4—

Art and Economics: From the Urinal to the Bank

Can one make works which are not works of "art"?

—Marcel Duchamp

In assessing the significance of the ready-made, Octavio Paz underlines its challenge to traditional concepts of art and value. According to Paz, the ready-made represents a contradictory gesture, since the artist's gratuitous choice of an anonymous, mass-produced object converts it into a work of art, while destroying the notion of an art object:

The essence of the act is contradiction; it is the plastic equivalent of a pun. As the latter destroys meaning, the former destroys the notion of value. . . . The Ready-made does not postulate a new value: it is a jibe at what we call valuable. It is criticism in action: a kick at the work of art ensconced on its pedestal of adjectives.[1]

The ready-made implies an active critique of the notion of value. This critique is not dialectical: it involves neither the negation nor the affirmation of value. Rather, the ready-made is conceived as the "plastic equivalent of a pun," that is, as a mechanism staging the gratuitous conversion of an ordinary object into a work of art, while simultaneously undermining the notion of an art object through this gesture. The destruction of value, entailed by the first moment, corresponds to the annulment of meaning in the second. As "criticism in action," the ready-made radically disrupts the valuative judgment of a work as art.

As the ready-mades demonstrate, Duchamp's exploration of the concepts of art and value is not an abstract philosophical inquiry but a literal one. Instead of asking what value is, Duchamp proceeds to demonstrate its conditions and modes of operation as a social phenomenon. Not content to explore the philosophical conundrums generated by the ready-mades, he takes on the question of value on its most basic level, not merely as artistic abstraction but also as an economic phenomenon. In a series of works starting with Tzanck Check (1919), and later continuing with Cheque Bruno (Chèque Bruno; 1965) and Czech Check (1965), Duchamp proceeds to explore the relationship between art and economics, by presenting the facsimile of a check, both as monetary payment and as art. The idea of producing a work that problematizes the transactions involved in both the circulation of a work of art and of monetary currency is pursued in Wanted/$2000 Reward (1923), a parody of a police "wanted" poster. This is followed by the Monte Carlo Bond (Obligations pour la Roulette de Monte Carlo; 1924), a financial document issued by Duchamp in order to raise funds to test his formula for a betting system at the roulette wheel. In these works the autonomy of the artistic and economic domains is challenged by a speculative interpretation of value that uncovers their shared social and symbolic concerns.[2]

This inquiry into value as a function of art and economics culminates in Duchamp's return at the end of his oeuvre to a ready-made that is both an artistic and economic artifact. First issued under the title Drain Stopper (Bouche-Evier; 1964), this work is reissued subsequently as a set of numismatic coins, and retitled Marcel Duchamp Art Medal (1967). These works return to Duchamp's Fountain (fig. 48, p. 125) by commemorating the urinal that literally flushed the notion of artistic value down the drain. The reproduction of Drain Stopper as Marcel Duchamp Art Medal transforms the work of "art" into a limited edition of numismatic coins, that is, works embodying both artistic and economic notions of value. Duchamp's deliberate conflation of artistic and economic categories, however, produces a paradoxical effect: that of undermining both art and economics. By challenging the concept of inherent value through reproduction, the notion of the artistic value will emerge as a speculative correlative of economic value. Hence the questions that this study will address are: 1) what is the relation of artistic and commercial activity,

2) can money or the record of a monetary transaction become a work of art, 3) is art a gamble or a speculative transaction, and 4) are numismatic coins economic and/or artistic artifacts? Duchamp's works stage, in dramatic terms, a transformation in the concept of value for modernity, since a debate about artistic value becomes the ground for a revaluation of the concept of value itself.

Is it Business or Is it Art?

Money was always over my head.

—Marcel Duchamp

There is one detail in Marcel Duchamp's lengthy artistic career that troubles both his sympathizers and critics alike: the fact that he bought and sold paintings, those of others, as well as his own. Pierre Cabanne questions Duchamp's forays into commercial activity, since they blatantly contradict his own expectations of Duchamp's artistic attitude and supposed "detachment" from material concerns.[3] Cabanne is not alone in asking these questions. When asked about why Duchamp allowed an expensive edition of ready-mades to be done by Arturo Schwarz, John Cage echoes Cabanne's sense of contradiction:

"Why did you permit that, because it looks like business rather than art" and so forth. Marcel admitted that it could be so interpreted, but it did not disturb him. He was extremely interested in money. At the same time, he never really used his art to make money. And yet he lived in a period when artists were making enormous amounts of money. He couldn't understand how they did it. I think he thought of himself as a poor businessman. These late activities were like business.[4]

Cage's comments demonstrate the difficulty of sorting out, or rather, understanding how art and commerce come together in Duchamp's works. Insisting that Duchamp was not "using" his art to make money, Cage underlines both Duchamp's interest in money and his attempt to disengage his art from monetary concerns.

Still, Cage has problems with the late editions of the ready-mades, which, unlike the "original" editions, he now considers to be like "business." While Cage recognizes Duchamp's caution and discipline in not

"extending the notion of the Ready-mades to everything," as well as his original difficulty of coming to the decision to make them, he also feels that later in life, Duchamp abandons this caution and "would sign anything that anyone asked him to."[5] Thus, while Cage is able to recognize the limited edition aspect of the ready-mades, he is unable to deal with Schwarz's reissuing them as a "second edition." Whereas Cage is willing to assume Duchamp's initial signature as the signature of the artist, he is uncertain whether the second signature is not merely that of the businessman.[6] The effort to extricate art from economics proves to be extremely difficult, since Duchamp's oeuvre stages significant questions regarding the effects that the ready-mades, as reproducible objects, will have on the relation between art and economics, as well as the definition of the artist as author and guarantor of artifacts.

Cage's and Cabanne's difficulty in reconciling art and business reflects a fundamental prejudice in the Western conception of the artist, which supposes art to be entirely removed from the economic sphere. There is, however, something fundamental shared by art and economics: the notion of value. It can be argued that value in art is an abstraction, since masterpieces are so valuable that they are often priceless. Yet the same is true of the value generated by commercial transactions, insofar as worth is relative to the system of exchange that generates it. What fascinates Duchamp is the process by which a work acquires artistic and commercial value. The production of value entails, for him, a social and speculative dimension. In his interview with Cabanne, Duchamp describes his earliest venture into commercial activity "sometime before" 1934:

That was with Picabia. We agreed that I would help him with his auction at the Hotel Drouot. A fictitious auction, however, since the proceeds were for him. But obviously he didn't want to be mixed up in it, because he couldn't sell his paintings at the Salle Drouot under the title "Sale of Picabias by Picabia!" It was simply to avoid the bad effect that would have had. It was an amusing experience. It was all very important for him, because, until then, no one had had the idea of showing Picabias to the public, let alone selling them, giving them a commercial value. . . . I bought a few little things then. I don't remember what, anymore. (DMD , 73)

Duchamp's account of his first business venture sounds more like a performance art piece than a genuine commercial endeavor. By staging a fictitious auction of Picabia's works in order to recover the proceeds for Picabia, Duchamp uncovers the relationship of artistic and commercial value in the intervals between the signature, the work, and its circulation. As he points out, it would have been absurd to have a "Sale of Picabias by Picabia," since there would be no buyers. The artist's signature authorizes the work, but cannot confer value on it, since value is not inherent to the object but defined through social exchange. The price of a work in an auction is determined by the prospective buyers bidding against each other. Thus, value is created through exchange, through the display, circulation, and consumption of the work, in a game where worth has no meaning in and of itself.

Duchamp mentions other instances of participating in art deals, such as his efforts to buy back his own works for his patron Walter Arensberg, and later, helping Arensberg to "round them up" for the Philadelphia Museum.[7] Preceding his efforts to help Arensberg there is also Duchamp's initiative to organize an exhibition featuring the works of Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957), after he purchased some of the artist's works at the Quinn auction. Constantin Brancusi asked Duchamp and Jean-Pierre Roché (1879–1959) to buy back his works, since he wanted to avoid a public sale, afraid that it would bring in lower prices than previous sales of individual works. Duchamp asked Mrs. Rumsey to buy back the twenty-two Brancusis, which were split up among three partners, and helped Duchamp make his living.[8] Moreover, there was Duchamp's curious idea, the amusing project of selling for $1.00 insignias bearing the letters DADA "cast separately in metal and then strung on a small chain."[9] Outlined in his letter to Tristan Tzara (New York, 1921), Duchamp proceeds to explore the implications of his project by considering its potential effects:

The act of buying this insignia would consecrate the buyer as Dada . . . the insignia would protect against certain diseases, against the numerous annoyances of life, something like those Little Pink Pills which cure everything. . . . Nothing "literary" or "artistic," just straight medicine, a universal panacea, a fetish in this sense: if you have a toothache, go to your dentist and ask him if he is a Dada.[10]

Duchamp's parody of Tzara's "everything is Dada," becomes a parable of commercial consumption, insofar as the possession of the Dada insignia consecrates the buyer as Dada. The equation between acts of consumption and consecration reveals the magical and curative dimensions of commercial activity. The act of possessing this insignia or fetish endows the bearer with a special aura—in this case an artistic one, that of Dada. As Duchamp explains to Cabanne, this idea was in the same spirit as André Breton's idea of opening up a Surrealist office to give people advice (DMD , 74). Duchamp's commercial ventures thus emerge as mechanisms that reveal the shared social and ideological subtext of both commercial and artistic exchange.

If Duchamp's commercial ventures invariably involve an artistic context, his artistic ventures, in turn, involve an unexpected legal and economic dimension. In a newspaper account about Fountain in the Boston Evening Transcript (25 April 1917), the public is provided with the "official record of the episode of its removal":

Richard Mutt threatens to sue the directors because they removed the bathroom fixture, mounted on a pedestal, which he submitted as a "work of art." Some of the directors wanted it to remain, in view of the society's ruling of "no jury" to decide the merits of the 2,500 paintings and sculptures submitted. Other directors maintained that it was indecent at a meeting and the majority voted it down. As a result of this, Marcel Duchamp retired from the board. Mr. Mutt now wants more than his dues. He wants damages.[11]

The threat of a lawsuit becomes an in-joke, once we recognize Mr. Mutt as Duchamp's artistic alter ego. This incident summarizes the performative dimension of Fountain, the fact that the failure to exhibit the work becomes a "work" of sorts in its own right. Thus, a debate regarding value may generate value in turn (in the form of either interest, damages, or both). Given that the motto of the American Society of Independent Artists is "No jury, no prizes," Mr. Mutt's (alias Duchamp's) suit, not for dues but for damages, translates the artistic debate about Fountain into legal and economic terms.[12] In a letter to his sister Suzanne (11 April 1917), Duchamp claims that a female friend submitted the urinal under a

male pseudonym. After announcing his resignation from the association, Duchamp concludes: "it will be a bit of gossip of some value in New York" (emphasis added).[13] Rather than clarifying his own status as author of Fountain, Duchamp persists in mystifying his own participation. This act of mystification, through the introduction of both a male and a female alias, highlights the fact that this debate about artistic value might refer less to the object than to its authorial and social context. Duchamp's comment about the "value" of his own resignation underlines the strategic role of Fountain in generating value from a debate about value. Thus, as suggested earlier, the value of the urinal is determined not by its "objective" character but instead by the exchanges it generates.[14] The value of this object is strategic: it is a mechanism that triggers critical debate, by staging the interplay of structures of authority, legitimization, and authorship in the constitution of artistic value.

Rather than being reassured by Duchamp's answers, however, his interviewer Cabanne persists in challenging his involvement in commercial activity. In response to Cabanne's question regarding whether commercial activity may contradict his artistic position, Duchamp elaborates:

No. One must live. It was simply because I didn't have enough money. One must do something to eat. Eating always eating, and painting for the sake of painting are two different things. Both can certainly be done simultaneously, without one destroying the other. And then, I didn't attach much importance to selling them. I bought back one of my paintings, which was also in the Quinn sale, directly from Brummer. Then I sold it, a year or two later, to a fellow from Canada. This was amusing. It did not require much work from me. (DMD , 74; emphasis added)

Duchamp's comment is revealing to the extent that it resituates the question of economic activity alongside, and not in contradiction with, artistic activity. Duchamp's bemused interest in commercial activity reflects his artistic bias, since value is generated independently from the conditions of the actual "making" or production of an object. Value is generated transitively through exchange, not requiring "work" in the ordinary sense but requiring another kind of labor of an intellectual, speculative order.

Now we can begin to understand Duchamp's interest in economics, since the question of value in the economic domain presents problems that are analogous to those Duchamp explores in the artistic domain—most particularly, his rejection of the artisanal production of objects (the cult of the "hand"), such as we see embodied in the ready-mades. It is this intellectual dimension of ready-mades that is regarded with some suspicion by artists, such as Robert Smithson, who claims that in the case of the ready-mades, Duchamp is trying to "transcend production itself" and that "He has a certain contempt for the work process and here. . . he is sort of playing the aristocrat."[15] Smithson's comment highlights the contradictions that the ready-made poses as a work of art, insofar as its "value" cannot be linked to a manual system of production, since it is mass-produced. Rather, the "value" of the ready-made is determined in relation to the artistic norms that it defies and reduces to meaninglessness. Based on the discussion in chapter 2, it seems that while the ready-made is not the result of artisanal production but rather of mass reproduction, this aspect forcefully engages the spectator in another kind of "work" of an intellectual order. The ready-made is not an object in the ordinary

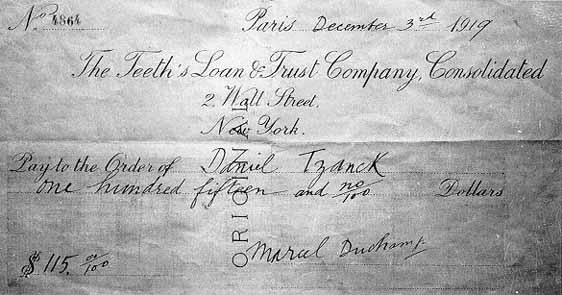

Fig. 59.

Marcel Duchamp, Tzanck Check, 1919. Imitated rectified readymade: enlarged manuscript version of a

check, 8 1/4 x 15 1/8 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

sense, since it is the "plastic equivalent of a pun," that is, a visual and linguistic machine. This mechanism "works" by translating a set of abstract concerns, about the effects of mechanical reproduction on the work of art, into their plastic equivalents.

Consequently, given Duchamp's interest in how an art object accrues both artistic and financial value, his own involvement in the sale and acquisition of art should come as no surprise. Rather than viewing Duchamp's commercial activity as a betrayal of both his artistic detachment and putative disinterest in financial value, his fascination for the speculative value of art can be better understood in intellectual terms. It is a fascination with how artistic and monetary value is generated arbitrarily through social exchange. Duchamp's interest in the speculative character of money does not translate itself into the subservience of his own artistic work to monetary considerations. Instead, it expresses the recognition that value, be it artistic or financial, is embedded in a circuit of symbolic exchange.

Reproduction as Crime: Money as Art

And above all, I wanted as much as possible not to make money

—Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp's explicit interest and involvement in commercial and artistic transactions becomes the very subject of a series of works, starting in 1919. These works include several types of facsimile checks, Tzanck Check, Cheque Bruno, and Czech Check, which were issued over a period of forty years. In these works the question of value is no longer implied as an abstract reflection, hence the discrimination between what may or may not be art. Rather, Duchamp chooses to address the question of value literally, not as abstract worth but as concrete currency. Just as Duchamp problematized the distinction between art and nonart, so he now proceeds to examine the distinction between art and economics as a function of the social and institutional exchanges they imply.

Although contemporary to Duchamp's reproduction of the Mona Lisa in L.H.O.O.Q. (fig. 53, p. 140), the Tzanck Check (fig. 59) is a reproduction of money, rather than a work of art. In this particular case money, as a means toward the acquisition of art, becomes the end, since its reproduction through a check transforms it into a work of art. It is important to note, however, that Duchamp chooses to reproduce a check rather than

currency.[16] A check is merely an order for the payment of money on demand. It is another kind of legal tender, which is more specific than money, since it involves a blank (the addressee), a bank (institutional endorsement), a date, and a signature (individual endorsement). These institutional markers that define the legal identity of a check also define the institutional parameters of a work of art. The anonymous spectator of the work of art occupies the blank space of the addressee, while dates are essential to both art and business. The author's signature, however, acts as the guarantor of the authenticity of the work, as well as the general guarantor, the "bank" (the artist's reputation that backs this particular issue of the work). But the work of art has a title, descriptive or poetic, although it is unclear whether this type of designation is specific or generic. It is this entrance into nomination that distinguishes art from checking, to the extent that the name confers identity by individualizing the object. This "entitlement" of art is relatively recent, however, and reflects a shift in our definition of the authority of the artist and the status of an artwork.[17]

Like Duchamp's ready-made Fountain, which embodies his "dry" interpretation of art, these checks become the basis for exploring the conceptual interval between art and economics. This process literally involves "checking," that is, verifying by comparison how value is posited and expended in these otherwise autonomous domains. The Tzanck Check documents a transaction between Duchamp and his dentist Daniel Tzanck, which Duchamp summarizes as follows:

I asked him how much I owed, and then did the check entirely by hand. I took a long time doing the little letters, to do something which would look printed—it wasn't a small check. And I bought it back twenty years later, for a lot more than it says it's worth! Afterward I gave it to Matta, unless I sold it to him. (DMD , 63)

As Duchamp explains, this check is a payment in "art" for medical services rendered. In return for what he owes Duchamp gives his dentist a work of art, whose value, however, unlike money, continues to accrue interest. In settling what appears to be an ordinary debt Duchamp's payment in "art" exceeds the terms of the original obligation. It is important to recall, however, that in addition to being a dentist, Tzanck was an avid

art lover and the founder of a society of art collectors dedicated to the appreciation of modern art, who proposed the creation of a museum of modern art in Paris.[18] Given Tzanck's involvement with modern art, one must wonder whether the Tzanck Check is more than an ordinary payment. By recording their anecdotal transaction through a check that is also a work of art, Duchamp translates his obligation from financial into symbolic terms. Within this system of symbolic exchange, reciprocity replaces debt, insofar as Duchamp's gesture leads to Tzanck's indebtedness for having "slipped into the history of art."[19]

A closer examination of the Tzanck Check, created in December 1919, reveals how these apparent contradictions are explicitly staged by this work. Given the fact that this work immediately follows the notorious L.H.O.O.Q., which dates to October 1919, the question of the shared concerns of these two works imposes itself. Notably, both are reproductions, albeit in different ways. Whereas L.H.O.O.Q. is a commercial reproduction of a masterpiece, a ready-made, the Tzanck Check is a hand-drawn, larger-than-life facsimile, which looks as if it were printed. The difference is that the "artist has painstakingly applied his skill to the manual imitation of an item which modern techniques of mass production would normally print out in an instant."[20] This work is an "Imitated Rectified Ready-made," that is to say, a work that reproduces mechanical mass production, like a mechanical drawing that, according to Duchamp, "upholds no taste, since it is outside all pictorial conventions" (DMD, 48). Although we are dealing with two different types of reproduction, commercial and manual (based on commercial), the effects of these two gestures are very different. In the first instance, the act of commercial reproduction challenges the uniqueness of the masterpiece, insofar as mechanical production displaces pictorial and artisanal techniques. In the second instance, the deployment of manual dexterity is merely an imitation of commercial reproduction and hence, no more original than an industrial drawing or prototype for a machine.

Duchamp provides clues to how the Tzanck Check should be interpreted by comparing it to the phonetic puns of L.H.O.O.Q ., where in his words "reading the letters is very amusing" (DMD , 63). If L.H.O.O.Q. is a very elaborate linguistic and visual game, what are the puns staged by the Tzank Check? In addition to the alliterative sound of the title, this work,

also published under the title of Dada Drawing (Dessin Dada) in Francis Picabia's journal Cannibale (25 April 1910), presents a network of puns combining artistic allusion with monetary analogy. The name of the bank, designated on the check as "The Teeth's Loan & Trust Company," seems initially a gratuitous inversion of the guarantor (the Bank) and its client (the dentist), since in this case the check appears to be backed by a loan and trust (not exactly a savings) bank called "Teeth." The insistence of the phrase "the teeth'sloanandtrustcompanyconsolidated," which is repeatedly stamped on the lower half (with a rubber stamp of the phrase made especially to be used on this one occasion) along with the word "ORIGINAL" printed across in red, can be interpreted at face value as attempts against forgery and guarantees of the "originality" of this fake check.[21] But the face value of this check is only backed by a "rubber stamp," whose limited use by no means clarifies the nature of such fictitious backing. What then is the fiction that underlies the history of this check?

Duchamp's references to "teeth" in his Notes invariably involve combs: "Classify combs by the number of their teeth" (WMD, 71).[22] Thus the "teeth" in the title of the Tzanck Check 's bank, "The Teeth's Loan & Trust Company," is a reference to one of Duchamp's earlier ready-mades, entitled Comb (Peigne, a pun on painting, in French). This allusion to painting in Tzanck Check, scripted in the guise of the bank (as the check's backer or guarantor), is not altogether surprising given the affinities of this work with L.H.O.O.Q. As respective reproductions of money and art, these works reflect the problem of assigning, defining, and preserving a classical notion of value in the modern context. The emergence of mechanical forms of production redefines economic and artistic modes of production, as modes of reproduction. As a reproduction of money, which also makes claims to be art, the Tzanck Check alludes both to the loss of painting's bite, engineered by industrialization, and also to its potential to prevail by "hanging on by its teeth." Thierry de Duve summarizes the paradoxical relation of the Comb to the history of painting:

The work refers to painting as it is both impossible and possible, i. e., on the one hand, felt and judged as doomed by industrialization and therefore having to be actively destroyed or abandoned, and on the other, retaining a potential that lies precisely in its abandon-

ment, understood as the postponement of any pictorial "happening" and therefore of painting's final demise.[23]

But in order to hang on, painting can no longer be defined by the hand, but by the head. The Tzanck Check embodies Duchamp's efforts to save painting by redefining it as an intellectual, rather than a manual endeavor. Instead of putting painting simply "out to dry," or out of business, Duchamp merely "hangs up his hat" (similar to the English expression to take possession of a new home, especially by marrying a daughter of the house). In other words, Duchamp redefines painting in terms of the conceptual possibilities generated by the postponement of its pictorial conventions. While escaping pictorial conventions, this hand-drawn work still "draws" on the history of painting, since the word "to draw" (tirer, in French) refers equally to drawing a portrait or a check. The Tzanck Check continues to draw (understood also as an inspiration and as a prize) speculatively on painting, thereby announcing its demise while postponing its conceptual potential or interest. Given that Duchamp describes the language of his father's (a notary) legal papers as "killingly funny" (DMD, 103), we wonder whether the Tzanck Check does not represent his own "drawing up" of a document/work whose intent is to legitimize his particular interpretation of art: one where the will and testament of art is defined by its symbolic expenditure.

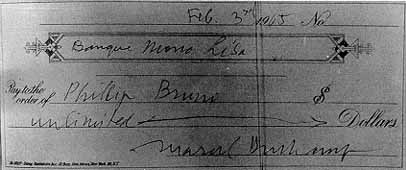

In 1965 Duchamp produced another facsimile of a check, a signed, blank check made payable to "Philip Bruno" (fig. 60) for an unlimited amount drawn on the "Banque Mona Lisa."[24] By declaring "Banque

Fig. 60.

Marcel Duchamp, Cheque Bruno (Chèque Bruno), 1965. Collection of Mr.

and Mrs. Phillip A. Bruno. Photograph courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

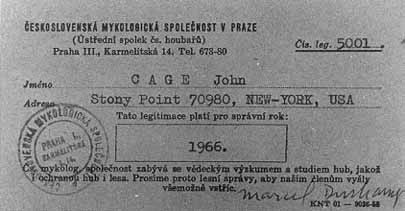

Fig. 61.

Marcel Duchamp, Czech Check, version of 1966. Collection of Mr. and

Mrs. Harris K. Weston. Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Mona Lisa" as the guarantor of this "carte blanche" check, Duchamp further clarifies the inscription of painting as the equivalent of monetary currency in his works; by designating "Mona Lisa" explicitly as a bank, Duchamp invites the spectator to consider how value is generated, as well as how Duchamp will "spend it" by drawing checks on it.[25] The value of the Mona Lisa as a "priceless work of art" presents a paradox: it is a work that is so valuable artistically that it is of immeasurable financial worth. As a "masterpiece," this work's artistic and economic value invokes a concept of value in excess of all values. Yet Leonardo's Mona Lisa is not a pictorial equivalent of gold or metric standard.[26] Rather, its artistic value is arbitrarily backed by a speculative market, whose authority relies on the manipulation of both academic and financial credit and currency. Given the authority of the Mona Lisa, Duchamp proceeds to issue "checks" on this masterpiece, backed by its artistic and financial authority. L.H.O.O.Q. may be the first of these checks, since like money it is a unique print insofar as it is signed and issued as a numbered edition. Although L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved appears to restitute the Mona Lisa to her former "carte-blanche" appearance (minus the mustache and goatee), it does not succeed in completely restoring her original value. This "devaluation" of the Mona Lisa is a minute, almost imperceptible event, obeying the logic of the "infrathin." Duchamp defines the "infrathin" as an infinitesimal difference generated by repetition: "All 'identicals' as/ identical as they may be, (and/ the more identical they are)/ move toward this/ infra

thin separative/ difference" (Notes, 35). Associating the logic of reproduction with the "infrathin," Duchamp accounts for the production of differences through repetition.

By "spending" the Mona Lisa, that is, by putting into circulation signed prints or by drawing on her indirectly as a "bank," Duchamp sets into motion an alternate interpretation of value based on notions of expenditure. Value, be it artistic or monetary, is generated through exchange; it is neither essential to nor coextensive of actual objects. Duchamp's works break down the notion of an artistic standard through speculation. His reproductions abolish the notion of artistic production through expenditure, that is, through a gesture that mimics economy only to abolish the concept of abstract worth. While celebrating exchange through speculation, these economic/artistic works annul the traditional norms and institutional standards that define value in a classical sense. These works rectify the tradition within which the Mona Lisa is perceived as a masterpiece; they emerge as artifacts, whose value depends not on an original but instead on the playful subversion of the notion of artistic creativity.

These multiples inscribe within the original a concept of seriality that redefines it as a limited edition. The Tzanck Check and the Cheque Bruno are originals whose value derives from their reproducibility: they are, by definition, limited editions. As financial documents, their value is transactional. It resides not in their artistic content but in the displacement of value into the overlap of monetary and artistic categories. The ostensible financial referent of these checks involves payments and banks that reveal the fictitious character of commercial transactions. The fact of "drawing" on these fictitious categories means inscribing into the act of commercial exchange a speculative dimension that amounts to a new way of thinking about art.

Not content to challenge the categories of the check and the bank as guarantors of a financial transaction, Duchamp proceeds to challenge the notion of signature. After all, both the originality of artworks and the viability of monetary currency is guaranteed through signature. Along with the Cheque Bruno (1965), Duchamp produced another work entitled the Czech Check (fig. 61), consisting of Duchamp's own signature added to John Cage's membership card in a Czech mycological society. Cage describes Duchamp's gesture as follows:

I had become a member of the Czechoslovakian Mushroom Society, and when I received my membership card—there were various signatures—I thought what a pleasure it would be to have Marcel's signature too. And so I gave it to him; and he signed it immediately and very beautifully. By beautifully, I mean in an interesting place. It looked as though he was one of the Czechs, (emphasis added)[27]

What is unusual about the Czech Check is the fact that it is not a check, in the ordinary sense of the word. This is Cage's membership card, which Duchamp signs as if he were one of the founding Czechs of the association, that is, as a board member acting as a symbolic guarantor for the institution. Rather than designating Duchamp the individual, his signature on the membership card impersonates someone else's symbolic authority and Czech nationality. Why, then, is this work called the Czech Check, or rather, how does a membership card become a check? By signing his name along with the Czechs, as a sign of his endorsement of the association, Duchamp "endorses" the rights of the rank and file members to "draw" on the authority of the association. Becoming a member thus implies using this endorsement as if one were writing a check. Following the playful logic of this gesture literally, becoming "Czech" means that one can write checks. By staging the conditions of authority that define membership, Duchamp identifies the transactional context that subtends both the membership card and commercial exchange.

The story, however, does not end here. As Cage explains, he was able to sell his membership card signed by Duchamp for $500 in order to raise money for the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. Regretting the loss of his card, Cage was delighted when he received in the mail, the very same day it was sold, the next year's membership card. Having pointed out this coincidence to Duchamp, he replied: "There's no problem; I'll sign it too."[28] Cage tells this anecdote as a way of documenting a change in Duchamp's attitude—the fact that later in life, Duchamp would sign anything.[29] Duchamp's willingness to sign Cage's second membership card, and thus to reproduce his own signature, raises the specter of the artist trivializing the work through its repetition. How, then, are we to understand Duchamp's gesture? Duchamp's decision to sign the second membership card is as deliberate as the first. The fact that the first card is

"sold" underlines its affinity with a check, hence its title the Czech Check. Retrospectively, however, it appears that the value of this card is not determined by the authority of the Czechoslovakian Mushroom Society but rather by Duchamp's signature. It is his abstract "value" as an artist that backs his signature, thereby acting as an endorsement that can be translated into precise financial terms. If a masterpiece such as the Mona Lisa can become a "bank," why can't Duchamp become a "bank," as well? If Duchamp is in fact posing questions regarding the authority vested in the artist, signing the second card is simply the equivalent of issuing another check on the same bank. But in doing so has he become a counterfeiter of himself?

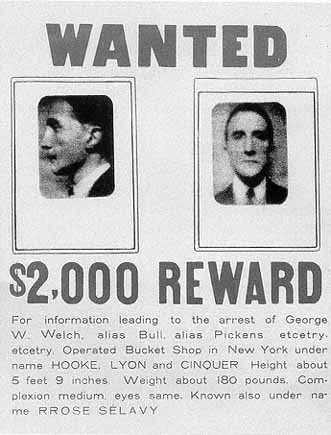

Wanted/$2000 Reward (fig. 62) is a joke "Wanted" poster for "George W. Welch, alias Bull, alias Pickens, etcetry," which has been altered by adding two mug shots (photographs, one profile and one full face) of Duchamp, and the name Rrose Sélavy, on the bottom, which was substituted for the previous name by a printer. The only extant version of this item is a color reproduction in The Box in a Valise. This work presents a new interpretation of the artist as a wanted criminal for operating a bucket shop. A bucket shop is an office for gambling, as in stocks or grain, by going through the form of buying and selling with no actual purchases or sales. In other words, the criminal in question is guilty of gambling and of going through the motions of commercial transactions, without actually engaging in them. The crime involves speculation without the actual trade of the goods themselves.

This bucket shop is operated by an individual under the alias "HOOKE, LYON and CINQUER," a name that is a joke both on a corporation and a common expression signifying that by fair or foul means, any individual may be ensnared lock, stock, and barrel, that is, taken for a ride or deceived. The other aliases of this con man include the name "Bull," which in commercial terminology refers to a dealer in stocks who endeavors to raise the price of stock in order that he may sell at a higher price. Even the original name on the poster, "George W. Welch," is deceptive, insofar as "Welch" is the colloquial expression for cheating, defaulting, or evading an obligation—usually the payment of a gambling debt—thereby inscribing within the proper name the insignia of a con job.[30] This extensive proliferation of aliases on the poster suggests a crime whose nature

Fig. 62.

Marcel Duchamp, Wanted/$2,000 Reward, replica of original

version of 1923 (lost) from Box in a Valise (Boîte En Vailse),

1941—42. Rectified ready-made: photographs on paper.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and

Walter Arensberg Collection.

involves deception through speculation, that is, generating value gratuitously, from fake transactions. The nature of the gamble in question does not involve actual sums but rather expectations. As the alias "Pickens" punningly implies, this elaborate scam may involve only small pickings, that is, small, cautious bets placed by someone who knows how to choose or select the best ones.

Still unanswered is the question of what kind of "Wanted" poster this is. Who exactly is wanted, and for what kind of crime? Is Duchamp a counterfeiter of money, art, or both? The last alias on the poster, "RROSE SÉLAVY," provides a clue, since this alias is the name of Duchamp's female artistic alter ego, a name with which he sometimes signed his works. The adoption of a female alias, after a lengthy list of aliases associated with

different types of con men and con jobs, inscribes a new kind of gamble into this relay of identities. This gamble involves his artistic project, his self-identification with his female artistic alter ego Rrose Sélavy, as well as the eroticism implied in artistic activity understood in the mode of reproduction. The eruption of female identity in the midst of this litany of male names inscribes the trace of difference into the apparently sterile reproduction of sameness. This self-multiplication of the authorial persona into a relay of identities "eroticizes" the authorial function as a process of engenderment.[31] It redefines the author as the site of reproduction, so that self-representation corresponds to the self-portrait of the artist as another, or as multiple others. This delirium of personas that Wanted actively stages embodies the dilemma of the artist as a necessary con man or woman, since making art ultimately implies becoming subject to someone else's expectations.

This nonidentity of the artist and the work, as well as the artist him/ herself, is explicitly staged in Wanted, insofar as the efforts to designate the artist through the work, or as the work, are doomed to failure. In forging his own identity as an artist by affiliating it with a criminal gesture Duchamp declares himself to be "Wanted," that is, worthy of identification and arrest. The price of the reward—$2,000 (a sizable sum in 1923)—is a measure of the urgency of the public's desire to capture him. Given the fact that Duchamp himself issues this "Wanted" poster, this public announcement corresponds to an act of self-denunciation. This situation takes on absurd dimensions, since the authorities, the informer, and the criminal are one and the same person, the artist. Duchamp thus uses his artwork to denounce art itself as a gamble with criminal implications. Using art to denounce himself as an artist, Duchamp perpetrates the unusual gamble of assigning value to himself, there by conflating his desire with that of the spectator. If art is a blind gamble, being an artist means gambling one's own identity in order to generate a reward (interest) that only the spectator can collect. Wanted thus stages the problematic status of the artist as a conflation, or even as a corporation, of artistic personae, and that of art as a gamble, whose speculative character resembles financial transactions, like interest bearing certificates. If art is a scam, its "criminal" nature is but the reflection of the fundamental impossibility both of identifying the artist as anything other than a set of appearances

and of isolating artistic activity from the circuit of symbolic exchange, that is, from all other forms of social consumption and expenditure. This is why art is conceived by Duchamp as a gamble whose outcome is uncertain, since the wager in question relies on the contingent interest and speculative investment of the spectator.

Reproduction as Speculation: Drawing on Chance

No stars? chance annulled?

—Stéphane Mallarmé, Igitur

You see I haven't quit being a painter, now I'am drawing on chance.

—Marcel Duchamp

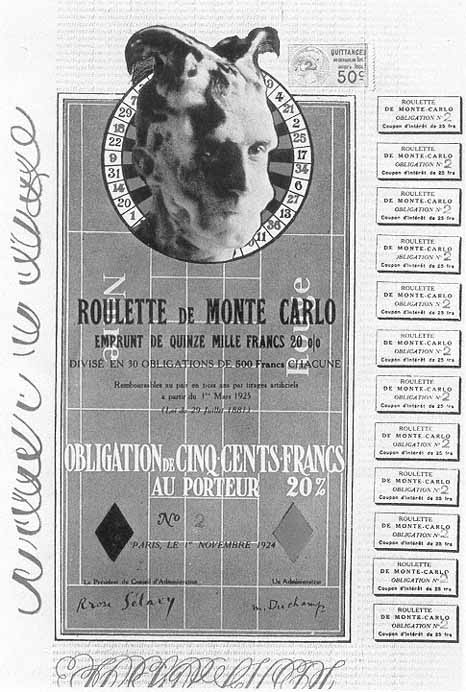

In the Monte Carlo Bond (fig. 63), a work immediately following Wanted/$2000 Reward, Duchamp explicitly pursues the analogy between art and gambling. In addition to the financial implications of this work, the Monte Carlo Bond may be considered an effort on Duchamp's part to put up a bond for himself, as security for another, in order to bail himself out of jail. Presumably, this is a response to his self-identification as an artist/gambler and his identification of art as a scam in Wanted/$2000 Reward. The problem, however, is that Duchamp appears to be issuing a bond on his own authority, responding to the initial scam staged by Wanted, through the introduction of an even more elaborate scam. A bond is an interest-bearing certificate issued by a government or a corporation to pay a principal sum on a certain date, with interest. The Monte Carlo Bond (issued as a limited edition of thirty copies) was to be sold at Fr 500 with a guarantee of 20 percent interest redeemable in three years by "artificial drawing of lots" (Remboursable au pair en trois ans par tirages artificiels), starting 1 March 1925. The appearance of this fictitious bond immediately undermines the authority of the financial transaction it is intended to secure. The Monte Carlo Bond is a collage (an "Imitated Rectified Ready-made") of a color lithograph of a roulette table with Man Ray's photo of Duchamp's soap-covered face and head, glued to a roulette wheel. Parodying an official financial document, this bond bears all the marks of "authenticity" associated with this type of transaction. It is an individually numbered bond, signed twice by Duchamp, on the right as Rrose Sélavy (president of the company), a "name by which Marcel is as well-known as his regular name" (WMD, 185), and on the left as Marcel Duchamp (an administrator). As Amelia Jones observes, Duchamp's double signature as himself and as Rrose Sélavy, suggests that

Fig. 63.

Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond (Obligations Pour La Roulette De Monte Carlo),

1924. Imitated rectified ready-made: collage of color lithograph with photograph by Man

Ray of Marcel Duchamp's soap-covered head.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Rrose is an independent partner, one who, as president, presumably has authority over Duchamp, who is a mere administrator: "Rrose becomes an author through signing and yet she herself has been 'authored'."[32] Duchamp's game with his own authorial persona, Rrose Sélavy, legitimizes the bond through the production of a corporate entity whose composite identity is generated by the fiction of his alias, of himself as an other. The collective signatures designating the corporate identity embodied in the bond, which both authenticate and authorize it, here emerge as the punning mirrors of Duchamp's literal embodiment as a corporation. By problematizing his own authority as an artist, through the fictional inscription of an other (be it Rrose, his female counterpart, or the spectator who "makes the picture"), Duchamp reveals the tenuous bond between the author and the work, especially when the work functions as a putative embodiment of the artist.

Duchamp's photograph on the Monte Carlo Bond, a self-portrait of his head covered with shaving foam and his hair pulled up into horns, further destabilizes the authority of this financial document. The fact that this bond is framed by the uninterrupted phrase "Moustiquesdomestiquesdemistock" (domestic mosquitos half-stock), only adds evidence that the visual appearance of this work might be as unreliable as the signatures backing it up. While Duchamp's appearance, his readiness for a "shave," might be interpreted psychoanalytically as a sign of decapitation or castration, such a premise fails to take into account the fact that the context of this bond involves gambling.[33]

Could Duchamp's ready-to-be-shaved head be the Joker, that extra card used in certain card games as the highest trump, or in another context the nullifying clause of a legislative measure? What kind of concealed obstruction or difficulty does this image represent, and is the threat of this close shave the sign of a narrow escape? The clue to this image, as in most of Duchamp's works, lies not merely in its visual referent, but in its discursive one as well. To shave means to fleece or cheat, to drive a hard bargain, and in commercial slang it means to buy notes or securities at a discount greater than the legal rate. Is Duchamp's impending "shave" intended to take a barb at the spectator—a pointed joke on himself and others? Having "shaved" the Mona Lisa by taking a reproduction that has not been altered by his graffiti mustache and goatee, Duchamp

"spends" this image by putting it into circulation under his own signature. By reinvesting this reproduction with a new kind of "interest," in effect, he "banks" on it, thereby reducing it to a financial issue, a "bond" of sorts. Duchamp and Leonardo become the corporate backers of this reproduction, which now attains an "original" status.

Likewise, in the case of the Monte Carlo Bond, Duchamp's hint at "shaving" himself suggests a clue as to how he might be "shaving" (cheating or fleecing) the spectator. The threat of his impending "shave" implies restoring his own image to its female counterpart, Rrose Sélavy. This act of restoration, however, does not lead to the uncovering of an original but that of an alias (a reproduction), whose financial authority is backed by the fictitious corporate identity of Duchamp/Rrose Sélavy. Duchamp's calling card (and perhaps his business card, as well) introduces him as "PRECISION OCULISM/ RROSE SÉLAVY/ New York-Paris/ COMPLETE LINE OF WHISKWERS AND KICKS" (Oculisme de Précision/ Poils et Coups de Pieds en Tous Genres ). This dual specialty in precision oculism and whiskers and kicks further emphasizes Duchamp's particular expertise as an artist whose business is visual and linguistic puns. Oculiste sounds like (au culiste, meaning "in the ass" in French), yet another allusion to Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q., thereby attesting to Rrose's specialization in precision ass and glass work. Whiskers and kicks refer to Duchamp's pointed barbs at tradition, his travesties of the Mona Lisa "shaved" and "unshaved." As Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson point out, "Duchamp hardly ever misses a chance to boot us in the rear when we are reverently bent over examining and explicating his work" (DMD , 105).

Rather than identifying its carrier, this calling card thus establishes Duchamp's particular intervention as an artist of multiple embodiments: his interrogation of the visual (ocular) invariably sets the spectator into motion by forcing him/her to stumble through puns. Robert Lebel points out that Duchamp "cheerfully masqueraded as an American style 'businessman'." He participated in the management of a cleaning and dyeing establishment, simply because it allowed him to designate himself as a "tinter" (a pun on peintre [painter] and teinturier [dyer]).[34] Thus, while it may seem that Duchamp is abandoning art when he turns to issuing bonds, this gesture emerges as yet another attempt to rethink art in speculative terms.

The public reception of Duchamp's bond verifies the speculative conflation of the artistic and the economic. Duchamp's issue of the Monte Carlo Bond was immediately valued not for its financial interest but as an artistic investment. In The Little Review (New York, Fall-Winter, 1924-25) we find an account of the public's reaction to this work:

If anyone is in the business of buying art curiosities as an investment, here is a chance to invest in the perfect masterpiece. Marcel's signature alone is worth much more than the 500 francs asked for the share. Marcel has given up painting entirely and has devoted most of his time to chess in the last few years. He will go to Monte Carlo early in January to begin the operation of his new company. (WMD, 185)

This account of Duchamp's work indicates that the "interest" of the public is not focused on the "interest" bearing possibilities of the bond but rather on the value of this work as an art investment, guaranteed by Duchamp's signature. Given the fact that Duchamp "gave up" painting, buying a bond assures getting a "masterpiece," since the artistic value of this limited edition work is guaranteed to exceed its actual value as a financial investment. The interest bearing value of this work as art exceeds its reality as financial security by invoking contingencies that extend beyond the authority and life of the artist into the speculative futures of posterity.

In order to illuminate the artistic implications of the Monte Carlo Bond it is important to consider Duchamp's letter to Jean Crotti (17 August 1952). In this letter Duchamp explains that artists are like gamblers, and that their reputation is made by the chance encounter of the work with the spectator:

Artists throughout history are like gamblers in Monte Carlo and in the blind lottery some are picked out while others are ruined. . . . It all happens according to random chance. Artists who during their lifetime manage to get their stuff noticed are excellent travelling salesmen, but that does not guarantee a thing as far as the immortality of their work is concerned.[35]

By identifying artists with gamblers in a blind lottery, Duchamp underlines the arbitrary way in which value is generated by the artwork. The successful artists are like traveling salesmen, able to capitalize on their chance encounters with the spectator, in order to valorize their work. By defining the viewer as someone who "makes the picture" alongside with the artist, Duchamp inscribes the work within a circuit of symbolic exchange. The artwork is thus redefined: it is neither an independent object nor does it belong to the author any more than the viewer. The artistic value of the work cannot be isolated from its social context: its display, consumption, and circulation. This is why "Posterity is a form of the spectator" (DMD , 76).

This redefinition of the artistic process as a gamble, which relies on the regard, or rather, "interest" of the spectator, leads to a radical challenge of the autonomy of painting as a discipline. As Duchamp explains to Crotti: "I don't believe in painting itself. Painting is made not by the painter but by those who look at it and accord it their favors; in other words, there is no painter who knows himself or is aware of what he is doing."[36] The authority of painting is fractured by the fact that the artist alone cannot confer value on a work. The appeal to the tradition, to those works whose value is ensured by the museum, is unreliable to the extent that the exhibition value of the work depends on institutional considerations. A last resort to individual judgment is also doomed to failure, since neither self-knowledge nor self-discipline can guarantee the future "interest" of the work. As Duchamp points out to Crotti, "don't judge your own work, since you are the last person to see it truly (avec des vrais yeux ). What you see is not what makes it praiseworthy or unpraiseworthy."[37] The individual judgment of the artist is shaped by the authority of one's education or one's reaction against it. Thus the effort to evaluate the work reveals the artist's subjective limits, the extent to which they are arbitrarily mediated by institutional givens.

Duchamp's refusal of aestheticism, the belief in painting for its own sake, is visible in Duchamp's earliest attempts to move away from painting and toward mechanical drawing and experiments with chance operations. The Monte Carlo Bond is issued in order to test a formula for turning the odds at roulette in the player's favor by "pitting the logic of chess against the luck of the gaming tables."[38] This work may be considered as

yet another instance of Duchamp's efforts to "can chance," as in Three Standard Stoppages and Dust Breeding (the photograph of dust in the region of the Sieves on the Large Glass ). The Monte Carlo Bond represents a deliberate effort to examine the speculative gamble entailed by both financial and artistic endeavors.[39] If the logic of chess is invoked in the context of this financial and artistic parody, this is by no means accidental, given the punning relation of chess (jeu d'échecs ) to checks (jeu des chéques ).[40]

How can the "logic" of chess be pitted against the "luck" of the roulette table? As we have shown earlier, Duchamp sees chess as a "visual and plastic thing," that is, not purely geometric, since it moves—"it's a drawing, it's a mechanical reality" (DMD , 18). According to Duchamp, playing a game of chess is "like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind by which you win or lose" (WMD , 136). In chess this mechanism is constituted by a strategy (a set of moves or decisions) of two opponents, who, in order to play, must literally put their "heads together." The case of roulette, however, is closer, as Hubert Damisch notes, to a head or tails game.[41] Yet roulette is more than a game of chance, since at each moment the player must decide on a number and a color.[42] But despite its arbitrary character, betting is often handled like chess, through predetermined strategies attempting to contain the chance element through the number of moves.[43]

The Monte Carlo Bond is issued by Duchamp to raise funds for a betting system for the roulette, which Duchamp describes as follows:

It's delicious monotony without the least emotion. The problem consists in finding the red and black figure to set against the roulette. . . . The Martingale is without importance. They are all either completely good or completely bad. But with the right number even a bad Martingale can work and I think I've found the right number. You see I haven't quit being a painter, now I'm drawing on chance . (WMD , 187; emphasis added)[44]

Duchamp's attempts literally to "draw on chance" (dessiner sur le hasard ) can be understood as an effort to recognize its plastic character by outlining its mechanism through a number of moves, thus, containing

it through a calculus of probability.[45] Rather than functioning as an invocation of pure contingency, chance, for Duchamp, is contextually defined, like value. Betting strategies have no meaning in and of themselves; they are indifferent. What matters, on the contrary, is the fact that these betting mechanisms contextualize chance, by literally "drawing" it in. The monotony of repeating a set of moves, with very small variations, uncovers the strategic and transitory outline of chance, an imprint of its fugitive passage.

Duchamp's financial gambit stages his artistic gamble as an artist whose reputation is, like life itself, "on credit." If art is a blind gamble, then the Monte Carlo Bond represents the obligation: it is a guaranteed interest-bearing certificate. As a speculative financial instrument, this bond provides the strategic mechanism for addressing the question of "interest" art. As Duchamp explains in a letter to Jacques Doucet (Paris, 16 January 1925): "Don't be too skeptical, since this time I believe I have eliminated the word chance. I would like to force the roulette to become a game of chess. A claim and its consequences: but I would like so much to pay my dividends" (WMD , 187–88). Duchamp's belief to have eliminated chance corresponds to his efforts to "can chance" (hasard en conserve ), by conserving or containing it. Duchamp's gesture emerges as a challenge to Stéphane Mallarmé's statement that "a throw of dice will never abolish chance." At issue for Duchamp is not the abolition of chance (which has little meaning) but rather, the effort to foil it by "canning" it, that is, preserving it as a strategic gesture particular to a set of determinations. Thus Duchamp's "canning" is also another way of "drawing" (dessiner ) on chance, like drawing checks (or drafts) on a bank. The Monte Carlo Bond enacts, in its "interest" generating potential as a financial document, the gamble that the artist is engaged in, in terms both of the artistic medium, and of the history and traditions that validate the work. If Duchamp is able to issue bonds as a way of securing and guaranteeing dividends on his "interest," this is because while art may be a gamble, the contextual logic of its operations is like a chess game. If we recall Duchamp's advice to John Cage, "Don't just play your side of the game, play both sides," we begin to see that Duchamp's success in "drawing on chance" is the result of playing the game of art from both sides, interchangeably and simultaneously as artist and spectator.[46]

Fig. 64.

Marcel Duchamp, Drain Stopper (Bouche-Evier), 1964 (obverse/reverse). Bronze.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Down the Drain: Numismatics as Art

. . . sooner find the Prosodia in a Comb as Poetry in a Medal.

—Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

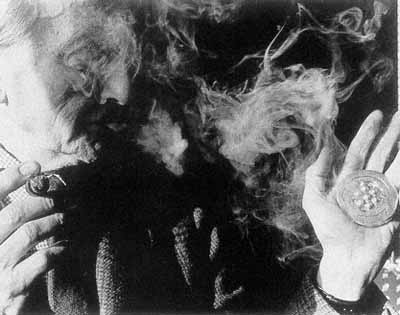

Among Duchamp's last ready-mades, we find two works, Drain Stopper (fig. 64) and Marcel Duchamp Art Medal (fig. 65), which bring us back full circle to Fountain , while simultaneously raising questions about value and its relation to art and monetary tokens. Drain Stopper is an item of hardware that Duchamp recycles from his bathroom in Spain, modified by being thickened with additional lead. Marcel Duchamp Art Medal is a cast from Drain Stopper in several versions, including bronze, steel, and silver editions, issued by the International Numismatic Agency (also known as the International Collectors Society, New York.[47] William Camfield considers Drain Stopper as a companion piece to Fountain , Morton Schamberg (1881–1918) and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's (1874–1927) God (circa 1918), and a part of Duchamp's "conceptual plumbing system."[48] Although plumbing and various items of hardware feature prominently in Duchamp's works, functioning as backhanded jokes on the sanctity of art, the reissue of the drain stopper as an art medal demands that the question of value in the context of mechanical and artistic reproduction be addressed once again. The invocation of plumbing in this "artistic" context becomes the literal conduit for examining how value is generated and expended, both as abstract property and as precise currency. The transformation of a drain stopper (thickened with lead) into art, and its reproductions, or rather transmutations, into coins and/or medals, attest to the expandable liquidity of art as a symbolic currency.

Duchamp's sole "rectification" of the Drain Stopper is to have thick-

ened it by adding more lead. This intervention may not seem to amount to much, particularly in terms of accounting for the recuperation of this object as a work of art. If we consider the gesture of adding lead as a pun, however, it seems that this object takes on new proportions. By thickening the drain stopper, Duchamp literally adds more weight to it, and figuratively suggests that he is now dealing with weighty matters. At first sight a joke, the Drain Stopper now emerges as an object whose literal gravity attests to its potential seriousness as a work of art. But is Drain Stopper a work of art? Duchamp's gratuitous gesture of choosing the drain stopper converts it into a work of art at the same time that it destroys the notion of the drain stopper as an art object. Thus, like Fountain, Drain Stopper is only provisionally a work of art; it is more like a stopper—a stop-gap measure or makeshift substitute (a pun on bouche-trou , its French title)—or a punctuation mark (indicating a pause or delay), rather than an actual art object. Poised between the wet (an allusion to painting as a purely material art "the splashing of paint") and the dry (a conceptual interpretation of art that includes mechanical reproduction), Drain Stopper acts like

Fig. 65.

International Collectors Society sales brochure cover, 1967. Shows Duchamp with

cigar smoke holding Marcel Duchamp Art Medal, which is based on Drain Stopper.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 66.

Leon Battista Alberti, Medallion, self-portrait, 1438.

From George Francis Hill, A Corpus of Italian Medals

of the Renaissance before Cellini Firenze: Studio per

edizioni scelte, 1984. Courtesy of The British Museum.

a regulative device controlling the transition between art and nonart. Like a pun, "stopper"—which means to regulate sound (as pitch in music) or light (as a photographic aperture)—mechanically triggers both the linguistic and the visual registers.

But "stopper" also has another meaning, that of securing one's chances in bridge (a stopper is a card that will ultimately take the trick in that suit). This latter pun inscribes the Drain Stopper into a gamble, which in the context of Duchamp's works is invariably a gamble on art. This gamble is explicitly played out in the transformation of Drain Stopper into Marcel Duchamp Art Medal , that is, from a ready-made into a mold for a series of artistic medals and/or numismatic coins. Duchamp's issue of an art medal (also known as Metallic Art ) would seem to be contrary to his iconoclastic position as an artist, particularly one who refuses to be identified as such. The fact that this art medal is also a numismatic coin, however, reminds the viewer of the coincidence of economic and artistic concerns, insofar as they embody ancient modes of mechanical reproduction, those of Greek founding and stamping.[49] Duchamp's Art Medal or Metallic Art is a Janus-faced representation of two opposing traditions.

The first is the commemorative tradition of the art medal, particularly popular during the Renaissance, which singles out the deeds or actions of an individual by immortalizing those actions through a motto and emblematic insignia. The second refers to the economic and symbolic value of coinage as an archaic measure and standard of exchange.

What then is the function of Marcel Duchamp Art Medal , as both a commemorative medal and a numismatic coin? As a commemorative medal, Marcel Duchamp Art Medal can be said to celebrate the emergence of a new type of art object: Fountain, the ready-made that literally flushed the traditional concept of art down the drain. Given Duchamp's concern that "Men are mortal, pictures too" (DMD , 67) and that "The onlookers make the picture," the effort to commemorate either the work of art or the artist takes on a "tongue and cheek" dimension. Duchamp's challenge of the commemorative aspects of art and its equation with the "rictus" of death is explicitly staged in his ironic self-portrait with my tongue in my cheek (fig. 46, p. 115).[50] This work celebrates Duchamp's specific contribution to art, his refusal to hold his "tongue in check," like other artists. Could this "tongue and cheek" work be considered as a belated commentary on the artistic medals of the Renaissance?

If we briefly consider the similarities between Duchamp's with my tongue in my cheek, Leon Battista Alberti's Medallion, Self-Portrait (1438) (fig. 66), and Matteo de' Pasti's Medal of L. B. Alberti (1448) (fig. 67), some surprising conclusions emerge. Alberti's medallion includes a profile self-portrait with a winged eye under the chin. De' Pasti's medal divides

Fig. 67.

Matteo de' Pasti, Medal of L. B. Alberti, 1448. From George Francis Hill, A Corpus of

Italian Medals of the Renaissance Before Cellini. Firenze: Studio per edizioni scelte, 1984.

Courtesy of The British Museum.

these elements, by separating Albert's profile and name on one side of the medal, while the reverse side depicts the winged eye surrounded by laurel wreaths, with the inscription Quid Tum.[51] The visual message of both Albert's medallion and de' Pasti's medal affirms the affinity of artistic conception with divine omniscience and glory. This visual message, however, is undermined on de' Pasti's medal by Cicero's motto "Quid Tum" ("What Then?"), which is believed to be a query on that which follows death.[52] Given Duchamp's critique of the artist as master of the visual, or "retinal euphoria," could it be that the winged eye under Alberti's chin may reappear transposed as Duchamp's swollen cheek, as the "tongue and cheek" signature of the artist as metaironist?

Now we may begin to understand Duchamp's interest in artistic medals, and in numismatics in general. The artistic medal, like the numismatic coin, is an archaic ready-made, whose double-faced (punning) visual and scriptural character captures the ironic nature of art: that artistic glory is not assured but on credit—conditional on the judgment of the spectator. The effort to commemorate the artist or the work, through medals or tokens, relies on the posthumous judgment of the spectator. This is why, according to Duchamp, "Posterity is a form of the spectator." Thus the commemorative gesture is merely a gamble whose interest lies in the hands of the future.

As a numismatic coin, Marcel Duchamp Art Medal immortalizes artistic glory by transforming it into coinage (commonplace, koinon , in Greek), that is a token of exchange. This medal/coin, however, no longer refers to the artist in a historical sense but rather to the history of the medium, since coins are the ready-mades of antiquity. The reproducible character of numismatic coins alludes to the origins of technology, the traditions of founding and stamping that precede the advent of the print medium and modern modes of mechanical reproduction by thousands of years. Coins are among the earliest artifacts of history; they are the first publications or impressions, whose characters give voice to history.[53] According to John Evelyn, coins are "vocal Monuments of Antiquity," the first and most lasting material traces of history.[54] Like the ready-mades, ancient coins embody contradiction, since they are simultaneously a material commodity (exchanged by virtue of material weight, for example, an ingot), and abstract currency (as medium and measure of exchange). Marc

Shell attributes this distinction between substantial value (material currency) and face value (intellectual currency) to the development of the polis.[55] The inscriptions on ancient coins attest to the transformation of the concept of value from value based on weight, to value based on political authority, that is, forms of legitimacy defined through symbolic exchange.

This tension between the coin as material and symbolic currency is compounded by a further ambiguity, that of the apparent contradiction of the coin as an artistic and as an economic object. This confusion is tied to the effects of inscription, be it verbal or visual, that conceptually transform a piece of metal into both an aesthetic and economic artifact. As Marc Shell observes: "The pictorial or verbal impression in this material qualitatively changes it (aesthetically) from a shapeless piece of metal into a sculptured ingot and, more significantly, qualitatively changes it (economically) from a mere commodity into a coin or token of money."[56] The minting of coins generates qualitative changes that transform the coin into both an aesthetic and economic object—domains that are considered to be mutually exclusive today. This coincidence of material and symbolic properties, as well as the processes of artistic reproduction and economic production, reveal Duchamp's interest in numismatic coins. Not only is a coin an archaic ready-made but it is also a pun, to the extent that its double-faced (Janus-like) character functions not as an object but as a mechanism that stages a new way of conceiving modernity. Marcel Duchamp's Art Medal numismatic coin suggests that mechanical reproduction, believed to define the origins of modern art, is present in antiquity before the emergence of the artistic as an autonomous domain. At issue is not the effort to de-historicize modernity by denying the preeminence of mechanical reproduction as its defining idiom, but rather to recognize the presence and social impact of its archaic manifestations. Instead of identifying mechanical reproductions as a purely technological intervention, Duchamp discovers in its socially symbolic character a conceptual potential, thereby demonstrating the intellectual overlap or punning relation of artistic and economic modes of production. In what is literally a "mirrorical return" on the opposition of art and economics, his Drain Stopper and Marcel Duchamp Art Medal suggest that coins are the "first" ready-mades, and that his own ready-mades are a mere extension and rectification of this tradition. By insisting on the conceptual dimension of

numismatics, Duchamp delays its economic impact, only to recover its intellectual impact. In doing so, Duchamp restores to the viewer a purely speculative concept of artistic production, which can only be thought through the expenditure of the terms that define economic production.

Duchamp's works challenge classical notions of value, by radically redefining both artistic reproduction and economic production through a revalorization of the intellectual potential of mechanical reproduction. This study has demonstrated that the concept of reproduction in Duchamp's works involves a new way of thinking about art. By exploring the "infrathin" interval separating an original from its copy, Duchamp is able to overcome the opposition between art and nonart. Taking mechanical reproduction as a given, Duchamp redefines the "object" as a set of impressions, like imprints drawn off the same template. Rather than considering the art object as unique, Duchamp redefines it as multiples, ready-mades that are like a limited edition of prints or coins, whose artistic value, like that of money, is negotiated by limited editions. In a photographic print of Duchamp's ready-mades in his studio (taken by Man Ray in 1920) there is a type chart from a French printing firm that serves to remind us of the significance of printing to our understanding of his work:

Printing is not such a recent invention as it is usually believed. Block printing had been used in China for more than sixteen hundred years; the Greeks and the Romans were familiar with movable stamps or types; the picture books that appeared in the early fifteenth century served as models for the experiments made by Gutenberg in Mainz in 1450 with wooden types.[57]

The history of printing and its affinity to techniques for founding and stamping marks the convergence of the artistic and the economic domains. By revalorizing printing as a medium that involves a conceptual potential, Duchamp does away with the opposition between the artist and the printer, between fine art and artisanal technique. This attempt to challenge the boundaries of art and technology explains his preference to define art as "making," and the artist as "craftsman" or "art-worker" (DMD , 16, 20).

Quaintly labeled by Robert Smithson as the "spiritualist of Woolworth," because of his relic-like, almost "spiritual" pursuit of the commonplace, Marcel Duchamp extends through his works the most radical critique of the notion of artistic value.[58] Foregoing both sentimentality and idealization, Duchamp explores how the notion of mechanical reproduction, based on principles of economic production and expenditure, alters the concept of artistic production. As this chapter has shown, however, Duchamp's appeal to and use of economic notions, such as commercial transactions and monetary tokens, is speculative rather than empirical. His interest in economics is conceptual involving an understanding of the mechanisms involved in the generation and expenditure of value. Duchamp is not concerned with the recovery of value in the classical economic sense but rather, in its expendability, for his works attest to the redefinition of notions of both artistic and economic production through the deliberate exploration of the notion of economic and artistic reproduction. Just as the ready-made challenges the autonomy of a work of art, not by postulating new value but instead by embodying its expenditure as "criticism in action," so does Duchamp's invocation of economic categories function as a way of challenging artistic categories. The result involves the subversion of art through the elaboration of an unartistic concept of art (nonart), leading to a critique of value as social and economic reality through its speculative expenditure.

According to Robert Lebel, Duchamp "derived his most obvious satisfaction from the very modesty of his profits." Duchamp's enjoyment in minimal economic returns corresponds to his efforts to maximize speculative "profits." It reflects Duchamp's artistic strategy as the master of "tongue and cheek" humor. Commenting on Duchamp's humor, Lebel suggests that its logic is more in the order of expenditure, than a rational economy based on interest:

If at all costs a rule must be discerned in Duchamp's humour, we think this is it: that it has to have a concrete result—consequently his humour is never gratuitous—but the flagrant disproportion between effort and result proclaims—with hidden noise—this result as the collapse, or better yet, the preposterousness, of a technocracy paralyzed by the very excess of its own efficiency.[59]

This disproportion between efforts and result in Duchamp's humour corresponds to the strategies of delay that Duchamp deploys in the economic domain in order to challenge the notion of value in the artistic domain. The invocation of a technocracy and even bureaucracy serves to undermine through the expenditure of efficiency the economic and artistic rationale of modernity. Like his father, who was a notary, and his symbolic father, François Villon, who celebrated his poetic legacy in his Testament , Duchamp commemorates his own artistic legacy as a stop-gap measure, a ready-made drain stopper that is also an art medal. Poised between an art that has lost its physical bite, and another, which can bite only because it is no longer art, Duchamp's stop-gap measure emerges as both predicament and testament. As the notary of modernity, Duchamp writes its most tortuous and deliberate "will," one whose language continues to this day to be "killingly funny."