Preferred Citation: Davis, Deborah, and Stevan Harrell, editors. Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb257/

| Chinese Families in the Post-Mao EraEdited by |

Preferred Citation: Davis, Deborah, and Stevan Harrell, editors. Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb257/

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The chapters in this volume were first presented at a conference on "Family Strategies in Post-Mao China," held at Roche Harbor, Washington, June 12-17, 1990. Financial support for the conference and subsequent editorial expenses were provided by a grant from the Joint Committee on Chinese Studies of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council. In addition to our nine fellow participants who worked so speedily and intensely on paper revisions, the editors would like to acknowledge the intellectual contributions of four other conference discussants: Anthony Carter, Shumin Huang, William Lavely, and Susan Watkins, as well as conference assistant Fu Yunqi. During the several phases of revisions, we also greatly benefited from the careful reading and thoughtful criticisms of two anonymous readers and Dorothy Solinger. For help with photo reproduction, we thank Joey Liao.

One

INTRODUCTION: The Impact of Post-Mao Reforms on Family Life

Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell

In the decade after the Communist victory in 1949, state orthodoxy created a new institutional and moral environment for Chinese families. The collectivization of the economy and the elimination of most private property destroyed much of the economic motivation that had previously shaped family loyalties, and the frontal attack on ancestor worship and lineage organization struck directly at the cultural and religious core of the extended family. It was not simply the case, however, as many predicted, that communism destroyed the traditional Chinese family. On the contrary, many key policies actually stabilized and strengthened families. For example, large investments in public health and famine relief dramatically reduced mortality; fewer infants died, more children survived to marry, old age became the norm, and people from all social classes had larger and more complex kin networks than had been possible before 1949.[1] Similarly, the severe restrictions on internal migration not only served the interest of the government in controlling individual autonomy, but they also intensified the flow of intergenerational aid because they tied most adult men (and their sons) to the villages and towns of their birth.[2] Thus the Communist revolution created contradictions. On the one hand, it undercut the power and authority of patriarchs and destroyed the economic logic of family farms and businesses. On the other hand, it created demographic and material conditions conducive to large, multigenerational households with extensive economic and social to nearby kin. In short, Chinese families between 1950 and 1976

[1] Edward Tu, Jersey Liang, and Shaomin Li, "Mortality Decline and Chinese Family Structure," Journal of Gerontology 44, no. 4 (July 1989): 157-68.

[2] Deborah Davis-Friedmann, Long Lives , 2d ed. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), chaps. 3-4.

survived and reproduced themselves within a paradoxical environment: the often repressive egalitarianism of communism permitted more Chinese parents and children than ever before to realize core ideals of traditional Chinese familism, while at the same time the revolution eliminated many of the original incentives for wanting to realize those ideals.

With the shift away from collectivization and toward entrepreneurship and privatization after 1978, the Maoist compromise between state policies and family self-interest entered a drastically altered environment. This was especially the case in the countryside, where the Deng reforms dismantled the People's Communes as a core political and economic unit and abruptly subcontracted more than 80 percent of all farmland to individual families on the basis of fifteen-year leases. Commune and village assets were similarly redistributed, rented, or sold to the highest bidders, and by the mid-1980s most rural families were operating in a political economy of family tenancy where the agents of state authority had less control over the labor, land, and loyalty of rural residents than at any time since the Land Reform of the early 1950s.[3]

In the cities, the Deng reforms were far more modest and incremental. Private entrepreneurship was encouraged rhetorically, but the great majority of urban residents remained wage earners, and most households were units of consumption.[4] Moreover, the paradoxical relationship between the Maoist state and traditional familism had never been as pronounced in the cities as it had been in the villages. Urban families had very few welfare functions, income was highly individuated, and relations with kin could be very weak. Few households had continued as units of production following the collectivization of artisan workshops and services in the mid-1950s, and generous medical and pension plans for all state employees reduced the

[3] For detailed discussion and varied interpretations of this process, see Philip C. C. Huang, The Peasant Family and Rural Development in the Yangzi Delta (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), 286, 321-22; Victor Nee and Su Sijin, "Institutional Change and Economic Growth in China," Journal of Asian Studies 49, no. 1 (Feb. 1990): 3-25; Sulamith H. Potter and Jack M. Potter, China's Peasants (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 158-79; Louis Putterman, "Entering the Post-Collective Economy in North China," Modern China 15, no. 3 (July 1989): 275-320; Helen Siu, Agents and Victims in South China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 273-90; Vivienne Shue, The Reach of the State (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), esp. 148-52; Terry Sicular, "Rural Marketing and Exchange," in The Political Economy of Reform in Post-Mao China , ed. Elizabeth Perry and Christine Wong (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 83-110.

[4] Deborah Davis, "Urban Job Mobility," in Chinese Society on the Eve of Tiananmen , ed. Deborah Davis and Ezra F. Vogel, 85-108 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990); Dorothy Solinger, "Capitalist Measures with Chinese Characteristics," Problems of Communism 38 (Jan.-Feb. 1989): 19-33. In December 1984 there were 86.3 million employees in state enterprises and 3.3 million working privately. By December 1989 these totals were 101 million and 6.5 million respectively. Zhongguo Tongji Nianjian (ZGTJNJ ) 1988 , 153, and Renmin Ribao (RMRB ), Feb. 21, 1990.

need for kin-based networks of mutual obligation. For these reasons, the main thrust of the Deng reforms in the cities had virtually no direct impact on the urban household economy. Nevertheless, urban families also entered into a new relationship with the state during the 1980s.

First, there was the challenge of prosperity, and if there were no great disparities of wealth, there was increasing economic differentiation and competition. Between 1978 and 1989 urban wages trebled, and consumer items such as color televisions, refrigerators, and electric fans, which in the 1970s had represented unimaginable luxury, became commonplace.[5] Equally important was the availability of the products of capitalist culture—Hong Kong and Taiwan soap operas, American movies and magazines, and the dance and video music of European and Japanese teenagers. Thus, while urban reforms did not commodify economic relationships within (and between) families as did decollectivization of agriculture, they did introduce a new range of cultural choices as well as the prosperity to permit individuals to act on preference, not merely respond to necessity.[6]

At the same time, however, the state continued to play a highly intrusive and coercive role vis-à-vis all Chinese families. Simultaneous with policies to decollectivize agriculture, encourage petty capitalism, and permit importation of the cultural products of the bourgeois West, the post-Mao leaders designed and implemented the most draconian birth control campaign in history. As first outlined in 1979, the birth control regulations prohibited any woman from having more than one child unless her first had died of a noninheritable disease or handicap. In one stroke of the bureaucratic pen, Chinese leaders decided that henceforth only half of all families would have a son to carry on the family name, that the sibling relationship would disappear, and that failure to use contraception would be a punishable offense. In terms of economic and political initiatives the reform leaders moved to disengage the state from control over land, labor, and markets; in terms of family reproduction they demanded that the state control the fertility of

[5] In 1978 urban staff and workers had an average annual wage of 615 yuan; by 1989 it had risen to 1,950 yuan. ZGTJNJ, 1989 (Chinese Statistical Yearbook ), 125; Guowuyuan Gongbao (GWYGB ) (Bulletin of the State Council), March 3, 1990, 85. For gains in consumer items, ZGTJNJ 1989 , 728.

[6] There are indications that the state-dependency of urban families may decline more rapidly in the near future. Nicholas Lardy reports that by 1990, 45 percent of China's industrial output was the product of the nonstate sector. While this includes many products of rural industries as well as urban collective enterprises, the growth rates of the private sector are about eight times those of the state sector, and continuation of current trends would mean that in a few years, a greater percentage of urban families in China will be unambiguously in the private sector and cast further adrift from the state-organized welfare net than is now the case. See Lardy, "Redefining U.S—China Economic Relations," NBR Analysis No. 5 , National Bureau of Asian and Soviet Research, Seattle, June 1991.

over one hundred million married couples. Rarely had the paradox of state power been more acute than between 1979 and 1983.

By the mid-1980s, however, the leadership had retreated from its original extreme position, and the ambitions of the state to dictate family size had moderated.[7] Rural families that could show that acceptance of the one-child limit would cause economic hardship or whose members were ethnic minorities were permitted to have a second or even a third child. And even in the cities, where pensions and social services eliminated the economic rationale for additional children, a variety of exceptions permitted some families a second birth.[8] Nevertheless, regardless of these modifications, the one-child policy continued to create tension and contradictions. For example, in designating the rural household as the basic unit of agricultural production, decollectivization increased the value of child labor. Yet the one-child quota demanded that families drastically curb fertility. If the one-child policy really succeeded, then approximately half the women born after 1955 would not have a son in their home to provide care for them in old age. There would have to be either a revolution in rural pension systems or massive construction of old-age homes. But with the collapse of the communes, rural pensions became even less extensive than they had been in the late 1970s, and village supports for the childless elderly precipitously declined in quality and coverage.[9]

In urban areas the clash between private and public interests created by the introduction of the one-child policy appeared in a different form. Thus even though young urban couples did not find the one-child campaign a threat to their immediate prosperity or to financial security in old age, they did perceive the campaign as an oppressive intervention of state power into an arena of family life that had remained private even during years of high political mobilization such as the Cultural Revolution.

The primary question, and the question that unites the chapters of this book, is this: What have been the initial consequences of these powerful and

[7] Karen Hardee-Cleaveland and Judith Banister, "Fertility Policy and Implementation in China 1983-1986," Population and Development Review 14, no. 2 (June 1988): 276; Steven Mosher, "Birth Control: A View from a Chinese Village," Asian Survey 22, no. 4 (April 1982); Delia Davin, "The Single-Child Family Policy in the Countryside," in China's One-Child Family Policy , ed. Elisabeth Croll, Delia Davin, and Penny Kane (London: Macmillan, 1985) 74; Joan Kaufman, "Family Planning Policy and Practice in China," Population and Development Review 15, no. 4 (Dec. 1989): 707-30.

[8] Birth control policies in minority areas were set locally and generally were looser than in Han areas. In urban areas, couples were permitted a second child when both spouses were only children, when the first child was seriously handicapped by a noninheritable defect, or when in remarriage the woman had had no children of her own. Nevertheless, second children are rare in the cities. Griffith Feeny, "Recent Fertility Dynamics in China," Population and Development Review 15, no. 2 (June 1989): 297-322.

[9] Deborah Davis-Friedmann, Long Lives , 110-11.

contradictory initiatives for Chinese families in the 1980s? In particular, our authors have asked: What have been the consequences for household composition, for marriage arrangements, for fertility decisions, and for provision of care to kin unable to compete in the more individualized and commodified society of the 1980s? In terms of size and composition, has the percentage of joint and extended families declined? Has marriage age fallen and have parents lost control over a child's choice of spouse? Has veneration of ancestors become more elaborate, and have lineages returned as key brokers of local power? Where, overall, are the lines now drawn between public and private responsibilities, between the Deng party-state and Chinese society?

Drawing on William Goode's classic study of families in periods of economic change and growing prosperity, most observers would predict that the reforms of the 1980s would encourage nuclear households more focused on conjugal loyalties.[10] With greater affluence, higher rates of urban living, and increases in long-distance migration, the Goode model predicts that the influence of corporate kin groups should decline, brideprice and dowry become less prevalent, divorce rates rise, women's rights improve, age of marriage increase, and parents lose control over children's courtship and mate choices.[11]

But the Goode model, which drew heavily on the experience of Western Europe and North America and could not have used material on China after 1960, never dealt with a state as intrusive and coercive as the Chinese. In Goode's overview, state regulation of family life was a consequence of industrialization and urbanization. Clearly, in the People's Republic of China (PRC) state power and policies have been the creators, not the creations, of a transformed society. Thus, for example, formal, corporate kin groups such as lineage organizations were specifically replaced by Communist Party organizations and a people's militia as early as 1950, and in most parts of China family shrines and temples disappeared even as China remained an essentially rural and agrarian society.[12] The Marriage Law of 1950 prohibited concubinage and child betrothal and permitted women to sue for divorce. Within the first three years of the law nearly two million divorces were granted,[13] and concubinage and child marriage became almost unknown by the end of the decade. We could go on at length documenting how state policies in the areas of public health, education, and migration similarly pushed Chinese families toward a "modern family" form at a speed unknown in European or American experience. But here we empha-

[10] William S. Goode, The Family (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall), 183-85.

[11] Ibid.

[12] C. K. Yang, The Chinese Family in the Communist Revolution (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1965), chap. 11.

[13] Beijing Review , Sept. 12, 1983.

size that because the state was so powerful in the past in shaping the resources and choices of family members and in defining the functional division of responsibility between private and public authorities, the retreat of the state during the 1980s may have permitted a revival of cultural preferences and economic forces that the Maoist state held in check but did not eliminate.

The interaction between these cultural preferences and economic forces is partially predicted by Jack Goody's models of the evolution of the family. These models stress the importance of property in shaping the functions a family holds in a particular society. For Goody the contrast is between periods when families derive their livelihood and social status from land or other productive resources they own or control, and periods when property belonged to the collective and status was based on political criteria. According to this model, extended-family ties and use of dowry and brideprice should weaken in the Maoist period but revive with the return of differences in social status within and among local communities after the Deng reform.[14]

In addition, it is possible that normative expectations rooted in sources independent of rational economic choices may prove decisive in an era when the party-state no longer intrudes as directly into cultural and religious life. Thus we may find by the late 1980s that in areas where government authority has dramatically retreated (most notably in rural areas) the dynamic of change for Chinese families may parallel that documented in John Caldwell's study of the demographic transition in western Africa, where family composition shifted in response to new ideologies rather than exclusively in response to new economic incentives and rationality.[15] Similarly, John Hajnal's study of marriage age and household type in Europe and Asia suggests that the key explanation of different household arrangements is likely to be culturally specific "rules for family formation" rather than the more global processes of urbanization, industrialization, or commodification.[16]

At the same time, in those areas where the state has strengthened its hand in the 1980s, we have a situation that is, as Susan Greenhalgh points out in chapter 9, unprecedented in world history and untouched by major theoreticians. The state, by implementing the planned-birth campaign, initially put itself at cross-purposes with just those cultural rules that shaped

[14] See Jack Goody, Production and Reproduction (Cambridge University Press, 1976), and The Oriental, the Ancient, and the Primitive (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

[15] John C. Caldwell, "Toward a Restatement of Demographic Transition," Population and Development Review 2, nos. 3 and 4 (Sept. and Dec. 1976): 321-66.

[16] John Hajnal, "Two Kinds of Pre-industrial Household Formation Systems," Population and Development Review 8, no. 3 (Sept. 1982): 449-94.

the prerevolutionary Chinese family. That it later had to compromise and loosen the restrictions, at least in the rural areas, testifies to the resiliency of those cultural rules in the villages. That the compromise was much less evident in the cities suggests that urban couples held values fundamentally different from those of their rural peers or that the power of the party-state was still so dominant that urban men and women could not act on their personal preferences.

Household Composition and Division

During most of the Maoist era, economic and political pressures fostered "family convergence." That is, in contrast to the two decades prior to 1949 when war, famines, and infectious disease prevented many from realizing the stable multigenerational households they desired, the overall legacy of the Maoist political economy was a remarkably uniform household structure, where differences in composition were increasingly due to the phase of the family life cycle, rather than to education or wealth, as had been true before 1949.

In the 1980s the new freedom to work outside of one's natal village and the introduction of the one-child campaign altered the external parameters shaping household size and composition, and in fact one can observe remarkable change within a short period. For example, in terms of average household size, families became noticeably smaller over the decade of the 1980s, and the number of households grew at a faster rate than the population.[17] In 1980 rural households averaged 5.5 members and urban households 4.4; by 1988 they had fallen to 4.9 and 3.6, respectively.[18] These declines, however, are explained almost entirely by declining fertility in response to the one-child campaign.[19] Thus macrodemographic indicators lend little support to an interpretation in line with Goode's initial predic-

[17] Between 1982 and 1987 the number of people living in families rose by 8.2%, from 971 million to 1,051 million, while the number of family households rose by 12.7%, from 220 million to 248 million. ZGTJNJ 1988 , 103, and Zhongguo Shehui Tongji Ziliao 1987 , 31.

[18] These figures should be treated as best estimates. For the 1980s figures there is no consistent national estimate, and for 1988 one must consider that after 1984 the definition of urban was relaxed to include many village residents in urban suburbs and also residents of small rural towns who had previously been excluded. The estimates used here are from Martin K. Whyte and William Parish, Urban Life in Contemporary China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 155 n.5, and ZGTJNJ 1989 , 726, 742.

[19] That is, because the percentage of women living with their husbands' parents upon marriage remained almost constant from the 1970s through the 1980s one presumes that it is the one-child campaign and not other factors that was most decisive. For estimates of these percentages, see Martin K. Whyte and William Parish, Urban Life in Contemporary China , 155 n.5, and ZGTJNJ 1989 , 726, 742.

tion that economic development accelerates the nuclearization and individuation of family life. Rather, in China in the 1980s households became smaller, but not necessarily more nuclear.

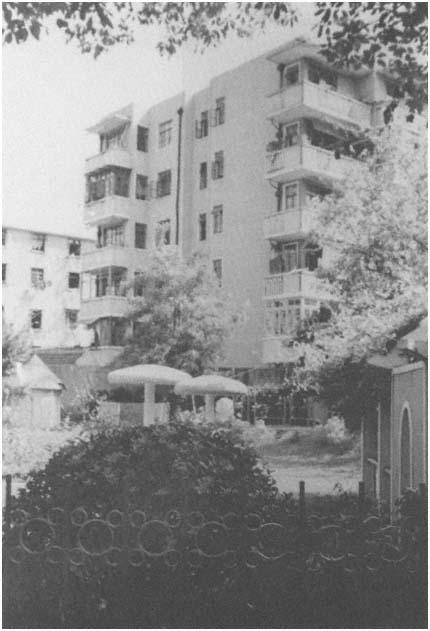

A closer examination of field research on family composition in both urban and rural areas indicates that the trends in household size and composition have not been uniform; rather, they vary by the economic incentives of the local economy or the strictness of the planned-birth campaign. By the mid-1980s the most numerous incentives to preserve extended families were found in (1) villages where, as in industrializing Taiwan of the 1960s, reliance on labor-intensive cash crops or cottage industries rewarded unified budgets with one or more married sons or (2) cities where housing shortages forced newly married couples to remain in their parents' homes.[20] In short, while it is clear that average household size declined, it is still not clear to what extent the reforms have altered family composition or the meaning of joint budgets and shared property.

This is particularly true in urban areas where, as Unger (chapter 2), Davis (chapter 3), Phillips (chapter 11), and Ikels (chapter 12) indicate, residence in separate households does not necessarily mean functionally separate families. Cooking, childcare, care of the elderly or disabled, and monetary transfers all frequently take place among geographically divided branches of "networked" families. In addition, as is especially clear in Davis's longitudinal study of Shanghai families (chapter 3), the fluidity of household membership is highly sensitive to stages of the family developmental cycle, and if a survey captures families at that point when children are in prime years for marriage, or when parents pass into years with high risk of chronic illness and higher mortality, households may change membership rapidly over a short period. In Davis's Shanghai study, where households were observed once in 1987 and then again in 1990, 60 percent of the reinterviewed households had altered their membership, a rate of turnover that Davis attributes not only to the age of her newly retired respondents, but also to the new prosperity and freer social environment of the eighties. Jonathan Unger's review of the Chinese five-cities survey of 1983 (chapter 2) suggests, however, that the instability of urban households may be a short-term response to current housing shortages, and that in the long

[20] Gu Jirui, Jiating xiaofei jingjixue (The economics of family consumption) (Beijing: zhongguo caizheng jingji chubanshe, 1985), 31; Isabelle Thireau and Mak Kong, "Travail en famille dans un village du Hebei," Etudes chinoises 8, no. 1 (Spring 1989), 7-40; Zhou Ying "Wo guo xiandaihua guocheng nongcun jiating" (Rural families in the transition to modernization), Renkou yanjiu , no. 2 (1988): 17-21. Zhang Yulin, "The Shift of Surplus Agricultural Labor," in Small Towns in China , ed. Fei Xiaotong (Beijing: New World Press), 186; William Lavely, "Industrialization and Household Complexity in Rural Taiwan," Social Forces 69, no. 1 (Sept. 1990): 235-51; Zhao Xishun, "Zhuanye jiating tedian qianxi" (An analysis of characteristics as specialized households), Shehui kexue yanjiu , 1985; Deborah Davis, chapter 3 of this volume.

term one would expect smaller, stable nuclear households, probably still linked in a variety of ways, to be the urban norm for both the newly married and the recently retired.[21]

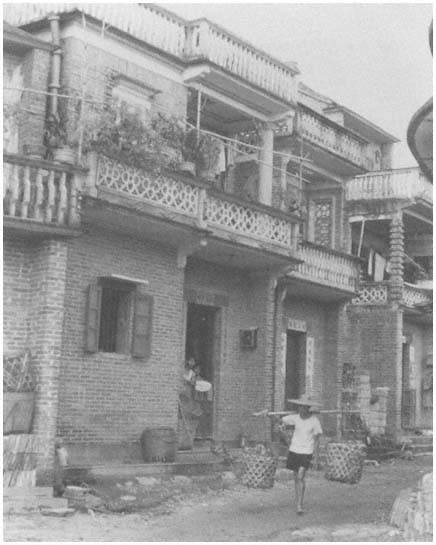

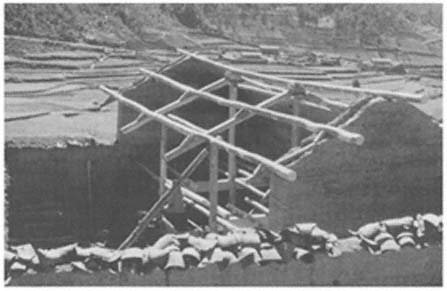

In rural areas, housing shortages are not the problem they are in the cities, but there still exist factors that either retard formal family division or encourage links between families already divided. It is important to note, however, that these factors operate differentially in the varying economic circumstances of different rural areas. For example, in the western part of the Pearl River delta, where Graham Johnson has conducted fieldwork since the early 1970s (chapter 5), the new wealth and openness to the outside world have revived connections with overseas relatives and produced new forms of emigrant families, which favor female-headed households and delayed family division. In the central and eastern parts of the delta, by contrast, the main outside influences have come from Hong Kong capital investment, and families there tend to be male-headed and to divide more quickly. Harrell's comparison of three villages in the Sichuan-Yunnan border region (chapter 4) also illustrates the importance of increased economic opportunities. Here, despite the more stringent application of the one-child policy in the richest village, households in that village were still more complex than in villages practicing subsistence farming, because wealthier families postponed household division.

Given the short time that has elapsed since the implementation of the reforms and the still limited access to national-level data, none of the chapters in this volume will conclusively specify the degree to which initial shifts away from collectivist economy and ideology determine the shape of Chinese households. Yet by documenting a range of outcomes, the chapters challenge arguments that posit a uniform or direct process of household simplification. Future scholarship will thus need to scrutinize both the rules of family formation and the shifts in state power and policy that proved so decisive in the past, and to situate findings in specific local contexts of cultural difference, as well as in economic and political change.

Marriage

In the first few years after 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) intervened directly to change many common elements of traditional marriage practices. The 1950 Marriage Law outlawed concubinage, child betrothal, multiple wives, and the sale of sons and daughters into marriage or prostitution. Village leaders and enterprise cadres exhorted the young people in their charge to delay marriage and in most cases enforced a policy of

[21] See the critique of this aspect of Goode's formulation in Peter McDonald, "Adjustments of Rural Family Systems," unpublished paper, 1987.

late marriage by withholding choice job assignments, welfare benefits, or promotions.[22] They also condemned traditional rituals and elaborate feasts. Most of the ideals behind such policies were inspired by Engels's The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State , but the desired outcomes were also some of the very trends predicted by Goode for industrializing families. Success was mixed: the state succeeded in holding the line against such pre-communist practices as minor marriage and concubinage, but was much more successful in the cities (Whyte, chapter 8) than in the countryside in popularizing frugal weddings or eliminating brideprice and parental control of mate choice.

In September 1980 the National People's Congress passed a new Marriage Law, ostensibly motivated by a decision to strengthen the rule of law and bring the law more in line with practice. But in some areas the law actively encouraged "retrogression" to earlier practices of the precollectivist era. For example, the new law sanctioned minimal ages of marriage (20 for women and 22 for men [article 5]) that were significantly lower than the actual practices of the Cultural Revolution decade, and aside from a single sentence prohibiting "exaction of money or gifts" (article 3) there seemed to be no effort to control wedding expenses.[23] And in fact, in the decade following the passage of the new Marriage Law, marriages did indeed become decidedly "less modern" and more like those of the precommunist era. In 1978 the average age of marriage for women was 22.4 for rural brides and 25.1 for those in the city.[24] By 1987 the average age of marriage for all women had fallen to 21.0 years,[25] and teenage marriages and even child betrothal had begun to reappear in rural areas throughout the country.[26] The 1980s also saw an explosive increase in the overall expenses associated with marriage, as well as the return of lavish dowries and high brideprice.[27]

[22] Whyte and Parish, Urban Life in Contemporary China , 113, found an average age of marriage for weddings between 1974 and 1978 to be 28.5 for males and 24.4 for females. William Parish and Martin Whyte, Village and Family in Contemporary China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 163, found average age at weddings between 1968 and 1974 to be 24.8 for males and 21.1 for females.

[23] For an English translation, see Beijing Review , March 16, 1981, 24-27.

[24] Zhongguo Shehui Tongji Ziliao 1987 (Chinese Social Statistics for 1987) (Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe, 1987), 29.

[25] RMRB , Feb. 19, 1989, 8.

[26] The Hong Kong paper Ming Bao , on April 20, 1990, 8, reported 3.5 million underage marriages in 1988; RMRB , March 31, 1989, 4, summarized a recent survey by the Women's Federation on betrothals of rural school girls.

[27] Gu Jirui, Jiating xiaofei jingjixue , 344; Qian Jianghong et al., "Marriage Related Consumption," Social Sciences in China , no. 1 (1988): 208-28; Beijing Review , Dec. 25, 1989, 32; Sulamith H. and Jack M. Potter, China's Peasants , 209; Burton Pasternak, Marriage and Fertility in Tianjin, China: Fifty Years of Transition , papers of the East-West Population Institute, no. 99 (1986), 28-31; Martin K. Whyte, "Changes in Mate Choice in Chengdu," in Chinese Society on the Eve of Tiananmen , ed. Deborah Davis and Ezra F. Vogel, Contemporary China Series (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 203.

Despite these clear trends away from Maoist preferences, however, not all of these shifts occur uniformly among rich and poor, or from region to region. Helen Siu (see chapter 7) suggests, in fact, that the trend follows Goody's general observation that dowry becomes more important in areas where competition for status is acute and parents need to endow their daughter richly in order to achieve a "good marriage." In her study of a Pearl River delta market town and its surrounding villages, she shows how connections to Hong Kong have greatly intensified the more general trend toward commodification and producing for the market. Overseas Chinese have invested heavily, and recent émigrés return frequently with gifts of consumer items and cash. As in the areas visited by Graham Johnson, families are eager for their daughters to marry an Overseas Chinese, and local men find themselves disadvantaged in the marriage market.

In the market town described by Siu, dowry had been a major investment among the precommunist merchant elite, but in the 1980s it became pervasive among many strata, as parents used a daughter's marriage to stabilize and advance family or individual interests in an era when the local political economy was in tumult and the Maoist bureaucratic hierarchies were in decline. In the outlying villages, at the same time, a shortage of female labor, caused partly by pressure on young women to marry into more prosperous town families, drove up brideprice. Thus in Siu's work we find an excellent example of where the immediate results of greater commodification and openness to the West were elaborate multigenerational investments that advanced corporate family interests as well as individual aspirations of the parents and the newly married couple. We also find traditional patterns seemingly revived but, as Siu herself points out, for purposes often quite different from those of precommunist years: village families pay high brideprices as much to keep their children from migrating away entirely as to assure the productive and reproductive contributions of future daughters-in-law.

Similar effects can be seen in the patterns of marriage ages and of village endogamy and exogamy, as is shown in Mark Selden's study of Wugong, a former model village in central Hebei, a region where brides were traditionally three to five years older than their husbands. During the collective era, age at marriage rose, and a long-standing prohibition against intravillage marriage fell into disregard. After only a short experience with economic decollectivization and political liberalization in Wugong, however, age at marriage fell, and village daughters were again marrying at a slightly older age (23.4 years) than village sons (22.7 years), although the traditional pattern of brides two to four years older than grooms did not appear and intravillage marriage continued. In other words, some but not all traditional preferences reappeared after the reforms. A similar pattern obtained in the relatively poor Shaanxi villages studied by Susan Greenhalgh in 1988 (chapter 9), where Maoist ideals of late marriage quickly

crumbled, and the average age for a bride's first marriage fell precipitously from twenty-three to twenty between 1979 and 1987.[28]

Based on a survey of almost six hundred women in Chengdu, Martin Whyte shows somewhat similar patterns in urban areas. Some but not all precollective wedding practices have reemerged—for example, weddings, simple and cheap under Maoism, have once again become more elaborate in the reform era, but freedom of choice of spouse, introduced in the collective era, has remained under the reforms. In addition, the considerable social class variation in marriage practices in the precollective era was largely eliminated during the period of "high Maoism," but in the reform era, Whyte finds, even though weddings have once again become more elaborate, there has been no reemergence of class-stratified patterns in freedom to choose a mate, elaborateness of weddings, presence or absence of a dowry, the share of the wedding expenses paid by the couple, or the pattern of postmarital residence. Whyte provisionally attributes this to the continuation in the 1980s of a "rank/network/bureaucracy" social system that originally replaced the "status group/class/market" system with the imposition of state socialism in the 1950s. According to this logic, urban wedding behavior had not revived class-based differences in the 1980s, as had rural behavior, because the urban society of the 1980s was fundamentally still what Andrew Walder called "communist neo-Traditionalist,"[29] basically untransformed from the social structure of the Maoist period.

The diverse paths of change in marriage practices might cause us to reexamine a claim made in the important earlier study of urban marriages in the late Mao era carried out by Whyte and William Parish. In that study, the authors emphasized that after 1949 urban Chinese marriages resembled those of other developing societies. In line with Goode's predictions, there was a steady rise in marriage age, widespread disapproval of arranged marriages, and a convergence in the behavior of mate selection across different economic and educational strata. What was distinctive about China was the speed of the changes, the low cost of weddings, and the absence of a dating culture, characteristics Whyte and Parish attributed to CCP organizational and political resources not present among other rapidly modernizing or industrializing agrarian societies.[30] Nevertheless,

[28] This pattern, however, was not uniform over the whole country either. In the three villages studied by Stevan Harrell in southernmost Sichuan, marriage age continued to be low from the 1950s through the late 1980s—there late marriage was never rigidly enforced in the collective era, and so there was no perceptible drop with the new law of 1980 or with the rise of the family farming economy. See Stevan Harrell, "Aspects of Marriage in Three Southwestern Villages," China Quarterly 130 (June 1992): 323-37.

[29] See Andrew Walder, Communist Neo-Traditionalism: Work and Authority in Chinese Industry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

[30] Whyte and Parish, Urban Life , 147-51.

they stressed that the causes of change lay primarily in the economic and social transformation and only secondarily in specific government policies aimed at reform of marriage practices.

Much of the "backsliding" that has gone on in the 1980s, however, makes the attribution of causality much more doubtful. Many of the changes in marriage during the Maoist era fulfilled Goode's predictions because the Chinese state was operating according to a political agenda, derived from Engels, that made behaviors that for Goode were predicted outcomes into explicit policy goals. The state planners probably thought they were just helping the inevitable along, but in fact they were creating a structure of inevitability much more narrowly restricted than the structure that would have been created by economic and cultural transformations. During the decade of the eighties, the state withdrew from close supervision of the local rural economies, and there was no single opportunity structure in the countryside. In the cities, the structure remained much more uniform, but several of its parameters evolved rapidly away from the Maoist period ideal, particularly the cost and lavishness of weddings. In retrospect, then, it seems that state policy had more effect in the Maoist period than Parish and Whyte originally gave it credit for, though the situation during the reforms is much more in tune with their model of primary causality residing in social and economic change. In any case, the situation is clearly more complex than any unilineal model of change would predict.[31]

Childbearing

The relative importance of state power and economic imperatives is addressed with regard to a different area—fertility—by Susan Greenhalgh and Hill Gates in chapters 9 and 10. Although there is considerable disagreement about the fertility levels of the Chinese population before the early decades of the twentieth century,[32] it is clear that from the 1920s through the 1950s virtually all Chinese couples considered it essential that they have enough sons to ensure that at least one would grow to maturity and continue the patriline. Given the high mortality of infants and young adults during these war-ravaged decades, the goal of one surviving son encouraged most women to bear as many children as possible.

Throughout most of the 1950s the Chinese government took a decidedly

[31] For example, see Arland Thornton and Thomas E. Fricke, "Social Change and the Family: Comparative Perspectives from the West, China, and South Asia," Sociological Forum 2, no. 4 (1987): 746-79.

[32] See the debate between Arthur P. Wolf, in "Fertility in Prerevolutionary China," and Ansley J. Coale, in "Fertility in Rural China: A Reconfirmation of the Barclay Reassessment," both in Family and Population in East Asian History , ed. Susan B. Hanley and Arthur P. Wolf (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

pronatalist position and did little to alter traditional expectations of marital fertility.[33] After 1960 there was a shift, and the government began to promote birth control in cities, and urban fertility began to diverge from national trends (table 1.1). The real revolution, however, occurred during the decade of the 1970s when, as a result of both explicit government birth control campaigns and altered definitions of ideal family size, China's total fertility rate (TFR) fell from 5.8 in 1970 to 2.7 in 1978,[34] a drop without historical precedent in a society that had not suffered war, epidemic, or famine, and a rate that resembled that of Canada more closely than those of more comparable countries, such as Brazil, Iran, or Mexico.[35] In short, even in advance of the one-child campaign, Chinese women, in both rural and urban

[33] There is a vast literature on Chinese fertility shifts. In this chapter we have relied primarily on work that has drawn on demographic work in the 1980s. Judith Banister, China's Changing Population (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987); William Lavely and Ronald Freedman, "The Origins of the Chinese Fertility Decline," Demography 27, no. 3 (August 1990), 357-67. Burton Pasternak, Marriage and Fertility in Tianjin, China: Fifty Years of Transition ; Peng Xishe, "Major Determinants of China's Fertility Transition," China Quarterly , no. 117 (March 1989), 1-37.

[34] Judith Banister, "Population Policy and Trends in China 1978-1983," China Quarterly , no. 100 (Dec. 1984): 717-41.

[35] Statistical Abstract of the United States 1982-83 , 661.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

areas, had reduced their fertility well below that of their peers in other developing nations.

In contrast, however, to the changes demanded by the one-child campaign, the shifts of the 1970s had been achieved without requiring half the population to forgo a son or all couples to risk a childless old age if their singleton died. Balanced against the substantial decreases in infant and child mortality rates, in fact, these early birth-limitation campaigns may not have produced much perceived difference from precommunist expectations of having a son survive adulthood. The one-child campaign unveiled in 1979 marked, therefore, a very radical departure from past efforts and, particularly in light of the new opportunities for considerable return on child labor, created the conditions for direct confrontation between family and state self-interest.[36]

Based on observations in the late 1980s, however, the impact of the policy is not clear-cut. That is, when one examines the overall trends in fertility and parity for the decade of the eighties, it appears that overall fertility has declined very little (see table 1.1). However, when one examines trends in terms of percentage of births that are third- or higher-order parities, the one-child policy has had a significant impact (table 1.2). The question, therefore, is what were the conditions that produced this record of mixed success. Was it the uneven efficacy of birth control cadres who had to rely primarily on intimidation and coercion, or the more universal pattern of variation by the economic and educational status of childbearing women?

Greenhalgh's and Gates's chapters, both based on 1988 fieldwork, confirm previous conclusions that the two-child norm has been widely

[36] Steven Mosher, "Birth Control: A View from a Chinese Village"; Delia Davin, "The Single-Child Family Policy in the Countryside," 74.

accepted,[37] but they focus more extensively on the particular balances of socioeconomic incentives and state coercion that favor compliance and very low fertility. Working in Shaanxi periurban villages, Greenhalgh found that by 1987 local cadres had essentially given up enforcing a one-child policy: the fining system had collapsed, second children were spaced even more closely than they had been in 1980, marriage age had dropped to twenty, and more than 8 percent of women married in their teens. On the other hand, a two-child family appeared to be the mode, and if a family had two boys or a boy and a girl, parents were in most cases satisfied that they had achieved an ideal size. In short, Greenhalgh concludes that as a result of successful bargaining with local cadres, village families had "peasantized" population policy: it was not the state's enforcement power but the rational calculations of peasant families that brought rural fertility close to compliance with state goals.

In Gates's study of small-scale entrepreneurs in urban Chengdu and Taiwan, the focus is also on negotiations. But in this case the author stresses negotiations between a wife and other members of her (husband's) family. Interviewing several generations of women who bore children both before and after 1949, and across all decades since 1949, Gates finds that women entrepreneurs rationalized childbearing as a means to meet specific obligations, and that their willingness to have a child depended on their own individual relationship to the market. In the PRC during the one-child era, there is of course little official space in which to negotiate. There is a question, however, about delaying the first birth that can be (and is) subject to negotiation, and also there is a question about the degree to which a one-child norm would ever be acceptable to Chinese women and their families given pronatalist preferences and behavior in earlier decades and in Taiwan. Based on the Chengdu respondents, Gates finds a clear relationship between increased capital assets and what she terms "antiphiloprogenitivism." That is, urban petty capitalists do not desire more than the minimum number of children to meet their family obligations; therefore, in the 1980s when the state limited them to one child, these particular women found no difficulty in accepting that limit.

Certainly Gates's respondents represent only a small minority of urban women, since most urbanites are employed in state enterprises where they have no personal assets and no entrepreneurial ambitions. However, it is also true that the model of kinship that Gates has defined, whereby a woman's childbearing desires can be explained in terms of how her particular household relates to the larger economy, is in no way limited to urban

[37] After completing four rural surveys in Fujian and Heilongjiang during 1987, Joan Kaufman found that enforcement at village level appeared weak and that while the household-responsibility system rewarded higher fertility, a two-child norm appeared to have been widely achieved; Joan Kaufman, "Family Planning Policy and Practice in China."

petty capitalists, but rather establishes a conceptual model that could be applied to all women, whether they live in cities, towns, or villages.

In fact, this conceptual model clearly fits with Harrell's data on the wealthiest of the three villages he investigated, where leading economic roles for women, readier acceptance of childbearing limits, and possibly even a tendency to pool capital, were most pronounced among entrepreneurial households. Given this parallel, it would be prudent to revise the ubiquitous urban-rural dichotomy and replace it, at least provisionally, with a three-way division between subsistence farmers, urban state/collective employees, and a third, entrepreneurial category that spans both cities and villages. And given the direction of China's economy toward an ever-larger private sector, we can expect that entrepreneurial households, a tiny minority at present, will come to constitute a much greater percentage of all Chinese families in the near future.

It is this third category of households that calls most sharply into question the unilineal theories of family change. While these petty capitalist households, as Gates and Harrell both suggest, do exhibit the predicted trends of lower fertility, at the same time they may well tend to greater household complexity because of capital and labor-pooling needs. In addition, as property owners they are more likely to be concerned with dowries, wedding banquets, and other forms of conspicuously displayed wealth. Whether or not the entrepreneurial category gains further prominence, the very fact that their family behavior differs from that of agriculturalists or state-sector employees once again points out that the process of family change, relatively homogeneous in the Maoist period, has become complex and heterogeneous.

Dependents and Family Obligations

One of the explicit rationales for several aspects of the ideal model of traditional Chinese family organization, with its early and universal marriage and strong intergenerational interdependencies, was that such a system not only facilitated the continuation of the patriline but also provided for the frail and the vulnerable. If the family were to modernize in accord with a Marxist blueprint, families would relinquish these responsibilities, and the weak and the needy would turn first to public institutions. To quite an extraordinary degree, the Chinese Communist leadership in the collectivist period realized a large portion of these Marxist ideals. As might be expected in a state where the proletariat is by definition the vanguard, the greatest investments were made in cities, and within ten years of 1949 urban families enjoyed free primary education, free basic health care, and very inexpensive housing. In the countryside, where programs were funded by local communities and per capita fees, services were far more meager

and families continued to be the primary source of aid for the young, old, and disabled. Nevertheless, money from central coffers subsidized construction of schools in small villages throughout the country, colleges sent thousands of new graduates to county and commune schools and clinics, and village cadres created welfare funds that supported cooperative clinics and guaranteed subsistence to all village households.

With the collapse of the commune as a political and economic unit, and the rapid commodification of rural labor, the structural supports for public welfare collapsed in the countryside and fees for services rapidly multiplied.[38] Tuitions became onerous, village welfare funds served only the most destitute, and most small clinics became privately run.[39] Even in the cities, where welfare provisions remained structurally intact and fully funded, there were also steps to monetize. Urban parents paid more extraneous school fees, and firms began to exclude some services from the health benefit. Bribes to medical personnel became more ubiquitous, and the cost of medicines not covered by health plans rose very fast as pharmacies and clinics tried to increase profits.[40] In short, the reforms noticeably reduced collective responsibility for care of the young, the sick, and the needy, and increased the financial burden of illness and disability on individuals and families.

The question here is how these cutbacks in public services have affected family behavior, and in particular whether the retreat of the state has affected family solidarity. Because of the more complete decollectivization of rural services, one would assume that village families have been most immediately and decisively affected, and that individuals who come from the poorest households or have the weakest network of extended kin will find themselves less secure than they had been under the collective. Conversely, given new incentives for individuals to develop family- and kin-based strategies of cooperation, one would also expect a resurgence of such risk-sharing institutions as burial societies, crop-watching associations, or lineage schools and scholarship funds. Reports from Guangdong, where lineage activities were traditionally strong, suggest that kinship associations have begun to assume welfare functions that were previously the responsibility of the village or commune.[41] But as Michael Phillips, working in

[38] Deborah Davis, "Chinese Social Welfare," China Quarterly , no. 119 (Sept. 1989): 577-97.

[39] Gail Henderson, "Increased Inequality in Health Care," in Chinese Society on the Eve of Tiananmen , ed. Deborah Davis and Ezra F. Vogel, 263-82 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[40] Ibid.

[41] See chapter 5 in this volume, by Graham Johnson; also Sulamith H. and Jack M. Potter, China's Peasants , 266 and 337; and Helen Siu, "Recycling Tradition," Comparative Studies in Society and History 32, no. 4 (Oct. 1990): 765-94.

Hubei province, noted during discussion at our conference, lineage resources appear to be available for only a tiny percentage of rural families. Thus, at his hospital he has observed that the increased cost of hospital care and the collapse of collective medical insurance programs in the countryside have reduced the number of rural patients and shortened the stay of those whose family members are able and willing to pay the fees. Similarly, studies of rural enrollment rates show marked declines in entry to school and decreased completion rates from primary and secondary school.[42]

In this volume there are no studies of the impact of Deng reforms on rural families in distress. But in chapters 11 and 12, which analyze caregiving dynamics in urban families, we do find evidence of negative impact. In the families of schizophrenic patients he treated, Phillips observed how the more individuated reward structures and higher medical fees of the late 1980s increased tension between two core values of urban Chinese families: the desire to sacrifice for dependents, and the commitment to "judicious investment of family resources . . . [for the advancement] of the social status of the family." In the Mao years, when many employers were rather lax in their demands of the least skilled workers, families could find a place for their schizophrenic child or spouse. Treatment costs were covered by employers, and although families were often deeply ashamed by their relative's behavior, they still could maintain a veneer of normalcy. Moreover, the loss of this individual's full economic potential did not pose heavy financial costs in the absence of many alternative demands for surplus income. In the more competitive society of the 1980s employers can refuse to employ mentally ill people even for menial jobs, health insurance has reduced payments for medication, and the family, because of its heavier medical expenses and lost income potential, can become impoverished. In general, the cost to families of having a profoundly ill member increased during the reform years, and families with the fewest social and economic resources were hardest hit. Families continued to assume the main obligations, but financial burdens made the disability more immediately costly, and greater competition at the workplace and more approval of individualistic striving undermined the willingness of some family members to sacrifice for another.

In the final chapter of this volume, Charlotte Ikels discusses what the reforms have meant for elderly residents of Guangzhou. Overall, there have been no efforts to undermine financial security; in fact, over the decade of the 1980s pensions grew at about the same rate as wages, and the percentage of urban residents over age sixty who received a pension steadily rose.[43] However, for the same reasons that Phillips found schizophrenics more of a burden on their kin, so Ikels found Guangzhou elderly and their

[42] RMRB , Feb. 15, 1989, 1; Aug. 7, 1989, 1.

[43] Davis-Friedmann, Long Lives , 107-16.

children increasingly aware of the costs of providing services to the weakest and least socially active. Among her respondents the reforms did not directly reduce security or increase family conflict, but they did intensify anxieties about the future, and Ikels found elderly parents reaching out to make themselves useful or less needy, in anticipation of a day when they would need to draw heavily on the goodwill and filial loyalty of one or more of their children.

Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era

Through the presentation of these research findings, we hope to establish a baseline, and perhaps even set an agenda, for future research on families in China. We believe that the approach taken here, looking at family behavior as the adaptation of cultural rules to changing and diverse political and economic circumstances, helps us do several things. It takes us beyond either/or debates about culture and political economy, or about state policy versus economic change, to examine the interaction of these factors. It moves us away from sweeping generalizations about the Chinese family, or even the urban or rural Chinese family, to consider different outcomes of adaptation to different circumstances. And it allows us, on the basis of empirical case studies, to begin to make certain generalizations, not so much about outcomes as about processes.

The first generalization is that many key characteristics of family life during the Maoist period—high age of marriage, elimination of polygamy and concubinage, reduced (or absent) dowry, and weak corporate kin groups—which earlier students of family life such as William Goode had expected to find as consequences of industrialization, may in the case of China be best explained by family laws, which Goode had presented as a consequence, not a cause, of change.[44] Thus we suggest that the Maoist period witnessed a rapid shift away from corporate kin groups, elaborate weddings, concubinage, and early marriage, not because the economic and social transformations of the 1950s and 1960s made such changes irresistible to individual men and women, but because the state drafted laws or regulations that required immediate compliance.[45] Therefore, it is in the interaction of preexisting "family culture" with both convergent processes of industrialization and particular state policies that we should look for explanations of the complex patterns of family changes in revolutionary China.

The second generalization responds to the resurgence of traditional

[44] Goode, The Family , 186.

[45] This point has also been made by William Lavely and Burton Pasternak in their studies of fertility decline. Lavely and Freeman, "The Origins of the Chinese Fertility Decline," and Pasternak, Marriage and Fertility in Tianjin .

rituals, ceremonies, and family behavior such as child betrothal, bridewealth, lavish dowry, and joint family households, that initially appear to document a "step backward." None of these traditional practices should be interpreted as a simple return to the status quo ante. Rather, the return of precommunist festivals and traditions is first and foremost a response to the post-Mao political economy, and by examining these rituals in their contemporary context one may identify the emergence of new boundaries between kin and nonkin and the emerging character of intergenerational obligations in an era of political uncertainty. Thus, from such material we can perhaps more clearly see the family ideals and the rules guiding household formation that Caldwell and Hajnal found decisive but that currently are still not well articulated in scholarly discussion of China.

The third generalization is that, when explicit state policies do not force homogeneity, the general tendency is for Chinese families to adapt their marital, parental, and welfare strategies to local economic conditions. Recent family behavior does not converge on a uniform pattern of extended patrilocal households with strong corporate links and equal inheritance among all sons, much less on an evolutionarily determined isolated nuclear family. Nor is there an urban form and a rural form. Instead, today's Chinese mainland, like twentieth-century Hong Kong and Taiwan, displays a variegated mosaic of family forms and behaviors, each demonstrating the adaptation of basic principles to differing conditions.

In his introductory comments to Louise Tilly and Joan Scott's study of English and French families in the early years of the industrial revolution, historian Michael Katz remarked:

A close relationship exists between the organization of the family and the mode of production at any given time. Yet [Scott and Tilly] also show that the relationship is very complex. Domestic organization does not change quickly or easily. Families adopt complex strategies which enable them to preserve elements of customary practices in altered circumstances, and the family patterns that emerge represent adaptations, complex compromises between tradition and new organizational and social structures.[46]

Observations of Chinese families during the economic and political upheavals of the 1980s confirm much of what Katz found to be the case for European families in another era of rapid change. But as we and most of the authors in this volume stress, in China neither the family nor the individual is as autonomous as were Europeans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Because during the second half of the twentieth century a powerful, intrusive Chinese state frequently rewrote the basic "laws" of economic exchange and terms of trade, the "complex compromises" that Katz

[46] Louise A. Tilly and Joan W. Scott, Women, Work, and Family (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978), xi.

found in Tilly and Scott's discussion of gradual shifts from the household as a mode of production to a family wage economy may be quite different for the PRC.

As is obvious in our description of the several ways in which the Communist revolution served traditional family goals, and in the ways in which families have prospered under the Deng reforms, members of Chinese families, like those of Europe and North America, seek to maximize their resources under different modes of production. Economic constraints are critical in family form and family behaviors, but economics alone cannot capture all the external constraints. Politics also matter, and no study of Chinese families can be complete unless it is as concerned with the state as it is with the economy. And as everywhere, the changes that stem from politics and economics all play themselves out against the background of a Chinese family culture that does change, but only slowly.

PART ONE

HOUSEHOLD STRUCTURE

Two

Urban Families in the Eighties: An Analysis of Chinese Surveys

Jonathan Unger

During the 1980s our knowledge of the shape of urban family life in the People's Republic of China increased several fold. Some quite excellent research, to be sure, had been conducted by Western scholars in the 1970s through interviews with emigrants in Hong Kong.[1] But it was only in the eighties that Western sociologists, anthropologists, and demographers at long last were able to conduct research inside China. And perhaps more important, it was only in the 1980s that China's own social scientists were able to begin serious research of their own.

Under Mao, scholarship in the social sciences had been sacrificed to the whims and dictates of politics. The government had deemed sociology potentially dangerous, in that it intruded on the Party's desire to hold a monopoly over analyses of society. All sociology departments were abolished in 1952,[2] and it was not until 1979-80 that three departments—in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai—were reestablished by the government as a first step in rebuilding a capacity to monitor and analyze social problems. Sociology departments soon opened at universities in other cities, with staff hurriedly recruited from other disciplines.

Though the field was still new, a substantial number of Chinese surveys on urban family composition were conducted between the years 1982 and 1985. The most significant of these projects was a coordinated effort in 1982-83 to study family patterns of eight residential districts in five of

[1] See, for example, Martin King Whyte and William L. Parish, Urban Life in Contemporary China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), and Deborah Davis-Friedmann, Long Lives: Chinese Elderly and the Communist Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983).

[2] Martin K. Whyte and Burton Pasternak, "Sociology and Anthropology," in Humanistic and Social Science Research in China , ed. Anne F. Thurston and Jason H. Parker (New York: Social Science Research Council, 1980).

China's major cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Nanjing, and Chengdu. The more than a dozen scholars who cooperated in this endeavor published a 566-page book that not only included essays on their separate findings but also provided appendices with hundreds of tables of local and cumulative data.[3] A rush of other surveys followed: of young marrieds, of middle-aged women, of the elderly, and so forth. By 1986, however, this boomlet in survey research was on the wane, and the number of new survey findings that were openly published declined precipitously thereafter.

Not all of this research was methodologically sound in sampling techniques, nor did commonsense always prevail in the composition of questionnaire questions. Some of the researchers, without training and new to this mode of social science research, were obviously learning on the job. Perhaps a third of the survey reports from those years are of little use on account of such problems. But the other two-thirds, those that appear to have been reasonably sound methodologically, are invaluable in promoting our understanding of social change in urban China. Cumulatively, they enable us to see the broader outlines of urban family structures and the changes these were undergoing.

Unfortunately, this is not at all true with respect to rural surveys—which is why this book does not contain a parallel chapter on Chinese findings about peasant families. Rural surveys by Chinese sociologists are hard to come by,[4] and the comparatively few that do exist generally seem to have been conducted hurriedly, using abnormally small samples. Overwhelmingly, Chinese scholars have concentrated instead on the residents of big-city neighborhoods.

This chapter will draw upon some thirty-five of these urban surveys. Since almost all of them date from 1982 to 1986, much of my analysis will concentrate on the shape of urban Chinese families in the first half of the eighties. In a number of places my analysis will differ from those of the Chinese authors, and my citation of their statistical findings does not imply that they are responsible for the interpretations I have placed upon this data. The first sections of the chapter will draw heavily upon the statistics of the five-city survey, to set out the circumstances of families at the opening of the eighties. The latter sections will refer almost exclusively to other, later surveys.

[3] Wu chengshi jiating janjiu xiangmu zu (Research Project Group on the Families of Five Cities), Zhongguo chengshi jiating (Chinese urban families) (Jinan: Shandong renmin chubanshe, 1985). The scholars involved in this project subsequently published two edited conference volumes of papers that discussed the findings: Pan Yunkang, ed., Zhongguo chengshi hunyin yu jiating (Chinese urban marriages and families) (Jinan: Shandong renmin chubanshe, 1987); and Liu Ying and Bi Suzhen, eds., Zhongguo hunyin jiating yanjiu (Research on Chinese marriages and families) (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe, 1987).

[4] The major exception is the native village of the grand old man of Chinese sociology, Fei Xiaotong. Fei has sent assistants into the field to survey this one village repeatedly.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Making a Choice: Nuclear and Stem Families

First the simple facts. As of the early 1980s, according to the five-cities survey, some two-thirds of all the households in China's major cities were nuclear in composition: that is, they consisted only of parents and their children. We often think of Chinese families as including not just a married couple and their children but also one or more grandparents—that is, stem families[5] —and the data showed that, while urban China was largely composed of nuclear families, stem families, too, were indeed commonplace, constituting a quarter of all households. The 1982-83 survey of eight neighborhoods in five of China's major cities revealed that nuclear and stem families combined accounted for more than 90 percent of all households (table 2.1).

What was the prevalent trend, though? Were increasing numbers of newlyweds setting up their own independent households rather than living with parents-in-law in stem families? Not if we go by the figures gathered by the five-cities survey. These show that prior to the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the numbers of urban newlyweds who formed independent households were already on the rise, and that this trend had continued into the 1950s, but leveled off and subsequently dipped sharply. As can be observed in table 2.2, approximately 57 percent of the urban newlyweds who married during the dozen years between 1954 and 1965 had established their own households, but the incidence of this practice had been cut almost in half, to 32 percent, within the next dozen years.

One plausible explanation for the earlier shift into independent households is that the first decade of Communist Party rule had witnessed a large wave of immigration of single young adults into China's cities from the

[5] In the early 1980s, Chinese scholars devised various translations for the term "stem family." The two most common translations were zhugan jiating and zhixi jiating . By the latter part of the 1980s the usage of zhugan jiating had prevailed.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

countryside. They had had no families in the cities to fall back on, and when they married had necessarily set up independent families. This inflow of migrants was cut off in 1958, and strict controls against new migrants were introduced thereafter. We may presume that for at least the half decade immediately after the inflow from the countryside was halted, large numbers of the young adults who had arrived before 1959 were continuing to marry, which would explain the persistence during 1958-65 of a relatively high level of independent households of newlyweds (see table 2.2). But from the mid-sixties onward, the vast bulk of the marriage-age young people were from established urban families and, accordingly, could move in with parents after marriage.

Notably, it is also evident in table 2.2 that among the couples who married in the half-decade following Mao's death (the years 1977-82), the proportion establishing independent families was substantially lower than in the prior decade of 1966-76 and scarcely higher than for newlyweds in the years before 1937.[6] What accounts for the overwhelming preponderance of stem families among this younger generation of newlyweds? It should be remembered that a large portion of China's urban young people had been shipped off to the countryside to settle as peasants in 1968, when the Red Guards were crushed and the Cultural Revolution violence ended. They were joined in the countryside during the 1970s by a large proportion of the new urban secondary-school graduates, under a government policy of having the villages absorb the great bulk of the urban young people who were surplus to the needs of the urban labor force.[7] By the late 1970s, fully eighteen million urban youths had been forced into the countryside. Very few of them married during this decade of enforced rustication, in the belief that married couples would be less likely to receive permission to return to the cities. The wait was rewarded, for between 1975 and 1979 one province after another abandoned the hated to-the-countryside movement and ordered

[6] Most of the other neighborhood surveys of the early 1980s support the evidence of the five-cities survey. One provides contrary evidence, though. A 1982 survey of an urban neighborhood of Chengdu, Sichuan, claims that in the parents' generation (396 households), 59% of young couples had lived in households separate from their parents; 33% lived with the husband's parents; and 8% lived with the wife's parents. In comparison, among the 333 young Chengdu couples of 1982, a considerably higher percentage, fully 74%, reportedly lived independently; 14% lived with the husband's family; and 11% lived with the wife's parents. See Li Dongshan, "Lun ju zhi" (On systems of accommodation), Shehui diaocha yu yanjiu (Social Investigations and Research), no. 5 (1985): 58. In short, the data for the parents' generation are very much in line with that of the five-cities survey; and the Chengdu data for the present generation are very much at odds with the five-cities data. It seems quite possible that the Chengdu investigators' data for the present generation records as "nuclear" those young couples who initially had resided with parents but who had already moved out of the parents' home.

[7] Jonathan Unger, "China's Troubled Down-to-the-Countryside Campaign," Contemporary China 3, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 79-92.

most of the youths back to the cities. During the succeeding years, covering the period 1977-82, a large number of this horde of returned young people were not able to secure any regular urban employment nor the wherewithal to obtain separate accommodations when, after so many years of delay, they finally married. Such couples crowded into parents' apartments (the bride's if adequate space was not available at the groom's)[8] until separate housing became available.

That a temporary lack of alternative accommodations was a fundamental reason for the high proportion of stem families among newlyweds is suggested by the fact that most young couples moved out of the parents' home after only several years. A 1985 survey of 419 such multigenerational households in the city of Tianjin nicely illustrates this: 65 percent of the younger couples who had initially participated in stem families had moved out within the first five years of their marriage; and a further 17 percent moved out in the sixth to the tenth year of marriage: that is, in all, more than 80 percent of such stem-family participants moved out to form independent households within the first ten years of marriage.[9] This phenomenon was true not only for the most recent generation of young couples; the same shift out of parental homes had been true, too, of older cohorts of couples.

The consequence was that a clear majority of middle-aged couples, as of the early 1980s, were living in independent nuclear families, not with parents-in-law. Table 2.3, based on a survey of a Beijing neighborhood in late 1982, shows this very much to be the case for wives aged thirty-three to forty-five.

Demographics alone would dictate that many of these middle-aged couples would by necessity live as nuclear households. In past decades, from the 1940s through the end of the 1950s, urban families very often were giving birth to three to five children; and with the near-abandonment of the joint-family tradition (see below), when these children grew up all but one of them necessarily had to leave the household, either immediately at the time of their wedding or when their next younger brother married. This goes far in explaining the phenomenon, seen above, whereby a high propor-

[8] The proportion of young couples moving into the groom's home as compared to the bride's home remained relatively stable from 1958 through 1982, though with a slightly rising bias in favor of living with the groom's parents, according to the data contained in table 2.2. In the period 1958-65 the ratio stood at 2.26:1; for the period 1966-76, 2.47:1; and for the period 1977-82, 2.58:1.

[9] Pan Yunkang and Lin Nan, "Zhongguo chengshi xiandai jiating moshi" (A model of contemporary Chinese urban families), Shehuixue yanjiu (Sociological Research), no. 3 (1987): 61. (The number of individual respondents was not given; the survey covered 989 households.) This Tianjin neighborhood survey found that when first married, 52% of the newlyweds in the sample lived with the husband's parents; only 4% lived with the wife's parents; 42% lived in an independent household; and 2% other (p. 60).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tion of young couples shifted out of the parental home within the first five years of marriage. The longer-term stem families usually have comprised the elder couple, the youngest son, and his wife and children.

The shift of young married couples into nuclear households may have gone beyond this, however. Chinese statistics suggest that in many cases even the last remaining child moved out, leaving the older couple on their own. Table 2.3, for example, shows that fully 77 percent of the surveyed Beijing women who in 1982 were in the age group thirty-three to forty-five lived in their own nuclear family—and that only 21 percent of the women in that age group lived in a stem or joint family. This latter statistic must have included a substantial number of women in their forties who were living in a stem family with their own newly married children, rather than living with their old parents-in-law. In short, the great bulk of the younger middle-aged women were living entirely apart from their elders.