III.

The Rigors of Thinking

But you deny that anybody except the wise man knows anything; and this Zeno used to demonstrate by gesture: for he would display his hand in front of someone with the fingers stretched out and say "A visual appearance [visum] is like this"; next he closed his fingers a little and said, "An act of assent [adsensus] is like this", then he pressed his fingers closely together and made a fist, and said that that was comprehension (and-from this illustration he gave to that process the actual name of katalepsis, which it had not had before); but then he used to apply his left hand to his right fist and squeeze it tightly, and forcibly, and then say that such was knowledge [scientia], which was within the power of nobody save the wise man—but who is a wise man or ever has been even they themselves [the Stoics] do not usually say.

—Cicero Academica 2.145

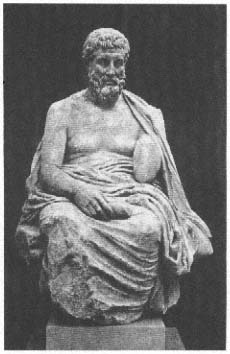

Among the terra-cotta figurines of the early third century are two new types depicting young men for which there are no parallels in earlier Greek art (figs. 51, 52). Both are seated, awkwardly hunched over, in contemplation. So lost in thought are they that they forget to sit up straight, even though the Greeks earlier attached great importance to correct posture. One of the two lifts his right hand to his cheek and looks wistfully to one side. The other props a heavy head on his chin, his whole body looking tensed from the strain of contemplation.[1]

The contrast between these and the typical image of the ephebe on Classical grave stelai is striking. Instead of allusions to athletic prowess or the handsome body in the perfect contrapposto pose, the quality now celebrated as a praiseworthy virtue of the well-bred youth is intense contemplation. The high social status of these young men is indicated by their clothing and the way in which they keep the left arm

Fig. 51

A contemplative young man.

Terra-cotta statuette. Paris, Louvre.

Fig. 52

Contemplative young man,

Terra-cotta statuette. Munich,

Antikensammlungen.

wrapped up in the garment. The later statuette, with the head propped on the chin, in particular makes it clear that thinking is regarded as hard work, requiring tremendous concentration and effort.

Such a departure from traditional iconography is usually not the invention of a coroplast, but rather inspired by the major arts. And indeed, an impressive statue of a philosopher in the Palazzo Spada in Rome, which derives from an original of the mid-third century, preserves almost the identical motif (fig. 57). Most likely the terra-cottas, which have been found in various parts of the Greek mainland, are a half century earlier than the prototype of the statue in the Palazzo Spada and are in turn dependent on another statue of a thinker of

which no large-scale copies have survived. The more important point, however, is that the terra-cottas demonstrate what a powerful impact the new statue types of the intellectual had on Greek society of the Early Hellenistic period. And, most interestingly, they show that the very act of intense contemplation was already considered a sought-after quality in the early third century. Otherwise images of this type would not have been adapted to the repertoire of the coroplasts, who specialized in such popular types as fashionably elegant women and adorable children.

In contrast to the citizen image of Athenian intellectuals of the fourth century, the portraits of third-century philosophers and poets present us for the first time with a series of images conceived specifically as those of intellectuals. These portraits do at last celebrate intellectual capacity or actually show the thinker at work. What is more, they differentiate between different kinds of mental activity. Thus poets are represented differently from philosophers, who in turn are distinguished according to their manner and temperament. It is in these portraits of the third century that the ancient philosopher first acquired his unmistakable countenance.[2] Indeed, the third century must be considered in general the most creative era in the portraiture of the ancient intellectual.

As always, the statue's message was expressed by the entire body. Even more so than with the formulaic citizen image, it is essential to know what kinds of bodies went with the impressive and innovative new portrait heads. Unfortunately, the state of our evidence is again extremely fragmentary. Nevertheless, we can gain a fairly complete picture for at least some of the major works. And again we must inquire into the specific context and function of each individual statue. Who was honoring each particular philosopher—the city or his own pupils, where did the statue stand, and to whom was its message principally directed?

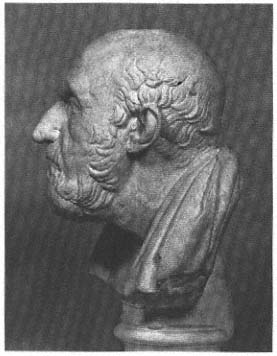

Zeno's Furrowed Brow

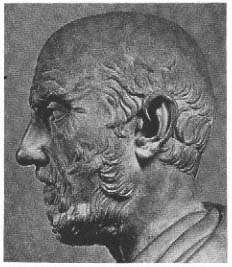

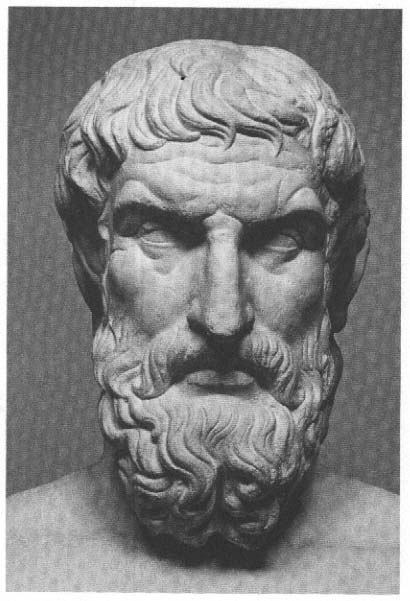

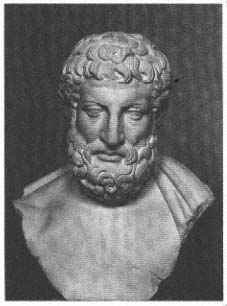

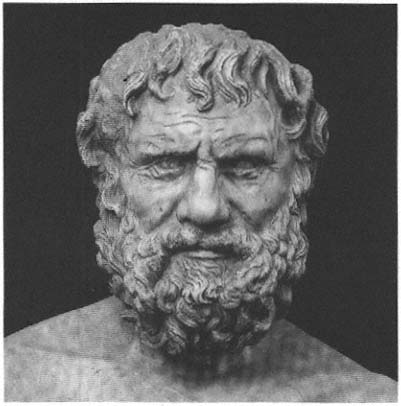

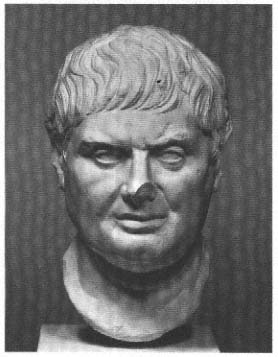

Let us look first at the Stoics. Their founder, Zeno of Kition in Cyprus, was apparently, like Socrates, far from a perfect physical speci-

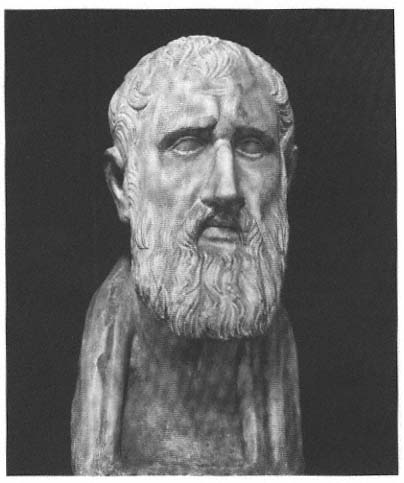

men. The sharp-tongued Athenians nicknamed the haggard and feeble Zeno "the Egyptian Vine" (D. L. 7.1). Diogenes writes: "He looked serious and severe, and his brow was always furrowed" (7.16; cf. Sid. Apoll. Epist. 9.9.14). Modern archaeologists, like the Romans before them, have naturally treated the surviving portrait, preserved in numerous copies (fig. 53),[3] as a shrewd character study of the supposedly sullen and inaccessible philosopher. But since this too was an honorific statue—and probably made at public expense—this is very improbable. Rather, the literary characterization of the frons contracta seems to be invented first in the Roman period, on the basis of the by then well-known statue, to reflect current interest in biographical and psychological traits.

In an honorary decree from Athens, passed on the initiative of the Macedonian king Antigonus Gonatas immediately after Zeno's death in 262/1, he is celebrated as a teacher of philosophy and educator of the youth. The Athenians here, interestingly, emphasize the fact that he actually lived by his own moral teachings—a revealing indication of just how skeptically they continued to view their philosophers:

Whereas Zeno of Citium, son of Mnaseas, has for many years been devoted to philosophy in the city and has continued to be a man of worth in all other respects, exhorting to virtue and temperance those of the youth who come to him to be taught, directing them to what is best, affording to all in his own conduct a pattern for imitation in perfect consistency with his teaching, it has seemed good to the people—and may it turn out well—to bestow praise upon Zeno of Citium, the son of Mnaseas, and to crown him with a golden crown according to the law, for his goodness and temperance, and to build him a tomb in the Ceramicus at the public cost. And that for the making of the crown and the building of the tomb, the people shall now elect five commissioners from all Athenians, and the Secretary of State shall inscribe this decree on two stone pillars and it shall be lawful for him to set up one in the Academy and the other in the Lyceum. And that the magistrate presiding over the administration shall apportion the expense incurred upon the pillars, that all may know that the Athenian people honour the good both in their life and after their death.

(D. L. 7.10–12, trans. R. D. Hicks)

Fig. 53 a–b

Zeno of Kition (ca. 333–62). Inscribed bust. Roman copy of a statue

presumably set up after his death. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

There follow the names of the members of the commission. In other words, the polis in this way clearly recognizes and defines both the achievement of the Stoic who taught publicly, in the Agora and the gymnasia, and his own role in society. The contemporary designation of his school as the "Stoa" clearly expressed its public nature. The Stoa

Poikile, famed for its fifth-century paintings, was a columned portico fronting directly on the Agora, in which Zeno and his successors often taught, in plain view and accessible to all. This public instruction is also recorded in the erection of the two stelai carrying the decree in the Lyceum and the Academy, the two most important gymnasia in Athens. The portrait statue of Zeno mentioned by Diogenes Laertius (7.6) could have stood in one of these places as well, though this is not a part of the popular decree. Perhaps the statue was an initiative of Antigonus Gonatas himself, who had heard Zeno lecture, tried to lure him to his court, and surely considered himself a pupil.[4] The portrait preserved in the copies could reflect this very statue.

In the context of such a portrait, intended to honor the subject, the powerful contraction of the muscles in the brow can carry only a positive connotation, that is, it must signify effortful and concentrated thinking. The sculptor has made this all the more obvious by leaving the rest of the face, with the conventional features of old age, rather

bland, thereby focusing all our attention on the brow. With its long aquiline nose, the strongly modeled face projects forward, like a ship's prow, giving the impression of tremendous energy.

The image projected is that of a mighty and original thinker whose energy is irresistible. The reason for the powerful visualization of the rigors of thinking should probably be sought in Zeno's insistence on the importance of strenuous effort in the process of recognition and on the scientific evaluation of sensory impressions. The rigor of the characterization stands in striking contrast to the manner of such Late Classical portraits as that of Theophrastus (see fig. 43) and goes even beyond Demosthenes' expression of mental concentration (see fig. 49). Whereas the latter represents a momentary concentration in a particular situation, Zeno's brow seems to stand as a timeless symbol for the thinking process. One would like to know how this conception came about—whether, for example, the sculptor was advised by Zeno's friends and pupils. But unfortunately we do not even know who commissioned the statue.

In comparison with the later portrait of Chrysippus (figs. 54–56) and the Stoic image of the anticitizen, displaying his poverty and disregard for his own body, Zeno's appearance is remarkable for the proper styling of his traditional coiffure, with locks combed forward and evenly over the crown to cover his baldness. He must have intended, through his appearance, to distance himself clearly from the Cynics.[5] The severe and sharply contoured beard, however, could be a particular idiosyncrasy, as we shall later see.

Unfortunately, no copy of the body that went with this portrait has yet turned up. But when we recall the statue of Demosthenes, we will surely want to complete Zeno's face, deep in concentration, with an equally tensed body. But whether it was a seated or a standing statue is not clear from the contradictory indications provided by the preserved busts. Nevertheless, a seated figure seems to me preferable, on the basis of the bronze bust in Naples showing the head projecting forward and part of the drapery.[6]

Zeno referred to his pupil Kleanthes as a second Herakles (D. L. 7.170). The hero who had to struggle through all his labors, as the

post-Classical age imagined him, was a favorite figure with the Stoics. Kleanthes, who learned only with difficulty, was in turn a favorite of Zeno's, even though others made fun of him for being slow to catch on, because he "held fast what he had won through a great effort in an iron memory." He had earlier competed as a boxer (his pupil Chrysippus was said to have been a runner) and, while a student of Zeno's, worked nights fetching water from the fountains in the Gardens. The embellishment of Stoic biographies with such anecdotes affords us a glimpse into the style and self-image of Zeno's school. The notion that thinking always requires great effort and constant struggle was evidently understood in a most positive sense and thus expressed itself both in the metaphorical use of language and in visual analogies employed by the Stoics. We need only recall Zeno's well-known and later on still-popular image of the clenched fist, which holds the laboriously gained truth in an iron grip (Cic. Acad. 2.145), or of Kleanthes' fingers worn to the bone from nervously rubbing them together while thinking (Sid. Apoll. Epist. 9.9.14).[7]

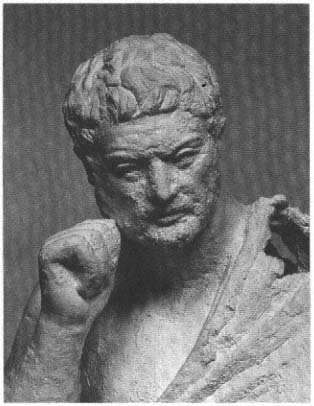

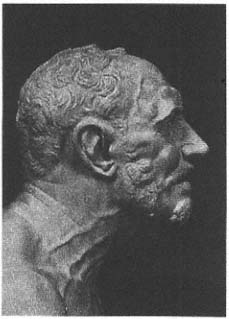

Chrysippus, "The Knife That Cuts Through the Academics' Knots"

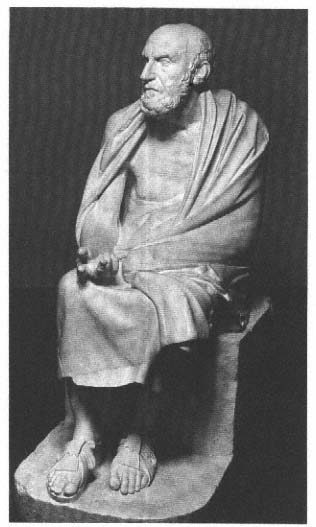

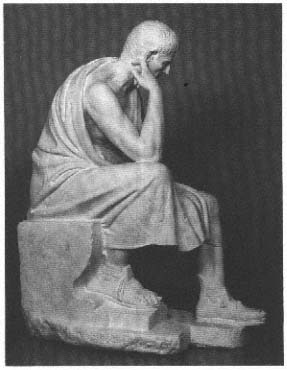

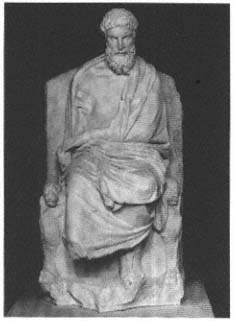

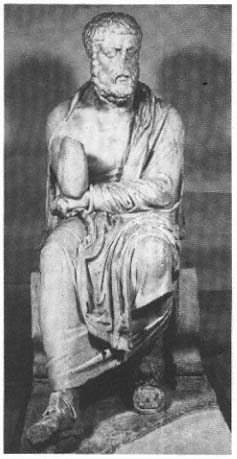

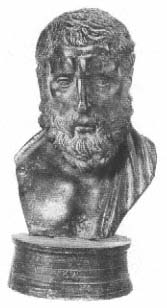

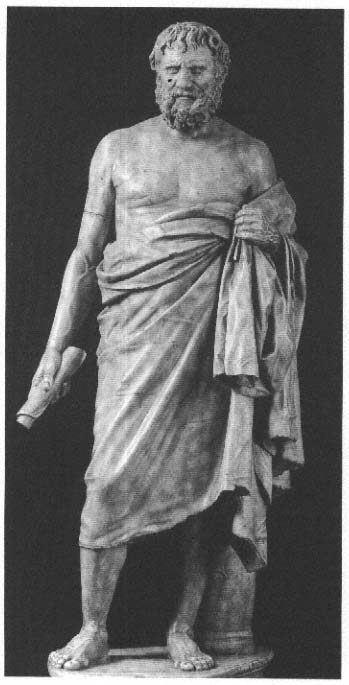

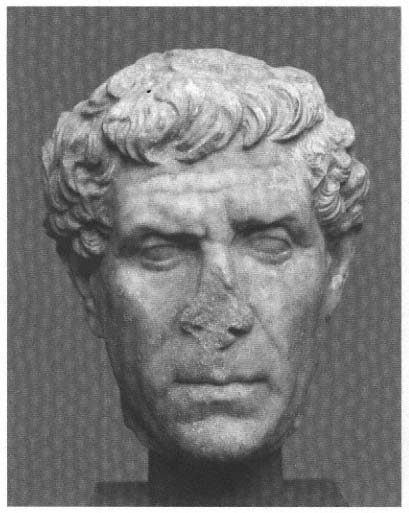

It is in the portrait of the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus that the notion of thinking as hard work found its most extraordinary expression. The seated statue (fig. 54a, b) is preserved in one good copy of the body and many of the head and was probably put up immediately after the death of Chrysippus (ca. 281–208 B.C. ).[8] An elderly man, his back bent over with age, he sits on a simple stone block, that is, in a public place, the Agora or one of the gymnasia. Like an old man, he has drawn up his feeble legs and is trying to pull the garment tighter around his bare shoulders against the cold. Even in old age, the hardened Stoic, wanting nothing, refuses any comforts, such as a backed chair or an undergarment. But inside this frail, almost pitiful body—notice especially the sunken chest—resides an invincible, feisty spirit. The artist's intention is to show how the power of the spirit triumphs over the weaknesses of the body.

Fig. 54 a–b

Chrysippus (ca. 281–204). Reconstruction of a

statue presumably set up after his death. Munich,

Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke.

The philosopher's projecting head collides with an imaginary opponent (fig. 56). The left hand, under the mantle, is clenched in a fist, while the right is extended in argument, the fingers perhaps ticking off in order his winning points. In a manner characteristic of most Early Hellenistic art, the viewer is drawn into the pictorial space and becomes, as it were, the philosopher's interlocutor.[9] The gesture of the outstretched right hand, to which Cicero specifically refers, accompanying the energetic thrust of the head, seems to be an individual characteristic of Chrysippus. More than just an aggressive speaking style, it represents a particular form of thinking, that is, argumentation and logical deduction. It was in this sphere that Chrysippus, the great dialectician, was considered superior to all his contemporaries. An epigram composed by his nephew Aristokreon celebrates him as the knife that cuts through the Academics' knots." The epigram was

carved beneath one of the several statues of Chrysippus in Athens that are attested in our sources (Plut. Mor. 1033E).[10]

This is not a rhetorical gesture of the master teacher, but rather the effort of direct confrontation with an interlocutor who has to be won over. Only the arguments count, and the old man must expend his last

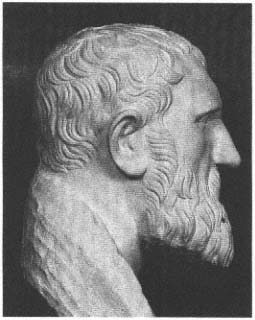

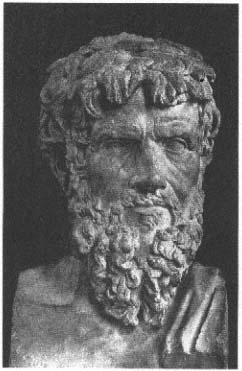

Fig. 55

Bust of Chrysippus. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

ounce of strength to put his winning point across. In contrast to the generalized formula for thinking expressed in Zeno's mighty brow, the face of Chrysippus reflects the immediacy of a momentary mental effort. Like the whole body, the muscles of the brow are shown in a powerful and spontaneous motion (fig. 55). We are meant to see how ideas and arguments are brought forth by the old man's strenuous efforts. When we come to compare the detached portraits of the Epicureans (fig. 62), it will become even clearer that for the contemporary viewer who frequented more than one philosophical school this Stoic image must have embodied a highly polemical stance toward the rival schools.[11]

The statue of Chrysippus was also most likely a public honorary monument, and, like Zeno, he was honored with a public burial (Paus.

Fig. 56

Bust of Chrysippus. London, British Museum.

1.29.15). He had, after all, given instruction tirelessly in public for decades. No fewer than three statues are attested in Athens, two of them in or near the Agora. Pausanias mentions one "in the Gymnasium of Ptolemy at the Agora" (1.17.2), and Cicero saw the other, a seated statue, "in Ceramico . . . porrecta manu" (Fin. 1.39), probably at the northern entrance to the Agora, which was thick with honorific monuments. Diogenes Laertius (7.182) knew the same statue, which, based on the descriptions, is probably the one preserved in the copies.

The statue, like the honorary decree for Zeno, thus celebrates Chrysippus as a teacher, as a man from whom one could learn to think and to argue. At the same time, the statue's ethical claims, the message concerning attitudes toward the body, also has a didactic intent. The statue called to mind a man who, into old age, was still active in the Agora and the gymnasia. "He was the first who had the courage to

hold his lectures in open air in the Lyceum" (D. L. 7.185). In so doing, he made his arguments not only in words, but with the example of his own way of life, especially his toughness and freedom from bodily necessities. He had turned his own body into a paradigm, to paraphrase the text of the decree for Zeno. Naturally the average young Athenian could no longer see in such a figure an actual role model, but only those who became his disciples and devoted themselves to philosophy. We are presented here with a leading thinker, a powerful mind and a strong conscience, but no longer a model citizen upholding the norms of the democratic state, as had been the case with the mantle-clad poets and philosophers of the fourth century.

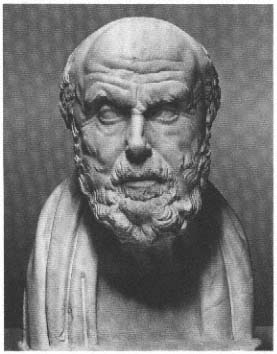

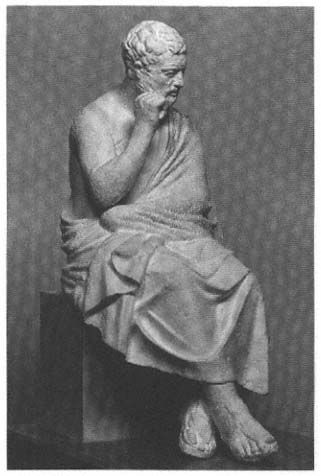

The Thinker's Tortured Body

The portrait of Zeno and the statue of Chrysippus are the only images of Stoic philosophers of the third century that can be identified with certainty. But there exist other portraits based upon the concept of thinking as a strenuous and laborious undertaking. For our purposes, it is not so crucial whether these actually represent Stoics, philosophers related to the Stoics, or even scholars of other kinds. Rather, we are concerned with particular paradigms for intellectual activity, as they developed at particular periods in time and were then translated into visual imagery.

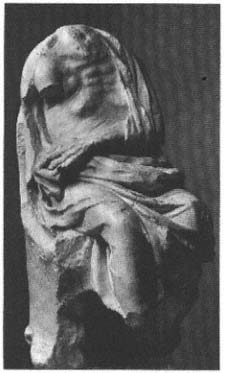

The badly damaged statue of a philosopher now in the Palazzo Spada, found without its head, was skillfully restored in the seventeenth century and completed with an ancient head that did not originally belong to it (fig. 57).[12] The baroque sculptor chose a portrait head with a pronounced "thinker's brow" to complement the pose of the statue, but unfortunately it belongs to the Early Imperial period. The motif of a man completely lost in his own thoughts, bending over and staring out, which we have already encountered in Early Hellenistic terra-cottas, has here taken on a new, more dramatic quality. The philosopher sits unobserved on a stone bench with carved, two-stepped base. To the ancient viewer this would signal an association with the gymnasium. The subject has drawn the crude mantle carelessly across his body. His legs are placed far apart in an almost unseemly pose,

Fig. 57

Statue of a seated philosopher. The Roman portrait

head does not belong. Copy of a statue ca. 250 B.C.

Rome, Palazzo Spada. (Cast.)

especially when compared with the dignified manner of the seated Epicurus (fig. 62). This is further emphasized by setting the right foot on the upper profile curve of the bench. In the bronze original, this foot probably rested only on the heel, to convey a restless, swinging motion of the leg, the psycho-motor expression of the inner tension of the thought process. (The copyist, who was understandably concerned to protect the front part of the foot, has added a stone ledge that serves no other purpose and so spoils the composition.) The right arm is drawn toward the head, with the elbow resting squarely on the agitated leg. Nor is the left arm propped calmly on the thigh; it is caught in an involuntary movement, with the hand clenched in a fist underneath the garment, like that of Chrysippus. Tension permeates

Fig. 58 a–b

So-called Kleanthes. Bronze statuette after a portrait of an

unidentified philosopher ca. 250 B.C. London, British Museum. (Cast.)

the entire body. The hand and the head have probably been correctly restored by the baroque sculptor. At any rate, the head must, like those of Zeno and Chrysippus, have expressed above all the strenuous effort of thinking.

The basic conception reminds one of the famous and ubiquitous Thinker of Rodin. The difference is that the ancient philosopher does

not in desperation look upon the abyss of Hell or the void. On the contrary, his mental efforts are presented as something praiseworthy, as a nearly Herculean labor. It is striking that this old man with the wrinkled belly has such powerful shoulders and arms. Various identifications have been proposed, on the basis of a fragmentary inscribed name, of which only ARIST . . . can be made out. So far no solution to the puzzle is possible. The motif of mental effort would indeed suit a Stoic, yet we should note another aspect. This is evidently a solitary thinker, a new kind of paradigm, which hardly seems appropriate for a teacher.

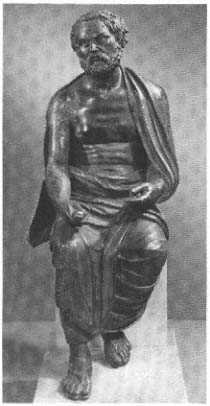

A related work of the same period, unfortunately preserved only in small-scale copies, is a seated statue (fig. 58a) that Schefold wanted, on

the basis of the gesture, to identify (though without conclusive arguments) as Kleanthes of Assos (331–232 B.C. ), the favorite pupil and successor to Zeno, of whom we have already heard.[13] The artist who created this statue was once again primarily interested in a careful observation of certain psycho-motor reactions of the human body in a state of extreme mental concentration. Only a bronze statuette in the British Museum gives some idea of the lost original. It renders the powerful and fleshy body and the full face of a man who has not yet reached old age (fig. 58b).

At first glance, this thinker seems to be comfortably seated with his legs crossed. But in reality, he too is completely caught up in his intellectual effort. Like the Spada philosopher (fig. 57), he is oblivious of his surroundings, and the act of thinking has tensed his entire body, removing him from the world around him. Both arms are caught in spontaneous and unconscious motion. The left pushes and pulls the garment to the side, while the right seems not so much to support the head as to push it to one side. The fabric of the mantle, which had been properly draped, has as a result slipped to the side. Both hands make a fist, and the feet are nervously entwined and pressed against each other. As in the case of the Spada philosopher, this uncontrolled motion is emphasized by a particular detail, the left foot resting in an extremely precarious manner, with only the edge of the sandal's sole touching the ground. In other words, the right foot has been moved up and down by the agitation of the left foot.

If we recall the pose of Euripides and of the elderly men on Late Classical grave reliefs (figs. 31, 32), it will be clear just how flagrantly these two seated statues flout the conventions of proper civilian dress. In both instances, the artist employs a carefully observed body language in order to visualize an inner tension and agitation. In the face of the bronze statuette, mental concentration is expressed not only by the contraction of the eyebrows and forehead, but in addition by the open mouth. One might be tempted to take the short and closely trimmed beard, similar to that of Chrysippus, as an argument for identifying the subject as a Stoic, but there are too few reliable copies to permit a specific identification.

It was only natural that this new image of thinking as a laborious

Fig. 59

Relief with the figure of the mathematician and astronomer

Eudoxus (ca. 408–355), his body bent over. Budapest,

National Museum. (Cast.)

process that manifests itself in the entire body also affected the visual imagery of famous intellectuals of the past. When, in the following chapter, we consider the emotional, sometimes almost violent facial expressions of these portraits of thinkers, we shall have to imagine them combined with correspondingly agitated bodies. Unfortunately, there are very few copies of the bodies that went with such portraits preserved in Roman decorative art. One exception is a statuette of Antisthenes from Pompeii, who sits with the legs tensed and, like Demosthenes, holds his arms still with hands clasped. But this type is probably not derived from a public honorific statue.[14] A particularly impressive example is the famous mathematician and astronomer Eudoxus of Cnidus (fourth century B.C. ), who broods on his equations on a relief fragment of Early Imperial date (fig. 59).[15] His arms clasped and legs crossed, he sits leaning far forward on a simple block of stone, like the statue of Chrysippus. His right hand reaching out could have

held a staff with which he drew in the sand. The compact and somewhat cramped composition seems to be derived from a statue of the Middle Hellenistic period. Modest works like this one are particularly valuable, because they give us at least some idea of the variety of body types and poses that could be employed to express the notion of concentrated and strenuous mental effort.

Chrysippus' Beard

I should like to return once more to the Stoics, and in particular to Chrysippus' beard. But first, a word about philosophers' beards in general. As we have seen, Athenian intellectuals of the fourth century, like all other adult men, wore a beard. Shaving first came into fashion with Alexander the Great. In Athens, it was thus probably the pro-Macedonians who were the first to adopt the fashion, while traditionalists and democrats did not. By the early third century, when being clean-shaven had become the norm, a beard must of necessity have taken on connotations such as "conservative" and "political outsider." The Hellenistic kings and their courts, I believe, all adopted the new fashion.[16] But the philosophers had an additional reason for wearing a beard. It is a law of nature that hair grows on a man's chin, and to shave it off is a denial of the natural order of things. A man who shaved, so they believed, also gave himself a soft and unmanly appearance. The clean-shaven look was effeminate and raised suspicions of sexual lust and a weakness for luxury. Significantly, Alcibiades had been one of the first to shave and also wore his hair in long locks.[17] By chance, we know verbatim Chrysippus' own argument on this point, from his treatise On the Good and Pleasure:

"The custom of shaving the beard increased under Alexander, although the foremost men did not follow it. Why, even the flute-player Timotheüs wore a long beard when he played the flute. And at Athens they maintain that it is not so very long ago that the first man shaved his face all round, and had the nickname Shaver." "For really, what harm do our hairs do us, in the gods' name? By them each one of us shows himself a real man,

unless you secretly intend to do something which conflicts with them."—"Again, Diogenes, seeing a man with a chin in that condition, said: 'It cannot be, can it, that you have any fault to find with nature because she made you a man instead of a woman?' And seeing another person on horse-back in nearly the same condition, reeking with perfume and dressed in a style of clothing to match these practices, he said that he had often before asked what the word horse-bawd meant, but now he had found out. At Rhodes, although there is a law which forbids shaving, there is not so much as a single prosecutor who will try to stop it, because everybody shaves. And in Byzantium, although a fine is imposed on the barber who has a razor, everybody makes use of one just the same." These, then, are the remarks of the admirable Chrysippus.

(Ath. 13.565, trans. C. B. Gulick)

In the face of the new fashion for shaving, which the visual evidence suggests quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean,[18] the philosophers clung to their now old-fashioned beards, as far as we can tell, without exception. In the early years of the third century, a poet of New Comedy, Phoinikides, already speaks of "the philosophers who wear beards [pogon' echontes ]" (frag. 4),[19] implying that the majority of men were by this time clean-shaven.

It was in these circumstances that the wearing of a beard, combined with certain hairstyles, clothing, and modes of behavior, first came to symbolize the "otherness" of the philosophers. Their appearance clearly defined them as a conservative group, standing in opposition to their own age and legitimating their stance with an appeal to the "customs of old." They make claim to a higher (because older) form of wisdom and use this to challenge their contemporaries. This appeal to the past was to become a consistent element in the imagery of ancient philosophers, reaching all the way to late antiquity.

At the same time, the beard becomes the favorite object of ridicule. In principle society recognizes the role of the philosopher as moral authority, yet in times of doubt or crisis that authority is always questioned. Does the beard really suit the philosopher? In other words, does he really practice what he preaches? The decree for Zeno had explicitly asserted this congruity between the claims of the educator,

on the one hand, and a moral way of life, on the other. During the Roman Empire, the beard became the symbol of the philosopher's moral integrity. In the time of Marcus Aurelius, the Athenians had reservations about awarding a chair in philosophy endowed by the emperor, to an otherwise eminently qualified Peripatetic, simply because he had difficulty growing a beard. The situation was considered so grave that the decision had to be left to the emperor in Rome (Lucian Eun. 8ff.).[20]

Though all philosophers wore beards, they wore them in different styles: trimmed or not; full length, half, or short; carefully tended or unkempt. Already in the third century, it seems, one could recognize what school a philosopher belonged to, and his way of thinking, by the state of his beard and hair. From here on, one's beard and hairstyle became a statement of the philosophical teachings one accepted and, as a rule, by extension, of a certain way of life. The symbolic values of hair and beard that arose in the third century B.C. remained in effect well into the Imperial period. Alciphron, a writer of the second century A.C. , describes the appearance of a group of Attic philosophers at a birthday party, at which they would later behave rather badly:

So there was present, among the foremost, our friend Eteocles the Stoic, the oldster, with a beard that needed trimming, the dirty fellow, with head unkempt, the aged sire, his brow more wrinkled than his leathern purse. Present also was Themistagoras of the Peripatetic school, a man whose appearance did not lack charm and who prided himself upon his curly whiskers. And there was the Epicurean Zenocrates, not indifferent to his curls, he also proud of his full beard, and Archibius the Pythagorean, "the famed in song" (for so everybody called him), his countenance overcast with a deep pallor, his locks falling from the top of his head clear down to his chest, his beard pointed and very long, his nose hooked, his lips drawn in and by their very compression and firm closure hinting at the Pythagorean silence. All of a sudden Pancrates too, the Cynic, pushing the crowd aside, burst in with a rush; he was supporting his steps with a club of holm-oak—the cane was studded with some brass nails where the thick knots were, and his wallet was empty and hung handy for the scraps.

(Alciphron 19.2–5, trans. A. R. Benner and F. H. Forbes)[21]

The preserved portraits in general bear out Alciphron's witty characterizations, though we must bear in mind that the particular features of each individual school may have changed in the course of time. The Stoics are regularly described as being unkempt, with short and uncombed hair. It is not, however, explicitly attested that they wore their beards close cropped, like Chrysippus. But this is easily explained by the same reasoning that the Stoic Musonius gives for cropping the hair as a "pure functionality." That is, one interferes with a natural process only when, for whatever reason, it becomes a hindrance (Diatr. 21). In contrast to the Peripatetics, who wore carefully trimmed beards, the Stoics rejected the very idea of such attention; likewise any other kind of care for the body, as in the tradition of the Cynics, because this represented a distraction from thinking and exalted the body. It is better to cultivate one's understanding than one's hair, according to Epictetus, who cites Socrates in this context (Diss. 3.1.26; 42). Since neatly styled hair and trimmed beard were of great concern to the Peripatetics, the Academics, and the Epicureans, the close-cropped and uncombed hair and unkempt beard of the Stoics were a polemical statement and made clear that they despised as unmanly any kind of attempt to beautify the body. This may indeed be the meaning of Zeno's untended and jagged beard with its exaggerated angles (cf. p. 96).

In the case of Chrysippus, however, the beard has a more particular ethical message that seems to allude to a specific element of Stoic teaching. What I have in mind is a seemingly incidental detail that was overlooked by some ancient copyists, as well as by modern scholarship. The close-cropped beard not only gives the impression of being unkempt, like his hair, but it seems to grow rather irregularly. In some places it is quite sparse, yet ugly bushy patches grow in other places where one would not expect any growth (fig. 60).[22] This peculiar pattern had a set of quite specific connotations and associations among Chrysippus' contemporaries that are distinctly negative.

Pseudo-Aristotelian physiognomic writers compared men whose beards grew like this with apes, "disgusting, ridiculous, and evil animals." For this reason, as H. P. Laubscher has pointed out, fishermen, peasant farmers, and slaves—in short, all those who were looked down

Fig. 60

Chrysippus. Rome, Vatican Museums.

on by a society of freeborn citizens—are depicted with such irregular growth of beard (fig. 61), as also, in the mythological sphere, the wild and uncivilized satyrs.[23] In this way they are characterized as morally inferior. Thus for Chrysippus to emphasize his irregular growth of beard by cutting it short, instead of trying to conceal it, and for his friends to have him portrayed after his death with such a morally loaded imperfection, in the context of these well-established physiognomic conventions, could imply only a deliberate response to the prejudices of society. Slaves and peasants are human beings too, the beard proclaims; social categories are purely random and do not exist for the philosopher. Furthermore, nature makes a man's beard grow one way or another; however it grows is right and has nothing to do with his character or morals. The first portrait of Socrates had similarly represented an opposition to the norms of kalokagathia (p. 38). Chrysippus' attitude assigns hair and beard and everything associated with them to the adiaphora, that is, things that in Stoic doctrine are neither good nor bad in and of themselves.

Fig. 61

Head of the "Old Fisherman." Roman copy of a

third-century B.C. statue. Paris, Louvre.

The very fact that well-known Stoic teachings and ways of life were incorporated, in such detail, into the portrait itself must mean that knowledgeable people had some say in determining the conception of this statue. Evidently Chrysippus' pupils used the portrait as a vehicle for propagating the missionary work of their teacher.

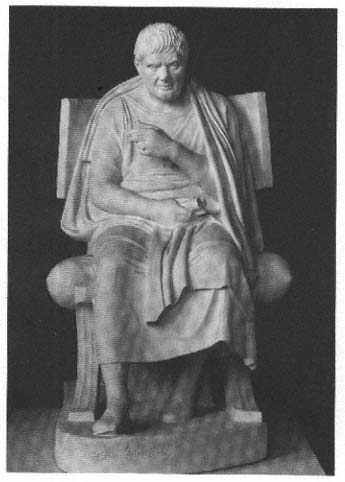

The "Throne" of Epicurus

The situation is entirely different when we come to the portraits of the Epicureans. They never taught publicly but instead withdrew to Epicurus' garden outside the city the Kepos, to live together—more like a gathering of friends, a commune, or a sect than a school—seek-

ing the path to happiness and pleasure without disturbance and fear, under the guidance of a teacher of surpassing insight. The goal was a life of "joy and pleasure" by reaching a state of "painlessness of the body" and "lack of excitement of the soul." In Athens the disciples of Epicurus were so closely identified with a life outside the community of the polis that they were often referred to simply as "those from the Garden" (Sext. Emp. Math. 9.64). It is therefore highly improbable that any public statues were put up in the third century in honor of these men who so ostentatiously withdrew from the civic and political life of the city. More likely, the portraits stood in the Kepos itself, at least in the early period, and served there to recall Epicurus and his friends Metrodorus, Hermarchus, and Polyaenus, who were also known as "guides" or "leaders" (kathegemones ) and enjoyed the particular devotion of pupils who were referred to as kataskeuazomenoi .[24] The existence of a well-known "mnema of the Epicureans" in the Kepos is explicitly attested (Heliod. Aeth. 1.16.5).

We are fortunate to possess copies that give a good idea not only of the statue of Epicurus, but of those of his friend Metrodorus and his successor Hermarchus. Probably all three were put up soon after the subject's death, in 277 (Metrodorus), 270 (Epicurus), and 250 (Hermarchus).[25]

If we take a look at these three Epicurean statues (figs. 62–64), on the one hand (they are all more or less fully preserved in copies or can be reconstructed), and the statue of Chrysippus (cf. fig. 54), on the other, it is immediately clear both how closely all the Epicureans adhere to the same manner of pose and appearance and how fundamentally different these are from the image of the Stoic. Instead of the Stoic expression of mental strain and the hunched-over body, all three Epicureans sit calmly and quietly in classically balanced poses, the mantle carefully draped about them.

Even when seated they maintain a kind of contrapposto between the rear leg actively thrust back and the forward leg relaxed, as well as a comparable chiastic positioning of the arms. For them, evidently, thinking is not such hard work that it would be reflected in the body. The display of conventionalized standards of behavior, as in the citizen image of the fifth and fourth centuries, comes naturally and effortlessly. This is particularly noticeable in the statues of Epicurus and

Fig. 62

Epicurus (ca. 342–270). Reconstruction by K.

Fittschen of the statue presumably set up after his

death. Göttingen University, Abgußsammlung.

Hermarchus in the prescribed wrapping up of the left arm. This correct, though rather "public," posture hardly seems to suit the private image of a man quietly seated in contemplation and presents in any event a striking contrast to Chrysippus' intense concentration on intellectual pursuits or the psycho-motor tension and movement of statues related to that of Chrysippus.

This unmistakable gesture of the Epicureans can be understood only as an explicit and self-conscious indication of a desire to hold to the old traditions, a token of virtue and modesty, at a time when these very values were being called into question by other members of Athenian society. Epicurus and his friends quite ostentatiously attach great importance to the proper behavior. Anyone who withdrew from the

Fig. 63

Metrodorus (ca. 331–277). Reconstruction of a

statue set up after his death. Once Copenhagen,

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

city, like "those from the Garden," was well advised to insure that in spite of this he appeared to be an irreproachable citizen. Indeed, Epicurus by no means rejected the rules of society but rather understood them as the prerequisite to a philosophical life of inner happiness. The maintenance of the proper citizen etiquette was taken for granted in the Kepos.[26]

The elegant wavy hair of Epicureans, the locks carefully arranged on the forehead, and especially the strikingly "classical" stylization of their beards (figs. 66–68) all demonstrate how important they considered a cultivated appearance that was based on the ideals of the past. The wearing of a beard—even a carefully tended beard like those of

Fig. 64

Hermarchus (born ca. 340). Underlife-size

Roman copy of a statue ca. 250 B.C.

Florence, Museo Archeologico.

respectable Athenian citizens of an earlier age—had by now become a token of otherness. And yet the handsome Epicurean beard conveys a very different set of values from the unkempt or crudely trimmed beard of the Stoics, not to mention that of the Cynics. For the Epicureans, the beard implies not only an acceptance of the traditions of the polis, but also an identification with the upper class.

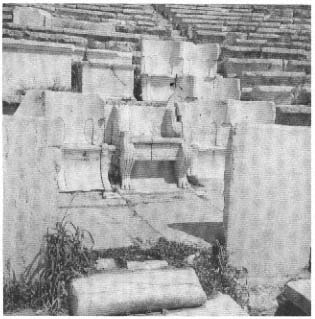

While at first glance the three statues of Epicureans look very similar, there are in fact important differences, which reflect the strict hierarchy that obtained in the Kepos. Epicurus sits on an impressive "throne," Metrodorus on a backed chair, and Hermarchus on a simple stone block.[27] Some have likened Epicurus' chair, with its ornamental lion-paw feet, to the thrones of the gods, and thereby linked it to the hero cult that was established for the founder of the Kepos after his death. This seems to me, however, unlikely, since Epicurus himself is not depicted as a hero, but in every respect as an Athenian citizen. For a contemporary viewer, a more obvious comparison would be with the prohedria (the front-row seats) in the Theatre of Dionysus, reserved for priests and outstanding citizens, as well as for benefactors of the city. The association would have suggested itself on account of the shape of the seat (fig. 65), especially since the elaborate seat of the priest of Dionysus, with its lion-paw feet, in the middle of the front row, stood in the same relation to the other seats of honor as Epicurus' throne to the backed chair of Metrodorus. The Kepos has thus usurped this symbol of signal public honor for officials and dignitaries, in order to mark Epicurus' achievements and his position within the school. In this way the great wise man, who showed the way to a happy life, was singled out by his pupils as the highest spiritual authority.[28]

Another conceivable association would be that of an academic "chair." As early as the time of the Sophists, an especially impressive seat seems to be a sign of the instructor's special authority and dignity. Plato portrays the Sophist Hippias of Elis giving instruction from a thronos, while his pupils sat around him on stone benches (Prt. 315). But, as we shall see, Epicurus is in fact not shown as a teacher giving instruction, so that the connotation of the academic chair is unlikely.

Against the background of the Classical image of the Athenian citizen, this kind of honor represents something new. The singling out of Epicurus from the other two kathegemones makes it clear that the Epicureans were not concerned with a search for truth through persuasive argumentation and passionate discussion, like the followers of Chrysippus, but rather with devotion to and perpetuation of a unique spiritual guide and teacher.

Fig. 65

Honorary seats in the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens.

The same hierarchy can also be clearly detected in the faces of the three portraits. Epicurus' is marked by a curious contrast between the restless and powerfully muscled philosopher's brow and the otherwise placid expression of the face (fig. 66). Yet the brow is still different from, say, Zeno's or Chrysippus', where the mental effort looks forced and strained. Epicurus' eyebrows are raised, but hardly in motion. The raised brows are a token of superiority, reflecting his absolute authority. The powerful muscles above the brows can therefore not be understood as an expression of a momentary mental struggle, especially when the body is so relaxed. Apparently the sculptor wanted to express the idea of tremendous intellectual capacity, a state of being rather than a sudden action.[29]

Metrodorus' brow, on the other hand, does not betray even a trace

Fig. 66

Epicurus on a double herm with Metrodorus. Rome, Capitoline Museum. (Cast.)

Fig. 67

Bust of Metrodorus. Rome, Capitoline

Museum. (Cast.)

Fig. 68

Small bronze bust of Hermarchus.

H: 20 cm. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

of intellectual effort (fig. 67). Rather, its serenity, lack of expression, and perfect balance strike us more as an echo of Classical citizen portraits. This was, it would seem, precisely the intention. The Classical formula for characterizing a distinguished man in middle age is taken up and quoted, in order to make visible certain goals of Epicurus' teachings, such as inner tranquility and a life of enjoyment. In this way, the carefully tended hair and beard, as well as the elegant manner of dress and seated posture forge an association with the polis values of the past.[30]

With Hermarchus, however, we do seem to sense a measure of mental strain, or perhaps, concern (fig. 68). In the better copies, the brows are gently drawn together, and the wide fringe of hair emphasizes the severity of this portrait of old age. Like Epicurus, Hermarchus was a native of Mytilene on Lesbos, and they had come together to Athens

and there lived and philosophized together for more than forty years. Hermarchus was thus already an old man when, after Epicurus' death, he became head of the Kepos and devoted himself to preserving his friend's heritage as faithfully as possible.[31]

Hermarchus' dress and pose (cf. fig. 64), as we have seen, deliberately imitate those of Epicurus, but with an important difference in the pose of the head and probably also of the right arm. Hermarchus' raised arm is a gesture of teaching, and his head is raised and turned to the side, as if toward an interlocutor. Epicurus, by contrast, bent his head and looked out in front of him, as Fittschen's reconstruction with casts has confirmed (fig. 62). The lower right arm, like Metrodorus' left, was gently drawn back toward the body and turned inward. The drooping shoulder also suggests a quietly relaxed positioning of the arm.[32] We may infer from this difference that Hermarchus was shown more as the teacher, Epicurus as the tranquil thinker marked by inner concentration. This in turn reflects the different roles that they played: Epicurus is the great pioneering thinker, remote and unattainable on his seat of honor; Hermarchus, the loyal disciple who preserves and propagates the inheritance of the master.

Bodies, Healthy and Unhealthy

The portrait of Epicurus displays yet another "individual" characteristic. His body, especially those parts of it that are exposed, is rendered as extremely feeble. This is particularly exaggerated in a small statuette in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome (fig. 69).[33] But even in the fine copy of the statue in Naples, the body is flabby and unarticulated in a manner unknown in any other statue type. If the statues of the three philosophers did indeed stand alongside one another in the Kepos, this trait of Epicurus must have been especially noticeable. It is probably meant as a reference to the long, debilitating illness of Epicurus' later years. But again, it is not intended so much as a biographical trait, but rather as a sign of the exemplary and virtuous way of life. The equanimity with which the master not only endured his pain to the end but overcame it through the memory of his earlier happiness

Fig. 69

Small-scale copy of the portrait of Epicurus.

H: 23.5 cm. Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori.

was much admired by his friends and pupils, who saw him as proof that the truly wise man who follows Epicurus' teachings can attain ataraxia and eudaimonia (peace of mind and happiness) even in the most difficult circumstances (D. L. 10.22).

Metrodorus' relaxed and ample body (fig. 63), on the other hand, looks like the embodiment of a life of pleasure. As we have already observed of the head and masklike face, his body also represents a masculine ideal of Classical art, here expressing well-being, serenity, and conviviality with one's fellow man. The comfortable backed chair on which he sits, like that of Menander and Poseidippus, suggests a pleas-

ant domestic ambience. Metrodorus is completely at ease, leaning back comfortably and placidly looking out. He holds a book roll in his left hand, and the right, drawn back to the body, could have held the edge of his garment. Once again we encounter here the old polis ideal at a time when the polis was long gone. What is particularly significant, however, is that this ideal is now evoked by people whose fulfillment in life can be conceived only in the private sphere. One of Metrodorus' writings bore this revealing title: On the Circumstance That Private Life Leads to Happiness Sooner Than Public (Clem. Al. Strom. 2.21 = II.185 Stahlin).

Just as in Epicurus' own teachings, the statues of his friends and disciples focus on the central goal, the condition of spiritual peace and inner joy. Only the master himself is presented as the pioneering spirit, in fact more as a kind of prophet than as one who teaches his students how to think. In the Kepos, great importance was attached to internalizing the teachings of the master. Epicurus had his pupils learn certain key sayings by heart and memorize them so that they would have them ready to hand at any moment. These sayings of the master, the kyriai doxai, functioned as a kind of catechism (D. L. 10.35,85). Perhaps there is an allusion to this constant memorization in the book rolls in the hands of all three statues, or to pastoral letters of Epicurus, which served the same purpose. Epicurus and Hermarchus pause in their reading, the book roll open, while Metrodorus holds his untied in the right hand, as if he were about to start reading.[34] It is rather striking that it should be the statues of Epicureans that hold the book roll. It cannot be meant simply as a symbol of education, as it will be in later Hellenistic portraiture, since Epicurus explicitly rejected the notion of education for its own sake.

In retrospect, a comparison of the portraits of Epicurus and his two kathegemones with those of Chrysippus and the other mighty thinkers reveals that the former must have had a different purpose. The great teachers are presented as exemplars who have already attained the goal. They are both a reminder and an admonition to succeeding generations. This portrayal is in accord with what we may conjecture about the statues' function in the Kepos, where friends and pupils regularly gathered for ceremonies in memory of Epicurus, Metrodorus, and

members of Epicurus' family perhaps in front of the mnema mentioned earlier. The whole calendar of the Epicurean year was organized around these memorial services, at which they would read from the works of the great teachers. In later times, we have evidence for an actual cult of the Epicureans, complete with icons:[35] "They carry around [painted] portraits [vultus ] of Epicurus and even take them into their bedrooms. On his birthday they make sacrifices and always celebrate on the twentieth of the month, which they call eikas —those same people who, so long as they are alive, insist that they do not want to be noticed" (Pliny HN 35.5). In the context of such rituals, the portraits served as a memorial and an honor, as well as an inspiration to follow in their path.

A statuette of the first century B.C. confronts us with a very different image of an Epicurean (fig. 70). If only the head were preserved, with its carefully tended hair and beard, and the contented expression similar to that of Metrodorus, we might well be tempted to identify him as one of the third-century Epicureans. But the proudly displayed fat belly and the uninhibited self-satisfied demeanor, recalling the statue of the Cynic in the Capitoline (cf. fig. 72), suggest that this is not a portrait statue at all, but rather a genre figure, a typical Epicurean. We may be reminded of the type that Horace had in mind, in his ironic characterization of himself:

As for me, when you want a laugh, you will find me in

fine fettle, fat and sleek, a hog from Epicurus' herd.

(Epist. I.4.15f)

This is evidently the image that many people outside the Kepos had of the typical Epicurean: a prosperous bon vivant, always carrying with him the sayings of the master. At least this was the case by the time of Horace, after the popular stereotype had established itself, thanks mainly to New Comedy, that the Epicurean principle of pleasure applied mostly to eating and drinking (fig. 70).[36] The statuette's portrayal of the old hedonist is not marked by genuine mockery, only gentle bemusement, He is indeed a sympathetic figure. This interpre-

Fig. 70

Furniture attachment with statuette of a

"typical" Epicurean. First century B.C. H: 25.5 cm.

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

tation is also implied in the statuette's original function, for it was the crowning element of a candelabrum that took the form of a column, like those used as table supports. The Ionic capital has two hooks from which lamps could be hung. Thus the jolly old man was visible mainly at symposia. This is a work of exceptional charm, in both style and

iconography, that succeeds in an eclectic combination of contradictory elements in the imagery of the philosopher.[37]

This statuette is a reminder that almost all preserved portraits of the Classical and Hellenistic periods are witnesses to the manner in which the subject understood and wished to present himself. We learn from them a great deal about the image that these intellectuals wanted to project, but as a rule little about how their contemporaries outside their own circle saw them, or to what extent the popular image matched the self-conscious one expressed in the official portraits. One would like to suppose that there had been earlier images that made fun of the all-too-serious thinkers. The statue types that happen to be preserved in Roman copies most likely represent only a small sampling of the variety of images of intellectuals of the Early Hellenistic age. We have, for example, no certainly identified portrait of a third-century Academic or Peripatetic. Surely there continued to be philosophers who clung to the traditional citizen style, such as the long-bearded philosopher on the familiar frescoes from Boscoreale, leaning on a knotty staff in the Classical manner.[38] Furthermore, not all the famous teachers and thinkers were depicted seated, as one might think. For example, the well-known bronze head of an intense philosopher from the Antikythera shipwreck, whose expression and manner recall the portrait of Chrysippus, belonged to a standing statue with the right hand raised in a rhetorical gesture.[39] Stance and pose were presumably no less varied than facial expression.

Another type that seems to have been particularly important was that of the reader, which we have already met in the statue of Metrodorus (fig. 63). Even outside the Kepos, this was already a standard part of the repertoire for representing the intellectual in Early Hellenistic art. Schefold has called attention to two statuettes and suggested identifications for these two as the Academic philosophers Krantor of Soloi and Arkesilaos, probably because the Academics early on turned to the interpretation of Plato's works, and because they were generally reputed to be great readers (D. L. 4.26, 5.31f.).[40] (The story is told of Arkesilaos that he could not go to bed at night without having first read a few pages of Homer, "and in the early morning, when he

Fig. 71

Portrait of a man reading. Bronze statuette after

an original of the third century B.C. H: 27.5 cm.

Paris, Cabinet des Médailles.

wanted to read Homer, he used to say that he was going to see his lover" [D. L. 4.31]. Unfortunately, this is not sufficient grounds for an identification!)

The intellectual depicted in the statuette from Montorio (fig. 71) gestures with his left hand toward the book roll that he holds in his right, like one who is about to begin reading. The left arm is enveloped in the cloak, like that of other seated statues, yet it is captured in

a momentary movement. This is probably meant to suggest the start of a session of reading, "reaching for a book." The head, turned to the side in a contemplative gesture and looking up, would also suit this context. He could scarcely be a philosopher giving instruction, for that entails a gesture of the right hand. Perhaps he is meant to represent a philologist. An interesting life-size seated statue in the Louvre, also derived from an original of the third century, must also have depicted a reader, to judge from the bent-forward position of the upper body and the arms.[41] Particularly noticeable is the casual pose, recalling that of Poseidippus (cf. fig. 75): yet another way of expressing concentration. In the well-known philosopher statue from the Ludovisi Collection, now in Copenhagen,[42] at one time associated with a portrait of Socrates, the figure of the reader acquires an almost exemplary quality through its very high placement and deliberate frontality. The original from which this statue derives probably belongs to the mid-second century, a period in which the motif of reading was of interest not as a process to be physically rendered, but rather as a paradigm for the educated man.

Who Would Honor a Cynic?

The statue of a Cynic of the mid-third century B.C. , preserved in a superb copy of the Early Antonine period, seems to satirize the new breed of pioneering thinkers (fig. 72). That this old man is indeed a Cynic has long been supposed, on the basis of his appearance, which is the antithesis of the good citizen's: he is slovenly, wears a short mantle made of coarse, dense material, and is barefoot. These are all characteristics of the Cynics, originally inspired by Socrates (Xen. Mem. 1.6.2; D. L. 2.28, 41).[43] The only element inappropriate for the Cynics, who were "practical philosophers" opposed in principle to any kind of formal education, is the book roll in the right hand. This is, however, an addition of the eighteenth-century restorer, who apparently could not imagine a philosopher without such an attribute of the intellectual.

The whole figure is practically an assault on the viewer. An ugly,

Fig. 72 a–b

Statue of an unidentified Cynic philosopher. Rome, Capitoline Museum.

belligerent old man and social outcast, he looks us straight in the face. In his right hand was originally a staff, which perhaps was even pointed at the viewer. Everything about his appearance expresses contempt for bourgeois manners and values: the clumsy, flat-footed stance, drooping shoulders and belly sticking out, the garment sloppily wound around the body and awkwardly held together in the fist, the uncombed, matted hair falling in his face, the untended clump of beard, and, finally, the wrinkled face with its vacuous, squinting look.

Here we have the complete antithesis not only of the ideal of the

proper citizen, but of the new image of the serious philosopher as well. Instead of presenting an expression of concentrated thought, he squints like someone who is either nearsighted or blinded by the sun. We need only compare the stylistically closely related countenance of Chrysippus (fig. 56) to see that the Cynic is not meant to express the concentration of serious thought or, for that matter, the ravages of old age or man's mortality but rather the self-satisfaction of a social dissident.

The public display of such a statue was itself a celebration of the provocative and antisocial behavior of the Cynics, calling into question every traditional value, a kind of fire-and-brimstone sermon decrying the pretensions and hypocrisy of bourgeois society. The simple, self-sufficient life has evidently not done this old man any harm. He seems well fed, and despite his lifelong avoidance of the gymnasium, he is shown as still tough and strong. His appearance has been likened to the iconography of poor people such as fishermen and peasants. But unlike these, he shows none of the physiognomic characterization that in this period would carry connotations of inferiority.

Who could have commissioned such a statue? It is hard to believe that a polis would have chosen to honor such a subversive provocateur with a public monument. It is equally unlikely that a man like this had a wealthy following of students and friends. But it is entirely possible that one individual, even a Hellenistic king, could have dedicated such a statue in a sanctuary or gymnasium, as a way of asserting that this was the only kind of "practical philosophy" that he truly found credible as a way of life. Though it is true that the Cynics believed in going "back to nature," to a simple life free of the "unnatural" constraints of social convention, this does not mean that they rejected the social order in principle. They too believed that virtue can be taught and saw themselves in the role of educators (D. L. 6.105). Krates of Thebes, for example, Diogenes' eldest pupil and the first teacher of Zeno, was very popular with his fellow citizens, because he actually discussed their problems with them. People opened their doors to him, enjoyed his visits, and revered him as a kind of lar familiaris .[44]

The face of the old man in the Capitoline Museum is unique in the corpus of preserved Hellenistic portraiture. Undoubtedly there were

Fig. 73

Head of a Cynic (?). Roman copy of a statue

ca. 200 B.C. Paris, Louvre.

other "character studies" of this kind, in which sculptors commemorated the behavior and appearance of those who practiced a kind of antiphilosophy and a defiant alternative life-style. This is, at least, the impression we get from several copies of anonymous philosopher portraits of the late third or early second century, whose hostile expression and slovenly appearance evoke thoughts of the Cynics and related groups. A particularly impressive example is a head in the Louvre with disgruntled countenance, wild beard, and matted hair over the brow (fig. 73). The original was probably an important work of the High Hellenistic period.[45]

The Philosopher and the King

The philosopher statues of the third century are thus the first true portraits of the intellectual in Greek art, for they are the first that attempt to render the thinking process itself, its goals and achievements. Whereas the portraits of thinkers and philosophers in the fifth and fourth centuries had depicted contemplation—when at all—as merely one element of the ideal citizen, within a rigidly structured art form, the purpose now is to convey exclusively and as concretely as possible, different conceptions of intellectual activity. The sharp differences in appearance between the representatives of the different philosophical schools show that the primary concern was still not with the individual thinker, but rather with depicting the intellectual process—however defined by the various schools—as a special achievement. The philosopher represented a challenge to pupil and fellow citizen alike, whether by the force of argumentation or through his ethical stance. The portraiture makes a specific claim, as does the philosophy itself. The fact that each of the different messages reached only a portion of the population is a concomitant of the changed social constraints.

For the Stoics, thinking means above all mental struggle, the triumph of the active mind over the frailty of the body. Ever since the Archaic kouroi, Greek artists had celebrated the male body as the outward manifestation of the subject's physical and spiritual perfection, his kalokagathia . In statues like that of Chrysippus, the body loses its preeminence and now functions only as a foil for expressing the triumph of mind over matter. But thinking and intellectual activity are not simply praised as an end in themselves. Rather, they stand in the service of a moral and rational way of life. As had always been the case, the body expresses one's ethical stance: in a negative sense for the Stoics and Cynics, in a positive sense for the Epicureans, whose "classical" bearing and regular physical features convey an inner calm and self-assurance based on a sense of intellectual superiority.

In the urge to instruct, these philosopher statues accord perfectly with the old traditions of the polis. But the way in which they heroize

their subjects is new: Chrysippus with his irresistible argumentation, the intellectual superiority of Epicurus and Zeno. They belong to an entirely different category from the monuments in honor of leading citizens of the past or present age. Rather, they demand a special position, just as their subjects, while alive, occupied a special position within the city. These statues set alongside the civilian magistrates, benefactors, and leading citizens a new, self-designated authority comparable only to the images of kings.

The painfully distorted posture of the Stoics should not obscure the fact that these portraits intended, in their own way, to stand alongside those of kings, in spite of (or perhaps because of) the apparently ludicrous nature of this claim. For example, the statue of Chrysippus stood near an equestrian monument, probably for one of the kings, behind which he must have seemed to be hiding. The peculiar conjunction of these two statues inspired Karneades to an ironic parody of Chrysippus' name: "He [Chrysippus] had an inconspicuous little body [somation euteles ], as one can see from his statue in the Kerameikos, which hides behind the nearby equestrian monument, which is why Karneades named him 'Kryphippos,' on account of his horse-hiding" (D. L. 7.182). Karneades is here making fun of his chief philosophical opponent, the man whose dialectics kept him occupied his entire life. But beyond that, the anecdote contains for us an important hint as to what effect such a statue had in the context of neighboring monuments. It shows how a philosopher statue was perceived alongside an equestrian statue of a king, probably over-life-size and certainly in a dramatic pose. The frailty of the bent-over old man achieved its full effect only when placed beside the monuments of the mighty. As Ernst Buschor put it, the "pathos of tranquility" was consciously set beside the "pathos of power." The intention was to cast a shadow on the brilliance of the royal epiphany, to expose it as transient and hence superficial. The philosopher's thoughts will in the end outlive kingdoms and imperial powers.

The Early Hellenistic age was evidently well aware of this special relationship between intellectuals and the men in power. It is reflected in a whole series of stories and anecdotes of the third century, starting

with the famous visit of Alexander the Great to Diogenes in his barrel.[46] Karneades' joke does, admittedly, suggest that, after two or three generations, the proud claim of the philosopher with the feeble body was no longer fully understood. And the statue that was put up for Karneades himself is a different matter altogether (see p. 181).

Poseidippus: The Hard Work of Writing Poetry

An age that was able to express such subtle distinctions among the various schools of philosophical thought must also have sought ways to express visually the very different activity of the poet. But in fact, in comparison with the rich repertoire of philosophers, the few securely identified portraits of contemporary Early Hellenistic poets seem at first rather a disappointment—at least for the student expecting to find images of poetic inspiration and art.

Menander, as we have seen, was portrayed as a man of fashionable appearance who loved the life of luxury, one considered soft and ostentatious compared to the old polis ideal, but in this way became the model for a new generation in Athens at the beginning of the third century. Yet nothing about his statue refers to his being a poet. The same is true of another seated statue of a poet of similar date, the so-called pseudo-Menander in the Vatican. In its relaxed pose, this statue too expresses the private values of tryphe .[47] It is only on Late Hellenistic copies of the Menander portrait that we may perhaps see an attempt to adjust the facial expression to make it more dramatic.[48] The actual sense of poetic inspiration, however, is first achieved on a group of reliefs that portray a heroized Menander, nude to the waist, in the act of writing, accompanied by his two sources of inspiration, the Muse and the mask (fig. 74).[49] But the original that lay behind these reliefs is a creation of the Late Hellenistic age, probably intended for display in Roman villas. Evidently by this time the stylish Menander of the Early Hellenistic statue was perceived as too bourgeois; what was wanted instead was a more imposing image. This is accomplished above all in the bare chest and the elevated poise of the head.

Fig. 74

Menander with his Muse. First-century B.C. relief. Rome, Vatican Museums.

It would be most interesting to know whether this kind of image of the inspired poet ever carried over into honorific statuary of the Early and High Hellenistic periods, or if it occurs only in the retrospective portraits with which we shall deal in a later chapter. The only work that might be relevant here is the statue of the Attic comic poet Poseidippus (316–ca. 250 B.C. ), of the mid-third century (fig. 75).[50] At first glance, he may be even more disappointing than the Menander, if it is inspiration and spirituality we are after. The head of the inscribed copy in the Vatican, however, with its gloomy countenance, is not that of the Greek poet, but of a Roman of the late first century B.C. who has usurped the statue of a poet to try to pass himself off as a cultivated gentleman. But thanks to a remarkable discovery by Fittschen, we now know the authentic portrait type of Poseidippus in a fine copy of the head. The careless sculptor who reworked the poet's head into that of

Fig. 75

Statue of the comic poet Poseidippus (316–ca. 250). Reconstruction

by K. Fittschen. Göttingen University, Abgußsammlung.

the Roman left a few locks of Poseidippus' hair on the nape of the neck, and these locks enabled Fittschen to recognize the true Poseidippus in a previously anonymous portrait type (fig. 76). It is a massive head, with broad, full face, and had previously been taken to be the portrait of a Late Republican politician, although the existence of a

Fig. 76

Portrait of Poseidippus. Geneva, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire. (Cast.)

herm in the Uffizi with the same portrait type should have suggested otherwise. In short, it is a triumph for good old-fashioned detective work, based on counting locks of hair and a thorough documentation, and, at the same time, a warning not to put too much confidence in a stylistic chronology, especially in Hellenistic art!

Quite unlike Menander, Poseidippus sits with his feet far apart, in a rather inelegant pose, on a chair with an extremely heavy, curved backrest. His legs are awkwardly positioned, the body slightly bent over as if about to cave in. We need only compare the roughly contemporary statues of Epicurus and his circle to realize the full effect of this heavy and pedestrian pose. He is a ponderous, well-nourished gentleman with noticeable paunch. We have already observed in many phi-

losopher portraits how realistically both the physiognomy of the face and the anatomy of the body could be rendered. Realism in the depiction of old age was in those instances not simply a matter of observation or of sculptural style, but the medium of philosophical instruction. Thus we should not assume that the sculptor wanted merely to convey the idea that Poseidippus was a man of ample proportions. Rather, it is more likely that the emphasis on the plump body and massive head carries a more general message. Probably it alludes to the ideal of Dionysiac extravagance and tryphe that was especially favored at the court of the Ptolemies. Certainly the cooks play important roles in the plays of Poseidippus, and in New Comedy in general, and this too is not unrelated to the notion of tryphe as a way of life.[51] It seems that in the third century, the well-fed body and full face were considered attractive, especially once the Ptolemies, as the protagonists in this new Dionysiac ethos, had themselves so depicted.[52] Indeed, the changing preference for thinner or heavier bodies in different time periods is, in the end, also a symbolic expression of particular social values.

This is not the only respect in which the portrait of Poseidippus seems to conform to the fashion of his age. Like Menander, he is also clean-shaven, and the same is true of the relatively few portraits of other Hellenistic poets that can be recognized as such among preserved Roman copies. In the light of our earlier discussion of beards and their connotations, this could hardly be an insignificant detail. Evidently, poets tended to follow contemporary fashion, unlike the philosophers, and did not perceive themselves in the same way as distanced from society at large or as the guardians of traditional values.

Poseidippus' fleshy face has, in addition, a peculiar expression (fig. 76). Although the brows are again drawn together, the nervous and agitated play of the features does not convey a sense of strain and intellectual effort, as in the Stoic philosophers. Instead, the mouth is relaxed and slightly open, while the eyes do not look straight at us but are directed somewhat downward. It seems that the artist was indeed trying to convey something of the laborious process of composing verse. The unusual pose of the raised arm with relaxed, open hand could suggest that he is keeping time, unconsciously rehearsing the

meter as he searches for just the right word. The closest parallel for the raised arm is on a copy of the Menander relief that Margarete Bieber recognized as the original, Late Hellenistic version. One may also be reminded of the depiction of a young poet on a Roman funerary altar of Trajanic date.[53] If this is indeed the key to the correct interpretation, then we might go further and see the loose and gawky seated posture as an expression of "abstractedness," a consequence of his concentration on the poetic process. A comment of Pliny the Elder (HN 35.106) suggests that in other media of Early Hellenistic art as well there were indeed images of poets with their own particular expression. In describing a work by the painter Protogenes, he mentions the Alexandrian tragic poet Philiskos, a contemporary of Ptolemy II, represented "in a meditative pose" (meditans ). This description recalls a fine caricature in terra-cotta of the late third century B.C. that was found in Olympia but was made in Alexandria (fig. 77).[54] It represents a poet deep in meditation, his massive head weighed down by heavy thoughts. The pose of the body could well be inspired by an honorific statue, as a comparison with the thinker in the Palazzo Spada suggests (fig. 57). Footstool and pillow once again allude to the private sphere, while the contrast between the simple chair and the elevation of the figure, as if on a throne, is evidently an element of caricature. It comes as no surprise that this testimonium to the mockery of intellectuals should have originated in Alexandria.

Poetry, then, is characterized in the statue of Poseidippus not as a stroke of ecstatic inspiration, but as a long and strenuous and not especially enjoyable process. One would be tempted to speak of the "forging of verses" if this did not conjure up an unfortunate association with Wagner's Meistersinger . The parallel with the statues of Stoic philosophers is obvious, though the difference is also clear. The poet's work is not strictly a matter of a powerful act of will, but more of searching, of listening to his inner voice, of feeling his way. The public aspect is here fully suppressed. Though the form of the statue is a conventional one, the poet behaves quite differently from Menander. Like the statues of the reading philosopher, this one also gives the viewer the impression of peering unobserved into a private and intimate world, almost of being a voyeur.

Fig. 77

Caricature of a tragic poet (?). Alexandrian

terra-cotta statuette, late third century B.C.

Olympia, Museum.

The movement of the right arm, as well as the introverted facial expression, is strikingly reminiscent of Joshua Reynolds's portrait of 1769 of the writer Dr. Samuel Johnson.[55] One wonders whether Reynolds might have drawn inspiration from the statue in the Vatican, already well known then, or if the ancient and modern artists arrived independently at the same psychological insights.

Soft Pillows and Softer Poets

Just as Menander (fig. 45) had done, Poseidippus also sits on a noticeably plush cushion. It is possible that this is a specific visual symbol in

the iconography of the poet, based on the idea of a comfortable domestic ambience as the prerequisite to poetic inspiration.

This interpretation suggests itself in spite of the meagre state of our evidence. The statue of the so-called pseudo-Menander, which was found together with that of Poseidippus, likewise shows the poet in a relaxed pose on a backed chair with thick cushion.[56] The same motif is also found in the reliefs depicting Menander mentioned earlier, as well as the famous wall painting in the Casa di Menandro in Pompeii. That the cushion is not restricted to comic poets can be inferred from the statue of the tragic poet Moschion (fourth–third century), though in this case, unlike Menander, Poseidippus, and the pseudo-Menander, he wears a simple mantle without the undergarment, and his chair does not have the backrest.[57] The most impressive example, however, is on the Late Antique diptych in Monza with a poet and Muse. The poet with shaven head (perhaps of the Late Republic) is seated with legs crossed upon a throne with a particularly luxurious cushion. The book rolls and diptychs strewn on the floor, together with the poet's expression, looking out dreamily into the void, can be taken to express poetic activity.[58] The notion that being a poet is well suited to a comfortable, "private" life-style could well have been widespread even before the Early Hellenistic statues. On a painted grave stele of the mid-fourth century, a certain Hermon sits casually leaning back on a splendid chair with a high back and thick cushion.[59] His literary association is made clear by the large cabinet of book rolls beside him, a rather rare motif at this period.[60] If this observation is correct, then the pillow in the statue of Menander may already be understood as a specific "poet's cushion."