Preferred Citation: Horton, Andrew, and Stuart Y. McDougal, editors Play It Again, Sam: Retakes on Remakes. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1j49n6d3/

| Play It Again, SamRetakes on RemakesEdited by |

Preferred Citation: Horton, Andrew, and Stuart Y. McDougal, editors Play It Again, Sam: Retakes on Remakes. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1j49n6d3/

INTRODUCTION

Andrew Horton and Stuart Y. McDougal

I don't invent: I steal.

Jean-Luc Godard

I.

This collection of original essays is dedicated to exploring the scope and nature of remakes in film and in related media, in Hollywood as well as in the cinemas of other nations. We are concerned with remakes as aesthetic or cinematic texts and as ideological expressions of cultural discourse set in particular times, contexts, and societies. Although there has been considerable recent work in film as an intertextual medium,[1] the remake has received relatively little critical attention to date.[2]

Remakes themselves, however, continue to proliferate. Case in point: the 1994 summer blockbuster Maverick . This film suggests some other genre and cultural boundaries we wish to explore beyond the obvious level of new films made from old. In what sense is the film Maverick a "remake" or "makeover" of the old James Garner television show that began in 1957, the year Mel Gibson, who plays Maverick in the movie, was born? What exactly are the boundaries of a remake? At what point does similarity become simply a question of influence? And what is the difference between a remake and the current television label "spin-off"? Darren Star, creator of Beverly Hills 90210 , agrees that his more recent show, Melrose Place , is a twenty-something spin-off of his earlier high school series, which, in turn, he claims, is a spin-off of the film The Breakfast Club . How do we define the complex relations between these texts?

Our collection of essays responds to these questions in a variety of ways and suggests some of the directions that others may follow, either with a more theoretical interest in defining "remakes" or with a more focused interest in cultural studies and the meanings of repetition in whatever shades of difference such texts may suggest.

II.

We begin with the nature of narrative itself. Edward Branigan has recently reexpressed a definition of narrative this way: "[N]arrative is a perceptual activity that organizes data into a special pattern which represents and explains experience" (3). Narratives, therefore, wherever they are found, both represent and explain or comment on by their structure or content, tone or characterization, experiences from "real" life. A remake is, of course, a particular form of narrative that adheres to Branigan's definition but with an additional dimension. We could paraphrase Branigan to say the remake is a "special pattern which re-represents and explains at a different time and through varying perceptions, previous narratives and experiences." And how do we read such a pattern?

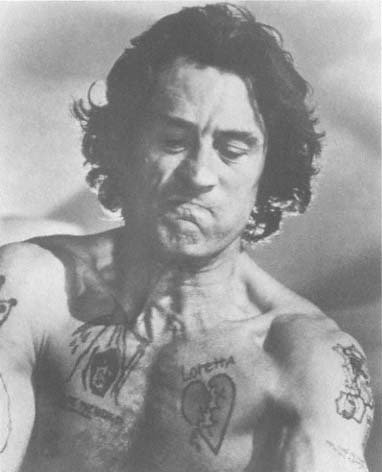

"I don't know whether to look at him or to read him," says Robert Mitchum playing a tough detective in Martin Scorsese's 1991 Cape Fear , as he watches a strip search of the heavily tattooed Robert De Niro, who plays Max Cady, Mitchum's original part in the 1962 version of the film. As we consider cinematic remakes, our dilemma is Mitchum's: do we simply watch or read these texts?

Like Mitchum, of course, we do both. As viewers, we can't help both viewing and reading—that is, teasing out narrative inferences, pleasures, contradictions, and implications of any film. But a film like Cape Fear , advertised as a reworking of an earlier film, forces us to read in a different way, by considering its relationship to the earlier film. Are remakes then merely another instance of a state of affairs as old as recorded literature? The Greek dramatists retold classical myths and Homer borrowed almost everything in his epics while transforming the materials to his own ends. Chaucer and Shakespeare also borrowed liberally from their precursors. As the centuries passed, the relationship between such texts often became much more self-conscious. John Dryden's All for Love (1678) was a reworking of Shakespeare's Anthony and Cleopatra , and audiences were expected to respond to it as such. Ruby Cohn has chronicled the many transformations of Shakespeare on the twentieth-century stage in Modern Shakespeare Offshoots . Such intertextual relationships have proliferated in modern times. In a universe of ever-expanding textuality, the relationships in a text such as James Joyce's Ulysses (1922) between Joyce and Homer (to say nothing of Joyce's reworkings of Dante and Shakespeare) are complex indeed. How do cinematic remakes differ from any modern work that is itself a tissue of other works? In Jorge Borges's story "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote," the title character is quite literally rewriting part of the novel Don Quixote . Borges's story questions notions of textuality, intertextuality, and originality, issues that have become central in modern literary debates. Through her work on Bakhtin, Julia Kristeva introduced the notion of in -

tertextuality, a term to designate the ways in which any text is a skein of other texts. Earlier texts are always present and may be read in the newer text. "The literary word," Bakhtin suggested, "is aware of the presence of another literary word alongside it." Thus texts form what Kristeva calls a "mosaic of citations," each modifying the other, and many modern authors, like Borges or T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land , have foregrounded this issue in their own work. In terms of intertextuality, then, remakes—films that to one degree or another announce to us that they embrace one or more previous movies—are clearly something of a special case, or at least a more intense one.

In Palimpsestes (1982), Gerard Genette expanded on Kristeva's notion of intertextuality through the elaboration of a number of separate categories. These categories form a useful way of situating cinematic remakes. Genette's first category is intertextuality , which he defines more restrictively than Kristeva as the "co-presence of two or more texts" in the form of citation, plagiarism, and allusion. The title of this collection of essays, for example, alludes to a famous line in Casablanca , a line that was remade (and made famous) as the title of a film by Woody Allen. Films emulate literature in this respect, as John Biguenet demonstrates in this volume, and this relationship has a clear bearing on the issue of remakes. Genette's second category, paratextuality , describes the relationships between the text proper and its title, intertitles, prefaces, postfaces, notes, epigraphs, illustrations, and so on. While these relations also apply to film, they are less central to the issue of remakes. Genette's third category is metatextuality , a "critical relationship par excellence " between texts in which one text speaks of another, without necessarily quoting from it directly. The example he cites is Hegel's use of Diderot's Le Neveu de Rameau in his Phenomenology of Mind . Although this relationship does sometimes occur in films, it is quite different from the relationship of texts within a remake. Metatextuality, as Genette notes, is closely related to his fifth category, architextuality . This category, the "most abstract" and the "most implicit," refers to the taxonomic categories of a work as indicated by the titles or, more often, by the subtitles of a text. This too is less applicable to remakes, although like the other categories it provides a context for a discussion of remakes. But the category that occupies Genette most centrally in Palimpsestes, and the one that has the most direct bearing on cinematic remakes, is the fourth type, hypertextuality . Genette defines hypertextuality as the relationship between a given text (the "hypertext") and an anterior text (the hypotext) that it transforms. In the literary example cited above, the hypotexts of James Joyce's Ulysses would include The Odyssey, The Divine Comedy , and Hamlet . This category provides an apt way of discussing cinematic remakes and connects them to other intertextual relationships. In the strictest use of the term remake, a new text (the hypertext) transforms a hypotext. But although Genette's

distinctions provide a useful way of discussing the remake, his terminology does not take us far enough. For our concern here is not only with the remake as a category in Hollywood, where a given film is based on an earlier film, but with an extension of the boundaries of the term remake to include as well works resulting from the contact between diverse cultures and different media. Bill Nichols has recently written of the "blurred boundaries" between fiction and nonfiction today, but his remarks apply to the blurred boundaries between remakes and the texts they draw from or refer to as well. Nichols observes, "Deliberate border violations serve to announce a contestation of forms and purposes. What truths, drawing from what ethics, politics, or ideology, legitimizing what actions, do different forms convey?" (x). We can substitute "narratives" for "forms" and suggest that the remake both pays tribute to a preexisting text and, on another level, calls it into question, as Nichols suggests. And although cinematic remakes—from Anthony Quinn's 1958 remake of his father-in-law Cecil B. DeMille's swashbuckling New Orleans saga, The Buccaneer (1938), in which Quinn was himself a minor star, to Philip Kaufman's 1978 chilling remake of Don Siegel's 1956 Body Snatchers to Kevin Costner's 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves —can stand alone as entertainment and as independent narratives, independence is not what attracted us as editors and/or contributors to this project. This is quite purely a collection dedicated to the pleasure of the pirated text, where remakes constitute a particular territory existing somewhere between unabashed larceny and subtle originality. Remakes, in fact, problematize the very notion of originality. More so than many other kinds of films, the remake and, as we shall see, the makeover—a film that quite substantially alters the original for whatever purpose—invite and at times demand that the viewer participate in both looking at and reading between multiple texts.

Beyond simple remakes of one film to another with the same title and story, we are also interested in extending the definition of remake to include a variety of other intertextual types. What dynamics and dimensions are involved in cross-cultural remakes in which language, cultural traditions, psychology, and even narrative sense may differ greatly. Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954) was influenced by John Ford's westerns, and it in turn became the basis for the Hollywood remake The Magnificent Seven (1960). How do we begin to discuss such a complicated transposition? The titles may or may not be the same and the films may or may not stick to the original narratives, but their relation to those narratives is secure. This, we shall see, especially seems to occur in cross-cultural examples, such as Emir Kusturica's Time of the Gypsies (1989), which is perhaps better called a makeover of Coppola's Godfather done in terms of Yugoslav gypsy culture. And then there are those films that simply allude to or quote from previous films. What does it mean in Honey, I Blew up the Kid to have Japanese tour-

ists look up at a fifty-foot-high kid and shout "Godzilla!" Or when the first word we see posted on the side of the tourists' bus in The Man Who Knew Too Much is "CASABLANCA"? Such questions have a bearing on notions of intertextuality. As films proliferate, so do the relations between them.

In the days when the Hollywood studios held sway, remakes provided a fertile source of material for the theaters' voracious appetites. The bottom line then, as now, was money, and since the studio owned these properties it could cannibalize them at will. John Huston's 1941 film The Maltese Falcon was the third time Warner Brothers had filmed Dashiell Hammett's novel. In recent years, high profits have been garnered by adapting French films for the American screen. The French film Three Men and a Cradle (1985), for instance, grossed slightly over $2 million in the United States, but the Hollywood remake, Three Men and a Baby (1987), has, to date, pulled in over $168 million.

But the issues cannot be explained in terms of finances alone. Sometimes, as with The Maltese Falcon, the remake is a return to an earlier non-cinematic source. Is the filmmaker trying to correct the earlier adaptation, to render a more accurate version of the original text? Here textuality provides but a limited explanation for the remake. In addition, films remake other media—comic books, for example, in Superman, Dick Tracy, and countless other recent films. And films themselves are source texts for other media, among them television and radio. To what extent do these media remake their sources? And finally, what motivates a filmmaker to remake his own work, as Alfred Hitchcock does in The Man Who Knew Too Much? The term remake, then, comprises a broad range of possibilities.

The specific focus of this volume is the phenomenon of movie remakes, especially as practiced in Hollywood. As we approach the end of the century, Hollywood possesses a considerable history it can remake and recycle. One issue seems abundantly simple: there is a film and, for one reason or another, it is remade and re-released at a later date. The differences between the two versions may be significant: in Cape Fear, Scorsese paid complicated attention to why and how Max Cady was framed (the withholding of evidence that the rape victim was a nymphomaniac); or they may be trivial: what does it suggest about Max Cady in the contemporary version that he drinks Evian water from a plastic bottle, while Robert Mitchum drank an endless supply of Bud from cans in the original? The more recent film is defined, in part, by these very differences. After all, at this writing Casablanca and Gone with the Wind are in production or preproduction as updated remakes, and the only thing we can be sure of is that they will differ significantly from their originals. They will tell us as much about our own concerns in the nineties as they will about the films upon which they are based.

The more we think about the issue of remakes, the more we can see how

many significant strands of narrative, cinema, culture, psychology, and textuality come together. Taking the largest possible view—that of human psychology and development—we can, for instance, make the following observation. Experience and development themselves depend upon recognizable patterns of repetition, novelty, and resolution. John Belton has recently written that part of the point of the classical Hollywood film system of narration and style is not only that these films share many narrative and production elements but that, given their similarities, "each strives to be different as well" (American Culture/American Film ). The remake, especially the Hollywood remake, intensifies this process: by announcing by title and/or narrative its indebtedness to a previous film, the remake invites the viewer to enjoy the differences that have been worked, consciously and sometimes unconsciously, between the texts. That is, every moment of every day, we experience what is familiar, what seems "new," and we learn somehow to resolve the difference so we can continue to focus. It was Victor Shklovsky who argued in the early decades of this century that the function of art was to defamiliarize the familiar—to make us experience the commonplace in new ways. One way of achieving this, he noted, was repetition with a difference. In one sense, remakes exemplify this process. They provoke a double pleasure in that they offer what we have known previously, but with novel or at least different interpretations, representations, twists, developments, resolutions.

But there are also, as John Belton makes clear, strong cultural and historical levels to our experience of cinema. To watch Robert Mitchum in the original 1962 Cape Fear and Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese's 1991 version is not just to watch widely differing acting and directorial styles but to experience the historical and cultural changes that have occurred within the twenty-nine years separating these films. The dark elements in the original are definitely threatening, but they appear threatening in black and white at a seemingly less complicated period in American history and culture. One year later, John F. Kennedy was dead and America had entered a true "cape fear" and also a "cape hope" as the sixties began in full force on all fronts—civil rights, Vietnam, the coming of age of the baby boomers, and so on. Scorsese's Cape Fear, however, echoes many of the fears and preoccupations of today, caught in stylishly controlled color. Today, after the Los Angeles riots of 1992; rising crime of all sorts, including serial killings and drug abuse; and the decline of many of our institutions from education to government itself, Americans share a different kind of "cape fear." De Niro's edgy performance and Scorsese's restless camera capture much of this contemporary tension in what is still a "classical" Hollywood narrative, but with certain distinct flourishes.

Our investigation of remakes, therefore, takes us into several distinct areas: the personal (psychological), the sociocultural (political-cultural-

anthropological), and the artistic (cinematic narrative: style-substance-presentation). We will be concerned with all of these "voices" as they speak to us in each film, although the individual essays in this collection may focus upon one or more of them. This collection of essays, then, attempts to map out the field and begin clarifying the nature of these relations.

III.

The tripartite division of our collection suggests our major concerns. Part 1 (framed by the essays of Robert Eberwein and Biguenet) focuses on both the nature of remakes and on some of the ways Hollywood has handled this never-ending source of material. Eberwein's essay provides a useful context for understanding remakes within a "framework emphasizing contextualization" and an "analysis of conditions of spectatorship." Biguenet hones in on a particular aspect of the remake, the cinematic allusion. Taken together, the essays argue for a broader understanding of intertextuality in cinema than has commonly been explored.

The whole collection, in fact, celebrates a variety of critical perspectives regarding the remake. Beyond the general divisions established, we encouraged these invited essayists to employ various strategies for considering repeated and recreated texts.

The first pair of essays considers the films of Alfred Hitchcock, a filmmaker whose work has had an incalculable influence on later filmmakers. Robert Kolker offers a refreshingly original examination of Cape Fear and Basic Instinct as efforts to rework Hitchcock but which, for the most part, fail "to get the figures and the figuration right." Stuart McDougal considers Hitchcock as a director who "continuously re-explored themes and techniques from his earlier work." McDougal's study of The Man Who Knew Too Much sheds light on the workings of a director who always felt there was another chance to revise his past work and "get it right" in terms of new demands and interests.

Turning to a popular work that has been remade many times, Cineaste editor Dan Georgakas takes a decidedly political and ideological approach to the various versions of Robin Hood . He concludes that "the entertainment genre romance of Flynn is closer to historical truth and the myth than Costner's politically correct version so many decades later."

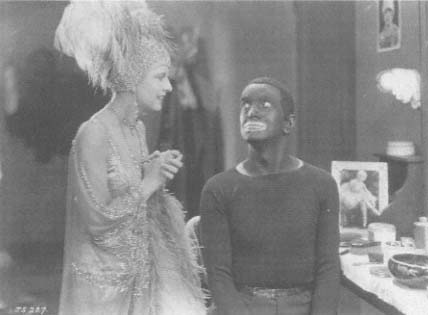

A pair of essays consider the different ways musicals remake earlier sources. Jerry Delamater works with A Star Is Born to map out four specific forms of remakes building on principles posited by Altman, Feuer, Delamater, Collins, and others. Krin Gabbard makes use of a variety of versions of The Jazz Singer to detail the oedipal narrative "that may have attracted each of the stars to the story in the first place."

Another examination of the relationship between the oedipal narrative and cinematic remakes is provided by Harvey R. Greenberg, a practicing New York psychiatrist. Dr. Greenberg takes a psychoanalytic look at Stephen Spielberg's remake of A Guy Named Joe (1943) in his Always (1990), relating it to possible unresolved conflicts between the filmmaker and his father. Beyond his "case study" of Spielberg, however, Greenberg clarifies the oedipal condition of the remake as he views it, concluding that "the remaker, simultaneously worshipful and envious of the maker, enters into an ambiguous, anxiety-ridden struggle with a film he both wishes to honor and eclipse."

Part 2 of our collection pays attention to the transformation of narrative across national and cultural boundaries. Realizing that for Hollywood to redo foreign films or for other countries to reshape Hollywood narrative much more is at play than simply translating from English to French or German or Japanese, each of these essays also explores the cultural and aesthetic dynamics of such makeovers.

Hollywood's raid on foreign narratives is given sharp attention by David Wills in his examination of Jim McBride's version of Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless and by Michael Brashinsky in his study The Last House on the Left , Wes Craven's makeover of Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring . Drawing on his studies of Jacques Derrida, Wills sees film itself as "a web of quotations" and the remake, in this case McBride's Breathless , as only a more blatant form of the whole process of representation. Brashinsky deftly chronicles the transformation of a European high art film into a Hollywood B film.

Andrew Horton and Patricia Aufderheide explore the reverse tradition as Hollywood narratives become the basis for foreign films. Using the Yugoslav makeover of the Coppola Godfather films in Emir Kusturica's Time of the Gypsies , Horton concludes that cinematic makeovers are in part an attempt by foreign filmmakers to feel connected to a world film community and in part a nostalgic impulse at a moment in media history when cinema itself appears in danger of being replaced by other entertainment media. Aufderheide turns to the Far East and details how Hong Kong imitates Hollywood "unabashedly" but, in the process, winds up reflecting much that is prevalent in contemporary Hong Kong culture.

The effect of gender on very different postmodern remakes is the subject of essays by Lucy Fischer and Chris Holmlund. Fisher maps the indebtedness of Pedro Almodovar's High Heels (1991) to Douglas Sirk's Imitation of Life (1959) and analyzes it as a postmodern remake through its "highly parodic" intertextuality, its many citations to mass culture, its intermingling of fact and fiction, its crossing of genres, and its presentation of gender. Holmlund stretches the boundaries of a remake even further through her detailed examination of the ways two experimental filmmakers, Su Fried-

rich and Valie Export, reshape Hollywood products. How, she asks, does celluloid surgery resemble plastic surgery? Using the analogy of the ways in which transsexuals and transvestites disturb gender categories, Holmlund demonstrates how experimental filmmakers transform earlier mainstream movies in their own works. In the process she raises a number of important questions about gender, genre, and the relationships between experimental and commercial films.

The final three essays in the collection explore the connections between Hollywood films and three other media: the comics, radio, and television. Luca Somigli examines the differences between "visual narratives on film and paper," clarifying the narrative possibilities of each form, before turning his attention to the ways in which film has drawn upon comic books for material and techniques. Peter Lehman directs our attention to the differences between radio and film. What happens, Lehman asks, when a film is retold as an episode in a radio series? Lehman underscores the important relations between radio and film in the thirties and forties, when directors, writers, actors, and technicians were working in both media. And Elisabeth Weis shows what happens when a film becomes a series on television, where the narrative can be expanded almost limitlessly. Her essay tells us a great deal about the cultural, technical, and narratological differences between a Hollywood film and a popular television series, at the same time that it extends our definition of the remake.

Part 2 concludes with the deathless appeal of vampire narratives. Lloyd Michaels broadens his dialogue on Nosferatu beyond vampires while noting that cinema itself is a specific signifying system that is haunting, since the referent is not an object or place that can be said to have an actual, even recoverable existence. Ira Konigsberg takes on Francis Ford Coppola's recent Dracula and all previous retellings of this story and suggests a popular cultural view of these films that reflects "changing fears and fascinations toward sex, seduction, and mortality."

IV.

Let us return for a moment to Maverick . At what point should we begin a discussion of this film made "from" the television series? The answer, we suggest, depends on one's particular interests. Maverick as a remake or spinoff is a complicated case, for it was written by William Goldman, who also wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (among many other films) and who worked closely with director George Roy Hill. Hill not only directed Butch Cassidy but The Sting as well, a film many critics have suggested Maverick , the movie, followed rather too closely.

To begin a discussion of Maverick 's borrowings thus takes in a number of

films the audience may or may not recognize: who can watch Mel Gibson, as he nearly falls into the Grand Canyon, without thinking of two women who purposely drove into the canyon in the film Thelma and Louise , clearly "remade" from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid —but twenty years later from a woman's point of view! Allusions, spin-offs, makeovers, and remakes—all of these terms are needed to characterize the complex nature of a work like Maverick .

The spirit that shapes a work like Maverick has been picked up by filmmakers from Hollywood to Hong Kong as they have sought to enrich the possibilities of their medium by transforming novels, comic books, symphonies, television series and, more recently, video games into films and vice versa. If Maverick can return to the big screen, what cinematic-comic-novelistic figure will be next? And in what form?

V.

We celebrated the first century of cinema in 1995. One recognition of this centennial was an imaginative film project entitled Lumière and Company (Lumière et Compagnie ). A French-Spanish-Swedish co-production, this compilation documentary is an omnibus film made up of fifty-two-second pieces shot by thirty-nine directors from around the world using a camera originally used by the Lumière brothers to shoot the first film, fifty-two seconds in length (Variety , 51).

Each director, including Peter Greenway, Costa-Gavras, James Ivory, David Lynch, Liv Ullmann, John Boorman, Spike Lee, Theo Angelopoulos and many more, was asked to shoot whatever he or she pleased but under the same circumstances as the Lumière brothers one hundred years ago: "homemade" film, with natural lighting and nonsync sound.

As the second century of cinema begins, surely this creative collage is tribute to the power of cinema to remake its magic but, as always, with both familiar and new styles, images, and messages.

Works Cited

Bahktin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

———. Rabelais and His World. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1968.

Belton, John. American Culture/American Film. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

Branigan, Edward. Narrative Comprehension and Film. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Cohn, Ruby. Modern Shakespeare Offshoots. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Genette, Gerard. Palimpsestes: La Littérature au second degré. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1984.

Kristeva, Julia. [*]: recherches pour une sémanalyse. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1969.

"Lumiere and Company." Variety (December 4–10, 1995).

Nichols, Bill. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Shklovsky, Victor. "Art as Technique," The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents, 1896–1939 , edited by Richard Taylor and Ian Christie, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

PART ONE—

NEXT OF KIN:

REMAKES AND HOLLYWOOD

One—

Remakes and Cultural Studies

Robert Eberwein

In this essay I propose a suggestion, based on an application of aspects of cultural studies, that is designed to provide a methodologically coherent approach to thinking about various kinds of remakes.[1] I urge a re -contextualization of the original and its remake, achieved by an analysis of conditions of spectatorship.[2]

It is difficult to know where to begin in theorizing remakes. It seems that many of the studies of remakes do not go much beyond a superficial point-by-point, pluses-and-minuses kind of analysis.[3] Often this kind of discussion employs a common strategy: the critic treats the original and its meaning for its contemporary audience as a fixity, against which the remake is measured and evaluated. And, in one sense, the original is a fixed entity.

But in another sense it is not. Viewed from the fuller perspective of cultural analysis over time, the original can—I am arguing that it must—be seen as still in process in regard to the impact it had or may have had for its contemporary audience and, even more, that it has for its current audience. A remake is a kind of reading or rereading of the original. To follow this reading or rereading, we have to interrogate not only our own conditions of reception but also to return to the original and reopen the question of its reception. Please understand that I am not arguing that a return to the original will necessarily yield a "new" meaning in the film that has hitherto been missed by shortsighted critics. Rather, I am arguing that a fresh return to the period may help us understand more about the conditions of reception at the time and, hence, offer us a fuller range of information for comparing the original and its audience with the remake and its audience. To demonstrate the point, I will use as my particular focus the original and remake of Invasion of the Body Snathchers (Don Siegel, 1956; Phil Kaufman, 1978). I have chosen this film largely because it has been remade

again by Abel Ferrara. I am sure that the most recent remake will evoke stimulating commentaries on the relation between itself and its predecessors, but I doubt that anyone writing about the new film will be able to position it fully in terms of its contemporary reception. And that is because a contemporary audience is fixed by its spatiotemporal restrictions. We are inside a particular historical and cultural moment that may in fact account for certain aspects of the film Ferrara made recently. It will remain for later critics to look back and speculate on the conditions of reception for the film in a way that I am convinced we really can't since we are inside the historical and cultural moment.

In a recent essay in Framework on Caribbean cinema, Stuart Hall makes some telling points that can serve to introduce the argument I want to make about our investigations of remakes as these both posit and depend on certain assumptions about audience reception. Specifically he addresses the concept of cultural identity as a construct emerging from the Caribbean cinema. But the applicability of his comments to assumptions about a shared cultural identity is pertinent to consideration of any cinema assumed to "reflect" the culture in which it is produced. According to Hall: "The practices of representation always implicate the positions from which we speak or write—the positions of enunciation . What recent theories of enunciation suggest is that, though we speak, so to say 'in our own name,' of ourselves and from our own experience, nevertheless who speaks, and the subject who is spoken of, are never exactly in the same place. Identity is not as transparent or unproblematic as we think. Perhaps . . . we should think . . . of identity as a 'production,' which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation" (68). Cultural identity "is not a fixed essence at all, lying unchanged outside history and culture" (71).

I am appropriating Hall's view of cultural identity and considering it in relation to the way we posit culturally inflected unity in originals and remakes. As you can tell, one of my basic concerns here is whether we can talk about remakes as if they and their audience were "lying unchanged, outside history and culture"—as if, in other words, interpretation can assume a fixed timeless cultural identity.

Some comments on the original and remakes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers will illustrate the point. Nora Sayre, for example, writes: "(In the Fifties, many believed that Communist governments turned their citizens into robots.) So the political forebodings of the period spilled over into science fiction, where subservience to alien powers and the loss of free will were so often depicted, and the terror of being turned into 'something evil' became a ruling passion. The amusing 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers did not perpetuate the social overtones—instead it concentrated on conformity and surrendering the capacity to feel, and few of the scenes

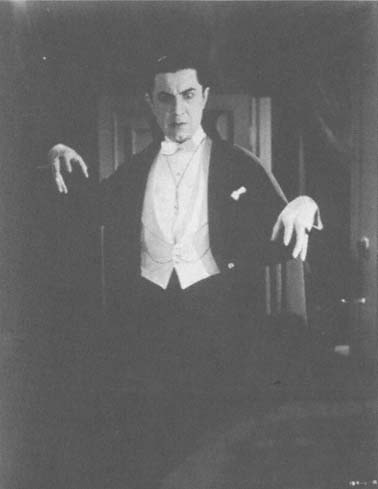

Figure 1.

Beware of huge pods found at night! A pod conceals its startling secret

in Don Siegel's original Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

had the impact of Kevin McCarthy's climax in the original, when he stood on a highway, screaming at passing trucks and cars, 'You fools, you're in danger . . .! They're after us! You're next! You're next!'" (184).

Richard Schickel's comment on the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) is equally relevant: "In its day, Invasion made a moving and exciting film. Among other things, it was a metaphorical assault on the times when, under the impress of McCarthyism and two barbecues in every backyard, the entire Lonely Crowd seemed to be turning into pod people. (See figure 1.) The remakers have missed that point, failing to update the metaphor so that it effectively attacks the noisier, more self-absorbed conformity of the '70s" (82).

Both Sayre and Schickel make what seem for a variety of reasons to be unwarrantable assumptions about audiences and reception that then become the basis of interpretive judgments. Each treats the original as having completed the acts of reflecting its culture and conveying its meanings once and for all. But this is a problematic position to maintain, particularly as a ground of critical judgment, because the position elides two questions: what

do we know of the specific audience for the first film? and what do we know of its multiple audiences over time? The position supposes that within a homogeneous audience locked in its own time and space—the time and space of the film's release—there had been cultural agreement and unanimity about interpretive questions when the film appeared.

Any film that survives will have audiences over time. A film that is remade encounters new audiences, individuals who might not have encountered the original if someone hadn't decided to remake the older film. The question of why later filmmakers appropriate earlier films is an issue deserving at least a brief digression at this point. Various suggestions have been made to account for the existence of remakes. These explanations range from the purely economic to the highly personal. For example, it is a critical commonplace that Hollywood studios have recycled films as a way of saving money by using properties to which they already hold the rights—hence remakes of older films. On one level, this explanation could be applied universally to account for all remakes, since no film is made in order to lose money.

But there are at least a couple of reasons why this explanation is too simple or at least incomplete. First, we have evidence that some directors with sufficient clout and economic support may remake a film for personal reasons. For example, Frank Capra explains why he remade Lady for a Day: "I wanted to experiment with retelling Damon Runyon's fairy tale with rock-hard non-hero-gangsters"—hence A Pocketful of Miracles (Silverman, 26). In addition, Franco Zeffirelli claims he remade The Champ (King Vidor, 1931; 1979) because he identified strongly with the family problems figured in the older film. He had seen it as a child and been moved. Having seen it more recently, he says: "'[T]he whole trauma came back, the whole syndrome of anguish.' He remembered that Richard Shepherd, an MGM executive, had invited him to make a movie in this country. 'I called him and said I wanted to do a remake to The Champ '" (Chase, 28).

Second, Harvey Greenberg has suggested even more complex reasons possible for wishing to remake a film, various forms of "Oedipal inflections" evident in different kinds of relationships between older and newer filmmakers: first, "unwavering idealization" in the faithful remake; second, "the remaker, analogous to a creative resolution of childhood and adolescent Oedipal conflict, eschews destructive competition with the maker, taking the original as a point of useful, unconflicted departure"; third, "the original, as signet of paternal potency and maternal unavailability/refusal, incites the remaker's unalloyed negativity"; and, fourth, "the remaker, simultaneously worshipful and envious of the maker, enters into an ambiguous, anxiety-ridden struggle with a film he both wishes to honor and eclipse." The latter is the "contested homage" Greenberg sees at work in Steven Spielberg's Always (115ff.).

In addition, we can think of one remake that is the product of neither economics nor psychoanalytic conflict. As Lea Jacobs has explained, Universal had hoped to re-release Back Street (John Stahl, 1932) in 1938, but, because it ran afoul of the Production Code Administration, headed by Joe Breen, the studio ended up having to remake the film (Robert Stevenson, 1941): "[T]he film had been . . . criticised by the reform forces at the time of its original release; in particular, it had been attacked by Catholics connected with the Legion of Decency. The story . . . was said to generate sympathy for adulterers and to undermine the normative ideal of marriage as monogamous. When Breen argued against a re-release of the 1932 version, Universal agreed to do a remake" (107).

It is useful to consider Phil Kaufman's stated reasons for wanting to remake Invasion of the Body Snatchers in light of this information:

In 1956, the science-fiction consciousness of the public was limited, and now it's greatly expanded, so you could deal with certain things in different ways. . . . There were a lot of articles coming to my attention about how we were being bombarded from outer space, saying that diseases are coming from outer space. . . . There were political overtones to the original film, and there are two sides on this. What was the original saying? Was it anti-Communist? Was it anti-anti-Communist? I don't know the answer to that. It's interesting to examine the original film both ways, because both theories seem to make sense. Obviously those political overtones don't apply to our film. . . . I also feel that paranoia or fear is a very important thing. I don't think this film would have been worthy of a remake during the period of the Vietnam war, because at that time there was a high consciousness about where we were. The fears hanging over everyone's heads—particularly young people's—gave them a sense of mortality. . . . I think that in the last couple of years, we've been losing that sense of mortality. Fear is very valuable in a time of complacency (Farber, 27).

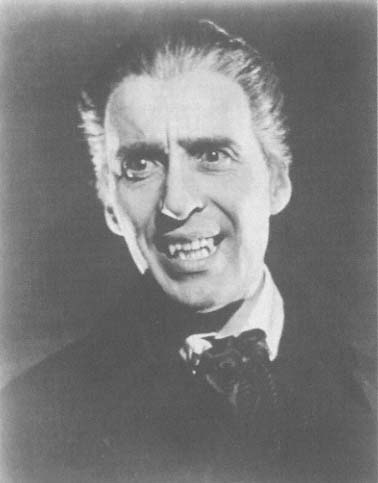

In addition, Kaufman says, "It seems to me . . . that this is a perfect time to restate the message of Body Snatchers . . . . We were all asleep in a lot of ways in the Fifties, living conforming, other-directed types of lives. Maybe we woke up a little in the Sixties, but now we've gone back to sleep again. We've taken some of the things that were expressed about the original film—that modern life is turning people into unfeeling, conforming pods who resist getting involved with each other on any level—and we're putting them directly into the script" (Freund, 23). (See figure 2.)

Interestingly, in none of Kaufman's comments, or in the reviews cited above, do we get anything that addresses the historical-cultural moment when the original film actually appeared. It was released without any acknowledgment in the New York Times (advertising or reviews) at the end of February 1956. There are very few reviews that Albert LaValley has been able to assemble in his invaluable edition of the script and commentary. In

Figure 2.

A pod person slumbers in Phil Kaufman's Invasion of the

Body Snatchers , the 1978 remake.

subsequent years, as far as I have been able to determine, no one has fully come to terms with the moment of the film's release in regard to the audience and the country receiving it. But, as George Lipsitz, one of the major American proponents of cultural studies, reminds us in a discussion of other works, any film "responds to tensions exposed by the social moment of its creation, but each also enters a dialogue already in progress, repositioning the audience in regard to dominant myths" (169). Equally pertinent is Michael Ryan's observation: "The 'meaning' of popular film, its political and ideological significance, does not reside in the screen-to-subject phenomenology of viewing alone. That dimension is merely one moment in a circuit, one effect of larger chains of determination. Film representations are one subset of wider systems of social representation (images, narratives, beliefs, etc.) that determine how people live and that are closely bound up with the systems of social valorization or differentiation along class, race and sex lines" (480).

I want to talk about the dialogue already in progress when the original emerged, with the hope of putting us in closer contact with the audience that experienced the film. First, I want to clarify somewhat more fully

the question of the communist menace. By the time the film appeared, Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose attack on communists is consistently used to interpret the film's meaning (anti-communist? anti-anti-communist?), had already started to lose power. Joseph Welch's stinging condemnation of him had occurred in 1954. In 1955, the year that Invasion of the Body Snatchers was being made, while there continued to be investigations of communists, some of them proceeding from McCarthy, news accounts reveal a partial unraveling of the charges and sentences that had resulted from the activities of McCarthy and Roy Cohn. As a matter of fact, in the very months that the film was being made (March 23 to April 18, 1955), the convictions of two men were reversed on the grounds that one Harvey M. Matusow had admitted to lying when he said they were communists. Matusow claimed he had been coached by Roy Cohn. The latter was exonerated of that charge. Still, in the context of a year when other convicted communists were being released (some to be retried) and when, according to Facts on File , "the Eisenhower administration, reacting to criticism of its employee security program, revised its procedure to insure that accused Govt. workers received 'fair & impartial treatment' at the hands of Govt.," it is clear that the overwhelming period of paranoia and the domination of McCarthy and Cohn had started to ease significantly (Facts on File , March 3–9, 1955: 75. Also February 24–March 2; March 10–16; April 21–27). Thus, we need to be careful about the extent to which we: 1) attribute a particular mind-set to a contemporary audience confronting a film supposedly illustrating the communist menace (whether from the left or the right); 2) use this mind-set to fix the film's meaning; and 3) criticize a remake for failing to reproduce it.

There are two historically relevant matters that can be advanced as having more than a casual relevance to the contemporary audience. The first involves what for want of a better term I will call the discourse of medicine. Peter Biskind talks about the treatment of doctors generally in right-wing films but hasn't fully explored the following with reference to Invasion (60–61). In 1954, Dr. Jonas Salk had discovered a vaccine that would apparently stop polio. The vaccine was tested in 1955 and put to use that year. On February 6, 1956 (a few weeks before the release of Invasion ), Salk and his predecessors who worked to develop the vaccine were honored by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The citation is worth quoting, particularly in light of cold-war rhetoric: "A community needed a bell tower to warn its people against attack. Everyone helped to build it, and the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. When it was finished, the feeling of gratitude of each man for his neighbor, for what each had contributed, was showered upon but one—and he was among the last to contribute. But all knew that the end could not have come without the beginning and without all that had transpired in between" ("Salk Award," 74). Jonas

Salk was one of two doctors whose status approached that of the venerated. The other was Paul Dudley White, President's Dwight Eisenhower's personal physician and the person honored not only for helping Eisenhower pull through his heart attack but also for having started to change the health habits of Americans. Dr. White's status as personal physician and as national spokesperson for health was of particular significance at the moment the film was being released, because the nation was poised to hear whether Eisenhower would run again for election. There had already been considerable campaign activity among Democratic candidates, particularly between Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson, who were seeking the nomination. It was assumed that Eisenhower's decision, when it came, would be predicated on Dr. White's estimate of his health and fitness to run. The week before the film opened, White and the medical advisers had said he was "able"; the title of an article in Life for February 27, 1956, on the matter was: "Doctors Say He's Able—Is He Willing?" (38–39).

Thus at the point of the film's appearance, one can see a valorization almost approaching the hagiographic of two doctors: Salk, who had saved the children from attack; and White, who had saved the president and was helping to change physical behavior in the nation's citizens. The latter's work had an inescapably political dimension, given his association with administrative and hence political stability.

In addition, there was evidently strong support for the medical profession in general. Time reported on a survey done by the American Medical Association: "To no one's surprise, the A.M.A. concluded that doctors stand comfortingly high in public esteem. Only 82% of the 3,000 people polled have a regular family physician, but of those who do, 96% think well of him" ("Patients Diagnose Doctors," 46). That same week, the magazine reported on a training program developed at the Menninger Psychiatric Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, in which the Menninger brothers counseled various business leaders and managers in ways of using "psychology and psychiatry . . . to help them with their problems" in the workplace ("Psychiatry for Industry," 45).

In such a historical and cultural context, it is worthwhile to consider the possible impact of Invasion of the Body Snatchers , specifically the impotency of those associated with the medical discourse in the film. The psychiatrist Danny Kaufman (Larry Gates), the family doctor Ed Pursey (Everett Glass) who delivered Becky, and the nurse Sally (Jean Willes) are all taken over by the pods. It is Sally who is conducting the transformation of her own baby when Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) spies on her home. Only in the narrative frame added after previews of the film is Miles restored to viability within the medical community; this occurs when Dr. Bassett (Richard Deacon) and Dr. Hill (Whit Bissell), another psychiatrist, begin to believe his story after hearing of the truck accident and the cargo

of pods. My point is that such a unilateral and comprehensive presentation of medicine as succumbing to an alien force (involving nursing, general practice, and psychiatry) can be imagined to have had some resonance with the audience, but in a way that doesn't involve conformity or conspiracy.

An even more significant historical-cultural consideration I want to point out has to do with the events of February 1956 as they pertained to civil rights. Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, and a subsequent ruling in 1955 in which the phrase "with all due deliberate speed" was used in reference to public education, were very much on the collective minds of the citizens in 1956. Early in February, Miss Autherine Lucy had entered the University of Alabama in Montgomery under court order. After two calm nights (she was not permitted to stay in the dormitory), various demonstrations erupted, including cross burnings. She was dismissed from the institution by the trustees in order to insure harmony. This action occasioned different kinds of agitated reactions. Some students protested the trustees' action. Democrats campaigning for the presidential nomination were asked what they would do to enforce the court decree if they were president. At the same time, on February 21, "115 persons were indicted by a county grand jury . . . in Montgomery, Ala. . . . on charges of instigating a Negro mass boycott of City Line buses. . . . The boycott began Dec. 5, 1955, after Mrs. Rosa Parks, a Negro, was fined $14 for refusing to give up her seat" (Facts on File , February 15–21: 61). The following week, a Gallup poll reported that "Southern whites disapproved the Supreme Court's school desegregation ruling by a 80%–16% majority" (Facts on File , February 22–28, 1956: 68). In the first week of the film's release, Life carried an essay by Nobel Prize winner William Faulkner, "A Letter to the North," in which he defends the position of going slowly in the integration process. Although he says segregation is an "evil," "I must go on record as opposing the forces outside the South which would use legal or police compulsion to eradicate that evil overnight" (51). He concludes by asserting "that 1) Nobody is going to force integration on [the Southerner] from the outside; 2) [t]hat he himself faces an obsolescence in his own land which only he can cure: a moral condition which not only must be cured but a physical condition which has got to be cured if he, the white Southerner, is to have any peace, is not to be faced with another legal process or maneuver, every year, year after year, for the rest of his life" (52).

The use of language couched in reference to cures and illness is significant. A month earlier, in an article entitled "South Rises Again in Campaign to Delay Integration," Life had run a picture of a Pontiac automobile carrying a Confederate flag and a banner taped to the side: "Save Our Children from the Black Plague" (22–23). And the previous year, according to William J. Harvie, in testimony before the Supreme Court, a Virginia attorney working for delay in integration said: "Negroes constitute 22 percent of

the population of Virginia . . . but 78 percent of all cases of syphilis and 83 percent of all cases of gonorrhea occur among the Negroes. . . . Of course the incidence of disease and illegitimacy is just a drop in the bucket compared to the promiscuity[;] . . . the white parents at this time will not appropriate the money to put their children among other children with that sort of background" (63).

In addition, according to the New York Times , during that month there were renewed instances of states such as Georgia and Mississippi introducing "nullifying" bills and "interposition" bills. The former type of bill simply denies the application of federal rulings to an individual state; the latter involves states enacting laws to defend their own jurisdictions by countering federal legislation ("Miss Lucy v. Alabama," 1; "Georgia Adopts 'Nullifying' Bill," 16). In addition, there was movement to "abolish public schools, create gerrymandered school districts and set up special entrance requirements" ("School Integration Report," 7).

All this is offered not to say that Invasion of the Body Snatchers contains a previously undiscovered allegory about racism but, rather, to suggest that we ought to remember that the film entered a dialogue, to use Lipsitz's phrase, of considerable tension. In this regard, it is interesting to consider several scenes from the original in which the action and language seem pertinent.

In the first of these scenes, Miles, suspecting that a gas station attendant who had earlier serviced his car may be one of the invaders, stops his car and discovers two pods hidden in the trunk. He pulls them out and sets them on fire. The camera lingers on the flames as they envelop the pods. Burning of alien forces at night in a way that emphasizes the flames against the darkness might well have reminded contemporary audiences of the cross burnings that had recently occurred.

Second, as Miles and Becky (Dana Wynter) watch unobserved from his office, townspeople gather in the square while the pods are being distributed to trucks that will carry them to various communities beyond Santa Mira. As he sees the full implication of the spread of the pods and the infiltration of the aliens into neighboring communities, Miles describes the situation to Becky in terms of a "malignant disease spreading throughout the country."

Third, during the frenzied sequence on the highway, Miles tries to stop motorists and warn them. Specifically (in a shot in which he virtually addresses the camera) he warns: "Those people are coming after us. They're not human. You fools, you're in danger. They're after you, they're after all of us. Your wives. Your children." It is hard not to see a connection between the film's depiction of a threatening, destabilizing force from within the society, characterized in terms of disease, taking over lives, and threatening wives and children, and the current discourse going on in the country in

which individual states tried to avoid what was perceived as a similarly destabilizing force, one characterized as a disease.

I make no claim that this information about the context of reception for the 1956 Invasion will help us understand the 1978 film any better. But it may help to define the differences between the two films somewhat more finely and in a way that goes beyond what I submit has not been sufficiently complete. What's at issue is a cultural version of Michel Foucault's episteme or what in another context Ann Kaplan has called the "semiotic field" of a work (41). As scholars and critics making comparative evaluations, we enrich our work to the extent that our positioning of the original in relation to the remake comes to terms with the forces and dialogues that shaped the works as well as those into which it entered. In fact, with this kind of comparative approach, we may find ourselves better positioned to comment on the relation between original and remake.[4]

The remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers was released December 22, 197.. Within the month, events occurred that could not have been anticipated in any way by the filmmakers but that provide a grim background for its reception. First was the discovery of the mass suicides led by Jim Jones at the People's Temple of Jonestown, Guyana. Pictures of the more than nine hundred suicides appeared in newspapers and, in color, in magazines like Time and Newsweek . Reports of the suicide made it clear that some of the victims were forced to participate. According to Facts on File, "As for the dissenters, some appeared to have been browbeaten into drinking the poison and others appeared to have been murdered by zealous cult members. Guyanese sources told the New York Times Dec. 11 that at least 70 of the bodies found at Jonestown bore fresh injection marks on their upper arms. The marks presumably showed that the poison had been injected into these victims by others, since it was very difficult for a person to inject himself in that part of the body" (Facts on File, December 15, 1978: 955).

Such information and pictures must have resonated in those members of the audience aware of it who were watching the weirdly charismatic psychiatrist Dr. David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy) inject Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams) with a "light sedative" that would cause them to sleep and, subsequently, to die as they were taken over by the aliens. The international reaction to the horribly disturbing mass suicide had its counterpart in the national response to the news that, within a few weeks, two teenagers committed suicide in a suburb in New Jersey; they were "the third and fourth Ridgewood, N.J., youngsters to die by their own hands in the past 18 months." One explanation offered was that attention paid to the Jonestown disaster may have triggered the recent suicides, but others, according to Time, "[saw] a deeper malaise," including school pressures and family difficulties ("Trouble in Affluent Suburb," 60).

Ironically, the December 4 story about Jonestown included a quotation from San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, who, according to Time, "received important help from Jones in his close 1975 election [and had] appointed him to the city's housing authority in 1976. (Said the mayor about last week's horror: 'I proceeded to vomit and cry.')" ("Messiah from the Midwest," 27). Within the week, Moscone was dead, having been shot along with Harvey Milk by Dan White. In a creepy coincidence, the film is set in San Francisco and includes a scene in which Matthew seeks Kibner's help in reaching the mayor by phone. As far as I have been able to determine, the association of the suicides and murders, of Jones, Moscone, and Milk, and San Francisco, and the turbulent atmosphere of death in the month of December seem not to have entered into contemporary reviews of the film. Indeed, the opposite seems to be the case if Pauline Kael's laudatory review is examined. She notes: "The story is set in San Francisco, which is the ideally right setting because of the city's traditional hospitality to artists and eccentrics. . . . San Franciscans often look shell-shocked. . . . The hipidyllic city, with its ginger-bread houses and its jagged geometric profile of hills covered with little triangles and rectangles, is such a pretty plaything that it's the central character" (48).

Our own period has recently seen a revival of interest in conspiracy theories in regard to the assassination of John F. Kennedy because of the interest generated in conjunction with Oliver Stone's film (JFK, 1991). The audience for Invasion of the Body Snatchers during the last week of 1978 and the beginning of 1979 was learning that the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations "concluded Dec. 30 that President John F. Kennedy 'was probably assassinated as a result of conspiracy' in 1963. . . . The committee also said that on the basis of circumstantial evidence 'there is a likelihood' that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was slain as a result of conspiracy. . . . The findings came at the end of the committee's $5.8 million, two-year inquiry into the assassinations of the two leaders. . . . The committee flatly stated that none of the U.S. intelligence agencies—the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Secret Service—were involved in the Kennedy murder. The three agencies cleared were, however, criticized for their failings during the assassination and in the investigations after. The Justice Department was also attacked for its direction of the FBI probe" (Facts on File, December 31, 1978: 1002). Such information could well have hit a collective nerve in the audiences watching the futile attempts of Matthew Bennell and his friends. It's not that Kaufman gives any evidence of wanting to build in considerations of assassination conspiracy theories; rather, the film, with its frightening depiction of a conspiracy involving the police, the municipal government, and the secret service appears at a time when a major committee is raising the possibility of conspiracies and denying that the highest government agencies

are involved. The threat of conspiracy in the remake seems, from our perspective, to have even more potential relevance to its audience in 1978 than the already fading threat of a communist conspiracy had for the audience of 1956.

Another dimension of the semiotic field worth noting concerns the pods themselves. Certainly one of the most disturbing scenes in the films occurs when we watch the creatures reproducing while Matthew sleeps. Kaufman examines the creatures with uncompromising (and unnerving) scrutiny as they emerge struggling from their pods, swathed in weblike mucus and uttering little cries. After being awakened by Nancy Bellicec (Veronica Cartwright), Miles uses a spade to attack the pods and, in one particularly gruesome shot, is seen splitting open the head of the one that resembles him.

In this scene the film enters a dialogue about abortion that was raging then and is even more violent now. Nothing that Kaufman has said even hints at any self-conscious imposing of a thesis on abortion into the film. Just as I linked the earlier film to civil rights, I here try to contextualize the images in terms of the audience's historical and cultural position in relation to the controversy. What is clear to me is that such images entered a semiotic field in which the legal and medical status of the fetus had already been hotly debated. In 1978, there had been several cases nationally in which "consent" agreements had included provisos that women seeking abortions had to view photographs of fetuses or be given descriptions of them by doctors. According to Facts on File, the law in Louisiana "required the doctor to describe 'in detail' the characteristics of the fetus, including 'mobility, tactile sensitivity, including pain, perception or response, brain and heart function, the presence of internal organs and the presence of external members'" (September 29, 1978: 743).

There was also legal consideration of the fetus's ability to withstand a saline abortion, most immediately in connection with the trial of Dr. William Waddill, a California physician accused of having strangled a twenty-eight-to thirty-one-week-old infant after it survived an abortion (Lindsay, 18). Audiences watching the film and Bennell's "murder" of his double might well have been affected by the abortion controversy, particularly since they had watched the character kill something that, recently emerged from its pod, was more "alive" than "dead."[5]

I am grateful to Lucy Fischer for suggesting that another dialogue in which the film can be seen engaging concerns in vitro fertilization, a medical phenomenon that had occurred for the first time earlier in 1978. In July of that year in England, Drs. Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards succeeded in effecting the conception of a child for Lesley and Gilbert John Brown ("British Awaiting Birth," 1). That same month, a much less happy case of in vitro fertilization was reported. The John Del Zio family was suing the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, charging that Dr. Raymond L.

Vande Wiele "deliberately destroyed" the embryo produced in 1973 at the hospital ("Childless Couple Is Suing Doctor," 26). One concern raised during the trial by lawyers defending Columbia University was that the experiment's outcome was uncertain: "[The Del Zio's] physicians, the lawyer said, had no way of knowing whether their efforts would produce a 'monster birth' or a normal child" ("2 Charge 'Jealous' Doctor," 9). Shortly after this scene, Kaufman's film does in fact reveal a monster effected by this process. As a result of a partial aborting of the pod birth process, a dog acquires the head of the Union Square singer seen earlier in the film. Again, an audience in 1978 could reasonably be expected to have a certain amount of exposure to this medical information about a different kind of birth process, one in which there is a fear of something going wrong.

I want to conclude by quoting George Lipsitz again. He speaks of "sedimented historical currents" and of "sedimented networks and associations" that are more than merely intertextual references. His comment seems pertinent to our consideration of remakes and their originals: "The presence of sedimented historical currents within popular culture illumines the paradoxical relationship between history and commercialized leisure. Time, history, and memory become qualitatively different concepts in a world where electronic mass communication is possible. Instead of relating to the past through a shared sense of place or ancestry, consumers of electronic mass media can experience a common heritage with people they have never seen; they can acquire memories of a past to which they have no geographic or biological connection. The capacity of electronic mass communication to transcend time and space creates instability by disconnecting people from past traditions, but it also liberates people by making the past less determinate of experiences in the present" (5). This is true, but I would add that we have to work at this by reconstructing as much as possible the historical contexts, just as someone years hence will try to recover ours.

Kinds of Remakes:

A Preliminary Taxonomy

1. a) A silent film remade as a sound film: Ben Hur (Fred Niblo, 1926, and William Wyler, 1959); b) a silent film remade by the same director as a sound film: Ernst Lubitsch's Kiss Me Again (1925) and That Uncertain Feeling (1941) or Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956); c) a major director's silent film remade as a sound film by a different major director: F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) and Werner Herzog's Nosferatu, the Vampire (1979).

2. a) A sound film remade by the same director in the same country: Frank Capra's Lady for a Day (1936) and A Pocketful of Miracles (1961); b) a sound film remade by the same director in a different country

in which the same language is spoken: Alfred Hitchcock's The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, England, and 1954, United States); c) a sound film remade by the same director in a different country with a different language: Roger Vadim's And God Created Woman . . . (1957, France, and 1987, United States).

3. A film made by a director consciously drawing on elements and movies of another director: Howard Hawks's and Brian DePalma's Scarface (1932 and 1983); Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (1959) (and Rear Window [1955] and Psycho [1960]), and DePalma's Obsession (1976), Body Double (1984), and Raising Cain (1992).

4. a) A film made in the United States remade as a foreign film: Diary of a Chambermaid by Jean Renoir (1946, France) and Luis Buñuel (1964, France); b) a film made in a foreign country remade in another foreign country: Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961) and A Fistful of Dollars (Sergio Leone, 1964); c) a foreign film remade in another foreign country and remade a second time in the United States: La Femme Nikita (Luc Besson, 1990, France), Black Cat (1992, Hong Kong) (thanks to Scott Higgins), and Point of No Return (John Badham, 1993); d) a foreign film remade in the United States: La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931) and Scarlet Street (Fritz Lang, 1945) and Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960, and Jim McBride, 1983).

5. a) Films with multiple remakes spanning the silent and sound eras: Sadie Thompson (Raoul Walsh, 1928), Rain (Lewis Milestone, 1932) and Miss Sadie Thompson (Curtis Bernhardt, 1953); b) films remade within the silent and sound eras as well as for television: Madame X (Lionel Barrymore, 1929 [the third silent remake of the silent film]; Sam Wood, 1937; David Lowell-Rich, 1966 [the Lana Turner version]; and, for television, Robert Ellis Miller, 1981 [with Tuesday Weld]).

6. a) A film remade as television film: Sweet Bird of Youth (Richard Brooks, 1962, and Nicholas Roeg, 1989); b) a film remade as a television miniseries: East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955, and Harvey Hart, 1981); c) a television series remade as a film: Maverick (Richard Donner, 1994) and The Flintstones (Brian Levant, 1994).

7. a) A remake that changes the cultural setting of a film: The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946, United States, and Michael Winner, 1978, Great Britain); b) a remake that updates the temporal setting of a film: Murder, My Sweet (Edward Dmytryk, 1944) and Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975); A Star Is Born (William Wellman, 1937, George Cukor, 1954, and Frank Pierson, 1976); Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1948) and Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984); c) a remake that changes the genre and cultural setting of the film: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (Henry Hathaway, 1935) re-

made as a western, Geronimo (Paul H. Sloane, 1939); the western High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1954) remade as the science fiction film Outland (Peter Hyams, 1981).

8. a) A remake that switches the gender of the main characters: The Front Page (Lewis Milestone, 1931); His Gal Friday (Howard Hawks, 1941); b) a remake that reworks more explicitly the sexual relations in a film: William Wyler's These Three (1936) and The Children's Hour (1961); The Blue Lagoon (Frank Launder, 1949, and Randal Kleiser, 1980).

9. A remake that changes the race of the main characters: Anna Lucasta (Irving Rapper, 1949, with Paulette Goddard; Arnold Laven, 1958, with Eartha Kitt).

10. A remake in which the same star plays the same part: Ingrid Bergman in the Swedish and American versions of Intermezzo (Gustav Molander, 1936, and Gregory Ratoff, 1939); Bing Crosby in Holiday Inn (Mark Sandrich, 1942) and Holiday Inn (Michael Curtiz, 1954).

11. A remake of a sequel to a film that is itself the subject of multiple remakes: The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1975) and The Bride (Frank Roddam, 1985).

12. Comic and parodic remakes: Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931) and Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1954); Strangers on a Train (Alfred Hitchcock, 1951) and Throw Mamma from the Train (Danny DeVito, 1987).

13. Pornographic remakes: Ghostbusters (Ivan Reitman, 1984) and Ghostlusters (1991); Truth or Dare (Alex Kashishian, 1991) and Truth or Bare (1992) (thanks to Peter Lehman).

14. A remake that changes the color and/or aspect ratio of the original: The Thing (Christian Nyby, 1951, black-and-white; John Carpenter, 1982, color and Panavision); Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956, black-and-white and Superscope; Phil Kaufman, 1978, color and 1.85 to 1 aspect ratio).

15. An apparent remake whose status as a remake is denied by the director; Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1966) and Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974).

This taxonomy doesn't cross-reference films. Clearly, some could be put in more than one category. The Big Sleep, for example, updates the temporal and cultural settings. In addition, the list doesn't address any number of relevant production and economic aspects: the role of the star as an element in developing the remake (Barbra Streisand and the 1976 A Star Is Born ); variations in advertising, marketing, and distribution practices from period to period, genre to genre, country to country; historical data about the studios' decisions on remaking; comparative financial data on the origi-

nal and remake; issues of acquiring rights; distinguishing among the major and minor studios (e.g., an MGM remake of an MGM picture? a United Artists remake of an Allied Artists picture?); and epochal analyses of remaking practices—for example, comparative data regarding the number of remakes in the period of "classical Hollywood cinema" as opposed to during the sixties and later periods.[6]

Even more problematic, the taxonomy itself doesn't address the issue of adaptation: are there any films in the various categories that can claim a common noncinematic source? If so, is it correct to call a film a remake or a new adaptation (e.g., Madame Bovary, Vincente Minnelli, 1949; Claude Chabrol, 1991)? Are there stages left out between the original and remake, as occurs for example when a play intervenes between the original and the remake (e.g., The Wiz )?

Works Cited

Biskind, Peter. Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

"British Awaiting Birth of Baby Conceived in Laboratory Process." New York Times, 12 July 1978, sec. 1, pp. 1, 13

Chase, Donald. "The Champ: Round Two." American Film 3, no. 9 (July–August 1978): 28.

"Childless Couple Is Suing Doctor." New York Times, 16 July 1978, sec. 1, p. 26.

"Doctors Say He's Able—Is He Willing?" Life, 27 February 1956, 38–39.

Doherty, Thomas. "The Fly." Film Quarterly 40, no. 3 (spring 1987): 38–41; "The Blob." Cine-Fantastique 19, no. 1–2 (January 1989): 98–99.

Druxman, Michael B. Make It Again, Sam: A Survey of Movie Remakes. Cranbury, N.J.: A. S. Barnes, 1975.

Facts on File Yearbook 1955. Vol. 15. New York: Facts on File, 1956.

Facts on File Yearbook 1956. Vol. 16. New York: Facts on File, 1957.

Farber, Stephen. "Hollywood Maverick." Film Comment 15, no. 1 (January–February 1979): 26–31.

Faulkner, William. "A Letter to the North." Life, 5 March 1956, 51–52.

Freund, Charles. "Pods over San Francisco." Film Comment 15, no. 1 (January–February 1979): 22–25.

"Georgia Adopts 'Nullifying' Bill." New York Times, 14 February 1956, sec. 1, p. 16.

Greenberg, Harvey Roy. "Raiders of the Lost Text: Remaking as Contested Homage in Always, " this volume, 115–130.

Hall, Stuart. "Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation." Framework 36 (1989): 68–81.

Harvie, William J. III. From Brown to Bakke: The Supreme Court and School Integration, 1954–1978. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Jacobs, Lea. "Censorship and the Fallen Woman Cycle." In Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman's Film, edited by Christine Gledhill, 100–112. London: BFI Books, 1987.

Kael, Pauline. "Pods." The New Yorker, 25 December 1978, 48, 50–51.

Kaplan, E. Ann. "Dialogue." Cinema Journal 24, no. 2 (winter 1985): 40–41.

Kellner, Douglas. "David Cronenberg: Panic Horror and the Postmodern Body." Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory 13, no. 3 (1989): 89–101.

LaValley, Albert J., ed. Invasion of the Body Snatchers. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989.

Lindsay, Robert. "Coast Doctor's Murder Trial Draws Abortion Foes' Interest." New York Times, 10 April 1978, sec. 1, p. 18.

Lipsitz, George. Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

"Messiah from the Midwest." Time, 4 December 1978, 22, 27.

Milbauer, Barbara. The Law Giveth: Legal Aspects of the Abortion Controversy. New York: Atheneum, 1983.

Milberg, Doris. Repeat Performances: A Guide to Hollywood Movie Remakes. Shelter Island, N.Y.: Broadway Press, 1990.

"Miss Lucy v. Alabama." New York Times, 12 February 1956, sec. 4, pp. 1–2.

Nowlan, Robert A., and Gwendolyn Wright Nowlan. Cinema Sequels and Remakes, 1903–1987. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 1989.

"Patients Diagnose Doctors." Time, 13 February 1956, 46.

"Psychiatry for Industry." Time, 13 February 1956, 45.

Rubin, Eva R. Abortion, Politics and the Courts: Roe v. Wade and Its Aftermath. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Ryan, Michael. "The Politics of Film: Discourse, Psychoanalysis, Ideology." In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 477–486. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

"Salk Award." Time, 6 February 1956, 74.

Samuels, Stuart. "The Age of Conspiracy and Conformity: Invasion of the Body Snatch-

ers. " In American History/American Film: Interpreting the Hollywood Image, edited by John E. O'Connor and Martin A. Jackson, 203–217. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1979.

Sayre, Nora. "Watch the Skies." In LaValley, 184.

Schickel, Richard. "Twice-Told Tales." Time, 25 December 1978, 82.

"School Integration Report: The Situation in 17 States." New York Times, 19 February 1956, sec. 4, p. 7.

Silverman, Stephen M. "Hollywood Cloning: Sequels, Prequels, Remakes, and Spin-Offs." American Film 3, no. 9 (July–August 1978): 24–27, 29.

Simonet, Thomas. "Conglomerates and Content: Remakes, Sequels, and Series in the New Hollywood." Current Research in Film 3 (1987): 154–162.

"South Rises Again in Campaign to Delay Integration." Life 6 February 1956, 22–23.

"2 Charge 'Jealous' Doctor Killed 'Test-Tube Baby.'" New York Times, 18 July 1978, sec. 2, p. 9.

"Trouble in Affluent Suburb." Time, 25 December 1978, 60.

Two—

Algebraic Figures:

Recalculating the Hitchcock Formula

Robert P. Kolker

Alfred Hitchcock was a director of elegant solutions. His best films are well-tuned cinematic mechanisms that drive the elements of character, story, and audience response with a calculated construction that creates, anticipates, yet never quite resolves the viewer's desire to see and own the narrative. Hitchcock's films make us believe that we understand everything even while they leave us unsettled about what we have seen and unsure about our complicity in the event of seeing itself. Even his less-than-perfect films, in which too much is spoken and too much resolved, there are sequences or shots of formal inquisitiveness that concentrate the attention and reveal a filmmaker who, although his interest is less than thoroughly engaged, can formulate a cinematic idea and calculate it to a small perfection. Hitchcock is one of the few commercially successful filmmakers who give the viewer pleasure by means of his formal deliberations. For popular cinema—a form of expression dedicated to hiding its formal structures—this is a major achievement.