Nacktballett

Nude performance in theatres for critical, paying audiences seeking entertainment and artistic excitement was an altogether rarer phenomenon than all the nude dancing pervading the realm of Nacktkultur . Theatre culture treated the idea of nude performance with great caution, and most of the attempts to introduce nudity in drama came from writers, whose thinking about what was possible on the stage was generally much more radical than that of actors and directors. After all, even the Nacktkultur societies sometimes had difficulty with the police when they wanted to present public slide-show lectures and films about their activities (OG 73–76). In the script for Arnolt Bronnen's Die Geburt der Jugend (1914), a large, antiphonal chorus of nude (but unnamed) male and female youths, some riding horses, trample down the older generation in the final scene and announce, in an orgiastic, expressionist hymn, the advent of a new, ecstatic community of naked bodies in the forest. All that differentiates the bodies from each other is their location in one of several choruses dancing and recombining across a vast space: "those in the forest," "those at the edge," and so forth. But when the play finally appeared on the stage in Berlin in 1925, nudity was conspicuously absent. With Die Exzesse (1923), a comedy and one of the most daring and innovative European plays of the twentieth century, Bronnen wrote three scenes involving nudity. Again, however, productions of the work, involving well-known Berlin actors, failed to put any naked bodies on stage. Among its numerous perversities, Hermann Essig's Ueberteufel (1918) featured a bizarre nude scene, but in Leopold Jessner's 1920 Berlin production the actress was not nude. In Die Schwester (1916), an even wilder drama of lesbian passions, Hans Kaltneker included a startling dance scene (with film) as well as a hymnic nude scene of lesbian prisoners receiving God's blessing. Curt Corrinth's Die Leichenschandung (1918) featured a dead prostitute walking nude, a Madonnalike

vision, among soldiers on the battlefield. But these two plays never had any performance.

All these nude scenes appeared in expressionist dramas, for by this time no one believed that realism had anything to do with nudity, and even films such as Opium (1919) and Von Morgen bis Mitternacht (1920) presented images of nude women as figments of a drug-induced dream or hallucination. As early as 1907, a Munich opera company planned to have Salome in Richard Strauss's opera perform the Dance of the Seven Veils completely naked, but the police intervened and forbade this choice. In 1924 the Vienna Volksoper dared to produce a pantomime, Adam und Eva, with nude performers, but the conductor, Felix Weingarten, refused to rehearse it and canceled the show. Nevertheless, in Hamburg in December 1922, Hugo Hillig (1877–?), a promoter of socialist hygiene policy and author of books on painting technology, staged his pageant Sonnenweihe for an audience of two hundred invited spectators, and several scenes contained completely unclothed men and women (OG 52). Adolf Koch staged a similar sort of pageant at the Volksbühne in Berlin in November 1929 (Merrill 187).

But, aside from these examples, nudity in the theatre was manifested through dance. From 1918 onward, impulses emanating from ballet culture moved toward an ever stronger identification of nudity with eroticism in dance. Berlin was the center for these developments, but the performance arena was largely the nightclub or music hall rather than the theatre or concert hall. Here nude dancing prospered in a strictly commercial environment in which artistic enterprises depended entirely on audiences rather than subsidies, enrollments, and memberships. As the war came to an end, James Klein (1886–ca.1940), manager of the Apollo Theatre, apparently introduced "nude ballets" within a revue format resembling the lavish glorification of the female body cultivated by the Ziegfeld Follies (Jansen 42–44). By 1921, when Klein moved his operations to the Komische Oper, these nude ballets had become main attractions and inspired vigorous competition from nude ballets elsewhere, especially those of Herman Haller (1871–1943) and Erik Charell (1895–1973). The scale of these productions escalated to the point that by 1924 Klein could offer a revue, A Thousand Naked Women, that offered twenty-two separate scenes, twelve songs, and as many as twenty-five women performing nude (topless, at least) in a single ballet (Jansen 45–50; Kothes 67–71).

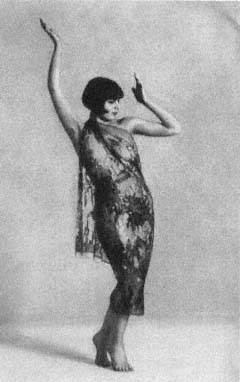

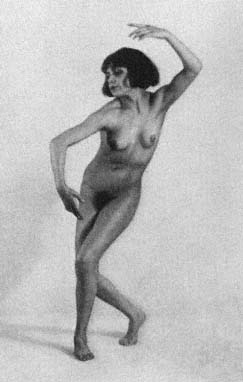

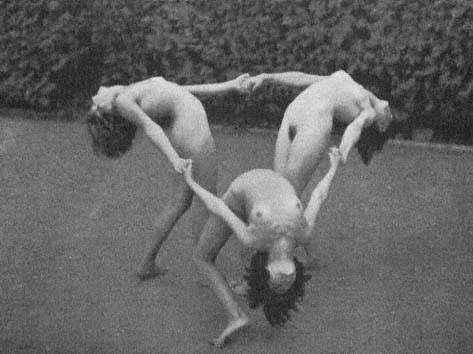

Celly De Rheydt

In 1919, with managerial help from her ex-army-officer husband, Celly de Rheydt (Cäcilie Schmidt) produced nightclub acts that featured a small ensemble of nude women ballet dancers. (She actually launched her career

by making a film of nude dances, which she apparently used as a promotional device.) De Rheydt's ballets exuded an aura of seriousness, even perversity, that was quite lacking in bigger productions, and because she avoided the revue format, her dances were more strictly balletic. She does not seem to have used more than five women in a single dance, which means she did not experience the pressure to build dances out of the mechanically synchronized, chorus-line movements used in revues. But her aesthetic created legal problems, and so she performed most of her ballets in private studios and clubs. Die Schönheit praised her 1920 performance in a large Berlin theatre: "It is the dancing of an idealist . . . in [whom] a strong artistic will dominates." Her program included a waltz in diaphanous veils, a "wild bacchanal" in purple light with bare breasts, a czardas in Hungarian tunics but bare legs, a pantomime called Opiumrausch with all dancers topless, and Die Nonne, in which de Rheydt and her ensemble removed nun's habits and danced completely naked in a gorgeous light. This last dance was especially annoying to the police. In 1921 the Munich Bund für Kunst, Wissenschaft und Natur used Celly de Rheydt and her dances as models for a series of idealized paintings of the body. By 1922, however, with numerous cabarets and clubs presenting lurid menus of nude dances, de Rheydt accepted an offer to perform at the Black Pussy (Schwarzer Käter) Cabaret, where her Salome Dance, Whip Dance, and Harem Ballet promptly inspired obscenity charges from the city prosecutor. Though the police had little success in forbidding her enterprise, it was clear that a nude erotic performance was somehow more daring if authored by a woman rather than a man.

In 1922 Otto Goldmann saw her perform in Leipzig. He felt her dancing was not as skillful as that of the teenage girls in her ensemble, nor was she as pretty as he expected. Yet he praised her acting ability, which excelled in a piece about vampirism. For this she wore a huge, fiery wig, and her face was deathly white, "full of merciless, enigmatic expressions." Her breasts were bare, but she wore blood-red gloves and tights, her hands like claws. In a green light, the vampire sought the blood of naked girls. "The creeping and gliding toward the victims, the leap at the throat of the victims on the ground—not a disgusting performance, as the material might indicate, but a highly theatrical performance in a modern style." However, he criticized the cabaret atmosphere in which de Reydt presented her dances, "with its alcohol flow and cigarette fumes, the stage so close to the first table that it could be the next table. And when a dancer steps onto a table of alcohol-befogged guests, the thought arises that she's eliciting something definite." "Whoever lets naked girls dance in public must make a sharp distinction between the here acceptable elf-like undulation and gliding and the typical cabaret dance with stamping and leg kicks. . . . Of the first sort too little is offered, and of the last, too much." Goldmann would much prefer to see

Celly de Reydt and her girls dance in "a sun-radiant forest meadow or by full moonlight . . . as forest witches, nymphs, and sylphides," for then he would not have to endure the vulgarities and prejudices of the cabaret audiences. But by 1924 de Rheydt's dances no longer seemed daring enough for the public, and she entered a new phase with a new marriage, this time to a theatrical producer.

Girlkultur

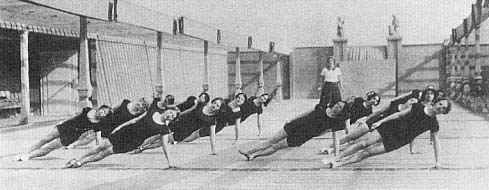

Some nude ballets, especially those in the semilegal clubs, reveled in pornographic sensations, whereas others, particularly Charell's, drifted toward an accommodation of the machinelike synchronization of moving bodies found in American-style pageants such as the Ziegfeld Follies (although the initial site of the nude ballet was prewar Paris, not New York). Figure 25 is a photograph taken in 1919 of a revue-type dance in a Berlin nightclub, well before the rise of enthusiasm for things American, which began after the inflation period and with the infusion of American investment capital. Swedish dancer Rigmor Rassmussen, whose nude image appeared in various arts magazines in the mid-1920s, was unique in migrating from modern dance to revue ballet, but the dances she performed interested the public much less than did the sleek image of dance she projected in photographs, and these eventually were successful enough to make her popular on Broadway. But the image of nude dance in a couple of modernist literary works from Berlin was perhaps more sensational than any visual art could verify. Curt Corrinth's Potsdamer Platz (1919), a wildly experimental novel, presented an apocalyptic nocturnal image of Berlin in which hundreds of thousands of people dancing nude and orgiastically signified a "borderless world of love." A decade later, a disillusioned Yvan Goll published Sodom Berlin (1929), in French, and this memoir sarcastically described the milieu of the expressionist nightclub culture in the early 1920s:

The word "freedom" is a stronger explosive than dynamite. The formula for "Universal Brotherhood" soon became dangerously expanded. Every compulsion should be abolished, and the intellectuals preached against every repression. The logical and natural consequence of a general orgy, with the gods as well-wishing witnesses. After midnight, everyone gathered in the temple of "Universal Brotherhood." The women undressed to destroy the seed of [commodified] voluptuousness, they pretended that ultimately the veiling of the body was responsible for the mysteries of sexual aberrations and that complete nudity would lead humanity to a condition of purity and nobility such as Adam and Eve had known. . . . Better than any sermon or profound theory, the dance proved that the human body had a soul (80–81).

In Sittengeschichte der Inflation (1931), Hans Ostwald reinforced this retrospective detachment by referring to a "dance frenzy" that swept

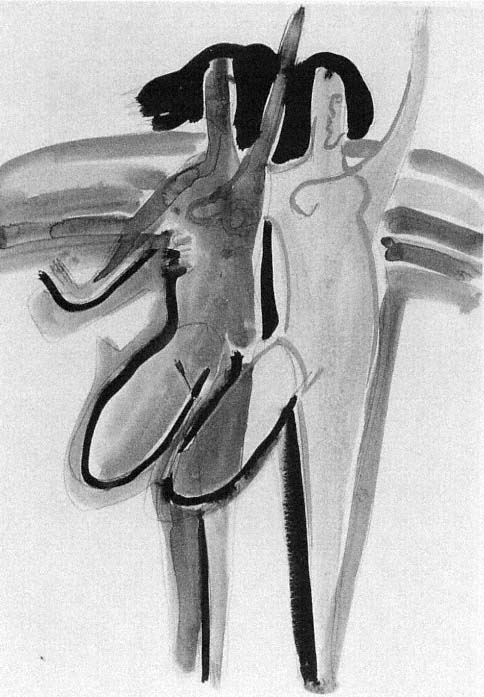

the nation in the early 1920s, led by young women hungry to know the limits of pleasure (134–150). In numerous illustrations by such artists as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Hugo Scheiber, George Grosz, Jeanne Mammen, Christian Schad, and Rudolf Schlichter, nude erotic dancing appeared as a lurid, inflammatory sign of social upheaval, with the unveiled, provocative body of woman as its vortex (Figure 24). This perception stood quite in contrast to the expressionistic, primeval-idol view of nude dancers found in the work of Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Otto Mueller.

Metropolis

Perhaps the most specacular Berlin effort to align nude dancing in the nightclubs with violent social upheaval appeared in Fritz Lang's monumental science fiction film, Metropolis (1927). One scene in this film overloaded with excesses featured the robot Maria (Brigitte Helm), nearly nude, performing a modern erotic dance atop a giant globe-turntable supported by naked musclemen. This voluptuous dance, performed in a luxurious club, precipitates a frenzied pandemonium in the audience of male spectators (investors in robot manufacturing), who all end up as a surging mob, with arms upreached toward the machine-idol perched elusively above them. This frenzy infects the slave workers inhabiting the subterranean depths of the city; they destroy the machines that have mechanized their lives, not realizing that the robot Maria who incites them is herself a machine, programmed by the mad scientist Rotwang to lead the masses to extinction.[1] In the dance scene, dance not only links social upheaval to the glorification of the erotic (feminine) body but also links erotic desire to the machinelike perfection of the human body: nude dance dissolves distinctions between human and machine, and out of this dissolution emerges an explosive mass of humanity, blind to its own destruction. In the nightclubs and cabarets of Berlin, interest in erotic nude ballets implied a capacity to see life and the feminine without illusions, without the desexualized naiveté with which the eurhythmics movement and modern dance tended to define the modern body. As Felix Salten remarked in 1924, "An era that has no illusions makes a public spectacle of the unveiled female body" (LF 25). But it was hardly surprising that many modern dancers, confronted with so many fantastic images of dance, felt that even mildly erotic themes merely contributed to the vulgarized image of dance purveyed by the entertainment industry, which, from a Marxist perspective, simply reduced the body to a fetish or commodity. This vulgarization was considered symptomatic of people's fundamental alienation from a higher value to existence than that supplied by primal drives.

[1] For further commentary on Metropolis, see Huyssen; Böhm; Combes; and Kaes.

Critique of Girlkultur

In Girlkultur (1925), Fritz Giese regarded the erotic element in dance as an ideological problem that German modern dance should transcend. The appearance after 1923 of American Girlkultur in Germany was for him an example of how capitalism produced decadent, vulgar attitudes toward dance and the body (Figure 25). According to Giese, the mechanized chorus-line dances of troupes such as The Tiller Girls (which was, in fact, an English enterprise operating in Germany) and the Amazonic Hoffmann Girls were grotesque efforts to emulate an absurd American obsession with measuring beauty. It was a delusion of men. To measure beauty by comparing and quantifying the bodies of women in a line in relation to a stable rhythm was to succumb to mass culture's unliberated perception of the body, the American notion of "collectivity," which treated all values quantitatively. Within the mass culture created by capitalism, dance always functioned to construct an image of the body freed from labor. The erotic interest of these mechanical dances therefore merely sustained the illusion of action that had no meaning or value as labor, work, or compulsion. For Giese, then, any modern dance must project a higher, transcendent attitude, detaching the moving body from the illusions of mass culture and from the mechanized obsession with measuring beauty cultivated by American capitalism.[2] As a labor psychologist, however, Giese displayed a vast preoccupation with measuring, as precisely as possible, almost every aspect of bodily performance that had no pleasure value. Seen in relation to his enormous "psychotechnical" works, his critique of Girlkultur indicates that the chorus line challenges rather than exemplifies efforts to measure pleasure. In his book Girlkultur he provided plenty of illustrative photos but none of the enormous array of labor-analyzing statistical devices, tables, and techniques used in Handbuch psychotechnischer Eignungsprüfungen (1925) and Methoden der Wirtschaftpsychologie (1925); he never discussed techniques for measuring pleasurable activities or aesthetic experience.

By contrast, physicist Rudolf Lämmel, in Der moderne Tanz (1928), contended that rhythm itself is precisely what allows us to perceive the body as a machine. Freedom, movement toward ecstasy, he suggested, is not a release from metronomic rhythm or ballet-type regulation of the body; on the contrary, freedom entails the capacity of the body to synchronize itself with mathematical laws governing the structure of music and movement (139–143). Lämmel sought to link new modes of dance to the dominance of science and technology in modern life. But what set him apart from so

[2] An argument similar to Giese's came from Siegfried Kracauer in a 1927 essay on "The Mass Ornament." More recently the argument has appeared in Klooss and Reuter, Körperbilder (1980).

many other dance thinkers of the era was his assertion that the chief attribute of dance movement was eroticism. Whenever the body called attention to itself through aesthetic movement, questions of sexual identity and erotic motive were not only inescapable but fundamental: scientific understanding of the body and movement as machine (dance) compels us to perceive modern being as an unveiled mode of erotic signification. Nevertheless, Lämmel was not enthusiastic about either Girlkultur or ballet, and he believed that Ausdruckstanz was the medium for the most serious and revelatory significantions of erotic feeling. Despite their contradictory attitudes toward the eroticizing of the body through dance, both Giese and Lämmel linked eroticism in dance to mechanization, measurement, and rhythmic regulation of the body.

But these attitudes contrast emphatically with those of Paul Leppin in his article on "Tanz und Erotik" for the first issue of the semi-Nacktkultur journal Das Leben (1917, 7–11). Leppin argued that eroticism manifests itself most powerfully in conjunction with the expression of intense religious feelings, for ecstasy is always a response to an immanence of the divine. Dance offered the strongest potential for signifying and experiencing ecstasy, but Judeo-Christian dogma had smothered dance in its determination to separate eroticism from great religious feeling. As a result, European dance culture could present nothing more than the feeble, "sweet and decayed" eroticism of the waltz. "That we have nothing from the lives of the great modern erotomanes indicating a preference for dance has its basis in the violent and brutal drives of the masses, who always seek to resolve their differences through a normative form, while individuality means losing oneself in the formless and the immense without even remembering one's limits. . . . The time must come which shakes us, which revitalizes the dormant evil and splendor within us, tremendous powers, doubts, which rumble in our hearts like the thunderstorms of romanticism, oaths, hate, anticipations." Leppin did not explain what sort of dance would accommodate this rhetoric, but the accompanying illustrations of Salome dancers and a female sword dancer, along with such phrases as "a glowing fanaticism of the flesh," "extravagant power which resounds in our blood," and "overflowing pleasure," implied that serious erotic dance entailed both nudity and rhythmic motions simulating orgasm and sexual intercourse. It was these movements more than any other, we are to understand, that undermined the mechanization of identity imposed on the body by Judeo-Christian dogma and its ambassador, the French-Italian ballet tradition. Leppin did not acknowledge any of the multitude of Salome dances that had already saturated European theatres by this time, so presumably all of these fell short of the cultural upheaval he ascribed to religiously grounded erotic dance. Although the accompanying pictures showed only female dancers, Leppin made admiring reference to the orgiastic dancing that followed the ser-

mons of the sixteenth-century Anabaptist heretic John of Leiden, whose congregation glorified the nudity of the community and the repeal of clerical constraints on erotic feeling. But one could hardly say that Leppin was a prophet of Girlkultur, which in its balletlike regimentation of the body—all kicks, stamps, salutes, twirls, and bobs—would never permit anything so "formless" as the simulation of orgasmic movement.

By 1930 nudity in theatrical dance ceased to enjoy the strong presence it had achieved by the mid-1920s, even though Nacktkultur in general continued to grow in popularity. The heyday of the nude commercial ballet in Berlin was between 1923 and 1926. By 1927, however, Berlin audiences seemed to have grown weary of the lack of innovation or daring in nude performance; forces of censorship, managing at last to mount successful legislation (or appoint more aggressive prosecutors) against its targets, established a threshold of daringness in performance, which theatre producers felt little inclination to test. A problem with linking nudity to eroticism is that interest in nudity wanes if its erotic aspect does not escalate or intensify from performance to performance. Producers sought to accommodate this process of escalation by introducing larger, more elaborate production numbers. But with nude erotic performance, as Celly de Rheydt apparently understood when she quit the game in 1924, the escalation of erotic significance does not depend so much on production values as on the introduction of newer and stranger erotic actions. These, in turn, create more highly specialized audiences. The period 1925–1932 was supposedly the golden age of semiclandestine cult clubs catering to very specialized sexual tastes—homosexuals, lesbians, transvestites, bisexuals, sadomasochists, fetishists of all sorts, pedophiles, female mud wrestlers, and other gross or grotesque entertainments described, rather politely, by Curt Moreck in his underground guidebook, Führer durch das lasterhafte Berlin (1931). In Piel Jutzi's film Mutter Krausens Fährt ins Glück (1929), a young worker takes his new girlfriend to a club for a wrestling match between a runty little man and a ferocious fat lady, who throws him all over the stage; this spectacle so offends the worker that he insists his date leave with him, although she seems to find the entertainment amusing. In a 1923 issue of Die Nachtpost (1/24, 2), a squalid Hamburg tabloid sanctimoniously dedicated to the eradication of smut and prostitution, Hermann Abel complained loudly about a Hamburg theatre in which a master of ceremonies invited male patrons to suggest lewd poses and dances to several nude women and to masturbate while watching them for twenty minutes. Lavish revue-type productions were simply too tame to sustain the interest of audiences for such clubs. Yet the audiences were never large enough to justify high production values or investment in superior talent. Indeed, in such clubs it was more likely the patrons who danced with each other (social dancing), and serious nudity was not a significant feature of their erotic performances. As a result,

cult clubs often exuded an atmosphere of sleaze, as represented, for example, in Josef von Sternberg's famous film, The Blue Angel (1930). However, the permissive activities of the sex clubs were not entirely a product of the purported Weimar decadence following the war nor of the inflation period, as Ostwald made clear in his five-volume anatomy of this pre-Weimar subculture, Das Berliner Dirnentum (1905).

In her admittedly unreliable diary, Mata Hari included an entry from about 1906 describing her visit to a bisexual club in the vicinity of Potsdamer Platz in Berlin; there she saw male and female transvestites, dancing pairs of male and female homosexuals, men and women who allowed persons of either sex to fondle and disrobe them, and a beautiful male dancer in female costume who concluded his voluptuous performance by lifting his dress to reveal his erection, a gesture Mata Hari found intensely arousing (217–221). Nor did these sorts of displays disappear entirely with the advent of the Third Reich. The Kattenberg Archive in the Harvard Theatre Collection contains the correspondence of a Chilean corporate executive, Eduardo Titus, whose great obsession was contortionist acts. On 12 December 1939, Titus wrote to a fellow contortion fan, Burns Kattenberg, of his visit to Berlin cabarets, where he saw female contortionists perform for groups of women who seemed more nude than the performers.

I often found in Berlin a table in a cabaret with four or five women around completely naked under their gowns, smoking and drinking and giving little attention to the men. They were heavy in their applaud [sic], making a lot of noise when a woman was contorting. When I saw senorita Carmara at the Zoo cabaret, three women that were seated at a first row table got so excited when Miss Carmara got her head through the thighs in a headstand, and placed the back of her head against her cache-sexe, that one of them jumped over the platform and started to kiss and caress the body of the acrobat and had to be taken away by the waiters.

Nevertheless, few can doubt that the Weimar era, especially during the inflation period, provided unprecedented and perhaps unsurpassed opportunities for underground and perverse erotic entertainments. The Swedish poet Bertil Malmberg, who was close to the aristocratic dance circle cultivated by Beatrice Mariagraete in Munich during the war, wrote in 1953 that Germany in 1919 seemed overwhelmed by a vast "social orgasm," of which the woman-driven craving for dance was the most obvious sign and from which Munich was no more immune than Berlin. "Munich in the 1920s signified a public procession of licentiousness [in the dance cafes]. . . . Indeed, there reigned a kind of mass sexuality, which was actually narcissism, fantastic excesses, camoflouged behind a curtain of ambiguities and obscurities . . . a taste for infantile polymorphous perversity." Adolf Hallman, another Swede in Malmberg's circle, described "the other Munich" of the

dance halls attended by a "degenerate public," where "on the dance floor sleek youths in pageboy haircuts and undershirts and girls with boyish heads, clad in smoking jackets, danced with each other in a convulsive mass, then suddenly stood still . . . their eyes blank with cocaine, their nostrils trembling . . . and everything [occurring] in a lurid decor of German expressionism, choked with cubism." Malmberg believed that the "pornographic scenes" available in Bavarian dance clubs disclosed a new form of "revolution" dominated by "strong narcissistic-erotic impulses" (Bergman 200–203).

Anita Berber

In spite of its persistent hesitation to deliver any serious statement about nudity and modernity, the Berlin nightclub culture of the early 1920s produced, in the work of a bizarre exponent of expressionism, Anita Berber (1899–1928), what was perhaps the most complex, significant, and memorable relation between nudity and dance to emerge between 1910 and 1935. Because of the sordidness of Berber's life, few dance scholars take seriously her contributions to German modern dance. Yet the perversity of her approach to dance is worth extended attention here precisely because she took risks; she staged more overtly than any other Weimar dance figure the dark (erotic) complexity governing perceptions of relations between modernity and nakedness. No one of the era has been more closely associated with nude dancing than Anita Berber. She made numerous nude photos of herself in poses from her dances, although it is not at all clear where or when she actually danced naked in public. In a comment for Das Stachelschwein (2, 2 February 1925, 46), a writer with the initials "K.S." claimed to have worked with Berber for more than a year and asserted that "she has never danced naked." But this pronouncement is probably as exaggerated as many of the scurrilous fantasies about her. Berber deepened the notion of nakedness in dance by making her dances so intensely autobiographical—and the life she made naked in her dances was very messy.

Berber came from a bourgeois family that was a textbook example of dysfunctionality. She studied under Jaques-Dalcroze at Hellerau (1913) and ballet in Berlin under Rita Sacchetto from 1914 to 1916, but she had no affiliation with the Nacktkultur societies. A brief dance scene in a film she made in 1919, Unheimliche Geschichten, shows a body well trained in ballet technique, able to move from decorative, on pointe delicacy to explosive lunges, but Berber's use of ballet technique was always subordinate to an expressionistic aesthetic that relied more on theatrical effects than on a refined sense of movement. Berber pursued an eclectic career as a concert and cabaret dancer, high fashion model, fine artist's model, and film actress, appearing in twenty-five films between 1918 and 1925. By 1917 she

was a star fashion model for the mass circulation women's magazine Die Dame, and in 1919 she posed for a number of pornographic drawings by Charlotte Berend, some of which appear in Fischer (53–59). She made her debut as a solo dancer in Berlin in 1917, introducing her Korean dance wearing an exotic, silken pajama-type costume with a fantastic headdress. According to Elegante Welt (6/3, 31 January 1917, 15), she was already a mature artist, full of "daring" presence, "remote from all sweetness," and "always a little boyish." Berber experienced powerful bisexual passions that urged her into a promiscuous, perverse lifestyle and compelled her to push dance into dark, violent regions of feeling. As her dances became more lurid and apparently enticing, she displayed an increasingly haughty, disdainful attitude toward her audiences, who tended to show little appreciation of her as an artist, regarding her as a totem of the freakish era in which they lived. As the gifted modernist Czech choreographer Joe Jencik (1893–1945) accurately explained, "Both men and women feared her creations, which showed the trash and extinction of bourgeois bedrooms and barbarous marriages. . . . The public never appreciated Anita's artistic expression, only her public transgressions in which she trespassed the untouchable line between the stage and the audience. . . . She sacrificed her person to a self-vivisection of her life" through dance (JJ 8–9).

As a dancer, she achieved notoriety through her use of flamboyant costumes and her skill at representing a variety of attitudes toward romantic music. In 1919 she introduced Berlin to her ambitious Heliogabal, a complicated piece of bisexual eroticism inspired by a passage from a Dutch novel by Louis Couperus, De Berg van Licht (1905). She performed the role of the perverse Roman emperor Heliogabulas, the high priest of a Syrian sun-worshipping religion. "Exquisite, entirely attired in gold, her metallic body lured the sun, while two Moorish boys effectively manipulated the decor.—Another image. A mask interlude during the Saturnalia, with music by Delibes. A silver mask, including a stylish headdress, was pulled back just a little to reveal the mysterious face under it. Roses, red silks and scarves, pants a la Chanteclair. It is plainly a mask ritual. Serious, very worldly, seductive, imperial, full of daring contrasts is this dance" (Elegante Welt, 8/2, 1919, 5).

It is not known when Berber first performed nude dances, but presumably it was around the same time (1919–1920) she became interested in nude photography. Yet most of her dances involved bizarre expressionistic costumes and scenographic devices. In Astarte she was the cold moon goddess who rejects the lascivious advances of the men and women who lust after her. With Salome she explored an unusual perspective: "from below." "From a place where the legs are distorted and look like mammoth columns marbleized with veins, where the thighs look like ecstatic girders carrying the terrible sex on a shameless balcony; over it the canopy of a swelling

stomach—this was Anita's perspective. Everything else is insignificant, the head is small, like an unripe plum. . . . This perspective allowed [Berber] to see somebody in love boundlessly obsessed by sex, without a head and breasts . . . love concentrated only in the lower part" (JJ 25–26). Attired in a purple cloak, she began this dance rising, undulating, out of a huge urn filled with blood. But then she froze and, with closed eyes, inhaled the blood, dipped her hands in it, while her face produced an expression that "could have been lust or torment." When she stood up, her arms crossed, blood dripped from between her legs as if she were menstruating. She discarded the robe and was naked, panting orgasmically; she masturbated with bloody hands, yet she "did not cease to be royal." Then she started to move to the music of Richard Strauss. Berber pivoted elegantly, executed ballones, arched back, then shot up straight with each violent chord. Her blood-stained hands floated in the air as she performed port de bras, "like in a beautiful exercise." She also introduced caprioles, spinning tours en l' air, and graceful tombes (falling to the knees), in what must have been one of the most astonishing travesties of ballet technique ever imagined. Finally she crawled about the urn, making undulating movements with her belly, then spiraled up triumphantly before kissing the blood and sinking back into the urn.

In Debussy's first Arabesque, a more abstract mood prevailed, as Berber adjusted her body to the "maze of rhythms" in the music. Her arms and hands developed a rhythm that contradicted the rhythm of her legs and feet, while her head followed yet another rhythm. She found a way to physicalize every notation in the score, incorporating abrupt jerking movements with gossamer rippling motions to produce, in spite of its technical density, a dance as luminous as the music. In Morphine, however, she was back in a gloomy narrative mode, and her vocabulary of movement was much more economical. Clad in a black dress, she sat in a huge armchair and injected herself with a syringe. She sat deathly still for a moment; then, according to Jencik, "she thrust her body in an incredible arch, like a morbid rainbow." Her movements appeared broken, incomplete, as the drug-induced visions arose before her; finally the drug "stabbed" her, and she contorted into the beautiful arch again and died in the chair.

One of her most unusual pieces was a "love dance" in a sadomasochistic vein, set to a waltz by Brahms. Here she had a male partner. They entered the stage dragging each other, she all in white, he in black. As the gentle waltz flowed on, the pair engaged in a violent struggle in which passionate embraces were asphyxiating and kisses—to the neck, the chest, and the thighs—appeared predatory, cannibalistic. Exhausted, the lovers sank into a stupor, but the pretty music streamed on, oblivious to the violence it motivated. Then the music revived the energies of the dancers, and they renewed the attack with even greater ferocity; their arms, legs, and torsos

became intertwined, and they exerted "the force of a lion and lioness," without rationality or even feeling, "only the senses remain[ing]." The man now dominated the dance, while the woman "groan[ed] with her knees and incredibly bent spine." A sort of rape occurred, but the music just floated on serenely. The dance ended before the music did: on their knees, the dancers let their arms hang limply as they bent their heads backward, as if to ask a question of the sky but unable to formulate it. Then they stood facing each other without even touching. Here, as in Salome, the dance made sophisticated use of ballet technique: the male executed chasses, glissades, low jetés, and degages, while Berber performed chasse glisses, ballones, arabesques, attitudes, fouettés, and port de bras to create a "true poetry of power" that did not rely on mimicry. Jencik noted the significance of the dancers' bodies: "one had female beauty in a male body, the other male grace in a female body." Another strange partner dance was Shipwrecked, in which Berber used a gramophone on stage to play ragtimes, fox trots, and Charlestons. But the marooned and naked husband and wife did not dance with each other; instead they wallowed in narcissistic, masturbatory movements, as if the other was only an untouchable mirror of the self. As the ragtime kept playing, the dancers kept "moving in the belief that the dance would kill them." On the whole, though, Jencik did not think Berber was as strong in partner dances as in solo dance. Works such as Lotusland, devised by Sebastian Droste (Willi Knobloch), struck him as hopeless kitsch glorifying the decorative, passive, masochistically submissive woman of prewar Orientalist fantasy.

In 1918, after touring Germany, Vienna, and Budapest, Berber became involved in a homosexual scandal at the Hotel Bristol in Vienna. She returned to Berlin, married immediately, and began making movies until 1922, when she fell in love with a woman and divorced her husband. But the affair did not work out; the same year, she met and then married Droste, a somewhat unsavory opportunist who became her partner as a dancer and transformed every "real feeling" of Berber's into a "sensation" (Lania 153–154). As Willi Knobloch, he published some interesting experimental poems and a quite bizarre little "visionary" drama of family salvation in the Dresden expressionist journal Menschen (2/7, 1919, 14–24), but otherwise he spent his life in shady enterprises and sleazy homosexual subcultures. He and Berber went to Vienna in 1922, where he soon was accused and then imprisoned for fraud. Berber paid his debts, and he went to Budapest; then Berber was arrested for trying to steal the objects she had put up as collateral to pay the debts. The police told her to stay out of Austria for five years. In 1923 the marriage broke up, and Droste fled (with Berber's jewels) to New York to start a new career as a representative of avant-garde counterculture, appearing, for example, in a startling experimental film by Bruguiere in 1925 (Enyeart 29–48). Droste apparently succeeded in inter-

esting D. W. Griffith in a movie script he had written about his life, but ill health compelled him to return home to Hamburg, where he died in 1926.

Meanwhile, Berber continued with another male partner she met in Munich, the American Henri Chatin-Hoffmann, whom she married within fourteen days of making his acquaintance. The couple traveled throughout Europe, creating scandals almost everywhere because of her perversity on stage and off—sometimes she would go out into the streets wearing only her fur coat; she conducted orgies in her hotel rooms; she danced lasciviously with other women. The couple visited Breslau, Cologne, Leipzig, Hamburg, Dresden, and Prague, but in Zagreb she went too far during a performance by insulting the King. For this she went to jail. Henri finally managed to obtain her release, and in 1927 the couple embarked on a tragic tour of seedy nightclubs in the Middle East: Athens, Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus, Alexandria, Beirut. Soaked with drugs, Berber became progressively ill and barely made it to her deathbed in a Berlin hospital, where she died of the same disease, tuberculosis, that had claimed Droste. As Jencik put it, her dances carried with them the "scent of bedrooms, hospitals, asylums, and morgues." The central focus of her artistic existence was "not the studio, but the boudoir," which she treated as a luxurious laboratory-temple for the exploration of sensual pleasures of all sorts. She surrounded herself with a huge collection of idols and religious images, and she collected sexual partners as if they, too, were part of her icon collection.[3]

Dances of Vice, Horror, and Ecstasy

In 1922, Berber and Droste published (in Vienna) a strange book of poems, photographs, drawings, and semitheoretical statements (by Leopold Wolfgang Rochowanski [1885–1961], a Viennese cultural historian, expressionist poet, and promoter of radical expressionist art and dance) related to the

[3] Henri tried to establish himself as a dancer in New York in 1929–1930 but was not successful because, apparently, he was "so persistent in strangling his own potentialities for the sake of an ideal only visible to himself and a little group of similarly attuned spirits" (The Dance, 14/1, August 1930, 60). By far the most complete account of Berber's life and art is Jencik, Anita Berberova (1930). Fischer's Anita Berber (1984) does not examine her dancing with any specificity, nor does Leo Lania, Der Tanz ins Dunkel: Anita Berber (1929), both of which concentrate on the sensational aspects of her messy life. That is also the case with Rosa von Praunheim's sleazy 1987 film Anita Berber—Tänze des Lasters und des Grauens, a campy story about an old woman who imagines that she is Anita Berber. In Amsterdam in March 1990, Ute Dörner choreographed and danced in a piece called Tanz ins Dunkel about Berber's life with Droste. An even more outrageous desecration of Berber occurred in San Francisco in March 1994, when Mel Gordon, in collaboration with the Goethe Institute and punk rock singer Nina Hagen, staged The Seven Dances of Lust, a garish, absurdly "decadent" bio-drama at Bimbo's 365 nightclub.

Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase, which they had performed in Berlin (Figure 26). Fischer claims the couple made a film of the same title in Vienna in 1923, but if so it has disappeared. The relation between the poems and particular dances is not clear from either the book or descriptions of the performances. Berber and Droste staged dances bearing the titles of the poems; it is not known if anyone spoke the poems before or during the performances, but the structure of the dances apparently corresponded to the "voice" of the poems. Berber's writing style differed from Droste's in that she linked words together to represent, rather conventionally, the rhythms of sensory perception that form a complex image in the mind, as these lines from "Orchids" indicate:

For me they [orchids] are like women and boys—

I kissed and tasted each until the end

All all died on my red lips

Droste, by contrast, isolated words and phrases so that they called attention to themselves as discrete energies that did not depend on an action (a verb) to establish intense emotional relations to each other, as appears evident in "Kokain" (Berber was a cocaine addict):

Walls

Table

Shadows and cats

Green eyes

Many eyes

Millionfold eyes

The woman

Nervous scattered cravings

Inflamed life

Swollen lamps

Dancing shadow

Little shadow

Great shadow

THE SHADOW

Oh—the leap over the shadow

It tortures [me] this shadow

It martyrs [me] this shadow

It devours me this shadow

What desires this shadow

Cocain

Outcry

Animals

Blood

Alcohol

Pains

Many pains

And the eyes

The animals

The mice

The light

These shadows

These terrible great black shadows

According to Jencik ("Kokain"), Berber interpreted this poem as a dance with the aid of some unidentified piano music by Saint-Säens and ominous scenery by Harry Täuber featuring a tall lamp on a low, cloth-covered table. This lamp was an expressionist sculpture with an ambiguous form that one could read as a sign of the phallus, an abstraction of the female dancer's body, or a monumental image of a syringe, for a long, shiny needle protruded from the top of it. Light emanated from a beacon in the middle of the sculpture and allowed the dancer to cast a powerful shadow, requiring her to perform movements that made the motion of the shadow as interesting as the motion of her body. It is not clear how nude Berber was when she performed the dance. Jencik, writing in 1929, flatly stated that she was nude, but the famous Viennese photographer Madame D'Ora (Dora Kalmus) took a picture entitled "Kokain" (included in the book) in which Berber appears in a long black dress that exposes her breasts and whose lacing, up the front, reveals her flesh to below her navel. Because Berber performed other dances in the nude, and because nudity in dance is a persistent theme of the book, it is possible that Berber sometimes performed Kokain completely nude and sometimes performed it wearing her costume, depending perhaps on the moral climate wherein the performance occurred.

In any case, according to Jencik, she displayed "a simple technique of natural steps and unforced poses." But though the technique was simple, the dance itself, one of Berber's most successful creations, was apparently quite complex. Rising from an initial condition of paralysis on the floor (or possibly from the table, as indicated by Täuber's scenographic notes), she adopted a primal movement involving a slow, sculptured turning of her body, a kind of slow-motion effect. The turning represented the unraveling of a "knot of flesh." But as the body uncoiled, it convulsed into "separate parts," producing a variety of rhythms within itself. Berber used all parts of her body to construct a "tragic" conflict between the healthy body and the poisoned body: she made distinct rhythms out of the movement of her muscles; she used "unexpected counter-movements" of her head to create an anguished sense of balance; her "porcelain-colored arms" made hypnotic, pendulumlike movements, like a marionette's; within the primal turning of her body, there appeared contradictory turns of her wrists, torso, ankles; the rhythm of her breathing fluctuated with dramatic effect; her intense dark

eyes followed yet another, slower rhythm; and she introduced the "most refined nuances of agility" in making spasms of sensation ripple through her fingers, nostrils, and lips. Yet, despite all this complexity, she was not afraid of seeming "ridiculous" or "painfully swollen." The dance concluded when the convulsed dancer attempted to cry out (with the "blood-red opening of the mouth") and could not. The dancer then hurled herself to the floor and assumed a pose of motionless, drugged sleep. Berber's dance dramatized the intense ambiguity involved in linking the ecstatic liberation of the body to nudity and rhythmic consciousness. The dance tied ecstatic experience to an encounter with vice (addiction) and horror (acute awareness of death).

Movement toward ecstasy (and utopia) entails the convulsion or fragmentation of the body and (as the form of the poem implies) language. The ecstatic body vibrates with multiple rhythms. But an acute sense of rhythm is simultaneously an acute sense of time arising out of an acute intimation of death, of finality, of stillness and silence. The dancer's ecstatic rhythm is in fact a struggle to transcend rhythm itself: ecstasy is an anesthetic state, a condition of being drugged, free of bonding emotions. Rhythm signifies not liberation but repetition, addiction, craving for balance in a world of shadows; it is the mechanization of time and feeling, that which makes of the body a marionette. Thus, mechanization does not exist in tension with ecstatic experience; it is the drive toward ecstasy. It is the aesthetic correlate of addiction, of dependency on surrogate sources of pleasure (drugs, music). And, just as ecstasy is within vice and horror, so the healthy body is within the poisoned body. The nude body is the site of contradictory rhythms, of conflict between drugged and erotic drives toward ecstasy. But the healthy body can triumph over the poisoned one only through the voice, speech, language, the cry—which, however, the dancer cannot produce.

Droste's words, the language of the other, the male partner, inspire complex movements but remain unspoken. Missing are the actions (verbs) that define the relation between the identities listed. Dance does not translate the words into movements; rather, it supplies the movements the language motivates. Nudity here signifies a state of heightened aloneness before the shadow-other, before an anonymous audience, before "millionfold eyes," before the "devouring" image of death. The death-suffused words of the (male) other motivate nude dance, which in turn exposes the relation between the body, modernity, and ecstasy. Cocaine is not a source of ecstasy but a sign of modernity; ecstasy entails a performance of the nude body before an anonymous audience, without fear of appearing ridiculous, of disclosing masochistic dependencies on drugs, mechanized rhythms, or men, of the "horror" of narcissism provoked by being the only one naked. Such performance of nudity is in effect a mode of ecstatic confession, an intense

pleasure in showing people how utterly alone and different one is in a modern world of addictions and mechanized rhythms.

Giese, Hagemann, and Menzler implied that the most powerful sign of a unique personality is nude dance. Berber's dance did not contradict this implication, but it was "more naked" than nude dance elsewhere in constructing a perception of uniqueness as a condition of stark aloneness, estrangement, and perversity. Nude dance was no cure for cocaine; it was not modern because it had any therapeutic effect. For Berber, nude dance aestheticized her sickness, and by doing so, by aestheticizing the addictions, compulsions, and mechanized rhythms defining the modern body, her dance anticipated postmodern sensibility; it was an almost satiric critique of the pretentions to a healthy, modern identity that both eurhythmic consciousness and Nacktkultur sought to achieve. Pleasure for the modern audience (not just the dancer) depended on aestheticizing, through nude dance, the symptoms of an incurable aloneness that makes the body modern.

However, the meaning of Kokain should not be detached from the context of its presentation (as a "dance" of vice, horror, and ecstasy) in the strange book Berber and Droste published. It is difficult to imagine, let alone find, a more bizarre and complex relation between dance, writing, speech, nudity, and image than that found in this little book. Berber wrote only four of the twenty-six poems in Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase, and none of these inspired a dance. Droste wrote all sixteen of the poems the couple danced. He was the solo dancer for four of the poems, and Berber was the solo dancer for another four. The couple danced as a pair for seven of the poems, and one poem, which apparently never reached live performance, required three distinct "persons"—a "murdered woman," a "murdered boy," and a "hanged man"—as well as an "accusatory mob" and a "hundred thousand corpses."

Some poems are quite tiny; others run on for three or four pages. The mood of all the poems is consistently morbid and decadent, with pervasive references to death, phantasmal figures, tortured flesh, narcissistic sensuality, and narcotic visions. Droste juxtaposes allusions to artworks and artists with images of archaic cultures: Byzantium, ancient Egypt, imperial Rome, the sinister world of the Borgias. He also decorates his poems with mention of exotic sensations and materials: gold, diamonds, pearls, amethyst, silver light, perfumes, wax, powdered skin, distant organ tones, glass objects, silken pajamas, lurid lampglow, blue mist: "Woman/Red-haired/Gold net/pearls on the forehead." But the most disturbing references are to bodies (living and dead), parts of bodies, and body metaphors: "fingers like blood," "powdered thighs," "gold on the naked body," "green eyes," "screaming green," "boyish arms," "white head," "flaming hair," "ecstatic hands," "painted like a whore," "glassbright cry," "sibling corpses,"

"yellow-green desires," "the trembling steps of woman," "Oh she is an orchid/And seven heads." All these rhetorical devices construct an image of the dancer, male or female, in which the glamor of the body arises out of its morbidity. It is a variant of Wigman's perception of dance as ecstatic movement toward death.

But in Wigman's case, a different relation between writing and movement prevailed. With Wigman, writing preceded dance in the form of dense notebook collages of words and drawings whose meaning was often indecipherable. For her, dance was a phenomenon that freed the body from inscription, from containment within a text (or supertext). Berber and Droste apparently treated this belief in moving from writing to dance as incomplete, even naive. Though each individual poem may have motivated the dance that bears its title, the calculated aesthetic effect of the book (which extends to the typography and luxurious paper) suggests a more complete movement, from writing to dance back to writing. For these authors, dance performance continued beyond the moment the body made movement synonymous with life. The lurid, seductive book included some documentation of dance performance (as if to convey that documentation allows performance to live on after it is over); more important, it presented itself as a collection of dances, constructing the perception that dance is complete only when dancers become authors and transform their dances into poetic inscriptions. Whereas Wigman saw dance as life that emerges out of writing, Berber and Droste understood dance as an art that emerges out of writing and completes itself through publication in the form of a book. The writing was only one element of a performance that included an assortment of images and codes. For Berber and Droste, the body had to free itself, not from words or images, but from the all-too-brief moment in which it lived through performance. However, the dominant sign of this freedom was not words nor writing as such but rather the perverse book, which attempted to blur distinctions between writing and movement by obscuring relations between poems and dances. One might say, then, that insofar as the book represented a further state of nakedness for the dancer, the desire for nakedness entailed a desire to construct a highly ambiguous rather than ultimate perception of identity.

Consequently, it is almost impossible to determine the extent to which the dances translated into movements the words, syntax, or rhetorical devices of the poems. Theoretical statements by Droste and Rochowanski provide some clarification. These also appear as poems. In "The Dance as Form and Experience," Droste, asserting that "form is the expression of an inner experience" that ballet is incapable of embodying, concluded that the dances he and Berber performed constituted an "unconscious, sacred movement to the sounds/of an alien world" (16). Perhaps, then, the poems

were supposed to project the emotional effect of this alien sound world rather than to encode specific correlations between bodily movements and particular words, syntactic structures, or rhetorical devices. Even so, it is probably impossible to detach the morbid and ecstatic effect of the poems from their referents or semantic values. Indeed, the whole book constituted a fantastic network of referentiality. Poems referred to dances, and dances referred to poems. Both poems and dances referred to both art and the lives of the dancers/authors. In the theoretical (that is, undanced or undanceable) poems, Berber and Droste referred to each other with narcissistic intensity. But all these layers of referentiality became so convoluted that referentiality itself became a sign of morbid doubt over the authenticity of what was written or written about. The incessant, gaudy references to nudity, the body, and the decoration or masking of the body disclosed an inclination to believe that neither nudity nor the body were signs of authentic being; they were signs of fantasy, hallucination, upon which the intersection of horror, vice, and ecstasy were predicated.

Droste developed this perception most overtly in one of his theoretical poems, "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte" (The Vicious and the Naked), which is actually a violent kind of allegory. In his apartment, a man powders, perfumes, and ornaments his nude body. Having completed this ritual, he dons a cape and visits a bar in a Roman piazza frequented by homosexual boys and prostitutes. He has a drink, leaves without paying, and goes to another lonely piazza, where he removes the cape and stands naked, "smiling at his slender powdered thighs" and apparently masturbating. "A cry went through the streets/Out of the alleys streamed" singing fascists, "slender boy bodies," and frenzied women, all of whom sink to their knees before him, as if he is an idol. "Only the vicious one stood smiling in the crowd." This figure wears a dark coat and dark glasses, but he also powders his face and paints his lips. He approaches the naked one and kisses his navel, frightening away the crowd. The vicious one proceeds to strangle the naked one "with scientific precision," then decapitates him.

Then he took the painted head of the naked one back home

Placed it in a glass baroque vitrine

And sank trembling to his knees

None of these extreme actions involves any speaking (except for the anonymous cry provoked at the moment of the man's disrobing). This poetic language produces a scenario for bodily movements that possess the voiceless authority of a perverse, violent dance. The poem presents nudity as a silent yet public performance that awakens unspeakably turbulent emotions in crowds, classes of persons, and one "vicious" individual. Nudity appears as the obverse condition of viciousness, a monstrous desire to torture and

mutilate that body that puts its nudity on public display. The murderer reduces the naked body to a part, which he fetishizes, a part (the head) that one normally exposes anyway.

Most significant, public nudity here signifies a feminization of the male body, in the sense that powdering, painting, and bejewelling the body are signs of a feminine attitude. The poem suggests that it is not the nude female body but rather the feminization of the nude male body that gives rise to intensely turbulent emotions in public performance. Male nudity is feminized when it becomes an element of an aesthetic performance, of a dance. The act of exposing the genitals, in public and for aesthetic effect, is feminine, regardless of whether the genitals are male or female. For this reason, perhaps, it is very difficult to find examples of total male nudity in German modern dance. Droste sometimes performed in a loincloth (as in his St. Sebastian dance) but never completely nude, as Berber sometimes did.

Despite the shocking effect of this poem, it is the image of Berber's body that dominates the book. Even the body of the male nude in "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte" impersonates the powdered, orchidaceous body projected by Berber in the other poems/dances. The brief, theoretical poem immediately following "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte," titled "Versuchung," is "dedicated to Anita" and purports to describe Berber's body. The poet identifies her "slender naked boy thighs," her "slender purple petals," her whiteness, her fullness, her "clouds of powder," with particular actions or movements: the spreading of "countless raptures," the breathing of the wind, the pressing of desires, the quivering of flesh and the clinging of things to it, the veiling of lights, the gleaming of glass, the undulating of tassels, the waving of the arms, the pulling of "immeasurably wide spaces," the entwining and winding of circles. These movements, ascribed to the nude female dancer as a set of events devoid of narrative context, awaken male desire over and over again, in "circle and circle," and create "temptation," which threatens to destroy or corrupt the male body. It is movement performed by the female body, not anything spoken, that tempts the male poet.

But what does it mean for feminine movement to tempt the male poet? Because Droste wrote the great majority of the words in the book, including all the poems made into dances, it would seem that temptation implies a kind of fatal submission to language, an urge to write, to speak, to disclose morbid desires, the exposure of which addictively enslaves him to the one person who understands him, his partner, the female dancer. In spite of the lurid implications for nudity in male aesthetic performance theorized by "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte," the riskiest, "most naked" manifestation of male vulnerability is apparently not nudity in performance but writing and speech that motivate performance. The relation between language and bodily movement is as symbiotic as the relation between Berber and Droste.

Narrative-free movements of the female body motivate the male body to write, to speak, to inscribe, to narrate the female body as a dance. But in seeking union with the female body through dance, the male body becomes female insofar as it impersonates the feminine signs of the powdered, painted body. At the same time, the female body displays signs of masculinity: "slender naked boy things," "boy arms," a knifelike form. The relation between language and movement is ambiguous, interpenetrating, with the result that neither language nor dance nor nudity can lead to greater authenticity of being . For Wigman, movement constructed authenticity of being, and language (writing) was an initial manifestation of movement. For Berber and Droste, however, modern dance and the language that motivates it undermine secure categories of sexual difference, and in doing so they also expose narrative itself, in language and in dance, as morbid, decadent, a pathological mode of signification. Modernity itself then refers not to any condition of inauthenticity but to consciousness of the idea that the authenticity (and therefore the inauthenticity) of signs is a myth. The pleasure of the modern body derives from the supposition that narrative can no longer contain the body to which it refers, that performance does not contain enough signs to signify the unspeakable aspects of desire and identity.

The book amplifies the ambiguity of the relation between language and dance by its use of illustrations. These call attention to the problem of establishing the authenticity of the language that defines the modern body. Droste and Berber present sixteen photos of themselves taken in the Viennese studio of Madame D'Ora. Of these, only five include Droste, and only two feature him alone—the rest are of Berber alone. The photos bear no captions. Though the poses and costumes Berber and Droste adopt are from their dances, the photos are in no sense documentations of their dance performances; rather, the poses give the photos their own lurid, glamorous value. The sequence of pictures constitutes an artwork that shows the female body's capacity to exist independently of either its partner or its "original" performance. Berber undermines the authority of this glamor by including three of her own drawings, grotesque caricatures, of her head alone in profile. In two of them she appears bald-headed and wears outrageously huge earrings on her tiny ears, and in all three her heavily mascared eyelids vanquish any view of her eyes themselves. Yet each profile gives her a different identity: the first (bald-headed with small turban), fantastically Asian; the second (bald-headed with halo), a sort of monk wreathed in cigarette smoke; and the third, a sleek cosmopolitan with short-cropped black hair (she was actually a redhead).

These crude self-portraits give way to performance documentation: seven paintings, in color, by Harry Täuber of scenery and costumes employed in specific dances. These, preceded by Täuber's short prose preface, contain captions briefly describing the actions meant to occur within the contexts

depicted. Here Berber and Droste are neither glamorized nor caricatured but rather are given a tortured, "demonic," expressionistic look. Whereas the photos glamorize the dancers after having performed their dances, the paintings present the images the dancers strove to achieve through performance. These are stark, violent images, saturated with gloomy shadows, glaring light, and distorted perspectives. The small, anguished bodies of the dancers appear imprisoned in monumental spaces of terror and pain. Yet are these images any more authentic than the others?

Berber and Droste preface their book with two more images of themselves, drawings by the Viennese artist Felix Harta (1884–1967), who did many sketches of theatrical personalities. These are done somewhat realistically, with Berber and Droste, facing each other in profile, presented as debonair, even cute, embodiments of brash youth. But the very sketchiness of the drawings suggests a quite incomplete perception of the subjects. Altogether, the illustrations fail to stabilize perception of the author-dancers, reinforcing the governing idea that neither language nor movement nor music nor image nor nudity nor any complete unveiling that allows us to "see everything" has any special power to establish the authenticity of the modern body, to affirm that modernity is a progression toward authenticity of being, or to persuade us that liberation depends on achieving authenticity. Nevertheless, the complicated aesthetic of Anita Berber is as modernist as eurhythmics, Nacktkultur, and Nacktballett in linking modern identity to a more naked condition of being than premodern consciousness ever contemplated. Obviously, being naked in itself is not modern; yet it is difficult to imagine modernity reaching more extreme or controversial expression than through nude dance, than through the desire of a naked body to be seen making purely aesthetic movements that render both desire and the body more naked.

Figure 1.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School in Stuttgart. Photo by Alfred Ohlen,

from Adolphi and Kettmann, Tanzkunst und Kunsttanz (1927).

Figure 2.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School in Stuttgart.

Photo by Paul Isenfels, from Isenfels, Getanzte Harmonien (1926).

Figure 3.

Ursula Falke in a pose from Der Prinz (1925).

Photograph by Richard Luksch (Hamburg),

from Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe.

Figure 4.

Karla Grosch performing Metalltanz (1929)

at the Bauhaus experimental theatre

studio in Dessau, from OS, 93.

Figure 5.

Open-air rhythmic gymnastic exercises at the Dalcroze school

in Hellerau around 1913. From a contemporary postcard.

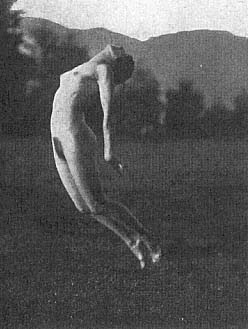

Figure 6.

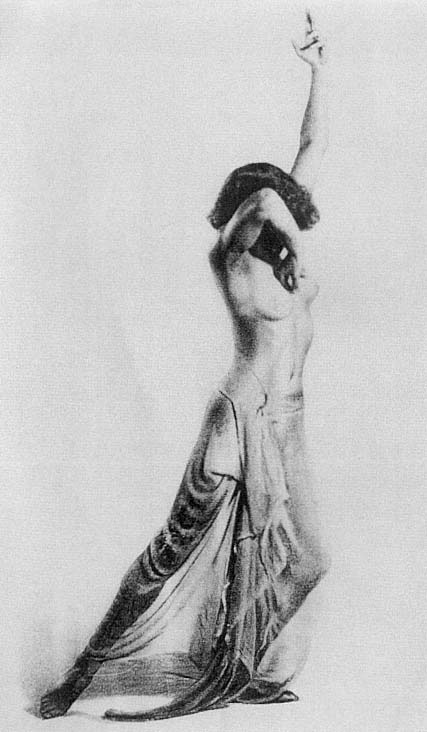

Gertrud Leistikow performing in a meadow

near Ascona, 1914. From HB, plate 68.

Figure 7.

Olga Desmond in "classical" (sculpted) nude

tableau, Berlin, 1910. From Andritzsky and Rauthenberg,

"Wir sind nackt und nennun uns Du, " 52.

Figure 8.

Male nudists surging toward the sun. From Hans Surén, Der Mensch und die Sonne (1924).

Figure 9.

Male and female nudists exercising together indoors at the Koch school in Berlin.

From Adolf Koch, Körperbildung/Nacktkultur (1932).

Figure 10.

Students of the Hagemann school in Hamburg. From Hagemann,

Über Körper und Seele der Frau (1927).

Figure 11.

Woman gymnast of the Hagemann school.

From the Joan Erikson Archive of the Harvard Theatre Collection.

Figure 12.

Brother and sister nudists. Photo by Lotte Herrlich, from Herrlich, Seliges Nacktsein (1927).

Figure 13.

Claire Bauroff, Vienna, 1925. Photograph by Trude Fleischmann, from Pastori (1983), 44.

Figure 14.

Grete Wiesenthal performing Pantanz, Vienna, 1910.

Woodcut by Erwin Lang, from Lang, Grete Wiesenthal (1910).

Figure 15.

Dancer at the Elisabeth Estas school in Cologne, 1927.

From RLM, plate 91, photographer unknown.

Figure 16.

Drawing by Hata Deli. From Ernst Schertel,

Der erotische Komplex (1932).

Figure 17.

Dancer at the Ida Herion school in Stuttgart.

Photo by Alfred Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann,

Tanzkunst und Kunsttanz (1927).

Figure 18.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School.

Photo by Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann.

Figure 19.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School.

Photo by Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann.

Figure 20.

Dancers at the Ida Herion school in Stuttgart.

Photo by Paul Isenfels, from Isenfels, Getanzte Harmonien (1926).

Top: Figure 21.

Dancers at the Ida Herion School. Photo by Isenfels, from Isenfels.

Bottom: Figure 22.

Dancers at the Ida Herion School. Photo by Isenfels, from Isenfels.

Figure 23.

Watercolor study by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner for the "Color Dance"

mural in the Folkwang Museum, Essen, ca. 1932, from Froning (1991), 97.

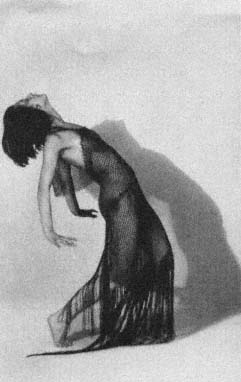

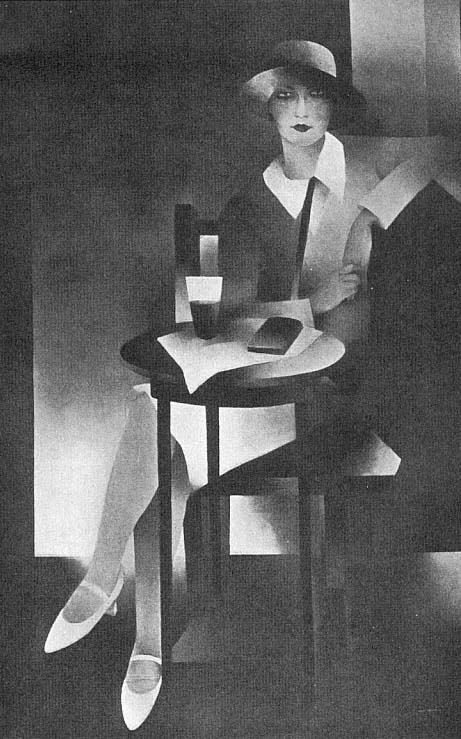

Figure 24.

Social dancing in a sleazy Berlin bar.

Watercolor by Jeanne Mammen, ca. 1929,

from Jeanne Mammen 1890–1976 (1978).

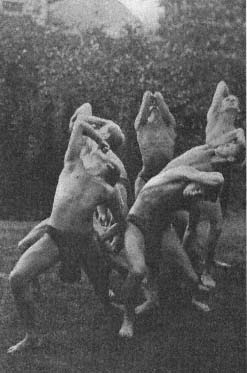

Figure 25.

Chorus girls in a Berlin nightclub, 1919, before the advent of Girlkultur ,

with spectators and performers in a puzzling relation to each other.

Photographer and source unknown, reproduction from postcard.

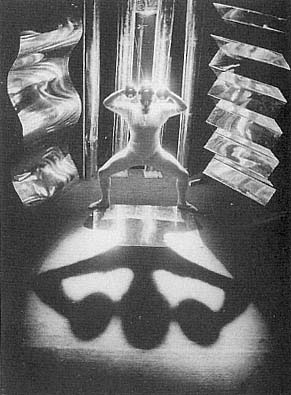

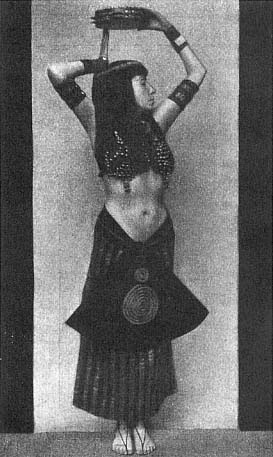

Figure 26.

Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste in a pose

from their St. Sebastian dance, Vienna, 1922.

Photo by Madame D'Ora, from Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste,

Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase (1922).

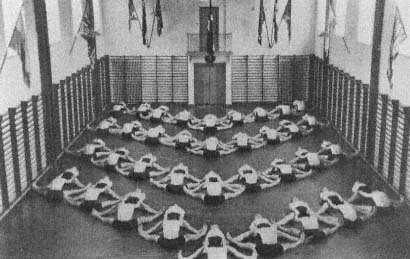

Figure 27.

Outdoor movement choir performing Laban

improvisation exercises, ca. 1924 from Laban,

Gymnastik und Tanz (1926).

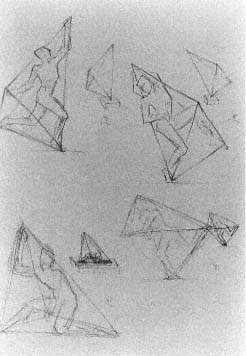

Figure 28.

A sketch, ca. 1924, by Rudolf Laban attempting to

describe human movement as a dynamic

geometric form. From Ullmann (1984), 34.

Figure 29.

Mary Wigman's Zweitanz (Studie) (1927);

Wigman is the figure on the left. Photo by

Charlotte Rudolph, from Rudolf Bach,

Das Mary Wigman-Werk (1933).

Figure 30.

Masked solo figure from Wigman's Totentanz (1926).

It was quite unusual for a Wigman dancer to perform on a carpeted

rather than polished wood surface. From Rudolf Bach,

Das Mary Wigman-Werk (1933).

Figure 31.

Image of the "prophetess" section of Wigman's Frauentänze (1934).

Photo by Charlotte Rudolph, from Wigman, Deutsche Tanzkunst (1935).

Figure 32.

Female Loheland (Fulda) student projecting

ambiguous sexual identity, ca. 1920. From Fritz

Giese, Körperseele (1924), plate 31.

Figure 33.

Page 323 of the Základy rytmického telocviku sokolského (1929),

one of hundreds of exercises in this huge manual on the Sokol system

of movement education, probably the most comprehensive

account of Dalcrozian movement pedagogy ever published.

Figure 34.

Interaction between male bodies performing Swedish

gymnastics. Leipzig, ca. 1926, from a contemporary postcard.

Figure 35.

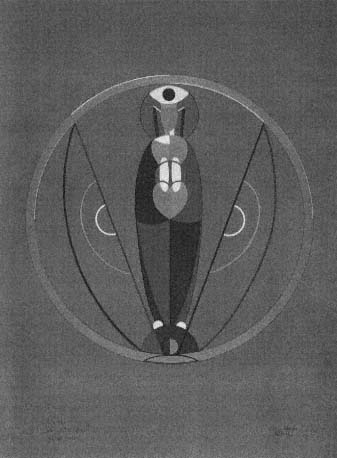

Design by Lothar Schreyer for Maria im Mond , Weimar, 1923,

with robot female idol perched on "dance shield." From DS 70.

Figure 36.

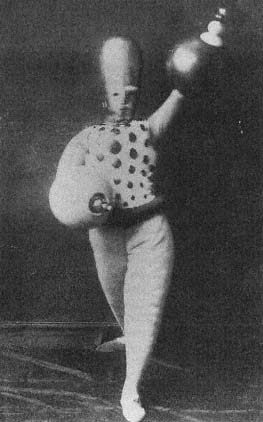

Image from Schlemmer's The Triadic Ballet ,

ca. 1925. Photo source unknown.

Figure 37.

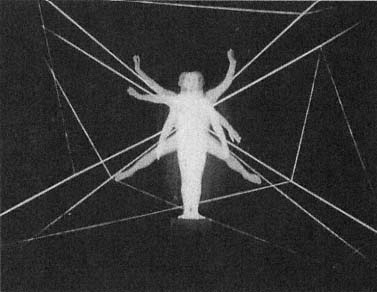

Experimental dance at the Bauhaus, Dessau, ca. 1927. Photo by Lux Feininger,

Copyright The Oskar Schlemmer Theatre Estate, 79410 Badenweiler,

Germany, Photo Archive C Raman Schlemmer, Oggebbio, Italy.

Figure 38.

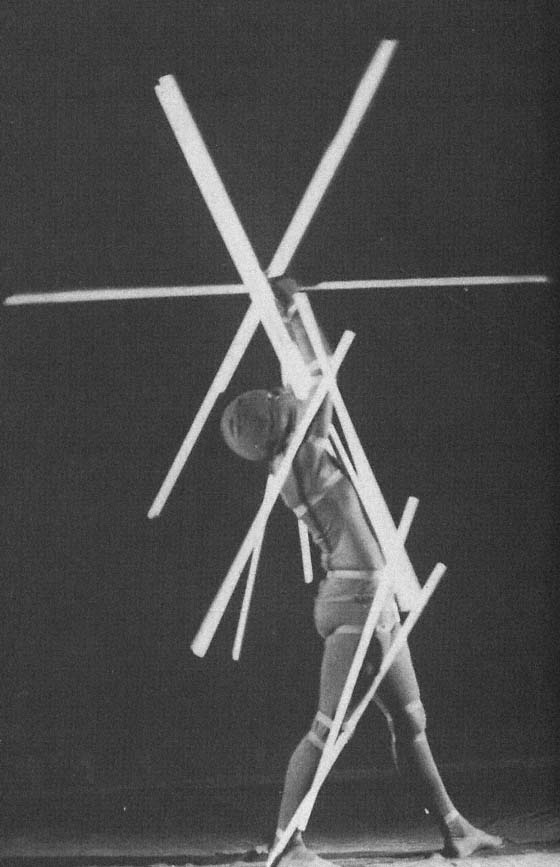

Image of the Staff Dance (1928–1929), performed by Manda van Kreibig

at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Copyright The Oskar Schlemmer Theatre Estate,

79410 Badenweiler, Germany, Photo Archive C Raman Schlemmer, Oggebbio, Italy.

Figure 39.

Edith von Schrenck. Photograph by

Hanns Holdt. Compare with Figures 40 and 41.

Figures 40 and 41.

Edith von Schrenck's Kriegertanz and Polichinelle (1919). Lithographs by

Ottheinrich Strohmeyer, from (left) Buning, Dansen en danseressen (1926),

and (center and right) Schrenck (1919).

Figure 42.

Grit Hegesa performing Groteske , Rotterdam, 1917.

Etching by Herman Bieling, from Netherlands Theatre Institute.

Figure 43.

Grit Hegesa dancing, Rotterdam, 1918.

Painting by Herman Bieling, from Netherlands Theatre Institute.

Figure 44.

Grit Hegesa, Berlin, ca. 1925. Painting by Emil van Hauth,

from The Studio , 92/401, 14 August 1926, 134.

Figure 45.

The Dancer Charlotte Bara , Worpswede, 1918.

Painting by Heinrich Vogeler from Küster,

Das Barkenhof Buch (1989), 113.

Figure 46.

Sent M'ahesa in a pose from an Egyptian dance, Munich, ca. 1915.

Photographed by Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski, from HB, plate 24.