14. Doing It Differently

By the fall of 1995, because of the failure of the Legislature to appropriate the Proposition 99 revenues in accordance with the lawsuits, substantial amounts of Proposition 99 money had not been spent for anything. The courts stopped the governor and Legislature from spending the money for medical services, and the governor and the Legislature refused to spend the money for anti-tobacco education and research. The Health Education Account was projected to contain $191 million by June 1996, and the Research Account $82 million. A total of $274 million had been diverted away from anti-tobacco education and $71 million from research, and these cuts were having an effect. The prevalence of youth smoking had increased by 20 percent between 1994 and 1995 (from 9.1 percent to 10.9 percent), and adult prevalence was no longer declining.[1] In fact, adult prevalence appeared to be increasing for the first time since the state began collecting statistics in 1974. Thanks to the governor, the Legislature, and the medical lobby, the tobacco industry was reversing the damage that Proposition 99 had done to it.

As they prepared for the 1996 reauthorization fight, tobacco control advocates had two court decisions on their side. But a favorable court decision had been of little help to them in 1995 when the Legislature passed SB 493. The governor and Legislature seemed more angered than chastised by their legal defeats. The challenge to tobacco control advocates was how to change the outcome of the authorization fight.

The Need for a Change

The lobbyists from the three voluntary health agencies—American Cancer Society (ACS), American Lung Association (ALA), and American Heart Association (AHA)—organized a series of fall meetings led by AHA to plan a strategy for the Proposition 99 reauthorization fight. They needed focus, energy, and resources. As Paul Knepprath, who had joined Tony Najera as a lobbyist for the state ALA in 1995, explained, “What we needed the next go around was not a pure sort of traditional legislative lobbying campaign but rather a campaign that included other elements that brought the public pressure from the outside more. …There was a consensus that we needed to do things differently for reauthorization than what we had done in the past. There was consensus on bringing in new players and new partners, which I'm not sure which ever came to fruition.”[2] Beyond acknowledging that something had to be done differently, there was little activity.

This lack of action on the part of the voluntaries was confirmed for the local lead agencies (LLAs) in a monthly technical assistance telephone call hosted by the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation (ANRF), the educational arm of Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR). The service was part of the technical assistance provided by ANRF under contract to the Tobacco Control Section (TCS). ANRF director Julia Carol used this forum to let the LLAs know what was happening on reauthorization. Carol attempted to use an early fall teleconference to bring the LLAs together with the ACS:

ANR's plan was to have nothing whatsoever more to do with any statewide efforts, we were just doing our work. But I still wanted to look out for the constituency we serve, so I invited the Cancer Society to come on the line and give an update on the plans for reauthorization for Prop. 99. …I was trying to get these people to look to the Cancer Society for leadership and not to us and that these people were very mistrustful and that they needed to know that something was going on and they needed to be included. They needed to be a part; they're tired of being left out. They're suspicious of deals being cut in the dark and of people not telling them things.

So really there needed to be a frank conversation with them about what the plans were and what they could or couldn't do, what the communities could or couldn't do. So…I asked Theresa [Renken, the ACS lobbyist] to give an update and she said, “Well you know, we're going to be forming a coalition and we're going to be talking about blah and we're going to have a big meeting in the fall and we're going to do this and that and by November we'll do the other and the Legislature is gone and they'll come back and blah and blah and blah.”

― 286 ―And I said to her, “What's our plan in the meantime, right now?” And I meant for influencing the budget language before the budget comes out, but I didn't say that. “What's our plan now?” And she said in a very snotty tone, this is a teleconference with over one hundred people on it, “Well, Julia, if you understood the legislative process you would know that the Legislature is about to be out of session. So there is nothing that can be done until they return anyway.”…

So I said to her, “Theresa, it sounds to me like the campaign is going to be run much the same way as it has been the past, is that correct?” And she said, she paused and said, “Well, yes.” And I said, “I see. …well then, if you are going to do things the same way, what makes you think you are not going to get the same results?”[3] [emphasis added]

The Sacramento lobbyists who had negotiated the implementing legislation for Proposition 99 over the years still did not appreciate the need to actively engage the grassroots or the power of doing so.

Tony Najera, who, with John Miller, had headed the “inside” game on behalf of the health organizations since 1989 and the passage of AB 75, revealed why the inside game was played the way it was: “Paul [Knepprath] would from time to time criticize me and rightfully so because he wanted me to include other parties. And I would always say, `That's nice to be inclusive and to bring people along. However, there are times where you have personal relationships and…they don't want other people. They want to be able to confide, quietly tell you what they think.'”[2] Najera was sensitive to his role in the inside game: “I've been accused of giving away the store by people that don't understand this game. I consider that a false accusation which is very unfounded.”[2]

Steve Scott of the California Journal observed that the behavior of the voluntary health agencies' lobbyists was typical of the tendency of the lobbyists in Sacramento to live in their own world:

As somebody who covers the Capitol, I can't be too critical of the way they [the voluntary health agency lobbyists] approach the Legislature. …You tend to become a product of the system in which you operate and over time I'm sure that these lobbyists are no different from any other lobbyists. Over time you become inculcated into the culture and you start to think in incremental terms rather than in bolder terms. But that's why you have grassroots. …Ultimately the lobbyists are employees. And if the people who employ them don't look beyond what they are telling them, then they are not doing their members any good service either. So I don't think that the grassroots arms of the organizations can be exempted from a share of responsibility for allowing the Prop. 99 situation to atrophy the way it did. Because the repository for all wisdom isn't the lobbyist in Sacramento.[4]

Thanks to Proposition 99, the TCS and ANR leadership, and the LLA directors, the local tobacco control coalitions were getting stronger and more organized. They could not understand why the lobbyists in Sacramento were not reaching out to tap this power.

At the same time, things were changing at the AHA in a way that would lead to a much stronger appreciation of the grassroots. Mary Adams had recently replaced Dian Kiser as AHA's lobbyist. While Adams had been involved in the early Proposition 99 fights as the ACS lobbyist (as Mary Dunn), she had lived in Europe for several years and had only returned to Sacramento in November 1994. She was surprised at how far the Proposition 99 allocations had deviated from the terms of the initiative. In crafting a legislative strategy for 1996, Adams felt that the voluntary health agencies needed to open up the process and involve new people, particularly those in the field who had been fostered by Proposition 99's community-based activity.[5] She also recognized the need for the tobacco control advocates to be more nonpartisan and bipartisan:

I wanted to have both Democratic and Republican representatives. Because in the past, we'd just always focused on the Democrats and I felt like that wasn't going to get us where we needed to go. …I started communicating to my organization after meeting with this group and I hawked the same three points all the way through with this group that I had drawn together and then with my own organization: that we needed to have an intensive grassroots effort,…that we had to have intensive use of the media to get the public to focus on the issue, and that we needed to have a contract lobbyist with Republican ties who would be able to work the issue for us in a successful way. And then I shored that up with just my strong feeling that this was all going to take place through the budget, that it was not going to go through the normal legislative track.[5]

Having been absent from the battles in Sacramento over the past few years, Adams had an easier time recognizing strategic errors that the voluntary health agencies had made: “The strategies that had been used in the past…had been dismal failures. When I left, there was a ton of money coming. When I came back I saw the whole thing in a real mess. I knew that we had to draw together many more facets, many more approaches than had been used in the past.”[5] Adams wanted a more aggressive campaign to defend Proposition 99 that reached well beyond the Capitol building and was determined to get ANR and its past president, Stanton Glantz, on board.

But involving Glantz and ANR was not just a matter of adding their names to a coalition letterhead and proceeding with business as usual.

ANR had built its reputation as a grassroots organization by being a confrontational outsider. Even if it could be persuaded to change its focus from local ordinance fights, its preferred strategy, to a state-level one, it would certainly not compromise its style in the process. ANR had its own vision of what was needed in the Proposition 99 fight. According to ANR co-director Robin Hobart,

One thing that we realized was that the only way you were going to see real reauthorization of Prop. 99 at the full level—and this was based on our experience with [Proposition] 188 in some ways—was that you're going to have to run it like an election campaign, not like just any old bill. It had to really be a campaign with all the attendant grassroots strategy and media strategy and inside-the-Capitol strategy. …The other thing that we knew based on how the governor had responded and the Legislature responded to our lawsuits—we were successful in court but having absolutely no effect whatsoever with regards to what the Legislature was prepared to do—was that it was going to have to be a real gloves-off campaign. People were going to have to name names. And the California Medical Association was going to have to be forced to get out of the way.[6]

ANR could envision an effective strategy, but it had no intention of actually getting involved. Hobart continued, “We didn't believe that it ever was going to happen and so to a certain extent, we decided, `It's really awful, it's really a shame, but ANR has absolutely no ability to do anything about any of this by ourselves and we're done.' We gave at the office, the lawsuit was the last thing that we made a commitment to do to try to save Prop. 99 and after that, we were done.”[6]

Glantz also saw the need for a more confrontational strategy but was more willing to get involved. In a 1996 interview he said,

And what happened last year [in 1995] was I saw the whole program just going down the drain. I think the CMA and the Tobacco Institute were coming

― 289 ―in for the kill. …The program was in a complete shambles, because local lead programs had basically been dismantled, because the media campaign was a mess. And the tobacco companies and the Medical Association had succeeded in turning this into a fight about money, and a fight about money is not news in Sacramento. And Tony [Najera] and John [Miller] and the others up there were still pursuing the same old insider strategies where they'd been screwed every time. Just all the tea leaves were looking bad. …I sat back and I said, “Now,…am I going to sit here and chronicle the demise of this program while watching it and have a nice clean paper where I've written about how the thing went down the drain?”…I just decided I could not stand to sit and watch this thing go down the drain because I thought it was just too important.[7]

Meanwhile, as AHA was trying to recruit ANR and Glantz, ACS was engaged in its own discussion about reauthorization. According to Don Beerline, a past chair of the ACS California Division, ACS also recognized the need to do something different:

What the ACS decided early last fall [of 1995] was that we had been unsuccessful. The advocacy in those previous reauthorization campaigns had primarily been carried out by our professional lobbyists. The lobbyists in those previous campaigns have complained somewhat that they didn't feel like they really had the support to do what they needed to do. And given the past history of that failure, the ACS said, “We need to do something different this time.” The debate went on within the ACS, and it culminated when our board of directors in November of 1995 committed $120,000 for this campaign plus obligated one individual full time for the first six months of 1996, and this is not a clerical person. This was a middle manager. So that's a significant commitment of personnel and funds compared to the last time, the assumption being with that sort of commitment then we would become, for the first time, the lead agency in this fight. And in the past, it has been other organizations have been considered the lead agency. And that is exactly what happened. …Lung Association definitely and their representatives were definitely not happy when ACS took the role of the lead agency in this and decided that we needed to have a different strategy.[8]

Although everyone had the same goal—full funding of the Health Education and Research Accounts—there were no indications that their plans to achieve those goals meshed.

The December Meeting

Adams scheduled a December 13, 1995, meeting at AHA in Sacramento in the hope that it would get the key players together to discuss reauthorization,

AHA had its chance to do so when Glantz obtained a copy of a thirty-second anti-smoking advertisement, “Insurance,” produced by DHS. After making the point that tobacco companies owned insurance companies that gave nonsmoker discounts, the advertisement ended with the question “What do the tobacco guys know that they are not telling us?” The administration was sitting on the advertisement. Glantz suggested that AHA hold a press conference to demand that the governor put the advertisement on the air. AHA did so, together with ALA and, at the last minute, ACS. The event got media coverage, and Glantz and ANR agreed to attend the December meeting.

Adams's meeting brought together lobbyists from the three voluntary agencies—Adams from AHA, Knepprath and Najera from ALA, and Renken from ACS—as well as John Miller from Senator Diane Watson's office, Carolyn Martin, a volunteer with ALA and past chair of the Tobacco Education Oversight Committee (TEOC), Carol and Hobart from ANR, and Glantz. The morning session featured a briefing by the TCS staff on the substance of the program; TCS left before the afternoon strategy session.

During the afternoon session, Adams announced that AHA had committed $50,000 for the reauthorization effort, $25,000 of which would go to ANR for a grassroots campaign and the rest to do other things, such as hiring a Republican lobbyist. ANR committed $25,000 of its own, ALA committed $10,000, and Glantz wrote a personal check for $1,000—creating a war chest of $86,000. Renken did not mention the fact that ACS had already committed $120,000 to the Proposition 99 effort. The meeting ended with the health groups posturing, not with an action plan. Glantz, Carol, and Hobart, who felt that the pledged money would be enough to mount a substantial campaign, left the meeting demoralized.

The meeting was a watershed. Rather than resulting in a larger, more diverse working group, which had been AHA's goal, the meeting eventually resulted in a divided coalition and two different reauthorization campaigns.

Najera later described his reaction to the meeting:

We had been planning and planning since October and we had one thing in mind, that was a statewide coalition—united we stand together. But we go to this meeting in December and that was the telling…thing for me, that Mary was playing both sides, because ANR and Stan had not been working with us necessarily at the October meetings. And consequently when we got to the meeting in December, it was very clear that the Heart Association was not necessarily interested or concerned about working together with the Coalition. And they frankly were attempting to tell us that this wasn't going to work. It was for me the telling time when it became clear that they didn't want Cancer and they were afraid that by contributing the money Cancer would take the leadership in this thing. And it wasn't going to work because Cancer and the governor were friends.[2]

According to Knepprath, ANR and Glantz were assuming that any ACS strategy would represent “the old school, the old way of doing things, Sacramento based, lobbying, an inside play of the game.” Knepprath went on to say, “Stan and ANR were advocating `we're not doing that this time. We're doing something different this time,' which is their right and prerogative. …They were definitely thinking fast track, and Stan by this time had been pitching to all of us, `Let's utilize the [Proposition] 188 format in which it wasn't centralized; you didn't really have a centralized coalition. Everybody did their own thing and we worked together and, gee, wasn't that great? So let's do that again.'”[2] Knepprath was seeking basically the same type of centralized coalition that had operated in the past, except with ACS in charge.

Adams remembered a lot of tension in the room at the December meeting: “Theresa went out in the hall and was talking to somebody, she had her little nose out of joint and certainly didn't say that they had any money. …But I think that they had already gotten some money put together as well. But it was clear that Tony was already starting to feel somewhat threatened. The fact that I had been the one that convened this meeting with TCS and with the others, that Stan and Julia were there …”[5] For Adams, the philosophical differences could have been accommodated if only the strong personalities had not gotten in the way. This view underestimated the depth of the philosophical disagreements that existed over the approach the campaign should take. Adams was unaware of how much money ACS had committed to the campaign, and the distrust she, ANR, and Glantz felt about ACS in a leadership role was aggravated by Renken's failure to mention it when all the other organizations were anteing up their contributions.

If the other organizations had negative reactions to the ANR presence, it was echoed by ANR's response. ANR had not wanted to be involved in the Proposition 99 reauthorization campaign and had not wanted to go to the AHA meeting. Adams convinced them to come. Carol said about the meeting,

We didn't want to be involved in a big campaign to save Prop 99. However, one of ANR's goals is to separate tobacco money from politicians and to highlight the nefarious connection between the tobacco industry and politicians and their interference in public policy. To that end, the thought of beating up Pete Wilson a little every now and then over his connection to Philip Morris in fact appealed to me greatly. When Pete Wilson appointed Craig Fuller, the former senior vice president of Philip Morris, as his campaign manager [for Wilson's abortive presidential campaign in 1995], we had run a radio spot asking if Pete Wilson was running for president or just wanted to be the next Marlboro Man. …And I thought we'd follow it up with a Hall of Shame ad, which I had in draft form at that meeting and we wanted to run. …People were starting to put money on the table as far as what they were going to do with Prop 99, and Stan thought it would be great for us to spur them along by saying what we were doing. Stan and Mary both begged us to be there. …Mary decided, and she probably regrets it now, but Mary decided that in order to win Prop 99 we had to be a major player. …

… it was awful. The Cancer Society said nothing, Lung said what they were going to put up, we said what we were going to put up, Heart said what they had to put up. Cancer stayed silent. Theresa only said one or two things, one of which was, “Well, if you beat up the governor, how do you expect him to sign your bill? Why would he sign the bill if you beat him up?”…She said nothing about any money.

The next thing I know, Cynthia [Hallett of the Los Angeles LLA] calls me from L.A. and tells me that the Cancer Society has announced the week before in a public forum…they had I think it was $110,000 and they were going to run a Save 99 campaign. Now why the Cancer Society would feel free to discuss this publicly,…but would sit there in a meeting with her so-called partners—an inside-the-room confidential meeting—and not say a word about it is beyond me.[3]

ANR did not believe that the coalition was prepared to adopt a vigorous grassroots strategy, attack the CMA, or take ANR's advice seriously. Hobart “came away from that meeting really firmly convinced…this is not going to work.”[6]

At the December meeting Glantz knew about the money that AHA, ALA, and ANR had available, but he did not know about the ACS plan. He later recalled,

We went into that meeting with $86,000, which I thought, intelligently spent, was enough money, and I went up there all excited. And what happened was exactly the opposite of what I was expecting, and I think the basic problem was that if normal human beings had been at that meeting, as opposed to voluntary health agency lobbyists and small-minded people, we would have walked out of that meeting excited and with a new leader in Mary. Because she's the one who pulled it together. She had established a working relationship with TCS. She had gotten all the key stakeholders in the room and come up with a significant amount of money.

I would have thought we would have walked out of that meeting with a new fresh face, with a smart woman with some serious resources: I was there with the sort of intellectual stuff, Julia was there with the grassroots stuff, Tony was there with all of his insider stuff, which he's good at, Mary was there. We had Paul Knepprath, who is good with the media. And I think we had the real makings of a good solid campaign. …

I think they were tremendously threatened by her [Mary Adams] and the Heart Association. …This had been their little sandbox for all these years and all of a sudden, here was a new player. And rather than saying, “Oh boy! We've got somebody else to work with, we can be strong and productive and this and that,” they were instantly threatened. …And I think the fact that Theresa did not disclose that the Cancer Society had this big wad of money at the meeting was just at the very least, unprofessional, and duplicitous and devious and dishonest and all these other things. And so we came out of that meeting…very depressed and Julia had had it. And I was very discouraged.[7]

The only person who did not seem discouraged by the meeting was John Miller. Miller felt that the meeting revealed the divisions between the insiders and outsiders but that, in the end, having an aggressive outside campaign might be helpful.[9]

Whereas Najera and Knepprath suspected that ANR and Glantz were threatened by ACS, Glantz was concerned that ALA and ACS were threatened by AHA. Either way, the questions about leadership and direction, far from being settled by the meeting, seemed to be exacerbated. Despite their differences in strategies, however, all the players believed that three things had to happen in 1996 if they were to secure full funding of the Health Education and Research Accounts. First, the CMA had to drop its advocacy of the diversions. Second, the sole reliance on the inside game had to end and the grassroots constituency had to be involved. And, third, the media attention had to be recaptured with a focus on “following the will of the voters” instead of a budget battle.

The CMA

California's fiscal problems and the CMA's support of diversions had been the governor's best defenses for diverting the Proposition 99 monies. Scott emphasized the importance of the CMA to the success of previous diversion efforts, saying,

I don't necessarily believe that you're going to find secret communiques between the tobacco industry and Steve Thompson [the CMA's chief lobbyist] or anybody with the California Medical Association. I don't think that there is direct contact and I don't think there was intentional collaboration. But what you had was a sort of a symbiosis which was acquiesced to by the Medical Association because it furthered their goals. As this relates to Prop 99, you had the Medical Association that wanted more money for direct medical services, specifically CHDP. You had the tobacco industry that was only too happy to let that happen. The Medical Association in the minds of the legislators who want to support the tobacco industry becomes their astroturf, their front. They say, “Well, I'm just following the views of the California Medical Association, which has always been very strong on tobacco issues, co-sponsors of Proposition 99, co-sponsors of AB 13.” Whatever else you want to say about them as a special interest, you can't impugn their reputation on tobacco. You could, but for a legislator who is inclined to vote tobacco's way, that gives them convenient cover.[4]

In fact, there was a much more active and direct engagement between the CMA and the tobacco industry than Scott believed (see chapters 3-5).

An important leadership change in the CMA helped to shift the CMA away from its aggressive opposition to the anti-tobacco education and research programs. In 1995 Dr. Jack Lewin was appointed as the new executive vice president, replacing Robert Elsner. Lewin had headed the public health department in Hawaii prior to his CMA appointment and was personally sympathetic to tobacco control. When asked about finding Proposition 99 on his agenda almost immediately, Lewin said,

As I arrived on the scene, I was confronted with allegations from Dr. Glantz and others, who told me that CMA had been far from a proponent of anti-tobacco efforts and really had thwarted those efforts by virtue of its collusion with the tobacco industry and many other nefarious scenarios. I knew from my discussions with the leadership, the doctors of the association, that nothing could be further from the truth. And while I was greatly concerned, I knew that there had to be some complex relationship in the competition for funds or in government relations or in strategies and tactics, where you have competing agencies in a very awkward state of working against each other instead of with each other.[10]

At the time, of course, Lewin was not aware of the secret tobacco industry memos documenting its relationship with the CMA. (These memos were not made public until 1998 as part of the State of Minnesota's lawsuit against the tobacco industry.) Lewin recognized that the CMA's history on tobacco control was a problem. He went on to say,

In the back of the history of CMA, there was clearly a part of the time when Prop 99 came out, where the person who was in charge of our government relations at that time was a wheeler-dealer type of very effective political strategist in Sacramento who was willing to work with whomever he needed to work with to get things done. Sometimes he would make a trade-off that would frankly not please me or the current leadership of CMA. But that was just the way things were then.[10]

Like AHA, ANR, and ACS, Lewin believed that people outside the Sacramento lobbyists' circle needed to get involved in the decision making about Proposition 99:

If you talk to the constituencies in those [voluntary health] agencies, they're victims in my view because the doctors will be happy to get together with the Cancer, Heart and Lung boards and those constituencies and work on this. You're stuck at the political level of the agency staff and the government relations people that themselves have developed long-standing animosities they're not going to let go. …So what we decided to do was try to get out of that loop. That meant telling our government relations people to change the way they were relating to these other groups. If they couldn't do it, then we had to get some other people to make the relationships because the relationships were dysfunctional. …We're going to have to get through this whole epic of the past—“you did that to me, you did that to me, why did you do that to me?” Get beyond that and say, “Can we get together this year to go get this money?”[10]

But Lewin could not act unilaterally. There was a strong animosity within the CMA toward the anti-tobacco education and research programs that had built up over the years, dating back to at least the Napkin Deal of 1987. Steve Thompson, Willie Brown's longtime aide, was an especially popular figure within the CMA.

The Governor's Budget

The health groups hoped to avoid another battle in the Legislature. They had won two court rulings on the illegality of diverting Proposition 99 Health Education and Research money into medical services. More important, the state's economy had improved, which meant that the excuse for the diversions—fiscal necessity—had evaporated. Indeed, when Governor Wilson released his budget on January 10, 1996, he announced that “solid gains in employment and income will continue for the next two years.”[11]

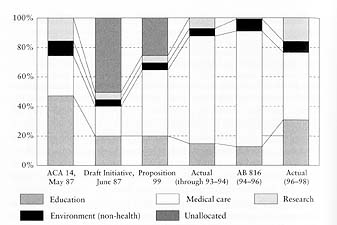

Rather than proposing expenditures conforming with the two court orders, however, the governor's 1996-1997 budget was identical to AB 816 and SB 493. (Wilson cited SB 493 as his rationale, purposely ignoring SB 493's stipulation that, effective July 1, 1996, the allocations of tobacco tax revenues to the Health Education and Research Accounts would conform to those established in Proposition 99: 20 percent and 5 percent, respectively.) Wilson proposed spending only $53 million (of the available $191 million) on anti-tobacco education and $4 million (of the available $82 million) on research. He proposed diverting $57 million into medical services.[12] Wilson was still trying to starve the anti-tobacco programs to death.

The three voluntary health agencies issued a press release immediately after the governor released the budget, saying they were “outraged” at the budget proposal and that “it reveals his latest attempt to thwart the law and steal monies earmarked for anti-tobacco education and research programs by the voter-approved Proposition 99.”[13] The press release announced that “the health agencies refuse to let that happen and are launching a statewide campaign to invoke public awareness and put pressure on legislators to reject the Governor's tobacco fund raid.”

Changes in the Legislature

Not only would the health groups' change in approach have its effects, but the fate of the governor's budget in the Legislature would be different this year because the Legislature had changed too. The Republicans had taken control of the Assembly in the 1994 elections by one vote, thanks in part to a massive $125,000 contribution that Philip Morris made to Republican Steve Kuykendall (R-Long Beach) the weekend before the election, which helped him defeat incumbent Democrat Betty Carnette.[12] By that time, the tobacco industry had shifted from giving campaign contributions in a bipartisan manner to favoring the Republicans. During the 1993-1994 election cycle, 45 percent of the contributions went to the Republicans; by 1995-1996 the share had shifted to 56 percent.

On April 24, 1996, Senators Watson, Hayden, and Petris, three of the strongest advocates for tobacco control in the Senate, wrote a long memorandum to Senator Bill Lockyer, the Senate's president pro tem and a senior Democrat in the Legislature. The subject of the memo was the Democratic “Caucus Position on Tobacco Issues,” and the senators argued that it was not only good policy, but good politics for the Democrats to embrace tobacco control:

Tobacco regulation, a long-standing and contentious political issue, has assumed even greater prominence in recent months, and gives every indication of continuing to hold the media and the public's interest. We would like to encourage the Democratic Caucus to assume a much more aggressive attitude against tobacco. There are sound policy reasons for such a reassessment of our position, but there are also equally sound political reasons for such a change.

… Control of tobacco is morally the best policy. It is also a popular issue consistent with Democratic principals [sic], and an issue with every possibility of becoming an electoral wedge. We believe the benefits to Democrats in terms of the public good will substantially outweigh the anticipated loss of tobacco support.[14] [emphasis added]

In John Miller's view, the shift in tobacco industry campaign contributions to the Republicans was the key factor that got the Democrats lining up to support the Proposition 99 programs. He commented, “What moved them as a body wasn't our rhetoric or the public's interest or the public's wishes clearly expressed and apparent to everyone. It was the stupid move by the industry in terms of donations.”[9]

The new Republican leadership in the Assembly was clear about its pro-tobacco sympathies. Curtis Pringle (R-Garden Grove), who became the speaker of the Assembly on January 5, 1996, accepted $17,250 in tobacco industry campaign contributions in the election cycle from 1995 through the March 1996 primaries; this amount ballooned to a total of $105,750 after he became speaker.[15][16] Pringle believed that “some of the legislative changes [to limit tobacco] swung the pendulum too far in one direction.”[17] The chair of the Assembly Health Committee passed to Brett Granlund (R-Yucaipa). In the 1995-1996 period, he accepted $31,750 in tobacco industry campaign contributions and described himself as “a free-enterprise, no-tax smoker. It doesn't matter if I'm chairing the Health Committee. Those [anti-smoking] people don't have a right to tell everybody else how to live.”[16] A Los Angeles Times editorial saw the Republicans as a “Whole New Pack of Buddies for the Cigarette Industry.”[18]

The Democrats also had an important leadership change. Willie Brown, the longtime speaker of the Assembly when it was controlled by the Democrats, left the Assembly in January 1996 to become mayor of San Francisco. By then, Brown had accepted $635,472 in campaign contributions, more than any other legislator in the country, including members of Congress from tobacco-growing states.[16] Brown had been a powerful presence and used his power as speaker to protect the tobacco industry's interests.

Assembly Member Richard Katz (D-Panorama City) replaced Brown as the Democratic minority leader. In stark contrast to Brown, Katz was a longtime supporter of tobacco control and had only taken $5,500 in tobacco industry campaign contributions, none of them since 1991.[15][19] Katz specifically rejected the claims that the Proposition 99 diversions were made because of fiscal necessity: “In terms of the overall budget, it's not a lot of money. …I don't know who came up with it; it was a very very clever strategy that helps big tobacco under the guise of providing indigent health care. …The budget was a convenient issue for them.”[20] As Adams observed, “The real hero this year was Richard Katz. Without a doubt. …Since he's the Democratic floor leader, he's got a lot of loyalty from the other Democratic members on both sides of the house, so that was really good. …it was like they'd all had this conversion, some sort of `Come to Jesus meeting' must have taken place in the California State Capitol because they were all saying how wonderful they thought Prop 99 was.”[5] Katz's ascendancy to the leadership greatly reduced the likelihood that the Assembly could muster a four-fifths vote to divert Proposition 99 money, regardless of what the Republicans wanted to do. This fact fundamentally changed the political dynamics surrounding Proposition 99 in the Legislature.

Meanwhile, the Democrats still controlled the Senate, and a shift in attitude toward Proposition 99 diversions appeared to be occurring there, too. Senator Mike Thompson (D-Santa Rosa) chaired the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee, which meant that his position on Proposition 99 was also important. According to Diane Van Maren from Thompson's office, “Mike made it very clear he was not going to vote for a redirection to that level and that we thought that we needed to talk about transitioning some of these programs and using some General Fund monies, in a prudent manner. …Mike was very well aware of the increase in adolescent smoking and thought that if we had the opportunity, we should start using the Health Education monies again and more fully to mitigate that.”[21]

Another change was the decision of Assembly Member Phil Isenberg (D-Sacramento) not to be involved in Proposition 99 reauthorization. Isenberg said, “I'm bored with it, I don't want to do it anymore. I've done it three cycles. I've done enough. I've got other things to do.”[22] Isenberg's absence meant that the dynamic of the previous authorization efforts would be disrupted, which was potentially advantageous for the tobacco control advocates.

A final major change in the Legislature, according to Richard Katz, was the effect of term limits. Katz felt that they helped the Proposition 99 Health Education and Research Accounts:

One of the things with term limits is you have a whole bunch of members here who did not vote for that compromise, didn't go through that budget fight. So they said, “How could you do that? Don't you understand, you can't do that now the courts have ruled?” So you lose the historical context that that all took place in and without saying that's good or bad, they bring a different set of criteria to the evaluation. I also think that the folks who are elected now are much more anti-smoking than the group that was here ten years ago.[20]

In January lobbyists from the three voluntary health organizations—Najera, Knepprath, Adams, and Renken—met with Katz to sound out his views on the Health Education and Research Accounts. They proposed several authors for the Proposition 99 reauthorization bill, but Katz decided to carry the bill to restore Proposition 99 himself. He also agreed to let individual members vote their conscience on the bills rather than make this a leadership issue, as it had been in AB 816 and SB 493. When asked why he decided to carry the bill, he said, “I like fights. I like fighting with people that are arrogant.”[20] He went on to explain,

Someone needed to step out of the chaos and do it. When we sat around and talked about who was in a position to do it, it made the most sense for me to do it just because of what I'd done on the issue before. …We also saw this as a potential issue that could be an “us versus them.” We knew the public was on the side of the Prop 99s of the world and that Republicans for the most part were much more beholden to tobacco companies than Democrats, even though Democrats have had their fair share over the years. I knew that Philip Morris was looking to underwrite a huge piece of the Republican convention in San Diego. …So there were good political reasons for doing it also.[20]

Knepprath understood Katz's political motives: “We were going to concede to him as the author of the bill his ability to do what he wanted, but I think it was at that meeting that we really launched then the effort to do our grassroots stuff and to really build the campaign around his bill.”[2]

The Coalitions Form

Following the December 1995 meeting, ANR, AHA, and Glantz decided to move ahead without ALA and ACS, in the hopes that, once things started happening, the two other organizations would join them. Adams invited Roman Bowser, AHA's executive vice president, to a meeting to work out how ANR would run a grassroots campaign coordinated with AHA's lobbying effort. AHA was to help finance this campaign by providing $25,000 to ANR. Under Bowser's leadership, the AHA had been evolving from an organization that did not even have a lobbyist before 1988 to one that was willing to engage in a political fight. When asked about this change, Bowser replied,

I think that if we look back over time—the origin of Prop 99, the passage, the lawsuits—I think you see somewhat of an escalation of our activity and involvement each step of the way. The more I learned about it, the more interested I was in it. …When the lawsuits started, then we started getting a little bit concerned. I think that the real turning point for me was [when] Stan Glantz called our national executive vice-president and left him a voice mail message saying that “we've really got some problems out here with Prop 99” and…he passed the message to me. …I knew who he [Glantz] was. I wasn't real thrilled about meeting him because I'd read some unflattering remarks he made about the Heart Association. Anyway, I called him back. I asked him if there was anything I could do to help him, what he wanted, and that was the turning point, that telephone conversation, because he spent quite a bit of time with me basically educating me on what was really going on behind the scenes with Prop 99. Also, I did not realize until then that we were in serious danger of losing the whole thing. …[but] I was still bound and determined to have the American Heart Association stay with the American Cancer Society and the American Lung Association.[23]

When the meeting started, Bowser announced that the ACS had just told him that it would put $120,000 into an effort to save Proposition 99 on the condition that ACS run the campaign. ANR and Glantz reacted skeptically, as did Adams. They were concerned that ACS, as the least combative of the voluntary health agencies, would simply adopt earlier failed strategies, and Glantz urged Bowser to move ahead with the original plan to work with ANR. Bowser, although doubtful about ACS, felt that he simply could not ignore his colleagues at ACS and ALA. The meeting ended without agreement on how to proceed.

The next several weeks were devoted to extended discussions among ANR, AHA, and Glantz on how to deal with ACS. By mid-January, Glantz felt that saving Proposition 99 was impossible.[7] ACS and ALA were unwilling to confront the CMA and the governor, and AHA was unwilling to move without them. The governor had released an unacceptable budget, but the health groups did nothing more than issue a press release. On Friday afternoon, Glantz told Carol that he was recognizing reality and giving up. Carol replied that the only reason ANR was involved was because of pressure from Glantz and that without Glantz, ANR would drop out, too. (She had joked that she knew Glantz would write the history of Proposition 99 and she did not want ANR blamed for letting it die.) Glantz called Adams and Bowser as a courtesy. Adams asked Glantz to keep an open mind over the long Martin Luther King Holiday weekend.

The following Tuesday, Adams called Glantz and Carol and said that AHA had decided to break with ACS and ALA and asked them to reconsider working with AHA. AHA intended to confront the CMA and the governor and mount a major campaign to reengage the public in the future of Proposition 99. Carol was particularly surprised. Following the December meeting, ANR had decided not to get involved in the Proposition 99 reauthorization fight. Rather than simply saying no to AHA at that time, Carol had laid down a set of four conditions that AHA would have to accept about the campaign that she was sure would scare them off:

One, that it'll really be hard hitting. And that means taking on Pete Wilson and the CMA. Two, that I can find a grassroots coordinator who I really trust, because otherwise I can't do this. Three, they were going to have to pay us. And, four, we're not going to be in a coalition with Cancer and Lung, given their position on not wanting to bash the governor and the CMA. …It was clear that they had different strategies in mind. So they chose us and you could have blown me away. I thought I was off the hook. …So there we were. Stuck running a campaign![3]

When asked about the change at AHA, Mary Adams said,

We were not going to sit back on our heels and watch yet another year go by and dismal failure. Cancer and Lung put together this group called…“Keep the Promise to Our Kids, the Coalition to Restore 99.” They were going along on a similar path but in a much less rapid way and a much less contentious way. …They were simply…not going to play an “in your face” game. …And my thought had been from the get-go that we had played nice in the past and it didn't work; that we had to take the gloves off and play the game differently, period.[5]

AHA committed $50,000 for a grassroots lobbying campaign and hired a Republican lobbyist. Up until that point, the health voluntaries were closely allied with the Democratic Party; now the Republicans controlled the Assembly. AHA, ANR, and Glantz began a paid advertising campaign to publicize the failure of the governor and the Legislature to follow the will of the voters. They also started to work to force the CMA to stop supporting the tobacco industry.

Meanwhile ACS, joined by ALA, had been pursuing their nonconfrontational reauthorization strategy. Beerline explained, “We're going to be nonpartisan, positive, try to take the high road and create win-win situations. …Heart decided that the campaign that we were putting together was not aggressive enough and that they wanted to have a more aggressive campaign but still remain a member of the coalition. And, of course, they were talking by then with ANR. And we basically told Heart that they couldn't have it both ways. …And ANR, of course, has their own style, the way they do things.”[8] Beerline went to on to say that if AHA went off to work with ANR in ANR's style, then AHA could not be part of the old coalition.

While not willing to be confrontational, ACS was planning to change its tactics from the past. The organization planned to devote staff to coordinating a grassroots campaign and to hire a professional public relations firm to help attract media attention to Proposition 99 and arrange meetings with editorial boards.

The “Hall of Shame” Advertisement

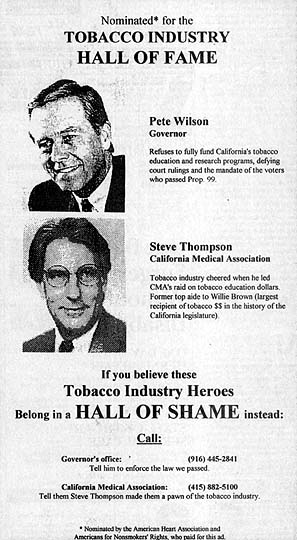

The core of the ANR/AHA strategy was to bring the issue of Proposition 99 back before the public, with the expectation that an informed and engaged electorate would force the politicians to implement Proposition 99 the way the voters intended. The media had come to view Proposition 99 as just one more fight over money in Sacramento. So the first step in accomplishing this goal was getting the media interested in the issue by publishing a very strong advertisement in the Sacramento Bee attacking Governor Wilson and CMA lobbyist Steve Thompson for their roles in the Proposition 99 diversions. This advertisement, which appeared on January 30, 1996, featured photographs of Governor Wilson and Steve Thompson as the mock nominees for the “Tobacco Industry Hall of Shame” (figure 16).

Figure 16. “Hall of Shame” newspaper advertisement. Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights and the American Heart Association ran the advertisement in the Sacramento Bee on January 30, 1996, to indicate that the rules of the game on Proposition 99 had changed. (Courtesy of Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights)

The advertisement attracted Thompson's attention. Nancy Miller of the law firm Hyde, Miller & Owen wrote Bowser, objecting that “your political advertisement is personally and professionally damaging to Mr. Thompson. He would like a retraction of the damaging and inaccurate statements in an ad of equal size placed in the Sacramento Bee as soon as possible. He is requesting approval of the language of such an ad.”[24] Steve Thompson followed this letter with one on CMA letterhead to Bowser that read:

The issue of whether the Child Health [and] Disability Prevention program should be funded in part with Prop. 99 health education funds goes back to initial implementation of the initiative. While members of the initial Prop. 99 coalition disagreed on this issue, a compromise was reached to fund CHDP from health education to ensure enactment and maintain a common front against the tobacco industry whose major objective was to eliminate the television advertising program. This initial agreement occurred two years prior to my joining CMA. As a legislative staff person at the time, I supported the agreement because the threat to the advertising program was very real. …

As tobacco tax revenues declined as a result of the many successful efforts following the enactment of Proposition 99…indeed, including efforts of the Heart Association…competition for fewer dollars became intense, and what was once considered a compromise became an “illegal raid” on the tobacco education account. …

Through legal counsel, I requested (in addition to Dr. Lewin's request), that you apologize for your untrue advertisement. As the attachments indicate, you have no intention of doing so. In fact, while litigation was never mentioned in Ms. Miller's letter to you, you threatened to counter sue (“slap-suit”) if I chose to pursue the issue legally. Outside of fulfilling an enormous emotional need…which will stick in my craw for a long time to come. …I don't believe litigation will result in civilizing this debate. I believe you've done your cause an enormous disservice and hope you reflect on the value and ethics of your current tactics.[25]

Thompson also defended Governor Wilson, who, in his view, “was also unfairly smeared in your ad.”[25]

Adams was sure that her new offensive was going to get her organization sued, although Bowser shrugged off the Thompson letter as bluster. Carol and Glantz passed the threatening letter on to the San Francisco Chronicle and it made news:

Darts, not hearts, are flying this Valentine's Day between the American Heart Association and organized medicine: The nonprofit group claims that California doctors have run off with Governor Wilson and the tobacco industry.

The latest spat—nasty even by Sacramento standards—began two weeks ago when the California office of the American Heart Association signed a newspaper advertisement “nominating” Wilson and the California Medical Association lobbyist Steve Thompson to the “Tobacco Industry Hall of Fame.”… Wilson was not amused by the ad. And Thompson—one of the most prominent figures in the state capital—had his personal lawyer fire off a demand for a retraction.

Dr. Jack Lewin, executive director of the California Medical Association, called the name-calling “unconscionable” and “slanderous” in a letter to the heart association and threatened legal action if more advertisements appear.

“The heart association will print no retraction,” said Mary Adams, chief lobbyist for the California charity.

Adams said that the association will forge ahead with a publicity campaign that challenges doctors' roles in the battle over anti-smoking programs. “This is a diversion from the American Heart Association's way of doing business, but that just underscores the importance we attach to this,” said Adams. “It's time to get this issue out in the open.”[26]

The media was finally paying attention to Proposition 99 again.

The fact that AHA had allied itself with the “radicals” at ANR also interested the media. Steve Scott of the California Journal observed,

The Heart Association's participation was crucial to the credibility of those ads. ANR is a wonderful organization. They do a lot of good stuff but they are viewed by the Sacramento press, which winds up covering this, as kind of the radicals. They're the ones who are beating the drums. When the Heart Association came on, then all of a sudden you had this group that is perceived as “centrist,” one of the moderates. So one of the moderates had gone over to the other side and all of a sudden you had a situation where the voluntaries couldn't claim unanimity. Lung and Cancer couldn't say, “Oh well, ANR—they're just out there on the fringes.”[4]

Thompson also apparently mobilized support from other medical groups. The California chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the California Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the California Society of Plastic Surgeons, and the California Society of Anesthesiologists all responded to the “Hall of Shame” advertisement by writing an open letter to the California senators and Assembly members to lampoon the same “hit list” of projects that they had lampooned in 1994 during the hearings on AB 816. The letter from the specialist groups made it sound as though the same old fight about money was about to surface again.

CMA lobbyist Elizabeth McNeil was unhappy with the advertisement, not only because it attacked the CMA but also because she felt it would make Wilson more intransigent:

The first ad was pretty devastating as far as moving anything politically, and we thought that shut the door completely to doing anything. …I think that turned off a lot of people, not only in the Capitol but around here. I think it was a very stupid move politically. I think it hurt his kids, hurt his family, and he's been someone who has always fought for kids' programs and health programs. …But it just dug the governor in. The governor called up Steve and said, “Forget it, I'm not going to compromise on this and all conversations are off, basically.”[27]

The AHA and ANR shrugged off these criticisms. They purposely had designed the ad to get people's attention, believing that it was better than being ignored. Isenberg thought the 1996 advertising campaign had value, and he also confirmed that it enraged Thompson: “Thompson was beside himself. God, he was so mad. My wife took…the one with Steve in it. She altered it a little bit and said, `Steve Thompson, drug dealer' [laughter]. Anyway, Steve didn't think that was very funny. Well, it's like everything else in politics, it escalates the battle. It certainly irritated Wilson, agitated the California Medical Association. Did it have some impact? Might have had some impact, together with the second lawsuit.”[22]

The Wellness Grant

In March the California Wellness Foundation, which had financed the voter education campaign about Proposition 188, gave the ANR/AHA media strategy a huge shot in the arm: a $250,000 grant to run a series of advertisements on the status of the Proposition 99 Health Education and Research programs and their importance. The campaign was not designed to lobby for any particular piece of legislation, but rather to educate and involve the public in the debate over the future of Proposition 99.[28]

The Hall of Shame ad had attracted the attention of Herb Gunther, director of the Public Media Center in San Francisco, which had run the nonpartisan advertising campaign on Proposition 188 with a grant from the Wellness Foundation a year earlier (see chapter 11). Gunther had been interested in helping restore the integrity of Proposition 99 but had not met any credible players with whom to work. The fact that the AHA had adopted such an aggressive approach impressed Gunther, and he arranged a meeting between Glantz and Wellness Foundation president Gary Yates to discuss Proposition 99. Glantz later described the meeting in an interview:

Gary basically said, “I know what you want. You want some money to run ads about Prop 99 and I had thought it over and decided not to do it.” I had pitched the idea to him at the meeting after an adequate amount of wine, and my whole idea of engaging the public. They had just come off this victory in [Proposition] 188 and really shown a whole new way foundations could play a positive role in public health. I basically said we wanted to do something like the 188 campaign and that the Heart Association was showing some guts. And it turns out that Wellness had been kind of watching. Tobacco isn't one of their priority areas, but they'd been watching Prop 99, wanting to do something to help and not seeing any place to put the money, because they looked at it as the same old same-olds, making the same old mistakes.

And they had noticed the [Hall of Shame] ad, too. And they had seen the article about the threats from the CMA, too, and were impressed by that. And were impressed that the Heart Association was willing to do it. ANR had a very good reputation with them for some other projects they'd been involved with.

And in the end Yates said, “Okay, I'm interested in doing this.” And he looked at Gunther and he said, “How much money is this going to take?” And Herb said, “A hundred thousand dollars.” And then Yates looked at me. I mean, that was more money than I had thought we had needed at the beginning. And then Yates looked at me and he says, “You know, you don't take on the CMA and the governor and lose. How much do you need to win? Can you win for a hundred thousand dollars?” And I said, “I'm pretty sure.” And he said, “I don't want to be pretty sure. I want to be sure. How much do you need to be sure?” And I thought for a minute, took a deep breath, and said, “A quarter of a million dollars.” And he looked at me and he said, this was about nine-thirty on a Thursday night, and he says, “I want a grant on my desk by five o'clock Tuesday morning for $250,000. I want ANR Foundation to be the fiscal agent. And you work it out with them and Heart and the Public Media Center.” So we had one hysterical weekend of putting together this proposal.[7]

The resulting grant to ANRF paid for a series of advertisements to be developed by the Public Media Center in concert with Glantz, ANR, and AHA. The ads were to appear in major California newspapers and discuss issues surrounding Proposition 99. In addition, there were funds for public opinion polling and grassroots education. Gunther knew the hard-hitting advertisements would be out of character for the voluntary health agencies: “Our side invariably thinks the only way you win is by being nice, and the voluntaries are into that. I mean certainly around tobacco issues, it's been about, `Oh, you know, I hope my back isn't hurting the heel of your shoe, Governor. We really appreciate your standing on us in this way. Let us know what else we can do to make you even more comfortable.' And that's the approach the voluntaries have had.”[29]

Carol invited ACS and ALA to a meeting at the Public Media Center to discuss the strategy and encourage their participation. Beerline, however, had very little interest in Gunther's approach:

At the ad agency that was going to run their campaign, we had a major meeting. And all the players were there and we spent a lot of time talking about our differences on how we wanted to run the campaign and basically what we agreed upon at that point in time [was] that there was no way that we could come together on this. So ANR and Heart would wage their campaign, we would wage ours, we would keep each other informed. They felt very comfortable about the type of campaign that they had in mind and we dubbed it the “black hat.”…We said, “Okay, but we're not going to do it and we can see that this might present some political problems in Sacramento and we're going to have to distance ourselves from you.”…But there was just no other way that we could reconcile it because of the extreme difference in the way that we were planning to run our campaigns.[8]

While ACS and ALA tried to work within the existing power structure (which included the CMA), AHA, ANRF, Glantz, and Gunther started trying to change it. Their first goal was neutralizing the CMA.

The CMA House of Delegates Meeting

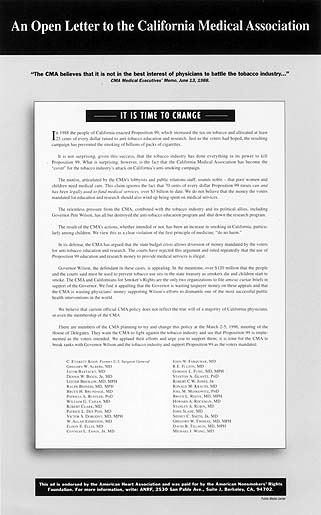

AHA and ANRF believed that the CMA's pro-tobacco position originated with its political leadership and did not enjoy particularly broad support among its physician members. To force the issue, they ran a full-page ad in the California edition of the New York Times on February 29, 1996, during the CMA's annual House of Delegates meeting. The advertisement was an “open letter” signed by former surgeon general C. Everett Koop and other physicians and scientists telling the CMA, “It is time to change” (figure 17). The advertisement helped stimulate a major floor fight over CMA's position on Proposition 99. Roger Kennedy, a physician from Santa Clara County who also served as chair of his local tobacco control coalition, was involved in the floor fight and later recalled, “It really became clear that we were not going to win based on the resolution, which was a very definite statement that the CMA should change its position…but I think that we got what we could. In retrospect, I'm sorry I didn't push harder. …I think that going down to flaming defeat in the face of the public may have accomplished more in the long run. …There's no question that the leadership of the CMA was not going to take a firm position that they would absolutely oppose any reallocation of funds.”[30] ALA was working through its own doctors who were CMA members to get a resolution supporting full funding. According to Najera, “We took this to the public to make it a public debate at the House of Delegates. We literally organized a public debate for what I would say was the first time on the floor of the board, of the House of Delegates for CMA.”[2]

Figure 17. Newspaper advertisement designed to change the CMA's pro-tobacco position. The American Heart Association and the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation ran this advertisement in March 1996 during the CMA's annual House of Delegates meeting to stimulate discussion on the CMA's stance on tobacco issues. It helped precipitate a vigorous floor debate that marked the beginning of changes in CMA policy. (Courtesy of the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation)

The eventual CMA resolution was less than the public health advocates wanted. On March 3, 1996, the CMA House of Delegates voted to support full funding of Proposition 99's Health Education and Research programs if the governor and Legislature were willing to fund the “challenged programs” from the state General Fund.[31] If the governor and Legislature refused to use the General Fund, the CMA would continue to accept Proposition 99 funds for these programs, despite the court rulings. The CMA refused to withdraw its friend of the court briefs in support of the governor's position on AB 816 and SB 493. But in April 1996 the CMA did release a statement announcing its opposition to the governor's proposed budget concerning the use of the Health Education and Research Accounts to fund medical services.[32] Lewin saw the House of Delegates vote as representing a “fairly dramatic” change:

I think that the change was because I'm a new leader and I was able to go directly to the doctors in the CMA and ask them what they wanted, what they believed in. And it was very clear that they were quite willing to support education and research as well as indigent health care and that they hadn't been asked the question in that way, that they didn't think you should undermine education for indigent health care. But they didn't think you should cut indigent health care to enhance education. Their strategy was that all of these things were too important and that the state had enough resources to do all three of these things and do them well.[10]

The CMA joined the ACS/ALA's Coalition to Restore Proposition 99, a decision that had the effect of isolating the governor. According to CMA lobbyist Elizabeth McNeil, the CMA action not only isolated the governor but also “showed them [the administration] and all these other groups, we're going work for something else and that isolated them, which made it difficult for them. In some ways made it more difficult for us to bring them around because they were a little upset with us about that.”[27] The CMA's changed position made it less likely that the governor and tobacco industry could use medical necessity as the excuse for gutting the Proposition 99 Health Education and Research programs.

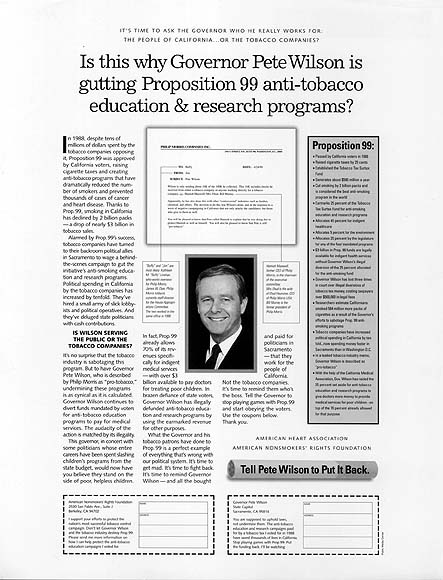

The Philip Morris Memo

One of Wilson's major responses to the criticism that he was pro-tobacco had always been that he took no direct campaign contributions from the tobacco industry. This claim ignored the fact that the tobacco industry was a major source of money for the California Republican Party—$165,727 in the 1995-1996 election cycle[16]—and that Wilson was the political leader of California Republicans. In any event, Wilson's defense hit a major snag when ANR obtained a March 4, 1990, internal memo between two Philip Morris lobbyists in Washington reassuring company executives that Wilson's act of returning some campaign contributions from the company did not mean that he was anti-tobacco. The Philip Morris lobbyists reported:

Wilson is only sending about 16K of the 100K he collected. This 16K only includes checks he received either from a tobacco company or anyone working for a tobacco company, i.e., Hamish Maxwell [CEO and chairman of the Philip Morris Executive Committee], Mrs. Ehud [wife of Ehud Houminer, CEO of Philip Morris USA], Bill Murray [former president of Philip Morris].

Apparently, he has also done this with other “controversial” industries such as lumber, chemicals, and others. The decision to do this was Wilson's alone, and in response to a wave of negative campaigning in California that not only attacks the candidates, but those who give to them as well.

You will be pleased to know that Pete called Hamish to explain that he was doing this to protect Hamish as well as himself. You will also be pleased to know that Pete is still “pro-tobacco.”[33] [emphasis added]

Wilson first saw the memo when he was being interviewed on camera by correspondent Peter Jennings for an ABC news special on tobacco. Wilson did not immediately say the memo was a lie, which limited what his staff could say later. (To the disappointment of many California tobacco control advocates, the exchange was not included in the final broadcast.) The memo, and the fact that the $84,000 retained by Wilson came from a variety of advertising agencies, law firms, and others who worked for the tobacco industry, received wide media coverage.[34-37]

ANRF and AHA also featured the memo in their first full-page advertisement attacking Wilson for diverting Proposition 99 anti-tobacco money into medical services, which ran on April 16 in the New York Times, and later in the Sacramento Bee and Los Angeles Times (figure 18). The advertisement reprinted the original memo and asked the question “Is this why Governor Pete Wilson is gutting Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education and research programs?” The ad also posed this question: “It's time to ask the Governor who he really works for: The people of California or the tobacco companies.”

Figure 18. Newspaper advertisement attacking Governor Pete Wilson for his pro-tobacco policies. The American Heart Association and the American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation ran this advertisement in California's major newspapers to educate the public and media about what had happened to Proposition 99 and to focus attention on Governor Pete Wilson's role in dismantling the Tobacco Control Program. (Courtesy of American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation)

The tension between the ANRF/AHA and the ACS/ALA's Coalition to Restore Prop 99 was growing because the Coalition kept pressuring ANRF and AHA to tone down the attacks on Wilson. On April 29, after the advertisement featuring the Philip Morris memo ran, Coalition co-chairs Beerline and Martin wrote to the presidents of ANR and AHA calling on them to work to restore Proposition 99 “in a more positive way utilizing its media campaign to inform and educate the public on the real issues regarding the restoration of Prop. 99 funds.”[38] ACS and ALA still hoped that the Legislature and the governor could be convinced to support the program with “a plethora of data and new information that will prove convincing and effective in restoring these important funds.”[38]

They distributed their letter to the governor, the Legislature, and the media. According to Martin, they felt that they had to write the letter to “everybody” to say that they had nothing to do with the advertisements:

Basically we said, “We share the same goal, there's no doubt about that, but your tactics and our tactics are not the same. We will pursue a positive campaign and we are notifying everybody that we have nothing whatsoever to do with those ads.” And we hand-delivered that to the governor's office and we made a lot of phone calls saying, “Look, we don't have any control over the ads, there's nothing we can do about them. This is being done by these two groups and these two groups alone, period. We're out of this.” And actually we finally did get that message across. I think that if we had not separated ourselves from those ads, we would have been dead politically at the Capitol.[39]

Carol found the letter highly offensive: “The tone was very patronizing, the whole `we're glad you share our goals.' Not `we're glad we have the same goals,' not `we recognize that your goals are the same as ours.' `We're glad you share our goals. You're welcome to share our goals.' We're welcome to join their coalition. We're welcome to sit at their table. Of course, we're not really welcome.”[3] The whole point of the ANRF/AHA campaign was to avoid sitting at tables.

The Governor's May Revision

Meanwhile, as the disagreements among the parties in the field were playing out, competing bills were being introduced in the Legislature on how to implement Proposition 99. The Senate Health Committee considered two bills on April 17, the day after the media stories broke about the memo calling Wilson “pro-tobacco,” and both were passed out of committee, including one sponsored by Senator Diane Watson (D-Los Angeles) requiring full funding. The Assembly Health Committee passed a full-funding bill sponsored by Assembly Member Katz on April 23 by a 12-1 vote. (After the hearing, several other members signed on to the bill, resulting in a 15-1 vote in favor of the bill.) McNeil believed press coverage of the issue the day before in the Los Angeles Times played an important role in convincing the chair to let the bill out of committee. The Times reported that the chair of the Assembly Health Committee, Bret Granlund (R-Yucaipa), who had been quoted as saying, “I'm a free enterprise, no-tax smoker,”had taken at least $44,500 in tobacco industry campaign contributions.[40] According to McNeil,

There was heavy-duty, behind-the-scenes lobbying with the CMA and the chairman of that committee to get that bill moved out. Ten minutes before the bill was heard, I was out in the hallway with the Assemblymen Katz and Brett Granlund, the chair. …he was getting some bad press in the L.A. Times at the time, which really helped. And I just said, “Well, look, this is going to go through the budget process and you're going to look terrible for not allowing this issue to move through the process and holding it up, and it's got a long ways to go and you're going to be criticized and seen as pro-tobacco, and there's no reason to do that.”…So he agreed to let it out of committee. He had to signal that to the rest of his caucus to get it out because otherwise that bill was not going to come out.[27]

Under such scrutiny, the Assembly Health Committee was unwilling to vote publicly against Proposition 99's Health Education and Research programs. The bill later, however, stalled in the Assembly Appropriations Committee and died without a vote.

The Assembly Appropriations Committee passed the governor's proposal contained in his May revision of the budget. (The May revision is considered the governor's “real” budget because it is adjusted to reflect new economic data.) In the May revision, Wilson proposed releasing $147 million in reserve Proposition 99 funds, including $33 million in the Health Education Account and $41 million in the Research Account, with the rest for medical services. The funds were available due to higher-than-expected revenues (because tobacco use was no longer falling, partially as a result of cuts in the anti-tobacco program) and underspending in several Proposition 99 medical programs, including ones illegally funded out of the Health Education Account. The additional $74 million in spending on Health Education and Research was to be a one-time expenditure. The governor was still not willing to allocate all of the Proposition 99 money as specified in the initiative. All of the new monies were to target youth, which was justified by the release of data showing that in 1995 adult smoking prevalence had dropped from 17.3 percent to 16.7 percent while youth smoking prevalence had risen again, this time from 10.9 percent to 11.9 percent.[41]

Reaction to the Governor's New Budget

The reaction to the governor's proposal was mixed. AHA and ANRF responded with a new full-page advertisement headlined “The tobacco industry knows that the best way to get kids hooked on cigarettes is to say they're for `Adults Only.' Why is Pete Wilson using tax dollars to help them?” The advertisement took issue with the governor's plan to focus on youth and argued that strategies that focused only on youth played into the tobacco industry's efforts to hook young smokers. The tobacco industry, according to internal memos, tries to attract young smokers by presenting the cigarette as “one of the initiations into the adult world” and as “part of the illicit pleasure category of products and services.”[42] Smoking is linked to the illicit pleasure category through alcohol consumption and sex.

Not surprisingly, the Coalition to Restore Prop 99 took a more measured approach: “We are encouraged the Governor has recognized the importance of funding tobacco education, prevention, and research and believe he has taken a critical first step. However, we have very serious concerns about his proposed programmatic changes which may not be consistent with Proposition 99.”[43] In a separate memo to ALA directors and staff, Caitlin Kirk, director of communications at ALA, and Najera commented that “although the proposal is a positive step, we have serious concerns and many questions about the details. We are quite concerned about the overall effectiveness of a tobacco control program that would require all funds to be spent on youth-focused education and research projects.”[44] Knepprath explained,

Our coalition was very unified against the revise. We put out a “reject the revise” fact sheet to the Legislature and flogged that around. And I think that helped CMA maybe soften its position on that. …I think their posture on it was “Let's be more positive about it and try to work out our differences.” We were saying, “Uh-uh, this is bad on its face. Go back to square one.” We were able to, I think, through our combined efforts to convince [Senator Mike] Thompson and the budget committee that there needed to be a different approach to using the supplemental funds.[2]

While differing in how aggressive they were willing to be, the AHA/ANRF and ACS/ALA camps were converging on their policy goals. The CMA, while a member of the ACS/ALA coalition, was also acting independently and had probably helped negotiate the governor's position in the May budget revision.[9] The CMA was not waiting for the Coalition as a group to act before going to the governor.

The objections of the health groups were getting the media's attention. On June 3 the San Francisco Chronicle carried as its lead editorial “Smelling the Smoke of Governor's Plan,” which criticized the governor's May revised proposal:

Governor Wilson recently proposed a compromise that would shift $147 million of previously diverted Prop. 99 funds to tobacco education programs, but that would still fall short of the 20-percent level approved by voters. The Governor's plan also limits the education spending to programs aimed at teenagers, instead of a broader approach. Also, his proposal is a one-year deal, leaving tobacco education funding vulnerable to vagaries of future budget conditions. …The Katz and Watson bills reassert the state's long-term commitment to fight smoking. California voters delivered the mandate—and the money—eight years ago. This effort must not be undermined by Wilson and other friends of tobacco in Sacramento.[45]

On that same day, TEROC met and DHS director Kim Belshé came to the meeting to defend the governor's proposal. Jennie Cook, chair of TEROC, along with other committee members, echoed the public health groups' concern about focusing so exclusively on youth. The program, according to Cook, worked best when it included youth, communities, and adults all together. According to Belshé, the decision on how to spend the dollars was based on smoking rates. For the previous two years there had been an increase in the rates of smoking for youth. But what also emerged at the meeting was that for the second half of 1995 adult rates were also increasing. For the first six months of 1995, the percentage of adults that smoked was 15.5 percent but in the second six months this figure went up to 17.9 percent. Reporting the overall figure of 16.7 percent for the year disguised the uptick in adult smoking.[46] Several major newspapers reported on the apparent effort to disguise the upturn in the adult smoking rate, creating more bad publicity for the administration.[47][48]

In the Capitol, Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee staffer Diane Van Maren was working with Senator Mike Thompson to develop their own budget proposal: