10. Continued Erosion of the Health Education Account: 1990-1994

Proposition 99's anti-tobacco programs were off to a good start. The media campaign had achieved high visibility within California and attracted international acclaim. The local programs were up and running, and local clean indoor air ordinances and tobacco control measures were passing at a faster rate. On October 30, 1990, the Department of Health Services (DHS), which was implementing all the Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education programs except the school-based programs, estimated that California had 750,000 fewer smokers than it would have had if Proposition 99 had not passed, that the percentage of smokers over the age of twenty had dropped from 24.6 percent to 21.2 percent, that tobacco consumption was down 14 percent, and that between 62 percent and 85 percent of the target groups were aware of the media campaign.[1][2] With such a strong early-performance record, public health advocates should have been in a position to protect the Health Education Account from the tobacco industry and its allies who wanted to see more money go to medical services.

AB 75's sunset provision took effect on June 30, 1991, only twenty-one months after passage, so the Legislature had to enact new implementing legislation for Proposition 99 in 1991. This situation created a new opportunity for the tobacco industry and its allies to dismantle the anti-tobacco programs. The health groups believed that their earlier compromise with the California Medical Association (CMA) and other

The state was facing a budget shortfall, which further motivated groups interested in funding medical services to raid the Proposition 99 Health Education Account. Ironically, the very success of the Tobacco Control Program in reducing tobacco consumption magnified this problem: less smoking meant fewer cigarettes sold, which meant lower Proposition 99 tobacco tax revenues. Public health groups recognized from the beginning that the Health Education revenues would decline naturally as smoking did and that, as the program succeeded in reducing tobacco consumption, it would become less necessary. But they did not anticipate that medical service providers would work to cut health education funds faster than the natural rate of decline. For medical service providers, who faced escalating costs and a growing population demanding services, a drop in revenue due to less smoking motivated them to fight for a bigger piece of the shrinking financial pie.

In addition, the tobacco industry was continuing to make substantial campaign contributions to most members of the Legislature, with especially heavy donations going to the leadership. In the 1991-1992 election cycle, the industry spent $5.8 million on campaign contributions and lobbying in California. Because of the importance of Proposition 99, the tobacco industry spent $3,772 per member in the California Legislature in 1989-1990, compared with only $2,451 per member in the US Congress.[3][4] In particular, the industry increased contributions to Assembly Speaker Willie Brown, who was uniquely positioned to defend the industry's interests.

California also had a new governor. In November 1990 Pete Wilson was elected to succeed George Deukmejian. While both were Republicans, their attitudes toward initiatives differed. Deukmejian might oppose an initiative during an election (as he had Proposition 99), but he would then respect the will of the voters and make an honest effort to implement any initiative that passed, including Proposition 99.[5] By contrast, Wilson believed that it was his prerogative to “massage” initiatives.[6]

Early Postures

Legislative activity surrounding Proposition 99 began in the fall of 1990 with the formation of a steering committee of the organizations that had been most interested in AB 75, including the voluntaries, the CMA, California Association of Hospitals and Health Systems (CAHHS), Service Employees International Union (SEIU), Western Center for Law and Poverty, and others. The committee was to provide a forum for the groups to communicate with each other about new legislation. According to American Lung Association (ALA) lobbyist Tony Najera and Senator Watson's chief of staff, John Miller, the steering committee and Assembly Member Phil Isenberg (D-Sacramento), who had chaired the Conference Committee that wrote AB 75, agreed to extend the existing programs and distribution formulas without substantive changes, to share pro rata in the 14-18 percent reduction in revenues, and to minimize conflicts and press for fast-track passage of legislation authorizing the Proposition 99 programs by March 1991.[7] In light of the political deal that the public health advocates had made to ensure AB 75's passage as well as the newness of the programs, this was not an unreasonable position. The debate was becoming simply how to divide up another pie in Sacramento.

On January 7, 1991, the three voluntaries, the CMA, CAHHS, SEIU, Western Center for Law and Poverty, and other interested parties wrote to Isenberg and the other members of the Conference Committee, urging them to extend the provisions of AB 75:

Our organizations have worked together through-out the implementation phases of AB 75 to assure that legislative policy objectives are being achieved. We now join in urging your support for a three year extension of the provisions of AB 75, as contained in AB 99 (Legislative Session 1991-92), in order to assure the continuation of the programs and services that are funded with these tobacco tax proceeds. In order to secure a stable and efficient administration at both the state and local level, it is critical to obtain an extension of the provisions of AB 75 well in advance of the sunset date.[8]

This reauthorization strategy meant that if everyone played by the rules, then programmatic issues related to the allocation of money would not be raised, including the issue of using the Health Education Account to fund CHDP. The health groups felt that this was the best strategy to avoid further erosion in funding of anti-tobacco education because it would not force them to defend the efficacy of the Tobacco Control Program, which was just building steam. They did not want to appropriate

The public health groups honored their side of the agreement, although it meant accepting the continued diversion of funds from the Health Education Account into medical services. The Tobacco Education Oversight Committee (TEOC), the committee created by the Legislature to provide advice about Proposition 99 implementation, supported using Health Education Account money for CHDP. TEOC's position was articulated through statements by its chair, Carolyn Martin, a volunteer with ALA, and Jennie Cook, a volunteer with ACS. At a January 23 press conference, Martin described the activities funded by the Health Education Account, including CHDP: “The prevention message is reaching every group targeted by the enabling legislation (AB 75) in settings as diverse as fast food restaurants, clinic waiting rooms and half time at the Chargers-49ers exhibition game.”[10] Jennie Cook explicitly justified the use of Health Education Account funds for medical services: “Pregnant women who smoke become parents who smoke around their young children causing increased respiratory illness, ear infections, and reduced growth. Education efforts have begun in many prenatal care settings and maternal and child health programs.”[10] No one was willing to question whether CHDP should continue to receive funding from the Health Education Account.

The CMA Position

In contrast to the voluntary health agencies, which demonstrated commitment to all programs, the CMA was soft on the issue of funding programs other than medical services. Although the CMA signed the January 1991 letter to Isenberg, on November 10, 1990, the CMA Council had adopted a recommendation that the existing Proposition 99 expenditure patterns be extended “until CMA's affordable basic care proposal or a similar proposal is implemented.”[11] AB 75 distributions were acceptable only until the money was needed to pay for indigent health care. According to CMA Resolution 9021-90,

(1) CMA supports funding of tobacco education programs through the years 1990 and 1991, as approved by the voters of California in Prop. 99. (2) CMA will monitor the progress of the State's evaluation of the effectiveness of the

― 186 ―Prop. 99 health education account. (3) CMA will work in conjunction with the legislature and with other groups interested in tobacco education and access to care, toward the goal of utilizing tobacco tax revenues for access to care as soon as feasible, while maintaining adequate funding for tobacco education.[12] [emphasis added]

The council had reiterated its basic position that using Health Education dollars for public health programs was an interim measure, that funding health care was the preferred policy, and that anti-tobacco education was entitled only to “adequate” funding, not “full” funding.

In 1990, when chief CMA lobbyist Jay Michael was questioned about CMA policy by Lester Breslow, a member of the TEOC and former dean of the UCLA School of Public Health, Michael responded, “The CMA's policy relating to the distribution of Prop 99 monies until June 30, 1990, was consistent with our long-range policy relating to the ultimate use of Prop 99 funds in the future. …CMA's general policy for the short term was to ensure that physicians received their fair share of the health care funding provided by Prop 99, which was intended to temporarily patch up our health care delivery system until such time as an overall solution can be achieved to address our most serious health care problems.”[13] He went on to reiterate the CMA position emphasizing that $30 million is enough to mount a massive campaign in the schools and that a public media campaign is not likely to be effective.[13-15]

The CMA was also prepared to contest the evaluation data that showed the programs' effectiveness. When interviewed in 1993, Michael expressed his attitude about the evaluation:

Did you read the study that was done by the Department of Health Services or commissioned by the Department of Health Services? I think that's a sloppy study; it's undocumented; the conclusions, or the data do not support the conclusions. …Why? Because the money was vulnerable to being diverted to other purposes in a tight state budget year. And they were desperate and it was a survival response. And I don't fault them for that. I've been in this business for a long time, and that's the way people behave. It's very hard to be judgmental about things like that. …But to cloak their biased stacked study in objectivity is offensive to me. …The issue is: is that the most cost-effective way to use that money to improve health and to reduce the amount of tobacco addiction? And I don't think that study has ever been made. As an advocate of the point of view that it ought to be given to health care providers and health care providers should be educated, trained to get people to stop smoking, I'm advocating that. I don't have a clue as to whether that's the most cost-effective way to use the money. I'm saying it ought to be evaluated along with every other kind of use of that money by someone who really does an objective

― 187 ―job. And the money shouldn't be split up on the basis of these hokey trumped-up biased advocates for a particular interest group.[16]

For the public health groups, or the “dread disease organizations,” as Michael called them, these comments were not those of someone who wanted to maintain the status quo.

The CMA's most immediate concern was to prevent any drop in money for health services. The “maintenance of effort” clause in Proposition 99, which required that the new tobacco tax money be used to supplement rather than replace existing state funding, was an issue in the fall of 1990. The 1990-1991 state budget had reduced funding for county Medically Indigent Service Programs and for Medical Services Programs. According to the CMA Council minutes, most counties believed that they could not maintain existing levels of service and thus would not be able to qualify for Proposition 99 funds, so they had asked to have the maintenance of effort requirement waived for fiscal year 1990-1991. The CMA went on record as opposing any waiver of maintenance of effort requirements.[17]

At the same time, on November 1, 1990, the Tobacco Institute was also planning its 1991 legislative strategy for neutralizing Proposition 99. The main goal was to “divert the media funds,” and the institute saw a chance to achieve this diversion:

The decrease in revenues will increase the competition for funding in the 91-92 budget among the various program elements. Additionally, California is expecting a shortfall of as much as $2 billion, possibly more, in the next fiscal year. That will tempt the new administration and the Legislature to supplant existing general fund revenues with Proposition 99 revenues where appropriate programs exist. The women, infants and children and the health screening programs are appropriate programs since they contain anti-tobacco education elements and would satisfy the dictates of Proposition 99… .

Proposition 99 revenues are down which will pit the sponsors of the initiative against one another as they seek funding for their favorite programs. Confusion and animosity will result. …A coalition of interests could be built to chase the media money. The nucleus of such a coalition could be the minority health communities which feel not enough of the Proposition 99 money is getting to the streets. Other coalition members would be the rural counties, a few of which are facing bankruptcy. Public hospitals desperately need money to fund trauma centers. Other interest groups would join the chase if they thought the money were in play.[18] [emphasis added]

Rather than battling Proposition 99 in the open, the tobacco industry would help orchestrate other interests who wanted the money. The industry

Governor Wilson's Budget Cuts

The hope among health groups for a fast-track reauthorization of the Proposition 99 anti-tobacco programs was shattered when Republican governor Pete Wilson released his first budget on January 10, 1991. Although the Health Education Account contained $161 million ($38 million carried over from previous years, $7 million in interest, and $116 million in new tax revenues),[19] the governor appeared to accept the CMA's plan to spend just $30 million on the DHS anti-tobacco programs.

The governor's budget represented a huge cutback for the Tobacco Control Program. The local lead agencies (LLAs) and the media campaign were each to receive $15 million. The LLAs had previously been receiving $36 million annually, and the media campaign, $14 million annually. The competitive grants program would be ended entirely, after receiving over $50 million during the life of AB 75 and as much as $11 million in 1990-1991. (The Tobacco Control Section of DHS was also budgeted to receive $2 million for state administration.) Wilson proposed cutting the California Department of Education (CDE) to $16 million annually for local programs and state administration, down from $36 million. In total, Wilson proposed that the overall Tobacco Control Program was to receive only 30 percent of the available Health Education Account revenues,[19] or only about 6 percent of tobacco tax revenues (as opposed to the 20 percent specified in Proposition 99). He also proposed cutting the research program in half, to less than 3 percent of tobacco tax revenues (as opposed to the 5 percent specified in Proposition 99).[20]

The major beneficiaries of the governor's cuts in the anti-tobacco programs were a new perinatal insurance program called Access for Infants and Mothers (AIM), which would get $90 million, $50 million of which would come from the Health Education Account, and CHDP, which would be increased from $20 million to $43 million.[2] AIM provides medical care to pregnant women and their young children by subsidizing private insurance coverage. Because AIM pays a higher reimbursement rate to providers than does MediCal (California's version of Medicaid), it is more popular with medical providers and more expensive than MediCal.[21]

The March 26, 1991, issue of Capital Correspondence, the ALA's newsletter to activists, urged them to support AB 99 as it had been introduced by Isenberg, with across-the-board reductions, which meant continued support for diverting Health Education Account funds into CHDP. Among the “writing/speaking points” was the comment that “the provisions of AB 75 (now AB 99) set forth a reasonable and fair system to improve health care and health education programs.”[22] The strategy of the voluntaries was to move AB 99 through the Assembly and Senate as fast as possible so the Conference Committee could work at resolving differences among the groups and between AB 99 and the governor's budget. AB 99 passed in the Assembly Health Committee by a 12-0 vote on March 5, 1991, in the Assembly Ways and Means Committee by a 19-0 vote on March 20, and on the Assembly floor by a 68-0 vote on March 21.[23]

The health groups continued to ignore the original mandate for how the Proposition 99 money was to be spent, and they abandoned any interest in framing the issue as “obeying the will of the voters.” Isenberg again chaired the legislative conference committee that was to draft new legislation. The bill to appropriate the Proposition 99 funds was AB 99. He was joined by the other original AB 75 Conference Committee members. A conference committee is very much an “insider” forum, often featuring bipartisan negotiation. When political parties engage in collusive or “bipartisan” policy making, especially when both are financed by the same special interests, the public is often excluded from the process, with no knowledge of what is being done and no chance to influence it.[24] The voluntaries had thus agreed to a fast-track process that gave them limited power. By sending the bill to a conference committee, tobacco control advocates lost the advantage of public debate and review, their chief source of power to protect Proposition 99.

The Tobacco Industry's Strategy

Within RJ Reynolds, the governor's budget was welcomed as “the first positive news we have received relative to diverting funds from the Proposition 99 Tobacco Education Account.”[25] According to a company memo, “In view of Governor Wilson's action, we anticipate a funding frenzy developing on the part of counties, health groups, and others to divert even more of the funds.”[25]

An RJ Reynolds strategy memo of January 29 viewed the governor's

The industry also explored the feasibility of shifting anti-tobacco education money away from the anti-smoking advertising campaign and into the schools, which the industry considered less threatening. The RJ Reynolds memo observed, “School education and increased parental involvement are seen as the most effective ways to discourage underage smoking—35% and 19% respectively. While this does not speak directly to Prop 99 advertising, it does speak to the importance of `traditional' forms of education.”[26] The plan was to mount a credible campaign to demonstrate that the industry could handle the youth issue itself, because “underage smoking is widely perceived as the most critical problem and single largest impediment to industry credibility.” However, the memo concluded with the comment that “any credible attempt to address the youth smoking issue must include a school/youth group program given public opinion on the importance of school education.”[26]

The Final Negotiations

By June 1991, the CMA's board of directors had endorsed a resolution supporting the governor's proposed reallocation from the Health Education Account to AIM, thus ending any pretense to preserve the status quo. They also supported the reallocation of money from the Physician's Services Account to AIM because those funds “would be used for insurance programs that are likely to pay much higher reimbursement levels to physicians than the maximum of 50% of amount billed that is authorized under Prop 99. There are also significant surpluses being accumulated in Prop 99 Physician Service Accounts which are dedicated to paying for emergency, pediatric and obstetrical services.”[27]

On June 13, 1991, Senator Diane Watson wrote to the Legislative Counsel, the Legislature's lawyer, asking whether Health Education Account

specifically limits the use of the funds in the Health Education Account for programs for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use, primarily among children, through school and community health education programs. …These funds cannot be used for purposes other than programs for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use. A program for expanded prenatal care is not a program for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use, through school and community health education programs, except to the extent that the program might involve education to prevent or reduce the use of tobacco by prospective parents.[28] [emphasis added]

The Legislative Counsel advised that the Legislature could divert Health Education money to medical services only by returning to the voters with a new statute; a four-fifths vote of the Legislature would not suffice because such diversions were not consistent with the intent of Proposition 99.[28]

The legislative process was not disturbed by this legal opinion pronouncing the diversions illegal, nor by subsequent opinions requested by Isenberg and Elizabeth Hill, the Legislative Analyst.[29][30] The CMA, the Western Center for Law and Poverty, the California Nurses Association, and CAHHS wrote to the Conference Committee on June 30, 1991, suggesting language to strengthen the rationale for funding AIM through the Health Education Account. To make these medical programs appear to be anti-smoking education programs, the organizations wanted to add the clause “Health Education Services, smoking prevention, and where appropriate, smoking cessation services also shall be required.”[31]

The voluntaries ended up supporting the diversion into AIM. The ALA argued, as it had done with CHDP, that it would be “a one-time grant of $27 million to provide tobacco related services to this population. Authorization of AIM incorporates and specifies the services to be provided. We believe this will be a one time allocation.”[32] Both the ALA newsletter and an earlier Action Alert sent from all three voluntaries emphasized that this was a legal and appropriate compromise:

With the support of some important allies, the tri-agencies developed a counterproposal to the governor's AIM proposal. Our proposal honors the governor's desire to provide perinatal care to low-income women, yet most importantly, presents an alternative funding mechanism which does not inappropriately or illegally use Health Education Account monies. Our proposal

― 192 ―provides a coordinated and integrated approach to a perinatal community-based program with an anti-tobacco health education component.[33] [emphasis in original]

In addition, the voluntary health agencies continued to support funding for CHDP. The ALA newsletter summarized their position:

Our agreement also committed us to support the full caseload of services to young children in the Child Health and Disability Program (CHDP). We have in the past, sponsored most of this service ($20 million annually) in order to provide anti-tobacco services and referrals to these children and their families. Our expanded CHDP responsibilities are expected to total $35 million a year. This is an ongoing commitment, though AB 99 required much closer auditing of the CHDP program in order to assure that needed services are being provided.[32]

The statement is noteworthy in its reference to CHDP as “an ongoing commitment” and in its reference to CHDP funding as “our expanded CHDP responsibilities,” implying an agreement that CHDP would be a Health Education Account expense.

The voluntaries agreed to the diversion on June 30.[34] John Miller later recalled that, during the negotiations, “the legislative leadership came down on me and demanded that I give up $20 million, and I looked at the program and figured, `What can I give up that's least harmful?' And I came up with Local Leads because they weren't always the wonder boys we all think of them now.”[35] The Sacramento insiders had been leery about giving money to the local level in 1989 under AB 75 and were willing to reduce their funding now to get a compromise. The tobacco industry would not have objected. The local programs were costing the industry considerable time and money, and stopping the local programs had already become an industry priority.

AB 99 Emerges

The legislature eventually adopted AB 99, which authorized expenditures from the Health Education, Physician Services, Medical Services, and Unallocated Accounts until 1994. The final version of the bill diverted increasing amounts of Health Education Account money into medical services. The Legislature took $27 million out of the Health Education Account for the AIM program, and CHDP's budget went from $20 million to $35 million a year. In an action that was to have a major impact at the local level, the LLAs were required to spend one-third of

The voluntaries supported using some of the LLA money for outreach to pregnant women “in exchange for the provision of anti-tobacco education.”[32] But CPO did not provide anti-tobacco education; it took LLA money that had been used to deliver tobacco programs and shifted it to an outreach effort (like AIM) that would bring women into medical services. The immediate result was fewer tobacco programs because of the redirection of LLA funds; there would be fewer still if AIM needed more money, because AIM had “protected status.”

The protected status stemmed from another move that would have a major impact on the anti-tobacco education programs. A clause known as Section 43 was added to AB 99 to guarantee funding for five medical services programs—MediCal Perinatal Programs, AIM, the Major Risk Medical Insurance Program (MRMIP), CHDP, and the County Medical Services Program. Thus, these programs were guaranteed money “off the top” to fund them in the face of declining revenues; the other Proposition 99 programs were cut to support the “protected” ones. This provision, combined with the overall decline in Proposition 99 revenues because of its success in reducing tobacco consumption, promised to wipe out the anti-tobacco education programs over a period of a few years.

Neither the voluntaries nor Miller noticed the Section 43 language when it was added. When they were later interviewed about AB 99, Miller and Najera both expressed bitterness about Section 43. According to Miller, “The Section 43 crap…we all come to agreement, we divide the money up, we settle it all. The bill goes out to print, and it's before the Legislature, it goes most of the way through the system and Department of Finance said, `Oh, oh, one little thing more. We need to stick in this provision to protect it or the Governor doesn't go along with this deal.' We look at it and it says, `We need to tinker with the numbers to make it come out right. We need to protect some programs.' Okay, do it.”[35] Najera added, “We didn't understand what Section 43 was until

The voluntaries were at a significant disadvantage in staying abreast of important technical details like Section 43, especially compared with the medical care groups, because of the size and depth of their lobbying staffs. Proposition 99 was generating around $500 million a year, making the voluntary health agencies major stakeholders, but they had not expanded their policy analysis capabilities or lobbying presence in Sacramento since the passage of Proposition 99. The devastating long-term effects of Section 43 emerged from policy research and analysis at UC San Francisco.[4]

After the governor signed AB 99, ALA's newsletter announced, “We are pleased to communicate that all the Health Education Programs are in place, functioning and authorized for three more years.”[32] The main virtues of AB 99 were that the sunset date was three years away, and, according to the Los Angeles Times, the Wilson administration had promised Najera that it would not try to divert any more funds for at least the next three years in exchange for the deal.[36] The ALA's optimistic statement, however, masked a different reality. Rather than the status quo that the voluntaries expected when they allowed AB 99 to be handled through the Conference Committee process, AB 99 represented significant damage to Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education programs. In 1991-1992, of the $151 million available in the Health Education Account, only about half ($78 million) was actually going to tobacco prevention programs. The voluntary health agencies had completely capitulated to the medical interests. In doing so, they abandoned their strongest argument: that the Legislature had an obligation to appropriate Proposition 99 Health Education funds for anti-tobacco education efforts as directed by the voters. Instead, they accepted the reality of insider horse-trading over the budget.

The Governor Tries to Kill the Media Campaign

Governor Wilson finally gave the tobacco industry what it wanted in January 1992: he shut down the media campaign.

Although Wilson had included the media campaign in his 1991-1992 budget, he imposed increasingly tight political control over it as his first year in office unfolded. According to Ken Kizer, director of DHS, the Governor's Office immediately wanted the advertisements toned down and

In his budget for the 1992-1993 fiscal year, released on January 10, 1992, Wilson went one step further and eliminated the media campaign entirely.[38] Moreover, rather than waiting for the Legislature to act, the governor had already ordered DHS not to sign the just-negotiated contract with the keye/donna/perlstein advertising agency, which had been going to continue the campaign on January 1, 1992.[39][40]

The media campaign went dark.

Dr. Molly Joel Coye, whom Wilson had appointed to replace Ken Kizer as DHS director, defended the decision to kill the media campaign.[41] Coye was a dramatic change from Kizer. Whereas Kizer had been a strong program advocate and defender, Coye was not; she followed the governor's orders and remained aloof from the tobacco control community. According to Jennie Cook, “Molly was different. You could never get an audience with Molly. She was never available.”[42] Coye vigorously pushed the administration line that the local programs funded by Proposition 99 were a more effective use of resources and that the smoking decrease following the beginning of the media campaign was actually part of a trend that began in 1987 rather than the result of the anti-smoking advertising campaign.[43-45] In an opinion editorial in the Sacramento Bee, Coye claimed that “the revenues from Proposition 99 are being diverted for only one reason: to cope with the worst budget crisis in California's history. …If the tobacco industry is pleased with this temporary shift, it couldn't be more wrong.”[46] In fact, when the media campaign was suspended, the decline in tobacco consumption slowed.

While Governor Wilson justified the decision to eliminate the media campaign by pointing to the state's fiscal crisis, no one in the public health community believed him. Assembly Member Lloyd Connelly (D-Sacramento), the primary legislative force behind the original Proposition 99, expressed a view that was widely held within the public health community: “During the Proposition 99 campaign and the intense negotiations surrounding the implementation legislation, the provisions most virulently opposed by the tobacco industry were those that created the Health Education Account, including the enormously successful TV and radio antismoking ad campaign. Can it be just a coincidence that—after being wined and dined by the tobacco industry last summer—that it is precisely that account which has been gutted? I do not think so.”[20]

The governor was, in fact, more interested in killing the media campaign than in weighing how the money was being spent. At a March 16 hearing on the budget, held by the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Subcommittee on Health, the Legislative Analyst indicated that the proposed diversions were inappropriate uses of the Health Education monies and that only the voters could make that reallocation.[47] The governor then proposed to shift the money to an AIDS testing program, perhaps hoping to enlist the AIDS lobby in the effort to kill the media campaign. In response, the ALA claimed that “the Governor's real agenda was not to fund needed programs but to gut the media campaign in whatever way possible.”[48] Kathy Dresslar, an aide to Assembly Member Connelly, agreed: “The fact that the governor has changed the reason why he wants to divert funds from the media account suggests he is less interested in health priorities than he is in gutting the media campaign.”[20]

In any event, both the governor's action and the justification for eliminating the media campaign effectively implemented the tobacco industry's plan, dating from 1990, to work with a variety of minority groups, hospital groups, the CMA, and business groups to divert money from the media program into other health programs.[49] The tobacco industry publicly endorsed the governor's action: the Associated Press reported that “Tom Lauria of the Tobacco Institute, the industry's lobby, applauded the proposed elimination of a campaign that `focused primarily on ridiculing industry…and basically put smokers in a bad light.'”[50]

In addition to citing the state's fiscal problems as the reason for suspending the media campaign, the administration claimed, without presenting any evidence, that the campaign was a waste of money because it did not work and that it was of “secondary” importance.

These claims about the media campaign's lack of importance and effectiveness were contradicted a few days later when John Pierce, a professor from the University of California at San Diego, released preliminary data from the California Tobacco Survey (a large statewide survey conducted under contract to DHS), of which he was director. Speaking at the AHA Science Writers Conference, Pierce said that the survey results demonstrated a 17 percent drop in adult smokers between 1987 (the year before Proposition 99 passed) and 1990. In 1987, 26.8 percent of adults smoked, compared with 22.2 percent in 1990. Pierce attributed this drop to the combined effects of the tax, educational efforts, and the media campaign.[51][52] Since the media campaign was the only part of the California Tobacco Control Program that was active during most of this period, Pierce identified it as the primary factor in this rapid fall.

Pierce's report made headlines. The San Francisco Chronicle proclaimed, “Anti-Smoking Program Big Hit—But Governor Seeks to Cut It.”[45] Other major newspapers gave the study's results prominent coverage: “California Push to Cut Smoking Seen as Success” (Wall Street Journal); “Anti-Smoking Initiative Called Effective” (Washington Post); “Anti-Smoking Effort Working, Study Finds” (Los Angeles Times); “California Smokers Quitting” (USA Today).[52-55] Rather than claiming credit for this stunning public health success, the Wilson Administration attacked Pierce's result, claiming that the conclusions were overstated.[57][56][57] DHS's new spokeswoman was Betsy Hite, who had been one of the original advocates for Proposition 99 when she was the ACS lobbyist; now she vigorously defended eliminating the media campaign.

Hite pressured TCS staff members to falsify data about the effectiveness of the programs in support of the administration's claim that the media campaign was not responsible for the state's decline in tobacco consumption. Hite told Jacquolyn Duerr, then head of the TCS media campaign, to back up Hite's assertion that the smoking decline had nothing to do with Proposition 99. Duerr and Michael Johnson, the head of DHS's evaluation efforts, and Pierce's contract monitor, refused to comply.[58][59] Duerr wrote Dileep Bal, the head of the DHS Cancer Control Branch (which includes TCS), saying, “I want you to know that this is some of the most unprofessional behavior I have experienced in my state service tenure”; Johnson wrote, “I hope that something can be done very soon to stop this falsification of results.”[59]

The First Litigation: ALA's Lawsuit

Shutting down the media campaign was too much for the ALA to swallow. In 1991 the ALA had been promised that, in exchange for accepting AB 99's diversion of funds, there would be no further diversions for the life of the legislation, which would not expire until June 1994. When asked why the agreements of previous years were not being honored, Kassy Perry, the governor's deputy communications director, responded, “That was last year. This is this year.”[36]

Rather than allowing the media campaign to be shut down, the ALA filed a suit against Wilson and Coye on February 21, 1992, arguing that by refusing to sign the contract with the advertising agency, they had violated AB 99, which said that the DHS “shall” run an anti-tobacco media campaign. Significantly, ALA did not challenge the diversion of funds on

Neither AHA nor ACS joined ALA in its lawsuit, although ANR attempted to file a friend of the court brief. ACS was willing, if asked, to state privately its position that the cuts were illegal and a flagrant violation of the will of the people, but it refused to join in the suit. ACS thought it could achieve more working behind the scenes.[20] This view was surprising, since the evidence to date had indicated that health groups won in public venues and lost behind the scenes.

Jennie Cook, ACS lobbyist Theresa Velo, and AHA lobbyist Dian Kiser met with Bill Hauck, the governor's assistant deputy for policy, and Tom Hayes, the director of finance, while the lawsuit was in progress. Whereas ACS and AHA wanted to talk about the anti-smoking program generally, the administration officials seemed to care only about the lawsuit. According to Cook, “The first item on their agenda was the lawsuit. After we explained that our two organizations were not involved, the mood instantly changed and became much more positive.”[60] Cook, Velo, and Kiser attempted to discuss the merits of the program, but Hauck and Hayes wanted to discuss budget problems. Cook continued, “They expressed concern regarding the media's interpretation that the Governor is proposing this [sic] cuts for the tobacco industry. They asked our organizations to help clarify these erroneous statements.”[60] The ACS and AHA did not do so.

Hauck and Hayes apparently recommended that the ACS and AHA representatives talk to Russ Gould, the secretary of health and welfare. They did so, meeting with Gould and Kim Belshé, the deputy secretary for program and fiscal. (In 1993 Belshé would be named director of DHS, where she would be responsible for implementing Proposition 99. In 1988 she had been a spokesperson for the tobacco industry's No on Proposition 99 campaign.) According to Cook, “We informed them that we are not involved in the pending lawsuit, at which time their apprehensions dissipated.”[61] As Cook reported to the ACS leadership,

Gould explained California's fiscal dilemma and assured us that all accounts were looked into along with the Proposition 99 accounts. The decision was made to preserve only direct service funds (i.e., community-based programs). They felt that while the media campaign is a worthwhile program it does not provide direct services; same for the education and research accounts.

They went into some depth explaining the devastating cuts they have to make and that they are uncomfortable with having to make these choices. They asked for an opportunity to reach out to our organizations to explain

― 199 ―the tight spot that the State is in at this time. Gould offered to attend an ACS Board of Directors to do just that.Finally, we requested that we keep an open channel of communication with the Agency through one knowledgeable individual. They both indicated that Belshe would fulfill that role; Belshe invited us to call her to discuss the issue on an on-going basis.

In conclusion, this meeting was very productive in establishing a direct line of communication with the Health & Welfare Agency.[61]

Administration officials were happy to communicate with ACS and AHA. But the communication did not lead to any policy changes.

When asked in 1998 about ACS's decision not to join the 1992 ALA lawsuit, Cook, who was by then the national chair of the ACS board and the chair of TEOC, said, “Cancer and Heart were still a little timid to get into lawsuits. Lung led the way and I think the fact that Lung won it with no real big problem made the other two feel that, `maybe it's time we spoke up.' It wasn't that we didn't want to, it's just that—the old saying about, `we were using public funds and we felt that that's not what the public gave us money for was to sue the governor.' Today, it's a little different [laughter].”[42] In 1992 ACS was unwilling to confront the Wilson Administration in a public forum where the ACS's high public credibility gave it strength. Cook commented that ACS's preference was to avoid confrontation, to “maneuver it, consider it, talk it out, be diplomatic. What we discovered is where tobacco is concerned, you can't be that way.”[42]

On April 24, 1992, the ALA won in court when Judge James Ford of Sacramento Superior Court ruled that Wilson did not have the authority to take funds appropriated for one purpose and use them for another; Ford ordered that the money be used for the authorized media campaign. The big question following the ALA victory was whether the governor would appeal the Superior Court's decision. An appeal would freeze the status quo and keep the media campaign off the air while the case made its way through the courts—possibly for a year or more.

Wilson had appointed Molly Coye director of health services, effective May 29, 1991. Under California law, she could serve for up to one year before she was confirmed by the Senate. If, however, the Senate did not confirm her by the so-called drop-dead date, she would have to leave office. Because of unrelated controversies, the Senate was taking up the matter of Coye's appointment as the litigation over the media campaign was coming to a head. The AHA, which had declined to join the lawsuit, then entered the world of hardball politics.

The AHA convinced the Senate Rules Committee to hold up Coye's confirmation until the deadline for filing an appeal in the media case had passed. At a tense hearing regarding Coye's confirmation, the administration lined up around fifty witnesses to support her, including the CMA, CAHHS, and many other medical organizations. (ALA and ACS took no position on Coye's confirmation.) In the face of this support, Kiser, the AHA's lobbyist, attended the hearing and read a prepared statement that she and Glantz had written, urging the Senate to delay action on Coye's confirmation.[62] The statement read:

Dr. Coye is responsible for overseeing the Health Education Account, including several key components such as the media campaign, the California tobacco survey, and various grants programs to community-based organizations.

The American Heart Association has serious reservations regarding the way these components are being implemented.

These concerns have led the American Heart Association to seriously consider questioning Dr. Coye's confirmation. However, we would like to suggest a positive alternative and that would be to defer her confirmation until she has had an opportunity to remedy the problems that have been created in the implementation of Proposition 99.[63]

That statement went on to stipulate that Coye “execute the media contract that had been awarded, and see that the contractor can continue the campaign free of political interference.”[63]

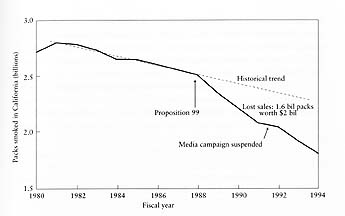

At her May 6 hearing Coye pledged, “I make the commitment and the Governor makes the commitment. We do not plan to appeal the decision.”[64] The governor did not appeal the court decision, Coye was confirmed, the media campaign resumed, and tobacco consumption started to drop again in California. By the end of the 1993-1994 budget period, Californians had consumed 1.6 billion fewer packs of cigarettes (equaling $2 billion in pretax sales) than they would have if historical pre-Proposition 99 consumption patterns had been maintained (figure 13).

The episode demonstrated once more that the anti-tobacco groups exercised the most power in public forums outside of legislative back rooms. In contrast to the tobacco industry and medical interests, which provide substantial campaign contributions to politicians, the health groups get their power from public opinion and public pressure. ALA, which had led the movement to work around the legislative process when it developed Proposition 99, once again succeeded by going outside the Legislature, this time to the courts. AHA solidified ALA's victory by publicly confronting the administration over Coye's confirmation. Program

Figure 13. Impact of the California Tobacco Control Program on cigarette consumption through 1994. Passage and implementation of Proposition 99 was associated with a rapid decline in cigarette consumption in California. During 1991, the year that Governor Pete Wilson took the media campaign off the air and blocked many local programs, the decline stopped. It resumed when the program started up a year later.

The 1992-1993 Budget Fight

In his budget for fiscal year 1992-1993, released in January 1992, Wilson again ignored the deal that he had made with the health groups by diverting the $16 million allocated to the anti-tobacco media campaign into medical care.[38][65] He also proposed to eliminate the school-based anti-tobacco programs.[20] In the first attack on the Research Account, he ignored Proposition 99 and the implementing legislation (SB 1613) by cutting the Research Account from 5 percent to less than 3 percent of tobacco tax revenues. Like the other “temporary” shifts, the ones proposed by the governor in 1992 were part of a continuing downward spiral in the amount of money allocated to Proposition 99's Health Education and Research programs.

The Budget Conference Committee agreed to $80 million of the $123 million allocation for education and research that the governor proposed

The ALA asked its attorney, George Waters, for a formal legal opinion regarding the diversions of Health Education and Research money into medical services. In an extensive opinion that mirrored those offered earlier by the Legislative Counsel, Waters advised the ALA that such diversions were illegal:

We conclude that funds in the Health Education and Research accounts cannot be used to fund health care programs… .

The drafters of Proposition 99 obviously paid a great deal of attention to how the Tobacco Fund would be divided up. The language is very specific. The intent of the drafters, and by extension the intention of the electorate, was to make a fixed percentage of the Tobacco Fund available for specific purposes and specific purposes only.

This conclusion is buttressed by the Voters Pamphlet description of Proposition 99. The Voters Pamphlet is an approved source for the determination of the legislative intent behind a ballot measure. …[and] contains the following analysis of the Legislative Analyst:

The measure requires the revenues from the additional taxes to be spent for the following purposes:

Health Education. Twenty percent must be used for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use, primarily among children, through school and community health education programs.

Given the above, we are reasonably confident that we can set aside in court any attempt to use monies in the Health Education and Research accounts for any purposes other than health education and research.[68] [emphasis in original]

The ALA chose not to sue. Instead, it made another deal.

On July 15, 1992, ten senators and twenty-seven assembly members signed a letter to Senator Alfred Alquist (D-San Jose), the Budget Conference Committee chair, protesting the committee's action in redirecting Health Education and Research monies to medical service programs. According to the letter, the redirection of these funds violated the public trust, violated the constitutionally protected statutory provisions of Proposition 99, and would disrupt the programs wrongfully receiving the money when it had to be returned to appropriate uses. On July 17, however, the Budget Committee reaffirmed its decision to divert the money.[69]

In opposing the diversions, the health groups created a procedural problem for the forces seeking to dismantle the Health Education and Research programs. This issue had not come up in earlier budget bills because the health groups supported the diversions; the associated legislation, passed by lopsided majorities, had gone unchallenged in the courts. The ALA had gone to court once—over the media campaign in 1992—and won. This time, the health groups were opposing the diversions.

On August 7, 1992, Peter Schilla of the Western Center for Law and Poverty wrote to Assembly Speaker Willie Brown to urge him to separate the Proposition 99 diversions from the remainder of the budget on the grounds that it would be difficult to get a four-fifths vote on the entire state budget.[70] The budget needed only a two-thirds vote to pass, and Schilla and others were arguing that the money could be diverted because of the language in the initiative that permitted the Legislature to enact amendments to Proposition 99 by a four-fifths vote, so long as the amendments were “consistent with its purposes.” (Critics were arguing that any reductions in the Health Education and Research programs below 20 percent and 5 percent would not be “consistent with the intent” of the initiative.) Brown followed Schilla's advice, removing the Proposition 99 accounts from the budget bill and placing them in separate bills that would be easier to pass under the four-fifths requirement.[71]

In the end, the bills did not come to a vote. The health groups agreed to a last-minute compromise in which most funding for the media campaign, competitive grants, and schools was restored. The LLA programs, however, took a major cut—from $24 million to $12 million. According to Najera, “In assessing where to amputate, the politicians had to make flash comparisons of the relative return between the different parts of the anti-tobacco program. One strong argument on cutting local leads was that much of the county funds were already spent on direct medical services, and thus the loss of local funding was diminished by whatever amount went to non-tobacco services.”[69] From the standpoint of a county's total revenues, this statement might have been true. But the cuts to the LLA would not be offset by money for local medical services. Moreover, the requirement that one-third of LLA money be diverted into the CPO medical services program remained, which amplified the effects of the LLA cuts. The local programs would be forced to absorb large cuts just as they were hitting their stride.

The LLAs were eventually rescued because of the fallout from an unrelated political battle between the Legislature and the governor over funding for community colleges. It turned out that the Legislature did not

The attacks on the LLA budgets in both 1991 and 1992, along with the 1992 attack on the media campaign, were consistent with the tobacco industry's strategy to reduce Proposition 99's effectiveness. The LLAs were costing the tobacco industry time and money with their local ordinance work. Further, by educating minority communities about tobacco issues and bringing them into the tobacco control network, the LLAs and the competitive grants were weakening an industry power base.

The erosion of Proposition 99 continued.

Positioning for 1994

The continuing failure of CHDP and CPO to provide tobacco use prevention services was becoming an increasing irritant for tobacco control advocates. CPO was, in fact, mainly being used to get federal matching funds. At the county level, CPO programs were supported from two sources: Proposition 99 Health Education Account money and federal matching funds. This money had to be used exclusively for outreach; none could be used to deliver services. Counseling services, which included smoking cessation, did not qualify for federal matching funds.[73] Dr. Rugmini Shah, the director of the state-level DHS Maternal and Child Health (MCH) program, which administered CPO, defined outreach as “finding individuals who are not accessing services and bringing them into the service area system.” Cessation classes could not be funded because “the women are already in here for the classes, so it's not outreach.”[74] Thus, any Proposition 99 dollars that generated federal matching dollars could not be used for tobacco-related services.

At the November 1992 TEOC meeting, the CPO program was on the agenda. TEOC was concerned that the money was being used illegally to meet a federal match for perinatal outreach services and that the federal rules prohibited the use of state matching funds for any anti-tobacco activities.[75] At the January 1993 TEOC meeting, MCH was able to tell TEOC that $7 million of the Health Education dollars given to MCH went to the federal matching program and that only nine of the fifty-eight counties provided cessation training components.[76] By the March 1993 meeting,

In contrast to their earlier positions, the health groups and their representatives on TEOC were now openly challenging the appropriateness of using Health Education funds for medical services. In submitting the 1993-1995 Master Plan for California's Tobacco Control Program to the members of the Legislature, Cook and Martin wrote to the legislators on behalf of the TEOC:

We are particularly alarmed by the fact that funding for the CHDP Program continues to expand, yet we have little idea of what CHDP is doing with these funds and no evaluation of its impact. Physicians in CHDP respond to three vague and inexact questions related to tobacco use, second-hand smoke and counseling. The data generated through this protocol is essentially useless. Improving the protocol, which the California Department of Health Service has indicated its willingness to do, might help. However, to date as far as we can ascertain, despite the large funding provided to it, the CHDP Program has contributed nothing to tobacco control.

In addition, the one-third of the money set aside in the Local Lead Agency grants for tobacco-related Maternal and Child Health activities is being used for outreach, without any tobacco education component, despite the legal requirement in Proposition 99 that funds be used only…for programs for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use.[77] [emphasis added]

Tobacco control advocates were beginning to be openly critical of the diversions from the Health Education and Research Accounts to medical services.

Coye resigned as DHS director in September 1993. On November 9 the governor named S. Kimberly Belshé as her successor. Although Belshé had been working in the administration since 1989, she was not a physician, as both Coye and Kizer had been. At thirty-three, she had worked primarily in public relations. More alarming to tobacco control advocates was the role that Belshé had played in 1988 as the tobacco industry's Southern California spokeswoman against Proposition 99.[78] Belshé defended her past association with the tobacco industry, saying that she had opposed Proposition 99 for fiscal reasons.[79] Her proposed appointment did little to reassure advocates of the Health Education and Research programs that they would receive the protection for which Kizer had fought. Her lack of medical credentials notwithstanding, the CMA supported her appointment.[80]

AB 99 continued in force for the 1993-1994 budget year, and the governor's budget for 1993-1994 contained no major raids on the Health Education Account except for those required by Section 43. Section 43, however, led to three cuts to the anti-tobacco program during 1993-1994. Tax revenues ultimately fell by 8 percent between 1992-1993 and 1993-1994, but expenditures for anti-tobacco education fell by 31 percent.[81] The discrepancy between the funding allocation in Proposition 99 and the actual expenditure of funds continued to widen.

While turning a blind eye to the needs of the Tobacco Control Program, the Legislature acceded to pressure from breast cancer research advocates to increase the tax on cigarettes by two cents a pack. The new tax funded a breast cancer research program administered by the University of California similar to the Tobacco Related Disease Research Program. The tobacco industry did not seriously oppose this tax. Aside from the modest increase in price, it did nothing to reduce tobacco consumption. It did, however, offer some political cover for Speaker Brown, Governor Wilson, and the CMA when they were criticized for failing to implement Proposition 99 as the voters intended.

Even though Proposition 99 created a large constituency in the field through the LLAs and local coalitions, these people and organizations were not involved in the dealings in Sacramento throughout AB 99. The Sacramento lobbyists made only a minimal effort to engage these new players in the legislative process, and the local activists were preoccupied with getting the anti-tobacco program up and running. According to ANR co-director Robin Hobart,

There was still some sort of incursions into the Health Education Account, but they still, at that point, seemed small and not worth spending the kind of political capital that you would have to spend to deal with it. We were busy passing hundreds of local ordinances by that time in California and emphasized our role as helping the local lead agencies get their coalitions in order and start working on grassroots organizing around local ordinance campaigns. We were probably doing trainings about every other month, especially during the first two years, sometimes multiple times in a month. That's where a lot of our energy and emphasis was going.[82]

But the people in the field who were implementing the Health Education program were growing tired of the way the money was being taken away and tired of the rules under which they were forced to operate. Meanwhile, no anti-smoking components had been added to CHDP, CPO, or any other health service programs. Moreover, no evaluations were conducted

The Governor Kills the Research Account

In 1989 the Research Account had been authorized by separate legislation, SB 1613, which did not expire until December 31, 1993. The governor had made several proposals to reduce funding for tobacco-related research in his budgets, but the Research Account did not surface in the battle over AB 99, which dealt only with the Health Education Account and the medical services accounts. In 1992 and 1993, Wilson tried to cut the Research Account but withdrew the proposals when it became clear that they lacked support in the Legislature.

As SB 1613 stipulated, the University of California managed the Research Account using a peer review process modeled on the National Institutes of Health. Applicants from qualifying public and nonprofit institutions (not just the University of California) submitted proposals for research projects that were judged and graded by committees of outof-state experts. The university funded the projects in order according to their grades.

The university chose to define “tobacco-related research” broadly. As a result, most of the money went to traditional biomedical research with little or no direct connection to tobacco.[83] The university's failure to concentrate more directly on tobacco angered tobacco control advocates, who wanted a more tobacco-specific program. Some of the research was very closely tied to tobacco, however, and became the target of attacks by the tobacco industry, its front groups, and their allies.

In particular, Glantz had won a grant in the first year of the program to study the tobacco industry's response to the tobacco control movement. This research had evolved into a detailed analysis of how the tobacco industry was working to influence the Legislature as well as how Proposition 99 was being implemented. With funding from this grant, Glantz and his coworkers published a series of monographs detailing campaign contributions to members of the Legislature and other politicians as well as documenting the erosion of Proposition 99 funding for anti-tobacco education.[3-4][81][84-85] The monographs highlighted the diversions of Health Education Account funds to medical services and the long-term implications of Section 43.

These reports infuriated the tobacco industry, the Legislature, and

The process of reauthorizing the Research Account proceeded without much public controversy during 1993. There was some sparring between health advocates and university officials in an attempt to force the university to focus more specifically on scientific and policy issues that were directly related to tobacco, but the university successfully opposed this effort. Before SB 1613 expired on December 31, 1993, the Legislature had unanimously passed SB 1088 to continue the program until 1997. The governor surprised everyone when he vetoed the bill, stating, “This program should not be extended for four years when expenditure authority for all other Proposition 99 funded programs pertaining to health and research will be reviewed during the 1994 legislative session. This program should be reviewed and re-evaluated in the context of all Proposition 99 funded programs and activities to insure the most effective use of those funds.”[87]

Wilson's veto effectively shut down the research program. Many were suspicious that Wilson's action was making good on Brown's earlier threat to punish the university if it did not quiet Glantz. Ironically, by the time Wilson killed the Research program, Glantz was being funded by the National Cancer Institute, not Proposition 99.

The governor's veto also meant that the funds allocated for research in the first six months of 1994—$21 million—suddenly became available for other programs. The Research Account money was soon put into play in a manner that would make it easier during the next legislative fight over Proposition 99 authorization to divert the funds into medical services.

Conclusion

As memories of the Proposition 99 election faded, legislators could more readily ignore public opinion and the public will unless the voluntary health agencies and other guardians of Proposition 99 found ways to activate and use public opinion. Instead, the groups attempted to play the insider game and were not successful. For five years tobacco control advocates, using an insider strategy, had tried to protect their programs against the tobacco industry, the CMA, other medical service providers, the Western Center for Law and Poverty, and the governor. This approach of working within the Legislature meant abandoning the health groups' most potent weapon: public opinion. In general, the years of AB 75 and AB 99 were characterized by a series of struggles testing the resolve of the guardian groups and by their general unwillingness to fight back.

During the period 1990-1994 the issue of money for health education and research had increasingly been framed as a budget battle, which was damaging for the voluntary agencies trying to maintain these programs. California's economic recession provided a cover for those who wanted to take the money out of the Health Education Account. When Assembly Member Richard Katz (D-Panorama City), a tobacco control advocate in the Legislature, was asked in 1997 if this had really been a budget fight, he said “not really”:

I think all along they [the administration] wanted to help big tobacco. I think it's obvious from the last couple of years in terms of their desire to muzzle or censor some of the advertising that Health Services had done. I think in their

― 21o ―desire to screw with the research that the University of California does that they have been fronting for big tobacco. The budget issue made it convenient. In terms of the overall budget, it's not a lot of money. …I don't know who came up with it, it was a very, very clever strategy that helps big tobacco under the guise of providing indigent health care.[88]

In agreeing to the use of Health Education funds for medical services, the voluntary health agencies made this problem worse for themselves. Rather than standing for implementation of Proposition 99 as enacted by the voters, the question became whether the diversions were too large—hardly one that would rally public support.

The one major move outside the Capitol—when ALA filed a lawsuit in 1992 over the media campaign funding—did generate publicity and protection for this program. Significantly, the lawsuit was based on the governor's refusal to implement AB 99 rather than on the broader issue of AB 99's inconsistency with Proposition 99. As parties to the AB 99 compromise, insiders at the ALA were not yet ready to make the more fundamental policy argument: that the governor and the Legislature had violated the voters' mandate and acted illegally in diverting Health Education Account funds into medical services.

The environmental movement, through the Planning and Conservation League and Gerald Meral, had been instrumental in creating Proposition 99. As part of the deal made in 1987 when Proposition 99 was being written, the Public Resources Account was to receive 5 percent of the Proposition 99 revenues for public lands and resources. In 1990 the environmentalists decided to increase their share of revenues by securing part of the Unallocated Account for environmental purposes. They passed Proposition 117, which set up protections for California mountain lions and directed that funding from this program come from the Unallocated Account, so environmental programs began to receive more than 5 percent of tobacco tax revenues. Throughout the fights to save the Health Education and Research programs, neither the Legislature nor the governor touched the Public Resources money—for medical services or anything else. The tobacco industry, after all, had no interest in diverting money from the Public Resources Account. In March 1992 John Miller observed, “[While] health education is more central to the initiative than the 5 percent that went to the environmental stuff,” the Legislature “realized they could kick the hell out of the voluntary health organizations. …they don't have the political clout of the Sierra Club.”[89] Ironically, voluntary health organizations such as AHA, ACS, and ALA

The difference between these health organizations and the environmental groups, however, was in their willingness to confront politicians in the public arena; once Proposition 99 passed, the voters—the grassroots—were not involved. Proposition 99 had become a legislative game. As an LLA staff member and then as co-director of ANR, Robin Hobart conceded that, especially from Tony Najera's perspective, “the ends justified the means” in the early phase. She explained,

If you have to give up a little bit to get relatively decent funding, then that was an okay deal to make. I don't know if he [Najera] was wrong about that or not the first year…but there was never really an attempt at any point in time to really seriously mount grassroots support for the reauthorization issue—the authorization issue and then the reauthorization issue. It always really was done inside Sacramento. We'd send out action alerts and the local units of the Lung and Heart and Cancer would send out Action Alerts, but it wasn't really a serious grassroots campaign. That doesn't really equal a serious grassroots effort.[82]

In 1989 the Legislature and the governor did not harm the Health Education and Research programs because the election was still close enough for the will of the voters to be felt. In subsequent years, the election would fade in the legislative and public memory. Without other efforts to bring public attention to the Proposition 99 expenditures, the preferences of the skilled, the experienced, and the powerful in the legislative insider game asserted themselves.

Between passage of Proposition 99 and the end of the 1993-1994 budget period, a total of $190 million that voters had allocated to anti-tobacco education was diverted into medical services. Despite these cuts, the anti-tobacco education program continued to depress tobacco consumption in California. While impressive, this reduction in tobacco consumption would likely have been even greater had there been no program disruptions (such as suspending the media campaign) or funding diversions.

Notes

1. Department of Health Services. “Research data shows significant drop in tobacco usage since enactment of California's tobacco education campaign” . Press release, October 30, 1990.

2. Cook J. “AB 75 update. Report to the Board of Directors, American Cancer Society” . February 14, 1991.

3. Begay ME, Glantz SA. Undoing Proposition 99: Political expenditures by the tobacco industry in California politics in 1991. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, 1992 April.

4. Begay ME, Traynor M, Glantz SA. Extinguishing Proposition 99: Political expenditures by the tobacco industry in California politics in 1991-1992. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1992 September.

5. Scott S. “Interview with Edith Balbach. September 18, 1996” .

6. Beerline D. “Interview with Edith Balbach. September 26, 1996” .

7. Miller J, Najera T. “Memo to Carolyn Martin. December 13, 1990” .

8. American Lung Association, California Association of Hospitals & Health Systems, California Medical Association, California Planners and Consultants, California Schools Boards Association, County Supervisors Association of California, Service Employees International Union, Western Center for Law and Poverty. “Letter to Phil Isenberg. January 7, 1991.”

9. Martin C. “Comments on manuscript. 1998 October” .

10. Martin C, Breslow L, Dyke P, Weidmer CE, Cook J. “Tobacco Education Oversight Committee press conference remarks. January 23, 1991” .

11. California Medical Association. “Summary of recommendations. Report to Council from the Commission on Legislation. November 10, 1990” .

12. Strumpf IJ. “Memo to Scientific Advisory Panel on Chest Diseases re: Resolution 213-96, Anti-Tobacco Education and Research. February 5, 1996” .

13. Michael JD. “Letter to Lester Breslow. January 22, 1990” .

14. Plested WG. “Letter to the Honorable Robert Presley. July 14, 1989” .

15. Howe RK. “Tobacco education and socialized medicine” . California Physician 1989 December; 48-49.

16. Michael J. “Interview with Michael Traynor. April 20, 1993” .

17. California Medical Association. “Minutes of the 746th Council. September 14, 1990” .

18. Tobacco Institute (?). “California anti-tobacco advertising program. November 1, 1990” . Bates No. 50779 3734/3735.

19. State of California, Legislative Analyst's Office. “Analysis of the 1991-1992 budget.” Sacramento, February 6, 1991.

20. Skolnick A. “Court orders California governor to restore antismoking media campaign funding” . JAMA 1992;267:2721-2723.

21. State of California, Legislative Analyst's Office. “Analysis of the 1994-1995 budget bill.” Sacramento, 1994.

22. American Lung Association. “AB 99 (Isenberg)—active support. Capitol Correspondence” 1991 March 26.

23. Hagen R. “Executive notice. March 21, 1991” .

24. Page BI, Shapiro RY. The rational public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

25. Oglesby MB, Mozingo R. “Memo to J. W. Johnston re: California anti-smoking advertising. January 24, 1991” . Bates No. 50760 4050.

26. Verner KL. “Memorandum to T. C. Griscom re: California's anti-smoking campaign funding. January 29, 1991” . Bates No. 50775 5351-5354.

27. California Medical Association. “Report to the Executive Committee from the Prop 99 Funding TAC (ratified by the Board of Trustees, July, 1991). June 14, 1991” .

28. Gregory BM. “Letter to Diane E. Watson. June 13, 1991” .

29. Gregory BM. “Letter to Phil Isenberg. June 27, 1991” .

30. Gregory BM. “Letter to Elizabeth Hill. March 10, 1992” .

31. Western Center for Law and Poverty, California Medical Association, California Nurses Association, California Association of Hospitals and Health Systems. “Memo to AB 99 Conference Committee staff working group. June 30, 1991” .

32. American Lung Association. “Capitol Correspondence.” 1991 July.

33. Kiser D, Muraoka S, Velo T, Najera T. “Memo to all interested parties, Proposition 99 Health Education Account. June 17, 1991” .

34. AB 99 Conference Committee. “AB 99: Budget related issues for resolution. June 30, 1991” .

35. Miller J, Najera T, Adams M. “Interview with Michael Traynor. June 20, 1995” .

36. Weintraub D. “Heat put on Wilson over anti-smoking funds” . Los Angeles Times 1992 February 21;A3.

37. Warren J, Morain D. “Bid to dilute anti-smoking effort revealed” . Los Angeles Times 1998 January 21.

38. State of California, Office of the Governor. Governor's budget 1992-1993. January 1992.

39. American Cancer Society. Memo to unit executive directors from Ron Hagen. Executive notice. January 23, 1992.

40. Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights. “Prop 99 $$ slashed: Media campaign killed already! Action Alert, January 22, 1992” .

41. Russell S. “Health director explains governor's “checkup” insurance plan” . San Francisco Chronicle 1992 January 10;A8.

42. Cook J. “Interview with Edith Balbach. March 19, 1998” .

43. Lucas G. “Demos assail Wilson plan to cut funds for anti-smoking drive” . San Francisco Chronicle 1992 January 23;A15.

44. Gray T. “Wilson's plan to shift funds disguises tax hike, critics say” . Sacramento Bee 1992 January 26;A3.

45. Russell S. “Anti-smoking program big hit—but governor seeks to cut it” . San Francisco Chronicle 1992 January 15;14.

46. Coye MJ. “A temporary diversion of the tobacco tax” . Sacramento Bee 1992 February 18;B7.

47. Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Subcommittee. “Agenda. March 16, 1992” .

48. American Lung Association. “Media campaign suit update” . Capitol Correspondence 1992 June;1-3.

49. Malmgren KL. “Memorandum to Samuel D. Chilcote, Jr. April 18, 1990” . Bates No. TIMN 298437/298420W.

50. Grubb K. “Smoking program. Associated Press, 1992 January 23” .

51. Pierce JP. “Evaluating Proposition 99 in California. Speech: American Heart Association, Nineteenth Science Writers Forum. January 12-15, 1992” .

52. Winslow R. “California push to cut smoking seen as success” . Wall Street Journal 1992 January 15;B1.

53. Matthews J. “Anti-smoking initiative called effective” . Washington Post 1992 January 19.

54. Zamichow N. “Anti-smoking effort working, study finds” . Los Angeles Times 1992 January 15.

55. “California smokers quitting” . USA Today 1992 January 15;D1.

56. “State set to scrap anti-smoking TV ads” . Los Angeles Times 1992 January 16;B8.

57. “State study lauds anti-smoking drive” . San Francisco Examiner 1992 January 25;A5.

58. Duerr J. “Memo to Dileep Bal. January 29, 1992” .

59. Williams L. “Officials: Wilson undercut TV ads on smoking” . San Francisco Examiner 1996 December 22;A1.

60. Cook J, Velo T. “Memo to Ron Hagen. February 27, 1992” .

61. Cook J, Velo T. “Memo to Ron Hagen, Sharen Muraoka, and George Yamasaki, Jr., Esq. April 1, 1992” .

62. Skolnick A. “American Heart Association seeks to delay state health department director's confirmation” . JAMA 1992;267:2723-2726.

63. Kiser D. “Testimony to California Senate Rules Committee. April 22, 1992” .

64. Matthews J. “Smoking ads revived” . Sacramento Bee 1992 May 7;A3.

65. Dresslar T. “Tobacco industry slashes away at tax” . San Francisco Daily Journal 1992 May 4.

66. Najera T. “Memo to Scarcnet. July 15, 1992” .

67. Russell S. “Battle brewing over plan for tobacco tax” . San Francisco Chronicle 1992 July 29;A21.

68. Waters G. “Letter to Tony Najera. June 23, 1992” .

69. American Lung Association. Capitol Correspondence. July 17, 1992.

70. Schilla P. “Letter to Willie Brown. August 7, 1992” .

71. Najera T. “Memo to the Prop 99 anti-redirection coalition. August 12, 1992” .

72. Hayes TW, Hordyk D. “Letter to Alquist et al. October 1, 1992” .

73. Department of Health Services. “Federal Financial Participation (FFP) guidelines for Maternal and Child Health (MCH) programs. Sacramento, July 1, 1993” .

74. Shah R. “Deposition of Rugmini Shah. Superior Court of the State of California, County of Sacramento, 1994. Case No. 379257” .

75. Tobacco Education Oversight Committee. “Minutes. November 16, 1992” .

76. Tobacco Education Oversight Committee. “Minutes. March 29, 1993” .

77. Martin C, Cook J. “Letter to California State Legislators. February 23, 1993” .

78. Green S. “Wilson taps former spokeswoman for tobacco industry as state health chief” . Sacramento Bee 1993 November 10.

79. “Cigarette tax funds grabbed” . San Francisco Examiner 1994 March 13;B1.

80. Skolnick A. “Antitobacco advocates fight “illegal” diversion of tobacco control money” . JAMA 1994;271(18):1387-1390.

81. Begay ME, Traynor MP, Glantz SA. The twilight of Proposition 99: Reauthorization of tobacco education programs and tobacco industry expenditures in 1993. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, March 1994.

82. Hobart R. “Interview with Edith Balbach. July 25, 1996” .

83. Glantz SA, Bero LA. “Inappropriate and appropriate selection of “peers” in grant review” . JAMA 1994;272(2):114-116.

84. Begay ME, Glantz SA. Political expenditures by the tobacco industry in California state politics from 1976 to 1991. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1991 September.