The Fragile Structure of Newark's Success

"In the world of urban renewal," Harold Kaplan commented when the Newark Housing Authority was riding high in the early 1960s, "project building seems to yield more project building. . . . After a certain point successful agencies can do nothing wrong. They are rarely involved in political skirmishes because they are rarely challenged."[23] In a few short years, however, the world of urban renewal in Newark collapsed. Constituencies that had been quiescent became active and influential. Ghetto blacks, whose previous role in renewal had been only an occasional irritant, became a major force. This challenge to NHA's policies—sparked by an ill-conceived proposal to use a huge tract of land in the ghetto for a state medical college, and dramatized by a devastating riot in 1967—fundamentally altered the politics of redevelopment in Newark. Faced with new and intense pressures, the alliance that had shaped urban renewal shivered and fell apart. Federal and state roles altered sharply; private developers faded in importance; Danzig, the skillful public entrepreneur who had molded and maintained the renewal alliance in Newark, departed. And the most "successful" urban renewal program in the New York region lost much of its capacity to make a significant impact on the pattern of development in Newark.[24]

Underlying these changes was increased dissatisfaction and political activism on the part of Newark's black residents. Rapid escalation of ghetto demands for more relevant programs and a meaningful role in the development process occurred in cities across the nation in the early 1960s. In Newark as elsewhere, blacks began to question programs that provided neither benefits nor a meaningful role for community and minority interests. By the mid-1960s, Newark's urban renewal had cleared nearly 6,000 dwelling units in neighborhoods selected by NHA for redevelopment. Yet 40,000 of the city's 136,000 housing units remained below national standards, giving Newark the highest proportion of substandard housing of any major city in the United States. From the perspective of NHA, "housing conditions in Newark [were] better than they have been in our time."[25] But for ghetto dwellers, housing conditions were "indescribably bad."[26] Moreover, urban renewal reduced the amount of housing available to poor families. A tight housing market, poverty, and racial discrimination compromised the ability of NHA to relocate the uprooted in the "decent, safe, and sanitary" dwellings called for in the Housing Act of 1949. As a result, large numbers of those displaced by redevelopment were resettled in slum housing, where they often paid higher rents and soon were uprooted again by the public bulldozer. To a state investigating

[23] Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics, p. 35.

[24] The discussion below is based mainly on the following sources: M. Duncan Grant, "Housing Authority Politics in Trenton and Newark"; Robert Curvin, "Black Power and Bureaucratic Change," Graduate Seminar Paper, Princeton University, December 1971; David Marshall, "Urban Renewal in Newark"; New Jersey, Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action (Trenton: 1968); and Harris David and J. Michael Callan, "Newark's Public Housing Rent Strike," Clearinghouse Review, 7 (1974), p. 581.

[25] Louis H. Danzig, executive director, Newark Housing Authority, quoted in New Jersey, Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action (Trenton: 1968), p. 55.

[26] Committee of Concern, a black civic group, quoted in "Asks Study of Violence," Newark News, July 18, 1967.

commission reporting in 1968, it seemed "paradoxical that so many housing successes could be tallied on paper and on bank ledgers, with so little impact on those the programs were meant to serve."[27]

Significant black opposition to NHA first emerged about 1960, in connection with the authority's effort to renew the Clinton Hill area of the black Central Ward. The Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council fought to protect the interests of the area's black residents. Also during the early 1960s, the Congress of Racial Equality and the Students for a Democratic Society generated protests on housing and other problems, such as job discrimination and police brutality. But these early efforts were sporadic, and made little impact on NHA and its allies. Newark's urban renewal alliance continued its normal pattern of decisionmaking well into the decade, with no significant involvement by the city's growing and increasingly alienated black community.

The Medical College

Business as usual for NHA and its allies led to a spirited effort to persuade the trustees of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry to locate the state medical school in Newark. From NHA's perspective, the prospect of attracting the $60 million educational facility was another potential milestone in the process of converting "badly used land to higher and better uses," another step in making Newark a "city alive."[28] Danzig, Mayor Hugh Addonizio, and other city officials met privately with the medical school's trustees, while the city's newspapers and downtown business leadership waged an intensive public campaign during 1966 to convince the college that central Newark was a better site than suburban Madison in Morris County, the location preferred by most of the school's officials.

Initially, NHA and the city government offered the medical school a 20-acre site in the Fairmount Urban Renewal Project. The trustees responded by praising Newark as a potential home for the medical school, but insisted that the college needed 150 acres, presumably much more land than could be made available in crowded central Newark. NHA and City Hall were dismayed, but not ready to quit despite the college officials' obvious desire for a suburban location. If the medical school had to have 150 acres, Newark would provide 185 acres in the black Central Ward. A city official later explained the strategy developed by Newark in the fall of 1966:

We thought we would surprise them . . . and we drew a 185-acre area which we considered to be the worst slum area. It included Fairmount and surrounding areas, which was clearly in need of renewal, and we were going to proceed with the renewal in any case in that area. . . . We felt in the end they would come down to 20 or 30 acres in Fairmount, or in a battle we might have to give up some more acreage. We never felt they would ask for 185. We felt it was a ploy on their part.[29]

[27] Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, p. 55.

[28] Newark Housing Authority, City Alive! p. 8.

[29] M. Donald Malafronte, assistant to Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, quoted in Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, pp. 12–13.

Responding to Newark's bold offer, the medical school continued to demand 150 acres. The trustees then upped the ante by specifying that the college would come to Newark only if NHA and the city government were able within 10 weeks to "complete legal and financial assurances that will provide the college with a site of some 50 acres upon which it would begin initial construction by March 1, 1968 . . . [and] irrevocably commit approximately 100 additional acres for future college use to be promptly cleared and deeded to the college as the need for the land is determined . . . solely by the trustees."[30] To make things even more difficult for the city, the initial fifty acres was not to come from cleared land in the Fairmount urban renewal site. For city officials, the trustees' demand for uncleared land "was a slap in the face. . . . It was our opinion that they were attempting to get out of the situation. . . . What they wanted was across the street from cleared land. This to us was insanity and enraging because they knew this was not an urban renewal area. They knew that the urban renewal process is three years and perhaps five."[31]

Despite the dismay over the trustees' intransigent position, Newark's leaders were determined to secure the prize of the medical college. The medical school's offer was accepted in December, with the mayor expressing confidence that "we can meet all the provisions set by the trustees."[32] To ensure quick assembly of the initial 50-acre parcel, the city was prepared to use its power of condemnation, and NHA was ready to cut back other urban renewal projects to make funds available to underwrite land acquisition for the medical school. Trenton offered a helping hand, as the state legislature with the blessing of Governor Hughes authorized Newark to condemn land for the college, and to extend its debt limit by $15 million to provide the funds for the initial land acquisition. Support also came from NHA's allies in Washington. Officials at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)agreed to the methods employed by Newark in shortcutting the normal urban renewal procedures for the medical college. They also, in Mayor Addonizio's words, assured "us it will qualify as an urban renewal project."[33]

During the complicated bargaining that brought the medical college to Newark, none of the principals paid much attention to the views of the several thousand black families living in the 150-acre target area. For proponents of the project, replacement of a ramshackle black neighborhood by the medical school meant new vitality for Newark, $15 million in new jobs, and the elimination of a slum that was estimated to cost the city $380,000 more annually in public services than it generated in taxes. But from the perspective of the Central Ward's black dwellers, a medical school "in the heart of the ghetto," like Newark's "vast programs for urban renewal, highways, [and]

[30] Statement of the Board of Trustees of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry, quoted in Malcolm M. Mamber, "Newark Is Given March I Deadline to Provide Medical Center Land," Newark Sunday News, December 11, 1966.

[31] Malafronte, quoted in Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, pp. 13–14.

[32] Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, quoted in Bob Shabazian, "City Pledges Land Med School Asked," Newark News, December 23, 1966.

[33] Quoted in "Council Pledges Med School Funds," Newark News, December 27, 1966.

downtown development . . . seemed almost deliberately designed to squeeze out [the] rapidly growing Negro community that represents a majority of the population."[34]

In NHA's vast renewal projects of previous years, grass-roots protest had been haphazard and ineffective. But by 1967, the black population in Newark had grown to a majority, and the increasing political sophistication of black citizens and their organizations made it possible to develop sustained opposition to this latest renewal scheme. Resistance to the medical school plan mounted rapidly in the Central Ward during the spring of 1967. Residents of the target area enlisted the support of many black leaders in organizing the Committee Against Negro Removal, which argued that the medical college's benefits to the city "would be less than the misery it would cost."[35] Newark's antipoverty agency, the United Community Corporation, publicly opposed the project. Underlying black opposition to the medical college was a lack of communication between official Newark and the ghetto, development priorities that largely ignored the poor, and the pervasive fear of relocation. Commenting on the third factor, a state commission later emphasized:

Many residents did not believe official reassurances on this subject. People hear that in the past families have been displaced by urban renewal and forced to live wherever they could, and they see few vacant apartments of decent quality in which they know they can afford to live. The statistics on the quality of vacancies support the view of the people in the area. . . . The Medical College case simply brought these fears to a head.[36]

The rising chorus of black protest made little impression on NHA and City Hall, which focused their energies on the difficult task of meeting the medical college's stipulations. Negotiations between HUD representatives and city officials led to a federal agreement to rush $15 million to Newark to aid the project. Mayor Addonizio and NHA then pressed for City Planning Board approval of the large area as blighted, and the board held blight hearings in May and June. Despite vociferous opposition from blacks at the hearings, NHA was ready to move forward rapidly with clearance.

But NHA's opponents did not fade away as they had in the past. Discontent over the medical college combined with another racial controversy—in school politics, where the appointment of a white official to a top Board of Education post drew vigorous black protests—to make black Newark a tinderbox. The spark was provided by a confrontation between blacks and the police, and a devastating six-day riot erupted in July 1967. When the smoke cleared from the Central Ward, 26 were dead and over $10 million in property had been destroyed. Black dissatisfaction with the medical school project in particular, and the city's renewal process in general, had been tragically underscored.[37] Business as usual was over for the Newark Housing Authority.

[34] Tom Hayden, Rebellion in Newark (New York: Vintage, 1967), p. 6.

[35] See Douglas Eldridge, "Displacees Fight Med School Site," Newark News, January 11, 1967.

[36] Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorders, Report for Action, pp. 61–62.

[37] The riot and its causes are summarized in Report for Action, especially Chapter One. On the evaluation of protests against the medical school project, see Grant, pp. 126–131.

The Collapse of the Urban Renewal Alliance

Of the Newark riot's many lessons, one of the clearest was the hostility of the city's black population to urban renewal and the kind of "successes" produced by NHA and its allies. With their opposition to the medical school and NHA's approach traumatically dramatized, black interests were able to enlist new allies in their opposition to the renewal alliance, and to exercise increasing influence within the city. The state government abandoned its passive role, and became an active participant in the effort to redesign the medical school project. Federal policy also changed, placing more emphasis on relocation needs and on community involvement in the renewal process. Within three years of the riot, the growing numbers of blacks and increased political sophistication resulted in the election of a black mayor in Newark. These and related changes eroded the independent power of the Newark Housing Authority, and thus destroyed the basis for the alliance which NHA had so skillfully constructed in the 1950s.

Traditionally, state officials in Trenton had deferred to the federal/local alliance in determining the direction of renewal programs, becoming active only to facilitate agreements already made by the alliance when legislation or other state concurrence was required. As noted above, this approach had been followed on the medical school, as Governor Hughes signed legislation in March permitting Newark to condemn, buy, and sell the land needed for the 150 acres demanded by the trustees. Two weeks after the riot, however, the state administration began to reverse its course. Hughes and his aides pressed the medical school to reduce the campus to 50 acres. They sought to convince the city to use the remaining land for low-income housing, child care, health centers, and other community projects. State officials also urged the city to ensure that representatives of the renewal area take part in planning for the projects. Little support for the state's proposal came from NHA and City Hall, which were fearful of losing the medical school, and of sharing their power over redevelopment decisions with the rebellious ghetto. Equally unresponsire was the medical college, whose president continued to insist that "we have a contract for 150 acres," and whose trustees responded to pressure by threatening to seek a site outside Newark in the suburbs.[38]

The resistance of NHA and elected Newark officials to the state initiatives ensured that state officials would become central participants in working out a compromise between the city, the medical school, and the host of local interests now seeking a piece of the action. At this juncture the state's efforts received a powerful assist from Washington, for HUD would not approve the use of urban renewal funds to clear the site in the face of strong community protests, and in the absence of an acceptable relocation plan. Responding to these pressures, the city and the medical school reduced the campus to 98.2 acres, and shifted the site slightly to reduce the number of families to be relocated.

These proposals, however, did not satisfy black demands on relocation and participation. At this point, Washington sided with the neighborhood forces. Early in 1968, HUD and the Department of Health, Education and Wel-

[38] Dr. Robert A. Cadmus, quoted in Ladley K. Pierson, "Med School Debate Seen 'Historic,'" Newark News, March 3, 1968.

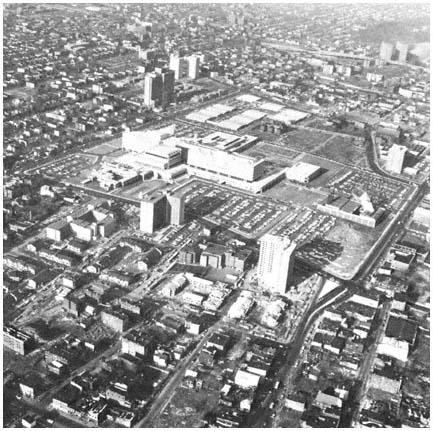

The completed campus of the New Jersey College

of Medicine and Dentistry. Even though the plans

for the campus were scaled down after

the Newark riot, a large amount of land still was cleared for

the project, displacing low-income blacks from housing

similar to that surrounding the campus.

Credit: New Jersey Housing Finance Agency

fare—which provided much of the funding for construction of the medical college—indicated that the $43-million in urban renewal and medical facility grants would be approved only if there were agreement with the community on seven issues: (1) the amount of land to be used by the college; (2) community health services to be provided by the medical school; (3) relocation of residents from the campus site; (4) employment practices during construction of the school; (5) employment and training policies of the college; (6) future housing programs in Newark; and (7) community participation in the federal Model Cities program, which was just getting underway in Newark.

In the face of these federal, state, and community pressures, Newark officials and the medical college had no alternative but to compromise. The college agreed to limit its campus to 57.9 acres, and to provide a wide range of community and medical training services. City Hall and NHA agreed that

neighborhood representatives would have a veto over development programs in the area surrounding the college, as well as a role in planning the construction of new housing in the city. In addition, the state promised to provide rent supplements where necessary for the 580 families on the site, each of whom was guaranteed relocation.[39]

NHA emerged from these negotiations a much weaker organization. In the future, it would have to share important powers with neighborhood interests, most of whom were hostile to the agency. Equally important, NHA could no longer count on the support of federal renewal officials. As we have seen, NHA's central role in urban renewal was closely linked to the financial support and program concurrence of the agency's federal allies. Before the riot, HUD had rushed to provide $15 million in support of the medical school project. Now, HUD was dealing directly with representatives of Newark's black and Puerto Rican communities, supporting their demands for improved relocation practices, and insisting that these groups be represented in NHA decision making. Moreover, as the complex negotiations over the medical college evolved after the riot, the role of state and community representatives became increasingly important, and NHA faded into a relatively minor role. The traditional pattern of NHA leadership was broken.

Not long after the medical school negotiations were completed, Louis Danzig resigned as NHA executive director. Danzig cited reasons of health, but he obviously was dissatisfied with the restricted role of his Authority in the medical college project and other programs in the post-riot era. In any event, the most important individual in making the renewal alliance work was gone. Moreover, his successor, promoted from within the agency, lacked the basic ability and political skills of a Louis Danzig.

At the same time that NHA was losing its control over the renewal process, the agency came under attack from the residents of its housing projects. NHA's tenants traditionally had been submissive, and had acquiesced in the authority's strategy of creating and controlling "tenant" groups. But the rising political consciousness of Newark's poor blacks and Hispanics, combined with their success in the medical school negotiations, led to increased militancy among residents of NHA's massive public housing projects. Independent tenants' associations were organized in 1968 and the following year a rent strike was initiated in protest against inadequate NHA facilities, repair programs, and safety measures. A second rent strike began in 1970 and continued for more than four years. The second strike had a particularly devastating effect on NHA's financial position, as several million dollars in rent payments were withheld from the agency during these years.

As the second rent strike began, NHA's ally in City Hall, Mayor Hugh Addonizio, was challenged at the polls by a black candidate, Kenneth A. Gibson, who was supported by a broad coalition of community and minority interests. One of Gibson's major campaign themes was to attack NHA's renewal policies and housing management programs. Gibson also endorsed the rent

[39] The state also pledged that at least one-third of the journeymen and one-half of the apprentices employed in the construction of the college would be black or Puerto Rican. For the details of the final agreement, see Paul N. Ylvisaker, "What Are the Problems of Health Care Delivery in Newark?," in John Norman, ed., Medicine in the Ghetto (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1972), pp. 108–116.

strike. His election in June 1970 as Newark's first black mayor severed another tie that had supported NHA policies and independence. City Hall now joined the federal government, state officials, and community groups in insisting that NHA pursue different objectives and be more responsive to lower-income needs.

Another blow fell on NHA from the agency's one-time allies in HUD. Increasing concern on the part of federal officials about the administrative and financial capacity of the authority led to an investigation of NHA by HUD in early 1971. The resulting report criticized management inefficiency in the authority and urged that NHA be split into two separate agencies, one for public housing management and the other for urban renewal programs. The authority resisted dismemberment, and HUD retaliated by threatening to cut off all federal funds unless NHA complied.[40] This impasse gave Mayor Gibson an opportunity to act as mediator. He persuaded HUD to provide emergency funds to meet utility bills and other immediate costs, and to drop its demand for complete separation of housing and renewal functions. In return, NHA consented to accept a "consultant" designated by Gibson, providing the mayor a means to exercise considerable influence over the authority's decision making. Thus, power over NHA actions shifted toward the mayor's of-rice, although conflict between Gibson and the city council prevented the mayor from exerting commanding influence over the authority.[41] Meanwhile, the rent strike continued until 1974, and NHA limped along, little more than a pale shadow of its former position as one of the nation's preeminent renewal authorities.

In the years since 1974, the mayor's office has used its appointing power, federal guidelines, and its negotiating skills to increase its control over NHA activities, turning the authority into an arm of City Hall's development efforts. Those efforts, which have included several housing, commercial and industrial projects, have had a modest impact on economic vitality and housing quality in Newark.[42] But the evidence bearing on the central theme of this discussion—the impact and strategies of a functionally autonomous development agency—ends with the NHA's collapse in the early 1970s.

The NHA's Urban Renewal Program in Retrospect

At each point in the series of events that reduced NHA's capacity to influence development, one might ask, would the urban renewal alliance have survived had this or that factor not been present? For example, would Newark's development still be shaped by a vigorous, relatively independent renewal alliance if there had been no medical school project? Or if there had been no major riot in 1967? Perhaps, but in view of the broader demographic and political changes in Newark during the 1960s, the nature of that alliance

[40] See U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, (Newark Area Office), "Comprehensive Consolidated Management Review Report of the Newark Housing Authority" (Newark: January 1971).

[41] During 1971–1973, the city council turned down three of Gibson's five nominees to the NHA, and as Gibson's first term drew to a close at the end of 1973, only three of the six NHA commissioners were Gibson appointees.

[42] See Newark Redevelopment and Housing Authority, 1977 Annual Report (Newark: 1978) and Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce, The Newark Experience, 1967–1977 (Newark: 1978).

probably would have been significantly changed, and the pace of renewal greatly slowed. Similar forces were at work elsewhere in the region's older cities, with similar overall impact on urban development, as illustrated in the discussion of New York City in the next section.

The rise and fall of the Newark Housing Authority underscores some general points that are important to an understanding of the variables that determine whether a governmental agency will be able to concentrate resources over time to influence urban development. NHA's experience emphasizes the crucial role an organization's leaders can play in determining the impact of constituency factors and the availability of funds. Robert Dahl's comments on urban renewal in New Haven apply to Newark as well. "Changes in the physical organization of the city," he notes, "entail changes in social, economic, and political organization." To develop a coalition that can continue to operate effectively amid such changes demands unusual leadership abilities. A strategic plan must be "discovered, formulated, presented, and constantly reinterpreted and reinforced." The skills required to identify the grounds on which coalitions can be formed, the "assiduous and unending dedication to the task of maintaining alliances over long periods, the unremitting search for measures that will unify rather than disrupt the alliance: these are the tasks and skills of politicians."[43] In Newark's successful urban renewal program, these political dimensions were located in the authority's headquarters rather than at City Hall. Because of these skills, the alliance grew and prospered, federal funds flowed in, and Newark like New Haven won a national reputation for urban renewal productivity.

As necessary as it is to construct a supporting coalition, the strategies used to neutralize potential opposition are equally crucial. The events recounted above illustrate the importance of these strategies. They also suggest the impact of constituency changes, which can generate serious resistance and undermine an apparently firm alliance. Opposition stemming from alterations in constituency factors may affect an agency or an alliance only in minor ways, or more centrally. An area of agency policy may be attacked, to be followed by remedial efforts that reaffirm or even strengthen the organization and its ability to achieve its goals. But other attacks from aroused constituencies can go to the "heartland" of an institution, fundamentally altering its direction and effectiveness, and perhaps impairing its ability to function at all. The Newark Housing Authority is a "heartland" case as far as its urban renewal program is concerned.

The NHA case in particular illustrates the potential importance of new constituencies that arise and become politically relevant to an agency. The ability of these groups to exert political influence may depend not only on increased numbers, wealth, and other "internal" resources, but also on dramatic incidents —or more precisely on a group's ability to link its concerns with such dramatic incidents which can generate support among other constituencies that are already influential in the policy arena. The leaders of successful functional agencies and alliances are often vulnerable to such strategies, being more likely than most political leaders to develop a "trained

[43] Robert A. Dahl, Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1961), pp. 201–202.

incapacity" to perceive and respond to these new constituencies. Compared with leaders of less "successful" agencies and with elected officials, their ability to scan the political horizon for new threats and challenges becomes attenuated. They come to believe, with Kaplan, that "after a certain point successful agencies can do nothing wrong." This was the fatal weakness of Danzig and his allies in the late 1960s, just as it was a limitation of Robert Moses in his slum clearance activities in New York City a decade earlier, and of the leaders of the Port Authority in the early 1970s. Thus, we see that "some princes flourish one day and come to grief the next"; for such a leader, "having always prospered by proceeding one way, . . . cannot persuade himself to change."[44]