INTRODUCTION: THE TALES IN THEIR CONTEXTS

Chapter One

Madhu Nath and His Performance

First Encounters

Try as I might, I cannot remember the first time I met Madhu Nath, the senior author of this volume. That I came to record his performance of Gopi Chand was initiated neither by me nor by him but by his relatives Nathu and Ugma Nathji—some of my closest associates during my residence in the Rajasthani village of Ghatiyali. Madhu, although born in Ghatiyali, settled many years ago in another nearby village, Sadara. Therefore, although he celebrated life cycle rituals among his kinfolk in Ghatiyali, and periodically performed there, he spent most of his time in Sadara. This accounts for my being unaware of him as a special person after over a year's residence in Ghatiyali and a deep involvement with several households of his relatives there.

Because of manifold links between pilgrimage and death, I had been systematically recording "hymns" (bhajans ) sung on the eve of funeral feasts by the Nath caste and non-Nath participants in the sect which they led. I had grown increasingly interested in the Naths' peculiar approach to death and the liberation of the soul (Gold 1988, 99–123). When Madhu was directly introduced to me as a singer, in January 1981, I was reminded that my bhajan recordings of April 1980 were made at hymn sessions, first for his son and then for his wife. I had actually attended both their funeral feasts. This latter significant connection was phrased as, "You ate his son's and his wife's nukti" —nukti being the little sugary fried balls that are one of the most characteristic foods of ceremonial village feasts (called nukta ). During these particular feasts I must have seen Madhu, as I have seen so many

other hosts at dozens of similar events, harried and anxious to keep all his guests satisfied, with no time for casual conversations. Madhu always wore his pale red-orange turban tied low, almost hiding and also supporting the heavy yogis' earrings that might otherwise have caught my attention.

My memorable and formal introduction to Madhu Nath took place over half a year later when, after six weeks in Delhi and Banaras, where I had been recuperating from hepatitis, I returned to Ghatiyali accompanied by Daniel Gold (then friend and colleague but not yet husband). Daniel, as a historian of religions researching the sant tradition in North India, had become interested in Ghatiyali's Naths when I showed him the transcribed texts of their hymns—many of which had the signature (chhap ) of the poet-saint Kabir, and some of which employed the coded imagery common to Sant poetry (Gold 1987; Hess and Singh 1983).

Daniel expressed his desire to talk with persons learned in Nath traditions, and my research assistant Nathu Nath introduced to him several members of his family and sect. The last person he brought to us was Madhu, and that evening—Daniel's last in the village—Madhu performed, and I duly recorded, Gopi Chand's janmpatri or birth story. I was immediately intrigued and delighted: here was a living bard singing a story that was obviously about the same character as Temple's Punjabi version, yet evidently startlingly different in certain prominent details. I recalled from Temple nothing about Gopi Chand's being won as a boon by his mother's ascetic prowess or borrowed from the yogi Jalindar. Yet these were the dominant elements that framed the plot of Madhu's "Birth Story."[1]

Until that first evening with Madhu Nath I had largely confined my recordings of folklore to much briefer performances: women's worship tales and songs, and men's hymns. Yet now I felt compelled to obtain the whole story of Gopi Chand, despite its lack of direct relevance to my pilgrimage research, and the perceptible ticking away of my finite time in India. My recording sessions were not continuous; Madhu made a trip to Sadara to look after his fields when he had finished the "Birth Story" (in one night) and the "Journey to Bengal" (in two). Persuaded to return so that I could have the complete tale of Gopi Chand, he next gave me "Gopi Chand Begs from Queen

[1] In chapter 3 I discuss how Gopi Chand varies from region to region.

Patam De," which belongs chronologically between the segments on birth and Bengal, and "Instruction From Gorakh Nath"—the conclusion. Seven years later I returned to Rajasthan with the express purpose of recording from Madhu the tale of Gopi Chand's maternal uncle, Bharthari of Ujjain. Despite the gap in time, the circumstances of the recording sessions in 1988 were not very different from those of 1981, except that the loudest crying baby on the second set of tapes belonged not to my host's household or neighbors but to me.

In January 1981 when I came to know Madhu Nath he did not strike me as a man undone by loss and mourning, although in 1980 he had buried first one of his two sons and then his wife. The son had suffered a long and debilitating illness through which he was intensively and devotedly nursed by his mother. She had, I was told, kept herself alive only to serve her child and had not long outlived him. Accompanying this double personal loss, Madhu had incurred the great economic stress of sponsoring two funeral feasts. I saw others driven to or beyond the brink of nervous collapse by just such accumulated pressures.

Yet Madhu Nath was calm, confident of his power with words, always entertaining, and sometimes very humorous. Retrospectively, I wonder if he did not derive some of his solidity, following this very difficult period of his life, from the teachings of the stories that he told so well again and again—stories with the bittersweet message that human life is "a carnival of parting." Another factor in his equilibrium could have been the Nath cult's promise of release from the pain of endless rounds of death and birth, and thus certainty of his wife's and son's liberation.

It is also true, however, that I approached Madhu Nath as a source of art and knowledge rather than as a man who had recently suffered much grief. We never spoke of his family; indeed, we hardly exchanged any personal courtesies of the kind that constitute much of normal village social intercourse. Madhu teased me sometimes—making jokes at my expense during the spoken parts of his performance—but outside the performance itself we did not talk very much in 1981. In short, although he was a wonderfully expansive storyteller, Madhu seemed to me a reserved and veiled person.

I did not attempt to obtain even a sketchy life history from Madhu Nath until my 1988 visit. My experience then confirmed in part the intuition that our lack of personal relationship could be attributed to

him as much as to me. My attempt at a life history interview rapidly degenerated, or evolved, into an illuminating session of "knowledge talk," rich in myth but skimpy on biography. What follow here are the bare outlines of Madhu's career as I gleaned them from that leisurely and rambling conversation, supplemented by a few inquiries made by mail through my research assistant Bhoju.

Madhu, a member of the Natisar lineage of Naths, was born in Ghatiyali, but in his childhood he was sent to live with an elder brother already residing in nearby Sadara. His brother was pujari or "worship priest" in Sadara's Shiva temple.[2] The thakur or local ruler of Sadara—and this would have been in the thirties when thakurs still ruled—came into possession of a pair of yogis' earrings and took a notion to put them on somebody. Madhu, and other Naths who were listening to our conversation, concurred on the consistent if seemingly superficial interpretation that the Sadara thakur was endowed with great sauk (a term translatable as "passionate interest") in such works. Perhaps more salient, they also suggested that enduring "fruits" (phal ) accrue to the one who performs such a meritorious act. And they offered as evidence the information that, even today, when independent India's concerted attempts at land reform have greatly reduced the circumstances of Rajasthan's former gentry, there is "nothing lacking" in the Sadara thakur' s household.

Whether we see Madhu as beneficiary or victim of the thakur' s sauk, the rationale for his becoming the recipient of these yogis' earrings appears to have been more economic and social than spiritual. The landlord deeded some fertile farmland to Madhu's family in exchange for cooperation on the family's part. As for Madhu himself, he was young and clearly his head was turned by the attention he received in the ceremony, and the pomp with which it was conducted. Fifty years later he described to me with pleasure the feasts, the processions, and the "English band" that were for him the most impressive and memorable aspects of this function. He stated that, although two "Nath babajis"[3] were called to be ritual officiants, he had no personal

[2] Through much of rural Rajasthan it is Naths, not Brahmans, who serve as priests of Shiva temples. The Nath cult and their lore are strongly, but not universally, identified with Shaivism; see chapter 2.

[3] Like maharaj or "great king," babaji, literally "respected father," is a common epithet and term of address for Nath and other renouncers. It has connotations of intimacy that other terms for "father" lack and may also be used affectionately for children.

guru. For Madhu, his own ear-cutting seems to have been completely divorced from the kind of spiritual initiation with which it is consistently associated, not only in the tales he himself delivers but in other published accounts.

Nevertheless, this experience and its visible physical aftermath—the rings themselves—surely set Madhu apart from the other young men of his village world. Although Madhu did not state this in so many words, what he did make clear was that after the ritual he found himself restless and unsatisfied with the life of an ordinary farmer's boy. His brother sent him out to graze the goats, but he felt this was "mindless work" (bina buddhi ka kam ) and quarreled with him. Evidently the economic fruits of Madhu's ear-splitting were being reaped not by Madhu but by the senior male member of his household. The brother declined to support a non-goatherding Madhu; Madhu declined to herd goats. At this juncture, Madhu decided to set off on his own. As he put it, "There was no one to control me so I had a sarangi [the instrument he plays to accompany his performances] made by Ram Chandra Carpenter." Madhu continued, "I rubbed it,"—meaning he did not know how to play properly—"and went to all the big feasts."

Madhu then listed a number of events (weddings, holiday entertainments, and so forth) that he had attended in several villages where Naths performed their tales, both for their own caste society and at the request of other celebrating groups. In the course of these meanderings Madhu hooked up with his mother's brother's son, Sukha Nath, who was already an accomplished performer. Madhu began by informally accompanying and making himself useful to Sukha. Eventually they agreed on an apprenticeship. Madhu said, "I'll go with you," and Sukha said, "Come if you want to learn." Madhu then sought permission from his grandmother in Ghatiyali, telling her—as he recalled it for me—"I'11 wash his clothes, I'll serve him, I'll live with him."

Madhu appeared to remember the years of his discipleship fondly, and no doubt selectively. He described eating two meals a day of festive treats for weeks at a stretch when he and his cousin were commissioned to perform for relatively wealthy patrons. It was particularly at such special events—the only occasions when the stories are narrated from beginning to end rather than in fragments as is the usual custom—that he mastered Sukha Nath's repertoire. This comprised the three epics Madhu himself performs: Gopi Chand, Bharthari, and the

marriage of Shiva. Madhu also knows countless hymns and several shorter tales.[4]

At a time that Madhu estimated to be about five years after he acquired the yogis' earrings, he was married, eventually becoming the father of two sons. After his brother's death, the Sadara property came fully into Madhu's possession, as did the service at the Sadara Shiva temple. He seems then to have settled into a life divided between agricultural and priestly tasks in Sadara and exercise of his bardic art in a group of nine surrounding villages, including Ghatiyali.

Madhu Nath's Performance

Members of the Nath caste in Madhu's area of Rajasthan inherit and divide the right to "make rounds" (pheri lagan!a) and to collect grain donations, just as they do any other ancestral property. When a father's right must be parceled out among several sons, they receive it as "turns." The Rajasthani word for these turns is ausaro, but English "number" is also commonly used to refer to them. Of course, some who inherit the right to perform have no talent to go with it. For example, Madhu explained to us, when his cousin Gokul Nath's "number" comes, Gokul seeks Madhu's assistance and they make singing rounds together, for which Madhu receives a part of Gokul's donations.

Besides what a performer collects while making rounds, designated Nath household heads also receive a regular biannual share of the harvest—called dharo —in the villages with which they are affiliated. In 1990 this share, for Ghatiyali's Natisar Naths, amounted to two and one-half kilos of grain at both the spring and fall harvests from every landed household in eight villages. In Ghatiyali itself, where the Natisar Naths are landed residents, they do not collect dharo, although they receive donations on their performance rounds. Madhu explained that dharo was not allotted to Naths for singing, but rather for the "work" of removing locusts—a magical power that the caste claims. Nowadays, he concluded, they sing because there are no

[4] I recorded Madhu's performance of the "Wedding Song of Lord Shiva" in 1988; the tapes are archived with the American Institute of Indian Studies, Centre for Ethnomusicology, in New Delhi.

locusts, thanks to a governmental extermination program (clearly a mixed blessing for Naths).

It seems that performing Gopi Chand-Bharthari may have recently been transformed into an inherited right, in order to preserve the patron-client relationship founded on locust removal.[5] By asking the kind of imaginative "what if" question that I always felt was too leading but from which we often learned the most, my assistant Bhoju elicited further support for this interpretation. What, he asked Madhu, would happen were he to practice his art in someone else's territory? Would there be trouble? Madhu responded with a firm denial: "We jogi s make rounds; we could go as far as Udaipur. We are jogi s so no one could stop us."

Twice a year, when it is his turn, Madhu Nath makes rounds in his nine villages. In any village on any given night, rather than remaining in a single location, he moves from house to house in the better-off neighborhoods, or temple to temple among the lower castes. At each site he sings and tells a short fragment of one of his lengthy tales—choosing what to sing according to the request of his patrons or his own whim.

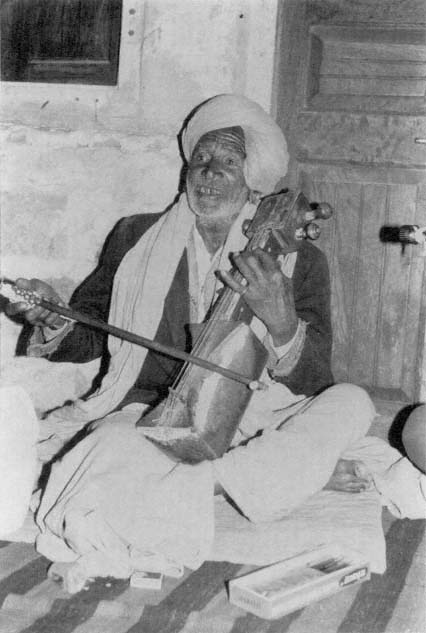

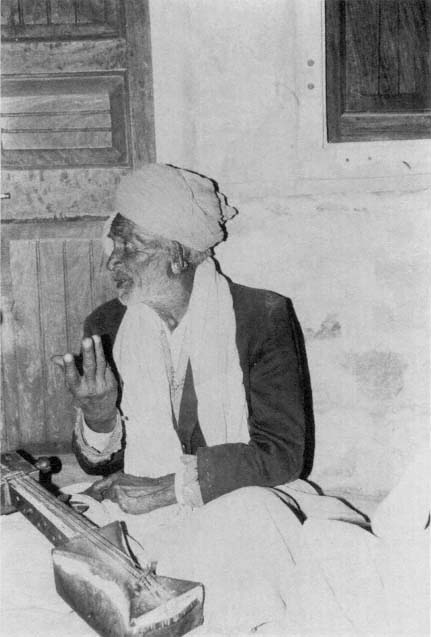

Madhu is highly respected as a singer and storyteller of rich knowledge and skill who can move an audience to tears. His performance alternates regularly between segments of sung lines, accompanied by music which he plays himself on the sarangi —a simple stringed instrument played with a bow—and a prose "explanation" (arthav ). In this explanation he retells everything he has just sung, using more colorful, prosaic, and often vulgar language than he does in the singing. The spoken parts are performances or communicative events as clearly marked as the musical portions are. Whereas Madhu's ordinary style of speaking is normally low-key and can seem almost muted, his arthav is always enunciated distinctly and projected vigorously. The arthav, moreover, often incorporates the same stock phrases and poetic conceits that occur in the singing.

During both my 1981 and 1988 recording sessions, Madhu was

[5] According to Ghatiyalians, Naths were first invited to settle in the villages round Ajmer because of their magic spells. One of the episodes that definitively localizes Madhu's version of Gopi Chand contains a "charter" for the Nath power over locusts (see chapter 2 and GC 4).

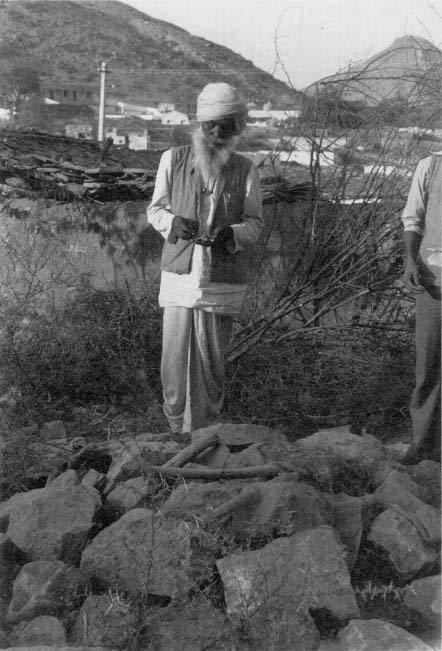

1. Madhu Nath plays the sarangi and sings Bharthari's tale.

2. Madhu Nath gives an explanation of Bharthari's tale.

3. Madhu Nath and his son, Shivji, sing Bharthari's tale.

usually accompanied by his surviving son, Shivji, who sang along in a much fainter voice that was prone to fade away when, presumably, he did not remember the words. However, there were some occasions—notably more in 1988—when Shivji carried the words and Madhu faltered. Shivji played no instrument and did not participate at all in the arthav .

As I worked on translating Madhu's words, I replayed the tapes of his original performance. Inspired by Susan Wadley's exemplary demonstrations and discussions of the ways an epic bard in rural Uttar Pradesh self-consciously employs various tunes and styles (Wadley 1989, 1991), I began to try, in spite of my musical illiteracy, to pay attention to Madhu's use of "tune."[6] My initial impression of Madhu's music had been that it was monotonous; what kept you awake was the story. This is partially but not wholly true. Compared to the bard Wadley describes, Madhu Nath's range of musical variations seems limited; yet he does deliberately modulate emotional highlights of his story with shifts in melody and rhythm.

[6] Other studies that helped me to appreciate the interpenetration of musical artistry and cultural meanings are Basso 1985; Feld 1982; Seeger 1987.

Madhu uses two patterned tunes, which he calls rags , in Gopi Chand and two different ones in Bharthari, where he also recycles both Gopi Chand rags . All four melodic patterns are flexible in that although each engenders verbal verse patterns, the melodic patterns frequently and readily change to accommodate narrative needs. In what I call Gopi Chand rag 1, for example, each verse normally has three similar lines and one longer concluding one. Long narrative sequences, however, may repeat the short lines many more times than three before concluding. And for an emotional or dramatic climax the long concluding line may repeat once or even twice. The main rag identified with Bharthari begins with a prolonged Rajajiiiiii —"Honored King ... "—that seems to signal the plaintive voice of the king's abandoned wife. Part 1 of Bharthari is performed in a style different from any of the others, its melody less interesting and less emotional, that seems to me in keeping with its orientation to external action.

Ethnomusicologist David Roche (personal communication 1991) describes Madhu Nath's musical style as one influenced by caste traditions but infused by new influences. He says that the melodic phrases are "pan-North Indian"—not particularly Rajasthani. Madhu Nath's musical style is, according to Roche, a "contemporary bhajan style" reflecting the influence of regional religious dramas and mythological films. Roche finds Madhu's music historically influenced by the harmonium—an instrument introduced to India by Christian missionaries from the West in the late nineteenth century and soon passionately adapted to Hindu devotional singing. This influence is apparent to Roche in Madhu's "intonation and diatonicism, with emphasis on major and mixolydian mode tetrachords." Although Madhu uses no harmonium—nor do other Rajasthani Nath epic performers I have met—many of Madhu's relatives and caste-fellows in and around Ghatiyali participate in bhajan -singing groups regularly accompanied by harmoniums.

That Madhu employs the term rag to refer to the melodies he plays probably represents a folk usage rather than a significant link to Indian classical traditions. Once Madhu told Bhoju that he "always" sang in asavari rag , a named rag within the classical system. Because I was hearing four distinctive melodies, I hoped that Madhu had a name for each of them. I made clips from the tapes and sent this "sampler" back to the village with Bhoju. Bhoju wrote, "I took that

rag tape and listened to it with Madhu Nath, Shivji Nath, Ugma Nath, and Nathu all together, but no one could tell a particular name of the rags ." Rather, the assembled Naths used labels such as "the melody of rounds" (pheri ko rag ) or "Gopi Chand's melody" (Gopi Chand ko rag ). This seems to confirm Roche's suggestion that Madhu's music is not to be labeled among any fixed traditional systems but rather is part of a creative synthesis continually emerging in North Indian folk music.

It is widely acknowledged that any folk performance situation is a dynamic, interactive event,[7] and this statement certainly describes Rajasthani performances in general and Madhu Nath's in particular. I shall examine the several ways in which Madhu and his audience sustain this dynamic during individual performances. Before doing so, however, I wish to suggest some broader contextual factors that contribute to these occasions but are more diffuse and difficult to pinpoint.

Rajasthan's regional culture includes a rich and diverse body of living oral performance traditions. These enliven a daily existence that may be both monotonous and laborious. On the one hand, an urban Westerner like myself, landed in a place like Ghatiyali, is overwhelmed by the abundance of festivals, rituals, all-night singing sessions, storytelling, and other lesser and greater artistic and communicative events; during my first months in the village I often felt that I was feasting at a perpetual banquet of live music and theater, with no tickets required. On the other hand, in 1979 81 the villagers had no TVs and few radios or tape recorders, while the nearest cinema was a costly three-hour journey distant. Any performance event punctuated the humdrum grind of labor-intensive agriculture.

Nath performance traditions must be viewed within this cultural frame: they exist as one genre in a wealth of related genres; they also exist as valued entertainment in a society not yet made blasé by multiple media. Rural Rajasthani society, moreover, venerates religious experts and accords recognition to many from different ranks and with varying sectarian affiliations. Like most of the region's popular folk traditions, Madhu Nath's performances meshed with his audience's twin passions for entertainment and enlightenment. Although Madhu himself protests that his stories are not siska , or

[7] Bascom 1977; Bauman 1977, 1986; Seitel 1980; Tedlock 1983.

"instruction," audience members claim that they are. The Nath tales are not unique, nor are they the most highly prized of performances available to Rajasthani villagers. Yet they have a welcome and secure place in the annual round.

Madhu Nath at times refers to the entire tale of Gopi Chand or Bharthari as a byavala , a term that one dictionary defines as a god's wedding song (Platts 1974). Before returning to Rajasthan in 1987 I speculated that both tales might be so described because they were somehow anti-wedding songs. However, as I was to learn, a third long narrative in Madhu Nath's repertoire is "The Wedding Song of Lord Shiva" (Sivji ka byavala ); it seems clear that he has named the others accordingly. Most villagers do not use the term byavala to refer to Madhu Nath's performances and often simply call them varta . This label reveals their kinship with other epic tales of Rajasthani herogods whose singing and recitation may be called varta , too.[3]

According to the sensible, informed, and flexible definitions proffered in the recent important volume Oral Epics in India , the Bharthari-Gopi Chand tales fall beyond doubt in the epic genre. Epics in general are characterized as narrative, long, heroic, and sung (Blackburn and Flueckiger 1989, 2–4; Wadley 1989, 76). In the South Asian context, Blackburn and Flueckiger suggest, the quality "heroic" may be understood in three distinct ways. An epic may exhibit martial, sacrificial, or romantic heroism. Both the martial and sacrificial types "turn on themes of revenge, regaining lost land, or restoring lost rights," and stress "group solidarity"—all of which would apply to other Rajasthani epic-length tales. Romantic epics, by contrast, "celebrate individual actions that threaten that solidarity" (1989, 4–5). Clearly the tales of Bharthari and Gopi Chand belong in the "romantic" category if they belong anywhere. Yet our heroes are hardly traditional, undaunted lovers.

It might seem that the tales celebrate individual action that threatens group solidarity, but as I will discuss in more detail in the afterword, yogis gain nothing from a damaged social order. Rather, they maneuver for an intact social order that supports yogis. What then makes these tales romantic? Unless we consider them as stories of the union between guru and disciple, Bharthari and Gopi Chand are romances of parting. The theme of love in separation is a pervasive

[8] See Pande 1963 for the scope of varta .

one in Indian literature. Longing for an absent lover—whether soldier, ascetic, or clerk in the city—has inspired much poetry on mortal love (Kolff 1990; Vaudeville 1986; Wadley 1983), as well as an entire genre of devotional expression. But most literature inspired by love in separation suggests at least a movement toward, or the possibility of, future reunion. Bharthari and Gopi Chand, by contrast, continuously and irrevocably move farther and farther from their loved ones. Madhu Nath's performances of Bharthari and Gopi Chand can be styled romantic epics celebrating separation rather than union, if we keep clearly in mind that the separation they establish is eternal.[9]

One factor distinguishing these stories from many others heard by villagers is that, although sung and told in the local dialect, they are not indigenous to Rajasthan—a matter I will deal with more extensively in chapter 3, where I attempt to trace their origins. Gopi Chand and Bharthari have been incorporated into Rajasthani traditions, and Rajasthani traditions have been incorporated into them. But these Nath tales are not self-defining epics that contribute to the identity of a regional culture—the kind of tales that people call "ours" (Blackburn et al., eds. 1989; Flueckiger 1989). Indeed, for Rajasthani farmers, Gopi Chand and Bharthari are stories of the exotic, in two senses. First, they are about other lands; second, they are about world-renouncers.

That Gopi Chand and Bharthari were understood in some ways as alien was brought home to me very strongly in 1988 when I asked some village men if they would want to be like Bharthari or Gopi Chand, and some village women if they would like their husbands or sons to emulate those figures. An almost universal answer from both sexes was "No, I wouldn't have the courage." Although some renouncers encountered and interviewed in temples spontaneously referred to Gopi Chand or Bharthari as exemplary in their capacity for tyag , or "relinquishment," no ordinary persons held them up as role models.[10]

There is a real difference between my "induced"[11] performances

[9] The only tale considered by the editors and authors of Oral Epics in India that belongs to Nath lore is that of Guga. Blackburn categorizes it as a romantic epic with a supraregional spread and places it about midway on the ritual-to-entertainment continuum (1989, 17–20). The same description applies more or less to Bharthari and Gopi Chand.

[10] See, however, Kothari 1989 on the unsuitability of many folk epic heroes and heroines as role models.

[11] See Goldstein 1967 for the "induced natural context" in folklore fieldwork.

of both tales and the performances that most villagers hear twice a year when Madhu makes his rounds. They hear fragments, and often their favorite fragments are repeated from year to year. People's understanding may be limited by lack of familiarity with the whole story. Most of those whom Bhoju or I questioned were easily able to retell the most popular episodes from both tales.[12] Few villagers, however, had heard either tale from beginning to end from Madhu, although a number had seen theatrical performances at religious fairs. Several members of leatherworker castes (regar and chamar ) claimed to know very little about the stories; one complained that when Madhu came to his neighborhood he only spoke "a few lines" and left again.

My own experience of immediate audience reactions to the performances of Gopi Chand and Bharthari is limited to the context of the event which I sponsored, for I never observed Madhu "making rounds" (although he was recorded doing so by my colleague Joseph Miller). In the setting of my performance the responses were quite limited. After three or four hours of listening, until well past midnight, we would usually hurry home when Madhu ended his singing. Indeed, he often closed a night's session by saying to me, "Now go to bed."

Madhu Nath's Stories in Synopsis

It has been said of at least one Indian epic—and may be true of most—that no one ever hears it for the first time. Western readers, who have not participated from childhood in the culture that produces these stories, may need a "pony." Throughout these introductory chapters I often talk about events and characters in Madhu Nath's versions of Bharthari and Gopi Chand. Therefore, as points of reference for those citations, I offer skeletal plot summaries in advance, segmented and ordered according to Madhu Nath's performance as it is translated in this book (see also figs. 4 and 5).

Bharthari's "Birth Story" (part 1) describes how his father was cursed by his own father to enter a donkey's womb. The donkey suc-

[12] Episodes for Bharthari included Pingala's sati and Bharthari's encounter with Gorakh Nath at the funeral pyre (both in part 2), as well as Bharthari's begging and Pingala's lament (part 3). For Gopi Chand most commonly cited were his mother's instructions (part 1), his begging from Patam De Rani (part 2), his troubles with the lady magicians (part 3), and his farewell to his sister (part 3).

4. Family relationships in the tales of King Gopi Chand and King Bharthari.

ceeds after lengthy efforts in marrying a princess and founding a city, Dhara Nagar, where his three offspring—Bharthari, Vikramaditya, and Manavati—are born.

In part 2, Bharthari is king of Dhara Nagar and married to Queen Pingala. He rides out hunting and kills a stag, whose seven hundred fifty does, widowed, curse King Bharthari that his women will weep in the Color Palace as they do in the jungle. They then hurl themselves on the dead buck's antlers and thus commit sati .[13] Bharthari wonders if his own wife is equally devoted. He sends her a handkerchief soaked in deer's blood with the message that he is dead. Pingala knows this is a test but decides to die anyway. Bharthari has other adventures in the forest but eventually returns home to find Pingala a heap of ashes. He goes mad with remorse, until the yogi guru Gorakh Nath arrives, demonstrates the illusory nature of life and death, and finally restores Pingala to the king.

Part 3 finds Bharthari sleepless and unsatisfied. Convinced that nothing in the fluctuating world matters, he abandons his wife and renounces his throne to seek initiation from Gorakh, who sends him back to the palace to beg alms from Pingala and call her "Mother."

[13] Although the common image of a sati is of a woman who chooses to be cremated alive on her husband's funeral pyre, any style of death may be called sati if through it a female follows a beloved male.

5. Nath guru-disciple lineages in the tales of King Gopi Chand and King Bharthari.

She reproaches him but gives the alms. This difficult task accomplished, Bharthari returns to Gorakh Nath's campfire.

Gopi Chand's "Birth Story" (part 1) opens with Manavati (Bharthari's sister, married into "Gaur Bengal") instructing her only son, Gopi Chand: "Be a yogi." She then reveals in a long flashback how she obtained the boon of a son from Lord Shiva although no son was written in her fate. In order not to break his promise, Shiva allows her to borrow one of the yogi Jalindar Nath's disciples, and she chooses Gopi Chand. The loan has a limit: after twelve years of ruling the kingdom, Gopi Chand must become a yogi or die. As a wandering ascetic, however, he will gain immortality. Gopi Chand, possessing eleven hundred wives and sixteen hundred slave girls, is not pleased with his mother's bargain.

In part 2 Gopi Chand tries to get rid of the guru by putting him down a well. But it is Gopi Chand who dies, and only the power of yogis saves him. Restored to his palace, he follows his mother's instructions and has his ears cut by Jalindar. The guru then sends him to beg alms from Queen Patam De, his chief wife, and to call her "Mother." Although Patam De finally fills his alms bowl, when her mother-in-law literally twists her arm, Jalindar has to rescue Gopi Chand from the palace, where he is surrounded by weeping women.

Against his mother's and guru's advice, Gopi Chand heads for Dhaka in Bengal to say goodbye to his sister, Champa De Rani (part 3). On the way he is harassed by seven lady magicians who transform him into various animals and abuse him. Jalindar sends a party of yogis to rescue him but it fails. The guru himself then accompanies

a second group, which succeeds. Gopi Chand proceeds to his sister's; she dies of grief in his arms but is brought back to life by Jalindar. Gopi Chand spends some happy time with her and then leaves alone.

In part 4 a dispute arises between,Jalindar's disciple Kanni Pavji and Gorakh Nath. Kanni Pavji tells Gorakh that his guru, Machhindar Nath, is enjoying women and lathering sons in Bengal; Gorakh tells Kanni Pavji that his guru,Jalindar, is at the bottom of a well. Gorakh goes to Bengal and rescues Machhindar, destroying his wives and sons along the way. Gorakh then brings seven species of locusts out of the well, tricks, Jalindar into giving immortality to Gopi Chand and Bharthari, and convinces him to emerge. All the great yogis then feast one another. At Gorakh Nath's "wish-feast" Kanni Pavji's disciples wish for improper foods and are degraded.

Madhu Nath's Performances for Me

It is winter. We assemble in that part of the Rajasthani village house called a pol —a covered entranceway wide enough to form a room that lies between street and courtyard, often with raised platforms on either side for storage or sitting. This area is a shady breezeway in the summer and a shelter in the winter. By the time we gather there after the evening meal it is already dark and slightly chilly. Everyone, male and female, has wrapped a shawl or blanket over his or her usual daily attire. In the center of the pol is a small fire of dry sticks that burns low, even its frugal warmth a luxury in this wood-impoverished region.

In January 1981 I had already lived fifteen months in the village, but recording Madhu Nath was my first experience as performance patron. I received a quick education in how to fulfill this role with appropriate liberality. I must supply the singer and his son with a "bundle of biris"—biris being harsh, leaf-wrapped cigarettes smoked by almost all males who have not taken a vow of abstinence. I must treat performers and audience to tea each night, which involved purchasing tea leaves, sugar, and milk in advance—the last item not always easy to buy in the evening. In addition, a quarter- or half-kilo of gur , unrefined brown sugar, was indispensable. The singers required gur to soothe their throats (Madhu had an awful cough, which did not deter him from relishing the biris ). A generous patron should pass small lumps of gur round to all the listeners once or twice in the course of an evening.

At the beginning of our recording sessions my comprehension of the sung segments of Madhu's performance was very limited. How pleased I was to benefit from the custom of arthav or explanation, in which Madhu repeated everything he had sung and elaborated on much of it. During the arthav , members of the audience who have passively listened to the sung portions are more actively engaged by a vital performer. A formalized element of performer-audience interaction in Rajasthan is the part played by the hunkar . A hunkar , which can only be awkwardly glossed as someone who makes the sound hun —a kind of affirmative grunt—is a standard feature of any storytelling event, from women's worship stories to men's informal anecdotes.

At first I thought the hunkar 's function was to offer a perfunctory reassurance to the performer that at least one person was really listening. Given the distracting surroundings of many village performances—often including clamorous childern and simultaneous competing activities—such assurance may indeed be needed. However, after being pressed more than once into fulfilling this role myself (which my frequent misunderstandings at times made me bumble or fake quite awkwardly), I began to perceive that a good hunkar can elicit a tale-teller's enthusiasm whereas a poor one can discourage a full telling.

A hunkar 's responses can shape the performance content as well as its quality. This too I learned from personal experience. On relistening to my tapes it was evident to me that when I played hunkar to Madhu, if he was in a generous mood, his arthav was noticeably changed: he used more standard Hindi (versus Rajasthani) vocabulary; he explained cultural phenomena he thought I might not understand; he glossed terms he suspected I was failing to grasp. For example, to my uncertain grunt following the line "Gopi Chand ruled the kingdom," he added, "Gopi Chand ruled, like Indira Gandhi rules."

The opposite case, a situation far more comfortable if sometimes less educational for me, would be when someone who knew the story well acted as hunkar . That person might even supply key lines if Madhu seemed to be dallying before giving them. During climaxes other audience members chimed in, adding their bit to the hunkar 's own responses, which also became less perfunctory. Thus when King Bharthari surveys the seven hundred fifty magically created look-alike Queen Pingalas—a vision both awesome and slightly comical—a number of spontaneous commentators (audible on the tape but only selectively included by the scribe) added their exclamations to the

hunkar 's: "They looked just alike, all seven hundred and fifty!" Their faces were exactly the same!"

Madhu deliberately evoked audience participation by identifying persons in the story with persons in the audience.[14] One way he did this was by caste. For example, when Jalindar Nath's disciples arrive in Bengal they encounter a gardener. Since there was a man of the gardener caste in the audience, Madhu named the gardener in the story with his name. Besides naming story characters after audience members, Madhu sometimes named audience members after story characters. Thus throughout the Gopi Chand performances he gently teased a younger relative by calling him "Charpat Nath" after one of the powerful yogi figures. This stuck, so that when Bhoju or I met that young man outside the storytelling context, we would call him Charpat.

The entire performance of Gopi Chand took five recording sessions, each from three and one-quarter to four and one-half hours long; it filled the better part of eleven 90-minute cassettes—or over sixteen hours of tape. Each night's session was broken up by short intervals of batchit (conversation), during which the recorder was shut down, usually following the arthav and preceding a new sung section, but sometimes coming between singing and arthav . During one of the breaks strong sweet tea would be passed round and eagerly swallowed, its caffeine and warmth both welcome.

The first part, the "Birth Story," was recorded in its entirety on 24 January 1981. It took two sessions, on the nights of 26 and 27 January, to record the whole "Journey to Bengal" episode. This was followed by a twelve-day hiatus in our recording (during which much transcription and translation work went forward). Madhu then performed "Gopi Chand Begs from Queen Patam De" on the night of 9 February and "Instruction from Gorakh Nath" on 10 February.

When I returned to Ghatiyali at the end of 1987, after an interlude of almost eight years, it was in order to record Madhu Nath's version of the tale of Bharthari, and my arrival was no surprise. I had written well in advance to Nathu and Bhoju. There were several surprises in store for me, however—one so serendipitous that, looking back, it seems like a most improbable stroke of fate. The very aged mother of

[14] K. Narayan very delightfully describes the expert practice of this technique by a North Indian guru (Narayan 1989).

Nathu Nath, my former research assistant, had died. His caste had decided to hold a major funeral feast to which Naths from villages all over the area were invited. Because this feast coincided almost exactly with the time I had to spend in Ghatiyali, it was certain that Madhu would be there, and not in Sadara as I had feared. It also presented a remarkable opportunity for Daniel Gold and me to meet many knowledgeable Naths. Much of my understanding of that caste's identity, presented in chapter 2, is the result of our conversations with Nathu's guests.

Word circulated among those attending the funeral feast that a foreigner was interested in their verbal art, and their caste lore in general. Several groups of strangers knocked at my door, a number of whom announced their capability and willingness to perform Gopi Chand-Bharthari. Even Nathu, who seemed to be annoyed with Madhu for reasons that never became clear to me, strongly suggested that I should record someone else's version. But I held out for Madhu, feeling that the continuity of my translation project required the same bard and that all these other potential singers presented an almost frightening distraction.

It was out of the question to record in Nathu's house, as we had in 1981, because the rooms were virtually overflowing with guests and all seating and tea-making resources were seriously overtaxed. Instead, we spread a carpet on the newly plastered courtyard of the Rajput house that had been my home in 1979–81 and was my camp this trip. We thus had cloistered Rajput women in the audience, and I was able to compensate for an old injury done to my former landlady. She had been angry with me eight years ago for not inviting and escorting her to the Gopi Chand sessions. Now she was able to savor Bharthari in the comfort of her own home.

Again, it was winter and we wrapped ourselves in shawls, savored our tea breaks, and sucked on gur . Madhu's performance got off to a somewhat slow start; Bharthari's birth story has more repetition in it than any other segment of either text. But soon Madhu warmed to his themes. His rendition of the central part of Bharthari—containing the best-loved climax when the king madly circles Pingala's pyre—was perfectly delightful and aroused much audience appreciation. Besides myself, Daniel, and our two inattentive sons, our gathering always included my research assistant Bhoju; my landlady; her daughter-in-law, grandchildren, and nieces; and a variable number

of neighbors and friends, who wandered in by plan or chance. Nathu, immersed in the work of the funeral feast, was unable to attend.

Madhu completed Bharthari's tale in three recording sessions held on the nights of 28, 29, and 30 December 1987. This represents approximately eight hours of recording, filling five and one-half 90-minute tapes. On the whole, the performance atmosphere for Bharthari was very similar to that for Gopi Chand eight years before, with only a few perceptible differences. Madhu's cough seemed a little worse; Shivji's singing seemed a little better; Bhoju was the hunkar most of the time and played his part vigorously.

Translation in Practice and Theory

Toward the conclusion of part I of Madhu Nath's Gopi Chand, Manavati Mother has at last won the boon of a son. She goes to select from among the yogi Jalindar Nath's fourteen hundred visible disciples the one that pleases her the most; then Jalindar will loan him to her by having him reborn as her child. But until she spots beautiful Gopi Chand, the queen is far from delighted with her prospects as she scans the meditating yogis. Her words—as Madhu Nath narrated them and I recorded them in 1981—were as follows: "What will I do with such bearded fellows? What will I do with such twisted limbs, or ones like this who don't even understand speech (boli hi na hamjai )? What will I do with them?"

When Madhu Nath thus elaborated the queen mother's expressions of distaste there was laughter among our small company—laughter that was dutifully noted in parentheses by Nathu Nath when he transcribed the recording. Why was there laughter? Because, as Madhu enunciated "those who don't even understand speech," he gestured toward me. True to his characterization of me as uncomprehending, although I laughed along with the rest, I did not catch this quick jest at my expense. I thought we were laughing at the images of yogis as unattractive, defective persons not likely to make it in the world. But Bhoju, my research assistant, explained Madhu's jibe to me, as kindly as possible, when we read the transcribed text together a week or so later and the scene was still fresh in his memory. Over the words "those who don't even understand speech" I penciled "like Ain-Bai," my village name (this third-person notation symptomatic I suppose of self-alienation common in fieldwork experience), and soon forgot about it.

Six years later, as I embarked on a Mellon postdoctoral fellowship that centered on the Gopi Chand tale, I rediscovered Madhu's little "joke" and paused to ponder this characterization of me—a confident, well-funded translator and published ethnographer—as someone who didn't even "understand speech." It brought to my mind a moment described in the preface to my book on pilgrimage: my first evening in the company of Bhoju Ram Gujar, the young village man who was later to become my closest assistant, pilgrimage brother, and eventually coauthor. During this night he had excited and tired us both by steadily imparting to me in lucid grammatical Hindi the mystical and multiple meanings of esoteric Rajasthani hymns as they were being performed during an intense all-night singing party celebrating the new benign identity of a restless ghost.

When it became apparent to this young man, around two or three in the morning, that I was exhausted and had ceased to absorb his explanations, he chided me by quoting a Rajasthani saying. "For you," he said, "all this is 'brown sugar for a deaf-mute' (gunge ka gur )." Steeped as I was in the rich village world, consuming its sweets but unable to hear its language clearly, where would I find the tongue to tell of it? In my published preface I exclaim, "What a perfect metaphor for the anthropological enterprise!" (Gold 1988, xiv). This metaphor, simultaneously evoking inexpressible delight and human disability, seems equally applicable to the efforts of translation—especially the translation of a multidimensional, interactive communicative event into a linear, soundless, printed story. In the remaining pages of this chapter I examine the phases of my translation efforts, returning in the end to some other metaphors—of hopelessness and possibility.

The first round of translation for Gopi Chand was certainly the most enjoyable. During February and March 1981 except for two short trips, each of a few days' duration, to wrap up loose ends in my pilgrimage research, and the usual distractions of festivals, rituals, and the interpersonal psychodramas that I had finally come to accept as part of village life, my time and attention were remarkably centered on the recordings and rapidly emerging written text of Gopi Chand.

I employed both Nathu Nath and Bhoju Gujar full time during this period. Ugma Nathji, nonliterate but more knowledgeable than Nathu in his caste's teachings, was also often on the scene. We worked in two neighboring rooms, each opening on the same courtyard but not adjoining the other, as was the architectural custom in the village. Nathu (with or without Ugma Nath) would sit in one room, listening

to tapes and transcribing Madhu's words with painstaking accuracy. In the other room Bhoju and I sat side by side at a small desk doing our "translation work" (anuvad ka kam )—as we explained it in most unsatisfactory fashion to the many skeptical questioners who wondered how we passed our days. This work involved reading through the pages Nathu had transcribed and stopping everywhere I had a problem with the Rajasthani. Bhoju would then endeavor to clarify my confusions with explanations and glosses in Hindi. I made notes in pencil directly on the transcription, in an ad hoc mixture of English and Hindi.

Occasionally, when confronted by something extremely puzzling, we would resort to the nine-volume Rajasthani Sabad Kos (Lalas 196–278; hereafter RSK ) with its ponderous definitions in Sanskritized Hindi. Far more often I just wrote the meanings of words as Bhoju dictated them to me. Sometimes he embellished his verbal descriptions with sketches, demonstrating, for example, the design of a kind of earring or the shape of a particular clay pot.

In midafternoon scribe and translators all took a long tea break together and often talked and joked in terms of the stories and the bard's language. If Nathu, whose caste identity was Nath or Yogi, had to go somewhere, Bhoju would recite the bard's favorite couplet: "A seated yogi's a stake in the ground but a yogi once up is a fistful of wind." Gossiping about the passion of an illicit lover when aroused by his woman, Nathu might say, "It was just as if a wick were lit to one hundred maunds of gunpowder"—parroting the bard's stock metaphor for Gopi Chand's emotional crises. Thus the text's special language merged as I learned it with everyday life.

I had not the slightest sense of what I would do with the results of all this effort. But I found the protracted routinized translation work to be very soothing. It filled my days and kept my mind from dwelling on all the things I would never be able to finish, or even begin, as time ran out. Inevitably but nonetheless abruptly, when we were but a few pages into part 4, I at last had to leave Ghatiyali. I did not spend any time with the text again until 1987—six years later. The summary of Gopi Chand's story, which I included in my dissertation (Gold 1984) and ensuing book (Gold 1988) as well as in the article that I coauthored with my husband (Gold and Gold 1984), was done from memory. As I discovered to my chagrin when I did return to the text, it contains a few errors, the result of my imperfect compre-

hension and memory lapses, combined with Madhu's occasional vagueness. For example, I stated in that summary that Jalindar Nath rescues Gopi Chand from Death's Messengers; actually it is Gorakh Nath who, after taunting Jalindar with the news that his given disciple is dead, frees Gopi Chand so dramatically.

The second round of translation work, still only for Gopi Chand, began in 1987 when, supported by a Mellon Foundation Fellowship at Cornell University, I sat daily at a computer with Nathu's transcription in my lap and typed directly onto the screen a rough and literal English version. I never lifted a dictionary during this stage but worked entirely from my own knowledge of the language and Bhoju's glosses that I had jotted down six years earlier. By late summer 1987 I had a 250-page double-spaced English typescript. The last 80 pages were by far the roughest since they covered the final segment that I had never read through with Bhoju. I think of this as the "reading-for-meaning" phase of my translation. At this point I felt I had a full understanding of the story and wrote several interpretive essays (Gold 1989, 1991).

Convinced, however, that nothing I said about Gopi Chand's story would be fully valid unless I knew Bharthari's as well, I made plans to return to Rajasthan over winter break 1987–88. During that hectic six-week trip I had nothing comparable to the earlier daily routine of eight or nine hours in which I used to sit peacefully reading with Bhoju. I did manage to go over and solve most of the problems encountered in part 4 of Gopi Chand. Although I set the transcription process in motion for Bharthari, I left the village with only twelve pages on paper. Nathu completed the rest after my departure; Bhoju made interlinear notes in red ink and forwarded it to me.

Later still (from June through September 1989) supported by an NEH translation grant, I entered yet another phase, during which I relistened to all the tapes. The tapes made me aware of nuances of meaning totally lost in transcription and helped me to relive interactive dimensions of the performance in which I had participated but which I had forgotten during my subsequent fixation on the story. As Madhu's wonderfully gruff and expressive voice, or his minor-key melodic sarangi riffs filled my ears, and I stared at fiat words on the grey shrunken screen, I despaired over the inadequacy of all translation.

While my ethnographic self retreated, stymied, I became obsessed

with definitions. During these months I compulsively read dictionaries, searching for every word I did not "know"—a category arbitrarily comprising every word for which I was relying solely on Bhoju's glosses—in a series of dictionaries (Rajasthani-Hindi, Hindi-Hindi, Hindi-English as required). I made alphabetical lists with cross-references. Words that I found in none of these references, or whose dictionary definitions did not coincide with Bhoju's, I listed, and every month letters filled with these queries flew back to India. Bhoju often consulted Madhu himself or Madhu's son, Shivji, before responding.

Toward the end of this unpleasant and laborious period, another translator and I were able to bring Bhoju to America. I had the uncanny experience of sitting in my Ithaca office, subzero temperatures outside, with a village voice in my ears. By then my involvement in these stories and the tradition that generated them extended beyond firsthand ethnographic experience; I had read numerous variants from other regions and times and was working out my interpretations. No longer did I passively take dictation from Bhoju; occasionally I found myself arguing with him.

When Gopi Chand's wife reproaches him for becoming a yogi, she says: "Grain-giver, I taste bitter to you, but you think that yogi's just swell. He shoved a loincloth up your ass and put these earrings on you. He pierced your ears and put these great big earrings in them." In the village in 1981 Bhoju told me that the word the queen used for "earring" meant "yogis' earring" because of course that's what she was referring to—the yogis' earrings her husband wore. But the word itself, muraka , refers to a small earring worn by ordinary men. It is not one of the several special words for yogis' earrings, most often called darsai or "divine visions." I thought the queen was being deliberately disrespectful by using this word, as she surely was about the loincloth up the ass—employing a crude term for anus. Bhoju, however, said she was just an ignorant woman who didn't know the right word for yogis' earring.

Later in the scene Gopi Chand calls on his guru for help and threatens that if the guru doesn't come he'll go back to taking care of his kingdom and get rid of his "earrings-and-stuff"—calling them murakyan vurakan —thus further exaggerating the queen's disparaging terminology. The echo-word formation readily implies "earrings and all the rest of this yogic paraphernalia." To me it seems to confirm

Gopi Chand's interpretation of the queen's language, adopted when he is momentarily swept over to her perspective (and I see him as constantly backsliding thus from a yogic to a householder's viewpoint). The bard is quite unlikely to have used the wrong word by accident as he himself wears these "divine visions" and is extremely conscious of their special power. Bhoju was still not convinced.

I relate this dispute because it reveals nicely how much of a translator's problem lodges not so much in words but in contexts. To translate muraka as yogis' earring—even though that is what it refers to—would be simply wrong. But to translate it as "earring" also leaves something out: the fact that it is the wrong word for the type of earring referred to. Any solution to such moments must transact a compromise between fluidity and semantics. As is no doubt too often the case, I resorted here to a footnote where I gave both sides of the argument.

Eventually I arrived at the most challenging and vexing task: to take the repetitive, awkwardly phrased, but reasonably accurate product of all this labor and transform it into something palatable, pleasurable, charming. After all, Madhu's performance was all those things. I no longer feel quite deaf and dumb, but what I have to offer is not exactly brown sugar. My first decision was to use the written word and the printed page traditionally. I respect and admire the groundbreaking efforts of Dennis Tedlock (1983) and Elizabeth Fine (1984) among others, who have tried to develop innovative ways of putting oral performances on paper. Yet I myself find it difficult to enjoy their productions aesthetically. Such devices as uneven type sizes, slanting lines, and coded symbols do provide a far better record of oral performance than plain linear print. But as access to an aesthetic experience, for me at least, they fail. My immediate reaction to uneven type and arcane symbols is an almost automatic blurring or skimming impulse rather than transformed awareness. Whether this is common or idiosyncratic I do not know. In any case, I have taken a different route.

Surrendering music and largely surrendering audience interaction, in a sense I gave up on sustaining an oral mode; readers will have to supply that from my descriptions and their own imaginations. What I tried to reproduce is the rough charm and spontaneous flow of Madhu's speech, without falsely embellishing it. The fourth round was literally countless rounds, for I could not say how many times I went over the English version, rearranging, rewording, and cutting.

Eventually I had to make substantial cuts, by which something is certainly lost, but much is gained for all but the most patient English readers.

I cut in three ways, or at three levels. On the grossest of these, I made the decision —after translating the entire performance — to omit the sung portions except for those that open and close each of the seven parts of the two epics. A few other maverick segments of sung text slipped in because they advance the plot significantly with no spoken explanation covering the same ground. Normally, however, the explanation gives all that was sung and more. The singing does not present beautiful poetry; it lacks rhyme and its meter is strongly subordinated to the sarangi rags . The pleasure in it, I have come to believe, both from discussions with Madhu's audience and from my own experience, is largely musical. But the pleasure of the arthav is intentionally verbal—and is therefore a pleasure much more easily translatable to the printed page.

The second level of cutting involved condensing most of a particular scene when it replicated almost exactly another that was fully translated. Such scenes are limited. The biggest reduction from the original involved the encounter between a begging yogi and a group of slave girls that occurs once in Bharthari and three times in Gopi Chand. Of these four instances, two were substantially condensed as noted within the text. Another highly repetitive moment is the contest between yogis and lady magicians; I gave Gopi Chand's initial encounter fully but condensed whenever possible, and so noted, the subsequent encounters between Charpat Nath, followed by Hada Nath, and their Bengali enemies.

The third level of cutting is the one that makes me as a folklorist most uneasy, but its execution may contribute most to making this text generally accessible. This is the excision of innumerable internal repetitions—repetitions that give the oral performer time to think, that give his audience time to take it all in, but that on the printed page become rapidly tedious. My aim was to retain enough of these to leave the English with a colloquial, oral "flavor," but to remove enough to keep the story moving at an acceptable pace.

Let me give an example, from the opening scene of Gopi Chand. The queen has just told her son to be a yogi, and he is questioning her knowledge of yoga. My translation in this book is as follows:

Then Gopi Chand said, "But mother, you live in purdah inside the palace, and yogis live in the jungle. They do tapas by their campfires in the jungle. But you live in the palace. So, how did you come to know any yogis?"

Madhu Nath's original speech translated word for word goes like this:

Then Gopi Chand said, "Oh, Manavati Mata, you live in purdah inside the palace and a yogi, yogis, they live in the jungle. They live in the jungle performing tapas by their campfires, and you stay in the palace, so how did you come to know yogis? How do you know them? Yogis live in the jungle, in the woods. And you live inside the palace, so how did you get to know them, you?"

I think this example speaks for itself, and it is perfectly typical.

Pottery Lessons

The act of translation is often enough metaphorically maligned, in images that include the translator as executioner, bigamist, and traitor.[15] Fortunately, more benign images also exist. Perhaps the most pleasing of these, especially to an anthropologist steeped in notions of empathy, is that of the translator as friend, sharer, intimate—evoked by Kelly, who cites Rosecommon's seventeenth-century essay. Kelly writes of a "sharing between friends" that is "not merely informational: friends add to the information they share, a joy in the act of recounting it and a vicarious sharing of each other's experience on terms special to the friendship" (Kelly 1979, 63).

If part of a positive vision of translation is intimacy, another part is craftsmanship. Yet it is just such praiseworthy traits as skill, technique, and knowledge that contribute to the translator's self-image problem. If translation is skill then it is something less than art, a secondary act. Among all the metaphors proposed for translation, one of the most elegant and subtle is that of Walter Benjamin, whose essay "The Task of the Translator" begins with the skilled but artless act of gluing together pot shards but moves rapidly beyond this mundane figure into luminous visions.

[15] For translator as killer see Nabokov cited in Zvelebil 1987, vi; the bigamy image is one among several in Johnson 1985, 143, whose subtle exegesis I do not touch here; traitor is of course from the Latin pun-proverb.

Fragments of a vessel which are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details, although they need not be like one another. In the same way, a translation, instead of resembling the meaning of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original's mode of signification, thus making both the original and the translation recognizable as fragments of a greater language, just as fragments are part of a vessel.

Later in the same paragraph Benjamin continues: "A real translation is transparent; it does not cover the original, does not block its light, but allows the pure language, as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully" (1969, 78–79).

Several metaphors are working on several levels here. On the one hand matching the pieces of a broken pot is like the reproduction of meaning in translation; and on the other the original and the translation are themselves both fragments, not wholes. Abandoning the pots with their shapes, Benjamin goes on to speak of covering and translucency. The translation does not cover the original but allows light to shine through—not from it, however, but upon it. There appears to be, in that light, a premise of a reality bigger than both translation and original. When I read Benjamin it reminded me of a broken pot in the Rajasthani bard Madhu Nath's own stories—a pot that can be neither glued together nor replicated.

This pot appears in King Bharthari's tale in the central episode of part 2. Here the yogi Gorakh Nath mourns for his broken clay jug, deliberately mocking King Bharthari's mourning for his cremated queen. The king says the jug is easily replaced, and the yogi retorts that the queen is too. They agree that the yogi will restore Queen Pingala to life if the king replaces the jug. The king commandeers the labor of scores of potters, but the yogi uses his "divine play" (lila ) to spoil the potters' work so they fail to get the original jug's color just right. When cartloads of jugs are delivered by exhausted potters, Gorakh Nath scorns them, holding up his shards of a slightly different color, and demanding once more a jug just like the one that broke:

So King Bharthari grasped his feet and prostrated himself. "Grain-giver, I've done the best I could, good or bad, I've ordered what I could. Now, Grain-giver, that's enough. Good or bad, black or fair, make me a Pingala. Just as I've brought these jugs, black or yellow, so bring her, black or yellow."

Of course, the yogi is able to summon up not one but seven hundred fifty identical queens and the sameness of their faces, clothes, and jewelry are elaborated upon to the audience's considerable wonder. On the surface the point seems to be that yogis are more powerful than kings or potters: without divine power, a king can't even replicate the form and color of a common clay jug; with it a yogi can infinitely multiply the form and color of a human being who has burned to ash.

Gorakh Nath's pottery lesson, however, goes beyond such trumpeting of yogis' magic power. For even perfect reproductions are illusions, if there is no graspable reality in the original. This lack of reality operates on several levels. We do not even know whether any of the seven hundred fifty Pingalas is the real Pingala—since she burned up and all these may just be Gorakh Nath's saktis , enslaved female spirits in Pingala's form. But, even if one of the restored queens is the real one, she is still no better than a whore (as Gorakh Nath makes clear) because no human love endures forever. All of them, perfect copies though they are, are just as false as the cartloads of jugs that do not match the original jug. They represent distractions from higher or calmer realities for which the yogi's unblemished and irreplaceable jug of pure cool water may itself be a sign.

Walter Benjamin's pottery lesson indicates that translating from one language to another might be like the act of matching fragments to rebuild a shattered whole, but that this work is neither perfect reproduction nor an illusory effort doomed to failure. Ultimately, Benjamin's images push our thoughts beyond the translator and his work, to consider the relation between languages, suggesting that a shared human capacity for communication exists beyond particular tongues.

Why do I thus laboriously juxtapose these very different uses of broken-pot images emerging from different cultural discourses and created for different didactic aims? One solid if small reason is that it seems to me auspicious that for both Nath yogis and European literary criticism a broken pot and its reconstruction or replication may become metaphors for the possible and the impossible, indicators of communication between two worlds (whether of French and German poetry, or of yogis and kings, or of Rajasthani peasants and Western readers). One ephemeral but larger reason for this pottery lesson is that both Benjamin's and Gorakh Nath's metaphors point beyond cycles of disintegration and reconstruction to some more stable area of light

or truth. For those of us who spend our days translating texts and cultures, this is encouraging.

Yellow or black, I have tried to make these tales stand up. Lacking yogis' magic along with much other knowledge and skill, I have labored even longer and harder than Bharthari's potters. I can only hope that the imperfect results presented here are, as Benjamin advises, limpid to the light of the original.

Chapter Two

Naths or Jogis in North India

The preceding chapter introduced Madhu Nath, the storyteller, as an individual and located him in the rural society of Rajasthan where he lives, sings, and explains his tales. Here I shall selectively explore some broader contexts of Madhu's knowledge, while continuing to touch base within the corpus of his performed texts. The tales of Gopi Chand and Bharthari as sung and told by Madhu Nath belong to a loosely bounded but nameable tradition whose roots reach back at least to the tenth or twelfth century. I shall speak of this as the Nath tradition, but its adherents or practitioners are often popularly designated Jogi , or in some areas Jugi —vernacular derivatives of yogi .

Throughout this book I use English "yogi" rather than jogi , unless referring to a specific caste in a specific region by its name of record. And I use the terms Nath and yogi interchangeably, except when focusing on the significance of their respective etymologies. Nath teachings and stories flow as one stream within popular Hinduism, contributing to and drawing from several others. The purpose of this chapter is to give readers of Gopi Chand's and Bharthari's tales a sense of these stories' roots, and of the bard's roots, within such broader cultural, historical, and religiohistorical patterns.[1]

One way of understanding the popular stories of the Naths, including Madhu's tales, is to consider them as didactically motivated representations of renunciation. In these representations both a high

[1] The progression of this chapter very deliberately leads to the tales that are our central focus. Others have written about Naths themselves as a focal topic; those seeking a fuller and more "disinterested" treatment are referred to them: Briggs 1973; Dvivedi 1981, n.d.; Mahapatra 1972, 75–96; Pandey 1980.

evaluation of world-renunciation and an appreciation of the sacrifices entailed by acting on that evaluation are transmitted for the edification and entertainment of householders.[2] The stories provide an interface between two distinguishable although intricately linked social and religious universes.

In thus formulating as separable but interwoven the lifestyles and worldviews of householders and yogi ascetics, I do not intend to address directly the big issues of "man-in-the-world" versus "world-renouncer" in pan-Indian thought. These issues have been elegantly if misleadingly formulated by Louis Dumont and worried over by many others including myself.[3] Although the following discussion may shed some light on those vexed matters, my focus is on a smaller-scale but still complex contrast. This is the contrast between householder or grihasthi Naths who form hereditary castes ( jatis ), and renunciatory or naga Naths—using naga here in its unmarked sense of celibate member of a Nath sect.[4] It seems no accident that it is frequently grihasthi Naths who purvey—not only to their own communities but to society at large—the stories of Gopi Chand and Bharthari, in which the central figures are, or become, naga Naths.

I begin by considering the term Nath as it is applied to renouncer members of a sampraday or religious sect.[5] In this context the category

[2] For an interpretive approach to these issues, see the afterword. See also Gold and Gold 1984.

[3] For Dumont's formulation see Dumont 1970; for some reflections on, reactions to, and conflicts with Dumont see, for example, Bradford 1985; Burghart 1983a, 1983b; Das 1977; Gold 1988, 3–4; Madan ed. 1981.

[4] Meaning four under the masculine noun nagau in the RSK is nath sampraday ka vah vyakti jo vivah nahin karta hai "a member of the Nath sect who does not marry." During interviews in the winter of 1987–88 I heard both Rajasthani renouncer and householder interviewees regularly employ naga in opposition to giihasthi . Used thus, naga does not refer to the particular sect of Shaivite renouncers who go naked (the primary adjectival meaning of naga ) or to the "fighting nagas "—famous battalions of these unclothed ascetics, whose participation in local military struggles is recorded in Rajasthan and elsewhere.

[5] Some scholars argue that "sect" may not appropriately translate Hindi/Sanskrit sampraday . Barz, following Wach, shows etymologically that sampraday refers positively to a "vehicle for transmission of doctrine" whereas "sect" has negative implications of a splinter group. However, sampraday also suggests a "refuge" from the ordinary world, as sect may; Barz continues to use it (Barz 1976, 39–40). More recently, van der Veer prefers "order" or "monastic order" to sect because the "church-sect dichotomy" is so alien to Hinduism (van der Veer 1988, 66–71). Like Barz, I find it convenient to use "sect" here; like van der Veer, I warn against a false jump to Christian parallels.

"Nath" is a rubric that may cover any number of loosely organized associations of Shaivite renouncers, sharing certain orientations and practices.[6] BeSides referring to a sectarian identity, the term Nath evokes a particular set of ideas concerning the merged physical and spiritual perfection possible for humans, and how to achieve it. And, not the least important in relation to our tales, Naths are strongly associated in popular thought with certain visible emblems, appurtenances, and behaviors.

I turn then to the phenomenon of householder Naths: castes whose group identity is rooted in renunciation. Such is Madhu Nath's birth group ( jati ), and it is not unique. Similar castes are present throughout India and Nepal.[7] The distinction between Nath as sect or path and Nath as caste is pronounced and critical in indigenous accounts. However, as will soon become apparent, it is also imprecise, plastic, and subject to collapse at several levels.

Nath Renunciatory Traditions in Story and History

Nath may be simply defined as "master" and the Naths as "'Masters' (of yogic powers)" (Vaudeville 1974, 85). Other sources report various complex etymologies deriving from possible syllabic deconstructions of the word nath , producing meanings such as "form of bliss established in three worlds" or "he who removes ignorance of Brahm and is absorbed in truth-consciousness-bliss" (Lalas 1962–78).[8] A yogi is an adept, a practitioner of yoga—deriving from a Sanskrit root meaning "yoke," carrying implications of self-discipline as well as union. Yoga

[6] Classifications and descriptions of various and variously organized groups of Nath renouncers are available elsewhere (Briggs 1973; Dvivedi 1981; Oman 1905, 168–86; Sinha and Saraswati 1978, 113–14; Tripathi 1978, 71–74); Nath traditions, rather than monastic organization, are my focus here.

[7] For two interesting examples see Bradford 1985, a discussion of how the South Indian Lingayat caste maintains its renouncer identity through historical and social changes; and Bouillier 1979, an ethnographic study of a renouncer caste in Nepal. On relatively recent fieldwork with other North Indian Jogi performers see Champion 1989; Henry 1988; Lapoint 1978. That a number of Jogi groups are nominally Muslim is a phenomenon well worth investigating, but I lack data and space to do it justice here.

[8] For other definitions and etymologies of Nath see also Dvivedi 1981, 3; Singh 1937, 1; Upadhyay 1976, 1–6.

is one of the six darsanas or major classical philosophical systems known in Indian thought.[9] But in relation to Nath traditions it refers particularly to various physical and meditative techniques for selfrealization. [10]

Most scholars treat the terms Nath and yogi as interchangeable when dealing with the sect and its teachings (for example Vaudeville 1974, 85–86).[11] Many, for the sake of clarity, settle upon one or the other to use when speaking of that tradition.[12] The terms Nath and yogi are far from exhausting the descriptive designations applied to Naths. Briggs discusses "Gorakhnathi," "Darsani," "Kanphata," and "Natha"—all categorizations with identical or overlapping references that at times designate members of the sect(s) with which he is concerned (Briggs 1973, 1 2). Whereas the first in the series refers to the founding guru, the second two highlight the most visible and distinctive emblem of the group—their large earrings (darsani ) worn in split ears—the descriptive meaning of kanphata .[13]

The origins of Nathism dissolve in the mists of a presumed selective merging of Buddhist and Hindu tantra, Shaivite asceticism, and yoga philosophy and practice that took place somewhere in the tenth or eleventh century (Briggs 1973; Ghurye 1964; Schomer 1987). A shadowy but imposing figure looming in those mists is Gorakh Nath—who probably lived but whose biography is totally overlaid with myth and magic.[14] Although some locate Gorakh's birthplace in northwestern India (Sen 1954,74; Singh 1937, 22) and his lore certainly flourished in Punjab, merging with indigenous tales much as it has done in Rajasthan, most cultural historians agree that the real Gorakh came from the east. Briggs, who mustered most of the sources available in his time in admirably systematic fashion, concludes that "Gorakhnath lived not later than A.D. 1200, probably early in the 11th

[9] Sources for yoga as philosophy include Dasgupta 1924, 1974; Woods 1972; Raju 1985, 336–76.

[10] See Eliade 1973; Varenne 1976; Sinh 1975.

[11] Yogi, of course, may and often does have myriad associations unconnected with Naths.

[12] Ghurye uses "jogi" (Ghurye 1964, 114–40) and Oman "yogi" (Oman 1905, 168); Dasgupta prefers Nath (Dasgupta 1969, 191–210).

[13] I follow Dvivedi 1981 and Sundardas 1965 in spelling the sect name; others use kaphata (Briggs 1973) or kanphata (Ghurye 1964).

[14] For a full hagiography of Gorakh Nath (also Gorakhnath; Goraksanath) in simple Hindi see Gautam 1986; see also Briggs 1973, 179–207; Dikshit n.d.; Pandey 1980; Sen 1960, 42–54.

century, and that he came originally from Eastern Bengal" (Briggs 1973, 250; see also Dvivedi 1981, 96–97).