3—

The House of the Seven Gables:

Secrets of the Heart

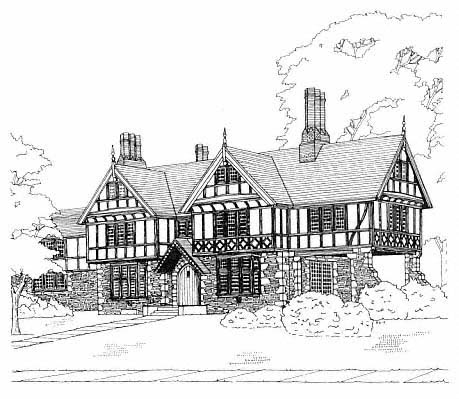

The actual House of the Seven Gables stands today "halfway down a bystreet" in the old New England town of Salem, a thriving pilgrimage spot for Hawthorne's readers. On the edge of a spit of land jutting out into Salem harbor, the house was originally the home of a sea captain who, as local lore has it, did a little smuggling as a sideline. An attic room with a hidden lock and secret crannies behind camouflaged doors marks the house as a repository of secrets where any closet door may be a false front and any wall panel a door to a hidden chamber. Gloomy and Gothic as any of Poe's labyrinthine mansions, the rambling, irregular house evokes curiosity about the purposes of the architect. The "House of the Seven Gables" recast and immortalized in fiction likewise stands, we are told, "halfway down a bystreet of one of our New England towns," an ancient mansion shrouded in gloom, wrapped in mystery, and rotting with secrets.[1] Halfway between history and fable, this quaint Gothic romance looms large in the American canon as an allegory of our history that is intensely local and intensely archetypal in its representation of the divisions and self-contradictions that characterize the Puritan origins of the American mind.

Hawthorne warned readers against literal-minded comparisons between the fictional house and its prototype or between Salem and the "old New England town" of his story by insisting on the term romance to describe his literary objectives. Romance refuses, in a sense, what one critic has called the "social responsibilities" of the novel by shifting the ground of language and undermining its referential function in favor of enhancing its symbolic possibilities.[2] In romance, persons, places, and things become primarily symbolic vehicles; their connection with the

realities of the material world is secondary. Yet the material world is as necessary to the project of romance as it is to the project of the novel: it is from our experience of actual structures that we derive a sense of structure and ultimately are able to contemplate structure and structuring as activities of the imagination necessary to the business of signification and meaning. This aspect of romance derives directly from transcendentalist cosmology in which the visible world is "charged," or impregnated, with symbolic potential and actualized by the seer, whose own idiosyncratic intelligence places it in a frame of reference made up of a unique body of experience, only part of which is shared; the other part is buried in the unconscious or kept among the "secrets of the heart," which Hawthorne believed bear on our simplest interactions with the natural and social world.

Like a stake driven into the ground, the first sentence of the story establishes the house as a focal point, moving the reader's eye inward from the lightly sketched map of a town in New England toward the "rusty wooden house, with seven acutely peaked gables, facing towards various points of the compass, and a huge, clustered chimney in the midst" (13). The sentence spirals inward toward the chimney, a vertical axis that marks the spatial center of this theater of action. Mention of the compass widens the imaginative frame beyond the parameters of a little New England town and puts the house at the center of a much larger, cosmic stage. Yet "halfway down a bystreet" also suggests marginality—something a little off center, something we would have to go out of our way to find. "Halfwayness" suggests both centrality and ambivalence; something that is neither here nor there but in between—geographically between town and countryside or (as in Salem) land and ocean, an emblem of the human situation, balanced on a point, as Pascal would say, between two infinities, where the local and the particular, understood deeply and widely enough, reveal the universal and the general.

Most critics would agree that The House of the Seven Gables is not Hawthorne's best novel. It is, however, remarkable in its own right as a compendium of contemporary ideas as well as a deconstruction of popular Protestant morality in which were

embedded some of the most cherished, lasting, and self-serving myths of Americanness. Written in 1851, several years after Hawthorne's sojourn among the utopian experimenters at Brook Farm, the book reflects in many respects the influences of the transcendental community, whose concerns and doctrines focused heavily on the interpenetration of spirituality and material culture and specifically on the question of proper domestic environment. The novel also reflects the deeper influences of Hawthorne's New England heritage, one that he experienced very much in terms of inherited guilt. The issue of ownership looms large; who owns the land, who owns what was built with other men's hands, what money has to do with ownership, and how a sense of entitlement transcends the legal parameters of inheritance and trade are all central questions in this troubling parable of American experience.[3] Issues of morality and spirituality, psychology, health, law and justice, and national character are brought together here in a complex examination of the house as a locus of human life and an outward and visible representation of most human concerns.

Like all Hawthorne's early works, The House of the Seven Gables reads as a fable or allegory, appearing to offer simple equations of meaning, stark contrasts between good and evil, and symbolic characters who represent a spectrum of human qualities. The rhetoric is that of a moral tale or sermon. Yet as in his other works, these conventions soon become complicated, ironic, and ambiguous; what seem in the beginning to be simple allegorical representations open out into multivalent symbols—signposts pointing down multiple and divergent paths to possible meanings. The house, with its seven gables "facing towards various points of the compass," is a symbolic space, a theater of human action whose inhabitants, like Everyman, play out a universal human drama of greed, punishment, and redemption.

Allegory as a form appealed to the preacher in Hawthorne; the notion of world as text that so lent itself to moral object lessons and so delighted the early New England poets and divines who looked to nature to illustrate scripture served his more subversive purposes nicely. Like most well-churched New

Englanders he was familiar with texts like Edwards's "Images or Shadows of Divine Things," where every element of the visible world was assigned some moral and pedagogical significance: hills and mountains were "types of heaven" because they were "with difficulty ascended"; rivers, converging from their diverse sources to flow toward the same ocean, provided a "wonderful analogy" to humanity drawing toward God; and trees conversely an image of the church, the body of Christ with its many divergent branches nourished from the same trunk.[4] The imagery, of course, comes directly from scripture, but its insistently precise extension into metaphysical conceits was absorbed in a peculiarly dogmatic and literal-minded fashion in American usage.

This same allegorical and analogical habit of mind, overtaken and ironized, allowed Hawthorne to develop a complex semiology in the world of his novels, where objects, spaces, colors, and all aspects of the physical world are supercharged with possibilities of meaning until their emblematic significance is overdetermined to the point of confusion and each allegorical signpost seems indeed to point "towards various points of the compass." The house serves as an emblem of the psyche; a mirror of the human face and form, sharing genetic characteristics with its inhabitants; a structural replica of the social institutions that shape national character (the church, the family, the government); a text on which history is inscribed; a stage for a domestic morality play; a vaultlike repository for guilty secrets; a prison, a tomb, and a womb harboring the seeds of its own renewal. The house's appearance is deceptive; like humans whose faces belie their hearts, the evil that infests the house is concealed to the eye of the uninitiate, who may regard it with veneration rather than suspicion:

So little faith is due to external appearance that there was really an inviting aspect over the venerable edifice, conveying an idea that its history must be a decorous and happy one, and such as would be delightful for a fireside tale. Its windows gleamed cheerfully in the slanting sunlight. The lines and tufts of green moss, here and there, seemed pledges of familiarity and sisterhood with Nature; as if this human dwelling place, being of such old date, had established its prescriptive title among primeval oaks and whatever other objects,

by virtue of their long continuance, have acquired a gracious right to be. A person of imaginative temperament, while passing by the house, would turn, once and again, and peruse it well: its many peaks, consenting together in the clustered chimneys; the deep projection over its basement story; the arched window, imparting a look, if not of grandeur, yet of antique gentility, to the broken portal over it opened; the luxuriance of gigantic burdocks, near the threshold; he would note all these characteristics, and be conscious of something deeper than he saw. He would conceive the mansion to have been the residence of the stubborn old Puritan, Integrity, who, dying in some forgotten generation, had left a blessing in all its rooms and chambers. (255)

The house, like the body that houses the soul of a sinner, is an ambiguous text, open to readers who are "conscious of something deeper" and yet are constrained to interpret these deeper things through the filters of their own innocence or guilt.

At its simplest, most parabolic level, the story of this house recalls, like a good Puritan sermon, several biblical parables and proverbs: the Pyncheons have built their house not on the rock of truth and justice but on a sandy foundation of greed, deception, and injustice. It is a house divided against itself. It is, like the house of Israel, an ancient edifice now rotting from within. Into its midst comes a stranger, who is really a rightful son, to destroy and rebuild it from its foundations, removing the curse that has been the source of its inner degeneration. The outline of Christian salvation history is reiterated in the house's story, from original sin to the moment of redemption.

The imprint of Puritan sermons is etched clearly on the novel's pages. Adopting the voice of the prophet and the rhetoric of the early Puritan jeremiads that warned the people against falling away and called them to awaken to their condition, the narrator of this tale stands above the action and outside narrative time on a moral pinnacle from which he can read signs and portents in the history of this household that bode ill for the future if the people continue in their path of greed, insularity, and enslavement to moribund traditions. He might have taken as an epigraph Edwards's warning in "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" that "the foolish children of men miserably delude themselves in their own schemes, and in confidence in their own

strength and wisdom."[5] Like the second and third generations of settlers' children who fell away from the motivating vision that brought their fathers to the new world, the Pyncheons have "laid up for themselves treasures on earth where moth and rust corrupt." Yet their punishment remains long unrecognized because it comes in the form of gradual diminishment and decay of the family line. As the narrator points out, "There is something so massive, stable, and almost irresistibly imposing in the exterior presentment of established rank and great possessions that their very existence seems to give them a right to exist; at least, so excellent a counterfeit of right, that few poor and humble men have moral force enough to question it, even in their secret minds" (30). Over time, evil can come to be accepted as normal, but that acceptance does not right the imbalance in the spiritual economy. It is only a culpable form of blindness that delays restoration of harmony and prolongs the dissemination of evil. What is "real and present" in solid, material form can obscure things that are more profoundly real and more powerfully operative, though only recognizable by those who have not been dazzled and blinded by the light of the visible world.

But the visible world is impregnated by the spiritual and eventually and inevitably manifests the good or evil forces that govern the latter world. Thus, the "stately mansion" that seemed to the early Judge Pyncheon nothing less than a fitting tribute to his own august character, a "fair emblem," harbors in itself the seeds of its own destruction:

Ah, but in some low and obscure nook—some narrow closet on the ground floor, shut, locked and bolted, and the key flung away; or beneath the marble pavement, in a stagnant water puddle, with the richest pattern of mosaic work above—may lie a corpse, half decayed, and still decaying, and diffusing its death scent all through the palace! The inhabitant will not be conscious of it, for it has long been his daily breath! Neither will the visitors, for they smell only the rich odors which the master sedulously scatters through the palace, that pool of stagnant water, foul with many impurities, and, perhaps, tinged with blood—that secret abomination, above which, possibly, he may say his prayers, without remembering it—is this man's miserable soul! (201–202)

Prophetically pre-Freudian in his understanding of the psychology of repression, Hawthorne details the psychological dimensions of his moral allegory with amazing clarity: the thing suppressed has more power than the thing made conscious, and that power is deeper and more dangerous than any of the forms of power by which waking life is governed. The inhabitants, like the house, are haunted and are subject to the powers that haunt them. Their minds, like their rooms, are spaces occupied by invading spirits. The narrator's description of the Judge Pyncheon now alive, Clifford and Hepzibah's cousin, reiterates this pattern of subtle and progressive degeneration: "In his youth, he had probably been considered a handsome man; at his present age, his brow was too heavy, his temples too bare, his remaining hair too gray, his eye too cold, his lips too closely compressed, to bear any relation to mere personal beauty" (56).

Into this scene of moral degeneration comes a young stranger, a Maule, descendant of the original builder, a new breed of man who, like his wizard ancestor, works his own kind of magic with the mysteries of new technology. He is a photographer, who turns light into visible forms, exposing corrupting secrets, mystifying the uninitiate, and finally embracing the daughter of his enemies in a redemptive act that promises a new covenant. The return of the laborer's descendant to claim his inheritance and exhibit his "magical" and unorthodox power leads to the verification of land stolen from the Indians in the hidden deed. Self-delusion, moral blindness, hypocrisy, and complacency all come in for the usual excoriation here, not simply as evils to which the human heart in its perennial weakness is prone but as genetic flaws in national character, bred into it by the very institutions that perpetuate culture and transmit it from generation to generation in an increasing heritage of guilt and moral impotence.

With the double edge of the social critic who draws his wisdom from the institutions he condemns, Hawthorne's narrator retails the story of original betrayal:

Old Matthew Maule, in a word, was executed for the crime of witchcraft. He was one of the martyrs to that terrible delusion, which should teach us, among its other morals, that the influential classes, and those who take upon themselves to be leaders of

the people, are fully liable to all the passionate error that has ever characterized the maddest mob. Clergymen, judges, statesmen—the wisest, calmest, holiest persons of their day—stood in the inner circle round about the gallows, loudest to applaud the work of blood, latest to confess themselves miserably deceived. If any one part of their proceedings can be said to deserve less blame than another, it was the singular indiscrimination with which they persecuted not merely the poor and aged, as in former judicial massacres, but people of all ranks; their own equals, brethren, and wives. (15)

As Hawthorne's sermon-bred audience well knew, the proper use of the past lies in its prophetic portent for the present; application means drawing the analogy and heeding the warning. The voice of the anti-institutional Emersonian prophet rings clearly here and is made more sonorous by the heritage of guilt borne by a son of the self-righteous judges who cast the first stones at the witches in Salem in the generation of Matthew Maule. The narrator's animating vision seems to penetrate to the very heart of things and reach far beyond them to their widely rippling social and historical implications, though whether his capacity to "see" is prophetic or fanciful remains for us to judge.

An even earlier voice than those of the Puritan preachers is echoed here; the warnings of Jesus to a community whose institutions and practices have grown corrupt and whose edifices of power are rotting at the foundations are reiterated here in the dire reminders of the consequences of building on a foundation of greed and guilt a house standing over an unquiet grave haunted by restless spirits seeking restitution for injustices that time does not heal. The deep distrust of institutional religion and of civil structures with similar claims to authority makes the story of this old New England patrician family an American morality tale whose message is a secular version of the old call to repentance and renewal, abandonment of "the old man" and the old covenant, and establishment of a new order based on a new vision unclouded by archaic laws and habits of mind. And, indeed, the story ends with a promise of a "new covenant" in which familial and class antagonisms are obliterated and retribution for the sins of the past is accomplished.

As the story opens, the narrator, in his provocative way, begins by telling us how much he is not going to tell us. Though an account of the "lapse of mortal life, and accompanying vicissitudes" that have transpired within this house would "form a narrative of no small interest and instruction," he is going to "make short work" of the evidently rich and fascinating traditional lore attached to the old landmark; we shall have to settle for the comparatively paltry business of looking in on its present inhabitants. We must begin the story somewhere, and the true beginnings of things, he thus reminds us, lie buried deep in the past. The story we are about to hear is the tip of an iceberg of myth, lore, and history, informed by forces well beyond what is present and visible, though encoded in those material vestiges. If we read them carefully, they provide inklings, incitements to look further and deeper, to look again, to see more. We are not to look merely to satisfy idle curiosity of the sort that local passersby might indulge, however. Rather, we are invited to take moral stock of this place and its melancholy inhabitants; the place is to become a parable in wood and stone. Yet even as we make our judgments and read our lessons in it, we are to remember on what deceptive bases we judge the actions and appearances of men. We read always at the risk of misreading and so revealing ourselves to be bigots or fools. As we enter the story with the narrator as our guide, we embark on the slippery path of interpretation at our own moral peril.

The narrator, however, knows something of the way, though his own understanding is limited, speculative, and predicated, it seems, on much hearsay. He introduces himself as one long familiar with the household and all its curious stories. He is a seer; he has the double vision of a spiritual man who sees beyond the literal structures of the visible world to the invisible forces and spirits that animate it: "The aspect of the venerable mansion has always affected me like a human countenance" (13), he observes and thereafter induces us to regard its aspect under the same conceit. The more we do so, the more human it becomes, with its heavy "brows," it "venerable peaks," its "meditative look," and its unsightly shop door, divided horizontally, just under the brow of the front gable, looking out on the street like a half-closed and baleful eye. Here, as in "The Fall

of the House of Usher," the house seems more fully alive than its inhabitants. This impression of animation is made explicit to the point of irony when the narrator, carried away with his romantic conceit, declares that "the very timbers were oozy, as with the moisture of a heart. It was itself like a great human heart, with a life of its own, and full of rich and somber reminiscences" (32).

Like the house of Usher, this house reflects and is reflected by the faces and bodies of those who dwell within it, exposing their secrets by replicating their physiognomies for the world to read, a house that embodies something so profoundly and universally human that it has come itself to participate in the humanity of its inhabitants: so much so that "you could not pass it without the idea that it had secrets to keep, and an eventful history to moralize on" (32). The windows of the house are frequently referred to as eyes, looking from their various oddly angled perspectives onto the street or garden. Its "clustered chimney" becomes, in a windstorm the day of Judge Pyncheon's death, a "sooty throat" that makes a "vociferous but somewhat unintelligible bellowing" (248).

As the narrative continues, these metaphors exceed the bounds of simple comparison and are increasingly literalized. The house indeed seems to breathe an atmosphere of brooding melancholy, and the walls creak with untold stories. The large looking glass that had hung for generations in one of the rooms "was fabled to contain within its depths all the shapes that had ever been reflected there." If he only knew how to look at it properly, the narrator seems to believe, he could "read" its contents: "Had we the secret of that mirror, we would gladly sit down before it, and transfer its revelations to our page" (26). The only obstacle that seems to stand between our ignorance and the revelations of the shrouded past is our inability to read the hieroglyphics inscribed on the material world. The answers to our riddles lie before us but are written in a language only the most discerning can decipher. Thus, the contemplation of any object becomes an effort to draw forth its stories, its lessons, the truths it has to tell us. Hawthorne's sense of the ways in which values inhere in the physical structures we erect is reminiscent of Thoreau's meditations on houses as value-bearing ar-

tifacts in Walden. In Seven Gables the home is a moral force-field where we enter into a mysteriously reciprocal relation with the inanimate objects and spaces that are the locus of daily life.

As we contemplate the old Pyncheon house, the narrator pauses to remind us in his paradoxical way of both the uniqueness and the universality of the revelations about to ensue: "Though the old edifice was surrounded by habitations of modern date, they were mostly small, built entirely of wood, and typical of the most plodding uniformity of common life. Doubtless, however, the whole story of human existence may be latent in each of them, but with no picturesqueness, externally, that can attract the imagination or sympathy to seek it there" (31). In this sardonic comparison a keynote is sounded: we must look into the past for an understanding of what is most deeply human. The present is a time of diminishment, sterility, and "plodding uniformity." But the blueprints of even our most vestigial forms can be discovered in the relics, like the hoary old house, that have survived the ravages of time, and though they recall an era of great sins and great sinners, they may serve to make us take measure of some loss of greatness that has befallen us all.

As the house reflects its human inhabitants, so they reflect back its architectural characteristics, which appear like family traits that show up transliterated in each face that bears them. Architectural terminology creeps into the descriptions of faces and human forms. The original Colonel Pyncheon, for instance, was "a gentleman noted for the square and ponderous courtesy of his demeanor" (19); Hepzibah is "black, rusty, and scowling," a woman whose "brain was impregnated with the dry rot of its timbers" (58); and Clifford is broad-faced and luminous, like the arched window of his room.

But Phoebe, who has not been molded to the rigid forms of this old structure but has been left to grow in a freer atmosphere untainted by the inherited house and all its accumulated guilt, is all sunshine and spirit and seems to move about the place with the freedom and pervasiveness of light and air. Like Holgrave, the photographer, she brings into this gloomy den of antiquity her own kind of sunshine and magic—a benevolent

"witchcraft" to match his wizardry, a "natural magic" that enables her to "bring out the hidden capabilities of things." Women like Phoebe, the narrator declares, are able mysteriously "to give a look of comfort and habitableness to any place which, for however brief a period, may happen to be their home. A wild hut of underbrush, tossed together by wayfarers through the primitive forest, would acquire the home aspect by one night's lodging of such a woman, and would retain it long after her quiet figure had disappeared into the surrounding shade" (71). Thus, she transforms her room in the old house, which "had resembled nothing so much as the old maid's heart; for there was neither sunshine nor household fire in one nor the other, and, save for ghosts and ghostly reminiscences, not a guest, for many years gone by, had entered the heart or the chamber" (68–69). A few weeks after Phoebe's arrival her triumph over the dark powers invested in the house is already manifest:

The grime and sordidness of the House of the Seven Gables seemed to have vanished since her appearance there; the gnawing tooth of the dry rot was stayed among the old timbers of its skeleton frame; the dust had ceased to settle down so densely, from the antique ceilings, upon the floors and furniture of the rooms below—or, at any rate, there was a little housewife, as light-footed as the breeze that sweeps a garden walk, gliding hither and thither to brush it all away. (123)

In pathetic contrast to this paean are the scenes of Hepzibah's domestic impotence, where the house and the forces of nature themselves seem deliberately to defeat her attempts to revive some spirit of warmth and hospitality. Thus, during a stormy afternoon, "Hepzibah attempted to enliven matters by a fire in the parlor. But the storm demon kept watch above and, whenever a flame was kindled, drove the smoke back again, choking the chimney's sooty throat with its own breath" (197).

The secret of Phoebe's power lies in her youth; her womanhood, with all the healing powers ascribed to it by the romantic imagination; her innocence of the family guilt; but perhaps more importantly, in the circumstances of her life, which have put her in normal relation to the world and spared her the de-

forming isolation of this inwardly turned prison-house of the soul. She is "practical"—not prey to debilitating fancies or enslaved by memory, history, or tradition. She is a woman of her own time and place whose indifference to unsolved mysteries and unpaid moral debts disarms the ghosts of the past. By contrast, the house, like its inhabitants, seems a figure of the obsessed introspective, turned always inward to feed on his own brooding imaginings, immune, after long years of isolation, to the corrective effects of social intercourse. Holgrave, himself a visitor from the world beyond the gabled walls, recognizes the character of Phoebe's healthful influence and pronounces prophetically, "Whatever health, comfort, and natural life exists in the house is embodied in your person. These blessings came along with you, and will vanish when you leave the threshold. Miss Hepzibah, by secluding herself from society, has lost all true relation with it, and is, in fact, dead; though she galvanizes herself into a semblance of life, and stands behind her counter, afflicting the world with a greatly-to-be-deprecated scowl" (190).

Miss Hepzibah's chronic scowl finds its opposite and counterpart in Clifford's childlike gaze. Both look out on the world from their framed and limited perspectives—she from her shop door and he from the arched window of his chamber. Both have lost that "true relation" with the larger world that Holgrave speaks of and see it through veils of alienation and fear. Clifford's window is of "uncommonly large dimensions, shaded by a pair of curtains," and when he goes to view the passersby in the street below he "throw[s] it open, but keeping himself in comparative obscurity by means of the curtain" (142), thus maintaining the protective but debilitating isolation that has so diminished him and his pathetic sister.

Thoreau's warning that possessions may come to possess their possessor could serve as an epigraph to this moral tale, where the dwellers seem possessed by the house and where the loss of propriety in that relation leads to the sickness of soul that seems so palpably to affect dwellers and dwelling alike. Throughout the narrative we are led thus to ponder the reciprocities of moral influence that characterize our relation to the material world. The power of those influences is reaffirmed in

the final vision of the house at the story's end; after its secrets have been exposed and its guilt expiated by the marriage of a Pyncheon and a Maule, it becomes, under new occupancy, "a substantial, jolly-looking mansion, and seemed fit to be the residence of a patriarch, who might establish his own headquarters in the front gable and assign one of the remainder to each of his six children, while the great chimney in the center should symbolize the old fellow's hospitable heart, which kept them all warm, and made a great whole of the seven smaller ones" (170). Clearly the house is not evil in essence, only in usage. Having regained something of its original innocence by virtue of a redemptive act, it partakes of the vitality and health of its new inhabitants.

The tendency to regard the material world as infused and impregnated amounts to a secular version of incarnational theology just this side of animism. Hawthorne and his transcendentalist neighbors shared something very close to this world-view, which in less philosophical form was well entrenched in the popular imagination of their contemporaries. The world was, they believed, charged with moral significance and manifested in every particular the presence of the divine. Sins and secrets inhered in the objects made by men, just as redemptive grace inhered in nature. In light of this general notion Hawthorne's passages about natural beauty are more than sentimental fancies; they are reflections on the ways in which nature exerts its renewing influence on the bumbling work of human hands. Thus, the narrator pensively remarks, "It was both sad and sweet to observe how Nature adopted to herself this desolate, decaying, gusty, rusty old house of the Pyncheon family; and how the ever-returning summer did her best to gladden it with tender beauty, and grew melancholy in the effort" (33).

The one grace of this ravaged mansion is the foliage and garden that surround it. "In front, just on the edge of the unpaved sidewalk, grew the Pyncheon Elm, which, in reference to such trees as one usually meets with, might well be termed gigantic. . . . It gave beauty to the old edifice, and seemed to make it a part of nature. . . . On either side extended a ruinous wooden fence of open latticework, through which could be seen a grassy yard, and, especially in the angles of the building, an enormous

fertility of burdocks" (31). The garden is a refuge for Clifford and Phoebe, gentle souls who flee the house when they can and seek solace in this place where life can flourish—where there is still some balance between the forces of nature and domestication. It is "the Eden of a thunder-smitten Adam, who had fled for refuge thither out of the same dreary and perilous wilderness into which the original Adam was expelled" (134). Here in the garden, some of the crucial scenes of the story take place because here in the garden, balance survives.

The house, however, is a dark, dank, unhealthy place. Houses seem to be necessary evils, blemishes on the face of nature. In the spirit in which Thoreau declares in his essay on civil disobedience that "that government is best which governs least," Holgrave believes with Thoreau that that house is best that separates least from nature. In both cases, manufactured structures are suspect, their utility and propriety are to be reassessed by each successive generation in light of present needs, and the entrenchment of tradition and dogma are to be resisted. Otherwise, those structures become stifling and confining and, in limiting change, growth, and "natural" development, breed sickness in the body politic.

The language of health and sickness attended much of the contemporary discussion of architecture as well as of social and political structures. Andrew Jackson Downing popularized the notion that the design of buildings had a significant impact on the health of their inhabitants, particularly in matters of heat, ventilation, and "atmosphere"—a word that was taken both literally and figuratively, as was the notion of health itself, which in popular theories combined physical and spiritual well-being. Hawthorne's treatment of the atmospherics of the Pyncheon house, where spiritual decay is made manifest in mold, rot, and dank air that slowly sicken the people within, reflects this widespread belief. The theories of William and Bronson Alcott and others about the direct influence of the domestic environment on the health of mind, soul, and body were well known, thoroughly discussed, and to some degree tested in the utopian communities at Brook Farm and Fruitlands. Nor was it only professional builders or small groups of experimental philosophers who thought of homes and houses as determinants of

mental, spiritual, and physical welfare. Ministers routinely addressed the issue of the home as a formative environment whose "atmosphere" shaped the character and attitudes as well as affected the bodily health of children growing up in them; clergymen extended their exhortations beyond matters of training and discipline to prescriptions of pure air and proper ventilation.[6]

Architecture as a practical science with significant moral implications partook in the general romantic belief that manufacture must follow nature in order to promote a proper relation between public and private life. "Following nature" meant espousing some idea of organicism and a holistic approach to understanding human nature and needs. In architecture this meant building, as Downing put it, "houses with feeling." A house with feeling would provide direct access to and experience of nature by modifying the intellectual severity of classical lines and looking to forms found in nature for impetus or models. It would always be surrounded with trees, shrubbery, and other foliage; model homes depicted in popular publications of the day were surrounded by trellises and vines that gave them the general appearance of having sprung from the soil itself.[7] This aesthetic, in large part a reaction against the dogmatic abstractions of Enlightenment ideals of symmetry, proportion, and rectilinearity and against the pretensions of Federalist and Greek revival styles, is reflected in the attention to the healing influences of nature on the sickly House of the Seven Gables—most notably the protective shadow of the ancient Pyncheon elm: "It had been planted by a great-grandson of the first Pyncheon, and though now four-score years of age, or perhaps nearer a hundred, was still in its strong and broad maturity, throwing its shadow from side to side of the street, overtopping the seven gables, and sweeping the whole black roof with its pendant foliage. It gave beauty to the old edifice, and seemed to make it a part of nature" (32). The narrator goes on to describe other foliage and the garden behind the house with their softening effects on the grim mansion. Nature sustains and redeems the house and its inhabitants, providing a refuge and place of sanity to offset the deranged and unhealthy interior environment.

The notion of visible and invisible worlds as structurally analogous is reinforced in another vein by the obvious analogies between the image of the House of the Seven Gables and text of The House of the Seven Gables. As in The Scarlet Letter , the book and its central symbol bear not only the same appellation but other similarities that confuse the distinctions between the two. The house has three stories and seven gables radiating outward "towards various points of the compass." Each of the three stories is occupied principally by one of the three reclusive inhabitants: the first by Hepzibah in her kitchen and cent shop; the second by Clifford, who watches the world from behind the veil of his arched window; and the third by the mysterious boarder, Holgrave, a photographer whose art seems descended from the wizardry of his ancestors and whose fate is bound to the old house by dint of an inherited wrong that remains to be righted. The house's foundations were laid in early colonial history, and on its weathered walls are inscribed the guilty secrets of an old New England family.

The book, similarly rooted in the Puritan origins of its writer, falls rather nicely into three sections, each with seven chapters and each focused in turn on the house's three inhabitants. Including the narrator there are seven principal characters, though the narrator occupies a curious position halfway between the characters of whose world he seems so intimately a part and the audience, to whom he speaks as a familiar. The tripartite division of the text creates a symmetry that reiterates the structure and tensions of the house itself. What seems to begin as simple allegory acquires as the story proceeds a multiplicity of symbolic dimensions; simple dichotomies branch and tangle into increasingly complicated issues as the house becomes a more and more inclusive symbol of every aspect of life, history, and relationship. Conventional boundaries between the world of the text and the world outside the text dissolve as the two worlds mirror one another in an endless reiteration of signs and symbols, and the simplest objects assume archetypal dimensions. Symbolic numbers, shapes, and geometrical configurations abound; in scene after scene the architecture of the house reiterates itself in a spatial symbology that explicitly evokes comparisons with psychic and linguistic syntax,

and the mind finds itself caught in a hall of mirrors where everything is mind looking at itself with the vision of Emerson's "transparent eyeball."

The equation among house, text, and human psyche, with their tripartite divisions, anatomical likenesses, and architectural congruencies, is like that established in Walden and "The Fall of the House of Usher," but here the analogy is taken a step further as the story of this divided house grows into an increasingly explicit allegory of American history, with its terrible heritage of guilt, oppression, expropriation, and hypocrisy. The house becomes a microcosm of the structures and conditions of American life as Hawthorne reads into it a story of stolen land, guilt, and retribution (themes that Faulkner later amplifies in a southern sequel). And indeed all the characteristic conflicts of American life: class conflict, institutionalized hypocrisy, the chronic tension between family, tradition, and orthodoxy, on the one hand, and separation, innovation, and heresy, on the other. Already in its beginnings the nation was a "house divided against itself," and those divisions are represented in this microcosm as inequities of class, race, and gender play out their consequences in this family drama.

Deeply embedded in American mythology is a belief in original integrity now lost. Until the redemptive moment is accomplished, the house is at odds with the earth on which it sits—a spot of ground the narrator calls "disputed soil." "The House of the Seven Gables, antique as it now looks," he reminds us, "was not the first habitation erected by civilized man on precisely the same spot of ground" but was erected "over [the] unquiet grave" of the earlier settler, thereby ignoring the legitimate claims of his children (12, 14). The parallel between the house and the human psyche here emerges again: the grand edifice represses—literally shoves underground—the secret that will become its curse. What is buried and what is manifest are at odds, and the house lacks integrity because the forces that divide it are built into its foundation. Though the narrator proceeds thereupon to detail the history of Matthew Maule's prior claim and settlement, underlying this story is an even earlier story of dispossession that began with the invasion of those "civilized men" into a country already in the keeping of earlier

claimants. Here the theme of stolen land, which Faulkner later takes up and carries further, begins to loom large in the economy of crime, guilt, and punishment that so characterizes American mythology and fiction. With the mention of land wrested from the Indians, the story's allegorical potential begins to unfold and widen.

Like The Scarlet Letter and other novels of its generation, this novel conflates religious with political allegory: a story of expropriation, settlement, establishment, and building on a foundation of usurpation and injustice. The project of claiming, settling, and civilizing a continent is presented with profound ambivalence, and Hawthorne's characteristic preoccupation with guilt and expiation as a fundamental part of national heritage surfaces again. The question of what constitutes a legitimate claim to ownership is brought up explicitly not only in an ironic presentation of the complicated legalities that over time made such claims more and more ludicrously attenuated but also in the observation that over time the distance between de jure and de facto ownership tends to widen. The actual occupants of the "Pyncheon" land to which the claim is found, "if they ever heard of the Pyncheon title, would have laughed at the idea of any man's asserting a right—on the faded strength of moldy parchments, signed with the faded autographs of governors and legislators long dead and forgotten—to the lands which they or their fathers had wrested from the wild hand of nature by their own sturdy toil" (24).

Domestication and appropriation are distinguished as two entirely different enterprises, the one legitimate and noble, the other presumptuous, dangerous, and self-deluding. Those who live on and with the land, savages or settlers, are presumed to be both more intimate with nature and more properly owners of the land by virtue of their intimacy with it, regardless of the law's systems of legitimation. The representatives of the superimposed legal and social order with their "moldy parchments" operate at several removes from this primeval and archetypal relation and to legitimate their seizure of power trust to words and abstractions and indirect, oppressive forms of power derived from dead predecessors. The question of ownership is posed here not only in political and historical terms but in wider

moral terms as well. What decides right of ownership? Inheritance is at least two removes from that direct claim established by those who inhabited and cultivated the land. Those who buy it have a lesser claim; those who inherit it have a very tenuous one indeed. And yet, the narrator suggests, our whole system of justice and property rights is based on just such dubious claims. Their dubiousness derives as well from the fragility of the written word. Documents are mere shadows, vestiges, or pale representations of the realities they purport to describe and control. We have mistaken, he seems to say, the insubstantial for the substantial. That confusion sounds one of the keynotes of the novel, in which the relation between the solid, substantial, and manifest and the abstract, spiritual, and hidden comes to seem increasingly problematic and reciprocal.

This line of argument culminates in a profoundly ironic self-referentiality when the very notion of textuality in a text-based culture is brought into question. What are the Constitution and the Bible, secular and sacred texts on which we predicate our whole system of communal life, but insubstantial "moldy parchments" whose claim on us is subject to the same kind of radical questioning? Hawthorne posits a similar theological conundrum in which, once again, the word made flesh throws into question the word preserved on stone or parchment.

The argument of Emerson's "American Scholar," based similarly on a distrust of institutions, books, and the recorded wisdom of past generations, is reproduced almost verbatim in some of Holgrave's impassioned speeches about the oppressive presence of the past. In that essay Emerson declares the book (and the institutions erected on the foundation of "sacred texts") a danger to freethinking men when used to blind them to and shield them from the specific needs and issues of their own generation. Book learning becomes a form of idolatry, and attentiveness to the lessons of the past degenerates easily into sterile antiquarianism that impedes originality and prevents the development of new models of action. This same view of scholarship as enslavement and history as a record of diminishment resounds in each of Hawthorne's longer tales, which end in a utopian's cry for resistance and renewal.

Holgrave, of course, is the new man described in Emerson's "Self-Reliance"—a Thoreauvian hero recast and domesticated—and a forerunner of Faulkner's Quentin Compson, with his love-hate relationship to his familial and regional past. Holgrave possesses a new, unfamiliar, and mysterious kind of power in being a photographer, using a technology that at the time was still marvelous, baffling, and even a little frightening. (He tells Phoebe, when all is revealed, "In this long drama of retribution I represent the old wizard, and am probably as much a wizard as ever he was" (275), leaving her and us to ponder the ambiguity of that claim.) He writes for magazines, places little stock in books. This vocation suits well his conviction that things are transitory, to be let go, not preserved in musty libraries and made into relics. As Phoebe gets to know him, she learns to admire precisely those qualities in him that characterize the emerging American hero of fiction and philosophy—radically individualistic, undomesticated, nomadic, and spiritually enlightened: "Homeless as he had been—continually changing his wherabout, and, therefore, responsible neither to public opinion nor to individuals; putting off one exterior, and snatching up another, to be soon shifted for a third—he had never violated the innermost man, but had carried his conscience along with him" (157). An opponent of stability and tradition, his asocial tendencies are construed as responsiveness to a higher law.

Unburdened by connections, a solitary content to be much alone with his conscience, he resembles in certain obvious ways the "Son of Man" with nowhere to lay his head. For Holgrave, the material world needs to be divested of its oppressive burden of sentimental and symbolic significance in order to be habitable. Material objects must not be invested with such power over the imagination, or they will drain the vitality from those who own them and threaten eventual collapse of the soul into a state of servile sterility. Life can be preserved and perpetuated only if equal and opposite forces come from within and without—if the quantity of a man's spiritual potency and inner vision is equal to the tendency of the material world to overwhelm those channels to truth with insistent and immediate claims for attention. Yet Holgrave, like his prototypes, is a man

who knows the past more intimately than do those around him. It is not ignorance of the past but freedom from its prescriptive force that he strives to maintain. The hero that Hawthorne was helping to define, and who has survived far into the twentieth century, is the one who can bear the burden of the past without letting it crush him and can reverse the balance of forces so that the past is turned to his purposes and not vice versa. One of the primary strategies of that hero with a hundred faces is to abandon old structures and erect new ones or, if he must, to live in them under protest and insist that such settlement is a temporary expedient.

Condemning the Pyncheon house as unwholesome, antiquated, and stifling, Holgrave thus justifies his continuing presence in it to Phoebe by declaring that he is "pursuing [his] studies" there, adding, "not in books, however. . . . The house, in my view, is expressive of that odious and abominable Past, with all its had influences, against which I have just been declaiming. I dwell in it for a while that I may know the better how to hate it" (163–164). Waxing eloquent on the virtues of escaping the past and its ossified institutions, he declares, "I doubt whether even our public edifices—our capitols, state houses, courthouses, city hall, and churches—ought to be built of such permanent materials as stone or brick. It were better that they should crumble to ruin once in twenty years, or thereabouts, as a hint to the people to examine into and reform the institutions which they symbolize" (163). The old house with its portal "broad as a church door," its gables reaching "skyward" like steeples, and its succession of judges and magistrates comes to symbolize every kind of edifice left by past generations as a vestige of their faltering social structures.

Family itself is one of the institutions that bears the seeds of its own destruction. It, in fact, exercises the most pernicious kinds of claims of the past on the present. "To plant a family! This idea is at the bottom of the wrong and mischief which men do. The truth is, that, once in every half century, at longest, a family should be merged into the great, obscure mass of humanity, and forget all about its ancestors. Human blood, in order to keep its freshness, should run in hidden streams, as the water of aqueduct is conveyed in subterranean pipes" (164).

Healthy pluralism keeps generating new heterogeneous forms, which are those most likely to flourish, withstand transplanting, and breed character fit for survival. Reconfiguration and adaptation are the keys to social longevity and are endangered by inbreeding, perpetuation of the stabilizing structures of the past, and isolation. Lest we miss the moral, the narrator adds to Holgrave's Emersonian outburst his own comment: "It seemed to Holgrave—as doubtless it has seemed to the hopeful of every century since the epoch of Adam's grandchildren—that in this age, more than ever before, the moss-grown and rotten Past is to be torn down, and lifeless institutions to be thrust out of the way, and their dead corpses buried, and everything to begin anew" (164).

Clifford joins Holgrave in this general condemnation of the misuses and misapplications of the past. Their protestations recall with comic explicitness Emerson and his younger disciples preaching the same doctrine from their different generational perspectives. Clifford's apotheosis comes in a remarkable and uncharacteristically vehement diatribe delivered to a hapless stationmaster he encounters on his flight from the old mansion to parts unknown:

The greatest possible stumbling blocks in the path of human happiness and improvement are these heaps of bricks and stones, consolidated with mortar, or hewn timber, fastened together with spike nails, which men painfully contrive for their own torment, and call them house and home! The soul needs air; a wide sweep and frequent change of it. Morbid influences, in a thousandfold variety, gather about hearths, and pollute the life of households. There is no such unwholesome atmosphere as that of an old home, rendered poisonous by one's defunct forefathers and relatives. (228)

Clifford is also the one to articulate the vision of a future free from the weighty stabilities of house and home and all they represent:

It is my firm belief and hope that these terms of roof and hearthstone, which have so long been held to embody something sacred, are soon to pass out of men's daily use, and be forgotten. Just imagine, for a moment, how much of human evil will crumble away, with this one change! What we call real estate—the solid ground to build

a house on—is the broad foundation on which nearly all the guilt of this world rests. A man will commit almost any wrong—he will heap up an immense pile of wickedness, as hard as granite, and which will weigh as heavily upon his soul, to eternal ages—only to build a great, gloomy, dark-chambered mansion, for himself to die in, and for his posterity to be miserable in. He lays his own dead corpse beneath the underpinning, as one may say, and hangs his frowning picture on the wall, and, after thus converting himself into an evil destiny, expects his remotest great-grandchildren to be happy there! (229–230)

Both Clifford's and Holgrave's convictions are those of victims of the evils they describe. Hepzibah, who does not have their capacity to reflect on her situation, has simply fallen prey to it and has consequently become "a kind of lunatic, by imprisoning herself so long in one place, with no other company than a single series of ideas, and but one affection, and one bitter sense of wrong" (160). Phoebe, however, though by name and heritage implicated in the family drama, has remained, by virtue of her womanly innocence and lateral kinship, unblighted by the family curse and so is able to temper this zealotry with an innate practical, sensible immediacy that the men have to strive to achieve by taking much thought. She simply brings into the old house her own modest standards of comfort and commodity and unfolds its possibilities in those terms. Thus, almost without taking thought, like the Victorian "angel of the house" that she is, she makes the house "like a home to [Holgrave], and the garden a familiar precinct" (161).

In the end it is the combination of Phoebe's unspoiled feminine influence, Holgrave's strategic revelations, and the healthy spirit of compromise that acknowledges, expiates, and dispenses with the lingering burdens of the past that provides the new beginning that is the end point of so many American stories. The resolution, though in some ways distressingly formulaic, manages to provide satisfaction on a number of philosophical questions, the main one being the question of appropriate living arrangements. Pyncheons and Maules together leave the old house for a new place in the country where they are to live an idyllic life as an extended family, steeped in nature, tranquillity, and philosophical conversation in something like the man-

ner of the utopian communes still in fashion. Old Uncle Venner, with a last backward glance, fancies that he perceives the ghost of Alice Pyncheon, released at last by the resolution of the troubled secrets, "float[ing] heavenward from the House of the Seven Gables" (277). Houses, like souls, can be redeemed, but only by being released from the burdens of the past and claimed anew by each living generation. Fitzgerald's observation that the history of the United States is a history of beginnings provides an apt summary to the work of Hawthorne's generation, heirs of the revolution who translated its political protests and claims into metaphysical terms and sought to free themselves from an old world and its structures by abandoning them and recreating gardens in which each successive generation could rediscover innocence.