11. Battles over Preemption

The combined effects of existing local tobacco control ordinances and Proposition 99's resources for educating the public about the dangers of secondhand smoke dramatically accelerated the rate at which clean indoor air and other tobacco control ordinances were passing at the local level. By 1994, one or two local ordinances were passing every week in California, and the pace of activity was accelerating. The efforts to pass ordinances had raised public awareness about the health dangers of passive smoking, and the issue of clean indoor air was mobilizing the general public to support a broader tobacco control agenda.[1] As a result of this activity, by 1993, nearly two-thirds of California's workers were protected by local laws mandating entirely smoke-free workplaces, and more than four-fifths (87 percent) were subject to some restrictions on workplace smoking.[2-5] Not only did this trend lead to ordinances and other tobacco control policies that protected nonsmokers from secondhand smoke, but the very battle for these protections engaged the community in a way that undercut the social support network for tobacco use that the tobacco industry had spent decades and billions of dollars building.

The tobacco industry viewed this development with great alarm. As early as January 11, 1991, in its plan entitled California: A Multifaceted Plan to Address the Negative Environment, the Tobacco Institute's State Activities Division set as one of its long-term strategies “Adopt a reasonable statewide smoking law, with preemption.”[6] Preemption is the

In the early 1990s there were three major battles over preemption in California: in 1991 with Senate Bill 376 and in 1993 with Assembly Bills 13 and 996. SB 376 was the tobacco industry's first attempt to get the Legislature to pass a preemptive state bill. Tobacco control advocates stopped it. In 1993 Assembly Member Terry Friedman (D-Santa Monica), a friend of public health, introduced a smoke-free workplace law as AB 13; while generally acceptable to health groups, it included preemption of local clean indoor air ordinances.[8] The tobacco industry responded with a competing weak bill, AB 996. Despite divisions in the public health community on the wisdom of AB 13, it eventually passed. At the same time, the public health community stopped the tobacco industry's AB 996. Motivated by the accelerating pace of local ordinance activity and the possibility that AB 13 would pass, Philip Morris, followed reluctantly by the rest of the tobacco industry, tried to overturn all of California's local (and state) tobacco control ordinances with a statewide voter initiative, Proposition 188, masquerading as an anti-smoking measure. The public health community put its differences over AB 13 aside, unified, and defeated Philip Morris and the other tobacco companies at the polls.

SB 376: The First Threat of Preemption

The tobacco industry recognized that it had a serious problem in California because the advocates of local tobacco control were well aware of the industry's strategy of preemption, and they were watching the Legislature carefully. To get advice on how to deal with this problem, Philip Morris flew Assembly Speaker Willie Brown and several other legislators (and their escorts) to New York for a secret meeting in November 1990.[9-11] Brown suggested a three-part strategy. First, the proposed legislation should preempt local tobacco control efforts. Second, since tobacco

The speaker's approach was spelled out in a June 28, 1991, memo from Michael Kerrigan, the head of the Smokeless Tobacco Council (the Tobacco Institute's counterpart for spit tobacco), to his management committee summarizing his conference call with representatives of Philip Morris, RJ Reynolds, the Tobacco Institute, and their lawyers and lobbyists to discuss a proposed Comprehensive Tobacco Control Act in California:

Kurt opened the call stating the purpose was to have a dialogue on policy questions that have arisen from the Philip Morris/Reynolds approach to seek preemption of public smoking restrictions within the state of California. Kurt positioned this issue by stating the 45 local battles that the T.I. [Tobacco Institute] is fighting concerning smoking restrictions in California, and that they have dealt with them by compromise, not by killing them. Therefore, he was trying to establish the need for preemption of smoking restrictions in the state of California and position, at least his concurrence, with the need for a preemptive strike in the state legislature… .

Joe Lange reported on “where they are” and stated that while there were some technicalities still open for discussion, he had done a great deal of work on this matter. He stated Speaker [Willie] Brown and Assemblyman [Dick] Floyd visited a cigarette company in New York City last fall and met with the key executives of that company. At that time the Speaker made clear a significantly more proactive tobacco control effort would be needed to secure preemption. Out of those discussions the notion of a comprehensive Tobacco Control Act (that would provide preemption) evolved. In order to gain preemption, the Speaker wanted “a Comprehensive Tobacco Control Act along the lines of the alcohol model.” The Speaker believes the trick to doing this would be that such an act would have to have the “appearance” of a comprehensive scheme. Joe stated that leadership in both chambers are aware of and support this effort. Joe stated that the chances for success, in his judgment are very good because the key players have all been involved. However, the chances of success depended upon the “perception” that the act was comprehensive. …

The conversation shifted to Joe stating Speaker Brown and Chairman Floyd would attempt to make the Tobacco Control Act as close as possible in “appearance” to the concepts that the anti-tobacco groups were fostering. Amazingly, that shuddering thought had no discussion.[9] [emphasis added]

Whatever the Smokeless Tobacco Council ultimately decided about Brown's proposal, it is clear that the cigarette companies worked to implement it. On July 11 SB 376 was amended to propose weak preemptive

The industry's effort was derailed when the Smokeless Tobacco Council memo appeared mysteriously at the offices of the voluntary health agencies and several media outlets. The resulting storm of media criticism killed SB 376.[12-14]

The Voluntary Health Agencies Accept Preemption

In February 1992 Assembly Member Terry Friedman (D-Santa Monica), one of only 8 legislators (out of 120) who refused to take tobacco industry campaign contributions and a supporter of tobacco control efforts in the Legislature,[15] introduced AB 2667, a nonpreemptive statewide clean indoor air law that would have ended smoking in all enclosed workplaces. Friedman promoted the bill as an alternative to local tobacco control ordinances.[16] Because AB 2667 dealt with labor law, Friedman designated as the enforcement agency the California Occupational Safety and Health Administration (CalOSHA) in the state Department of Industrial Relations instead of the Department of Health Services (DHS). The voluntary health agencies—American Lung Association (ALA), American Heart Association (AHA), and American Cancer Society (ACS)—supported AB 2667, as did the California Medical Association (CMA) and the California Labor Federation (AFL-CIO).[17][18] Despite its lack of enthusiasm for state legislation on clean indoor air issues, Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR) also supported Friedman's efforts as long as his bill did not contain language that preempted local ordinances.[19][20]

Despite support for AB 2667, it had only a very slim chance of passing because the hospitality and tourism industries, not simply the tobacco industry, were unlikely to allow the bill to go forward.[21] Because the odds against the bill were so great, neither the state voluntary health agencies nor ANR saw any practical reason to engage in broad discussions over the desirability of a state law versus local ordinances or the conditions under which preemption of local ordinances would be an acceptable compromise to obtain a state smoke-free workplace law.

The prospect of enacting statewide workplace smoking legislation improved dramatically when Friedman negotiated support for his bill from the California Restaurant Association (CRA). The CRA was concerned

Because of the CRA's concerns about secondhand smoke, the organization was open to endorsing the Friedman bill. But it was unwilling to do so unless the CRA goal of a uniform statewide law was also met, and it made its support contingent on inclusion of preemption of local ordinances.[25] Friedman amended AB 2667 to include a preemption provision that would “supersede and render unnecessary the local enactment or enforcement of local ordinances regulating the smoking of tobacco products in enclosed places of employment.”[26] The CRA immediately endorsed the amended bill.[25] This was the first time an important business lobby in Sacramento had supported tobacco control legislation; the coalition of health groups supporting AB 2667 were ecstatic.[27][28]

By continuing to support AB 2667 after it was amended to include preemption, however, the state voluntary health agencies adopted a position that conflicted with their national organizations' policies against preemption. In 1989, in response to preemptive legislation that had been proposed by the tobacco industry and enacted in a growing number of states, the national voluntary health agencies, acting through the Coalition on Smoking OR Health, took a strong anti-preemption position.[29] It advised affiliates that “it is better to have no law than one that eliminates a local government body's authority to act to protect the public health” and suggested informing the appropriate legislator that “unless the preemption is removed from the bill…your organization can no longer support the bill.”[29] Despite this national policy, the state voluntary health agencies and Friedman defended the preemption language by arguing that because the bill would make all workplaces 100 percent smoke free, any local standard would be weaker, making the preemption issue moot.[30-32]

ANR representatives, on behalf of many local tobacco control advocates, did not accept this compromise. They believed that local legislation was a better device to educate the public, generate media coverage, and build community support for enforcement and implementation of tobacco control ordinances.[33] ANR also believed that any preemption

Trying to allay these concerns, Friedman modified the severability clause in the bill to limit preemption if the bill was weakened: “In the event this section is repealed or modified by subsequent legislative or judicial action so that the (100 percent) smoking prohibition is no longer applicable to all enclosed places of employment in California, local governments shall have the full right and authority to enact and enforce restrictions on the smoking of tobacco products in enclosed places of employment within their jurisdictions, including a complete prohibition of smoking.”[26] Friedman and the bill's supporters argued that this language would protect local ordinances because the preemption clause would “self-destruct” if future legislation weakened the smoke-free mandate.[30][36]

Friedman's attempt at compromise fell short, however, when in April he solicited an analysis from the Legislative Counsel regarding the severability clause. The Legislative Counsel concluded that the severability clause offered no legal protection because the current session of the Legislature had no authority to bind future sessions of the Legislature.[37] Nevertheless, the state voluntary health agencies continued to support the bill because of its 100 percent smoke-free workplace mandate.

Even with the support of the restaurants, labor groups, and voluntary health agencies, AB 2667 failed to pass the Labor and Employment Committee in June 1992.

The Birth of AB 13

Friedman reintroduced AB 2667 as AB 13 in the next legislative session in December 1992, and it was assigned to Friedman's Labor and Employment Committee in February 1993. The bill was cosponsored by the CRA, AHA, AFL-CIO, and CMA.[38] The AHA, ALA, and ACS supported the bill because they wanted smoke-free workplaces. Groups

These differences of opinion still appeared moot. Despite the broadened support for the bill, it was still viewed as unlikely to pass. AHA lobbyist Dian Kiser wrote her local affiliates, “Frankly, the chance of passage of AB 13, like AB 2667, is minuscule.”[21] Rather than treating preemption as a policy issue, supporters of the bill fell back on the argument that since AB 13 was “100 percent smoke free,” the issue of preemption was not important.

AB 13, unlike AB 2667, passed out of the Labor and Education Committee. Newspapers credited AB 13's passage out of committee to a 1992 EPA report on secondhand smoke as well as Governor Pete Wilson's decision in early 1993 to end smoking in all state government buildings.[39][45]

At the first hearing of the Ways and Means Committee, Friedman added two amendments in a continuing effort to respond to concerns about preemption and enforcement. The first clarified the severability clause to insure that, if AB 13's smoke-free mandate were weakened, communities could pass and enforce future ordinances as well as enforce existing ordinances. The other was his amendment to allow local governments to designate a local agency to enforce the law rather than specifying local police.[46] While AB 13 was being considered by the Ways and Means Committee, the League of California Cities, which had remained neutral on AB 2667, changed its position and announced support for AB 13 on the grounds that the bill would allow local governments to pass restrictions on tobacco in areas not covered by the bill.[47]

The Tobacco Industry's Response: AB 996

The tobacco industry pursued three major strategies to counter AB 13. First, working through its front groups (including the Southern California Business Association) and the California Manufacturers Association

On April 19, 1993, Assembly Member Curtis Tucker (D-Inglewood) amended an unrelated bill, AB 996, to preempt all future tobacco control laws. AB 996 permitted smoking in workplaces when employers met the ventilation standard defined by Standard 62-1989 of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), although the ASHRAE standard stated that it was not strict enough to protect workers from secondhand smoke.[49] The use of the ASHRAE standard, while sounding official, was already incorporated into most building codes in the state and would have had little effect on restricting smoking in the workplace. The tobacco industry has heavily influenced ASHRAE over the years.[50]

The tobacco industry also used AB 996 to preempt emerging local ordinances restricting youth access to cigarette vending machines. Rather than eliminating vending machines as health advocates wanted, AB 996 proposed electronic locking devices that had proven ineffective in controlling youth access.[51][52] AB 996 was assigned to the Assembly Committee on Governmental Organization, chaired by Tucker, where it passed by a 9-0 vote. The bill was then referred to the Assembly Committee on Ways and Means, where AB 13 was also being considered.

AB 996 was supported by the tobacco industry and its allies in the business community; it was opposed by the same coalition of health, local government, and business groups that supported AB 13 in addition to those who opposed AB 13 because of its preemption clause.[53] The CRA opposed AB 996 because, in protecting current local clean indoor air laws with a grandfather clause, it would not lead to a uniform smoking policy around the state. The CRA also feared that it would not protect restaurant owners from lawsuits and that the ASHRAE ventilation standards would be prohibitively expensive for small restaurants.[22]

The introduction of AB 996 changed the debate over state smoking restrictions. Prior to AB 996's emergence as a competing bill to AB 13, media coverage of AB 13 included the debate among tobacco control advocates over the merits of AB 13, particularly ANR's concern with preemption. When AB 996 started moving in tandem with AB 13, media coverage

The View from outside Sacramento

The potential effect of AB 13's preemption provisions on local ordinances created controversy and confusion among local tobacco control advocates over whether to support the measure. Local coalitions, composed of people from local affiliates of the voluntary health agencies, local medical associations, departments of health, and individual activists, received inconsistent information on the state debate over AB 13 and AB 996. While opposition to AB 996 was unanimous, the state voluntary health agencies urged support of AB 13 while ANR continued to urge opposition. Many individuals who participated in these local coalitions were members of both a voluntary health agency and ANR, and so were receiving conflicting action alerts from different organizations.

Some activists at the local level questioned the effect of AB 13 on local legislation and remained skeptical that a workable bill would emerge from the Legislature.[33][56] Of special concern was how the preemption language would affect nonworkplace provisions of local ordinances (such as those mandating public education) or nonretaliation clauses (which would protect employees who complained about noncompliance with the smoke-free workplace requirement). Questions from those communities about AB 13 were interpreted by lobbyists at ALA and ACS as efforts by ANR to undermine their authority, and they complained of having to devote time and resources to respond to what they perceived as ANR's misinterpretation of the bill.[27][31] ANR saw its activities as a legitimate way to present its opposition to preemption to the people most affected.[19]

As controversy over the bill intensified and communication broke down between state players, a hostile exchange occurred, with local activists caught in the cross fire. One LLA director later described the atmosphere: “Oh my God. We were on the record of telling our coalition that it was preemptive and that it was not a good thing. And because we had had these conversations, some individuals wrote letters. I got nasty

AB 13 and AB 996 on the Assembly Floor

AB 13 and AB 996 were considered in tandem by the Assembly Ways and Means Committee. Although contradictory in intent and effect, both bills passed the committee, with several members voting for both bills. The bills next moved to the Assembly floor, where AB 13 was amended on May 24, 1993, to exclude hotel guest rooms from AB 13's definition of “place of employment.” Since AB 13 preempted only local regulation of “places of employment,” local governments would be permitted to regulate hotel guest rooms.

Both AB 996 and AB 13 came to a floor vote in the Assembly on June 1, 1993, and both failed. Just days later, AB 996 was taken up again, while reconsideration for AB 13 was delayed until the following week by a technicality. The tobacco industry's bill, AB 996, passed by a 42-34 vote. The Assembly members who voted for AB 996 had received a total of $964,740 (average $22,970 per “yes” vote) in tobacco industry campaign contributions during the years 1975-1993, compared with only $193,567 for opponents (average $5,693 per “no” vote).[15] Newspapers reported that campaign contributions from tobacco interests to legislators were buying votes against AB 13 and for AB 996.[59][58][59] Friedman denounced passage of AB 996 as “an example of the absolutely disgusting power the tobacco industry wields in the Legislature.”[60]

In the debates over local tobacco control ordinances, it had become routine for the tobacco industry, acting through surrogates, to claim that smoking restrictions would cause economic problems. On June 6, the day after AB 996 passed the Assembly but before AB 13 was reconsidered, several Southern California “business” groups, led by the Southern California Business Association, a group with tobacco industry connections,

The CRA immediately hired another accounting firm, Coopers and Lybrand, to review the Price Waterhouse report. Coopers and Lybrand said the Price Waterhouse results were biased because the respondents had no previous experience with a statewide smoke-free law, so their impressions would not accurately reflect potential business loss.[64] The survey also produced bias in its results by giving respondents misleading information regarding the scope of areas affected by AB 13. Coopers and Lybrand noted that Price Waterhouse omitted “a key conclusion, if not the key conclusion, that over 61% of respondents thought that there would be no impact or positive impact on sales from the proposed ban.”[64] This prompt response by the CRA neutralized the effects of the Price Waterhouse study.

AB 13 was granted reconsideration on June 7 and passed the Assembly with a 47-25 vote. Members who voted for AB 13 had received $363,823 in campaign contributions from the tobacco industry between 1976 and 1993 (average $7,741 per “yes” vote), and those who voted against it, $711,405 (average $28,456 per “no” vote).[15] Friedman hailed his success as a “spectacular turnaround,” attributing the change in votes to “the outpouring of spontaneous public support for AB 13 all over the state, and the outrage expressed by the voters at the passage of the industry-sponsored measure.”[65] Several members of the Assembly expressed discontent with both AB 13 and AB 996, saying one bill was too strict and the other was not strict enough, and voiced the hope that a compromise bill could be created in the state Senate or in a conference committee.[66]

On to the Senate

In the Senate, AB 13 and AB 996 were assigned to both the Senate Health and Human Services Committee and the Judiciary Committee. AB 996 died in the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, chaired by Senator Diane Watson (D-Los Angeles), as a result of effective lobbying by tobacco control advocates and senators friendly to tobacco control.

AB 13 passed the Senate Health and Human Services Committee on its second hearing after being further amended to exempt hotel and motel lobbies, bars and gaming clubs, and some convention centers and warehouses. Once again, these exemptions were created by excluding these venues from AB 13's definition of “places of employment.” Since AB 13 applied only to places defined as “places of employment,” these exemptions from the smoke-free mandate were also exempted from the bill's preemption clause, leaving them open to local regulation. Friedman admittedly accepted the amendments to exempt these areas so as to move the bill through committee; he declared the bill's passage to be a victory against the tobacco industry.[69]

The AB 13 coalition continued to support the bill, even though it was no longer “100 percent,” the rationale initially used by several members of the support coalition to justify their acceptance of the preemption language. Between the first and second committee hearings, in response to a question from a reporter, Friedman argued that “AB 13 creates one uniform protective statewide law and preempts the patchwork of local ordinances around the state with which businesses must currently comply. It protects all workers from environmental tobacco smoke and all employers from claims related to environmental tobacco smoke” (emphasis added).[70]

After passing the Health and Human Services Committee, AB 13 was referred to the Judiciary Committee, chaired by Senator Bill Lockyer (D-Hayward), the author of the “Napkin Deal” (see chapter 3). At AB 13's first hearing in the Judiciary Committee, on August 19, it was clear AB 13 did not have the votes to clear the committee.[67] Over the next several weeks, Lockyer proposed several amendments that would further weaken the bill's smoke-free mandate, including a request that Friedman relinquish his 100 percent smoke-free requirement in favor of ventilation standards. Rather than accepting Lockyer's proposal, Friedman petitioned to turn AB 13 into a two-year bill, allowing him to bring the bill back to committee for discussion in 1994. His request was granted and Friedman vowed to return in 1994 with a stronger support coalition for the bill.[71]

The Philip Morris Plan

Friedman was not the only one making plans for 1994. In November 1993, conceding that it would likely be unsuccessful at “blowing AB 996 out of Senate Health,”[68] Philip Morris started planning an initiative modeled on AB 996:

Simply filing [a proposed initiative] has some advantages because it may force the legislature to act in a way we can help channel (e.g.: if they believe a less onerous bill would pass on the ballot, we can give them the opportunity to pass something a little more restrictive, but less than a total ban, then not turn in any signatures). Conversely, if we believe we can win with something more moderate than the legislature might pass, we should turn in signatures and go to the ballot.[68]

Thus, the filing of an initiative might give the industry some leverage in the Legislature against AB 13. This strategy was similar to the one that the industry had traditionally used at the local level—the threat of a referendum to force counties and municipalities into more moderate ordinances (see chapter 9).

On November 1 David Laufer of Philip Morris laid out the California “situation.”[68] The San Francisco Board of Supervisors had just passed an ordinance similar to AB 13. According to Laufer, “It is no coincidence that the bill resembles AB 13, since Terry Friedman has spent the last several weeks in SF lobbying the Board.” He went on to say, “Barring a miracle or a decision to take this to the ballot, it is a done deal.” He noted that the smoke-free ordinance in Los Angeles had gone into effect and, “while perhaps not enforced,” was “being complied with on the whole.” He added that the Tobacco Institute “has no more funds this year to continue to pursue the case, so we will need to decide if we want to continue and pick up the tab.” In San Jose, the City Council had directed the city attorney to draft a law making all public places and worksites smoke free (which passed on December 30, 1993), and San Diego was discussing strengthening its ordinance. Sacramento had been smoke free for several years. Laufer offered this summary: “In 4 of the 5 largest population centers in the state, a ban is, or will likely be the reality, making AB 13 (a statewide ban) all the more appealing and easy to enact when session reconvenes in early January 1994. …In conjunction with whatever remaining allies we have, I believe we must launch a simultaneous counterattack on several different fronts: legislative, initiative, regulatory

On January 12, 1994, Merlo wrote to Geoff Bible, president of Philip Morris, to bring him up to date on “the steps that we will take in California over the next several weeks in order to achieve state-wide preemption with accommodation for smokers.”[73] California clearly warranted attention at the tobacco giant's highest levels. Four steps were outlined:

- We will file a lawsuit on February 1st against the City of San Francisco over the jurisdictional issue of whether or not San Francisco has the authority to ban workplace smoking. We will be a co-plaintiff along with local business people in this lawsuit and based on precedent and legal advice, we think we have an excellent chance of prevailing.

- At the state level, we will create “a flurry of legislative activity to confound the antis by introducing various bills and measures to put them on the defensive, including asking for an audit of the Proposition 99 trust fund, an investigation of political abuses of the Proposition 99 fund and a resolution to ask U.S. OSHA to establish Indoor Air Quality Standards within the state.

- We will create the same level of local activity in cities like Anaheim, South San Francisco, Stockton, Palm Desert, Rancho Mirage, etc. by introducing smoking accommodation bills.

- Finally, on or about January 17th, we will file a ballot initiative seeking a state preemption bill that provides for smoker accommodation. The Initiative will be filed by three independent business and/or association members. Simultaneous with our filing of the ballot initiative, we will conduct additional polling to ensure that we thoroughly probe voter reaction to this bill, which preliminary polling indicates we have a very good chance of winning.[73]

Merlo added that if the company had the “opportunity to reach a negotiated settlement through the Legislature for preemption and accommodation, we will do so.”[73]

RJ Reynolds did not share Merlo's optimism about an initiative. On January 17 Tim Hyde wrote to Tom Griscom and Roger Mozingo about the proposed initiative, saying, “Overall, I think this is a bad approach,” referring to a survey conducted for Philip Morris.[74] He offered the following arguments to support his view:

- A. I am doubtful we could prevail on such a ballot question. We haven't seen the whole survey, yet, but Q57 [the head-to-head comparison of AB 996 and AB 13], in the deck, shows that almost as many people would vote for a total ban as for designated areas (44-46%). And that's before the other side has had a chance to propagandize about out-of-state tobacco companies spending big money to protect their interests.

- B. There are tremendous down sides if we lose. It would establish the official position of the California electorate on this issue, making it much more difficult for legislators and local public officials to resist the anti's call for public bans. It would also have obvious national fallout.

- C. Even if we should win, it doesn't solve the problem. The real problem is the hundreds of millions that other side has in Prop. 99 money to fight us. I suspect that if they weren't spending their efforts trying to enact local ordinances, as they are now, they would be up to worse activities: such things as harassing private employers, even more egregious studies and pilot intervention programs, and who knows what else.

If we were going to mount a proactive initiative, why not one that would divert these funds to prison construction and emergency rooms? That has immediate public appeal, is a “get” for the voters, and would have precedential value for other states.

I also think we need to be careful with what the other side has identified as “front” organizations. A California chapter of the National Smokers' Alliance, for example, will be quickly seen as PM's grassroots arm. The group we have fostered—California Smokers' Rights—has 8,000 paid members and money of their own in the bank, but the [sic] are still frequently accused of being a front for the industry.

Finally, five million dollars is a lot of money.[75] [emphasis added]

RJ Reynolds was clearly not interested in an initiative battle over smoke-free workplace laws, preferring instead to try to kill off the Proposition 99 Health Education and Research Accounts once and for all. Local ordinances were causing problems for the industry, but the root cause of the problem was Proposition 99. Philip Morris ignored RJ Reynolds and continued with its initiative.

The Philip Morris Initiative

As Merlo had alerted Bible, on January 17 Philip Morris and a group of restaurant owners submitted an initiative statute, the California Uniform Tobacco Control Act (essentially identical to AB 996) to the California

The initiative would have overturned eighty-five local ordinances that mandated smoke-free workplaces and ninety-six ordinances that mandated smoke-free restaurants (as of January 1994). In addition, because strict workplace smoking restrictions encourage some smokers to quit and others to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked,[77] a trend that is reversed when restrictions are relaxed,[2][79] passage of the initiative would have actually increased smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke.[80] While Philip Morris's public statements did not emphasize the potential of the initiative to protect tobacco profits, the company explicitly presented the initiative as a way for tobacco retailers to protect their business: “The adverse impact on retail cigarette sales would be immediate [without the initiative]. Your cigarette sales, along with your profits, could drop.”[81]

Organized opposition to the initiative, which was eventually placed on the ballot as Proposition 188, developed slowly. When Philip Morris first proposed the initiative in January 1994, only Carolyn Martin, an ALA volunteer and former chair of the Coalition for a Healthy California and TEOC, and ALA lobbyist Tony Najera, expressed strong concern about it. Most people viewed the Philip Morris initiative as a sure failure because the California public had been educated about the health dangers of tobacco and did not trust the tobacco industry.[82][83]

Martin and Najera hired Jack Nicholl, who had been campaign manager for the Yes on Proposition 99 campaign. The three contacted former Coalition members to alert them to Philip Morris's actions and to mobilize local groups to publicly denounce the initiative as an attack on their local tobacco control ordinances, local autonomy, and public health and to contact editorial boards and secure their opposition. Martin also

Meanwhile, ACS funded a poll of California voters asking how would they vote if they knew Philip Morris was behind an initiative that would decrease smoking restrictions in California, overturn local laws, and prohibit cities and counties from making their own smoking laws.[86] This poll also tested various messages that could be used to oppose the initiative, so it provided important marketing research for the public health campaign. The results revealed that 70 percent of those polled would vote against such a law, 24 percent would vote for it, and 6 percent were undecided.

While the proponents of an initiative write the text of the proposed law, the California Attorney General provides the official title and summary, which appear on the ballot. This wording is important because it may be the only material that a voter reads about the measure before voting. The title and summary also appear at the top of all copies of the petitions used to gather signatures to qualify the initiative for the ballot. Given their experience in the Proposition 99 campaign, Martin and Najera realized the importance of not only the initiative's title and summary but also the Legislative Analyst's analysis and ballot arguments, which appear in the Voter Pamphlet. Philip Morris had submitted proposed language emphasizing that the initiative “bans smoking,” “restricts…vending machines and billboards,” and “increases penalties for tobacco sale to and purchase by minors” while downplaying the exceptions.[87] The Coalition hired an attorney who presented a title and summary to the Attorney General that emphasized preemption of local ordinances, relaxation of current restrictions on smoking, and the increase in smoking that the initiative would cause.[88][89] The final title and summary that the Attorney General released on March 9, 1994, reflected the Coalition's concerns; it highlighted the preemption of existing laws and significant exceptions to smoking restrictions.[90] The Coalition's timely and assertive intervention would prove very important as the battle over the initiative unfolded.

The Continuing Fight over AB 13

As he had promised in November 1993, Friedman was ready to push AB 13 when the Legislature returned in January of the following year.

AB 13 was continuing to move through the Legislature. When the Senate Judiciary Committee heard AB 13 again on March 22, two tobacco-friendly amendments were added to the bill.[92] The first, sponsored by Senator Art Torres (D-Los Angeles), extended the phase-in period and ventilation options for bars, gaming clubs, and convention centers to restaurants. The second amendment, sponsored by Senator Charles Calderon (D-Whittier), preempted all future ordinances. Calderon had a history of supporting such preemption language as well as the tobacco industry generally.[93] In proposing his preemption amendment to AB 13, Calderon argued that if Friedman truly wanted to establish a state standard for smoking, he should extend the preemption in the bill to all local ordinances. Friedman objected that his fragile support coalition would disintegrate because many supporters were philosophically opposed to preemption.[94] The Judiciary Committee ignored Friedman and passed the bill by a vote of 6-1, including the amendments.

Once AB 13 was amended to broadly preempt local laws, the health groups, which had been divided about the preemption in AB 13, united in opposing it. The League of California Cities, ACS, ALA, and AHA expressed opposition to the two pro-tobacco amendments and said they would oppose the bill until both amendments were removed.[95-98] ANR continued to oppose the bill.

The weakening of AB 13 was front-page news.[99] The Los Angeles Times editorial page called the hearing “a rape in Sacramento.”[100] Friedman lobbied to remove the Torres and Calderon amendments from AB 13 in the Senate Appropriations Committee, the last committee before the Senate floor.[101] Torres, realizing he had been misled at the hearing by restaurant owners in his district, worked with Friedman's office to remove the amendment he had suggested as well as Calderon's preemption language.[102] Friedman and his supporters successfully removed the hostile

The Philip Morris Signature Drive

The flurry of press activity surrounding AB 13 did not extend to the Proposition 188 signature drive. Philip Morris began a quiet effort to qualify its initiative, using the Dolphin Group (which had created front groups for fighting local ordinances) to run the campaign as Californians for Statewide Smoking Restrictions (CSSR). Voters began receiving phone calls inquiring whether they would support a uniform state law restricting smoking. Respondents who answered “yes” received a packet that contained advertising materials and a copy of the petition to be signed and returned. This attractive packet, which cloaked the initiative as a pro-health measure, detailed “strict regulations” that would be implemented by the proposed law and outlined its “benefits”:

- Completely prohibits smoking in restaurants and workplaces unless strict ventilation standards are met.

- Replaces the crazy patchwork quilt of 270 local ordinances with a single, tough, uniform statewide law.

- [Is] stricter than 90% of the local ordinances currently on the books.[103]

Using staff resources donated by ALA, the Coalition campaigned to keep Philip Morris from collecting enough signatures to qualify the initiative and sought resolutions from local governments that had already passed strong local tobacco control ordinances in an attempt to create debate and interest the press in covering the story. Even though the Coalition considered this strategy a long shot, any controversy created during the signature gathering might attract early press attention before the general election campaign.

The Coalition also advised voters who had signed the petition in the belief that it would promote health to complain to Acting Secretary of State Tony Miller.[104] On April 8 Miller sent a letter to the restaurant owners who had filed the petition, warning them that deceptive petitioning

On May 9 CSSR submitted 607,000 signatures (385,000 valid signatures were required) to the secretary of state's office. As part of his continuing investigation, Miller asked for court permission to randomly sample the signatures to survey for fraud. The court denied permission on the grounds that it would constitute invasion of privacy.[106] On June 30 the secretary of state certified that Philip Morris had collected enough valid signatures to place the initiative on the ballot for the November 1994 election as Proposition 188.

The Legislature Passes AB 13

Back in the Legislature, AB 13 was continuing to move. After passing the Senate Appropriations Committee, it was sent to the Senate floor. Senator Marian Bergeson (R-Newport Beach), AB 13's floor manager in the Senate, successfully fought off several hostile amendments. However, one amendment was accepted on June 16: smoking areas would be allowed in long-term patient care facilities and in businesses with fewer than five employees so long as all air from the smoking area was exhausted directly outside, the area was not accessible to minors, no work stations were situated within the smoking area, and EPA or CalOSHA ventilation standards were met, once established. The bill passed the Senate on June 30, 1994. The Assembly voted concurrence with the Senate amendments. Governor Wilson signed the bill into law on July 21, 1994.

The final version of AB 13 retained its 100 percent smoke-free mandate as well as its preemption clause. Amendments were worded so any exemption from the smoke-free mandate allowing smoking was also an exemption from the preemption clause. Thus, local entities would be allowed to enforce existing regulations and pass and enforce new regulations restricting smoking in areas exempted from AB 13, despite its preemption clause. Nevertheless, Governor Pete Wilson cited the bill's preemption of local ordinances as a reason to sign the bill into law. He stated that AB 13 protected California's businesses as well as the health of workers because “by providing a uniform, statewide standard which

Wilson continued to press his view that AB 13 preempted local communities from regulating smoking. In 1995 a nursing home resident in San Jose complained that he was being forced to breathe secondhand smoke in the television room at the nursing home; he asked the city, under its clean indoor air law, to require that the room be smoke free. The city complied, and DHS sued, claiming that AB 13 preempted the ordinance. DHS lost in the trial court and appealed. On August 18, 1998, the Sixth District of the Court of Appeal unanimously ruled that the neither federal law nor state law preempted localities from enacting local tobacco control ordinances:

By disavowing any intent to preempt the regulation of tobacco smoking, and by in fact expressly authorizing local agencies to “ban completely the smoking of tobacco” in any manner not inconsistent with the law, the Legislature clearly indicated its intent to leave to the local authorities the matter of regulating the smoking of tobacco in their respective jurisdictions, provided the regulations so adopted do not conflict with statutory law. In delegating such regulatory power to local agencies and expressing its preference that regulation of tobacco smoking at the local level be made by local governments, the Legislature impliedly [sic] decreed that where the local agencies have stepped in to regulate the smoking of tobacco within their own territorial boundaries, the state's administrative agencies, such as the Department [of Health Services] should step back… .

Evidently, the rationale for the Legislature's deference to local governments, equipped as they are with superior knowledge of local conditions, [is that they] are better able to handle local problems relating to regulation of tobacco smoking.[108]

The fact that DHS under the Wilson administration was willing to advocate the position that a nursing home resident had no right to a smoke-free environment while watching television was just one more example of the administration's pro-tobacco position. The result, however, was a resolution of the bitter debate within California's tobacco control community over whether or not state law was preemptive. It was not.

AB 13 and Proposition 188

For the tobacco industry, Proposition 188—which had started out as a way to finesse legislative behavior and get what the industry regarded as a good preemptive bill—had become essential after passage of AB 13. John M.

In June 1994, before AB 13 became law, the tobacco industry commissioned a public opinion poll on Proposition 188. The poll, conducted by Voter/Consumer Research of Houston, showed that the initiative was running even among voters (43 percent for, 43 percent against). Its supporters were primarily people who wanted to strengthen smoking restrictions, and opponents were primarily smokers, people who opposed government regulation, and people who disapproved of Philip Morris's sponsorship of the measure.[110] The poll also revealed that Proposition 188 faced two other problems. The first problem was that the initiative was confusing to people (especially with tobacco control advocates and the media attacking it), and confusion leads to “no” votes. The other problem was that the industry was asking for “yes” votes, which are historically harder to get.[110] As RJ Reynolds recognized, “Since the signing of AB 13, the effect of P[roposition] 188 would be to relax restrictions. In other words, the whole electorate will probably reconfigure on this issue.”[111] Those who wanted smoking restrictions would likely shift to support the new status quo, AB 13, which meant they became “no” votes, while those who opposed Philip Morris sponsorship would stay on “no.” Only smokers and opponents to regulation would stay where they were. The only hopeful news for the tobacco industry from the poll was that while Californians preferred smoking bans to nothing, they preferred restrictions to bans, and that while tobacco sponsorship was not a plus, it was not a killer.[111]

The Stealth Campaign

After the initiative qualified, CSSR avoided the media and public debates on the initiative and instead began an expensive direct mail advertising campaign to reach voters. Proposition 188 was promoted as a tobacco control law, a tough but reasonable alternative to AB 13. Although virtually all the money for Proposition 188 was coming from the tobacco industry (table 3), CSSR downplayed the industry's role in the campaign and, in typical fashion, presented itself as a coalition of small business owners, restaurants, and concerned California citizens.

Lee Stitzenberger of the Dolphin Group ran the campaign for Philip

It calls for no television, 15 m pieces of mail, the ol' slate-card extortion, earned media, some newspaper ads, and a couple of weeks of radio at the end. Basically, it is a kind of stealth campaign: much of it will fly under radar cover. The first phase of the campaign, between now and Labor Day, will hit the sponsorship head on. “If you think this is a ploy by the tobacco companies, read the proposal. Here it is. Read it.” The next phase will attempt to use allies, broaden the base with coalitions, and the use of spokespeople for earned media. The final phase will be targeted radio and the slates.

The primary message, other than “we don't have anything to hide,” will be that AB 13 goes too far, we need severe restrictions, not bans. The other side won't have any money, but they will have almost universal editorial support. The campaign will monitor their use of Prop 99 monies and is prepared to challenge any use thereof in court.

They [CSSR] have a $9 m budget for the remainder of the campaign. We guess PM has put about $1.5 [m] in so far. Ellen [Merlo] said that PM has budgeted $6 m, so they are looking for $3 [m] from the rest of the industry. In addition, National Smoker Alliance will do two statewide smoker mailing [s] (which, of course, PM will pay for)… .

What they want from the rest of the industry, in addition to $3,000,000, is the use of some of our outdoor boards, help with point-of-sale distribution, smoker lists, and spokespeople (such as Danny Glover).

We speculate that PM is interested in full industry participation for reasons beyond money. We suspect they want to share the negative pr this effort is taking in the media and among elected officials.

Lee said that there is not a 50-50 chance that we will win this, but it isn't far off. Their main point (and that of the entire California team, including O'Mally) was that this is the only chance we have of making progress in that state.[111] [emphasis added]

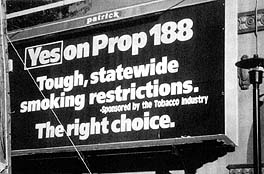

The CSSR attempted to present Proposition 188 as an anti-smoking measure. In doing so, the organization departed from previous tobacco industry election campaigns by emphasizing anti-tobacco themes: limiting youth access to tobacco, protection of nonsmokers, and accommodation (figure 14).

Yet Proposition 188 represented a rollback of existing California tobacco control laws. Philip Morris used the industry's usual rhetoric only in emphasizing that restrictions on tobacco represented unwarranted government intrusion into people's private lives; targeted mailings to its National Smokers' Alliance and other smokers' rights lists portrayed Proposition 188 as a chance to “preserve your right to smoke.”[112]

Figure 14. Tobacco industry billboard promoting Proposition 188 as a “tough” anti-smoking measure. The statement “Sponsored by the Tobacco Industry” was added by a graffiti artist. As originally displayed, the billboard did not disclose who was financing the campaign. (Photo courtesy of Julie Carol, Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights)

The “No” Campaign

The Coalition for a Healthy California chose “Stop Philip Morris” as its campaign theme. Polls dating back to 1978 had consistently shown that the tobacco industry had very low credibility among voters.[114][113][114] For example, a 1982 poll prepared for the Tobacco Institute as part of its effort to defeat a tobacco control initiative in Bakersfield revealed that “knowledge of tobacco company [opposition to a measure] does move a significant number of respondents into the `yes' column.”[113] The Coalition concluded that simply educating the voters about the tobacco industry's involvement with Proposition 188 would convince them to vote “no.”

By mid-September, the formal No on 188 campaign was launched. The ALA and ACS were actively working together, with Martin sharing the CHC chair with ACS volunteer Gaylord Walker. The Coalition held press conferences around the state, and press events aimed at informing the public that Philip Morris was behind the initiative. Following the press conferences, the tobacco industry received telephone calls from

Despite strong grassroots support for its position, the Coalition was having difficulty raising money to counter the tobacco industry's direct mail campaign. Knowledgeable observers—who knew Philip Morris was behind the campaign—could not believe that the voters would support Proposition 188 after several years of anti-tobacco public education funded by Proposition 99. According to Nicholl, Proposition 188 “was viewed as such an extreme and aggressive tactic by the tobacco industry that it couldn't possibly win.”[116]

Philip Morris's strategy, however, was working. The independent Field Institute California Poll in mid-July had shown the initiative ahead: 52 percent for, 38 against.[117] By mid-September, polls conducted by the Field Institute and the Los Angeles Times showed that voters were evenly divided.[118][119] Proposition 188 had a good chance of passing.

Media attention is generally attracted by controversy, and reporters usually seek to represent both sides of an issue. The tobacco industry was so committed to staying out of the public eye that CSSR had an unlisted telephone number and actively avoided journalists and public debates.[120][121] For example, when the League of Women Voters scheduled a debate to be broadcast in the Bay Area (the second-largest media market in California), CSSR refused to send a representative. Unable to take a formal position opposing the initiative due to its bylaws (which required equal consideration of both sides before taking a position on an initiative), the league canceled the debate.[122] When the Senate Health Committee and the Assembly Governmental Organizations Committee held the public hearing required by law to present issues raised by Proposition 188, CSSR refused to participate.[123] By shunning the spotlight, CSSR successfully minimized controversy over Proposition 188, clearly part of Stitzenberger's stealth strategy. The strategy allowed Philip Morris to control the message through direct mail advertising while denying the opposing camp the free forum that would have accompanied media coverage.

On October 21, 1994, John H. Hager of American Tobacco again wrote to Donald S. Johnston to brief him on the Proposition 188 campaign. He enclosed an analysis of Proposition 188.[109] A notable strength of Proposition 188 was low awareness of the measure, especially compared with two high-profile initiatives that were on the ballot (“three strikes,” which required long prison sentences for repeat offenders, and

American Tobacco knew something that the Coalition did not know. The California Wellness Foundation, a large California foundation, was thinking about launching a large nonpartisan voter education project to make sure that the public understood exactly what Proposition 188 meant—and who was supporting it and who was opposing it. While strictly neutral from a content perspective, this educational campaign would effectively smoke out the tobacco industry's involvement and expose its stealth strategy.

American Tobacco's analysis presented four major concerns:

- Wellness Foundation. While the official “NO” campaign has only $90,000 cash on hand as of 9/30, the nonprofit Wellness Foundation may spend anywhere from $1 million to $3 million in “non-partisan” radio spots. …They are being quoted non-profit rates, so this would also extend the reach of their buy. While we may be able to counter a $1 million buy, an effective $3 million buy to raise awareness of 188 sponsorship virtually dooms our campaign.

- Prop 99 ads. Even though they do not mention 188, the extent of these new ads pose[s] a real threat, especially if the NO campaign or the Wellness Foundation helps voters relate the theme of the 99 ads (lies and deceit) to the initiative.

- Media. The media could accomplish the above connection with little difficulty.

- C. Everett Koop. If the NO campaign has any money to put him on TV ads, we're in trouble.[109]

The tobacco industry did not have to worry about the Proposition 99 ads. Sandra Smoley, Governor Pete Wilson's secretary of health and welfare, had been one of two votes against the Sacramento County smoke-free ordinance in 1990 when she was a member of the Board of Supervisors. As secretary of health and welfare, she forbade DHS from doing any public education about AB 13, despite the fact that educating the public before such laws are implemented greatly smooths the process.

In anticipation of a major media blitz by CSSR, the Coalition laid out a strategy for utilizing paid advertising to get out its message. Nicholl produced television and radio advertisements highlighting the deceptive nature of CSSR's advertising. The Coalition ads featured former surgeon general C. Everett Koop, one of the signers of the ballot argument against Proposition 188.[116][124] But there was no money to broadcast the advertisements. With the discouraging September poll results indicating that Proposition 188 would win, the California voluntary health agencies approached their national organizations for money.

The AHA and ACS national organizations responded with substantial donations in late October, which represented a major shift in policy for these organizations. In the past they had considered measures like Proposition 188 as state matters to be handled by the state affiliates. National AHA and ACS leaders recognized that a victory for the tobacco industry in California, which had been regarded as a pioneer in tobacco control efforts nationwide, would not only have national repercussions but also help the industry pass preemptive statewide smoking regulations elsewhere.[125] The national ALA continued its past practice of not providing financial assistance to individual state campaigns,[127] but four ALA state affiliates (in Oregon, Maine, Nebraska, and Wisconsin) saw Proposition 188 as a national issue and sent a total of $32,800. The American Medical Association gave $25,000. The Kaiser Permanente health maintenance organization donated $50,000 and ran full-page newspaper advertisements opposing Proposition 188. These last-minute injections of cash allowed the Coalition to run the Koop advertisements for the last week of the campaign. The tobacco industry has long understood that local and state campaigns make an important contribution to national policy and has always treated these tobacco battles from a national perspective. The Proposition 188 campaign marked a growing, but still limited, recognition by the national organizations supporting tobacco control that state and local issues are strategically important.

The Wellness Foundation

The tobacco industry's fears were confirmed when the California Wellness Foundation initiated a nonpartisan educational campaign to give voters accurate information about Proposition 188. The Wellness Foundation was concerned that Philip Morris and the other tobacco companies were controlling the public's perception of Proposition 188. On October

After meeting with representatives of the Coalition and CSSR, the Legislative Analyst stated that Proposition 188 was weaker than the protection most Californians enjoyed. CSSR then sued the Legislative Analyst, Attorney General, signers of the ballot arguments against Proposition 188, and the Coalition, claiming the initiative's ballot label, title, summary, ballot arguments, and Legislative Analyst's statement did not present the public with nonprejudicial statements of the initiative's content and potential effects. On August 12, 1994, the Superior Court ruled in favor of the defendants and allowed the Voter Pamphlet to stand.

Despite the fact that the Public Media Center campaign did not support or oppose Proposition 188, the center's attorney received an inquiry from a deputy attorney general, investigating a complaint lodged against the California Wellness Foundation for supporting the educational campaign.[128] (California Attorney General Dan Lungren had close ties to the tobacco industry and the Dolphin Group, which managed his unsuccessful bid for governor in 1998.[129]) The deputy refused to specify who had lodged the complaint, but the Public Media Center interpreted it as a “clumsy attempt to intimidate us” by tobacco industry lawyers.[130]

By presenting the facts in a clear way, this educational advertising campaign focused media and public attention on the role of the tobacco industry in the Proposition 188 campaign, which forced CSSR to abandon

Another CSSR advertisement, which featured middle school vice principal Nancy Frick claiming that Proposition 188 would benefit children, backfired in the last week of October. (Frick's husband had appeared in one of CSSR mailings.[132]) The Coalition sharply criticized the advertisement, emphasizing the industry's deceptive practices.[133] Two days later, the Coalition persuaded Frick to retract her comments and widely distributed the retraction, in which she stated that she was unaware Proposition 188 would overturn 300 local laws.[122][134-136] She also demanded that the advertisements be taken off the air.

The Federal Communications Commission

ANR decided to use the truth-in-advertising provisions of the Federal Communications Act to force the tobacco industry to clearly disclose its sponsorship of Proposition 188 in radio and television advertisements. ANR reasoned that requiring disclosure of tobacco industry funding would reduce the effectiveness of the Yes on 188 advertisements, and perhaps even make them counterproductive. ANR had used a similar tactic successfully during the Proposition P campaign in San Francisco in 1983 (see chapter 2). On October 20 ANR sought help from the Media Access Project, a nonprofit telecommunications law firm in Washington, DC.[137] Since CSSR had filed with the California secretary of state as “Californians for Statewide Smoking Restrictions—Yes on 188, a committee of Hotels, Restaurants, Philip Morris, Inc. and other tobacco companies,” as required by California law, the Media Access Project believed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) would likely agree that all CSSR's advertisements should reveal the entire committee name.[137]

On October 21 ANR informed all radio broadcasters running CSSR's

ANR's actions took place the same day that the Coalition held a press conference unveiling its Koop advertisement, with the hope of generating free media attention. (At that point the Coalition still did not have money to purchase air time to run the advertisements.) Although the other Coalition members failed at first to see the value of the ANR strategy, once the complaint proved useful, they cooperated with ANR. Ten days later the Coalition joined ANR in a new complaint to the FCC against television broadcasters who refused to modify CSSR's advertisements to disclose the tobacco companies' involvement.[141] On November 1 the FCC made an informal determination that proper disclosure after CSSR's commercials should include the information about tobacco industry sponsorship.[142]

By November 2, 1994, the tobacco industry's tracking polls showed that Proposition 188 was losing, along with these findings:

As voters become more aware of the initiative's sponsorship, they tend to become opposed to Proposition 188.

We have learned the opposition has doubled their air time purchase for the remainder of the campaign using Wellness Foundation money.

We have targeted mailings, television and radio spots dropping during the next three to five days. Unpaid media continues to be manageable, but the infusion of Proposition 99 ads and Wellness Foundation funded ads are responsible for the shift in poll numbers.[143]

On November 8, Proposition 188 was defeated by a vote of 71 percent against to 29 percent for—the widest spread of any measure on the ballot. Thirty-eight percent of the people who voted against Proposition 188 stated that they did so to protect smoke-free public places, and another 22 percent voted against it because it was sponsored by the tobacco industry.[144] Seventeen percent of the people who voted for the initiative did so because they still felt it was an anti-smoking measure. Proposition 188 lost in every county in California, liberal and conservative, urban

AB 13 was implemented on January 1, 1995. Restrictions on smoking in bars were to take effect January 1, 1997. The following year the tobacco industry convinced the Legislature to delay the smoke-free bar provision until January 1, 1998; the public health groups, who thought that the state was not ready for smoke-free bars at the time, put up only token opposition. In the fall of 1997 the tobacco industry tried to delay the effective date again. This time the health groups mobilized and beat the industry. Senate president pro tem Bill Lockyer shifted sides and helped the health groups defeat the tobacco industry. On January 1, 1998, all bars in California became smoke free.

Conclusion

In California 1994 was a busy year for tobacco control. By bringing together business, labor, local government, and health organizations, Friedman and the AB 13 support coalition successfully transformed public sentiment against smoking into statewide legislation that the tobacco industry did not like. The voluntary health agencies disseminated information about the adverse health effects of secondhand smoke, the CRA helped dispel fears that state smoking restrictions would hurt the restaurant business, and the League of Cities lent support to arguments that the bill would not limit the power of local governments to pass stricter restrictions than those contained in the bill. The coalition prevented the tobacco industry from taking control of the bill and passing a blatantly pro-industry version in the guise of tobacco control.

However, there was no consensus among California's tobacco control advocates on whether it was acceptable to compromise on preemption. Tobacco control advocates in Sacramento viewed the preemption clause in AB 13 as an acceptable compromise because of its 100 percent smoke-free mandate. They did not consider players outside Sacramento relevant, an attitude that damaged efforts to build support in the field for state-level legislative efforts. When asked about the disagreement within the California tobacco control movement over AB 13, a representative

In 1994 the tobacco industry was nearly successful in tricking California voters into repealing their own tobacco control laws. If the tobacco industry had been able to maintain its original strategy of a stealth campaign, its effort might well have succeeded. By limiting itself to direct mail, the industry would have stayed within a medium where it could control the message and deprive the health community of a platform. However, once the industry was forced out into the more public realm of mainstream advertising, it lost control over the public discourse about Proposition 188.

The Proposition 188 battle reunified tobacco control advocates as they put the fights over AB 13 behind them. According to one LLA director, “The whole process of that [AB 13] was real divisive. You know, we had members on our coalition who were saying, `No, this is great and although it's not perfect, it's better to have something than nothing.' And it's like, `But is it good to have something that's a piece of trash? That's going to eliminate ever doing anything better?'…Huge arguments. Once it finally passed and then Prop 188 came along, it was interesting, everybody sort of banded back together in the fight against Philip Morris.”[57] California's tobacco control community was able to unify against and defeat Philip Morris.

But the passage of AB 13 and defeat of Proposition 188 significantly distracted the health groups from the fight to reauthorize the Proposition 99 programs. The legislation authorizing expenditure of Proposition 99 funds expired on June 30, 1994, at the height of the AB 13 debate and shortly after Proposition 188 had qualified for the ballot. AB 13, in particular, dominated the tobacco control agenda in California, draining the resources of health groups and commanding attention by the press and public.[147] So in what was a critical year for Proposition 99, its chief defenders were largely occupied elsewhere, which did not bode well for reauthorization. In addition, AB 13 and Proposition 188 would give the CMA and other medical groups cover for diverting Health Education Account monies. Proposition 99 was destined for another hard year in the Legislature.

Notes

1. Russell C. “ Letter to Stanton Glantz. June 6, 1996” .

2. Pierce JP, Evans N, Farkas AJ, Cavin SW, Berry C, Kramer M, Kealey S, Rosbrook B, Choi W, Kaplan RM. Tobacco use in California: An evaluation of the Tobacco Control Program, 1989-1993. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego, 1994.

3. Patten C, Pierce J, Cavin S, Berry C, Kaplan R. “Progress in protecting non-smokers from environmental tobacco smoke in California workplaces” . Tobacco Control 1995;4:139-144.

4. Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services. Are Californians protected from environmental tobacco smoke? A summary of findings on worksite and household policies: California Adult Tobacco Survey. Sacramento, 1995 September.

5. Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services. Is smoking prohibited in work areas? Sacramento, June 11, 1996.

6. Tobacco Institute, State Activities Division. “California: A multifaceted plan to address the negative environment.” Washington, DC, January 11, 1991. Bates No. 2023012755/2944.

7. Siegel M, Carol J, Jordan J, Hobart R, Schoenmarklin S, DuMelle F, Fisher P. “ Preemption in tobacco control: Review of an emerging public health problem” . JAMA 1997;278(10):858-863.

8. Macdonald HR, Glantz SA. “The political realities of statewide smoking legislation” . Tobacco Control 1997;6:41-54.

9. Kerrigan MJ. “ A proposed comprehensive tobacco control act in California/RIIPP: Memo to Smokeless Tobacco Council, Committee of Counsel. June 28, 1991” .

10. Lucas G. “ Panel defeats no-smoking bill linked to Brown” . San Francisco Chronicle 1991 September 6.

11. Glantz SA, Begay ME. “ Tobacco industry campaign contributions are affecting tobacco control policymaking in California” . JAMA 1994;272(15):1176-1182.

12. Webb G. “ Speaker disguised smoking bill, memo says” . San Jose Mercury News 1991 August 27.

13. Richardson J, Kushman R. “Advice to tobacco firms admitted” . Sacramento Bee 1991 August 30.

14. Lucas G. “ Health groups blast tobacco-industry bill” . San Francisco Chronicle 1991 September 6.

15. Begay ME, Traynor MP, Glantz SA. The twilight of Proposition 99: Reauthorization of tobacco education programs and tobacco industry expenditures in 1993. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1994 March.

16. Friedman T. “ Labor chairman's bill would ban workplace smoking. Press release, February 13, 1992” .

17. American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, American Heart Association. “ No time like the present. Memo, June 11, 1992” .

18. Griffin MJ. “ Letter to Assembly Member Friedman. April 3, 1992” .

19. Carol J. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. February 15, 1994” .

20. Pertschuk M. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. March 10, 1994” .

21. Kiser D. “ Rationale for support of AB 13 (Friedman) and information on Cal-Stop. Memo to Bob Doyle, Lisa Gaspard. February 16, 1993” .

22. California Restaurant Association. “ Wake up and smell the smoke. Sacramento, 1993 May” .

23. California Restaurant Association. “ Smoking laws: CRA position statements. Sacramento, June 5, 1990” .

24. Gillam J. “ Panel rejects workplace smoking ban” . Los Angeles Times 1992 June 18.

25. Thompson J-L. “Letter to Assembly Member Terry Friedman. June 12, 1992” .

26. Friedman T. “ AB 2667, as amended June 23, 1992. Sacramento, 1992” .

27. Najera A. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. February 18, 1994” .

28. Kiser D. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. January 18, 1994” .

29. Du Melle F, Davis A, Ballin S. “Alert on tobacco industry-initiated clean indoor air legislation and/or amendments. Memo to State Executives, State Public Issue Staff, Tobacco-Free America. February 14, 1989” .

30. Friedman T. “ Letter to Teresa Velo. February 22, 1993” .

31. Velo T. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. January 18, 1994” .

32. Abate B, Najera T. “ Clarifying Assembly Bill 13 statewide smoking ban and urging strong support by all affiliates. Memo to Affiliate Presidents, Affiliate Executive Directors, Other Interested Parties. March 1993” .

33. Alvarez B. “ Letter to Assembly Member Terry Friedman. March 2, 1993” .

34. Samuels BE, Begay ME, Hazan AR, Glantz SA. “ Philip Morris's failed experiment in Pittsburgh” . J Health Policy, Politics, and Law 1992;17(2):329-351.

35. Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights. “Position on AB 2667: Neutral. Position statement, June 17, 1992” .

36. Ennix C, Abate B, Edmiston WA, Yamasaki G, Corlin RF. “Memo to interested parties. 1993” .

37. Burastero AM. “ Letter to Terry Friedman. April 9, 1992” .

38. Assembly Committee on Labor and Employment. “ Committee analysis: AB 13 (T. Friedman)—As amended: February 22, 1993. March 3, 1993” .

39. Sweeney JP. “ Wide-ranging smoking ban clears hurdles” . Santa Monica Outlook 1993 March 10;B2.

40. Carol J, Pertschuk M. “Letter to Assembly Member Friedman. December 12, 1992” .

41. Blum A. “ Letter to Mark Pertschuk, Julia Carol, ANR Board Members. June 9, 1993” .

42. McIntyre C. “ Letter to Assembly Member Terry Friedman. August 23, 1993” .

43. Snider JR. “ Letter to Assembly Member Larry Bowler. March 12, 1993” .

44. Friedman T. “ AB 13, as amended February 22, 1993. Memo to interested parties. March 18, 1993” .

45. Environmental Protection Agency. “Respiratory health effects of passive smoking: Lung cancer and other disorders.” Report No. EPA 600/6-90/006F. Washington, DC, December 1992.

46. Friedman T. “ AB 13, as amended April 12, 1993. April 12, 1993” .

47. Hunter Y. “ Letter to Assembly Member Terry Friedman. May 3, 1993” .

48. Morain D. “ Legislature aims fusillade of bills at tobacco industry” . Los Angeles Times 1993 March 10;A1.

49. American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers. “ASHRAE Standard 62-1989: Ventilation for acceptable indoor air quality.” Atlanta, GA, 1989.

50. Daynard R. “ What is ASHRAE and why we should care?” Paper presented at a workshop on nonsmokers' rights at the 7th World Conference on Tobacco and Health, Perth, Australia, March 30, 1990 (rev. September 10, 1990). Available from Tobacco Control Resources Center, Northeastern University, Boston.

51. Forster JL, Hourigan ME, Kelder S. “ Locking devices on cigarette vending machines: Evaluation of a city ordinance” . Am J Pub Health 1992;82(9):1217-1219.

52. Kotz K, Forster J, Kloehn D. “An evaluation of the Minnesota state law to restrict youth access to tobacco. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, San Francisco, 1993” .

53. Miller J. “ Staff analysis of Assembly Bill 996 (Tucker) as amended May 4, 1993. August 4, 1993” .

54. Sacramento Bee. “ Tucker's odorous tobacco bill. Editorial” . Sacramento Bee 1993 April 27.

55. “It's amazing what money can buy” . Petaluma Argus-Courier 1993 June 8.

56. Scott J, Waltman N. “Interview with Heather Macdonald. March 1, 1994” .

57. LLA Director 5. “Interview with Edith Balbach. 1998” .

58. McCormick E. “ Tobacco money tied to smoke bill vote” . San Francisco Examiner 1993 June 4;A21-A24.

59. Spears L. “ Assembly OK's bill to snuff out smoking bans” . Contra Costa Times 1993 June 4;1.

60. Morain D. “ Assembly bill curbs LA's smoking ban” . Los Angeles Times 1993 June 4.

61. Benson L. “ Attached economic impact study and subsequent print and electronic press coverage re: Proposed 100% smoking ban. Memo to members of the California Senate. June 16, 1993” .

62. Levin M. “ Study halts bid to curb smoking” . Los Angeles Times 1992 June 18.

63. Price Waterhouse. “Potential economic effects of a smoking ban in the state of California.” N.p., 1993 May.

64. Coopers & Lybrand. “Letter to Stanley R. Kyker. June 29, 1993” .

65. Harrison S. “ Assembly reverses smoke vote” . Woodland Hills Daily News 1993 June 8.

66. Morain D. “ Assembly OK's tough anti-smoking bill it rejected earlier” . Los Angeles Times 1993 June 8;A3,A27.

67. Miller J. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. January 14, 1994” .

68. Laufer D. “ E-mail to Tina Walls re: San Fran. and CA. November 1, 1993” . Bates No. 2045891104.

69. Matthews J. “ Senate panel switches, OKs smoking limits bill” . Sacramento Bee 1993 July 15;A3.

70. Brady DE. “ Battle over smoking is heating up” . Los Angeles Times 1993 July 23, Valley edition.

71. Scott S. “ Is Terry Friedman giving away too much?” California Journal Weekly 1993 September 6;3.

72. Merlo E. “ E-mail to David Laufer re: San Fran. and CA. November 2, 1993” . Bates No. 2045891103C.

73. Merlo E. “ Memorandum to Geoff Bible. January 12, 1994” . Bates No. 2022839335.

74. Charlton Research Company. “Philip Morris California statewide.” San Francisco, November 10, 1993. Bates No. 2023324575/4669.

75. Hyde T. “ Memo to Tom Griscom and Roger Mozingo re: California proposal. January 17, 1994” . Bates No. 51256 8081.

76. Californians for Statewide Smoking Restrictions. “ California Uniform Tobacco Control Act xt of proposed initiative]. 1994” .

77. Woodruff T, Rosbrook B, Pierce J, Glantz S. “Lower levels of cigarette consumption found in smoke-free workplaces in California” . Archives of Internal Medicine 1993(153):1485-1493.

78. Stillman F, Becker D, Swank R, Hantula D, Moses H, Glantz S, Waranch H. “Ending smoking at the Johns Hopkins medical institutions: An evaluation of smoking prevalence and indoor air pollution” . JAMA 1990;264:1565-1569.

79. Patten CA, Gilpin E, Cavin S, Pierce JP. “Workplace smoking policy and changes in smoking behavior in California: A suggested association” . Tobacco Control 1995;4:36-41.

80. Macdonald HR, Glantz SA. Analysis of the smoking and tobacco products, statewide regulation initiative statute. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1994 March.

81. Mortensen J. “ Letter to Philip Morris USA retailers. September 19, 1994” .

82. Goebel K. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. June 5, 1995” .

83. Carol J. “ Interview with Heather Macdonald. July 11, 1995” .

84. Martin C. “ Letter to friends. February 8, 1994” .

85. Martin C. “ Memo to Coalition for a Healthy California (Revived). February 18, 1994” .

86. Bullet Poll. California smoking research. Verona, NJ: Hypotenuse, Inc., March 10, 1994.

87. Dobson PH. “ Letter. January 28, 1994” .

88. Waters G. “ Letter to Kathleen DaRosa. March 1, 1994” .

89. Nicholl J. “ Memo re: Draft 100-word title and summary. February 25, 1994” .

90. Attorney General. “ Title and summary of the chief purpose and points of the proposed measure. Sacramento, March 9, 1994” .

91. Friedman T. “ AB 13, as amended March 7, 1994. 1994” .

92. Friedman T. “ AB 13, as amended April 6, 1994. 1994” .

93. Weintraub DM, Ingram C. “Final budget bills stall as Senate tries to alter measure” . Los Angeles Times 1993 June 29.

94. Senate Judiciary Committee. “ Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing. Sacramento, March 22, 1994” .

95. Hunter Y. “ Letter to Terry Friedman. April 14, 1994” .

96. American Cancer Society. “ Position statement. March 23, 1994” .

97. American Lung Association. “ Oppose AB 13 (T. Friedman)—Workplace smoking. Memo, March 23, 1994” .

98. Kiser D. “ Position statement. March 22, 1994” .

99. Lucas G. “ State anti-cigaret bill weakened” . San Francisco Chronicle 1994 March 23.

100. “A rape in Sacramento” . Editorial. Los Angeles Times 1994 March 27.

101. Friedman T. “ Statement of Assemblyman Terry Friedman on Senate attack on anti-smoking legislation” . Press release, March 23, 1994.