3. The Capitalism of the Spirit, 1650–1700

8. A Shoemakers’ Holiday

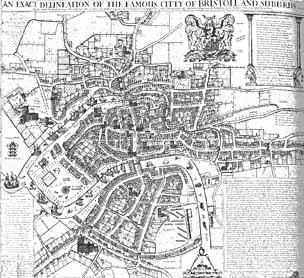

Through much of its history, Bristol had looked to the Atlantic for its fortune. Its sailors were already busy in Iceland’s waters at the beginning of the fifteenth century.[1] But until the mid-seventeenth century, their inner eye was always elsewhere. When they surveyed the ocean they saw either the fish they needed in their quest for the wealth of the Iberian and Mediterranean markets or the passage that would take them directly to the riches of the East. It was only in the 1620s and 1630s that the English settlements in the Americas began to produce goods that attracted Bristol’s merchants and suggested the genuine possibility that America might be as lucrative as the markets of southern Europe or even the pleasure domes of Asia. At first this new trade, profitable though it could be, was conducted on a very small scale. But by the 1650s it had grown considerably in volume. Now ships were returning to Bristol from the Chesapeake and the West Indies by the dozen, not just in twos and threes. This growth, however, represents more than a change in the character of this trade. It also reveals a change in the nature of the trading community that conducted it and in the political economy governing the city’s life. Trans-Atlantic commerce became in an almost literal sense a shoemakers’ holiday, an arena in which small men—artisans and shopkeepers—could, like Thomas Dekker’s Simon Eyre, play the merchant.

Sometimes historical processes of this magnitude are captured in a single source. Such a document, when we are lucky enough to come upon one, can let us see a whole world in a grain of sand, as it were. It can show us its larger structures in interaction. For late seventeenth-century Bristol we have just such a source in the city’s Register of Servants to Foreign Plantations, calendaring the indentures of over ten thousand individuals who migrated from England to America through Bristol between 1654, when the Register begins, and 1686, when the last entries were recorded. It reveals a city at the center of colonial trade, supplying Virginia, Maryland, and the West Indies with the labor necessary to make their settlement successful. This source has long been known to students of seventeenth-century colonization in the New World and of geographical mobility in England itself.[2] But along with evidence of the early migration to the West Indies and the Chesapeake, it also yields insight into the economic, political, and ideological developments affecting Bristolians in the era that followed the Civil Wars. Within it, the main facts and forces of change affecting early modern Bristol have converged. To pursue the story of social and political change we have been telling, then, I propose to examine the history of this Register in some detail, as a way of understanding Bristol’s encounter with the newfound land into which it and its people had now entered. As we shall soon see, the Register’s dry-as-dust pages contain within them something of the world of the shoemaker merchant.

The story of the Bristol Register has been colored from the outset by the social problem it professed to remedy. According to the September 1654 city ordinance that established this book of enrollments, it originated in response to the

Not surprisingly, these dramatic words have attracted the attention of nearly every modern writer who has discussed the ordinance or the Register.[4] But no one has asked what prompted these charges of man-stealing or whether they present a satisfactory explanation for the Register’s existence. An answer to the first question will show on reflection that they do not.many complaints…oftentimes made to the Maior and Aldermen of the inveigling purloining carrying and Stealing away boyes Maides and other persons and transporting them beyond Seas…without any knowledge or notice of the parents or others that have the care and oversight of them.[3]

In September 1654, Bristol’s government had only one relevant case before it. It involved Farwell Meredith, an orphaned, runaway apprentice, who had importuned passage aboard the Dolphin of Bristol, bound for Barbados, and upon arrival had been sold as a servant to a planter there. According to a deposition given by several of the Dolphin’s crew, Meredith first came to the ship on 14 October 1653, when he was rescued from the tidal flats at Kingroad onto which he had ventured in his efforts to board the vessel. The following morning Marlin Hiscox, the ship’s carpenter, asked the young man whether he would go ashore, but, according to the crewmen, Meredith responded that “he would leape overboard rather than goe on shore and yt he would goe to ye Barbadoes where he said he had a brother.” With this the runaway entered himself into the “Merchants booke” by the name of John Chetwind of Gloucester, and only later at sea did he reveal his true name to be Meredith. When the Dolphin reached Barbados, Hiscox and John Blenman, the ship’s supercargo, put young Meredith in service in a plantation “according to the Custome of the Iland,” in return for which John George, the planter, promised Hiscox and Blenman a quantity of sugar. But Meredith refused to serve, saying “he would not worke for he did not come thither to worke for he was a gentlemans sonn & if he had thought he should have been sold he would never have come along with…Hiscox.” His refusal resulted in severe beatings from the planter. Meredith arrived in Barbados just before Christmas 1653. At about the same time, efforts began in Bristol to recover the young man. By July 1654, his guardian had initiated proceedings in the Bristol Mayor’s Court on actions of trespass and assault. The matter was still before the court on 11 September, when the last of a series of depositions was taken.[5]

Instead of a case of kidnapping in the strict sense of the word, what we have here is an allegation of “spiriting”—that form of treachery through which, according to contemporaries, countless men and women in the mid-seventeenth century were “enticed” or “seduced” into bonds of servitude in the plantations.[6] In this story, the runaway Farwell Meredith apparently learned only at the end of his journey of the custom of paying in service for passage to the colonies. But his case differs little in practice from the more common cases in which “spirits” gulled their victims into voluntarily sailing to Virginia or the West Indies with false tales of rich prospects upon completion of their service. In all these instances the hapless person found himself bound in a contract for labor which he had entered without his informed consent. There can be little doubt that “spiriting,” and perhaps also kidnapping, were sometimes practiced in mid-seventeenth-century Bristol. As early as 1644, for instance, an accusation arose against Michael Diggens, a Bristol mariner, for being “an old Roge” who “Cozened…many men and brought them out of the Country.” In the mid-1650s and early 1660s the Bristol archives record examples of nearly half a dozen man-stealers, kidnappers, and spirits.[7] But granting the prevalence of this evil and the widespread desire to crush it, the question remains: in September 1654 did the Bristol Common Council intend only to remedy this wrong, or did it have broader aims?

The ordinance established a simple arrangement for regulating the traffic in servants from Bristol. To prevent “mischeifes,” it required

However, this seemingly straightforward procedure conceals a rather puzzling fact.[9] By treating servants’ covenants as in the same class as indentures of apprenticeship, it placed them in a category of contract into which minors could freely enter without their parents’ consent.[10] Apprenticeship indentures were normally bipartite agreements, with reciprocal obligations made exclusively in the names of the master and the servant.[11] In the mid-seventeenth century, English law on this subject was clear and unchallengeable. Coke, in his Commentary upon Littleton, for example, laid it down as “common learning” that “an infant may bind himself…for his good teaching or instruction, whereby he may profit himself.”[12] Even though the courts held that ordinarily a master could not sue an underage apprentice for damages upon such a covenant, the indenture remained binding.[13] As the judges say in the case of Gylbert v. Fletcher (1630), if the servant “misbehave himself, the master may correct him in his service, or complain to a justice of the peace to have him punished.” In this fashion local police powers rather than private litigation insured the apprentice’s adherence to his covenants.[14]all Boyes Maides and other persons which for the future shall be transported beyond the Seas as servants…before their going aship board to have their Covenants or Indentures of service and apprenticeship inrolled in the Tolzey booke as other Indentures of apprenticeship are and haue used to be and that noe Master or other officer whatsoever of any ship or vessell shall (before such inrolment be made) receive into his or their ship or vessell or therein permit to be transported beyond the Seas such Boyes Maides or other persons.[8]

Requiring indentures from all servants bound to the plantations might prevent future complaints of the type made by Meredith and his guardian, but it could neither halt the activity of “spirits” who chose to operate within the rules nor prevent the escape of runaways who chose to abuse them. At best, it placed only a minor obstacle in their paths. Provided the “spirit” had induced his underage victim into signing an indenture, no real hindrance stood in the way of transporting him beyond the seas to the complete ignorance of his family or master. Moreover, any runaway willing to conceal his past could easily avoid detection, as the Dolphin’s crew claimed Meredith had done. In 1654, therefore, the Bristol Common Council acted more to set the trade in indentured servants on a secure legal footing than to attack the evil of “spiriting” proper.[15]

The registration procedures themselves lend some credence to this view. Although servants usually appeared at the Tolzey to acknowledge their indentures as they were being drawn and enrolled,[16] nothing in the Bristol legislation required them to do so, and it was possible—as with apprenticeship—for the master to present indentures already in being for the clerks merely to enroll.[17] During some periods servants seem already to have been aboard ship when their indentures were presented, a fact which must have made seeking acknowledgment of the contracts no more than perfunctory.[18] Moreover, nothing in the Bristol ordinance demanded consent from parents or masters before indentures for underage servants could be entered, and the Bristol Register mentions such consent only once in all its ten thousand entries.[19] A master could even legitimately avoid bringing a servant before the clerks to acknowledge his indenture, “for feare of [his] running away.”[20] If the problem of runaways was the primary concern of the Bristol magistrates, these arrangements appear woefully inadequate to their task. The welfare of the servants hardly seems to have been what was at issue.

We also miss the point, however, if we look at the Bristol ordinance primarily as a means of securing the servant trade in the interests of the traders. The ordinance’s most salient feature, its lengthy enforcement clause, suggests that the Common Council’s main purpose was not to protect either servant or master, but to require the use of indentures by traders not otherwise disposed to employ them. The enforcement clause imposed a £20 fine on all ships’ masters who received servants for transportation before the enrollment of their indentures. Violators were to be punished either by distress and sale of their goods or by action of debt sued before the Mayor’s Court by the city chamberlain.[21] Those who informed against violators stood to gain one-quarter of the fine. Finally, the councillors provided that the water bailiff should from time to time

Presumably the water bailiff also stood to collect £5 for each fine that was recovered. No more thoroughgoing administrative arrangement for the enforcement of a local ordinance existed in mid-seventeenth-century Bristol.[23] The councillors clearly wanted each servant, of whatever age or description, to have an indenture, yet they expected some of the servants’ masters and some of the ships’ captains to resist the requirement. In order to see the significance of this simple administrative point we must turn our attention from legislative interpretation to political history.make strict and diligent search in all ships…after all Boyes Maides and other persons that are to be transported as Servants beyond the Seas and if vppon examinacon he find any such Boy maide or other person which haue not their…Indentures of service and apprenticeship so inrolled in the Tolzey booke as aforesaid then the Water bailiff shall immediately give an Accompt thereof to the Maior or some of the Aldermen who are desired…to take such speedy course therein as by Law they are enabled to doe.[22]

The men who passed the servant ordinance of 1654 represented the same mercantile elite that had long dominated Bristol. They came from a narrow range of the city’s most lucrative occupations (Table 24). Of the twenty-one merchants who attended the council session on 29 September, some had themselves participated in the colonial trades during the 1650s (Table 25). However, most of them engaged much more heavily in traffic with Bristol’s main continental markets in France, the Iberian peninsula, and the Mediterranean. Only a handful of the councillors appear, directly or through their agents, among the dealers in servants. The council’s American traders—slightly over half the membership—primarily enjoyed the fruits of the import trade in sugar and tobacco, not the difficulties of the export trade in human labor. Of the twenty-four councillors who belonged to Bristol’s Society of Merchant Venturers, twenty had become members before the marked liberalization of admissions standards in 1646.

| No. | Merchant Venturer Members as of 29 September 1654[a] | |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Bristol Record Office, Common Council Proceedings, vol. 5, p. 72, compared to Bristol Record Office, MS 04220 (1), and Society of Merchant Venturers, Wharfage Book, vol. 1. The occupations of council members are based on prosopographical research using wills, court records, apprenticeship and burgess books, and similar sources. Membership in the Society of the Merchant Venturers was established from Patrick V. McGrath, ed., Records Relating to the Society of Merchant Venturers of the City of Bristol in the Seventeenth Century (Bristol Record Society 17, 1952), pp. 27–32, 261. I am grateful to Dr. Jonathan Barry for his assistance in assembling the data from the Wharfage Book. | ||

| Merchant | 21 | 20 |

| Mercer-Linendraper | 8 | 3 |

| Woolendraper | 2 | 1 |

| Grocer | 2 | |

| Ironmonger | 1 | |

| Vintner | 1 | |

| Soapmaker | 1 | |

| Brewer | 4 | |

| Total | 40 | 24 |

| Traders[a] | Merchant Venturers | Non–Merchant Venturers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Bristol Record Office, MS 04220 (1), and Society of Merchant Venturers, Wharfage Book, vol. 1, compared to Bristol Record Office, Common Council Proceedings, vol. 5, p. 72. | |||

| Certain | 17 | 3 | 20 |

| Possible | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 19 | 5 | 24 |

In order for us to understand what disturbed these men about the traffickers in servants, we need to return to the case of Farwell Meredith. The men responsible for “spiriting” Meredith to Barbados represent a nearly ubiquitous but largely unregulated element in Bristol’s mercantile community in the mid-seventeenth century. They were “interlopers” according to the Merchant Venturers’ definition. John Blenman, the Dolphin’s so-called merchant, was in fact a shipwright’s apprentice. His master, Richard Basse alias Philpott, probably owned all or part of the vessel and with it engaged in overseas commerce as an adjunct to his trade of shipbuilding. To the tradition-minded overseas merchant, such an individual threatened the stability of the market both at home and abroad and usurped the rightful place of the true merchant, whose skills alone assured a steady trade at reasonable prices. Marlin Hiscox, the Dolphin’s carpenter, symbolized an even greater challenge to the traditional commercial order. Unlike Basse, he did not enjoy the freedom of Bristol. Never having sworn the burgess oath, he possessed no ordinary trading rights within the city. The sugar that John George owed him for Meredith’s labor might as well have belonged to a foreigner or stranger who legally could bring goods to port only under economic restrictions.[24]

John Blenman, Richard Basse, and Marlin Hiscox were typical of the men who engaged in Bristol’s American trades in the 1650s. In contrast to the city’s traffic with the European continent, still largely in the hands of the Merchant Venturers, this trans-Atlantic commerce was not conducted primarily by traditional wholesale merchants. A broad spectrum of crafts was represented among the hundreds of individuals who indentured servants to themselves between 1654 and 1660. Judged by the entries in the Register, as David Souden has noted, “the whole Bristol trading community appear to have been involved in the trade of sending servants to the colonies.”[25] However, this is only part of the picture. As a practical matter, a profit could only be returned from the West Indies and the Chesapeake markets in the form of commodities.[26] In general, the shippers of servants seem to have initiated transactions as speculative ventures and were paid in colonial products only when they sold their cargoes in the colonies.[27] Fortunately, we can study the import side of Bristol’s trade with these markets by using the records of the wharfage duty kept by the Society of Merchant Venturers.[28] Viewed together with the Register of Servants, the wharfage records yield an astonishing picture of Bristol’s colonial trading community. Even the importers were far from being a body of traditionally trained merchants. In the two-year period after May 1654, when the Wharfage Books begin, four hundred and twenty-three individuals imported colonial sugar and tobacco. Thirty were women; some of these were themselves planters, but most were the wives or widows of mariners and shopkeepers who engaged in the trans-Atlantic traffic. Of the three hundred and ninety-three men, we know the occupations of three hundred and five. The vast majority were Bristolians, but on the whole they were not merchants. Somewhat surprisingly, only about 26 percent of the list can be identified with this occupation, at least as it is narrowly defined (Table 26). For the rest, soapboilers, grocers, and mercers were especially prominent among major retailers and manufacturers, and tailors, shoemakers, and metal craftsmen among those in the lesser trades. In the shipping industry, mariners, coopers, and shipwrights account for the majority of those engaged in the traffic.[29]

| Importers[a] | Shippers of Servants[b] | Both | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Source: Bristol Record Office, MS 04220 (1); Society of Merchant Venturers, Wharfage Book, vol. 1; the names were cross-checked with other sources, including wills, Merchant Venturer records, apprenticeship and burgess books, and the Bristol deposition books. | ||||||||

| Men | ||||||||

| Leading entrepreneurs | ||||||||

| Merchants | 80 | 26.23[c] | 34 | 15.11[d] | 18 | 21.69 | 96 | 21.48 |

| Other leading entrepreneurs[e] | 80 | 26.23 | 20 | 8.89 | 11 | 13.25 | 89 | 19.91 |

| Total | 160 | 52.46 | 54 | 24.00 | 29 | 34.94 | 185 | 41.39 |

| Lesser crafts and trades[f] | 30 | 9.84 | 11 | 4.89 | 5 | 6.02 | 36 | 8.05 |

| Gentlemen, professionals, etc.[g] | 4 | 1.31 | 5 | 2.22 | 9 | 2.01 | ||

| Shipping industry[h] | 100 | 37.79 | 121 | 53.78 | 41 | 56.63 | 180 | 40.27 |

| Planters | 11 | 3.61 | 34 | 15.11 | 8 | 9.64 | 37 | 8.28 |

| Total known | 305 | 225 | 83 | 447 | ||||

| Total unknown | 88 | 5 | 1 | 92 | ||||

| Total | 393 | 230 | 84 | 539 | ||||

| Women | 30 | 8 | 2 | 36 | ||||

| Total men and women | 423 | 238 | 86 | 575 | ||||

| Importers, 15 May 1656–24 March 1656/7 | 38 | 6 | 44 | |||||

| Adjusted total[i] | 461 | 238 | 92 | 619 | ||||

The representation of Merchant Venturers among the colonial importers is also revealing. In all, only seventy-six importers of Virginian and West Indian commodities in this two-year period were associated with the Society at some point during their lifetimes, and only twenty-four had entered the organization before 1646. Twenty-nine became members only after 1656, eight of them after 1670 (Table 27). According to the Wharfage Book, many of the older members of the Society who engaged in trans-Atlantic commerce still bought sugar at Lisbon, while others who did not engage in colonial trade at all also frequented Lisbon for sugar.

| Merchant Venturers | Importers | Shippers of Servants | Both | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Comparison of Bristol Record Office, MS 04220 (1); Society of Merchant Venturers, Wharfage Book, vol. 1; Patrick V. McGrath, ed., Records Relating to the Society of Merchant Venturers of the City of Bristol in the Seventeenth Century (Bristol Record Society 17, 1952), pp. 27–32, 261. | ||||

| Admitted before 1646 | 24 | 6 | 2 | 28 |

| Admitted 1646–1656 | 23 | 5 | 5 | 23 |

| Admitted after 1656 | 29 | 12 | 6 | 35 |

| Total[a] | 76 | 23 | 13 | 86 |

If we analyze the exporters of servants during the first two years of the Register, we get a picture of trade dominated yet more heavily by those who were not Merchant Venturers. Men identified as merchants represent only about 15 percent of the servant traders, and the role of the Merchant Venturers was smaller still, amounting to only 10 percent of the total (see Tables 26 and 27). Although some of Bristol’s better-established overseas merchants, like Joseph Jackson, John Knight, and William Merrick, imported substantial quantities of colonial products in these years, such men did not dominate the colonial trades in the way they did the European ones. Instead, members of the shipping industry appear to have taken the largest share of the business (see Table 26).

These characteristics of the colonial trading community become even clearer when we consider trans-Atlantic commerce as a two-way traffic, with each shipment of servants resulting in a return cargo of sugar or tobacco. Between 30 September 1654 and 29 September 1656, two hundred and thirty-eight persons appear as masters in the Register of Servants, but only slightly more than a third of these traders imported any colonial products through Bristol from mid-May 1654 to late March 1657. During this overlapping thirty-four-month period, a total of six hundred and nineteen individuals traded with the American colonies, vastly exceeding the numbers who regularly traded in any way with Bristol’s traditional markets in Europe and the Mediterranean. But only ninety-two men and women, or about 15 percent, were two-way traders who exported servants as well as importing colonial sugar, tobacco, and other goods.

Since many of the importers must have sent manufactured goods and other items to the colonies rather than servants, the absence of their names from the Register of Servants should be no surprise. But how did the servant traders who, according to Table 26, appear to have done no importing manage their affairs? A number of possible explanations suggest themselves. Returns from the colonies may have gone to another English port, such as Plymouth or London, though no evidence of such a pattern has come to light. Perhaps some Bristolians sought to avoid English customs by bringing their imports directly to market in Europe, in violation of the Navigation Acts. If such illicit transshipments occurred we should find some evidence of them when the traders returned to Bristol with European goods paying wharfage duty. We find just the contrary. The vast majority of colonial traders rarely, if ever, imported continental commodities to the city.[30]

The true explanation of the imbalance between exporters of servants and importers of sugar and tobacco lies in the social organization, not in the economics of the colonial trade. Most of the “masters” who appear in the Register and not in the Wharfage Book must have been agents for principals who actually financed the trade, enjoyed its profits, and appear only in the Wharfage Book. Many of the figures designated in the Register as masters, such as Gabriel Blike, William Rodney, Henry Daniel, John Vaughan, and Robert Culme, in fact were apprentices acting as factors or supercargoes for their own masters, on whose account trading took place.[31] Blike, for example, shipped eight servants, mostly to Barbados, between 1654 and 1656 while he was apprenticed to Walter Tocknell, but imported no colonial goods during that time. Tocknell, by contrast, shipped no servants but imported large quantities of sugar and tobacco.[32] Seafaring men such as mariners, shipwrights, coopers, and surgeons, sailing aboard vessels bound for American waters, could offer the same service to those in Bristol who traded to the colonies less frequently or who could not spare an apprentice for the long journey.

This seafaring population represented a potential threat to the principles and practices of the traditional merchant. Ships’ crews had a long-standing right to conduct trade on their own account in the vessels on which they sailed, and, as we have just seen, many mariners took advantage of this custom to import colonial products in their own name. But the mariners’ privilege sometimes concealed illicit trade by non-freemen who merely used the good offices of sworn burgesses to escape restrictions imposed on the commerce of “foreigners.” As we know, from the Middle Ages onward this “colouring” of strangers’ goods had been roundly condemned as a violation of the spirit of the urban community. Every freeman took a solemn oath against the practice. Mariners, however, had strong incentives to violate this oath, if they had ever sworn it. Not only did they often lack the capital with which to conduct trade on their own, but they spent far too much time at sea to dispose properly of the goods they imported. By allowing other individuals to trade through them, they could profit from a privilege that they might otherwise never use. Sometimes the strangers for whom they colored goods were colonial planters. However, trade by resident non-freemen was a far greater challenge to the principles by which the mercantile community operated.[33] Young merchants, serving aboard ship as factors, supercargoes, or pursers, fell into a somewhat similar category. Although by custom they also could trade on their own account, even during their apprenticeship,[34] they often lacked the capital and the commercial outlets at home to take full advantage of the privilege. Hence they too might be tempted to color strangers’ goods, not only against local ordinances but against the interests of their employers as well.[35]

Bristol’s Merchant Venturers were acutely aware of the problems that the trading privileges of mariners and young merchant factors posed for the control of overseas trade. Their 1639 ordinances complained that mariners

For this reason, the Society forbade any ship’s captain or crew member from putting goods aboard his vessel without the specific approval of two of the chief laders and two of the chief owners. A fine of double freight was imposed for every violation. Moreover, the ship’s purser, under pain of losing his wages, was to inform his principals of the quantity and type of goods brought aboard by crew members. For their part, the factors and apprentices of Merchant Venturers were forbidden to act for “any Stranger or Forreiner not free of [the] Societie.” They were neither to lade any export goods on behalf of the ineligible traders nor to buy any goods abroad for them. The penalties imposed were heavy, amounting to over 15 percent of the value of goods for a first offense and over 30 percent for a second offense.[37] Nevertheless, judging by the number of non–Merchant Venturers in the Wharfage Books and Register of Servants, it is clear that these efforts had failed.have of late very often taken, vpon theire credit and other waies, divers goods and marchandice of great value, And carried the same…vnto the partes beyond the Seas, and in Returne thereof have brought home…divers other wares and marchandice…the most part thereof, without the leave, privitie, or knowledg of the Ouners of the said Shippes, or Marchants whoe tooke the saide Shippes to Fraight…Whereby his maiesty is much deceyved and the marchants disheartened in theire trade.[36]

Roger North long ago observed the same peculiarities in Bristol’s trading community that we have just examined. “It is remarkable there,” he said,

At the Restoration, the London merchant John Bland portrayed the Chesapeake traders—especially those he believed had procured the passage of the Navigation Acts—in much the same way. “They are no Merchants bred,” he complained,that all men that are dealers, even in shop trades, launch into adventures by sea, chiefly to the West India plantations and Spain. A poor shopkeeper, that sells candles, will have a bale of stockings, or a piece of stuff, for Nevis, or Virginia, &c. and, rather than fail, they trade in men.[38]

North and Bland present a dark vision—to them, a nightmare—of a bustling, disorderly world of small men advanced beyond their stations. Bristol’s old-line Merchant Venturers would have deemed their description a prophecy of doom all but come true.not versed in foreign ports, or any Trade, but to those Plantations, and that from either Planters there or whole-sale Tobacconists and shopkeepers retailing Tobacco here in England, who know no more what belongs to the commerce of the World, or Managing new discovered Countries, such as Virginia and Mariland are, than children new put out Prentice.[39]

Their viewpoint, upheld largely unchanged down to 1639, not only reflected their economic interests but had conformed to the economic and social realities of overseas trade as well. So long as commercial profits were derived primarily from scarce and high-priced imports drawn from a small number of continental markets, successful trade depended on the maintenance of regular mercantile networks abroad and a complex form of organization at home. As we know, merchants habitually acted as agents, partners, creditors, and brokers for one another, switching roles as circumstances required. They chartered ships together and used each other’s servants as factors in overseas trade, and much of their business abroad proceeded through fellow Bristolians resident in the principal foreign markets trading for commission on behalf of their brethren at home.[40] Even though Merchant Venturers had reason to concern themselves with the overseas trade of artificers and shopkeepers, the actual conditions of foreign commerce limited the danger, since the Society of Merchant Venturers could readily control that trade. Only the Society’s membership commanded the necessary capital and organization to conduct such commerce on a consistently large scale. They owned the shipping; they had the foreign contacts; and they enjoyed the services of fellow merchants to help them drive the trade. The high prices of the luxury goods in which they dealt, moreover, would have kept all but the wealthiest of retailers from competition with them. In 1618 and 1639, the Merchant Venturers had relied on these truths when framing their ordinances. Since others who would attempt to trade could be barred from the services of the factors, servants, and mariners traveling abroad for the Merchant Venturers, craftsmen and shopkeepers would need to acquire their own shipping, establish their own credit network, and build their own organization in foreign markets to conduct their trade. The Merchant Venturers counted on them being unable to do so.

Across the Atlantic, however, a new commercial world was taking shape. The inhabitants of the colonies were Englishmen with family and business ties in their home country. The social composition of the colonial communities therefore provided commercial connections between planters and traders which elsewhere required specially established resident factors, commission agents, and brokers to achieve.[41] In a sense, the settlement of a colony already contained within itself the seeds of a mercantile organization to cultivate commerce as it was needed. Moreover, many of the colonists came from the west of England, and even from Bristol itself, which gave the city some particular advantages in the trade.[42]

Among these West Countrymen, a number of Bristol-based merchants and mariners stand out. For example, Anthony Dunn, a Bristol merchant though not a Merchant Venturer, resided in Barbados in the 1650s, leaving his wife behind in Bristol to supply him with servants. He may also have been connected with Richard Dunn and Ann Dunn of Bristol, each of whom also traded between Barbados and Bristol in these years. Another emigrant Bristol merchant was John Yeamans, brother of Robert, the Bristol martyr to Charles I’s cause in 1643, and himself an ex-colonel in the Royalist army. He settled on Barbados in 1650, later to become one of the great men of the island, governor of Carolina and a baronet. Other members of his family, however, remained in Bristol to trade with him. In 1654–55, when his Barbados holdings probably were still undeveloped, one hogshead of sugar was registered in his name for wharfage duty owed at the Backhall.[43] Richard Allen, a ship’s surgeon with political views nearly opposite to those of Yeamans, also became a colonial planter in these years, although in Virginia, not Barbados. And Robert Glass, mariner, reversed the process. In the 1640s he lived as a planter in Barbados, doing business with Bristol, but by 1655 he had set up as a merchant in the western port to conduct trade with his former West Indian neighbors. Finally, in 1657, he became a freeman of the city after marrying the daughter of John Dee, cooper. Dozens of such stories could be told.[44]

The early Chesapeake and West Indian colonists, moreover, traded under conditions far different from those experienced by commercial dealers in Europe. Rather than develop production in a variety of necessary goods for home consumption, they used their comparative advantage in natural resources—in this case, land—to produce one highly valued commodity, which they exported in return for the manufactured items and other resources that they needed.[45] This type of economy had a profound effect on the character of trade. At the major European ports a merchant could buy a variety of goods, each governed by its own market conditions. To maximize his profits he needed to play these markets with great care, neither committing all his capital to one commodity whose home price might later collapse nor buying everything that seemed quickly merchantable.[46] To purchase these wares, the merchant needed cargoes of quite specific items in high demand and scarce supply among his foreign customers. At Cádiz he might choose among sherry, wine, olive oil, oranges, almonds, and even sugar and tobacco. To acquire them, however, he could use only lead, calfskins, Welsh butter, salt fish, or certain varieties of English cloth. Each of these commodities, of course, also had its own market which needed careful cultivation. A trading venture, therefore, usually involved a complex series of transactions, often requiring numerous brokers and go-betweens, sales at San Lucar de Barrameda and purchases at Jerez de la Frontera, with bills of exchange drawn on Seville.[47]

How different trade looks in the Chesapeake and the West Indies during the mid-seventeenth century. At Jamestown in Virginia, a merchant found tobacco and little else; at Bridgetown in Barbados, he found sugar, with perhaps small quantities of ginger, cotton, or tobacco as well. To get these goods he could bring the most varied of cargoes; the early colonists lacked practically everything in the way of household wares, manufactured items, clothing, and even food and drink—hence the bales of hosiery and pieces of stuff mentioned by Roger North. Most of all they lacked labor. This need was answered by huge shipments of servants that arrived every year from Bristol and London. Since the colonies possessed no system of currency, the colonial merchant operated by a form of barter: so many pounds of tobacco or sugar for so much of this or that. Although by the 1660s elements of a more complex commercial organization had begun to appear,[48] many colonial traders still operated on the same speculative basis that Richard Ligon described for the 1640s, using their vessels as both warehouses and trading counters, bringing mixed cargoes of servants and manufactures to the colonies in hope of finding a market for them. This pattern in much of colonial commerce would have struck the itinerant merchant of the Middle Ages as thoroughly familiar.

The survival of speculative commerce along these lines depended on the settlers as much as the traders. So long as the colonists relied so heavily on sugar or tobacco as a cash crop, they could hardly escape the market economy for many of the goods they needed. Only a few had the capital to serve this market themselves by becoming merchant planters or industrial producers. The others, even those with skills in highly valued manufacturing crafts, looked upon the acquisition and development of land as their best hope of gain. Even the early Chesapeake factors, with their important business connections in England, rarely became shopkeepers trading exclusively at their own risk and on their own account. The more successful among them used their accumulated profits to buy land, not to expand their trading operations.[49] According to Richard Ligon, the Barbados merchants operated in just the same way, pyramiding their commercial gains until they had amassed the funds to set up a sugar plantation for themselves.[50] Under such conditions the growth of sophisticated and well-capitalized commercial institutions was bound to be slow, at first utilized only by the biggest and most ambitious planters, while the others made do with more primitive forms of organization. Until the final decades of the seventeenth century, the trade remained largely decentralized, despite evident signs of increasing concentration.

In its formative years, this emerging Atlantic economy conformed poorly to the economic theories advanced by Bristol’s Merchant Venturers. From the point of view of the settlers, sugar and tobacco, still luxuries in England, were staples. They represented the lifeblood of their economic activities. If they did not have them to sell, the colonists could purchase little they needed.[51] Thus planters were unable to restrict production to uphold prices. Doing so would only idle servants, who nonetheless continued to require maintenance, and waste the labor already expended in clearing land for cultivation. For this reason, planters met falling prices for sugar or tobacco by more intensive efforts at production, not less. As Russell Menard has shown, until about 1680 the faster tobacco prices fell, “the more rapid the growth of output.”[52] Sugar production reveals the same relation to declining prices.[53] Above all, the colonial economy’s dependence upon land conditioned the expansion. During the mid-seventeenth century, planters simply had no alternative ways to use their capital. They could either employ it in growing sugar or tobacco, or they could save it by buying land for later use. Thus, contrary to the Merchant Venturers’ expectations, the prices of sugar and tobacco did not automatically rise when large numbers of traders competed for the goods. Rather, production grew in order to uphold income as prices fell. As a result, the colonial trades in the mid-seventeenth century could not be regulated in the same way as the European. Trade proceeded through too many outlets, and production remained high and continued to grow. Although to the Merchant Venturers, with their traditional viewpoint, the American trades represented the very image of disorder, their Society could offer no ready and easy way to bring discipline to the market.[54]

Not all Bristolians, as we know, agreed with the Merchant Venturers’ view of the proper urban social and economic order. Many of the retailers and artificers saw freedom to trade as a natural concomitant of their status as burgesses. For these shopkeepers and craftsmen, the American trade represented a shoemakers’ holiday of its own. It offered an opportunity to trade abroad in an area outside the control of the Merchant Venturers. It gave small men the chance to use their capital and their contacts to become merchants. Of the many who did so, some indeed were shoemakers. James Wathen, for example, ran a steady business in the American colonies in the mid-seventeenth century. During the early 1650s he traded with both Virginia and Barbados, importing tobacco and sugar and shipping servants. During these same years his brother Richard acted as servant to a Barbados planter, providing James with a business connection on the island. Although Wathen never achieved Simon Eyre’s eminence, like the London shoemaker his commercial activity continued unabated through his later life. After the Restoration we find him still plying the colonial trade just as he had under the Commonwealth.[55]

Wathen’s career not only reveals the ways the emerging Atlantic economy disrupted traditional patterns of commercial life in Bristol but also illustrates how the troubled politics of the 1640s and 1650s had thrown the city into turmoil. For Wathen not only “interloped,” as the Merchant Venturers might have said, in foreign commerce, but in his kinship ties he represented the forces of political and religious radicalism in the city. He came from a large family of middling men—tanners, wiredrawers, shoemakers, pinmakers, and mariners—who not only engaged in American trade but challenged the civic establishment as well.[56] For example, James Wathen, Senior, a pinmaker and cousin of James the shoemaker, was one of Bristol’s more outspoken sectaries in the early 1650s; so was John Wathen, apothecary, another kinsman. John Wathen eventually became a partner in the Whitson Court sugar refinery founded by Thomas Ellis, merchant, in 1665, while other Wathen relations also engaged in American trade. Moreover, Ellis, a leading Bristol Baptist, had gotten his start in the sugar trade in the 1650s by shipping large cargoes of shoes to Barbados, which perhaps links him directly with James Wathen, shoemaker, as well.[57]

The men who “spirited” Farwell Meredith to Barbados share this same combination of religion and economics. Marlin Hiscox and Richard Basse also were tied to a group of active sectaries. The Hiscox clan was closely connected through apprenticeship with William Philpott, a cooper who was Richard Basse’s stepfather—a fact which makes the crew of the Dolphin almost as cosy as an eighteenth-century cousinage. Basse himself grew up in the same household as William Bullock, a shipwright who was one of Bristol’s truly large-scale dealers in colonial goods in the mid-seventeenth century. Both Philpott and Bullock, like James Wathen, pinmaker, and John Wathen, apothecary, appear among the supporters of the radical Colonel John Haggatt in the 1654 elections to the first Protectorate Parliament. Moreover, Bullock and some of the Hiscox family were early Quakers.[58]

Numerous other Bristol sectaries also engaged in colonial commerce during these years. For example, Christopher Birkhead, a mariner who sometimes voyaged to the West Indies and the Chesapeake, was one of Bristol’s more militant saints. In the mid-1650s, Birkhead, by then a follower of George Fox, had already acquired an international reputation as a troublemaker for disrupting Presbyterian services at Bristol, Huguenot services at La Rochelle, and Dutch Reformed services at Middleborough.[59] Captain George Bishop, a New Model Army man, an Agitator at Putney, onetime secret agent to the Commonwealth’s Council of State, Haggatt’s colleague in the 1654 parliamentary election, and early sectary, also engaged in colonial trade in this period.[60] Captain Thomas Speed, another New Model Army man and also by 1655 a leading defender and propagandist for the Bristol Friends, was if anything an even more important American merchant. In the early 1650s he engaged with several other Bristolians in a series of projects to transport Irish prisoners to the colonies.[61] By the middle of the same decade he had become almost as important as William Bullock in American commerce, importing over seventeen tons of Barbados sugar during 1654–55 and accounting for considerable quantities of Virginia tobacco during the following year.[62]

Other American traders among the sectaries led somewhat more sedate political and economic lives. The Baptists Major Samuel Clarke and Robert Bagnall, for example, were the merchants of the Samuel Pinke of Bristol, which Christopher Birkhead sailed for the Caribbean in August 1653.[63] Both of them traded in West India sugar and Virginia tobacco in the mid-1650s. Samuel Clarke’s brother Joseph, a scrivener, and Robert Cornish, a sailor, were also Baptists dealing in American imports in these years. Among the Quaker traders we find such men as the grocers Thomas Ricroft and John Saunders, the ironmonger Henry Roe, the mariner Latimer Sampson, and the merchant Jasper Cartwright. These were middling traders, importing smaller quantities of American goods than Bullock and Speed but maintaining a steady commerce nonetheless. Unfortunately, it is impossible to make a complete tally of the Bristol Baptists and Quakers who invested in colonial enterprise during the mid-seventeenth century, since we do not know the names of all the city’s sectaries in this period. But for the ten years following the establishment of the Wharfage Book and the Register of Servants we can identify more than sixty such individuals in the city who engaged in trans-Atlantic commerce, some trading only once or twice, some like Bullock and Speed among the city’s largest dealers in colonial commerce, but many, like Wathen, conducting a modest but continuous traffic with America.[64]

These men possessed ideals of community and individual commitment different from the hierarchical views held by conservative Bristolians such as the leading Merchant Venturers. In their congregations they had long since rejected the structures of authority of the established church. They believed in a community of the spirit, and they governed themselves through regular meetings at which a democratic ideal of brotherhood prevailed.[65] To men and women reared with these religious convictions, Simon Eyre’s world, as depicted by Dekker, would have seemed far more congenial than the Merchant Venturers’, for the idea of a rigid structure of occupations ranked in a neat hierarchy bore little resemblance to their most profound experiences of community life. It is perhaps no surprise to find them often acting to break down the strict boundaries separating stranger from Bristolian and mere inhabitant from full citizen. The “coloring of strangers goods” was a commonplace of business practice among them. When the civic authorities made a concerted effort to end this ancient misdemeanor in the mid-1660s, they found Thomas Ellis and his Baptist associates heavily engaged in it.[66] Some of the sectaries even began their careers in Bristol as “interlopers” pure and simple. Major Samuel Clarke, for example, only entered the freedom of the city in 1652 after a shipment of imported fruit belonging to him had been seized as “foreign bought & sold.”[67] Moreover, the merchant sectaries, especially the Quakers, could not follow Clarke’s lead in becoming Bristol freemen, since their consciences prevented them from swearing the burgess oath. Many traded illicitly all their lives. Among them perhaps was John Wathen, whose name never appears in the Bristol burgess books.[68]

The year 1654 brought many of these issues of economics, politics, and religion to a head. According to James Powell, Bristol’s chamberlain at the time, there were two causes for the “distempers” of that year: the dispute over the parliamentary election, and “the comeinge of the quakers.” The election, he said, “bred an extreame feud” between the magistracy and the two defeated candidates, Colonel Haggatt and his cousin Captain George Bishop. These men looked upon their opponents as Cavaliers; they accused Alderman Miles Jackson, one of the newly elected members of Parliament, of royalism, made similar charges against those electors who voted for Jackson, and accused the sheriffs and their fellow common councillors of complicity in a plot to defeat “the godly party” in the town. Afterward, Powell continues, “they waited occasions to blast the cittie by all possible meanes.”[69]

Although Powell does not tie the arrival of the Quakers explicitly to the election, in truth they were closely connected. The Quakers first came to Bristol in the spring of 1654; by June they already had won some important converts. Moreover, John Audland and John Camm made one of their initial visits to the city at the time of the poll itself, although for what reason we cannot tell. Many of their early converts appear as parties to the election squabble. George Bishop soon became one of Bristol’s most outspoken Quakers, his tireless pen turning out pamphlet after pamphlet for the cause from 1655 on. Haggatt never went so far, but he was allied through his family with many of Bristol’s first Friends, his wife among them. Their supporters too appear connected to the Quaker movement. A third of them became Friends in the waves of conversion following the visits of Audland, Camm, and other first publishers of Truth.[70] In Powell’s view, the “franticke doctrines” of these Quakers had not only “made…an impression on the minds of the people of this cittie” but also “made such a rent in all societies and relations which, with the publique afront offered to ministers and magistrates, hath caused a devision, I may say a mere antipathy amongst the people, and consequently many broyles.”[71]

As a result, these events ushered in a period of nearly unprecedented dissension within the city. Haggatt and Bishop, using their allies among the Bristol garrison, mounted a concerted attack on the loyalty of the Bristol Common Council. A broad body of their supporters petitioned the Lord Protector to quash the election results, and George Bishop filed information accusing the magistrates of complicity in Royalist plots. By the end of 1654 the effects of the Quaker conversions had become all too apparent to the civic authorities. Individual Quakers began disrupting religious services in the city’s churches and resisting the authority of the aldermen to punish them for their breaches of the peace. At the same time, large public meetings were held, some drawing over one thousand participants. As the movement grew, fear of Quakerism also grew in many quarters. Riots ensued in which bands of apprentices assaulted Quakers on the streets and threatened their public meetings. Moreover, George Cowlishay confirmed the worst suspicions of many Bristolians by spreading a rumor that he had picked up from an Irishman. The Quakers, he charged, really were Franciscan and Jesuit subversives, in England to undermine Protestantism. Many Baptists, their ranks severely depleted by losses to the Quakers, accepted the story as gospel.[72] These developments certainly did not grow only from seeds planted by the expansion of Bristol’s trans-Atlantic trade, nor were they mere reflections of economic divisions within the city. The election and its aftermath hardly reveal the conflict as one simply between the mere merchants and their rivals. Differing views on the constitution and on religious settlement lay at the bottom of the troubles. Nevertheless, the two political factions do show some interesting socioeconomic differences. Although many of Aldworth’s and Jackson’s supporters had interests in the American trade, just like Haggatt’s supporters, the latter consisted much more heavily than the former of men in the lesser crafts and in the shipping industry. Only seven of Haggatt’s votes came from men identified in any way as merchants, and only five from Merchant Venturers. Although both factions in the election found considerable support among soapmakers, grocers, and other major retailers and entrepreneurs, a higher percentage of Aldworth’s and Jackson’s votes came from this quarter. In addition, twenty-six of their backers identified themselves as merchants and the same number were Merchant Venturers, most of them older members of the Society (Table 28).[73] Jackson himself had been a member since at least 1618, and Aldworth, a lawyer by profession, was the son of a Merchant Venturer of the 1620s and 1630s.[74] The impression is strong, therefore, that Aldworth’s and Jack-son’s supporters on the whole came from the richer segments of Bristol’s population and were closely tied to the Merchant Venturers.

| Haggatt | Aldworth and Jackson | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupations | No. | % | No. | % |

| Source: The names of those who supported Aldworth and Jackson are known from H. E. Nott and Elizabeth Ralph, eds., The Deposition Books of Bristol. Vol. 2: 1650–1654 (Bristol Record Society 13, 1948), pp. 181–83. The names of those who supported Haggatt have been established by collating ibid., pp. 180–81, and Public Record Office, SP 18/75/14vi (two slightly different copies of the list drawn by Haggatt’s teller at the 12 July poll) with Public Record Office, SP 18/75/14ii (the petition made to the Protector on Haggatt’s behalf protesting the election). The petition contains ninety-five names, thirty-eight of which do not appear on either of the teller’s tallies. Thirteen of the ninety-five later swore they never signed the petition, but eight of those appear on one or both of the tellers’ lists. A further two are known to have been early Quakers and Baptists. I have counted all thirty-eight among Haggatt’s supporters. It appears likely that they were not counted because they were deemed ineligible. Bishop’s supporters walked out without voting, after protesting against the eligibility of many of their opponents’ supporters. | ||||

| Merchants | 7 | 5.83[a] | 26 | 15.76[a] |

| Major retailers and other leading entrepreneurs | 38 | 31.67 | 76 | 40.06 |

| Lesser crafts and trades | 49 | 40.83 | 39 | 23.64 |

| Shipping | 23 | 19.17 | 18 | 10.91 |

| Gentlemen, professionals | 3 | 2.50 | 6 | 3.64 |

| Total known | 120 | 165 | ||

| Total unknown | 8 | 17 | ||

| Total | 128 | 182 | ||

| Members of the Society of Merchant Venturers | 5 | 4.17 | 26 | 15.76 |

Despite the resistance of conservative-minded Bristolians to the excesses of the colonial traders, these citizens could no longer look backward to the traditions of commercial organization for relief of their grievances, since the Society of Merchant Venturers had long since ceased to protect against the competition of interlopers. Not only did the conditions of colonial trade defeat the techniques of regulation available to the Society, but the Society itself no longer possessed the political power it once had had to control the trading community. The politics of the 1640s had broken its once united leadership and reduced its significance in local affairs. After the parliamentary victory in Bristol in 1645, the new regime in the Corporation and the Society does not seem to have shared the old order’s prejudices against artisan and shopkeeper merchants. Perhaps political allegiances made it difficult even for veteran Merchant Venturers to insist on their exclusion. Between December 1646 and December 1651, seventeen of the thirty-five men admitted to the Society were redemptioners of one sort or another. Some were highly irregular appointments by pre–Civil War standards.[75] Among these redemptioners, we find Thomas Speed, William Bullock, George Bishop, and at least one other sectary, who came to play important roles in the government of the Society in the early 1650s. Speed was one of the Society’s wardens in 1651, and he often served on committees engaged in negotiations with the Rump Parliament or the Council of State. He and Bullock also served on the Court of Assistants, as did Captain Henry Hassard, the fourth sectary and redemptioner. Finally, Bishop used his leverage with the Commonwealth’s officialdom to gain trading privileges for the membership.[76]

However, this was not an era of good feeling in the Society’s history. Although on paper the membership continued to grow, the records of the Merchants’ Hall in the mid-seventeenth century reveal a deep malaise. All through the 1650s and 1660s, considerably less than half of the membership appeared at the quarterly meetings, including the annual election meeting; fewer still turned out for special assemblies. Many of the members stayed away for years on end, prompting the passage in 1652 of a stiff ordinance against all who “wilfully refuse to come to the Hall upon reasonable summons” or who failed to leave proxies when they traveled from town on business.[77] The Society’s finances also appear in disarray. Time and time again the Hall Book says that the payment of fines and of wharfage were seriously in arrears.[78]

The crisis appeared to be one of authority as much as economics. In 1650 the Hall felt obliged to cite its ancient patent from Edward VI, the parliamentary statute of 1566, and Charles I’s charter of 1639 in insisting on the “power and authority not only to make laws and ordinances agreeable to reason for the good of the said Company, But to impose and assess such reasonable paynes, penaltyes and punishments by ffynes and amerciaments for breach of them.” To better collect these fines, the Society adopted the procedure by action of debt, bill, or plaint in the name of the wardens and treasurer before the Mayor’s Court in the Guildhall.[79] Despite this measure, the collections of fines and wharfage remained a continuing problem throughout the 1650s and 1660s.[80]

If the established Merchant Venturers could no longer rely on the Society to achieve their ends, however, they could still use the Common Council to do so. There, as we have seen, they still enjoyed a clear majority of the membership. Moreover, most of the Merchant Venturers on the council had joined before the Civil War, and even before the issuance of the new charter in 1639. Their commercial lives showed a commitment to the principles upon which the Society had stood for so long. The dominance of these men in the city government is clear from the way they handled the election of the first Protectorate Parliament. They controlled the poll both through the sheriffs and through insisting that their voices be heard before the others could vote,[81] and thus they assured victory for candidates who would act in the Society’s interest. Once the members were in Westminster they became spokesmen for this dominant interest, as they had been in the 1620s, using their positions to advance the Merchant Venturers’ claims in such matters as the trade in Welsh butter, and attacking the roots of radicalism in the city as well. According to instructions sent by the magistrates, the MPs were not only to help “establish and settle order in the Church” and to rid the city of the Cromwellian soldiers who had so ardently supported Bishop and Haggatt but were also to address some symptoms of the breakdown in the civic social order arising from the American trade. “The Privildges & liberties of the Citty,” the magistrates complained,

are very much incroached upon to the great discouragement of the Inhabitants, especially young men who thinke it much that they should serve apprentishippe for many yeares; whilst other men that have never served halfe their time & others that were never apprentices at all, are permitted to keepe shope in as free away as themselves.[82]

The common councillors proposed no specific remedy for this last ill, perhaps because it sprang from a number of separate, if interrelated, sources. Most of all, they could no longer urge the principle of monopoly as the solution to their troubles, since even the conservatives of the Protectorate could not be expected to endorse it. However, one of the acts of the Long Parliament, arising from political circumstances similar to those we have found in Bristol in 1654, offered a start toward a cure. In May 1645, the House of Commons received word that Edward Peade, a London merchant, had engaged in child-stealing in the course of his trade. Peade served, along with such radicals as Maurice Thompson, Cornelius Holland, and Owen Rowe, as a commissioner for Somers Islands, and he and Rowe were associated with John Goodwin’s congregation at St. Stephen’s, Coleman Street.[83] During 1645 this intimate connection between the leading London Independents and the Somers Islanders, also noted for their religious zeal, appeared as one theme in London’s “counter-revolution” mounted by the so-called Presbyterians in the capital.[84] The information against Peade only confirmed for these conservatives that Goodwin’s followers were without scruple in all they did. Enemies of London radicalism such as William Spurstow pounced upon the accusation as a means to punish their opponents.

We have no evidence that the parliamentary ordinance of May 1645 or the measures later taken to strengthen it were ever enforced, but they provided the legal authority upon which the Bristol Common Council rested its own registration scheme.[85] With it the common councillors took a first but vital step in regulating the disorder of the colonial trades—a disorder produced largely by the trading activities of their political enemies. The Register worked against those shoemaker merchants and shopkeeping interlopers in various ways. It authorized the water bailiff to board ships in harbor to make inquiry about the indentures of servants and thereby placed the trading activities of all those who used the port under far closer official scrutiny. In this way illicit traders—especially traders who had not paid the entry fees for admission to the freedom of Bristol and had not sworn the freeman’s oath—became somewhat more vulnerable to arrest and to payment of local duties. But the requirement that indentures be used for all servants did something more: it placed the traffic of marginal traders under new economic restraints, which reduced their threat to the established merchant community.

The new registration scheme introduced in Bristol raised the transaction costs associated with conducting the servant trade, since shipping a servant across the Atlantic now required coping with a cumbersome administrative system and with the need to pay for the drawing and registration of the servants’ indentures. Although the charges were small, they had to be paid in coin, as did the fee for admission to the freedom of Bristol. Even for the relatively well-to-do, coin was not always easy to come by. Since most of the servants exported to the colonies in the 1650s were poor men and women seeking subsistence and without money in their purses, it seems clear that these charges would have had to be borne by the servant traders. The trade in servants also operated under certain constraints unusual in other types of commerce. Conditions in the Chesapeake and the West Indies were devastating to newcomers in the seventeenth century. According to some estimates, about 40 percent of those who arrived in these regions died during their terms, many in the first year. The others went through a period of severe “seasoning” during which they were ill for much of the year. As a result, planters usually tried to protect their investment in valuable labor by keeping the new servants free from work during the hot months. Only in the second year, if these newcomers had survived, could the planter expect to get a full year’s work from them.[86] Thus a difference of a year or more in a servant’s term represented a significant difference in his value. As it turns out, servants with indentures had, on average, shorter terms by a year or more than those who came on the custom of the country, since they enjoyed far more leverage to negotiate their terms while in England than after they had crossed the Atlantic. Once the servant had received his payment in the form of passage, he could do nothing but accept the custom as it existed. He had no freedom to return.[87] The use of indentures to regulate the trade therefore had the effect of cutting into its profitability for the trader. In this way it might be thought to bring the evil of “spiriting” under some control, since the poorer traders, those most easily tempted to inveigle or purloin servants to the colonies, were more susceptible than their richer competitors to the disincentives created by the new registration scheme.

For the marginal traders such as the mariners, shopkeepers, and artisans so heavily represented among the sectaries, the forced shift in operation instituted by the registration scheme of 1654 was especially significant, since the price of tobacco and sugar was already in decline in the 1650s. For the large merchants the losses involved would have been easier to absorb, especially because these men could more readily trade in other goods not affected by the same market conditions as servants. Thus the Register sought to accomplish what other economic regulations could not. Since it was no longer possible to exclude marginal traders from the use of ships and the services of factors, it sought to take advantage of the wealth of established merchants to reach the same end. In doing so it conceded an important point. If the larger retailers and manufacturers, such as those we find supporting Aldworth and Jackson in the election, could no longer effectively be barred from overseas trade, at least the Quaker shoemakers might.

| • | • | • |

To cope with the disorder of the colonial trades the Bristol common councillors sought a new market-based discipline in foreign commerce, something that would overcome the apparent anarchy of the sectaries while avoiding the self-defeating rigidities of the old regime. Although in the context of Interregnum politics their action had only limited significance, seen in the light of the history of Bristol’s political economy this new strategy signaled the beginnings of a revolution at least as important as the one it sought to end. It employed political authority to regulate the market so that in turn the market could regulate the distribution of political power. It was a move fraught with possibilities, to which we now turn.

Notes

1. Carus-Wilson, ed., Overseas Trade of Bristol, pp. 65–68, 71–73, 79–81, 87–93, 94–97, 120–22, 125–26, 127–30, 135–37, 139–40, 144, 155–56, 208, 252, 253; Carus-Wilson, Medieval Merchant Venturers, pp. 1, 5, 8, 11, 13, 14, 66, 73, 81, 89, 96, 98–142.

2. BRO, MS 04220 (1–2), which covers 1654 to 1679; further material covering parts of the years 1679–1681 and 1683–1686 can be found in rough form in the records of the Bristol Mayor’s Court: BRO, MSS 04355 (6) and 04356 (1). The entries have now been painstakingly edited by Peter Wilson Coldham, The Bristol Registers of Servants Sent to Foreign Plantations, 1654–1686 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1988). See also William Dogson Bowman, ed., Bristol and America: A Record of the First Settlers in the Colonies of North America, 1654–1685, preface by N. Dermott Harding (London: R. S. Glover, 1931). For discussions of this source, see Mildred Campbell, “Social Origins of Some Early Americans,” in James Morton Smith, ed., Seventeenth-Century America: Essays in Colonial History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), pp. 63–89; Richard S. Dunn, Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624–1713 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), pp. 70–71; James Horn, “Servant Emigration to the Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century,” in Thad W. Tate and David L. Ammerman, eds., The Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), pp. 51–95; Salerno, “Social Background of Seventeenth-Century Emigration,” pp. 31–52; David Souden, “Rogues, Whores and Vagabonds? Indentured Servant Migration to North America and the Case of Mid-Seventeenth-Century Bristol,” Social History 3 (1978): 23–39; David W. Galenson, “ ‘Middling People’ or ‘Common Sort’? The Social Origins of Some Early Americans Reexamined,” with a rebuttal by Mildred Campbell, WMQ, 3d ser., 35 (1978): 499–540; David W. Galenson, “The Social Origins of Early Americans: Rejoinder…with a Reply by Mildred Campbell,” WMQ, 3d ser., 36 (1979): 264–86; David W. Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), esp. pp. 34–39, 183–84

3. BRO, Common Council Proceedings, vol. 5, p. 72. David Galenson prints the document in Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America, pp. 189–90.

4. Latimer, Annals, pp. 254–55; Abbott Emerson Smith, Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America, 1607–1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947), p. 71; MacInnes, Gateway of Empire, p. 161; Dunn, Sugar and Slaves, p. 70; Horn, “Servant Emigration to the Chesapeake,” p. 55n. 17; Souden, “Rogues, Whores and Vagabonds?” pp. 25–26; Galenson, “ ‘Middling People’ or ‘Common Sort’?” pp. 504–5, repeated verbatim in White Servitude in Colonial America, pp. 37–38, and see p. 183

5. The relevant documents are in H. E. Nott and Elizabeth Ralph, eds., The Deposition Books of Bristol. Volume 2: 1650–1654 (BRS 13, 1947), pp. 166–67, 174–75, 192. Meredith had been apprenticed on 7 March 1653, for nine years, to Anthony Barnes, baker, and his wife Anne. Meredith is identified in the apprenticeship indenture as the son of a deceased gentleman of Landovery, Carmarthenshire: BRO, MS 04352 (6), f. 279v. The nine-year term suggests that Meredith may have been as young as twelve when his apprenticeship indenture was drawn. The sailors aboard the Dolphin, however, identify him as “a Young man as they conceive aboute the age of 18 yeares”: Nott and Ralph, eds., Deposition Books, vol. 2, p. 174. But they had good reason to shade the truth in their favor. Nevertheless, their story clearly has a modicum of truth to it. Meredith looks like the runaway young son of a Welsh gentleman apprenticed in Bristol after his father’s death. For doubts about the veracity of the sailors’ deposition, see McGrath, “Merchant Shipping in the Seventeenth Century,” 41 (1955): 29–30.

6. See, e.g., William Bullock, Virginia Impartially Examined (London, 1649), p. 14; Smith, Colonists in Bondage, pp. 67–69. The Middlesex County Records abound with references: see John Cordy Jeaffreson, ed., Middlesex County Records, old ser. (1886–1892), vols. 3–4, esp. vol. 4, pp. xli–xlvii.

7. See, e.g., BRO, MS 04417 (1), f. 47v; Latimer, Annals, pp. 254–55.

8. BRO, Common Council Proceedings, vol. 5, p. 72.

9. For some comments to the contrary, see Galenson, “ ‘Middling People’ or ‘Common Sort’?” p. 505; Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America, p. 38

10. See Gylbert v. Fletcher (4 Car. I Trin.), Cro. Car. 179, in English Reports 69, p. 757 and the cases cited there. There is no doubt that indentured servants were treated administratively exactly like apprentices. Servants’ covenants and apprentices’ indentures were recorded in the same rough entry books of the Mayor’s Court: see BRO, MSS 04354, 04355 (1–6), 04356 (1); Bowman, ed., Bristol and America, pp. viii–ix; Elizabeth Ralph, Guide to the Bristol Archives Office (Bristol: Bristol Corporation, 1971), p. 52; Galenson, “ ‘Middling People’ or ‘Common Sort’?” p. 515; Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America, p. 183. Indeed, the second volume of the Register is officially entitled “The Inrollment of Apprentices and Servants as are shipped at the port of Bristoll to serue in any of the forraigne plantations”: BRO, MS 04220 (2), f. 1r. The earliest known indenture for service in the plantations, dated 4 December 1626, is to be found in an ordinary apprentice book: BRO, MS 04352 (5)a, f. 23r; see MacInnes, Gateway of Empire, pp. 151, 158.

11. See 1 Sid. 446, in English Reports, vol. 82, pp. 1208–9; Joseph Chitty, A Practical Treatise on the Law Relative to Apprentices and Journeymen and to Exercising Trades (London: W. Clarke and Sons, 1812), pp. 29–31; Henry Evans Austin, The Law Relating to Apprentices, Including those Bound according to the Custom of London (London: Reeves and Turner, 1890), pp. 18–19. By the 1620s all indentures involving men, even those for parish apprentices placed by the churchwardens, are made only in the names of the apprentice and the master. For early sixteenth-century practice see Hollis, ed., Bristol Apprentice Book, part 1, p. 14; for the standard in the seventeenth century, see BRO, MS 04352 (5)a.

12. Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, or a Commentary upon Littleton (London, 1620), p. 172a.

13. Bristol, which from very early on kept a summary of the constitutions of London as part of its precedent books, may have followed the rules of London, where the contracts of apprentices over fourteen years of age were deemed those of an adult and those under fourteen were subject to the common law as stated by Coke: see Bohun, Privilegia Londini, pp. 175–78, 338; Ricart, Kalendar, pp. 102–3.

14. Cro. Car. 179 in English Reports, vol. 69, p. 757; see the astute remarks of Fry L. J. in Walter v. Everard, 2 Q.B. (1881), 376. See also Staunton’s Case (K.B. 25 Eliz. I), Moore, 135–36 in English Reports, vol. 72, pp. 489–90; Walker v. Nicholason (K.B. 41 Eliz. I, Hil. 12), Cro. Eliz. 653 in English Reports, vol. 68, p. 892.

15. For the Privy Council’s attempt to do just this in 1682, see PRO, PC 2/69/595–96, printed in Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America, pp. 190–92.

16. BRO, MS 04220 (1), f. 351r.

17. See, e.g., ibid., f. 43r and the entry for 20 July 1659 on an unnumbered page at the end of the volume; the Statute of Artificers, Stat. 5 Eliz. I c. 4, required only that indentures be enrolled within a year of being drawn.

18. BRO, MSS 04220 (1), ff. 351r–352r, 355v–367v, 482r–497v, 04220 (2), ff. 187r–231v, 271v, 278r– d of volume.

19. BRO, MS 04220 (2), f. 196r. In this case the child was apprenticed to eleven years in Montserrat, which suggests that he was below the age of fourteen—probably about ten—at the time of the indenture.

20. BRO, MS 04220 (1), entry for 20 July 1659 at the end of the volume.

21. See above, pp. 247–48; Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, pp. 139–40. A suit could proceed even though the party was out of town or had concealed his goods.

22. BRO, Common Council Proceedings, vol. 5, p. 73.

23. See Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, chap. 3.

24. Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, pp. 104–21. According to the Wharfage Book, Hiscox brought five hogsheads and five butts of Barbados sugar aboard the Dolphin on 5 May 1654. Clearly he had exported more than just Farwell Meredith. Mary Hiscox, perhaps his wife, had an additional four hogsheads in her name aboard the Thomas and George on 11 August of the same year.

25. Souden, “Rogues, Whores and Vagabonds?” pp. 34–35; Horn, “Servant Emigration to the Chesapeake,” pp. 87–89. Horn’s figures exaggerate the number of “merchants,” for many of those who identified themselves as members of this occupation appear to have apprenticed as coopers, mariners, mercers, soapboilers, and the like. By cross-checking the names in the Register with other Bristol sources, I calculate that only about 15 percent of the traders in servants for whom occupations are known were “merchants” by apprenticeship or patrimony, and even this figure may somewhat exaggerate the total.

26. For planters like John George, Farwell Meredith’s colonial master, the produce of their own estates—sugar, tobacco, indigo—served in place of money. See, e.g., Nott and Ralph, eds., Deposition Books, vol. 2, p. 115; BRO, MSS 04439 (3), f. 188r, 04439 (4), f. 89r; McGrath, ed., Merchants and Merchandise, pp. 242–43, 246, 255. Virginia, in fact, lacked hard currency of any sort, but instead its economy operated with an elaborate system of tobacco equivalencies: Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), p. 177; Gloria L. Main, Tobacco Colony: Life in Early Maryland, 1650–1720 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), p. 50.

27. Bullock, Virginia Impartially Examined, pp. 12–14, 46–47.

28. The Bristol wharfage duty fell on a variety of luxury imports, among which were sugar, tobacco, indigo, ginger, cotton, and other colonial products. The Society of Merchant Venturers’ earliest surviving Wharfage Book, modeled on the Exchequer’s own Port Books, begins in mid-May 1654. Much like the Register of Servants, greater care in keeping the records seems to have been taken in the mid-1650s than later. By 1662 the recording clerks no longer always took pains to distinguish entries vessel by vessel, which makes the books extremely difficult to use.

29. Of the unknowns, many undoubtedly were planters shipping goods in their own names to the English market, but a few might have been Bristolians like Marlin Hiscox who never became freemen. For further evidence of shopkeepers and craftsmen engaged in colonial commerce see BRO, MSS 04439 (3), ff. 10r–v, 40v–41r, 57r, 66v, 102v, 126r–v, 131v, 193v–94r, 04439 (4), ff. 15v, 55r.

30. To avoid confusion caused by ships that stopped several places in the colonies before returning to England, in Table 26 any import of colonial goods by an individual is counted as a return for the export of any servant, no matter what the servant’s original destination.

31. Souden, “Rogues, Whores and Vagabonds?” p. 35.

32. On Blike’s efforts on behalf of Tocknell, see BRO, MS 04439 (3), ff. 86r–89r.