Chapter Four—

Fedor Shekhtel:

Aesthetic Idealism in Modernist Architecture

Fedor Shekhtel is unique among Russian architects at the turn of the century, not only in his record of accomplishments over three decades but also in his coherent expression of the cultural aspirations—and contradictions—of an era that transformed Russia. More than that of any other architect, Shekhtel's work embodied and enlarged the creative possibilities of the style moderne; yet he retreated from modernism after 1908 and returned to the forms of traditional Russian architecture. His career, supported by Moscow's enlightened, progressive merchant patrons, ultimately demonstrated the limits of aestheticism in a milieu dominated by commerce and industry.

Born in 1859, Fedor (Franz) Shekhtel grew up in a close-knit community of German immigrants in the Volga town of Saratov. His father, who died in 1867, was a civil engineer, and his mother—Daria, née Zhegina—was of merchant background, with numerous relatives in both Saratov and Moscow. In 1875, after attending a Catholic secondary school, Shekhtel joined his family in Moscow, where his mother's connections provided security for her children and furthered Shekhtel's education and career.[1] There seems to have been no doubt concerning his talent for drawing and love for the theater.

Indeed, Shekhtel's early work belongs more properly to various forms of decorative and theatrical art than to architecture. School records show that Shekhtel was not a very diligent student during his two years (1875–1877) in advanced classes at Moscow's School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture; but at the same time, he pursued design work ranging from title pages for books and journals to theater posters to sets and theater decoration in collaboration with such impresarios as Mikhail Lentovskii.[2] His mother's position as household manager for Pavel Tretiakov gave Shekhtel ready access to art patronage in Moscow, and his extraordinary natural abilities as both painter and designer removed whatever stigma might have attached to his lack of a formal degree.

From the mid-1870s to about 1882 Shekhtel served his apprenticeship in the office of Aleksandr Kaminskii, an architect much sought after by Moscow's merchant elite in the 1870s and the recipient of numerous commissions from Pavel Tretiakov.[3] During this period Shekhtel appears to have designed at least one private house; but more important, Kaminskii's extensive connections complemented those Shekhtel had formed with the Tretiakovs. In the mid-1880s Shekhtel worked in the office of Konstantin Terskii, who had studied both at the Moscow School and at the Petersburg Academy of Arts, where he received a degree in 1875.[4] Like most fashionable Moscow architects of the time, Terskii had adopted the Russian Revival style, and it was under his auspices that Shekhtel designed the highly ornamented facade of the Paradise Theater (1886; Fig. 119). This was

Fig. 119.

Paradise Theater, Moscow. 1886. Konstantin Terskii, Fedor Shekhtel

(Brumfield M174-6).

the first major exterior design by Shekhtel to be realized, with an exuberance of detail that rivals Chichagov's Korsh Theater (1885; see Fig. 13).

Even as his interest in architecture developed, theater remained indispensable to Shekhtel's artistic imagination; appropriately, one of his closest friends among fellow students at the Moscow School was Nikolai Chekhov, the older brother of Anton, who arrived in Moscow two years later.[5] Shekhtel's close and early acquaintance with the Chekhov family established him among contemporaries whose interests paralleled his own; moreover, it fostered a close friendship between Shekhtel and Anton Chekhov, two of the leading participants in Russia's cultural renaissance at the turn of the century. From 1886, when Shekhtel designed the title page for Chekhov's first published collection of stories, to 1910, when he built a library-museum in Chekhov's birthplace, Taganrog, as a memorial to the writer, Shekhtel and Chekhov found support in each other's work.

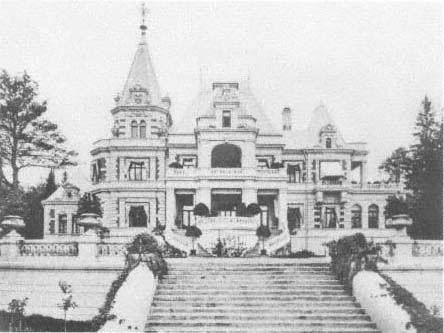

By 1890 Shekhtel had designed and built his first independent projects, including the spectacularly stagy house for S. P. von Dervis at Kiritsy (near Riazan) that combined Gothic, Moorish, and Russian elements on a "neoclassical" terrace. The scant evidence of other estate and country houses he built at the same time (including one for the textile magnate Vikula Morozov) suggests that these were competent but youthful efforts, theatrical and shamelessly eclectic (Fig. 120). In fact, at this point Shekhtel was not yet officially licensed to practice as an architect. After passing a series of examinations in January 1894, he obtained his professional certificate along with the title technician-builder, which allowed him to pursue what had now become his primary career in Moscow.[6]

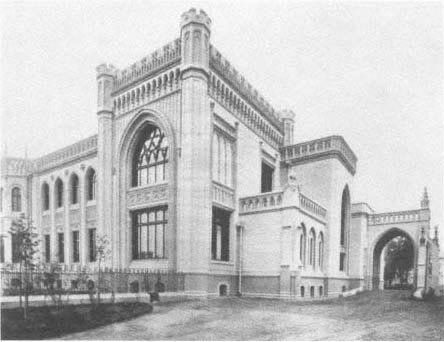

The project that gained Shekhtel his new status was the large pseudo-Gothic townhouse for Zinaida Morozova, the wife of the Maecenas and industrialist Savva Morozov.[7] Construction of the design, which dates from 1893, took some three years, and although both the interior and exterior display the ostentatious striving for effect typical of that time (cf. Fig. 53), the project is more than an accomplished rendition of late nineteenth-century baronial splendor (Fig. 121). Like Viollet-le-Duc and Ruskin, a number of Russian critics interpreted the Gothic as the repository of authentic structural values, of an organic unity between appearance and structure, between interior and exterior. Whether Shekhtel knew of these ideas or merely assimilated a widespread fashion, in this house he developed a Gothic stylization of interior space that went beyond the decorative elements.

On the exterior, Shekhtel discarded symmetry in favor of a balanced combination of forms that reflected the design of the interior. He used stylized elements on the exterior—the lancet windows, the Gothic tracery,

Fig. 120

Vikula Morozov house, Odintsovo-Arkhangelskoe, near Moscow. Ca. 1895. Fedor

Shekhtel. Zodchii , 1899.

Fig. 121.

Zinaida Morozova house, Moscow. 1893–1896. Fedor Shekhtel. Arkhitekturnye

motivy , 1899.

the crenellated parapet—as well as in the interior, with its woodwork and stonework. But the advantage of the Gothic structure for Shekhtel lay in its adaptability to a free interpretation. The windows of the main facade, of varying sizes, not only reflect the arrangements of rooms but also create distinctive areas of light.

Although the exterior is imposing, the rooms are compactly arranged—in relative terms, of course. Not even the largest rooms extend the full two stories: the lower half of the great Gothic window facing the street illuminates the dining room, the upper half Zinaida Morozova's bedroom suite. Neither room is small; but it is hard to imgine an architect in New York or Petersburg ignoring the possibilities of a two-storied hall behind this window. The other rooms on each floor were arranged along a corridor and designated for family use. This practical, if unimaginative, arrangement, which corresponded to the traditional separation of state and living rooms in Russian houses of the neoclassical era, would be superseded by the centralized core plan of the Stepan Riabushinskii house.

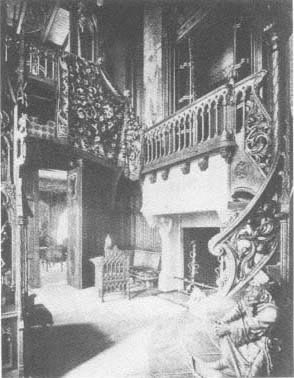

Shekhtel also built a one-storied extension to the house for a lavish baroque ballroom, connected to the main structure through the vestibule (Fig. 122). (For this vestibule, with its stairway to the second floor, Mikhail Vrubel created a stained glass panel, The Knight , in 1896.) Although the extension is not immediately visible from the street, the Gothic window that projects from the front marks its axis. In this project Shekhtel demonstrated a masterful grouping of structural components that enabled exterior accents to reveal interior function.

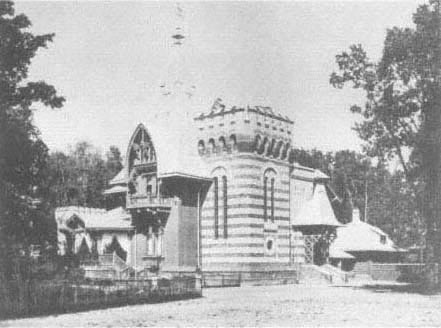

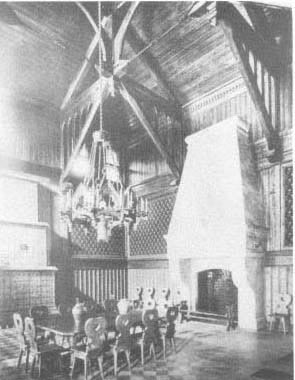

Shekhtel's professionalism in designing the Zinaida Morozova house did not, however, represent his emancipation from a traditional, academic approach to building. Gothic theatricality had yet to run its course in Shekhtel's imagination, as is evident from the dacha he built in 1895 for Ivan Morozov in Petrovskii Park, a suburban playground for Moscow's rich. The timber hammer-beam roof over the great dining hall—a rustic variant of the Gothic—dominated the structure (Figs. 123, 124); and Shekhtel used similar pseudo-Gothic motifs in remodeling the interiors of other Moscow houses belonging to the Morozovs (Fig. 125).[8]

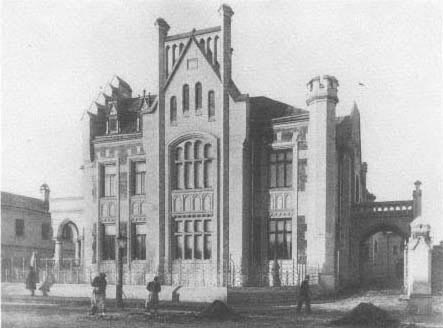

A more austere, if hardly modest, interpretation of the pseudo-Gothic appeared in Shekhtel's house for K. V. Kuznetsova (1896).[9] The stonework of the house had medieval touches, but the placement of the windows in rectangular shafts, outlined in stone on brick, suggests the Renaissance rather than the Gothic (Fig. 126). These stylistic features, though they emphasized the tectonic clarity of the building, seem to have been a matter of fashion. In this respect the Kuznetsova house is particularly helpful in marking the transition from Shekhtel's historical stylizations of the mid-1890s to his style moderne designs such as the Derozhinskaia house (see Figs. 148–157), whose facade borrowed elements from the central bay of the Kuznetsova house.

In the midst of that transition, Shekhtel pursued a series of major projects that led him from private to public architecture. An 1897 project for a People's House (Narodnyi dom ) in Moscow displayed a heavy Shervudian historicism, with flanking Kremlin-style towers and other seventeenth-century Muscovite details, though the upper structure and cupola echo the Russo-Byzantine style of the mid-nineteenth century. The idealistic, populist tendencies of Shervud's work and writings suffused Shekhtel's, in keeping with the purpose of the People's House to provide theatrical entertainment for the masses.

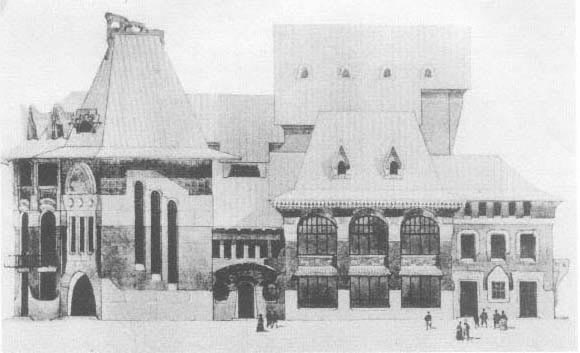

Anton Chekhov served as an intermediary between Shekhtel and the group of civic-minded women willing to support a "People's Palace." In a letter to Chekhov, Shekhtel noted that although the term "People Palace" (his English) might be acceptable in America, it was inappropriate for Russia.[10] He chose instead the name People's House—as in Victor Horta's Maison du Peuple, then under construction in Brussels. (Whatever Shekhtel's qualms, Soviet planners readily adopted the term palace in naming the structures for culture and rest built throughout the Soviet Union beginning in the 1920s.) Shekhtel included in the design of the People's House a large theater, lecture halls, a library and reading room, a teahouse, and commercial space for shops. The "Muscovite" decorative style affirmed the Russian cultural heritage (as did the Historical Museum) and appealed to popular taste. Although only a few of the People's Houses designed before 1917 were ever contructed, the concept itself attests to a growing sense of social awareness in architecture.

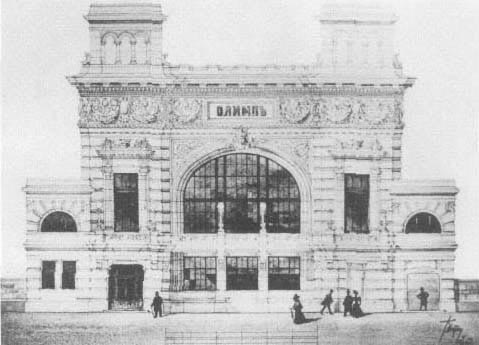

Indeed, Shekhtel designed a number of other public projects (all unbuilt), including a wooden People's Theater for Sokolniki Park (1897) whose floor plan prefigured the three-wedged design Konstantin Melnikov would use for the auditorium of his Rusakov Club (1929). Although Shekhtel's published drawing for the Olympus Concert Hall (1898) displays an entirely different aesthetic standard, with its Beaux-Arts facade (Fig.

Fig. 122.

Zinaida Morozova house, vestibule.

Photograph ca. 1898.

Fig. 123.

Ivan V. Morozov dacha, Petrovskii Park, Moscow. 1895. Fedor Shekhtel. Zodchii ,

1899.

Fig. 124.

Ivan V. Morozov dacha, dining hall. Zodchii , 1899.

Fig. 125.

A. V. Morozov house, Moscow. Ca. 1897. Fedor

Shekhtel. Hall. Arkhitekturnye motivy , 1899.

Fig. 126.

K. V. Kuznetsova house, Moscow. 1896. Fedor Shekhtel.

Photograph ca. 1897.

127), he had not abandoned his fascination with the popular theater. In 1902 Zodchii reproduced his drawing for a People's House of the Society for the Diffusion of Educational Popular Entertainment in Moscow, designed not in the historicist or eclectic manner but in a colorful neo-Russian variant of the style moderne with complex intersecting planes, steeply pitched roofs, and large arched windows, echoed by a two-storied arch over the principal entrances (Fig. 128).[11] It resembles Shekhtel's other "neo-Russian" projects of the period, such as the pavilions for the 1901 Glasgow exhibition and the Iaroslavl Station.

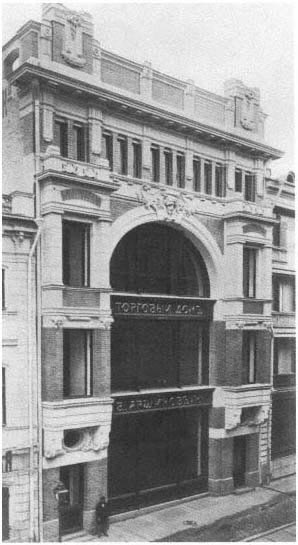

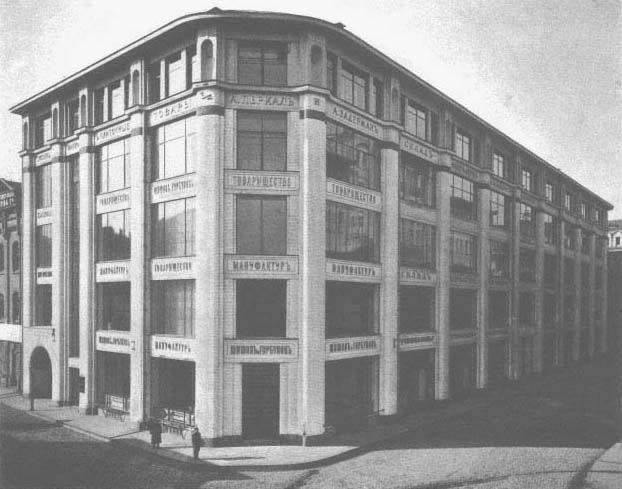

Besides private houses and unfulfilled visions of public buildings, Shekhtel designed several commercial structures during the late 1890s. His earlier effort in commercial architecture, a store for Penskii and Levenson on Petrovka Street (not precisely dated but before 1890), has not survived. In 1898 he designed the headquarters of the M. S. Kuznetsov company (Fig. 129), a leading producer of porcelain, glassware, and ceramics in Russia.[12] He had already designed a house for M. S. Kuznetsov, and his handling of the showrooms and office space for the firm on Miasnitskaia Street reveals a thorough understanding of commercial architecture and its technical requirements. The display rooms, though not large by American standards, required open space, which Shekhtel created by using iron columns and loadbearing reinforced-concrete walls—structural elements frequently used in Russian commercial architecture at the turn of the century.[13]

By eliminating the need for extensive vaulting on the interior, Shekhtel was able to open the exterior wall with four three-storied arched windows, with recessed spandrel beams at floor level. This arrangement not only flooded the interior with light but also lessened the weight on both wall and foundation. The fourth floor, used for offices, rests incongruously on the massive arcades (a fifth floor was added after the revolution), but Shekhtel's glass surface at the Kuznetsov building heralded the modern age in commercial space for central Moscow. This tectonic development was prefigured in Shekhtel's earlier work—the masonry and glass facade of the Zinaida Morozova house, for example.

The vertical shafts separating the large glass planes of the Kuznetsov Building are still in the neo-Renaissance style, however, as massive rustication on the ground floor gives way to the heavy quoins (the "Gibbs surround") at the second and third stories. Not content

Fig. 127.

Project drawing for Olympus Concert Hall, Moscow. 1898. Fedor Shekhtel. Zodchii , 1899.

Fig. 128.

Project for People's House, Moscow. Fedor Shekhtel. Zodchii , 1902.

Fig. 129.

Kuznetsov building, Moscow. 1898. Fedor Shekhtel (Brumfield M121-22).

with this ponderous detailing of the sandstone, Shekhtel separated the windows with large terms surmounted by outsize female masks. This decorative device became a cliché on cornices and elsewhere on facades, and many Moscow buildings adorned in the new style display these masks (the moderne's answer to the bucranium), which represent a fin-de-siècle ideal of feminine beauty.

The following year, 1899, Shekhtel repeated many of these elements in a smaller commercial building for the V. F. Arshinov firm in the old Kitai-Gorod district (Fig. 130). A three-storied arched window occupies most of the narrow facade, providing light for the display rooms that extend to the back of the building, which has iron columns for floor supports. The fourth floor, for office use, counterbalances the glass arch with a strip of narrow windows along the facade. Here, in contrast to the Kuznetsov building, the skeletal frame is lightly outlined by the mullions and spandrels of the central window, while the stonework blends onto the surface of lightly glazed blue brick. As in many of Shekhtel's designs of the 1890s, the facade is defined by verticals (in this case window shafts) on either side of the center—a solution suited to the restricted scale of the Arshinov building. Despite the Renaissance allusions of the facade, Shekhtel's use of glass and glazed brick anticipates a rationalism in which aesthetic properties derive from the material and the proportions of the frame.

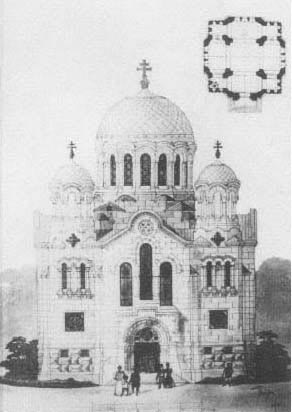

During the 1890s Shekhtel defined his interest in yet another building type—the Russian church. Although his numerous designs for the construction and decoration of churches are related to his early endeavors in painting icons, his first commissions, in 1897, were to redecorate the interior of a church at Moscow's Danilov Monastery and the Church of St. Pimen on Vorotnikov Lane. The extent of this work is not well documented, but neither church would have required major structural changes. These projects no doubt helped Shekhtel to obtain the commission for the large Church of the Savior in the city of Ivanovo-Voznesensk, a textile center some three hundred kilometers northeast of Moscow.

Shekhtel's design for this church relied on the neo-Byzantine style typical of Orthodox church architecture in the later nineteenth century (Fig. 131). The pentacupolar structure, faced in cut stone, followed the usual cross-domed model of medieval Orthodox churches; but the plan was highly centralized, with the four corner

bays reduced to small spaces between the arms of the cross. The appearance and the details of the Church of the Savior—from the hemispheric domes to the window design—were broadly related to the High Paleologan style; yet there is no evidence that Shekhtel studied late Byzantine architecture. Nor would he have needed to: his design closely resembles Andrei Huhn's 1886 project for a cathedral at Glukhov (in Chernigov Province), even to the placement of the corner cupolas on polygonal arcades rather than on enclosed drums. Although the features of the Church of the Savior reflected the wishes of the church authorities who commissioned it, the design Shekhtel submitted was a conservative one, unrelated to experiments in freestyle church architecture at the beginning of the century.

Fig. 130.

Arshinov building, Moscow. 1899. Fedor Shekhtel.

Zodchii , 1902.

In 1899 Shekhtel created a more imaginative design for a new cathedral at the Rozhdestvenskii (Nativity) Convent in Moscow (Fig. 132). If it was intended to replace the old cathedral, we are fortunate that it was never built, for the original building is one of the few extant examples of Muscovite architecture at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Shekhtel's design was nonetheless original in its muting of Byzantine elements and its emphasis on verticality, which suggests the sixteenth-century tower churches in the Moscow area—such as the Church of the Decapitation of John the Baptist at Diakovo. The bulbous cupolas are a traditional Russian element, but the exterior decorative work—particularly the large panel (perhaps mosaic) portrayed in the elevation—announces that this is no

Fig. 131.

Church of the Savior, Ivanovo-Voznesensk. 1898.

Fedor Shekhtel. Arkhitekturnye motivy , 1899.

Fig. 132.

Cathedral, Rozhdestvenskii Convent, Moscow. 1899.

Fedor Shekhtel. Arkhitekturnye motivy , 1899.

simple stylization but rather a product of the crafts revival. With its stone facing and complex geometric relations, this project represents Shekhtel's closest approach to freestyle church design.[14]

In 1899 Shekhtel also designed two chapels: a private chapel for G. A. Zakharin in the distant Moscow suburb of Kurkino and an addition to the Church of St. Vasilii Kessariiskii in the Tverskaia-Iamskaia district (Moscow; not extant), which commemorated the wedding of Nicholas II and Alexandra (1894). The latter chapel had a tent spire on a square limestone tower with seventeenth-century decorative detail (Fig. 133).[15]

By the end of the century, the forty-year-old Shekhtel had amassed an impressive list of works, built or

Fig. 133.

Commemorative chapel, Church of St. Vasilii

Kessariiskii, Moscow. 1899. Fedor Shekhtel.

Arkhitekturnye motivy , 1899.

projected, ranging from neo-Gothic mansions to functional commercial buildings. He had also become known as a master of interior design, integrating the applied arts into architectural space. In a profession concerned with publicizing its product in the press, Shekhtel (along with Kekushev) had become one of the most frequently published architects. Photographs and sketches of his work appeared not only in the Moscow periodical Arkhitekturnye motivy but also in the major professional journal, Zodchii . To be sure, such publicity reflected the stature of Shekhtel's clients as much as it did his own talent.

The roster of his patrons was impressive: the Kuznetsovs, Levensons, and multitudinous Morozovs as well as lesser-known people of means in Moscow. Although Shekhtel was aware of broader social purposes in

architecture, he was in a sense constrained to work in the taste of his wealthy clientele, the late nineteenth-century Muscovite merchantry. Even though the mansion he built for Savva and Zinaida Morozov marked an important stage in his mastery of architectural space, this and other Shekhtel buildings of the period show scant evidence of an innovative vision. Yet that vision existed, for without it one would be at a loss to explain Shekhtel's surge of creativity at the beginning of the century.

Both continuity and evolution are evident in his design for the A. A. Levenson Printing Works on Mamontov Lane (1900), a building that re-created a historical style (a French château of the early Renaissance) in a functional commercial and industrial structure.[16] Yet Shekhtel clearly maintained the dichotomy between romantic historicism and functionalism, even if it is not immediately visible. The front part of the building—the "château"—contained editorial and business offices on three floors under a steeply pitched roof like that common to Russian Revival buildings of the late 1890s (Figs. 134, 135).

The complex roofline is characteristic of Shekhtel projects at the beginning of the century (particularly his People's House design of 1902), with its antecedents in various Russian historical stylizations. At the same time, the vertical accents and steeply pitched roof show a similarity with art nouveau, as in the work of Emile André at Nancy and of Hector Guimard. And in the details of the main facade, constructed of yellow brick and stucco scored to resemble ashlar, an even greater variety of aesthetic currents was combined.

At the top of the central, projecting, window shaft, in a framework defined by large rectangular bays, Shekhtel placed a circular window; he used arches in the windows of the third story, in the mullions on the second story, and in the ground-floor entryway, where an arch shelters a bentwood door frame—now sadly defaced but still showing the outlines of perhaps the best example of an art nouveau motif in Moscow architecture.[17] The influence of art nouveau also appeared in the curved wrought-iron brackets originally framing the entrance and in the thistles on either side of the central bay in front and at the base of the projecting corner bay. An inset stucco panel on the facade portrays printers at work in a tableau that suggests the dignity of labor espoused by William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement.[18]

This agglomeration of elements reflects the often contradictory impulses of the early style moderne. Behind the relatively small office structure, with its idealized representation of craft labor, is the purely functional printing plant itself, which extends from the back wall of the offices. Despite its unadorned surface, the plant displays the same attention to detail as the rest of the building. The large window bays are supported by piers of pressed yellow brick, and the floors rest on a double row of iron columns that obviate the need for interior support walls—a construction typical of Shekhtel's commercial architecture. By the middle of the decade Shekhtel would bring this structural rationalism "up front" in the most advanced of his commercial building designs, for the Riabushinskii brothers.

Even in 1900, however, when Shekhtel had only begun to explore the romantic interpretation of the new style and its aesthetic possibilities, the Riabushinskiis were prominent supporters of his work, as the Morozov clan had been in the 1890s. Although the diverse cultural, political, and economic interests of the large Riabushinskii family cannot be reduced to a brief summary, the shared purpose that informs the Shekhtel-Riabushinskii collaboration demands that something be said of these cultured representatives of the Moscow merchantry.

The family members for whom Shekhtel worked were all sons of Pavel Mikhailovich Riabushinskii, himself the son of an Old Believer peasant who had clerked for a shop in Moscow's Merchants' Yard (Gostinnyi dvor, behind the Upper Trading Rows) during the 1820s and 1830s. This Mikhail Riabushinskii acquired the Moscow shop in 1844, afterward purchasing a series of textile mills that gave him control over both supply and retail operations. When he died in 1858, his two sons, Pavel and Vasilii, controlled the business; Pavel proved the more productive in every sense.

Born in 1820, he was the true founder of the Riabushinskii conglomerate, the guide of the Trading House of the Riabushinskii Brothers (founded in 1867) as well as the patriarch of a wealthy Russian bourgeois family. Pavel Mikhailovich, who married twice, had six daughters from his first marriage, which ended in divorce in 1859, and sixteen more offspring from his second marriage (in 1870), including nine sons, six of whom achieved prominence in Moscow's political, financial, and cultural circles. The firm of P. M. Riabushinskii and Sons, organized from the earlier Trading House in 1885,

Fig. 134.

Two views of the Levenson Printing Works, Moscow. 1900. Fedor Shekhtel. Zodchii , 1902.

Fig. 135.

Levenson Printing Works, main facade (Brumfield M-42).

passed unchanged to the sons after Pavel's death in 1897; and although the family diversified its holdings during the 1900s, textile mills continued as the basis of the family's wealth.[19]

Shekhtel's successes among the leading merchant families in Moscow would easily have come to the attention of the Riabushinskiis; but he did no work for them before 1900, probably because until then power was concentrated in one patriarch's hands. Only after Pavel Mikhailovich's death would the individual sons establish households or make major changes in the family business. Indeed, at the turn of the century, the sons were still in their twenties—or younger. (The Morozovs, by contrast, had branched much earlier and represented a more "mature" fortune.) Although no specific evidence, such as correspondence, is yet available on the collaboration between Shekhtel and the Riabushinskiis, it is fitting that the only private house he built for them was commissioned by Stepan, one of the most dedicated and knowledgeable icon collectors of his time.

Despite Stepan's relative seniority among the brothers (he was the fourth, born in 1874), he was only twenty-six when the house was built—a fact that may explain why Shekhtel emphatically used the modern style in both architecture and decoration (see Plate 14). Although elements of his earlier work are evident here, the form departs significantly from anything he had previously built or projected. The blocked, rectangular outlines of the structure had a precedent in Kekushev's house for E. List (see Fig. 83); and the work of William Walcot further demonstrated the possibilities of applying brick, iron, and glass in a new housing design that owed little to traditional decorative or stylistic patterns.[20] All three architects, viewed as the leading Russian modernists by contemporary critics, had moved toward a plan that grouped components around a central space. As for precedents in the decorative arts, Kekushev had included ceramic panels on the exterior of the List house, and similar designs appeared on a larger scale in contemporary apartment houses.

Having acknowledged these antecedents, one is still confronted with the remarkable novelty of the Riabushinskii house in Moscow, where no other private dwelling displayed the new aesthetic with such panache and so thorough a knowledge of contemporary design—from Hector Guimard to Joseph Olbrich. Indeed, Olbrich's detached private dwellings—in contrast to the art nouveau townhouses of Paris and Brussels—closely resemble Shekhtel's design for Riabushinskii (particularly the house Olbrich built for the sculptor Ludwig Habich at Matildenhöhe, with the same block arrangement of mass and a flat overhanging roof). The Riabushinskii house, begun in 1900 and completed around 1902, however, is contemporary with—or predates—the house designs of Olbrich near Darmstadt.[21]

Shekhtel also incorporated modernized Russian motifs into his design: the heavy porch is like the kryltso (porch) attached to the entrance of seventeenth-century Muscovite churches; and the two small windows on the upper right front facade, in contrast to the art nouveau contours of the main windows, suggest the narrow windows of a medieval Muscovite terem , a dwelling with a tower. Although the ebullient exterior ornament—the mosaic frieze and the wrought-ironwork, for example—seems far removed from traditional Russian architectural ornament, it refers to both the crafts revival in Russia and the polychromatic patterns of medieval Russian architecture. At the Riabushinskii house, Shekhtel merged the old Muscovite concept of the teremok and the palaty with the most contemporary interpretation of the osobniak , or detached private dwelling.

This counterpoint of the historical and the modern is only one of several contrasting elements Shekhtel developed. The yellow walls of glazed brick provide a backdrop for a rich array of ornamental effects: large windows with bentwood mullions, wrought-iron balcony railings in a fish-scale pattern, and a mosaic frieze depicting irises against clouds and an azure sky. The frieze, with its colors and luxuriant forms, is the most arresting feature of the exterior, for the way in which it defines and seems to enlarge the house. What might have been dead space is unified by this band of color whose subtlety is a tribute to the revival of mosaic work in Russian church architecture (see Plate 15). The oneiric world Vrubel had portrayed in ceramic at the Hotel Metropole (in The Princess of Dreams ) is here enhanced by the reflective smalti that give the mosaic frieze the luminosity and pointillist effect of impressionism. Of the many art nouveau decorative conceits in European architecture, Shekhtel's mosaic ranks among the most daring technically; moreover, it denies tectonic logic even as it unifies the spatial contours of the house. The portrayal of the sky negates the materiality of the upper walls, for it suggests not an enclosure of interior space but a view beyond.

Following the principle of textural juxtaposition, Shekhtel created two large porches, one at the main entrance and the other on the side of the house, facing an

Fig. 136.

Stepan Riabushinskii house, Moscow. 1900–1902. Fedor Shekhtel. Side facade (Brumfield M169-11).

enclosed yard (Fig. 136). In each case the molded concrete is the antithesis of the rectilinear basic structure. This is particularly evident in the arched openings of the side porch adjacent to the dining room (see Plate 16). The front porch also exploits the plasticity of the material in a rusticated treatment that suggests the entrance to a cave or grotto. The suggestion is not accidental, for the aquatic theme (as in the fish-scale pattern in wrought iron) continues on the great mahogany door, with its brass lotus pattern in the block style of the Secession.

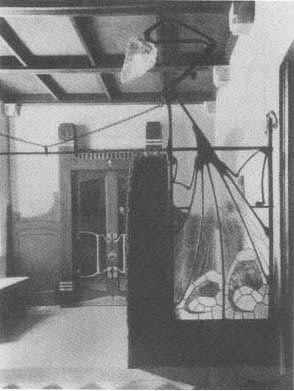

This theme re-emerges in the vestibule, where the mosaic ripple pattern of the floor suggests a shallow pool. The walls, scored like those of the porch, are painted pale green in the central area of the house; but within this submarine ambience are areas of brilliant color, as in the large stained glass panels flanking the passage from the vestibule to the hall (Fig. 137). These panels, now hidden by cabinets, represent the diaphanous wings of a dragonfly, its form outlined in wrought iron, its craning neck culminating in a "head" of rough crystal (since replaced by an ordinary frosted-glass globe).[22]

This display of the grotesque conveys the impression of an unbalanced world, although there is no reason to link the impression to Stepan Riabushinskii. Indeed, the socio-cultural implications coexist with the sheer inventiveness of contrasting material, texture, and color. The simplicity of mahogany and brass on the pale walls (where every detail bespeaks Shekhtel's design) provides a setting for brilliant decorative work, as did the simple detailing of the exterior brick walls. An additional stained glass panel in the hall—above the large mirror facing the entrance—portrays a stylized landscape devoid of human figures.

The essence of Shekhtel's centralized plan for the Riabushinskii house is the space created for the central stairway, beyond the stained glass panel. Although most of the rooms open onto this central space, each room also communicates with those adjacent to it; every element is integrated in a plan that extends from the central core and ultimately shapes the exterior (Fig. 138). Shekhtel's plan represents a concept of structure—from interior to exterior—characteristic of the style mod-

Fig. 137.

Riabushinskii house, vestibule.

Photograph ca. 1903.

erne. But another source of inspiration originated in the form of the medieval Russian church. Like the Riabushinskii house, the church structure developed from a central core: the main drum and cupola, supported by four piers. In the traditional plan, the length and width of the aisles (the arms of the cross) derived from the dimensions of the center space; all other components, from interior to exterior, followed therefrom. And just as the windows of the main drum lighted the central area of the church, a pitched skylight (visible from the exterior) and a large stained glass window illuminated the center of the Riabushinskii house.

Like Viktor Vasnetsov, who in the Abramtsevo church reinterpreted the structural logic of the early medieval church, Shekhtel himself created a centralized plan combining the moderne and the medieval, leaving exposed two columns extending upward through the core space in an allusion to the piers of the church. Although references to medieval architecture are highly abstracted in this secular environment, Stepan Riabushinskii housed his icon collection in this setting, with

Fig. 138.

Riabushinskii house, plan.

its contemporary "decadent" motifs. This contrast between the religious and the secular was resolved elsewhere in the house (see pp. 136–39).

For the main part of the interior, Shekhtel turned to the extravagant and the grotesque, as he had in designing the house for Zinaida Morozova. Again his approach to decoration was comprehensive, as he applied the arts of wood, fabric, stained glass, plaster, brass, wrought iron, and wall painting in modern ways that were nonetheless related to the Russian crafts tradition. Although his designs suggest isolated similarities to sources as diverse as Mackintosh, Hoffman, Olbrich, Eugène Gaillard, and Louis Majorelle (in the wood veneer with marquetry), Horta and Tiffany (in the stained glass), and August Endell, Shekhtel's application of the decorative arts remained highly idiosyncratic.

Nowhere is the idiosyncrasy more obvious than in the design of the central stairway (see Plate 17). The stairwell is lit dramatically by natural and electric sources, each with its own theatrical effect. The stained glass window at the back corner of the stairwell, where two

walls intersect, extends the full height of the structure, although the glass panels are in three segments. The largest rises from the middle landing to the ceiling; in it a spiral or conch surrounds a light-colored center of frothy bubbles (see Plate 18). By filtering the light for the central part of the house through this screen, Shekhtel created here the most convincing impression of a submarine environment in the house. (The light is doubly filtered, since the architect placed a passageway between the stained glass panel and the exterior window that admits the light.) Riabushinskii, it seems, wished to surround himself with a sea kingdom comparable to the one brilliantly portrayed in contemporary stage sets for Rimskii-Korsakov's opera Sadko (1896), whose hero obtains fabulous wealth after descending to the realm of the Sea King. Both patron and architect would have been familiar with the contents and the staging of this opera, which premiered in Moscow in January 1898.[23]

The elaborate stagecraft of the stairwell extends to the main source of electric light—and the balustrade to which it is attached. The balustrade is in every sense the centerpiece of Shekhtel's structure, dominating the core space and marking the ascent of the dogleg staircase from the first floor to the middle level (where there is an alcove) and the second floor (see Plates 19, 20). Its sinuous mass is composed of an aggregate known in Russian as artificial marble; more precisely, it is a type of gray terrazzo—cast concrete mixed with marble and granite fragments and polished to a high gloss. (Russian architectural journals of the period contain frequent references to this material under the trade names Scagliola and Terrazzino.)

Shekhtel contained the descent of the frozen wave in a twisting surge that provides a column for a Tiffanystyle lamp, whose light bulbs are placed within stalactitic or medusan tentacles (Fig. 139). The effect here, like that of much art nouveau decoration, is baroque; but the massiveness is atypical of art nouveau—as is evident in a comparison of the balustrade with what could be its prototype: August Endell's delicate wroughtiron stairway in the vestibule of the Atelier Elvira (Munich, 1897–1898; not extant).

At the top of the stairway, the grotesquerie culminates in a polished red column capped by a bronze capital swarming with reptilian forms (see Plate 18). Despite the decadent ornamental touch, the column emphasizes the structural purpose of the core space, supporting and giving shape to the building at its central point. But both the arched opening supported by the column (an opening that faces the central "court" of the structure) and the design of the capital, whose grotesque ornament bears comparison with that on late Romanesque capitals in France, also suggest a cloister. With this column and the large stained glass window, Shekhtel refers to the medieval art of Western Europe, just as his centralized structure is related to the Russian medieval heritage.

By comparison with the central space, the individual rooms are considerably less dramatic, although Shekhtel was attentive to their details and materials. Indeed, the luxury of his materials (wood, fabric, brass) is most obvious in intimate rooms such as the library and the study. There is no attempt to create a grand room. Each space is ultimately subordinate to the central area, which is readily at hand yet can easily be excluded. The largest space is the dining room, the only room with a door to the outside—it leads to the garden at the side of the house.

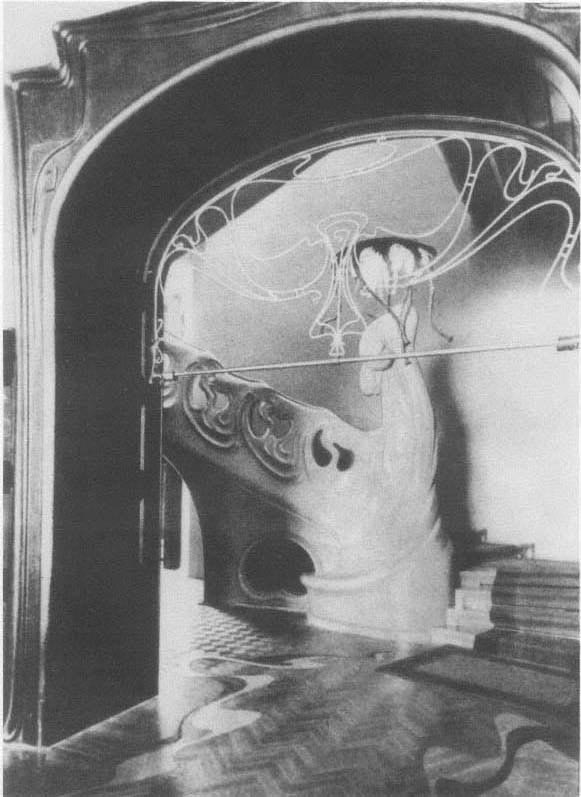

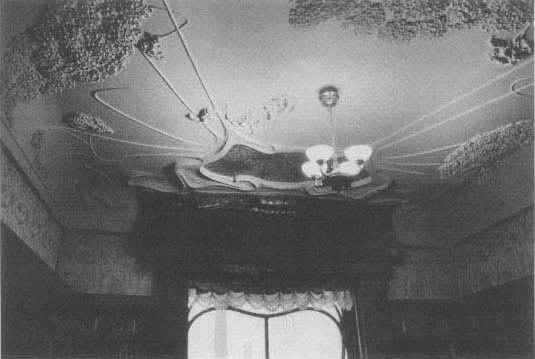

The dining room is a modest version of the banquet hall Shekhtel had created for the Morozovs—with oak wainscoting and simple furniture (Fig. 140). But caprice and fantasy are also at work here: in addition to strips of plaster swirls on the ceiling and curved ironwork over the window, the room originally had as its centerpiece a large white scagliola mantel portraying a dragonfly nymph. The adjoining library, while smaller, displays greater luxury, with walls covered in silk brocade and extensive marquetry in the door panels. The ceiling (Fig. 141), in another of Shekhtel's elaborate conceits, resembles the surface of a pond, with its undulating plaster aquatic plants and large marine snails along the border. The centerpiece of the ceiling is a cartouche of yellow daisies on an azure background. Although the other rooms are generally more restrained in their decoration, all are scrupulously crafted.

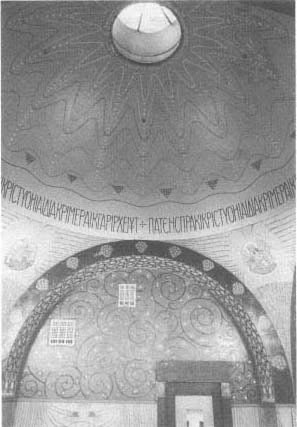

One area of the house, however, exists apart, both aesthetically and physically, from this interrelated system of private rooms and open common space. At the back corner is a square tower at whose base is an entrance to the house. The stairway in the tower, marked by ascending windows (see Fig. 136), leads to an area above the second floor and secluded from the rest of the structure. Although this space has been modified since the beginning of the century, enough remains (or has been restored) to reveal it as the family chapel and to define its place in Shekhtel's design.

The Riabushinskii family adhered to the Old Belief, whose role in Russian architecture at the beginning of the century is noted in chapter 3. Frequently persecuted,

Fig. 139.

Riabushinskii house, stairway, lamp (view from dining room).

Photograph ca. 1903.

Fig. 140.

Riabushinskii house, dining room (Brumfield M135-15).

Fig. 141.

Riabushinskii house, library (Brumfield M135-11). Light fixture is not the original.

Old Believers maintained a strong sense of solidarity that characterized their business as well as religious communities; but in addition to this deeply conservative attitude toward matters of faith, Old Believers were known for their reverent and knowledgeable preservation of religious art, primarily medieval Russian icons. Stepan Riabushinskii's dedication to collecting icons—for aesthetic as well as religious reasons—would have been close to Shekhtel's own interests. Nonetheless, the general design and "iconography" of the Riabushinskii house are secular, albeit with touches of symbolist otherworldliness.

While the living quarters of the house incorporated the latest in contemporary design, the chapel served as the repository of traditional religious values. Shekhtel created a visual effect based on the colors of early medieval icons, using bright red for the pendentives and gilt work for the interior of the dome (which supports a small lantern-skylight). Because of its modest proportions, the entire chapel glows with the brilliance of the dome and pendentives, which are decorated with the traditional allegorical depictions of the four Evangelists (see Plate 21). Light enters both through the lantern and through three narrow windows reminiscent of the earliest Russian church architecture. The windows, on the eastern side of the chapel, are slightly recessed from the arch and pendentives, providing enough space for a small altar behind the icon screen required by Orthodox usage. No photographs of the screen were published, but a 1904 report in Zodchii on the architecture and arts exhibit in Moscow referred to the display of a carved iconostasis designed by Shekhtel for an Old Believer chapel in the Riabushinskii house.[24]

The walls beneath the dome combine traditional and contemporary elements, including the stylized towel motif typically used on the lower portion of church walls. The contemporary is most apparent in the black tendril pattern on the dark green walls and on the gold intrados of the chapel's two arches (Fig. 142). Although derived from the grape-cluster motif on the extrados of the same arches, with its religious connotations of the Eucharist and the parable of the laborers in the vineyard, the tendril pattern also resembles ornamental backgrounds in the paintings of Gustav Klimt, suggesting Shekhtel's fluency in interpreting traditional motifs and symbols in the new aesthetic idiom.

The secular and the religious elements combined in the Riabushinskii house reflect the culture of the entire family, but particularly of Stepan Pavlovich. The family's wealth testified to its skill in modern commercial methods, and the political views espoused by Vladimir and Pavel Riabushinskii later in the decade made clear their expectation that a capitalist economic order would lead Russia into the modern age.[25] At the same time, the Old Believer heritage remained central to their personal identity, both public and private. The chapel, like Stepan Riabushinskii's collection of icons, revealed his aesthetic values and reaffirmed his commitment to a set of religious beliefs that retained their vital force.

Nonetheless, the peculiar conditions of Russia's social transformation at the beginning of the century nurtured an impulse toward radical innovation; and Moscow entrepreneurs like the Riabushinskiis could declare their status and independence in displays of new and contemporary art, however outré. (The life of Stepan's brother Nikolai offers an extreme example of such an ostentatious display.)[26] Although contemporary critics found fault with the house (the entrance porch and the large windows of the first floor, in particular, were described as inconvenient, tiresome, and illogical) they also noted the "boldness" and "courage" of Shekhtel's design,[27] qualities that would have appealed to the owner of the house, however conservative his cultural origins and religious allegiance. Remarkable by any standards of contemporary European modernism, the Riabushinskii house signaled a new era in Moscow architecture; yet it was only the first in a series of structures that ensured Shekhtel's position as a pioneer of modernism in Russia.

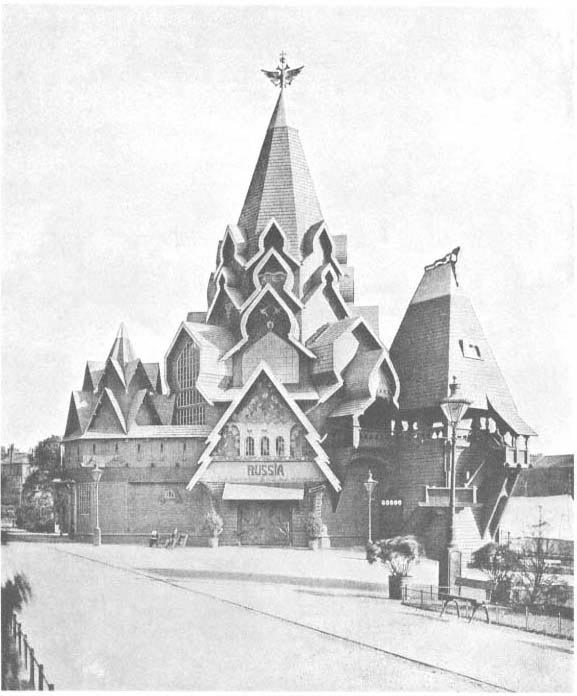

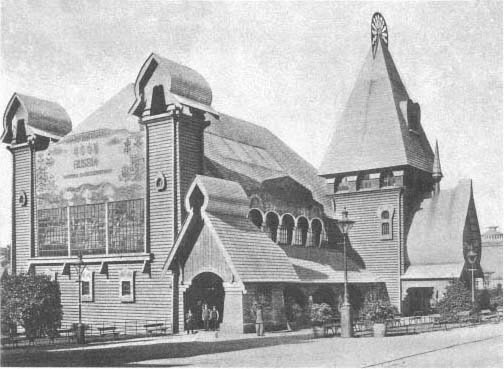

Although Shekhtel's next major project—initiated while the Riabushinskii house was still under construction—seems to have little in common with contemporary design, in it he continued to develop a coherent structure expressive of both function and the decorative arts. When the Russian government commissioned a series of pavilions for the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition, Shekhtel turned to the traditional forms of Russian wooden architecture for the buildings housing exhibits on mining, forestry, and agriculture as well as for the central pavilion (Fig. 143). Despite its mundane intention to market Russian products in Great Britain, the Ministry of Finance exercised unusual aesthetic judgment in entrusting the design to an architect of "advanced" views and in generously supporting the project. In contrast to the eclectic structures elsewhere at the ex-

Fig. 142.

Riabushinskii house, chapel (Brumfield M135-0).

Fig. 143.

Russian section, 1901 Glasgow Exhibition. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

hibition, the Russian pavilions created a strong—if not always favorable—impression with their bold silhouettes and polychromatic decoration.[28]

During the two years preceding the commission from the ministry Shekhtel's work had reached well beyond Moscow's business circles. The first issue of the illustrated journal Arkhitekturnye motivy contained his sketch for a chapel to commemorate the wedding of Nicholas II and Alexandra (see Fig. 133); the project's considerable size and Russian decor must have impressed the proper circles in St. Petersburg. Shekhtel had also designed a triumphal arch with a Gothic tower for the entrance of Their Imperial Highnesses to the 1896 Nizhni Novgorod exhibition, as well as a pavilion—modest, but decorated in the Russian Revival style—for the firm of Kharitonenko at the 1900 International Exposition in Paris.[29]

At Glasgow, the ministry provided Shekhtel with 30,000 rubles in construction funds and a skilled labor force of 210 peasant carpenters, supplemented by the six graduates of Moscow's prestigious Stroganov School of Technical Design who carried out Shekhtel's design for the ornamental painting.[30] The carpenters provide the key to the architect's intention: a modernized interpretation of native wooden structures, which are among the most ingenious forms of Russian architecture. By returning to the organic building material par excellence, Shekhtel continued the work of Hartman in the massive wooden structures for the 1872 Polytechnical Exhibit and Ropet in the designs at Abramtsevo.

Shekhtel had already designed a wooden theater for Sokolniki Park in Moscow, but it was austerely functional, unlike the picturesque Glasgow pavilions, based in part on wooden churches of the far north but in other respects wholly the product of Shekhtel's imagination. Around the central pavilion—the building closest to the traditional prototypes with its pyramidal silhouette and large tent roof—the rest of the Russian buildings were grouped (Fig. 144). Having stated the central motif of the Russian "village," Shekhtel freely interpreted the wooden structures of the other pavilions, with references to folk or traditional elements in both construction and decoration. The modernity of this interpretation appeared most striking in the agriculture pavilion; with its exaggerated contours and asymmetry, the building itself seems to have germinated (Fig. 145). The bulges and spires (which mask a conservative rectangular floor plan) can also be traced to some of the more inventive examples of wooden architecture in the far north: the roof tower over the central entrance of the side facade was decorated with a burst of arched forms and capped by a metallic "coxcomb," or crown, enclosing a large double-headed eagle in fretwork.

References to Russian traditional architecture on the smaller mining pavilion included the octagonal corner tower, reminiscent of the semidetached bell towers of large wooden churches (Fig. 146). The entrance porch veered toward parody with its enormous horseshoe- and barrel-shaped arches. Of all the pavilions, this one was closest in style to art nouveau. In contrast, the massive forestry pavilion incorporated ornament with greater restraint (Fig. 147). Apart from an entrance tower with a pyramidal roof and a few decorative bochka (barrel) gables, the exterior form of the building followed the interior plan. For the large panel that identified the pavilion Shekhtel designed a painted border of conifers and three gargantuan mushrooms, symbolizing the wealth of Russia's forests.

Indeed, all the pavilions displayed vivid polychrome in their carved and molded details and their facades. According to contemporary British accounts, the agricultural pavilion was painted "pale green and salmon," with red shingles, and the central pavilion was painted salmon, with brown shingles.[31] Three pavilions had plank siding; the forestry pavilion, however, was constructed of notched, unplaned logs assembled in the time-honored Russian fashion by the peasant carpenters. This log pavilion (painted light brown) gave exhibit visitors a firsthand look at the ingenuity and artistry of Russian wooden architecture.

The mining and agricultural pavilions used minerals and plant forms for decorative effects more modestly than the forestry pavilion used its logs, though these other pavilions had caps of brilliant sheet metal (gilded zinc, aluminum) on their towers and on many of their pitched roofs. The entire project took seven months to complete and required four supervisory visits from Shekhtel.[32] Although the critical notices were mixed and the critics occasionally uninformed about the architect's identity, Shekhtel's work did not go unrecognized: the Royal Institute of British Architects made him an honorary member, and in Russia he attained the rank of Academician of Architecture.[33]

In addition, the Glasgow Exhibition must have given Shekhtel the opportunity to see the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Although Mackintosh was not chosen as one of the exhibition architects, Shekhtel surely knew of his work by 1901; and on his journeys to Glasgow

Fig. 144.

Central pavilion, Russian section, 1901 Glasgow Exhibition. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

Fig. 145.

Sketch of agricultural pavilion, Russian section, 1901 Glasgow Exhibition. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik

Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

Fig. 146.

Mining pavilion, Russian section, 1901 Glasgow Exhibition. Fedor Shekhtel.

Zodchii , 1902.

Fig. 147.

Forestry pavilion, Russian section, 1901 Glasgow Exhibition. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik

Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

he would probably have visited the recently completed Glasgow School of Art (1897–1899), Mackintosh's most notable building in that city. The effects of Shekhtel's acquaintance with Mackintosh's work soon appeared in Moscow: Mackintosh's furniture figured prominently in the exhibit "Architecture and Artistic Crafts of the New Style," co-organized by Shekhtel at the end of 1902; and Mackintosh's spirit pervaded the architecture and interior design of another of Shekhtel's modernist experiments—the house of Aleksandra Derozhinskaia.

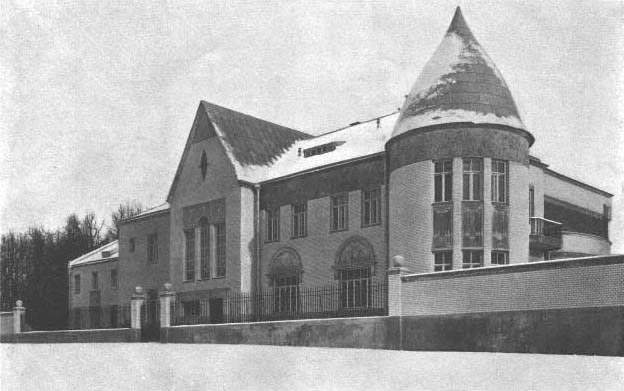

It is a mark of Shekhtel's diverse approach to the new style that the Riabushinskii and Derozhinskaia houses should appear to have so little in common, although the dates of their construction overlap. The Derozhinskaia house was built in 1901, while work on the interior of the Riabushinskii mansion apparently continued through 1902—a disproportion in construction times that reflects differing approaches to design: in the Riabushinskii house an elaborate display of the decorative arts and in the Derozhinskaia house a rejection of such decoration in favor of monumental mass and space (Fig. 148). Nonetheless, the Derozhinskaia house has carefully worked details, such as a wrought-iron railing (with a rotating triangle motif also used frequently for the interior design) and the glazed green brickwork of the facade, which in both houses is carefully integrated with the window transoms and the massive concrete cornice.

Here, instead of the ceramic frieze and capricious window designs of the Riabushinskii house, Shekhtel massed the structural elements and volumes at a central point with a minimum of decoration. The main window, which extends to the cornice line of the two-storied structure, indicates a proportional system for the house and, as it projects from the facade, serves as a triumphal arch. This central part of the house culminates in two concrete cylinders joined by ferroconcrete over a window strip that suggests, with perhaps unintended symbolism, the fortifications and gun emplacements of the machine age.

As at the Riabushinskii house, the plan evolves

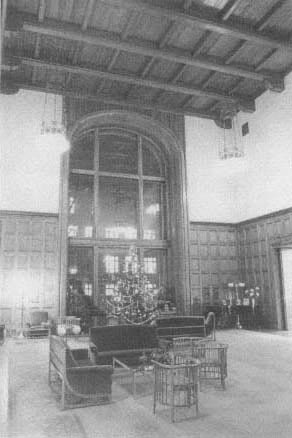

Fig. 148.

Derozhinskaia house, Moscow. 1901. Fedor Shekhtel.

Photograph ca. 1902.

around a structural core. For this purpose Shekhtel replaced the grand stairway of the earlier house with a two-storied main hall behind the center of the facade, creating one of the most heroic spaces in Russian domestic architecture of any period (Figs. 149, 150). (The hall measures 12.6 by 10.7 meters and is 11.2 meters high.) A Soviet specialist has described it as "the concluding chord of a heroic symphony in the spirit of Scriabin's Poem of Ecstasy ," and yet this room also shows exquisitely crafted details (see Plate 22).[34]

The vast hall and the wainscoting, of suitably heroic proportions, display the simplicity of the Scottish baronial style without the decorative extravagance that had marked Shekhtel's earlier work for the Morozovs. The fireplace, opposite the main window, is flanked by a male and a female torso in scagliola—melancholy captive figures that suggest the turmoil of the subconscious in Chekhov's final plays (Fig. 151). The fireplace mantel, with its panel of deeply incised trunks and foliage, resembles a similar motif on the corners of Olbrich's Secession Building, and the intricate lighting fixtures suspended from the ceiling are also similar to Olbrich's designs.

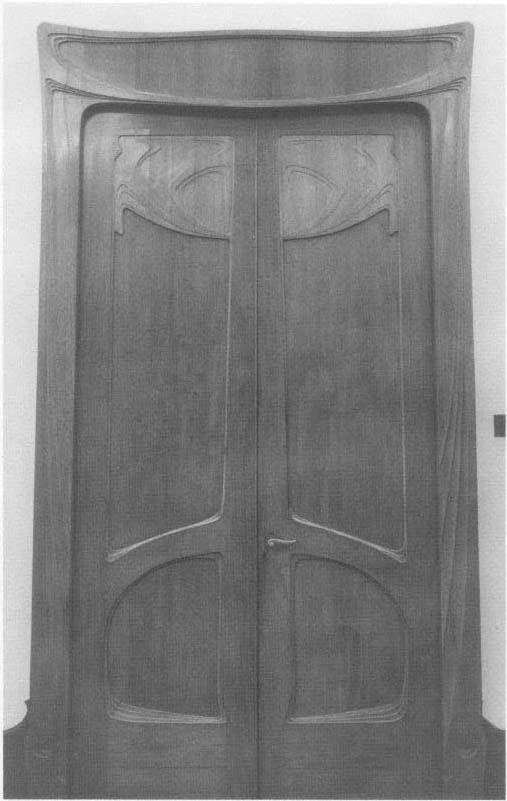

Similarities to Mackintosh's work emerge more clearly in other, smaller, rooms, where the integration of furniture and design becomes apparent (Figs. 152, 153). Like Mackintosh, Shekhtel took seriously the relation between the decorative arts and architecture; although the details of his furnishings for the Derozhinskaia house are not comparable to those of the Glasgow school, similar principles informed the work. The design and placement of furniture clarified architectural space rather than filled it. The colors and patterns of fabric and furniture—designed by Shekhtel—enhanced the architect's concept of the complete aesthetic environment (Figs. 154, 155).[35] Such a totality of vision required a large area so that the architect's furniture would not impede either the perception of ensemble and space or the use of the room. The Derozhinskaia mansion, unlike the Riabushinskii house, with its undistinguished furnishings, contained a series of comprehensively designed spaces (see Plate 23). The more compact design of the

Fig. 149.

Derozhinskaia house, main hall.

Photograph ca. 1902.

Fig. 150.

Derozhinskaia house, main hall (Brumfield M165-24).

Fig. 151.

Derozhinskaia house, main hall, fireplace (Brumfield

M165-37).

Fig. 152.

Derozhinskaia house, dining room.

Photograph ca. 1902.

Fig. 153.

Derozhinskaia house, master bedroom.

Photograph ca. 1902.

Fig. 154.

Derozhinskaia house, study.

Photograph ca. 1902.

Fig. 155.

Derozhinskaia house, door to library (Brumfield M166-6).

Fig. 156.

Derozhinskaia house, main stairway (Brumfield M165-19).

Fig. 157.

Derozhinskaia house, spiral stairway. (Brumfield

M165-28).

Riabushinskii rooms, arranged around the central stairway, did not encourage such a development; nor, paradoxically, did its exuberant decoration, which directed attention to the walls and ceiling.

From the smaller decorative details in brass, iron, fabric, wood, or wall painting to the major structural units, the houses display parallel ideas differently interpreted. In addition to its great hall, the Derozhinskaia house has a central staircase that unites the living areas around a central core. Although the carved oak stairway of this house contrasts with the plasticity of that in the Riabushinskii house, Shekhtel created a counterpart to the cascading effect of the Riabushinskii balustrade in the wave pattern of the carved balusters (Fig. 156). The large newel post to which the light fixture is attached repeats the wave as well as the tree motif that appears throughout the paneled interior of the house.

In all, the house has three staircases, each designed with attention to detail and each leading to separate groups of rooms (Fig. 157). In the main living quarters on the second floor, for example, an interior corridor links three of the rooms at the rear of the house, creating a private environment. The complexity of this plan—rumored to mirror the complex social relations of the inhabitants—tends to obscure the logic that operated so clearly in the houses for Zinaida Morozova and Stepan Riabushinskii. Yet Shekhtel created a new center in the great hall, whose five doors and magisterial proportions brought together the disparate elements of the house and provided an area suitable for entertainment on a grand scale.[36] So large, in fact, is the hall that it resembles public space in a domestic setting—not inappropriate, in view of Shekhtel's design, the following year, of the Iaroslavl Railway Station and the interior of the Moscow Art Theater.

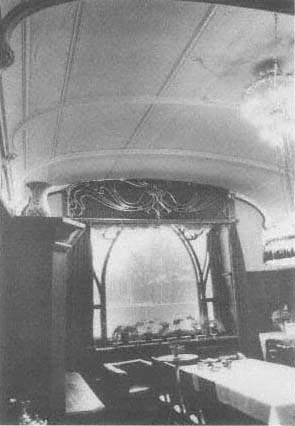

Like most of Shekhtel's sponsors, the Moscow Art Theater had connections with the city's merchant elite, not only through its director, Konstantin Stainslavskii,

but also in the person of Savva Morozov. After the success of The Sea Gull at its Moscow premiere, Morozov ensured the company's financial stability in 1899 by contributing large amounts of money and persuading other stockholders of this private company to do the same. With the further triumph of Chekhov's plays and other productions in the repertoire, the theater required a larger, more technically advanced space.

Shekhtel was the logical choice as architect. He was well known to Morozov, whose magnificent house he had designed; his recent accomplishments had established his reputation as an architect at the height of his creative powers; he had known and corresponded with Chekhov since the 1880s; he had demonstrated his own devotion to the theater from his apprenticeship in the 1880s to his design of people's theaters (see Fig. 128) at the turn of the century. Shekhtel also understood the complex technical requirements involved in building for a theatrical group dedicated to innovation and high production standards.

Shekhtel was able to accommodate a large revolving stage that represented the latest in technology and also provided a spacious support area for members of the company. In both endeavors he clearly had Morozov's active support. Stanislavskii noted in his memoirs that "Morozov spared no expenses for the stage and its paraphernalia, for the dressing rooms of the actors. . . . He lavished special love on the stage and its lighting."[37]

Shekhtel's accomplishment, however, is all the more remarkable in that he began with an existing structure. Morozov's generosity had its limits, and the most economical plan involved remodeling a building that dated back to the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was a private mansion. Subsequently rebuilt and expanded into an apartment house (1852), the structure was remodeled in 1880 as the Liazonov Theater according to a design by the architect Mikhail Chichagov, author of the Korsh Theater in the same neighborhood as well as several other theaters for the impresario Mikhail Lentovskii, with whom Shekhtel had worked as a young designer.[38] By keeping the foyer small, Shekhtel managed to increase seating to thirteen hundred and to install the large stage without substantially changing the walls of the previous theater.

Shekhtel's approach can be attributed to his limited budget (he refused to accept a fee for his own work at the theater); but his decorative scheme was also appropriate to the spirit of the Art Theater ensemble—from the patterned designs to the choice of color and material. Here a comparison with Mackintosh's work is especially apposite—with the interior of private homes such as Windyhill (1899–1901) and with public spaces such as the Buchanan Street Tea Room (1897–1898), for which Mackintosh designed murals.[39] Most prominent among the abstracted geometric patterns of the interior is Shekhtel's seagull design, which appears on the walls of the foyer and serves as the emblem of the Moscow Art Theater. The calculated effect of Shekhtel's designs in preparing the audience for the performances of the theater must be considered a significant innovation in his work. Rather than draw attention to the seating area, the design focuses attention on the stage through the sweeping contours of the balconies and the modernistic pattern of lines extending from the ceiling to the simple theater walls.

Stanislavskii's description of the interior reveals that he understood and appreciated this understated approach:

A high wooden panel with cloth in frames; above the panel portraits of great writers, poets, actors, and artists; along the panel wooden benches with cushions, white walls with a slightly dark border—that was the foyer, simple, modest, without one spot of color. The auditorium was finished in seasoned oak and the balustrades of the boxes and balconies, the furniture, the doors, the embrasures and panels were made of the same wood. The walls were also white, with hardly noticeable borders, without any bright spots or gilding. All the other rooms for the use of the audience were finished in the same style. This was done so as not to tire those sitting in the auditorium and to save all the color spots and effects for the stage.[40]

(This description suggests a similarity between Shekhtel's work at the theater and his restrained interior design at the Derozhinskaia house.)

Although a lack of funds after the completion of the interior prevented the rebuilding of the facade specified by Shekhtel (Fig. 158), the details of the windows and doors and the wrought-iron lanterns and brackets show his usual care and mastery. The lantern design has itself become a symbol of the theater. In addition, Anna Golubkina's stucco relief The Wave billows over and around the entrance on the right side (each of the three doorways—left, center, and right—is protected by a simple glass and iron awning). The fragments of the human torso and faces emerging from the chaos symbolize captivity and struggle in a more dynamic form than

Fig. 158.

Moscow Art Theater. 1902. Fedor Shekhtel (Brumfield M171-19).

does the sculpted mantel of the Deroshinskaia house (see Fig. 151). Ceramic facing at the entrance (from the Abramtsevo workshop) contains the rotating triangle motif used throughout the Derozhinskaia house (see Plate 24).

The psychoanalytic connotations of The Wave are appropriate for a company whose critical reputation was founded on its interpretation of Chekhov's and Ibsen's plays. Moreover, the exterior lantern brackets and the decorative strip along the top of the foyer walls echo the wave motif, as does the decorative line pattern over the proscenium. Indeed, that pattern suggests another elemental force related to developments at the turn of the century that affected the theater itself. In describing Morozov's efforts on behalf of the ensemble, Stanislavskii noted that Morozov was fascinated with electrical lighting—to the point of turning parts of the magnificent house Shekhtel had built for him into an electrical workshop.[41] As a result, the Moscow Art Theater was at the forefront in using electric stage lighting, and Shekhtel's design of the light fixtures for the theater reflects his interest in the electric lamp as a modern art form. Within this context the linear geometric patterns leading to the stage from both the ceiling and the walls suggest not only a surging but also a conduit of energy hovering over the proscenium.

Shekhtel's other major project of 1902, the Iaroslavl Railway Station, shows little of the abstract, modern style of design characteristic of the Derozhinskaia house and the Moscow Art Theater. The building is linked, however, to the Russian pavilions at Glasgow, both in form and in decoration. The station, like the theater project, involved rebuilding an existing structure, in this instance the terminus of the Moscow-Iaroslavl Railway (1859–1862), designed by Roman Kuzmin. The occasion for expanding an existing station was the extension of the Iaroslavl line to Arkhangelsk and the acquisition of virtually every other major northeastern rail line to form a vast, if sparsely developed, network that promised access to the region's great natural resources.

The architect of this capitalist venture was Savva Mamontov, whose community at Abramtsevo had such far-reaching ramifications for Russian art and architecture. By the time Shekhtel began work on the station, Mamontov no longer controlled the railway, for his attempt to extricate himself from financial difficulties had led to economic collapse and to his arrest in September 1899 on charges of illegal financial transactions.[42] His acquittal in 1900 did not restore his fortune; but the railway network he had created retained its importance, and the Moscow-Iaroslavl line, the route north, required a suitably imposing terminal at Moscow's major concentration of stations on Kanchalevskii Square.

Although Shekhtel had never worked with Mamontov, he was well prepared for this major commission by his work at home and abroad. Indeed, the work abroad may have significantly influenced the project: Shekhtel's Glasgow pavilions, with their wooden architectural forms of the far north, anticipated the Russian motifs re-created in masonry at the Iaroslavl Station (Fig. 159).[43] The roof tower with its decorative crown over the main entrance closely resembles the entrance of the agricultural pavilion at Glasgow, as do the station's plasticity of form and its polychromatic building materials (wood, brick, and tiles) and ornamentation (see Plate 25).

Shekhtel's "neo-Russian" architectural style can be related to wooden prototypes, but the towers at each corner of the station are modeled more directly on brick kremlin and monastery walls, as is evident from the machicolation of the right corner tower. Both Moscow and Iaroslavl, key points in this railway network, are rich in such forms, and Shekhtel's free interpretation of them evokes the picturesque asymmetry of medieval architecture (Fig. 160). A brief report in the first issue of Zodchii for 1905 referred to the symbolism of the recently completed station and its decorative elements:

This railroad, connecting Moscow with the north of Russia, itself determined the style of the facade; a northern Russian character was considered most appropriate for the new reconstruction. The larger part of the facade is faced in gray brick. Under the main tower is a relief portraying St. George the Dragon Slayer, the Archangel Michael, and a bear with a poleax—the emblems of Moscow, Arkhangelsk, and Iaroslavl. All other decorations are of colored majolica tiles prepared according to designs by Academician F. O. Shekhtel at the Abramtsevo workshop of S. I. Mamontov. The left corner tower contains a water cistern. In the main waiting room on the level of the frieze there will be panels by the artist K. A. Korovin that portray scenes of the northern region.[44]

In homage to Savva Mamontov, this account notes Shekhtel's use of the Abramtsevo workshop for the ceramic tiles used in the green and brown frieze along the main facade and in ceramic panels beneath windows on the main and side facades (see Plate 26). Both the frieze and the gray brick facade merge into the massive towers on either side of the main entrance, at which point the decorative possibilities of ceramic, stucco, and iron are explored with careful attention to texture and symbolism. Although some of the decoration was changed in a postwar renovation of the building (the stucco emblems of the cities above the main entrance were substantially modified), the polychrome tiles and much of the stucco work remain as Shekhtel designed them.

Shekhtel's most playful facade ornaments are the floral motifs in plaster and ceramic, such as the wild strawberries in the ceramic frieze flanking the entrance (Fig. 161), and the stylized folk-art conifer pattern on the left tower. These elements, like the mushrooms painted on the forestry pavilion at Glasgow, symbolize the richness and beauty of the northern forests. Northern fauna—wolves, polar bears, cormorants spearing fish, and reindeer—are also used ornamentally. In re-creating these animal forms in white stucco, Shekhtel appears to have borrowed from Konstantin Korovin's Pavilion of the Far North (see Fig. 45) at the 1896 Nizhni Novgorod exposition, on which polar bears and reindeer are represented in white stucco and wood. The white stucco suggests the snowy northern landscape, but some of the representations also allude to the intricate bone carving of native artisans. In the Korovin pavilion this allusion is particularly evident in the reindeer pattern of the porch railing; in the Iaroslavl Station it reappears in the antler motif on the side towers.

Korovin in fact provided the painted panels for the decorative frieze inside the station, which were originally displayed in the Pavilion of the Far North, supported by Savva Mamontov (an enlightened expression of his interests in that region).[45] Thus all roads ultimately return to Abramtsevo: to its workshops; its artists, who contributed so much to the new art and architecture at the turn of the century; and its patron, who,

Fig. 159.

Sketch for Iaroslavl Railway Station, Moscow. 1902. Fedor Shekhtel. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1906.

Fig. 160.

Iaroslavl Railway Station, left tower (Brumfield M101-10).

Fig. 161.

Iaroslavl Railway Station, main entrance, detail (Brumfield M101-3).

after losing his fortune, continued to participate in the Abramtsevo crafts movement.

The spirit of Abramtsevo that suffuses this station and other projects in the same style, however, is most truly represented by Viktor Vasnetsov, whom Shekhtel called his teacher in a letter written during the early stages of work on the Iaroslavl Station.[46] It is fitting that Vasnetsov should have been involved in a major architectural project of his own in Moscow at the beginning of the century Indeed, the Tretiakov Gallery and the Iaroslavl Station have much in common: both projects involved rebuilding an existing structure, both reinterpreted traditional Russian architecture and ornamentation (including the iconographic motif of St. George and the Dragon), and both used brick and ceramic tiles extensively for aesthetic as well as structural purposes.

Shekhtel turned to a different culture for one component of the station's main entrance. Travelers struggling with bundles and bags are unlikely to notice the great arched beams supporting the curved gable between the two entrance towers, but they play a significant part in shaping the central archway. Although at first glance they might resemble forms in traditional wooden structures, no exposed curved beams function as major supports in such Russian buildings. They do, however, serve this function in Japanese temple and palace architecture, in the traditional "rainbow" beam (koryo ) in early Buddhist temples and in the so-called Chinese gate (Karamon ) to the courtyard of Japanese feudal palaces.[47] The similarity of the Chinese gable (Karahafu ) to the arched gable of the Iaroslavl Station is all the more appropriate in that both define the major point of entry.

Such references to Japanese design were common in Europe at the turn of the century, especially in interior furnishings. Mackintosh used Japanese elements in his Glasgow School of Art as well as exposed beam-and-bracket systems that suggest Japanese provenance.[48] European exhibits of Japanese art and Russia's own expanding contacts with its Far Eastern neighbor and rival would have introduced Russian architects to these motifs. This stylistic connection extends to the main windows of the Iaroslavl Station, whose lattice grid is like that of the sliding screens (shoji ) of Japanese domestic architecture.

Unfortunately, virtually nothing remains of Shekhtel's design for the main vestibule. Photographs of the period show an open, functional space, brightly illuminated and modestly decorated with Korovin's panels, simple oak wainscoting a tile floor, and suspended light fixtures in the modern style.[49] In its general impression the interior suggests contemporary work by Josef Hoffmann, who enjoyed a considerable reputation in Russia and whose interior designs were illustrated in the Russian architectural press. Shekhtel, too, emphasized both decorative and functional components in developing a new aesthetic for commercial and public space; his main hall at the Iaroslavl Station resembles the interiors of his office buildings in Moscow after 1900.

The station was criticized as "facade architecture" (the same could be said of the Tretiakov Gallery). Zodchii , for example, misleadingly implied that Shekhtel could not be considered the author of the structure, since the old plan—with the exception of the vestibule—had remained intact during the construction of the main facade.[50] Whatever the technical validity of this claim, it overlooks the new space and new sense of structure created by merging international modernism and "neo-Russian" fantasy in the facade.

Fantasy, however, had little part in Shekhtel's urban, commercial architecture after 1900. His 1901 building for the Moscow Insurance Society on Old Square (behind the Kitai-Gorod wall) represents a turning point in his approach, a shift from Renaissance decoration in a facade dominated by the arch to an orthogonal grid framework (Fig. 162). Although the Insurance Society building—more commonly known as Boiars' Court, after the hotel located in it—uses familiar decorative devices from his previous buildings, rationalism predominates in its design.

The great horizontal sweep of the building, segmented by the verticals of narrow brick piers, suggests the Chicago school (the Carson Pirie Scott department store by Sullivan, for example), though without its technical innovations in structure. Despite the emphasis on the grid, skeletal construction was virtually unknown in Moscow before the revolution, and Shekhtel relied here—as throughout the decade—on construction with brick piers and reinforced concrete.[51] The piers are surfaced with green glazed bricks; the horizontal elements are yellow stucco.

In his later work Shekhtel largely avoided ornamenting his rational designs. Here, however, the massive Kitai-Gorod wall, parallel to the facade of Shekhtel's building, obscured the view of the lower three floors from the Old Square.[52] In this context the decoration and narrow window segments of the two upper floors provided a counterpoint to the crenellated wall, as did Shekhtel's central tower with attic (in the Secession style) that marked the main entrance and was paired with one of the ancient bastions. Now that the wall no longer exists, the entire building—its considerable length, the ground-floor arcade, the balconies, and the stuccowork—can be seen as a transitional episode in Shekhtel's movement toward a more functional interpretation of the style moderne.

The next step occurred in 1903 with the rebuilding of the Riabushinskii Brothers Bank, in the center of Moscow's financial district on Karuninskii Square (one block from the Upper Trading Rows). Pavel, Mikhail, and Vladimir Riabushinkii established the bank in 1901 to increase and diversify the income from their textile factories, and over the next decade they expanded banking operations to over a dozen cities. In redesigning the existing structure as the headquarters of the Riabushinskii financial concern, Shekhtel applied his usual construction technique, brick and reinforced concrete.

The result, however, is a radical departure from the Levenson Printing works or the Boiars' Court. In his commercial architecture Shekhtel had used plate glass in a masonry grid, but here the new structural methods are expressed without the ornament or tectonic illusionism of the ground-floor arcade of Boiars' Court or the heavy stonework of the Kuznetsov store.[53] The vertical and horizontal lines of the bank building define a precise four-storied grid of glass and brick, above which is a fifth story with narrow windows and a smooth stucco surface (Fig. 163). The only decorative concession, apart from modest garlands above the brick piers,

Fig. 162.

Moscow Insurance Society building (Boiars' Court).

1901. Fedor Shekhtel (Brumfield M-43).