Two—

Indecision and Change

Berlin, Winter 1887–88

In the spring of 1887 when Corinth left Paris, he had completed more than a decade of academic study. He might have looked back on this period with a greater sense of accomplishment had he been able to add to his bronze medal for The Conspiracy a similar token of recognition for his years at Julian's. As it was, he returned to East Prussia with little more to show than a few studies of the nude model. The knowledge that he was approaching his thirtieth birthday must have weighed heavily on him. Fortunately, he did not suspect that thirteen years of search and experimentation still lay ahead.

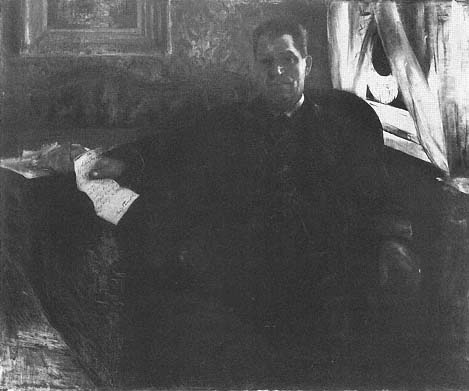

Except for a brief visit to the Baltic seacoast, Corinth spent the summer of 1887 in Königsberg. Of the five paintings he completed at this time the portrait of his father (Fig. 20) is the most important. In it once again he depicted a figure in a sunlit interior, except that, as in the portrait of 1883 (see Plate 1), Franz Heinrich does not really occupy that interior but sits in front of it. Daylight, entering through the window at the right, fills the room with a subtle glow, accentuates the structure of the sitter's face, and touches details with a sparkle of bright color. The pale blue of the letter Franz Heinrich holds in his right hand echoes the white and blue of the curtains and the windowpane. Patches of red and yellow enliven the dull green of the tablecloth. Although this portrait was painted only four years after the Munich portrait, Franz Heinrich looks not only markedly older but also much more frail. As in the earlier portrait, the posture is casual, but it fails to convey the same impression of comfort and ease. Instead, Corinth's father is seated rather stiffly in the armchair and seems unable to support his weight without effort. The face is taut, the expression of the eyes weary. Corinth must have begun the portrait shortly after his return from Paris, for at the end of July the painting was included in an exhibition organized by the Berlin Artists' Association at the Glass Palace in Berlin. It was moderately successful at best. According to Corinth, some of the critics "thoroughly flogged" him.[1]

Figure 20

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth with a Letter , 1887.

Oil on canvas, 87 × 105 cm, B.-C. 51. Museum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg.

Photo: WS-Meisterphoto Wolfram Schmidt.

Despite this inauspicious reception, in October Corinth went to Berlin to pursue opportunities that by his own account were luring artists to the city:

Berlin was thriving at the time. The population was expanding, and a strong interest in art was just beginning to develop. One could find plenty of newly rich bankers who were willing to support the arts, and it was easy for ambitious, capable, and truly talented painters to establish art schools of their own. This was the reason many young artists moved from Munich to Berlin, and if one was lucky enough to be a foreigner, one's fortune was already made.[2]

By the time Corinth arrived, Berlin had already experienced more than a decade of astonishing growth. After 1871 this old seat of the Hohenzollerns, suddenly the capital of a unified German Empire, was transformed into a major metropolis. With the city's intensified economic development, commerce and industry grew at a dizzying rate. As corporations and banks multiplied, immense private fortunes were created. Newcomers arrived by the thousands. In only nine years—from 1864 to 1875—the city's population almost doubled, passing the one-million mark. By 1885 it had increased to nearly a million and a half.[3] In 1872 alone no fewer than forty new construction firms began to operate,[4] gradually pushing the city's perimeter further west; mansions near the Tiergarten soon vied in opulence with the splendid apartment buildings along the Kurfürstendamm.

The visual arts in Berlin were dominated during these years by the Berlin Academy and its influential director Anton von Werner. Werner, still remembered for his photographically accurate depictions of scenes from the Franco-Prussian War, was only thirty-two when he became director of the academy in 1875. From 1887 to 1895 he also served as president of the Berlin Artists' Association, whose members controlled the annual academy-sponsored exhibitions. Until 1885 these exhibitions were predominantly local; not until the academy's centennial anniversary exhibition in 1886 were artists from other German cities and from abroad encouraged to participate in larger numbers. The 1886 exhibition, intended to propel Berlin into the intellectual and artistic community of older, more illustrious European capitals, turned out to be the nation's cultural event of the year and a matter of great national pride. Die Kunst für Alle , Germany's leading art journal at the time, devoted ten consecutive biweekly issues to the exhibition.[5] In addition to the German contingent, artists from nine foreign countries exhibited in the newly built Glass Palace—England, Belgium, Holland, the Scandinavian countries, Italy, Spain, and Russia. France—not unexpectedly—chose not to participate.

While the leading academicians reaped their customary accolades and medals from the exhibition, younger, innovative artists did not go unnoticed. Among the Germans was Max Liebermann, who exhibited three paintings: The Old Men's Home in Amsterdam (1880–1881; Collection Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt), Girls from the Amsterdam Orphanage in a Garden (1885; Kunsthalle, Hamburg), and Saying Grace (1886; private collection). The first two paintings were generally well received. The third elicited mixed reactions. Most critics applauded the sincerity of the religious sentiment portrayed but found Liebermann's unidealized models and their humble milieu offensive.

The same criticism was directed at two religious paintings submitted by Fritz von Uhde, Come, Lord Jesus, Be Our Guest (1885; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie), and The Last Supper (1886; present location unknown). But since these paintings made up in anecdotal interest whatever the figures lacked in conventional "beauty of form," Uhde received on the whole a more generous recognition than Liebermann.[6]

The academy exhibition of the following year, to which Corinth sent the recently completed portrait of his father, included few foreign artists. Moreover, most of the established German academicians, apparently not yet recovered from the previous year's exhibition, refrained from showing. A reviewer noted instead a marked increase in the number of younger German artists preoccupied with the same pictorial problem: plein air.[7] Liebermann was represented with his paintings Beer Garden in Munich (1884; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and Women Spinning (1880; painting lost) and Uhde with his first biblical scene in an outdoor setting, The Sermon on the Mount (1884; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest). The exhibition's succès de scandale belonged to Max Klinger, whose monumental painting The Judgment of Paris (1886–1887; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) elicited a wave of hostile criticism. Klinger's uncompromising naturalism in depicting the three nude goddesses led the Kreuzzeitung to publish a stern editorial on the decay of morals. Critics derided as the ultimate proof of his folly his efforts to fuse the picture and its immediate environment into a Gesamtkunstwerk by setting the huge canvas into an elaborate polychrome sculptured frame.[8]

The battle for modern art in Berlin was waged less vociferously in the galleries of two private dealers, Eduard Schulte and Fritz Gurlitt. Schulte, who in 1885 had taken over the former Salon Lepke on Unter den Linden, generally followed the accepted academic trend, though he did not exclude controversial artists altogether. In the winter of 1887–88, besides a number of portraits by Lenbach, he exhibited a group of paintings by Arnold Böcklin, an artist who had only begun to receive some recognition. Gurlitt was more enterprising. Since opening his gallery in 1880, he had displayed the work of painters from throughout Germany. He was among the first to exhibit works by Hans von Marées and Hans Thoma. His gallery was also the only place in Berlin where paintings by the French Impressionists could be seen. In October 1883 Gurlitt exhibited the small but exquisite collection assembled by Carl and Felicie Bernstein, consisting of works by Manet, Monet, Sisley, Pissarro, Gonzalez, and Morisot. Shortly thereafter he showed a selection of

works by Pissarro, Renoir, and Degas sponsored by the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Gurlitt's exhibitions inspired the young French Symbolist poet and critic Jules Laforgue, who from 1881 to 1886 lived primarily in Berlin, serving as a reader to the German empress Augusta, to write one of the earliest and most incisive analyses of Impressionism.[9]

The artistic milieu Corinth encountered when he arrived in Berlin in October 1887 thus offered the old and established as well as the new. It is not known whether he had visited the Berlin Academy exhibition at the Glass Palace during the summer, but because the portrait of his father was shown there, he was probably aware of the growing reputation of such artists as Liebermann, Uhde, and Klinger. Corinth himself, however, was not one to eagerly follow the avant-garde. His continuing image of himself as a student is suggested by his later confession that he felt "intimidated" on arriving in Berlin; aside from a "pent-up ambition to learn something," he had neither the "courage nor the determination to take any adventurous risks."[10]

Indeed, Corinth's Berlin output, dominated by drawings of male and female nudes, is little more than a continuation of his student work from Paris. Most of these drawings originated at Der Nasse Lappen (The Wet Rag), a private drawing club he joined soon after his arrival. Der Nasse Lappen was founded by Carl Steffeck, who had taught at the Berlin Academy from 1859 until his departure for the academy in Königsberg in 1880. Members of the club met in the evenings to draw after the live model. In the late 1880s the artists who took part in this Abendakt , in a studio on Potsdamer Strasse, included the painters Carl Friedrich Koch, Paul Souchay, and Adolf Schlabitz and the sculptor Max Klein. The art historian Heinrich Weizsäcker also occasionally joined the drawing sessions.[11] Corinth soon got to know the most prominent member of the group, Karl Stauffer-Bern, well enough to visit him in his studio on Klopstockstrasse, and the Swiss artist apparently introduced him at this time to Max Klinger and to the Berlin painter Walter Leistikow.

Although Karl Stauffer (1857–1891), a native of Bern, was only a year older than Corinth, he had already made a name for himself as a portraitist among the newly rich of Berlin. He also enjoyed the special favor and protection of Anton von Werner, who had helped him to secure his first important portrait commissions, which in due course included the portrait of the emperor's surgeon, Dr. von Lauer, and a portrait of the emperor himself. Adolph von Menzel, whose portrait Stauffer-Bern etched in 1885, was so impressed with the young man's talent that he frequently invited him to his home for dinner, an honor he bestowed on only a few. It was the "foreigner" Karl Stauffer-Bern

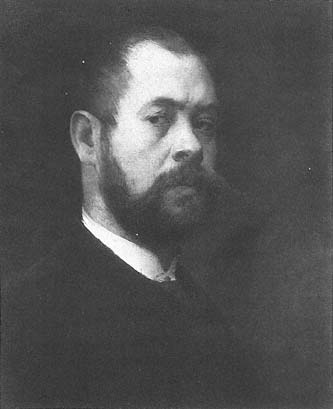

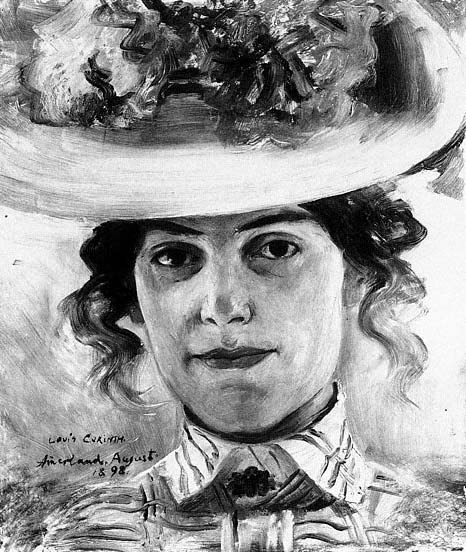

Figure 21

Karl Stauffer-Bern,

Self-Portrait , c. 1885.

Etching, 35 × 22 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern (S 10692).

whom Corinth clearly had in mind when he wrote of those "ambitious, capable, and truly talented painters" who had succeeded in launching profitable teaching careers in the nation's new capital. For in addition to pursuing his creative work, Stauffer-Bern both directed the portrait class of the Berlin Society of Women Artists and Friends of the Arts, whose students in 1885 included Käthe Kollwitz, then eighteen years old, and maintained a small ladies' academy of his own.[12]

Stauffer-Bern must have embodied for Corinth the success he himself was striving for. He had reason to believe the goal within his reach, moreover, for Stauffer-Bern's work was based on formal principles that Corinth was in the process of making his own. Both artists had been trained by Löfftz at the academy in Munich. Stauffer-Bern's reputation today rests primarily on his prints, although he made no more than thirty-seven.[13] His portrait etchings, such as the Self-Portrait (Fig. 21) of about 1885, convey the sitter's presence with striking immediacy, a quality he considered indispensable: "In my portraits I am not concerned with snappy execution or coloristic appeal but rather with the mathematically precise reproduction of form and the most delicate modeling, . . . because a portrait must be above all so lifelike that one is startled by it."[14]

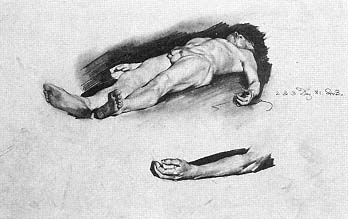

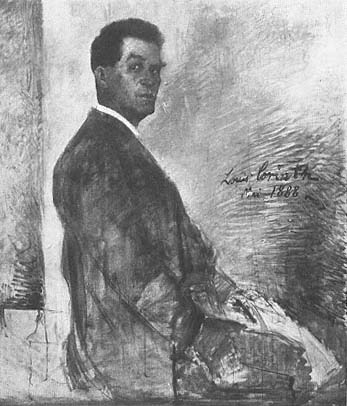

When drawing the nude model, which he considered the "painter's alphabet" and "the foundation of all art," Stauffer-Bern was guided by the same desire "to reproduce the exquisite details of nature, to penetrate the secrets of appearances, and to become a master of what he could see."[15] As a result, his drawings primarily document visual facts, although the sculptural plasticity of his figures also has expressive power (Fig. 22). Weizsäcker considered

Figure 22

Karl Stauffer-Bern, Recumbent Male Nude ,

1881. Pencil, 25.0 × 39.5 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern (A 3461).

Stauffer-Bern's drawings among the best anywhere: "What a joy it was to leaf through the portfolios and sketchbooks in his studio at one's leisure! How . . . the most delicate vibration of form was observed, with what intelligence and at the same time with what energy, often after several new beginnings, until the image had been seized."[16]

Since he was not satisfied with the soft gradations obtainable with the etching needle alone, Stauffer-Bern frequently reworked his plates with the burin to achieve more emphatic contrasts in value. Emulating the Italian engravers of the fifteenth century, he applied the burin so that the hatchings do not follow the round forms of the human body but create shadows with a network of straight, precisely drawn parallel lines.

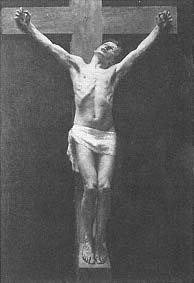

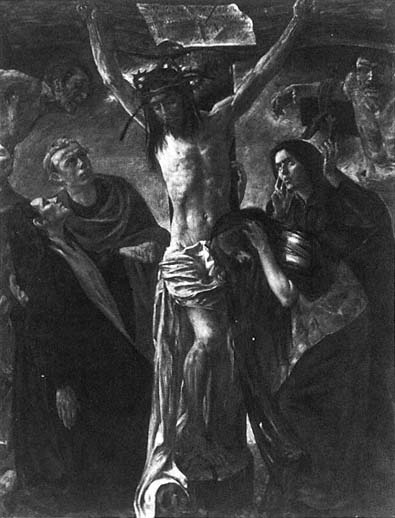

In addition to portraits and nudes, Stauffer-Bern favored religious compositions. A painting representing Christ in the house of Simon the Pharisee was to have been one of his major works. Begun in 1884 on a large scale—the canvas measured approximately eight by sixteen feet and was projected to contain seventeen life-size figures—it was never completed. From 1886 to 1887 he worked on a dead Christ motif inspired by Holbein's picture in Basel, and during the winter of 1887 he painted the Crucified Christ (Fig. 23), an impeccable anatomical depiction of the model, whose brightly illuminated body is set off against a dark ground. Sixteen years later Corinth wrote that this painting was like an "oasis in the desert" for him during that winter, and although by the time he made the statement he had begun to reject Stauffer-Bern's conception as too literal, he professed continued respect for the Swiss artist as a "master of form," emphasizing that the nude human figure could be considered (as he paraphrased Stauffer-Bern himself) the "Latin of painting."[17]

Figure 23

Karl Stauffer-Bern, Crucified Christ ,

1887. Oil on canvas, 247 × 168 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern.

Corinth's contact with Stauffer-Bern, however, was short-lived. Stauffer-Bern tended to be impulsive; he loved to theorize, but without reflecting. According to his biographer Georg Wolf, "Clichés flowed effortlessly into his speech. He preached about art and artistry, demonstrated mature judgment alongside sky-high naïveté, and developed plans on a grand scale for an entire generation of Raphaels and Buonarrotis."[18] Similarly high-flown ideas apparently ended Stauffer-Bern's friendship with Corinth. When on Christmas Eve 1887 he tried to explain to Corinth over a bottle of wine his concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk that—like Klinger's—was to unite painting and sculpture, Corinth bluntly countered by quoting a well-known vulgar line from Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen and left.[19] The two men never saw each other again. In the spring of 1888 Stauffer-Bern left for Rome to devote himself entirely to the practice of sculpture. His unfortunate love affair with Lydia Welti-Escher, the wife of his influential Swiss patron, led in quick succession to his imprisonment and commitment to mental institutions in Rome and Florence and to his suicide at the age of thirty-three on January 24, 1891. Yet despite the brevity of their relationship, Stauffer-Bern had a decisive effect on Corinth's development and continued to influence him for several years. His example encouraged Corinth's own desire to become a "master of form," and the Crucified Christ remained proof that this mastery could be put effectively to the service of a major theme.

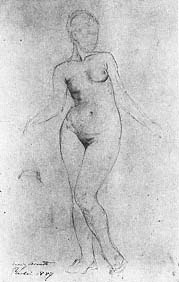

Figure 24

Lovis Corinth, Standing Female

Nude , 1887. Pencil, 52.8 × 34.5 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR).

Figure 25

Lovis Corinth, Standing Female

Nude , 1887–1888. Pencil,

44.7 × 29.5 cm.

Kunsthalle Bremen.

Corinth's Berlin drawings in particular indicate the extent to which he emulated Stauffer-Bern's concept of form. Although relatively few examples have survived, he apparently worked extensively at drawing during the winter of 1887–88. A mise en place sketch (Fig. 24) in the idealizing French manner was probably done soon after Corinth arrived in Berlin. Sweeping reinforced contours define the stereometrically simplified body while a gently swaying line of action proceeds from the model's neck through the navel and pubic area to the inner contour of the left leg. Like Bouguereau's Venus (see Fig. 14), the figure is eight heads high, with the upper and lower portions of the body containing four heads each. By comparison, several drawings in a sketchbook now in the Kunsthalle in Bremen illustrate how Corinth adopted Stauffer-Bern's emphasis on plasticity of form and painstaking verisimilitude. The drawing of a standing female nude (Fig. 25) on folio 3 recto, for example, is superior to any of Corinth's earlier life drawings in accuracy of rendering. The modeling, contained by smooth contour lines, recalls the parallel hatchings in Stauffer-Bern's prints and makes the supple flesh palpable. The woman, directly observed, conveys the sense of a real, living presence. In several drawings in the Bremen sketchbook the anatomical depiction of the model is complemented by careful studies of detail; in others the sculptural clarity of the figure is enhanced by conspicuous shadows, as in similar drawings by Stauffer-Bern.

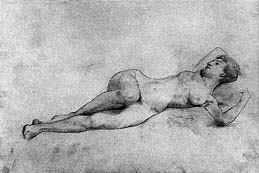

Figure 26

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude ,

1887–1888. Pencil, 29.5 × 44.7 cm.

Kunsthalle Bremen.

Although most of the drawings in the Bremen sketchbook display the same remarkable naturalism, Corinth did not abandon the idealizing tendencies of his French teacher entirely. On the contrary, as his command of life drawing grew, he could not only express the visual data manifested in the model but also achieve a more sophisticated grasp of conceptualized form. His drawing of a reclining female nude (Fig. 26) on folio 28 recto follows the practice of Bouguereau by combining the realistic head of a modern woman with a graceful, idealized body. A transparent chiaroscuro accentuates the soft forms of the model, and delicate flowing contours emphasize the body's sensuousness.

Corinth's works during the Berlin winter culminated in at least two paintings, each depicting a female nude. The smaller of the two (B.-C. 54), dated 1888, is based on a drawing in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg;[20] the other (Fig. 27) bears the date 1887 and was clearly preceded by drawings like the one shown in Figure 26. The 1887 painting is the more finished and more ambitious of the two. The model is shown life-size, reclining on a bed of silky cushions and sheets, her back turned seductively toward the viewer. Both paintings further elaborate Corinth's drawings from life; both are exercises, efforts to endow visual perception with concrete pictorial form. The meticulous and richly nuanced modeling of the flesh parts suggests that these works are those of which Corinth, remembering Bouguereau's criticism of his draftsmanship, later wrote: "I seriously tried to capture the forms by working from the live model; in my pictures there was not to be a speck that was not rigorously studied."[21]

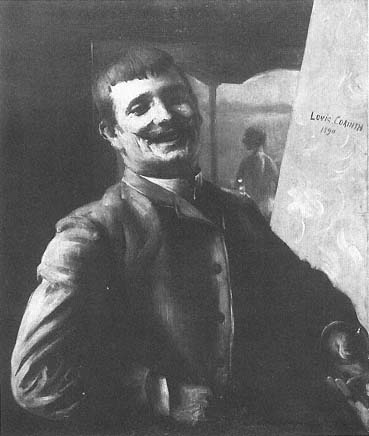

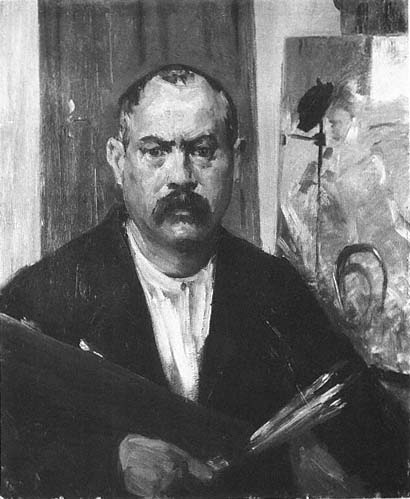

The same disciplined brushwork is seen in the Self-Portrait (Fig. 28) from the winter of 1887–88. Like Stauffer-Bern's portrait etchings, the painting projects the artist's physical presence with "startling" immediacy. Although this

Figure 27

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude , 1887. Oil on canvas, 65 × 175 cm,

B.-C. 53. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

effect results partly from the quizzical, apprehensive gaze, it is reinforced by the tangible life-size head emerging from the undifferentiated pictorial ground. The meticulous modeling is in keeping with Stauffer-Bern's precept that "mathematically precise reproduction of form" is the basis of other, more expressive, qualities in a given portrait. Indeed, more than twenty years later Corinth, commenting on the art of portraiture, restated the precept in his own teaching manual with remarkable accuracy:

A specific individual has here been portrayed, and the first requirement is verisimilitude. Perhaps some will say that in a work of art other qualities could be considered more important, since in most cases only a very few will know the sitter by face. However, such other affective qualities as immediacy of expression and liveliness of conception are only the inevitable result of verisimilitude.[22]

Corinth's awareness of his increasing technical proficiency during the winter of 1887–88 is reflected, at least indirectly, in his decision that his name henceforth should be Lovis. For some time he had been signing his works in capital letters, replacing the U in his first name with the less conventional roman V . He now began using the v for the lower case spelling of his name as well, adopting Lovis as his professional name; legally, however, his name remained unchanged.

In February 1888 Lovis Corinth participated again in an exhibition organized by the Berlin Artists' Association. Two of the paintings he showed, the portrait of a young architect named Tietz, painted the year before, and a picture entitled Hospital Women at Their Morning Prayer , were either destroyed by Corinth or overpainted, and nothing is known about them except what can be

Figure 28

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1887–1888. Oil on canvas,

53.5 × 43.0 cm, B.-C. 49.

Sammlung Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt.

gleaned from a reviewer's brief remarks critical of the forced facial expressions in both works. The third painting was Corinth's seasoned prizewinner The Conspiracy , which once again drew favorable comments.[23]

Corinth's further efforts to establish himself in Berlin were cut short when his father called him home at Easter time. As the portrait from the previous summer suggests, Franz Heinrich was ailing, and the wish to have his son near him was most likely prompted by a further deterioration of his health.

Figure 29

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth , 1888.

Oil on canvas, 118 × 100 cm, B.-C. 56.

Private collection.

Königsberg, 1888–1891

The portrait Corinth painted of his father when he returned home in May 1888, however, gives no indication of Franz Heinrich's illness (Fig. 29). On the contrary, the upright posture and alert gaze convey undiminished physical and mental vigor. The sitter is seen from up close and slightly below, his head turned, almost abruptly, toward the viewer. The raised eyebrows and firm mouth give the face a look of quiet resolve. The resulting effect of controlled tension differs considerably from the calm mood of Corinth's earlier portraits

of his father. Psychic energy emanates from the unfinished work, in which only the face has been given definition—again in emulation of Stauffer-Bern's "mathematically precise" rendering of form. The rest of the portrait is barely sketched out, reinforcing the head as the principal carrier of the picture's expressive content. Corinth apparently began the painting as a more developed statement of the formula he had first adopted in the Berlin self-portrait, and he prepared the picture with special care, as several preliminary drawings show. He may have left the painting unfinished because he could not maintain so energetic a conception in the face of his father's true state of health; perhaps the sittings had to be suspended. In any event, the portrait remains more a wishful projection than a record of fact. Corinth's desire to remember Franz Heinrich as he looked in this portrait—psychologically the most interesting one he painted of his father—is evident from his fondness for it. He kept it with him throughout his life and always had it hung opposite his favorite armchair. "I want to look at the old man," he told his wife many years later; "I think of him each day."[24]

Franz Heinrich's vigorous appearance in the portrait was indeed deceptive. When Corinth returned to Königsberg at the end of September from a month of military reserve duty in the nearby town of Pillau, he found his father severely ill and confined to bed. This is how he painted him in October (see Plate 3). The small, intimate canvas is the best of Corinth's early sunlit interiors—a masterpiece that shows him in complete command of his painterly means. The composition recalls Jozef Israëls's The Widower , which had inspired Corinth's "fledgling work" The Conspiracy . Corinth's sense that the subject fit the anecdotal conventions of late nineteenth-century genre painting is indicated by his own original title for the work, The Sick Man .[25] Unlike Israëls, however, Corinth avoided sentimentality by sublimating his empathy in a loving description of the room and its two inhabitants. Franz Heinrich seems to sleep while the young woman briefly stops knitting to gaze at him. The autumn sunlight gleams on the furniture and on the still life of medicine bottles, glasses, and fresh flowers beside the bed. The small carnation withering on the chair is a poignant reminder of the picture's content. Objectivity and simplicity of conception make this painting the most heartfelt of Corinth's early works. With it he also bade his father a tender farewell: Franz Heinrich died on January 10, 1889, a month before his sixtieth birthday.

Corinth inherited three apartment houses his father had bought in Königsberg in the 1870s as well as other substantial investments. He was now financially secure and independent, a fortunate situation indeed, for so far he had found no buyers for his pictures. He was now free to pursue his career virtu-

ally anywhere. Although he had visited Königsberg only intermittently during the preceding nine years—always to see his father—he decided to stay. His decision most likely had to do with his inexperience in administering and supervising his property, and he no doubt thought it wise not to stray too far—for the time being—from the sources of his income.

Soon after his father's death Corinth rented a studio at Rossgärter Passage 1 and resumed contact with some of his former teachers and fellow students from the Königsberg Academy. He also joined the Königsberg Artists' Association and in March 1889 exhibited with the organization for the first time. In addition to a kitchen still life (B.-C. 68), painted over the ill-fated earlier picture from Antwerp, he showed The Conspiracy once again, although many Königsbergers had already seen the painting on display in the window of the gallery of Bruno Guttzeit, a local dealer. A reviewer of the exhibition noted this with disappointment and chided Corinth for not submitting any of his more recent works from Paris, some of which had also been exhibited at Guttzeit's.[26] Among the "Parisian" works alluded to were most likely Corinth's Berlin nudes. His decision not to show them in the competitive context of the Königsberg Artists' Association exhibition, which included pictures by Lenbach, Böcklin, and Uhde, suggests that he recognized the tentative character of these works.

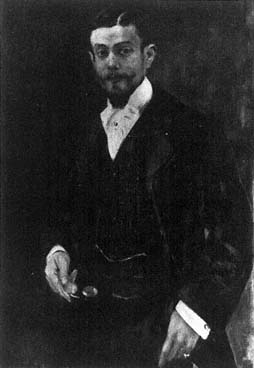

From 1889 to 1891 Corinth assimilated his most recent experiences in Paris and Berlin, further developing ideas he had not yet been able to realize fully. For example, in the portrait of Carl Bublitz (Fig. 30) he built on the conception he had first explored in the Berlin self-portrait and in the May 1888 portrait of his father (see Fig. 29). Now, however, he intensified the impression of immediacy by relating the sitter to the viewer through gesture as well as glance. Carl Bublitz (1866–1932), who had also studied at the Königsberg Academy, is depicted half-length in Corinth's studio; he stands next to an empty canvas, echoing its diagonal position in his own animated posture. In the background is a portion of Corinth's only known plein air picture from this period, Swimming Pond near Grothe, Königsberg (B.-C. 72), also painted in 1890. Bold contrasts of light and shade, induced by the bright illumination from the left, play a major part in the compositional structure of the Bublitz portrait. And the broad, energetic application of the paint itself suggests palpitating life.

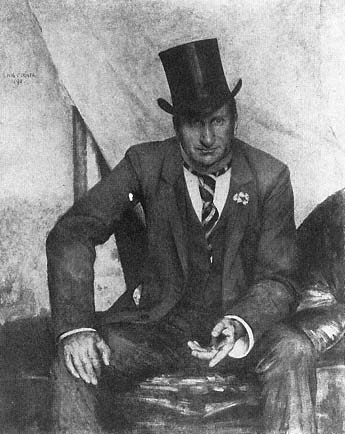

The technique employed in the portrait of Hugo Rogall (Fig. 31), an actor at the Königsberg municipal theater who belonged to Corinth's circle of friends, is more controlled, although here, too, vigorous brushstrokes enliven subordinate areas of the canvas. The conception is as lively as that of the Bublitz portrait, but this sitter's expression and posture are more pointedly provoca-

Figure 30

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Painter Carl Bublitz , 1890.

Oil on canvas, 90 × 74 cm, B.-C. 70.

Sammlung Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt.

Figure 31

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Actor Hugo Rogall , 1890.

Oil on canvas, 75 × 50 cm, B.-C. 71. Only a fragment of this

painting survives; present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

tive. The shallow space and simple background help to focus attention on Rogall, whose nonchalance is reinforced by his open jacket and unbuttoned vest. The top hat, set slightly askew, and the jaunty flower in the lapel add affable touches to the otherwise robust, even aggressive, characterization. Unfortunately, Corinth later cut the painting apart, keeping only the fragment with Rogall's head.

Both of these portraits bring to mind Frans Hals, who used posture and gesture to establish a dialogue between his sitters and the viewer. Corinth most likely drew consciously on the Dutch master in his efforts to heighten the illusion of a momentary encounter in which an individual's character reveals itself in emotion and movement. Although he was to explore such baroque elements more fully later, these two portraits mark the first stage in the development of a flamboyant conception now recognized as a characteristic of Corinth's mature style.

Figure 32

Lovis Corinth, The Old Drinker , 1889.

Oil; ground and size unknown, B.-C. 67.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

The Old Drinker (Fig. 32) of 1889 apparently also has Dutch prototypes. Holding a violin under his left arm, the smiling old man sniffs at a bottle. His contented look evokes the pleasures of both music and drink. Half-length figures of musicians and drinkers, usually shown against a neutral ground, were an invention of the Utrecht Caravaggisti but were also painted frequently by Frans Hals. Opinion differs on what these paintings represent: subjects from daily life or allegories on the popular theme of the Five Senses. In Corinth's painting the allegorical reference to hearing, smell, and taste is clear in the juxtaposition of violin and bottle. In seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of the type the figures usually wear theatrical costumes that suggest their allegorical roles. Corinth updated this tradition by placing his merry toper in a contemporary bohemian context.

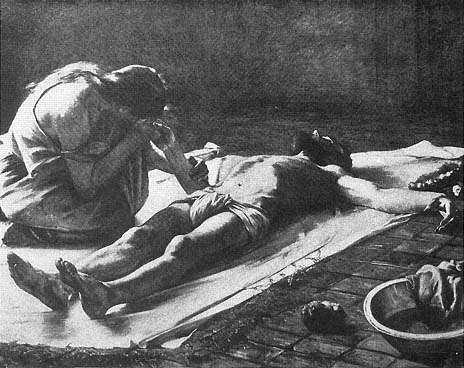

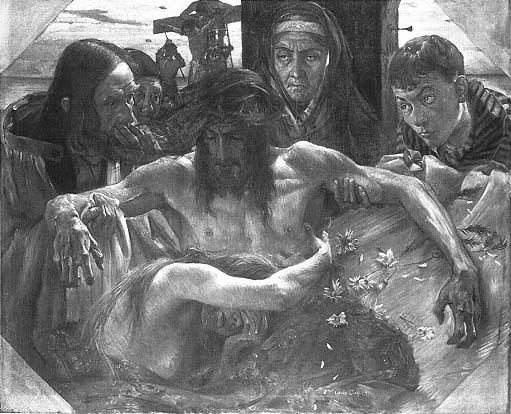

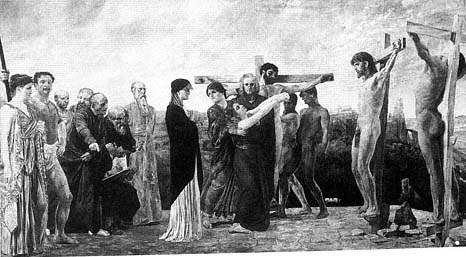

Although The Old Drinker and the portraits of Bublitz and Rogall derive much of their interest from Corinth's empathy with his subject, his figure compositions from these years indicate his continuing preoccupation with pictorial problems he had tried to solve in Munich and Paris. A motif from Paris, "a corpse of Christ on a red tile floor," awkwardly drawn in the Kiel sketchbook (see Fig. 18), provided the inspiration for his first major religious work, the Pietà (Fig. 33) of 1889.[27] As Corinth knew, this weighty subject was certain to attract public attention. Indeed, paintings of the dead Christ, either alone or attended by mourners and deriving, more or less, from the time-honored tradition of Hans Holbein and Annibale Carracci, were featured so prominently in nineteenth-century exhibitions that even Manet succumbed,

Figure 33

Lovis Corinth, Pietà , 1889. Oil on canvas, 131 × 163 cm, B.-C. 61.

Formerly Kaiser Friedrich-Museum, Magdeburg; destroyed 1945.

Photo: Bruckmann.

submitting a Dead Christ with Angels (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) to the Salon in 1864.

In addition to Löfftz's Christ Lamented by the Magdalene (see Fig. 9) and Jean-Jacques Henner's various interpretations of the theme, Corinth may have known Böcklin's Mourning Magdalene (1867; Kunstmuseum, Basel) as well as Trübner's Christ in the Tomb (1874; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich).[28] Like Böcklin and Löfftz he paired the dead Christ with the distraught Magdalene rather than the more conventional figure of Mary. The composition, however, clearly derives from Karl Stauffer-Bern. The diagonally foreshortened figure of the male model, of which Corinth also made a preliminary oil sketch (B.-C. 60), recalls Stauffer-Bern's drawing of 1881 (see Fig. 22), and no doubt the Swiss artist's preoccupation with religious themes during the winter of 1887–88 encouraged Corinth to return to a subject that had first claimed his attention at the Académie Julian.

Seen from above, the pictorial space in the Pietà is coextensive with the viewer's own, setting the stage for an empathic experience. The naturalistic figures, illuminated by the bright light from the upper left, lend the scene a

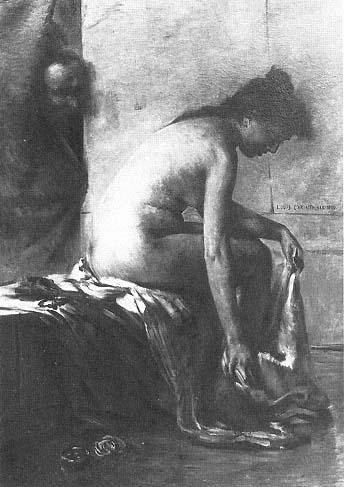

Figure 34

Lovis Corinth, Susanna in Her Bath , 1890. Oil on canvas,

159 × 111 cm B.-C. 74. Museum Folkwang, Essen

(Gertrud und Wilhelm Giradet Familienstiftung) (349).

startling and unsentimental immediacy. Indeed, a closer examination of Corinth's conception reveals less concern for emotive content than for pictorial structure. The complex pose of the Magdalene and the foreshortened figure of Jesus—set off against the white cloth and the pattern of the tiled floor—are too carefully staged to be convincing in more than formal terms. Yet the contrived composition fulfilled Corinth's highest hopes. Having exhibited the painting in Bruno Guttzeit's gallery in 1889, he sent it to the Paris Salon in 1890, where it was not only accepted but awarded the "so ardently desired" mention honorable .[29]

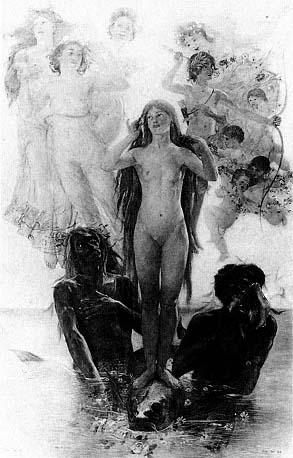

Susanna in Her Bath of 1890, best known today through the somewhat more freely painted but contemporary second version of the picture in the Museum Folkwang (Fig. 34), was also conceived with the typical Salon public in mind and, like the Pietà , can be traced to Corinth's student years in Paris. The composition depends on Henner's painting of the same subject (c. 1863; Musée d'Orsay, Paris), which Corinth knew from the collection in the Musée du Luxembourg. Like Henner's painting, the Susanna is a standard academic study from life that has been given a biblical meaning with the addition of a few anecdotal accessories. The wall in the background and the curtain through which the lecherous bearded elder peeks delimit the pictorial space and provide an effective foil for the nude body of the model.

Emboldened by the favorable reception of the Pietà and possibly hoping to repeat or even improve on his earlier success, Corinth sent the Susanna to the Paris Salon in 1891. This time, however, he was less fortunate, although the painting was accepted—in itself no mean achievement considering the large number of works usually rejected by the jury. No doubt the very acceptance of the painting further convinced Corinth that public approval of his work depended on his producing compositions that demonstrated his technical abilities in the context of a "significant" theme.

The seated male nude in The Prodigal Son (Fig. 35), painted in 1891, is also still recognizable as a studio model, although here the treatment of the anatomy is woefully inadequate. The limbs are far too long, and even the disheveled heap of straw on which the figure sits cannot disguise the awkward connection between the upper and lower parts of the body. There is also a stylistic dichotomy between the meticulous modeling of the flesh parts and the atmospheric rendering of the rest of the picture (the straw-covered ground and the pigs, for example, are sketchily painted). The lower left corner of the pigsty is taken, without modification, from Corinth's early canvas Cowbarn (B.-C. 2), painted at his uncle's farm in Moterau in 1879. Many years later Corinth himself made fun of the technical discrepancies of the 1891

Figure 35

Lovis Corinth, The Prodigal Son , 1891. Oil on canvas,

112 × 154 cm, B.-C. 81. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Marburg/Art Resource, New York.

painting when he confessed in a letter to his wife, written on January 26, 1903, that the pigs were really the best part of the picture.[30]

Despite the stylistic ambiguities and the odd handling of the nude model, the painting is of special interest, for in it Corinth may have intended more than merely to solve an academic pictorial problem within a well-known thematic context. It has been suggested, for instance, that in placing the biblical character in a peasant milieu he knew intimately, Corinth may have reflected his own sense of professional and personal isolation.[31] This suggestion merits serious consideration, for despite the honorable mention awarded him by the Salon jury in 1890, in far-off Königsberg Corinth had not achieved professional security. He exhibited regularly with the Königsberg Artists' Association and at Guttzeit's gallery, to be sure, but critics generally qualified their praise of his work. They commented favorably on his technical skill and acknowledged his success in Paris with a measure of pride. But a critic for the Hartungsche Zeitung , for instance, writing in the May 5, 1891, issue, noted that despite a remarkable technique, Corinth followed the beaten track so lazily that one should expect little of him in the future.[32] Moreover, considering that his father's death had left Corinth without his only moral support, it is not farfetched to assume that the Prodigal Son, remorseful in his loneliness, had a personal meaning for the painter.

Figure 36

Lovis Corinth, Learn to Suffer

without Complaining , 1891.

Crayon, sheet 52 × 34 cm, image

34.0 × 22.5 cm. Private collection.

Photo courtesy Thomas Deecke.

Although Corinth explored the extended meaning of literary subjects only much later, in one composition at this time, awkwardly titled Learn to Suffer without Complaining , he expressed himself allegorically. Corinth first exhibited the large painting in September 1891, and although it was seen at the Berlin Secession as late as 1918, when the misery of the First World War gave the subject renewed meaning, the only evidence of the picture today is a preliminary sketch (Fig. 36).[33] The title derives from what the German emperor Friedrich III allegedly said to his son Wilhelm, who was born with a crippled arm; the picture itself was apparently inspired by the memory of the tragic and premature death of the emperor in 1888. An enlightened and cultured monarch whose ascension to the throne had been anticipated with great hope by a large part of the German nation, Friedrich died of throat cancer after a reign of only ninety-nine days. In Corinth's preparatory study the emperor, accompanied by an angel, stands beneath the crucifix in the place traditionally reserved for John the Evangelist in religious compositions of this type. Gazing at the cross, the emperor accepts Christ's death with reverence and resignation. In the context of Friedrich's own suffering, the idea that Corinth undoubtedly wished to convey here is that of an imitatio Christi . For the posture and gesture of the emperor as well as the design of the armor, however, Corinth relied again on his memories from Paris, since he took these de-

tails, with little change, from Rubens's painting of the presentation of Marie de' Medici's portrait to King Henry IV of France, part of the famous allegorical cycle now in the Louvre.[34]

Corinth may have had his most satisfying intellectual exchange during these years when the Berlin painter Walker Leistikow spent some time in Königsberg in 1890 working on a panorama of the city. The two men had met briefly in Berlin during the winter of 1887–88. In the course of Leistikow's visit their acquaintance developed into a lasting friendship. Leistikow surely gave Corinth an up-to-date account of recent artistic developments in Berlin. He may also have encouraged him to look anew beyond the borders of East Prussia. Corinth's success with the Pietà in Paris finally seems to have convinced him that Königsberg could never offer him even a remotely comparable forum. Thus in the fall of 1891, having found a custodian for his property, he returned to Munich. By the beginning of October Corinth was settled in a spacious studio at Giselastrasse 7, in the city's Schwabing district. He was not to exhibit again with the Königsberg Artists' Association until 1899.

A Swarming Beehive

In his memoirs Corinth compared Munich's artists' community in the 1890s to a "swarming beehive" whose occupants kept searching restlessly for new territory.[35] This appraisal is confirmed by the architect August Endell, who described with astonishment the seemingly endless variety of works exhibited in the Bavarian capital in 1896:

So many teachers, so many different ways to paint, and theories as plentiful as sand in the sea, one more eccentric and weird than the other. . . . This one wants Greek noses and garments; that one, large philosophical compositions; a third, history paintings; a fourth, village scenes. There are those who insist on plein air and still others who know how to speak profoundly about light and dark. In addition, there is socialism, poor-people painting, mysticism, and symbolism. Everybody has a different ideal.[36]

Diversity, however, was not new to Munich painting in 1896. Although the annual exhibitions at the Glass Palace and the periodic international exhibitions, both sponsored by the conservative Munich Artists' Association, continued to be dominated by the Munich Academy, by the 1880s a number of

fads had made themselves felt, usually begun by artists who had won special acclaim at one of these exhibitions. Bastien-Lepage's painting The Beggar (1881 Salon; Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), for instance, shown at the international exhibition of 1883, inspired works of social content that haunted many a Schwabing studio until 1887, when the idyllic landscapes of the Scottish painters James Guthrie and David Cameron generated a new fashion.[37] The international exhibition of 1888 still gave prominence to naturalistic subjects, but the following year a new kind of idealism emerged, exemplified by the arresting imagery of Arnold Böcklin. Böcklin, condemned a few years earlier as a "fanatic of the hideous and the bizarre" and reviled for depicting "coarse, base emotions reminiscent of the lowest strata of human sensuality,"[38] showed seventeen paintings at the Glass Palace, including his fierce Battle of Centaurs (1873; Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Kunstmuseum). The 1889 exhibition marked the beginning of Böcklin's fame. Soon he was compared to Goethe, Beethoven, Rembrandt, and Phidias and celebrated as the "Shakespeare of painting."[39] The Böcklin cult ultimately reached ridiculous proportions. Soon after the painter's death in 1901 the Berlin critic Hans Rosenhagen wrote with unsurpassed hyperbole: "Böcklin was a hero, he belonged to a divine race[,] . . . he is eternal . . . [and] stands lonely above mankind. Past, present, and future merge in his heart. An extension of the cosmos, he encompasses all being."[40]

At the same exhibition in 1889 the young painter Franz von Stuck won a gold medal and a prize of sixty thousand marks for his Guardian of Paradise (1889; Stuck-Jugendstil-Verein, Munich). Whereas Böcklin's naturalism invests his hybrid mythological creatures with an astonishingly real, palpable presence, Stuck's synthesis of the real and the ideal in subject and form relies on naturalistic devices and emblem-like simplifications. The space in his painting is at once atmospheric and flat; the figure of the angel is carefully modeled yet silhouetted as a bold, simplified design. Although Stuck soon followed Böcklin's example and produced a series of strikingly naturalistic images of nymphs, satyrs, and fauns, he also continued in such works as the demonic Sin (Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich), painted in 1893, to employ—as in Guardian of Paradise —a mixture of naturalism and stylization.

During the 1890s the reputation of Klinger and Uhde also rose. Only a few years earlier their ideal subjects had been greeted with skepticism because, like Böcklin's, they did not meet conventional standards of beauty.

Böcklin, Klinger, Uhde, and Stuck suddenly became popular during the last decade of the nineteenth century because these artists satisfied a bur-

geoning need for a "heightened" reality that was part of a broad antiscientific movement in both art and philosophy. This development, eventually felt throughout Europe, originated in France. As early as 1884 the novelist and critic Joris-Karl Huysmans has des Esseintes, the hero of his novel A rebours , raise an angry voice against the contemporary infatuation with naturalism: "Nature has served her purpose [and] by the disgusting uniformity of her landscapes and her skies has . . . worn out the attentive patience of the refined. . . . the time has come when nature should be replaced with artificiality as far as possible."[41] Two years later Jean Moréas's manifesto Le symbolisme turned against naturalistic writers such as Emile Zola by announcing the advent of literary symbolism in French literature. Like Henri Bergson, who believed intuition the fundamental source of human knowledge, Moréas and his friends were convinced that only the world of ideas offered artists the superior reality they were charged to evoke and to depict. In Germany the novelist and playwright Hermann Bahr echoed this belief when he informed his readers in 1891: "The rule of naturalism is over, its time is up, its magic dispelled, . . . we want to get away from naturalism and reach beyond it."[42] With growing frequency German critics joined the refrain. "Tear off the materialistic blinders; let allegory, the stories of the Bible, Homer be our guides in a world of greater beauty and lofty thought."[43]

Despite the similarity of the rhetoric, these ideas manifested themselves in French and German painting in fundamentally different ways. Whereas most French Symbolists reacted against Impressionism, a movement that had never taken root in Germany, German idealists rebelled against naturalistic and academic landscape and genre painting. Because German artists bypassed the critical intervening stage of Impressionism, with concern for bright color and simplified design, many of their works from the 1890s are ambivalent. Some of them began by emulating Stuck's precarious synthesis and eventually embarked on a process of rigorous stylization that was to culminate in the German Jugendstil version of art nouveau. Many others followed the new vogue for the meaningful theme, but, like Böcklin, Uhde, and Klinger, clothed their ideal subject matter in the naturalistic form prevalent during the preceding decades.

In Munich these diverse trends acquired an unexpected forum with the founding of the Munich Secession in 1892,[44] an event that plunged Schwabing's artists' community into turmoil. The Munich Secession brought together artists dissatisfied with the exhibition policies of the Munich Artists' Association, policies jealously guarded by the city's "painter prince" Lenbach. They felt that the annual exhibitions at the Glass Palace were unjustifiably parochial

and included far too few works of true merit. Foreign artists, for instance, were invited only to the special international exhibitions that were generally held every four years. The Secessionists had three major goals: smaller exhibitions, works of higher quality, and annual participation by artists from abroad without regard to their form of artistic expression. The founding members of the Munich Secession were themselves a heterogeneous group. They included, besides Uhde and Stuck, Peter Behrens, Otto Eckmann, Thomas Theodor Heine, Adolf Hölzel, and Wilhelm Trübner. Their first exhibition, which opened June 15, 1893, in a newly erected building at the corner of Prinzregentenstrasse and Pilotystrasse, featured, in addition to their own work, paintings by such diverse artists as Böcklin, Liebermann, Puvis de Chavannes, Degas, Monet, and Carrière. In short, the Munich Secession accommodated virtually everything from Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism to Symbolism and the budding Jugendstil movement.

Petty jealousies explain why several Secessionists, including Behrens, Eckmann, Heine, Trübner, and Schlittgen as well as Carl Strathmann and Max Slevogt, decided later the same year to form a separate Free Association.[45] Through Eckmann they secretly arranged with their old enemy, the Munich Artists' Association, to exhibit independently as a group under the auspices of the association's official program at the Glass Palace. When these plans were discovered, the Munich Secession reacted sharply to the defection and promptly purged its ranks of the offenders. Under pressure from conservative members, the Munich Artists' Association, in turn, was forced to withdraw its permission to exhibit at the Glass Palace, and the renegades thus found themselves between opposing camps. The Free Association was never successful. It held one exhibition in Munich and another, in the fall of 1894, at the gallery of Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin. Interestingly, future exhibitions were to have included a number of French painters of the avant-garde, as Eckmann informed Trübner in a letter dated February 21, 1894. According to this letter, Eckmann had contacted two indépendants who had promised to arrange for the submission of works by Anquetin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin, Denis, and others.[46] Although these names reveal Eckmann's own antinaturalist bias, the Free Association too was made up of artists pursuing a wide range of pictorial expression. Eckmann, whose work showed a growing tendency toward Jugendstil , and Trübner, a realist in the Leibl tradition, merely represent the divergent poles.

No wonder Corinth, who had just left the staid provincialism of Königsberg, compared the Munich art scene to a "swarming beehive." And as if his creative energy had been dammed up far too long, he joined passionately, if

not altogether altruistically, in the controversies surrounding the Munich Secession and the ill-fated Free Association. "I was happily carried along in this stream," he recalled in his memoirs, "proud to be respected as yet another voice. Moreover, I had the intuitive feeling that as part of this clique I would be able to get ahead."[47]

As a founding member of both the Munich Secession and the Free Association, Corinth entered on a period of cultural politics that for the first time in his career not only brought him face to face with a variety of modern trends but also placed him in a competitive situation bound to make him keenly sensitive to the goals of his own art. The fiasco of the Free Association gave added direction to his intellectual development. After that episode had pitted him against both the Munich Artists' Association and the Munich Secession, he found more congenial company in the literary world. One of his closest friends at this time was the Bavarian satirist Joseph Ruederer, who lived one floor below Corinth's studio on Giselastrasse. Ruederer himself was the center of a lively literary circle that included Max Halbe, Otto Erich Hartleben, Eduard von Keyserling, and Frank Wedekind. The novels and plays these men wrote were often given a first reading at informal gatherings. Corinth, for instance, was present at the Café Minerva when Wedekind read from his play Sonnenspektrum , and he also attended the tumultuous premier of Erdgeist , the first of Wedekind's Lulu plays. Corinth's own impulse to write, which eventually developed into a lifelong labor of love, clearly dates from these years, for he began the first draft of his autobiography in 1892.

Corinth's output increased markedly in the 1890s, and the works he produced then reflect the artistic and intellectual milieu in which he lived. They are indebted to several different models and vary greatly in subject matter, conception, and execution. They also contain the seeds of elements that by the end of the decade constituted the main features of a distinct style: a highly energized and mood-inducing painterly treatment, audacious eroticism, and deep psychological insight.

Diogenes

Corinth's first major painting from Munich, Diogenes (see Plate 4), was the most ambitious composition he had ever attempted, with no fewer than twelve almost-life-size figures. Although the canvas bears the date 1892, Corinth must have begun work on it soon after his arrival from Königsberg, for

the picture was being exhibited at the Munich Glass Palace by the end of 1891. The painting depicts the Cynic in the Athenian marketplace, his lamp lit in daylight, as he searches "for an honest man." The subject was especially popular in seventeenth-century Flemish painting. Jordaens depicted it several times, most notably in the large canvas now in Dresden. Corinth's version, however, recalls a lost composition by Rubens, a workshop copy of which is preserved in the Louvre. Corinth's intention to demonstrate again, as in the Pietà , his mastery of a large figure composition is evident from the calculated grouping of the figures so as to achieve a variety of postures and textures. Diogenes stands alone, holding up his lamp; the reactions of the eight figures before him range from amused curiosity to outright derision. The postures and gestures of the two naked urchins in the left foreground are sequential, the one leaning forward, supporting his hands on his knees, the other standing upright with arms upraised. The young woman in the center continues the movement, leaning back as she shields her mocking expression with her forearm. The picture opposes old faces to young ones, clothed figures to nudes. Diogenes' weathered old skin contrasts with the youthful skin of the two boys before him. The simplified figures of the nude children in the background similarly correspond to one another. As in the Pietà , the figures are illuminated by a strong light from the upper left. Rejecting the idealism with which subjects like this one were traditionally rendered, Corinth, moreover, went so far as to introduce figure types that might have been found in a Munich market square in the 1890s: the old woman with the basket and the couple standing at the far left. In recasting the subject in a naturalistic form, Corinth, like Böcklin, did not hesitate to translate the heroic into the commonplace. And Corinth's Diogenes , like Böcklin's work, was not accorded an entirely favorable reception. Indeed, one critic was so horrified by the bluish skin tones of Corinth's figures that he warned of the imminent demise of German art.[48]

Belated Responses to Munich Realism

The events surrounding the founding of the Munich Secession in 1892 brought Corinth into close contact with Wilhelm Trübner. Trübner, the only painter of the original Leibl circle still working in Munich, willingly shared his insights and knowledge with younger colleagues. As Corinth wrote in an article first published in 1913, he came to regard Trübner almost as a teacher: "I could

almost pride myself having been his pupil, if one can so call a relationship in which the older artist, drawing on his rich experience, generously gives advice to the younger, who respectfully follows such counsel."[49]

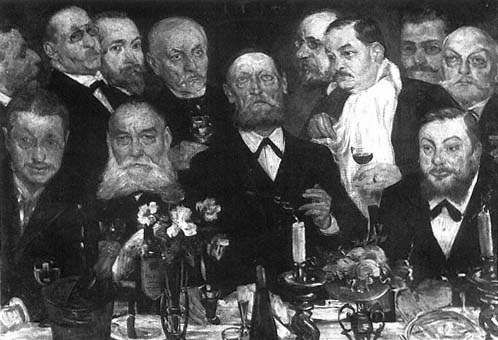

Through Trübner, Corinth was finally introduced to Munich realism of the 1870s, and several of his paintings from 1892 attest to this belated encounter with the Leibl tradition. One of these is the portrait of the landscape painter Benno Becker (see Plate 5). The modeling, especially in the face, is firm, and the dominating gray and white tones are subtly nuanced. Like Leibl's reverie pictures, which are themselves indebted to such French antecedents as Courbet's After Dinner at Ornans (1848; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille), the painting is half portrait and half genre subject. The sitter's actions emphasize the anecdotal conception of the painting, in contrast to Corinth's two preceding artist portraits of Carl Bublitz and Hugo Rogall (see Figs. 30, 31), in which the postures and gestures underscore the Bohemian character of the individuals portrayed. Yet the 1892 portrait does not lack characterization. The comfortable ambience reinforces the easygoing manner of the sitter; his amused expression suggests a perceptive, if somewhat irreverent, intelligence. Virtually forgotten today, Benno Becker (b. 1860), a native of Memel, was about two years younger than Corinth and played an active role in the Munich artists' community in the 1890s. He was the secretary of Allotria, the social club of the Munich Artists' Association, and later served as secretary of the Munich Secession. He had studied archaeology and art history and also had literary ambitions, writing for both Die Freie Bühne and Pan . His contributions to the festivities at Allotria include a parody of Goethe's famous Faust monologue that casts Corinth in the role of the seeker of knowledge and truth—pursuing far more earthly pleasures than Goethe describes.[50]

Corinth's encounter with the legacy of the Leibl circle led him to rededicate himself to subjects inspired by his environment and heightened his awareness of pictorial realism as a function of the medium itself. Several of his paintings from 1892 are technically similar to the portrait of Benno Becker. They include Woman from Dachau Knitting (B.-C. 93) and Old Men's Home in Kraiburg (B.-C. 94), both of which evoke the stillness and rural simplicity that pervade the interiors Leibl had painted during the 1870s and 1880s in Bavarian villages. Other paintings signal a growing reliance on a rapid, sketchy execution that, while still in the service of description, plays more than a purely illustrative role. At the Breakfast Table (Fig. 37) is one of these pictures. Here the paint has been applied freely, and the shapes have been simplified and blocked out in bold brushstrokes. Corinth painted the picture during one of his visits to the small Bavarian town of Dachau, where in 1888 Arthur Lang-hammer together with Adolf Hölzel and Ludwig Dill had founded the artists'

Figure 37

Lovis Corinth, At the Breakfast Table , 1892.

Oil on canvas, 113 × 95 cm, B.-C. 92.

Private collection.

Photo courtesy Eberhard Ruhmer.

group Neu-Dachau. The painting ostensibly depicts Arthur Langhammer (1855–1901), at left, in the company of another painter named Brand,[51] whose identity, however, is not known. What interested Corinth here was neither the individuality of the two men nor the specifics of the setting but the atmospheric ambience of the room, whose smoky air is as tangible as the light that reflects off the objects on the table. Seen against the bright expanse of the window, the faces of the sitters show relatively little detail. Only Langhammer's dog Hipp, whom Corinth commemorated the same year in a separate painting (B.-C. 91), retains his characteristic expression and appearance.[52]

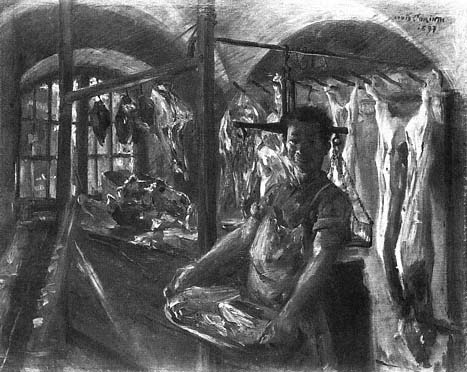

In the small picture of a slaughterhouse interior (see Plate 6) the sketchy brushwork acquires the visceral expressiveness now recognized as a distinctive feature of Corinth's mature style. Although the painting emphasizes the physical action of the butchers who skin and dress the slaughtered animals, their activity is subordinated to the life of the colors, shades of red shot through with blue, green, yellow, and white. The suspended carcasses dominate the composition, and the swirling brushstrokes, as suggestive as they are descriptive, unify the canvas. In the bright light from the window at the back of the room, the blood rising from the floor and the opalescent entrails give off palpable heat and smells.

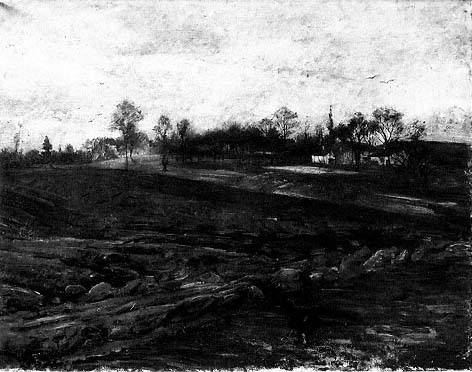

First Major Landscapes

Corinth's tendency to subordinate individual forms to a larger whole may have been a consequence of his growing interest in landscape painting. For in outdoor light he faced a wealth of nuances that demanded to be unified within a broad spatial concept. He responded with vibrant tones that translate light and atmosphere into elements of pictorial energy. Corinth's earlier landscapes are informal studies, undertaken largely as exercises. His landscapes from the 1890s, by comparison, result from a serious and sustained commitment to plein air painting.

Corinth's major landscapes begin with the view he painted in the autumn of 1891 from the window of his studio (see Plate 7). With this painting he continued the German Romantic theme of the "open window," though his reinterpretation of the subject is prosaic, like Menzel's window views in Berlin and Winterthur. Across the gardens and fields that at the time gave Schwabing a rural character, the view extends to church towers and smoking chimneys in the distance. White patches of an early snow intermingle with the green of the meadows, and in the humid air the soil and trees take on a reddish tone. The simplified composition evolves from variations of the surface texture, and both the direction of the brushstrokes and the impasto of the swiftly applied patches of color suggest that the motif was constructed right on the canvas.

Most of Corinth's landscapes from this time were painted during the summer months he spent in the picturesque countryside near Munich. They show a considerable debt to the paintings of the Barbizon school, which after the international exhibition in 1869 had helped to redirect Munich landscape painting, encouraging a more intimate conception of nature in contrast to the

Dutch-inspired vistas popular during the first half of the century. The painters of the Leibl circle, in particular, gave the simplest motif—a clearing in the underbrush or a cluster of shrubs and trees by a brook or a pond—careful and sympathetic attention. Corinth's forest interiors from this time show a similarly circumscribed view. One, the splendid picture now in Dachau (Fig. 38), is painted so freely that the canvas is almost a flickering patchwork of brushstrokes. The others are more controlled and elegiac in mood. The technical and expressive range of these landscapes is illustrated by the painting in Dachau and the Large Landscape with Ravens (Fig. 39) of the same year. The forest scene is a spontaneous visual response to the evanescent effect of bright sunlight breaking through foliage; the landscape indicates a more deliberate approach, with its simplified composition and the predominant shades of purple that reinforce the autumnal mood. As in Caspar David Friedrich's well-known picture in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, Hill and Ploughed Fields near Dresden (c. 1830s), which Corinth's landscape also resembles structurally, the ravens settle on the harvested fields like harbingers of winter and approaching death.

Corinth's melancholy conception was apparently inspired by the moody landscapes of Walter Leistikow (1865–1908), with whom he sometimes painted in the fall of 1893 near Dachau and at the Starnberger See. Earlier in the year Leistikow had been to Paris, where he was deeply moved by a performance of Maurice Maeterlinck's Pelléas et Mélisande at Lugné-Poé's newly opened Théâtre de l'Oeuvre. Summarizing his impressions of the play, he wrote in the July issue of Die Freie Bühne : "I do not know of anyone who can wield the brush better than this poet. His works are spoken painting. And this performance is one of the greatest works of painting the modern period has brought forth."[53] At the time, Leistikow himself was in the process of abandoning his naturalistic approach to landscape painting in favor of a more evocative rendering. Using simplified patterns of muted colors, he gradually evolved a pictorial language that conveys a gentle and somber mood, as in his landscapes of the Grunewald (Fig. 40), in which dark groups of trees stand silently, silhouetted against the sky and reflected in the waters of a quiet lake or pond.

Leistikow's influence is also evident in the haunting Fishermen's Cemetery at Nidden (see Plate 8), painted in the summer of 1894 when Corinth traveled to East Prussia and the Baltic seashore. The melancholy character of the painting derives not only from the motif but also from the pictorial elements. As in the autumnal landscape in Frankfurt, purplish tones dominate the variegated colors of the sandy soil. Most of the crosses are painted in somber shades of blue

Figure 38

Lovis Corinth, Forest Interior near Dachau , 1893. Oil on canvas, 67 × 86 cm, not in B.-C.

Kunstsammlungen der Stadt Dachau.

Figure 39

Lovis Corinth, Large Landscape with Ravens , 1893. Oil on canvas, 94.5 × 120 cm,

B.-C. 100. Städelsches Kunstinstitut Frankfurt (1912).

Photo: Ursula Edelmann.

Figure 40

Walter Leistikow, Lake in the Grunewald , c. 1895. Oil on canvas,

167 × 252 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie (DDR).

and brown. Only one grave is still tended; the others lie neglected. Here and there flowers survive among the weeds. There is a strangely anthropomorphic quality to the crosses, which almost seem to gaze out to sea. As in the paintings by Caspar David Friedrich in which human figures, seen from the back, stand transfixed before nature, the viewer's feelings are directed beyond the graves to the open water, where boats glide smoothly along the shore.

Otto Eckmann and Carl Strathmann

Leistikow's evocative approach to landscape painting touched Corinth at a point in his development when two other friends, Otto Eckmann (1865–1902) and Carl Strathmann (1866–1939), both members of the Munich Secession and subsequently the Free Association, were evolving a radically simplified vocabulary of form. Although Corinth's own creative impulses pointed toward an ever more energetic naturalistic conception, he had some sympathy for his friends' increasingly linear inventions.

Eckmann's early paintings are landscapes similar to Leistikow's in form and expression. But after 1890 he simplified the forms of nature in a way that reveals a strong predilection for ornament. The Four Ages of Man (present where-abouts unknown), six panels completed in 1894, was one of his most ambitious works. To demonstrate the parallelism between the life of nature and of man, Eckmann set each of the four inner scenes in an appropriate season of the year and in the outer panels depicted emblematic images of the beginning and end of life: a young plant rising under the first rays of the springtime sun and a dying plant in a winter landscape. With naturalistic modeling and emphatic contours Eckmann trapped the individual forms in a shallow, tapestry-like space. The Four Ages of Man turned out to be his last painting. In 1893 Justus Brinckmann, then director of the Museum for Arts and Crafts in Hamburg, had introduced Eckmann to Japanese woodcuts. Their simplified drawing and compositional devices so affected the painter that on November 27, 1894, he auctioned off his entire oeuvre and devoted himself henceforth to the art of graphic design. Many of his woodcut illustrations were published in such journals as the erudite quarterly Pan and the popular Munich weeklies Jugend and Simplizissimus . From evocative lines and arabesques Eckmann developed a repertory of forms that came to be known as floral Jugendstil because of its stylized flowers and plants. The style influenced a host of German designers.[54] According to Ahlers-Hestermann, Eckmann had read Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Kant and in general was "spiritually more demanding than his easily satisfied colleagues."[55] An analogous pictorial rigor distinguishes

Figure 41

Carl Strathmann, Salammbô , 1894–1895.

Mixed media on canvas, 187.5 × 287.0 cm.

Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar.

Eckmann's abstractions, especially in comparison with the bizarre imagery of Carl Strathmann.

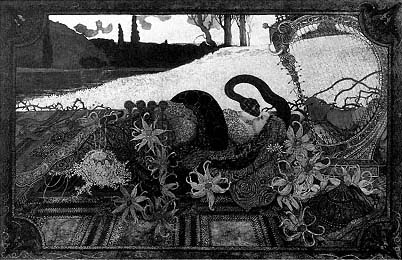

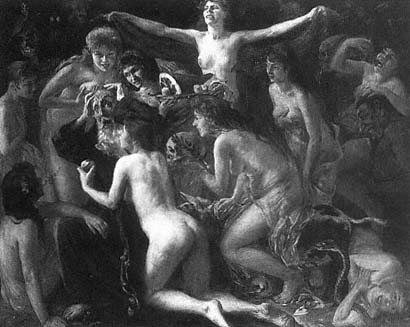

Strathmann's curious work occupies an intermediate position between the art of painting and the crafts. His paintings are strange concoctions studded with colored glass and artificial gems, foreshadowing similar extravagances by the Viennese Jugendstil painter Gustav Klimt. In Strathmann's painting Salammbô (Fig. 41), inspired by Flaubert's novel, the Carthaginian temptress reclines on a carpet spread out on a flower-strewn meadow. Swathed in veils whose design is as complex as that of the harp beside her head, she submits to the kiss of the mighty snake that encircles her. Corinth described how Strathmann, while working on the large picture, gradually covered the originally nude model with "carpets and fantastic garments of his own invention so that in the end only a mystical profile and the fingers of one hand protruded from a jumble of embellished textiles. . . . colored stones are sparkling everywhere; the harp especially is aglitter with fake jewels." According to Corinth, Strathmann knew "how to glue and sew" these on the canvas "with admirable skill."[56]

Tragicomedies

As Corinth's three closest friends embarked on their individual pictorial explorations, Corinth himself experienced a minor crisis that made him unusually receptive to their experiments. Still dissatisfied with his handling of anatomy in Diogenes and the Pietà , he felt he needed further practice in drawing from the live model. Eckmann, whom Corinth fondly remembered as his "spiritus rector," who supported and steadied him whenever he was in danger of losing his footing,[57] suggested that he try making some prints; Corinth began a series of studies that eventually resulted in his first graphic cycle, Tragicomedies , nine etchings completed in 1893 and 1894. Working "daily, for months on end, . . . with individual figures and groups of several models," he was so taken with this project that he, too, was tempted to give up painting for good.[58] Corinth had in mind for the cycle motifs of "eccentric originality," as he put it, with which he hoped to astonish and impress his colleagues.[59] His professed intention explains both the odd emblematic details in some of the compositions and the farcical tone that turns each episode into a true tragicomedy, no matter how serious the subject. The cycle has no thematic unity. Instead, the illustrations follow in random succession.

The first etching in the series, Walpurgis Night (Fig. 42), is based on Goethe's description of the witches' nocturnal ride to the Brocken, their annual meeting place in the Harz Mountains. Faintly visible in the background, old Dame Baubo on her sow and several other shadowy figures on brooms hurry through the sky as four youthful witches, accompanied by a flock of ravens, encircle a skull suspended in midair. A shooting star streaks through the sky at the upper right. Surviving drawings for the cycle indicate that Corinth prepared the etchings with considerable care. He began with quick preliminary sketches and then drew the individual figures from the model, subsequently incorporating these studies into a more finished composition drawing for transfer to the copper plate. In Walpurgis Night the postures of the floating witches can still be recognized as positions assumed by the models in the studio, standing, sitting, or lying down. There is special emphasis on the contours, and strong contrasts of light and shade render the major figures fully tangible. The composition itself, however, is simplified and derives its effect from the silhouette formed by the interlocking figures. This stylistic ambivalence recalls Stuck's Guardian of Paradise , and in the second etching of the cycle, Paradise Lost (Fig. 43), the angel's arm from Stuck's painting reappears with only minor modifications. As in the preceding print, the fully modeled figures form a striking pattern against the white paper ground.

Figure 42

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Walpurgis Night , 1893.

Etching, 34.2 × 41.7 cm, Schw. 5 II.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/5).

Figure 43

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Paradise Lost , 1893.

Etching, 35.0 × 41.8 cm, Schw. 5 III.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/4).

Figure 44

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: The Temptation of

Saint Anthony , 1894. Etching, 34.3 × 42.2 cm., Schw. 5 IV.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/8).

Figure 45

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: The Women of

Weinsberg , 1894. Etching, 35.0 × 42.5 cm, Schw. 5 VII.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/6).

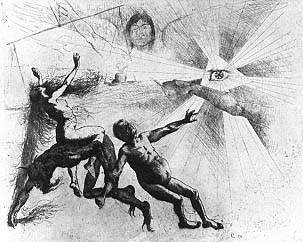

Here, however, the stylistic ambiguity of the composition is intensified by the emblematic imagery: a large eye in the center of a triangle, symbolizing the Holy Trinity, radiates beams of light; the powerful arm of an otherwise unseen angel brandishes a flaming sword; and the figure of Saint Michael holds aloft the scales that weigh the moral frailty of the human heart.

Three of the five remaining narrative episodes of the cycle have greater stylistic unity. In each of these the naturalistic portrayal of the figures is matched by an appropriately atmospheric setting. The Temptation of Saint Anthony (Fig. 44) was clearly inspired by Félicien Rops's woodcut of the same subject. The elongated faces and caps of the men in The Women of Weinsberg (Fig. 45) recall similar features in paintings by Dirk Bouts. This print depicts the amusing story told about the siege of the Bavarian town of Weinsberg in 1140, when the Hohenstaufen enemy Conrad III accepted the surrender of the town on the understanding that only the women would be spared; they were allowed to leave the town with whatever they could carry. The resourceful women met the conditions of the agreement by marching forth with their husbands on their backs. In the more familiar subject Marie Antoinette on Her Way to the Guillotine (Fig. 46) the unfortunate queen sits stiffly upright in a cart surrounded by a jeering mob. This print would seem to presuppose knowledge of the famous sketch, now in the Louvre, in which Jacques Louis David recorded Marie Antoinette's last journey.

The tension between naturalistic modeling and flat decorative elements is again evident in Joseph Interprets the Pharaoh's Dreams (Fig. 47) and Alexander and Diogenes (Fig. 48). Amid the splendor of the king's palace Joseph strikes a lively pose as he interprets the dreams of the seven lean years of corn following the seven abundant years. The idea of illustrating the dreams in the diaphanous roundels visible in the archway may have been inspired by Peter von Cornelius's painting of the same subject in the fresco cycle for the Casa Bartholdy in Rome, transferred to the National Gallery in Berlin around 1886. The story of Alexander's encounter with Diogenes is told by Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius, both of whom describe how Alexander once invited the philosopher to ask any favor. Diogenes, who despised all worldly possessions to the extent of making his home in a tub, requested that Alexander step aside, since the king was shading him from the sun. The rigid figures of Alexander's soldiers form an ornamental screen behind the two men—an amusing contrast with their own relaxed postures. Analogous contrasts in the other prints produce the same effect. For example, against the noble emblem of the all-seeing eye of God the fat figures being carried off by Lucifer appear doubly grotesque; the repose of Pharaoh and his queen intensifies the lively gestures

Figure 46

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Marie Antoinette on Her

Way to the Guillotine , 1894. Etching, 35.0 × 42.3 cm, Schw.

5 VIII. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/7).

Figure 47

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Joseph Interprets the

Pharaoh's Dreams , 1894. Etching, 34.4 × 42.3 cm, Schw.

5 V. Landesmuseum Mainz, Graphische Sammlung.

Figure 48

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Alexander and Diogenes ,

1894. Etching, 34.8 × 42.3 cm, Schw. 5 VI.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

of the jabbering Joseph; and there is no doubt that the hefty women of Weinsberg are fully up to the task of rescuing their skinny husbands, while Marie Antoinette seeks to preserve an air of dignity amid the throng.

The title page of the cycle (Fig. 49) is the most stylized of the nine etchings and sets the tone for the mocking conception that underlies the individual episodes. Within a frame of predominantly geometric design, Clio, the muse of history, lifts a curtain to reveal a human skeleton. In the surmounting arch an enormous face appears, seen from below in strong foreshortening, its large nose sniffing greedily at a blossom that rises from the panel below. The arbitrary choice of the themes is summed up in the closing vignette (Fig. 50). Here a spider in the center of a web contentedly surveys its catch: the flies trapped in the threads.

Two rapidly sketched pencil drawings now in East Berlin, The Rape of the Sabine Women and The Prodigal Son , belong to the themes from which Corinth assembled Tragicomedies , although the episodes themselves were not included in the cycle. They illustrate the kind of first ideas that preceded the etchings. Of the two, The Prodigal Son (Fig. 51) shows especially well that a humorous conception guided Corinth from the beginning, for here his last painting from Königsberg (see Fig. 35) has been turned into a ludicrous persiflage.

Figure 49

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies : Title Page, 1894. Etching, 21.0 × 34.5 cm,