2. In a Worshipful State, 1450–1650

4. The Navel of the World

The concept of social organization concerns the ways that human beings adjust means to ends in their collective lives. For sociologists and political scientists, this focus usually yields an analysis of self-perpetuating social institutions and bureaucratic systems in which each element supports the others as part of a larger mechanism. For historians, it commonly involves tracing in narrative the reasons why individuals and groups acted as they did. Either way, however, students of social organization generally consider the significance of an action to lie in its use rather than in its place in an already existing web of symbols and values. Our approach in the previous section, mixing the methods of the social scientist with the interests of the historian, followed this line of interpretation. It told the story of how Bristol’s overseas merchants built a new social order for themselves in response to the economic conditions confronting them after 1453. But these Bristolians also lived in a world of well-established cultural codes and social meanings with which they were obliged to come to terms in remaking their society. To move beyond the limited notion of functionalism and the narrow idea of rationality upon which we have so far relied, we now need to examine this social and political language and the changes it underwent.

In 1577 John Northbrooke, “preacher of the Word of God” at Bristol, published one of England’s earliest condemnations of stage plays, interludes, “jugglings and false sleyghts,” and other pastimes. Our duty, he says, requires us to “apply al and euery of our doings to ye glory of God,” but instead “we kepe ioly cheare one with another in banquetting, surfeiting and dronkennesse; also we vse all the night long in ranging from town to town, and from house to house, with mummeries and maskes, diceplaying, carding and dauncing.” Thus, “we leaue Christ alone at the aultar, and feed our eyes with vaine and vnhonest sights.” Festival and holy days contribute to this spirit of dissipation, for by them “halfe the yeare, and more,” is “ouerpassed…in loytering and vaine pastimes…restrayning men from their handy labours and occupations.”[1]

Northbrooke’s views represent a fundamental rejection of the cultural traditions that dominated English life until the sixteenth century. Nowhere had these traditions been better exemplified than in the town in which Northbrooke served his ministry. For example, on Corpus Christi in early sixteenth-century Bristol, we are told,

And on Midsummer Eve, these same gildsmen “—who emulated each other in the display of gay dresses, banners, burning ‘cressets’ and torches, and in the supply of minstrels and musical instruments—marched through the streets, the proceedings terminating in morris dancing and various games, in which the populace participated.”[3] These celebrations, along with others in Advent and at Christmas, played an important part in the official civic calendar. The mayor and his brethren of the Common Council, far from being God’s ministers in punishing “dicers, mummers, ydellers, dronkerds, swearers, roges and dauncers,” as Northbrooke would have had them be,[4] participated in and even led most of the festivities. In the later fifteenth century, Robert Ricart, Bristol’s town clerk and lay brother of its Fraternity of Kalendars, exhorting his readers in nearly as hearty a manner as Northbrooke, set forth these “laudable” customs in a book of remembrance so that the city’s officers “may the better, sewrer, and more diligenter, execute, obserue, and minstre their seid Offices…to the honoure and comon wele of this worshipfull towne, and all thenhabitaunts of the same.”[5] Where Northbrooke saw the activities of “idle players and dauncers” leading only to their city’s moral downfall,[6] Ricart, writing a hundred years before, saw these same practices as intimately connected with Bristol’s welfare.[t]he members of every guild…assembled with music, flags and banners to join in a splendid ecclesiastical procession through the streets, where the houses were decorated with tapestry, brilliant cloth, and garlands of flowers and the afternoon was spent in the performance in the open air of miracle plays, in which every craft claimed its special part, to the enjoyment of the whole community.[2]

Curiously, many of the celebrations that Ricart praised and Northbrooke damned were already something of a dead letter in England by the 1570s. I do not mean, of course, that Christmas feasting and Shrove Tuesday cock-throwing were no more, or that church ales and Sabbath-day sports did not persist. But the great public celebrations led by the civic leaders of the towns, paid for out of the funds of the town treasuries, had largely ceased. Most had been stricken from the liturgical calendar in Henry VIII’s reign,[7] and although there had been an effort under Queen Mary to revive them, they never recovered their old vitality and had long been in abeyance when Northbrooke took up arms against dicing, dancing, and vain plays. Despite some massive demonstrations of nostalgia, their end had been peaceful. There was no St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre in their defense. They had passed on not in fire but in ice.[8] This chapter attempts an explanation for their seemingly peaceable demise.

By choosing to examine this subject, however, we set forth into perhaps the most troubled waters of historical interpretation. It is not that the field has suffered from bitter debates, with scholars striking each other hip and thigh after the fashion of the Hebrews and Amalikites; there has been no “Storm over the Ceremonies.” Rather, the methodological and theoretical issues raised by the study of festival and ritual have produced so little consensus that many historians refuse to accept the subject as history; they see no way that it can be studied according to the canons of historical inquiry and reject it as a form of misplaced sociologizing or literary criticism gone astray. Past rituals, it is widely believed, had meanings for their participants that at this distance we cannot penetrate; hence all we can do is to reduce them in some sterile and arbitrary way to epiphenomena of the social order according to some Marxist theory of base and superstructure or some Durkheimian scheme of functionalism.[9] But the problem of understanding ritualistic action is not unique to students of lost religions. Historians of every type face it whether they are studying diplomatic negotiations, election stump oratory, or factory life. Interpreting ritual means making intelligible highly formalized actions that manifestly are intelligible to the actors themselves, and as such it is a problem of human understanding not confined only to one branch of history or, indeed, to historical study alone. It is a problem of everyday life.

A simple analogy drawn from one of Roger Edgeworth’s sermons may help to convey what I mean. In speaking of correct behavior, Edgeworth says:

Why should singing in these circumstances amount to an offense? Nothing would be amiss if this same man sang a psalm in church or a tune in the alehouse: such behavior would be appropriate to the setting and thereby conform, in Edgeworth’s sense, to the Aristotelian mean. The answer lies in the relationship between meaning and context. The market and the law court are places intended for the conduct of particular kinds of business, solemnly undertaken. Those engaged in them are governed by tacitly accepted rules of conduct which not only dictate their behavior but make it understandable to their fellows. When in the marketplace, it is proper to cry out one’s wares and to bargain. Both situations dictate highly ritualized patterns, not amenable to hymn-singing or balladeering. In bargaining, for example, there are accepted procedures of offer and counteroffer the use of which helps the parties to come to agreement upon a price. Each side employs the common language of haggling to signal his wishes and to discover his opposite’s intentions. Each side tries to read the other’s situation in his offers and adjusts his actions accordingly. Should one of the bargainers break into song in the midst of such a negotiation, his tune would seem the raving of a madman, because it would defeat the common purpose of the exchange. Similarly, in a law court it is proper to make motions and to give arguments in the specialized language of the law. A lawyer who sings his pleas would be judged—quite rightly—as deranged. There would be no conventions against which to weigh his songs, and his actions would become unintelligible. In other words, it is by properly understanding the context in which we find ourselves and adjusting our behavior to it that we begin to make our meanings known and grasp the meanings of others.[I]f a man woulde syng in the middle of the market, or in a court at the barre afore the iudge when ther be weighty matter in hand, he should offend against modestie, & against al good humanitie, so that he may be called modest or manerly that in al his behaviour vseth good maner and measure, and a mean.[10]

We could hardly proceed in our lives if our social actions were not amenable in this way to interpretation by others. But to understand social action requires an understanding of the social setting in which the action takes place. This raises two important points, one regarding the way the action is viewed by outside observers and the other the way it is seen by the actors themselves. For the outsider, discovering the rules of intelligibility shared by those he observes demands an understanding not only of their gestures but of their frame of reference as well. This task, as has been pointed out by many theorists, is somewhat like translating from one language to another, a difficult enterprise when there are large differences between cultures. To do it effectively requires attention not only to grammar, syntax, and logical connections but to what is sometimes called the speaker’s “form of life.” As Hilary Putnam puts it, comprehension of the words or behavior of a stranger begins with assumptions about what he “wants or intends” and is relative to “the nature of the environment” in which he speaks or acts. In Putnam’s terms it is “interest-relative,” a concept he illustrates with the following example. “Willie Sutton (the famous bank robber),” he tells us, “is supposed to have been asked ‘Why do you rob banks?,’ to which Sutton gave the famous reply: ‘That’s where the money is.’ Now…imagine,” Putnam says,

In interpreting language and other forms of social action, we need to know what issue is being raised in order to understand the response, and this means understanding the context—the environment—in which the actors find themselves. Is it a confessional, or a den of thieves?(a) a priest asked the question; (b) a robber asked the question.…The priest’s question means: “Why do you rob banks—as opposed to not robbing at all?” The robber’s question means: “Why do you rob banks—as opposed to, say, gas stations?” And Sutton’s answer is an answer to the robber’s question, but not the priest’s.[11]

When the social setting in which we live is changing rapidly, it is possible that some of us will move in a context that differs in significant ways from everyone else’s, and that as a result the same social behavior will be open to systematically different interpretations—in which one party, as it were, asks the priest’s question and the other answers the robber’s. In extreme circumstances, moreover, a traditional form of social behavior can completely lose its intelligibility if the social setting in which it previously made sense is sufficiently transformed. By ceasing to have social relevance, it ceases to be acceptable or useful behavior and fades from view. In a den of thieves the priest’s question is rarely in order.

This way of thinking about ritual and social change establishes the conditions under which the meaning of social action can be determined. It tells us that the performers and their audience belong to the same community of discourse. But this does not imply that all participants in this community will necessarily agree on every interpretation of meaning. Confusion, misunderstanding, disagreement, and conflict about troubling issues can be as much a part of community life as harmony and agreement. This approach neither reduces meaning to the way ritual symbolizes or expresses the social order nor subsumes meaning into social function. Instead, it views meaning and context in relation to one another without conflating the two. Let us see whether this formulation can aid us in understanding the strange death of civic ceremony in Reformation Bristol.

In the early Middle Ages, when Bristol’s Gild Merchant was transforming the borough into an effective corporate body, the principal line of tension in the city was between its sworn brotherhood of freemen and all non-freemen, that is, between those who enjoyed the liberty to trade freely by retail within the borough and those, whether inhabitant or stranger, who did not. Until the fourteenth century the freemen had a certain unity, despite differences in wealth and power among them, because they had to define themselves against dangers that came to the borough from outside, including threats from the Crown to Bristol’s political independence.[12] By the later fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, however, the fabric of social life had begun to alter, as various stages of cloth production migrated into the countryside, as the trade in woolens looked more and more to foreign markets, as a class of merchant entrepreneurs differentiated themselves from the other members of the old mercantile community, and as local governance fell into the hands of the borough’s “better and more worthy men” serving on a select council. Moreover, after Bristol had achieved a form of incorporation in 1373, relations between freemen and non-freemen became somewhat less problematic, and the principal focus of the city’s political life turned from protecting the independence of the borough to regulating relations among the freemen.[13] In this era, more than before, the burgesses of Bristol lived according to the ideals of social unity but the realities of social division.[14] They bound themselves in a compact body by oaths promising complete devotion to the city’s commonweal and thorough commitment of their wealth and power to its aid.[15] Yet they resided in a town whose topography segregated them into distinct neighborhoods and whose economy placed them in separate social groupings.

The celebrations of the Feast of St. Clement, patron of the mariners and merchants,[16] on 23 November, and of the Feast of St. Katherine of Alexandria, patroness of the weavers, two days later, were very much a product of this later period. Although there was a chapel dedicated to St. Katherine in Temple Church from 1299, and a gild of weavers from at least the 1340s—and probably a good deal earlier—the grant of the first indulgences to the gild for its chapel dates only from 1384, and the chapel itself became a permanent chantry only in 1392. It is in this same period, that is, the middle and late fourteenth century, that the city acquired its Common Council.[17] Thus it is unlikely that St. Katherine’s Day could have received an elaborate official celebration— gaging both the gild and the civic leadership—before the mid-fourteenth century. About St. Clement’s Day we can be somewhat more definite. The chapel and gild associated with him were founded only in 1445 or 1446.[18] Hence to grasp the significance of this pair of feast days, we must begin with the peculiarities of late medieval Bristol.

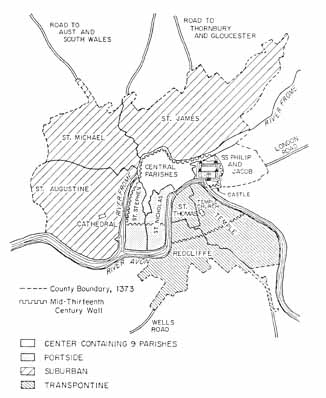

Bristol was first and foremost a river port, located at the confluence of the Avon and the Frome, which, in the words of John Leland, “dothe peninsulate the towne.”[19] In consequence, the urban territory in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was divided into three separate segments. In the center, between the two rivers, there were eight small and three large parishes, all completely built up. To the east and south of the Avon, across the bridge that had given Bristol its name, lay three relatively large and also well-inhabited parishes. By the fifteenth century, Bristol also extended to the west and north in an arc of important suburbs beyond its old medieval walls (Figure 3).[20] Jurisdictional considerations further increased this complexity. Until 1373 the river Avon divided the city legally, politically, and administratively, as well as geographically. On its western and northern bank, it lay in the county of Gloucester; on its eastern and southern bank, it lay in Somerset.[21] Moreover, even after Bristol became a county in its own right in 1373, it still stood in two different dioceses, with the fifteen parishes west and north of the Avon subject to the bishop of Worcester and the three parishes to its east and south under the authority of the bishop of Bath and Wells.

Fig. 3. Bristol’s Ecclesiastical Geography, ca. 1500.

Finally, two ecclesiastical enclaves existed within the city: the liberty of the Augustinian Abbey in the parish of St. Augustine to the west, and the franchise of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, known as Temple Fee, in the parish of Temple to the south. The holders of both claimed for themselves wide immunity from the jurisdiction of Bristol’s government in such matters as payment of local tolls and taxes and freedom from suit in court; in addition, fugitive criminals, including murderers and men outlawed in civil cases, could claim sanctuary within the boundaries of each liberty.[22] These facts directly affect our story. When Ricart wrote, St. Clement’s Chapel was located at the Hospital of St. Batholomew in the College Green, within the enclave of St. Augustine’s Abbey. St. Katherine’s Chapel was located in Temple Church itself, and the weavers’ gildhall, also dedicated to St. Katherine, stood nearby in St. Thomas Street; both were situated in the heart of Temple Fee.[23]

Although mariners or merchants might seem from our modern viewpoint to have little in common with weavers, from the perspective of the late medieval urban polity they shared several important characteristics. In Bristol, the community of freemen was by definition a community of retailers.[24] But in the later Middle Ages, mariners and overseas merchants depended more on distant markets than on the local one, and many of them traded principally by wholesale, not retail. Their actions in the community, then, were not readily controlled by official disenfranchisement or discommoning, which merely deprived them of their right to trade legally by retail at a shop or market stall. A similar difficulty arose with the weavers, since they too depended for their economic activities primarily on markets outside the city proper. By the fourteenth century, as we know, Bristol was one of England’s leading cloth exporters, and every year thousands of fabrics made their way to the continent in return for such goods as wine and woad. In a very real sense, the whole life of the city centered on this trade. It not only supplied the necessary infusions of wealth to keep the city running but set a rhythm to city life, as wool gathered in the spring shearings was turned into cloth to ship in time to purchase French wine from the autumn harvest. This process reached its climax toward the end of November, as the great cloth fleet sailed for Bordeaux,[25] and the festive days of St. Clement and St. Katherine came at just the right moment in the year to bless the major events in the city’s annual economic cycle.

In popular celebration, St. Clement’s Day and St. Katherine’s were often treated as an interrelated pair. In many places, the former was a special day for boys and the latter for girls. In some, the two feasts were collapsed into one and celebrated on the same day.[26] For late medieval Bristol, the pairing seems focused especially on the structural tensions that characterized the community—those arising from the geographical divisions in the city, from the existence of large jurisdictional enclaves within its borders, and from the important but peculiar place of weavers and overseas traders in the social order.

Unfortunately, we know very little about how the city celebrated St. Clement’s Day. From Ricart’s Kalendar we can see that there was at least one procession, occurring on St. Clement’s Eve, in which the members of the Bristol Corporation, almost certainly coming from the Guildhall in the city center, crossed the river Frome into the heart of the sanctuary of St. Augustine’s Abbey. The following day, a mass with communion was celebrated.[27] The celebration, with its crossing of the boundaries and its taking of the sacrament, seems very much a ceremony of unification.

A similar pattern is to be observed in the Feast of St. Katherine, about which Ricart tells us somewhat more. The celebration divides into three parts, typical of rites of passage as they have been described and analyzed by Arnold van Gennep and Victor Turner.[28] It began with a procession to evensong at Temple Church, passed through a long transition, and ended with a second procession and a mass.[29] To understand this sequence of events we need to study each of these stages in turn. In doing so, we can not only examine the particular significance of St. Katherine’s Day but perhaps also see something of the significance of St. Clement’s Feast as well.

Processions were a commonplace of urban life in the Middle Ages, and the members of the Bristol city government attended many public functions in this fashion, each man in his scarlet robe walking in the place appropriate to his rank and seniority.[30] In general, these processions had a double social meaning. Most obviously, they expressed in visible form the organization of the municipal government; the persons holding each of the principal offices were publicly advertised. Not only were observers made aware of the hierarchy of power within the city, they were reminded through this symbolic expression of political authority of their own proper position in the community and of the need to show deference to its leaders.[31] But in this particular case, the procession stood for something more. The presence of the magistrates in full regalia in the church asserted the legitimacy of their authority in a place where ordinarily they could not exercise control. Although technically they had power over the Bristol freemen—most of them weavers and other clothworkers—who lived within Temple Fee, they could not enforce that power directly should they meet resistance there. The procession, then, raised the problem of Temple Fee’s anomalous jurisdictional status and introduced in a dramatic way the theme of its underlying unity with the civic community as a whole. The same can be said for the procession on St. Clement’s Eve, two days earlier, to the College Green.

The transition stage of St. Katherine’s festivities shifts our attention from the status of Temple Fee to the relationship between the weavers’ gild and the municipal authorities, and from St. Katherine’s Chapel to St. Katherine’s Hall, where there were “drynkyngs” of “sondry wynes” and where “Spysid Cakebrede” was eaten by the assembled celebrants. At the Hall the mayor and his brethren became the guests of the weavers, which gave the latter the opportunity to display their wealth and manifest their importance.[32] Moreover, Ricart says, “the cuppes” were “merelly filled aboute the hous,” which signifies the drinking of “healths” among the participants; it is with the same or similar phrases that this time-honored social ritual is often identified in the late medieval and early modern period. By its nature this is a reciprocal process; healths are not merely given but exchanged. In this way the weavers secured the “amity and affection” of the city’s political leadership and, if need be, forgiveness for any wrongs. In the drinking of healths and the eating of spiced cake the sharply delineated hierarchy apparent in the processional breaks down, most probably in a degree of inebriation, a kind of licensed drunkenness. Drunkenness is the opposite of order. It wreaks havoc on both body and mind, and, as was commonly said, “nothing can be found stedfast” in it.[33]

Suitably inebriated after thus passing the cups, the membership of the city government found their way “euery man home” alone.[34] What had started as an ordered procession into Temple Fee now became a leaderless and unorganized—a disordered—movement away from it. Viewed in this fashion, the transition stage of the festival seems devoted primarily to the ceremonial stripping away of the hierarchical structure and pretensions of Bristol’s leadership.[35] This effect was only reinforced as events moved further into the night. When they reached home, the mayor, sheriff, bailiffs, and other worshipful men received “at theire dores Seynt Kateryns players, making them to drynk at their does, and rewardyng theym for theire playes.”[36] Unfortunately, Ricart tells us nothing about the nature of these plays or about the social makeup of the group of wandering performers. But we know enough to draw some tentative conclusions.

By tradition, St. Katherine was a special guardian of the Christian community against evil secular authority. The essential elements of her life concern her challenge and ultimate defeat of the emperor Maxentius, a cruel persecutor of Christians. In the end, her righteous authority triumphed over Maxentius’s injustice, fulfilling her prophecy that if he failed to correct his ways he would “be a servant.” In local festivities on her day, the figure of St. Katherine usually appeared with her assistants—sometimes children or, more commonly, lesser members of some gild—to demand tribute from the leading citizens, usually the civic authorities. The event was one of ritual submission which gave social inferiors an opportunity to exact symbolic homage from their betters. The treats they received from the leading men gave recognition that these notables were part of the same community as the players; they were a kind of toll or entry fee. By giving them, the city’s governors subordinated themselves symbolically to Katherine’s divinely inspired authority and, therefore, not only to the virtues she exemplified but to the community she represented.[37]

If this interpretation is correct, it leads us by a natural progression to the final stage of St. Katherine’s rite in Bristol: the unification of Temple Fee and its weavers with the borough community as a whole. Once again the event centers on a procession, but now the Corporation members, purged or purified by the proceedings of the previous night, join the parishioners of Temple to make a circuit of the town, ritually integrating the population of Temple Fee into the borough community. This union is sealed with a mass and offering, which combined, as John Bossy has emphasized, the principles of order and unity within social divisions. In their solemn communion, with its focus on the Kiss of Peace, the members of the Corporation were finally joined together with their fellow citizens from the parish of Temple, each in his legitimate place as members of the larger Christian commonwealth.[38] Again a similar point can be made about the celebration of St. Clement’s Day at College Green.

In this way the Feast of St. Katherine together with its companion Feast of St. Clement confirmed the principle of unity proclaimed by the late medieval borough community. According to theory, a saint was the representative in heaven of a community, ready to intercede for its members individually and collectively, so the community gained in solidarity from its veneration of his or her image or relics. In other words, a spiritual bond, mediated through sacred objects, tied together life in this world with life in the next and made the social body also a holy one, the symbol of godly order and harmony. The community represented by a saint necessarily was a microcosm of the world. It marked off within its boundaries a series of structured relationships that distinguished it from other communities and made it unique at the same time as it replicated the divine order.[39] The result in Bristol of celebrating such a saint’s day was a territorial unity that defined the boundaries of the community; a jurisdictional unity that linked its members together in a set of common rights and privileges; and a social, or even spiritual, unity that was the ideal of their common enterprise. Tension, dissent, and conflict there might well be, but not without resolution, at least in theory. These two festivals recognized the fact of territorial, jurisdictional, and social cohesion within the divided city and reaffirmed its ideals of harmony, uniformity, and solidarity.

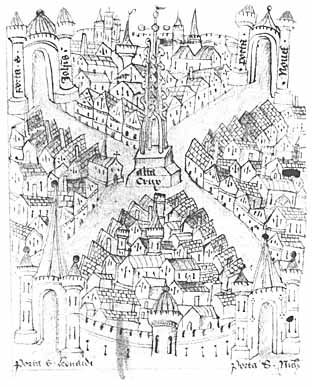

The borough community of the high Middle Ages in theory was a bounded world, a communion of interests and purposes separating the townsmen and their life of trade from the agrarian existence of the rest of England. The feasts of St. Clement and St. Katherine confirmed these ideals of community in the face of social and economic tensions that by 1400 had begun to threaten their foundations. In symbolic form they integrated the weavers and mariners into the body politic of the city. Robert Ricart, in his map of the city at its foundation, also conveyed this vision of Bristol as an emblem of the cosmos (Figure 4).[40] This map, in which Bristol sits upon a little hill between four gates, portrays a nearly perfect example of what Werner Müller has identified as the Gothic town plan. It is a city built as “the navel of the world,” a cross within a circle, representing the heavenly Jerusalem, in which the four main streets divide the world into its four component parts.[41] It puts into visible form, then, the ordered community which found its highest expression on Corpus Christi, when the civic body, the crafts, and the other citizens proceeded through the town, each in his proper place, in veneration of the host.[42]

Fig. 4. Robert Ricart’s Plan of Bristol at Its Foundation. (Robert Ricart, The Maire of Bristowe Is Kalendar, Bristol Record Office, MS 04720 (1), f. 5. By permission of the City of Bristol Record Office.)

In general, all of Bristol’s late medieval festive life encouraged its citizens to conceive of their city in this way, as a microcosm embedded in the larger order of God’s universe. It also yielded a subtle commentary on the nature and distribution of political authority. In ritual and festival the civic community appeared as a bounded world of reciprocal relations—of harmonies and correspondences—not of absolutes. For, taken together, events like the celebration of the feasts of St. Clement and St. Katherine emphasized the social limitations on authority, not the sovereignty of those who exercised it. They focused on the membership of the mayor and his brethren in the commonalty of burgesses and freemen, and on the need for communal acceptance of their earthly rule.

The ceremonial practices we have just analyzed survived intact until the middle of the sixteenth century, but long before they disappeared there were signs that many Bristolians had come to doubt their efficacy. By the early fifteenth century, for example, most townsfolk had become indifferent to the great Corpus Christi processions, which had once been among the most popular religious celebrations and the preeminent means of expressing the town’s hierarchical organization and spiritual kinship.[43] Even Ricart’s loving codification of the annual cycle of feast and ceremony may be a sign that some Bristolians—like Mayor William Spencer, who commissioned Ricart’s book—thought their ancient customs needed to be preserved and reinforced among the civic elite. By the 1530s, moreover, the city had begun welcoming organized troupes of players to the city to perform their entertainments indoors in the Guildhall for a small elite, competing with St. Katherine’s players in both substance and form.[44]

But the old ceremonies themselves persisted into the era of Reformation. With the combined attack on popish “superstitions,” religious orders, and chantries, however, the framework described by Ricart suffered permanent and irreversible change. In 1541 Henry VIII ordered the abolition of the “many superstitious and chyldysh obseruances…observed and kept…vpon Saint Nicholas, Saint Catherine, Saint Clement, the Holy Innocents and such like.”[45] Corpus Christi suffered a similar fate, disappearing from the church calendar with the publication of the Edwardian prayer books.[46] Of course, deep religious divisions persisted in the city in the mid-sixteenth century, as Roger Edgeworth made clear in the sermons he delivered during this period of upheaval.[47] At the same time, many tradition-minded laymen, including the great Spanish merchant Robert Thorne, and such clergymen as Edgeworth himself and Paul Bush, the Marian bishop in Bristol, still ardently upheld the old forms of piety.[48] But this cultural politics did not extend its defense of customary practices to the excesses associated with the old holidays and pastimes. Against the surge of Protestant reform, the defenders of tradition in Bristol advanced their sober new vision of devotion, which preserved the crosses and the images but condemned the “gluttony” and “lechery” of traditional culture.[49] By Elizabeth I’s and James I’s time, learned Protestant ministers such as Northbrooke, Thomas Thompson, and Edward Chetwyn were striking even more vigorous hammer blows against idle pastimes and drunkenness. Under these strictures, celebrations such as those that honored St. Katherine and St. Clement stood utterly condemned for their depravity.[50]

Although many of Bristol’s late medieval gilds, like St. Clement’s and St. Katherine’s, survived the dissolution of the chantries into the later sixteenth century and beyond, they did so as a result only of the reassignment of their properties for charitable purposes, not of the survival of their old religious spirit.[51] At the same time, the feasts of St. Clement and St. Katherine disappeared from the civic calendar. One reason for the quick and relatively painless demise of the two saints’ days is supplied by Henry VIII’s attack on the church. With the dissolution of the monasteries and the suppression of the religious orders in England, the liberty of St. Augustine’s Abbey, already under vigorous attack by the city and the Crown in the 1490s,[52] ended in December 1539, with the dissolution of the monastery. In 1541, when the Knights Hospitallers were disbanded, the liberty of Temple Fee was also quashed.[53] These changes transformed the spiritual geography of Bristol. No longer did the civic map contain hot spots of great religious power but temporal pollution, where debtors could dodge creditors, illicit traders could keep open shops, and outlaws could flaunt their disregard of all just authority.[54] Now the command of the mayor and his brethren was efficacious in every quarter of the city, and every inhabitant, burgess and stranger, was subject to their rule. The city was freed from the potential for lawlessness and violence always inherent in the existence of the religious enclaves. In consequence, crossing the Frome into St. Augustine’s or the Avon into Temple no longer had the political or social significance it once did. As these districts became legally integrated into the city’s body politic, they became in a sense demystified. At the same time, the city achieved a new kind of religious unity, for in 1542 the property of St. Augustine’s Abbey became the foundation of the diocese of Bristol, carved out of the old bishoprics of Worcester and Bath and Wells.[55] For the first time, Bristol was under one episcopal administration.

But along with these alterations in traditional church administration came deeper changes in the fabric of social life in Bristol, changes in the structure of authority and distribution of power that provide the wider context for the rituals we have been examining. These developments transformed the medieval community and robbed the ceremonies of their old efficacy. We have already studied the emergence of a new form of commercial community in Bristol as the city’s economy shifted decisively away from France to focus on southern Europe and the Atlantic. By the mid-sixteenth century, control of overseas trade had fallen into the hands of a small and exceedingly tight-knit group of dealers. As the scale and internal organization of the merchant community changed, so too did its relations with the larger English economy. The city was no longer a restricted market in which all citizens had an equal opportunity to buy the goods of strangers. As we know, the common practice now was for outside dealers to have fixed contracts with particular Bristolians, using the old fairs and market hall not as places for free buying and selling but to meet regular customers or agents, settle accounts, and strike new bargains. From 1546, even the collection of tolls at the city gates had been abandoned, and in consequence the ancient distinction between strangers and citizens lost much of its economic and cultural force.[56]

Accompanying these changes were shifts in the social geography of the city. From wills and deeds we know a good deal about where the leading men in Bristol resided in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. For some of the richest citizens, such as the great Canynges family, the favored places were great stone mansions in Redcliffe and other southern parishes where land was available for gardens and orchards. Others preferred locations on the city wall, where stone towers made imposing residences. And, of course, many lived in the city center, where they enjoyed maximum command of the urban market.[57] Hence the city’s “better and more worthy” men were rather evenly distributed through the neighborhoods. We can see this quite clearly by examining the residences of the city’s common councillors at this time. We know the names of the forty-two councillors in 1381 and of fourteen others added between that date and 1409; of these, the residences of thirty-eight can be established. Twenty lived in the central city, and eighteen in the three parishes east and south of the Avon.[58] On St. Katherine’s Eve in the late fourteenth century, therefore, the procession from the Guildhall to Temple Church would have taken many Corporation members back toward their homes and about equal numbers away from them. And when St. Katherine’s players went from door to door to perform for these men, they would have toured the whole town.

The same list of common councillors allows us to establish something of the occupational structure of the city’s governing elite. Nearly all its members, wherever they lived, engaged in overseas trade to some degree. Most identified themselves as “merchants and drapers,” and many had properties both in the center and in the southern parishes. They were entrepreneurs who organized the woolen industry and traded its products in foreign markets without any differentiation of retail shopkeeping from wholesale trading or from the financing of cloth production. At least two councillors seem to have been members of St. Katherine’s gild.[59] Given the close ties between mariners and merchants, we can assume that a number of councillors became members of St. Clement’s when it was founded in the 1440s. Hence intimate economic and social connections linked the members of Bristol’s corporation and the members of the gilds of St. Clement and St. Katherine. In this period, on the feast days of the two saints it was not a distant body of strangers who came to the gild chapels but men with whom the gildsmen dealt week in and week out.

By the early sixteenth century much of this had changed radically. Where the evidence for the late fourteenth century suggests an even distribution of wealth through the city, in the 1520s we find quite distinct differences. According to statistics derived from the records of the subsidy in 1524, the center and portside parishes possessed 72 percent of the city’s taxable wealth, although during the second quarter of the sixteenth century only about 48 percent of the city’s population resided there (Table 18).[60] In this district now dwelled Bristol’s richest inhabitants, as well as a large number of middling types. Although a number of wage earners also lived there, they were concentrated primarily in a few streets near the city’s wharfs and the butchers’ shambles. Not only did the suburban districts to the north of the Frome and to the east of the Castle and in the transpontine district to the south of the Avon contain fewer wealthy residents, but those who did live there possessed smaller holdings than their counterparts in the center, and in place of the middling men we find larger numbers of individuals living on wages.

| Parishes / Mean Assessment | Assessments in £[a] | No. Assessed | % | Total Assessed Valuation (£-s-d) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Public Record Office, E 179/113/192 (lay subsidy roll dated 10 January, 15 Hen. VIII). For purposes of analysis the city’s parishes have been divided as follows: Center: All Saints; Christ Church; St. Ewen; St. John; St. Lawrence; St. Leonard; St. Mary-le-Port; St. Peter; St. Werburgh. Portside: St. Nicholas; St. Stephen. Transpontine: St. Mary, Redcliffe; St. Thomas; Temple. Suburban: St. Augustine; St. James; St. Michael; SS. Philip and Jacob. | |||||

| Center and Portside / £12-10-00 | 101+ | 11 | 1.93 | 2,040-00-00 | 28.63 |

| 21 to 100 | 60 | 10.53 | 2,950-00-00 | 41.40 | |

| 6 to 20 | 122 | 21.40 | 1,369-00-00 | 19.21 | |

| 2+ to 5 | 85 | 14.91 | 325-04-00 | 4.56 | |

| 2 | 96 | 16.84 | 192-00-00 | 2.69 | |

| 1 to 2 | 196 | 34.39 | 249-05-00 | 3.50 | |

| Total | 570 | 7,125-09-00 | |||

| Transpontine and Suburban / £5-13-04 | 101+ | 3 | 0.62 | 430-00-00 | 15.56 |

| 21 to 100 | 24 | 4.93 | 1,173-00-00 | 42.46 | |

| 6 to 20 | 48 | 9.86 | 475-13-04 | 17.22 | |

| 2+ to 5 | 52 | 10.68 | 193-13-04 | 7.01 | |

| 2 | 101 | 20.74 | 202-10-00 | 7.31 | |

| 1 to 2 | 259 | 53.18 | 288-10-00 | 10.44 | |

| Total | 487 | 2,762-16-08 | |||

| City Total / £9-07-02 | 101+ | 14 | 1.32 | 2,470-00-00 | 24.98 |

| 21 to 100 | 84 | 7.95 | 4,123-00-00 | 41.70 | |

| 6 to 20 | 170 | 16.08 | 1,844-13-04 | 18.66 | |

| 2+ to 5 | 137 | 12.96 | 518-17-04 | 5.25 | |

| 2 | 197 | 18.64 | 392-00-00 | 3.98 | |

| 1 to 2 | 455 | 43.05 | 539-15-00 | 5.44 | |

| Total | 1,057 | 9,888-05-08 | |||

Evidence derived from the subsidy records from 1545 and other documents from this period gives us a more detailed view of the geographical distribution of occupations. The picture is of a city in which overseas merchants, rich retailers such as grocers, mercers, and drapers, and small shopkeepers such as shoemakers and tailors dominated the city’s center, while large-scale manufacturers such as clothiers, brewers, and tanners lived in the outdistricts, along with small artisans such as weavers and wiredrawers and servants and wage-earning employees; the leather and brewing industries were located to the north of the Frome and the cloth industry to the south of the Avon. Overseas trade accounted for the richest citizens, although the retailing of luxuries and the manufacture of leather also produced significant numbers of wealthy men (Table 19). Since the Corporation drew its membership only from among the city’s “better and more worthy men,” it was now made up primarily of figures drawn from these sectors of the economy, not from the textile industries. Patterns of residence among the Corporation members also changed. Nearly all of them now lived near the Guildhall in the city center or in the two immediately adjoining portside parishes. There was almost no participation by those dwelling in the clothmaking district across the Avon or in the other outparishes.

| Occupations | Center | Portside | Transpontine | Suburban | City Total | Mean Assessment in £ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Public Record Office, E 179/114/269 (lay subsidy roll dated 4 March, 37 Hen. VIII). The districts are defined as in Table 18. | ||||||

| Male householders | ||||||

| A. Leading entrepreneurs: | ||||||

| Merchants | 38 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 67 | 25.70 |

| Major retailers | ||||||

| draper | 5 | 14 | 19 | 19.47 | ||

| fishmonger | 4 | 4 | 7.00 | |||

| grocer, apothecary | 21 | 1 | 2 | 24 | 19.81 | |

| haberdasher | 2 | 1 | 3 | 16.67 | ||

| innkeeper, vintner | 5 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 16.60 | |

| mercer | 9 | 2 | 11 | 27.75 | ||

| Subtotal | 46 | 19 | 6 | 71 | 19.64 | |

| Soapmakers | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 14.86 | |

| Total A | 87 | 47 | 10 | 1 | 145 | 22.21 |

| B. Textile production: | ||||||

| Clothier | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5.50 | ||

| Dyer | 5 | 5 | 9.80 | |||

| Sherman | 8 | 8 | 6.25 | |||

| Tucker | 8 | 8 | 11.17 | |||

| Weaver | 5 | 5 | 6.40 | |||

| Total B | 1 | 1 | 26 | 28 | 8.26 | |

| C. Leather production: | ||||||

| Currier | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9.33 | ||

| Skinner | 5 | 5 | 12.20 | |||

| Tanner | 2 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 25.62 | |

| Whitawer | 4 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 15.08 | |

| Total C | 12 | 1 | 3 | 17 | 33 | 18.27 |

| D. Clothing production: | ||||||

| Capper | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9.00 | ||

| Glover, purser | 4 | 4 | 9.25 | |||

| Hosier | 2 | 2 | 6.50 | |||

| Pointmaker | 1 | 1 | 12.00 | |||

| Saddler | 1 | 1 | 5.00 | |||

| Shoemaker | 5 | 3 | 8 | 6.75 | ||

| Tailor | 11 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 9.43 | |

| Upholsterer | 1 | 1 | 17.00 | |||

| Total D | 26 | 6 | 10 | 42 | 8.85 | |

| E. Metal crafts: | ||||||

| Bellfounder | 1 | 1 | 5.00 | |||

| Cardmaker | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7.50 | ||

| Pewterer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 19.67 | ||

| Smith | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9.67 | ||

| Wiredrawer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11.33 | ||

| Total E | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 11.83 |

| F. Food production: | ||||||

| Baker | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 12.89 |

| Brewer | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 13.59 |

| Butcher | 4 | 1 | 5 | 19.20 | ||

| Total F | 10 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 23 | 14.54 |

| G. Shipping industry: | ||||||

| Hooper, cofferer | 2 | 8 | 10 | 11.63 | ||

| Mariner, ship’s captain | 2 | 2 | 11.50 | |||

| Ropemaker | 4 | 4 | 13.58 | |||

| Ship’s carpenter | 1 | 1 | 12.00 | |||

| Total G | 2 | 15 | 17 | 12.10 | ||

| H. Professional, etc.: | ||||||

| Attorney, lawyer | 2 | 2 | 12.00 | |||

| Barber | 2 | 2 | 7.00 | |||

| Clerk | 1 | 1 | 30.00 | |||

| Government official | 1 | 1 | 19.33 | |||

| Scrivener | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10.50 | ||

| Stationer | 1 | 1 | 5.00 | |||

| Surgeon | 1 | 1 | 7.00 | |||

| Total H | 3 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 12.03 | |

| I. Miscellaneous: | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6.17 | ||

| Total known A–I | 149 | 77 | 63 | 27 | 316 | 16.66 |

| Total unknown A–I | 22 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 49 | 13.09 |

| Total male householders | 171 | 85 | 76 | 33 | 365 | 16.18 |

| Female householders | 13 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 25.18 | |

| Servants | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2.69 | |

| Grand Total | 187 | 89 | 81 | 35 | 392 | 16.46 |

| Mean Assessment in £ | 18.17 | 18.10 | 9.98 | 18.64 | 16.46 | |

In the midst of these developments Bristol’s civic constitution also changed, in a manner that reinforced the building relationship between the community and the wider world and further broke down the old fabric of self-enclosed communal life. In 1499, Henry VII confirmed Bristol’s liberties and immunities but altered the structure of its governing body, primarily by creating a bench of aldermen. The mayor and aldermen received designation as justices of the peace, which brought the city into conformity with the national system of administration then emerging in the counties. At the same time, the recorder—usually an up-and-coming London lawyer—became fully integrated into town government as one of the aldermen. His presence was required at gaol delivery, of which the mayor and aldermen were now to be justices. Since the mayor also served as one of the two justices of assize, the civic body was formally bound into the judicial and administrative structure of the nation. This meant that the status and power of the leading men in town government were increased, whether they were acting at any given moment as royal or as purely local officials. It also meant that the Crown, through the mayor and aldermen, now had a direct and continuous link to the city government upon which both the city and the Privy Council could rely.[61]

Occasionally the tensions inherent in these new political and social arrangements flared into open conflict. For example, in the disputes that arose in 1543 over the existence of the Candlemas fair in the parish of St. Mary, Redcliffe, the opposing parties reflect almost exactly the new geographical and sociological divisions we have been discussing. The supporters of the fair were primarily artisans resident in the city’s outdistricts, most from south of the Avon and a few from north of the Frome. Its critics, who supported the city government’s Star Chamber suit to quash the fair, came from the central district, and especially from the richest and most powerful groups living there, the great merchants and the major retailers.[62] As a result, the city’s social divisions, which the old festivals had sought to overcome in favor of unity and harmony in communal life, now seem to have become wounds in the body politic.

The development of Bristol’s economy in the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries had made it increasingly difficult for the old festivals to mark the community’s separation from the wider world and to reinforce its internal order. Mervyn James has sought to explain a similar transition by referring to the ways that the sixteenth century “progressively upset” the “social and political balance” of the late medieval urban community. “The degree of impoverishment of gild organizations,” he says,

This interpretation suggests that the members of a strident, secularized urban elite in the end forced their new views of the social world on their social inferiors. But it seems clear that in Bristol the ruled as well as the rulers no longer found the ancient ceremonies acceptable or efficacious, with the former perhaps preceding the latter to this conclusion.the pauperization of town populations, the changing character and role of town societies, increasing government support of urban oligarchies were all factors tending toward urban authoritarianism. As a result urban ritual…no longer served a useful purpose; and [was] indeed increasingly seen as potentially disruptive of the kind of civil order which the magistracy existed to impose.[63]

Late medieval Bristol was one of England’s great centers of Lollardy, which anticipated many of the ideas of early Protestantism. Indeed, the presence of Lollards there in the early fifteenth century was sufficiently important that Robert Londe, schoolmaster at New Gate in Bristol, made them the subject of one of his vulgaria, designed to teach his young charges the finer points of Latin grammar and syntax through the use of socially and culturally relevant materials.[64] In its early years the movement in Bristol had a large clerical leadership headed by John Purvey, Wycliffe’s companion during his last days. The city even supplied six chaplains to Sir Thomas Oldcastle’s army on St. Giles Field in 1414. But from the outset the movement also enjoyed significant lay support in Bristol. Along with the six chaplains at St. Giles Field, for example, came forty other townsmen, the largest contingent of supporters from a single community in the Lollard army in this rebellion. Most of these men were weavers from the three southern parishes of the town. Moreover, despite the persecution of this group and of other Bristol Lollards in the fifteenth century, Lollardy had too strong a hold in the city to be eliminated. Throughout this century and into the next, ecclesiastical authorities continued to uncover groups of heretics professing Lollard beliefs. Like those who went to join Oldcastle, these men and women came primarily from the cloth industry, and from the city’s southern parishes; most were weavers.[65]

The connection between the cloth industry and Lollardy in Bristol draws us again into the world of the cloth gilds. In late medieval Bristol, these bodies were not only fraternities of craftsmen, organized in a fellowship of common interests for the protection and regulation of their mystery, but brotherhoods of the faithful, united in the name of their patron saint for prayer and for honoring the dead. Moreover, their seemingly distinct functions were inextricably intertwined. Gildsmen were expected to come to the general processions of their fellowship on Corpus Christi and on feast days, to support the gild’s chapel if it had one, and even to make payment of fines for violating the economic regulations of their craft in wax, for the maintenance of their saint’s candle.[66]

Under these conditions, resistance to the economic policies reinforced by the gilds could hardly help taking a religious form among many of the disaffected. Here the doctrines of Wycliffe and the Lollards offered an especially potent weapon. Wycliffe’s emphasis on the authority of the Bible, his rejection of transubstantiation, his stress on predestination, and his criticism of the doctrine of penance and its liturgy all were important elements in the beliefs of his followers.[67] But among the laity, especially after Oldcastle’s defeat, particular attention was paid to his rejection of the Real Presence and of the veneration of saints. In Bristol this focus was especially strong. Again and again its Lollards crudely attacked the main beliefs and practices of late medieval Catholic piety. They complained against worship in Latin, and they argued that “the sacrament of thalter is not the very body of our lorde but material brede.” But most of all they professed hostility to the saints, claiming that prayer should be made directly to God, not through holy intercessors, offerings to whose images were damnable.[68] But if religious observance was but the obverse of economic regulation in the life of the gilds, an attack on prayers for the dead, the veneration of saints, and the honoring of holy images such as the Bristol Lollards had mounted became at the same time an attack on the governing institutions of the domestic economy, the gild leadership, and the city government that supported it. Many of these Bristolians must have found Wycliffe’s harsh criticisms of the craft gilds congenial to their views.[69]

A series of ordinances of 1419 exemplify this combination of religion and economics. In that year, coming at the height of official reaction to Bristol Lollardy, the four Masters of the weavers’ gild petitioned the mayor and the Common Council for new ordinances. They complained that their own authority “had been greatly and grievously vexed” by violators of the weavers’ ordinances, “because they had not the same ordinances” under the common seal of the town. They desired, therefore, to have the old ordinances, with their mix of economic and religious precepts, confirmed under the city’s seal, a request to which the city government readily agreed.[70] Clearly a strong challenge to gild rule had been mounted. At the same time, two other ordinances, even more revealing in their nature, were also passed. These required, first, that all the masters and servants of the craft “come to the general processions and to the other precepts of the Mayor” and, second, that they “shall be contributors to all kinds of costs and expenses which shall be incurred…on their light and torches against the feasts of Corpus Christi” and the midsummer vigils.[71] The breakdown of gild authority in this period thus affected both its secular and its spiritual aspects.

Lollard rejection of gild practices was the most extreme form of opposition to the system of gild regulation in force in late medieval Bristol. However, because gild ordinances often advanced some economic interests against others, there were also many other reasons for criticism and resistance to them. Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing for certain when we should attribute such troubles within the gilds primarily to the Lollards, although we know the names and beliefs of many of Wycliffe’s adherents in the city. But there can be no doubt that resistance to gild governance based on many of the same grievances the Lollards complained about persisted among the weavers until well into the fifteenth century. In 1463, for example, the “pore artificers” of the gild complained that the four Masters annually elected by the livery put the “poure Craftymen daily to grete iniuries wronges and importable fynes the which fynes…is not hadd to the sokour and Comyne weele of the seide crafte but only to a synguler avayle of the seid Maisters and their owne Purs.” The fines in question, of course, went not into the Masters’ own pockets but to the support of the gild’s activities: the hall, the chapel, the processions, the gild dinner on St. Katherine’s Eve, and the like. To resist the fines was to leave these gild traditions, spiritual as well as temporal, without proper enforcement, or possibly even to reject them outright. The main remedy the commons requested from the Bristol Corporation is also revealing, for they argued that the Masters were chosen “yerely notte by the will and assent of the hoole crafte but by the xii men” of the livery “sucche as they wolle call thayme self whereof we byseeke yow that they may be choszen by the hoole body of the crafte.”[72] They desired a restoration of the gild’s old constitution, under which all had united in common effort. A gulf had opened between the views of the gild elite and its commoners, a gulf characterized by the view that the elite no longer ruled for the common good but only for their own benefit.

These difficulties among the weavers are evidence of disaffection in their ranks in the mid-fifteenth century, not of heresy. They were not necessarily caused by the Lollards, although Lollard activity persisted among weavers and other clothworkers during this period and after.[73] Nevertheless, signs of resistance to gild practices reveal a general cultural or moral malaise in the cloth industry, a sense that the old ways no longer had significance for current problems. This mood may have resulted, in part at least, from the shifting nature of woolen manufacture in later fourteenth and early fifteenth-century Bristol. As country clothmaking grew, more and more of the cloth woven within the city seems to have been of much cheaper quality than had been the case a century before.[74] Probably the number of Bristol weavers also declined, though, judging from the frequent mention of weavers among the sixteenth-century burgesses, they seem to have declined more in wealth than in total numbers.[75] These changes would have made it increasingly difficult for the weavers to maintain their former gild practices, either in the vigorous supervision of ordinances or in the dutiful performance of rituals. But economic distress by itself cannot explain the weavers’ apparent indifference to or rejection of their gild’s traditional religious practices. One might expect that, if the gildsmen’s faith in their traditions had remained strong, under these troubled economic conditions they would seek solace, protection, and guidance from their processions, their vigils, and their lights. However, many of the weavers chose a different course. Rather than drawing together under the name and effigy of their patron saint, they strayed from the community and the discipline of their gild.

Thus, about the same time that St. Katherine’s festival had acquired the form that Ricart describes, or soon thereafter, a significant group of weavers, her earthly clients, not themselves a part of the gild leadership, had tired of its religious foundations. Some had even rejected them outright, though their masters and social betters still supported them. Similarly the town’s leaders remained faithful in the fifteenth century to the celebration of Corpus Christi, when lesser men not only among the weavers but in other gilds such as the shoemakers had lost their enthusiasm for it. Already in the 1420s punitive ordinances existed requiring participation in the great procession which once had been so overwhelmingly popular.[76]

By the 1530s this rejection of the cult of the saints was very general in Bristol. The theme was struck almost at the very outset of the Reformation by Hugh Latimer, who won the support of large numbers of leading townsmen, both in the Common Council and out, when he preached in Lent 1533. In these extremely popular sermons he lashed out particularly against the old Lollard target, the idolatrous worship of saints, which Latimer saw all around him:

Such views carry with them large social and political as well as philosophical and religious implications. Although they do not necessarily preclude adherence to some principles of Catholic belief or lead directly to radical Protestantism, they reject a regime as well as a liturgy. They show that many Bristolians, like the disaffected weavers of the fifteenth century, no longer found meaning in some of the most important rituals around which they had organized their public and private lives.I said this word “saints” is diversely taken of the vulgar people: images of saints are called saints and inhabitors of heaven are called saints. Now by honouring of saints is meant praying to saints. Take honouring so, and images so, saints are not to be honoured: that is to say, dead images are not to be prayed unto, for they have neither ears to hear withal, nor tongues to speak withal, nor heart to think withal &c. They can neither help me nor mine ox, neither my head nor my tooth, nor work any miracles for me more than another.[77]

Within a few short years, moreover, these reformist views were put into action all over the city. “[A]t the dissolucion of Monasteries and of Freers houses,” we are told by Roger Edgeworth,

Although Edgeworth greatly lamented this desecration of images and fought desperately against it, he could do little to restore the faith many Bristolians once had in them. The most solemn devotions had taken on the character of childish things.[79]many Images haue bene caryed abrode, and gyuen to children to play wyth all. And when the chyldren haue theym in theyre handes, dauncynge theim after their childyshe maner, commeth the father or the mother and saythe: What nasse, what haste thou there? the child aunsweareth (as she is taught) I haue here myne ydoll, the father laugheth and maketh a gaye game at it. So saithe the mother to an other, Iugge, or Thommye, where haddest thou that pretye Idoll? John our parishe clarke gaue it me, saith the childe, and for that the clarke muste haue thankes, and shall lacke no good chere.[78]

| • | • | • |

Among the possible explanations for this decline in the traditions of late medieval piety, the history we have been recounting suggests an association with two quite closely related changes in social setting: first, the rise of regional or national or international networks of trade and industry, which undermined an individual’s sense of participation in a self-enclosed economic world; and, second, the growth of social stratification in urban society, which by driving a wedge between the rich and powerful, on the one hand, and the mere craftsmen and small shopkeepers, on the other, made it difficult for many to think of themselves as brothers and sisters in a fellowship of common purposes and interests. The great civic ceremonies of the later Middle Ages emphasized the inherent unity of city life under its apparent diversity, but they could have meaning only within certain limits. As the horizons of economic activity opened and social distances grew, the members of the community must have found it increasingly difficult to conceive of Bristol as a world unto itself. For these citizens the town had opened to the larger world, which penetrated the community and reshaped it. Hence the ceremonies that once had marked the community’s separation from its surroundings and unified its structure became archaisms. Like antiquated words or phrases, they had lost their context and therefore passed from use.

Notes

1. John Northbrooke, Spiritus est Vicarius Christi in terra: A Treatise wherein Dicing, Dauncing, Vaine playes, or Enterluds, with other idle pastimes, &c, commonly vsed on the Sabboth day, are reproued by the Authoritie of the word of God and auntient writers (London, [1577]). The Shakespeare Society edition, ed. J. P. Collier (Shakespeare Society 16, 1843), has been used here; see pp. 15, 44, 52, 90. Northbrooke served as minister of St. Mary, Redcliffe, Bristol from 1568 and was an important figure in the city’s religious life in the 1570s: Thomas Tanner, Bibliotheca Brittanico-Hiberica (London: G. Bowyer, 1748), p. 550. The Company of Stationers of London records the license for printing on 2 December 1577: E. Arber, ed., A Transcript of the Register of the Company of Stationers of London, 1554–1640, 5 vols. (New York: P. Smith, 1949–1950), vol. 2, p. 321. I am grateful to Katherine Pantzer of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, for advice on the history of this text.

2. John Latimer, Sixteenth-Century Bristol (Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith, 1908), pp. 5–6.

3. Ibid.

4. Northbrooke, Treatise, p. 12.

5. Robert Ricart, The Maire of Bristowe Is Kalendar, BRO, MS 04720 (1). The Camden Society edition has been used here; see p. 69. For Ricart’s background, see ibid., p. i.

6. Northbrooke, Treatise, pp. 11–13.

7. Paul Hughes and James Larkin, eds., Tudor Royal Proclamations, 3 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964–1969), vol. 1, pp. 301–2; see also David Wilkins, ed., Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, a Synodo Verolamiensi A.D. CCCCXLVI. ad Londinensem A.D. MDCCXVII. Accedeunt constitutiones et alia ad historiam Ecclesiae Anglicanae spectantia, 4 vols. (London: Sumptibus R. Gosling, 1737), vol. 3, pp. 823–24, 857, 859–60.

8. John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials Relating Chiefly to Religion and the Reformation of It, Shewing the Various Emergencies of the Church of England under King Henry VIII, King Edward VI and Queen Mary I, 3 vols. in 6 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1822), vol. 3, part 2, p. 506, and see also pp. 8–9, 14–15, 17, 18, 21, 22; J. G. Nichols, ed., The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, from A.D. 1550 to A.D. 1563 (Camden Society, 1st ser., 42, 1848), p. 119. For the efforts of Catholic apologists in Bristol to revive the traditional forms of religious observation, see Paul Bush, A brefe exhortation set fourthe by the vnprofitable seruant of Jesu christ Paule Bushe, late bishop of Brystowe, to one Margarite Burges, wyfe of John Burges, clotheare of kyngeswode in the Countie of Wiltshire (London, 1556); Edgeworth, Sermons (London, 1557); see also K. G. Powell, The Marian Martyrs and the Reformation in Bristol (Historical Association, Bristol Branch, pamphlet 31, 1972). For the Elizabethan reaction to this effort at revival, see Wilkins, ed., Concilia Magnae Britanniae, vol. 4, pp. 182–91, 196–97, 211–14; F. E. Brightman, The English Rite being a Synopsis of the Sources and Revisions of the Book of Common Prayer, 2d rev. ed., 2 vols. (London: Rivingtons, 1921), vol. 1, pp. 98–101. J. J. Scarisbrick has argued that popular support for the traditional forms of lay piety persisted long into the sixteenth century: J. J. Scarisbrick, The Reformation and the English People (Oxford: Blackwell, 1984); see also Christopher Haigh, “Revisionism, the Reformation and the History of English Catholicism,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 36 (1985): 394–406; Christopher Haigh, ed., The English Reformation Revised (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). A. G. Dickens has responded to these criticisms of his views in “The Early Expansion of Protestantism in England, 1520–1558”, Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 73 (1987): 187–222. For a systematic consideration of this debate and a telling response to some of the claims of Scarisbrick and Haigh, see Patrick Collinson, The Birthpangs of Protestant England: Religious and Cultural Change in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), esp. chaps. 2, 4; see also Robert Whiting, The Blind Devotion of the People: Popular Religion and the English Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), esp. chap. 13.

9. For criticisms along these lines see, e.g., Ozment, ed., Three Behaim Boys, pp. xi–xiii.

10. Edgeworth, Sermons, f. 214r.

11. Putnam, Meaning and the Moral Sciences, pp. 42, 43–44. I have given further attention to some of these issues in “The Hedgehog and the Fox Revisited,” pp. 267–80.

12. See Cronne, ed., Bristol Charters, 1378–1499, pp. 64–69, 73–80; Gross, Gild Merchant, vol. 1, chaps. 2–4, and vol. 2, pp. 24–25, 353–55; Susan Reynolds, An Introduction to the History of English Medieval Towns (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), chaps. 4–5; Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, chap. 1.

13. See N. Dermott Harding, ed., Bristol Charters, 1155–1373 (BRS 1, 1930), pp. 120ff.; Cronne, ed., Bristol Charters, 1378–1499, pp. 40–56; Martin Weinbaum, The Incorporation of Boroughs (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1937), pp. 54–56; Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, pp. 22ff.

14. Carus-Wilson, Medieval Merchant Venturers, pp. 1–97; M. D. Lobel and E. M. Carus-Wilson, “Bristol,” in M. D. Lobel, ed., Historic Towns (London: Lovell Johns—Cook, Hammond and Kell Organization, 1975), pp. 1–16; Sherborne, Port of Bristol; C. D. Ross, “Bristol in the Middle Ages,” in C. M. MacInnes and W. E. Whitterd, eds., Bristol and the Adjoining Counties (Bristol: Bristol Association for the Advancement of Science, 1955), pp. 179–92; see also Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, chaps. 1–6.

15. LRB, vol. 1, p. 51; for a later version of the oath preserving most of its original terms, see McGrath, ed., Merchants and Merchandise, pp. 26–27.

16. Mariners were itinerant merchants, and their gild was closely associated from the earliest days with Bristol’s sedentary merchants; see above, p. 90; Latimer, Merchant Venturers, pp. 19–21.

17. LRB, vol. 2, pp. 2–6; Fox and Taylor, eds., pp. 10–14. On the history of Bristol’s governing council, see Cronne, Bristol Charters, 1378–1499, pp. 50, 73–83. It was only in 1344 that Bristol acquired a council of forty-eight, broadly representative of the leading men in the textile trades: LRB, vol. 1, pp. 25ff. And only in 1373 did its council become a body consisting of mayor, sheriff, and forty of “the better and more worthy men” of the borough: Harding, ed., Bristol Charters, 1155–1373, pp. 136–37. An earlier attempt to set up a select council of fourteen in Bristol had led to a rebellion in the city: see E. A. Fuller, “The Tallage of Edward II and the Bristol Rebellion,” BGAS 19 (1894–1895): 171–278, esp. pp. 191ff.; Seyer, Memoirs, vol. 2, pp. 89ff.; John Latimer, ed., Calendar of the Charters &c. of the City and County of Bristol (Bristol: W. C. Hemmons, 1909), pp. 42ff.

18. Latimer, Merchant Venturers, p. 19n.

19. John Leland, The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the Years 1535–1543, ed. Lucy Toulmin Smith, 5 vols. (Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 1964), vol. 3, p. 101.

20. See Lobel and Carus-Wilson, “Bristol”; for further discussion see Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 2, pp. 482ff.

21. Cronne, ed., Bristol Charters, 1378–1499, pp. 35–39.

22. Ralph, ed., Great White Book, pp. 17–67; Latham, ed., Bristol Charters, 1509–1899, pp. 21–22, 27–29, 93–94; VCH Gloucestershire, vol. 2, p. 78; John Britton, The History and Antiquities of the Abbey and Cathedral Church of Bristol (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, 1830), pp. 21–22; PRO, STAC 2/6/93–94; Latimer, Sixteenth-Century Bristol, pp. 16–18.

23. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80; Fox and Taylor, Guild of Weavers, pp. 10–14.

24. Gross, Gild Merchant, vol. 1, pp. 43–45; LRB, vol. 1, pp. 36–38.

25. See above, pp. 20–21; Carus-Wilson, Medieval Merchant Venturers, pp. 28–49; Sacks, Trade, Society and Politics, vol. 1, chap. 6.

26. John Brand, Observations on Popular Antiquities: Chiefly Illustrating the Origin of Our Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies and Superstitions, ed. Henry Ellis, 5 vols. (London: C. Knight, 1841–1842), vol. 1, pp. 408–14, 461–66; A. R. Wright, British Calendar Customs: England, ed. T. E. Lones, 3 vols. (London: W. Glaisher, 1936–1940), vol. 3, pp. 167ff.

27. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80.

28. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Victor Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969), esp. chaps. 3–5; Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974), chaps. 1, 5–7; Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), chap. 4; Victor Turner, The Drums of Affliction: A Study of Religious Processes among the Ndembu of Zambia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), chap. 9. See also Edmund Leach, “Time and False Noses,” in Edmund Leach, Rethinking Anthropology (London: Athlone Press, 1961), pp. 132–38.

29. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80.

30. Ibid., pp. 68ff.

31. See Charles Phythian-Adams, “Ceremony and the Citizen: The Ceremonial Year at Coventry, 1450–1550,” in Peter Clark and Paul Slack, eds., Crisis and Order in English Towns, 1500–1700: Essays in Urban History (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972), pp. 59, 62–63; Mervyn James, “Ritual, Drama and Social Body in the Late Medieval English Town,” Past and Present no. 98 (February 1983): 1–29.

32. See Phythian-Adams, “Ceremony and the Citizen,” pp. 63–65; James, “Ritual, Drama and Social Body,” pp. 16–21.

33. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80; Richard Braithwait, The History of Moderation (London, 1669), pp. 10, 12, 15. See also John Wycliffe, On the Seven Deadly Sins, in John Wycliffe, Select English Works of John Wyclif, ed. Thomas Arnold, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1871), vol. 3, pp. 160–61; Edgeworth, Sermons, ff. 231v–232r; William Prynne, Healthes: Sicknesse or, a Compendious and Briefe Discourse, Prouing the Drinking and Pledging of Healthes to be Sinfull, and Vtterly Unloawfull unto Christians (London, 1628), p. 25; Samuel Ward, Woe to the Drunkard, in Samuel Ward, A Collection of Such Sermons as have beene written by S. Warde (London, 1636), p. 553; Brand, Popular Antiquities, vol. 2, pp. 338–39.

34. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80.

35. Turner, Ritual Process, pp. 94–95 and chaps. 3–5.

36. Ricart, Kalendar, p. 80.

37. Jacobus Voraigne, The Golden Legend; or Lives of the Saints as Englished by William Caxton, ed. F. S. Ellis, 7 vols. (London: J. M. Dent, 1900), vol. 7, pp. 1–31; S. Baring-Gould, Lives of the Saints: November, 2d ed. (London: J. Hodges, 1877), part 2, pp. 540–43; E. K. Chambers, The Medieval Stage, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1903), vol. 2, pp. 205–27, 393, 396–402; Joseph Strutt, Sports and Pastimes of the People of England from the Earliest Period, ed. J. Charles Cox (London: Methuen, 1903), pp. 201–3, 269; Brand, Popular Antiquities, vol. 1, pp. 411–14, 461–66; William Hone, The Every-Day Booke and Table Book, 3 vols. (London: T. Tegg, 1830), vol. 1, pp. 1501–8. See also Wright, British Calendar Customs, vol. 3, pp. 177, 179, 180–85; John Nurse Chadwick, “Rope makers’ procession at Catham,” Notes and Queries, 2d ser., 5, no. 107 (16 January 1858): 47; Charles Lamotte, Essay on Poetry and Painting (London: F. Fayram and J. Leare, 1730), p. 126; James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, Popular Rhymes and Nursery Tales (London: J. R. Smith, 1849), p. 238; John Noake, Notes and Queries for Worcestershire (Birmingham, Eng.: n.p., 1861), pp. 215–16; R. A[llies], “Worcestershire Folk-lore: Cathering and Clemening,” The Athenaeum 1001 (2 January 1847): 18.

38. John Bossy, “The Mass as a Social Institution, 1200–1700,” Past and Present, no. 100 (August 1983): 29–61; John Bossy, Christianity in the West, 1400–1700 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 64–72; see also Susan Brigden, London and the Reformation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), esp. chaps. 9, 14; Susan Brigden, “Religion and Social Obligation in Early Sixteenth-Century London,” Past and Present, no. 103 (May 1984): 67–112.

39. See Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981); Bossy, Christianity in the West, pp. 11–13, 72–73; Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century England (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), pp. 26–29, and cf. pp. 40–44; Scarisbrick, Reformation and the English People, pp. 12, 20, 39, 41, 54–55, 59, 170–71, 180; Collinson, Birthpangs of Protestant England, pp. 28–29, and cf. pp. 37–38, 50, 52–53; J. A. F. Thomson, “Piety and Charity in Late-Medieval London,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 16 (1965): 178–95; A. N. Galpern, The Religions of the People in Sixteenth-Century Champagne (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976), chap. 1; Alan Kreider, English Chantries: The Road to Dissolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979), chaps. 1–3. For the role of intercessory prayer in late medieval Bristol, see also Clive Burgess, “ ‘For the Increase of Divine Service’: Chantries in the Parishes of Late Medieval Bristol,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 36 (1985): 46–85; Clive Burgess, “A Service for the Dead: The Form and Function of the Anniversary in Late Medieval Bristol,” BGAS 105 (1987): 183–211; but compare Robert Whiting, “For the Health of My Soul: Prayers for the Dead in the Tudor South-West,” Southern History 5 (1983): 68–94; Whiting, Blind Devotion of the People, chaps. 3–4; Peter Heath, “Urban Piety in the Later Middle Ages: The Evidence of Hull Wills,” in Barrie Dobson, ed., The Church, Politics and Patronage in the Fifteenth Century (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984), pp. 209–34.

40. Lucy Toulmin Smith identifies this map as Bristol in 1479, but from the context it is clear that it is a view of Bristol as founded by the mythical Trojan “Brynne” or Brennus: see Ricart, Kalendar, pp. 10–11.

41. Werner Müller, Die heilige Stadt: Roma quadrata, himmlische Jerusalem und die Mythe vom Weltnabel (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1961).