4—

The Portrait of a Lady:

More Stately Mansions

Much has been written about James's houses and with good reason: of all American novels, his are the most explicitly and consistently architectural in conception and subject.[1] Understanding things "in relation," which he claims is the only way we can understand them, means understanding that all the actual structures we erect around ourselves reflect the fundamental relations we establish as parameters for living together. This includes, of course, the "houses of fiction" that dot the cultural landscape. Conversely, if fiction is like a house, so a house is a kind of fiction: a text, a story, a system of signs, a way of organizing relations into comprehensible patterns. Curtis Dahl, in a brief study of James's uses of architecture, observes about his architectural representations that they are minutely accurate as a record of actual buildings or types of buildings reflecting the architectural fashions of the time; that he regularly uses architecture, city streets, and other physical structures to reflect the attributes of individual characters and of cultures and to serve as indices of cultural differences; and that buildings become a "language through which James expresses American as opposed to British values, the New World as opposed to the Old," thus serving as a primary device for introducing the comparisons that constitute his persistent "international theme."[2]

These observations are clearly borne out in The Portrait of a Lady , whose houses present a study in multiple contrasts and conflicts among cultures, personalities, and styles of life.[3] They are based on actual prototypes, some with considerable specificity, such as Osmond's Florentine villa, which, according to R. W. Stallman, is an exact replica of the Villa Mercedes, which James visited in 1869; his descriptions of known houses are so accurate and at the same time so thoroughly elaborated as symbolic objects that, Stallman argues, the "illuminating point" is simply

how James manages the conversion of the literal to the symbolic.[4] Each of his houses reflects the moral attitudes, political orthodoxies, structures of social intercourse, and notions of privacy and public life that most define the differences among cultures.

It is in the preface to The Portrait of a Lady that James first articulates the famous conceit linking houses and novels that he attributes to Turgenev but that has since become a touchstone for understanding his own theory of fiction. Ellen Eve Frank imagines James's "finely wrought prefaces" themselves as "the house that James built to house his 'houses of fiction.'" She goes on to observe:

And what might seem to be an infinite regress of houses within houses . . . is in fact finite, ordered according to a complicated spatial and temporal scheme. The prefaces represent the outermost house enclosing the remembered houses in which James wrote his fictions; James then images these fictions as houses which enclose still smaller ones, either those real or imaginary structures which locate and set action or those house-similes which represent the minds and psychological conditions of characters.[5]

About the design of these houses, James himself observes, "The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million" (ix). He describes Isabel Archer as a "single small cornerstone" on which is erected "the large building of The Portrait of a Lady. " He goes on to reflect about the novel, "It came to be a square and spacious house—or has at least seemed so to me in this going over it again; but, such as it is, it had to be put up round my young woman while she stood there in perfect isolation" (xi).

Here, in perhaps its most famous American formulation, is the ubiquitous notion of the house as an extension or shell of the self that "grows up" around the inhabitant and participates in his or her attributes. In the same way, the novel is an extension of character—an unfolding of the logic of character—and all the "matter" of the novel—plot, scene, and point of view—flow ineluctably from that logic. Because Isabel cannot be understood "in perfect isolation" but only "in relation," the novelist as a student of character must put her in a variety of

changing relations in order to reveal the manifold aspects of her character that are the story's raison d'être. Each house Isabel enters in this novel becomes a "frame" for a portrait of her, and within each frame new aspects of character emerge in the complex image of this girl-woman. Isabel adapts to each house in ways that change both her and our perspectives on the moral attitudes that define her. This process of adaptation may be understood, moreover, as something peculiarly female if we believe Madame Merle's rather bitter observation that "a woman . . . has no natural place anywhere" (196) and is therefore of necessity more readily adaptive than a man to the places in which she finds herself.

Here, as in so many novels about women adapting to the places in which they find themselves, Isabel's progression is toward increasing physical and social confinement and deepening moral conflict, even as her worldly vision widens and her capacity for "fine perception" is further refined. The houses she moves through on her way from Albany to Italy are all in some measure dark, imprisoning, and restricting of freedom of movement and imagination: the Albany house is closed off from the street it fronts; Gardencourt has numerous doors that close off private chambers to which she has no access and through which on several crucial occasions she "bursts" in impatience to force a direct encounter proscribed by tacit house rules; Lockleigh she perceives as a well-appointed, comfortable prison house surrounded by a moat; and Roccanera, Osmond's Roman palace, is "dungeonlike."[6] But where the darkness of the Albany house is a darkness of interiority, protection, and womblike insularity, the darkness of the Roman palace is something much more sinister. The American house, by Mrs. Touchett's assessment, is a "bad" house; the Italian house is "evil." Throughout the novel there are characters who play the parts of fairy godmothers or princes who offer to help Isabel escape these places. But not only does she refuse their aid; the escapes they offer portend their own kinds of imprisonment.[7] In the end, though she understands all too well the nature of the imprisonment to which she has condemned herself, she flees Caspar Goodwood's final attempt to lure her away from her disastrous home and marriage and flees from the garden where he has accosted her

into the house, behind a locked door—a move that signifies a closure many readers regard as tragic, though certainly it is no less ambiguous than the moment when Ibsen's Nora slams her husband's door behind her.

Like Hawthorne, James always envisions and depicts human action within frames and on stages: the garden, the courtyard, the parlor, the piazza, the balcony, the bedroom, are all confined settings that generate certain kinds of social intercourse and reveal certain aspects of the manners that to him are the ground of moral understanding. Like a cameraman, he situates the reader in changing relation to the characters by locating the reader's eye at a vantage point that itself is not neutral but that forces on the reader an uncomfortable awareness of his or her own privileged perspective. The operative assumption in James's scene-setting is fairly simple: people's behavior is keyed to place, and they seek the places that allow them to express certain aspects of their character. The locus of action limits and shapes behavior because civilized people do not violate the implicit dictates of setting—civilized behavior is appropriate to context. When actions are removed from one frame of reference to another, their meaning is altered. Such removal, or "reframing," is the essential means by which change of moral perspective occurs. Reframing wrenches things out of their conventional relations and reconfigures them, opening them to reevaluation and introducing the kind of moral ambiguity that James regards as a hallmark of true consciousness.

Interested in the same fundamental questions about the reciprocal influences between individual and environment as his transcendentalist predecessors, James poses them in a different set of terms, taking them out of a large metaphysical context and focusing on the forces of social and manufactured environment rather than of nature on human character. He writes about domestic behavior among domesticated people whose civilization and morality can rightly be understood only in terms of the structures they have erected around themselves and the way they live within those structures. In the case of Americans, the very idea of structure, convention, and orthodoxy seems to produce an uncomfortable apprehension in that they signify loss of freedom and the closing off of possibility.

The Portrait of a Lady is the novel that comes closest to providing a complete catalog of James's architectural devices. Houses in this novel provide detailed semiotic keys to the primary action—the education of Isabel Archer. Each house she enters changes her outlook, her behavior, her values, her status. It may be stretching a point to call The Portrait of a Lady a tragedy of homelessness; certainly there is no heroine in nineteenth-century fiction to whom more palatial doors are opened than to Isabel Archer. But what Isabel most poignantly and pointedly lacks is a real home and the particular kind of social and moral formation that comes from deep and prolonged engagement with a particular house on a particular spot of ground. She has not known the intimacies of ownership and the proprietary pride that teach a person how to negotiate with the material world, that provide a sense of style, and that furnish the imagination with the forms and shapes that define cultural sensibility. Like the elder Henry James, Isabel's father was, we are told, a large-minded, restless soul whose taste for change and extravagance of vision were matched by material extravagance yet who had provided his daughters with no anchor in the world but the ability to adapt to shifting circumstances. Some "harsh critics" in the novel went so far as to claim that "he had not even brought up his daughters. They had had no regular education and no permanent home; they had been at once spoiled and neglected," though for all that, Isabel's own sense of the matter was that her "opportunities had been large" (33, 34).

Her experience of the world has been eclectic, relatively autonomous, and free-form, but freedom from conventional restraints has deprived her of a real understanding of "forms" in the Jamesian sense—social structures and rituals that give shape to human relations and make art of life. She suffers, as Elizabeth Sabiston points out, from the "Emersonian illusion" that she can "build therefore [her] own world," and her story is a tale of the disillusionment of a transcendentalist romantic.[8] The theme that dominates James's major fiction—expatriation and displacement—can be understood altogether as an exploration of the consequences of naive rejection or ignorance of civilized forms.

As an expatriated American woman, none of the houses Isabel inhabits is hers in the deep sense of being home. In all of them she lives as a guest or stranger—even, and most pointedly, in her husband's. She has charm and intelligence but little of the savoir faire that enables an individual to prevail in the Darwinian struggle for social survival. She has ideas but no developed cultural context to put them in perspective. She has money that gives her entrée into society and the "best houses" but has no standards of judgment to help her gauge the values they embody and perpetuate. And the warning note in this jeremiad is that money and ideas without grounding in material culture are dangerous abstractions.

Isabel's education lacks, in short, what James would call "manners." And without manners, as he shows in some of his most memorable characters, high moral attitudes border on the ridiculous. Many of James's Americans do, for this reason, suffer from elements of the ridiculous; they are unsubtle, uncultured, simplistic, and naive, albeit honest, high-minded, and uncorrupted by the corrosive elements of civilized life. The most stolidly un-Europeanized Americans in this novel are, in a sense, buffoons: Caspar Goodwood, Isabel's literal-minded, forthright, upstanding, American suitor, and Henrietta Stackpole, eccentric lady journalist, represent the vulgarities of American character in their purest form. Henrietta and Caspar are unable to compromise, inured to subtlety, incapable of refinement, and entrenched in a way of thinking and seeing characterized by crude, unexamined moral categories untempered by worldly experience. They are the only characters not associated directly with houses—comic, unsubtle, and lacking in cultural insight, they reveal in higher relief some of the idiosyncrasies of Isabel's own character and the consequences of some of her own parochial attitudes. The independence of which they are all so proud entrenches them in a kind of parochialism and even vulgarity that result from an inability to come to terms with the compromises refinement entails. They are restless, mobile people who have, in a sense, "nowhere to lay their heads." They live in a world of abstractions, puritanically regarding the material world as separable from the world of ideas and attitudes.

Though Isabel shares these peculiarly American shortcomings, she is, unlike them, "educable." The Portrait of a Lady

could in fact be subtitled "The Education of Isabel Archer." Belatedly, and at great cost, she begins to learn what an individual can learn only by a fall into civilization and acclimation to its complex codes of behavior. The houses she enters become her schools. She brings into them fixed notions about life that are tempered and even undermined by the behavior enforced by the traditions and the architecture of these old homes where, as she romantically imagines, "things have happened."

The house that came closest to being a home in Isabel's childhood was her grandmother's converted duplex in Albany—a "large, square double house"—unpretentious, functional, and wholly without aesthetic distinction. It had been converted into one dwelling with a connecting "tunnel"—a place with a dark side and a light side, its shades pulled against the street it fronted, as stark, isolated, and inwardly turned as Isabel, who over the years grew accustomed to inhabiting its lowest and darkest corner, which was the library. The narrator points out that "the foundation of Isabel's knowledge" was laid in the library of this house, where she had plenty of "idleness," which she filled with wide-ranging, undirected reading in the best American autodidactic tradition. In James's universe, such random and unreferenced knowledge inevitably brings semitragic consequences.

There in the dark library Isabel's romantic fancies developed unchecked: from her nest she "had no wish to look out, for this would have interfered with her theory that there was a strange, unseen place on the other side—a place which became to the child's imagination, according to its different moods, a region of delight or of terror."[9] The image of this curious house, bicameral, androgynous, and even hermaphroditic, invites allegory in the same playful way as does Hawthorne's House of the Seven Gables. The narrator suggestively compares the converted duplex with the "Dutch House" across the street, which has been turned into a school, a fact that reinforces the impression of the neighborhood as one of odd, multipurpose structures, singular and indefinite in their character.

Mrs. Touchett, visiting Isabel in Albany some time after her parents' deaths, questions her about the value of her grandmother's house, but Isabel does not know how much it is worth—has never, in fact, considered the question. Here and

throughout the book the idealistic insularity of Isabel's upbringing is suggested by her ignorance of the commercial value of things and even of her own person—an ignorance that, combined with an inherited fortune, turns out to be a tragic flaw. The contrast between Mrs. Touchett's unsentimental worldliness and Isabel's naïveté is evident the moment the aunt enters the house: Isabel, not knowing her aunt, mistakenly assumes from her manner of scrutiny that she has come to buy the house. Mrs. Touchett compares it unfavorably to houses in Florence, some of which, her own included, are ancient palaces, rich with history and aesthetic appeal. This one, she observes, is simply "bourgeois," and she suggests that Isabel might appropriately convert it into shops rather than sell it, a practical solution that puts Isabel in a predicament similar to that of Hepzibah Pyncheon: idealism, sentimentality, and family pride compete with expediency. The tension between the commercial and the symbolic remains thematic throughout the story, reintroduced in a different vein as each of the characters considers the related matters of property and propriety.

We are given our basic information about Isabel's character in the context of this curious American house, an architectural joke compared with the English and Italian mansions to which Isabel and we are subsequently removed. Her own high seriousness is slightly ironized by it; her situation, if not her person, has distinctly comic overtones. As Mrs. Touchett describes Isabel to Palph, "I found her in an old house at Albany, sitting in a dreary room on a rainy day, reading a heavy book and boring herself to death" (42–43). Isabel's inclination to solitude and introspection is conveyed by a simple account of her habits: she habitually situates herself in a remote corner to read, or when she is restless and agitated, she "mov[es] about the room, and from one room to another, preferring the places where the vague lamplight expired" (32). She acts out her inner states by occupying a place indicative of her state of mind, generally introspective, solitary, and somewhat standoffish. (By contrast, when her dogged suitor, Caspar Goodwood, enters, he stands right next to the lamp, being a man who is upright, forthright, and literal.) Isabel's aunt Varian, the only other adult involved in her American upbringing, is introduced briefly to provide an

added bit of perspective on the cultural hodgepodge in which Isabel has been raised. Her aunt's large house, like her grandmother's, is "bourgeois" and tasteless and bespeaks an unguided, profligate affluence marked by its pointless eclecticism. It was "remarkable for its assortment of mosaic tables and decorated ceilings, was unfurnished with a library and in the way of printed volumes contained nothing but half a dozen novels in paper on a shelf in the apartment of one of the Miss Varians" (50). The "novels in paper" of course mirror the same questionable taste the house itself reflects, with, no doubt, a comparable assortment of unspecified decorations.[10]

This environment has formed Isabel and is reflected in her character with all its flaws but also with a kind of idiosyncratic charm. Like the house she loved as a child, she is two-sided, ambivalent, practical, unpretentious, introspective, and yet sociable, freestanding, and unadorned. Isabel's mind is described as a place she inhabits in the same restless way as she occupies her favorite rooms: "Her imagination was by habit ridiculously active: when the door was not open it jumped out the window. She was not accustomed to keep it behind bolts" (32). Here again, analogies between the body or the mind and the dwelling arise, opening the questions of value in a new vein because the measure of a young woman's value is also a central issue. Isabel's cousin Ralph later describes her in similarly architectural terms: "'The key of a beautiful edifice is thrust into my hand, and I'm told to walk in and admire.' . . . He surveyed the edifice from the outside and admired it greatly; he looked in at the windows and received an impression of proportions equally fair. But he felt that he saw it only by glimpses and that he had not yet stood under the roof. The door was fastened, and though he had keys in his pocket he had a conviction that none of them would fit" (63). Ralph's observations here reflect not only his relationship to Isabel but the readers' as well and not only our relationship to her but to the "beautiful edifice" of the text—the house of fiction—into whose thousand windows we look and try by multiple perspectives to grasp a sense of the whole.[11]

The extreme contrasts between old- and new-world structures and attitudes are reiterated in the polarities that draw Ralph and Isabel into fascinated intimacy. Both uprooted chil-

dren of unorthodox parents, products of American mobility, schooled to ambiguous adaptations, they represent opposite effects of deracination. Where she is an impressive edifice of fair proportions, he is a crumbling ruin—his health failing, his scope of action diminishing, his body wracked prematurely into old age. "His serenity," the narrator observes, "was but the array of wild flowers niched in his ruin" (41). For all its historic nobility and grace, the home Ralph shares with his father, Isabel's uncle, at Gardencourt is also a place of diminishment—a mere reminder of richer, livelier times. Both its inhabitants are infirm, and its mistress is gone much of the time, her marriage to Mr. Touchett a barely preserved formality. The house's long galleries, music rooms, and parlors are in minimal use. Isabel enters this house with youthful awe, the ambivalent reverence of the new world for the old, and slightly comic romantic fancies. Taking literally Ralph's ironic allusion to the "ghosts" that inhabit the old house, she asks, "You do see them then? You ought to in this romantic old house." Ralph meets her romanticism with the stark realism born of experience and disillusionment: "It's not a romantic old house. . . . You'll be disappointed if you count on that. It's a dismally prosaic one; there's no romance here but what you may have brought with you" (46–47).

Unlike his father, Ralph's acclimation to English life has been a process of steady disillusionment, chronic displacement, and deepening irony. His is the prophetic perspective of the marginalized; not only his expatriation but also his sickness places him at that margin of experience where action is replaced by observation with some claim to "objectivity." Isabel's perspective, however, is colored deeply by the desire that is the root of all idealism:

Her uncle's house seemed a picture made real; no refinement of the agreeable was lost upon Isabel; the rich perfection of Gardencourt at once revealed a world and gratified a need. The large, low rooms, with brown ceilings and dusky corners, the deep embrasures and curious casements, the quiet light on dark, polished panels, the deep greenness outside, that seemed always peeping in, the sense of well-ordered privacy in the centre of a 'property'—a place where sounds were felicitously accidental, where the tread was muffled by the earth itself and in the thick mild air all friction dropped

out of contact and all shrillness out of talk—these things were much to the taste of our young lady, whose taste played a considerable part in her emotions. (54–55)

And, it might be added, her emotions played a considerable part in her taste—an attribute that when it is not formed by the external pressures of a highly articulated culture grows out of the mixed soil of personal fancy. So Isabel's appreciation of Gardencourt has a poignant quality of longing for the quality missing from her own milieu—the quality that James himself so missed in the United States that it caused him to regard his native country a cultural desert. The reader's perspective on Gardencourt is a triangulation of Ralph's and Isabel's vision that results in what for American readers must be a familiar ambivalence toward English culture, history, and manners.

The novel opens on the lawn of the old mansion, whose symmetries, spacious grace, and noble past suggest a host of clichés about what is best and most lasting in English culture and offer a stark contrast to the parochialism of the Albany house, subsequently introduced in flashback. The English house has a long history—the early Tudor, built under Edward the Sixth, had even, it was said, extended hospitality to Elizabeth I for a night. It was "a good deal bruised and defaced in Cromwell's wars, and then, under the Restoration, repaired and much enlarged" (6). And now, "after having been remodeled and disfigured in the eighteenth century," it has passed

into the careful keeping of a shrewd American banker, who had bought it originally because . . . it was offered at a great bargain: bought it with much grumbling at its ugliness, its antiquity, its incommodity, and who now, at the end of twenty years, had become conscious of a real aesthetic passion for it, so that he knew all its points and would tell you just where to stand to see them in combination and just the hour when the shadows of its various protuberances—which fell so softly on the warm, weary brickwork—were of the right measure. (6)

Here, in brief, is a microcosm of English history culminating in the return of the American to English soil, able by dint of money to buy back some of the birthright he might have had on

other terms. The costs of the expatriate's reassimilation are gradual compromise, humility, and the loss of vitality suggested in the image of the colonial rebel become new-world entrepreneur. Mr. Touchett's house changes him. Living in it, he develops a taste for English life, an appreciation for English style, and the kind of intimacy only ownership makes possible. The house's long galleries and private apartments bespeak a way of life in which public face and unseen interiors preserve the sorts of distinctions that arise in a culture unencumbered with egalitarian pretensions.

Once again James juxtaposes the description of the house with a detailed portrait of Mr. Touchett's "physiognomy," a parallel reiterated for each of the major characters that is similar in its allegorical explicitness to Hawthorne's elaborate anatomical analogies. Mr. Touchett's is an "American physiognomy," though tempered by thirty years of English life:

He had a narrow, clean-shaven face, with features evenly distributed and an expression of placid acuteness. It was evidently a face in which the range of representation was not large, so that the air of contented shrewdness was all the more of a merit. It seemed to tell that he had been successful in life, yet it seemed to tell also that his success had not been exclusive and invidious, but had had much of the inoffensiveness of failure. He had certainly had a great experience of men, but there was an almost rustic simplicity in the faint smile that played upon his lean, spacious cheek and lighted up his humorous eye. (7)

The man, like the house, is a repository of a history now inscribed on his features. His face bespeaks a rich store of experience and gives the impression, like his house, of having survived eras of both prosperity and scarcity into a comfortable and commodious old age, his powers compromised but still acute.

The opening scene of the novel takes place on the lawn of Gardencourt where old Mr. Touchett, his son, and his neighbor are taking tea in the afternoon sunlight. We see first the shadows on the lawn, "straight and angular," of the three men gathered there—the younger two pacing, the old man "rest[ing] his eyes on the rich red front of his dwelling," which is, the narra-

tor interposes, "the most characteristic object in the peculiarly English picture I have attempted to sketch." Standing on a low hill above the Thames, "some forty miles from London . . . a long gabled front of red brick, with the complexion of which time and the weather had played all sorts of pictorial tricks, only, however, to improve and refine it, presented to the lawn its patches of ivy, its clustered chimneys, its windows smothered in creepers" (6). The narrator continues with an account of the house's significant history and returns to the present with the observation that "privacy here reigned supreme, and the wide carpet of turf that covered the level hill-top seemed but the extension of a luxurious interior. The great still oaks and beeches flung down a shade as dense as that of velvet curtains; and the place was furnished, like a room, with cushioned seats, with rich-colored rugs, with the books and papers that lay upon the grass" (6–7).

As in so many romantic representations of houses and homes, the boundaries between inside and outside are blurred, but here it is manufacture, rather than nature, that seems to be the imperializing force; domestication begins to overtake the natural environment rather than succumbing to the slow, ineluctable forces of nature. This, in fact, may be that quality that is open-endedly designated as "characteristically English"—the imperial habit of mind that civilizes whatever it touches on its own sedate terms.

Into this scene of masculine domesticity enters Isabel, framed in the "ample doorway" of the house looking outwardly on its owners in another odd reversal of the logic of hospitality. It is the little dog, rather than any of the men, who sees her first—a detail that underscores the introduction of something intuitive and spontaneous into a markedly ordered and ritualized scene. She is, Ralph notices on first glance, "bareheaded, as if she were staying in the house"—a fact that perplexes him because he is unaccustomed to visitors and does not recognize his cousin anymore than she, earlier, recognized her aunt on her invasion of the Albany house. Like the aunt, Isabel in turn appears in some way already to have taken possession of the place, an entitled intruder whose scant observation of social forms seems to grant her entitlement even before it is established that she is family. In

fact, she seems strangely to take possession of the whole scene by dint of her innocence of social constraints; she handles the dog with such familiarity that Ralph cedes ownership on the spot, to which Isabel responds, "Couldn't we share him?"

Her ignorance of custom and propriety continues to surface in a series of comic details: she responds to Ralph's apology for her not having been "received" with the reassurance that "we were received. . . . There were about a dozen servants in the hall. And there was an old woman curtsying at the gate" (18). Introduced to the neighbor, Lord Warburton, she cries, "Oh, I hoped there would be a lord; it's just like a novel!" And finally, looking around, she says with childlike pleasure, "I've never seen anything so beautiful as this." To which her uncle replies, "But you're very beautiful yourself." a remark that goes beyond polite rejoinder to hint at the romantic projection that infuses Isabel's vision (17, 19).

Isabel turns away from Mr. Touchett's compliment on her beauty to ask about the house. The house is an acceptable medium through which personal relations can be established and values described and discussed. Ralph compares it to others of its kind, diminishing its importance as a specimen, but Mr. Touchett defends it. Lord Warburton enters the contest, comparing it to his own Tudor: "I've got a very good one; I think in some respects it's rather better," adding, "I should like very much to show it to you" (19). There is a kind of comic chivalry in these introductory gambits in which houses become a measure of men and a kind of collateral offered in exchange for the lady's attentions. Isabel, however, refuses to play her part in the contest. "I don't know," she says, "I can't judge." And, indeed, she speaks a literal truth: she has no criteria for judging the quality of the estates offered for her consideration. In the comparisons she is asked to make lies the beginning of her cultural education. Ralph shows her his art gallery; Lord Warburton, his moat. She receives a series of impressions from her hosts that seem increasingly to call on her for some judgment—ultimately, of course, for a decision about marriage or what way of life to adopt for herself. With only the stark American home as a basis of comparison, her judgments must proceed from impression and intuition rather than cultivation, and the dan-

gers as well as the strengths of such an approach to aesthetic discernment become more painfully apparent as the novel progresses.

One amusing measure of Isabel's heightening sensitivities to her new environment is the intrusion of her breezy American friend, Henrietta Stackpole. When this lady journalist first arrives unbidden at Gardencourt, her initial reactions are similar to Isabel's in their openmouthed naïveté and general awe of things English. But Henrietta's utterly utilitarian impulse to seize hold of these impressions and turn them to commercial profit bespeaks an Americanness distinguished from Isabel's in its crassness. What in Isabel is character appears in Henrietta as caricature. She decides on the spot to write a piece for her newspaper called "English Tudors—Glimpses of Gardencourt." Isabel forbids her to do so, pointing out that it would be a terrible breach of hospitality to subject the old place to the indiscriminate curiosities of the public. The journalist complies reluctantly, unconvinced that there is any point to such proprieties. Henrietta throws the issue of value into high relief by occupying an extreme end of the cultural spectrum James is drawing in this novel. Her vision is entirely utilitarian, parochial, and infused with the enthusiasms of the uninformed. Her insatiable curiosity is appealing in its childlikeness but counterbalanced and tainted by a tendency to pass judgment on everything she sees according to her own narrow criteria. She storms Europe as an entrepreneur of "culture," seeking ways to package and export it for easy consumption by untraveled Americans hoping to reinforce their romantic condescensions toward all things European. In every house she enters she is an intruder, albeit on most occasions an amusing one—but ironically it is the invulnerability her insensitivity affords that preserves her from a fate like Isabel's—enmeshment in a system she is not equipped to navigate. Henrietta's love affair with Europe and eventually with a European is an American comedy of adoption rather than assimilation and only serves to deepen the tragedy of Isabel's awakening.

That awakening is mediated first by her cousin, whose passionate but disinterested tutoring turns out to be the most genuine connection Isabel makes, and second by Lord Warburton,

whose eagerness to initiate her is equally passionate and not at all disinterested. To accomplish this, he invites her to his local home—one of many in his possession. Another mansion that could be regarded as "characteristically English," it differs from Gardencourt in that it is inherited property, ancient, with the historical integrity of continuous family ownership, suited less to the immediate needs of its modern inhabitants than to the visible preservation of the past in its drafty halls and anachronistic moat. Lord Warburton himself, being a modern gentleman, treats this monument lightly, eventually offering to abandon it altogether and find a new dwelling more to Isabel's liking if she will marry hum, but finds that such disclaiming is no more easily accomplished than giving up his seat in Parliament. The burden of the past remains with him in his title as in his property, and for all his modernized, democratized attitudes, he cannot avoid assuming it.

When Isabel visits Lord Warburton's "ancient house" with its "vast drawing room," her impressions are ambiguous. She finds that "within, it had been a good deal modernized—some of its best points had lost their purity; but as they saw it from the gardens, a stout grey pile, of the softest, deepest, most weather-fretted hue, rising from a broad, still moat, it affected the young visitor as a castle in a legend" (78). Both her nostalgia for lost purity and her taste for romance enhance the appeal of the castle and its youthful master. The latter is described as a "remarkably well-made man of five-and-thirty with a face as English as that of the old gentleman [Touchett] . . . a noticeably handsome face, fresh-coloured, fair and frank, with firm, straight features, a lively grey eye and the rich adornment of a chestnut beard." He has, we are further informed, "the air of a happy temperament fertilized by a high civilization" (7–8).

Yet when this flower of English culture comes to propose to her, something keeps Isabel from succumbing to these allurements. Though she realizes that "her situation was one which a few weeks ago she would have deemed deeply romantic: the park of an old English country house, with the foreground embellished by a 'great' (as she supposed) nobleman in the act of making love to a young lady" (104), she clings to her notion of independence unpersuaded by either property or prestige,

measuring the material prosperity offered her against a rather vague ideal of independence and choosing the latter as the "higher" value. After Isabel's refusal and subsequent reluctant agreement to think it over, Lord Warburton adds, by way of inducing her further:

There's one thing more. . . . You know, if you don't like Lockleigh—if you think it's damp or anything of that sort—you need never go within fifty miles of it. It's not damp, by the way; I've had the house thoroughly examined; it's perfectly safe and right. But if you shouldn't fancy it you needn't dream of living in it. There's no difficulty whatever about that; there are plenty of houses. I thought I'd just mention it; some people don't like a moat, you know. Good-bye.

"I adore a moat," said Isabel. "Good-bye." (110)

This touching appeal epitomizes the fundamental differences between the two; Warburton, living in a culture where money and property are neither righteously understated nor romanticized but do figure as a legitimate currency in the business of marriage, can hardly imagine Isabel's grounds for refusal. To give up what he offers on the strength of an untried ideal is beyond his reckoning. Nor does Isabel herself fully understand her hesitation, except for a feeling of resistance to the foreignness and romance of the situation she confronts. He even offers to "furbish up" England if it will suit her better to stay there, and her reply again baffles him: "Oh, don't furbish it, Lord Warburton; leave it alone. I like it this way" (108). But liking it does not suffice, and Isabel is unable to say exactly what would. His observation that her uncle would probably advise her to marry in her own country simply evokes a perverse response that the old man seems to have been happy in England.

When Isabel talks over Warburton's proposal with her uncle, he comments reservedly that England is rather crowded, though he adds that doubtless "there's room for charming young ladies everywhere." Isabel replies, "'There seems to have been room here for you.'" Mr. Touchett answers with a "shrewd, conscious smile," "'There's room everywhere, my dear, if you'll pay for it. I sometimes think I've paid too much for this. Perhaps you also might have to pay too much'" (114). It

is a warning against the costs of expatriation and, perhaps, against the loss of what freedom might be enjoyed by a woman—certainly greater in the United States than in Europe. Both he and Ralph recognize that Isabel is ill-equipped to devise the strategies by which European women must maintain their semblance of power, and both try, in their way, to arm and empower her and protect her from the consequences of her own innocence. Ralph gives her advice and exposure to culture, training her eye and mind to habits of tasteful discrimination that might help her discern vulgarity even in its more camouflaged forms. Mr. Touchett gives her money, which, however, rather than empowering her heightens her vulnerability because it opens doors to her that begin to close behind her once she has passed through, leaving her struggling for firm footing on the slippery moral ground of polite society.

Isabel's real initiation, however, and the fatal moment in her European education, comes not from any of the suitors or protectors, or the houses that reveal so much to her about their modi vivendi, but rather from a critical conversation with Madame Merle. Another deracinated and in some senses homeless American woman, Isabel's ironic and even tragic counterpart, it is Madame Merle who imparts to her naive visitor what worldly wisdom she must have to survive. Occupying a position on the social scale that precludes her working, Madame Merle wanders about Europe from one hospitable home to another, keeping an apartment in Rome "which often stood empty," merely as a place to alight between journeys.

A centerpiece and transition point in the book and in Isabel's ill-fated European career is a conversation with Mme. Merle in which the older woman undertakes to educate Isabel in the moral and practical significance of houses in particular and material culture in general. Mme. Merle "talked of Florence, where Mr. Osmond lived and where Mrs. Touchett occupied a medieval palace; she talked of Rome, where she herself had a little pied-a-terre and some rather good old damask" (197), and they talk about suitors, which leads Isabel to give a reluctant account of the untranslatable qualities of Caspar Goodwood. If her suitor was such a paragon, Mme. Merle asks her, why did she not fly with him to his castle in the Apennines?

He has no castle in the Apennines.

What has he? An ugly brick house in Fortieth Street? Don't tell me that; I refuse to recognize that as an ideal.

"I don't care anything about his house," said Isabel.

"That's very crude of you. When you've lived as long as I you'll see that every human being has his shell and that you must take the shell into account. By the shell I mean the whole envelope of circumstances. There's no such thing as an isolated man or woman; we're each of us made up of some cluster of appurtenances. What shall we call our "self"? Where does it begin? where does it end? It overflows into everything that belongs to us—and then it flows back again. I know a large part of myself is in the clothes I choose to wear. I've a great respect for things ! One's self—for other people—is one's expression of one's self; and one's house, one's furniture, one's garments, the books one reads, the company one keeps—these things are all expressive. (201)

Ironically enough, this little defense of practical materialism is sound transcendental doctrine. Thoreau himself would not dispute the point, though the rhetorical purposes to which it is put would deeply offend that puritanical champion of simplicity. And here in a clever little sermon on good taste and good manners is encapsulated the great paradox that baffles Isabel's own puritanical habit of mind. Suddenly the high-minded idealism that claims not to care about a man's house looks simply juvenile, simplistic, and self-righteous in this new light. Moreover, as one critic has pointed out, Isabel herself has been seeing and judging people in terms of their material environments ever since coming to Europe.[12] She is brought up short against her own internal contradictions; she is not above the allure and enjoyment of material culture, yet she is constrained not to admit its fundamental importance in the economy of human intercourse and particularly in the business of marriage. To acknowledge the economic factor in so intimate and spiritual a relation would be to sacrifice a basic doctrine of the metaphysical individualism on which her whole sense of herself is built. And to be called on to understand the self in so complex a web of relations—defined by the pressures of the marketplace and the shifting standards of taste—threatens the whole monolithic structure of Isabel's notions of free will and integrity. She

cannot accept the implications of this short foray into social semiotics and so resorts to simple denial:

I don't agree with you. I think just the other way. I don't know whether I succeed in expressing myself, but I know that nothing else expresses me. Nothing that belongs to me is any measure of me; everything's on the contrary a limit, a barrier, and a perfectly arbitrary one. Certainly the clothes which, as you say, I choose to wear, don't express me; and heaven forbid they should! . . . My clothes may express the dressmaker, but they don't express me. To begin with it's not my own choice that I wear them; they're imposed upon me by society. (201–202)

Mme. Merle's rejoinder terminates the discussion without resolution: "Should you prefer to go without them?" Thoreau's admonition to beware any enterprise requiring new clothes resonates in Isabel's defiant and radical declaration of independence from the imposed structures and fashions of society, as does the far older reminder to look on the unclothed lilies of the field as models of the purest kind of life. Moreover, there is in Isabel's words a poignant recognition that the structures and designs of public life in fact have little to do with the actual lives of women. Yet her uncompromising attitude toward the world of material structures and monetary measures falls short of the heroic and borders on intellectual self-indulgence. Madame Merle has known want of a kind that is foreign to Isabel and so realizes that morality and manners both begin in recognizing what is involved in the business of survival—a business in which the material immediacies of everyday life take precedence over the luxury of ideas and ideals.

Seeming at some points to be Isabel's opposite, Mme. Merle is what Isabel might well become under the same set of influences and constraints: wily, worldly, and well schooled by necessity in the art of compromise. Her metaphysics is inseparable from social reality, and in this encounter romantic succumbs to realist with several quick turns of the Jamesian screw. Her sensitivity to the nuances of appearances, though an acquired strategy, casts a harsh light on the "honesty" of Henrietta's blunt, judgmental assessments of things ("Oh, yes; you can't tell me anything about Versailles" [219]). Like Hester Prynne before

them, the women in this novel live marginally with one foot outside the social structures erected to contain them: Mrs. Touchett maintaining her costly compromise with the terms of marriage; Mme. Merle devising highly refined forms of prostitution to ensure the maintenance of herself and her daughter; Henrietta trading respect and respectability for her cherished freedom of movement; and Isabel seeking a footing in a world for which her intellectual and moral isolationism have ill-prepared her.

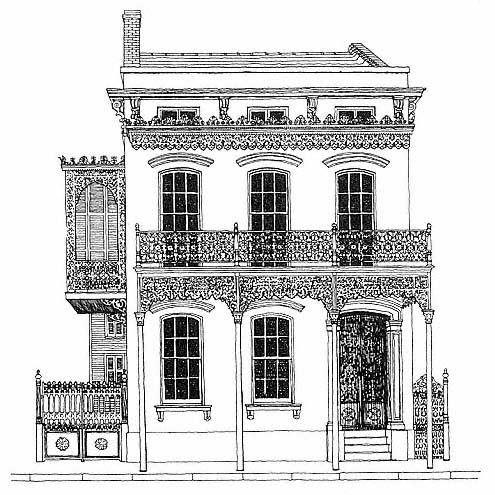

It is, of course, in Gilbert Osmond's labyrinthine villa (and in the duplicitous matrimonial contract that holds her there) that the innocent American becomes ensnared in a maze she cannot navigate. If the Americans in this novel suffer from a lack of refinement and civilized subtleties, the Italians (Gilbert, the complete convert to European aestheticism, among them) suffer from its opposite: mannered excesses ungrounded in moral vision, elaborate preservations of vacuous forms, effete tastes uninformed by humane values. In the marriage of Isabel and Osmond, substance without style confronts style without substance. The Florentine house in which Osmond courts Isabel and later the Roman palace into which she finds her way as bride and mistress stand at the other end of the aesthetic and moral spectrum from the large, square matriarchal house of her childhood. The former is sprawling, labyrinthine, full of hidden places and opaque fronts, its galleries and balconies dedicated to aesthetic pleasures and the sophistications of civilized pastimes. It is described as a "long, rather blank-looking structure," its front "pierced with a few windows in irregular relations" to which is attached "a stone bench lengthily adjusted to the base of the structure and useful as a lounging place to one or two persons wearing more or less of that air of undervalued merit which in Italy, for some reason or other, always gracefully invests anyone who confidently assumes a perfectly passive attitude" (226).

As with the English houses, parallels and analogies between the house and its owner are both stated and implied: words such as "lounging," "leaning," and "passive" recur with significant frequency in the descriptions of both the villa and its owner. The villa's almost absurdly spacious rooms have a

diminishing and somewhat dehumanizing effect on the inhabitants; the bedroom assigned to Osmond's young daughter, for instance, is "an immense chamber with a dark, heavily-timbered ceiling," in which the child appears "but a speck of humanity" (468). And the large antechamber entered from the staircase is a space "in which even Gilbert Osmond's rich devices had not been able to correct a look of rather grand nudity" (407).

Both house and master have something snakelike, secretive, and inscrutable about them; neither is self-revealing or frank; and there is in both an alarming "blankness" or emptiness behind an opulent facade that Isabel fatally mistakes for mystery:

This antique, solid, weather-worn, yet imposing front had a somewhat incommunicative character. It was the mask, not the face of the house. It had heavy lids, but no eyes; the house in reality looked another way—looked off behind, into splendid openness and the range of the afternoon light. . . . The parapet of the terrace was just the height to lean upon, and beneath it the ground declined into the vagueness of olive-crops and vineyards. . . . The windows of the ground floor, as you saw them from the piazza, were, in their noble proportions, extremely architectural; but their function seemed less to offer communication with the world than to defy the world to look in. They were massively crossbarred, and placed at such a height that curiosity, even on tiptoe, expired before it reached them. . . . It was . . . a seat of ease, indeed of luxury, telling of arrangements subtly studied and refinements frankly proclaimed, and containing a variety of those faded hangings of damask and tapestry, those chests and cabinets of carved and time-polished oak, those angular specimens of pictorial art in frames as pedantically primitive, those perverse-looking relics of medieval brass and pottery, of which Italy has long been the not-quite-exhausted storehouse. These things kept terms with articles of modern furniture in which large allowance had been made for a lounging generation; it was to be noticed that all the chairs were deep and well padded and that much space was occupied by a writing-table of which the ingenious perfection bore the stamp of London and the nineteenth century. There were books in profusion and magazines and newspapers, and a few small, odd, elaborate pictures, chiefly in water-colour. (226–227)

The elaborate, casual cosmopolitanism of this environment and its prohibitive privacy and ambiguous comforts are re-

flected in the person of Osmond, who is rendered almost as a caricature of the late-Renaissance courtier with his finely hewn face, beard "of which the only fault was just this effect of it running a trifle too much to points," and upwardly curled moustache, which "suggested that he was a gentleman who studied style." His "conscious, curious eyes, . . . eyes at once vague and penetrating, intelligent and hard, expressive of the observer as well as of the dreamer, would have assured you that he studied it [style] only within well-chosen limits, and that in so far as he sought it he found it" (228)—an observation that suggests an unsettling quality of calculation and self-preoccupation rather than the attentiveness they might be taken to connote. The narrator continues with a description that further complicates Osmond's ambiguity by belaboring the question of his origins in such a way as to suggest that cultural hybridization has denatured him and left him neither fish nor fowl—a composite social creation without the element of "soul" that derives from what Emerson would have called the "genius loci." The cumulative impression is that the whole is less than the sum of the parts:

You would have been at a loss to determine his original clime and country; he had none of the superficial signs that usually render the answer to this question an insipidly easy one. If he had English blood in his veins it had probably received some French or Italian commixture; but he suggested, fine gold coin as he was, no stamp nor emblem of the common mintage that provides for general circulation; he was the elegant complicated medal struck off for a special occasion. He had a light, lean, rather languid-looking figure, and was apparently neither tall nor short. He was dressed as a man dresses who takes little other trouble about it than to have no vulgar things. (228–229)

There is an implied equation here between the composite and the inauthentic, particularly as contrasted with earlier descriptions of "characteristically English" or "indisputably American" characters and houses. Among other evils Osmond comes to personify, he serves to illustrate from the outset the darker aspects of cultural eclecticism, which at its extreme becomes a betrayal of the self in which the center no longer holds—a sacrifice of the roots that drive deep into native soil in the

transplanting that leaves the individual only tenuously and superficially grounded in the adopted place. Like Isabel, and like the Touchetts, Osmond is a deracinated American, but his adaptations to Europe have reached a point of dubious returns in purging him altogether of national character. He has bought the forms of European life without any effort to claim or understand their moral or spiritual dimensions. Osmond raises in a far more sinister way the question Mr. Touchett ruefully pondered earlier—what are the costs of expatriation, and what are those elements of culture that cannot be acquired even with money, taste, and the will to adapt?

Osmond's Roman house is a house full of shadows, "a dark and massive structure," which Rosier, young suitor to Osmond's daughter, sees as a 'domestic fortress, . . . which smelt of historic deeds, of crime and craft and violence" (364). In this house Isabel learns a whole new pattern of existence. Prepared by Madame Merle, who, like Osmond, is a cultural chameleon, to doubt her own frames of reference, Isabel enters his house primed to accept as "higher" and more sophisticated the style of life it expresses and enforces. What she finds is that Osmond's mind, like his house, is "the house of darkness, the house of dumbness, the house of suffocation" (429). Her own progress in self-betrayal begins with her first visit to the house when Mme. Merle urges him as "cicerone" of his own "museum" to show Isabel his things, having elaborately complimented him on the one talent he seems not to have allowed to atrophy—the talent for tasteful acquisition: "Your rooms at least are perfect. I'm struck with that afresh whenever I come back; I know none better anywhere. You understand this sort of thing as nobody anywhere does. You've such adorable taste" (242).

Osmond demurs at first with a cynical self-assessment that has an odd character of honesty: "I'm sick of my adorable taste" (242). But he grudgingly consents to play his part in her scheme on learning that Isabel has seventy thousand pounds. The value of his "things" is immediately recast as they become means rather than ends—props in a melodrama of intrigue and seduction, in which he is the principal actor; his former mistress and consort, the director; and Isabel, the ingenue who does not

even recognize that she is on a stage, script in hand, her part assigned and her fate determined.

Vaguely aware of dangers she cannot name, Isabel visits her aunt, Mrs. Touchett, to solicit her opinion of Osmond and his entourage but finds no help in that quarter other than the blunt advice to "judge everyone and everything for yourself" (250). This is, of course, precisely what she has been trying to do, but she has lost her bearings and her standards of judgment. Mrs. Touchett, whose resistance to assimilation is as remarkable as Osmond's lack of definition, has no understanding of Isabel's susceptibility to the deceptions of her new environment. The older woman has taken Italy on her own terms. She lives in a "great house" with a "wide, monumental court," and "high, cool rooms where the carven rafters and pompous frescoes of the sixteenth century looked down on the familiar commodities of the age of advertisement." She has assessed the trade-offs involved in living in an old, cold, historic building, compensated for its darkness and inconvenience by reasonable rent and "a garden where nature itself looked as archaic as the rugged architecture of the palace and which cleared and scented the rooms for regular use." Isable, visiting there, regards it with nothing like this practicality: for her, "to live in such a place was . . . to hold to her ear all day a shell of the sea of the past. This vague eternal rumour kept her imagination awake" (247).

This same fatal tendency to romanticize what is ancient, foreign, and grand ultimately drives her decision to marry a man and enter a house that represent what she believes she ought to value—what seems the best of European culture, so superior in its artistic variety, historicity, and complex resonance to the straightforward simplicities of American life, which now appear, like the pitiful suitor, Caspr, and the eccentric Henrietta, narrow, parochial, uninspired, and impoverished. Too late Isabel finds herself entrapped in multiple structures that surround her like the "shells" Mme. Merle spoke of and that become her identity, burying what "self" remains under layers of clothing and obscuring accoutrements. "Her light step," the narrator ominously observes, "drew a mass of drapery behind it," and

her "intelligent head sustained a majesty of ornament. The free, keen girl had become quite another person." Ralph, reflecting sadly on the loss of Isabel's unspoiled youth as he sees her many months later, asks himself, "What did Isabel represent? . . . And he could only answer by saying that she represented Gilbert Osmond" (393). Osmond's house is a stage on which she finds herself condemned to play out a drama in which her role has been predetermined. The great rooms are designed for entertainment, and so she entertains. The role available to her is to be a decorative object to enhance his vast collection, and so she makes herself decorative.

Ralph's assessment of Osmond on this wistful visit is characteristically fair-minded, acute, and sharply aware of the messages embedded in the complex material environment the collector has created:

Osmond was in his element. . . . He always had an eye to effect, and his effects were deeply calculated. They were produced by no vulgar means, but the motive was as vulgar as the art was great. To surround his interior with a sort of invidious sanctity, to tantalize society with a sense of exclusion, to make people believe his house was different from every other, to impart to the face that he presented to the world a cold originality—this was the ingenious effort of the personage to whom isabel had attributed a superior morality. (394)

Ralph reflects with Thoreauvian scorn that far from being the master of the world he inhabits, Osmond is its "very humble servant," attentive constantly to the pose he has committed himself to maintaining, his ambition "not to please the world but to please himself by exciting the world's curiosity and then declining to maintain it" (394). The facades he erects deceive the gullible, and Isabel is the unhappiest among those deceived.

Osmond himself manages to maintain his self-respect by a combination of studied indifference and scorn for any but those under his control; after the marriage he systematically and mockingly dismisses each of Isabel's acquaintances, like old possessions no longer worth keeping, observing, "You're certainly not fortunate in your intimates; I wish you might make a new collection" (490). Ironically enough, his objections to them are

quite transparent projections leveled at the very qualities he might, had he any remaining capacity for self-scrutiny, recognize in himself. Thus, he takes umbrage at Lord Warburton's pragmatic consideration of Osmond's marriageable daughter, forgetting how utterly mercenary was his own wooing:

He comes and looks at one's daughter as if she were a suite of apartments; he tries the door-handles and looks out of the windows, raps on the walls and almost thinks he'll take the place. Will you be so good as to draw up a lease? Then, on the whole, he decides that the rooms are too small; he doesn't think he could live on a third floor; he must look out for a piano nobile. And he goes away after having got a month's lodging in the poor little apartment for nothing. (490)

The terms of Osmond's conceit comically reveal his own manner of assessing women in particular and human relations in general.

When, toward the end of the novel, Isabel returns to Garden-court to attend Ralph in his dying hours, the house becomes for her a measure of the distance she has traveled from the state of innocence in which she began her European life. Left alone in the drawing room to await a summons by new servants to whom she is a stranger, she wanders into the gallery where Ralph had once begun her aesthetic education:

Nothing was changed; she recognized everything she had seen years before; it might have been only yesterday she had stood there. She envied the security of valuable 'pieces' which change by no hair's breadth, only grow in value, while their owners lose inch by inch youth, happiness, beauty; and she became aware that she was walking about as her aunt had done on the day she had come to see her in Albany. She was changed enough since then—that had been the beginning. (569)

The constancy of objects restores to her a lost perspective. They force on her an appalling awareness of change and morbidity and a wistful memory of roads not taken. It occurs to her to wonder whether, had her aunt not propitiously appeared with her offer of European travel, she might have married the upright and honest Caspar Goodwood.

Fortuitously, of course, the object of this reverie soon appears, ghostlike, from her past, still in hapless pursuit, defying a marriage he considers illegitimate, to win back Isabel, now lost to him in so many senses. In the final chapter of the novel Caspar gives her one last chance to unseal her miserable fate. Finding her on the lawn of Gardencourt, he reiterates his plea with a passionate intensity that seems momentarily to redeem him from the ridiculous light in which he has consistently been cast and to ennoble him in his heroic persistence against odds he cannot possibly imagine. But his kiss—one of the most memorable moments of pure passion in all of James's writing—sends Isabel, after one brief moment of surrender, flying back to the house where, exactly reversing the historic gesture of Ibsen's Nora, she enters and closes the door behind her. As she does so, the magnitude of this rejection comes clear to her: "She had not known where to turn; but she knew now. There was a very straight path" (591). That "straight path" remains, however, unspecified. We might speculate that, like Mrs. Touchett and Madame Merle, Isabel has simply chosen a life of civilized compromise with a respectable, unsatisfying, but tolerable domesticity and that with the first light of morning she leaves England to return to Osmond's house to resume her position as its mistress, having now taken her own measure of its cost.