The Fake Cop Fiasco

The tobacco industry's polling data did not suggest that the theme of cigarette smuggling and crime would have a major influence on voters' opinions. Only 32.6 percent of those polled thought that Proposition 99 would lead to an increase in crime.[42] Still, according to Raimundo, CAUTI's task was to move the Proposition 99 debate away from the health issue.[29][47] And when the tobacco industry began its advertising blitz in mid-August, the crime theme worked especially well. In addition, very early in the campaign, CAUTI secured the endorsements of the California Sheriffs' Association and the California Peace Officers' Association, two organizations that gave credibility to the tobacco industry's claim that the tobacco tax would result in cigarette smuggling.

In August and September, CAUTI's most effective commercial showed an undercover police officer stating that if Proposition 99 passed, he would have to spend all his time chasing cigarette smugglers and that the illegal bootlegging would lead to a massive crime wave. He also claimed that the money obtained from cigarette smuggling would be used to buy guns and drugs. After the tobacco industry's August media blitz on cigarette smuggling and crime, support for Proposition 99 began to decrease. The tobacco industry was surprised at the success of this campaign, but the success had a downside. As Raimundo observed,

We were so successful, the success blinded us to the downsides of sticking on an issue too long. And as a result I think it gave the other side time to rally a response. But we caught them off guard on the crime issue. They did not

― 69 ―anticipate that we would drive it so hard, and they didn't anticipate that the public would respond to it as much as they did. …The best world for me as communications director for this campaign would have been to stay on it for two, three weeks, catch them off guard, they're scrambling to come up with a response, and by the time they come up with a response, we're already on to a different issue. We're talking about the doctors' rip-off. So when the reporters come to us and say, “They just held a press conference with [Attorney General] John Van de Kamp saying it's a bunch of baloney about the crime issue,” we can say, “That's not the issue here; the issue is the doctors' rip-off.” I mean we'd just do our spin-doctoring on the campaign as much as possible.[29]

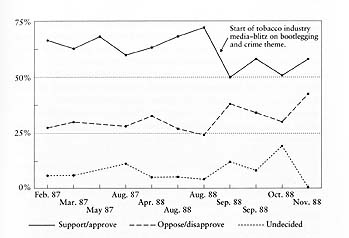

Charlton Research confirmed the decline in support for Proposition 99 in a memorandum to Nicholl. The measure's 27-point lead in April (61 percent for, 34 percent against) was down to a 13-point lead (51 percent for, 38 percent against).[48] On September 22, 1988, another California Field Poll showed that voter support for Proposition 99 had sharply dropped—from 72 percent in August to 58 percent (figure 2).[49]

Public support for Proposition 99 through the election campaign. Support for the initiative remained high before the tobacco industry began its advertising campaign against the initiative. But despite a massive campaign against the initiative by the tobacco industry, support never dropped below 50%. Proposition 99 passed with 58% of the vote. Source: M. P. Traynor and S. A. Glantz, California's tobacco tax initiative: The development and passage of Proposition 99, J Health Policy, Politics and Law 1996;21(3)543-585. Adapted with permission of Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law

The Coalition nonetheless benefited from several key events in late August and early September, which helped slow and ultimately stop Proposition 99's decline in support. Attorney General John Van de Kamp released a report based on state and federal data showing that cigarette smuggling was negligible even in states with high tobacco taxes. Van de Kamp criticized CAUTI's advertisements, calling them “a scare tactic of the worst and baldest kind. …[and] utter nonsense, fabricated by people who represent the tobacco industry.”[50] As a result of this and other Coalition efforts, the two law enforcement associations dropped their opposition to Proposition 99 and took a neutral position.[51][52] The report and Van de Kamp's position gave the Coalition and Proposition 99 free media coverage and damaged the tobacco industry's most effective campaign argument.

Nicholl also discovered that the undercover cop who appeared in the tobacco industry's advertisement, Jack Hoar, actually had a desk job at the Los Angeles Police Department and was a part-time actor. In spite of this, Hoar had signed a sworn affidavit, which he submitted to KGO-TV in San Francisco, declaring “under perjury and the penalties therein” that he was not an actor.[53] More important, in the movie To Live and Die in LA Hoar had played a criminal who killed two secret service agents and spit a chaw of tobacco on one of the dead bodies. Nethery described how the Coalition had stumbled onto this information:

Jack [Nicholl] was at a party one night and…the topic was 99, and these ads came up, and one of the actors said, “Oh. I know that guy.” So Jack's antenna just went right up, and we found out immediately that this guy had been in movies, he was a cop, he was assigned to the studios for security. Once in a while they need a cop quick, they'd drag him in. Well, one thing led to another, and he had finally gotten film credits on this movie, To Live and Die in LA.

Jack rushed out that night, rented the movie, and the next day we were talking to everybody in the state practically, but we were talking and trying to figure out what to do. We had the evidence that this was a lie.

We had a written affidavit to KGO in Jack Hoar's handwriting, and so…I approached some of the lawyers involved with the Cancer Society, and they said, “You'll just get your ass sued off…you can't dare touch it. Can't use it any way, shape, or form.” Well, Sid Galanty, and here's where he really earned his money, he says, “Bull.” He says, “That's news.” He said, “We'll send it to the news media.” And we made up enough for every TV station in the state….

Basically we showed the written statement to KGO, we showed clips from the tobacco spots, and then we showed clips from To Live and Die in LA, including the credits with Jack Hoar. …The TV people just blew them out of

― 71 ―the water on that. And within a day they were gone. …They pulled those ads so fast you couldn't believe it.[23]

The Coalition held press conferences throughout the state, distributing the affidavit and showing the industry's commercial and a clip of Hoar's scene in the movie. Television, radio, and newspaper press coverage of the event saturated every media market in California.

CAUTI tried to argue that Hoar was not a full-time actor and that the desk job was only temporary. As Raimundo explained,

They [the proponents] used heavy-handed techniques, just as the tobacco industry has over the years. I don't want to say they lied, but they certainly manipulated facts in a way that was untruthful. …What they did was, they take a set of facts and then miscast what those facts represented. The perfect example of that was when they had Jack Hoar,…they said he was an actor, he's not a cop. And that was horseshit! He was an undercover cop temporarily on the desk assignment in LA. He's a Los Angeles police sergeant. He had only acted in two bit parts in his entire life, and didn't have enough time to have a Screen Actors Guild card. He was not an actor. And if you watch To Live and Die in LA, I guarantee you he was no actor. If you watch our commercials, he's not much an actor… .It was like he was like a stiff cop, because that was what he was: he was a stiff cop.[29]

But it was too late. The plausibility of the bootlegging and crime argument was destroyed and CAUTI stopped running the undercover cop commercials. The Coalition damaged the credibility of the theme and at the same time highlighted the tobacco industry's misleading campaign tactics.[54]

On November 2, less than one week before the election, the Coalition and Proposition 99 gained additional positive media coverage. Dr. Ken Kizer, Governor George Deukmejian's director of the Department of Health Services (DHS), released a report at a press conference organized by the Coalition which included an examination of the financial cost of smoking and smoking-related deaths in California in 1985. The total economic burden to Californians during that year totaled more than $7.1 billion—$4.1 billion for direct medical costs, $2.2 billion for lost future earnings due to premature death, and $800 million for smoking-caused lost productivity.[55] Because the governor had recently announced his opposition to Proposition 99, Kizer was quick to state that he was not advocating support for Proposition 99, but simply presenting DHS findings. CAUTI responded, “This was obviously timed to be released in the final week of a political campaign. If the timings and the motivations

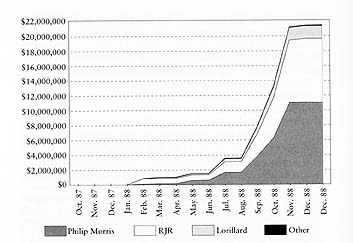

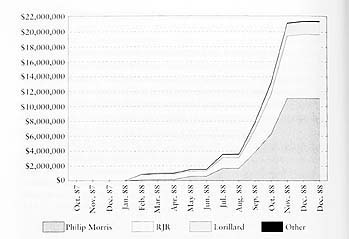

By election day, the tobacco industry had spent $21.4 million on the campaign, compared with the Coalition's $1.6 million (figures 3 and 4).[57][58] The use of free media, the Fairness Doctrine, coordinated statewide press conferences, and local volunteers were all invaluable to the campaign. In addition, the undercover cop fiasco, the Attorney General's report, and the dropped opposition of law enforcement groups all contributed to undermining the tobacco industry's bootlegging and crime theme. The release of the DHS report in the final days of the campaign also helped. While the Coalition campaign was smaller than the tobacco industry's campaign, it was large enough to permit the Coalition to communicate these messages effectively to California voters.

Figure 3. Expenditures to oppose Proposition 99. Virtually all the $21.4 million spent to oppose Proposition 99 came from the tobacco industry (Other = Brown and Williamson Tobacco Company, Smokeless Tobacco Council, Tobacco Institute, and individual contributions). Source: M. P. Traynor and S. A. Glantz, California's tax initiative: The development and passage of Proposition 99, J Health Politics, Policy, and Law 1996;21(3):543-585. Adapted with permission of Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law

Figure 4. Contributions received by the Coalition for a Healthy California to support Proposition 99. Despite expenditures of only $1.6 million, the Coalition successfully passed Proposition 99. The health groups contributed 45%; the medical groups, 40%; environmental groups, 5%; and others, 9%. Source: M. P. Traynor and S. A. Glantz, California's tax initiative: The development and passage of Proposition 99, J Health Politics, Policy, and Law 1996;21(3):543-585. Adapted with permission of Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law

On November 8, 1998 the voters of California passed Proposition 99 with 58 percent of the vote.[59]