Ben Maddow: The Invisible Man

Interview by Pat McGilligan

The real Ben Maddow is cloaked by several overlapping careers and two distinct writing pseudonyms. In spite of this, if not because of it, his reputation is firm as one of the more subtle and intelligent Hollywood screenwriters of his era, even though Maddow insists that screenwriting, for him, was never much more than a job.

As "David Wolff," beginning in the early 1930s, Maddow Wrote short stories and poetry, often with an edge of social consciousness, that were published in leading literary journals. In 1935 he embarked on an association with Frontier Films, writing the narration and commentary for some of the best documentaries of the period, including the seminal Native Land (1942). (That association is explored in a first-rate book, Film on the Left: American Documentary Film from 1931 to 1942, by William Alexander. And in the following interview, Maddow elaborates on the personal history that spurred his political commitment.)

Under his own name, in Hollywood, Maddow wrote, among other films, the scripts for the MGM adaptation of William Faulkner's Intruder in the Dust (1949) and John Huston's version of W. R. Burnett's novel The Asphalt Jungle (1950). These two assignments swiftly established him as among the most resourceful of the new, postwar scriptwriters. His subsequent scripts ranged the gamut of melodrama, but they managed to be deeply humane as well as beautifully constructed.

Although Maddow would occasionally turn down a project because he preferred to work on a poem or documentary, his motion picture career seemed secure—until the blacklist descended. Because of his long résumé as a left-winger, Maddow suddenly found himself unemployable.

Enter writer-producer Philip Yordan, and a decade of credits for Maddow

and Yordan that many others—from the Cahiers du Cinéma group to the writers of most standard film-reference books—have tried without success to untangle. Until now, Maddow had never been interviewed on the subject of Yordan, and his revelations clarify as well as deepen the questions of Maddow's masquerade as "Philip Yordan" during the murky McCarthyist years.

It seems that Yordan was a sort of "front" for Maddow on at least a half dozen films. Foremost among them, reportedly, was the cult classic Johnny Guitar (1954), which some critics regard as a political allegory about the anti-Red hysteria in the United States. Nowadays Maddow says he doesn't recognize that film in the slightest, while Yordan (see Philip Yordan interview) insists he alone rewrote someone else's script while on location in Arizona. The other Yordan jobs (usually involving, in some fashion, ex-Frontier Films editor Irving Lerner and writer-producer Sidney Harmon)[*] helped make ends meet for the writer. But Maddow's psychology, as a kind of invisible man, deteriorated.

There have long been reports that Maddow capitulated to the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) towards the end of the 1950s, but they have been unverified in print. Friends of Maddow did not want to believe such disheartening news at the time. Maddow was considered among the most likeable, honorable people on the Left. Not only was he regarded as a stalwart, but he had weathered much of the decade with regular, interesting work.

When I first spoke to Maddow, it must be admitted that he dodged me on this subject. He said he had not cooperated with HUAC interrogators; he said he had not signed any statement or "named" anybody. Because that was my first face-to-face encounter with the mystifying forgetfulness of an informer, I was properly persuaded.

Later that summer, at a film festival in Vermont, I mentioned my interview with Maddow to the octogenarian documentary filmmaker Leo Hurwitz (one of the key figures of Frontier Films), to screenwriter Walter (The Front) Bernstein, and to animator Faith Hubley. Hurwitz's eyes went cold and he let me know, in no uncertain terms, that I had been conned. "He named me!" said Hurwitz. Bernstein and Hubley, both longtime acquaintances of Maddow,

* An intriguing filmmaker, Irving Lerner began his long career as a Frontier Films editor, cameraman, and second-unit director, working on such notable documentaries as Willard Van Dyke's Valley Town (1940) and Robert Flaherty's The Land (1941). After service with the Office of War Information and the Educational Film Institute of New York University, Lerner came to Hollywood, where he worked on the fringes of the film industry, making low-budget thrillers in the 1950s (Murder by Contract and City of Fear ) and later on, in the 1960s and 1970s, bigger-budget epics like Custer of the West (1968). He also co-edited the political thriller about the assassination of President Kennedy, Executive Action (1973). His filmography is studded with collaborations with Maddow, Joseph Strick, Philip Yordan, and Sidney Harmon.

Sidney Harmon was a writer-producer associated, in some capacity with Frontier Films and the Group Theatre in New York in the 1930s. In Hollywood from the late 1930s, his credits include an Academy Award nomination for a script contribution to The Talk of the Town (1942) and various work on many Yordan films.

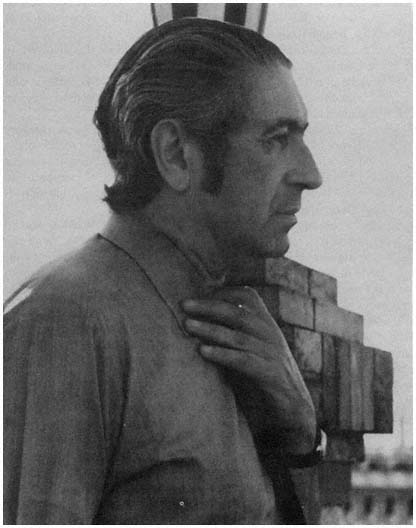

Poet, documentarist, scriptwriter, and "hombre misterioso" Ben Maddow, photographed

in the mid-1950s. (Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

filled me in on other details of Maddow's "cooperation," something that was painful common knowledge among the community of blacklist survivors.

At this point I arranged a second interview with Ben Maddow and once again went over this highly sensitive ground. This time, faced with my insider information and my insistence on talking about the blacklist, Maddow opened up—somewhat.

His allegation that there was a payoff to clear his name has been echoed by others aware of this "escape route." Evidently, this was one subtext of the blacklist, though it has never been substantiated.

As if the Yordan confusion were not enough, Maddow also divulged, in this second conversation, other grey areas among his credits, including work on early drafts of High Noon (1952) and The Wild One (1954), and one subrosa stint with director Elia Kazan, whose own "friendly" testimony before HUAC remains a touchstone of any history of the blacklist.

In the end, Maddow's "informing-by-dispensation" (a separate category created solely for Maddow in Victor Navasky's indispensable chronicle of the Hollywood blacklist and the ethics of informing, Naming Names ) taints an otherwise admirable career and adds an unfortunate facet of complexity to someone whose hallmark as a writer was otherwise his integrity, his individuality, and his critique of society.

Though he never quite regained stature after the blacklist, Maddow worked intermittenly as a screenwriter and as a semidocumentary director. With distinction, he augmented his Hollywood career by branching into independent, avant-garde filmmaking with such notable films as The Savage Eye (1960) and Jean Genet's The Balcony (1963), both in partnership with Joseph Strick; An Affair of the Skin (1964); and Storm of Strangers (1970).

His last motion picture credit, to date, is the occult curiosity The Mephisto Waltz (1971), a genre piece whose story is a coded defense of his HUAC transgression, perhaps, for the heroine is the victim of a Satanic cult who achieves a dubious revenge by meticulously staging her own death.

A reticent and private man, Maddow retired from screenwriting in the early 1970s and presently devotes himself to writing fiction and books about photography.

Ben Maddow (David Wolff) (1909–1992)

As David Wolff

1935

Harbor Scenes (Ralph Steiner Productions). Narration.

1936

The World Today (Nykino). Commentary.

1937

Heart of Spain (Frontier Films). Co-narration.

China Strikes Back (Frontier Films). Co-narration.

1937

People of the Cumberland (Frontier Films). Co-commentary.

1938

Return to Life (Frontier Films). Narration

1939

The History and Romance of Transportation (Frontier Films). Co-commentary.

1940

United Action (Frontier Films). Co-commentary.

White Flood (Frontier Films). Co-commentary.

Tall Tales (Brandon Films). Commentary.

Valley Town (University and Documentary Film Distributions). Co-commentary.

1941

A Place to Live (Documentary Film Productions). Commentary.

Here Is Tomorrow (Documentary Film Productions). Commentary.

1942

Native Land (Leo Hurwitz, Paul Strand, Al Saxon, William Watts). Co-script.

As Ben Maddow

1944

The Bridge (Documentary Film Productions). Script.

Northwest, U.S.A. (Office of War Information). Co-commentary.

1947

Framed (Richard Wallace). Script.

1948

The Photographer (Affiliated Film Producers). Co-commentary.

Kiss the Blood off My Hands (Norman Foster). Co-adaptation.

The Man from Colorado (Henry Levin). Co-script.

1949

Intruder in the Dust (Clarence Brown). Script.

1950

The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston). Co-script.

1951

The Steps of Age (Ben Maddow). Director, co-script.

1952

Shadow in the Sky (Fred M. Wilcox). Script.

High Noon (Fred Zinnemann). Uncredited contribution.

1953

The Stairs (Ben Maddow). Director, script.

Man Crazy (Irving Lerner). Uncredited contribution.

1954

The Wild One (Laslo Benedek). Uncredited contribution.

The Naked Jungle (Byron Haskin). Uncredited contribution.

Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray). Uncredited contribution.

1957

Men in War (Anthony Mann). Uncredited contribution.

Gun Glory (Roy Rowland). Uncredited contribution.

1958

God's Little Acre (Anthony Mann). Uncredited contribution.

Murder by Contract (Irving Lerner). Uncredited contribution.

1960

Wild River (Elia Kazan). Uncredited contribution.

The Unforgiven (John Huston). Script.

The Savage Eye (Ben Maddow, Joseph Strick, Sidney Meyers). Co-producer, co-director, co-script, co-story.

1961

Two Loves (Charles Walters). Script.

1963

The Balcony (Joseph Strick). Producer, script.

1964

An Affair of the Skin (Ben Maddow). Director, script, story.

1967

The Way West (Andrew V. McLaglen). Co-script.

1969

The Chairman (J. Lee Thompson). Script.

The Secret of Santa Vittoria (Stanley Kramer). Co-script.

1970

Storm of Strangers (Ben Maddow). Director, script.

1971

The Mephisto Waltz (Paul Wendkos). Script.

Television credits include "Man on a String" (CBS, 1972).

Plays include In a Cold Hotel (one-act), The Ram's Horn (one-act), and Soft Targets .

Published works include Forty-Four Gravel Street, Gauntlet of Flowers, Poems, The City, Elegy upon a Certificate of Birth, Song of Twelve Fridays, Edward Weston: Fifty Years: The Definitive Volume of His Photographic Work (a.k.a. Edward Weston: His Life and Photographs), Faces: A Narrative History of the Portrait in Photography from 1820 to the Present, A Sunday Between Wars: The Course of American Life from 1865 to 1917, The Photography of Max Yavno, and Aperture, No. 92 .

Academy Awards include best-script nomination for The Asphalt Jungle .

Writers Guild awards include best-script nominations for The Man from Colorado, The Asphalt Jungle, Intruder in the Dust, and The Balcony .

Act One—

A Poet, So What?

When did you first feel that you wanted to become a writer?

It was in college [Columbia University]. I began writing a lot of poetry. Mark Van Doren was one of my professors and he was the adviser to one of the literary quarterlies, which printed a lot of my stuff. My poetry was pretty dreadful, so exaggerated, but you could see how it might be sensational at the college level because it was just so much more complex in thought and in words than what any of these kids were writing at the time. Anyway, that was the beginning.

What appealed to you about poetry?

I liked it. I had read Shelley and Keats and Walt Whitman, and also I was tremendously fond of Shakespeare's sonnets, even in high school. They had

a great influence on me. I had just discovered Emily Dickinson and through Van Doren I was learning about other poets.

Did poetry spring out of your upbringing in any way?

In no way, except my oldest sister, who is fifteen years older than I and who was going to be a concert pianist before she quit and went to work, was the intellectual in the family. She took us to concerts and so on. I remember as a little kid climbing all the way up those stairs to the top balcony to hear the Boston [concert] series. We lived in a small town [outside New York City], so she had to make some effort to bring us all in to concerts.

That was part of my upbringing, but a lot of my interest was self-generated. At least I don't remember any English teacher in high school who was particularly good, which is often the case.

Many of the Hollywood screenwriters of the thirties and the forties were enamored of newspapers, Broadway, or the movies. But very few were poets, either professionally or in their spare time. Why is it that you embraced poetry?

It expresses things that you cannot express well otherwise. The condensation of language and so on is one of the great pleasures of the craft. There are things that are too subtle to put into novels.

Did being a poet set you apart, even back in college?

In college, people would stop me and say, "What did that poem mean?" I was pretty scornful back then. Also, I wasn't quite sure myself! (Laughs .) But I was famous, or notorious, on campus. In fact, I won the Knopf prize for a book of poetry written by an undergraduate, only it was never published because they decided against it. They were probably right. I'd hate to have that book published! (Laughs .)

Let's see, I graduated from Columbia in 1930 and took postgraduate work through 1931, then was unemployed for about two years. It was a hard time for my whole family because my father lived on a farm and the family was essentially separated. But I had no needs, except for food. Occasionally, my oldest sister, who was still working, would give me a dollar or two, just for pocket money. My first job in that period was in a small factory for six dollars a week, which I would turn over to my mother, of course.

During all this time, were you nursing ambitions of one day becoming a writer?

I had no ambitions of the sort. I had no idea what I was going to be. I had no idea of what a writer was! For a long, long time I gave up writing almost entirely, except for poetry and some short stories. I never considered myself a writer, to tell you the absolute truth, until after the end of World War II.

I was a poet—so what? Where would you go with it?

Then, through my older sister, who had a friend at Bellevue Hospital, I got a job as an orderly and doubled my salary. I began to buy books and magazines. I'd do a lot of browsing and I read Dial, which had a lot of

influence on me, [because of] the poetry they published, the fiction and the art too. (That was the first magazine that published Picasso, and so on.)

Yet I foresaw myself working in the hospital the rest of my life. I really did. It depressed me, but I couldn't see any other way around it.

When Roosevelt came in [in 1932], because of his social service programs anybody with a college degree was considered an intellectual and could get a job as an "investigator." That meant going out into the field with a case list of sixty or seventy people, investigating backgrounds and that sort of thing, recommending people for relief. That's the job I got, for three years.

When I was first assigned to be an investigator, they sent me into a middle-class neighborhood. I was appalled because the parents would hide in the bathroom and leave their teenage daughter to conduct the interview while they would be crying behind closed doors. The shame was beyond belief. It was too close to my own family. I couldn't take it. I asked to be transferred to some poorer district.

Well, they picked the bottom [of the ladder], Sand Street, in lower Brooklyn, a mixture of nationalities. And I really had a wonderful time. When you came down the street, the kids would take your hand and start shouting, "Investigator!" You were a famous man! (Laughs .)

My left-wing poetry really began around this period—some of it was good and some of it was terrible. It was when I was working as an investigator and writing this poetry that I changed my name [to David Wolff], because I didn't want the people at the bureau to think that somehow I was uppity. In Frontier Films I was always known as David Wolff, the name I had adopted. My wife's relatives called me David for years.

Your period of unemployment, your job as an investigator for social relief—that must have also influenced your evolving social consciousness .

No question about it. You have no idea, unless you have experienced it yourself, how it is to be out of work for two years, to have this big gap of empty time which makes you feel as if your life is being wasted. You spend a tremendous amount of time walking around, just looking [for something to do], going to fifteen-cent movies and [sitting through] three features, and so forth. Tremendous waste of time. You feel bitterer and bitterer—no question about it.

Were you, even during this period, enthusiastic about films?

I was tremendously into film, of course. During the two or three years I was unemployed I must have seen hundreds of films—Hollywood films, but also Russian films, French films, and so on. What any intellectual would have looked at in those days. I particularly loved the [Alexander] Dovzhenko films, which essentially, when you look at them, are poetic films, really. Constructed like a poem.

Actually, I came to movies through poetry, in a sense, because when I was still working as an investigator I saw an ad in a New York newspaper for a

poet to write commentary for a short film—a 20-minute film mostly about baggage in a harbor [Harbor Scenes, 1935]. (Laughs .) The filmmaker was Ralph Steiner. A very remarkable man—not a great photographer, but a wonderful craftsman. I worked on the narration for his short film, and through him I met a whole bunch of photographers.

These still photographers were very anxious to make films and for someone to write for their films, and that is how I got drawn into doing the writing for documentary films, which was not too far [afield] from poetry.

As anybody who knows the history of the field can tell you, I invented a way of using narration in film which suited my purposes very well and has influenced other people—which was to construct the narration like poetry, in which every word modifies the image. I worked out a ratio of two words to a second, which worked so perfectly. In those days you ran the film as you were recording the narration, so you had this very, very close connection between the image and the writing. In that sense, I was not a writer, but a poet and a filmmaker. The, narration really meant carpentering phrases so they fit the rhythm of the film.

Had you thought about documentaries at all before answering that ad?

Of course not. I didn't know there was any such thing. I had never seen one in my life.

What appealed to you about documentaries?

It was an opportunity to lift what might seem like a flat, stale level into mountains and valleys, and to create a landscape that way.

On that first documentary, you contributed on the back end, after the footage already existed. Then you were asked to write the poetry, or narration .

That was often the case. And since this was a collective [of Frontier Films], there was at least the semblance of group discussion, so everybody collaborated to some extent. One of the reasons why it took awfully long to make these films was because there was so much talk—these committees went on endlessly. A lot of that history is covered in [William Alexander's book] Film on the Left .

As I worked on more documentaries and joined the collective, I was used to construct the stories as well as the narration. Although these stories were generally written in collaboration with others, the final responsibility for the narration itself was entirely mine.

What was the history of the group before you joined it?

Before I joined, the group was an adjunct to the Film and Photo League, which was formed originally as a cultural branch of the Worker's Relief League, which was a left-wing insurance setup to provide for sickness benefits and funerals and so on. This cultural wing was set up, among other reasons, to encourage photographers, who could pay minimal dues and get to use a darkroom or take instruction. Ralph Steiner was a member of this group, as were Leo Hurwitz and Paul Strand.

There were two groups [later on] really, the permanent group and then, at first, the number of us who had other jobs. (I was still working as an investigator.) I joined the permanent group at a certain point when I was invited.

But this division between the elder statesmen and the younger members remained, and it divided not on ideological grounds so much as on aesthetic grounds. How do you construct a film? Leo Hurwitz had this theory straight out of a Marxist doctrine of dialectics. First, you establish thesis A, then you have antithesis B, then you have the synthesis. Instinct doesn't play any part! Actually, his [Hurwitz's] instincts were very much restrained.

These quarrels went on endlessly. I have a picture of some of us standing on a streetcorner arguing about something, when really the issue was: Where do we go for lunch? Couldn't make up our minds about that, either. (Laughs .)

Hurwitz's wife, Jane Dudley, was a prominent member of the Martha Graham dance troupe, as was my wife [Frieda Maddow], so Frontier Films had a connection to that circle. Since the men were all interested in women and these women were all interested in men, it seemed ideal for us to have a Halloween party together at one point and tell ghost stories, bob for apples, stuff like that. We assembled at somebody's studio. The Martha Graham dancers—beautiful girls, great dancers all—were terribly excited to meet all these great and famous men that they'd heard about (at least, famous within this tiny circle). The men arrived and stood around in their coats without ever unbuttoning them. They couldn't stop arguing! They never paid any attention to the women at all! What lumps! (Laughs .)

Would you say that the conceptual difference between the elder statesmen and the Young Turks, in Frontier Films, was that the older group were formalists and the younger group were experimentalists?

I would say so. But we never thought of it that way. We would argue about specifics. Someone like Sidney Meyers, for example, was a great editor. He would edit out of instinct and do crazy things.

And the formalists would come along and say . . .?

"This doesn't fit here . . ." Also contributing to the division was the fact that the group was always under tremendous financial difficulties. You would not be paid for two or three months, you couldn't pay your rent, you'd run out of money, you'd get very hungry—actually physically hungry. Whereas, the interesting thing, you see, is that both Strand and Hurwitz had independent sources of income. Hurwitz, through his wife, whose parents owned Reader's Digest .

How did the group construe itself politically?

The group felt that it was left-labor. You might say the group followed the Communist line, but the Communist line at that point was very Popular Front. [U.S. Communist Party Chairman Earl] Browder's point was "Communism is twentieth-century Americanism." That's the reason the party drew in a lot

of people, influential people like [composer] Aaron Copland, at the time, as well as a whole broad body of people.

I can't imagine that the people in Frontier Films had a positive attitude towards Hollywood .

Of course not.

Was that conflicting for you?

No, because I didn't have any feeling about Hollywood one way or another. I enjoyed the films, but I never felt ashamed of enjoying them.

I assume the culmination of this documentary period was the making of Native Land.

That was a big, huge project in which Frontier Films really went broke because Hurwitz was such a perfectionist. You can see it in the film. There are strange things in the film which you can only understand if you understand what was happening to the Left at that time. I explained to you about the Popular Front. Now, for example, in Native Land, there were long, long sequences of flag-waving in various situations. . . . Hurwitz could never let go of any one sequence because he loved the way the narrative flowed, so there would be sequence after sequence of flag-waving.

Then, of course, there was the glorification of the skyscraper. It does look beautiful, these marvelous camera movements which were really invented by Hurwitz, though Strand was a very ecstatic cinematographer. The equation of the white church spires of New England with the skyscraper, as equivalents of American aesthetics, is really a Hurwitz idea, though Strand was also very sensitive to that kind of thing. But that only works, you see, if you think there is an American aesthetic. Perhaps there is. It's a very difficult question. In addition to that, you had smokestacks as the ideal of prosperity. When this [film] is shown nowadays, people in the audience hoot! Spilling pollution into the air! (Laughs .)

All those values have been turned upside down .

Don't forget I was already in the army by the time the film was finished, and the war [World War II], in a way, perverted the film further, so that [in the editing] it became more patriotic perhaps than it was intended to be at first.

I had already done my work and moved on. Starving as I was on one meal a day or so, I took a job with Willard Van Dyke, a friend of mine who was also connected with Frontier Films in earlier days. Now he was making documentaries independently, and I was engaged to write a film for him. This caused considerable turmoil. It was like a betrayal to go and work for somebody else, to try to pay your rent or anything.

Willard Van Dyke was going on this expedition to South America, and I was taken along as a writer. There was an assistant cameraman; Van Dyke was the cameraman and director. It was all paid for by one of the foundations.

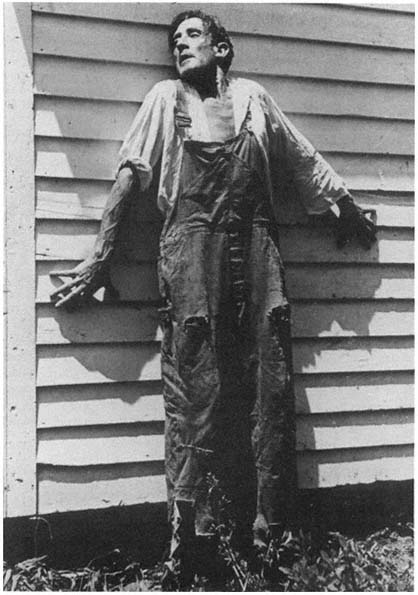

A vignette from the famous Frontier Films documentary about racism and

flag-waving in America, Native Land, script by Ben Maddow.

(Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

It [The Bridge, 1944] did not become much of a film, but we had a wonderful time. I had never seen a mountain higher than Bear Mountain [in New York], which is what, eight hundred feet? And Van Dyke had never been abroad. So we cruised all around South America in a sort of magical dream voyage.

So was your departure from Frontier Films acrimonious?

No, it was semifriendly, because when my credits appeared on this first film, it said, "David Wolff, courtesy of Frontier Films." (Laughs .) Which didn't mean a thing to anybody. The issue was not on ideological grounds, as it was really practical. The issue was the terrible tendency of any collective to hold on to its members and regard anybody as treasonable who strays.

How do you look back on those documentaries nowadays?

Oh, some of them are probably very interesting. I haven't looked at them in a long, long time. Native Land has some very marvelous things in it, but as a whole it does not work. It's too spread out, too theoretical in a way. Too much A-B, A-B, then finally C. I think that Strand did not really feel at home in structure, though, of course, Strand and Hurwitz quarreled bitterly later on over who was the person who should have major credit for Native Land .

Did you know many other writers during this period, in the thirties?

No. What I knew was a political circle of various shades of opinion. I also knew a circle of poets that included Muriel Rukeyser, Maxwell Bodenheim, and Kenneth Fearing. We'd often read our poetry [publicly]. Bodenheim always read with his back to the audience and his face to the poets. I once wrote a long story about Muriel Rukeyser which is probably the best short story I ever wrote. It was called "You, Johann Sebastian Bach," a title I later changed to "A Pianist." It won a couple of prizes. I was very moved by the fact that she was a lesbian who wanted a child and went deliberately about getting and raising one. She was really a wonderful woman who, all her life, felt she was very ugly.

How did you read your poetry?

Straight off! (Laughs .)

Act Two—

Pure Accident

Why did it take you so long to get to Hollywood?

That was pure accident. Everything in my life, actually, is an accident. Opportunities came up, or choices came up in which there was very little choice.

When I came back from South America, I was drafted. I just had enough time to finish the film before I went into the army. Because of my documentary background I was asked to join the Signal Corps. I went out to Long Island where there were writers sitting in boxes that had just been built for them. I had just come from a great adventure, and I was not going to sit in a

damn box and be a writer. I didn't feel I was a writer. Whatever else the army wanted to do with me, fine.

I was given a series of tests, and it was decided I'd make a great radio technician because my hearing was good and I could distinguish one tone from another. So I was shipped out to Los Angeles to radio school where there was a ten-week course in building radios. That is where I met a number of movie people because, as soldiers, we went to the Hollywood parties. One person I met turned out to be working for the Air Force motion picture unit. Well, the Air Force motion picture unit needed people badly, particularly people with experience on documentaries for their training films. I was asked to join.

That's how I got to Hollywood [the first time]. Most of the people in the Air Force motion picture unit were ex-Hollywood people. Ronnie Reagan was there. I used him as a narrator over and over again. He was very good at it. He could read things that couldn't have meant anything to him—you know, a B-29 electrical system—with the utmost conviction. Just take the script overnight and come back and read it with all the right phrases and emphasis. He was very good at it; he didn't understand what he was reading, and he wasn't expected to.

So during the war, ironically, you continued to make documentaries?

I must have done 200–250 documentaries. All in Los Angeles—except for trips that you had to take to do the shooting. I was writer and producer because I knew enough about the craft to supervise all parts of it.

Were you meeting Hollywood writers?

Actually, the only one who made any impression on me was Lester Koenig, who had worked with William Wyler as an assistant.[*] After the war, he wanted me to collaborate with him on a film about the OSS. He and I worked on the script, but it never got made. Meanwhile, my wife got an offer of a job through [choreographer-director] Michael Kidd to dance in Finian's Rainbow in New York, so I went back to New York with her and that was when I sat down and wrote a novel based on my social work experience, called 44 Gravel Street [1952].

Now then, another accident occurred. Someone who had been a dancer, a terrible dancer and a general phoney, named Harold Hecht, called me up and asked would I collaborate on a film [with him]. Because he admired my poetry, he thought I was the right man for the subject. He would pay me what seemed like an enormous sum! Frieda was getting tired of her job, too; she'd been doing the same dance over and over again for almost seven months. (Laughs .)

So we returned to Hollywood. That film was made—a terrible film with a most ridiculous title. Kiss the Blood off My Hands [1948] it was called.

* Lester Koenig wrote the narration for William Wyler's wartime documentary The Memphis Belle (1943). Later he served in a production capacity for Wyler on The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), The Heiress (1949), and Carrie (1952).

Everything about it was bad. I didn't know what I was doing. [Screenwriter] Walter Bernstein worked on it with me. He had actually been in the OSS in Yugoslavia and had written a book [Keep Your Head Down, 1945] about his experiences.[*]

Did having been a documentarist help you at all, in the beginning, as a screenwriter?

In both cases, you have to feel your way. In a documentary, you are not dealing with the paramount importance of the character decision. In Hollywood I always had to struggle with formal structure because structure in a documentary is quite a different thing, whereas in a dramatic story you have the same titanic problem every time. You are struggling with how to make things come out right [in the balance], the pace and everything. How much time you give to certain things, how much importance . . . it's very complex.

I can say this without humility. My mind is very elaborate and full of rich associations, and I have to fight that in order to squeeze into a formal structure, a dramatic time sequence.

Was poetry any use in screenwriting?

It's not [of any use], except that it might allow you to strike off a phrase that is "right" because you are interested in words. You see, a poet is a specialist in words. He knows that there is the center, which is the main meaning; beyond that there is a kind of umbra of associated meaning; and beyond that there is an emotional thing, a much larger penumbra. Now, as a poet, you're fitting these things together and making one penumbra yield to another and so forth. It's a wonderfully complicated process.

It seems like quite a leap from Kiss the Blood off My Hands to Intruder in the Dust.

Another accident. A close friend of mine at the [army] post happened to be a writer. He and I struck up a friendship because of a poem that I had published in an issue of Symposium which also had an article on jazz. I'd never heard jazz before, and the article made me want to listen to it and buy records. I became a wild enthusiast, which is also, incidentally, part of the intellectual atmosphere in New York. Anyway, we formed a jazz club, and we'd go out and buy secondhand records and play them. His wife happened to be the head of the script department at Metro, and because I had gotten a very good reputation at the post, she knew about my work. She recommended me to [director] Clarence Brown, who had bought this Faulkner novel and didn't know what the hell to do with it.

It was a very poor and complicated novel, which Faulkner wrote because he thought a series with a lawyer as a detective would make him a lot of

* Kiss the Blood off My Hands was Walter Bernstein's only script credit before the blacklist. Resuming his career in 1959, Bernstein worked often and well with directors Sidney Lumet and Martin Ritt, and after a period of hard-edged drama in the 1960s, turned successfully to comedy in the 1970s. His credits include That Kind of Woman (1959), Heller in Pink Tights (1960), Paris Blues (1961), Fail Safe (1964), The Train (1965), The Molly Maguires (1970), The Front (1976), Semi-Tough (1977), Yanks (1979), and The House on Carroll Street (1988).

money. There are some things I like about the novel, but you can't compare it with Light in August . After I did the screenplay, that screenplay became very famous at Metro and was shown around a lot. All my experience in documentaries, trying to put together and straighten out things out of a huge mass of chaotic material, paid off there. That was the beginning [of my Hollywood career].

Did you have a special feeling for Faulkner?

I was an enthusiast. I had read all of his novels, even the earliest ones. Clarence Brown couldn't think his way through the script, because in the original novel there are four disinterments, and you cannot have somebody dug up out of the grave four times. You had to simplify it to one disinterment at most, and then you had to straighten the plot out. Faulkner's plot is all told backward, which confused Brown. I had to explain the novel to him, though I think any bright person that was interested in the story could have worked it [the script] out.

Brown had a huge office, and he would sit at one end of it and I would sit in a chair facing him—it seemed like half a mile distant, although actually there was much more office behind me as well. He had a parakeet in a cage, and he would open the cage and this parakeet would fly around while Brown dozed off, which he often would do during long script conferences. The parakeet would land on Brown's head and sit there, and he and I would wait patiently until Brown woke up, and then the parakeet would fly around some more.

Why would Clarence Brown, a director best known for those highly romanticized Garbo pictures, want to make a movie of Intruder in the Dust?

When he was seventeen or eighteen and going to school in Atlanta, there was a full-blown race riot.[*] Brown had seen blacks pursued in the streets, killed and loaded on flat cars, and driven out of town to be dumped in the woods. He had never forgotten it, and he told me he wanted to make amends for this part of his own history that he could never forget. And somebody had recommended this book to him, which was about an unjustly accused black, although, as you know, the chief character [in the movie] is not played by a black person but by a Puerto Rican [Juano Hernandez].

Why is that?

That would have been going too far for Metro, at the time. This was block booking, remember. I was walking with Clarence Brown at Metro once when we passed Louis B. Mayer. We stopped and they shook hands and Mayer said, "By the way, Clarence, why do you want to make this picture about the South?" Brown said, "I just think it's a good story and I'd like to make it. . . ." And Mayer replied, "All right, Clarence, anything you want. . . ."

* Probably Maddow is referring to the spring of 1913 race riots in Atlanta, although that would place Brown in his early twenties at the time. Director Brown himself often referred to this event as inspiring his decision to film Intruder in the Dust, without pinpointing the details or date.

Because Brown had directed not only the Garbo pictures, but National Velvet [1944] and many other films.

How did you feel about the finished product?

I thought it was very, very good. Most times when a writer does a script that he himself likes, when he sees the film there is nothing but terrible shock and dismay. Because the screenplay is a daydream in which you put down certain key points. In between, you only imagine what happens. It's implicit in your head. Okay. Now, somebody else takes the script and directs it, and what you see are the same words [of the script] but the in-between is not what you imagined at all. The movements, the bodies, the locations, even the faces, the makeup, everything—they're not what you imagined.

But in this case, they were, because Faulkner is so precise in detail. That is one of his tremendous merits. No matter how foolish some of his ideas are, he sticks to the truth of the location itself. So you have this material [in the novel] that is so rich. The very movements are described, how people walk, and so on. That is really a great thrill to see [on the screen].

The one thing I thought was silly, a hangover [from his own upbringing], was Clarence Brown's idea of making a joke by having blacks' eyeballs pop. It was [an idea] straight out of the twenties. The blacks who saw the film noticed it and resented it, naturally. But that's not in the screenplay. Obviously, it could not be.

Did Faulkner ever say anything to you about the film?

I never met him. He was in Oxford, Mississippi. The writers were not at that time ever paid to go to the location. You finished your job and that was the end of it.

For a while [producer] Val Lewton became a friend of mine. He was a very interesting man. He was one of the people who admired Intruder in the Dust and went around Metro talking about it. We met later on and he told me stories about Faulkner. Faulkner lived next door to him in Palos Verdes. Every Sunday morning Faulkner would come over and visit him. Lewton would serve him whiskey and ice. There was a parapet [on his porch] which Faulkner would step over carrying a shotgun. He'd put it on the table along with the whiskey, and he'd break the whole shotgun apart in pieces and then carefully wipe and oil it. This would take him about two hours, until it was finally together to his satisfaction. Then he'd say, "Good-bye," which was the second word he would say. Then he'd go back over the parapet.

On the verge of this great success, were you beginning at last to think of yourself as a writer?

But I didn't think of myself as a screenwriter . To me, that was a pleasurable way of earning a living. And a writer didn't mean just writing screen-plays. It meant doing other things. I had lots of plans and began writing short stories and so on.

Did you keep company with other Hollywood writers?

No, I never knew any writers. There was a writers' table [at MGM], which

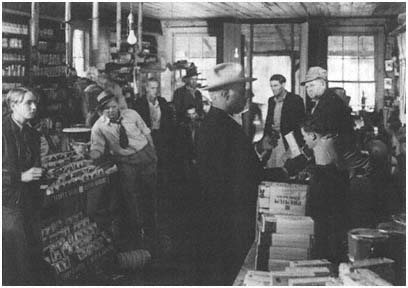

A key scene from Intruder in the Dust: Juano Hernandez (center) braves Southern

racism, while Claude Jarman, Jr. (far left), looks on. Ben Maddow adapted William

Faulkner's novel. (Photo: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

I was appalled by, because they discussed nothing but agents and contracts. At the head of the table sat [screenwriter] Leonard Spigelgass, who was a fairly bright man, but who put on this rather silly demeanor. I got nothing out of that scene at all.

Do you mean the great writers' table at MGM is but another Hollywood myth?

Well, don't forget that I grew up where intellectuals got together and fiercely argued some great point, and there was nothing of that there. (Laughs .)

Albert Maltz, whom I knew from college, once told me that there were three secrets for success in Hollywood. One was talent, the second was luck, and the third and probably most important was social contacts. Well, I didn't believe any of this. I had a certain amount of ego, but I didn't think that they would hire me because I was such a great writer. I knew that it was all luck!

Did you have any cachet in Hollywood because of your involvement in the documentary movement? Was there any familiarity with Native Land?

Nobody ever heard of it. I never heard it mentioned. I was another name then, my name [at the time] was really David Wolff, so I was not known [to be the same person as Ben Maddow] for a long, long time.

Then Hollywood people were not aware of your poetry either?

No.

That must have been an odd schizophrenia to maintain, especially as your poetry was so very special to you .

Yes, of course it was, but it was like a private thing—so what! No one in Hollywood had ever read poetry journals.

In any case, my wife and I never cultivated the producers and the important writers, which would have made a lot of difference and would also have changed our life-style. We've always lived very simply while the others lived on the west side with swimming pools and all that sort of thing. Our friends were all different kinds of people, mostly professionals of one kind—civil engineers, doctors, lawyers—and people in the lower professions as well. I never threw a party where I invited Hollywood people and where you could take somebody aside and discuss some project that you were interested in. None of that which is part of the texture of Hollywood. Everybody does it. Maybe I just didn't know how to do it.

You didn't feel at all left out?

No, I didn't feel in any way isolated. Don't forget, I had an intellectual life of my own.

After Intruder in the Dust, obviously your stature went up, and you became in demand. In quick succession you wrote two rather interesting genre films, Framed [1947] and The Man from Colorado [1948] .

Both of those films were produced by a guy I met at the [army] post [Jules Schermer]. That was practice. They were both melodramas, after all. I have been described as "Ben Maddow, screenwriter of mystery and adventure films," but that is just accident. I think Framed was a pretty good melodrama. I remember I felt thrilled that I had invented the opening, in which there was danger from the very first, because there is a truck which is out of control with no brakes. But I never thought these films were a vehicle for any kind of ideas. They paid well, far more than I had ever earned in my life. I couldn't believe it!

Critics have written that you have always managed to imbue your scripts with serious social ideas .

Well, it was certainly not intentional. Maybe the ideas were there in the original material. If you want to look at Intruder in the Dust as a depiction of a certain kind of class structure of the South in which the old gentry, the old landowning gentry, had moved around to where they were really on the Left and were [now] forming an alliance with the blacks, although that is not true, of course—okay. But that is in Faulkner's novel, too.

On the other hand, the social ideas that are in these films, you may not have pondered them intentionally, but they are part and parcel of your fiber .

Oh, of course.

For example, though the story line of The Asphalt Jungle [1950] remained the same on the screen, the point of view of the script became more progressive than that of the novel .

I don't think that was done intentionally. I think it all came out of the novel, though [author] W. R. Burnett did not realize it. Burnett intended The Asphalt Jungle as a novel about the extraordinary difficulties that the police

have in an urban world that has become a jungle. As a matter of fact, the narrator in his book is the police superintendent, is he not?

The film takes the opposite point of view. That crime is simply normal endeavor, another form of business; therefore the concentration on the characters of the criminals makes you like them all and sympathize with them. Certainly you don't sympathize with the police at any point. In any case, I think many authors do not know what it is they are saying, and Burnett made those criminal characters so fascinating that as you read the novel you really didn't feel as though the police were the heroes.

Why would Huston want to invert the original emphasis of the story line if he liked the novel of The Asphalt Jungle so much?

I don't think any conscious decision was ever made, not that I can remember.

It just developed?

Yes. I don't think Huston thinks in those abstract terms. Don't forget that a lot of the power [of the movie] was due to the fact that these were New York actors who all knew one another and were trying to outdo one another—and who were stimulants to one another. There was nobody who had a name of any consequence.[*] It was a film for broad booking. Most of Huston's talent came in the choice of casting, which most directors will tell you anyway, in moments of frankness. It could have been quite a banal film if badly cast. Imagine Van Johnson or somebody else in the leading part! But it was not an important film, so it was easier to cast.

How did you get involved with Huston?

He accepted me on the recommendation of Clarence Brown. Huston and I must have worked on the script together, oh, close to six months, and really very little work was done. No pages were turned in. We were mostly talking. He always did very little at the typewriter anyway.

The day would proceed. You'd arrive at his beach house at 9:30 or 10 A.M. and Huston would just be getting up to have breakfast. He'd come down in this beautiful robe and play with the Weimaraner dog with blue eyes that he had just got. And if the dog had thrown up, which he often did, Huston would have to haul the carpets out onto the beach.

Then later, we'd have lunch, work a couple of hours, and it'd come time to have a drink and so on. I used to come rolling home and I'd lift my fingers to indicate whether I'd had one cocktail or two, so my wife would know what state I was in. (Laughs .)

I had rented a beach house just about a mile north, and one day Arthur Hornblow, who was the producer, called me up and asked me to come and

* The cast of The Asphalt Jungle included Sterling Hayden (Dix Handley), Louis Calhern (Alonzo D. Emmerich), Jean Hagen (Doll Conovan), James Whitmore (Gus Ninissi), Sam Jaffe (Doc Erwin Riedenschnieder), John McIntire (Police Commissioner Hardy), Marc Lawrence (Cobby), and Marilyn Monroe (Angela Phinlay).

see him. He said, "Look, I can't pressure John. He just won't take it. But I have to tell you that this is going on too long. . . ." Though we were getting paid weekly, I was getting bored with this situation, too. And I really felt guilty about it.

I promised Hornblow that I would talk to John. John's reaction was very interesting. He said, "Ben, you're absolutely right! . . . But my father [actor Walter Huston] is coming over to dinner tonight with his girlfriend. Why don't you have dinner with us and we'll work after dinner?" I said, "No, I'll go home and then I'll come back after dinner. . . ."

So I did. I guess it was about eight o'clock when I got back, and they were still talking at the table. They were talking about John's feeling that he was able to direct because he hypnotized the actors. Remember, he had made a film [Let There Be Light, 1945] during the war in which hypnosis was used as an example of how powerful it was. And he offered to hypnotize his father's girlfriend, a much younger woman. She said, "No, you'll make me do something I don't want to do." He assured her that he couldn't do that, which is not true, by the way. Then he wanted to hypnotize his father, and his father refused.

Huston turned to me, and by this time a whole hour had passed, so I said, "Okay." He had me stand up and he took his wristwatch off and shone a light on it, dangling it [in front of my eyes], saying, "Your eyes are closing . . ." My eyes closed. "Your arms are rising from your sides . . ." They did. "I'm going to pinch you and you won't feel a thing . . ." He pinched me. "Do you feel it?" "No." This went on until he gave me a posthypnotic suggestion. He told me that when he woke me up, he would offer me a brandy. I would taste it and say, "This is the most divine thing I have ever tasted in my life."

So okay, I wake up, we go back to the table and sit down, and he says to me, "Would you like some brandy?" I say, "I wouldn't mind." He hands me the glass, pours the brandy, and all three of them watch me. He says to me, "Aren't you going to drink it?" I lift it up, taste it, put it down, and there's silence. He says, "How was it, Ben?" I say, "Fair." (Laughs .)

That was Huston's hypnosis—just nonsense. (Laughs .) We didn't work much that night, but things proceeded a little more smoothly after that. And we finally did get the script done.

After The Asphalt Jungle, you wrote two films which I haven't seen and which I know very little about —The Steps of Age [1951] and Shadow in the Sky [1952] —

Steps of Age was a documentary which I made on the question of old age for a company back East. I directed and wrote that film. Shadow in the Sky was a Hollywood picture, a very bad one, too. It's about a returned vet with a lot of psychological problems. Nancy [Davis] Reagan was in it.

Why would you follow two such prestigious projects as Intruder in the Dust

and The Asphalt Jungle, in Hollywood, with something like Shadow in the Sky?

I think I took it because it was offered to me. Perhaps it was offered to me because it was the story of a returned vet who has psychological problems—and because Intruder in the Dust and The Asphalt Jungle do have certain social implications. I was considered somebody whom one would pick if the story had these values.

I didn't have any idea of an arc of a career. People just asked if I was interested in the material or if I was getting broke. I did turn a lot of things down. I once turned something down at Columbia because I said I was working on a long poem. "I just don't have the time to do it," I said. Well, this went around town. . . . People thought it was the funniest thing they had ever heard. The guy must be out of his mind! (Laughs .)

Interlude: The Blacklist

Shortly after The Asphalt Jungle, you were blacklisted, am I right?

I was blacklisted about 1952. I had been hired by Stanley Kramer. That happened because we had a common agent. I was working on two films [for him] at the time. One was an early version of High Noon, and the other was The Wild One . I had done a very rough, tentative version of High Noon, from the novel [actually, a short story, "The Tin Star," by John W. Cunningham], and a complete version of The Wild One .

Then Kramer called me into his office. He said, "I'm sorry, I have to fire you. . . ." Well, so many people had already been fired that I didn't really need any further explanation. But I took my name off The Wild One because I saw a version of it that I disliked very much. It was partly mine and partly not. That's always a very difficult thing, to assign the degree of responsibility [for a script]. I like to think that when a writer goes to heaven, he's going to go to this huge file room, where they can look up his name and tell him precisely what his credits are. No crap!

You seem to be relatively good-natured about the blacklist .

(Pause .) There were very unfair things done, but you can't be bitter about it. My view of the blacklist is that the FBI had people in every left-wing organization, often in prominent positions, and that they had complete lists [of leftists] all along. Their Hollywood campaign was not a malevolent and personal one. The general idea was to deny the Left funds, since the Hollywood people made a great deal of money.

The screenwriter John Bright told me at one point that the Hollywood branch of the Communist Party poured more money into the party than any other branch, except for the D.C. section. I would have figured that it would be the New York branch, not the D.C. one .

(Laughs .) That might be so. Well, the salaries here are far greater than any intellectual would make even if he was an editor in a publishing house.

So, you don't feel the blacklist was an attempt by the right wing to end any progressive influence of the content of motion pictures?

I don't think so, because there's nothing to influence. That was just a put-up job. In what way could you say that Intruder in the Dust was a left-wing film? Only in the sense that it is about a black man, unjustly accused, who is nearly lynched. That was a pretext. The whole thing really came down to money.

Wasn't it also a power struggle—in the unions and over who would produce the films?

There might be some aspects of that, but I think the number of people who were on the Left in Hollywood was rather small, smaller than the percentage among New York intellectuals. And they were not governed by the same influences. In New York there was a whole ferment of political discussion, and other left-wing groups outside of Communist groups, the Partisan Review and so on. I think the left-wingers here, like myself, were transplanted, in alien territory. In a way, the left-wing activity was a sop to the conscience.

Did you meet the writer-producer Philip Yordan before the blacklist?

Never met him before. One of the great characters of the world.

Were you in dire financial straits at the time you became associated with him?

We had some money in the bank and we had just bought this house for $19,500 at 4 1/2 percent, so it was not all that great of a burden. But we did need money, and a friend of mine named Irving Lerner, who was an editor and a director, was hired by this guy [Philip Yordan] to do a film: Man Crazy [1953] and—there was another one—Murder by Contract [1958]. Irving was a very wonderful editor but a terrible director. He just didn't know where to put the camera. (Laughs .)

You knew Irving Lerner through the documentary movement?

Oh sure. He was in Frontier Films. Yordan wanted a writer, so Irving recommended me, and, of course I could be gotten very cheaply then. I must have done—I really can't tell you how many—somewhere between six and ten scripts for Yordan [during the fifties].

That's where everything becomes vague in the filmography, because some films that I never did have been credited to me. In fact, a friend of mine sent me a notice from a Spanish newspaper last year that said, "Ben Maddow, hombre misterioso." And it stated as bold fact that I had actually written all of the Huston films [during this period]! (Laughs .)

Was Philip Yordan doing much writing on these films?

Philip Yordan has never written more than a sentence in his life. He's incapable of writing.

You're kidding .

Of course not. Look, I was intimate with him for several years. He always used somebody else, from the beginnings of his career. I could tell you a lot about Philip Yordan.

Please do .

Oh, it's a fascinating story. All right. In Chicago, where he is from, Yordan was a lawyer and an entrepreneur who marketed liquid soap. When the war started, Yordan was posted to the airfield in Ontario [California], but he used to spend Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles he wandered around saying to himself, "Jesus, I gotta work out here, but what can I do? I don't have any craft . . . maybe I ought to become a writer!"

So he walked into the Ivar Street Library and asked, "How do I learn to become a screenwriter?" The librarian said, "Well, have you ever written a play?" "No." "Have you ever been to see one?" "No." "Well," she said, "you should take a great play and study it and follow its rules and that will help you a lot." So she gave him this play, and he went home to look at it and then he wrote a screenplay from it, copying it scene by scene, only changing the heroine from this girl who comes back to her New England town, into this B-girl that he knew from a Chicago bar whom he was tremendously in love with.

Anna Christie —that was the play—which is why it [Yordan's version] is called Anna Lucasta . He once showed me a picture of this B-girl—a rather pretty, heavy-set girl. She didn't like L.A. She loved Chicago. She wouldn't move out here. The only person he ever expressed any tenderness for.

Anyway, he had this play—

He wrote it?

He copied it, really, changing it to Chicago dialect. That was probably the most laborious thing he ever did in his life.

Now then, he had a friend [writer-producer Sidney Harmon] who had had a smash success with Men in White . This friend said, "I'll show this play to my agent." Nothing happened for months on end. Then Yordan got a call from the agent, saying there was a black group uptown who was willing to pay ten dollars a night for [a production of] it. The agent said, "Take it!" The group put it on, it was a smash hit, and he was set.

Only, he couldn't write! He always hired other people to do the writing. I was not the only person; there were other people. . . .

What about House of Strangers [1949] for Joseph Mankiewicz, what about Detective Story [1951] for William Wyler, what about Yordan's Oscar for Broken Lance [1954]?

Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe he could write a word or two, or a sentence or two.

House of Strangers, about a man and his son who had a banking empire, did win an Academy Award for story. But Yordan's secretary, whose name

I've completely forgotten—she was a lady who had one crippled leg who I sort of inherited from Yordan—told me that the story was actually written by the producer of that film [Mankiewicz]. He sent it as a long memo to Phil. She typed it. The story for Broken Lance —Yordan got the Oscar for the story, incidentally [and not the script]—also came from the story for House of Strangers .

When you first met Yordan, what was his rationalization of what he was going to do, putting his name on the screenplay instead of yours?

Oh, it was "I want you to write and, of course, you can't use your own name because you're in trouble, but I'll pay you 50 percent . . . after all, on your best day, you could never make one tenth of what I make." It was true! But I was never sure of what percentage it actually was.

So although he would be credited as writer, he would actually be behind the scenes, functioning like a producer?

Well, you know Ben Hecht used to do the same thing. Hecht had a stable [of writers] down at the beach who would write for him. He would write the original two pages or so in Hechtian style, and since he had an enormous reputation, he would get a lot of money for it. Then they would sit down and do the screenplay in Hechtian style. Maybe Hecht would add a few flourishes, but he made a lot of money that way. That was all very well known here.

Were there other people in the Yordan stable besides yourself?

Oh, yes. But I think that during this period, I must have done all of the things Yordan did. He was always buying books; he had a dozen [properties] going at any one time. He would stack the books up in rows and he would sell [them to the studio on the basis of] the photo [the cover photo]. He would show the book covers to the producers. "This is what I own," he would say.

Did he have any politics?

None whatever. Only: Yordan. But he did keep saying to me, "I feel ashamed because you are really a fine cabinetmaker . . ." He had some guilt.

He had pitiful eyesight and a horrible home life and was married and divorced a number of times. God!

Did he have good ideas as a producer?

Occasionally. And if you gave him a good idea, he'd steal it from himself later on. There's an idea in Men in War [1957] in which the platoon commander is killed, they strap him into this jeep, and they drive him around as though he is alive just to keep up the morale. Well, Yordan used exactly the same idea in some film about Spain, El Cid [1961], where the guy is strapped into the saddle.

That brings me around to a really great story about Yordan. Somewhere along the line he said to me, "I'm sure we could sell a Western—there's always a market for one. Have you got an idea for a Western?" This was a Thursday and I said, "Well, no, but I'll think about it." He said, "Well, let's talk about it on Monday." So I came back with an idea for him on

Monday and he said, "Fine." He didn't really want to listen to it too much; he just said, "Do it. And get the screenplay done as fast as possible. I'd like to have it done in three weeks."

I actually wrote the screenplay in about three and a half weeks, and when I brought it back, he sort of cursorily looked at it to see how many pages it was. It was 134 pages, so that was okay. He changed the names of the characters because he carried with him a little book that said things like "James means 'noble,' " right?

He said, "Now, we have to go to work." I said, "What work?"—expecting him to talk about revisions. He said, "Now come with me." He sat in the study and he made the following phone calls. He called Simon and Schuster and said that he had just sold a screenplay of a Western to Warner Brothers and were they interested in the book from which it was taken? Well yes, they would be interested. Then, he called the script department at Warner Brothers and told them he had sold a book to Simon and Schuster and would they be interested in the screenplay? He'd send it right over, which he did.

He sat there and worried for about three quarters of an hour. Then he said, "This is really very shaky, I've got to make this certain . . ." He called up a minor executive at Warner Brothers and said, "I know you owe $14,000 in Vegas. I will pay that sum for you and get you out of this trouble. All I want you to do is the following. I have sent a script over to Jack Warner. It has a blue cover and is called Man of the West . Get to it before he does, in the morning, pick it up, and return it at four o'clock and say, 'I picked this script up by mistake, instead of mine, and I started reading the first page and I couldn't put it down.' That's all I want you to do."

Well, he had to pay the $14,000, but so what? Because the screenplay was sold. Now he called Simon and Schuster and told them he was going to send them the book manuscript right away because the film was going to be made. So I had to sit down and write the novel, which I did.

That was Man of the West?

The novel.

The novel that is supposed to have been written by Philip Yordan?

Exactly. It was published in Collier's in three sections. We split everything fifty-fifty, although I don't know that for sure because I never saw any contracts. Also, I happened to be in England several years later, and there was a Penguin edition of Man of the West with a picture of Philip Yordan [on the dust jacket], and he had never told me he had sold it to them. We happened to have the same accountant, who was very upset by this fact, so we settled for some small sum. . . .

Did you ever meet the directors of these various films? Nicholas Ray?

Never saw him.

Never once?

No. Well, I might have met him once.

Anthony Mann?

Not to my memory.

I have interviewed Philip Yordan. I also spoke with Bernie Gordon and Milton Sperling, who at one time or another collaborated with Yordan. Gordon and Arnaud D'Usseau, both blacklistees, ghosted for Yordan in the 1960s. And Sperling acted as a producer for him at various times, whether or not Yordan was actually writing the script —

Did I ever tell you my Milton Sperling story? My agent called me and said, Do you want to work for Milton Sperling? I knew who he was. I went up to his house. This was his idea. He wanted me to look at the last five winners of Best Picture of the Year, take the best scenes out of each of them, and recombine them into another film. (Laughs .)

I turned it down. Who knows? It might have been great!

Yordan has me stumped on one thing. He was frank about some things, evasive about others, but on one matter he wouldn't budge—that was Johnny Guitar. He insists he wrote Johnny Guitar.

Well, I looked at some of the film over at my daughter's house [recently], and frankly I can't remember [working on] it. As far as the underground list is concerned, that's very doubtful. I don't care, you know, one way or another.

When you looked at it, it didn't ring any bells?

No. but if I looked at any of the others, I probably wouldn't recall them either. I don't think, for any of these movies, that I ever saw anything beyond a rough cut. And if you work on something for six to eight weeks—and this was thirty-five years ago—you forget.

You sent me in the mail a list of films that you had written, including those which you scripted under the table in the fifties, and Johnny Guitar is on that list. What has made you claim it as a credit, up till now?

All I can say is I can't tell you if I wrote it or not. This filmography [I mentioned earlier] in which I'm credited with things I never did comes from France. A number of films are listed that I was supposed to have done for Philip Yordan. Perhaps I thought their information was accurate. It probably corresponded with some of the things I remembered, and since I think Johnny Guitar was on the list, that may have been how it was lodged in my memory. The French are very big on B films. Their idea of an American literary hero was Edgar Allan Poe.

Were you constrained at all in the writing of these films by the fact they were so impersonal to you?

Yes, but I didn't think they were that different from what other people were doing. I didn't feel as though I was being punished in some way. Punishment was that I couldn't use my name. Some of the films were probably pretty bad, because I didn't give a damn [about the subject matter], but I tried at least to be ingenious.

These scripts were, in relationship to myself, pretty much with the proviso of a lemma of mathematics. A lemma is a consequence of or a footnote to a theorem. (Laughs .)

Did you feel particularly proprietary about any of them?

Maybe God's Little Acre [1958], which I don't think was [based on] the greatest book about the South ever written because, after all, I do admire Faulkner, who was a far more profound writer [than Erskine Caldwell]. But there was some truth to Caldwell.

How did you end up feeling about Yordan?

Oh, we never quarreled or anything like that.

But you had a love/hate relationship with him?

No, but I was simply astonished about what went on in his house. You'd be working during the day, you'd stop there for lunch, you'd be sitting at the table, and his wife would bring some food in and say, "I poisoned it. I hope you die." To show his contempt, he would get up and take a leak with the door wide open. (Laughs .)

I never had a fight with him or anything, no. You couldn't fight the guy. In many ways he was very sweet. He was only doing what to him was a business. But something happened, I can't remember precisely what, and then he went to Spain.

You were grateful for the work?

It saved my life. But I also had a terrible psychological complex [about it]. In fact, I was close to a breakdown. At that point, I went into analysis. I didn't know it at the time, I didn't make the connection, which became very obvious, but it was an abdication of oneself. Because here were your ideas, which are very close to you, closer to you than you think as a writer—you don't think that they're a part of yourself, but they are. Here was part of your personality, not attached to your name—up there on the screen.

Were you writing poetry as any kind of release?

Yeah. I don't know how much. There were long periods when I didn't write.

So, you were undergoing analysis, you were writing all these things under a pseudonym, you were undergoing writer's block under your own identity. Did this result in some kind of personal catharsis?

I think analysis helped me a great deal. I had been having nightmares, night after night. I'd awake in terror. Of course, you invent these terrors yourself, but that makes it even more frightening. I don't know whether this all might not have happened independently of Yordan [and the blacklist]. It seemed to be attached to the whole question of damage to your self-image.

Incidentally, I did a couple of films under Frontier Films which also had other names put on them. Like Erskine Caldwell was given credit for one of my narrations [People of the Cumberland, 1937]. Because they felt his name meant a lot, which it probably did. I just wonder whether this assault on the ego didn't also tie into that.

Did the culmination of your analysis and coming out of the blacklist, did they dovetail?

More or less.

What happened?

Well, the whole thing was falling apart, the blacklist, and as I understand it by implication from my agent, though I have no proof of it, the William Morris Agency was very anxious for me to make more money for them. So the agency paid [Donald] Jackson [a Republican congressman from California], who was then a representative on one of the committees, to erase my name from the lists.

Paid him off?

Paid him off, yeah. He died maybe three or four years after this happened, and there is no way of proving it at all. After that, bit by bit, I went back [to work], though I don't think that the films that I did [after that] were particularly interesting, actually. I didn't start at the same point; I had to start lower down. By this time I had been forgotten [in the industry], really.

You never got any explanation of why you were able to go back to work. Someone just said, "Okay, you can go back to work . . .?"

I believe I got some call from one of their attorneys [to start the process], but it took a long time [to go through], about a year and a half. I don't know whether that supposed payment did the trick, or whether there was actually a lapse in the whole system of the blacklist. Such arrangements were being made all over the place. Other people went back.

You never talked to Jackson .

I went to see Representative Jackson in Santa Monica. I signed some sort of statement. I can't remember what was in it. I never took a copy of it.

Walter Bernstein tells me that when he was in Hollywood in the late fifties, you told him you were working with Kazan at that point, after having cooperated with the committee .[*]

I did work with Kazan on a film which I refused credit on because the final script had no resemblance to what I had been doing. Wild River [1960] it was called.

Walter said he had breakfast with you and you told him you had named some names for the committee .

I don't recall any such conversation.

Did you not name any names?

* Stage and screen director Elia Kazan gave testimony before the executive session of the HUAC in April 1952, naming several former Group Theatre colleagues and others as having been fellow Communist Party members. He drew up a list of his motion pictures that "explained" their content as the exact "opposite" of Communist ideals. Shortly thereafter, Kazan took a full-page ad in the New York Times defending his "abiding hatred" of Communism and exhorting others to come forward with names. Kazan, the director of On the Waterfront and A Streetcar Named Desire, is generally considered one of the most prominent people to have given validity to the HUAC investigations and resulting blacklist. See Victor Navasky's Naming Names (New York: Viking Press, 1980), pp. 199–222.

Well, it might have been in the statement, but I don't recall.

He said you told him not to worry, they were all dead people except for Leo Hurwitz .

(Laughs .) Really! Well, his memory must be a lot better than mine.

You don't consider yourself a cooperative witness?

Well, I did cooperate. Obviously. I signed a statement.

But you insist you don't remember what the statement said. What was that meeting like? Was Jackson trying to extract some information from you?

Oh no. He was already rather ill, and he wanted to get it over with. It was formally an Executive Session, or something like that.

Didn't working with Kazan give you a kind of twinge?

Oh no. I thought it was a fascinating experience. Actually, most of the time I worked with Kazan, I was doing research in the South and he wasn't even around. But I did have several conferences with him and finally did a script on the TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] question, which I was very interested in, having gone through that same period myself. Maybe my script was no good. I don't remember. Kazan told me he wanted somebody who had more experience organizing the material. There was a prolific amount of fascinating material.

I think he was right, incidentally. One of the things I've struggled with all of my life is organization. I didn't want any credit on the final script because it was so obviously the work of another man and superior writer, Paul Osborn.[*] A very good technician.

But you knew Kazan had cooperated fully with HUAC .

Oh, sure. Although I never read his testimony, so I wouldn't know. . . .

How did Kazan come to you?

We had the same agent.

He didn't know you?

I had some sort of reputation. I had never met Kazan before.

But you had spent so many years on the blacklist. And you had not been working publicly, using your own name in films, for quite some time. Wasn't it terribly convenient that Kazan would come to you at this point?

Well, I think probably he would have not hired me if I had not signed it [the HUAC statement]. Obviously! But it didn't make any difference to me that it was Kazan. I always regarded Kazan as a very, very talented man. A complex man, of course.

I never had the measured feeling that a lot of these people had, people like Alvah Bessie and Albert Maltz.[**] I regarded myself as caught between two

* Playwright-screenwriter Paul Osborn had an estimable list of film credits, dating from 1938 and including The Yearling (1947), Portrait of Jennie (1949), East of Eden (1955), South Pacific (1958), and Wild River (1960).

** Ex-journalist Alvah Bessie, one of the Hollywood Ten, fought with the International Brigade in Spain, wrote several screenplays for Warner Brothers (including the Oscar-nominatedstory for Objective Burma! ), and never resumed his Hollywood career after the blacklist. Instead, Bessie wrote novels and one of the best memoirs of the blacklist era, Inquisition in Eden (New York: Macmillan, 1965).

sets of ideologues. I don't regard myself as having done something wrong [by cooperating]. Conscience had nothing to do with it. (Laughs .)

It was like saying, here's a flag and here's a flag, now which flag are you going to salute? And if you don't believe in flags . . . there you are! (Laughs .)

But when you signed a statement for Jackson, weren't you, in effect, saluting one of those flags?

Well, that's true. But it was a question of whether I would support my family or not. And since I didn't owe allegiance to either of these ideologies, it didn't matter to me. I thought they were equally foolish.

Did you not feel an affinity with the other Hollywood leftists?

I suppose I did. But I never became friendly with them.

Did you not consider yourself a leftist?

Yeah, sure. But never in a conventional sense. Because there's much of Marx that I always felt was just silly. The anthropological parts of Engels are just ridiculous, and people took them very, very seriously. Any theory, when matched up with life, doesn't begin to deal with complexity. And I'm interested in complexity.