for the dollhouse of Carrie Stettheimer. This doll-sized version of the Nude was followed by further miniature reproductions in The Box in a Valise (1938–41). From a single work that is by definition a multiple, insofar as it is part of a series, Duchamp generates an entire corpus. By discovering the self-productive and self-reproductive potential of the Nude, Duchamp redefines the nude as a medium of and for reproduction. Eroticism in this context no longer refers to the visual appearance of the nude but instead functions as an index of its proliferation as modes of appearance. Duchamp challenges the eroticism traditionally associated with spectatorship and voyeurism by proposing an alternative eroticism whose speculative, technical, and humorous character restages through reproduction the notion of artistic creativity and production.

Given Duchamp's explicit rejection of the equation of vision and eroticism, how are we to explain his interest in the nude as pictorial genre? It seems that the entire trajectory of his life's work is defined by the arching movement from Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 to The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, and culminating in his testamentary work Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas. While Duchamp maintains that eroticism is the only -ism he believes in, it is

clear that eroticism for him is not linked to an anatomical or essentialist destiny but rather, like humor, it is defined through movement, as transition instead of stasis. Eroticism in the figurative arts is most commonly represented as the relationship between clothing and nudity, and thus, as Mario Perniola suggests, it is conditional on the possibility of movement or transition from one state to another.[30] For Duchamp, however, eroticism signifies conceptually and philosophically as a reflection on representation, a presentation understood in the mode of reproduction, where appearance is the result of repeated modes of impressions.

Now we begin to understand the conceptual import of both engraving and cartooning in Duchamp's work. Engraving is one of the earliest forms of mechanical reproduction that involves a different way of conceiving

Fig. 9.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1

(Nu Descendant Un Escalier, No. 1), 1911. Oil on

cardboard, 38 1/8 x 23 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and

Walter Arensberg Collection.

the plastic image. Not only is the appearance of the engraved image the result of multiple reproductions but its very identity is defined as a technical process, involving multiple impressions or imprints. An engraving is a template, a sculptural mold that functions like a photographic negative. Engraving as a medium challenges the autonomy of the pictorial image, insofar as the image acts as a temporal record of multiple impressions.[31] Although associated historically with craft rather than art, engravings challenge both the uniqueness of the plastic image and traditional notions of artistic creativity. Duchamp's pictorial series of Nude Descending a Staircase, as a multiple that undergoes extensive reproduction, illustrates the logic of engraving operative in his works. This is not to say that these works are engravings, since they are clearly paintings; rather, the conditions of production and reproduction evidenced in these series suggest conceptual processes akin to those involved in the technical reproduction of engravings.

You may ask how cartoons inform Duchamp's oeuvre? The answer by now is clear. Regarded as a form of popular art associated with the print medium, cartoons are images that are constructed like rebuses, as composites of language and image. Their humor is not just visual but intellectual. They are often visual analogues of linguistic puns. This is not to suggest, however, that Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is merely a cartoon, a rude joke at the expense of painting. Rather, Duchamp's use of the title as nominal intervention in order to restage the expectations of the spectator reframes the reception of this work as an intellectual, instead of a purely visual, experience. Consequently, despite its mechanomorphic character, Duchamp's Nude can also be seen an an "anti-machine." As Octavio Paz explains: "These apparatuses are the equivalent of the puns: the unusual ways in which they work nullify themselves as machines. Their relation to utility is the same as that of delay to movement;they are without sense and meaning. They are machines that distill criticism of themselves."[32] If the Nude is an elaborate visual and linguistic pun, where exactly is the joke? As this study has suggested, Duchamp's humor lies in redefining the visual image as a serial imprint, as a construct where appearance does not refer to an external reality but to a mode of production whose logic is reproductive. Duchamp doubly displaces painting: first, by redefining it through the logic of engraving, as a print medium, and second, by draw-

ing on the linguistic and intellectual logic of cartooning in order "to put painting once again at the service of the mind."[33] Eroticism in this context is no longer defined as a transitional movement between clothing and nudity. Instead, it becomes the rhetorical interplay between language and vision, which constructs the facticity of gender as a pun.

The Mainspring of the Future: Playing the Field

While all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.

—Marcel Duchamp

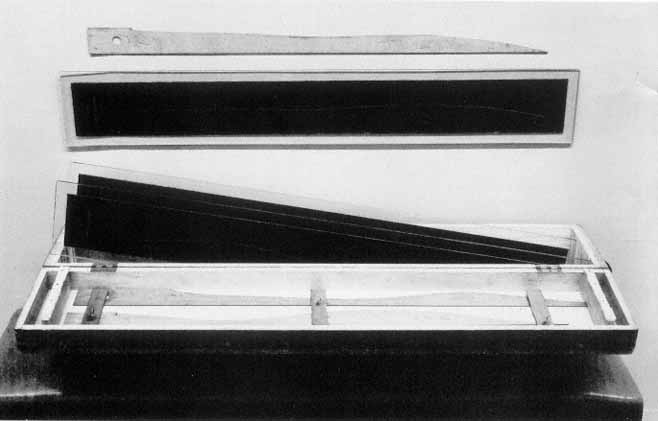

When asked by Katherine Kuh, one of his interviewers, which of his works he considers to be the most important, Marcel Duchamp replied:

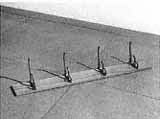

As far as date is concerned I'd say the Three Stoppages [3 stoppages étalon ] of 1913. That was really when I tapped the mainspring of my future. In itself it was not an important work of art, but for me it opened the way—the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art. I didn't realize at that time exactly what I had stumbled on. When you tap something you don't always recognize the sound. That's apt to come later. For me the Three Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.[34]

As Duchamp subsequently explains, the idea of letting a piece of thread fall on a canvas was accidental, but "from this accident came a carefully planned work."[35] What exactly did Duchamp stumble on that enabled him to escape the traditional means of expression associated with art? Was it the idea of chance, or its plastic deployment and embodiment as an event or work? Before exploring in more detail the role of Three Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages étalon; 1913–14) as a gesture that would liberate him from the past, one must first understand how this work emerges out of Duchamp's pictorial experiments, for this work decisively signifies both his break with painting and his strategic turn toward the ready-mades and The Large Glass.

Duchamp's interest in chance as a way of redefining conventional forms of artistic expression appears early on in his paintings and is tied to his interest in chess. For Duchamp, chess is not merely a pastime or an ordinary game because its intellectual character represents for him a plastic

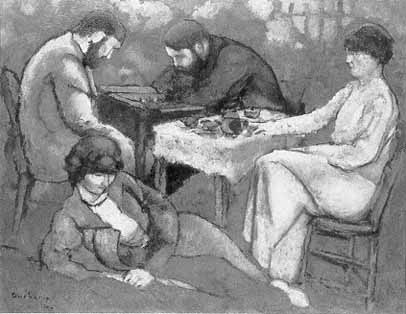

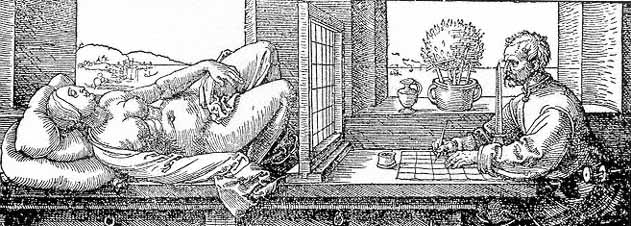

Fig. 10.

Marcel Duchamp, The Chess Game (Le Jeu D'échecs), 1910. Oil on canvas,

44 7/8 x 57 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter

Arensberg Collection.

Fig 11

Paul Cézanne, Card Players, 1892.

Courtesy of The Courtauld Institute Gallery, London.

and thus, by extension, an artistic dimension. As a strategic game that requires the interplay of two opponents, chess provides Duchamp with a new way of envisioning art in its dialogue with the tradition. The analogy of art and chess enables Duchamp to appropriate chance and redefine its plastic impact in a field of already given determinations. Starting with The Chess Game (Le jeu d' hecs; 1910) (fig. 10), and continuing through 1911, Duchamp produces a series of works dealing with chess. These include six drawings/sketches, which culminate in the painting Portrait of Chess Players (Portrait de Joueurs d'échecs; 1911).[36] These works range from a relatively conventional depiction of a chess game, to progressively more abstract renditions of the players, the board, and the chess pieces.

Duchamp's lifetime interest and preoccupation with chess is well known, but its significance and precise impact on his art is less recognized.[37] While Duchamp openly acknowledges his indebtedness of The Chess Game to Paul Cézanne's Card Players (1892) (fig. II), it is clear that he is already playing another game (DMD, 27). In The Chess Game the centrality of the table in Cézanne's Card Players is displaced on a diagonal axis along which there are two tables, one with a chessboard on it and another set in the manner of a still life.[38] Duchamp's choice to replace the card game with a chess game makes visible something that would otherwise remain invisible: the chessboard as a metaphor for the mental ground rules that define it as a game. The checkered pattern of the board, however, is also an allusion to another set of rules, those of Albertian perspective that have guided the development of painting.[39] This allusion is reinforced by the fact that the chess players are Duchamp's brothers, who are both practicing artists. If we pursue Duchamp's analogies in The Chess Game, art no less than chess emerges as a strategic, rather than purely plastic, domain. Both chess and perspective are systems whose normative standards prescribe and determine the nature of representation. What had been originally conceived as an arbitrary relation between painting and the world is now revealed to be a strategic, albeit conventional game, a chess game.

Why, you may ask, did Duchamp choose not merely to reshuffle Cézanne's cards but to play a different game altogether? The answer lies in his understanding of chess as a plastic, rather than a purely intellectual, game. As Duchamp's comments to James Johnson Sweeney indicate, playing

chess is like painting insofar as "it is like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind" (WMD, 136). This plasticity, however, is not in the realm of the visible but in the abstraction of the movement of pieces on the board. In his interview with Francis Roberts, Duchamp explains how the strategic and positional nature of chess generates plastic effects:

In my life chess and art stand at opposite poles, but do not be deceived. Chess is not merely a mechanical function. It is plastic, so to speak. Each time I make a movement of the pawns on the board, I create a new form, a new pattern, and in this way I am satisfied by the always changing contour. Not to say that there is no logic in chess. Chess forces you to be logical. The logic is there, but you just don't see it.[40]

The plasticity that Duchamp ascribes to chess is not aesthetic in the visual sense but rather intellectual. The movement of the pieces on the board creates patterns and forms whose contours are constantly shifting. This moving geometry is described by Duchamp as "a drawing" or as a "mechanical reality" (DMD, 18). As Duchamp elaborates: "In chess there are some extremely beautiful things in the domain of movement, but not in the visual domain. It's the imagining of the movement or the gesture that makes the beauty, in this case. It's completely in one's gray matter" (DMD, 18). The beauty that Duchamp appeals to is not one based on aesthetic categories, on visual appearance and artistic self-expression. Rather, the beauty in question is defined by the plasticity of the imagination, by the poetry of its ever changing contours.

The analogy of chess and art is one that is mediated by an allusion to the abstract nature of both music and poetry. As Duchamp explains:

Objectively, a game of chess looks very much like a pen-and-ink drawing, with the difference, however, that the chess player paints with black-and-white forms already prepared instead of having to invent forms as does the artist. The design thus formed on the chessboard has apparently no visual aesthetic value, and it is more like a score for music, which can be played again and again. Beauty in chess is closer to beauty in poetry; the chess pieces are the block