The CMA House of Delegates Meeting

AHA and ANRF believed that the CMA's pro-tobacco position originated with its political leadership and did not enjoy particularly broad support among its physician members. To force the issue, they ran a full-page ad in the California edition of the New York Times on February 29, 1996, during the CMA's annual House of Delegates meeting. The advertisement was an “open letter” signed by former surgeon general C. Everett Koop and other physicians and scientists telling the CMA, “It is time to change” (figure 17). The advertisement helped stimulate a major floor fight over CMA's position on Proposition 99. Roger Kennedy, a physician from Santa Clara County who also served as chair of his local tobacco control coalition, was involved in the floor fight and later recalled, “It really became clear that we were not going to win based on the resolution, which was a very definite statement that the CMA should change its position…but I think that we got what we could. In retrospect, I'm sorry I didn't push harder. …I think that going down to flaming defeat in the face of the public may have accomplished more in the long run. …There's no question that the leadership of the CMA was not going to take a firm position that they would absolutely oppose any reallocation of funds.”[30] ALA was working through its own doctors who were CMA members to get a resolution supporting full funding. According to Najera, “We took this to the public to make it a public debate at the House of Delegates. We literally organized a public debate for what I would say was the first time on the floor of the board, of the House of Delegates for CMA.”[2]

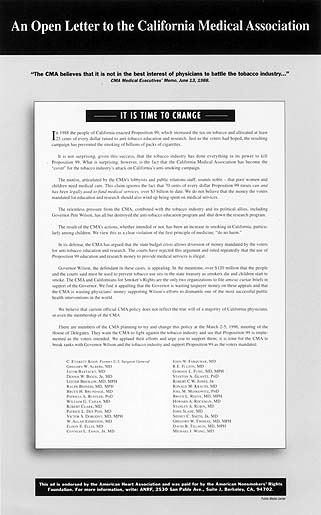

Figure 17. Newspaper advertisement designed to change the CMA's pro-tobacco position. The American Heart Association and the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation ran this advertisement in March 1996 during the CMA's annual House of Delegates meeting to stimulate discussion on the CMA's stance on tobacco issues. It helped precipitate a vigorous floor debate that marked the beginning of changes in CMA policy. (Courtesy of the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation)

The eventual CMA resolution was less than the public health advocates wanted. On March 3, 1996, the CMA House of Delegates voted to support full funding of Proposition 99's Health Education and Research programs if the governor and Legislature were willing to fund the “challenged programs” from the state General Fund.[31] If the governor and Legislature refused to use the General Fund, the CMA would continue to accept Proposition 99 funds for these programs, despite the court rulings. The CMA refused to withdraw its friend of the court briefs in support of the governor's position on AB 816 and SB 493. But in April 1996 the CMA did release a statement announcing its opposition to the governor's proposed budget concerning the use of the Health Education and Research Accounts to fund medical services.[32] Lewin saw the House of Delegates vote as representing a “fairly dramatic” change:

I think that the change was because I'm a new leader and I was able to go directly to the doctors in the CMA and ask them what they wanted, what they believed in. And it was very clear that they were quite willing to support education and research as well as indigent health care and that they hadn't been asked the question in that way, that they didn't think you should undermine education for indigent health care. But they didn't think you should cut indigent health care to enhance education. Their strategy was that all of these things were too important and that the state had enough resources to do all three of these things and do them well.[10]

The CMA joined the ACS/ALA's Coalition to Restore Proposition 99, a decision that had the effect of isolating the governor. According to CMA lobbyist Elizabeth McNeil, the CMA action not only isolated the governor but also “showed them [the administration] and all these other groups, we're going work for something else and that isolated them, which made it difficult for them. In some ways made it more difficult for us to bring them around because they were a little upset with us about that.”[27] The CMA's changed position made it less likely that the governor and tobacco industry could use medical necessity as the excuse for gutting the Proposition 99 Health Education and Research programs.