12. The End of Acquiescence

By the beginning of 1994, California's tobacco control movement had become a national and international model of how to use community-based programs and media to reduce tobacco consumption and exposure to secondhand smoke: 334 communities had passed local tobacco control ordinances, and the Legislature was close to passing AB 13, which would require virtually all workplaces in California to become smoke free. California had the third-lowest per capita consumption of tobacco of any state, and the reduction in smoking in California was costing the tobacco industry hundreds of millions of dollars in lost sales every year. Despite the diversion of money from the Health Education Account and the Wilson administration's lack of enthusiasm for implementing the anti-tobacco program, there was no longer any question about the effectiveness of Proposition 99's programs.

But the Health Education and Research Accounts were hardly secure. The 1988 election approving Proposition 99 was over five years old, and the strong public support for those programs, as reflected in the vote, was no longer as obvious as it had been when AB 75 had passed in 1989. The June 30, 1994, sunset of the legislation that authorized Proposition 99 expenditures—AB 99—meant that new authorizing legislation for Proposition 99 would have to be passed in 1994. Thanks to the governor's veto of SB 1088 late in 1993, both the Research Account and the Health Education Account were at risk in 1994. Indeed, Assembly Member Phil Isenberg

Program advocates had three important things working in their favor: the success of the program (and thus a growing confidence in those who were running this major anti-tobacco campaign), the continuing popularity of anti-tobacco policies and programs, and the existence of a program constituency that had been created in the field. Success at the legislative level required the ability to rely on all three. But 1994 was a bad year for tobacco control advocates to be dedicating either staff or funds to a campaign to preserve Proposition 99. They were stretched thin by the spring battle over AB 13 and the looming fall battle over Proposition 188. Despite the inability of the health groups to protect the integrity of Proposition 99 in the conference committee setting in previous years, they once more agreed to a conference committee, again headed by Isenberg. Reauthorization was to be another insider deal.

The Governor's 1994-1995 Budget

Repeating the pattern he had established in prior years, Governor Pete Wilson drew up a budget that again called for diverting Health Education and Research funds to medical services, only at a higher rate. Perhaps in response to the bad press that the administration received when the American Lung Association (ALA) won its case over the media campaign, Wilson proposed giving the media campaign Section 43 protection, which meant that the media campaign would not be cut to get money for the protected medical programs. This decision would mean, however, that the local lead agencies (LLAs) and other local programs would be hit even harder by any Section 43 reductions. Following caseload adjustments and diminishing revenues, the governor's budget cut LLA funding from $20 million in 1993-1994 to $15 million in 1994-1995, competitive grants were dropped from $15 million to $10 million, and funds for schools from $22 million to $16 million. In total, the governor proposed that Health Education programs get only 12.7 percent of the total tobacco tax revenues instead of the 20 percent required by the initiative.

In the governor's budget summary under “Preventive Services” the tobacco education program was not mentioned, despite its success. Instead the governor mentioned Healthy Start, Access for Infants and Mothers (AIM), and Education Now and Babies Later, among others. In describing the need for perinatal substance abuse services, alcohol and other drugs were specifically mentioned, but not tobacco.[2] The Wilson administration had no desire to draw public attention to tobacco.

Wilson also tried to quiet opposition from the ALA and Senator Watson's office. A top Wilson administration official held a secret meeting in which she threatened to “cripple” the implementation of the Proposition 99 programs if Najera and Miller did not accept the diversions demanded by Wilson. Wilson's representative threatened to seek out “the most stupid, incompetent, belligerent bureaucrats” she could find and put them in charge of tobacco education. Further, all the committed and effective members of the TCS staff would be reassigned to a regulatory “Siberia.”[3] In fact, although the TCS staff was not replaced, the Wilson administration had already slowed the media campaign and would continue to hobble the program administratively until Wilson left office in 1999.

The hypocrisy of the argument that the state's budget problems made it necessary to divert money from the Health Education Account to medical services was exposed when the Legislative Analyst reviewed the governor's proposal for AIM. The analyst noted that AIM, the program which provided subsidized private health insurance for poor pregnant women, cost more money than providing the same services through MediCal, the state's Medicaid program. Moreover, AIM yielded worse clinical outcomes than MediCal.[4] Thus, the state was paying more money to get worse outcomes in terms of serving this population. The analyst proposed that AIM be discontinued and the services be provided by expanding MediCal eligibility.

Implementing the Legislative Analyst's proposal to switch from AIM to MediCal would have saved $74 million dollars, more than was being diverted out of the Health Education Account. Thus, changing programs

The Creation of AB 816

Isenberg had generally been able to win consensus over the expenditure of Proposition 99 funds in prior years. In January 1994 he telephoned ALA lobbyist Tony Najera to discuss the reauthorization. Isenberg wanted Najera's viewpoint on whether he should again chair the conference committee that would handle Proposition 99 reauthorization through a bill named AB 816. According to Najera,

Phil Isenberg called me personally. I can just remember the day so clearly in the first week in January. He said, “Tony, I've been encouraged to carry the ball and to chair a conference committee and to carry the bill on reauthorization. What do you think I ought to do?” I encouraged him to do it because I remembered my days with AB 75, that he was in fact one of our champions. He also had been the chief engineer in previous reauthorizations which I thought were a fair process. The process really really broke down during the AB 99 process and it was never recaptured for AB 816. So for me I encouraged Isenberg…and I said, “I think what you need to do is have a conference call with me, CMA, Western Center [for Law and Poverty],” and I did. That was to me the turning point in terms of what role I saw he was going to want to play for this.[5]

According to Najera, Isenberg was willing to chair the committee if there was “agreement amongst all of us,” which meant that the principals agreed to the status quo.

When interviewed later, several of the principals had differing views of what this “agreement” had been. To Isenberg, “status quo” meant that everyone agreed to use the process that had been used with AB 75 and AB 99—a conference committee and behind-the-scenes deal-making.[6] Thus, while “status quo” also likely meant continued dwindling of funds for Health Education and Research programs and another “insider” deal, this deal had not been explicitly struck. When asked if she perceived that a deal had been made early with Isenberg, Elizabeth McNeil, the CMA's chief lobbyist on Proposition 99 in 1994, said she thought the status quo which had been agreed to included the maintenance of the AB 99 funding pattern. According to McNeil,

We had lots of meetings with Tony [Najera] and John [Miller], the hospitals, us, and the Western Center about Prop 99 reauthorization. At the time, we all felt going in that pretty much trying to do status quo and make sure it was reauthorized was kind of the program. And later on, the Lung Association and others decided no, they didn't want to fund CHDP. They wanted it out and they wanted increases for their programs. So we do feel like that was not the plan that we all went in with when we asked Isenberg to sponsor the bill. That's strongly how I felt about where we went in. …I don't know if there was miscommunication. It wasn't articulated strongly where his groups were really coming from. I think he [Najera]'s sensitive too because he was part of the group that authorized the original CHDP expenditure and was criticized for doing that, and I think was really feeling that criticism. So the tune changed and it was a problem amongst all of us.[7] [emphasis added]

The ALA's name appears with the CMA, California Association of Hospitals and Health Systems (CAHHS), and the Western Center for Law and Poverty as supporting the version of AB 816 that the Senate and Assembly voted into the Conference Committee. The bill extended the sunsets for both the program authorizations and the program appropriations to July 1, 1996, and also authorized the expenditures from the Research Account.[8] Senator Diane Watson (D-Los Angeles), the longtime champion of the Health Education Account and John Miller's boss, voted for AB 816 at this stage.

According to Najera, he and Miller had agreed to a quiet strategy of letting the Legislature make its decision and then taking the issue to court. He said, “We were not demanding [full] 20% [funding for Health Education] initially. We were prepared to do what we had to do in order to get it out of here and take it to the courts, and let the battle be there and not in here.”[9] The voluntaries hoped that Wilson would not win reelection and that a new Democratic governor would be more sympathetic, ignoring the fact that opposition to the anti-tobacco education and research programs in the Legislature was spearheaded by Speaker Willie Brown, a Democrat. In any event, Wilson won reelection later that year.

Objections to CHDP

The early commitment by Najera and Miller to maintain the status quo and accept continued diversions of funds from the Health Education Account to CHDP and other medical services ran into trouble with the constituency that Proposition 99 had spawned. The Sacramento-based lobbyists were not used to considering the grassroots in their thinking.

These two cultures clashed in October 1993 at the California Strategic Summit on the Future of Tobacco Control, a two-day meeting funded by the California Wellness Foundation to develop recommendations for the Legislature regarding reauthorization. Four major recommendations emerged from this conference: (1) the new legislation should authorize the program until the year 2000, (2) the diversion of Health Education monies into medical services should stop, (3) the Health Education Account should receive 20 percent of the tax money, as the voters mandated, and (4) Section 43 should be dropped.[10] The program constituency was tired of compromise. There was a strong feeling that Najera and the chair of the Tobacco Education Oversight Committee (TEOC), Carolyn Martin, who argued against the meeting's recommendations as being unrealistic, had already agreed to maintain the status quo in 1994. The conference forced the issue of demanding the full 20 percent of revenues for anti-tobacco education. There was pressure to fight a hard and public fight.

The public health groups also came under pressure from a study commissioned by the Department of Health Services (DHS) to examine the structure of the Proposition 99 program.[11] The committee preparing the study was chaired by Dr. Thomas Novotny of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the School of Public Health at the University of California at Berkeley. The central conclusion of the report was that the greatest threat to the tobacco education program was the “lack of will on the part of the government to implement the Health Education Account as originally mandated by the voters.”[12] (The draft of the report went to DHS in December 1993, but it was not released until February 1994. Health groups suspected that the release of the report, which was critical of the governor, was delayed until after Kimberly Belshé was confirmed as head of the DHS.[13]) The second threat was the “failure of key constituent groups to hold the government fully accountable to the will of the voters.”[12]

The ALA's position on Proposition 99 hardened. In an Action Alert sent by ALA on February 16, 1994, ALA urged recipients to write the members of the Conference Committee and request the following:

- the removal of Section 43.

- the removal of CHDP funding.

- removal of the requirement that 1/3 of LLA money go to perinatal funding.

- full 20% funding of health education.[14]

The boards of the ALA and the California Thoracic Society (a related medical association) adopted motions that they would not accept less than 20 percent funding for the Health Education Account.[15]

But taking a firm stand did not necessarily translate into an effective strategy. Paul Knepprath, who was working for ALA-Sacramento/Emigrant Trails during the 1994 fight, was advising the state-level ALA on media strategies and was urging them to be more public and confrontational. On March 18 he wrote to Miller and Najera to alert them that “time is running short on our opportunity to generate media on the Health Education Account.” Knepprath continued, “Taking the offensive is critical. To do so, we need to create some waves, and plant the seed in the minds of conferees and other members that `hey something's going on with that tobacco tax conference committee.'…It may not be comfortable, but we have got to raise a stink if we want anyone to pay attention. Without the controversy, we don't have much hook and all the letter-writing will fall on deaf ears” (emphasis added).[16] In spite of Knepprath's advice, ALA did not pursue a more aggressive public stance. Mary Griffin, a contract lobbyist who had been at the state Health and Welfare Agency during the debates over AB 75 and was paid by Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR) to monitor the 1994 process, criticized this approach. When asked about the failure to stop the diversions in AB 816, she replied, “Dragging their briefcases through the Capitol building does not constitute lobbying. Sitting in a legislator's office saying, `Well, we really want this and blah, blah, blah,' it doesn't do it. Let me tell you, it doesn't do it. You need to lobby. That means using every resource at your command. It means getting your folks to give. Don't put out a letter and think your alert is going to go drum up the word. It doesn't work that way.”[17]

As the process proceeded, the health groups began to vigorously object to CHDP and the other diversions from the Health Education Account. They were, however, hampered by their previous agreements to divert funds out of Health Education and into medical services. When asked about the CHDP compromise, Cathrine Castoreno, a lobbyist with the University of California, made the distinction between the CHDP compromise and other compromises that are typically done in the legislative arena:

Precedent is a powerful thing. …There are some cases where you compromise on stuff that you care about and it presents no tremendous risks. But they weren't just compromising the program, they were compromising the integrity of that statute. And once you agree to disregard the law, you're sucked in because there's no one who has greater disregard for the law than the legislators. And it's impossible for you with any credibility to go back and say, “Well, I agreed to break the law last year, but I don't want to do it this year.”[18]

Isenberg was perceived by many parties to have been more hostile to the Health Education and Research Accounts in 1994 than in prior years. In a 1997 interview, Isenberg said that what really irritated him in 1994 was that representatives of the voluntary health agencies tried to argue that they had never supported the diversions into CHDP:

The part that I found most objectionable from the non-profits is they…said, “We never agreed to the first allocation, we didn't agree to the second allocation. You did it over our dead bodies.” That is not true…and one of the problems with that posture, which has served them politically in many ways,…is that…this was not a case of a fifteen-year-old memory where nobody was left. This is where all the active participants were still there, and goddamn it, they were so angry, so bitter, so disappointed that they were misrepresenting the fact they signed off on the first deal. Well, in retrospect, they shouldn't have signed off on the first deal, although they would have been ignored had they not participated. There would have been other undesirable consequences that flowed from that. …If everybody knew then what they know now, that fight would have been exactly that issue.[6] [emphasis added]

The voter mandate of specific allocations to the Health Education and Research Accounts was no longer an issue. It was all about who was willing to deal.

Other key players also had some opinions about why Isenberg seemed so much more hostile in 1994. ANR's Robin Hobart observed,

He historically…had been very supportive of the health education efforts and then just totally turned about and was furious. And I really believe it's because he thought he had made a deal with Tony [Najera], that they were going to make that appropriation that way. Tony probably thought it was okay because it was going to be short term until the budget got better. And then when it turned out Tony couldn't really speak for the rest of the now many many players out in the field who were saying, “This is not acceptable,” I think Isenberg was just furious. He felt a deal had been made and now it wasn't being delivered on.[19]

Peter Schilla, the lobbyist for the Western Center for Law and Poverty whose priority was finding money to pay for health services for poor people, continued to be an extremely influential lobbyist working against

Somebody asked [Isenberg] in all the conflicting claims of the different sides on this dispute who did he believe. He said, “Peter Schilla is who I believe.” And Peter was a very credible figure, very highly regarded around here in the health care field. And CMA moves huge muscle on these things and I think I, in [AB] 816, underestimated who was driving this thing. I believed it was the tobacco industry with the medical providers along for the ride. And I think it was just the opposite now. But while the CMA has huge weight with certain members, Peter's influence was greater. CMA couldn't have moved Phil, but Peter could. …Most politicians understand that when the industry comes to them and asks them to do something, that it's in the interest of that industry. But when the Western Center, good guy/consumers'/poor peoples' defenders, comes and says this is the right thing to do, they tend to do it.[20]

In the face of a hostile Isenberg and concerted and talented opponents, tobacco control advocates had a difficult authorization fight ahead. One of Schilla's sources of power was his ability to both raise and solve problems, based in part on his in-depth knowledge of health programs and budgets. The voluntaries' lobbying staffs never developed the same level of expertise on these important technical details.

Isenberg was correct in pointing out that the voluntary health agencies had acquiesced in the previous diversions of Health Education Account money into medical services, including CHDP. They were now trying to change course five years into the program, which meant that they needed to account for the shift. A May 9 memo from the ALA Government Relations Office explained the change in ALA's stance: “CHDP's costs have grown so large that they now jeopardize the very existence of the Health Education Program. We can now support CHDP only by sacrificing the anti-tobacco education effort. Straight line projections indicate that the Health Education Program would be ineffectual in two years and disappear entirely in four years if it is forced to sustain CHDP. We simply have no choice but to insist that the Medical Services appropriation support CHDP—not Health Education.”[21] ACS's Don Beerline echoed this philosophy when he was asked in 1996 why the voluntary health agencies decided to refuse to accept diversions in AB 816: “We said that this is destroying the program at this point. In the previous diversions, the money did go to indigent care, that's consistently where it went. But it was such a smaller percentage,

But the tough stance in 1994 was about more than just the size of the diversions from anti-tobacco programs to medical services. One of the reasons why the Coalition came down so hard against the diversions in 1994 was that for the first time they acknowledged how little was being done for tobacco use prevention within CHDP. When asked about the decision to try to halt the diversions, TEOC chair Carolyn Martin explained, “The TEOC had worked very diligently to try and get information on what was going on in CHDP and, believe me, it was not easy. Dr. [Lester] Breslow especially and I were down there pounding on their door and eventually we figured out there was nothing to give us because they weren't doing anything. So I think that made a huge difference, plus the extent of the diversion. Suddenly we're talking about huge percentages and big drops in programs.”[23]

Martin was supported in several quarters on CHDP's lack of effectiveness as an anti-smoking program. Bruce Pomer, executive director of the Health Officers Association of California, wrote to Isenberg on June 21, 1994, protesting the planned diversions. He specifically criticized the latest effort to put Health Education Account money into CHDP:

Our concern is the deceptive nature of the proposal. The current health provider protocols ($150 million in CHDP) have never had their effectiveness assessed. The last assessment of medical anti-tobacco protocols found no demonstrable effect what-so-ever from physician provided anti-tobacco advice. We find it ironic that the medical industry now proposes expanding physician assisted anti-tobacco education, which has been found to be largely ineffective. Likewise, it should give one pause that these amendments are supported exclusively by the medical industry and that not a single health education organization considers the suggestion to have any merit.[24]

The California Tobacco Survey, the large survey of tobacco use in California conducted by John Pierce of the University of California at San Diego for DHS, failed to demonstrate any impact on smoking by CHDP.[25] In contrast, the survey found large effects from much smaller programs, such as the media campaign and the creation of smoke-free workplaces.

The Hit List

The passage of Proposition 99 and the infusion of millions of dollars into anti-tobacco education gave public health advocates in California the means to embark on a comprehensive public health program that

The tobacco industry peppered the program with public records act requests to collect detailed information on every aspect of Proposition 99, then used this information to prepare a “hit list” of unconventional Proposition 99 programs that distorted and ridiculed these programs.[28] Californians for Smokers' Rights (CSR), an organization fostered by RJ Reynolds and headed by Bob Merrell, objected to the programs as frivolous. He also accused the state of building and operating a “statewide political organization” that illegally spent tax dollars to lobby.[26] The CMA distributed a similar list to the Legislature and journalists.[29] And the promoters of the hit list were successful in getting their message out. Conservative San Francisco Chronicle columnist Deborah Sanders echoed the list's message with this jibe: “Pretend for a minute that you are a legislator—just for a minute, I'll try not to make this too painful. You are given a choice. You can spend $175,000 on prenatal care, or you can spend $175,000 on a `Ski Tobacco-Free' weekend at Kirkwood Meadows in Tahoe.”[30] A highly innovative, two-and-a-half-year program was, with the stroke of a pen, reduced to a boondoggle weekend. Another list made fun of some projects funded by the Research Account, such as a study of smoking and facial wrinkling in women. These lists became major tools for the tobacco industry and its allies in the 1994 reauthorization fight.

A similar hit list turned up in Massachusetts in 1992 and Arizona in 1994, where the tobacco industry was fighting initiatives modeled on Proposition 99.[31-35]

The ANR-SAYNO Lawsuit

Two players entered the debate over the future of Proposition 99 with the explicit goal of forcing the debate out of the Legislature and back into the public arena and the courts: ANR and the new organization Just Say No to Tobacco Dough (SAYNO).

ANR was increasingly critical of the approach that the voluntary health agencies were taking in Sacramento, which ANR viewed as gutless. ANR director Julia Carol described the voluntaries' AB 816 reauthorization effort this way:

Nobody was willing to fight. They're all still asking nicely. …the CMA was still eagerly grabbing the money and none of the voluntaries were willing to publicly slap their hands about it or to use any sort of clout. You know, in advocacy you have two tools. You have a carrot and you have a stick. The really good advocates figure out when to use which and how much, and whether you use both. What the voluntaries were using mostly was the carrot. They said they were doing an aggressive fight, but they didn't really know what that meant. …I think it means [to them] that every now and then they write a sort of tough letter that they don't publicize in any way. And that they speak up kind of boldly behind the scenes in closed-door sessions.[36]

If ANR was to get involved, it would be outside the Legislature's back rooms.

Attorney A. Lee Sanders, who had been executive director of California Common Cause in the 1970s, wanted to do something to discourage politicians from taking money from the tobacco industry. He had just formed SAYNO to encourage candidates for office in California to refuse such contributions. When he contacted Stanton Glantz for information on campaign contributions by the tobacco industry, Glantz expressed frustration that none of the health groups had sued to restore the integrity of Proposition 99. When Sanders expressed interest, Glantz put him in touch with ANR, which joined with Sanders because of the organization's belief in the power of outside strategies.[37] On February 2, 1994, SAYNO and ANR sent formal demand letters to the California State Treasurer and Controller, asking for the return of funds already diverted from the Proposition 99 Health Education Account and threatening to

On the morning of March 23, just hours before the Conference Committee was scheduled to meet to consider AB 816, ANR and SAYNO held a press conference in Sacramento to announce that they had filed a lawsuit against the governor, the Legislature, and others seeking restoration of the $165 million that had been diverted from the Health Education Account into medical services under AB 75 and AB 99 and attempting to stop future misappropriations. The lawsuit (ANR et al. v. State of California, Sac. Super. Ct. No. 539577) derailed the plan for a quick passage of AB 816.

Najera and the other lobbyists were furious. They believed that the ANR lawsuit made the AB 816 fight more difficult because the legislators did not separate ALA from ANR. Najera tried to distance himself from the suit, and an April 8 ALA press release announced that the American Lung Association of California “is not currently a party to, or involved in any way with, a lawsuit filed by Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights (ANR) and Just Say No to Tobacco Dough (SAYNO).”[38] Najera was still hoping for success at the inside game that ANR was disrupting.

The Conference Committee Hearing

The Conference Committee held its hearing on AB 816 on March 23, but most of the program advocates observing the process thought that they had little ability to affect the outcome. Isenberg used the hit list that CSR and the CMA had prepared and widely circulated (without attribution) to ridicule the program. According to Miller, those who wished to protect the Health Education Account were not given much of an opportunity to do so:

It was a fairly perfunctory hearing. …I mean, after berating us, they didn't take any evidence. Then Phil announced the findings that he intended to move the money out of Health Education into these other programs. And I remember Ken Maddy [Republican minority leader] was sitting next to him and Ken turned to him and said, “But we all agreed that that was not possible.” And Phil said something to the effect that “things are different now.” And I realized that that was the first Maddy knew they were going to go for four-fifths and that they were going to change it. It was a Democratic initiative, 816 was. …Maddy quickly realized what was going on and got on board in a hurry.[20]

Supporters of the health education programs were surprised to find that Isenberg was a leader in attacking the programs. Isenberg sought to paint the health advocates who were seeking to protect Proposition 99 as being just another special interest now addicted to public funding. Isenberg pointed out to a Los Angeles Times reporter that many of the same groups who were now fighting the use of Health Education Account funds for health screening and prenatal care programs had agreed to this use in the past. According to Isenberg, these groups “have taken on the garb of a religious crusade.”[1]

Martin, responding on behalf of the ALA, wrote that they were “shocked” by Isenberg's comments.[39] She pointed out that Proposition 99 funds distributed to ALA represented less than 4 percent of ALA's budgets from around the state of California and was only .001 percent of the 1993-1994 tax revenues. She argued that the appropriation should be made, not only because it was a voter mandate but also because the program had demonstrated its effectiveness. She pointed out that “criticizing a few programs cannot erase the tremendous total impact of this complex prevention program.” Neither ACS nor AHA took Proposition 99 money.

The University of California had generally been quiet about the Research Account, reflecting its position as a public body whose board of regents is chaired by the governor. This stance sometimes frustrated the university's allies. For example, in 1992 AHA officials had written to University of California president Jack Peltason to express their disappointment at the university's failure to oppose diversion of the Research Account funds and the hope that “the University of California will take a leading role in opposing such attempts.”[40] Put to the test again in 1994, the university would again play a cautious role.

UC lobbyist Cathrine Castoreno was frustrated trying to protect the Research Account in the 1994 hearings. University representatives testified on behalf of the Research Account—but without drawing any lines in the sand—and, in fact, worked to accommodate Isenberg. According to Castoreno,

I gave explicit testimony about what was most definitely illegal versus what they might possibly be able to do. This is a point in the proceedings towards the end of the Conference Committee on 816 where it was clear that there was going to be a diversion of Research Account monies. The issue was how much and how. We were pretty well beat up by that time…so, in an effort to try and keep the program from being completely defunded and to keep them from making a move that would be wholly illegal, I worked with our counsel and Dr. [Cornelius] Hopper [UC's vice president for health affairs] to put

― 260 ―together an analysis of 99 and see, given their goal to divert money, how they might do it legally. …We made it very clear that simply using the money straight out of the Research Account for health services or any other purpose was obviously and clearly illegal and challengeable in court. And they thanked us very much for that [laughter].[18]

The university even provided a written proposal on how the Research Account might legitimately be used for other purposes, such as by explicitly amending the initiative to put the diverted money into the Unallocated Account instead of directly funding medical care from the Research Account. The university's official position on reducing the Research Account from 5 percent to 3 percent was “neutral.”[41]

The schools were also subjected to a harsh review by Isenberg, who was frustrated by the lack of tobacco programming there. By March 1994, after the program had been running for four years in the schools, the evaluation conducted for the California Department of Education (CDE) by Southwest Regional Laboratory reported that 41 percent of youth in grades 7 through 12 reported at least one tobacco lesson and activity event.[42] This finding also meant, of course, that 59 percent did not, despite the fact that the schools had received a total of $147 million in Proposition 99 funds in the 1993-1994 fiscal year.[43] Through the spring of 1994 all schools were getting entitlement money based on average daily attendance. The report also pointed out that “the DATE [Drug, Alcohol, and Tobacco Education] program needs clear definition of the model and its components in order to standardize and focus prevention and reduction efforts targeting school youth.”[42] The health groups generally agreed with Isenberg's criticisms of the schools.[20]

The CMA

In 1992 Steve Thompson, who had served as Assembly Speaker Willie Brown's chief of staff and the head of the Assembly Office of Research, had moved to the CMA to become its vice president and head lobbyist. This job change put him in a powerful position from which to continue to advocate for the diversions out of the Health Education Account into CHDP, a program he had helped design years earlier while working for Brown. Brown and the tobacco industry were both interested in shifting Health Education and Research monies into other programs.

The CMA continued to portray its position as a painful choice between taking care of poor children and funding prevention programs that have a longer-term benefit. In the end, of course, providing money

The medical interests and counties warned the ALA that they intended to pursue a four-fifths vote in the Legislature to divert the Health Education and Research money into medical programs. In a private meeting hosted by the County Supervisors' Association, the CMA, the CAHHS, and the Western Center for Law and Poverty, among others, informed ALA and Miller that passage by a four-fifths majority vote would occur and threatened that, if the voluntaries did not accept the terms they offered, the health community would take the entire Education and Research Accounts. Najera and Miller refused and promised there would be “blood on the walls.”[3]

Whereas the Health Education Account had been under siege in previous authorization battles, the Research Account had been reasonably well protected. But in 1994 the CMA had the Research Account in its sights. Among other things, the program had funded studies on campaign contributions by the tobacco industry to members of the California Legislature as well as an analysis of the implementation of Proposition 99 highlighted the pattern of diversions of funds. This work angered Willie Brown, who demanded that the University of California stop this work.[45][46] Soon after the university refused, the CMA began attacking the Research Account as a waste of money and agitating to use the money for medical services.

Elizabeth McNeil, one of the CMA lobbyists, said that the CMA had neither prepared nor circulated the hit list of Health Education and Research

Research by far got the most criticism and they didn't do a good job at defending themselves…and they [the Conference Committee] took those dollars to balance the budget basically and fund some kids' health programs that I have to say are very worthy. And that was a tough call, but we did support the overall dynamics because of the political pressures on getting the budget and with budget deficits and the importance that we place on some of these indigent programs and when there was some frivolous research projects going on perhaps. …We really didn't support that shift being made, but in the end we supported the whole deal, felt like it was the best compromise we were going to get.[7]

Steve Scott of the California Journal reported, however, that he got the list from the CMA. More important, he saw CMA's support of the diversions as important to getting them through the Legislature:

The California Medical Association got successively more brazen in its approach and its willingness to kind of undermine the tenets of the education fund. I remember in the Conference Committee meetings on [AB] 816, Assemblyman Isenberg started rolling out the horror stories about the Research Account and how the Research Account was being used for these…ridiculous grants. And I got a list of those ridiculous grants from the California Medical Association. It was leaked to me through the CMA. …You talk to their lobbyist and she'll deny that they were openly advocating the diversions, that it was an unfortunate necessity that they had to agree to the diversions to make the tradeoff. But in truth they were right in there pitching subtly on the whole question of, and not so subtly, increasingly less subtly, on the issue of the problems with the Research Account. …So a lot of the pushing against the Research and Education Account, or in favor of more money going to direct medical services, was coming from the California Medical Association.[47]

In addition to attacking the Research Account, a May 1994 CMA report justified the use of Health Education Account monies for CHDP “due to the anti-smoking education component of the program.”[29] It reported that the administration offered “education representatives” a compromise—capping CHDP at $30 million a year—but were turned down. The report comments that some “questionable `education' projects,” such as anti-tobacco sponsorship of a ski program ($175,000), a race car ($200,000), and a high school rap contest ($175,000), led “many” conferees to believe that there was adequate funding of both the Health Education Account and CHDP. The projects that the CSR and the CMA used as examples of frivolous expenditures were some of the most innovative programs spawned by Proposition 99.[28][29]

Physician Roger Kennedy, a CMA member who worked throughout the nineties to get the CMA to support health education and the chair of Santa Clara County's tobacco control coalition, believed that the doctors had talked themselves into a bad position:

When the diversions occurred, I had a number of discussions with some very highly responsible people that I respect and have known for a long time…people who were in significant roles, people on the board, who were of the view that this money was so crucial to provide care for the kids in California. …But I think they fooled themselves into thinking that they couldn't take care of kids without this money. …This allowed them to overlook the fact that AIM program was, by everybody's analysis, extremely inefficient and was money that could have been covered in another way; MediCal would have been a much better way.[48]

Kennedy believed that the CMA should have been willing to call Wilson's bluff and saw two key reasons for the CMA's unwillingness to spend political capital on this issue. First, the CMA needed the governor's support on other important matters and did not want to alienate him on this issue. According to Kennedy, “It was the easier path to go that didn't require pushing Wilson and angering Wilson. The CMA leadership wanted to work with Wilson on other issues, and they felt that to push him on this would compromise their ability to work with him. At this point, he really had his heels just dug in. So they felt he wouldn't move on this or, if they forced him to move on this, it would harm them in other ways.”[48] Second, the CMA gives priority to the pocketbook issues of its members. As Kennedy explained, “The CMA has already been in trouble for a number of years in terms of membership because doctors' incomes are dropping and they don't see the value. So if the CMA isn't using its political clout to ward off the optometrists and instead is going along with making sure that the money from Prop 99 goes to fund tobacco education instead going into doctors' pockets, the CMA is going to look like they're not really supporting their members.”[48] Thus it was in the CMA's interests to support the same agenda that the tobacco industry had: further diversions of Proposition 99 anti-tobacco Health Education and Research money into medical services.

Last-Minute Efforts to Stop AB 816

There were some last-minute efforts to attract publicity to the Proposition 99 reauthorization fight. On June 2 the Coalition had a press conference

Today marks the beginning of the end of the world's most successful tobacco use prevention and education campaigns. …AB 816 destroys that program by diverting money earmarked by the voters for education (20% of the revenues of the tobacco tax) into medical care programs. This in spite of the fact that over 70% of the Proposition 99 revenue is already being spent on medical care. Organized medicine represented by the California Medical Association and California Association of Hospitals & Health Systems, and community clinic providers led by the Western Center on Law & Poverty has successfully hijacked California's tobacco education funds as well as the five percent designated for research.[53] [emphasis added]

ALA wrote members of the Legislature urging them to vote against AB 816, warning that “with the passage of AB 816, California's popular anti-tobacco research and education program will die a slow, painful death.”[54]

The governor personally intervened to kill the tobacco research program. According to Castoreno, she was abruptly ordered to halt the lobbying efforts: “I was busily conveying the university's opposition to the measure along with the voluntaries. The director [of the university's Sacramento lobbying office], Steve Arditti, came running into the hallways with a look on his face like somebody vital had died. And it shot a pain through my heart and he conveyed that the governor had just called the [UC] president—Peltason, at the time—to say that AB 816 was part of the budget package. It's absolutely important to him, he wanted it and we needed to stop opposing it.”[18] The CMA wrote legislators supporting the bill and presenting its passage as a routine extension of the status quo: “Except for the cuts to the research account, which were part of the

The Floor Fight

The tobacco and medical interests could control when AB 816 would be heard in the Legislature. ALA anticipated they would schedule the hearing just before the summer recess, when Legislators were eager to return home and unlikely to think much about proposals before them. The voluntary health agencies, knowing they lacked the clout to stop even a four-fifths vote in the Assembly, decided to concentrate their efforts on stopping the bill in the Senate. Miller believed that the core of liberal Democratic senators who truly cared about the issue would be tobacco control's best—indeed only—chance against the allied tobacco and medical interests.[3]

Isenberg took up AB 816 in the Assembly on the day before the summer break, describing the bill as a routine fiscal bill necessary to balance the budget and fund important health programs. Few members bothered to read the bill, only a handful abstained, and the measure passed out of the Assembly with the necessary four-fifths vote.

About two o'clock that same afternoon, Senator Mike Thompson (D-Santa Rosa) took up the bill in the Senate without ceremony—and it was immediately defeated. Thompson could not even achieve a majority, to say nothing of a four-fifths vote. The bill failed by a vote of 18-12. Thompson was dumbfounded, and he immediately left the floor to notify AB 816's sponsors and author.[3] The tobacco and medical interests and county governments were galvanized into action, and the next four hours saw a dramatic legislative conflict.

The three voluntary health agencies, public health officers, public schools, and the independent universities had stunned the multi-billion-dollar tobacco and medical industries in a remarkable upset. Watching the defeat on television in Senator Diane Watson's office, the dozen or so Proposition 99 proponents could not believe their own success. Minutes after the defeat of the bill, the Democrats withdrew from the floor for a closed caucus. Watson returned to her office and warned the celebrating tobacco control advocates that they could not relax; they were about to witness the full fury of the medical providers, the tobacco industry, and local governments.[3]

Back in session, the Senate violated its own procedural rules, granting

In a remarkable political event, Governor Wilson left his office (which is also located in the Capitol building) and met with Senator Marion Bergeson (R-Newport Beach), a conscientious Mormon and the only Republican determined to resist the tobacco-medical coalition. This incident was the first and only time during his tenure that Governor Pete Wilson left his office to influence a vote on the floor of the Senate. Senate Republican minority leader Ken Maddy demanded that every member of the Republican caucus support AB 816 and refused to permit any Republican to exit the caucus without a commitment. The speaker of the Assembly, Willie Brown, appeared on the Senate floor with Phil Isenberg and pressured senators to vote for AB 816. Bill Lockyer, a Democrat, moved from desk to desk demanding Democratic votes for AB 816. For three hours, the contest continued as other business was carried out on the floor. Slowly, gradually, inevitably, the governor, legislative leadership, and county and medical lobbyists moved vote after vote. A core group including Senators Art Torres (D-Los Angeles), Diane Watson (D-Los Angeles), Tom Hayden (D-Santa Monica), and Nicholas Petris (D-Oakland) refused to compromise. With only one necessary vote remaining, Lockyer and Maddy threatened to fly in Senator Bill Craven (R-San Diego), who was seriously ill with lung disease, to conclude the contest, and a last holdout conceded, giving AB 816 the necessary four-fifths vote.

The Final Bill

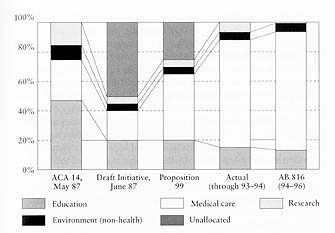

The governor signed the bill, which contained cuts in anti-tobacco health education and research that were approximately what he had originally proposed (figure 15). Over the two fiscal years 1994-1995 and 1995-1996, AB 816 appropriated only $94 million for anti-tobacco education (as opposed to the $157 million required by the initiative) and $8 million for research (as opposed to the $44 million required by the initiative, plus the $21 million left unexpended from the previous year).[56] AB 816 brought the total amount of diversions from the Health Education and Research Accounts to medical services to $301 million since Proposition

Figure 15. Proposition 99 funding allocations for AB 816. The legislation substantially accelerated the shift of money away from anti-tobacco education into medical services and now shifted funds from research too. It represented the most drastic diversion from the terms of Proposition 99 to date.

The outcome in 1994 thus continued the downward spiral for the Health Education and Research Accounts that began in 1989 with the first CHDP compromise. There was one important difference, however: in 1994 all three voluntary health agencies actively—if unsuccessfully—opposed any diversion from the Health Education and Research Accounts to fund medical services.

Assembly Member Terry Friedman (D-Santa Monica) abstained rather than voting against on AB 816.[43] A “no” vote would have deprived AB 816 of a four-fifths vote in the Assembly and stopped the diversions. In spite of all the work that the voluntary health agencies had done to pass his AB 13, which had barely made it through the Legislature in June 1994, Friedman did not support them on the AB 816 vote. Ironically, AB 13 was presented by some as an alternative to full funding of the Proposition 99 anti-tobacco education and research programs. For example, the Los Angeles Times editorialized in May 1994 that “the con

AB 816 contained three significant program changes. First, more controls were put on the schools. Schools would receive money based on Average Daily Attendance only for grades 4-8, while high schools would have to apply for competitive grants. In addition, evaluation of their programs would be conducted by evaluators in the DHS Tobacco Control Section (TCS), and the deadline for becoming tobacco free was moved from 1996 to 1995. Miller was less critical of Isenberg's stance on the schools than of his stance on the health departments and the Research Account. According to Miller, “The kinds of changes which had been proposed, indeed what Phil proposed for the schools, I think were long overdue and appropriate. I would still have an in-school program…[and] restrict it to those schools which express an interest.”[20] Second, public policy research was added as a priority area for the Research Account funding because it was “an area of compelling interest” to the Legislature. Third, the Tobacco Education Oversight Committee had oversight of the Research programs added to its mission and was renamed the Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee (TEROC). These changes were all consistent with positions the health groups had been advocating.

While the Health Education and Research Accounts took heavy hits from the Legislature, the governor's proposal to redirect some of the funds from the Public Resources Account was dropped, so this account again got more than its required minimum of 5 percent of the Proposition 99 dollars. According to Miller, the Legislature “gave about ten minutes to thinking about ripping off the mountain lion money and walked away from that” because “the environmentalists will kick their ass.”[9][20] The CMA's lobbyist, Elizabeth McNeil, had a similar response: “I think…fighting the environmentalists was a whole other realm, and a whole other fight, and I think that a lot of people made the assumption that that was a fight that was not even winnable. And that here was an arena where you had all health care organizations, who you could hope could help prioritize health care interests.”[7] There were important lessons here for the tobacco control advocates. The Public Resources Account was able to resist raids on its funds, and its advocates apparently had to do very little to protect it because everyone knew they were willing to “kick your ass.”

Conclusion

By 1994, there was no question that Proposition 99 had succeeded in achieving the goal its framers had in mind: to create a large anti-tobacco education and research program that would accelerate the decline in tobacco consumption in California. Through the end of fiscal year 1993-1994, the Proposition 99 programs (combined with the impact of the price increase that accompanied the tax) had roughly tripled the rate of decline in cigarette consumption in California and prevented about 1.6 billion packs of cigarettes from being smoked, worth about $2 billion in pre-tax sales to the tobacco industry.

Over this period of time, however, the Legislature and the governor had diverted a total of $301 million out of the anti-tobacco programs, about 34 percent of the total that the voters had set aside for these activities. Assuming a proportional drop in program effectiveness, these diversions probably resulted in an additional 530 million packs of cigarettes being consumed, worth about $800 million to the tobacco industry. Viewed from this perspective, the $23 million that the industry spent on campaign contributions and lobbying between 1988 and 1994 yielded a good return on investment.[56][58]

Until 1994, full funding of anti-tobacco education had been withheld with the consent of the agencies who were responsible for lobbying for the Health Education and Research programs—ALA, ACS, AHA. The passage of AB 816, however, was different; it passed despite the strenuous objections of the three organizations. While the confrontation over the diversions in AB 816 did not put an end to them, the dispute did achieve two other objectives. It began to engage the media and the public, and it set the stage for a legal test of the diversions.

Notes

1. Jacobs P. “Ex-allies feud over use of smoking tax” . Los Angeles Times 1994 June 27;A1.

2. State of California, Governor's Office. “Governor's budget summary, 1994-1995” . Sacramento, January 7, 1994.

3. Miller J. “Comments on manuscript” . January 31, 1999.

4. State of California, Legislative Analyst's Office. Analysis of the 1994-1995 budget bill. Sacramento, 1994.

5. Knepprath P, Najera T. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . August 16, 1996.

6. Isenberg P. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . April 9, 1997.

7. McNeil E. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . October 23, 1996.

8. State of California, Senate Rules Committee. Tobacco surtax programs. Sacramento, January 27, 1994.

9. Najera T, Miller J. “Interview with Michael Begay” . July 22, 1994.

10. California Wellness Foundation. The future of tobacco control: California Strategic Summit. Los Angeles, December 15-16, 1993.

11. Rutherford GW. “Letter to Edward L. Baker” . April 26, 1993.

12. Novotny T. Structural evaluation: California's Proposition 99-funded Tobacco Control Program. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 25, 1994.

13. Scott S. “Health Services holding up report on anti-smoking program” . California Journal Weekly 1994 February 14;5.

14. American Lung Association of California, Government Relations Office. “AB 816 (Isenberg)—Reauthorization of Proposition 99” . Action Alert, February 16, 1994.

15. American Lung Association of California, Government Relations Committee. “Minutes” . Sacramento, March 4, 1994.

16. Knepprath P. “Memo to Tony Najera, John Miller, and Betty Turner” . March 18, 1994.

17. Griffin M. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . July 22, 1996.

18. Castoreno C. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . July 11, 1996.

19. Hobart R. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . July 25, 1996.

20. Miller J. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . July 24, 1996.

21. American Lung Association of California, Government Relations Office. “Memo to interested parties re: Reauthorization of Proposition 99” . May 9, 1994.

22. Beerline D. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . September 26, 1996.

23. Martin C. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . September 4, 1996.

24. Pomer B. “Letter to Phil Isenberg” . June 21, 1994.

25. Pierce JP. “Letter to Gordon Cumming re: Evaluation of tobacco control” . May 16, 1994.

26. Jacobs P. “No-smoking debate flares over funding” . Los Angeles Times 1994 June 26;A1.

27. Glantz SA. “Changes in cigarette consumption, prices, and tobacco industry revenues associated with California's Proposition 99” . Tobacco Control 1993;2:311-314.

28. Californians for Smokers' Rights. “[Analysis] of Prop 99 Funds” . 1994(?)

29. California Medical Association. “Some tobacco tax local anti-tobacco “Health Education.”” 1994 May.

30. Sanders D. “Make smoke-free pork-free” . San Francisco Chronicle 1994 March 28.

31. Heiser PF, Begay ME. “The campaign to raise the tobacco tax in Massachusetts” . Am J Pub Health 1997;87(6):968-973.

32. Koh HK. “An analysis of the successful 1992 Massachusetts tobacco tax initiative” . Tobacco Control 1996;5(3):220-225.

33. Aguinaga S, Glantz S. Tobacco control in Arizona, 1973-1997. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1997 October. (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/az/)

34. Aguinaga S, Glantz SA. “The use of public records acts to interfere with tobacco control” . Tobacco Control 1995;1995(4):222-230.

35. Bialous SA, Glantz SA. “Arizona's tobacco control initiative illustrates the need for continuing oversight by tobacco control advocates” . Tobacco Control 1999;8:141-151.

36. Carol J. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . August 8 and September 5, 1996.

37. Hobart R. “Note to Edith Balbach” . August 4, 1997.

38. American Lung Association of California. “Statement on lawsuit re: Prop. 99 tobacco tax revenues” . Press release, April 8, 1994.

39. Martin CB. “Letter to Phil Isenberg” . June 28, 1994.

40. Ennix CL, Edmiston A. “Letter to Jack Peltason” . December 22, 1992.

41. Arditti S. “Letter to the Honorable Phillip Isenberg” . June 30, 1994.

42. Southwest Regional Laboratory. California programs to prevent and reduce drug, alcohol, and tobacco use among in-school youth. Los Alamitos, 1994 March.

43. Monardi FM, Balbach ED, Aquinaga S, Glantz SA. Shifting allegiances: Tobacco industry political expenditures in California January 1995-March 1996. San Francisco, Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1996 April. (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/sa/)

44. California Medical Association. “Report to the Board of Trustees from the Executive Committee” . May 13-14, 1994.

45. Foster D. “The Lame Duck State: Term limits and the hobbling of California state government” . Harper's 1994 February; 65-75.

46. Williams L. “Willie Brown and the tobacco lobby” . San Francisco Examiner 1995 September 17;B1.

47. Scott S. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . September 18, 1996.

48. Kennedy R. “Interview with Edith Balbach” . April 1, 1997.

49. Knepprath P. “Save Prop. 99 Coalition: Legislators to escalate attack on administration, opponents of anti-tobacco education and research programs” . Press release, June 1, 1994.

50. Knepprath P. “Prop. 99 Action Alert, June 6, 1994” .

51. Holsinger J. “Letter to the Honorable Bill Lockyer” . July 7, 1994.

52. Holsinger J. “Letter to the Honorable Willie Brown” . July 6, 1994.

53. Koerner S. “Legislature set to kill California's historic anti-tobacco campaign” . Press release, July 6, 1994.

54. American Lung Association. “AB 816 Conference Report—OPPOSE” . Floor Alert, July 7, 1994.

55. Thompson S, McNeil E. “Memo to honorable members of the California Legislature” . July 6, 1994.

56. Aguinaga S, MacDonald H, Traynor M, Begay ME, Glantz SA. Undermining popular government: Tobacco industry political expenditures in California 1993-1994. Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1995 May. (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/undermining/)

57. Los Angeles Times. “A rape in Sacramento” . Editorial. Los Angeles Times 1994 March 27.

58. Begay ME, Traynor MP, Glantz SA. The twilight of Proposition 99: Reauthorization of tobacco education programs and tobacco industry expenditures in 1993. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 1994 March.