The Philip Morris Memo

One of Wilson's major responses to the criticism that he was pro-tobacco had always been that he took no direct campaign contributions from the tobacco industry. This claim ignored the fact that the tobacco industry was a major source of money for the California Republican Party—$165,727 in the 1995-1996 election cycle[16]—and that Wilson was the political leader of California Republicans. In any event, Wilson's defense hit a major snag when ANR obtained a March 4, 1990, internal memo between two Philip Morris lobbyists in Washington reassuring company executives that Wilson's act of returning some campaign contributions from the company did not mean that he was anti-tobacco. The Philip Morris lobbyists reported:

Wilson is only sending about 16K of the 100K he collected. This 16K only includes checks he received either from a tobacco company or anyone working for a tobacco company, i.e., Hamish Maxwell [CEO and chairman of the Philip Morris Executive Committee], Mrs. Ehud [wife of Ehud Houminer, CEO of Philip Morris USA], Bill Murray [former president of Philip Morris].

Apparently, he has also done this with other “controversial” industries such as lumber, chemicals, and others. The decision to do this was Wilson's alone, and in response to a wave of negative campaigning in California that not only attacks the candidates, but those who give to them as well.

You will be pleased to know that Pete called Hamish to explain that he was doing this to protect Hamish as well as himself. You will also be pleased to know that Pete is still “pro-tobacco.”[33] [emphasis added]

Wilson first saw the memo when he was being interviewed on camera by correspondent Peter Jennings for an ABC news special on tobacco. Wilson did not immediately say the memo was a lie, which limited what his staff could say later. (To the disappointment of many California tobacco control advocates, the exchange was not included in the final broadcast.) The memo, and the fact that the $84,000 retained by Wilson came from a variety of advertising agencies, law firms, and others who worked for the tobacco industry, received wide media coverage.[34-37]

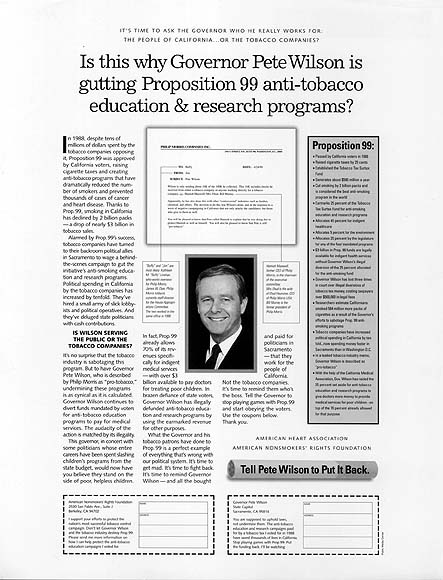

ANRF and AHA also featured the memo in their first full-page advertisement attacking Wilson for diverting Proposition 99 anti-tobacco money into medical services, which ran on April 16 in the New York Times, and later in the Sacramento Bee and Los Angeles Times (figure 18). The advertisement reprinted the original memo and asked the question “Is this why Governor Pete Wilson is gutting Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education and research programs?” The ad also posed this question: “It's time to ask the Governor who he really works for: The people of California or the tobacco companies.”

Figure 18. Newspaper advertisement attacking Governor Pete Wilson for his pro-tobacco policies. The American Heart Association and the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation ran this advertisement in California's major newspapers to educate the public and media about what had happened to Proposition 99 and to focus attention on Governor Pete Wilson's role in dismantling the Tobacco Control Program. (Courtesy of American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation)

The tension between the ANRF/AHA and the ACS/ALA's Coalition to Restore Prop 99 was growing because the Coalition kept pressuring ANRF and AHA to tone down the attacks on Wilson. On April 29, after the advertisement featuring the Philip Morris memo ran, Coalition co-chairs Beerline and Martin wrote to the presidents of ANR and AHA calling on them to work to restore Proposition 99 “in a more positive way utilizing its media campaign to inform and educate the public on the real issues regarding the restoration of Prop. 99 funds.”[38] ACS and ALA still hoped that the Legislature and the governor could be convinced to support the program with “a plethora of data and new information that will prove convincing and effective in restoring these important funds.”[38]

They distributed their letter to the governor, the Legislature, and the media. According to Martin, they felt that they had to write the letter to “everybody” to say that they had nothing to do with the advertisements:

Basically we said, “We share the same goal, there's no doubt about that, but your tactics and our tactics are not the same. We will pursue a positive campaign and we are notifying everybody that we have nothing whatsoever to do with those ads.” And we hand-delivered that to the governor's office and we made a lot of phone calls saying, “Look, we don't have any control over the ads, there's nothing we can do about them. This is being done by these two groups and these two groups alone, period. We're out of this.” And actually we finally did get that message across. I think that if we had not separated ourselves from those ads, we would have been dead politically at the Capitol.[39]

Carol found the letter highly offensive: “The tone was very patronizing, the whole `we're glad you share our goals.' Not `we're glad we have the same goals,' not `we recognize that your goals are the same as ours.' `We're glad you share our goals. You're welcome to share our goals.' We're welcome to join their coalition. We're welcome to sit at their table. Of course, we're not really welcome.”[3] The whole point of the ANRF/AHA campaign was to avoid sitting at tables.