Finally, two ecclesiastical enclaves existed within the city: the liberty of the Augustinian Abbey in the parish of St. Augustine to the west, and the franchise of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, known as Temple Fee, in the parish of Temple to the south. The holders of both claimed for themselves wide immunity from the jurisdiction of Bristol’s government in such matters as payment of local tolls and taxes and freedom from suit in court; in addition, fugitive criminals, including murderers and men outlawed in civil cases, could claim sanctuary within the boundaries of each liberty.[22] These facts directly affect our story. When Ricart wrote, St. Clement’s Chapel was located at the Hospital of St. Batholomew in the College Green, within the enclave of St. Augustine’s Abbey. St. Katherine’s Chapel was located in Temple Church itself, and the weavers’ gildhall, also dedicated to St. Katherine, stood nearby in St. Thomas Street; both were situated in the heart of Temple Fee.[23]

Although mariners or merchants might seem from our modern viewpoint to have little in common with weavers, from the perspective of the late medieval urban polity they shared several important characteristics. In Bristol, the community of freemen was by definition a community of retailers.[24] But in the later Middle Ages, mariners and overseas merchants depended more on distant markets than on the local one, and many of them traded principally by wholesale, not retail. Their actions in the community, then, were not readily controlled by official disenfranchisement or discommoning, which merely deprived them of their right to trade legally by retail at a shop or market stall. A similar difficulty arose with the weavers, since they too depended for their economic activities primarily on markets outside the city proper. By the fourteenth century, as we know, Bristol was one of England’s leading cloth exporters, and every year thousands of fabrics made their way to the continent in return for such goods as wine and woad. In a very real sense, the whole life of the city centered on this trade. It not only supplied the necessary infusions of wealth to keep the city running but set a rhythm to city life, as wool gathered in the spring shearings was turned into cloth to ship in time to purchase French wine from the autumn harvest. This process reached its climax toward the end of November, as the great cloth fleet sailed for Bordeaux,[25] and the festive days of St. Clement and St. Katherine came at just the right moment in the year to bless the major events in the city’s annual economic cycle.

In popular celebration, St. Clement’s Day and St. Katherine’s were often treated as an interrelated pair. In many places, the former was a special day for boys and the latter for girls. In some, the two feasts were collapsed into one and celebrated on the same day.[26] For late medieval Bristol, the pairing seems focused especially on the structural tensions that characterized the community—those arising from the geographical divisions in the city, from the existence of large jurisdictional enclaves within its borders, and from the important but peculiar place of weavers and overseas traders in the social order.

Unfortunately, we know very little about how the city celebrated St. Clement’s Day. From Ricart’s Kalendar we can see that there was at least one procession, occurring on St. Clement’s Eve, in which the members of the Bristol Corporation, almost certainly coming from the Guildhall in the city center, crossed the river Frome into the heart of the sanctuary of St. Augustine’s Abbey. The following day, a mass with communion was celebrated.[27] The celebration, with its crossing of the boundaries and its taking of the sacrament, seems very much a ceremony of unification.

A similar pattern is to be observed in the Feast of St. Katherine, about which Ricart tells us somewhat more. The celebration divides into three parts, typical of rites of passage as they have been described and analyzed by Arnold van Gennep and Victor Turner.[28] It began with a procession to evensong at Temple Church, passed through a long transition, and ended with a second procession and a mass.[29] To understand this sequence of events we need to study each of these stages in turn. In doing so, we can not only examine the particular significance of St. Katherine’s Day but perhaps also see something of the significance of St. Clement’s Feast as well.

Processions were a commonplace of urban life in the Middle Ages, and the members of the Bristol city government attended many public functions in this fashion, each man in his scarlet robe walking in the place appropriate to his rank and seniority.[30] In general, these processions had a double social meaning. Most obviously, they expressed in visible form the organization of the municipal government; the persons holding each of the principal offices were publicly advertised. Not only were observers made aware of the hierarchy of power within the city, they were reminded through this symbolic expression of political authority of their own proper position in the community and of the need to show deference to its leaders.[31] But in this particular case, the procession stood for something more. The presence of the magistrates in full regalia in the church asserted the legitimacy of their authority in a place where ordinarily they could not exercise control. Although technically they had power over the Bristol freemen—most of them weavers and other clothworkers—who lived within Temple Fee, they could not enforce that power directly should they meet resistance there. The procession, then, raised the problem of Temple Fee’s anomalous jurisdictional status and introduced in a dramatic way the theme of its underlying unity with the civic community as a whole. The same can be said for the procession on St. Clement’s Eve, two days earlier, to the College Green.

The transition stage of St. Katherine’s festivities shifts our attention from the status of Temple Fee to the relationship between the weavers’ gild and the municipal authorities, and from St. Katherine’s Chapel to St. Katherine’s Hall, where there were “drynkyngs” of “sondry wynes” and where “Spysid Cakebrede” was eaten by the assembled celebrants. At the Hall the mayor and his brethren became the guests of the weavers, which gave the latter the opportunity to display their wealth and manifest their importance.[32] Moreover, Ricart says, “the cuppes” were “merelly filled aboute the hous,” which signifies the drinking of “healths” among the participants; it is with the same or similar phrases that this time-honored social ritual is often identified in the late medieval and early modern period. By its nature this is a reciprocal process; healths are not merely given but exchanged. In this way the weavers secured the “amity and affection” of the city’s political leadership and, if need be, forgiveness for any wrongs. In the drinking of healths and the eating of spiced cake the sharply delineated hierarchy apparent in the processional breaks down, most probably in a degree of inebriation, a kind of licensed drunkenness. Drunkenness is the opposite of order. It wreaks havoc on both body and mind, and, as was commonly said, “nothing can be found stedfast” in it.[33]

Suitably inebriated after thus passing the cups, the membership of the city government found their way “euery man home” alone.[34] What had started as an ordered procession into Temple Fee now became a leaderless and unorganized—a disordered—movement away from it. Viewed in this fashion, the transition stage of the festival seems devoted primarily to the ceremonial stripping away of the hierarchical structure and pretensions of Bristol’s leadership.[35] This effect was only reinforced as events moved further into the night. When they reached home, the mayor, sheriff, bailiffs, and other worshipful men received “at theire dores Seynt Kateryns players, making them to drynk at their does, and rewardyng theym for theire playes.”[36] Unfortunately, Ricart tells us nothing about the nature of these plays or about the social makeup of the group of wandering performers. But we know enough to draw some tentative conclusions.

By tradition, St. Katherine was a special guardian of the Christian community against evil secular authority. The essential elements of her life concern her challenge and ultimate defeat of the emperor Maxentius, a cruel persecutor of Christians. In the end, her righteous authority triumphed over Maxentius’s injustice, fulfilling her prophecy that if he failed to correct his ways he would “be a servant.” In local festivities on her day, the figure of St. Katherine usually appeared with her assistants—sometimes children or, more commonly, lesser members of some gild—to demand tribute from the leading citizens, usually the civic authorities. The event was one of ritual submission which gave social inferiors an opportunity to exact symbolic homage from their betters. The treats they received from the leading men gave recognition that these notables were part of the same community as the players; they were a kind of toll or entry fee. By giving them, the city’s governors subordinated themselves symbolically to Katherine’s divinely inspired authority and, therefore, not only to the virtues she exemplified but to the community she represented.[37]

If this interpretation is correct, it leads us by a natural progression to the final stage of St. Katherine’s rite in Bristol: the unification of Temple Fee and its weavers with the borough community as a whole. Once again the event centers on a procession, but now the Corporation members, purged or purified by the proceedings of the previous night, join the parishioners of Temple to make a circuit of the town, ritually integrating the population of Temple Fee into the borough community. This union is sealed with a mass and offering, which combined, as John Bossy has emphasized, the principles of order and unity within social divisions. In their solemn communion, with its focus on the Kiss of Peace, the members of the Corporation were finally joined together with their fellow citizens from the parish of Temple, each in his legitimate place as members of the larger Christian commonwealth.[38] Again a similar point can be made about the celebration of St. Clement’s Day at College Green.

In this way the Feast of St. Katherine together with its companion Feast of St. Clement confirmed the principle of unity proclaimed by the late medieval borough community. According to theory, a saint was the representative in heaven of a community, ready to intercede for its members individually and collectively, so the community gained in solidarity from its veneration of his or her image or relics. In other words, a spiritual bond, mediated through sacred objects, tied together life in this world with life in the next and made the social body also a holy one, the symbol of godly order and harmony. The community represented by a saint necessarily was a microcosm of the world. It marked off within its boundaries a series of structured relationships that distinguished it from other communities and made it unique at the same time as it replicated the divine order.[39] The result in Bristol of celebrating such a saint’s day was a territorial unity that defined the boundaries of the community; a jurisdictional unity that linked its members together in a set of common rights and privileges; and a social, or even spiritual, unity that was the ideal of their common enterprise. Tension, dissent, and conflict there might well be, but not without resolution, at least in theory. These two festivals recognized the fact of territorial, jurisdictional, and social cohesion within the divided city and reaffirmed its ideals of harmony, uniformity, and solidarity.

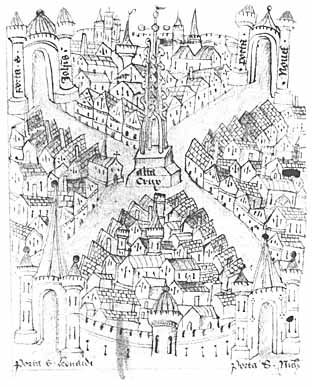

The borough community of the high Middle Ages in theory was a bounded world, a communion of interests and purposes separating the townsmen and their life of trade from the agrarian existence of the rest of England. The feasts of St. Clement and St. Katherine confirmed these ideals of community in the face of social and economic tensions that by 1400 had begun to threaten their foundations. In symbolic form they integrated the weavers and mariners into the body politic of the city. Robert Ricart, in his map of the city at its foundation, also conveyed this vision of Bristol as an emblem of the cosmos (Figure 4).[40] This map, in which Bristol sits upon a little hill between four gates, portrays a nearly perfect example of what Werner Müller has identified as the Gothic town plan. It is a city built as “the navel of the world,” a cross within a circle, representing the heavenly Jerusalem, in which the four main streets divide the world into its four component parts.[41] It puts into visible form, then, the ordered community which found its highest expression on Corpus Christi, when the civic body, the crafts, and the other citizens proceeded through the town, each in his proper place, in veneration of the host.[42]

Fig. 4. Robert Ricart’s Plan of Bristol at Its Foundation. (Robert Ricart, The Maire of Bristowe Is Kalendar, Bristol Record Office, MS 04720 (1), f. 5. By permission of the City of Bristol Record Office.)

In general, all of Bristol’s late medieval festive life encouraged its citizens to conceive of their city in this way, as a microcosm embedded in the larger order of God’s universe. It also yielded a subtle commentary on the nature and distribution of political authority. In ritual and festival the civic community appeared as a bounded world of reciprocal relations—of harmonies and correspondences—not of absolutes. For, taken together, events like the celebration of the feasts of St. Clement and St. Katherine emphasized the social limitations on authority, not the sovereignty of those who exercised it. They focused on the membership of the mayor and his brethren in the commonalty of burgesses and freemen, and on the need for communal acceptance of their earthly rule.