Act One—

A Poet, So What?

When did you first feel that you wanted to become a writer?

It was in college [Columbia University]. I began writing a lot of poetry. Mark Van Doren was one of my professors and he was the adviser to one of the literary quarterlies, which printed a lot of my stuff. My poetry was pretty dreadful, so exaggerated, but you could see how it might be sensational at the college level because it was just so much more complex in thought and in words than what any of these kids were writing at the time. Anyway, that was the beginning.

What appealed to you about poetry?

I liked it. I had read Shelley and Keats and Walt Whitman, and also I was tremendously fond of Shakespeare's sonnets, even in high school. They had

a great influence on me. I had just discovered Emily Dickinson and through Van Doren I was learning about other poets.

Did poetry spring out of your upbringing in any way?

In no way, except my oldest sister, who is fifteen years older than I and who was going to be a concert pianist before she quit and went to work, was the intellectual in the family. She took us to concerts and so on. I remember as a little kid climbing all the way up those stairs to the top balcony to hear the Boston [concert] series. We lived in a small town [outside New York City], so she had to make some effort to bring us all in to concerts.

That was part of my upbringing, but a lot of my interest was self-generated. At least I don't remember any English teacher in high school who was particularly good, which is often the case.

Many of the Hollywood screenwriters of the thirties and the forties were enamored of newspapers, Broadway, or the movies. But very few were poets, either professionally or in their spare time. Why is it that you embraced poetry?

It expresses things that you cannot express well otherwise. The condensation of language and so on is one of the great pleasures of the craft. There are things that are too subtle to put into novels.

Did being a poet set you apart, even back in college?

In college, people would stop me and say, "What did that poem mean?" I was pretty scornful back then. Also, I wasn't quite sure myself! (Laughs .) But I was famous, or notorious, on campus. In fact, I won the Knopf prize for a book of poetry written by an undergraduate, only it was never published because they decided against it. They were probably right. I'd hate to have that book published! (Laughs .)

Let's see, I graduated from Columbia in 1930 and took postgraduate work through 1931, then was unemployed for about two years. It was a hard time for my whole family because my father lived on a farm and the family was essentially separated. But I had no needs, except for food. Occasionally, my oldest sister, who was still working, would give me a dollar or two, just for pocket money. My first job in that period was in a small factory for six dollars a week, which I would turn over to my mother, of course.

During all this time, were you nursing ambitions of one day becoming a writer?

I had no ambitions of the sort. I had no idea what I was going to be. I had no idea of what a writer was! For a long, long time I gave up writing almost entirely, except for poetry and some short stories. I never considered myself a writer, to tell you the absolute truth, until after the end of World War II.

I was a poet—so what? Where would you go with it?

Then, through my older sister, who had a friend at Bellevue Hospital, I got a job as an orderly and doubled my salary. I began to buy books and magazines. I'd do a lot of browsing and I read Dial, which had a lot of

influence on me, [because of] the poetry they published, the fiction and the art too. (That was the first magazine that published Picasso, and so on.)

Yet I foresaw myself working in the hospital the rest of my life. I really did. It depressed me, but I couldn't see any other way around it.

When Roosevelt came in [in 1932], because of his social service programs anybody with a college degree was considered an intellectual and could get a job as an "investigator." That meant going out into the field with a case list of sixty or seventy people, investigating backgrounds and that sort of thing, recommending people for relief. That's the job I got, for three years.

When I was first assigned to be an investigator, they sent me into a middle-class neighborhood. I was appalled because the parents would hide in the bathroom and leave their teenage daughter to conduct the interview while they would be crying behind closed doors. The shame was beyond belief. It was too close to my own family. I couldn't take it. I asked to be transferred to some poorer district.

Well, they picked the bottom [of the ladder], Sand Street, in lower Brooklyn, a mixture of nationalities. And I really had a wonderful time. When you came down the street, the kids would take your hand and start shouting, "Investigator!" You were a famous man! (Laughs .)

My left-wing poetry really began around this period—some of it was good and some of it was terrible. It was when I was working as an investigator and writing this poetry that I changed my name [to David Wolff], because I didn't want the people at the bureau to think that somehow I was uppity. In Frontier Films I was always known as David Wolff, the name I had adopted. My wife's relatives called me David for years.

Your period of unemployment, your job as an investigator for social relief—that must have also influenced your evolving social consciousness .

No question about it. You have no idea, unless you have experienced it yourself, how it is to be out of work for two years, to have this big gap of empty time which makes you feel as if your life is being wasted. You spend a tremendous amount of time walking around, just looking [for something to do], going to fifteen-cent movies and [sitting through] three features, and so forth. Tremendous waste of time. You feel bitterer and bitterer—no question about it.

Were you, even during this period, enthusiastic about films?

I was tremendously into film, of course. During the two or three years I was unemployed I must have seen hundreds of films—Hollywood films, but also Russian films, French films, and so on. What any intellectual would have looked at in those days. I particularly loved the [Alexander] Dovzhenko films, which essentially, when you look at them, are poetic films, really. Constructed like a poem.

Actually, I came to movies through poetry, in a sense, because when I was still working as an investigator I saw an ad in a New York newspaper for a

poet to write commentary for a short film—a 20-minute film mostly about baggage in a harbor [Harbor Scenes, 1935]. (Laughs .) The filmmaker was Ralph Steiner. A very remarkable man—not a great photographer, but a wonderful craftsman. I worked on the narration for his short film, and through him I met a whole bunch of photographers.

These still photographers were very anxious to make films and for someone to write for their films, and that is how I got drawn into doing the writing for documentary films, which was not too far [afield] from poetry.

As anybody who knows the history of the field can tell you, I invented a way of using narration in film which suited my purposes very well and has influenced other people—which was to construct the narration like poetry, in which every word modifies the image. I worked out a ratio of two words to a second, which worked so perfectly. In those days you ran the film as you were recording the narration, so you had this very, very close connection between the image and the writing. In that sense, I was not a writer, but a poet and a filmmaker. The, narration really meant carpentering phrases so they fit the rhythm of the film.

Had you thought about documentaries at all before answering that ad?

Of course not. I didn't know there was any such thing. I had never seen one in my life.

What appealed to you about documentaries?

It was an opportunity to lift what might seem like a flat, stale level into mountains and valleys, and to create a landscape that way.

On that first documentary, you contributed on the back end, after the footage already existed. Then you were asked to write the poetry, or narration .

That was often the case. And since this was a collective [of Frontier Films], there was at least the semblance of group discussion, so everybody collaborated to some extent. One of the reasons why it took awfully long to make these films was because there was so much talk—these committees went on endlessly. A lot of that history is covered in [William Alexander's book] Film on the Left .

As I worked on more documentaries and joined the collective, I was used to construct the stories as well as the narration. Although these stories were generally written in collaboration with others, the final responsibility for the narration itself was entirely mine.

What was the history of the group before you joined it?

Before I joined, the group was an adjunct to the Film and Photo League, which was formed originally as a cultural branch of the Worker's Relief League, which was a left-wing insurance setup to provide for sickness benefits and funerals and so on. This cultural wing was set up, among other reasons, to encourage photographers, who could pay minimal dues and get to use a darkroom or take instruction. Ralph Steiner was a member of this group, as were Leo Hurwitz and Paul Strand.

There were two groups [later on] really, the permanent group and then, at first, the number of us who had other jobs. (I was still working as an investigator.) I joined the permanent group at a certain point when I was invited.

But this division between the elder statesmen and the younger members remained, and it divided not on ideological grounds so much as on aesthetic grounds. How do you construct a film? Leo Hurwitz had this theory straight out of a Marxist doctrine of dialectics. First, you establish thesis A, then you have antithesis B, then you have the synthesis. Instinct doesn't play any part! Actually, his [Hurwitz's] instincts were very much restrained.

These quarrels went on endlessly. I have a picture of some of us standing on a streetcorner arguing about something, when really the issue was: Where do we go for lunch? Couldn't make up our minds about that, either. (Laughs .)

Hurwitz's wife, Jane Dudley, was a prominent member of the Martha Graham dance troupe, as was my wife [Frieda Maddow], so Frontier Films had a connection to that circle. Since the men were all interested in women and these women were all interested in men, it seemed ideal for us to have a Halloween party together at one point and tell ghost stories, bob for apples, stuff like that. We assembled at somebody's studio. The Martha Graham dancers—beautiful girls, great dancers all—were terribly excited to meet all these great and famous men that they'd heard about (at least, famous within this tiny circle). The men arrived and stood around in their coats without ever unbuttoning them. They couldn't stop arguing! They never paid any attention to the women at all! What lumps! (Laughs .)

Would you say that the conceptual difference between the elder statesmen and the Young Turks, in Frontier Films, was that the older group were formalists and the younger group were experimentalists?

I would say so. But we never thought of it that way. We would argue about specifics. Someone like Sidney Meyers, for example, was a great editor. He would edit out of instinct and do crazy things.

And the formalists would come along and say . . .?

"This doesn't fit here . . ." Also contributing to the division was the fact that the group was always under tremendous financial difficulties. You would not be paid for two or three months, you couldn't pay your rent, you'd run out of money, you'd get very hungry—actually physically hungry. Whereas, the interesting thing, you see, is that both Strand and Hurwitz had independent sources of income. Hurwitz, through his wife, whose parents owned Reader's Digest .

How did the group construe itself politically?

The group felt that it was left-labor. You might say the group followed the Communist line, but the Communist line at that point was very Popular Front. [U.S. Communist Party Chairman Earl] Browder's point was "Communism is twentieth-century Americanism." That's the reason the party drew in a lot

of people, influential people like [composer] Aaron Copland, at the time, as well as a whole broad body of people.

I can't imagine that the people in Frontier Films had a positive attitude towards Hollywood .

Of course not.

Was that conflicting for you?

No, because I didn't have any feeling about Hollywood one way or another. I enjoyed the films, but I never felt ashamed of enjoying them.

I assume the culmination of this documentary period was the making of Native Land.

That was a big, huge project in which Frontier Films really went broke because Hurwitz was such a perfectionist. You can see it in the film. There are strange things in the film which you can only understand if you understand what was happening to the Left at that time. I explained to you about the Popular Front. Now, for example, in Native Land, there were long, long sequences of flag-waving in various situations. . . . Hurwitz could never let go of any one sequence because he loved the way the narrative flowed, so there would be sequence after sequence of flag-waving.

Then, of course, there was the glorification of the skyscraper. It does look beautiful, these marvelous camera movements which were really invented by Hurwitz, though Strand was a very ecstatic cinematographer. The equation of the white church spires of New England with the skyscraper, as equivalents of American aesthetics, is really a Hurwitz idea, though Strand was also very sensitive to that kind of thing. But that only works, you see, if you think there is an American aesthetic. Perhaps there is. It's a very difficult question. In addition to that, you had smokestacks as the ideal of prosperity. When this [film] is shown nowadays, people in the audience hoot! Spilling pollution into the air! (Laughs .)

All those values have been turned upside down .

Don't forget I was already in the army by the time the film was finished, and the war [World War II], in a way, perverted the film further, so that [in the editing] it became more patriotic perhaps than it was intended to be at first.

I had already done my work and moved on. Starving as I was on one meal a day or so, I took a job with Willard Van Dyke, a friend of mine who was also connected with Frontier Films in earlier days. Now he was making documentaries independently, and I was engaged to write a film for him. This caused considerable turmoil. It was like a betrayal to go and work for somebody else, to try to pay your rent or anything.

Willard Van Dyke was going on this expedition to South America, and I was taken along as a writer. There was an assistant cameraman; Van Dyke was the cameraman and director. It was all paid for by one of the foundations.

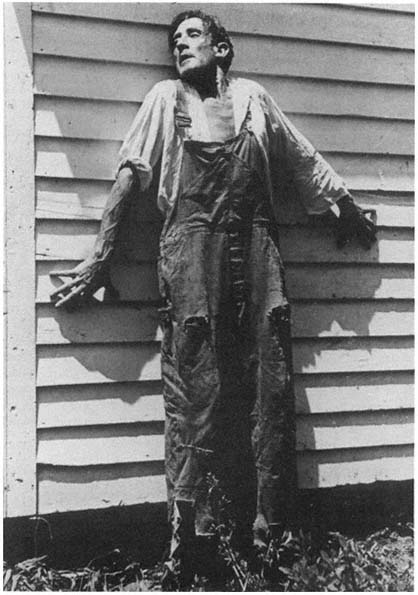

A vignette from the famous Frontier Films documentary about racism and

flag-waving in America, Native Land, script by Ben Maddow.

(Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

It [The Bridge, 1944] did not become much of a film, but we had a wonderful time. I had never seen a mountain higher than Bear Mountain [in New York], which is what, eight hundred feet? And Van Dyke had never been abroad. So we cruised all around South America in a sort of magical dream voyage.

So was your departure from Frontier Films acrimonious?

No, it was semifriendly, because when my credits appeared on this first film, it said, "David Wolff, courtesy of Frontier Films." (Laughs .) Which didn't mean a thing to anybody. The issue was not on ideological grounds, as it was really practical. The issue was the terrible tendency of any collective to hold on to its members and regard anybody as treasonable who strays.

How do you look back on those documentaries nowadays?

Oh, some of them are probably very interesting. I haven't looked at them in a long, long time. Native Land has some very marvelous things in it, but as a whole it does not work. It's too spread out, too theoretical in a way. Too much A-B, A-B, then finally C. I think that Strand did not really feel at home in structure, though, of course, Strand and Hurwitz quarreled bitterly later on over who was the person who should have major credit for Native Land .

Did you know many other writers during this period, in the thirties?

No. What I knew was a political circle of various shades of opinion. I also knew a circle of poets that included Muriel Rukeyser, Maxwell Bodenheim, and Kenneth Fearing. We'd often read our poetry [publicly]. Bodenheim always read with his back to the audience and his face to the poets. I once wrote a long story about Muriel Rukeyser which is probably the best short story I ever wrote. It was called "You, Johann Sebastian Bach," a title I later changed to "A Pianist." It won a couple of prizes. I was very moved by the fact that she was a lesbian who wanted a child and went deliberately about getting and raising one. She was really a wonderful woman who, all her life, felt she was very ugly.

How did you read your poetry?

Straight off! (Laughs .)