5—

The Awakening and "The Yellow Wallpaper":

Ironies of Independence

The Awakening and "The Yellow Wallpaper" have by now become classic texts in feminist studies, two of the stories most often cited in discussions of women's entrapment in oppressive forms of domestic life.[1] Following many precedents in the long tradition of Western tragedy, the women in these stories, caught in social and actual structures that repress and confine them, end up enacting gestures of self-liberation that are deeply and ironically self-destructive. The tensions and paradoxes that characterize American culture assume peculiarly acute form in women's writing, where ambivalences about domestic life as a hindrance to the realization of the ideal of freedom are complicated by the inaccessibility and even irrelevancy of that ideal to women in a culture whose romantic mythology has referred so particularly to male experience. In such a culture conscious and ambitious women have had to imagine what to strive for in the relative absence of female precedents. For these women, houses, traditionally the domain of feminine activity, though designed and controlled by men, have represented either "gilded cages" (the gilding on some of which was a very thin veneer) or a medium they could turn to their otherwise frustrated purposes of creative expression and exercise of intelligence and power.

Throughout The Awakening Edna Pontellier, wife of a wealthy New Orleans businessman, is engaged in a restless search for a place and a way of life in which she can be comfortable and free and in which she can be in relation to, but not controlled by, the men she loves. The most definitive moment in Edna's desperate struggle for identity and autonomy besides her final swim to her death is her move into her little "pigeon house," a

four-room cottage to which she flees to escape the suffocating conventionalities of her overstuffed New Orleans mansion. Every setting in this story is emblematic; every room and porch and stretch of beach frame and enforce specific modes of behavior. Chopin uses houses both to define character and to serve as a graphic representation of interpersonal politics. The metaphorical and the literal merge in the structures of domestic life. Chopin's language of spatial relation is as allegorical as Hawthorne's; her characters' physical position in a room or defined space—above, below, inside, outside—always provides an important clue to the nature of the encounter taking place. Each of the three houses Edna inhabits during the nine-month span of the story generates certain kinds of action and inhibits others. Moving from one to another, she evolves from the status of captive to mistress of her environment, and, finally, finding that she cannot sustain that new role in the absence of legitimizing social supports, she dissolves into a space without boundaries as she swims to her death in the ocean.

The novel was written at the end of Chopin's ten-year writing career and met with a storm of critical outrage that put an end to her writing for the five remaining years of her life. Though by all accounts the twelve years between her marriage to Oscar Chopin and his death were "unusually fulfilling," and her relationship to her six children close and happy, there is no mistaking her profound sympathy for the plight of most women of her generation, who were confined in homes that bound them to a round of domestic and social duties that left little room for free expression of individual talents. Like her contemporary, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Chopin subjected the norms and structures of the Victorian United States to a critical scrutiny courageous in its prophetic identification of the pathologies of Victorian family life, particularly with respect to the effective imprisonment of women.

Chopin's father died when she was five, and during most of her youth at home and in a convent school, she saw women holding and exercising authority. Reflecting on the relevance of this female-dominated upbringing in a summary of Chopin's life and writing, Peggy Skaggs suggests that "this inconsistency between training and experience [might have] contributed to

the paradox between her own apparently happy marriage and her creation in fiction of female characters who feel stifled by the marriage relationship."[2] Of these characters, the most stifled and the most complex in her relation to the demands of domestic life is Edna Pontellier. Flanked on the one side by an archetypal "mother-woman," Mme. Ratignolle, whose pregnancy progresses contemporaneously with the story, and on the other by an eccentric "artist woman," Mlle. Reisz, whose unorthodox solitary life has given her an ambiguous, lonely freedom, Edna's search for a "place" for herself in the world takes on both literal and symbolic dimensions as she seeks some middle ground where she can design a life between the extremes of engulfment and isolation.[3]

The story opens at a summer resort where a group of cottages are arranged in proximity to the "House," where the families share their seasonal rituals. When we first meet Edna she is returning from a walk on the beach with Robert, her young friend and would-be lover, whose frequent presence in her household creates the first of a series of triangular relationships in the book in which Edna is in the middle position. Chopin dramatizes the relationship among the three of them, Robert, Edna, and her husband, Leonce, by the simple device of seating them on the cottage porch: "When they reached the cottage, the two seated themselves with some appearance of fatigue upon the upper step of the porch, facing each other, each leaning against a supporting post" (173). This juxtaposition, particularly when Leonce comes to join them, seating himself in a chair above and between them, alerts the reader not only to the nature of their respective relationships but to the general importance of spatial symbolism in the novel. Here Edna and Robert are equals and intimates. Their informality and their childlike playfulness differentiate them from and subordinate them to Leonce, who, emerging from the interior of the house, sits in a chair above them, literally supervising the two now at his feet. Exhilarated from their walk in the air, their freedom of spirit and their manner contrast markedly with his sober propriety.

Robert's family owns the House—the central building in the complex. His enterprising mother has developed the resort as a source of income: "Now, flanked by its dozen or more cottages,

which were always filled with exclusive visitors from the 'Quartier Francais,' it enabled Madame Lebrun to maintain the easy and comfortable existence which appeared to be her birthright" (176). The woman who has taken her fate into her own hands and has made her house into a means of independence as well as a social center to support a way of life she enjoys provides a direct contrast to Edna, whose sense of entrapment is at least in part a matter of temperament and training. Three women in this novel other than Edna have achieved various kinds of independence and contentment. They complicate rather interestingly the theme of women's oppression to which discussions of the novel so often revert. It is possible, Chopin shows us, for a woman to be a mistress not only of her husband's home but of her own environment and destiny, given certain proclivities, sacrifices, and a creative imagination. In light of these examples, Edna's plight becomes considerably more problematic; she is not simply a prototypical woman but is a woman for whom the available options do not serve. The question of why then becomes a subtler problem.

Edna's marriage provides one clue. Though she spends a good deal of time apart from her husband, when he is home, his wishes are paramount, and his presence so fills the spaces they share that Edna chooses whenever possible to escape, to find breathing space. In chapter 11 Leonce comes home to find her late at night waiting for him on the porch and asks, "What are you doing out here, Edna? I thought I should find you in bed" (217). His sense of her proper place consistently differs from hers and is governed by convention rather than by recognition or understanding of her habits and needs. Time and space are carefully regulated quantities for him; her casual treatment of both troubles his sense of propriety and control. Nevertheless, he reserves to himself the right to the small irregularities that so disturb him in her. On this same occasion, after Edna has been persuaded to return indoors and to bed, Leonce remains on the porch she has vacated. She calls to him to ask whether he is coming in. "'Yes, dear,' he answered, with a glance following a misty puff of smoke. 'Just as soon as I have finished my cigar'" (219). Leonce does not question his own right to re-

main outside at night, make exceptions to the regulations he imposes on his household, or claim his moments of solitude.

One Sunday morning Edna makes her escape from the cluster of cottages where shared domestic life engulfs her; she allows Robert to row her to an island where an old woman, Mme. Antoine, lives in rustic contentment. Tired in the afternoon, Edna accepts Mme. Antoine's offer of a room for a nap. Entering the house, Edna is charmed: "The whole place was immaculately clean, and the big, four-posted bed, snow-white, invited one to repose. It stood in a small side room which looked out across a narrow grass plot toward the shed, where there was a disabled boat lying keel upward" (226). This house is a refuge. The "small side room" where Edna takes a nap befits her desires: she is alone but watched over, private, accessible to the outside, away from civilizing constraints and duties. Spending a bucolic afternoon in a place apart, near the water, she allows feelings, curiosities, and desires that have no place in her life at home to begin surfacing. In this place where she has no given role a self can emerge whose contours she has yet to discover.

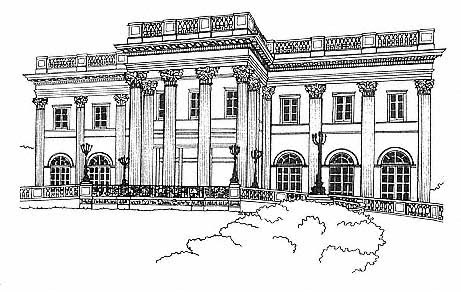

Shortly after this interlude we follow Edna to a third location. Whereas on the beach and at the island, both marginal places where social constraints are loosened, it has been relatively easy to lay aside the stringencies of upper-class social obligations, back in New Orleans we see her in a more confined and regulated setting—her "real life" has tightened on her like a corset, and the wistful imaginings begun in the freedom of the open-aired summer haunt her. Chopin describes the New Orleans house in some detail, guiding the reader's eye slowly around the facade and then the interior, awakening a host of assumptions about and associations with genteel southern life:

The Pontelliers possessed a very charming home in Esplanade Street in New Orleans. It was a large, double cottage, with a broad front veranda, whose round, fluted columns supported the sloping roof. The house was painted a dazzling white; the outside shutters, or jalousies, were green. In the yard, which was kept scrupulously neat, were flowers and plants of every description which flourishes in South Louisiana. Within doors the appointments were perfect after the conventional type. The softest carpets and rugs covered

the floors; rich and tasteful draperies hung at doors and windows. There were paintings, selected with judgment and discrimination, upon the walls. The cut glass, the silver, the heavy damask which daily appeared upon the table were the envy of many women whose husbands were less generous than Mr. Pontellier. (247)

Mr. Pontellier's generosity generally takes material or monetary form; he has supplied Edna with everything a woman of her station is supposed to want—which is to say, an abundantly furnished household where she is surrounded by material comforts and both natural and artistic beauty. The possibility that this accumulation of material things might be felt to encumber rather than enhance her life would not occur to him. Well cared for and in their proper places, his possessions, like his wife, demarcate his place in the world and serve as constant and gratifying reminders of his success in securing it: "Mr. Pontellier was very fond of walking about his house examining its various appointments and details, to see that nothing was amiss. He greatly valued his possessions, chiefly because they were his, and derived genuine pleasure from contemplating a painting, a statuette, a rare lace curtain—no matter what—after he had bought it and placed it among his household goods" (247–248). His possessions are his badges, his wife among them. They are testimonies to his taste and his power as well as to his wealth—all qualities by which he seeks to distinguish himself, very much in accordance with the standards of his class and time. But his satisfaction is joyless, taken not primarily in the aesthetic and other pleasures these things might offer but in what they signify. His house is a showcase that he tours to reassure himself.

In his own terms, vividly expressed in his orderly and abundant household, Mr. Pontellier is a model husband, and his expectations of his wife are in no way excessive—certainly no greater than, though different from, what he expects of himself. Therefore, when she fails to meet these expectations, he is not only disgruntled but bewildered because her growing apathy and resistance seem to him inexplicable. When one evening he finds fault with each dish at dinner, he snaps in some disgust, "It seems to me . . . we spend money enough in this house to procure at least one meal a day which a man could eat and re-

tain his self-respect" (251). Edna observes that he used to think the cook was a treasure, to which he responds that she, like any other sort of employee, needs supervision. Edna is not running the household up to his standards. Meals, like other commodities, are for him an index of right and successful ordering of life. Food is one element in the elaborate code by which he lives; the right kind of food eaten at the right time is one of many measures of propriety that form the foundation of his identity and self-respect. For Edna not to do her part to maintain this complex system and the values it implies is deeply troubling to him because so much of the maintenance of that system depends on her complicity. The life he has chosen is not possible without her consistent collaboration.

Edna retreats to her room after this scene. "It was a large, beautiful room," we are told, "rich and picturesque in the soft, dim light which the maid had turned low. She went and stood at the open window and looked out upon the deep tangle of the garden below" (252). Repeatedly, when she is troubled, Edna retreats to a place of solitude and space where, undisturbed, she can look both inward and outward—windows and window seats, porches, open doors, and thresholds draw her. As at her summer home she derived some peace from contemplating the limitless ocean, here she looks into the "deep tangle" of the garden below—another symbol of the wild freedom of what is natural, fluid, and unconscious. Her luxurious bedroom recalls the "gilded cage" so many women writers describe. Though from it she can look out on the lovely disorder of the tangled garden, it, too, is an enclosed space and an extension of the house—a wilderness carefully contained within walls, like Edna's own wildly blossoming inner life.

Edna's growing resistance to the material world that has become so oppressive surfaces again when Leonce wants her to help him get new fixtures for the library. She objects, "Don't let us get anything new; you are too extravagant. I don't believe you ever think of saving or putting by." Leonce's answer not only summarily dismisses Edna's concern but switches the terms of discussion to a logic formed in the marketplace, where money is the ultimate gauge of behavior: "The way to become rich is to make money, my dear Edna, not to save it" (253).

Following his pronouncement of this bit of accepted wisdom, he departs, leaving Edna in her classic posture of ambivalence, standing once again on the veranda picking bits of jessamine from a trellis as her husband leaves one domain, in which he is master, for another, in which he has a clearly defined and powerful place. Neither place is hers. The jessamine, like so many other natural things in the novel, momentarily answers Edna's hunger for simple, natural, sensual things, here opposed to the world of manufactured objects. Edna's resistance to spending and acquisition is clearly more symbolic than practical. Leonce's acquisitions are her burdens; his expenditures involve them in an increasingly complicated web of possessions and status symbols that it becomes her responsibility to maintain.

Furthermore, acquiring new things suggests an inability to enjoy the old ones—spiritual restlessness perhaps expressed in thirst for novelty. He spends very little time enjoying them; Mme. Ratignolle has observed to Edna, "It's a pity Mr. Pontellier doesn't stay home more in the evenings" (277)—and, indeed, we seem always to be seeing him poised for departure. The fact that he does not spend much time simply dwelling in and enjoying his home reflects a general incapacity to dwell in or enjoy—an ineptitude at the contemplative, the receptive, and the "feminine" capacities simply to be without doing or demonstrating.

Shortly after this, a visit to the Ratignolles' home presents a striking contrast to the Pontelliers', and Chopin complicates the questions she has raised about the oppressions of domestic life by presenting one that is remarkably satisfactory: "There was something which Edna thought very French, very foreign, about their whole manner of living. In the large and pleasant salon which extended across the width of the house, the Ratignolles entertained their friends once a fortnight with a soiree musicale, sometimes diversified by card-playing" (255). The wide-openness of this house contrasts significantly with the closely defined and heavily filled spaces of the Pontelliers' home. The spaces are meant and used for entertainment rather than for show—not exhibition halls but gathering places, humanized by activity rather than mummified by collections of objects. The people are the decoration and the decor, and the house is an instrument of their own radiant hospitality rather

than of restraint and protection. Nevertheless, the satisfactions of this way of life seem to Edna a function of something distinctly foreign and somehow inaccessible.

This visit is the first of a series of three visits Edna makes to homes of friends before reaching her decision to move out. Each represents a style of home life that confronts her with important questions about her own. She decides in a fit of melancholy to visit Mlle. Reisz, the eccentric, crusty spinster musician who piqued her curiosity during the summer soirees at the seaside cottages and who lives, Edna knows, alone in town. On the way Edna goes to the home of the Lebruns, Robert's family, to get Mlle. Reisz's address. Arriving at the Lebruns, where she seldom visits, Edna pauses to look at the forbidding architecture: "Their home from the outside looked like a prison, with iron bars before the door and lower windows. The iron bars were a relic of the old regime, and no one had ever thought of dislodging them. At the side was a high fence enclosing the garden. A gate or door opening upon the street was locked" (262–263).

This reference to this home as both prison and "relic" underscores the sinister aspect under which Edna is coming to regard her own. The unrenovated architecture here bespeaks an anachronistic and unreflective conservatism that harks back to European roots with no adaptation to modern life, preserving outmoded aesthetic and, implicitly, social values. The connection between aesthetics and morality is, throughout, quite direct, focusing primarily on elitist preservation of privacy, social distinction, and separation from the masses as well as the containment of female sexuality or sensuality within limits strictly controlled by the master of the house.

Here, as at the Ratignolles', the European ethos is specifically mentioned, as if to establish a contrast between indigenous and imported culture, the latter paradoxically represented as both more hospitable and open and, here, as cloistered and resistant to change. Clearly one of the questions Chopin is raising about Edna's situation is how much of it is a matter of the confused, hybrid moral atmosphere bred specifically in the United States and peculiarly in the South, with its mixed vestiges of French culture. Edna's Americanness is one of the qualities that distinguishes her from several of the other women in the novel, Mme.

Ratignolle, Mlle. Reisz, Mme. Lebrun, Mme. Antoine, and Maria all having either foreign blood or strong foreign roots.

Having arrived at the Lebruns' and having contemplated the forbidding facade of their house, Edna is not eager to go inside. Instead, she takes up her usual position on the threshold: "It was very pleasant there on the side porch, where there were chairs, a wicker lounge, and a small table" (263). Here, as in other scenes, Edna not only seems to prefer to situate herself between the indoors, where it is too confining, and the outdoors, where her place is not clear, but at a side entrance to the house, a place of entry that bespeaks intimacy, indirectness, and perhpas even intrigue. Her ambivalence toward this house and her ambiguous relation to it reiterate the unclarity in her relation to Robert, who, though for her representing ease, freedom, and release from the stringencies of her marriage, also comes from this milieu, which is in its way even more complicatedly confining and repressive. She does not stay long at the Lebruns and does not go inside, but she does procure the address she needs and moves on to find Mlle. Reisz's odd little top-floor apartment. The place seems to her as refreshingly eccentric as the woman herself, provoking, as she does, curious speculation:

Some people contended that the reason Mademoiselle Reisz always chose apartments up under the roof was to discourage the approach of beggars, peddlars and callers. There were plenty of windows in her little front room. They were for the most part dingy, but as they were nearly always open it did not make so much difference. They often admitted into the room a good deal of smoke and soot, but at the same time all the light and air that there was came through them. From her windows could be seen the crescent of the river, the masts of ships and the big chimneys of the Mississippi steamers. A magnificent piano crowded the apartment. In the next room she slept, and in the third and last she harbored a gasoline stove on which she cooked her meals when disinclined to descend to the neighboring restaurant. It was there also that she ate, keeping her belongings in a rare old buffet, dingy and battered from a hundred years of use. (266–267)

In every way Mlle. Reisz's apartment invites direct comparison with her character as we have come to know it: lofty, distant, eccentric, a little unpleasant, and yet harboring things of great

beauty and value that are not kept for show but for the sort of use to which only a skilled hand can put them. The apartment is divided into three functional parts, which suggests the simplicity of a life whose public and private enjoyments are carefully circumscribed and located in a simple living plan—a life from which much has been pruned but whose simplicity seems considered and chosen, not a circumstance imposed by force of necessity. The views from her windows reflect the wideness of an imagination that dwells on broader horizons than most, has a higher and wider vantage point. And even the slight air of neglect suggests an inhabitant preoccupied with "higher" things. This strange female hermit in her hermitage provides an interesting variation on the romantic Thoreauvian solitary so common in our fiction, very like Cather's Godfrey St. Peter or James's Maria Gostrey—creatures who perch in their small, carefully furnished nests awhile to observe the world from the privileged vantage point gained there and then move on, having "other lives to lead."

In this novel Mlle. Reisz's role, viewed in its allegorical dimension, is a complicated one. She is hardly a model for Edna, who, though drawn to the woman's idiosyncratic life-style, seems, in her chronic hesitancy, incapable of the sort of decisive sacrifice required of this breed of secular saints. Mlle. Reisz serves, however, to establish a pole on the spectrum of possible choices, giving Edna some gauge by which to measure and assess the dimensions of her own existence. As she reluctantly leaves the apartment, Edna pauses on the threshold to ask rather plaintively if she may come again. Here in the freedom afforded by the simplicity and candor of the place and its inhabitant, in the presence of the music from her piano, and in the light from her high window, Edna is freed to feel what she feels at a depth she has not often allowed herself to reach.

This is the romantic side of the experience of both the woman and her home. On a later visit the darker side of Mlle. Reisz's way of life shows through—the loneliness, the dinginess, and the insufficiency:

It was misty, with heavy, lowering atmosphere, one afternoon, when Edna climbed the stairs to the pianist's apartment under the roof. Her clothes were dripping with moisture. She felt chilled and pinched as she entered the room. Mademoiselle was poking at a

rusty stove that smoked a little and warmed the room indifferently. She was endeavoring to heat a pot of chocolate on the stove. The room looked cheerless and dingy to Edna as she entered. A bust of Beethoven, covered with a hood of dust, scowled at her from the mantelpiece.

"Ah! here comes the sunlight!" exclaimed Mademoiselle, rising from her knees before the stove. "Now it will be warm and bright enough; I can let the fire alone." (293)

This is a life easy to sentimentalize, hard to live. It is not a life Edna would be able to lead. The frequent mention of Mlle. Reisz's withered body, her quick irascibility, her ugliness, points as well to a certain imbalance in this kind of living—accepted, even raised to an art, but not ideal. At the time of this visit Edna is facing her own imminent solitude and begins here to come to terms with some of its consequences and costs. A contrast of this description of the apartment with the earlier one where the order, the view, and the fruitful simplicity were emphasized provides a measure of Edna's swiftly changing point of view.

It is Leonce's departure for an extended business trip that gives Edna her first real experience of solitude and freedom. With her children off to their grandparents, she luxuriates in her rare liberty:

When Edna was at last alone, she breathed a big, genuine sigh of relief. A feeling that was unfamiliar but very delicious came over her. She walked all through the house, from one room to another, as if inspecting it for the first time. She tried the various chairs and lounges, as if she had never sat and reclined upon them before. And she perambulated around the outside of the house, investigating, looking to see if windows and shutters were secure and in order. The flowers were like new acquaintances; she approached them in a familiar spirit, and made herself at home among them. (283)

This is Edna's first experience of a proprietorship of the sort that comes naturally to Leonce, who habitually does just such a mental inventory, though Edna's circuit of the house ends in the garden with the dogs and the flowers, where she picks up dry leaves and mucks about joyously in the mud. She brings both mud and dog into the house with her. For once she is able to see the possibilities of her home through her own eyes, rather than

through the anticipated judgments of her husband. The things that before were heavy with oppressive significance now appear simply as what they are—chairs to sit in, flowers to smell, recliners to lie on. As she takes in the house's parameters, she sees it whole, as if for the first time—as something she might in fact manage quite well, left to her own devices. Even her usual domestic domain Edna surveys with different eyes: "Even the kitchen assumed a sudden interesting character which she had never before perceived" (283). In her instructions to the cook, Edna says she will be preoccupied during her husband's absence and begs the cook to "take all thought and responsibility of the larder upon her own shoulders" (284). Like a child at play among her parents' belongings, Edna is trying out a new stance in relation both to the house and to the running of the household, asserting a new authority, in small ways breaking through deadening routines and finding with gratified surprise that there is nothing to prevent her doing so.

It does not take long after this realization for Edna to make her momentous decision to move into a place of her own. With precipitous haste, she seeks out a little house not far away and arranges to take it without reference to Leonce's wishes. This domestic rebellion is characteristic in several rather amusing ways: she does not go far—lingers, in fact, almost on the doorstep of her marital home; she acts quickly so as to avoid, rather than confront, the opposition she knows will come, but the action itself is amazingly radical for a woman of her kind in her position. She is energized by a passion and urgency that strikingly contrast with the lethargy, melancholy, fatigue, and stasis in which she seemed to be sunken in so many previous scenes: "Within the precincts of her home she felt like one who has entered and lingered within the portals of some forbidden temple in which a thousand voice bade her begone" (302). Yet this passion is only partly desire for independence; that desire is complicated by her growing attraction to Alcee Arobin, who supplies at least a significant part of her incentive to leave.

Like James's Isabel Archer, Edna is a woman governed by impulses whose conflicting nature she neither understands nor even fully suspects—both a wild and a domestic creature wanting love in terms that will leave her free, not sure how to use

freedom when she has it. And her situation raises an old American question in microcosm: what comes after a declaration of independence? Nevertheless, in the course of her life's events, it has become necessary to dissolve these bonds, regardless of what lies before her. In a state of radical alienation, she no longer recognizes her house as her home. Indeed, she has "awakened" to the fact that it never was, so that lingering in it seems an impropriety. Leonce has provided the norms. In his absence all that was normative has lost its raison d'être, belonging to a world and a logic of possession and identity that have nothing to do with her. He is her only connection with that world and the connection is rapidly dissolving. Her haste and anxiety have doubtless also to do with simple fear of being caught in transition—on the threshold—but more perhaps with making up for lost time: a long-unrecognized hunger is on the verge of fulfillment and grows in anticipation.

The process of moving demands that for the first time as a married woman Edna take stock of who she is and what she has apart from her husband: "Whatever was her own in the house, everything which she had acquired aside from her husband's bounty, she caused to be transported to the other house, supplying simple and meager deficiencies from her own resources" (302). Separating possessions is a way of separating on deeper levels. She is not a wealthy woman without Leonce. She has to be resourceful for the first time, careful to modify her tastes and acquisitions to available funds, to "make do."

Edna calls her little house the "pigeon house"—a name that reiterates a motif of bird imagery associated with her throughout. It is a place where she can rest between flights, a place she can escape from to try her wings and return to for safety. It is small but sufficient: the mahogany table Edna had formerly used would have almost filled the dining room. "There was a small front porch, upon which a long window and the front door opened. The door opened directly into the back parlor; there was no side entry. Back in the yard was a room for servants, in which old Celestine had been ensconced" (314). Everything Edna needs is almost literally at her fingertips: "There was but a step or two from the little table to the kitchen, to the mantel, the small buffet, and the side door that opened out on

the narrow brick-paved yard" (327). Much of Edna's satisfaction with her new home seems to lie in finding how little is sufficient. Like Thoreau in his cabin, she finds relative deprivation a source of new freedom. Its simplicity is also reminiscent of Thoreau's suggestion that a dwelling be self-explanatory and open to "reading" on entering. Simple, frank, unadorned with architectural niceties and subtleties, it is still a place where certain proprieties are maintained—the servants in their quarters, the "few tasteful pictures" on the walls, the books on the table, the fresh matting and rugs on the floors, the flowers in vases—but only in their simplest form. What is there is chosen with care by a woman accustomed to just such choices. Like Thoreau, her training in a more complicated kind of life shapes her tastes and priorities even in her iconoclasm. In her carefully appointed rooms, there is a well-considered concern for comfort and beauty as well as a rejection of opulence.

In the transitional period preceding her final departure, before Leonce returns, Edna gives one last dinner party in the big house. But what is intended as a celebration becomes a strange ordeal for her; she is again on a threshold, one foot in two worlds, caught suddenly in the old uncertainty that seems to be her besetting weakness:

There was something in her attitude, in her whole appearance when she leaned her head against the high-backed chair and spread her arms, which suggested the regal woman, the one who rules, who looks on, who stands alone. But as she sat there amid her guests, she felt the old ennui overtaking her, the hopelessness which so often assailed her, which came upon her like an obsession, like something extraneous, independent of volition. (309)

This passage encapsulates the ambiguities of Edna's transitional situation: she is exhilarated by her newly claimed authority, freedom, and self-determination, but at the same time she is plagued by apprehensions. She has not looked very far down the road, and the road beyond her gaze is dark. Like Ibsen's Nora, Edna may find herself in a cold world after slamming the door. The impulsiveness that gave her the strength to make her move will not serve to sustain her in her choice. The paucity of external supports for her choice will gradually become all too

clear. All these implications are adumbrated here by a vague feeling of unrest as she luxuriates for the last time in the comforts of the home she is leaving. The trade-off is costly in ways she is only beginning to imagine.

When Leonce hears of Edna's intention, he is predictably distressed and angry and refuses to regard it as a serious decision; rather, he trivializes it as a rash and unreasoned impulse. He begs her to consider what people will say, thinking not of scandal but of his "financial integrity." After all, as he points out, "it might get noised about that the Pontelliers had met with reverses, and were forced to conduct their menage on a humbler scale than heretofore. It might do incalculable mischief to his business prospects" (316). Here the portrayal of Leonce becomes almost caricature. Incapable of responding with authentic human emotion even to such outright rejection and abandonment, he can interpret Edna's actions only in terms of their potential social and economic repercussions. The day he hears the news he sends instructions to a "well-known architect" to remodel the house, instructing the architect to proceed with "changes which he [Pontellier] had long contemplated." In short order,

the Pontellier house was turned over to the artisans. There was to be an addition—a small snuggery; there was to be frescoing, and hardwood flooring was to be put into such rooms as had not yet been subjected to this improvement. Furthermore, in one of the daily papers appeared a brief notice to the effect that Mr. and Mrs. Pontellier were contemplating a summer sojourn abroad, and that their handsome home on Esplanade Street was undergoing sumptuous alterations, and would not be ready for occupancy until their return. (317)

Leonce's pathetic attempt to forestall the disaster Edna's move threatens to bring on him is made in the only terms he knows: by wielding the visible weapon of wealth and possessions. He can imagine only one solution to the problem because he can conceive of the problem only in one limited set of terms. Furthermore, the problem as he perceives it has more to do with appearances than with Edna's or even his own human needs. It would never occur to him that his notion of a solution

might in itself represent part of the problem: the house is the stumbling block for both of them; having become the medium through which they communicate, they are unable to understand their marriage independently of it.

Edna, in the meantime, has proceeded to settle into her pigeon house and is finding there a milieu of her own making that gives her a kind of power she could never have developed in competition with Leonce's. Like his, her house is a medium of self-expression:

It at once assumed the intimate character of a home, while she herself invested it with a charm which it reflected like a warm glow. There was with her a feeling of having descended in the social scale, with a corresponding sense of having risen to the spiritual. Every step which she took toward relieving herself from obligations added to her strength and expansion as an individual. She began to look with her own eyes; to see and to apprehend deeper undercurrents of life. No longer was she content to 'feed upon opinion' when her own soul had invited her. (317)

No passage in the novel is more reminiscent of Thoreau than this. The inverse relationship of the social or material to the spiritual, the equation of material simplicity with spiritual richness, and the notion that "things" bind and that emptiness liberates have deep roots not only in American romanticism but in ancient Eastern cultures in which the feminine is far more profoundly integrated than in our own. It is noteworthy, too, that what is described here as "filling" the house is an intangible—the atmosphere, the "warm glow" of Edna's presence—as though the relative absence of material objects had made way for something intangible that nevertheless required space to become apparent.

Edna's move into her house provides an opportunity for her to explore other kinds of liberation, first in her ill-fated love affair with Arobin and then in her attempt to pursue her more deeply felt love for Robert. The latter, however, not having descended to Arobin's level of libertinism, cannot follow Edna into her self-imposed social exile. It is interesting what a relatively minor role these love affairs play in Edna's emergence into a new consciousness of herself, however. The "love interest" in this story

is quite secondary to the theme of inner awakening, a drama in which the men in her life play necessary but subordinate roles. Indeed, the most sensual scene in the book takes place in the bedroom at Mme. Antoine's, where Edna, alone, awakens from sleep, stretches, and runs her hands along the contours of her own body, as if discovering and delighting in her own sensuality in a way quite different from that experienced in the give and take of a sexual encounter with a man. Such scenes and discoveries are the more poignant because they are short-lived; she does return, and must return, to a life in which social relationships shape both behavior and consciousness.

In chapter 38, we find Edna once again alone, this time on her own little porch at the pigeon house in the evening: "Instead of entering she sat on the step of the porch. The night was quiet and soothing" (345). A number of scenes like this one in the last half of the book echo the opening scenes. Whereas her late-night meditations on the porch at the summer cottage irritated Leonce, here she is free to indulge in this little freedom with peace and pleasure, but not for long. As in so many stories about women, the road to freedom turns out to be a cul-de-sac. Edna's choices have unfit her for the society in which she has to live, and she is ill-equipped to live elsewhere. She finally returns to the beach, alone, abandoned by Robert, separated from her family, and unable to imagine a viable future. Walking there amid the reminders of those less complicated days when no bridges had been burned and her difficult awakening seemed to hold such promise of commensurate fulfillment, she comes on a young couple at the island repairing their summer house. She remarks, "I supposed it was you, mending the porch. It's a good thing. I was always tripping over those loose planks last summer" (347–348).

Edna's experiment fails. Unlike Hester Prynne, Edna would never have found a niche in society by herself, would always have lived on the margin without any sustaining community but what she was able to gather about herself by sheer strength of character. She has neither Hester's charisma nor her moral fortitude. Edna is not of heroic stature; she is simply a woman with longings and needs common to women, caught in a social web where these needs are not met, but ill-equipped to spin her own

web outside it. The new house is a refuge, but it is not enough. The walls around her are only one of many structures that would need to be, as Hawthorne puts it, "torn down and built anew" for her choices to be viable. So her story ends, like that of so many women who have tried singly to resist the fate assigned to them, in a symbolic act of self-destructive self-liberation. Unable to fashion a freer life by redefining or redesigning the structures that imprison her, she makes a final journey into a realm without walls, a place of endless, undefined space, fluidity, boundlessness, in which she can lose herself completely, free in the only way she knows how to achieve freedom from the restrictions of civilized life.

Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" provides a striking companion piece to The Awakening. The writers were contemporaries dealing with the same realities of late Victorian American life. Gilman's own married life was much less satisfying than Chopin's and ended in divorce after prolonged periods of "nervous prostration" that seemed to her later to have been directly related to the confinements of domestic life. Her abiding interest in the conditions of women's lives was grounded in her own lifelong struggle to come to terms with them. "The Yellow Wallpaper," which several medical professionals among Gilman's early readers recognized as a remarkably accurate portrayal of mental breakdown, is grounded in autobiography. Its dramatic contours are sharper and less ambiguous than those of The Awakening , though the two share major themes. Taken together the stories present the old, tragic double bind of female fate pushed to its extremes and ending in suicide or madness. Both tragedies are a result of the same elements: enclosure, not only physical "imprisonment" in a house but in a system that entraps women in confining roles that weaken and diminish their natural powers; trivialization by the men in authority over these women, so that their most urgent pleas for understanding go unheard; lack of a "common language" that will allow them to identify and speak their needs.

The narrator of "The Yellow Wallpaper" is a woman who remains unnamed throughout the story. The only names we hear are those she hears—her husband's diminutive endearments.

As the story begins, she presents herself as a submissive, compliant, affectionate wife who aims to please her husband and is attempting to follow her doctor's orders for recovering from a "condition" that seems to be postpartum depression. Presumably in the interests of her recuperation, the couple has moved into an old "ancestral hall" in the country for the summer. She describes it as "a colonial mansion, a hereditary estate, I would say a haunted house and reach the height of romantic felicity—but that would be asking too much of fate!" (3). She insists, however, that there is "something queer about it" for it to have been let so cheaply and have remained "so long untenanted" (3). With these mild portents, Gilman squarely situates her story in the Gothic tradition. The house and the woman are the dual focus of the story, the woman's body, like the house, imprisoning a restless spirit that has long been undernourished.

The analogy is made quite explicit on the first page of the story by the woman herself, who realizes that translating her concerns about her body into concerns about the house is the only way in which she is going to be allowed to give them expression:

John says the very worst thing I can do is to think about my condition, and I confess it always makes me feel bad.

So I will let it alone and talk about the house.

The most beautiful place! It is quite alone, standing well back from the road, quite three miles from the village. It makes me think of English places that you read about, for there are hedges and walls and gates that lock, and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people. (4)

Like the woman, the house is isolated, complicated, confined, ensconced in a luxurious private domain but having little relation to the larger world. The difference between her perceptions of the house and her husband's provides more significant information about her psychological state and susceptibilities:

There was some legal trouble, I believe, something about the heirs and co-heirs; anyhow, the place has been empty for years.

That spoils my ghostliness, I am afraid, but I don't care—there is something strange about the house—I can feel it.

I even said so to John one moonlight evening, but he said what I felt was a draught, and shut the window. (4)

John is the force of "realism" opposing her romanticism; shutting the window he summarily classifies, dismisses, and shuts out the stimuli that are awakening her fancy. The obvious and almost comic use of the Gothic motifs here—moonlight, ghosts, gusts of wind, free-floating anxiety—serves to accentuate the ambiguities of the story and to raise the questions posed by all Gothic romances: What are the boundaries between imagination and reality? What is "real"? Who can determine what is "there" if the senses cannot be entirely trusted? The radical difference between John's unimaginative rationality and his wife's feelings and fancy, attaching here to the house and its atmosphere, puts the reader in a position of choosing repeatedly between their opposed interpretations of the significance of objects and events.

When they have dwelt there a few days, the narrator begins to find other reasons to complain: she does not like their room, having wished for "one downstairs that opened onto the piazza and had roses all over the window, and such pretty old-fashioned chintz hangings! But John would not hear of it" (5). Again the house serves as a vehicle for her displaced discontentments. She wants access to the outside world and natural beauty. He chooses for her a room with barred windows designed to protect children, a "big, airy room . . . with windows that look all ways, and air and sunshine galore" that was "a nursery first, and then playroom and gymnasium. . . . For the windows are barred for little children and there are rings and things in the walls" (5). The paradox of this room is that it seems a congenial environment, open to sunlight and air, large and commodious. But the bars and the rings, the obvious intention of the design, suggest that there is something inappropriate and even sinister about the woman's assignment to this space. It is deceptive in its allowances.

The woman's mood of revolt grows stronger as she notices more and more details about the abhorrent room:

The paint and paper look as if a boy's school had used it. It is stripped off—the paper—in great patches all around the head of my bed, about as far as I can reach, and in a great place on the other side of the room low down. I never saw a worse paper in my life. One of those sprawling, flamboyant patterns committing

every artistic sin. . . . The color is repellent, almost revolting: a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight. It is a dull yet lurid orange in some places, a sickly sulphur tint in others. (5)

The woman's disgust continues to find expression in attacks on the house rather than on the husband. As in The Awakening , the house becomes a symbolic substitute for the marriage—an incarnation of the contract between wife and husband. The Gothic language she uses here to describe the sickly colors and shabby accoutrements of the room to which she is consigned takes on the "coloring" of the room: lurid, ghastly, and jarring. She uses the repugnant interior to reflect her own internal state of revulsion and rebellion, identifying more and more closely with the surroundings even as she expresses her violent distaste for them. Doubtless her distaste for her own violent feelings is equally powerful.

Her husband, however, misses all this. Oblivious as Leonce Pontellier, John blandly observes that the place is doing her good and ignores her pleas, which become increasingly frantic, to renovate the house on the reasonable ground that it would be a waste of effort just for a three-month rental period. She presses him further, "Then do let us go downstairs. . . . There are such pretty rooms there" (6). But he refuses this as well. Like Leonce Pontellier, John figures value in terms of what makes economic sense. Other modes of sense-making are alien to him. He has no way of identifying with his wife's desperation, and she is powerless to make him understand it. She wants to go "downstairs," symbolically retreating from the "higher" realms of rationality, consciousness, and intellect to a place that is closer to the ground or more "grounded" in sensuality and connected to the outside, natural world. But his answer is to take her in his arms, calling her a "blessed little goose," and exaggerate her petition to the point of absurdity in order to trivialize and dismiss it, saying, "He would go down cellar, if I wished, and have it whitewashed into the bargain" (6). The husband's joking concession both bypasses the wife's feelings and once again sidesteps her purpose; his offer to "go down cellar" is not a real concession to a real need but an exaggeration of the

expressed need that makes it appear ridiculous. Moreover, his offer to "whitewash the cellar" betokens exactly the kind of repression of his own unconscious and hers that he is engaged in.

The woman, for reasons of health as judged by husband and doctor, is confined to the room with the hated wallpaper, and her hostilities toward her environment become paranoically focused on the wallpaper as the cause of her oppressed spirits. The projection becomes increasingly bizarre and explicit: "This paper looks to me as if it knew what a vicious influence it had! There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck and two bulbous eyes stare at you upside down" (7). This grotesque vocabulary reflects what Poe would call the "phantasmagoria" in her mind. She attributes or projects more and more onto the inanimate wallpaper, like the narrator in Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher." The house assumes the position of the shadowy Other against which an internal conflict can be played out; ordinary facts or events assume extraordinary interpretive possibilities. As an outer shell, the house duplicates the body as enclosure or limiting wall. The sense of body as "Other" of course has its roots in the forms of Protestant Christianity that so deeply inform the American imagination, beginning back with the Puritan injunctions to escape the temptations of the body into a spiritual realm.

As time goes on, the animation of the wallpaper increases in differentiation and depth. The woman can see, "where the sun is just so," a "strange, provoking, formless sort of figure that seems to skulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design" (8). Once she claims to herself the ability to see beyond surfaces, she is lost in a world of projective speculation. Yet her observation that this creature appears "when the sun is just so" seems a vestige of rational explanation, as though in some degree she recognizes the possibility that the phenomenon is an optical illusion.

The next stage in the woman's dementia is a perverse embracing of her confinement and the aspect of it she finds most repugnant: "I'm getting really fond of the room in spite of the wallpaper. Perhaps because of the wallpaper" (9). She moves from observation to involvement, accepting the wallpaper as a necessary evil in the way a person accepts an imperfect body or

some impediment that may, once accepted, become a source of positive possibility.

She begins to pay more acute attention thereafter to the patterns on the wallpaper, finding in them a source of occupation in her solitary confinement; though the patterns involve her in increasingly obsessive-compulsive behavior, they do provide some stimulation in an otherwise depleted environment. The patterns, she observes, "connect diagonally, and the sprawling outlines run off in great slanting waves of optic horror, like a lot of wallowing sea-weeds in full chase. The whole thing goes horizontally, too, at least it seems to, and I exhaust myself trying to distinguish the order of its going in that direction. . . . The interminable grotesque seems to form around a common center and rush off in headlong plunges of equal distraction" (10). Jung and others have established that psychotics tend to draw open-ended figures, not to enclose space—an interesting observation here, where the center the woman establishes in the pattern is not really a center of anything but an endless web of lines. There is no closure. Furthermore, the static pattern is here perceived as animated and active.

The next stage is secrecy. The woman assures herself, "There are things in that wallpaper that nobody knows about but me, or ever will" (11). With this statement, in which she invalidates any judgment others may pass on what she sees, she closes a door on the reality that could provide a check on her construction of a separate world. The relationship between the woman and the wallpaper thereby assumes a new dimension. The closed system is complete. There is no longer any desire to appeal to outside sources for confirmation of what she sees.

Her imaginary world begins to betray her, however. The satisfaction of her secret soon slips into irritation and then torment as she begins to find irregularities in the pattern, "a lack of sequence, a defiance of law, that is a constant irritant to a normal mind" (12). She describes the pattern as aggressive—"It slaps you in the face, knocks you down, and tramples upon you"—and these metaphors literalize themselves as she decides that the wallpaper is moving, sees a woman trapped behind it, and ultimately becomes obsessed with the project of freeing the woman. In the final scene her concern for the woman behind

the wallpaper has progressed from sympathy to empathy to complete identification and confusion of her self with the specter. As her husband opens the door to the locked room she turns and declares defiantly, "I've got out at last . . . in spite of you and Jane. And I've pulled off most of the paper, so you can't put me back!" (19).

This haunting story, now a standard reading in American literature and women's studies courses, encapsulates in intensely dramatic form some of the convictions Gilman elaborated at much greater length in her book The Home , a methodical and lucid inquiry into what she calls "domestic mythology" in the United States and its consequences.[4] Applying the principles of social Darwinism popular at the time, she claims that the home is "the least evolved of all our institutions." She poses the general questions of why it has been so resistant to progress and what is happening to women enclosed in their homes and unable to participate in the widening spheres of social action and the march of progress. Starting with chapters on "The Evolution of the Home" and "Domestic Mythology," she attempts to trace the development of the idea of home and practices of home life from their primitive beginnings in caves to their varied forms in contemporary civilized societies, the point being that with respect to the role of women they not only have not progressed toward enlightenment but have in fact been a regressive and repressive institution. "What is a home?" she asks, in much the same spirit as Thoreau's "What is a house?"

Beginning with a carefully scientific definition of the home as "the shelter of the family, of the group organised for the purposes of reproduction," likening the home to a beehive, which "is as much a home as any human dwelling place—even more, perhaps"—she claims, "we may study the evolution of the home precisely as we study that of any other form of life" (23). The study that follows courageously undertakes to identify as myths and fallacies some of the most widely held notions and practices about home, women, and family in her generation. Slaughtering one sacred cow after another, she claims that women's unspecialized work is not only demeaning but holds up the general progress of humankind; that childrearing would be more effective when carried out communally in healthy environments

supervised by trained experts than when given over to the care of unskilled and often ill-adapted mothers; that cooking likewise might better be done by trained cooks and provided as a paid public service, leaving women free to follow other talents; and that "the effect of home life on women seems to be more injurious in proportion to their social development" (74). In contrast to these ideals she characterizes "normal" Victorian home life as "morbid, disproportioned, [and] overgrown" (178).

Gilman's analysis reaches a high pitch of argument in the chapter entitled "The Lady of the House," which may serve as an explicatory key to "The Yellow Wallpaper" or, conversely, to which the story provides a chillingly precise illustration. What, she inquires, has the "age-long" tradition of housebound life done to woman, "the mother and moulder of human character; what sort of lady is the product of the house?" (220). Physically, she is whiter, softer, and frailer than her ancestors, and Gilman wastes no words taking to task the fashions that glorify these conditions that betoken morbidity and weakness. But the list of mental deformities resulting from chronic domestic isolation is much more troubling: first "a sort of mental myopia" developed from "looking always at things too near"—a dangerous lack of perspective that gradually stunts a woman's ability to make any distinctions or judgments about public affairs. This small-mindendness often results in eccentricity and "a tendency to monomania" and other "pathological" conditions. Gilman looks at the profusion of fancywork and other domestic forms of expression and sees in them not a delicate craft equal in dignity to public art forms but "a senseless profusion of expression" betokening the desperate efforts of a trapped creature deprived of air and exercise and full use of her powers to put her energies to some use: "There is no pathos, but rather a repulsive horror in the mass of freakish ornament on walls, floors, chairs, and tables, on specially contrived articles of furniture, on her own body and the helpless bodies of her little ones, which marks the unhealthy riot of expression of the overfed and underworked lady of the house" (220).

She concludes her argument with a plea for the conditions that allow health and happiness in any sentient creature: legiti-

mate exercise of mental and physical powers, some public intercourse, and freedom to follow the vocational longings that demand expression. And she issues a warning: "The widespread nervous disorders among our leisure-class women are mainly traceable to this unchanging mould, which presses ever more cruelly upon the growing life" (225).

In her autobiography Gilman portrays her own mother as "the most passionately domestic of home-worshiping housewives" and devotes several pages to an ambivalent tribute to her mother's homely virtues.[5] Compelled by a financially and emotionally unstable marriage to move nineteen times in eighteen years, Mary Westcott Perkins endured disruption by clinging to a vision of motherhood and homemaking that her children experienced as smothering. At a fairly early age, Gilman claims, she and her brother both outgrew their mother, who, a paragon of the womanly virtues touted in her generation, was never allowed a fully adult life. For Gilman herself that "fully adult life" was won at a high price. This life consisted of broadening the notions that bound women to their place; understanding these ideas in a wide, global context; and teaching women that the vocation of motherhood could be understood as a call to serve the "growth" of consciousness (one of her favorite concepts) and that "home" could and should be preeminently a place where the seeds of social reform and enlightenment were planted.

The summary chapter of her autobiography, in which she looks back over the changes she has witnessed in nearly seventy-five years, is entitled "Home." In it she reflects on the social and philosophical changes of attitude that have led to what she hopefully calls "the woman's century." She prophesies "more and more professional women, who will marry and have families and will not be house servants, for nothing; and less and less obtainable service, with the sacrifice of the wife and mother to that primal altar, the cook-stove" (321). Gilman's socialist vision remains a challenge to society to develop models of household economy and family life that provide both loving, intelligent nurturing and an atmosphere in which individuals can find and fulfill their separate vocations and perform the "one predominant duty," which is "to find one's work and do it" (335).