Two Different Models

Although the voluntary health agencies had insisted that health education programs focus specifically on tobacco issues, the final legislation was permissive about what could be done with Proposition 99's Health Education Account money. According to the final language of AB 75, the agencies were to provide “preventative health education against tobacco use.” The bill broadly defined what such education might be. It included “programs of instruction intended to dissuade individuals from beginning to smoke, to encourage smoking cessation, or to provide information on the health effects of tobacco on the user, children, and nonsmokers. These programs may include a focus on health promotion, disease

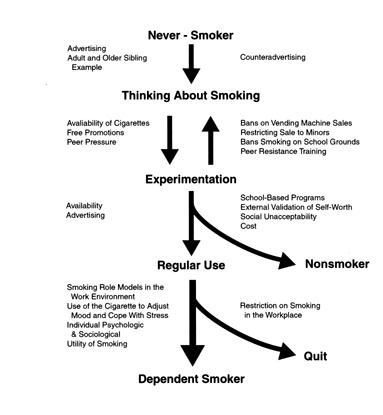

DHS chose to develop a tobacco-specific program based on a model for tobacco control developed at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).[2] According to this model, tobacco use, especially the adolescent progression to adult smoking, was the result of a specific and identifiable set of influences—including the tobacco industry's promotional activities (figure 6). The program sought to break the chain of events which led people to smoke or continue smoking. The NCI model guided program planners in designing tobacco interventions for delivery through four channels—health care settings, schools, community groups, and worksites—using one of three types of programs: mass media, policy, or direct program services. The first comprehensive plans from local health departments used a slightly modified version of this model.

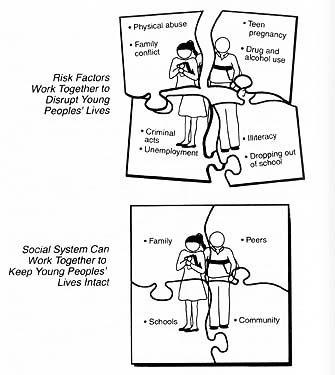

In contrast, CDE simply incorporated the tobacco money into existing school-based programs designed to deal with the factors that put children “at risk” for using illegal drugs and alcohol.[3][4] In the “risk factor” approach, children who have problems in their own lives or with family, school, peers, or the community are considered at risk (figure 7). This approach seeks to enhance protective factors for these youth through the following specific activities:

- Promoting bonds to family, school, and positive peer groups through opportunities for active participation.

- Defining a clear set of tactics against drug use.

- Teaching the skills needed to learn the tactics.

- Providing recognition, rewards, and reinforcement for newly learned skills and behaviors.[5]

With the advent of Proposition 99, tobacco was added to this model because it was considered a “gateway” drug to the use of other drugs. CDE, citing data showing that youth tend to use drugs such as tobacco,

Figure 6. The National Cancer Institute's model of the factors influencing tobacco use. The model of tobacco uptake is linear and offers specific points of intervention. The DHS tobacco control program is based on this model. Source:National Institutes of Health, Strategies to control tobacco use in the United States: A blueprint for public health action in the 1990s (Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1991), 23.

alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs in a predictable sequence, concluded that “the nature of multi-drug use indicates that preventive efforts should not be targeted to any single drug.”[5]To curb the use of tobacco, along with other substance use, schools were urged to concentrate on alleviating the factors that put a child “at risk.”

Figure 7. The CDE risk and protective factors model of tobacco and substance abuse. The model is diffuse and does not offer specific intervention points that can be coordinated with community-based tobacco prevention programs. Source: California Department of Education, Not schools alone (Sacramento: California Deparment of Education, 1991), 2-3.